1. Introduction

This section examines the inclusion of transnational crimes within the jurisdiction of the Criminal Chamber of the African Court of Justice Peoples and Human Rights (hereinafter the African Court or Criminal Chamber as suits) by the Statute of the Court as amended by the Malabo Protocol (hereinafter the Statute). Under Article 28(A) of the Amended Statute the Court ‘shall have power to try persons for the crimes provided hereunder’ inter alia:

(4) Unconstitutional change of Government

(5) Piracy

(6) Terrorism

(7) Mercenarism

(8) Corruption

(9) Money Laundering

(10) Trafficking in Persons

(11) Trafficking in Drugs

(12) Trafficking in Hazardous Wastes

(13) Illicit Exploitation of Natural Resources

If this potentially bold and distinctive expansion of jurisdiction leads to an establishment of a functioning court with an effective jurisdiction, the AU will have taken a major step beyond other regional measures such as the EU’s capacity to declare regional offences obliging member states to implement them or the quasi-criminal jurisdiction of the Inter-American court of Human Rights.Footnote 1

This expansion arose out of the study by Donald Deya for a criminal chamber within the African Court commissioned by the AU and submitted in 2010.Footnote 2 These transnational crimes were included within the amended draft ACJHR protocol released in 2011Footnote 3 and in the amended protocol adopted by the African Heads of States and Governments in Malabo, Equatorial Guinea, on 27 June 2014.

This chapter introduces some of the reasons for the expansion of jurisdiction, and some of the substantive, procedural and institutional problems that will need to be overcome to operationalise this new jurisdiction. It begins, however, with the nature of this jurisdiction.

2. A Regional Transnational Criminal Court Prosecuting Regional Transnational Crimes

Fortunately, the heated debate about the Chamber’s compatibility with the Rome Statute and the ICC’s jurisdiction is not relevant to assessment of this expansion because these transnational crimes were never included in the ICC’s jurisdictionFootnote 4 and there is no issue of the Chamber being used to protect its leaders from prosecution for core international crimes before the ICC.Footnote 5 The inclusion of these crimes within the jurisdiction of the African Court takes us back rather to the debate at Rome about the inclusion of certain treaty crimes within the jurisdiction of the ICC, and many of the arguments raised in regard to the appropriateness of developing international jurisdiction over treaty crimes remain pertinent to exploring what this expansion means and why it was undertaken.Footnote 6

The transnational crimes inserted into the African Court’s jurisdiction are not international crimes in the strict sense of the word. Some are defined in existing AU instruments, some are from more general instruments, and some are sui generis. Some of these crimes are peculiar to Africa. Unconstitutional change of government, for example, is a major concern for Africa and while the African Charter on Democracy Election and Governance (ACDEG),Footnote 7 adopted in 2013, obliges AU member States to ‘take legislative and regulatory measures to ensure that those who attempt to remove an elected government through unconstitutional means are dealt with in accordance with the law’, the Protocol creates an explicit regional international crime in this regard.Footnote 8

The treaties that define certain of these actions merely create obligations on states to enact criminal offences in their domestic law. They are not actually crimes in international criminal law, but only in domestic criminal law.Footnote 9 The possible exception to this is the status crime of mercenarism, because Article 3 of the UN Mercenaries Convention provides that someone who fits the definition of a mercenary ‘commits an offence for the purposes of this convention’. However, the Convention imposes legal obligations on States to take action under their domestic law and no international jurisdiction is provided for. If the specific UN or AU crime suppression conventions do not create these crimes, what does?

Interpreting the proposed jurisdiction of the African Court over the transnational crimes depends on how the Criminal Chamber’s transnational crimes jurisdiction is conceptualised: is it a stand-alone regional court exercising its own inherent jurisdiction over transnational crimes or is it a delegate of the States parties of the Protocol exercising their delegated jurisdiction. If it is the former then the Criminal Chamber (a) applies its own substantive crimes, (b) establishes its own jurisdiction and (c) applies its own procedures for cooperation, and it does not matter if the State party where the offence occurred has not established the crime, the jurisdiction, or the procedures. If it is the latter then the State party where the offence occurred will (a) have to establish the offence, (b) have to establish the jurisdiction, and (c) have to establish the procedure, before all of these can be delegated to the Court.Footnote 10 Conceptually, the Court’s jurisdiction over transnational crimes fits more aptly into the extant global scheme of transnational cooperation against transnational crime if the Criminal Chamber is seen as the delegate of States parties, working within that system to suppress transnational crimes that until now have only been crimes in national law subject to multilateral obligations to cooperate and not as crimes applying individual criminal liability in international law. Yet that is not what the AU has done. Article 3 of the Protocol states that the Court is vested with original jurisdiction while Article 46E bis (1) says that States Party accept the jurisdiction of the court with respect to the crimes in the Statute. It thus seems clear that the Court has original jurisdiction over these crimes – it is, to coin a phrase, a stand-alone regional transnational criminal court. The complementarity provision Article 46H (1) states that ‘the jurisdiction of the Court shall be complementary to that of the national courts, and to that of regional economic communities where specifically provided for by the Communities’, which implies that the chamber is to function in regard to these crimes as to others in much the same fashion as the ICC does to States parties of the Rome Statute.

It is the Protocol that lists these crimes, defines them, and expressly provides that the Court shall have the power to try them. This is clarified by article 46B(1) which provides that ‘a person who commits an offence under this Statute shall be held individually responsible for this crime’ and which suggests that (a) the Statute itself creates these crimes, and (b) that given individual responsibility is being applied, the crime is by definition no longer just a transnational crime but is, at least within Africa, a regional international crime (i.e. a supra-national crime in the region, rather than just a crime in the domestic law of AU Member States). Du Plessis questions the law-making authority of the AU in this regard, noting that the AU’s Constitutive Act,Footnote 11 and more specifically, article 4(h), only gives the AU power to take measures ‘to intervene in a member State’ in respect of the three categories of core international crimes: war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity, but Nmehielle counters that there is nothing in these provisions limiting intervention to military action.Footnote 12 Du Plessis’s argument in regard to Article 4(h) only bites if the Criminal Chamber’s jurisdiction over transnational crimes is regarded as fundamentally interventionist. Although they do not expressly sanction intervention, other principles of the AU Constitutional Act spelled out in Article 4 relate to this goal including the promotion of social justice, promotion of peace and security, human rights, democratic principles and primarily ‘the rule of law and good governance’.Footnote 13 It would be more appropriate to consider the Criminal Chamber’s jurisdiction over transnational crimes as being more in line with the regime in transnational criminal law, by serving as a further venue to prosecute difficult cases with the cooperation of the territorial State. Article 3 of the Constitutive Act does provide for objectives of the promotion of a range of social goods by the Union and in article 3(d) the promotion of ‘common positions on issues of interest to the continent and its peoples’; the Protocol does promote a common position – regional prosecution – in regard to certain transnational crimes.

When transnational crimes are moved from a national to a regional jurisdiction that identifies a regional interest; it does not shift these crimes into the general international jurisdiction and, as of yet, there is no general support for doing so. In a sense the AU is more the agent of the State than of the international community in this regard. But in regionalising these crimes it is irreverently challenging the power balance that currently reflects the fact that international criminal law is generated by the international community and transnational criminal law is generated by certain influential states and regions, that in essence it reflects the interest of one State in pursuing individuals who break its laws transnationally. The AU is taking up that interest, on behalf of States within the region. Why is it doing so?

3. The Reasons for Establishing the Criminal Chamber’s Jurisdiction over Transnational Crimes

This expansion appears to have been undertaken for various reasons.Footnote 14

First, out of regional interest.Footnote 15 It was felt necessary to enable Africa to prosecute these crimes like terrorism committed by non-state actors because they are of particular resonance to Africa. One potential group of accused are members of African political and economic elites allegedly involved in transnational crimes who enjoy relative impunity in their own States. The Court may serve to avoid prosecution of African leaders abroad by dealing with these matters in Africa. Commentators have noted the negative reaction in Africa to a French Court’s issue of indictments for corruption against five serving African presidents in 2009.Footnote 16 The enthusiasm of African states for criminal prosecutions of these individuals before the Court has, however, been questioned.Footnote 17 Yet there are few prosecutions in foreign courts of transnational crimes committed by African leaders. African nationals do, however, engage in transnational criminal activity both in African and abroad. Nigerian drug trafficking organisations have, for example, proliferated globally.Footnote 18 Foreign nationals engage in trafficking of all kinds in Africa, through Africa, and from Africa. It is more likely that there will be pressure to use the Criminal Chamber to resolve problems of capacity in African states in regard to a swathe of offences of a transnational nature. The temptation of international criminal justice is that it will provide a forum to resolve this problem of incapacity but the Criminal Chamber neither can nor, it is submitted, should it in regard to all but the most serious offences of concern to Africa.

Second, in order to remove impunity from corporations operating in Africa that engage in criminal conduct.Footnote 19 Africa’s unsatisfactory experience of the implication of corporate entities in certain exploitative crimes that impact negatively in Africa is clearly at the heart of the expansion.

Third, because of inter-African difficulties in cooperation. It is clear that States within Africa are worried about transnational crimes and the political difficulties of extradition. They seek a neutral non-State venue for prosecution (which is very similar to CARICOM’s motivation for expanding the jurisdiction of the ICC over transnational crimes).Footnote 20 The AU has not, however, backed CARICOM’s efforts to expand the jurisdiction of the ICC because it is not a party to the Rome Statute, and because it feels that the Rome Statute does not entirely fill this field of normative endeavour.

Fourth, because of AU legislative activity or pronouncement in regard to the particular crime. Nevertheless, the list is not comprehensive. It omits for example, trafficking in small arms, smuggling of migrants, and the illegal trade in wildlife, all major transnational crimes and subjects of concern for the AU.Footnote 21 It also omits participation in an organised criminal group, the key offence in the UN Convention against Transnational Organised Crime,Footnote 22 to which every African State is a party except Somalia and the Republic of the Congo.Footnote 23

Fighting impunity is the overall goalFootnote 24 of including these crimes within the jurisdiction of the Criminal Chamber. The other goals set out in the preamble relevant to this expansion of jurisdiction do suggest a concern with the maintenance of legitimate internal sovereignty of African States and defence of social and individual rights. The relevant goals include the following: ‘respect for democratic principles, human and people’s rights, the rule of law and good governance’; ‘respect for the sanctity of human life, condemnation and rejection of impunity and political assassination, acts of terrorism and subversive activities’; and ‘to promote sustained peace, security and stability on the Continent and to promote justice and human and peoples’ rights as an aspect of their efforts to promote the objectives of the political and socio-economic integration and development of the Continent’.Footnote 25 While these goals are sufficiently general to justify the enactment of these crimes, they do not cover the goals of specific offences. Where, for example, is respect for the environment which underlies the trafficking in hazardous waste offence? Commenting more generally Du Plessis notes that these crimes will force the Chamber to tackle ‘a raft of … social ills that plague the continent’.Footnote 26 This is but one of a number of potential difficulties with this expansion.

4. Contextual Factors Applicable to all Transnational Crimes within the Jurisdiction of the Criminal Chamber which may Complicate their Application

A. The Importance of Not Undermining Existing Treaty Regimes for the Suppression of Transnational Crime

The definitions of many of the transnational crimes are drawn from the criminal provisions in treaties that are central to different ‘prohibition regimes’ in transnational criminal law. While there are some variations in the definition of crimes between regional and global suppression conventions, on the whole there is a remarkable degree of consistency. These ‘crimes’ serve as conditions for the operation of prohibition regimes that serve as bridges for cooperation between States and are the focus of institutional development around the world, of legal practice, and of expertise. African states play an important part in these regimes. The elevation of these transnational crimes to the status of a regional crime in the jurisdiction of the African Court raises the potential difficulty of ‘fit’ with these existing regimes, which will have to be assessed in regard to each crime. The definition of piracy in Article 28F, for example, is drawn almost verbatim from Article 101 of the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.Footnote 27 Some of the originating instruments are AU instruments. The definition of terrorism in Article 28 G subparagraph (A) and (B), for example, is drawn from the definition in Article 1(3) of the OAU Convention on the Prevention and Combatting of Terrorism.Footnote 28 One problem may be that if the definitions of these offences in the Amended Statute differ from those in the suppression conventions, they will pull African states in conflicting directions when it comes to enacting these offences in their domestic law. The African Court should try to avoid this outcome by attempting through its interpretation of provisions to reinforce these prohibition regimes, not undermine them. For example, one element contained in the rubric of the definition of money laundering in the UN’s suppression conventions which is absent from the definition of money laundering in Article 28 I Bis of the Statute of the Court is the requirement that the actions criminalised be done ‘intentionally’. The Court is thus free to impose this subjective test, or apply more stringent tests sometimes followed in national law in some States parties including negligence based money laundering. If it does so it will be increasing the scope of criminalisation, creating a problem of legality if the case originates in a territory of a State which only requires intention. To some extent this reflects the lowest common denominator nature of the provisions in the suppression conventions. It will be important for the Court to conform its position to the law of the territorial State or face challenges.

B. The Source of the Primary Rules

A particular legal problem is that the provision describes certain regulatory crimes but does not provide the standard of legal behaviour from which that criminal behaviour deviates. So, there are legal ways to supply drugs or off-load waste or deal in natural resources and these ways are partly set out in certain international instruments. However, these are promises by States to other States, not international custom. The actual guidance for individual’s on how to regulate their behaviour are set out in the national law of States parties to these instruments. It follows that if an individual is to be prosecuted before the Criminal Chamber for the violation of, for example, the correct way of disposing of waste, regulation of the correct way of disposing of waste will have to have been made in national law of the jurisdiction where it occurs as a pre-condition for that prosecution. If not – there will be no crime. Reliance on a regional instrument to provide the correct way for doing so would be in violation of the principle of legality because those regional instruments may never have been applied in the territory where the disposal was carried out. National legislation will be necessary to provide the yardstick and to be effective it will have to be available in every state. This implies that the AU will have to undertake an exercise in positive complementarity regarding the regulatory standards which these crimes violate.

C. The Necessity of Criminalisation in National Law

Several of the crimes listed in the amended Statute are either not crimes or defined differently in the domestic law of African states. This necessitates an exercise in positive complementarity to ensure the legislative enactment of appropriate offences in African states to enable them to cooperate with the criminal chamber.Footnote 29 Arguably they are required to do so when becoming party because the Protocol creates offences. The jurisdictional expansion at national level over these crimes will also be necessary to ensure fair warning to potential violators and State cooperation with the Court. It seems that this is not entirely what the drafters of the Protocol had in mind, however. In article 28G’s definition of terrorism they include the requirement that the act must violate, in addition to the laws of a ‘State Party’ (to the Protocol one assumes), the law of the AU itself, or a regional economic organisation recognised by the AU, or international law generally. This suggests that one of the goals of the AU’s new jurisdiction is to have a court for the prosecution of these crimes where currently there is none. The notion that terrorism is an international crime, a notion that has been propagated by the Special Tribunal for Lebanon, is highly controversial and rejected by most commentators.Footnote 30 Its status as a regional African crime depends not on the OAU Convention on the Prevention and Combatting of Terrorism,Footnote 31 which simply provides in article 2(1) for an obligation on States Parties to criminalise terrorism in their national law, but on article 28 of the Statute of the Court. Prosecution in the Criminal Chamber that relies on the regional proscription in the absence of a national proscription of the conduct raises fundamental issue of legality and of notice certain to spawn human rights challenges (possibly even within the human rights jurisdiction of the Court itself). Even if the Criminal Chamber is only used for symbolic prosecution of carefully selected cases, it would be unreasonable to assume that individuals that fall into its jurisdiction will know that the Protocol has promulgated certain crimes that apply to them in the Statute of the Court.

D. The Absence of a Gravity Threshold

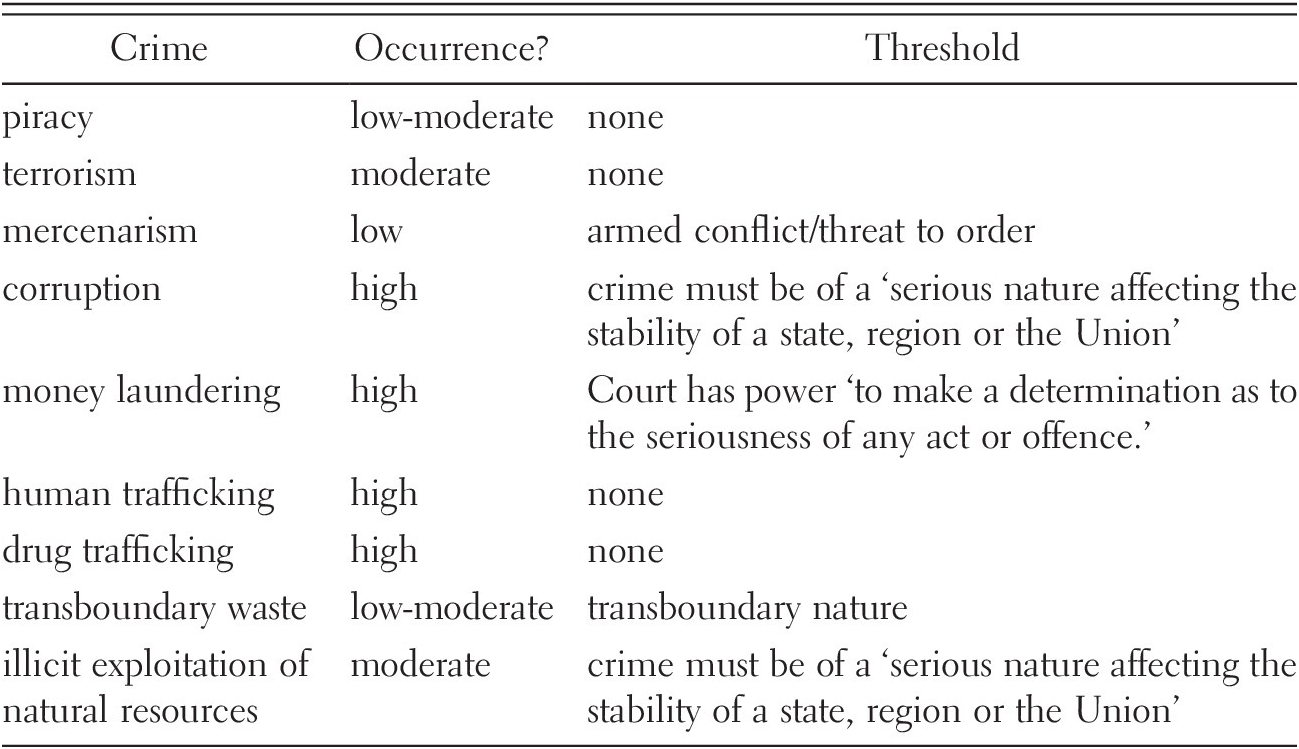

The most significant problem raised by the inclusion of transnational crimes within the Court’s jurisdiction is that no court can hope to cope with prosecution of a large number of cases of these crimes, the vast majority of which are likely to be trivial. This ‘gravity threshold problem’ is really two problems.

First, the Protocol does not indicate at which stage in the procedure this threshold should be set and managed. Perhaps the most appropriate way of applying such threshold criteria would be through prosecutorial discretion (whether cases are taken up by the prosecutor, by authorised AU organs or submitted by AU member states or individuals or NGOS within those states).Footnote 32 The Court also has the power to decide whether a crime is of ‘sufficient gravity’ to justify admissibility under Article 46 H (2)(d), and to exclude it if a crime is not sufficiently grave.

Second, the Protocol does not provide criteria to set this threshold. For a court with a limited capacity there must be further conditions. It is a problem to which the International Law Commission’s scheme for inclusion of the treaty crimes within the jurisdiction of the then proposed ICC was alive, when it recommended that they had to reach a threshold of seriousness in order to fall under the ICC’s jurisdiction.Footnote 33 How serious a breach is enough for the Court to take it up? That has to be tied back to the Court’s goals of fighting impunity and promoting justice and stability. There is little about the definitions of the crimes that is of assistance in establishing such a threshold.

At the moment, the following criteria are being applied:

| Crime | Occurrence? | Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| piracy | low-moderate | none |

| terrorism | moderate | none |

| mercenarism | low | armed conflict/threat to order |

| corruption | high | crime must be of a ‘serious nature affecting the stability of a state, region or the Union’ |

| money laundering | high | Court has power ‘to make a determination as to the seriousness of any act or offence.’ |

| human trafficking | high | none |

| drug trafficking | high | none |

| transboundary waste | low-moderate | transboundary nature |

| illicit exploitation of natural resources | moderate | crime must be of a ‘serious nature affecting the stability of a state, region or the Union’ |

Some of these crimes are morally repugnant (human trafficking), but they are not of equal moral repugnance (drug trafficking). The activities themselves are varied although they can be roughly broken down into activities motivated mainly by corporate or individual monetary gain (piracy, mercenarism, corruption, money laundering, people trafficking, drug trafficking, hazardous waste trafficking, illicit exploitation of natural resources) and by attacks on the State and its constitutional order (terrorism, mercenarism, corruption), although as we can see some crimes fit into both categories. Gravity is not an intrinsic element in the way these offences are defined. The amplificatory elements in the core international crimes – systematic and scope in the definitions of crime against humanity, the presence of an armed conflict in the definition of war crimes, the genocidal intent in genocide – are absent. It has thus been questioned whether the transnational crimes ‘meet the definition of “most serious crimes of concern to the international community” as understood by Article 5(1) of the Rome Statute.’Footnote 34 Although these crimes do cause serious social effects, these negative effects are usually the result of the aggregated social harm of large numbers of individual relatively low impact offences rather than of large scale individual offences. Nor does the nature of the victim assist much. While the core international crimes protect individuals from their own cancerous State and State like entities, transnational crimes protect the State and its citizens from other citizens. Some deal with direct harms to individuals, some with harms of an economic kind, some with harms to the State, some with harms to governance, some with harms to resources, and some with harms to the environment.

Taking only the ‘worst’ cases is desirable because these in penal theory terms have the greatest deterrent and retributive value. A purely empirical comparative measure is probably impossible because the data to make such a relative judgment is simply not available in Africa. There may also be a need in specific cases for the expressive message of fighting impunity to make an example of someone in order to coax the relevant justice system into greater activity. The challenge is to find a suitable general threshold that will enable the court to take into account issues like the socio-economic harm apparently done by the crime, as well as the need for making an exemplary judgment in cases which may not on an absolute scale be among the worst but which are relatively harmful because of, for example, the complete lack of prosecution of such crimes in a State, sub–region or in Africa as a whole. The empirical nature of these offences do, however, suggest a numbers of criteria which loosely applied can serve as criteria for a gravity threshold:

(i) Crimes that ‘pose a threat to the peace, order and security of a region’ for the reasons listed above or for other reasons may be considered for prosecution.Footnote 35 The formula used in some of the crimes in article 28, seems apt: Whether the crime is ‘sufficiently serious to affect the stability of a State, region or the Union’.

(ii) Many of these activities have a higher impact when they involve cross-border activity or effects as they involve the interests of different States, different communities. They involve problems of extraterritoriality that provide a reasonable basis for regional concern, and problems of international cooperation to which the Court’s jurisdiction might provide a practical solution. Following the definition of ‘transnational’ in article 3(2) of the UN Convention against Transnational Organized CrimeFootnote 36 (UNTOC), seriousness would be indicated by activity that (a) is committed in more than one State; (b) is committed in one State but a substantial part of its preparation, planning, direction or control takes place in another State; (c) is committed in one State but involves an organised criminal group that engages in criminal activities in more than one State; or (d) is committed in one State but has substantial effects in another State.

(iii) The commission of many of these offences requires organisation involving cooperation amongst networks of individuals, sometimes in a transnational context. This organisation provides a multiplier effect justifying a regional response. It facilitates the commission of offences otherwise not possible and increases the harmful social or political impact they have because of the impact on scale and scope. Some guidance on the number of individuals involved, the length of time, the nature of their relationship, and their purpose can be obtained from the definition in article 2(a) of the UNTOC of an ‘organised criminal group’ as ‘a structured group of three or more persons, existing for a period of time and acting in concert with the aim of committing one or more serious crimes or offences … in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit’. A ‘structured group’ is further defined in article 2(c) as a ‘group that is not randomly formed for the immediate commission of an offence and that does not need to have formally defined roles for its members, continuity of its membership or a developed structure’. A corporation can be one of the persons involved in such organisation given that Article 46 C provides for corporate criminal liability.

(iv) The definition of serious crime in article 2(b) of the UNTOC as the availability of a maximum punishment of at least four years or more deprivation of liberty at national law in the national jurisdiction where it has occurred may provide some guidance as to what kinds of transnational crime are considered serious but should not be seen as a rigid standard because of the possibility that national law may be unreformed and penalties low for what is regionally considered a serious crime. Moreover, other purely national legal indications of seriousness should if available be taken as a guide.

(v) Serious harm in individual cases may depend on specific considerations like the large volume and value of material involved, the tenure of the activities, their complexity, the size of profits, the potential number of victims and the vulnerability of victims, the presence of violence, corruption or abuse of public office, all of which can lead to higher potential social or political impact. In essence, these elements suggest a quantitative and qualitative assessment from the victim’s perspective.

(vi) Some decisions of the ICC’s interpreting the Rome Statute’sFootnote 37 threshold for seriousness suggest that role and position (high rank) of the alleged offenders is a crucial factor when assessing gravityFootnote 38 and can transform a trivial crime into a serious crime,Footnote 39 while othersFootnote 40 have rejected reliance on the perpetrator’s status. It is submitted that in transnational crimes the identity of the perpetrator is a relevant consideration.

The occurrence of these criteria in regard to a specific crime could be used to assess promotion of that crime into the jurisdiction of the Court as anticipated by article 28 A (2). The presence of all these criteria should not, however, necessarily be required; a nuanced assessment of the case may require only one or a selection to exist before prosecution is justified.

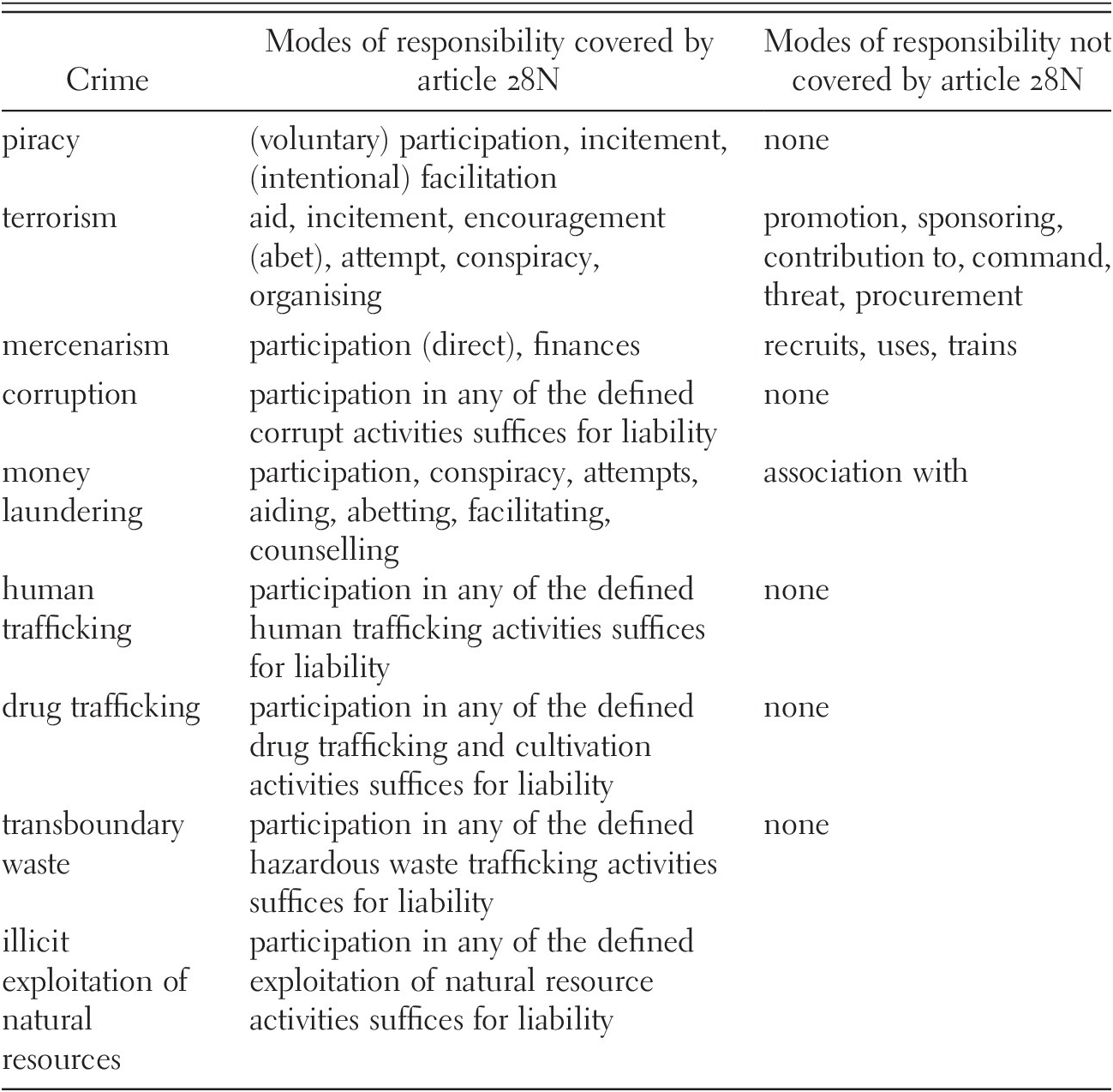

E. Modes of Responsibility

The transnational crime suppression conventions usually provide for modes of responsibility as a perpetrator in the definition of the offence itself and do not single out this mode of responsibility in a specific provision. They do usually, however, provide for details regarding different appropriate forms of secondary responsibility. For example, article 27 of the UN Convention against CorruptionFootnote 41, entitled ‘Participation and Attempt’, provides in paragraph one for criminalisation in national law of ‘participation in any capacity such as an accomplice, assistant or instigator’ of a Convention offence, in paragraph two for the optional criminalisation in domestic law of ‘any attempt to commit a’ Convention offence, and in in paragraph three for the optional criminalisation in national law of ‘the preparation for a’ Convention offence. The Statue of the African Court uses a single consolidated provision, for both core international crimes and transnational crimes, Article 28 N, entitled ‘modes of responsibility’ which provides:

An offence is committed by any person who, in relation to any of the crimes or offences provided for in this Statute:

i. Incites, instigates, organises, directs, facilitates, finances, counsels or participates as a principal, co-principal, agent or accomplice in any of the offences set forth in the present Statute;

ii. Aids or abets the commission of any of the offences set forth in the present Statute;

iii. Is an accessory before or after the fact or in any other manner participates in a collaboration or conspiracy to commit any of the offences set forth in the present Statute;

iv. Attempts to commit any of the offences set forth in the present Statute.

Some of these modes in article 28N such as liability as a co-principal, developed in regard to the core international crimes by the ICC, are unknown in the language of the suppression conventions. Some of these modes such as conspiracy are drawn from the common law and are usually subject to some form of compatibility with basic law provision, if they are included at all, in a suppression convention. In result the Statue of the Court expands the scope of these offences. It may be difficult to reconcile some of the general modes with the specific modes internal to the crimes as defined in the suppression conventions or in Statute of the African Court itself. Article 28N should thus be considered the general provision on modes of responsibility. It covers many of the modes likely to be found in suppression conventions but not all. Taking the example of the UNCAC, it does not cover the specific mode of ‘preparation’. In a case where preparation was a possible charge at the national level but not in the Criminal Chamber, the prosecution cannot put that charge because it does not enjoy that substantive jurisdiction but would have to formulate it as an attempt if possible or abandon it. The same reasoning applies to the criminalisation of modes of responsibility such as ‘sheltering’ a mercenary in the OAU Convention for the Elimination of on Mercenarism in Africa;Footnote 42 its status as an OAU Convention does not expand the jurisdiction of the court because neither the Convention nor the Statute of the Court reveal such an intention, although the specific modes of participation such as ‘sheltering, organising, equipping, promoting, supporting or employing mercenaries’ may assist in the interpretation of broad modes of participation mentioned in article 28N such as ‘facilitation’. Article 28N does cover many of the modes found in the Statute’s definitions of the crimes themselves.

| Crime | Modes of responsibility covered by article 28N | Modes of responsibility not covered by article 28N |

|---|---|---|

| piracy | (voluntary) participation, incitement, (intentional) facilitation | none |

| terrorism | aid, incitement, encouragement (abet), attempt, conspiracy, organising | promotion, sponsoring, contribution to, command, threat, procurement |

| mercenarism | participation (direct), finances | recruits, uses, trains |

| corruption | participation in any of the defined corrupt activities suffices for liability | none |

| money laundering | participation, conspiracy, attempts, aiding, abetting, facilitating, counselling | association with |

| human trafficking | participation in any of the defined human trafficking activities suffices for liability | none |

| drug trafficking | participation in any of the defined drug trafficking and cultivation activities suffices for liability | none |

| transboundary waste | participation in any of the defined hazardous waste trafficking activities suffices for liability | none |

| illicit exploitation of natural resources | participation in any of the defined exploitation of natural resource activities suffices for liability |

Sometimes, however, the mode of responsibility internal to the crime is more specific. Article 28 F criminalises ‘voluntary participation’ and ‘intentional facilitation’ while article 28N speaks only of ‘participation’ and ‘facilitation’. Generally speaking, following the rule lex specialis derogat lex generalis it would not be open to put a charge of, for example, reckless facilitation based on article 28N when article 28F specifically required mens rea in the form of intention. Article 28 N does not cover some modes of responsibility covered in the specific definitions of the crimes. For example, it does not cover the ‘promotion’ of terrorism under article 28GB, an inchoate offence that considerably broadens the scope of criminal liability. However, given the specific mention of this mode in the Statute the lex specialis rule means that that it was the intention of the States parties to expand the subject matter jurisdiction of the Court to include promotion of terrorism. It follows that the prosecutor would be entitled to put a charge of promotion of terrorism and would not be barred from doing so because of the failure to mention this form in the general provision for modes of responsibility in article 28N. The same reasoning applies to all the definitions that provide for specific internal modes of responsibility additional to those in article 28N.

F. Punishment of Transnational Crimes

The suppression conventions are notoriously vague on sentencing, leaving the fixing of penalties to States because it is such a sensitive issue. Where they do make provision, early treaties tend to call for the application of severe penalties, later treaties penalties in proportion to the gravity of offences, while some treaties such as the UN Drug Trafficking Convention, list aggravating factors which suggests a range of penalties from the trivial to severe.Footnote 43 State practice varies widely.

| Crime | Penalty provisions from suppression conventions | Penalty provisions in state practice |

|---|---|---|

| piracy | UNCLOS leaves it to national courts ‘to decide upon the penalties to be imposed’.Footnote 44 | Heavy terms of imprisonment rising to life;Footnote 45 sometimes death.Footnote 46 |

| terrorism | OAU Convention requires punishment ‘by appropriate penalties that take into account the grave nature of such offence’.Footnote 47 | Heavy terms of imprisonment depending on the activity;Footnote 48 sometimes death.Footnote 49 |

| mercenarism | OAU Convention requires punishment as a crime against peaceFootnote 50 and makes the assumption of command an aggravating circumstance.Footnote 51 | Heavy terms of imprisonment have been applied and so has the death penalty.Footnote 52 |

| corruption | OAU Convention gives no guidance as to tariffs. | Practice varies widely with the use of the full range of penalties including fines, forfeiture, and imprisonment up to life.Footnote 53 |

| money laundering | UNCAC requires adequate punishment or punishment that takes into account the gravity of the offence. | Range of penalties for different levels of offences with heavy maximum fines and heavy terms of imprisonment for more serious forms.Footnote 54 Provision for confiscation is usually made. |

| human trafficking | Human Trafficking Protocol makes no provision for penalties; suggests denying or revoking a convicted trafficker’s entry visas.Footnote 55 UNTOC provisions that criminal sanctions should be proportionate to the gravity of the offence and should be taken into account for parole, apply mutatis mutandis. | Range of penalties for different levels of offences are available including fines. Heavy maximum penalties are available when the victims are physically harmed.Footnote 56 |

| drug trafficking | The drug conventions emphasise proportionality although the 1988 Convention emphasises that this should be at the severe end of the scale. | The range of penalties which include imprisonment and finesFootnote 57 varies and frequently extends to heavy punishments including life.Footnote 58 Some AU members apply the death penalty for drug trafficking.Footnote 59 |

| transboundary waste | Bamako Convention does not provide guidance in regard to penalties. | Where national law exists, penalties are low and consist of fines and imprisonment.Footnote 60 |

| illicit exploitation of natural resources | ICGLR 2006 Protocol against the Illegal Exploitation of the Natural Resources provides for imposition of ‘effective and deterrent sanctions commensurate with the offence of illegal exploitation … including imprisonment…’ It also provides for ‘effective and deterrent sanctions and proportionate criminal or non-criminal sanctions including pecuniary sanctions’ against corporate bodies.Footnote 61 | Penalties are low or non-existent; where they do exist, low penalties are often imposed.Footnote 62 |

Under the Statute of the Court, Article 43 A (2) provides that the Court may only impose fines and/or penalties of imprisonment (something important for corporate criminal liability), while Article 43 A (4) provides that the Court should take into account factors such as the gravity of the offence and the individual circumstances of the accused person. The Statute is silent on aggravating factors, which should be developed by the Court itself in a subordinate instrument. It is also silent on post-sentencing procedures like parole and the possibility of prisoner transfer to the State of origin; again, the Court will have to develop these in a subordinate instrument. Under Article 43A (5) ‘the Court may order the forfeiture of any property, proceeds or any asset acquired unlawfully or by criminal conduct, and their return to their rightful owner or to an appropriate Member State.’ This appears to make criminal confiscation (in personam) available to the Court, and implies a power to take preliminary measures to trace, freeze and seize assets. It is not clear whether civil forfeiture (in rem) or value transfer procedures (where the Court makes an estimation of unlawful profit by the accused and confiscates that amount), are available. Article 46J Bis (2) notes that if a State Party is ‘unable to give effect to a forfeiture order it shall take measures to recover the value of the proceeds, property or profits ordered by the Court to be forfeited’, which suggests that value confiscation is available. Under Article 45, restitutionary measures to victims are left to the Rules which will have to consider some of the detailed provisions in this regard in suppression conventions, but Article 45(4) provides expressly that no rights are prejudiced by this provision.

G. Jurisdiction and Immunity to Prosecution for Transnational Crimes

The jurisdiction of the Court is laid down in Article 46 E Bis (2) as follows:

2. The Court may exercise its jurisdiction if one or more of the following conditions apply:

(i) The State on the territory of which the conduct in question occurred or, if the crime was committed on board a vessel or aircraft, the State of registration of that vessel or aircraft.

(ii) The State of which the person accused of the crime is a national.

(iii) When the victim of the crime is a national of that State.

(iv) Extraterritorial acts by non-nationals which threaten a vital interest of that State.

The language is slightly muddled but it appears to mean the Court will have jurisdiction if the crime occurs on the territory of an AU Member State or upon a vessel or aircraft registered with an AU Member State (territoriality and ship and aircraft jurisdiction), or if the accused is a national of an AU Member State (nationality jurisdiction), or if the victim is an AU Member State (passive personality jurisdiction), or if the accused are non-nationals who threaten a vital interest of the State from outside its territory (protective jurisdiction). Establishing territorial jurisdiction is a standard obligation in suppression conventions.Footnote 63 Establishing nationality jurisdiction is almost always a permissive provision in suppression conventions (but commonly extended to habitual residence). Establishing passive personality jurisdiction is limited to anti-terrorism conventions, and again is permissive. The protective jurisdiction may line up with similar but again permissive principles in suppression conventions.

Arguably the African states which have established these different forms of jurisdiction may delegate it to the African Court. It appears, however, that as the African Court enjoys original jurisdiction it will not matter as a strict question of law in the Criminal Chamber if some African states have not adopted these extraterritorial forms of jurisdiction. However, it may lead to arguments based on legality. Moreover, it will become practically problematic if the Court seeks the assistance of the relevant state in the arrest of accused persons and they do not have criminal jurisdiction over those persons. Territoriality is not the issue; it is nationality, passive personality and the protective jurisdiction. Many States do not take these permissive options; to align themselves with the African Court they are going to have to. Article 46 E Bis (2) does not mention the duty generally included in crime suppression conventions to extradite or prosecute, which implies a legal obligation to establish jurisdiction when extradition is not granted. It raises the question of whether an AU Member State on whose territory an alleged transnational criminal is found but refuses to extradite them, will (i) meets its obligations under a suppression convention if it does hand them over to the African Court, and (ii) whether the African Court will lawfully have jurisdiction.

In general, however, the principles enumerated in Article 46 E Bis (2) potentially give it a broad jurisdiction over individuals located in and outside of the AU. Any legal incompatibility of the Court’s jurisdiction with the jurisdiction of AU members will be avoided if they have all enacted the relevant offences and subject them to these jurisdictions. This is what is implied by the provision in Article 46H (1) that the ‘jurisdiction of the Court shall be complementary to that of national courts as well as Regional Economic Communities where specifically provided for by those Communities’. The Court´s jurisdiction cannot complement a State Party´s non-existent jurisdiction over the crime. This view is reinforced in the detail of Article 46H (2), which grounds admissibility on extant investigation or prosecution, decisions not to do so, double jeopardy, and in Article 46H (3), which is about the quality of national proceedings (shielding, delay, lack of independence), and in Article 46H (4), which is concerned with the state of the domestic criminal justice system, all of which imply the State in question has already enacted the same offence with the same jurisdiction. The difficulty will be exercising extraterritorial jurisdiction over individuals in non-African states who are alleged to be responsible for offering bribes, supplying drugs, trafficking humans, dumping waste etcetera in Africa. The foreign State may have a legal relationship with the territorial African State, and the African State may have a relationship with the African Court, but the foreign State will not (yet) have a legal relationship with the African Court.

Immunity to jurisdiction is of obvious relevance to transnational crimes potentially committed by the holders of senior government offices, such as corruption. If immunity is removed for office bearers there is an incentive to retain office.Footnote 64 The new immunity provision in Article 46Ab is provides:

No charges shall be commenced or continued before the Court against any serving AU Head of State or Government, or anybody acting or entitled to act in such capacity, or other senior state officials based on their functions, during their tenure of office.

Under international law immunity ratione personae and immunity ratione materiae shield the prosecution of one State’s officials in another State’s criminal jurisdiction.Footnote 65 Placing the listed transnational crimes in the jurisdiction of what is in effect a regional international criminal court will remove immunity both of a material and personal kind for these crimes.Footnote 66 The usual immunities available for transnational crimes including diplomatic immunity, the immunity of officials from IGOs and the immunity of officials under domestic lawFootnote 67 will be removed because of the change of status of these crimes, although only in Africa. Article 46 A Bis, however, modifies general international law and grants some of what is removed back again by reinstating personal immunity, at least while in office.Footnote 68

H. Procedural Issues

Unlike the system of transnational criminal law, where substantive criminalisation is only a necessary condition for elaborate procedural cooperation by States, the Statute embraces criminalisation in order to establish its jurisdiction. The Statute condenses the complex and pluralistic procedural regimes in the suppression conventions into a few relatively short provisions.

Processing transnational crimes raises a number of specific issues, all of which will require activity by the Court through the adopting of subordinate instruments and the necessity of national legislation. Sub-regional instruments such as those promulgated for purposes of mutual legal assistance by SADEC, ECOWAS, and the Francophonie States may come in useful if some way of utilising them can be worked out. It would be an advantage for the AU to adopt its own mutual legal assistance and extradition instruments, with the role of the Court built into them.

The early phases of investigation of many of these offences will require the use of intelligence led policing techniques, and in particular covert policing activities such as undercover policing and electronic surveillance. At the same time to avoid challenge in the Court it will require the protection of the human rights of those subject to these processes to ensure that evidential material is properly obtained. As the case progresses, stronger legal powers will be required. To respond adequately to a transnational crime like drug trafficking, for example, the pre-trial chamber, trial chamber and appeal chamber envisaged in article 16 will have to be able to exercise all the usual powers to summons drug traffickers, subpoena witnesses, etcetera. Under Article 46 L AU Member States are obliged to cooperate in the provision and the modes of assistance are spelled out. Under Article 46 L (3) the Court is permitted to seek help from non-member states and to conclude agreements to that end. Such agreements will be necessary to ensure effectiveness when the OTP approaches the Pre-Trial Chamber for orders and warrants, for example, under Article 19bis (2), to be applied to individuals outside the AU. Difficult situations will also arise in regard to AU Member States in regard to the Trial Chamber’s power under Article 22(A)(7) to questions suspects, victims and witnesses and collect evidence, engage in inspections in loco, if the particular State loci delicti has not enacted the particular crime because their own law enforcers will not have that power. The Court cannot rely on the provisions in the suppression conventions to compel assistance from non-AU States because it is not party to these conventions (the AU could sign some of them but could only operate as a party if its Constituent Act made it clear it had the competence to do so on behalf of its members as with the various EU treaties). More ambitiously, the AU could consider actually acceding to the UNTOC,Footnote 69 in order to access its procedural cooperation machinery. It would be obliged to declare its level of competence with respect to the matters governed by the Convention when doing so,Footnote 70 but by adopting jurisdiction over these offences in the African Court the AU’s level of competence would be significant. The AU Secretariat could then approach the UNTOC Secretariat, the UNODC, to coordinate activities (and the UNODC is obliged to do so).Footnote 71 It could then approach the UNTOC Conference of Parties, which is charged with promoting and reviewing the Convention and doing so in cooperation with regional organisations,Footnote 72 to work out how best to make the cooperation machinery in the Convention available to the Court (particularly important for the Courts work with non-AU members).

The prosecutors and judges will have to have the skill set of a successful transnational criminal lawyer, and in particular familiarity with the modus operandi used by traffickers and the different law enforcement issues involved. Article 22(5) provides that the prosecutors have to be ‘highly competent in and have extensive practical experience in the conduct of investigations, trial and prosecution of criminal cases.’ Article 22C(4) envisages a Principal Defender with experience in domestic or international criminal law; again, this must extend to transnational crime. Article 3(4) provides that judges must be expert in inter alia ‘international criminal law’. Questions have already been raised about their expertise in international criminal law.Footnote 73 Again, they will also have to be expert in transnational criminal law.

Commentators have raised questions about the funding of this increase in jurisdiction.Footnote 74 The ambitious jurisdictional reach has the potential to dilute the funds made availableFootnote 75 so that prosecutions of crimes that are arguably more important such as genocide or crimes against humanity will be underfunded. And then there is the cost of incarceration. Some funding may come from shares of asset forfeiture. Another way of funding the court’s expansive jurisdiction over transnational crimes would be to franchise that jurisdiction. In this model a particular member state of the AU could, if it felt it necessary to transfer prosecution of, for example, a corruption case, out of its territory into the Court to avoid domestic pressure on the Court, be asked to pay for that prosecution and all punishment costs. To take this idea even further, it might be possible to make provision for subsidised sponsorship of the particular trial by foreign donors where they felt it was generally in their interest, and extradition was not forthcoming.

5. Conclusion

The Statute of AU Court as supplemented by the Malabo Protocol has created a stand-alone regional transnational criminal court. It has a path-breaking jurisdiction over a number of transnational crimes that were formerly only the subject of treaty obligations on States parties under various crime suppression conventions to establish national criminal offences. This novel jurisdiction presents an opportunity for the region to address impunity for these offences. The two challenges the Court faces are both surmountable: to establish a high threshold for admissibility of cases so that only the most serious are addressed by the Court; and to establish a workable system for the policing and prosecution of these offences involving cooperation with States both within and without Africa. If these challenges can be met, the Court will be in a position to make an entirely unique contribution to the suppression of these selected transnational crimes within the region, and to develop a model which other regions which face similar threats might follow.