373 results

Assessment centers: Reflections, developments, and empirical insights

-

- Journal:

- Industrial and Organizational Psychology / Volume 17 / Issue 2 / June 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 06 May 2024, pp. 149-153

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Affinities between Asian non-human Schistosoma species, the S. indicum group, and the African human schistosomes

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Helminthology / Volume 76 / Issue 1 / March 2002

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 12 April 2024, pp. 7-19

-

- Article

- Export citation

Molecular phylogeographic studies on Paragonimus westermani in Asia

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Helminthology / Volume 74 / Issue 4 / December 2000

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 12 April 2024, pp. 315-322

-

- Article

- Export citation

A molecular perspective on the genera Paragonimus Braun, Euparagonimus Chen and Pagumogonimus Chen

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Helminthology / Volume 73 / Issue 4 / April 1999

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 April 2024, pp. 295-299

-

- Article

- Export citation

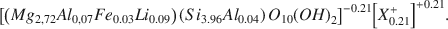

Mixed-Layer Kerolite/Stevensite from the Amargosa Desert, Nevada

-

- Journal:

- Clays and Clay Minerals / Volume 30 / Issue 5 / October 1982

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 02 April 2024, pp. 321-326

-

- Article

- Export citation

Origin of Magnesium Clays from the Amargosa Desert, Nevada

-

- Journal:

- Clays and Clay Minerals / Volume 30 / Issue 5 / October 1982

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 02 April 2024, pp. 327-336

-

- Article

- Export citation

Figures

-

- Book:

- Monopsony in Labor Markets

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp xi-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - The Intended and Unintended Victims of Monopsony

-

- Book:

- Monopsony in Labor Markets

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp 62-80

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - No-Poaching Agreements

-

- Book:

- Monopsony in Labor Markets

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp 105-124

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Antitrust Policy in the United States

-

- Book:

- Monopsony in Labor Markets

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp 50-61

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- Monopsony in Labor Markets

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- Monopsony in Labor Markets

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Tables

-

- Book:

- Monopsony in Labor Markets

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp xiii-xiv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

10 - Monopsony and Merger Policy

-

- Book:

- Monopsony in Labor Markets

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp 160-180

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - Unions and Collective Bargaining

-

- Book:

- Monopsony in Labor Markets

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp 141-159

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Monopsony in Labor Markets

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp vii-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Preface

-

- Book:

- Monopsony in Labor Markets

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp xv-xvi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - Empirical Evidence of Monopsony in Labor Markets

-

- Book:

- Monopsony in Labor Markets

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp 32-49

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - Noncompete Agreements

-

- Book:

- Monopsony in Labor Markets

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp 125-140

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - The Economics of Monopsony

-

- Book:

- Monopsony in Labor Markets

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp 15-31

-

- Chapter

- Export citation