Two Troy during the Archaic Period

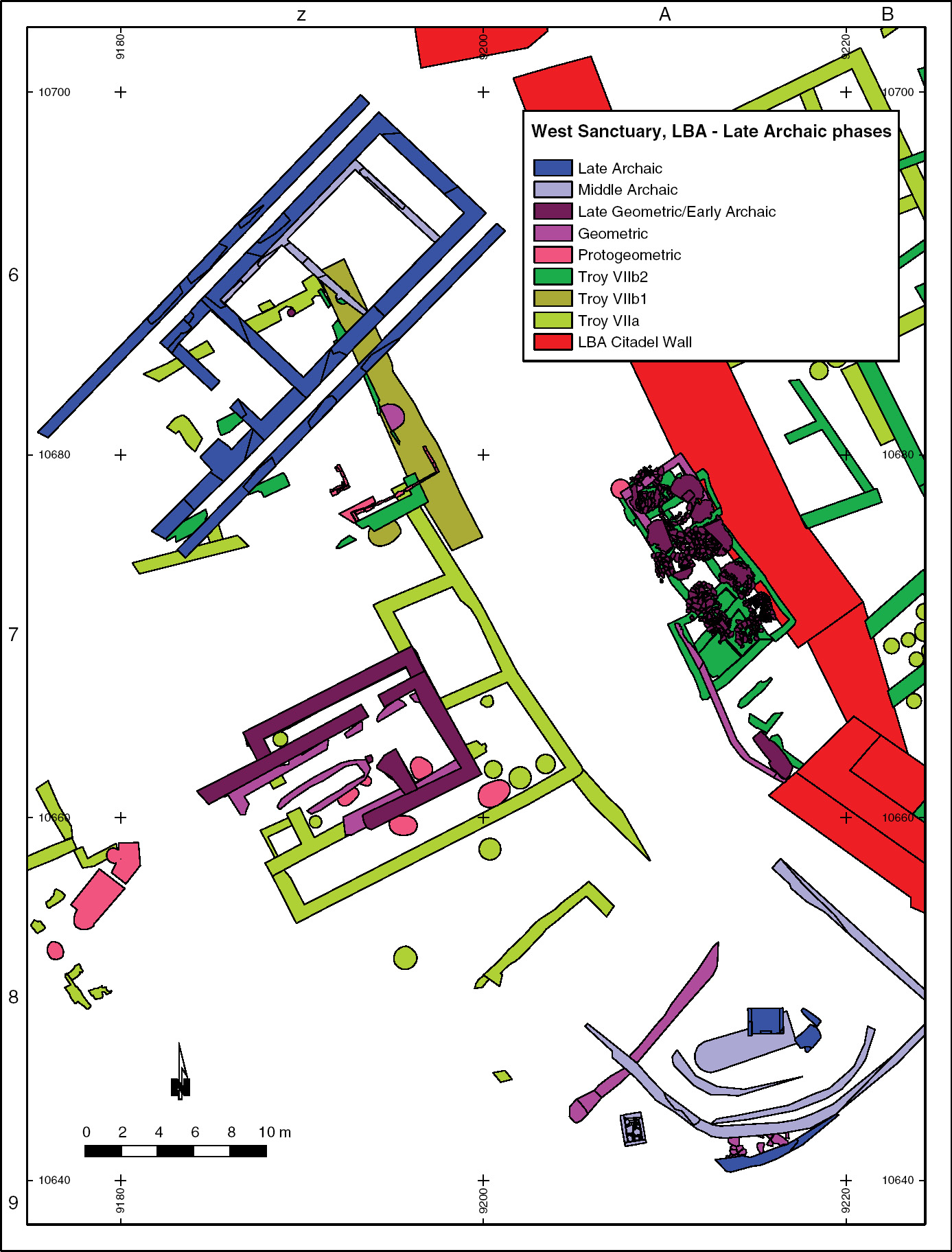

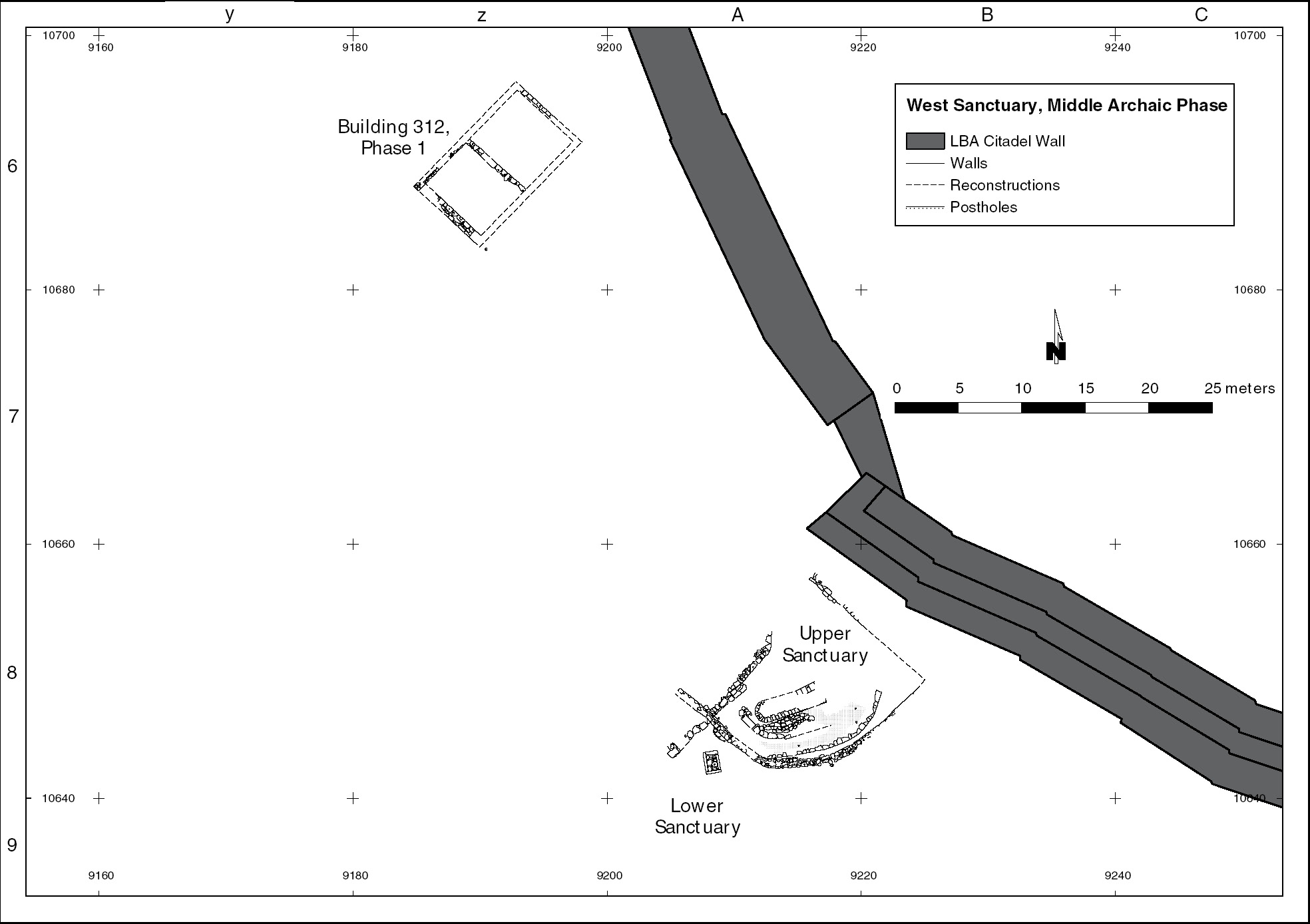

Reconstructing occupation at Troy during the first half of the first millennium B.C. has never been easy, primarily because sealed strata dating to the Iron Age and Archaic period are preserved in only a few areas of the site. Troy’s center of habitation during this period was almost certainly the citadel, but all pre-Hellenistic levels were cleared away during the construction of the Athena Sanctuary in the third century B.C., so there is no way to be certain. The only areas where substantial deposits dating to ca. 1000–500 B.C. have been found are in the northern part of the West Sanctuary and in a network of terraces on the south side of the mound (sector D9), neither of which was extensively excavated until the 1990s (Plate 8).

Since the excavations conducted in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries yielded no clear archaeological evidence for continuous habitation between the Bronze and Iron Ages, it was assumed that there must have been a long hiatus in habitation following the end of the Bronze Age. Carl Blegen argued that the hiatus extended for nearly 400 years (ca. 1100–700 B.C.), ending only with the beginning of the Archaic period, and this has long remained a dominant viewpoint in scholarship.1

When the Troy project began, our understanding of the first millennium B.C. was not so different from that of our predecessors. Manfred Korfmann and I initially assumed that the division between our respective areas of exploration would be relatively easy to determine, since deposits dating between the Late Bronze Age and the Early Hellenistic period were generally absent from every trench. By 1993, however, we realized how wrong we were, and the prospect of a long hiatus in habitation at the site seemed highly unlikely as increasing numbers of Iron Age deposits began to appear.

The pottery in those deposits clarified the commercial networks operating in the Troad during the tenth, ninth, and eighth centuries B.C., and we found ourselves in a better position to assess long-held theories of a widespread Greek colonization of the Troad during the Iron Age, usually referred to as the “Aeolian Migration.” That migration, in effect, provides the frame for this chapter. After a review of the relevant literary accounts, I present the archaeological evidence that bears on the migration’s historicity, focusing on the new Trojan discoveries of Iron Age and Archaic date but situating them in the broader context of Greek and Anatolian interaction. Such an analysis elucidates the extent to which the migration stories are borne out by the archaeological record, while simultaneously illustrating the political dimensions of Troy’s evolving Homeric identity.

There is no uniformity in the ancient sources that deal with the Aeolian Migration, but the narratives generally focus on colonists from mainland Greece who crossed the Aegean after the Trojan War and founded settlements throughout northwestern Asia Minor, including the Troad, Lesbos, and Tenedos (plate 11).2 One of the fullest accounts of the migration is provided by Strabo, who proposed that Greek immigrants departed from Aulis in Boeotia, like the forces of Agamemnon, and proceeded to Thrace, under Orestes’ son Penthilus; then to Daskyleion, under his grandson Archelaus or Echelas; and finally to the Troad and Lesbos, under his great-grandson Gras, after whom the Granicus River is named.3 As one can easily see from Strabo’s summary, the royal family of Mycenae, and especially Orestes, play a particularly prominent role in these narratives.4

Plate 11. Map of the Aegean during the Archaic Period, prepared by Gabriel Pizzorno.

This feature of early Greek history has become widely accepted, and nearly every archaeologist who has written about Troy during the last century has attempted to tie the Iron Age and Archaic discoveries at the site to the stories of the Aeolian Migration.5 Not surprisingly, this ambiguous evidence has prompted a wide variety of viewpoints on both the migration and the early phases of post–Bronze Age Troy, which means that the nature of the settlement during the period in which the Homeric epics were composed has always been elusive. A host of historical questions still remain to be answered, even with the addition of so much new and well-stratified evidence, but we are finally in a position to diagram the principal developments at the site during the first five centuries of the first millennium B.C.

The Protogeometric and Geometric Periods (VIIb3/early VIII, ca. 1050–650 B.C.)

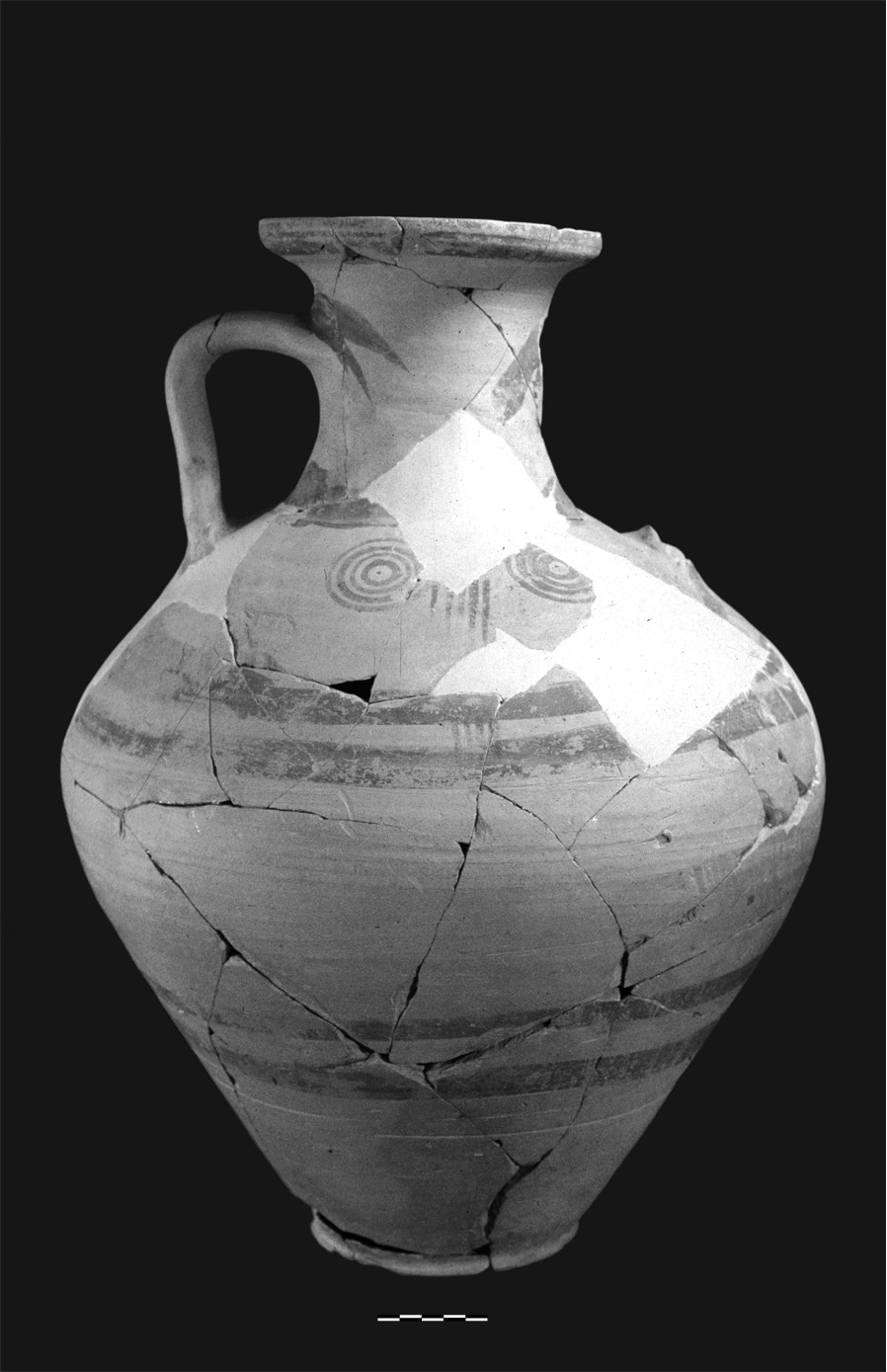

The VIIb2 phase ended with a destruction (ca. 1050 B.C.), and judging by the tumbled stones covering nearly all of the occupation areas, there may have been an earthquake.6 Most of the houses of this phase had been abandoned and cleared out before the destruction, and we have been unable to determine exactly where the survivors subsequently lived; their houses may have been cleared away by Schliemann when he removed the center of the citadel mound. It is during this post-destruction phase, often referred to as Protogeometric or VIIb3, that a new type of wheel-made pottery painted with concentric circles begins to be found, but otherwise there is no substantive change in the ceramic assemblages (Fig. 2.1).7

2.1. Protogeometric amphora from the West Sanctuary. Çanakkale Archaeological Museum.

The earliest painted Protogeometric pottery (Group 1) belongs to neck-handled amphoras, and although these sherds comprise only 3 percent of the tenth century B.C. assemblages, they have received an usual amount of attention during the last twenty years. The amphoras were originally thought to have been produced somewhere in mainland Greece – either coastal Locris or southeast Thessaly – but recent neutron activation analysis has demonstrated that virtually all of them were locally made, thereby requiring a shift in our earlier interpretations.8 Similar neck-handled amphoras, also of tenth century B.C. date and also locally made, have been found at Torone in Macedonia, and others have recently been discovered at Lemnos and Clazomenae.9 At the same time, there are discernible similarities between ceramics in the Troad and those on mainland Greece: an Early Protogeometric cup from Troy is a Gray Ware imitation of a type found in the Thessalo-Euboean area, and there are wheel-made Gray Wares in Protogeometric levels at Euboean Lefkandi that feature the same decorative schemes as those originating in Troy.10

What exactly does all of this evidence tell us about the character of the Protogeometric settlement at Troy and about the site’s role in cross-Aegean trade during that period? In spite of the lack of house walls of Protogeometric date, there must have been a settlement with functional kilns that were producing a specialized type of pottery undoubtedly intended for an equally specialized product, probably wine or oil. The settlement was clearly not an isolated one: the stylistic and technical similarities among contemporary pottery from western Asia Minor, Macedonia, and Euboea, cited above, strongly suggest that Troy was in contact with other centers of ceramic production during the tenth century B.C. There is no way of determining whether that contact was confined to the North Aegean or extended all the way to Euboea, although the limited number of potential Euboean imports at Troy may indicate that the influence was indirect rather than direct. Itinerant potters working in and moving around the North Aegean may also have played a role in the development of Troy’s new Protogeometric amphoras, but the pottery that they produced appears to have been made of local clay.11

Not surprisingly, the presence of these sherds in Troy’s Protogeometric levels has been linked to the Aeolian Migration – originally by Walter Leaf, who interpreted the pottery as a sign of Greek colonization at Troy, and more recently by Dieter Hertel, who believed that the Protogeometric sherds should be connected to the subjugation of Troy by Aeolian settlers.12 The ceramics in these levels, however, do not support such an interpretation: as I mentioned above, only one shape, the neck-handled amphora, is represented. The amphoras may have been components of an exchange system involving both sides of the Aegean, but they supply no proof of a massive migration from west to east.13

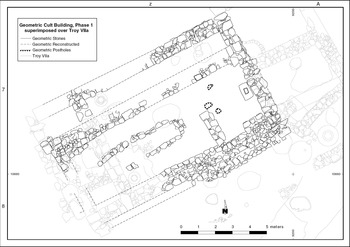

Although no new buildings can be dated to this period, there are signs of activity in and around one of the ruined structures in the West Sanctuary – the “Terrace House” (Plate 12 and Fig. 2.2).14 This building, which had been constructed in the thirteenth century B.C. (Troy VIIa), featured a large central room (9 × 6 m) with a hearth, a pithos storage area, and two smaller rooms. A wealth of small finds, probably dedications, were found inside the structure and suggest the existence of cult activity at least by the early twelfth century B.C.15

2.2. Plan of the Terrace House with apsidal altar, prepared by Pavol Hnila for the Troy Excavation Project.

Plate 12. Plan of the West Sanctuary during the Late Bronze Age and Archaic Period, prepared by Pavol Hnila for the Troy Excavation Project.

The Terrace House had been destroyed at the end of VIIa (ca. 1180 B.C.) and appears to have been unused during the following 130 years, during the VIIb phase. It would now, once again, be a locus for activity within the complex, and judging by the material in a series of pits both within and around the building, that activity was almost certainly associated with cult. The contents included burned animal bones, amphoras, large kraters and cups, cooking pots, and three fenestrated stands that must have functioned as thymiateria, or incense burners.16 In one of the pits was a nearly complete neck-handle amphora with post-firing incised signs that may relate to commerce (Fig. 2.1); another pit yielded a relatively well-preserved thymiaterion that is unique within contemporary votive assemblages: it had a height of nearly 0.33 m, and featured four zones of cross-hatched triangles above a frieze of animals (Fig. 2.3).17

2.3. Fenestrated thymiaterion from the West Sanctuary.

Based on the nature of the assemblages, it looks as if the activity in the building involved food preparation, feasting, and drinking, coupled with the burning of incense. That in itself is not surprising; what is noteworthy, however, is that the Terrace House shows no signs of repair or reconstruction dating to this time. Whatever rituals and offerings occurred there will have been conducted in the midst of a ruined building of Late Bronze Age date. It is especially striking that there was a hiatus of nearly 130 years between the two main periodsof cult activity in the building, with a new group of Thracian settlers arriving at the site midway through the hiatus. We cannot exclude the possibility that the memory of the Terrace House as a locus of sanctity was maintained during this period, and the renewed cult activity may indicate an attempt to re-engage with the Late Bronze Age settlement.

The latter proposition is rendered more likely by the discovery of a contemporary ceramic assemblage adjacent to the Troy VI citadel wall, which can be reconstructed as a small drinking set with a krater, jug, and cups.18 Here too there appears to have been ritual activity, although, again, no signs of new architecture are apparent. None of this is surprising if one looks at the broader Aegean context: the application of sanctity to a citadel destroyed or abandoned at the end of the Bronze Age can be found at Knossos, Mycenae, and Tiryns, all of which received new cult buildings in the Early Iron Age, even though the citadels per se were abandoned.19 A particularly relevant comparandum is supplied by the Iron Age settlement on the island of Kea, where a ruined Bronze Age temple continued to serve as a locus of cult activity in the eighth century B.C., with new benches and a base supporting the head of a terracotta statue of Bronze Age date.20

During the Early Geometric period, in the late ninth or early eighth century B.C., the Terrace House was rebuilt and three of the old Bronze Age walls were incorporated into the new construction.21 The old structure had featured several rooms with a central hall measuring 9 × 6 m; the new one contained one principal room (4.0 × 11.3 m) with a narrow corridor along the north side (Fig. 2.2). Situated along the central axis were a long apsidal altar and a mortised base that were separated by a wall or partition.22 The base was clearly intended for the insertion of an object related to the cult, and the size of the mortise, 0.33 × 0.22 m, suggests that the object was both large and heavy.23 The complete skeleton of a sheep or goat had been buried under a rectangular patch of stones during the construction of the mortised base, and may relate to a sacrifice at the time of the building’s dedication.24

The altar (5.6 × 1.8 m) was filled with ash and burned animal bones, primarily sheep or goat, with cattle and pig represented in smaller numbers.25 None of the altar stones showed signs of burning, which suggests that the animal bones were deposited here after the sacrifice. Offerings made in or near the altar include four bronze fibulae, two bronze rings, and a bronze spearhead.26 There is some evidence for benches or seating within the building as well as along the southern exterior side, so the cult activity was clearly communal.27

During the later Geometric period (late eighth century B.C.), we begin to find more evidence for occupation at Troy: a house with hearth and oven was constructed in front of the Troy VI fortification wall on the south side of the mound, in sector D9, and the Terrace House in the West Sanctuary was restored once again.28 This involved extending the length of the building by at least 1.4 m, reinforcing another wall, and removing the cult base at the back of the main hall, which was replaced by a line of stones that may have supported a bench.29

The apsidal altar appears to have been covered and put out of use by a higher floor level, but around the same time, ca. 700 B.C., a series of stone paved circles were constructed ca. 20 m toward the east, along the Troy VI fortification wall. Blegen found twenty-eight such circles in all, with an average diameter of 2 m, although not all of them were contemporary (Fig. 2.4).30 Some were surrounded by orthostats, and each was clearly the locus of a fire judging by the layer of black earth on top of them. The ceramic assemblages associated with these circles suggest feasting (cups, dinoi [mixing bowls], kraters, etc.), which, given the location, was probably associated with the site’s Bronze Age heritage.31 The circles were situated on a terrace, ca. 3 m high, and framed by the adjacent Troy VI fortification wall. The actual feasting, then, must have been extraordinarily theatrical, with fires blazing on a surrogate stage situated against the backdrop of a monumental citadel wall that had been constructed 700 years earlier. Whether the circles were intended as a kind of replacement for the abandoned apsidal altar in the Terrace House cannot be determined, but it seems highly likely that some sort of hero cult had been established by this point.

Hero cult has also been identified in an area 80–90 m northwest of the citadel, to which Carl Blegen gave the title “Place of Burning.” It was so called due to the discovery of burned human bones with perhaps as many as fifty cinerary urns of Late Bronze Age date.32 Set within this area around 700 B.C. was a large oval structure measuring 10 × 5.5 m, around which were unusually large numbers of cups and cooking pots, including dinoi, kraters, and amphoras.33 Feasting must have occurred here in the Late Geometric/Early Archaic period, and it may have been related to the Bronze Age cemetery that lay beneath it.

The installation of these cultic facilities coincided with several literary, religious, and political landmarks. One was the composition of the Iliad, at which time one witnesses the acceleration of hero cult on both sides of the Aegean, especially at sites such as Mycenae and Tiryns that were framed by ruined monumental buildings of Bronze Age date.34 There is no proof that Troy’s new cult facilities were tied to specific Homeric heroes when they were first installed, but such an association would certainly have settled in place during the course of the seventh century B.C.

Another landmark was the dominance in Asia Minor of the Phrygian kingdom, which reached the pinnacle of its power in the second half of the eighth century B.C. This period coincided with the reign of King Midas, who was probably on the Phrygian throne at the time in which the Iliad was composed, and this may explain why Phrygia was described as such a prosperous kingdom in the epic. One of the stories in the Lives of Homer even included the claim that Homer was commissioned to write an epigram for Midas, which was reportedly inscribed on a stele and set up at his tomb.35

There has been speculation that the entire region of northwestern Asia Minor was under Phrygian control during this period, primarily due to the discovery of several Phrygian inscriptions at Daskyleion, approximately 175 km east of Troy. Also cited as evidence for such control are a number of legends that mention a link between northwest Asia Minor and Phrygia: Midas reportedly married the daughter of Cyme’s king, and Ilus, son of Dardanus, entered a wrestling match hosted by the king of Phrygia, ultimately winning a cow that led him to the hill of Hisarlık.36 A few Geometric sherds at Troy are decorated with stamped circles and triangles set in alternating rows, which one also finds at Gordion, although the forms at each site are different, and there may be no direct link between them.37 It seems more likely that the Phrygian inscriptions from Daskyleion signal local emulation of a dominant culture rather than outright political control.38

By the beginning of the seventh century B.C., however, it looks as if all or part of the Troad had come under the control of the Lydians. Strabo and Nicholas of Damascus make this statement outright, and the Milesians reportedly needed the permission of the Lydian king Gyges to found a colony at Abydos, near the modern city of Çanakkale.39 The settlement of Daskyleion, which would later become the Persian regional capital of northwest Asia Minor, was named after Daskylus, the father of Gyges, and royal hunts were staged for the Lydian kings near Zeleia (modern Gönen), as they would be later for the satraps of Persia.40 There is no way of determining when Lydian control over the western Troad began and ended, but Croesus, the last of the Lydian kings, had the power to forbid construction of new fortifications at the Troad town of Sidene after he destroyed it, and the city of Adramyttium (Edremit) at the southeast corner of the Troad was named after his brother.41 Consequently, it seems likely that Lydia held control of most of the Troad for nearly 150 years.42 It is therefore striking that only a few sherds of Lydian pottery have been found at Troy, although this parallels the situation at the site during the Late Bronze Age when Troy’s political alliance with the Hittites was not reflected in the material record.43

It is not as easy as one might think to compare the evidence for Archaic habitation at Troy with neighboring sites, since Lesbos is the only other area where a discernible amount of Iron Age material has been found. Bronze Age Lesbos clearly lay within the cultural orbit of the Troad and western Asia Minor, and this appears to have been true for the Iron Age as well. During the tenth and ninth centuries B.C. there is evidence for habitation at several sites on Lesbos: apsidal buildings have been excavated at Mytilene and Antissa, and occupation is attested at Methymna and Pyrrha as well.44 On Lesbos, as at Troy, there is no substantive change in the Gray Ware vessels from the Bronze to the Iron Age, and the Iron Age pottery of Lesbos, like that of Troy, has more parallels in the eastern Aegean and in Anatolia than in mainland Greece, at least through the eighth century B.C.45

With the beginning of the seventh century B.C., there is a distinctive type of pottery produced at Troy that begins to be used at other sites in the North Aegean. This is a fine painted ware usually named G2/3 after the sector at Troy that has furnished a large number of examples. G2/3 Ware was especially popular for drinking sets – cups and small jugs – and the usual decoration features vertical zigzags, step patterns, and hooked spirals.46 Recent neutron activation analysis has demonstrated that Troy was the source of this pottery, and it has been found in early habitation levels at Thasos, Samothrace, Lesbos, Tenedos, and Lemnos. All of these regions may have formed part of a commercial maritime network with Troy by the beginning of the Archaic period, as they had during the Early Bronze Age.47

In assessing the nature of habitation in the northeast Aegean during the Iron Age and Early Archaic period, we would probably be on firmer ground if the evidence for burial customs in the region were more substantial. The one relevant grave at Troy, dating probably to the Late Geometric period, is the poorest of the group, with a contracted skeleton covered by a large pithos sherd.48 Adult Geometric burials on Lesbos tend to be inhumations in cists or large jars, although in the Archaic period clay sarcophagi began to be used on Lesbos, as at western Asia Minor coastal sites further to the south, with earthen tumuli and ring walls often set above them.49 The eighth/seventh century B.C. graves on Tenedos are stone-lined pits featuring both cremation and inhumation, with children inhumed in amphoras.50

The material recovered from all of these graves, primarily pottery and fibulae, can be paralleled most easily in western Asia Minor and on the eastern Aegean islands, especially Lemnos and Rhodes. The fibulae in the Lesbos tombs, in particular, find their closest stylistic parallels with those from Anatolia (Gordion, Alişar, Cilicia), and several of the tomb gifts from Tenedos maintain a distinct Anatolian iconography as late as the sixth century B.C.51 None of this is particularly reminiscent of contemporary burial practices in mainland Greece, although we are, of course, dealing with a limited number of settlements and varying levels of wealth at the sites in question.

The Archaic Period: ca. 650–480 B.C.

Habitation at Troy and, indeed, throughout the Troad, moved in new directions during the second half of the seventh century B.C. Around the middle of the century Troy experienced some sort of disaster: layers of tumbled stones have been found on the western, southern, and eastern sides of the mound; the stone circles in the West Sanctuary go out of use, as does the Terrace House, and the production of G2/3 Ware comes to an end.52 Although this could, in theory, have been either an attack or an earthquake, the similarity in destruction throughout the site coupled with the site’s seismic history makes the latter explanation seem more likely.

It is conceivable that there was a short period of either abandonment or at least a decrease in population after the event, which would fit with Strabo’s description of the Troad during the seventh century B.C. He mentions that all the stones of Troy were taken to rebuild other towns in the area, particularly the new Lesbian settlement of Sigeion.53 Sigeion appears to have been established at some point between ca. 650 and 625 B.C., shortly after the proposed earthquake at Troy, which meant that an extensive supply of loose stones would have been readily available, especially considering that the two towns were separated by only 6 km.

When construction began again at Troy, ca. 625 B.C., there were clear signs of a change. A new limestone cult building (the “Early Archaic Cult Building”) was constructed in the northern part of the West Sanctuary – the first building at the site to have been constructed entirely of stone in approximately 500 years. It contained at least two rooms of nearly equal size, one measuring 6 × 4.6 m, the other, 6 × 5.3 m; there may also have been a third room, possibly a porch, at the west (Fig. 2.5).54 Terrace walls are situated only 1.5 m from the main building, and in light of their proximity, they may have supported a wooden colonnade.55

2.4. Stone-paved circles in the West Sanctuary.

2.5. Plan of Early Archaic Cult Building in the West Sanctuary, prepared by Pavol Hnila for the Troy Excavation Project.

The orientation differs from that of the older buildings in the complex, although it may have been influenced by an earlier wooden structure directly beneath the cult building that has left only a minimal trace in the archaeological record.56 In the fill above the floor was a large burnished Gray Ware krater, nearly twice the normal size, with molded ridges and knobbed ends that clearly imitate metalwork (Fig. 2.6). It looks as if this structure may have absorbed the ritual drinking activities that had earlier occurred in the Terrace House or around the stone circles.57

2.6. Gray Ware thymiaterion from the West Sanctuary.

Shortly after the completion of the new Early Archaic Cult Building, two altars were constructed further to the south, in the precincts that have usually been labeled the “Upper” and “Lower” Sanctuaries (Plate 12 and Figs. 2.2 and 2.7).58 Both are separated by only 4 m, but a precinct wall existed between them, and they differ significantly in terms of shape and function. The former (Altar A), which faced toward the southeast, was apsidal or J-shaped; next to it stood a stone offering table around which were blackened earth and burned bones, but few if any votive dedications. The Lower Sanctuary altar (Altar B) was rectangular and oriented to the northeast. No evidence of sacrifice was found, although a wealth of votive dedications were uncovered, most of which represent females.59 The two altars were clearly intended to serve differentpurposes within the complex – one focused on sacrifice, the other on dedications – and we should perhaps therefore refer to Altar B as a table or platform rather than an altar per se.60

2.7. View of the Upper and Lower Sanctuaries in the West Sanctuary. The Lower Sanctuary, with the nearly square Altar B, appears at left; the apsidal altar of the Upper Sanctuary is at right.

The pottery deposited throughout the West Sanctuary during this period also represented a change from earlier assemblages. Attic and Corinthian pottery now began to appear, as did Ionian cups and the “Wild Goat Style,” thereby attesting to Troy’s connection with a much wider East Greek world.61 Many of the cups were decorated with painted swans, giving rise to the label “Swan Style” to describe the new vessels, which would eventually comprise nearly half of the total assemblage around the altar in the Lower Sanctuary.62 Faunal deposits from the same period have yielded an abundance of fallow deer bones, including antlers, as well as lion bones that may have formed part of skins that decorated the walls or were worn during ritual activities.63

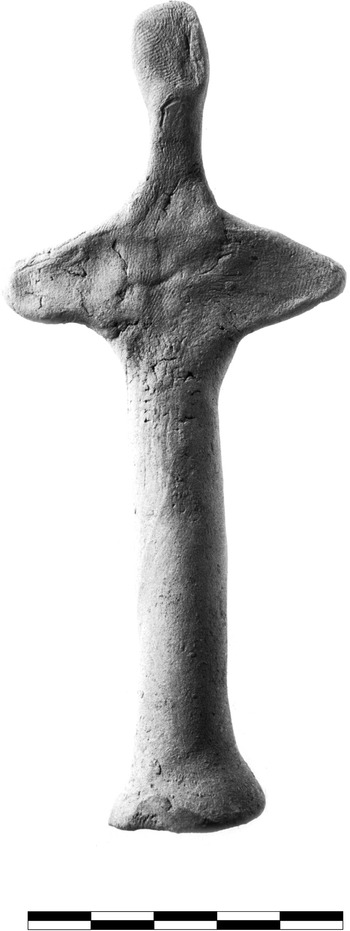

A considerable number of dedications were discovered in close proximity to the altar in the Lower Sanctuary, and several of the most significant include a faience scarab with lion decoration, two fibulae of spectacle type – one bone and one bronze – and a polychrome spindle whorl with horizontal stripes on the cone and a floral design on the base.64 Other undecorated spindle whorls and loom weights had also been deposited here, along with beads, rings, and arrows.65 Blegen found several terracotta figurines of Archaic date by the altar, and we uncovered terracotta heads of swans and geese as well as female heads and standing women, one of which featured a cylindrical body, wedge-shaped arms, a pinched face, and a polos, or tall, cylindrical headdress (Fig. 2.8).66

2.8. Archaic terracotta figurine from the West Sanctuary.

All of the evidence suggests that worship was focused on a female deity linked to swans and wild animals, especially lion and deer.67 The presence of two adjacent altars may point to the co-existence of different cults, although they may also relate to two different functions within a single cult. It is also possible that there was continuity in cultic activity between the new altar precincts and the old Terrace House: the apsidal form of the Upper Sanctuary altar is reminiscent of its predecessor in the earlier building, and Altar B compares well with the rectangular base at the back of that building.68 The distance between the altar and base in the Terrace Building is also approximately the same as that between the two altars in the Upper/Lower Sanctuaries, with a partition wall used to separate altar from base in both cases.

The only problem with this scenario is that by the time at which the new building in the Upper/Lower Sanctuaries occurred, the Terrace House would probably have been hidden from view for several decades, and perhaps close to a century. The earlier structure would therefore not have been visually accessible as a model for the later ones, although memory of the earlier layout may have played a role here. Even if we assume continuity in cult, however, the changes were dramatic: a new stone temple and altars, ceramic imports from a wider area, and probably a new deity, or at least a deity whose patterns of worship had shifted significantly from the Geometric version.

What could have prompted such striking innovations? Surely, part of the explanation lies in the increase in the number of colonies throughout the Troad, in particular, as well as Asia Minor and the Black Sea, in general, during the eighth, seventh, and early years of the sixth century B.C. Judging by the pottery from Cyme, from which Hesiod’s father had reportedly come, a settlement already existed there by the middle of the eighth century B.C.69 Within the sphere of the Troad, Miletus founded colonies at Cyzicus, Proconnesus, Abydos, and Lampsacus, as well as at least ten colonies in the Black Sea, including Panticapaeum, Histria, Sinop, and Olbia. By the end of the seventh century B.C., Athens had established colonies at Sigeion and Elaious, near the mouth of the Hellespont, and Lesbian Methymna had founded Assos, on the southwestern side of the Troad.70 It is only in the early sixth century B.C., however, that we begin to find evidence for written Greek in the Troad, initially in the form of graffiti on vessels, and then on coinage and stone inscriptions.71

For the purposes of Troy, the most important of these sites was Sigeion, the first Athenian colony in the eastern Aegean, which lay on the Aegean coast only a few kilometers northwest of Troy (Plate 11).72 This had been an area under Lesbian control during much of the seventh century B.C., but it was won by Athens ca. 625 B.C. following a battle in which the poet Alcaeus lost his armor.73 Herodotus reports on the competing territorial claims of Athens and Lesbos, in which each region’s involvement with the Homeric tradition played a significant role. By this point, the rulers of Lesbos had already traced their descent from the royal family of Mycenae, and Orestes in particular.74 Athens, in turn, argued that any of the mainland Greek cities providing aid to Menelaus during the Trojan War had as much right to the territory as Lesbos.75 In the end, the conflict was reportedly settled by Periander, tyrant of Corinth, who allowed Athens to keep Sigeion, while Lesbos continued its control of the small town of Achilleion, 9 km to the south.

Judging by the quantities of Attic pottery in the late seventh century B.C. deposits at Troy, the settlement enjoyed frequent interaction with Sigeion, and the time in which the Cult Building in Troy’s West Sanctuary was constructed coincides with the establishment of the Athenian colony.76 This coincidence is difficult to ignore, and it is tempting to link Athenian activity in Sigeion with the construction of the Cult Building, which would not have been inexpensive to build.

The other significant bond between the two cities was that they both honored Athena as their principal goddess, although those temples of Athena are not easy to reconstruct. In his description of the battle over Sigeion between Athens and Lesbos, Herodotus notes that the armor of Alcaeus was installed in Sigeion’s temple of Athena as an Athenian war trophy. The location of the Sigeion temple is unknown and the date of its erection cannot be deduced from any ancient source, but it was presumably built shortly after the victory over Lesbos and the foundation of the colony, so sometime in the late seventh century B.C.77 Athena’s temple at Troy was also probably standing by this point, but all of its stones were most likely reused in the Hellenistic Athenaion, and its precise location on the citadel has never been ascertained.78

On the south side of Troy’s citadel, however, there is evidence for new terracing during the last quarter of the seventh century B.C., which suggests a broader program of construction on the citadel itself, where the Athena temple must have stood.79 In later periods, the fills in these terraces contain debris from the Sanctuary of Athena, and the terrace deposits dating to 625–600/575 B.C. probably derive from the same source.80 It is conceivable that the Athena temples at Troy and Sigeion were under construction at more or less the same time in the later seventh century B.C., in which case there may have been reciprocal influence on both cult and architecture, although in the absence of more tangible evidence, we can do no more than speculate.

The only surviving component of the Archaic temple precinct is a well (Bh), located at the base of a flight of steps that led down from the temenos (Fig. 2.9).81 We have no direct evidence for the construction date of the stairs, but rainwater would have continually run down a slope this steep, and the construction of a stone walkway would have been highly desirable from the beginning of the well’s use. The employment of the Troy VI Northeast Bastion as one of the sides of the staircase made its construction a relatively simple undertaking, while simultaneously supplying a symbolic link between the Bronze Age and Archaic settlements.

2.9. Northeast Bastion. The steps are probably Archaic; the battered fortification wall dates to Troy VI.

That linkage would also have been apparent in one other unique tradition, that of the “Locrian Maidens,” which casts additional light on the early history of the Athena temple at Troy and, indirectly, the Athenian colony of Sigeion. These maidens were the daughters of the aristocratic families of East Locris in mainland Greece who emerged as the principal players in one of Troy’s most important traditions. Locris was the homeland of Ajax, son of Oileus (“the Lesser”), who had raped Cassandra in Troy’s Temple of Athena at the end of the Trojan War. In atonement for the rape, the Locrian nobility were required to send two maidens each year to live in and clean the Sanctuary of Athena Ilias. The maidens arrived at Rhoeteum, near the burial mound associated with Ajax the Greater, and secretly made their way by night to the Sanctuary of Athena where they lived in servitude to the goddess for a year, entering the temple only at night so that they would not be seen by the goddess’ statue.82

The rather large number of ancient historians who comment on this custom agree in general on the basic form of the tribute but disagree on the date when it originated, with some placing it shortly after the Trojan War, and one, Demetrius of Scepsis, in the period of Persian domination.83 The most specific account was written by Polybius, who describes the “Hundred Families” of the aristocracy: “these ‘hundred families’ are those who were identified by the Locrians, before embarking on their colonization, as the ones from which the virgins were sent to Troy, in accordance with the orders of the oracle.”84 The colony in question was Locri Epizephyri in southern Italy, which was founded, according to Eusebius, in the 670s B.C., although the earliest archaeological evidence for the colony is not as clear as one would like.85 In any event, the custom appears to have been established in the seventh century B.C., which would indicate that the temple of Athena must have been founded by then.86 If it had been built prior to 650, we should probably assume its destruction in the midcentury earthquake and a reconstruction ca. 625 when building at Troy began again. Such a sequence would fit well with the evidence for new citadel terracing in the later seventh century B.C.

This examination of the chronology of the Locrian Maidens suggests that Ilion had been identified as Homeric Troy by the seventh century B.C., a date that is in harmony with the appearance of the Iliad itself. Whether one dates the epic to the later eighth or the early seventh century B.C., it is the Troad that has been used as the setting for the narrative, which means that the link between legendary Troy and historical Ilion must have occurred by ca. 700 B.C. at the latest.87 The inhabitants of the city would not intensively publicize that identification until the third century B.C., but the process appears to have begun approximately four centuries earlier, and it must have been well enough established by the seventh century that the Locrians decided to send their maidens there.

Occurring at approximately the same time, in all likelihood, was the identification of the monumental mounds in the surrounding landscape as the tombs of Homeric heroes (Plate 2). The majority of these are settlement mounds, not burials, which date between the later Neolithic period and the Bronze Age. Two of the most famous examples are the mound of Sivritepe, 4 km from Troy, and Karaağaçtepe, often identified as the tomb of Protesilaus, at the end of the Gallipoli peninsula (Figs. 2.10 and 2.11); Hanaytepe and Paşatepe are also cases in point.88

2.10. Sivritepe, usually identified as the Tumulus of Achilles.

2.11. Karaağaçtepe, usually identified as the tumulus of Protesilaus.

The reconfiguring of these prehistoric settlement mounds as burial sites of Homeric characters is not surprising: the Iliad and Odyssey contain several references to the construction of large-scale tumuli for both Greek and Trojan heroes in the vicinity of Troy, and the identification of Ilion’s mounds as “Homeric” burials was a logical assumption once the equation between legendary Troy and Ilion had been established.89 The ancient sources attest to ten of them in the vicinity of Ilion, evenly divided between the Greeks and Trojans. The most famous include Achilles, Patroclus, Ajax, and Protesilaus, although Hector, Hecuba, Aisyetes, Batieia (wife of Dardanus) or Myrina (queen of the Amazons), Ilus, and Antilochus were also featured.90

It is conceivable that some of these “Homeric” tombs were adorned with marble decoration, although the evidence is very slight: sometime around 1892, in Rhoeteum, a large marble anthemion stele was discovered and passed into the collection of Frank Calvert.91 The stele was reportedly found near the tumulus of Ajax, and the palmette decoration suggests a date around 500 B.C. Since there are no other tumuli in the immediate area, it is likely to have come from the tomb of Ajax, which would have held an unusually prominent position in the landscape.92 Rhoeteum was the harbor at which the Locrian Maidens arrived and they probably visited the tomb prior to their trip to Troy, even though this was the tomb of Ajax, son of Telamon (“Ajax the Greater”), and they were atoning for the sin of their ancestor Ajax, son of Oileus (“Ajax the Lesser”). The Ajax tomb was admittedly a special case in that it was linked to a continual ritual as the other tombs were not, but paths to the other tumuli of note must have been constructed by this time, and they probably received some sort of decoration, even if it was only a terminal stone.

At some point during the Archaic period the residents of Ilion appear to have created a treasury of Trojan War relics within the Temple of Athena. Our primary sources for this are Hellenistic and tantalizingly brief: in the course of their descriptions of Alexander’s visit to Ilion, both Arrian and Diodorus note that he deposited his armor in the temple as a dedication to Athena and withdrew from the temple the finest armor and a shield remaining from the Trojan War, which he subsequently wore into battle.93

The passages make it clear that Alexander chose from among several suits of Trojan armor and shields that were kept in the temple, and he was also asked if he wanted to see the lyre of Paris, which may have been another one of the relics.94 None of the authors mention that the treasury had been installed during the Archaic period, but there was very little activity at the site between the early fifth century B.C. and Alexander’s visit in 334, so a date in the sixth century B.C. for the treasury’s inauguration seems likely. Since the temple was reportedly small, even in Alexander’s time, the treasury probably did not occupy much space.

The creation of this treasury would also have tied the temples at Sigeion and Troy closer together, in that the former contained the armor lost by Alcaeus during the war with Lesbos.95 Whether Troy was copying Sigeion or vice versa cannot be determined since the time of origin of the Trojan treasury is unknown, but they would probably have been the only temples in the Troad to feature prizes of armor.

The sources of the treasure were most likely local. A considerable amount of building had occurred on and around the citadel mound during the seventh and sixth centuries B.C., and artifacts of Bronze Age date would no doubt have been unearthed in the course of construction, some of which may well have been of gold or silver. These could easily have been marketed as Homeric, although the source of the armor, and the lyre, remains a mystery. A comparable example of this phenomenon can be found on the island of Kea, where the terracotta head of a goddess, discovered in the ruins of the Bronze Age temple, was subsequently set up on a base within the temple as a locus of cult.96 In both cases, objects of great antiquity unearthed at the site were used to foster a temporal link to and shared identity with the earlier inhabitants.

Co-opting Troy

At the same time in which the Troad was solidifying its connection to the Iliad, a considerable number of new Greek settlements were being established in western and northern Asia Minor as well as the Black Sea. The Milesian colonies in the Hellespont, the southern shore of the Propontis, and the northern and southern coasts of the Black Sea constituted components of a formidable commercial network, and the Megarian settlements in or around the Bosphorus – at Chalcedon, Selymbria, and Byzantium – were undoubtedly competitive responses to those establishments.97 As this competition among the new colonizers gathered momentum, one of the by-products was the construction of increasingly distinctive identities, in which charter myths articulated the city-states’ heroic heritage and justified their territorial expansion.98 This was the beginning of a trend that would not really end until the early Renaissance, and would ultimately involve virtually all of the nation-states in Europe and the Near East.

Many of these myths involve the Trojan War and, by extension, the settlement of Troy itself. An excellent case in point is supplied by the aforementioned custom of the Locrian Maidens, which proved mutually beneficial to both Opountian Locris and Troy. One of the most intriguing features of the Locrian custom was that the maidens could be attacked, even killed, by the Trojans if they were caught outside the confines of the Athena Sanctuary.99 In light of the fact that Troy was hardly a military force at this time (or at any time in the future), one has to ask why the Locrians would have allowed two of their aristocratic children to be subjected to such mistreatment annually on the opposite side of the Aegean. The only sensible explanation is that Locris was simultaneously promoting a link to the Homeric tradition that Troy now embodied, and to their local hero, Ajax, by making the custom a fixed component of their civic identity.100 The later construction in Locris of a temple to Athena Ilias endowed the custom with a kind of bilateral symmetry, and it conferred upon the Locrians a level of prestige far more potent than wealth.101

At this point it is worth revisiting the Athenians’ decision to establish a colony at Sigeion ca. 625 B.C. On the one hand, such a location provided a way station of strategic importance for maritime trade between the Aegean and the Black Sea, which was a commercial corridor of increasing interest to the city-states in Greece and Asia Minor. The plethora of Milesian colonies in the Hellespont, on the southern shore of the Propontis, and on the northern and southern coasts of the Black Sea have already been noted. With the foundation of Sigeion and Elaious shortly thereafter, Athenian colonies flanked the entrance to a maritime corridor critically important to grain exports from the area of the northern Black Sea.102

But there was another clear advantage to this location: it allowed Athens, in effect, to co-opt the Homeric heritage of Troy, which was a heritage to which it otherwise had only a questionable connection. Sigeion lay in the midst of a series of tumuli identified as the burials of the Homeric heroes, and establishing a colony there allowed Athens, through her colonists, to exercise greater control of Troy and its legendary associations than any other city.103

The foundation of this particular colony should also be viewed in conjunction with contemporary politics in and around Attica. Toward the end of the seventh century B.C., Athens and Megara disputed the ownership of Salamis, and in the course of the argument both cities exploited their connection to Telamonian Ajax, king of Salamis.104 The foundation of Sigeion should probably be considered a complementary development, in that it brought Athens into a geographic sphere staked out by Megara several decades earlier with its colonies on the Bosphorus.105

Athenian presence in the Troad did not go unchallenged during the Archaic period. Although it appears that Sigeion was still Attic in the second quarter of the sixth century B.C., Herodotus mentions that Peisistratus had to retake the city from Lesbos, probably sometime in the 530s B.C., which indicates that Lesbos had managed to seize it again sometime around the mid-sixth century B.C.106 The Peisistratid victory at Sigeion and Athens’ subsequent re-entry into the affairs of the Troad nicely complemented the tyrants’ incorporation of the Homeric epics into the Athenian Panathenaea, and the two should probably be viewed as components of the same political program.107

Another component of that program may have been the Athenian colony at Elaious, on the European side of the Hellespont, which had been established at least by around 550 B.C.108 Although no buildings datable to the Archaic period have been discovered there, the nearby mound often identified as the tomb of Protesilaus still survives, as do several literary accounts that describe its original appearance (Fig. 2.11). Some of these heroic tumuli were attached to shrines – those connected to Achilles and Ajax are cases in point – but the mound of Protesilaus was the only one that housed its own oracle. Adjacent to the latter mound during the Late Archaic period was a precinct dedicated to Protesilaus with its own treasury of gold, silver, and bronze, undoubtedly gifts to the oracle similar to what one would have found at Delphi.109 Such an oracular shrine wrapped in a Homeric mantle would have significantly increased the status of Elaious, and it was probably the proximity of the Protesilaus tomb that determined the colony’s location.110

Ilion and Assos in the Late Archaic Period

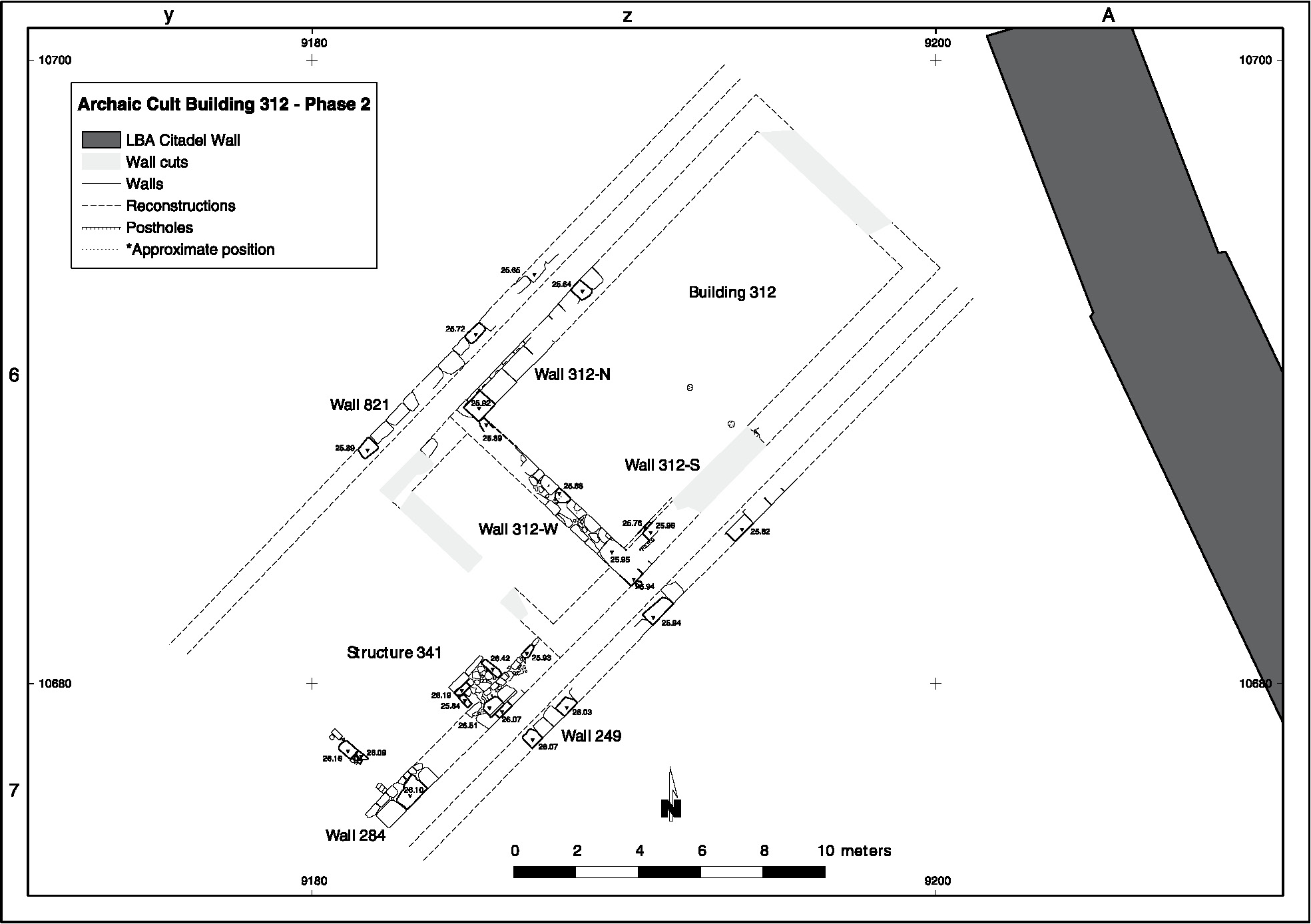

At approximately the same time in which Sigeion was retaken by the Athenians there was renewed construction in Troy’s West Sanctuary, directly above the Early Archaic Cult Building. The new structure, almost certainly a temple, had a length of nearly 18 m and a width of 8 m, and contained a large rectangular room with vestibule, probably the cella and pronaos (Fig. 2.12).111 The overall measurements are about three-quarters the size of the slightly earlier temple at Neandria and the roughly contemporary temple of Athena at Assos.112 Each of the foundation blocks on the north side contains two projecting bosses, similar to those on the Assos temple, and the superstructure was formed by finely finished ashlar limestone in pseudo-isodomic technique.113

2.12. Plan of the Late Archaic temple in the West Sanctuary, prepared by Pavol Hnila for the Troy Excavation Project.

The architectural order was Aeolic, which is characterized by capitals with vertically rising volutes set above a leaf echinus, probably resting on wooden columns with stone bases.114 Only one Aeolic capital was found duringexcavation, but originally there must have been at least two at the entrance; judging by the size of the extant capital, the height of the building would have been somewhere between 8 and 11 m (Fig. 2.13).115 Within the cella there would probably have been a cult image of which no trace survives, but the excavation of the temple yielded a mortised statue base that must have stood either in or around the building. The mortise is in the shape of an oval, similar in size to the mortised bases used in the Late Archaic Geneleos monument at Samos, which suggests a roughly life-size wooden or limestone statue of columnar shape.116

2.13. Aeolic capital from the West Sanctuary.

The altar in front of the temple originally measured ca. 1 m square, although it would be continually modified and expanded over the course of the next three centuries and would ultimately reach a length of nearly 8 m (Plate 12).117 The altar was perpendicular to the building and faced southeast, like the apsidal altar in the Upper Sanctuary, but the two were not precisely parallel to each other.

There are several points of interest here. The building of the Late Archaic temple was contemporary with Peisistratus’ recapture of Sigeion, just as the Early Archaic Cult Building’s construction had coincided with Sigeion’s initial foundation by Athens nearly 100 years earlier. These two synchronisms may be simply coincidental, but it seems likely, at the very least, that the Athenian entry and re-entry into the region stimulated the local economy and facilitated a higher level of construction, of which Troy’s Late Archaic temple was a case in point.

The temple’s other noteworthy feature was the incorporation of the Aeolic order, which began to be used in the public buildings of northwestern Asia Minor toward the end of the seventh century B.C. The earliest examples come from Smyrna and Larisa, but by the sixth century B.C. the style had spread to Neandria, Lesbos, Troy, and Ainos.118 Based on the surviving evidence, it looks as if Ionia followed a similar model shortly thereafter when the Ionic order began to characterize temples in the region, beginning with Samos and Ephesus.119 In other words, architectural style became a device by which the settlements of northwestern Asia Minor projected a particular identity for themselves, distinct from that of other regions.

A parallel development is the formation of an Aeolian league, a political and cultural association that was intended to promote a sense of regional identity and cohesion.120 The league initially included only the cities between Pergamon and Smyrna along or near the coast, but eventually it embraced the entire western Troad.121 The foundation and early development of the league was probably stimulated by a variety of factors, but among them would have been the extraordinary ethnic and linguistic diversity of western Asia Minor during the Archaic period, which would have included Lydian, Phrygian, Aramaic, and perhaps a derivative of Luwian, in addition to Greek.122 Conflict with Lydia, which controlled both Aeolian and Ionian areas during the seventh and early sixth centuries B.C., was no doubt also a contributing factor, as was the advent of Persian control in Asia Minor after the mid-sixth century B.C.123

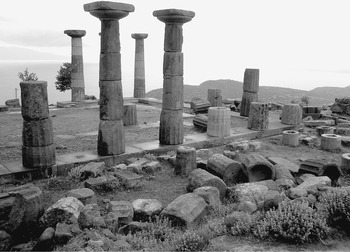

One site within the region that stands apart from the aforementioned Aeolic identity is Assos, at the southwestern corner of the Troad, which had reportedly been founded by colonists from Methymna on Lesbos.124 During the third quarter of the sixth century B.C., at roughly the same time in which Ilion’s Late Archaic temple was being planned, the inhabitants of Assos began constructing an andesite Doric temple to Athena that is still regarded as one of the most idiosyncratic structures in the ancient Mediterranean (Fig. 2.14).125 The temple measured 30 × 14 m, which made it the Troad’s largest building, and its location on the acropolis, directly above the Gulf of Adramyttium, turned it into the most prominent component of the surrounding skyline.

2.14. The temple of Athena at Assos.

The temple is remarkable for both its sculpture and architecture, but one can easily single out three especially important innovations: it was, as far as we know, one of only two Doric temples in the Troad, the other being the temple of Athena at Sigeion.126 It is also the only temple of Archaic date to have featured both carved Doric metopes and a carved Ionic frieze, and the only building in western Asia Minor to have included Herakles in the architectural decoration, although he was prominently featured in mainland Greece, especially within the Archaic pediments of the temples on the Athenian acropolis.127

It is difficult to read such an idiosyncratic choice of order and decoration as anything other than a deliberate statement of civic identity, which, in turn, needs to be viewed against the political configuration of the period in which the temple was constructed. The third quarter of the sixth century B.C. witnessed the Athenian victory over the Mytileneans and the reoccupation of Sigeion, while the Lydian empire that had once extended throughout the Troad now fell to the Persians, who ruled from the satrapal capital at Daskyleion.128 In other words, this was a political climate that continually led to a re-examination of one’s identity and allegiances. It looks as if Assos intended to signal its links with Sigeion, and Athens by extension, rather than Lesbos, and used the most conspicuous landmark in the city as a symbol of those links.

Sometime between 520 and 480 B.C., a major earthquake appears to have brought down the Assos temple, and it probably caused significant damage throughout the western Troad, including at Troy. The Late Archaic temple in Troy’s West Sanctuary was not nearly as solidly built as the Assos temple, so it probably collapsed then as well, and the same fate may have befallen Troy’s temple of Athena and the public buildings in other coastal cities of the Troad.129 When Xerxes arrived in the area with his army in 480 B.C., he was probably greeted by a long stretch of ruins.

The Aeolian Migration

If we now return to the issue of the Aeolian Migration with which this chapter began, two different but interrelated sets of conclusions emerge: one archaeological, the other related to intellectual history.130 An examination of both sides of the Late Bronze Age Aegean demonstrates the commercial and political links between the two areas, with Miletus perhaps functioning as a Mycenaean colony in the thirteenth century B.C. Whether or not we associate the Ahhiyawans in the Hittite texts with the Mycenaean Greeks, it is clear that western Asia Minor functioned as a peripheral region contested by forces associated with both the Hittites and the Aegean.

The twelfth-century B.C. deposits at Troy indicate substantial interaction with Thrace, which probably led to an influx of Thracian immigrants into Asia Minor ca. 1130 B.C. A trading network involving Troy and Thessaly/Locris appears to have developed during the Iron Age, and the custom of the Locrian Maidens may have emerged as a by-product of that relationship once the site of Troy had been linked to the Homeric tradition. By the seventh century B.C., Lesbos had established a claim to part of the Troad, as had Lydia, although the vast majority of colonies in Aeolia were Milesian, none of which dates earlier than the mid-seventh century B.C. At no time during the early first millennium B.C. do we have evidence at Troy for attacks, for the arrival of a new population group, or for any substantive change in ceramic production.131 The ceramic assemblages, in fact, remained remarkably consistent, with very few imports until the sixth century B.C., when Greek also begins to appear in inscriptions.

Throughout the Iron Age and Archaic period, there would have been centuries of interaction between Greek-speaking communities and the native settlements of Asia Minor in which trade, intermarriage, and territorial conflict played a part;132 but the culture in most of the western Asia Minor cities would have been a continually changing blend of Luwian, Lydian, Phrygian, and Greek. One witnesses the same kind of gradual acculturation in the western and southern Mediterranean during the Roman Republic, where Punic, Nuragic, and Berber traditions, among others, co-existed with those of Rome.133 In other words, the process by which Troy became Greek probably involved the gradual adoption of a new identity by the local inhabitants, rather than the arrival of a new wave of immigrants to the site.

If we examine again the ancient literary accounts of the Aeolian Migration in conjunction with the archaeological evidence from the Troad, there are several points of correspondence. The accounts, taken as a whole, stress the roles played in the migrations by Mycenae, Thessaly, Euboea, Locris, Thrace, and Lesbos. As the archaeological record demonstrates, all of these regions interacted commercially and/or politically with western Asia Minor at various points during the Late Bronze and Iron Ages, which probably explains why so many different groups were featured in the migration accounts, but it is clear that no one area played a dominant role in colonizing Aeolis, nor is such a widespread colonization supported by the material record.

It does seem certain, however, that such stories acquired considerable momentum following the Persian Wars, when the promotion of these migration accounts was politically expedient for both Greece and Asia Minor. Mainland Greek cities fortified their allegedly ancestral connection to western Asia Minor, while the cities of western Asia Minor strengthened their political ties to the principal opponents of the Persians, who still controlled most of this area from their provincial capital at Daskyleion.134 Many of the authors shaped their migration narratives in accordance with their own political agenda: thus, Pindar writes that Orestes traveled directly to Tenedos, since the author’s ode that describes the migration was intended to honor a Tenedian; Hellanicus of Lesbos, on the other hand, gives his own island pride of place in the migration.

With such a clear corpus of evidence arguing against a widespread Aeolian migration, it seems somewhat surprising that it has been so readily embraced in scholarship, but here too one needs to examine the political context. Archaeologists began to work in northwestern Turkey during the second half of the nineteenth century, and the colonialist outlook of the time, coupled with the waning of the Ottoman empire, created an intellectual climate wherein stories of the west colonizing the east were easy to accept at face value, as was the assumption that cultural advances on the eastern side of the Aegean, after the Bronze Age, must have been dependent on some agency from the west.135 One can find a similar bias in early surveys of the Iron Age and Archaic period, where “Orientalizing” influence on Greece was either denied, disputed, or undervalued.136

We may never have enough evidence to judge the existence or extent of cultural convergence in the Troad during the Iron Age, but more progress can be made if archaeologists working in Greece and Turkey increase their level of collaboration. Analyses of ancient settlements on both sides of the Aegean are surprisingly rare, and they have become even rarer in the wake of the 1974 separation of Cyprus into Greek and Turkish zones. Dismantling these political barriers to intellectual discourse is essential to achieving a more balanced diagram of cultural interaction in the early Aegean, as is the acknowledgment that cultural change rarely proceeds along a one-way street.