Thus Christopher Marlowe's theatrical Mongol ruler (Timur) proclaims that it is the sword (his “pen”) that ultimately determines the mapping of empires. In his play, Tamburlaine, first performed c. 1587, Marlowe (1564–1593) created an artful counterpart to the maps of his day, a sovereign space concocted out of a rather indiscriminate mixing of myth, history, and fiction. He collapsed time and space to place Muhammad and Jove in the same firmament, meld the medieval with the early modern, and jumble the territories of the Afro-Eurasian oikumene into one great imperial backdrop.Footnote 2 Marlowe's English audience (elite and common) may or may not have known the historical figures of Timur (r. 1370–1405) and the Ottoman sultan Bayezid I (r. 1389–1402). But in the play these rulers' times, locations, compatriots, and identities were mutable, subject to the vagaries of drama, history, memory, education, artistic convention, and strategic interest. Just so, as early modern Europeans created representations of territory, they employed those same factors to delineate an Ottoman imperial space (and identity) that was as much a function of cultural imagination as it was a product of contemporary technologies of print and measurement. Such representations, particularly those found on maps, form the subject of this volume. It examines the rhetorical construction of the Ottomans in the texts and images of the Christian kingdoms of early modern Europe and the inscribing of Ottoman territory, sovereignty, and identity onto maps, employing Ottoman self-mapping as a comparative foil. Maps, broadly construed, complicate the notion that representing the Ottomans was an evolutionary process that typed the empire as terrible in the sixteenth century and domesticated in the eighteenth. If we dismiss Marlowe's swirling of character, border, time, and space as merely fanciful or theatrical, we miss the point. For, in the early modern era, mapping was both a pictorial narration of territory and events and a process by which events were subordinated to history, memory, and desire.

With their conquest of the great Christian and Muslim capitals, Constantinople in 1453 and Cairo in 1517, the Ottoman Turks captured the imagination of observers across the Afro-Eurasian world, asserting their identity as one of the most powerful empires of the early modern era. The Ottomans had become a European empire in the fifteenth century, crossing the Danube into Wallachia and extending the territories under their dominion to the borders of Hungary. In the sixteenth century they became a world empire, confronting the Muslim Mamluks and Safavids, in Egypt and Iran respectively, and the Christian kings of Europe, in a broad frontier zone stretching from the western Mediterranean to the Black Sea. Belgrade fell to Ottoman armies in 1521, Rhodes in 1522, and, by 1541, Sultan Süleyman I (r. 1520–66) had occupied Buda and could claim sovereignty over much of Croatia and Hungary. See Map 1. This expanding empire was the object of careful scrutiny and wild speculation in Christian Europe, its military and spiritual prowess addressed in diplomatic reports, histories, sermon literature, compendia of knowledge, plays, essays, murals, broadsheets, and maps, among other forms of communication.

In the Christian kingdoms of Europe the Ottomans were presented as descendants of the “Scythians,” the same “Turks” who swept out of Central Asia and confronted the “Saracens” in the crusading era.Footnote 3 The “Turks” (a generic designation used to connote the Muslims in Ottoman territory) were then mingled with all the historic Islamic ‘marauders‘ who had tested and trampled the borders of “Christendom.”Footnote 4 A parade of witnesses passed among the capitals of the Mediterranean world, circulating information about the Ottomans, their society, personnel, customs, beliefs, institutions, texts, identities, and material culture. The audiences for that information ranged from statesmen to merchants, and from scholars to illiterate parishioners, from the readers of cheap broadsheets to the consumers of lavish atlases (see Ch. 2). There was enormous demand for images and knowledge of “the Turks,” whose successes, coinciding with the Renaissance and Reformation, were believed both to exemplify the effectiveness of a brutal, Islamic ‘slave state’ and to signal the wrath of an angry Christian God, perhaps even heralding the advent of the Last Days. For some observers, the Ottomans, with their ferocious gunpowder infantry, were poised to overrun Europe; for others, they were temporary squatters on classical and sacred space, the redemption of which awaited only the will and unity of the monarchs of Christendom.Footnote 5 Still others saw the rich and successful empire as a land of opportunity, a potential wellspring for products, patronage, and power. These varying perspectives are reflected in the texts and imagery of the time (roughly the mid sixteenth to the later eighteenth century), complicating and lending nuance to the enduring message of the Ottomans as a threat to Christendom.

Methodology, Historiography, and Objectives

The Ottomans, as an element of the historiography of early modern Europe, often appear in two standard forms: the “empire,” a continent-spanning but rather amorphous imperial entity that functioned as a military great power; and the “Turks,” an embodied plurality that “threatened Christendom,” but was ultimately domesticated, exoticized, and dominated by an ascendant Europe as the early modern era came to an end. What the Ottomans did to or with early modern Europe has traditionally been couched in terms of the words “impact” and “difference”; and those terms are a logical outcome of the language of early modern texts. Indeed, Ottoman rhetorics of power and sovereignty, like those of their imperial predecessors and European Christian rivals, highlighted difference and military supremacy. But if we turn to the ways in which the Ottomans and their neighbors in “Christendom” visualized and designated space, then we find a rather more complex picture, one that included permeable borders, overlapping interests, and shared societies.

The historiographic literature on both the Ottoman empire and Christian Europe's reception of the “Turk” has become increasingly rich in recent years through the contributions of Ottomanist historians and scholars of European history, literature, and art.Footnote 6 So, too, considerable interest has been generated on the question of Ottomans on the map, a field that for a long time was limited to the pioneering works of Tom Goodrich, Svat Soucek, and a few others.Footnote 7 The publication of J. B. Harley and David Woodward's magisterial History of Cartography (hereafter HOC), along with the staging of cartographic exhibitions such as the 2008 “European Cartographers and the Ottoman World, 1500–1750” at the Oriental Institute in Chicago, have provided textual and visual inspiration on this theme to a wide audience.Footnote 8 Nonetheless, much of the work currently available on representations of the “Turk” still tends to proceed in well-defined channels (from a focus in cartographic studies on Piri Reis and major European mapmakers on one hand, to the examination of select travel accounts, diplomatic reports, or ‘national’ dramas on the other). Thus there remains much to be said regarding the ways in which those residing in the Christian kingdoms of Europe imagined, narrated, and visualized the Ottomans, their sovereignty, and the spaces they possessed.

This work attempts one segment of that larger project. It traces out some of the historical and literary sources for representations of the Ottomans, plotting the dissemination of visions of the “Turk” and perusing the complex matrix of borders, interactions, and identities through which European audiences visualized Ottoman territory. It delineates specific categories (war space, historical space, travel space, and sacred space) employed to inscribe the Ottoman empire on maps. It also presents the iconography of the “Turk” as displayed on maps, an iconography that painted the Ottomans, alternately and in combination, as commercial partners, epic warriors, and objects of ethnographic scrutiny, as well as marauding barbarians, heretics, and harbingers of the Antichrist. This study devotes particular attention to the image/text interface (that is, the relationship between images and the texts with which they were associated). That interface is especially important because early modern maps derived their characterizations of Ottoman space from the rhetorics and imagery of texts, and because maps often involve an intricate layering (or collage) of text and image derived from other works.Footnote 9 Just as there was no definitive border between Europe and Asia, or Islam and Christendom, in this era, so too there was no definitive boundary between the map itself and the texts that surrounded, inspired, or were inscribed upon it. Further, this book contributes to the burgeoning literature on ‘Eastern’ travel. As mapmakers enclosed the land and seascapes of the Ottomans within the map frame, they displayed early modern notions of space measured in terms of cities, fortresses, pilgrimage sites, provisioning stations, and accessible or inaccessible routes. Mapping was thus intimately connected to travel, both actual and imaginary. It had its own logics of possession, movement, and frontiers. The traveler, along with the diplomat and other types of intermediaries, was the eyewitness, the authority invoked by the mapmaker to legitimate his vision of space. Finally, this book, as it examines the diffusion of images of the Ottomans, their sovereignty, their mores, and their armies, adds to the growing historiography on the circulation of knowledge and the translation of culture in the early modern Eurasian world.

It is also important here to state what this book does not do. I am a historian of the intersections between the Ottoman world and surrounding territories; I am neither a cartographer nor an art historian. Thus it is not my intention here to trace the evolution of maps of Ottoman territory or the technical details of map production and artistry. Those tasks have been accomplished or are being accomplished by experts elsewhere, in the History of Cartography and in the journal Imago Mundi, among other sources. Rather than sorting out the direction of cartographic influences, or precedence in discoveries of mapping technology, what I want to know is how mapmakers in different places embodied and circulated ideas of the Ottomans and Ottoman space, and what their images might tell us about their milieu, their audiences, and things such as state power, historic memory, identity, worldview, borders, the visualization of land and sea, and the exigencies of getting from place to place.Footnote 10

The early modern era was indeed a time when the technologies of charting, engraving, and depicting the world's spaces were evolving and improving. But technological capability and scientific knowledge were only two factors in the complex intellectual, political, economic, historical, and pictorial process that was mapping.Footnote 11 Early modern maps, like the texts from which they derive, do not follow a strict evolutionary pattern in depicting the Ottomans and their empire; they are, rather, the products of tropes of narration and conventions of representation, the technical constraints of printmaking, and the knowledge, education, imagination, and demands of a consuming public that is notoriously difficult to pin down, except anecdotally. Most of all, I want to know what Ottoman space looked like to that public. In seeking that objective, I focus on the map itself and its narrative contexts to demonstrate the ongoing tensions over truth-claims and illustrate some of the ways in which Ottoman space was experienced and constructed. The tales of individual narrators do not, of course, substitute for a close examination of each one of the numerous interpretative communities affected by these maps: how they accepted, misunderstood, acted on, or ignored the messages of the map. But it may be hoped that the traveler witnesses employed here will speak in some small way for their own reading communities, whereas I leave the project of assessing audience reception in specific communities to other scholars.

Neither do I propose to trace out the extent of geographic knowledge in the Ottoman world or to present in any comprehensive way the literary and historical contexts out of which mapped images of the Ottomans emerged. A database of cartographic literary allusions grouped by time and region would be a wonderful thing; but it is beyond my capabilities. What I hope to accomplish, rather, is a comparative commentary on the modes and types of representation of Ottoman space deriving from some of the Christian kingdoms of Europe. I place before the reader an array of mappings of the Ottomans (particularly those spaces on the European ‘side’ of the empire) in hopes that they will provoke discussion and refine and expand our sense of the ways in which the Ottomans were imagined and imagined themselves. This material is purposefully selected to range widely, unconstrained by strict chronology or ‘national’ designation. It crosses genres to present a mix of imagery of the “Turk,” similar, perhaps, to that an educated reader might be exposed to. I hope thereby to illustrate the ways in which the map layered historical time and manipulated space, suggest those forms of representation that were enduring and those that were exceptional, and, further, propose that the mappings of the sixteenth and eighteenth century worlds were not as dramatically different as they might sometimes seem.Footnote 12

This volume is divided into three parts comprising seven chapters plus an afterword. Part One (Chapters 1 and 2) sets the stage by addressing methodology, approach to space and time, categories of analysis, genres of mapping the “Turk,” and the processes by which the Ottomans were made familiar to audiences in the Christian kingdoms of Europe. This first chapter serves as an introduction. It suggests a set of categories by which Ottoman space was understood and introduces some of the possibilities for comparisons to Ottoman self-mapping. It emphasizes the ways in which time and space were collapsed on early modern maps in order to convey political and cultural messages of entitlement and identity. Chapter 2, on “Reading and Placing the ‘Turk,’” introduces some of the genres employed for mapping the Ottomans and speaks (through a set of illustrative examples) about the ways the Ottomans were represented and translated into text and image. It also addresses questions of the circulation of knowledge. Part Two (Chapters 3, 4, and 5) presents the mapping of Ottoman space in terms of borders, fortresses, and the iconography of triumph and submission. Chapter 3 is divided into three sections, which address conceptions of the ends of empire; the transimperial borders among the Ottoman, Hapsburg, and Venetian empires; and, finally, the roles played by Constantinople and the Holy Land as annexes of Europe and focal points for prophecy in mapping the division of “Christian” and “Turk” space. Chapter 4 examines the fortress (inland and coastal) as the quintessential marker of space and sovereignty, employing examples concentrated in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. The fortress was the centerpiece of possessed space and of the competition for hegemony in the transimperial zone linking the Ottoman, Venetian, and Hapsburg empires. Chapter 5 continues the examination of conflict imagery in historical texts and map imagery. Possession was counted not only in fortresses but also in images of the conquered foe, his head, his body, his arms, and his symbols. The fallen Turk, deployed on the map, delivered a powerful message of ownership. Part Three (Chapters 6 and 7) elaborates on the literatures and imagery of travel along with the various authorities invoked in an attempt to demonstrate the ‘accuracy’ and ‘truth’ of mapped space. Chapter 6 presents the stages by which travelers and maps charted the movement into and out of Ottoman space. This chapter highlights the journeys from Vienna and Venice to Istanbul by land and sea and illustrates the modes and measures by which Ottoman space was counted. Chapter 7 addresses the threefold foundation of authority (knowledge, text, and eyewitness testimony), used by travelers and transposed onto the map to certify the validity of descriptions of Ottoman domains. The knowledge and texts of ‘classical’ and Biblical pasts were front and center in the imagery of the early modern era. They constituted its history and memory. In this chapter, narratives by Italian and English travelers will be featured and then juxtaposed to the well-known travel narrative of the Ottoman raconteur Evliya Çelebi.Footnote 13 Additionally, in this chapter, I will use travelers' descriptions of women and their dress as a special element of claims to authority. By way of conclusion, the “Afterword” (Chapter 8) will take up some of the implications of mapping space and identity that have traced through both the volume and the historiography of Ottoman–European relations and that find resonance in both world-historical paradigms and contemporary world struggles.

Designations of Space

This work is about mapping Ottoman space. I employ the term space as an alternative to territory, because I want to suggest the Ottoman realm (conceptualized by early modern peoples) as a place imbued with attendant identities, cultures, and historical contexts, all of which could be enclosed within the map frame.Footnote 14 Ottoman space, in the European (and Ottoman) imagination, was not simply a block of territory circumscribed on a map. It was a place entangled in a set of histories and competing claims dating back to creation. It was full of peoples, faiths, languages, occupations, and cultural mores that transcended political reality, or endured as carefully preserved artifacts of cherished past lives. Further, Ottoman space was not limited to those lands where the sultan's armies could readily be deployed. It included lands claimed by the sultan. It comprised those adjacent places where the threat of Ottoman arms held (or seemed to hold) sway. Nor was it limited to terra firma, including as it did the seascapes of the Mediterranean, Aegean, Adriatic, Black, and Red Seas onto which Ottoman power was projected. The notion of Ottoman space then presumes the sultan's domains as a complex form of possession and identity, dependent not entirely on what was actually there but also on what was imagined, remembered, depicted, hoped for, and then visualized in textual and pictorial sources such as maps and travel accounts.Footnote 15

The idea of Ottoman space is complicated by terminologies of place and identity that defy the drawing of borders. The borders of Europe, in the early modern imagination, as we shall see in Chapter 3, ranged over a broad territory, despite what the continental divisions of ancient geographies or the national boundaries of contemporary atlases might suggest. Christendom and Europe on one hand, and Islam and Asia on the other, were not coincident. And finding precise terminology for designating Ottoman space in Europe is a vexed process and one with a long history. That dilemma is reflected in early modern European cartographic usage, which came to employ the designations “Turkey in Asia” and “Turkey in Europe” to suggest its own uncomfortable relationship to the cross-continental territorial holdings of the Ottoman sultans. I have used here (rather broadly) the terminology “Balkans” and “Greco-Balkan peninsula” to describe those European territories into which the Ottomans expanded and in which they operated in the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries.Footnote 16 That usage is a geographic convenience employed to avoid the repeated recitation of individual regions. But it fails to reflect the complex relationships among sovereign (or not so sovereign) lords, or among inland, coastal, and island territories. I cannot resolve these ambiguities of designation in any comprehensive way. “Europe” remains a term that designates continental space, with Constantinople as its evident eastern outpost, “before Asia.”Footnote 17 And in this study I will employ that term because it is customary and familiar to denote the location from which ‘outside’ observers in the Christian kingdoms characterized the sultan and his territories. But the Ottoman empire was as European as it was Asian; its heartland and signature province, Rumelia, lay in Europe.

Another problem of designation resides in the fact that the territories of Europe were no more entirely Christian than the territories of Anatolia or Syria or Egypt were entirely Muslim, or Turk, as European sources of the era might describe them. Ottoman sources customarily employed a we/they distinction: the “well protected domains” of the sultan as opposed to the “lands of the Christian kings.” This juxtaposition separated the empire from the polities of European enemies and allies alike without suggesting that the whole continent of Europe was somehow necessarily “Christian.” That division of space, relying on sovereignty rather than communal identity, is a useful one because it includes all those people (and readers) resident under either Ottoman rule or that of the Christian kingdoms. It takes up the enduring minorities (such as the Jews of Europe or Anatolia), that seem to be precluded in designations such as “Christendom” and “Islam,” highlighting instead the communally legitimized power structures to which majority and minority populations alike were subject.

Time/Periodization

Various scholars have tried to periodize the representational relationship of the kingdoms of Christian Europe to the Ottoman empire. Some, such as Lucette Valensi, see European authors as moving by the turn of the seventeenth century from the vision of the Terrible Turk to a rather admiring notion of the Ottoman empire as a well-organized and efficient form of government.Footnote 18 A related notion, articulated by Joan Pau Rubiés, is that the depiction of the East in the seventeenth century became more systematic, more scientific, and more “secular.”Footnote 19 Other commentators, such as Mustafa Soykut, argue that the Ottomans were domesticated in the European imagination, particularly after the death of Sultan Süleyman I in 1566, the Christian victory at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, and the advent of the English in the Ottoman Mediterranean around 1580.Footnote 20 Conventions of representation, however, do not necessarily, or readily, transform in response to political changes, battles, or commercial developments. The ways in which the Ottomans were mapped in any period might thus have as much to do with aesthetic tastes, ideological positions, available print models, consumer demand, conventions of labeling, or modes of looking as with any given political episode or any given advances in technologies of writing, commerce, travel, or mapping. More broadly, the whole notion of the early modern as an era that anticipates the ideas, state formations, and hegemons of the nineteenth century suppresses a set of very powerful continuities that tie the sixteenth, seventeenth, and even eighteenth centuries to the long medieval era that preceded them. The ways in which the Ottomans were mapped was inevitably conditioned by the pull of the past. The English advent in the Mediterranean, for example, was important to the English, and to their competitors. But its significance has been greatly magnified by the much later ascent of that nation to the position of world seapower, and by the extensive scholarship on both the English mercantile investment in Asia and the English literary imagination of the ‘East.’Footnote 21

That said, the death of Süleyman, the Battle of Lepanto,Footnote 22 the founding of the English “Turkey” Company,Footnote 23 and cartographic innovations did all play important roles in the familiarization of Europe with the Turk. Indeed, familiarity (how it happened and what form it took) is perhaps the key concept in establishing a periodization for European representation of the Ottomans.Footnote 24 Although the Ottomans were certainly “domesticated” for European readers (or viewers) by the seventeenth century, that domestication was already well under way by 1548. And it was accomplished not simply through a rather ephemeral naval victory but through a blizzard of news and imagery that had already reached stunning proportions by 1571. In many ways the Ottomans were familiar to some European audiences long before Lepanto. That familiarity derived in part from a complex network of commercial and cultural relationships that spanned the Afro-Eurasian oikumene and predated the Ottomans.Footnote 25 It drew on the medieval constructions of the Muslim conquerors who were the Ottomans' antecedents. And it added new variants to the representational corpus as events, audience, and situation demanded and as narrative and visual modes allowed.

These demurrals are not meant to argue that there can be no logical periodization for early modern European mapping of the Ottomans. Indeed, that mapping was characterized increasingly by a movement from regional to state designation; a complementary movement to the marking of borders of various sorts; the employment of ethnographic vignettes; a willingness to recognize the sovereignty of the Ottomans on the body of the map (in addition to its acknowledgment in legend or captions); the characterization of the sultan as analogous to European Christian rulers; greater sophistication in the depiction of fortresses and troops; enhanced claims (based on increased volume of contact) to the “latest” and most “scientific” knowledge in narrating the Ottomans; and the utilization of more advanced technologies of print and measurement.Footnote 26 The mapping of Ottoman space might also be characterized as moving from what was in part a medieval pilgrim mode to a later seventeenth century connoisseur mode, although the latter did not preclude the former.Footnote 27

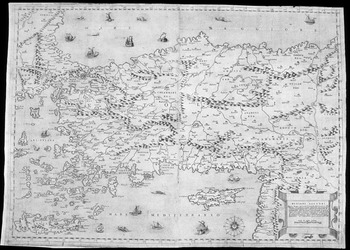

This study thus does assume a certain logic of beginning and ending points. I have chosen, somewhat arbitrarily, 1548 as a beginning date, the year in which the maps of Giacomo Gastaldi of Piedmont (fl. c. 1544–66), cosmographer of the Venetian republic, were published in a new and revised edition of Ptolemy's geography.Footnote 28 Gastaldi was a notable figure in the production of cartographic visions of the Ottoman world. And Venice was (as Levantine commercial emporium and translator par excellence of things Ottoman to the rest of Europe) the preeminent center for the circulation of such visions. Although it is clear that the evolution of mapping was a slow and intricate process, it is also the case that the second half of the sixteenth century was a time in which the mapping of Ottoman space geared up and the circulation of images of the Ottomans flourished in tandem with the expansion of both the empire and print.

As for an end point, Napoleon's 1798 invasion of Egypt and the European project of translating the East that it helped launch are often employed as a fitting beginning for both the “modern” Middle East and the “modern” consumption in Europe of knowledge about the “Orient.” But the production of the monumental Description de l'Egypte (published in 1809) may well be a more suitable transition point for the history of mapping than Napoleon's invasion is for a new era of Middle Eastern political history. Closer to the center of Ottoman power, the treaty of Küçük Kaynarca signaling Russia's victory in the 1768–74 Russo–Ottoman war and the reform period of sultan Selim III (r. 1789–1807) have also been employed to map modernity onto Ottoman space.Footnote 29 Nonetheless, I have chosen a rather different theater of mapping and war for my end point: the Ottoman conflicts with Austria (1788–91) under Joseph II and Russia (1787–92) under Catherine the Great. That great transimperial struggle, with its battlegrounds at Danube and Dniester, its transcontinental implications, and its backdrop the paroxysm of the French Revolution, provoked a surge of cartographic endeavor in Christian Europe on the scope of war and the necessity of new constructions of the “world.” The “new” and the “news” were always an important element of the articulation of early modern mapping, as we shall see; but the decade of the 1780s produced its own variations on that consciousness.Footnote 30 And the war was one, as Karl Roider puts it, in which “there was hardly a hint of the old cry of gathering the Christians to strike the Moslems.”Footnote 31

Even so, the cartographic visions of the later eighteenth century, despite their claims to novelty and a clearer sense of the expansive nature of the world and its cultures, did not disown the past. Between 1783 and 1790, Thomas Stackhouse, in London, published four editions of his New Universal Atlas:

consisting of a complete set of maps, elegantly engraved and colored, peculiarly adapted to illustrate and explain ancient and modern geography; in which the ancient and present divisions, as also the subdivisions, of countries and various names of places, are exhibited to the eye at one view, distinctly and correctly, on opposite pages, the several parts of the earth, which were originally peopled by the descendants of Noah, pointed out expressly, and the geography of the Old and New Testaments rendered clear and perspicuous The Whole Being Particularly Suited to Facilitate the Study of Geography; To make that Science more generally known; and thereby the Knowledge of History, both Ancient and Modern, much more useful, instructive, and pleasant.Footnote 32

Those who wished to study and perfect history and geography needed to see the living traditions of the ancient and the Biblical stamped onto the expansive territories of the globe. Thus Stackhouse used ancient divisions and peoples, along with colored maps, to illuminate the current situation of the world. In that regard, his atlas echoed the new Venetian edition of Ptolemy that appeared in 1548.

Proclaiming itself “truly no less useful than necessary,” that 1548 edition included “the usual antique and modern” plates, but boasted the addition of “an infinite number of modern names, of cities, provinces, castles, and other places, accomplished with the greatest diligence by the aforementioned Mr. Giacomo Gastaldi.”Footnote 33 The modern was thus an adaptation of the ancient for both Gastaldi and Stackhouse, not a replacement. The true, the accurate, and the unusual constituted the rhetorical foundations for claims to the customer's attention and money, whereas “divisions,” “names,” “cities,” and “castles” were the irreplaceable components of the mapmaker's art.

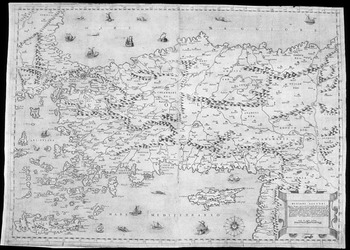

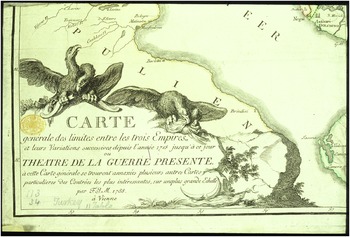

Thus, 1548 and the 1780s seem fitting temporal brackets for our consideration of the cartographic vision of early modern Ottoman space. And a fitting counterpart to Gastaldi's new map of Anatolia (presented as a transnational region rather than Ottoman sovereign territory) might be F.I. Maire's 1788 “Carte générale des Limites entre les trois Empires,” a Viennese map that demonstrated the expansive boundaries of war and the diminishing power of the Ottomans in the transimperial space (Figs. 1.1 and 1.2).Footnote 34 Maire's map traces the changes in imperial borders and power from the 1718 Treaty of Passarowitz (a major juncture in the Ottomans' struggle for supremacy with Hapsburg Austria) to the combat of the “present war.” It provides an example of the complex and technical sorting out of imperial space and of eighteenth-century attempts to fix ‘national’ boundaries. But its modern, scientific qualities do not preclude its recycling the iconographies of the past. The sultans, after all, remained the self-described successors of Alexander and of the Byzantines.Footnote 35 They had conquered the “Holy Land” and “Rome.” Maire's cartouche thus showed the Hapsburg eagles tearing apart the empire's turban and breaking its bow, to leave no doubt who represented the new Rome.

Figure 1.1. Giacomo Gastaldi, “Natolia,” Venetia [1564, 1566].

Figure 1.2. F.I. Maire, “Carte générale des Limites entre les trois Empires et leurs variations successives depuis l'année 1718 jusqu'à ce jour, ou Théâtre de la Guerre présente,” cartouche, Vienna, 1788.

Layers of History

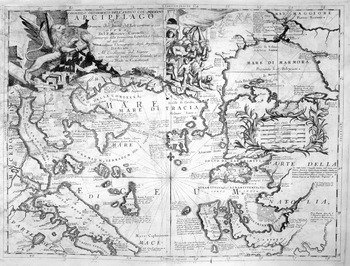

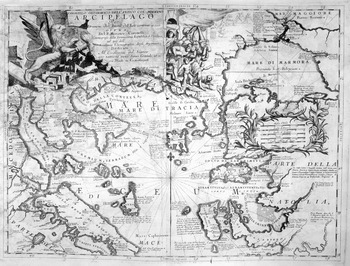

Early modern maps displayed space through a process of selecting from among available associations with the present or with proximate and distant pasts. Thus Ottoman cities, throughout our period, were mapped both as the sites of current events and as the cities of the Greeks and Latins, of Strabo, Pliny, and Mela, the “ancient auctoritates,” as Roger Chartier has noted, who were “continually cited and tirelessly commented upon.”Footnote 36 The layers of the past also certified imperial claims to territory. The Venetian cartographer Vincenzo Coronelli (1650–1718), for example, charted the space stretching from Negroponte to Constantinople in a 1696 map entitled “Parallello Geographico Dell'Antico Col Moderno Archipelago” (Figs. 1.3 and 1.4).Footnote 37 The legend tells us that the map is intended for “instruction” in the history of the islands of the Archipelago. Constantinople is marked with a list of historical “owners”: Constantine, the Latins, Venice and France in 1204, and the “Turks” in 1453. It was not ‘national’ borders that were important here; rather it was a vision of expansive space, ultimate victory, and the layers of memory to which the Archipelago was inevitably attached.Footnote 38 History, as Coronelli tells his readers in another context, is explained through the “collation of memories, both antique and modern.”Footnote 39 And what better place to see that collation than on a map?Footnote 40

Figure 1.3. Vincenzo Coronelli, “Parallello Geographico Dell'Antico Col Moderno Archipelago,” Isolario [dell' Atlante Veneto], v. 1, Venetia, 1696.

Figure 1.4. Vincenzo Coronelli, “Parallello Geographico Dell'Antico Col Moderno Archipelago,” detail, Isolario [del Atlante Veneto], v. 1, Venetia, 1696.

Coronelli dedicated this particular map of the Archipelago to Giovanni Battista Dona, the Venetian bailo of Constantinople (resident ambassador and chief intermediary between the Venetian Signoria and the Ottoman Porte). It later appeared in an atlas of “the celebrated emporium of Venice,” which was dedicated to the Holy Roman emperor Leopold I (r. 1658–1705), thus illustrating the transimperial options for patronage available to accomplished cartographers. In the atlas's dedication, the author imagines the Ottoman monarchy felled by the heavy blows of the emperor's sword. Having despoiled Asia, Africa, and Europe, and terrorized the West, the Ottomans, Coronelli suggested, would be subordinated to the “superior faith” of the emperor and his forces, who would restore to Christianity “all good things.”Footnote 41 This claiming of the Archipelago as Christian space was impressed on the consciousness of the reader, not through physical lines but through a narrative of historical entitlement. The map harked back, as one Italian treatise in 1590 put it, to the imperial glories of the “ancient states already possessed in Asia and in Europe,” which had to be “recovered for Christianity.”Footnote 42

And lest there be any doubt about the ‘proper’ associations for the Archipelago, history was inscribed onto Coronelli's seas through an elaborate system of legends on the body of the map. On the European side of the Straits of Gallipoli, a small text notes that it was in these waters that the Venetian commander Pietro “Loredano took from the Turks 6 galere and 21 fuste in 1416.” And in the Aegean, northwest of the island of Stalimene, the sea is inscribed, “It is believed that here was the Island Crise [Chryse] later submerged under the waves; on which Filottete [Philoctetes] was stung by a serpent.” The Archipelago of the present, with its Venetian–Ottoman struggle for supremacy, was thus rooted in the Archipelago of myth and history. So the mapmaker's waves restored Philoctetes and Chryse to the surface of the map. Coronelli was a scholar who prided himself on searching out the most up-to-date sources for his cartographic productions. But that inclination, even in the later seventeenth century, was never detached from the inclination to keep the past close at hand. The accuracy of his coasts was not more important to his audiences than the sense of place and attributions of “divine” right that his maps embodied.

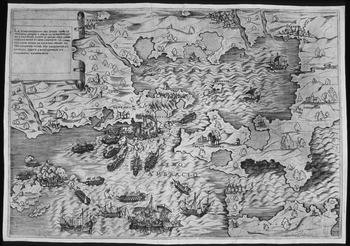

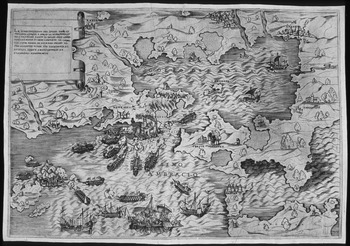

Various other artifacts suggest the role of the past in imagining the place of the Ottoman Turks in the ‘Western’ historic and geographic imagination. An unsigned mid-sixteenth century map, for example, shows a sea-based attack on a fortified port. This is the 1538 battle of Prevesa at the mouth of the Gulf of Artha on the western shore of the Greek peninsula. There the Ottomans, fighting for control of the Ionian islands, successfully battled a combined Christian fleet under the Genoese admiral Andrea Doria. The legend, in Italian, highlights what David Woodward calls the “storytelling role” of the map.Footnote 43 It informs the reader that this is the place where “at present one finds the navy of [Hayrettin] Barbarossa and that of the Christians” (Fig. 1.5).Footnote 44 Cannons roar and naked men leap from a burning ship into the water. The viewer can almost see the famous red-bearded Ottoman naval commander and hear the booming of the cannons. But the legend goes on to situate the map not only in the events of the time but also in the historic memory of its readers, showing these consumers where and how this space was important. This is the place, it reads, “called the Gulf of Artha; in ancient times it was called Ambracio da Ambra, the actual city of Pyrrhus, near the promontory of Actium where the memorable victory of Augustus over Marc Anthony and Cleopatra took place.” Marc Anthony and Cleopatra, for the viewer, thus inhabit the same space as Barbarossa (c. 1478–1546). The Ottomans in this vision are one set of fragments in the kaleidoscope of rulers, battles, and ambitions that form the knowledge-picture of the reader.Footnote 45

Figure 1.5. The Battle of Prevesa. Anonymous, “La dimostratione del luogo…Artha” [n.p.], [c. 1538].

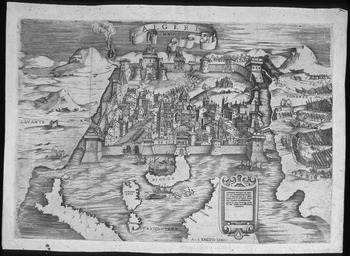

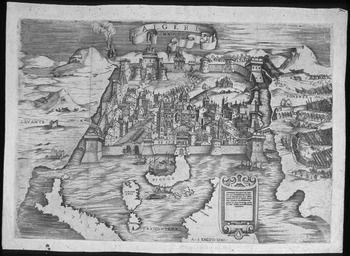

Space on the map, like time, was flexible. It had to be in order to facilitate the demands of historical consciousness and the need to see distant lands in their full measure of connectivity. In 1541 the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V (r. 1519–56), lost his fleet in an effort to take Algiers and end the threat of Barbarossa to Spanish shipping in the Mediterranean. A map produced that same year visualizes the port-fortress of Algiers as lying in the back yard of Italy and Spain (Fig. 1.6).Footnote 46 The author notes this conscious distortion of space in the map's legend; it is a distortion that suggests a relationship. Algiers was a site where the history of Europe was being made. It was a site the emperor wanted to draw into the power sphere of the Hapsburgs. And it was a site of encounter with the “Turk,” whose military successes mirrored those of Rome and confounded the continental division of the Christian and Islamic worlds. So the mapmaker drew Algiers in toward the coasts of Europe, demonstrating its potential for conquest by one ‘side’ or the other.

Figure 1.6. A. S. [Antonio Salamanca], “Algeri,” [Rome], 1541.

Maps such as this one, even when detached from their written contexts, are inextricably linked to an enormous corpus of literature.Footnote 47 They flow naturally from texts and bend the visual conceptualizations of place to replicate the lines and distortions of narrative. Thus Algiers may be approximated to Sicily; or Vienna and Istanbul may be placed in the same horizontal plane so that viewers can better imagine the journey. Each map reveals the avenues by which European publics grasped and ‘consumed’ the Ottomans and their empire. The readers' universe of knowledge might stand unmentioned in the background of the map or it might take the form of elaborate textual explanations: for example, the transcriptions with iconographic and allegorical commentary that Coronelli produced for the six hundred textual cartouches on his terrestrial globe, or the “instructions and rationales” for their maps that Claude (1644–1720) and Guillaume (1675–1726) de l'Isle put forth in the Journal des Sçavans, a publication of the French Académie Royale des Sciences.Footnote 48 Even if the text on the body of the map was limited to a handful of place names, a whole universe of text and subtext was close at hand.Footnote 49 The image could not escape it.

Space Classified: Historical Space, Travel Space, War Space, Sacred Space

Whether maps were inscribed with texts, embedded in texts, or detached from texts, they routinely conveyed impressions of history, travel, war, and the sacred. Those four categories were the primary and entangled prisms through which observers portrayed Ottoman space. History, as we have seen, served as an organizing principle for the reader's vision of the world. It was layered on the map like a set of transparencies placed one on top of the other. Travel was also a narrative mode that translated very directly onto the map. Although many maps presented space as static, many others indicated movement, the stages by which a traveler traced his or her way from one place to another. Many map legends cited the tales of individual travelers (ranging from the classical to the contemporary) as witnesses to the conditions, peoples, and geographies of the places depicted. History and travel were thus so tightly intertwined with the project of mapping, so ubiquitous in their presence, that they cannot be treated separately. (I will address them directly in Chapters 2, 6, and 7.) War and the sacred were also important categories for mapping Ottoman space. War was mapped to embody strategy, chart events, and foster celebration. It served to certify kingly claims and establish a hierarchy of warrior states. But sacred spaces and the paths to them competed with conflict for attention on the map. As monarchs legitimized themselves through the invocation of an Abrahamic god, a crucial element of their sovereignty was the identification, possession, and protection of sacred space.

War Space

War was an old and large category in ‘traditional’ interpretations of the Ottomans. Geographical accounts of all sorts interspersed descriptions of Ottoman territory with accounts of the battles that took place there. In the European imagination, Ottoman space was war space (dar ul-harb in Ottoman parlance), including the land spaces of the Greco-Balkan peninsula and the sea spaces of the Aegean and Adriatic. Maps portrayed these two sites of conflict, focusing on the military ferocity of the Ottomans, but also on the points (ports and fortresses) where the “Christian” encountered the “Turk.” These were the critical spaces that could signify the triumph of the Ottomans and a diminution of Christendom.

Sebastian Münster (1488–1552), in his 1544 Cosmographia, explicitly admired the discipline and soldierly qualities of the Ottomans: “nothing is more marvelous,” he wrote, than their “speed in action, constancy in danger and obedience towards their empire.”Footnote 50 That textual description of marvelous order was mapped in images of the Ottomans at war. In some representations of battle space the site itself was secondary to the image of Ottoman power. Ottoman armies were thus shown marching in undesignated space, an exemplary and fearsome force. The message of such images is one of control and obedience, echoing narrative portrayals of Ottoman troops as armies of “slaves,” who would do anything to please their commanders.

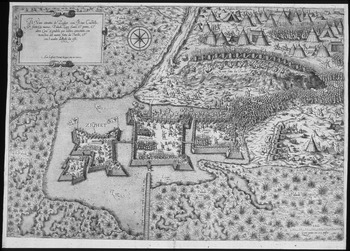

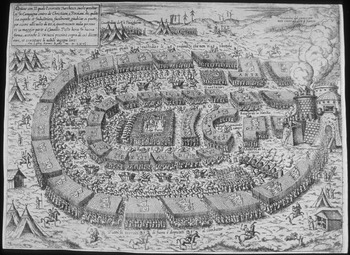

In one such undated map, Antonio Lafreri (d. 1577) depicted the Ottoman army as Sultan Süleyman led his men on his last campaign in 1566 (Fig. 1.7). The caption suggests that both Muslims on the Ottomans' eastern frontiers and Christians to the west are the potential targets of this formidable force.

Order with which the Turkish army presents itself in the field against the Christians or the Persians. So splendid and industrious is it, that it can quickly mobilize, if need be, three or four hundred thousand persons, mostly cavalry…Footnote 51

Christian observers, however, were primarily concerned with how far Ottoman armies might penetrate into Europe, and how many citadels they might attack on the way.Footnote 52 It was the mapmaker's task to show his audience that which it wished to “know and see,” no matter the frisson of fear that such an image might generate.Footnote 53

Figure 1.7. The Ottoman army. Antonio Lafreri, “Ordine con il quale l'esercito turchesco suole presentarsi in Campagna,” Rome, 1566.

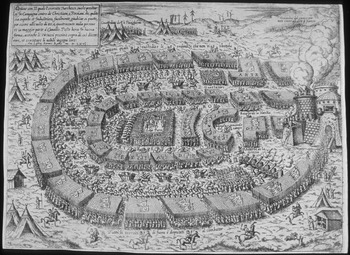

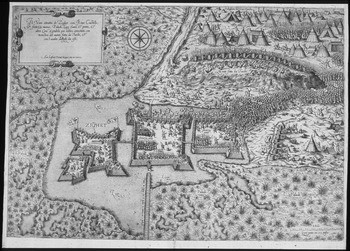

In other maps, specific place was critical to the viewer's vision of war. For example, the Ottoman siege of the Hungarian fortress of Sighetvar in 1566 galvanized the pens and brushes of Christendom. News maps invited the viewer to ‘witness’ the action. Thus the caption on another Lafreri map, printed in Rome (Fig. 1.8), reads

The true portrait of Zighet, with its castle, new fortress, marshes, lake, river, and bridge and other notable things indicated, [also] showing the “monte” (hill fortification) built by the Turks, and their assault.Footnote 54

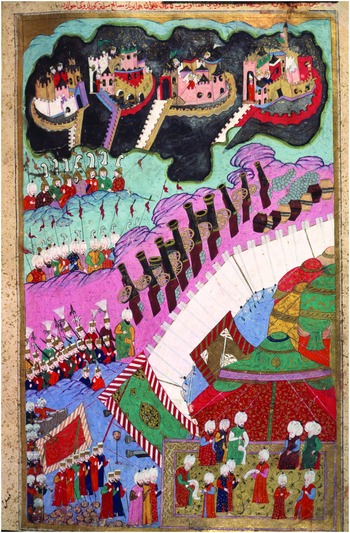

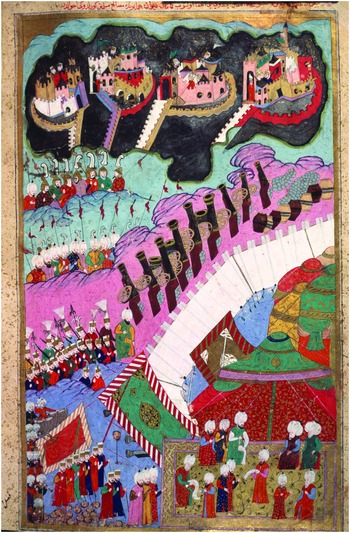

This caption attempts to remind the viewer that he or she is receiving an up-to-date and “accurate” picture of the conflict with the “Turks” and its setting. Sighetvar was a centerpiece of this vision, one fortress in a chain of military installations that defined the borders between a Christian ‘us’ and a Muslim enemy (see Ch. 4). It was also central to the Ottomans' image of war space, the siege commemorated in multiple campaign miniatures to celebrate the glory of Ottoman arms (Fig. 1.9).Footnote 55

Figure 1.8. The Siege of Sighetvar. Antonio Lafreri, “Il Vero ritratto de Zighet,” Rome, 1566.

Figure 1.9. Siege of Sighetvar. Seyyid Lokman, Hünername (Book of Accomplishments), H. 1523, İstanbul, c. 1588. Topkapı Palace Museum, İstanbul.

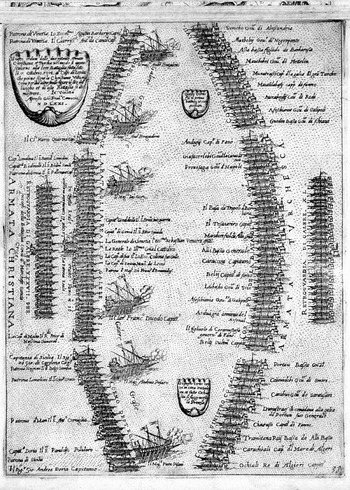

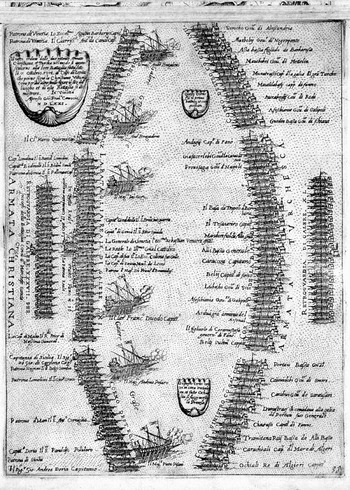

Sea battles were also a favorite subject for the artists and mapmakers of Christian Europe.Footnote 56 The battle of Lepanto, which took place in the narrow channel connecting the Gulf of Patras to the Gulf of Corinth, on October 7, 1571, resulted in a victory for the combined fleets of Venice, the Holy League, and Don Juan of Austria, arrayed against the Ottoman fleet under Grand Admiral Müezzinzade Ali Pasha. Images of that victory spread swiftly to an audience eager for good news, with Venice, one of the major print capitals of Europe, spearheading the production of those images. The Venetian mapmaker Giovanni Camocio (c. 1501–75) captioned one image of Lepanto: “The true order of the two potent armadas, Christian and Turkish, as they approached to engage in battle” (Fig. 1.10).Footnote 57 Another image (not shown here) trumpeted “the success of the miraculous victory of the armada of the Christian Holy League against that of the most powerful and vainglorious prince of the Ottomans, Sultan Selim II” (r. 1566–74).Footnote 58 That characterization of arrogance was an elemental part of late sixteenth century images of the “Turk.” His purported hubris fueled Christian hopes for his defeat, hopes that seemed to secure a divine answer in the Ottoman loss at Lepanto.Footnote 59

Figure 1.10. The Battle of Lepanto. Giovanni Camocio, “Il vero ordine delle due potente armate…(Christiana e Turchesca),” Isole famose porti, fortezze, e terre maritime sottoposto all Ser.ma Sig.ria di Venetia, map 38, Venetia [1574?].

These are conventional images: the Ottomans as a dominant military power threatening the kingdoms of the Christian kings and poised to wash over Christendom with a wave of unbelief that was temporarily turned aside by the victory at Lepanto. But images of battle and of armies on the march were only one of the multiple modes in which this enduring conflict was conceived. In both Ottoman and European mapping, war space might also be conveyed indirectly, as we shall see in later chapters, by allusion, by iconography, or via scenes of weapons, submission, and pageantry.

Sacred Space

From the point of view of Christian observers, Ottomans domains were littered with sacred sites: the birthplace of the Virgin Mary, the towns where Paul preached, and the peerless Jerusalem, center point of numerous medieval mappaemundi. The notion of a Holy Land (Terra Sancta) distorted the geographic construction of the edge of Europe and added a very particular historic layer to the mapping of Ottoman lands (see Ch. 3).Footnote 60 Some maps of Ottoman territory were produced specifically to adorn histories or geographies of ancient times. In other texts, however, temporal boundaries were purposefully blurred. The invocation of classical or Biblical space served to keep space timeless and recapture history for an early modern audience.Footnote 61 Thus, in Paolo Forlani's (fl. 1560s) map of “Europe,” the sacred figures of Christian history, moving outward from Palestine, framed European space. The journeys of the apostles Paul and Peter were described, as were the travels of Christ.Footnote 62 The Christian savior and his acolytes would thus seem to draw the lands of Europe and the gaze of the viewer toward their eastern ‘home.’ Similarly, Abraham Ortelius' (1527–98) atlas, the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, included a set of Biblical maps. Among them was a view of “Terra Chanaan” illustrating the life and travels of the patriarch Abraham, “Abrahami Patriarchae Peregrinatio et Vita.”Footnote 63 The reader could experience the trials of the patriarch, depicted in twenty-two vignettes surrounding the map. Abraham thus walked Ottoman lands along with other father-travelers who served in Ortelius' atlas as witnesses to their Judeo-Christian identity.

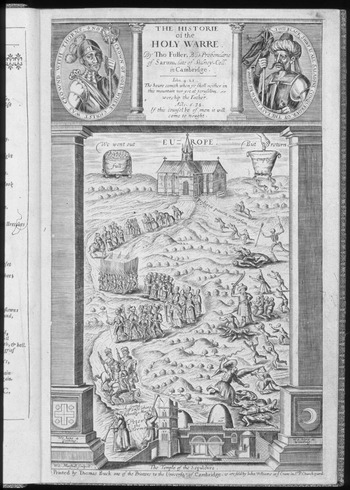

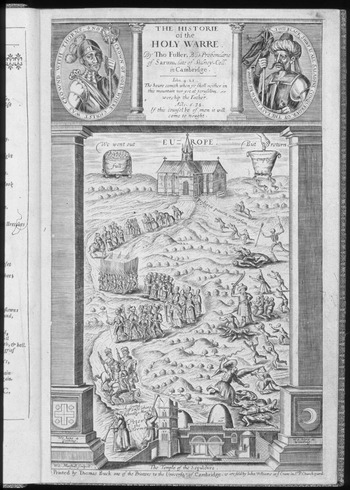

Contemporary authors also pictured themselves as joining that historical parade of pilgrim travelers. For Thomas Fuller (1608–61), an outspoken Anglican preacher, prolific writer, and supporter of Charles I in the context of the English Civil War (1642–51), the “Holy Land” embodied the identity, history, and well-being of Christendom.Footnote 64 It transcended physical possession and sovereign claims; it was God's space.Footnote 65 In Fuller's Historie of the Holy Warre, published in Oxford in 1639, the whole Mediterranean was the site of a centuries-long battle between Christian kings and “Turks,” for possession of the Holy Land. Saladin was thus a “Turk,” and his seizing of Jerusalem in 1187 stood in a direct continuum with the Ottoman conquest of that city in 1516. Christendom, the churchman advised in his Historie, must not rest until the “Turks” were expelled from the Holy Land and the Christian pilgrims again in possession of their sacred sites.Footnote 66 The frontispiece of Fuller's book serves as a map (Fig. 1.11). It compresses the journey to the Holy Land onto a single page, moving from “Europe” (depicted as the “Church”) to Jerusalem (embodied in the “Temple of the Sepulcher”).Footnote 67 On the way, pilgrims face death in the form of Turks, disease, and an avenging angel. Fuller has thus violated the constraints of space, making Jerusalem proximate to Europe, or, more particularly, to Britain.

Figure 1.11. Thomas Fuller, Historie of the Holy Warre, frontispiece, Oxford, 1639.

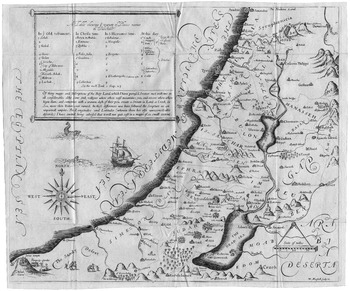

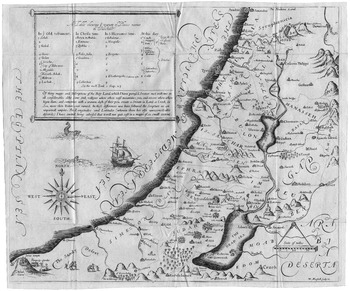

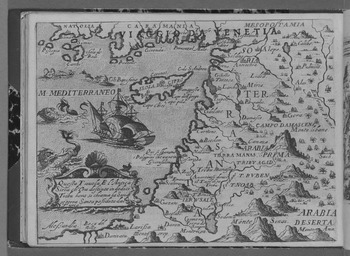

Inside Fuller's history, one also finds a map depicting Palestine and the eastern end of the Mediterranean (Fig. 1.12). The legend provides place names in terms of four layers of time – Old Testament, Christ's Time, Saint Jerome's Time, and “At This Day” – each layer crafted by the dictates of religion that the clergyman thought most pertinent to his readers. That offering of multiple time frames was echoed in other maps of the Holy Land as well. Giuseppe Rosaccio (c. 1530–c. 1620), for example, offered his readers two ‘time zones’ in a map of Syria included in his 1598 travel book: “this plate is the Antique Siria divided into twelve tribes, now called Soria and Holy Land (terra Santa), [and] possessed by the Turk” (Fig. 1.13).Footnote 68

Figure 1.12. Thomas Fuller, “A Table showing ye variety of Places names in Palestine,” Historie of the Holy Warre, plate between pp. 38 and 39, Oxford, 1639.

Figure 1.13. Giuseppe Rosaccio, “Antica Siria,” Viaggio da Venetia a Costantinopoli, 52v, Venetia, 1598.

Drawing sacred space, however, was not without its pitfalls. Under the name-legend of his Palestine map, Fuller provides some insight on the logistics of early modern mapping and the conflicted geographical visions of his own time and place.

Of thirty maps and Descriptions of the Holy Land which I have perused, I never met with two in all considerables alike. Some sink valleys where others raise mountains; yea, end rivers where others begin them; and sometimes with a wanton dash of their pen, create a Stream in Land, a Creek in Sea, more than Nature ever owned. In these differences we have followed the Scripture as an unpartiall umpire. The Longitudes and Latitudes (wherein there be also unreconcileable discords) I have omitted, being advised that it will not quit cost in a map of so small extent.

The preacher thus invoked truth claims of a rather different sort than those employed in the news maps that reported the Ottoman–Hapsburg or Ottoman–Venetian wars. His were based neither on claims of eyewitness accuracy nor on the authority of scientific measurement. Rather “Scripture” had the final word on the form and limits of Palestine. And where the science of latitude and longitude was concerned, the purse of the publisher was the determining factor, science giving way to the dictates of cost and demand (not to mention the license of the king).

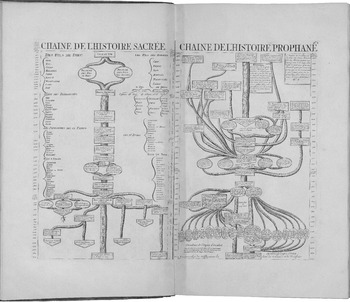

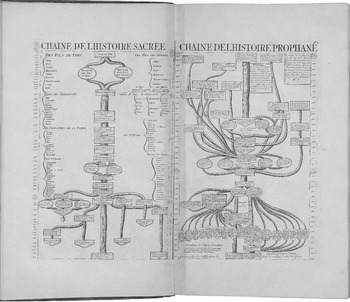

Like Jerusalem, Constantinople served as a sacred site, a royal capital suspended between Europe and Asia in which the histories of empire and faith were inextricably intertwined. This eastern “Rome” complicated Christian efforts to form discrete dominions of the sacred and profane.Footnote 69 Thus the front matter of the third edition of Henri Chatelain's (1684–1743), Atlas Historique, ou Nouvelle Introduction à l'Histoire, traces sacred history from Adam and Eve, to Jesus Christ, to Clement XI, “245th Pontiff,” in 1713 (Fig. 1.14).Footnote 70 Profane history begins with the first universal monarchy founded by the Assyrians and ends with two major imperial strands. The first (Oriental) strand traces through the Byzantines and Mehmet II (second r. 1451–1481), conqueror of Constantinople in 1453, to the contemporary Ottoman Sultan Ahmet III (r. 1703–30). The other (Occidental) strand traces through the Western Roman Emperor, Honorius, in 395, and Charlemagne (d. 814), and ends with the “German” empire under Charles V. The sacred and the profane (or imperial) are positioned side by side, but the East had to be separated from the West to preserve the strand of the “sacred” for Latin Christendom.

Figure 1.14. Henri Chatelain, “Chaine de l'Histoire Sacrée,” “Chaine de l'Histoire Prophane,” Atlas Historique, ou Nouvelle Introduction à l'Histoire…, 3rd ed., v. 1, pl. 3, Amsterdam, 1739.

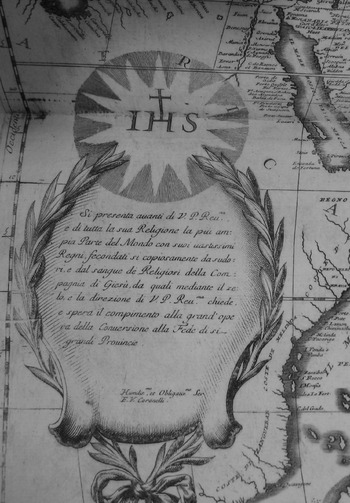

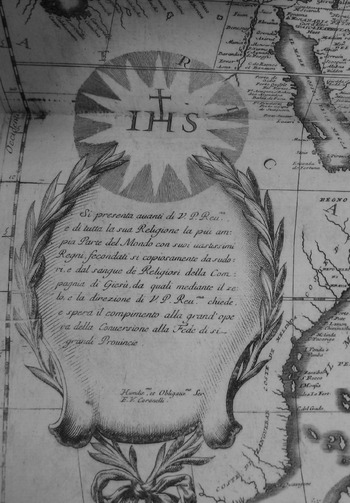

It was, however, difficult to extricate the Ottoman East from the Christian West. Vincenzo Coronelli marked his map of “Asia divided in its parts” as sacred space. The map was inscribed with a large cartouche bearing the Christogram “IHS.” It described Asia as “the biggest part of the world with its vast kingdoms…copiously fertilized by the sweat and the blood of the Religious of the Company of Jesuits.” It was they who sought “the grand work of the conversion to the Faith of such a great land” (Fig. 1.15).Footnote 71 Asia was thus not simply an eastern space, or the site of the Holy Land, or a place of Muslim enemies and competitors. It was a space made sacred for Christendom by blood sacrifice and the weight of history.

Figure 1.15. Vincenzo Coronelli, “Asia, divisa nelle sue Parti,” cartouche, Atlante Veneto, v. 1, Venetia, 1690.

Ottoman Self-Mapping

The Ottomans mapped themselves with many of the same intentions and devices employed by the authors and illustrators of the Christian kingdoms. History, travel, war, and the sacred were all prisms through which they conceptualized sovereign space. Istanbul had a long history of cosmopolitanism as an imperial center. It should therefore come as no surprise that its narrative, artistic, and technological influences were diverse and commingled, including the traditions of the East, the West, and everything in between.Footnote 72 As a center of learning and patronage, the city, with its notables and scholars, participated in an enduring and transcontinental process of cultural production and transmission. Geographic knowledge (derived from Arabic, Persian, Byzantine, and Italian traditions, among others) was part of that process.Footnote 73 Mehmet the Conqueror's interest in geography is well known; and geographic treatises are found in the libraries of the Ottoman military–administrative (askeri) and clerical (ulema) classes.Footnote 74 The renowned world map of Piri Reis (c. 1470–1554) and his Book of the Sea (Kitab-ı Bahriye) are notable examples of Ottoman cartographic arts.Footnote 75 Evliya Çelebi (1611–82), the famous Ottoman traveler, mentions in his Book of Travels (Seyahatname) that there were eight map ateliers in his time in Istanbul, whose mapmakers were versed in multiple languages, including Latin, so that they could read geographical works.Footnote 76 It is useful then to think of the Ottomans as active participants in a cartographic European Republic of Letters (and images).Footnote 77 We have only a limited number of Ottoman maps surviving (or accessible) from the late fifteenth to the seventeenth century.Footnote 78 They do not begin to approach the scale of mappings deriving from the print houses of Christian Europe. Nonetheless, as Ahmet Karamustafa asserts, “the quality and diversity of extant premodern Ottoman maps certainly suggest that there was a significant and continuous level of cartographic consciousness in certain segments of premodern Ottoman high culture…”Footnote 79 Also, our knowledge of Ottoman mapping in multiple formats is expanding all the time.Footnote 80 So our default assumption must be that the early modern Ottomans were (at least) cartographically opportunistic. As Gottfried Hagen puts it, the Ottoman “world-picture” was neither static, consistent, or “dogmatically exclusive.”Footnote 81 Ottoman mapping cannot, therefore, be delineated as simply unique, “Oriental,” or isolated from its surrounding cartographic contexts.Footnote 82

There is no clear line between “European” mapping of the Ottomans and Ottoman self-mapping. Both emerge out of an older set of transnational, transimperial, and transcontinental cartographic, literary, historical, religious, and artistic precedents.Footnote 83 The self-image of Ottoman rulers, like those of other imperial entities, was referential, echoing and responding to the self-images of past and present hegemons in the pagan, Islamic, and Christian realms.Footnote 84 Mehmet the Conqueror was conscious of that array of options when he claimed the title “ruler of the two seas and the two continents” in an inscription on the gate of his new palace in Istanbul.Footnote 85 His gold sultani coins of 1477–8 called him “Striker of the glittering, Master of might and victorious on land and sea.”Footnote 86 Mehmet and his successors saw themselves as participants in a long chain of powerful rulers and glorious events, capitalizing on tradition when it served their ambitions, and setting it aside when it was expedient to do so.Footnote 87 Mapping, like palaces and coinage, served their rhetorics of legitimation and intimidation and demonstrated the expansive nature of Ottoman patronage.

As we examine the ways in which the print houses of Christian Europe depicted the Ottomans and their space, I will invoke Ottoman mappings (as available) by way of comparison, in particular those appearing in text and miniatures. One might object that a miniature does not constitute a map in the same way that many of the cartographic images in this volume do. But I will, throughout, employ the broad sense of mapping, articulated by J. B. Harley, that a map is a representation of space (and a visualization aid).Footnote 88 Hence the miniatures in a campaign account serve as ‘real’ maps just as readily as do the pages of a Mercator atlas (Fig. 1.16).

Figure 1.16. Battle of Keresztes, 1596. Talikizade Mehmet Subhi, Şahname-i Sultan Mehmet III, H. 1609, fol. 50b–51a, İstanbul [c. 1596–9].

The Ottomans took the practice (already well developed in Iran and Central Asia) of “writing and illustrating world histories and manuscripts celebrating the victories of illustrious historical figures” to new heights after the mid-sixteenth century.Footnote 89 Murat III (r. 1574–95) was particularly known for his patronage of the arts of the book. And the sultans sponsored dynastic histories by the chroniclers Arifi Fethullah Çelebi (d. 1561–2), Seyyid Lokman (served 1569 to 1596–7), and others, placing fine copies of these often lavish manuscripts in the palace treasury and imperial library, or giving them as gifts.Footnote 90 Ottoman chroniclers cataloged victories and the acts of submission that accompanied them, consulting “first-hand witnesses of events” in the process.Footnote 91 And teams of painters in the sultan's nakkaşhane crafted the illustrations for commemorative campaign volumes that mapped out the stopping places on the way to the outposts of empire.Footnote 92 Their works certify sovereignty, but they also demonstrate the measuring out and envisioning of space. In the transimperial frontier linking Ottoman, Hapsburg, and Venetian powers, this counting out of victories and subordinates focuses on walled sites and the sieges and ceremonies that took place before them. There is much yet to be learned regarding the creation, patronage, and consumption of Ottoman images that depict space, borders, and imperial claims. But Emine Fetvacı has argued for the end of the sixteenth and beginning of the seventeenth century, particularly the reign of Ahmet I (r. 1603–17), as a time in which imperial iconography shifted from an emphasis on “conquering castles” to depictions of processions, the administration of justice, and prayer.Footnote 93 These are processes that lend themselves to the arts of the map.

Like their Christian counterparts in Europe, the sultans and their artists envisioned space as both historical and sacred. No sultan ever made the pilgrimage to Mecca. But Mecca, like other sites of pilgrimage, was, for Ottoman publics including the sultan, a source of curiosity, worship, longing, and patronage. In the 1582 Ottoman version of the book Jewels of Marvels: A Translation of the Sea of Wonders (Javahir-al-Gharaib Tarjomat Bahr al-Aja῾ib), by Cennabi (d. 1590), one finds an image of the Ka῾ba and its surrounding walls.Footnote 94 The same work depicts Murat III in his library in Istanbul, flanked on both sides by bookshelves, a consumer of the scholarly, the pious, and the exotic.Footnote 95 One can imagine him as an armchair traveler, like the consumers of so many maps, using the images to transport himself to distant lands: those he claimed, those he might conquer, and those he might only imagine.