Advancing Women's Health Through Medical Education

Advancing Women's Health Through Medical Education Book contents

- Advancing Women’s Health Through Medical Education

- Reviews

- Advancing Women’s Health Through Medical Education

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Section I Abortion Training: Workforce, Leadership, Social & Political Impact

- Section II Integration of Abortion into Graduate Medical Education

- Section III Family Planning Curricular Design & Implementation

- Section IV Reproductive Health Services & Abortion Training: Global Examples

- Index

- References

Section III - Family Planning Curricular Design & Implementation

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 30 July 2021

- Advancing Women’s Health Through Medical Education

- Reviews

- Advancing Women’s Health Through Medical Education

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Section I Abortion Training: Workforce, Leadership, Social & Political Impact

- Section II Integration of Abortion into Graduate Medical Education

- Section III Family Planning Curricular Design & Implementation

- Section IV Reproductive Health Services & Abortion Training: Global Examples

- Index

- References

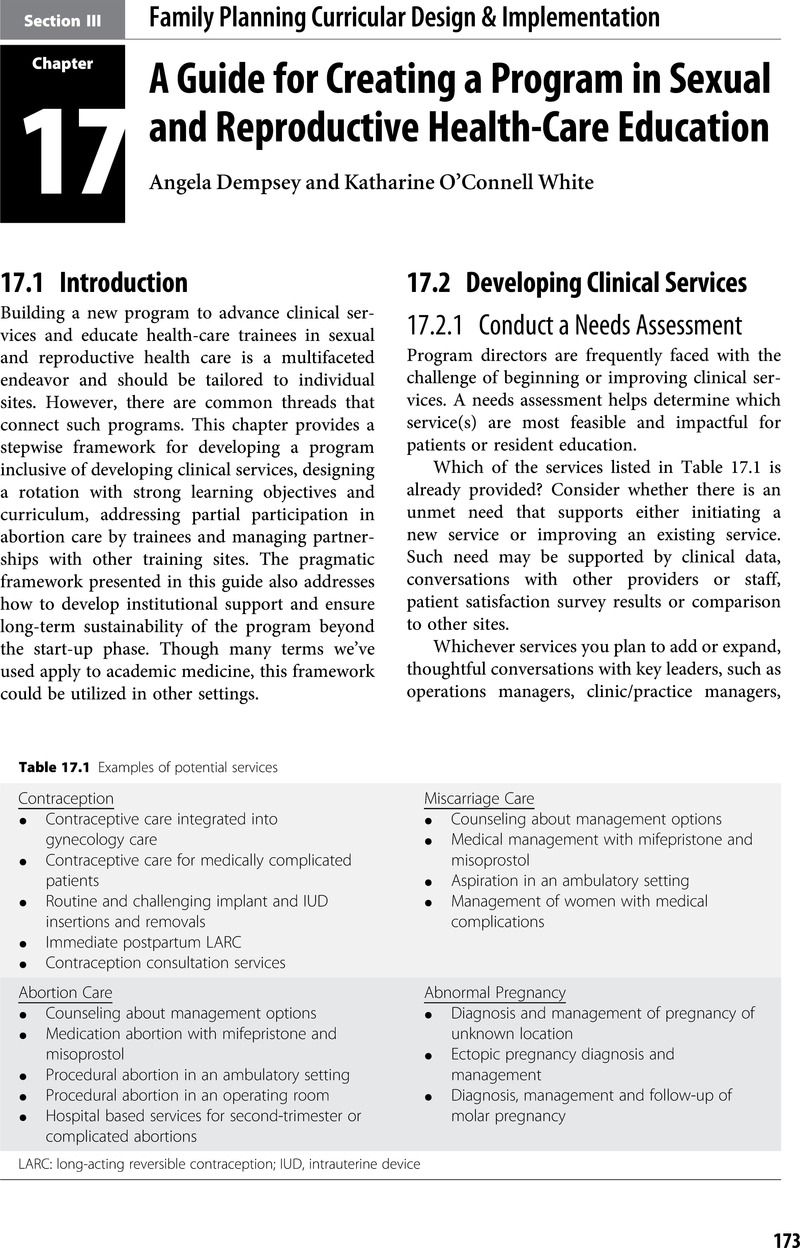

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Advancing Women's Health Through Medical EducationA Systems Approach in Family Planning and Abortion, pp. 173 - 262Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2021