6 - Fantaterror: Gothic Monsters in the Golden Age of Spanish B-Movie Horror, 1968–80

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 06 May 2021

Summary

The portmanteau ‘fantaterror’ amalgamates the terms ‘fantástico’ (literally ‘fantastic’, although in Spanish the word conveys a meaning closer to that of ‘supernatural’ in Anglophone cultures) and ‘terror’ (indistinguishable from ‘horror’, but more ubiquitous). Popularised by director, scriptwriter and actor Jacinto Molina, famous under his artistic name Paul Naschy, fantaterror was coined to refer to the Spanish answer to the type of violent and titillating films that have come to be known as ‘exploitation cinema’ within the European and American contexts (Mathijs and Mendik 2004; Shipka 2011). Since ‘exploitation cinema’ may also cover genres such as the Western or softcore films, other terms have cropped up to refer to the horrific side of the transgressive and provocative B-movie cinema that flooded Spanish screens in the 1960s and 1970s. ‘Euro-horror’ is a popular label in the Anglo-American world, but Spanish cinema critics and writers, in an attempt to emphasise the uniqueness of the various occult, dark, sensual and weird elements of films such as La residencia / The House That Screamed (Narciso Ibáñez Serrador, 1968) or Mil gritos tiene la noche / Pieces (Juan Piquer Simón, 1982), have come up with other less catchy ones like ‘cine bizarro’ (bizarre cinema) (Diego 2014) or else simply called them ‘cine negro’ (film noir) (Luque Carreras 2015). Seldom does one find ‘cine de terror’ (horror cinema) explored as such in Spanish scholarship; it is normally discussed in broader surveys of supernatural cinema (cine fantástico), which sometimes mingle horror, science fiction and fantasy. The word ‘Gothic’ has been used even more rarely by those who have most rigorously studied the country's horrific output. The term has only gained currency, unsurprisingly, in Anglo-American academia, where scholarly interest in the Gothic has been systematically developing since the 1980s and, especially, since the 1990s.

Given Spain's reluctance to acknowledge the Gothic as a national mode, a stance born out of many decades of the sustained critical championing of social realism as the quintessential artistic form of expression for the country's writers, fantaterror now stands as the most productive term with which to refer to genre filmmaking between 1968 and 1980, the golden age of Spanish horror.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

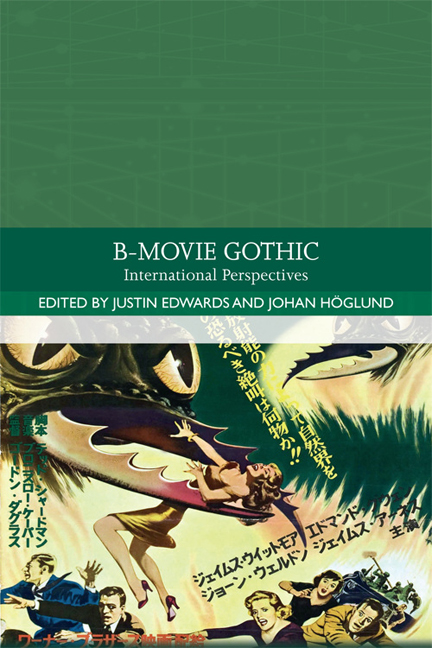

- B-Movie GothicInternational Perspectives, pp. 95 - 107Publisher: Edinburgh University PressPrint publication year: 2018