3.1 Forests, Governance, and Rights in Indonesia

Indonesia’s extensive forests constitute the third largest tropical rainforest in the world and have continued to disappear at a rate of .05 percent per year until recently.Footnote 427 The primary drivers of deforestation and forest degradation in Indonesia include legal and illegal logging, agricultural expansion (through the large-scale conversion of forests and peat lands for commercial oil palm plantations as well as small-holder cash-crop subsistence agriculture), mining (especially coal), and forest fires (both natural as well as human-induced in origin).Footnote 428 At the local level, deforestation has also been linked to lack of clarity regarding land and tenure rights; population growth; and the poverty and resource-dependence of rural communities.Footnote 429 Improvements in the governance of forests and land have accordingly been identified as having significant potential for reducing carbon emissions from forest-based sources in Indonesia and contributing to the world’s global climate mitigation efforts.Footnote 430

After achieving independence in 1949, Indonesia aggressively pursued the commercial exploitation of its forests and other natural resources on a large scale. In its Basic Agrarian Law, the post-independence presidency of Sukarno recognized three categories of land – state land (tanah negara), privately owned land (tanah hak), and customary lands (hak ulayat) – and limited the latter’s recognition to the extent that it was consistent with the national interest.Footnote 431 During the New Order, a period of authoritarian developmentalism that ran from the mid-1960s to the late 1990s, the Suharto regime consolidated the state’s authority over forests and related industries as part of a national drive for economic growth and development.Footnote 432 In the Basic Forestry Law adopted in 1967, the central government asserted control over all forest areas by removing forests from the scope of application of the Basic Agrarian Law and by not recognizing the existence of adat rights and lands in forests.Footnote 433 For the next several decades, Indigenous Peoples and local communities were systematically excluded from the management of their traditional lands and forests and were prevented from accessing and benefiting from forest resources.Footnote 434

During the reformasi era that followed the fall of Suharto in 1998, Indonesia rapidly transitioned from authoritarian rule to a decentralized system in which many political and administrative responsibilities, including those relating to forests and natural resources, were devolved to provincial, district, and municipal governments.Footnote 435 This process of liberalization and decentralization prompted rural communities across Indonesia to advocate for the recognition of their traditional rights to land and forests as part of a movement known as “adat revivalism.”Footnote 436 This period was also characterized by the emergence of an environmental movement in Indonesia and the adoption of a new set of laws and policies aimed at fostering the sustainable management of forests, including through new community-based forms of forest governance.Footnote 437

In practice, the recognition of adat community forests as well as the establishment of various forms of community forestry has remained riddled with obstacles, such that only 1 percent of Indonesia’s forests are legally managed by local communities.Footnote 438 Although very few of Indonesia’s forests have been formally devolved to local communities, numerous communities continue to assert informal claims to own, manage, and benefit from their customary forests.Footnote 439 As a result, forest governance in Indonesia is characterized by a series of ongoing conflicts between local communities seeking recognition of their forest and tenure rights and other actors in the forestry sector, including central, provincial, and district governments and corporations, who are reluctant to accede to requests for greater local authority over, and access to, forests.Footnote 440 Many of the barriers to the full implementation of the rights of local communities to manage their forests are thus similar to those barriers that drive deforestation and forest degradation in Indonesia, such as the competing economic interests of companies engaging in the exploitation of forests and other commodities; the collusion that exists between governments and the natural resource sector; and the broader inefficiencies, resource constraints, tensions, and ambiguities that undermine the effective development and enforcement of forestry laws and regulations across multiple orders of government.Footnote 441

The status and rights of Indigenous Peoples have an equally long and complicated history in Indonesia.Footnote 442 During the New Order, the Suharto regime denied the very existence of Indigenous Peoples on Indonesian territory and conceived of adat communities in negative terms, as “estranged and isolated communities” (masyarakat terasing) or as “village folk” (orang kampong) disconnected from the national process of development and requiring government assistance and resettlement.Footnote 443 The Suharto regime also adopted a number of policies that would have lasting and adverse consequences for the rights and well-being of adat communities. To begin with, the central government aggressively supported the development of the forestry, mining, agricultural, and tourism sectors and thereby facilitated, through the issuance of licenses as well as intimation and violence, the appropriation of the traditional lands of adat communities by commercial interests.Footnote 444 Moreover, the New Order government created new uniform village administration structures that displaced the local institutions of adat communities and disrupted customary systems of land management.Footnote 445 Finally, the Suharto regime facilitated the relocation of more than five million Indonesians from Java, Madura, and Bali to less populated lands in the outer islands inhabited by adat communities. This process of migration has led to protracted disputes and violent conflicts between migrant and adat populations that continue to this day.Footnote 446

During the 1980s and 1990s, adat communities began to establish organizations and networks to advocate for their rights and to develop relationships with external allies and supporters in the global Indigenous movement (such as the Ford Foundation, the Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact, the International Working Group on Indigenous Affairs, and the Forest Peoples Programme).Footnote 447 Taking advantage of the new opportunities for mobilization presented by the demise of the Suharto regime, more than 200 representatives of Indigenous Peoples organized the First Congress of Indigenous Peoples of the Archipelago in March 1999.Footnote 448 This congress marked the emergence of a new term that adat communities would use to describe their status as Indigenous Peoples, masyarakat adat, and led to the articulation of a slew of related demands and claims, most notably including recognition of their sovereignty and their rights to manage their traditional lands, forests, and resources.Footnote 449 This congress also resulted in the establishment of a new federation of Indigenous Peoples known as AMAN (Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantra Alliance) that now includes 1,992 Indigenous communities throughout Indonesia.Footnote 450 Over the last fifteen years, with the support and collaboration of international and domestic allies, AMAN has served as an important platform and network for representing the Indigenous Peoples of Indonesia, advocating for their rights vis-à-vis central and regional governments, strengthening their local capacities, institutions, and systems, and promoting the rights of Indigenous women and the education of Indigenous youth.Footnote 451

In addition to the flourishing of the Indigenous movement in Indonesia, the reformasi era was also characterized by a number of legal and policy developments that accorded new, though limited and often ambiguous, recognition to the existence and rights of masyarakat adat communities.Footnote 452 Notwithstanding some of these important gains, Indigenous Peoples have continued to struggle for the recognition of their distinctive status and the protection of their land and forest rights in Indonesia throughout the 2000s. When Indonesia signed the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007, the Indonesian government maintained that the concept of Indigenous Peoples was not applicable to Indonesia. It has also rejected domestic and international calls to acknowledge and protect the Indigenous rights of adat communities as defined under international law,Footnote 453 including by ensuring greater recognition of the land and forests rights and tenure systems of adat communities.Footnote 454 As a result of government inaction, Indigenous Peoples living in or near forests have suffered from a lack of tenure securityFootnote 455 and the large-scale deprivation of their lands for commercial exploitation or natural resource conservation.Footnote 456 They have also routinely experienced violent clashes with police, security forces, and other rural communities due to land conflicts with other actors in Indonesia.Footnote 457

3.2 The Pursuit and Governance of Jurisdictional REDD+ in Indonesia

The origins of jurisdictional REDD+ activities in Indonesia lay in the domestic and international commitments made by the government of President Yudhoyono throughout the second half of the 2000s.Footnote 458 At the domestic level, the Ministry of Forestry established the Indonesian Forest and Climate Alliance (IFCA) to hold an initial set of public consultations on REDD+ and develop eight studies on different aspects of the operationalization of REDD+ in Indonesia.Footnote 459 In addition, it also adopted regulations for the development and implementation of project-based REDD+ activities in 2008 and 2009.Footnote 460 Internationally, President Yudhoyono expressed his strong support for the establishment of a REDD+ mechanism within the UNFCCC, calling on developing countries to reduce their carbon emissions with the funding and support of developed countries.Footnote 461 In September 2009, Yudhoyono most notably committed Indonesia to reducing its emissions by 26 percent through unilateral action or by as much as 41 percent with appropriate levels of international support by 2020.Footnote 462

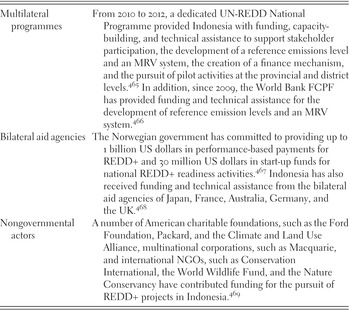

This commitment created favorable conditions for the pursuit of jurisdictional REDD+ activities in Indonesia, and opened the door for the delivery of aid and technical assistance by multilateral and bilateral actors.Footnote 463 As can be seen from Table 3.1, Indonesia’s jurisdictional REDD+ readiness efforts have benefited from the funding and assistance provided by a wide array of multilateral organizations, bilateral aid agencies, foreign corporations, and international NGOs.Footnote 464 The most significant form of support has come from the Norwegian International Climate and Forests Initiative (NICFI).Footnote 470 From May 2010 to March 2014, 58 percent of an initial US $30 million was disbursed to support the development of plans, systems, and capabilities for the pursuit of jurisdictional REDD+ across Indonesia as well as in the pilot province of Central Kalimantan.Footnote 471 In addition, Norway has funded the programs of numerous multilateral institutions as well as the activities of a large number of development and human rights NGOs in Indonesia.Footnote 472

Table 3.1 Overview of transnational support for jurisdictional REDD+ readiness activities in Indonesia

| Multilateral programmes | From 2010 to 2012, a dedicated UN-REDD National Programme provided Indonesia with funding, capacity-building, and technical assistance to support stakeholder participation, the development of a reference emissions level and an MRV system, the creation of a finance mechanism, and the pursuit of pilot activities at the provincial and district levels.Footnote 465 In addition, since 2009, the World Bank FCPF has provided funding and technical assistance for the development of reference emission levels and an MRV system.Footnote 466 |

| Bilateral aid agencies | The Norwegian government has committed to providing up to 1 billion US dollars in performance-based payments for REDD+ and 30 million US dollars in start-up funds for national REDD+ readiness activities.Footnote 467 Indonesia has also received funding and technical assistance from the bilateral aid agencies of Japan, France, Australia, Germany, and the UK.Footnote 468 |

| Nongovernmental actors | A number of American charitable foundations, such as the Ford Foundation, Packard, and the Climate and Land Use Alliance, multinational corporations, such as Macquarie, and international NGOs, such as Conservation International, the World Wildlife Fund, and the Nature Conservancy have contributed funding for the pursuit of REDD+ projects in Indonesia.Footnote 469 |

Pursuant to its bilateral agreement with Norway, the government of President Yudhoyono established a REDD+ Taskforce in the Summer of 2010 that brought together representatives of the National Development Planning Agency (BAPPENAS), the Ministry of Forestry, the Ministry of Finance, the State Ministry for Environment, the National Land Agency (BPN), the Secretariats of the Cabinet and Presidential Office, and the President’s Work Unit for the Supervision and Management of Development (UKP4). Reporting directly to the President, its main tasks included elaborating a National REDD+ Strategy and undertaking preparations for the establishment of REDD+ institutions, financial mechanisms, and measurement, reporting, and verification systems. This REDD+ Taskforce was also supported by a number of technical working groups, comprised of experts from government, academia, and civil society, working on key aspects of REDD+ readiness (such as governance, multi-stakeholder processes, safeguards, or finance).Footnote 473 This initial taskforce ended its mandate in June 2011, and was thereafter succeeded by a second and third taskforce and finally by a special team established with the express purpose of preparing for the establishment of a REDD+ Agency.Footnote 474 This REDD+ Agency was created in August 2013 and was tasked with the responsibility of managing and coordinating all jurisdictional REDD+ activities in Indonesia.Footnote 475

3.3 The Rights of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities in Jurisdictional REDD+ Readiness Activities in Indonesia

3.3.1 Rights in the Development of a National REDD+ Strategy

In the early stages of Indonesia’s jurisdictional REDD+ readiness efforts, various ministries and agencies engaged in policy research and planning that would lay the groundwork for the later development of a national REDD+ strategy. During the fall of 2007, the IFCA organized a series of national workshops and developed eight studies on different aspects of the operationalization of REDD+ in Indonesia. These studies were eventually brought together into a consolidated report released by the Ministry of Forestry in early 2008 known as REDD-I. This report identified the emerging international consensus around the key elements of REDD+ and set out the next steps for the piloting of REDD+ mechanisms and activities in Indonesia.Footnote 476 Although it acknowledged the role that clarifying land tenure and forest management rights and engaging with local communities could play in the success and effectiveness of REDD+ activities,Footnote 477 it did not address, nor refer to, the participatory or substantive rights of Indigenous Peoples or local communities.Footnote 478 On the other hand, in July 2008, BAPPENAS issued a national development plan focused on Indonesia’s response to climate change, in which forestry was identified as a priority area for domestic climate mitigation efforts.Footnote 479 This report recognized the significance of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and forest-dependent communities and most notably stated that: “Crucial for successful implementation of REDD-I will be the acknowledgement and inclusion of the rights of indigenous people and rural people who depend upon forest resources for their livelihoods, in Indonesia, this number might exceed 60 million people.”Footnote 480 The contrast between these two reports reflected the traditional reluctance of the Ministry of Forestry to embrace participatory and substantive rights that might threaten its stranglehold on forest governance and associated revenues and the comparatively greater openness of BAPPENAS to the rights and concerns of Indigenous Peoples and rural communities.Footnote 481

Another important process that fed into the development of a national REDD+ strategy was the preparation and submission of an R-PP by the Ministry of Forestry under the FCPF Readiness Mechanism. This R-PP was developed by an ad hoc inter-ministerial working group and drew on the studies prepared by IFCA as well as a set of consultations with national, regional, and local government representatives, NGOs, local communities, international partners, and the private sector carried out in 2008 and 2009.Footnote 482 These consultations enabled Indigenous activists to raise concerns with government officials about their approach to Indigenous peoples and local communities in the drafting of the R-PP, specifically the lack of recognition of their Indigenous status and their rights to lands, resources, and to FPIC.Footnote 483 The R-PP submitted to the FCPF in May 2009 only partially addressed some of these rights-related issues, however. On the one hand, the R-PP acknowledged the importance of ensuring that Indigenous Peoples and forest dwellers could participate in, and benefit from, the implementation of REDD+ activities and committed to consulting them in the development of policies and programs for REDD+ in Indonesia.Footnote 484 On the other hand, the R-PP did not address the potential risks that REDD+ might pose to the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities, nor did it recognize the distinctive set of rights held by Indigenous Peoples, claiming instead that “[f]orest dwellers and indigenous people, like other Indonesian citizens, have the same rights and responsibilities as Indonesian citizens according to national regulations.”Footnote 485

Unsurprisingly, the R-PP submitted by Indonesia to the FCPF in May 2009 attracted criticisms at home and abroad. In particular, AMAN and Sawit WatchFootnote 486 addressed a letter to the Minister of Forestry (with CCs to key officials in the FCPF and the World Bank), in which it criticized the Indonesian government for failing to fully and adequately consult with Indigenous Peoples and to recognize their participatory and substantive rights (as protected through the FCPF Charter as well as international human rights law more broadly). AMAN and Sawit Watch closed the letter by calling on the Indonesian government to “establish an effective process of consultation and collaboration with Indigenous Peoples’ organizations and authorities to enable their participation in the decisions about the development of REDD that will impact on their lives.”Footnote 487 In their reviews of Indonesia’s R-PP, the third-party experts from the technical advisory panel recommended that Indonesia take additional steps to ensure the involvement of Indigenous Peoples and forest-dependent communities in its REDD+ policy planning process, assess the potential negative impacts of REDD+ on the livelihoods of forest communities and Indigenous Peoples, and address the issue of the distribution of benefits.Footnote 488 At its third meeting in June 2009, the FCPF Participants’ Committee arrived at similar conclusions and moreover discussed the application of the World Bank’s social and environmental safeguards as well as the consideration of the land and forest tenure and resource rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.Footnote 489 Upon approving Indonesia’s R-PP in June 2009, the FCPF Participants’ Committee thus requested that the World Bank and Indonesia work closely with one another to resolve these issues before the conclusion of a grant agreement.Footnote 490 After two years of additional due diligence to, among other things, clarify the application of the World Bank’s Operational Policy on Indigenous Peoples to Indonesia’s jurisdictional REDD+ readiness efforts,Footnote 491 the Indonesian government and the World Bank concluded a readiness grant agreement in June 2011.Footnote 492

In any case, the development of a national REDD+ strategy for Indonesia truly began after its inclusion as a key deliverable in the Letter of Intent Indonesia concluded with Norway in May 2010.Footnote 493 This task was initially entrusted to BAPPENAS, which worked with other ministries to create a process and structure for this purpose.Footnote 494 This led to the establishment, in July 2010, of a Steering Committee bringing together government officials from several ministriesFootnote 495 as well as an Implementation Team comprised of representatives from government, international organizations, and civil society.Footnote 496 Given that the Letter of Intent specified that “all relevant stakeholders” (including “Indigenous Peoples, local communities and civil society”) should be given the opportunity to fully and effectively participate in the design of REDD+ policies and plans,Footnote 497 BAPPENAS worked closely with the UN-REDD Programme to develop a plan for holding a series of multi-stakeholder consultations at the national and regional levels.Footnote 498

Throughout the summer of 2010, several drafts of the strategy were produced and discussed by various officials and stakeholders as well as presented for public feedback in August 2010.Footnote 499 These efforts culminated in a first complete draft released to the public in September 2010. In comparison with the R-PP submitted to the FCPF in May 2009, this draft national strategy was much more attentive to the prevalence of conflicts over land tenure and forest rightsFootnote 500 and the lack of recognition of the traditional rights held by “Indigenous communities”: “Legal dualism on the acknowledgement of traditional rights in forest area and non-forest area becomes one of the tenurial issues. The inexistence of formal rights for traditional societies result in the inability to make a natural resource-based decision in their traditional territory weakens their potential abilities in supervising forest area. At the same time, procedures which enable them to be acknowledged as legal society seem very difficult and long.”Footnote 501 This draft strategy also identified the unjust distribution of economic benefits from forestry between governments and forest-dependent communities as a driver of deforestation and forest degradationFootnote 502 and thus proposed an economic empowerment program to strengthen and diversify their livelihoods and sources of incomes.Footnote 503 Finally, the draft strategy noted that the establishment of a REDD+ mechanism in Indonesia should “[n]ot only consider the economic aspect but also the environment and social aspects, including the traditional and local community rights as well as the participation role of various parties to ensure that the reduction of deforestation and forest degradation is effective and permanent.”Footnote 504 To these ends, it envisaged various forms of cooperation with local communitiesFootnote 505 and anticipated the development of a “non-carbon” MRV system that would include social and environmental safeguards.Footnote 506 Despite its greater acknowledgement of the importance of land rights and tenure security and the need to work collaboratively with local communities, this first draft did very little to advance the recognition and protection of the rights of Indigenous Peoples as such.

This first draft was subsequently discussed through public consultations held with multiple stakeholders (including CSOs working with Indigenous Peoples) across six regions in Indonesia in October 2010.Footnote 507 In response to the release of the first draft strategy, a coalition of Indonesian CSOs working at the intersections of human rights and environmental issues offered a number of recommendations to BAPPENAS.Footnote 508 First, these organizations called for the protection of the forest rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities to serve as one of the main objectives of Indonesia’s national REDD+ strategy.Footnote 509 Second, they requested that the strategy refer to, and incorporate, standards set by international human rights instruments, including the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.Footnote 510 Third, they advocated for the recognition of the role and contribution of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in the sustainable management of forests, citing academic research on the effectiveness of community forestry in supporting carbon sequestration.Footnote 511 Finally, they noted that the strategy did not actually provide solutions for the lack of forest tenure clarity and thus proposed the adoption of measures that could actually resolve forest tenure conflicts.Footnote 512

After one final expert’s meeting, a revised draft of the national REDD+ strategy was prepared in November 2010.Footnote 513 This revised draft responded to many of the demands formulated by the Indonesian CSOs, especially with respect to the participatory rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. Indeed, the second draft strategy consistently emphasized the importance of ensuring the participation of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in the development and implementation of REDD+ activitiesFootnote 514 and, most notably, endorsed the view that their involvement in forest management was an effective way of reducing carbon emissions from forest-based sources.Footnote 515 In particular, the involvement of “indigenous peoples and forest communities” was presented as “essential” due to the potential role that local knowledge can play in the reduction of carbon emissions as well as the need to avoid the adverse consequences that can be caused by how forests are utilized by other parties.Footnote 516 As a result, the strategy committed to a range of activities that aimed to increase the participation and capacity of Indigenous Peoples (among other stakeholders) in the implementation of REDD+ activities, maintain and build upon their local knowledge in relation to sustainable forest management, establish fair and effective mechanisms to resolve conflicts between the multiple actors that use or depend upon forests, and ensure the application of the principle of free, prior, and informed consent of local communities.Footnote 517 On the other hand, while the second draft strategy reiterated the problems associated with conflicts over forest tenure and use and the lack of recognition of Indigenous rightsFootnote 518 and identified the settlement of these issues as integral to the operationalization of REDD+,Footnote 519 it did not provide much clarity on the way in which disputes over forest tenure might be resolved. Although international and domestic NGOs welcomed the formal introduction of rights language and principles in the development of Indonesia’s national REDD+ strategy, they also highlighted the challenges associated with the lack of access to land and resources experienced by Indigenous Peoples and local communities and the need to establish “effective and accessible mechanisms of redress that would help resolve the numerous and protracted land feuds across the country.”Footnote 520

In late 2010, the second draft of the national REDD+ strategy was then handed over by BAPPENAS to the REDD+ Taskforce, which established a working group comprising senior government officials and nongovernmental experts to prepare a final draft.Footnote 521 This working group held an additional series of national and subnational consultations with multiple stakeholders in several provincial capitals in 2011 and 2012.Footnote 522 It also had to contend with an alternative draft REDD+ strategy that was released by the Ministry of Forestry in April 2012.Footnote 523 In the end, this working group produced a comprehensive draft strategy that sought to integrate the drafts prepared by BAPPENAS and the Ministry of ForestryFootnote 524 as well as the feedback received from various governmental representatives and nongovernmental stakeholders.Footnote 525 The strategy was then finalized by the REDD+ Taskforce and officially released in June 2012.Footnote 526

Indonesia’s National REDD+ Strategy is built on five pillars: (1) the creation of an institutional system for REDD+ (including a REDD+ agency and the development of a funding instrument known as FREDD-I as well as an MRV system); (2) the establishment of a sound legal and regulatory framework for forest governance and the implementation of REDD+ activities at the jurisdictional and project levels; (3) the implementation of strategic programs focused on the conservation and rehabilitation of forests and the sustainable management of agriculture, forestry, and mining activities across landscapes; (4) the promotion of a paradigm shift in the way in which land and forests are used and governed by relevant actors; and (5) the inclusion and involvement of multiple stakeholders in the design and operationalization of REDD+ activities.Footnote 527 Each of these pillars addresses in significant and concrete ways the rights and concerns of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.Footnote 528 With respect to land and resource rights, the strategy states that “[t]he people have a constitutional right to certainty over boundaries and management rights for natural resources” and that “[l]and tenure reform is an important prerequisite to create the conditions required for successful implementation of REDD+.”Footnote 529 Accordingly, the strategy provides for the Indonesian government to have the National Land Agency undertake “a survey of land occupied by indigenous peoples and other communities,” resolve disputes over land tenure “using existing statutory out-of-court settlement mechanisms,” and ensure that “the principle and processes of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) are internalized in the issuance of all permits for the exploitation of natural resources.”Footnote 530 In addition, the strategy commits to reducing the bottlenecks of “processes to delineate forest areas (…) as a sign of respect towards parties with rights to land,”Footnote 531 supporting the development of “sustainable local economies based on alternative livelihoods, expanded job opportunities, and the management of forests by local communities,”Footnote 532 and implementing sustainable forest management, including in “timber areas cultivated by local communities, communal forests, village plantations.”Footnote 533

As far as participatory rights are concerned, the strategy clearly recognizes the importance of facilitating and supporting public participation in the design and implementation of REDD+Footnote 534 and most notably provides that the REDD+ Agency “will implement and apply the principles of FPIC in all REDD+ programs and projects” in order to “ensure fairness and accountability for indigenous and local peoples whose lives and rights will be affected by REDD+ activities.”Footnote 535 The strategy also sets out a series of detailed principles that should guide the implementation of FPIC in the context of Indonesia’s jurisdictional REDD+ activities.Footnote 536 In this regard, it is worth noting that the principle of FPIC is conceived as applying not only to Indigenous Peoples (as would be the case under international law), but also to local communities who are affected by the implementation of REDD+.

With respect to the development of a framework and information system for social and environmental safeguards, the strategy specifies the protection of human rights as a core objective: “it is imperative to specifically design the social safeguards framework for the protection and benefit of vulnerable groups, including indigenous peoples and local communities living in and around forests, whose livelihoods depend on forest resources; women, who face the full brunt of changes in family income; and other societal groups, whose social, economic, and political status put them in a weak position in terms of fulfillment of their human rights.”Footnote 537 Further, the strategy sets a number of minimal requirements for the preparation of the criteria and indicators in Indonesia’s safeguards framework.Footnote 538 The strategy also provides the National REDD+ Agency with the responsibility of further developing and implementing a safeguards information system, which should acknowledge the “the right of the public to land and forests that accommodates not only formal legal recognition, but also indigenous law rights and historical claims.”Footnote 539

Finally, Indonesia’s National REDD+ Strategy discusses the importance of developing fair, transparent, and accountable systems and mechanisms for benefit-sharing.Footnote 540 Here again, the strategy accords significant importance to the land and resource rights of local communities, specifying that parties with “rights over the area off the REDD+ program/project/activity location have the right to payment” and requiring the clarification of the status of land rights in a given area and the distribution of benefits to communities that hold these rights or otherwise contribute to the reduction of carbon emissions.Footnote 541 The eventual development of this system also falls to the National REDD+ Agency, which is tasked with formulating and operationalizing a funding instrument for REDD+.Footnote 542

The National REDD+ Strategy has been greeted with cautious enthusiasm by Indonesian CSOs advocating for the rights and interests of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. For the most part, the National REDD+ Strategy has been seen as a promising development in the recognition and protection of the participatory and resource rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.Footnote 543 Recognizing that the National REDD+ Strategy remains a nonbinding policy document, the advocacy efforts of these organizations has thus shifted to pressing for its application as well as lobbying for the integration of rights in the subnational REDD+ strategies being developed in several provinces.Footnote 544 In January 2013, a coalition of forty-eight Indonesian NGOs, including AMAN and several regional branches of AMAN, called on the Indonesian government to implement the National REDD+ Strategy, arguing that: it “was prepared with an aim to improve Indonesian forest governance fundamentally and comprehensively,” its preparation “was relatively transparent” and “involved relevant stakeholders,” and that its comprehensive implementation would “respect the rights of indigenous peoples and local communities.”Footnote 545 The fact that a wide coalition of Indonesian NGOs including IPOs and human rights NGOs would call for the implementation of the National REDD+ Strategy is perhaps the best indicator of the progressive manner in which this strategy recognizes and aims to protect the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in the context of REDD+.

3.3.2 Rights in the Development of Social and Environmental Safeguards for REDD+

The development of social and environmental safeguards in Indonesia began at the end of 2010. It was triggered by the pressure exerted by Norway and domestic civil society actors as well as the adoption of the Cancun Agreements, which made them a necessary component of jurisdictional REDD+ readiness.Footnote 546 The efforts to develop safeguards for REDD+ have unfolded in a fragmented manner, with the REDD+ Taskforce meant to be focusing on the substance of the safeguards themselves and the Ministry of Forestry expected to take the lead in establishing an information system for reporting on the safeguards to international donors. As a result, the development of social and environmental safeguards has taken place through parallel processes and led to inconsistent outcomes.Footnote 547

During 2011 and 2012, a multi-stakeholder working group of the REDD+ Taskforce developed a first draft of a policy for the Principles, Criteria, and Indicators for REDD+ Safeguards in Indonesia (known as PRISAI). These safeguards drew on several sources, including international human rights law and policy, the standards set by the Community, Climate & Biodiversity Alliance, and relevant elements of Indonesian law.Footnote 548 This initial draft was subsequently revised on the basis of consultations involving representatives from government, civil society, multilateral donors, and the private sector as well as the feedback gathered from four pilot projects that tested a preliminary version of the safeguards at the local level.Footnote 549 This process resulted in a set of ten social and environmental safeguards that are meant to apply to all REDD+ activities, whether carried out at the jurisdictional or project level.Footnote 550 The social safeguards included in principles 4 to 7 address the participatory and substantive rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.Footnote 551 Principle 4 includes criteria and indicators that provide for the identification, recognition, and protection of the land and resource rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities, including the requirement of the right to free, prior, and informed consent in accordance with the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and mechanisms to resolve conflicts and address grievances in relation to land rights issues in the context of REDD+ activities.Footnote 552 Principle 5 requires respect for the traditional knowledge, values, and rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities and their integration into the design and implementation of REDD+ activities.Footnote 553 Principle 6 mandates the full and effective participation of all stakeholders at all stages in the design, implementation, and evaluation of REDD+ activities, with a special focus on women and marginalized communities.Footnote 554 Finally, Principle 7 provides for the equitable, transparent, and participatory sharing of the benefits of REDD+ among all rights holders and relevant stakeholders, based on their rights as well as their contribution to reductions in carbon emissions.Footnote 555 All told, these social safeguards are largely consistent with the National REDD+ Strategy’s expansive approach to the recognition and protection of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

Further, in line with the requirements set by the UNFCCC COP at its sixteenth and seventeenth sessions in Cancun and Durban, the Ministry of Forestry has led efforts to develop a system for providing information on how social and environmental safeguards have been addressed and respected in the context of the implementation of REDD+ activities in Indonesia.Footnote 556 Throughout 2011 and 2012, the Centre for Standardization and Environment of the Ministry of Forestry, with the bilateral assistance provided by the German government, led a process to prepare Principles, Criteria, and Indicators for a System for Providing Information on REDD+ Safeguards Implementation in Indonesia. The Centre for Standardization and Environment commissioned independent analysis of Indonesia’s laws and their compatibility with the safeguards included in the Cancun Agreements, and organized an iterative series of national workshops, focus group discussions, and interviews with multiple stakeholders on various drafts and elements of such a system.Footnote 557 The safeguards information system developed by the Centre for Standardization and Environment includes seven principles, seventeen criteria and thirty-two indicators that were developed on the basis of the guidance provided by the Cancun Agreements, relevant strands of Indonesian law, and the standards applicable under the Forest Stewardship Council and the World Bank Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment procedure.Footnote 558 Of particular relevance to the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities are Principle 3 on the rights of “Indigenous and local communities” and Principle 4 on the effectiveness of stakeholder participation. Principle 3 includes criteria that provide that REDD+ activities shall “include identification of the rights of indigenous and local communities, such as tenure, access to and utilization of forest resources and ecosystem services, with increasing intensity at sub-national and site-level scales”; “include a process to obtain the free, prior, informed consent of affected indigenous and local communities before REDD+ activities commence”; “contribute to maintaining or enhancing the social economic wellbeing of indigenous and local communities, by sharing benefit fairly with them, including for the future generations”; and “recognize the value of traditional knowledge and compensate for commercial use of such knowledge where appropriate.”Footnote 559 Principle 4 is comprised of criteria that aim to ensure that REDD+ activities “shall be based on proactive and transparent identification of relevant stakeholders, and the engagement of them in planning and monitoring processes, with an increasing level of intensity from national level to site level scales” and “include procedure or mechanisms for resolving grievances and disputes.”Footnote 560

While these criteria would appear to provide an important recognition of participatory and substantive rights, this document is equivocal in its approach to the status and rights of Indigenous Peoples. First, although it uses the term Masyarakat adat, the English translation uses the term Indigenous communities, rather than Indigenous Peoples, raising questions regarding whether international protections accorded to the latter are intended to apply. Second, the document specifies in its glossary that “[o]n signing the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Indonesia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has clarified that the concept of ‘indigenous peoples’ in Indonesia must be interpreted on the basis that almost all Indonesians (with the exception of ethnic Chinese) are considered indigenous and thus entitled to the same rights” and that “the government has rejected calls for special treatment by groups identifying themselves as indigenous.”Footnote 561 This further suggests an unwillingness to recognize that Indigenous Peoples hold a particular status and set of rights under international law. Moreover, its glossary also provides an ambivalent definition of the right to FPIC, which is described in the following terms: “Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (or Consultation, per Government of USA and WB), a process that provides opportunity for indigenous and/or local communities to reject or approve activities in forests to which they have rights.”Footnote 562

As of August 2014, the National REDD+ Agency is moving forward with the development and coordination of a REDD+ safeguards information system. In doing so, it will need to reconcile some of the inconsistencies between the safeguards included in the PRISAI prepared under the auspices of the REDD+ Taskforce and those that are included in the SIS policy document drafted by the Centre for Standardization and Environment of the Ministry of Forestry.Footnote 563 All told, the development of social and environmental safeguards for REDD+ reflect two broader trends in the relationship between the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities and the pursuit of jurisdictional REDD+ activities in Indonesia. For one, these two sets of safeguards aim to recognize and protect an expanded set of participatory and substantive rights for both Indigenous Peoples and local communities. For another, a comparison of the safeguards adopted by the REDD+ Taskforce and the Ministry of Forestry reveals the latter’s reluctance to accord an extensive set of rights to Indigenous Peoples and local communities or to acknowledge the international protection accorded to them under international law.

3.4 Explaining the Conveyance and Construction of Rights through Jurisdictional REDD+ Activities in Indonesia

At the outset of Indonesia’s jurisdictional REDD+ readiness efforts in 2008 and 2009, the policy documents developed by the Ministry of Forestry largely ignored the participatory and substantive rights of Indigenous Peoples.Footnote 564 While this attracted significant criticism from domestic NGOs as well as the various international actors associated with the review and approval of an R-PP within the FCPF,Footnote 565 critical responses did not engender any immediate shifts in Indonesian policy. The clearest evidence that this initial pressure from below and from above had little immediate effect is that Indonesia strongly opposed the inclusion of any references to the rights of Indigenous Peoples in the Letter of Intent that it signed with Norway in May 2010Footnote 566 and, moreover, failed to recognize Indigenous rights in the first draft National REDD+ Strategy that it released in September 2010.Footnote 567

Although Norwegian officials failed to persuade Indonesian officials to change their policies with respect to Indigenous Peoples in the Letter of Intent itself, they did require that Indonesia ensure the full and effective participation of stakeholders (specifically including “Indigenous Peoples, local communities and civil society”) in the design and implementation of REDD+.Footnote 568 In this context, Indonesian officials adopted legal norms relating to the full and effective participation of stakeholders as part of the Letter of Intent because the material benefits of obtaining funding exceeded the political costs associated with adopting these norms (cost-benefit adoption).Footnote 569 This instrumentally motivated commitment opened the door for international and domestic actors to work closely with BAPPENAS to plan and hold a series of multi-stakeholder consultations regarding the development of a REDD+ strategy at the national and regional levels.Footnote 570 In turn, the public release of the first National REDD+ Strategy in September 2010 provided an additional window for a coalition of Indonesian NGOs to advocate for the recognition and protection of the participatory and substantive rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.Footnote 571 This advocacy paid immediate dividends, as the second draft National REDD+ Strategy released in November 2010 included new references to the term “Indigenous Peoples,” emphasized the importance of their participation, and recognized the existence of the principle of FPIC.Footnote 572 This draft also recognized the problems associated with the lack of recognition of the land and resource rights of Indigenous Peoples and the need to resolve conflicts over land tenure as part of the domestic operationalization of REDD+.Footnote 573 As was discussed above, the final version of Indonesia’s National REDD+ Strategy as well as its safeguards policy built upon these initial gains in the recognition of the participatory and substantive rights of Indigenous Peoples, and even extended them to local communities.Footnote 574

I argue that the conveyance of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in Indonesia’s jurisdictional REDD+ readiness efforts can be primarily explained by the mobilization of domestic NGOs that succeeded in pressuring the National REDD+ Taskforce to enact these legal norms in its jurisdictional REDD+ policies.Footnote 575 In their mobilization, these NGOs drew on the symbolic leverage provided by exogenous legal norms relating to the status and rights of Indigenous Peoples enshrined in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and other key legal instruments applicable to REDD+, such as the World Bank’s operational safeguards and the Cancun Agreements.Footnote 576 The effectiveness of these advocacy efforts were also enhanced by the broad and well-connected nature of the coalition of Indonesian NGOs that emerged as important actors in Indonesia’s jurisdictional REDD+ readiness efforts. For one, these NGOs represented or worked with both Indigenous Peoples and other forest-dependent communities, and emanated from Indonesia’s human rights and environmental movements.Footnote 577 For another, they received substantial financial support from international NGOs (particularly through funding provided by Norway to support civil society actors)Footnote 578 and benefited from their participation in transnational networks focusing on advancing the rights of Indigenous Peoples and forest-dependent communities around the world.Footnote 579

In addition, these Indonesian NGOs were able to take advantage of the openings provided by the particular opportunity structure of the jurisdictional REDD+ readiness policy process in Indonesia.Footnote 580 Specifically, they took advantage of the consultative and inclusive manner in which the REDD+ strategy and safeguards were developed,Footnote 581 the reformist officials and experts that were appointed to the National REDD+ Taskforce,Footnote 582 and the relative marginalization of the Ministry of Forestry as a policy actor.Footnote 583 Ultimately, the ability of domestic NGOs to mobilize and exert influence in the jurisdictional REDD+ readiness process spoke both to their skills and resources as intermediaries sitting at the intersections of Indonesian and international law as well as to the role played by exogenous actors in providing resources and creating openings that supported their mobilization.Footnote 584

While the mechanism of mobilization played a key role in triggering the conveyance of rights in Indonesia’s jurisdictional REDD+ readiness efforts, the way in which these rights were eventually constructed in Indonesia’s National REDD+ Strategy and its Principles, Criteria, and Indicators for REDD+ Safeguards can be best explained by the mechanism of persuasive argumentation. As a result of Indonesian government officials’ participation in an extensive series of multi-stakeholder consultations and informal contacts with domestic NGOs throughout Indonesia over several years,Footnote 585 internal discussions within the National REDD+ Taskforce and its drafting groups working on the REDD+ strategy and safeguards,Footnote 586 and their ongoing dialogue with international interlocutors (particularly officials from Norway and other bilateral agencies, the UN-REDD Programme, the FCPF readiness mechanism, and other developing countries in Asia working on jurisdictional REDD+ readiness such as the Philippines),Footnote 587 government officials developed and internalized a new norm about the appropriateness of respecting the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in the context of REDD+.Footnote 588 The construction of this norm was most notably facilitated by the novelty of the pursuit of jurisdictional REDD+ efforts in Indonesia as well as the fact that several members of the National REDD+ Taskforce did not have a background in forestry (or for that matter in international law),Footnote 589 which enabled them to be open to the development of new norms concerning the importance and extent of Indigenous rights in the context of REDD+.Footnote 590

In addition, although international law only accords a distinctive and enhanced set of rights (such as the right to free, prior, and informed consent) to Indigenous Peoples, the outcomes of the jurisdictional REDD+ readiness process in Indonesia reflect the construction of a new shared understanding regarding the application of these exogenous legal norms to both Indigenous Peoples and local communities. In line with the Indonesian government’s traditional reluctance to recognize the distinctive status of Indigenous Peoples (as it is understood under international law), exogenous legal norms relating to Indigenous rights were translated by Indonesian officials into hybrid legal norms that apply to masyarakat adatFootnote 591 as well as to local communities.Footnote 592 As such, the legal norms relating to the participatory and substantive rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in the context of Indonesia’s jurisdictional REDD+ readiness efforts reveal the enduring influence of an endogenous normFootnote 593 that has acted as a barrier to the internalization of international norms that define Indigenous Peoples as holding a particular status and set of rights under international law.

3.5 REDD+ and the Future of Indigenous and Community Rights in Indonesia

This chapter has argued that the pursuit of jurisdictional REDD+ activities has resulted in the conveyance and construction of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in Indonesia. The process for developing a strategy and safeguards policy for jurisdictional REDD+ was shown to have provided a unique opportunity for Indigenous Peoples and other civil society actors to pressure the Indonesian government into recognizing the legitimacy of legal norms relating to Indigenous Peoples and their rights in the context of REDD+. The jurisdictional REDD+ policy-making process also led Indonesian officials to develop new hybrid legal norms that extended rights accorded to Indigenous Peoples under international law to all local communities. In a country that has traditionally not recognized the rights of Indigenous Peoples and other local communities in the context of its forest laws and policies, the emergence of these legal norms in Indonesia’s National REDD+ Strategy and safeguards policy is nothing short of groundbreaking. In the words of two leading activists working on the rights of Indigenous Peoples and forest-dependent communities in Indonesia: “We would argue that more has been achieved in forest protection and the rights of indigenous peoples in Indonesia since the signing of the Indonesia-Norway agreement than over the course of the previous 15 years.”Footnote 594

The key question that remains is whether these newly recognized participatory and substantive rights will in fact be respected and implemented by the Indonesian government in the context of the operationalization of its jurisdictional REDD+ policies and institutions and, more broadly, within the field of forest governance. In particular, the fact that many government officials and politicians and other segments of Indonesian society have not wholeheartedly accepted these rights may limit their ability to lead to concrete improvements in the lives of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. One striking example of the broader set of views that exist with respect to the rights of Indigenous Peoples is the official statement made by the Indonesian Ministry of Affairs before the UN Human Rights Council in September 2012, which stated that “[g]iven its demographic composition, Indonesia, however, does not recognize the application of the indigenous people concept as defined in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in the country.”Footnote 595 Most importantly, the decision made by the administration of President Joko Widodo to close the National REDD+ Agency and to transfer responsibility for the implementation of the National REDD+ Strategy over to a newly amalgamated Ministry of Environment and Forestry may significantly encumber the concrete implementation of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities, especially in terms of the recognition and protection of their community land tenure and forest rights.Footnote 596 Indeed, given the manner in which the Ministry of Forestry has traditionally supported the agricultural, logging, and mining industries and its hesitant embrace of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in the context of REDD+, it is reasonable to expect that this decision may hamper efforts to clarify, recognize, and secure the forest tenure rights of local communities.Footnote 597 As such, it is entirely possible that the ways in which the broader politics of land and forest governance have hindered the progress of several REDD+ projects as well as affected their capacity to strengthen community rights to land and forests may ultimately impede the implementation of the rights that have been enacted in Indonesia’s policies for jurisdictional REDD+ readiness.Footnote 598

All the same, there are several reasons to think that the recognition of rights in the context of jurisdictional REDD+ policies may ultimately have durable and significant effects. First, the recognition of rights in Indonesia’s policies on jurisdictional REDD+ provides new opportunities and rhetorical tools for the mobilization of Indigenous Peoples and local communities around the protection of their rights. In fact, domestic Indonesian NGOs have already begun taking advantage of the gains achieved through REDD+ by, most notably, calling on the Indonesian government to implement the National REDD+ Strategy.Footnote 599

Second, and perhaps most importantly, the emergence of rights in Indonesia’s jurisdictional REDD+ readiness policies has fed into, and been accompanied by, broader legal and political developments in Indonesia. The most important such development is a landmark ruling of the Indonesian Constitutional Court in May 2013, which interpreted the Revised Forestry Law as providing that adat forests exist as a standalone form of forest tenure and are therefore owned by masyarakat adat, rather than the State.Footnote 600 There are a number of ways in which this ruling has been connected to the pursuit of REDD+ in Indonesia.Footnote 601 In concrete terms, this ruling stemmed from a petition filed by AMAN, which was supported, in part, by funding provided by the Rainforest Foundation Norway as well as mapping conducted by the Samdhana Institute – both of which were financed by the Norwegian International Climate and Forests Initiative.Footnote 602 While the Ministry of Forestry has been equivocal in its response to this constitutional ruling, the actors and institutions associated with the operationalization of jurisdictional REDD+ in Indonesia have served as a vehicle for its implementation. Indeed, in September 2014, nine government ministries and institutions launched a “National Programme for the Recognition and Protection of Customary Communities (PPMHA) through the REDD+ mechanism” that will be spearheaded by the National REDD+ Agency.Footnote 603 To the extent that this program replicates many of the factors that contributed to the conveyance and construction of rights in the jurisdictional REDD+ policy-making process in the first place, it has significant potential for ensuring that the participatory and substantive rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities are fully respected, protected, and fulfilled on the ground.