26 results

Conclusion

-

- Book:

- The Socialism of Fools?

- Published online:

- 05 July 2015

- Print publication:

- 23 July 2015, pp 187-198

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- The Socialism of Fools?

- Published online:

- 05 July 2015

- Print publication:

- 23 July 2015, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - France

-

- Book:

- The Socialism of Fools?

- Published online:

- 05 July 2015

- Print publication:

- 23 July 2015, pp 24-82

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- The Socialism of Fools?

- Published online:

- 05 July 2015

- Print publication:

- 23 July 2015, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- The Socialism of Fools?

- Published online:

- 05 July 2015

- Print publication:

- 23 July 2015, pp 1-8

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Great Britain

-

- Book:

- The Socialism of Fools?

- Published online:

- 05 July 2015

- Print publication:

- 23 July 2015, pp 138-186

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - Germany

-

- Book:

- The Socialism of Fools?

- Published online:

- 05 July 2015

- Print publication:

- 23 July 2015, pp 83-137

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- The Socialism of Fools?

- Published online:

- 05 July 2015

- Print publication:

- 23 July 2015, pp 209-211

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- The Socialism of Fools?

- Published online:

- 05 July 2015

- Print publication:

- 23 July 2015, pp 199-208

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Before the Left: The Anti-Semitic Thought of the European Enlightenment

-

- Book:

- The Socialism of Fools?

- Published online:

- 05 July 2015

- Print publication:

- 23 July 2015, pp 9-23

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgements

-

- Book:

- The Socialism of Fools?

- Published online:

- 05 July 2015

- Print publication:

- 23 July 2015, pp vii-viii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

The Socialism of Fools?

- Leftist Origins of Modern Anti-Semitism

-

- Published online:

- 05 July 2015

- Print publication:

- 23 July 2015

Frontmatter

-

- Book:

- Roots of Hate

- Published online:

- 28 June 2009

- Print publication:

- 13 October 2003, pp i-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter Four - The Economic Root

-

- Book:

- Roots of Hate

- Published online:

- 28 June 2009

- Print publication:

- 13 October 2003, pp 177-264

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Roots of Hate

- Published online:

- 28 June 2009

- Print publication:

- 13 October 2003, pp vii-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

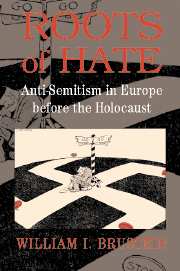

Roots of Hate

- Anti-Semitism in Europe before the Holocaust

-

- Published online:

- 28 June 2009

- Print publication:

- 13 October 2003

Index

-

- Book:

- Roots of Hate

- Published online:

- 28 June 2009

- Print publication:

- 13 October 2003, pp 377-384

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

List of Figures and Tables

-

- Book:

- Roots of Hate

- Published online:

- 28 June 2009

- Print publication:

- 13 October 2003, pp viii-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter Five - The Political Root

-

- Book:

- Roots of Hate

- Published online:

- 28 June 2009

- Print publication:

- 13 October 2003, pp 265-336

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter Three - The Racial Root

-

- Book:

- Roots of Hate

- Published online:

- 28 June 2009

- Print publication:

- 13 October 2003, pp 95-176

-

- Chapter

- Export citation