19 results

Abbreviations

-

- Book:

- Jewish Internationalism and Human Rights after the Holocaust

- Published online:

- 05 November 2020

- Print publication:

- 26 November 2020, pp xi-xi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- Jewish Internationalism and Human Rights after the Holocaust

- Published online:

- 05 November 2020

- Print publication:

- 26 November 2020, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Conclusion

-

- Book:

- Jewish Internationalism and Human Rights after the Holocaust

- Published online:

- 05 November 2020

- Print publication:

- 26 November 2020, pp 186-193

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - From Antisemitism to “Zionism Is Racism”

-

- Book:

- Jewish Internationalism and Human Rights after the Holocaust

- Published online:

- 05 November 2020

- Print publication:

- 26 November 2020, pp 112-137

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - The Inadequacy of Madison Avenue Methods

-

- Book:

- Jewish Internationalism and Human Rights after the Holocaust

- Published online:

- 05 November 2020

- Print publication:

- 26 November 2020, pp 138-163

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - “Good Words Have Become the Servants of Evil Masters”

-

- Book:

- Jewish Internationalism and Human Rights after the Holocaust

- Published online:

- 05 November 2020

- Print publication:

- 26 November 2020, pp 164-185

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Jewish Internationalism and Human Rights after the Holocaust

- Published online:

- 05 November 2020

- Print publication:

- 26 November 2020, pp vii-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Who Will Tame the Will to Defy Humanity?

-

- Book:

- Jewish Internationalism and Human Rights after the Holocaust

- Published online:

- 05 November 2020

- Print publication:

- 26 November 2020, pp 39-63

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - “Individual Rights Were Not Enough for True Freedom”

-

- Book:

- Jewish Internationalism and Human Rights after the Holocaust

- Published online:

- 05 November 2020

- Print publication:

- 26 November 2020, pp 19-38

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Exit from North Africa

-

- Book:

- Jewish Internationalism and Human Rights after the Holocaust

- Published online:

- 05 November 2020

- Print publication:

- 26 November 2020, pp 86-111

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- Jewish Internationalism and Human Rights after the Holocaust

- Published online:

- 05 November 2020

- Print publication:

- 26 November 2020, pp 1-18

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - The Consequences of 1948

-

- Book:

- Jewish Internationalism and Human Rights after the Holocaust

- Published online:

- 05 November 2020

- Print publication:

- 26 November 2020, pp 64-85

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Notes

-

- Book:

- Jewish Internationalism and Human Rights after the Holocaust

- Published online:

- 05 November 2020

- Print publication:

- 26 November 2020, pp 194-254

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgments

-

- Book:

- Jewish Internationalism and Human Rights after the Holocaust

- Published online:

- 05 November 2020

- Print publication:

- 26 November 2020, pp viii-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- Jewish Internationalism and Human Rights after the Holocaust

- Published online:

- 05 November 2020

- Print publication:

- 26 November 2020, pp 255-281

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Jewish Internationalism and Human Rights after the Holocaust

- Published online:

- 05 November 2020

- Print publication:

- 26 November 2020, pp 282-298

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- Jewish Internationalism and Human Rights after the Holocaust

- Published online:

- 05 November 2020

- Print publication:

- 26 November 2020, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dramatis Personae

-

- Book:

- Jewish Internationalism and Human Rights after the Holocaust

- Published online:

- 05 November 2020

- Print publication:

- 26 November 2020, pp xii-xiv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

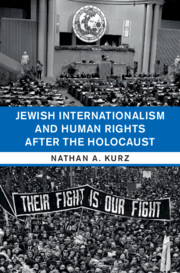

Jewish Internationalism and Human Rights after the Holocaust

-

- Published online:

- 05 November 2020

- Print publication:

- 26 November 2020