Book contents

- Binomials in the History of English

- Studies in English Language

- Binomials in the History of English

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1 Defining and Exploring Binomials

- Part I Old English

- Part II Middle English

- Part III Early Modern English

- Part IV To the Present

- References

- Index of Binomials and Multinomials

- General Index

- References

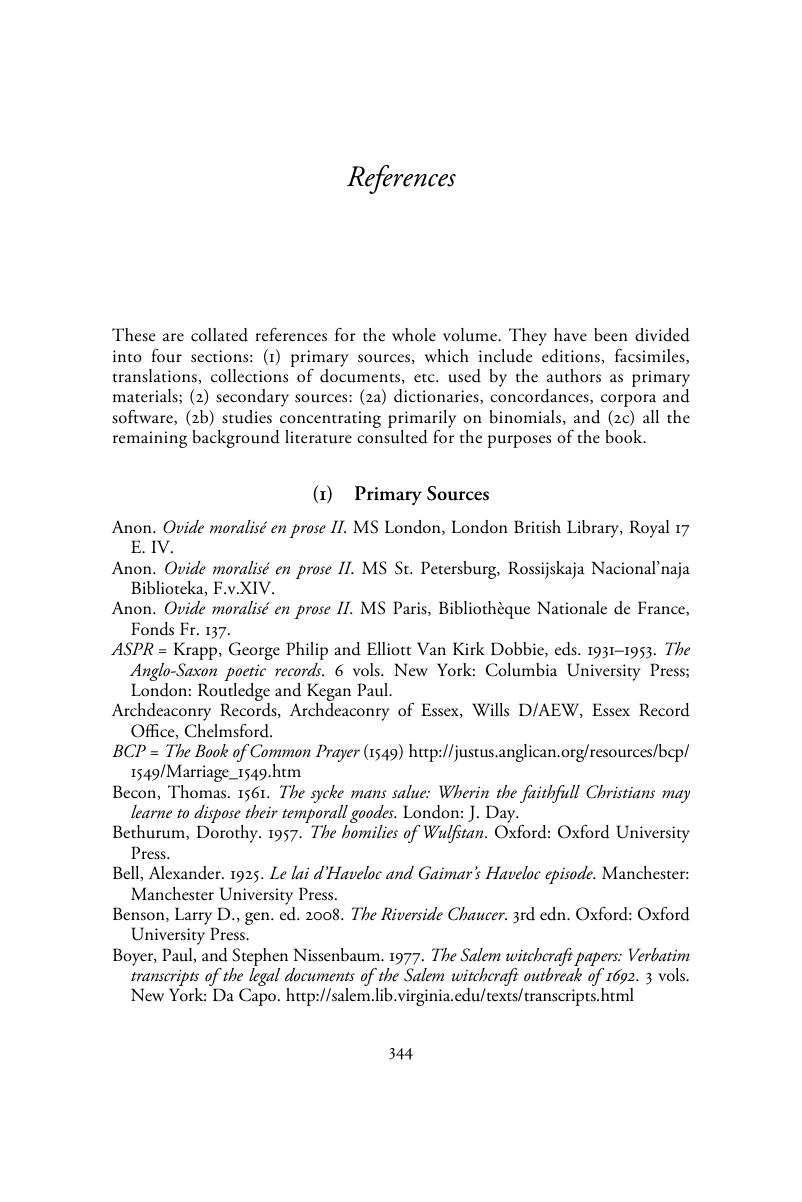

References

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 July 2017

- Binomials in the History of English

- Studies in English Language

- Binomials in the History of English

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1 Defining and Exploring Binomials

- Part I Old English

- Part II Middle English

- Part III Early Modern English

- Part IV To the Present

- References

- Index of Binomials and Multinomials

- General Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Binomials in the History of EnglishFixed and Flexible, pp. 344 - 370Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2017