Towards the end of her reign, Catherine the Great, observing that Jews were filling the ranks of the nascent Russian middle class, banished the Russian Jews to the Pale of Settlement. The Pale, established in 1791, corresponded to the borders of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, which had been forcibly annexed by Imperial Russia. It included much of present-day Lithuania, Belarus, Poland, the Ukraine and parts of western Russia. More than 90% of the Russian Jews were deported to the Pale. Even within the Pale, Jews were discriminated against; they paid double taxes and were forbidden to own land, run taverns or receive higher education. Moreover, all young men were forcibly conscripted into the Imperial Russian Army for 25 years. Despite these heavy burdens, the Jewish population in Russia grew from 1.6 million in 1820 to 5.6 million in 1910.

Thousands of Jews fell victim to pogroms in the 1870s and 1880s. This led to mass emigration, particularly to the United States (two million between 1880 and 1914), as well as to other developments, such as the spread of the Haskalah (Jewish enlightenment). Zionism also took hold in the Pale. Only after the overthrow of the Czarist regime in 1917 was the Pale of Settlement abolished. Even after the Revolution, the relationship of the Jewish communities with the local governments remained strained and emigration continued.

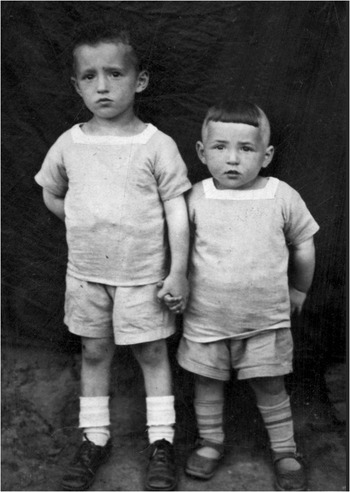

The Pale was large and by no means culturally homogeneous. There were local laws and customs. Moreover, the Jewish population used its ingenuity to circumvent the harsh regulations. Thus in the Lithuanian North, renowned for its sober view of life, in a shtetl called Zelva, Aaron’s grandfather Benjamin Klug owned quite a large farm. The Klugs may have immigrated into Lithuania from Alsace. Benjamin was a cattle dealer, buying cattle from local farmers, fattening them up and herding them to market in the local town Ukmerge, some 20 miles away. He was helped by his three sons Yudel, Lazar (who was of unusually short stature, on account of having contracted typhus during his adolescence) and Isaac. Essentially drovers, they were accomplished horsemen. Lazar married Bella (née Silin; the Silins ran the local shop), and they had two sons, Benjamin (1924) and Aaron (11th August 1926). Lazar had a traditional Jewish education and secular schooling. The family language was Yiddish, but Lazar was also fluent in Russian and Lithuanian. Although he never had the opportunity to acquire a higher education, Lazar had a natural gift for writing, and he published a number of articles in the newspapers of Kaunas in Lithuania, for which he acted as a freelance correspondent.

As the second son, Lazar would not inherit his father’s farm. Furthermore, he had had some very unpleasant experiences with the Bolshevik army: in defence of his brother, it is said that he killed a Bolshevik soldier and was very lucky to have survived the ensuing fracas (alternative accounts also circulate in the familyFootnote 1). Members of the Gevisser family, who were cousins of Bella, had emigrated to Durban in South Africa around 1900. Durban welcomed white immigrants, which included a trickle of Jewish families. About 90% of South Africa’s Jews came from Lithuania. Given all these factors, in 1927 Lazar decided it was time to seek a new home. He emigrated to Durban where he was accommodated by the Gevisser family. He had been apprenticed as a saddler and therefore knew about leather, and thus he entered the family business of Moshal-Gevisser dealing in hides and general stores. Bella, with her two sons Benjamin and Aaron and her sister Rose, followed to Durban in 1929. Isaac also emigrated to South Africa and settled in Johannesburg.

On the death of his father, Yudel became a landowner. However, as a consequence of the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact, in June 1940 Soviet military forces occupied Lithuania and set up a puppet government consisting mainly of left-wing poets, which made itself popular among the general public by nationalising the land. The landowners were summarily deported. Thus poor Yudel was shipped off to Siberia, where he died in exile. The death was only reported to the family after the Second World War through a charitable organisation that investigated the fate of deportees. His son was conscripted into the Russian army and died fighting the Germans. Yudel’s youngest daughter Janina spent the war with the partisans in the forest and then married and emigrated to Israel. Years later, she complained to Lazar that he had taken the easy way out. To Lazar this complaint seemed to be rather misplaced. After all, he had received no inheritance and had to fend for himself.

In January 1834, Sir Benjamin d’Urban had taken office as governor and commander in chief of the South African Cape Colony. He occupied Natal and named it as a new colony for the British Empire. To commemorate this, the name of the principal port was changed from Port Natal to Durban. Durban was a very English microcosm of the Empire – Civis Britannicus sum. Facing the Indian Ocean at latitude 30° S, Durban has a subtropical climate varying between warm in winter and hot and humid in summer. In 1927 it was a relatively sleepy town. Mixed-race people and Indians ran the market gardens situated in the hills above the city, and Zulus provided domestic help. On Sundays the Zulus would dance on the beach. For the whites, life was pleasant enough. Moreover, for the Klug boys there were lots of things to do – there was the beach and the bush full of gum trees, poisonous snakes, and troops of chattering vervet monkeys, all accessible on a bicycleFootnote 2.

The Klugs moved between houses in the Glenwood area, which lies above the town on the ridge known as Berea, then near the edge of the town. They lived a modest middle-class life with two Zulu domestics. The sound of singing emanated from the Zulu labourers building new roads all around their house. The young Klug brothers enjoyed their environment, which included the neighbouring Greyville Racecourse. They would crawl though the hedge to watch the races. Benjamin (Bennie), endowed with the excellent memory that was a characteristic of both brothers, soon knew the names of all the horses and the winners of the Durban July Handicap for the past few years. A cycle ride away across the town, next to the beach, was the Jewish Club where Lazar liked to play chess.

Figure 1.1 Bennie and Aaron

Figure 1.2 Aaron, Bennie and their mother Bella

The annual visits of the Royal Navy South East Asia Squadron, fully beflagged, to Durban Harbour under the command of ‘Evans of the Broke’ (Admiral Lord Mountevans) were big days for the colony and interesting for the Klug schoolboys. The 25th Jubilee of George V was celebrated by a procession representing the diverse peoples of this great Commonwealth. In spite of the heat, poor Bennie went as a Newfoundland fisherman complete with heavy oilskins!

When Aaron was three and a half, Bella made an unusual discovery. In spite of the family switching from Yiddish to English when Aaron was two, he was now reading the English newspaper. What was to be done with such a precocious child? It was decided he should attend the local Penzance Road Primary School together with Bennie, who was nearly two years older. For Aaron, this had its positive and negative sides: Aaron was easily able to keep up with the curriculum, but because he was much younger and smaller than his classmates, he needed Bennie to protect him from bullies. Moreover, Penzance school was right on the edge of the bush, and frequently the Klug brothers had to defend their lunch bags from invading hoards of vervet monkeys.

In 1932, family tragedy intervened: Bella died in hospital of pneumonia following a minor operation. The trauma was somewhat ameliorated by the presence of Aunt Rose, who became Aaron and Bennie’s surrogate mother. Later, Lazar married Rose and they had two children, Phillip and Ethel, who changed her name to Robin. Bennie, Aaron and Robin were bright, independent and socially competent, as Rose expected children to be. Phillip was different. He needed a lot of help even to keep abreast of day-to-day problems. His condition would nowadays probably be described as mildly autistic. Both Bennie and Aaron were very attached to Phillip and later gave him a lot of support. As an adult, Phillip left the family home in Durban to live with Aaron in Cambridge, England. This turned out to be too stressful, and Phillip finally moved in with Bennie in Johannesburg where he died in his 40s of a lung infection. Robin became a pharmacist and now lives in Israel.

Aaron early developed an interest in cinema, particularly Westerns. Their intrinsic morality, the predictable triumph of good over evil, appealed to him. Moreover, just across the town Durban offered its own speciality – Indian Cinema – in which the fat rich boy falls for the poor thin girl. This stereotyped art form also intrigued young Aaron.

At the age of eleven, Aaron transferred to the reputable Durban High School for Boys. He could have gone to the Glenwood Secondary School, but they did not teach Latin, and Latin was essential to get into medical school. Aaron was, again, the smallest and youngest member of the school. While Bennie was still able to offer protection from bullying, Aaron sometimes had to win freedom of action by helping his older but less talented school friends with their homework. He was always a good teacher.

Durban High School for Boys was established in 1866, modelled on an English public school. There were six houses, including one for boarders. Cricket culture percolated the school. Situated on the ridge of the Berea, the school had a slightly less oppressive climate than the town; nevertheless, in summer it was still hot. With scant regard for the pupils’ comfort, school uniform (for the junior school) was short wool trousers, knee-high wool socks, a white shirt and a navy-blue woollen blazer. At temperatures in excess of 85 °F (30 °C) one was permitted to remove one’s blazer. Aaron entered this microcosm of Englishness at eleven and stayed until he was fifteen. It had an enduring influence. Together with Bennie and Ralph Hirschowitz, who became his life-long friend, Aaron generally enjoyed his four years at the High School. The order in class settled into a pattern: Aaron at the top of the class, followed by Bennie and Ralph.

The ethos of the school, based on Rudyard Kipling, was to ignore those two imposters triumph and disaster. One did not make a fuss about things. Aaron had absolutely no difficulty in adopting this reserve and avoidance of overt emotionalism since it was germane to his own personality.

According to Aaron, the underlying philosophy of the school was quite simple – the bright boys specialised in Latin, the not so bright in science and the rest studied subjects such as geography and history. Aaron did Latin; Greek had been dropped to accommodate Afrikaans.

Bennie was a good athlete, renowned for his prowess at long jump. Furthermore, he was a cricketer, an opening bat for the house eleven and left-handed: a left-handed batsman is useful for confusing the opposing bowlers. Very much to the regret of the Klug brothers, their father Lazar would not allow them to play games on the Sabbath, which cramped Bennie’s style and prevented him from progressing to the school first eleven.

By today’s standards, the school offered few challenges other than Advanced Latin Prose Composition in the Sixth Form. Aaron was very good at Latin, which he positively enjoyed. On account of an optic atrophy in his right eye that affected his peripheral vision, the result of an accidental injury sustained as an infant, Aaron was excused some sports and spent much of his time reading books. The school library was very good but was kept locked; those who applied for the key were ‘swots’, which attracted disapprobation in a school devoted to cricket. Fortunately, there was also a good public library in Durban, which the Klug brothers used to visit after the required attendance at the synagogue on Saturday mornings. Aaron was a very fast reader and was equipped with a phenomenal memory. He was also endowed with unbridled curiosity, more so than his older brother. After studying Leopold von Ranke’s treatise on the machinations of the renaissance Popes, Aaron developed a particular fascination for the Roman pontiffs. Furthermore, from his knowledge of the Hebrew alphabet, which is based on the Phoenician alphabet with roots in Egyptian characters, Aaron became interested in hieroglyphics. He was fast becoming a polymath.

Two teachers in the school, Charlie Evans in History and Neville Nuttall in English, made a memorable impact. Under Nuttall’s tutelage Aaron developed a lively and sustained interest in English literature and poetry. Evans pointed out that tensions over the ‘Polish Corridor’ – the narrow strip of land connecting Poland to the Baltic Sea, and dividing East Prussia from the main body of the German Reich – could potentially cost some of the students their lives. Indeed, a few months later it led to the outbreak of the Second World War. Finally, Aaron began to take an interest in science. In particular, Paul de Kruif’s Microbe Hunters, which has been an inspiration for many aspiring physicians and scientists, had a lasting influence. This book determined Aaron’s schoolboy life plan, namely the study of microbiology.

On leaving school, Aaron and Bennie split up. Aaron went to Johannesburg; Bennie stayed in Durban and went to the Natal University to study engineering. Later, Bennie was to work for the structural consulting engineers Arup Associates in Johannesburg, Israel and London. For some time, Bennie was the quiz champion on South Africa Radio – until he was requested to resign, to give others a chance.

In 1941, at the age of 15, armed with a scholarship that paid for tuition but nothing else, Aaron entered medical school at Witwatersrand University in Johannesburg. He was not intending to become a medic, but this was apparently the only way into microbiology. Uncle Isaac (Itzic) could offer a pied-à-terre. He lived in Booysens, an industrial suburb to the south of Johannesburg where there were big mine dumps. This was far from a convenient arrangement, since Isaac’s home and the University were 8 km and two tram-rides apart. Aaron was still very young, and he palled up with his younger cousin Bommie (Benjamin) to run up and down the mine dumps for fun. Later, they tried out a local boxing club, but interest quickly flagged.

The poetically named University of Witwatersrand (‘ridge of white waters’), prosaically known as Wits, lies to the northwest of the centre of Johannesburg on the ridge after which it is named. This ridge, which runs east–west through Johannesburg, extends over a hundred miles. It is remarkable for having yielded nearly half of all the gold ever mined in the world. To the northeast, separated by a mile from the main campus, lies the Parktown Campus, the site of the Medical School and the Department of Anatomy. Between the two campuses, on the brow of the hill, there was a fort then used as a prison.

For his first year Aaron elected to do the preliminary course for medicine, the prima (similar to British A levels): botany, zoology, chemistry and physics. The second year was in the medical school and consisted of physiology, biochemistry (then still called physiological chemistry) and anatomy. Aaron was accompanied in this venture by his school friend Ralph Hirschowitz, who also wished to study medicine. Another student studying medicine at this time was Sydney Brenner, who would later be a colleague of Aaron’s in Cambridge.

The commanding personality in the Anatomy School was Raymond A. Dart, a native of Queensland, Australia, who in 1922 was made head of the newly established Department of Anatomy. In 1924, a limestone quarry owner at Taung in northwestern South Africa shipped Dart a box of rock in which Dart discovered a fossil skull of a child. This, he declared, was an example of Australopithecus africanus (a missing link between humans and apes). Dart lectured in physical anthropology, giving demonstrations of how reptiles walked and how the articulation of the limbs differed from that of mammals. One of the highlights of Dart’s lectures was his proudly producing the Taung child fossil skull. Another strong influence in the Anatomy School was Lawrence Herbert Wells, who was single-minded about dissecting cadavers. In spite of Dart’s skull, after some months of dissection Aaron found the going tedious and shifted his focus back to the physics and chemistry schools on the main campus.

Chemistry and biochemistry seemed to offer more hope of understanding microbiology than dissecting cadavers. Moreover, as a result of a public lecture on modern physics Aaron discovered the Schrödinger wave equation, which opened new vistas for him. During this time Aaron added a new dimension to his life, namely mathematics. He discovered that he had an innate ease with mathematical formalism. Mathematics allowed him to appreciate the intellectual elegance of the Schrödinger wave equation and quantum mechanics. He also became fascinated by functions of a complex variable. However, although he turned out to be very competent in this area he never saw mathematics as an end in itself but rather as a means to an end: he was never a pure mathematician. For the next three years, after savouring many disciplines, Aaron devised his own course of study in physics, chemistry and mathematics, treating the University as a kind of intellectual supermarket. He graduated in science with three majors rather than the normal two. Fortunately, the Dean, Dr Van der Horst, arranged for Aaron to get exemption from University regulations when necessary. The Dean was understanding of Aaron’s apparent dilettantism, especially since Aaron finished with firsts in all three subjects.

Aaron was still an enthusiastic cinemagoer. A movie was then called ‘a bioscope’ to be seen at a ‘Café Bio’. The Café Bios ran continuously. Moreover, one got a cup of coffee or an ice cream with the tickets, which were quite cheap. Aaron went most days and became something of an expert in Westerns. He maintained this interest: later during his time in Cambridge, he was known to slip off to the Arts Cinema for a choice Western.

Since it was wartime, Aaron perforce joined the Officer Training Corps. In fact, if the war had continued, at the end of his studies he would have been enlisted. For six weeks in the summer and then two weeks at Easter they went to camps. Since he was far younger than most, Aaron was never required to do very much. This was not really Aaron’s métier. In contrast, one of the profound influences on Aaron at this time was the Hashomer HatzairFootnote 3, which Ralph Hirschowitz urged Aaron to join. The Hashomer Hatzair was a romantically idealistic Zionist youth movement that resulted from the merger of the Hashomer (‘The Guard’) and Ze’irei Zion (‘The Youth of Zion’). While in Durban, Ralph and Aaron had been members of the Habonim, a Jewish scouting movement based on the German Wandervogel and Baden Powell’s scouts. However, the Hashomer Hatzair offered an ideological and cultural depth that the Habonim, a mass movement, was not able to provide. Believing in the equality of man, in Marxism, and in Zionism, the movement was also influenced by the German Wandervogel movement and by the ideas of Ber Borochov, the father of socialist Zionism. Labour Zionists believed that a Jewish state could only come about by the Jewish working class settling in Palestine and constructing a state through the creation of a progressive Jewish society with rural kibbutzim and an urban Jewish proletariat. The Wandervogel movement sought to liberate and educate youth by returning to Nature whereas Hashomer Hatzair thought that the liberation of Jewish youth could be accomplished by living in kibbutzim, which was perhaps not very different. They addressed each other as ‘shomrim’ in the sense of ‘comrades’Footnote 4. The Hashomer Hatzair, which is secular, organises activities and machanot (camps), which are used to educate and also to propagate the aims of the movement. In the Palestinian Mandate the movement also formed a political party, which true to its socialist convictions advocated a bi-national Palestine with equality between the Arab and Jewish workers – united by their class struggle. By 1939 Hashomer Hatzair had 70,000 members worldwide, the majority in Eastern Europe. During World War II and the Holocaust, thousands of members of Hashomer Hatzair died resisting the Nazis. Together with the Habonim they played a major role in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in 1943. The local groups of the Hashomer Hatzair actively supported immigration into Palestine, both legal and illegal, to the kibbutzim to which they were attached. This act of ‘Aliyah’ or ‘ascent’ was of central importance to the movement. The rules of Hashomer Hatzair required that a person acquiring majority should fulfil the goal of self-realisation by going to live on a kibbutz.

However, in South Africa in the 1940s there were also other political forces at play, in particular those supporting Trotskyism and world revolution. Here Zionism played a secondary role. Members of the Hashomer Hatzair were also anti-apartheid, which led later to the enforced closure of the South African branch. One of the important figures was Baruch Hirson, later a friend of Aaron’s, who turned from Zionism to working with the African National Congress. For his apparent association with a terrorist outrage Hirson later served a devastating 9½ year prison sentence. His departure from the Johannesburg Ken (literally ‘nest’) of the Hashomer Hatzair coincided with the emigration to Palestine of a number of influential leaders, which led to a power vacuum in Johannesburg. At this moment, Aaron and Ralph appeared on the scene. Ralph, good-looking and charismatic, was a natural leader and he and Aaron created a strongly academic and influential group within the Johannesburg Ken. By attempting to fuse radical Marxism with psychoanalysis Ralph was led to the works of Wilhelm Reich, who soon became a dominant influence both in Johannesburg and Cape Town. The Vanguard bookshop in President Street carried much of the left-wing literature and the works of Wilhelm Reich. These were sought out and avidly read by the student members of the Hashomer Hatzair. According to Reich, life’s difficulties and neuroses are the result of a patriarchal authoritarian education with its sexual suppression. Fulfilment could be obtained via the release of frustrated sexual energy: a ‘Sexual Revolution’ rather than a proletariat revolution. Lively discussions of ‘Orgone Energy’ (freedom through orgasm) and the understanding of ‘Character Armour’ quickly usurped the striving for fulfilment through ‘Aliyah’ and ‘Kibbutz’. The contrast between Reich’s invitation to sensual behaviour and the strictly puritanical rules of the Hashomer Hatzair often led to discussions in which Aaron poked fun at Reich’s theories. Furthermore, communism did not interest these young academics: for their situation it just seemed irrelevant.

Besides providing Aaron with a forum for youthful utopian discussions and a network of friends whose various abodes turned out to be useful alternatives to the nightly trek back to uncle Isaac, these heady days with the Johannesburg Hashomer Hatzair were to have a profound influence on Aaron’s life. Amongst other things, they led to his meeting with members of the Cape Town Ken, including Vivian Rakoff, who was to become a life-long friend. Vivian Rakoff attended a machaneh (summer camp) in 1944 at Magaliesburg, a holiday venue near Johannesburg renowned for its bucolic beauty. He recounts that an afternoon walk with Aaron and Ralph was worth a year at university. In 1945, the Johannesburg Ken set up a large machaneh in an idyllic venue near Newcastle in the Drakensberg, the line of mountains that marks the border of Natal. This camp lasted six weeks – long enough to build a symbolic watchtower. However, everything one needed (including lime for the latrines, which became Aaron’s special responsibility) had to be carried in. It turned out that the camp had been pitched with insufficient regard for the logistic needs of nearly 200 young people over an extended period. Stress included an outbreak of scarlet fever. Somewhat in desperation at the shortage of supplies, Aaron approached the local farmer and purchased some sheep – on the hoof. Confronted with the necessity of turning these furry behemoths into lamb chops, Aaron sought out a sharp knife. Luckily, a local Zulu farmhand intervened, saying: “This is no work for you, baas-sir.” This incident illustrates one of Aaron’s endearing qualities: the ability to get someone else to take over onerous practical work by indicating a hesitancy that might be construed as lack of competence.

South Africa is vast, but travel was cheap. The whites were a natural aristocracy with an informality arising from an innate self-confidence. So long as you were not rabidly anti-apartheid, everyone was your friend. Travel for students was cheap since it mostly involved hitchhiking or riding in the brake vans of goods trains. Thus young people from Cape Town, some 1500 km away, turned up at the camp in the Drakensberg, among them Liebe Bobrow. Ralph, who had previously visited Cape Town on a fact-finding mission on behalf of the Johannesburg Ken, introduced Aaron to Liebe. With his sober Lithuanian family and colonial English public school education, Aaron contrasted starkly with Liebe, a vivacious sixteen-year-old direct out of school, who came from a very different culture. Her father, Alexander Bobrow, was an analytical chemist, a scholar, and very left wing; Liebe was a musician and a dancer. Moreover, Cape Town is not Durban. During this camp they merely became acquainted. However, the following year the Johannesburg Ken of Hashomer Hatzair decreed that Aaron should go to Cape Town.