2: Power and Process under the Republican “Constitution”

Republican Rome had no written constitution. It did, however, have an array of remarkably tenacious continuing institutions (in the broadest sense of the term), some of which were or at least seemed virtually primeval. And at all times it had men who were willing to make confident assertions – as senators, magistrates, priests, or specialists in jurisprudence, or in more than one of these roles at once – about what was legally possible under an often fuzzy and ever evolving political and administrative system. A few went a bit further than ad hoc pronouncements. Certainly by c. 200 b.c., the Roman élite was taking an academic interest in the city-state’s legal history.1 In the developed Republic, at any rate, some important colleges of priests maintained books of precedents; the senate’s past decrees could be consulted in written form. Cicero’s On Laws, to single out just one of his contributions to political philosophy, actually contains a short (idealizing) constitution, a theoretical piece that treats Rome’s magistracies and some aspects of the state religion. One must add that a well-connected outsider, the Greek Polybius, writing in the mid-second century b.c., left us an invaluable, though frustratingly selective and overschematic, sketch of the Roman state as he saw it.

But, again, the Romans of the Republic never made a comprehensive attempt to formalize their public law. It may be worth considering, if only for a moment, why not. One basic reason is that the people most likely to draft such a document – the leading members of Rome’s senatorial establishment – were in all periods fully conscious that writing things down served only to cut into their own class prerogatives and influence. Another factor is that, by the time a Latin legal literature was first developing (say, c. 200 b.c.), the political system was even in its essentials too vast to take in as a whole. For some centuries, each successive year at Rome had seen the complicated interplay of individual (mostly annual) magistrates and quasi-magistrates with each other and with a number of strong but hardly monolithic corporate entities – most vitally, the senate (the body that advised the magistrates), the people (i.e., Latin populus, patricians and plebeians together) and plebs (the body of nonpatricians) in their several organized and even unorganized forms,2 and various boards of priests. In the later Republic, the knights (or equites) – the wealthy non-office-holding arm of the Roman ruling class – added themselves to this heady mix. Indeed in all periods, the shifting dynamics of Rome’s profoundly hierarchical society (about which we shall say something later) influenced institutional processes.3 So involved and ingrown became political Rome that the rationale for some aspects of its system, such as the procedure for electing certain high-ranking magistrates, escaped even the curious.4

Of course, concurrent with Rome’s annual pattern of political give and take was its seemingly inexorable growth in power. New military and administrative challenges periodically threatened to stretch the old, inherited city-state institutions to their breaking points. That, in turn, forced the innately conservative Roman governing class to accept innovation and sometimes even permanent reform in the political system. The fact that Rome’s administrative machinery constantly needed to adapt to new circumstances militated against any visionary’s drafting a constitution that would last for long. But the dilemmas that arose out of the state’s steady expansion in influence gave the experts much material for comment. The more authoritative of such statements resulted in implementation – for instance, the senate almost automatically accepted the findings of major colleges of priests on public law questions that fell within their competence – and so cumulatively went some way toward shaping the res publica in its pragmatic aspects.

A Lecture on Legitimate Power

We have a particularly succinct formulation of constitutional basics, one that introduces us to additional attributes of the Republican system, from the twilight years of the Republic. It is a passage from Cicero’s 13th Philippic,5 delivered in the senate in March of 43 b.c. Here the orator addresses the disaffected and dangerous commander Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, who was then in charge of two armed western provinces (and before the end of the year was to establish the triumvirate with Antony and Octavian). Legitimate power, Cicero admonishes Lepidus, is what is allowed by positive laws (leges), ancestral custom (mos maiorum), and accepted precedent (instituta). Those who want to get and wield power are further circumscribed by a general societal expectation for self-restraint. “What an individual can do is not necessarily permitted to him; nor, if nothing stands in the way, is it for this reason also permitted.”

Cicero then shifts to the personal. Lepidus’ circumstance as a nobilis – the élite status that derives from having one of Rome’s eponymous chief magistrates as an ancestor in the male line – introduces additional considerations, Cicero implies. So does his year-old position as the most important priest in the state religion, head of the board of pontifices. If the commander spontaneously should abandon the notion that he is entitled to do as much as he is able to do, says Cicero, and interpose his considerable personal authority (auctoritas) in the day’s fluid political situation without use of force, “you are truly Marcus Lepidus, Pontifex Maximus, the great grandson of Marcus Lepidus, Pontifex Maximus [in the years 180–153/152 b.c.].” Such self-restraint, we are told, is in the grand tradition of the Aemilii Lepidi. (We happen to know that Lepidus took considerable pride in his great-grandfather.)6 But in the last resort, to check undue ambition, Rome had strong formal institutions in place. Though Lepidus had considerable personal authority, Cicero stresses that at that moment the senate was never “more dignified, more determined, more courageous.” The upshot for Lepidus and his command? “You will obey the senate and the people if they see fit to transfer you to some other task.”

One wonders what the elder Marcus Aemilius Lepidus would have thought of Cicero’s mini-lecture on power and authority. A patrician “noble” who was regarded as the handsomest man of his day, Lepidus had the good fortune to find himself honored by the senate with an equestrian statue on the Capitol before he even started his political career in earnest.7 Though his keen sense of entitlement led the people to hand him an initial defeat for the consulship (i.e., the paired annual magistracy that headed the state) of 188 b.c., he reached the office the next year and then again in 175 b.c. – the first man since the towering figure of Scipio Africanus (consul II, 194) to hold it twice.

But it was the accumulation of further distinctions that gave Lepidus, in the words of the greatest modern historian of Rome’s political families, “truly princely status.”8 The year 179 b.c. alone saw Lepidus as pontifex maximus, as one of the two censors (the censorship was a magistracy that involved some especially important sacral and civic duties), and, using his censorial powers for self-appointment, as ranking senator (princeps senatus). Lepidus was able to hold those last two posts – in other words, the superintendancy of the state religion and a presumptive right to speak first in the senate – until his death in late 153 or 152 b.c. From time to time he combined these imposing positions of authority with other roles, including his second consulship.

Notwithstanding what Cicero implies in the Philippics passage, this Lepidus showed little hesitation in exercising his considerable powers to the fullest when he saw fit. For instance, in 178 b.c. as pontifex maximus he indemnified his daughter Aemilia, the chief priestess in the service of Vesta, for letting the sacred fire of her goddess go out – a deeply serious religious infraction – after personally scourging one of her Vestal assistants for the same offense. Now, in practically every generation of the classical Republic we find individuals with overlapping competences who freely drew on their personal influence to supplement their legitimate authority in the political and religious spheres. For the later Republic, of course a long series of names come readily to mind: Sulla, Pompey, Caesar, Antony, Octavian, and (as we have seen) the younger Lepidus. But it is not going too far to say that the elder Lepidus’ lasting institution-based authority, which involved so many vital aspects of Roman public life and stretched over a span of almost three decades, most closely prefigures what Augustus ultimately achieved.

To illuminate further some of the modalities of power in the political organism called the res publica, there may be a particular advantage in an introductory survey such as this to focus on the magistracy, the aspect of the Republican government about which we are arguably the best informed. And in examining the magistracy, it might make sense to look first and most closely at Rome’s officials outside the city. It is not just that here individuals’ powers (both legitimate and aggrandized) can be seen in their fullest expression. There is the added fact that, throughout the entire Republican Period, the problems inherent in having officials serve outside Rome in progressively more challenging military contexts served as a particularly potent catalyst for institutional change across the system.

Cicero took that as self-evident: “I will not mention here that our ancestors have always yielded to precedent in peace, but expediency in war, and have always arranged the conduct of new policies in accordance with new circumstances.”9 This is a passage from his speech supporting the Manilian law of 66 b.c. and arguing in favor of granting a special eastern command to Pompey.10 One could go further. Not only the exigencies of war but even problems such as the simple realities of transit to and from various territorial commands and the difficulty of ensuring smooth transitions between successive generals forced the Romans again and again to reshape their conception of imperium, originally the unlimited and (basically) undefined power enjoyed by the Roman kings. Magistrates, priests, the senate, and the people and plebs in assembly all play their part in this centuries-long story, making the evolution of imperium an excellent case study in the processes of constitutional innovation and institutionalization at Rome.

From a general survey of developments that shaped magisterial power especially (but not exclusively) in the field, we may then turn to an illuminating study of ambition and power in the city of Rome in the mid second century b.c. More particularly, we examine the improbable careers of two relatives who turned conspicuous public failure in the military sphere into domestic political success, albeit in varying degrees. The interrelated tales of the cousins Lucius and Gaius Hostilius Mancinus (who served as consul in 145 and 137 b.c. respectively) invite close analysis, for they open a welcome window on the Republican political and legal process in its three dimensions. Here once again we find Rome’s formal institutions – magistrates, senate, priests, and popular assemblies – intersecting in complex process. But in the story of the two Mancini we also get to see how class hierarchy and family connections, personal prestige, charisma, showmanship, historical memory, emotionality, and chance might work in Republican Rome as very real historical forces.

The Unofficial Exercise of Official Power

To gain a notion of the effective power a magistrate could possess in the developed Republic, look no further than the Roman noble L. Licinius Crassus. Cicero in one of his dialogues has this famous orator tell how he received very little formal rhetorical instruction as a youth. However, Crassus claims he did pick up a bit after serving as quaestor in the East; on his journey back from the Roman province of Asia c. 110 b.c. he stopped at Athens, where, as he says, “I would have tarried longer, had I not been angry with the Athenians, because they would not repeat the [Eleusinian] mysteries, for which I had come two days too late.”

The quaestorship was an entry-level office; it had limited powers, and in this period was usually held around age thirty. Indeed, Crassus technically will have been superseded as an Asian quaestor when he swaggered into Athens and demanded a repeat performance of the mysteries – and with it (surely) his own initiation at Eleusis.11

Now in the Republic, magistrates who took up provincial appointments still had a full right to function as magistrates in Rome before departure. They also retained their full powers until they came back to Rome. We know this latter fact from a variety of literary sources and now from an important inscription, first published in 1974, that will figure below (“New Boundaries on Legitimate Power, 171–59 b.c.”). Yet it still seems amazing that a low-level superseded magistrate could show this level of entitlement on his return journey to Rome and (to trust Cicero) exhibit no special self-consciousness in later recounting the episode to his peers. In this case, the Athenian officials stood up to the young Crassus. But there must have been countless instances in which Roman magistrates – or even nonmagistrates acting in an official capacity12 – managed to cow the locals.

We have seen Cicero offering a lecture on how magistrates should restrain themselves from exercising their formidable powers to the fullest extent. Indeed, the political system of the Republic was predicated on this basic understanding. Most magistrates chose to obey this principle, to a remarkable degree, right down to the late 50s b.c. – in the city, that is. Outside Rome was a different matter. For there commanders did not face nearly as many restrictions on their official powers, and subordinates might often find themselves in semi-independent positions, without effective oversight. Before considering this dual state of affairs, however, we need to arrive at an understanding of what the Romans themselves meant by magistrates functioning “at home” and “abroad.”

The Theology of Imperium

For the Romans, the story of legitimate power started on April 21, 753 b.c., give or take a year. Ancient tradition is unanimous that the auspication (literally, bird watching) undertaken by Romulus on the day of the city’s foundation – and confirmed by Jupiter through his sending of twelve vultures – in essence activated what are known as the “public auspices” (auspicia publica). Possessing the auspices of the Roman people entailed the competence to request, observe, and announce Jupiter’s signs regarding an important act and then to complete what was intended. Since auspication preceded every major action taken on the state’s behalf, it formed the basis of regal and then, in the Republic, magisterial power. Hence patricians – an élite class that closed their ranks to new members c. 500 b.c., soon after the expulsion of the Tarquins – long sought to monopolize that right as exclusively their own.13

The augurs – the priests who interpreted the rules surrounding the auspices – gave a spatial distinction to the spheres where public auspices were exercised. In the historical period (and perhaps well before it), the sacral boundary formed by the circuit of the old city wall (pomerium) delimited the urban public auspices; that area was known as domi (“at home”). Outside the city (militiae, “in the field”), another set obtained, the “military” auspices.

The term imperium is the standard shorthand way our ancient sources denote the king’s power. The term is generally thought to derive from parare (“to prepare, arrange, put in order”), in which case it would have originally been a military term.14 The greatest modern historian of Rome, Theodor Mommsen, (correctly) thought of imperium and the public auspices as largely overlapping concepts: “They express the same idea considered under different points of view.”15 He considered imperium to be an absolute power that entitled the king to do whatever he thought fit in the public interest. It was not simply a bundle of specific competences. Because imperium was vested originally in the person of the king alone, it was indivisible, and its power would have been no less on one side of the city boundary than on the other. Yet kings need some consent to rule effectively. Our sources report their consultation with an advisory body (consilium) of aristocrats, Rome’s “senate.” And presumably in some cases, especially those involving the making of peace and war, Rome’s kings also sought the (well-organized) approval of the people in assembly (populus), as the ancient tradition unanimously holds.

After the expulsion of King Tarquin the Proud from Rome (customarily dated to 509 b.c.), two magistrates – later to be known as consuls – were chosen from among the patricians. Each of the consuls received full public auspices and undefined imperium. But they differed from the kings in that their office involved collegiality (in case of conflict, the negative voice prevailed) and annual succession. And now both the senate and (especially) the people grew in importance. Tradition held that, in the first year of the Republic, the consul P. Valerius Publicola introduced further restrictions. A Roman citizen now generally had the possibility of appeal (provocatio) to the people against a consul who exercised his power in the area enclosed by the pomerium plus one mile beyond. (Commanders in the field did not have their imperium thus restricted until the “Porcian Laws” sometime in the second century b.c.)

Valerius also allegedly stipulated that, in the civil sphere, only one consul at a time should have the capacity for independent action, symbolized by twelve attendants bearing the emblematic ax and bundle of rods known as the fasces; the imperium and auspices of the other consul were to be dormant, except for obstruction.16 In special circumstances, the power of both consuls might fall dormant, with the initiative falling to a dictator appointed to hold imperium for a period of six months, notionally the length of a campaigning season. Through these means the Romans cleverly made the most of the executive branch of their government while mitigating the potential for conflict within it. Yet soon (after 494 b.c.) the powers of the plebeian tribunes would encroach further on the consuls’ exercise of imperium. Indeed the tribunes had the power of veto against all regular magistrates, but only in Rome itself.

By the mid-fifth century, it became apparent that two consuls, with the possibility of a dictator in time of crisis, were not enough to look after Rome’s ever increasing administrative and military needs. On the other hand, though they were often fighting wars against hostile neighbors on multiple fronts, the Romans at this point were reluctant to give imperium and, with it, full public auspices to too many men. One compromise attempt at a solution to the leadership crunch was the institution of the so-called military tribunes with consular power (potestas), first seen in place of the pair of actual consuls for 444 b.c. Now, every Republican magistrate had potestas, that is, the legitimate and legitimizing power that was inherent in and peculiar to one’s magistracy. Here the Romans devised a college of up to six magistrates who had the consular “power” to lead an army yet who did not have imperium and whose auspices were deficient in some way. (For instance, we know they could not celebrate the much prized ceremony known as the triumph.) The idea perhaps was to keep members of the plebeian class – who were eligible for the office – away from the highest public auspices. Yet the consular tribunate was an awkward institution, as it irregularly alternated with consular pairs on the basis of an ad hoc decision taken each year. What is more, each of a year’s consular tribunes had veto power over other individual members of his college.

Social conflict between plebeians and patricians, as well as a prolonged military struggle with the Gauls (who had sacked Rome in 390 b.c.), forced the Romans to abolish the consular tribunate in 367 b.c. Under what is known as the Licinio-Sextian legislation, they finally let plebeians into the consulship (or rather into one of the two consular slots) and introduced a new patrician magistrate, the praetor (either now or later known as the “urban praetor”), to serve as a colleague of the consuls. To create the praetorship, the Romans put a bold new construction on regal power. The praetor was to hold the king’s auspices as well as an imperium defined as of the same nature as the consuls’ imperium but minus (“lesser”) in relation to theirs. As a magistrate with this type of imperium and auspices, the praetor could do all that the consuls could do, save hold elections of consuls and (somewhat illogically) other praetors and celebrate the Latin Festival at the beginning of each year. All other activities of the consul were open to the praetor, unless a consul stopped him. But a praetor could not interfere with the consuls.

Though it had some precedents, the invention of two grades of imperium – one lesser than that of the two chief regular magistrates – marked a real innovation. For the first time, the Romans were able to reconcile in a proper magistracy the concept of permanent subordination with what was essentially regal imperium. This in turn more or less permanently solved the problem of excessive conflict in command. A second praetor, called inter peregrinos (“over foreigners”), was added c. 247 b.c., in the context of the First Punic War. It may well be that the first such praetor was the original governor of Sicily, which was created as Rome’s first permanent territorial province in 241 b.c. Sicily and Sardinia each received their own praetors c. 228 b.c., followed by Iberia (divided into Nearer and Further Spain) in 197 b.c. But after that, despite the accumulation of new administrative commitments, the Romans long resisted raising the number of praetors beyond six, apparently to keep competition for the consulship (for which the praetorship had become a prerequisite c. 196 b.c.) at acceptable levels.

Within a short period after the Licinio-Sextian legislation, other administrative developments come to our notice. In 327 b.c., it was decided that imperium could be extended beyond the year of the magistracy by popular ratification. This process came to be known as “prorogation” (prorogatio). A prorogued consul is known as a pro consule (“in place of a consul”), a prorogued praetor as a pro praetore. Such extended magistrates were expected to operate exclusively in the field; indeed, they lost their imperium if they stepped within the city boundary without special dispensation.

By 295 b.c., we see that a consular commander could delegate imperium – at the minus grade – in the field to a nonmagistrate for activities outside Rome. Livy provides the background for the first attested case.17 A consul was departing from his military command in the most literal sense, in that he was ritually sacrificing (“devoting”) himself to the enemy in battle. Before charging to his death, he handed over his insignia of office to an ex consul who was by his side, who then fought (significantly) pro praetore. The emergency years of the Second Punic War (218–201 b.c.) show the Romans coming up with other ways to give out imperium to private citizens, including popular legislation and even (for a special grant of consular imperium in 210 b.c.) pseudo-election in the centuriate assembly. After 197 b.c., the dispatch of praetors endowed with consular imperium to hold command in the Spains became a regular feature of the Republic; later, other distant provinces as they were created also received “enhanced” praetorian commanders (Macedonia and perhaps Africa from 146 b.c., Asia starting in 126 b.c., Cilicia c. 100 b.c.). And by the last third of the second century, we find that a consular commander could delegate imperium to a subordinate even while himself remaining in his assigned theater. Foundations such as these gave Rome the flexibility to build up its Republican empire.

It so happens that we have from the late Republic an exposition of the theological underpinnings of imperium that is based on an excellent source, distilling some centuries of innovation and rationalization. Aulus Gellius, writing in the second century a.d. but drawing on expert commentary by the augur M’. Valerius Messalla (who was consul in 53 b.c.), discusses how the public auspices were divided into grades.18 Consuls and praetors possessed auspices of the highest level (auspicia maxima), which were “stronger than those of others [magistrates].” One can extrapolate some important principles from this statement alone. It seems that auspices of the highest grade are a necessary prerequisite of imperium, though the two are not equivalent. Dictators, consuls, and praetors, all of whom had “highest auspices” both inside and outside the city boundary, held imperium. The situation of censors, who also had highest auspices (according to Messalla), was different. The censorship was a high-ranking magistracy created originally for patricians in 443 b.c. to enable them to take over some important consular sacral duties, no doubt so that the newly created consular tribunes (some of whom might be plebeian) could not touch them. Censors had highest auspices only in the civil sphere and did not have imperium.

Eventually, alongside the consuls, praetors, and censors, there emerges a sprawling third class of individuals who must have had a type of highest auspices. Some of these we have discussed earlier: prorogued consuls and praetors, nonmagistrates appointed in the city (i.e., by a special law) to important military commands, and men granted imperium in the field through delegation by someone of consular rank. To these one can add a few stray categories, such as certain commissioners elected with special powers to assign lands or found colonies. Yet all these individuals lack the highest civil auspices. Such men, for instance, cannot convene assemblies of the people, inside or outside the pomerium, or function as representatives of the state in any other significant activity in the city.

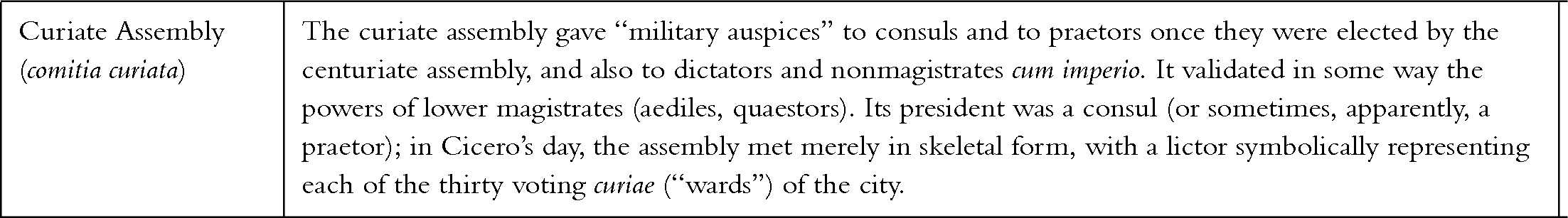

Our sources suggest a further technical point. An ancient organization known as the curiate assembly passed a law that seems to have validated the military auspices of new consuls and praetors. That this was the effect of the law has been disputed. But one good proof of this interpretation is that the people followed the election of censors in the centuriate assembly with the passage of a law, not in the curiate assembly, but in the centuriate assembly as well, exceptionally of all senior magistrates. Cicero is probably only guessing when he states this double vote for censors was taken “so that the people might have the power of rescinding its distinction, should it have second thoughts.”19 The procedure of a centuriate law presumably was meant to restrict the censors’ powers and to ensure that they did not consider themselves colleagues of the consuls, nor think they had military auspices. As Messalla tells us, the augurs in fact deemed the censors’ highest auspices to be of a different (i.e., lesser) grade (potestas) than that of the consuls. These magistrates could obstruct the actions only of their proper colleagues. But uncertainties as to the specific force of the curiate law must remain.

Following the passage of a curiate law on his behalf, the magistrate would activate the military aspect of his imperium through taking special auspices of departure to lead an army. Then, crossing the sacral boundary of the city, the commander and his lictors changed into military garb. The main evidence on these routines (as in so many other spheres of Roman political and social life) comes to us though negative examples. By the late Republic, we hear of tribunes vetoing the commander’s curiate law, formally cursing the commander at his departure, and the like.

If a magistrate then had to cross back over the pomerium, his military imperium lapsed and had to be renewed. If a prorogued magistrate or a private citizen with imperium reentered Rome, he lost his military auspices for good. Cicero is eager to emphasize that C. Verres (praetor in 74 b.c.), after his formal departure for his province of Sicily as promagistrate, violated his military auspices by tracking back – repeatedly – to the city of Rome to make nocturnal visits to his mistress. That in turn (it is clearly implied) vitiated anything he did of worth in his province.20

The one significant exception in the matter of recrossing the city boundary has to do with the imperator, that is, the commander whose exploits have earned him his soldiers’ (ideally) spontaneous acclamation. A vote in the senate followed by popular ratification entitled such an individual to enter the city through Rome’s triumphal gate, which was in essence a hole in the augural space. A general who properly entered through it was entitled to retain his military auspices in the city for a single day so as to make a formal procession to the Temple of Jupiter on the Capitol. In the late Republic, we see commanders waiting outside Rome for periods up to almost five years in the hope of obtaining the requisite vote for that privilege, which brought lofty lifelong status. Their imperium remained valid in the meantime, even without explicit prorogation.

Magistrates in Collision

With consuls and praetors as direct heirs (each to their own degree) of the old regal imperium, it would be natural for many of them to feel the temptation to throw their weight around. But when push came to shove, in the city at least, members of the same college almost never used imperium to check imperium. One outstanding exception is found for 95 b.c. In this year the consul Q. Mucius Scaevola vetoed the decree of the senate (senatus consultum) that granted his consular colleague – L. Licinius Crassus, whose entitled conduct at Athens was noted earlier – a triumph for fighting some undistinguished tribes in Cisalpine Gaul.21 The two men had not been political enemies. It may be that Scaevola simply did not want to see Crassus benefit from the prestige of triumphing in the year of his magistracy. Thanks in part to the logistical problems posed by Rome’s ever expanding empire, this had become a difficult feat even by the mid-second century b.c. There are only about a dozen instances of such triumphs in the years 166–47 b.c., with the exceptional figures of Marius (in 104 and 101 b.c.) and Sulla (in 81 b.c.) accounting for three of them.

The power relationship between consuls and praetors had its complexities. The augur Messalla made it clear that consuls had the praetors as their colleagues, albeit lesser ones. After all, they were elected (at least originally, before the number of praetors swelled) on the same day in the same session of the centuriate assembly and thus under the same auspices. That said, occasionally we see consuls using their superior brand of imperium against individual praetors, curbing their activities in the realms of law, both civil (115, 77, and 67 b.c.) and criminal (57 b.c.), or in the matter of convening the senate (91 b.c.). Yet on one of these occasions (that of the year 67 b.c.) we find a remarkable show of praetorian solidarity in the face of a distinctly “uncollegial” show of consular power. When a consul smashed a praetor’s ceremonial chair for not rising in his presence, this praetor and his praetorian colleagues effected a “work slowdown” for the rest of the year, giving judgments only on routine legal matters.22

It is significant that for the later Republic we do not have a single secure instance of a praetor in the city using his imperium to veto a current colleague’s actions, even in the realm of civil law.23 Litigants who did not like a praetor’s actual decision customarily appealed, not to another praetor of the year, but to a tribune of the plebs, sometimes a consul. In cases where magistrates fail to show self-restraint on a larger scale, it is the tribunes or senate that might step in, usually in a reactive way. That sometimes even gave rise to a law circumscribing a behavior deemed offensive. A show of consensus by Rome’s ruling establishment often was an effective brake on those magistrates who insisted on exercising their full powers in the city – though of course that became less and less true in the last generations of the Republic, until we finally get to a situation such as that of 43 b.c., which we glimpsed earlier (“A Lecture on Legitimate Power”).

Let us leave aside for the moment the question of dynamics between magistrates outside the city and the senate and people. In the field, even in periods of relative stability, there was plenty of opportunity for mixed signals and conflicts just between Roman officials and their staffs. And when things heated up, neither tribunes nor senate were on the spot to intervene. One problem was that some provinces normally could not even be reached without trampling on others. A land march in the later Republic to Farther Spain demanded transit across two Gallic provinces and Nearer Spain. Bithynian and Cilician governors did not absolutely need to cut across part of Roman Asia, but they commonly did so anyway. When military glory was at stake, the chances of collision or noncooperation between ambitious magistrates and their staffs rose dramatically. This could lead to major military disaster, as the events of the year 105 b.c. show.24 But even subsequent to this fiasco, the battle of Arausio, reluctance on the part of Roman commanders to fight joint campaigns is amply documented.

Livy offers us an example of another variety of magisterial conflict in the field. In 195 b.c., a certain praetor named M. Helvius was marching out of Farther Spain after two inactive years in that province. His successor had given him a legion as a bodyguard for safe passage. However, Helvius is said to have taken over this force, fought a major battle against the native Celtiberians, and then put all the adults of a nearby town to death. On his return to Rome, he then asked for a triumph. The senate denied him “because he had fought under another’s auspices and in another’s province” – that is, in his successor’s province or in transit through Nearer Spain (the geography of the incident is unclear).

Yet, surprisingly, Helvius – despite his dubious technical claim and not particularly elevated social status – somehow managed to get an ovation, a lesser form of triumph. How did he do it? Perhaps he threatened to celebrate a protest triumph solely by virtue of his imperium on the Alban Mount (27 kilometers southeast of Rome), as a disgruntled consul had done in 197, Helvius’ own magisterial year.25

New Boundaries on Legitimate Power, 171–59 b.c.

Twenty-five years after the Helvius incident, the senate was in a less compliant mood. In 171 b.c., the consul C. Cassius Longinus crossed out of his proper province of “Italy” to attack Macedonia (though the war there had been allotted to someone else). The senate sent three legates to catch up with the consul, now on the move. The members of the embassy were not particularly distinguished, but whatever message they delivered obviously gave the consul Cassius quite a fright. He stayed as a military tribune in the East at least through the year 168 b.c., surely to avoid disciplinary action at Rome.

This incident crystallized a principle evident already in the Helvius episode: that a magistrate or promagistrate was expected to confine his activities to his assigned theater (provincia) except in emergencies or by special permission. That would seem to be a basic restraint essential to the smooth functioning of the Republic.26 But as it happens, our first clear example of the senate’s micromanagement of provincial commanders comes also from the year 171 b.c. It has to do with a praetor’s stern treatment of two pro-Macedonian towns in Boeotia that had surrendered to him. The senate instigated a fact-finding commission on the matter and soon passed at least one decree critical of the praetor’s conduct in the field. He later was condemned for these actions after his magistracy, a condemnation that led to his exile.

The case is important. The senate of course had some long-standing rights simply by established custom. One understandable formality was for magistrates departing for the field first to obtain the senate’s vote for funds and equipment. If a magistrate was traveling to his province by sea, the senate might circumscribe the route to be taken. (The return trip generally carried no stipulations regarding route or speed.) Or the senate might instruct the magistrate in his province or on the move, whether coming or going, to carry out special duties.

However, commanders in the general period of the middle Republic were very rarely successfully prosecuted for offenses committed in the field – otherwise only for “treason” (perduellio) after major losses of Roman troops. The prejudicial decree of 171 b.c. is in fact an apparently unprecedented example of the encroachment of the senate on a magistrate’s (originally absolute) powers of imperium within his province. There was a similar case in the next year, also concerning the East. The first provincial extortion trial came in the year 171 b.c. Soon afterward (169 b.c.) we find senatorial regulation even of the requisitions of magistrates in a theater of war.27

It was not only the magistracy that lost ground to the senate in Rome’s “constitution” at this time. As it happens, in roughly this same period, the senate seems to have stopped submitting its decisions regarding extension of magistrates in Rome’s organized territorial provinces (Sicily, Sardinia, the Spains) to popular vote, as it scrupulously had done down to at least the mid-190s b.c. Henceforth the senate acquired, in addition to its long-standing power of specifying magisterial provinces, sole right of “prorogation” – now a misnomer, since there was no rogatio (Latin for “legislative bill”) in the process.28 Still, the term prorogatio persisted in official contexts down through the Republic – a good example of the sometimes confusing conservatism of Rome’s administrative language.

It is a pity that we lose Livy’s continuous account in 166 b.c., before we can adequately trace developments like these further. But we know for a fact that by the year 100 b.c. there existed a small forest of regulations concerning administration not just in the territorial provinces but also in transit to and fro. We owe that knowledge to the discovery of a major inscription from Knidus in southeastern Asia Minor – a substantial fragment of a previously known pirate law – that dates to the year 101 or 100 b.c.

In the Knidus text we learn that even in case of abdication the commander was empowered, until his return to Rome (and so outside the assigned province), “to investigate, to punish, to administer justice, to make (legal) decisions, to assign arbitrators or foreign judges,” and to handle sureties, restitution of properties, and manumissions in the same way “just as in his magistracy it was permitted.” Apart from the surprising – indeed, paradoxical – point about abdication, this last section of the text offers a good summary of some of the attributes of imperium and the activities a commander might be expected to perform in his province and in transit. Yet the Knidus inscription also mentions limitations under a “Porcian law” – apparently new – on the movements of the commander and his staff.29 Without a decree of the senate, the commander is not to lead a military expedition outside his province. He must prevent members of his staff from doing so, too.

Quite possibly the M. Porcius Cato, who passed this bill (a praetor, although his precise identity and date are disputed), had taken over an old prohibition on a commander’s marching beyond his province – we have seen that the issue had been a burning one about three-quarters of a century earlier, in 171 b.c. To make his law, he simply added a new proviso, namely the extension of the prohibition to a general’s staff. In truth, it probably had long been a recognized principle that a commander was liable for the public actions of his traveling companions. But to turn that principle into law is another thing, for it gave the senate a particularly effective handle on the conduct of commanders in the field. Cicero, for instance, in prosecuting C. Verres on his return from Sicily in 70 b.c., made much of the rule that a commander had vicarious liability for underlings.

The comprehensive law on treason (maiestas) passed by L. Cornelius Sulla as dictator in 81 b.c. really marks a watershed in the history of this type of restrictive legislation.30 What details we can expressly assign to the law mostly have to do with ensuring orderly succession in the provinces, necessary for the smooth working of a new administrative system that Sulla had set up. For instance, Sulla demanded that a promagistrate spend at least one full year in his territorial province. That must be new, as we know that one governor of Asia of the mid-90s b.c. left his province after a mere nine months, with no personal repercussions. And under Sulla’s law a commander had to quit the province thirty days after succession. Before that law, some commanders were presumably hanging on for more than a month. One of the most significant things about Sulla in general was the scale on which he sought to transform the restraints of ancestral custom into positive law. The provisions on succession nicely illustrate the point.

Yet in the decades after Sulla we find others who are even more pessimistic about a Roman magistrate’s capacity for self-restraint. Cicero’s letters to his brother Quintus as governor of Asia in 60 and 59 b.c. are a mine of information on the formal and informal rules that now restricted a magistrate in his province. The end result of the process was Caesar’s hyperdetailed extortion law of 59 b.c., so comprehensive (and so severe) that it remained in effect all the way to the days of Justinian in the sixth century a.d. Among other things, Caesar even legally limited the number of the commander’s traveling companions, his “cohort of friends.” What is more, Sulla’s treason law remained in effect down to the end of the free Republic, alongside Caesar’s extortion measure.

Yet for all the creep of legislation, Roman commanders were highly skilled at finding the loopholes. The overarching impression we get is that it was no easy thing to call magistrates to account in the late Republic, especially if they were well connected. Furthermore, it is ironic that the same society that had such an appetite for legislation concerning provincial administration also acquiesced in the creation of any number of special mega-commands in which a single commander simultaneously held multiple provinces over a duration of several years. The most unusual of these was the five-year Spanish command Pompey received in his second consulship (55 b.c.), as he did not like the notion of actually going to Iberia. “His plan,” says one source, “was to let legates subdue Spain while he took in own hands affairs of Rome and Italy.”31 And that is what he did, allowing two senior legates to hold the Spains down through 49 b.c. There were precedents of sorts for this (most notably a consul of 67 b.c. who exercised control over Transalpine Gaul from Rome). But it was Pompey’s example that Augustus later seized on and expanded when he was seeking ways to place himself firmly at the center of his imperial system of government.

“Enhanced” Imperium, Succession, and Delegation

Pompey, in his third consulship (52 b.c.), instituted a thoroughgoing reform of Rome’s administrative system. Now, Sulla as dictator in 81 b.c. had introduced a scheme in which both consuls and all the praetors – he had brought their number to eight – were normally to remain in Rome for the year of their magistracy, to tend to civil affairs and the various standing courts. They then theoretically went as ex-magistrates to fight Rome’s wars and govern the various territorial provinces. Whether ex-consul or ex-praetor, Sulla gave each enhanced (i.e., consular) imperium, including those assigned to nearby Sicily and Sardinia.

Pompey modified some of these features. In an attempt to stem electoral bribery (and stymie his rival Caesar, should he win a second consulship further down the road), there was now to be a five-year gap between magistracy and promagistracy. Pompey also attempted to fix a curious built-in structural flaw of the Sullan system. Oddly, Sulla had allowed that an ex-consul or ex-praetor could refuse a territorial province after he had drawn a lot for it in the mandatory sortition. Pompey reversed the “voluntary” aspect of Sulla’s system and compelled previous refuseniks, such as Cicero (consul in 63 b.c.), to fill vacant provincial slots. The Pompeian law on provinces had one additional important feature: under this law, only ex-consuls were to receive consular imperium; ex-praetors got praetorian imperium.

At the time of Pompey’s reforms, Rome had fourteen territorial provinces: Sicily (acquired in 241 b.c.), Sardinia (238 b.c.), Nearer and Farther Spain (organized in 197 b.c.), Macedonia and Africa (acquired in 146 b.c.), Asia (bequeathed to Rome in 133 b.c. and secured by 129 b.c.), Cilicia (acquired c. 100 b.c., no doubt to keep wealthy Asia safe from piracy), Transalpine and Cisalpine Gaul (acquired in the mid-90s b.c.), Cyrene (acquired soon after 67 b.c.), Crete (acquired in 66 or 65 b.c.), and Bithynia (with Pontus) and Syria (organized in 61 b.c.). Our evidence suggests that, by the late Republic, the majority of commanders in armed provinces received the charismatic appellation imperator – and quickly, too. Where we can check – and this is one place where the numismatic evidence comes in handy – they invariably were designated imperator within a few months of arrival, no doubt as a hedge against supersession. For down to the year 146 b.c., the senate seems, whenever and wherever feasible, to have aimed at a policy of annual succession, though prorogation of commanders into a second year proved positively necessary for distant provinces like the Spains. Even after 146 b.c. – when an increase in the number of provinces outstripped the number of available magistrates with imperium (see “The Theology of Imperium” above) – the senate apparently kept plum provinces like Sicily and (later) Asia “annual.”

The pressure to maintain a strict policy of succession unquestionably came from within the ruling class itself. Properly elected magistrates no doubt resented the bottleneck that resulted when a previous commander in a coveted post was prorogued for one or more years. But annual succession made for a lot of to-ing and fro-ing by Rome’s provincial governors. It guaranteed plenty of transitions too. In any given year in the mid-second century, six provinces (permanent or provisional) were changing hands; in the late Republic, the number in rotation more than doubled.

It is remarkable that the system worked at all. For the governors, there were (notionally) short commands, sometimes long and dangerous journeys, and no permanent administrative support in the provinces for bureaucratic continuity. One thing that made a province particularly hazardous – leaving aside military threats – was a hostile lame-duck governor. Cicero explains the psychology of one nasty decessor (the technical Latin word for an outgoing commander) leaving Sardinia in the mid-50s b.c. thus: “He wished all possible failure to [the new governor], in order that his own memory might be more conspicuous. This is a state of things which, so far from being foreign to our habits, is perfectly normal and exceedingly frequent.”32 Several months before himself taking up a consular province in 51 b.c., Cicero found himself writing to this very man – Appius Claudius, now holding Cilicia – begging him to make the transition easy.33 This Appius did not do, instead tarrying in the province and holding a competing circuit court. It could (and did) get much worse.34

So how to ease succession outside the city? One increasingly common answer in the later Republic was for a commander not to wait for supersession but to delegate his authority to a subordinate and start home early. The practice was too convenient to attract much critical notice, as far as we can tell. Indeed, in contrast to the delimitation of imperium seen in the preceding section, delegation is one area where over time we can detect a definite broadening of the magistrate’s powers.

During most of the Republican Period, it seems certain that an individual could not delegate imperium at his own level. We have seen that principle from our case of 295 b.c. (in “The Theology of Imperium”), where a departing consul made his subordinate (merely) pro praetore to lead his army. In fact there is no instance of a special consular command granted by a consul in Rome or in the field. A consul could give out only praetorian imperium. And despite what seems to be a universally held notion, there is no strong positive proof that the urban praetor – or any holder of praetorian power – had the ability to delegate his imperium at all. However, on instructions of the senate, he could choose a suitable individual and secure for him in a legislative assembly a special grant of imperium.

At some point, praetors (or even nonmagistrates) with enhanced (i.e., consular) imperium could start making men pro praetore. This was obviously a major development. Indeed, it may be that one of the major factors behind the decision to institutionalize grants of consular powers to praetorian commanders for distant provinces (see “The Theology of Imperium”) was precisely to empower them to delegate imperium. In the Spains, Macedonia, Africa, Asia, and Cilicia, the seamless succession of proper governors was not easy to achieve, and praetors or quaestors might find themselves in sole charge of a large province for longish stretches.35 Starting in the late second century b.c., this type of delegation by praetors is reasonably well attested. We can suppose that the practice grew only more common after Sulla took the step of generalizing consular imperium for promagistrates in all the territorial provinces. But a startling thing happened after Pompey, in 52 b.c., modified Sulla’s system by completely divorcing the magistracy from the promagistracy and then restoring praetorian imperium as the standard grade for praetorian governors. We now find for the first time men who were pro praetore delegating imperium at their own level.36 One wonders whether the college of augurs had occasion to comment on the practice. Though doubtless convenient – even necessary, after Pompey’s overhaul of the administrative system – it is hard to see how it makes doctrinal sense.

Behind the Institutions: Further Dynamics of Getting and Wielding Power at Rome

To have held imperium, received the charisma-enhancing acclamation of imperator, and celebrated a triumph conferred almost incalculable prestige on a Roman. But for an ambitious politician under the Republic, a little comitas (“affability”) at times also might go a long way. Take Lucius Hostilius Mancinus, who as a legate in the Third Punic War held the technical distinction of being the first Roman officer to breach the walls of Carthage, though almost destroying himself and his force in the process. Once extricated (and dismissed from the theater), Mancinus managed quickly to win a consulship for the year 145 b.c. against formidable competition. How? On his return he had set up in the Forum a detailed painted representation of the siege of Carthage; standing at hand, we are told, he charmed onlookers by personally explaining the painting’s (presumably self-aggrandizing) particulars. This bold exercise in self-rehabilitation infuriated the great Scipio Aemilianus, who had saved Mancinus’ skin in 147 b.c., sent the legate packing, and then actually captured Carthage in the year that followed. Mancinus’ presentation undoubtedly made no more favorable an impression on an electoral competitor, Q. Caecilius Metellus, who in a praetorian command had just conquered and organized Macedonia for the Romans, earning a triumph and (uniquely for a subconsular magistrate in the Republic) a triumphal sobriquet from the senate for his achievements. But Metellus “Macedonicus” had a nasty reputation for harshness of personality (severitas). This evidently counted for something even in the eyes of the wealthy citizens who dominated the voting units in the relevant electoral body for higher magistrates, the centuriate assembly. For Metellus came up empty-handed at these elections and for the year that followed, winning the consulship with difficulty only for the year 143 b.c.37

This lesson in the value of public relations was not lost on L. Mancinus’ cousin Gaius, who experienced a positively disastrous consulship in 137 b.c. His story is an intricate one38 but seems worth telling in detail, for it illustrates unusually well some of the intangibles at work behind Rome’s political institutions. Fighting an unpopular war in the province of Nearer Spain, C. Mancinus and his army found themselves defeated and trapped before the small but powerful city of Numantia. The consul felt that his only recourse was to have his quaestor, Ti. Sempronius Gracchus (the future reforming plebeian tribune of 133 b.c., who had his own inherited Spanish connections), hammer out a surrender treaty with the Numantines. The junior staff officer’s truce won safe conduct for the army. But those back in Rome wanted no part of it, especially since just two years previously the consul Q. Pompeius had contrived and then reneged on an unconditional surrender to this same Spanish people. Mancinus was recalled (most unusually) during his year of office, and a serious investigation and public debate ensued.

An embassy from Numantia arrived to urge ratification of the treaty; Numantines had been in Rome as recently as 138 b.c., to complain against Pompeius, but we are told that that man’s vigorous self-defense and personal influence (gratia) allowed him to escape punishment.39 Mancinus had to walk a rockier road. In his case, some hard-liners in Rome drew parallels with a notorious episode from a fourth-century war against the Samnites and demanded that all the officers who had sworn to the unauthorized agreement, as after the Caudine Forks affair of 321 b.c., be handed over to the enemy. In the end, the senate advised and the people approved a compromise solution on the motion of both consuls of the year 136 b.c., almost certainly in the centuriate assembly. The treaty was to be rejected. And to expiate the state for its action, the new commander for Spain (a consul of 136 b.c.) and one of the specialized Roman priests of military ritual known as the Fetiales were to hand over only the disgraced former general, stripped and bound, to the Numantines. Significantly, as the commander at the Caudine Forks is said once to have done, Mancinus himself had argued before the Roman people in favor of his own surrender.

But in a dramatic and consequential turn of events, the Numantines refused to accept Mancinus. The Roman force in Celtiberia then brought back the ex-consul with due ritual into its camp, and he returned from there to Rome (it was probably now 135 b.c.), thinking that was that. He even unhesitatingly tried to take up again his proper place in the senate. It seems that the current pair of censors – whose first task of their eighteen-month term would have been to draw up the album of senators – had upon entering office in 136 b.c. included the ex-consul in the list despite his disgrace. These individuals, Ap. Claudius Pulcher and Q. Fulvius Nobilior, may have been especially sympathetic to Mancinus. Pulcher (consul in 143 b.c.) was father-in-law to the quaestor Ti. Sempronius Gracchus, and Nobilior, as consul in 153 b.c., had suffered a serious reverse at the hands of the Numantines, after which he was trapped in the same spot as Mancinus.

Much less generous in spirit toward Mancinus was a certain P. Rutilius, one of the ten tribunes of the plebs in the year of Mancinus’ return. Appealing to established precedent (generally or specifically, we do not know), he ordered that the ex-consul be led out of the senate on the grounds that, after his ritual surrender, he was no longer a citizen. Apparently, this took Mancinus by surprise; if the tribune held public meetings (contiones) on this matter, as was customary to build support for actions on contentious issues, he did so only after standing in the way of the ex-consul. In fact, the legal question whether the tribune was justified in ejecting Mancinus from the senate as if a foreigner, and no doubt the manner in which he did it, sparked massive dissension in the city. Eventually (so it seems) the issue came to a trial, and the opinion prevailed that Mancinus had indeed lost his citizenship – and with it his freedom and legal personality, not to mention his place in the senatorial album.

Mancinus may have started a press for rehabilitation immediately, perhaps even before Scipio Aemilianus, elected to a second consulship for 134 b.c., went on to level Numantia. We are told by a late source that Mancinus managed to have his citizenship restored by popular law. He also must have reentered the senate, for two late sources state that he attained high office again, namely a (second) praetorship. This marks a volte face on the part of the people, who in 135 b.c. had been willing to surrender Mancinus as a scapegoat. One other detail of Mancinus’ later career has come down to us: he dedicated a statue of himself in the same guise in which he had been handed over at Numantia, stripped and bound.40 It is a shame that we cannot date that last item with precision. Presumably he set up the statue after the law (passed by the people or conceivably the plebs) that reinstated him as citizen. It is a reasonable guess that the statue was an emotionally manipulative artistic creation that showed his physical person to maximum effect and that he aimed for it to help him in an electoral bid, whether for a junior office that might qualify him for the senate, for his second praetorship, or even for another consulship. (One remembers the acumen of his cousin L. Mancinus, who used his visual presentation skills to gain a consulship for 145 b.c.) Although Mancinus never returned to his former full consular status, he did win something that arguably counts for even more, namely favorable assessments from later writers (including Cicero and Plutarch).

That in its basics is the story of the consul C. Hostilius Mancinus. Probe a bit deeper, and glimpses of the extra-institutional political processes of Rome’s Republic present themselves at practically every juncture. The first oddity concerns an ostensibly sacred ritual, the sortition of provinces. Plutarch comments how the quaestor Ti. Gracchus had drawn as his lot to campaign with C. Mancinus, “not a bad man, but the unluckiest Roman commander.”41 Leaving aside the issue of Mancinus’ luck, it certainly was an amazing coincidence that Gracchus, the eldest son and namesake of a man who as a praetor for Nearer Spain in the early 170s b.c. had forged a peace with the Numantines, was allotted that very theater as his quaestorian sphere of responsibility (provincia). Too amazing a coincidence, we surely must surmise. As it turns out, the Romans had a quasi-technical term for the patently manipulated assignments that might fall to the well-connected: the sors opportuna, or lucky draw of the lot.

Personal considerations surely also influenced the relationship of the enemy Numantines to Rome. As we have seen, they inflicted a great deal of damage and shame on a series of Roman forces in the field, in the end capturing Mancinus’ camp and its contents. Yet Plutarch tells the story that they graciously acceded to Ti. Gracchus’ request that they restore to him his quaestorian account books – based on the trust and friendship that arose from his inherited personal connections (clientela) – and that they would have given him anything else he wanted. Matters soon grow fuzzier for the modern observer. When the Numantine ambassadors followed Mancinus back to his city, Dio (fr. 23.1) tells us that they were met (as was customary for enemies) outside Rome’s walls: the Romans wanted to show that they denied a truce to be in effect. But the Romans – that is, the senate, the competent body for dealing with foreign embassies – still made sure to send them ceremonial gifts, “since they did not want to deprive themselves of the opportunity to come to terms.” So even at this stage senatorial opinion was not hardened regarding the conduct of the war in Spain. And the Numantines, for their part, are said to have spoken in the public debate against the notion of sacrificing Mancinus and the members of his staff who had formally sworn to the treaty. Thus it is reasonable to think that by the time Mancinus argued in favor of his own ritual surrender, he had grown confident of his own personal safety vis-à-vis the Numantines42 and perhaps even envisioned a soft landing in Rome to follow.

The quaestor Ti. Gracchus had developed his own set of élite presumptions by the time of his return to the city. Dio says he had come back to Rome expecting to be positively rewarded for his conduct of the negotiations. Instead, he ran the risk of being delivered up with Mancinus to his own foreign clients. Gracchus, of course, escaped that fate, but he still had to endure the rejection of the Numantine treaty and the blow to his reputation for good faith (fides) that it entailed. Ancient writers, most notably Cicero and Plutarch, are adamant that it was this that alienated Gracchus from Rome’s senatorial establishment and impelled him to take up his reformist course as plebeian tribune in 133 b.c. Indeed, Plutarch details Gracchus’ frustration with Scipio Aemilianus, who, despite his prestige (and, we may add, relationship as cousin and brother-in-law), did not press for the ratification of the controversial truce. Nor, continues Plutarch, did Scipio Aemilianus try to save C. Hostilius Mancinus. But it really is too much to expect that Aemilianus would do much for the cousin of the man who tried to steal his thunder in the consular elections for 145 b.c. Indeed, it seems that in the investigation at Rome it was Gracchus who played a dubious part. Quaestors were magistrates of the Roman people and as such, strictly speaking, responsible for their own actions. (Legates and holders of purely delegated powers were different.) Our sources say nothing to indicate that Gracchus made an eloquent or forceful speech to advocate his treaty. Rather, they hint that he quickly distanced himself from his commanding officer when he found that he enjoyed greater support in Rome than Mancinus – and saw the Caudine-style penalty proposed. In all probability, Gracchus had been co-opted into the college of augurs by this time. One wonders, therefore, whether he was the ultimate source for the reports that Mancinus persisted in sailing to Spain despite a series of three adverse omens43 – reports so prevalent in our tradition and obviously meant to supply a theological explanation for the disaster at Numantia.

The tribune P. Rutilius, of course, provided yet another nasty twist amid these turns. His motivation? On the face of things, he was acting in a traditional tribunician role, as guardian of constitutional propriety, applying precedent as he found it. Furthermore, it seems that tribunes had only recently gained ex officio membership in the senate;44 it would be natural for them to police perceived usurpers of this prerogative. But in Rutilius’ blocking of Mancinus personal factors may again have been paramount – factors not all that directly connected with the ex consul. It so happened that in 169 b.c., a relative (also named P. Rutilius, probably an uncle) as plebeian tribune had come into serious conflict with the censors of the year. Those censors, as chance would have it, were the fathers of the censor of 136 b.c., Ap. Claudius Pulcher, and our quaestor Ti. Sempronius Gracchus; they retaliated with their formal powers just days after the tribune left his office and the immunity it offered. So for the younger P. Rutilius, the citizenship issue was an elegant way to settle a score now a generation old.45 In blocking Mancinus he simultaneously impugned the censors of 136 b.c. and the compilation of their senatorial album as well as (indirectly) the quaestor who had started the whole chain of affairs by negotiating the Numantine truce. There may be even more to Rutilius’ action, but as so often for almost all periods of the Republic, our sources allow us to go only so far.

Conclusion

The question of how much power should reside in the hands of individual magistrates in relation to central governing bodies is obviously central to any constitution, written or not. How well did the Romans of the Republic grapple with this conceptual challenge? One test is to ask how far their system succeeded in curbing its authorities when they went astray. Now, the res publica granted its magistrates (especially the senior ones) formidable powers. It allowed individuals the possibility of cumulating certain important posts. It tolerated to a remarkable degree the open exercise of personal influence in the political and even religious and military spheres. The senate put up with noisy and sometimes prolonged conflict among its members (within limits). Failed magistrates, even those who had suffered serious military defeats, had surprisingly (at least to us) ample scope for rehabilitation and reintegration into the ruling establishment.

Yet there was a rough system of informal and formal checks and balances in place that worked well enough over a period of some centuries to make figures such as Sulla and Caesar outsized exceptions. The simple principle that the empowered should observe a measure of self-restraint in the interest of political harmony (concordia) operated as a surprisingly efficacious force down to the end of the Republic. If magistrates ignored this tacit understanding or broke with what was accepted as precedent, the negative power wielded by tribunes – even the threat of its implementation – was often enough to make even senior magistrates back down.46 That was especially the case if an individual perceived that he did not have the necessary backing in the senate for what he was doing. Indeed, the senate itself was a most authoritative arbiter of what was or should be legal under the Republican “constitution.” Its recommendations (senatus consulta) might give rise to a consular investigation, such as we see in 136 b.c. in the Mancinus affair. Or they might prompt specific controlling legislation, passed by the people or (most quickly and conveniently) the plebs. It was in the last resort, it seems, that a magistrate of the Roman people might see fit to block directly another – usually lower – magistrate. As we have seen, members of the same magisterial college were loath to veto each other. To use one’s full magisterial power against a colleague was, at the least, construed as a serious affront to his personal dignity. In an extreme situation, it could seriously breach the concordia that bound together Rome’s governing class.

It was precisely to avoid such potentially destructive conflict that so much of Roman political power, in all periods, tended to direct itself through noninstitutional channels. Indeed, especially in the middle Republic, the reformer who wanted to define or otherwise delimit those channels might get quite a tussle if he placed elite prerogatives at risk. For example, Cicero reported a heated public debate in the mid-180s b.c. between the senior consul M. Servilius Geminus (consul 202 b.c.) and a M. Pinarius (Rusca, surely as tribune) over a law that attempted to regulate the career path (cursus honorum) by stipulating minimum ages for candidacy for various magistracies. The senatorial establishment, here as on previous occasions, was on the side of an unregulated cursus: the fewer electoral restrictions, the more scope for the free use of patronage and private influence. (In 180 b.c., however, another tribune finally pushed through a lex annalis that held force in its essentials until c. 46 b.c.) The ballot laws of the latter part of the second century b.c. also regularly saw stiff opposition, including the lex Cassia of 137 b.c., C. Mancinus’ consular year, which introduced secret voting to most popular trials. Yet with the accumulation of regulations like these, élite resistance apparently softened over time. In 67 b.c., the tribune C. Cornelius passed a law compelling praetors to follow their own edicts. The tribune’s aim probably was to prevent praetors’ ad hoc deviations in the administration of civil (perhaps also provincial) law prompted by favoritism or spite. We are told that many (i.e., many in the senatorial establishment) opposed the Cornelian law, but (significantly) they did not dare to speak openly against it.47

Let us turn to the institutional history of legitimate power. Here our investigation shows two parallel processes. The first had a “liberalizing” effect. To make their republic work, the Romans had to invent and exploit legal fictions such as prorogation, grants of imperium to nonmagistrates, and “enhanced” imperium for praetors. These particular innovations mostly had their origin in acute military crises, particularly those of the period down to c. 200 b.c. But they eventually found their way into the mainstream of administrative practice. Sulla’s and then Pompey’s constitutional reforms in the late Republic also brought qualitative changes to imperium. Pompey’s measures may even have attracted the attention of the augurs and required their approval. For once a pro praetore had the capability of delegating his official power to a subordinate of his choice in one of fourteen regular territorial provinces – and this is the situation we find after 52 b.c. – we really are quite far away from the notion of imperium as the united civil and military power held by the old kings as heads of state.

Yet the Romans of the middle and late Republic also sought to bring their commanders under closer control, curbing the originally absolute prerogatives of military imperium by incrementally transmuting what was accepted custom into positive law. In a way, this can be viewed as an attempt to project the situation of the city – with the rough-and-ready checks and balances afforded by collegiality, class consensus, and tribunician intercession (seen powerfully at work against C. Mancinus in 135 b.c.) – onto the unruly field, where there was at stake not just the orderly succession of commanders per se but also Roman lives, reputation, security, and wealth. The process culminated in Sulla’s treason law and the extortion law of Caesar, but it demonstrably had started some years before.

It would seem that the Second Punic War facilitated the development of explicit formal restraints on commanders. The senate’s leadership was never questioned in the seventeen years of this war, which was virtually one continuous state of emergency. There is good reason to think that after Rome’s victory the senate started to capitalize on the immense prestige it had accrued. As early as the 170s b.c., it may have acquired the sole right to “prorogue” – to determine how long commanders could hold territorial provinces – taking away that important prerogative from the people and plebs. By the time of the Third Macedonian War (171–168 b.c.), the senate clearly was dictating to commanders what they could do inside their military theaters, again bypassing the people in the process. What governors did outside their province also became at this time no less a cause for anxiety for the ruling establishment. We can speculate that it is this very period (or one soon afterward) that generated the first attempts at comprehensive rules circumscribing magistrates’ activity – rules that seem to have had uneven practical results, despite much subsequent elaboration.

Notes

1 For a brief sketch of what is known of early Roman specialized legal literature, see Honoré (Reference Honoré, Hornblower and Spawforth1996, 838).

2 For these latter two items, see Cic. Leg. 3.6–11.; Polyb. 6.11–58.

3 On the varieties of popular involvement in the res publica, see Millar (Reference Millar1998), which argues for the centrality of the city populace in the political system, especially in the years c. 79–55 b.c.

4 For an example from Cicero’s day (presidency of praetorian elections), see Brennan (Reference Brennan2000, 120–1), and cf. 55–6 on the censorship, on which see also the section “The Theology of Imperium” in this chapter.

5 Phil. 13.14–15.

6 Lepidus used the outstanding details of his great grandfather’s career to advance his own; see the coin issues collected in Crawford (Reference Crawford1974, 443–4), no. 419 (61 b.c.).

7 For this and what follows on the elder M. Lepidus, see Klebs (Reference Klebs, Pauly and Wissowa1893), coll. 552–3 (basic sources), and especially Münzer ([Reference Münzer and Ridley1920] Reference Münzer and Ridley1999, 158–65); cf. Ryan (Reference Ryan1998, 180–1).

8 Münzer ([Reference Münzer and Ridley1920] Reference Münzer and Ridley1999, 158).

9 Imp. Pomp. 60.

10 See the general discussion of this passage by Lintott (Reference Lintott1999, 4–5).

11 Cic. De or. 3.75 (cf. 1.45); on this incident, see also Habicht (Reference Habicht1997, 294).

12 For nonmagistrates overawing provincial communities, it is hard to top Cicero’s colorful description of the young C. Verres in transit as a commander’s legate to the Roman province of Cilicia: see especially Ver. 2.1.44–6, 49–54, 60–1, 86, 100. Other examples (from a large selection): Polyb. 28.13.7–4 (169 b.c.); and cf. Cic. Div. Caec. 55 and SIG3 748 (74–71 b.c.).

13 See, in general, Jocelyn (Reference Jocelyn1971, 44–51); Linderski (Reference Linderski1995, 560–74, 608f); and on Romulus’ founding of the city, Linderski (Reference Linderski2007, 3–19). There is good reason to believe that the plebeian assembly and the tribunes eventually developed some complementary auspical process; see Badian (Reference Badian and Linderski1996a, 197–202).

14 Bleicken (Reference Bleicken1981, 37, and n. 38). On developments in the use of the word imperium (as well as provincia) in the Republic and earlier empire, the standard treatment is now Richardson (Reference Richardson2008).

15 Mommsen (Reference Mommsen1887, 90).

16 On the auspicia and imperium of the consul without fasces as “dormant,” see Linderski (Reference Linderski1986, 2179, n. 115). When in the field together, the consuls rotated the auspices every day.

17 Livy 10.29.3.

18 Gell. 13.15.7.

19 Agr. 2.26.

20 Cic. Ver. 2.5.34; cf. 2.2.24.

21 Cf. Cic. Inv. 2.III with Pis. 62; also Asc. pp. 14–15 Clark.

22 Dio Cass. 6.41.1–2.

23 On an alleged instance of 74 b.c. (Cic. Ver. 2.1.119), see Brennan (Reference Brennan2000, 447).

24 On which see the sources collected in Broughton (Reference Broughton1951, 555).

25 On Helvius, see Livy 34.10.1–5, with the further references in Broughton (Reference Broughton1951, 341). Alban triumphs are recorded for the years 231 (the first), 211, 197, and 172 b.c. After that last instance, it seems to have become something of a joke, or illegal, or both; see Brennan (Reference Brennan2000, 148–9).

26 See Livy 43.1.10–12, 44.31.15; cf. Badian (Reference Badian, Hornblower and Spawforth1996b, 1265).

27 See Brennan (Reference Brennan2000, 172–3, 213–4); cf. Lintott (Reference Lintott1993, 98–9).

28 See Brennan (Reference Brennan2000, 187–90) for speculation on how precisely the senate managed to aggrandize itself in this way.

29 The relevant passages are Crawford (Reference Crawford1996, 12), Kn. IV, lines 31–9, and Kn. Ill, lines 1–15.

30 For what follows, see (Brennan Reference Brennan2000, 399–400).

31 Dio Cass. 39.39.1–4.

32 Cic. Scaur. 33.

33 Cic. Fam. 3.3.1.

34 For an egregious example of noncooperation, consider the father of the great L. Licinius Lucullus (consul 74 b.c.), who fought as a praetorian commander in Sicily in 103 (Broughton Reference Broughton1951, 564, 568; also Alexander Reference Alexander1990, 35–6, no. 69), or Cn. Pompeius Strabo, who is said to have killed the consul who came to succeed him in an Italian command of 88 b.c. (references in Broughton Reference Broughton1952, 40), and also the actions of his son, Pompey the Great, in the East in 67 (Dio Cass. 36.19.1–2, 45.1–2) and 66 b.c. (on which see especially Plut. Pomp. 31.1, Luc. 36.1, 4–7; Dio Cass. 36.46.2).

35 Apparently, the earliest evidence for the practice of “praetorian delegation” has to do with the orator M. Antonius, attested as quaestor pro praetore in the province of Asia in (probably) 113/112 b.c. (IDélos IV 1 1603).

36 Apparent from IGRom IV 401; cf. Joseph. AJ 14.235.

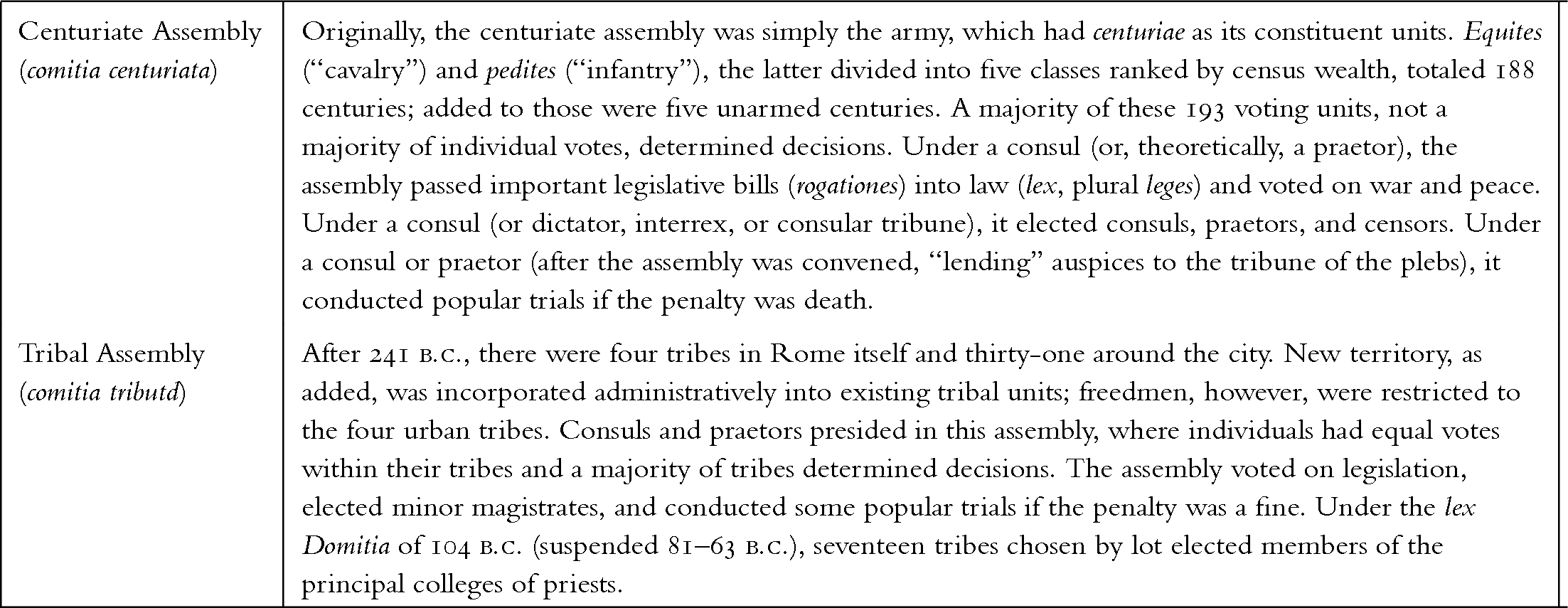

37 For sources on L. Mancinus, see Broughton (Reference Broughton1951, 462, especially cf. n. 3 with Plin. NH 35.23 on his presentation in the Forum). For Q. Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus as consular candidate, see Broughton (Reference Broughton1991, 8–9). The tribal assembly (comitia tributa), where the predominant organizing principle for the voting units was place of residence rather than property qualification, was also attuned to the personalities of candidates who sought election to lower offices; cf. Val. Max. 7.5.2 (precise date uncertain, but possibly c. 144 b.c.) with Broughton (Reference Broughton1991, 40–1).

38 Full sources in Broughton (Reference Broughton1951, 484, 486–7; Reference Broughton1986, 104). The most expansive recent discussion of this man’s consulship and the aftermath is Rosenstein (Reference Rosenstein1986). See also Brennan (Reference Brennan1989, 486–7) for some of the legal questions involved.

39 Cf. App. Hisp. 79.343–4 with Cic. Rep. 3.28, Off. 3.109, and Vell. Pat. 2.1.5.

40 For details of Mancinus’ later career, see Dig. 50.7.18 (citizenship and second praetorship), De vir ill. 59.4 (the praetorship), and Plin. NH 34.18 (his statue).

41 Ti. Gracch. 5.1.

42 On this basic point, see Badian (Reference Badian1968, 10–11).

43 On these religious aspects, see Rosenstein (Reference Rosenstein1986, 239, and n. 28); see also Broughton (Reference Broughton1951, 495–6) on the composition of the college of augurs in this general period.