Introduction

This chapter explores various aspects of community land trusts (CLTs), focusing on how this governance model effectively functions as an ownership structure for common pool resources. Indeed, understanding the incentives facing the owners of any communal ownership structure is vital for successfully creating and managing a CLT. These resource commons aspects are conceptually explained and explored through a descriptive account of current practices within the CLT sector.

A CLT is a nonprofit entity that holds and manages land for the benefit of a place-based community, acting as a long-term steward of the land and the assets on it. The CLT model is a classic example of Elinor Ostrom’s (Reference Ostrom1990) idea of a commons, in which a valuable resource (such as real estate) is owned collectively by a community of individuals. The CLT ownership structure creates unique challenges for the community of owners to effectively manage the resource. First, the resource management incentives facing each individual owner of the jointly owned commons resource is significantly different from those incentives facing a lone owner of a privately held resource. Second, the type of information that is needed for the group of owners to practice efficient stewardship of the commons resource is also significantly different from the type of information that is pertinent to the lone owner of a privately held resource. The implications of the unique incentive structure and information needs facing a CLT must be well understood to facilitate effective resource management efforts within and between CLTs.

While land is the primary pooled resource of a CLT, knowledge and data about its use are also valuable pooled resources, both among the owners of a CLT and among a group of CLTs within an organization. Producing knowledge resources and sharing the resulting information between CLTs, and even between CLT staff and their residents or partners, is understudied in the literature across disciplines. Yet leveraging such information in a manner that is compatible with the incentive structure facing the group of CLT owners is key to the success of any one CLT and influences the entire CLT sector.

For example, CLT administrators enable residents and owners to manage their communal resources more effectively through education. This includes activities such as coaching first-time lower-income homeowners through buying and operating a home, or training resident and community leaders in the technical skills needed to govern a CLT. Further, the livelihood and growth of the CLT sector depends on the documentation and sharing of useful information across CLTs. It also includes identifying advocacy priorities, best practices, and robust strategies to face macroeconomic stress factors, such as the Covid-19 shutdown of the economy. The benefits created through these efforts are shared throughout the residents of the CLT. Our mapping of these information flows highlights formal and informal mechanisms, privacy considerations, and channels for information dissemination that range from a simple phone call to digital data portals such as HomeKeeper.

The community, fellowship, and sense of responsibility between present and future members of a CLT provides another interesting example of a pooled cultural resource that exists within CLTs.

This chapter will provide an overview of the CLT model, then explore the CLT in both concept and reality as a land and housing commons, knowledge commons, and cultural commons. Our analysis is guided by the extant scholarship surrounding Ostrom’s design principles of the common pool resource model, and the Governing Knowledge Commons framework. Our methodology, detailed below, encompasses a broad literature review, as well as interviews with key staff across various CLTs and CLT networks, to document their practices and insights. We hope to contribute to existing knowledge commons scholarship by conceptualizing CLTs as knowledge commons, and using CLTs as a unique case study of community property governance and knowledge commons management as it fits within the classic commons literature. We also hope to contribute to the CLT community and practitioners by providing research and analysis in those areas where academic literature is rather scarce to nonexistent, to better understand current practices.

Methodology

We chose to conduct a case study on CLTs because of the parallel ways in which a physical and cultural commons has been understudied. Existing literature around the knowledge commons also tends to center a highly educated demographic, and we believe the CLT presents an example of how a cultural commons can act in service of marginalized groups.

In the writing of this chapter, we examined publicly available information on organization websites, articles, publications, reports, and videos. To supplement the lack of information across some of these themes, we also conducted key informant interviews with staff across individual CLTs and national/regional CLT networks. These discussions were especially helpful for understanding the informal networks of information sharing and practices between CLTs, as well as gaining insights into the effectiveness of their current practices.

A total of six persons, representing five separate organizations, were interviewed by video call. The organizations included: Grounded Solutions Network, Douglass Community Land Trust (DC), Chinatown CLT (Boston), Greater Boston Community Land Trust Network (Boston), San Francisco CLT (San Francisco), and other informal regional CLT consortiums or networks. These video call interviews lasted between thirty and sixty minutes, with additional questions asked during email exchanges.

These organizations were selected due to their relevance to our research question. Questions focused on information flows, community governance structures, and the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. From our contacts, we learned how each of the organizations had addressed these issues. Furthermore, they are active, thriving community land trusts, allowing us to filter out organizations whose experiences are muddied by their lack of resources. The insights we gained from these interviews, whether as evidence of common trends or unique examples, are included in this chapter.

What Is a CLT?

A CLT is a nonprofit entity that either owns or leases land for community-beneficial uses, with a goal to preserve land for the public good and to meet community needs (Emmeus Davis Reference Emmeus Davis2007). In this way, CLTs are stewards of these shared resources, effectively separating landownership from land use and removing it from the speculative markets (Emmeus Davis Reference Emmeus Davis2017). CLTs allow more residents to benefit from the land through lease agreements (Thaden Reference Thaden2018). For example, CLTs often impose a resale restriction on price that is tied to inflation as part of the leasing agreement, which limits the opportunity for potential owners to speculate on the land. Such actions allow CLTs to keep this land both accessible and affordable to future generations.

Today, there are over 250 CLTs in the United States, mostly serving families living at low to moderate levels of income. For example, the average household income of shared equity homeowners in 2018 was only $41,207 (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Cahen, Acolin and Walter2019). Almost three-fourths of CLTs have fewer than two full-time employees, and CLTs tend to rely heavily on volunteer labor (Wang and Rose Reference Wang and Rose2018).

The majority of CLTs hold formal or informal relationships and partnerships with public, private, and charitable organizations, as well as through layering different types of organizations within their respective ecosystems. These partnerships may be via fiscal sponsorship, acting as a shareholding entity, participation in a governing board, the provision of technical assistance or services, or coordinated advocacy (Nicholas and Williams Reference Nissenbaum2020). In particular, affordable housing projects require partnerships with a variety of actors that can help across the areas of real estate, construction, finance, and law. Local governments, charitable entities, or grassroots organizations may help to incubate or start a CLT as a tool for their organization to deliver on their vision of affordable housing or community control of land. For instance, Interboro CLT was started by four New York-based nonprofits (NYC Neighborhoods, Habitat for Humanity New York City, the Mutual Housing Association of New York, and the Urban Homesteading Assistance Board), with the mission to preserve diversity and provide affordable homeownership in NYC (Kunkler Reference Kunkler2021). The City of Houston helped to launch the Houston CLT to promote long-term affordable housing in the city. These relationships come with varying degrees of control and trade-offs to consider.

While residents typically pay lease fees of $25–50 a month to the CLT, this revenue stream is insufficient to keep a CLT operating effectively. This makes CLTs dependent on external funders, such as grants from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development or private foundations focused on promoting affordable housing (Williams Reference Williams2019a). Almost 40 percent of funding for shared equity homes between 1985 and 2018 came from public sources in the form of grants or development loans, while about 60 percent came from private sources, including buyers’ savings, conventional real estate loans from financial institutions, individual donations, and foundation grants (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Cahen, Acolin and Walter2019). The organizations that were interviewed all sought and received donations from both community members and other organizations that had similar missions. Other sources included both public and private lenders, such as housing trust funds, CDFIs, and credit unions. Many municipalities and states have adopted affordable housing trust funds utilizing deferred or forgivable loans.

History and Philosophy of CLTs

The CLT model was inspired by older ideas of common ownership and different movements for the stewardship of land for wider community benefit around the world, including India, Israel, Mexico, Tanzania, and England (DeFilippis, Stromberg, and Williams 2018). In the United States, the CLT model is rooted in Henry George’s efforts at property reform and critique of the prevailing, individualist model of landownership, when civil rights activists merged George’s ideas with movements for community control. In 1969, the first CLT, New Communities, Inc., was founded in Georgia by a group of activists. New Communities was built on 5,000 acres of land, with the intention to decommodify land, provide for permanent community ownership of property, and give black farmers the opportunity to take and maintain control of basic resources.

New Communities was created as “a legal entity, a quasi-public body, chartered to hold land in stewardship for all mankind present and future while protecting the legitimate use-rights of its residents.” The community was conceptualized as a nested set of relationships, involving a resident community living within a trust, and a wider community of anyone who wanted or intended to be a resident or otherwise supported or identified with the trust. Ultimately, the CLT’s community included everyone who might support or benefit from the CLT’s mission, presence, and dramatic reorganization of landownership practices (DeFilippis, Stromberg, and Williams Reference DeFilippis, Stromberg and Williams2018).

The CLT movement reached urban areas in the 1980s as a way to combat increased property speculation in inner-city neighborhoods. Supporters felt that ongoing gentrification threatened the local community with mass displacement. In the 1990s, more favorable policies, increased funding opportunities, and shared learning across existing CLTs helped the CLT movement begin to thrive in the United States (Community Land Trust Network n.d.).

CLT as a Land Commons

CLTs manage so-called governance property, a term that describes many different forms of private property ownership (Alexander Reference Alexander2012). Governance property includes land shared with multiple owners who have the authority to make governance decisions about the land’s use, access, and transfer to other owners. This form of governance is a departure from the traditional model of property ownership common in most Western cultures, which aggregates the bundle of legal rights and entitlements into the hands of a single owner (Duncan Reference Duncan2002). Legal scholars recognize that this fee-simple model of property and resource ownership is increasingly ill-fitting for an interdependent and urbanized neighborhood in which most city-dwellers live. When public or private landownership is predominantly held with such monopoly ownership rights, this leads to significant challenges in leveraging urban property to create value for its users. This challenge is largely the result of the spatial relationships arising from the degree of population density and the proximity issues created by dense urbanization (Fennell Reference Fennell2016).

Contemporary land use requires a diverse collection of approaches to reserve land use opportunities for those who have fewer resources. The context, communities, and shared resources give rise to specific social dilemmas associated with shared use of the resources, given the communities’ needs and goals. Commons such as CLTs provide a means for addressing and overcoming those dilemmas. Land commons can provide the most vulnerable and marginalized communities access to urban resources by recognizing resource governance through property interests via a collective property right, which is needed for such groups to gain access to these lands and resources.

CLTs are one way that city governments are utilizing alternative land stewardship models to provide universal access to critical urban resources across all individuals and communities. Research by Lisa Alexander addresses how property stewardship is created through the CLT arrangement. The profit motive of the individual is replaced by allocating collective ownership rights in a way that gives resource stewards access and control over land and resources without a “fee simple” title. This removes wealth maximization as a primary motivator for resource allocation decisions and “connects stewards to economic resources and social networks that maximize their self-actualization, privacy, human flourishing, and community participation” (Alexander Reference Alexander2019).

Long-Term Resource Stewardship in Residential Real Estate

Typically, the land stewarded by a CLT is used to build and provide permanently affordable housing into the future. The CLT owns the land but not the housing units on the land. Moderately low-income individuals can purchase a CLT house if they have a decent credit history and can pay for the home, which is typically restricted in cost to make it more affordable. The purchase is often funded through a special mortgage that applies to the house but not the land. Further, the buyer pays a small lease fee to the CLT, which stewards the property over the long term. In return, the homeowner is responsible for maintenance of the land.

When the current homeowner chooses to sell to the next qualifying buyer, the future homeowners are informed of the terms of CLT housing ownership. The selling owners receive the equity that they have paid into the home, as well as a portion (usually less than a third) of the increased value of their home. In this way, CLTs enable homeowners to build equity while maintaining a source of affordable housing that is made possible through the ground lease (Williams, Reference Williams2019a).

Grassroots organizations, activists, municipalities, and CDCs have all looked to CLTs as vehicles for promoting affordable housing and anti-displacement. Rising housing and land costs have exiled many families and devastated many communities, even in cities with the lowest unemployment rates (Williams Reference Williams2019a). CLTs are an effective mechanism when land and housing values are rising rapidly because they remove the speculative component of property values and create ownership opportunities for low-income people for the long term. Once it is part of a CLT portfolio, speculators and developers cannot purchase the land. The inability of real estate giants to develop property into lucrative hotels and condos creates a CLT neighborhood that is less likely to become gentrified and unaffordable to lower-income families. Further, the CLT-held land itself will certainly remain more affordable and accessible. Community organizers and other activists have become enthusiastic about promoting the CLT model (Hawkins-Simmons Reference Hawkins-Simmons2014).

The Dudley Neighbors CLT in Boston is a good example of this. Dudley Square is in the Roxbury neighborhood of South Boston and was a predominantly low-income area. Many vacant and tax-defaulted lots plagued the neighborhood, similar to Chicago’s Large Lots Program. Boston-area government and prominent financial institutions neglected the area as the neighborhood deteriorated throughout the 1970s. Over 20 percent of the land was vacant by the 1980s, with the remaining citizens composed of impoverished African Americans, Hispanics, and other minority groups that lacked the necessary financial resources to relocate. The City of Boston decided to transfer ownership of about fifteen acres, amounting to 1,300 lots, to a CLT.

Dudley Square residents responded by incorporating as a nonprofit called the Dudley Square Neighborhood Initiative (DSNI). They created a plan to build an urban village that would not displace the existing residents. This CLT built over 200 affordable homes on the vacant lots, a community greenhouse covering 10,000 square feet of land, a playground, an urban farm, and many other attractive amenities. CLTS collaborated with other community and grassroots organizations to implement the community’s vision for local development. They employed the CLT model to organize and construct a permanently affordable housing community that exercised the control of land necessary to fulfill their vision (Hawkins-Simmons and Axel-Lute Reference Hawkins-Simmons and Axel-Lute2015).

The Lincoln Land Institute of Land Policy has studied fifty-eight shared equity homeownership programs across 4,108 properties, where nearly three-quarters were managed by CLTs. Their analysis indicates that shared equity models have successfully delivered ownership of affordable homes to lower-income families across multiple generations. This is usually attributed to a combination of stable, below-market ground-lease prices and price caps on the resale of homes. The same study found that a shared equity model like CLT “provides financial security and mitigates risks for homeowners facing housing market turmoil,” and suggested that they helped low- and moderate-income residents navigate the volatile housing market fluctuations of 2008 more successfully than other conventional housing models (Wang et al. Reference Mironova2019).

Data has shown that such programs are serving buyers that might otherwise not be able to afford to purchase a home (discount metric) by preserving affordability for multiple generations of buyers (resale metric). Further, these programs allow homeowners to build wealth by retaining a portion of the gains in house appreciation or retiring mortgage debt. These shared equity programs offer a reliable path to sustainable homeownership. Grassroots organizations and CDCs have created CLTs in cities like Atlanta, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Seattle to counteract urban gentrification (Mironova Reference Mironova2019).

Long-Term Resource Stewardship in Nonresidential Real Estate

Sometimes, CLTs steward land for both residential and nonresidential purposes through agriculture projects, green spaces, commercial spaces, playgrounds, other public centers for recreation or social services. For example, the Dudley Street (DSNI) CLT includes urban farm sites, parks and open space, and commercial properties (Loh Reference Loh2015).

Though less common, other CLTs steward land solely for nonresidential purposes. For instance, Southside CLT (SCLT) owns or directly manages twenty-one community gardens, manages another thirty-seven community gardens with partner organizations, owns or manages land used by twenty-five farmers to supply to various food businesses (restaurants, farmers’ markets, community-supported agriculture), and operates three production farms, across Rhode Island.

Local agencies, neighborhood churches, and private schools own and manage these gardens, and the SCLT assists them in providing both training and gardening resources. Their goal is to create community food systems for locally produced healthy food to be affordable and available to all, with a focus on serving low-income urban neighborhoods that may not have access to fresh produce. SCLT also aims to provide the people of Rhode Island with access to land, education, and resources to grow food in environmentally sustainable ways. For instance, they engage in youth employment and children’s summer learning programs, farmer training workshops and apprenticeships, hands-on training in food preparation and food growing. They match farmers with landowners who want to keep their land in production. Finally, they have advocated for increased investment in farmland access programs by the state of Rhode Island and founded the RI Food Policy Council to develop policies and partnerships to increase the capacity, visibility, and sustainability of the local food system (Southside Community Land Trust n.d.).

In another example, the Northeast Farmers of Color Land Trust (NEFOCLT) is a CLT as well as a conservation land trust. It was established to center the voices of and secure land for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color to farm, to conserve land by protecting native species ecosystems and engaging in regenerative farming and agroforestry, and to advocate for climate justice. NEFOCLT also collaborates with allied organizations to provide training and education in markets, business development, and financial planning. They have plans to acquire land to build a flagship community with incubator farms, commons for production, childcare, healthcare, and integrated ecosystem restoration (Farmers of Color Land Trust n.d.).

Nontraditional Property Rights

Some CLTs have attempted to use nontraditional property rights to retain community ownership over land. For example, Chinatown CLT (CCLT) has negotiated for ownership over easements (Lowe Reference Lowe2018). It has reclaimed municipal public land by cooperating with other community partners to convince the city government to undertake a disposition process for a public parcel of land, which is now set to become a multiuse development. This project encompasses 171 separate units of affordable housing. The effort was led by a local community development corporation collaborating with multiple for-profit partnerships and has received strong support from both community activists and residents who shared the project’s vision. It is an example of what can be developed by cooperative efforts between a local community development corporation and potential financial partners.

This is also an example of how a nonprofit CLT can assure public access to a given site without owning the land. It can do so by using an easement as a legal contract and entering in a deed. The CCLT now advises the community as it negotiates long-term public access through easements for an existing courtyard as well as a future branch library. This arrangement rectifies the broken promises given to residents who were promised access to public open spaces that were soon privatized into beautiful but privately gated courtyards. The Friends of the Chinatown Library will have secured an easement that ensures open public access to the library, and the CCLT will have an easement for open public access to a public courtyard.

CLTs might also fund or invest in other projects, where they do not own or lease the land. Sacramento CLT is working with other CLTs on a major project to turn a local creek and surrounding neighborhoods into a space that is walkable, bikeable, and safe. Here, they and other neighborhood groups involved receive funding and permission to act as stewards of public land (Sacramento Community Land Trust n.d.).

Community Governance

A critical component of a CLT’s mission is its efforts to promote a bottom-up style of democratic governance, which is a key component of land stewardship and community control over the land. Collaborative community governance is what gives historically marginalized people a way to participate in decision-making about how their neighborhoods are developed. Classic CLTs have two modes of community governance built into their organizational structures and bylaws. These were well-defined actions designed to keep the CLT aligned with the interests of its residents, and to be held accountable to both its residents and surrounding community or service area. This enables residents and those of the wider community (which could encompass a single neighborhood, multiple neighborhoods, town, city, or county) to influence critical decisions made by the CLT.

The first mode is having a governing board of directors that represents the interests of the people and locality that they serve. The governing board of a CLT has traditionally been “tripartite” in design. This means there is an equal number of seats for (1) homeowners leasing the land from the CLT, (2) surrounding community residents not living on CLT land, and (3) public and private sector stakeholders, such as public officials and nonprofit organizations providing assistance to the CLT or its homeowners. The governance structure of the typical CLT thus differs from the closed, private governance of other common-interest communities such as condos and cooperatives, since the boards of these entities consist only of private property owners (Wu and Foster Reference Wu and Foster2020). Board directors are typically volunteers, and their roles and responsibilities are set out in a CLT’s bylaws. They serve as key advisers on critical organizational questions, and often help with the foundational work of setting up the CLT when it is first starting out (Bath et al. Reference Bath, Girard, Ireland, Khan and Major2012).

Traditionally, directors are elected by the membership – one-third of the board is elected by members who live on the CLT’s land, another third is elected by general members who are part of the community but do not live on CLT-owned land, and the last third is elected by the total membership or the board itself to represent the public interest (Grounded Solutions Network 2018). For example, Dudley Square’s CLT board is represented by local and nearby residents who enforce lease agreements and other obligations of the lessors. The board is structured to reflect appropriate cultural or ethnic groupings that make up the Dudley community. The board has thirty-five seats, twenty of which are reserved for community residents. This group of twenty also comprises an equal number of representatives of the four main ethnic groups inside the community. Board members serve two-year terms, and are elected by the residents. The elected board vets and approves all decisions made by DSNI, but these decisions are always open to community input and participation (Wu and Foster Reference Wu and Foster2020).

Note, however, that the makeup and selection method of the board of directors may differ based on why and by whom the organization was created. CLTs may be established by an existing housing organization, nonprofit, or local government, as described earlier, and likely will not give CLT residents the same representation as a classic CLT. In these situations, the CLT’s board of directors may be partially or wholly appointed by the “parent” organization (which may itself be a membership organization elected by the community) (Grounded Solutions Network 2018).

The second mode is having a membership that elects the board of directors, which is similarly designed to hold the CLT accountable to its residents and the place-based community it belongs to.

The membership typically has two categories: one with all residents who live on CLT-owned land, and another with general members who opt in to support the CLT and pay annual membership fees. However, the makeup of a CLT’s membership varies between different organizations and their aims. For instance, they may retain the two categories but place restrictions on them. TRUST South LA, to achieve their mission of preserving opportunities for local working-class residents to remain in their neighborhoods, restricts their regular membership to low-income people who live or work in the land trust area. (T.R.U.S.T. South LA n.d.). Douglass CLT wanted a dedicated membership that is familiar with CLTs, which means their current membership is relatively small. While all residents may become lessee members, they are not automatically enrolled, but must affirmatively opt in. They have also put a cap on lessee members from different developments in their housing portfolio, to ensure that the membership is not dominated by voices from one development.Footnote 1 Some CLTs may choose to add different membership classes – some organizations, such as SMASH, EBPREC, and Cooperation Jackson, have created a separate membership category for the staff of the organization.

At Douglass CLT, the key responsibilities of the membership involve attending the annual meeting and weighing in major decisions such as voting on the board of directors, bylaw changes or other changes to governing documents, or the sale of property. Members may also pay dues, review annual reports, or serve as board and/or special committee members. In addition to these, there are other opportunities for members to participate based on their skills or interests, such as organizing events or sourcing new properties (Douglass Community Land Trust n.d.).

Aside from these two iconic organizational structures, there are also other methods in which CLTs provide the community with methods for engagement, leadership, or control.

One such method is starting up specialty committees within the CLT, which means a wider group of interested members can learn and participate with more flexibility or based on specific interests. The San Francisco CLT has volunteer committees working in the areas of policy, membership, fundraising, finance, and projects (San Francisco Community Land Trust n.d.). Sacramento CLT has held working groups where members have convened around vacant public lands, tiny homes, and land acquisition strategies (Sacramento Community Land Trust n.d.).

Another method is participatory planning. Participatory planning involves engaging the community in what they want to see developed in addition to housing built on the land trust. This could be commercial projects, a greenhouse, or even developing agricultural land. For example, the priorities for Boston Chinatown’s development of the community land trust involved scouting out and developing a vision for remaining public parcels. This work involved engaging with communities about what they wanted to see there and how their community land trust’s priorities could be served.Footnote 2

A tangible example of how such decisions are worked out in the CCLT involves the Reggie Wong Park. The homes of one group of residents abut the park, in an area that includes the leather district. They wished to retain access to the park for family use while another group of residents wanted to play nine-man volleyball in the park. Even though some tension has existed around determining the top priorities for developing the park, the residents still have highlighted the opportunity to remain unified in the mission. The CLT brokered an agreement that allowed every group to access the park and helped build a bridge of understanding between the two groups, especially by communicating the Chinese residents’ stories. They helped publish an op-ed about why volleyball was so meaningful to the Chinese residents there. This work enabled these two groups to coexist in their use of the park.Footnote 3

Issues in Theory and Practice

While the CLT model has great potential to empower marginalized people and communities, and many CLTs in the past and present have successfully done so, it is important to acknowledge some limitations of CLTs today.

Academics have noted that the original goals for community ownership of land and local democracy may no longer be the priority for many CLTs today (DeFilippis, Stromberg, and Williams Reference DeFilippis, Stromberg and Williams2018). Rather, many practitioners and advocates have focused on aspects of the model most aligned with individual property ownership, and CLTs have shifted to act primarily as providers of affordable homes. The CLT acts as landowner, property manager, and steward of affordable units, with most of their staff devoted to housing development and stewardship (Hawkins-Simmons and Axel-Lute Reference Hawkins-Simmons and Axel-Lute2015). With affordable homeownership as the primary goal, CLTs may no longer see community control of land as the goal, and the provision of affordable housing as just one potential method of achieving this and serving the community.

Prominent CLT scholars have hypothesized that this shift is due to realities of funding, issues of scale, limited methods of successfully securing broader political support, industry perceptions of success, and limited staffing capacity (DeFilippis, Stromberg, and Williams Reference DeFilippis, Stromberg and Williams2018). Most CLTs are not self-sustaining, and are financially dependent on external funding sources, which come with their own stipulations and agendas (Mironova Reference Mironova2019). In recent years, the housing crisis and affordable homeownership has increasingly been prioritized on political agendas, with CLTs starting to gain traction as a model to achieve this. Many CLT funders have thus supported residential developments for this reason. Additionally, nonresidential developments are less lucrative and more logistically challenging (Williams Reference Williams2019b). It can also be easier to measure or demonstrate the impact of residential developments – for example, via the number of affordable homes secured. This may be why funding for nonresidential land uses, such as for playgrounds or community gardens, are much more difficult to find or attain.

Theoretically, the goals of affordable housing, reducing displacement, and community control go hand in hand, as they are all methods to assist low-income or marginalized people. However, academics have argued that the ground lease provides limited community control when CLT land is used for housing. For example, even though CLTs own land in perpetuity, community control is only exercised when new land is acquired. After the CLT leases the land out, typically for housing purposes, it is no longer able to make decisions, exercise control over, or access the land, as that is now the right of the homeowner to the exclusion of the rest of the community (Williams et al. Reference Williams, DeFilippis, Martin, Pierce, Kruger and Esfahani2018).

Furthermore, the focus on a narrow goal like providing affordable housing, rather than a broader, more systemic approach to empowering marginalized people through community control of land, means that many CLT funders may miss all the other ways the local community’s needs can be met or its residents engaged (Williams Reference Williams2019a). There is a myriad of ways that communities may need or want to use land beyond residential developments – urban agriculture, commercial development projects – which may serve different needs of local residents and aid the resiliency of the CLT itself. Indeed, one study has found that CLT involvement with urban agriculture or commercial development projects can drive economic development, diversify the CLT social base, build new partnerships, promote organizational resilience, and increase organizational visibility (Rosenberg and Yuen Reference Rosenberg and Yuen2013).

Another difficulty is that the burden largely falls on the frequently understaffed CLT to actively maintain a culture of participation. It can often be difficult to engage the community, as a study has found that efforts by staff to involve homeowners in greater participation within the land trust were unsuccessful (Thaden and Lowe Reference Thaden and Lowe2014). One study found that homeowners/people were drawn to CLTs because they needed a place to live, rather than to engage with the community (Kruger et al. Reference Kruger, DeFilippis, Williams, Esfahani, Martin and Pierce2020). In conversation with Douglass CLT, they found that it was difficult to show people that it was worth getting involved in. There is the constraint of time – residents have day jobs (potentially multiple jobs), childcare, and other responsibilities. They already interact with CLT staff for logistical practicalities. There is a second constraint of demonstrating to people that their efforts would have an impact. Participation can be particularly difficult with underrepresented people, who have previously felt used, or have not seen results from prior efforts in participation. Additionally, it may be intimidating for some to speak up or participate when they are put in a room with unfamiliar people, some of whom may have more assertive personalities.

Though these issues illustrate some challenges of the CLT structure and norms to achieve the goal of community landownership, CLTs have chosen this management structure to better serve local communities in ways that are not possible through traditional private landownership.

CLT as Knowledge Commons

The CLT sector is home to a large knowledge commons, where information is a nonrivalrous shared resource that is collectively owned and managed by the community. Many practitioners have highlighted this critical need “to have knowledge and technologies that are owned by the movement, to transfer these practices across organizations and within organizations to community members” (Shatan and Williams 2020, 42).

In the following section, we explore the knowledge commons and information flows (1) between different CLTs through national, regional, and local networks, through formal and informal channels and (2) between individuals within one single CLT, meeting the need for knowledge to be owned by the CLT movement.

The conceptualization and grouping of inter and intra CLT interactions draws from literature around cross-boundary information sharing, and why individuals or organizations share information at interpersonal, intra-organizational, and inter-organizational levels (Yang et al. Reference Yang and Maxwell2011).

While CLT practitioners engage in interactions both between and within CLTs for the benefit of the CLT they serve, the type of information shared, parties involved, meeting forums, and nature of interactions differ greatly. Interactions between CLTs provide practitioners space to navigate common obstacles, share best practices, and find emotional support. Interactions within CLTs are more varied in purpose and encompass most interactions that make up the day-to-day operations, functioning, and management of a CLT.

Interactions between CLTs

Between different CLTs, knowledge is often freely shared, and inter-CLT relationships are characterized by a collaborative ethic. Several CLT practitioners we interviewed mentioned that this is something they appreciate about the CLT sector and movement: practitioners are excited to share information about what they’re doing, and what has or has not worked for them.

The success and expansion of the CLT sector relies on documenting and publicizing useful data, and sharing technical knowledge, skills, and advice that covers the creation and operation of a successful CLT, between different CLTs through formal and informal networks.

These networks provide CLT members tactical and strategic support. The shared knowledge provides a starting point for practitioners to work from, despite the varying political and social landscapes that each organization occupies. They can speak about best practices for grant writing, strategies to collaborate more effectively with partner organizations, how to navigate property taxes, trends they are seeing, and to problem solve on making the CLT model work on a granular level. The network can help prevent duplication of effort between members to hopefully free up capacity for other work, and also leverage work that they each are doing to have maximum benefit. The regular communication and coordination also help local CLTs to align on their advocacy goals and shared reputation as CLTs to tell a larger, cohesive story across the region, which is important to secure funding, favorable policies, and continue to advance the narrative around CLTs.

Not only are CLT networks important spaces to think and problem-solve; the network and other members can provide solidarity and emotional support. As one practitioner said, it can sometimes be difficult not to get overwhelmed by the logistics and realities of running an organization or stewarding land. The networks and regular meetings can help remind them of their collective mission, principles, and the goal of collective community control and stewardship that is at the heart of what they’re trying to accomplish.

Within the United States, there are various networks and organizations dedicated to supporting existing and emerging CLTs through sharing experiences, connecting expertise, and deepening their knowledge base and capacities.

National Organization

Inter-CLT networks include national organizations such as Grounded Solutions Network, a nonprofit that focuses on building inclusive communities and affordable housing solutions by supporting practitioners and policy-makers.

Part of its work includes providing dedicated support to the CLT sector by conducting and publishing research to explore emerging ideas, working with policy-makers to advocate for policy change or secure resources (Grounded Solutions Network 2017), providing technical assistance, and developing publicly available resources, including a toolkit and technical manual that are published on its website. It also supports and works more directly with CLTs through initiatives such as the CLT Accelerator Fund and Catalytic Land Cohort Initiative. It has also provided resources on topics such as Covid-19, and step-by-step guides to help CLTs plan for advocacy initiatives and build relationships with elected officials and congressional representatives (all websites can be found at Grounded Solutions Network n.d.). One CLT staff member we spoke to mentioned that the roundtables and events, especially the national conference that GSN holds, as one of the best ways practitioners can get together. These have continued online over video conferencing technology through the pandemic.

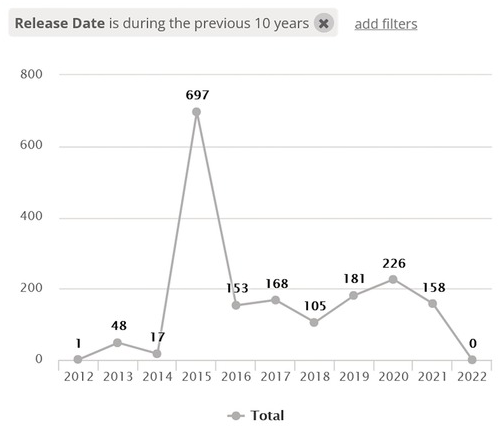

GSN also aims to collect data on members’ portfolios to “improve sector-wide impact measurement and learning” and “better understand trends and characteristics of shared equity programs and homes and build support for the field.” The HomeKeeper National Data Hub Dashboard is GSN network’s publicly available database designed to evaluate the performance of affordable homeownership programs like CLTs, with the ability to filter across regions, market conditions, and demographicsFootnote 4 (Homekeeper 2021a). It calculates metrics such as the discount metric, which shows how the programs serve buyers who may not otherwise be able to afford to purchase a home, and the resale metric, which shows how affordability is preserved for multiple generations of buyers. The data is provided by organizations that use the HomeKeeper Program Management application, which they collect as they administer their housing programs.Footnote 5 As of April 2017, this dashboard reflects the data of 54 organizations, 80 affordable homeownership programs, 6,000+ permanently affordable homes, and 7,400 home sale transactions. The data collected on this platform is able to inform policy and research and show stakeholders and funders how CLT programs have helped communities across the country. In 2016, HomeKeeper Hub data was used to help convince the Federal Housing Finance Agency to incorporate shared equity homeownership as part of its Duty to Serve rule that requires Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to increase lending to underserved homebuyers (Grounded Solutions Network 2017).

When organizations have differing information systems, it can be a challenge to integrate these systems, bridge inconsistent definitions, and thus share data between organizations (Yang and Maxwell Reference Yang and Maxwell2011). Before HomeKeeper, there were no standard data collection practices within the CLT sector or between CLTs, and this platform has helped to facilitate low-friction information sharing and use between CLTs.

There are also various online resources and groups dedicated to collecting, developing, and centralizing resources for CLTs, including the Schumacher Center for a New Economics and Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, which act as other points of knowledge collection and sharing.

Regional and Local Networks

Coalitions also exist to serve CLTs within a more concentrated geography, with a focus on sharing resources and building capacity of CLTs in specific areas, and more regular live meetings between peers that are often facing similar political, legal, or geographical circumstances (Schumacher Center for New Economics).

For example, the Northwest CLT Coalition enhances the activities of CLTs in the Northwest region, including across the states of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Alaska, and Montana, and currently has twenty-nine member organizations. The California CLT Network supports CLTs across the state of California, and has twenty-three CLT members. The Greater Boston CLT Network was founded in 2015 to serve current and emerging CLTs in and around the City of Boston, with eight CLT members and other community group members. Some of these coalitions are formally incorporated (there are currently at least eleven across the United States) (Schumacher Center for New Economics), and have dedicated staff members.

Others are more informal. One such peer-to-peer network was created when several practitioners met at a GSN conference where they were panelists. The similarities that drew them together were their shared locations on the Atlantic coast (New York City, Pittsburgh, South Florida), and similarly aged organizations (all relatively new CLTs). After first making contact at the conference, when they returned home they engaged in informal skill and information sharing on issues and strategies ranging across community education, financial acquisition methods, rehab acquisition, and property management.Footnote 6

No matter the size or region, these coalitions are characterized by similar aims and tactics. To serve as a means for established and new CLTs to connect, support, and share resources, tools, and information, and to collaboratively engage in operational and technical skill-building, they organize regular live meetings, workshops, or working groups. They might produce resources specific to their region – for instance, five California CLTs worked together to release the Building Healthy Communities Community Land Trust report with recommendations to philanthropists, media, and other partners about scaling up the CLT movement in California (Hernandez, McNeill, and Tong Reference Hernandez, McNeill and Tong2020). They may also inform and advocate on policy issues together. For example, multiple California land trusts worked together to advocate for funding for SB 1079 Homes for Homeowners Not Corporations, and to develop Senate Bill 490 (Caballero) to establish funding sources for technical assistance and building acquisition and rehabilitation by community-based housing justice groups (Sacramento Community Land Trust). Networks may also provide education to the public about CLTs to promote understanding of the model and efforts around housing advocacy or organizing. Finally, they may apply for grants or funding together, or collectively invest in or fund projects, acquisitions, new CLTs, or site development.

While many of these relationships may have developed through in-person meetings or interactions, communications often take place through phone calls or emails. This is especially true in the wake of Covid-19. At CCLT, Covid-19 has actually strengthened the peer learning within the network, as practitioners have become more electronically connected and engaged in more policy advocacy, geared toward existing local housing programs, especially as the problem of housing has been exacerbated by the pandemic.

Personal Relationships

Communication between individual practitioners of different CLTs can be highly informal and personality based, as part of a personal social network rather than affiliation or membership within any network. While the purpose and content of these interactions may be similar to interactions between practitioners within a network, personal relationship interactions are characterized by the one-on-one size (rather than a large group), a more ad hoc tone of meeting, and the individuals may not have common membership to any organization. These relationships can arise through meeting at a CLT-related event, referral by another contact in the space, or when previously working together in a different job or region.

According to information theory, an individual shares information when they make the connection between acquired information and the information needs of another individual (Rioux Reference Rioux, Fisher, Erdelez and Mckechnie2005). An individual might share information to establish mutual awareness, educate on a common interest, or to develop rapport and strengthen the relationship (Marshall and Bly Reference Marshall and Bly2004).

This is reflected within the nature of interactions between CLT practitioners, which are often reactive. Practitioners often check in with each other when a problem comes up in their work, to understand whether their counterparts are currently facing or have previously faced the same issue. They might also review issues and problem-solve together. Similar to the abovementioned effects of being part of formal networks, having these touchpoints with other practitioners can help to establish mutual awareness of common issues and solutions to bring back to their own work and communities. More than larger group meetings, these one-on-one conversations can help to build rapport and strengthen the feeling of solidarity. This is because informal coordination is not defined by a set hierarchy or structure, and can therefore lead to greater flexibility, openness, and potentially more effective information sharing (Jarvenpaa and Staples 2002).

Interactions within CLTs

The next layer of interactions that we examine are the information flows that occur within any single CLT. For this section, we take a broad definition of what constitutes interactions within CLTs, including any interactions between formal members of a CLT (such as staff, board members, or residents), as well as with the broader place-based community of which the CLT is part.

While there has been extensive research on intraorganizational information-sharing flows, most of this literature has focused on the behaviors and sharing between the employees of an organization. This research has raised concerns around competition between employees, and lack of incentive to share information due to a company’s hierarchical structure and organizational culture (Tsai Reference Tsai2002). The CLT is a unique case study because almost none of the interactions we describe take place between CLT staff. This is because many CLTs have one or fewer full-time staff members (Wang and Rose 2018), and because the nature of a CLT job is external facing and requires intense communication with stakeholders outside their own organization. Rather, most interactions we have detailed take place between a CLT staff member and a stakeholder with different relationships, responsibilities, and viewpoints about the CLT. For example, a full-time CLT staff member is under an employment contract and paid for their work. On the other hand, board members have committed to responsibilities but are likely not financially compensated for that work, and most residents who are not in leadership positions have no obligation to participate in CLT governance at all. Many of the factors that influence quantity and quality of information sharing between employees of one organization therefore may not be relevant to CLTs or other NGOs that share similar circumstances. As such, the information flows we study within a CLT present new types of interactions that are less represented in information-sharing literature.

Next, we map out the common types of information flows within a CLT.

Internal CMS and Record Keeping

The HomeKeeper application, developed by Grounded Solutions Network and built on the Salesforce platform, is a web-based application and enterprise CRM system used by CLTs across the United States. It helps programs track, manage, and report on homeowner, property, and funding data, and to measure impacts of their work, all in one system. This helps standardize program administration among program staff, run daily operations, make program decisions, and tell an impact story (i.e., return on investment for sellers, the growth of community investment over time, and the extent of affordability created by the program). For instance, Athens Land Trust uses HomeKeeper to track individuals who are interested in their program. One staff member said he groups prospective homebuyers by income, and when a property becomes available in their price range, HomeKeeper allows him to quickly run a report and contact the group with information about the home (Grounded Solutions Networks 2017). This data is also aggregated and anonymized to feed up to the public HomeKeeper dashboard, described earlier.

Information Flows between CLT Staff and Residents

All Residents: Education for Personal Financial and Homeownership Resilience.

A key CLT stewardship strategy is the transfer of personal finance and home management knowledge from CLT stewards to CLT residents. This is one of the most significant and impactful information flows that occur within a CLT.

According to studies done by the National Community Land Trust Network, “85 percent of CLTs required general homebuyer education and 95 percent required a CLT-specific orientation” (Thaden Reference Thaden2010). These generally take the form of educational programs and workshops, as well as one-on-one consultations or advice. For example, 1Roof’s CLT program involves a Home Stretch workshop of homebuyer education, which helps attendees determine their readiness to buy a home, understand credit and its impact on the home-buying process, decide what type of mortgage is best for their needs, select the right home, understand the loan closing process, understand the roles of local professionals (i.e., local loan officers, realtors, home inspectors, closing agents, home insurance professionals), and learn about local mortgage loan and down-payment assistance programs (1Roof Community Housing 2019). The CLT-specific orientation at Douglass CLT provides education on what CLTs are, what shared appreciation is, and advice about whether a CLT model suits the individual and their situation (i.e., can they afford to buy something without economic restrictions instead?).

The NCLTN study also found that about half of CLTs offer post-purchase services, including ongoing monitoring and early issue spotting and intervention. These include financial literacy training, referrals to contractors for improvements and repairs, loan review and approval, and mandatory counseling for delinquent homeowners, which all “build homeowner competency and security.” Typically, CLT staff are often also in contact with residents as the situation arises on an ad hoc basis and provide hands-on assistance and counseling through phone calls and house visits. Residents will call about housing-related problems that have arisen, whether because the housing management company is not responding, they have a question about the land lease fee, or there is an emergency.

“These stewardship activities … address the challenges and risks that may arise over the course of a lower-income household’s acquisition and operation of a home” (Thaden Reference Thaden2010). This knowledge foundation and open flow of communication provided by the CLT is often thought of as key to the low rates of CLT mortgage foreclosures even in times of macro- and microeconomic distress.

A 2019 report published by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy studied 58 shared equity homeownership programs and 4,108 properties (73 percent of which were CLTs) over the past three decades. It found that shared equity models like CLT “provides financial security and mitigates risks for homeowners facing housing market turmoil,” and suggested that they helped low- and moderate-income residents navigate housing market fluctuations in 2008 more successfully than other conventional housing models: 51 percent (of fifty-seven) seriously delinquent CLT homeowners were able to avoid foreclosure due to the help of their CLT in the 2009 financial crisis (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Cahen, Acolin and Walter2019).

Anecdotally, similar results and strategies are already starting to show in regard to the impact of Covid-19, which has had similarly dire consequences in foreclosures and evictions. For example, Grounded Solutions Network representatives have noted that CLTs have been modifying rents to help residents and have advocated on behalf of residents to change interest payments. OPAL, a land trust in Washington state, has also mentioned a policy with residents of “pay what you can when you can,” and providing assistance by consulting with tenants for tailored advice, connecting them with existing resources, and thinking through payment plans.

In the eleven months between March 15, 2020 and February 12, 2021, when Covid-19 hit the United States, none of the 228 current CLT homeowners in the HomeKeeper system had suffered foreclosure (HomeKeeper 2021b). In comparison, between June and August 2020, 7 percent of people surveyed nationwide experienced eviction or foreclosure (US Census Bureau n.d.). These knowledge resources enable the economic development of residents and continued tenure of their homeownership.

Covid-19, Digital Tools, and Channels of Communication.

Due to Covid-19, residents are hard to contact, especially with stay-at-home and social distancing rules. The solutions that CLTs are using to mitigate this include manual reach-outs for early detection of risks, technology adoption (such as accepting virtual paperwork and e-signatures, building websites to push information out, member portals), and holding meetings online on video conferencing tools and virtual training. These projects were prioritized because of Covid-19, as organizations knew they couldn’t get people together traditionally. It is hard to meet anyone in person, and difficult to build trust and get people to participate if the relationship of trust was not already there.

This issue is exacerbated by the digital divide and the lack of residents’ access to or knowledge of technology. While CLTs as a sector are continuing to figure out how they bolster their tech (i.e., e-signatures), homeowners are within a certain income bracket, and their technology is not very good. Their main communications technology is phones. The question becomes: how do you bridge that divide of having a homeowner give you documents when those documents have to be photographs of paper without very good resolution? The issue is exacerbated for elderly people , as well as for those who are not native English speakers.

For example, CCLT has noted that the elderly feel less comfortable with technology, making it hard for them to participate. Historically, CCLT’s strongest resident involvement and connection has been with elderly Chinese-speaking residents who have not received a lot of education. However, they are now the most difficult sector to stay connected to. They may not have the tech, and if they have the tech, they can’t figure out how to use it. CCLT has worked together with other community organizations to produce bilingual guides to technologies and phone operating systems, as well as a Chinese language workshop. However, that often still involves patience and time to help someone with the tech, something that is often taken on by volunteers. There are also unique challenges to holding online meetings on video-conferencing tools in two languages, such as increased cross-talk.

Resident Leaders and Board Members: Building Leadership Capacity.

As part of a CLT’s community governance structures, there are also residents who are highly involved in leadership and functioning of the CLT – for example, board members or active residents who are highly involved in specialty committees.

CLTs rely on their membership or board of directors to help answer questions that may be very technical, legal, or financial, but many community members may not have the technical skills or experience. This means that CLTs face the challenge of making these questions accessible, and to pass this technical knowledge on to community members. CLTs therefore need to build and utilize their knowledge commons to create practical training and learning opportunities for their resident leaders to govern and manage the CLT in the long term. Capacity building is also crucial to having an equitable and representative board or membership that represents the community the CLT aims to serve (i.e., those with knowledge of the community’s needs, and recognized by the community as having this knowledge) (Community Land Trust Network 2018). Training can ensure technical skills or experience do not become a barrier to participation, while also equipping interested participants with the ability to address those needs and govern effectively (Bath et al. Reference Bath, Girard, Ireland, Khan and Major2012).

Areas in which participants may receive training include budgeting, fundraising, legal agreements, property management, project management, effective board membership, transformative politics and racial justice, and an understanding of how to build relationships and run an organization cooperatively (Shatan and Williams Reference Nissenbaum2020). Training may take the form of orientation for new board members, annual board retreats, attending or participating in CLT conferences or government programs, or organizing seminars through hired consultants or local community agencies. Knowledge may also be passed through informal conversations between members, and through written materials like the bylaws or strategic documents (Bath et al. Reference Bath, Girard, Ireland, Khan and Major2012).

Douglass CLT has invested heavily in building the capacity of its board of directors, who are elected by the membership, and have remained the same fifteen members for the last two years. Douglass CLT has engaged in leadership training, organized technical education sessions, and brought board members to conferences where they spoke on panels and met others in the CLT network. They noted that the conference was crucial for them to make new connections and build their confidence as community leaders in their CLT.

Resident Leaders and Board Members: Engagement Obligations.

As part of their relationship with the membership and governing board, CLT staff engage them in important decision-making, keep them informed of upcoming events, and reach out when major issues arise. These responsibilities are typically outlined in the CLT’s bylaws.

A board itself may also further delineate roles within an executive committee of several officers, such as a chair, treasurer, and secretary, which the board itself elects. Given the specialized role that any individual board member may play, as well as each of their duties to participate, information flows also occur between the members and without any CLT staff. This may occur when ensuring that board members are fulfilling their responsibilities, and facilitating constructive communication between members (Bath et al. Reference Bath, Girard, Ireland, Khan and Major2012).

While these boards are a critical resource, serving as key advisers and decision-makers, their time is limited given that they are often volunteers. As such, CLT staff must concisely detail and report to the board what is most important, providing them with the information they need, in a such a way that they can quickly digest and act on it.

Issues of privacy come into play with this information flow, as CLT staff must ensure that they keep personal information about residents private. This may be difficult as they may work with one individual in several capacities (as a resident, lessee board member, friend, etc.), and the appropriate boundaries of each capacity must be respected as they interact and share information. CLT staff must take care to not overcommunicate personal details or reveal potentially sensitive information to organizers on the ground, while still enabling those individuals to do their jobs. In practice, this means that CLT staff limit the information they share to a need-to-know basis, according to context – they may report to the board that people are behind on rent, and aggregate figures, but not the details of specific individuals who may be behind on rent and why. The motivations behind this behavior exemplify Helen Nissenbaum’s (2004) theory of contextual integrity, or the idea that privacy is maintained in information flows when those information flows conform with the norms, expectations, and accepted behaviors in a particular context. In this case, the context is the capacity in which each individual is acting in relation to the CLT, and the fact that this information exchange is occurring for the benefit of the CLT.

Interestingly, this parallels the situation of the CLT being unable to access or directly manage CLT land that is used for housing purposes (i.e., that is being leased to a private homeowner). Here, due to privacy concerns, members of the board may not be able to access or directly manage information about a resident that is collected by CLT staff. Just as CLT board members, staff, and other community members do not have access to CLT land that is leased out, many of these stakeholders also do not have access to specific homeowner information that could potentially influence aggregate homeowner group behavior in a way that would promote the best interests of the CLT and/or the community. However, while the inability to access CLT land used for housing purposes illustrates an inherent limitation to the CLT structure within the existing US laws of real property, the restriction of information flows due to privacy norms does not present the same barriers to a CLT’s goals. In fact, ensuring that privacy is maintained can build confidence and create a trusted network for sharing information between individuals (Razavi and Iverson Reference Razavi and Iverson2006). It is also unclear whether having specific, detailed information about individuals would help decision-makers more than aggregated figures or trends that they already have access to, further reducing the impact of this privacy tradeoff.

Information Flows between CLT Staff and Partner Organizations

As described in a previous section, CLTs have relationships with various partner organizations, ranging from grassroots organizations, resident associations, social service agencies, community development groups, small landlords, the government, funders, developers, other CLTs, and other mission-aligned organizations (Shatan and Williams 2020). Some are peer organizations that work to produce programs jointly, and information flows equally between both parties in service of this. However, CLTs may have formal obligations to other organizations, such as reporting requirements to funders or the board, and the onus is on the CLT representative to share information in meetings or by preparing reports.

Information Flows between CLT Staff and Policy Stakeholders

CLTs also educate stakeholders in the public sphere (elected officials, politicians, political staffers, municipal workers) on the CLT model and its goals/benefits, and advocate for legislative priorities that support the CLT sector, housing, affordability, or other issues in their community. This is often done in partnership with other CLTs through CLT networks or other mission-aligned nonprofit organizations, but is also done by individual CLTs on issues specific to the concerns and lived experiences of their place-based community. This includes issues such as short-term rentals, vacant properties, parking permits for their cities or neighborhoods (Shatan and Williams 2020), improvements to the local food system, and farmland access programs (Southside Community Land Trust n.d.). This type of advocacy can work not only to inform policy stakeholders, but also to build trust and support for their work within their community.

Information Flows between CLT Staff and the Public

CLTs may educate the public about the CLT model and provide community services. This is especially true for nonresidential CLTs, as their use of the land they steward tends to benefit all residents in the area rather than just one homeowner, whether that is through a playground or community garden. Their programs also tend to gear toward educating and benefiting all in the community, rather than just the homeowners or residents in their portfolio. For example, SCLT in Rhode Island engages in publicly available youth employment and children’s summer learning programs, farmer training workshops and apprenticeships, and hands-on training in food preparation and food growing (Southside Community Land Trust n.d.). Other CLTs may hold publicly available classes introducing the CLT model or educating on the home-buying process in venues like the public library. Most CLTs today also have an online presence through a dedicated website or social media, where they may provide resources or communicate updates to the public and other interested parties.

CLT as Cultural Commons

Finally, in this section we explore the unique sense of community that acts as another shared resource within a CLT. In Labor and/as Love: Roller Derby as Constructed Cultural Commons, David Fagundes (2014) states:

community that roller derby provides can be regarded as a commons as much as shared knowledge about derby can. Fellowship is a nonrivalrous, incorporeal resource that is nonrivalrous and intrinsically nonexcludable, but is rendered excludable in that it is limited to those who are part of the relevant insular community (i.e., the roller derby world). Moreover, the sense of kinship that derby provides is something that its participants want to get out of their experience. In this sense, then, community is a resource that derby enables its members to extract.

This concept of fellowship also manifests itself among CLT homeowners in an unexpected way. One of the few studies done on what “community” means to CLT members found that few meaningful or long-term relationships form between residents of a CLT. After an individual completes the homeownership process and becomes a resident of the CLT, many just want to live their lives, rather than becoming more involved with the CLT. There is also not much interest in getting to know the other residents of a CLT, nor do they feel an affinity with other current residents (Kruger et al. Reference Kruger, DeFilippis, Williams, Esfahani, Martin and Pierce2020).

However, there was a nontraditional form of “community” that emerged within the studied CLTs: between the current homeowners and the CLT organization and future homeowners. “For homeowners, community was often defined as the ability of the CLT organization to provide the engagement and stewardship that will contribute to the long-term success and stability of the low-income homeowner through the challenges of homeownership” (Kruger et al. Reference Kruger, DeFilippis, Williams, Esfahani, Martin and Pierce2020, 649). The relationship is built through providing the types of stewardship activity described above, which help homeowners feel cared for by the CLT and feel secure in their homeownership, and also believe that the CLT will continue to exist and help future residents. In turn, this relationship of care and trust forms the basis of a kinship between present-day CLT homeowners and the future homeowners who will eventually occupy this land, and a responsibility to those individuals “of ensuring that said property would be taken care of so that a future family could enjoy the benefits of homeownership in the same manner that they are currently” (Kruger et al. Reference Kruger, DeFilippis, Williams, Esfahani, Martin and Pierce2020, 651).

By being a part of a CLT, many residents “derive satisfaction in knowing they – as CLT homeowners – can also care for and steward the future” (Kruger et al. Reference Kruger, DeFilippis, Williams, Esfahani, Martin and Pierce2020, 653). This unique feeling is like that described by Fagundes earlier – the sense of responsibility and kinship to future homeowners is a resource that CLTs enable its residents to gain.

This is because it is the proactive efforts of CLT staff and the management team that creates the sense of community toward future homeowners in the CLT managed community. The sense of community is not endogenously created through the homeowners interacting among themselves; rather it originates from the care and trust that homeowners form through interactions with the CLT management team. The ability to create “community” rests with the CLT, and thus may be considered another aspect of a cultural commons within the CLT model.

Conclusion

This chapter explored various aspects of CLTs, focusing on how this model effectively functions as an ownership structure for commons. Our parallel analysis on a CLT’s physical and cultural commons draws on Elinor Ostrom’s work on the governance of material resources, as well as information theory and the Governing Knowledge Commons framework. This work contributes to existing knowledge commons scholarship using CLTs as a unique case study of community property governance and knowledge commons management, and enables the CLT community and practitioners to better understand current practices by providing research and analysis in those areas where academic literature is scarce to nonexistent. Collective property rights and governance mechanisms are critical, but so are the types of strategies that serve as the bridge between the structure and its ability to overcome social dilemmas, given the communities’ needs and goals.

The CLT is a nonprofit, communally owned land management organization that employs a governing board to act as a long-term steward of its land by leasing it to private homeowners and other community-based organizations. This distinctive resource management structure is driven by the goal of benefiting all the people living in a localized community – particularly financially vulnerable individuals and traditionally underserved groups. However, the analysis reveals how this management structure also faces many challenges to align the motivations of the CLT board with the very people that the CLT exists to serve in order to achieve an optimal community land stewardship arrangement.

For example, while common ownership of land legally creates a variety of helpful restrictions that prevent real estate speculators from driving up property prices, it can also decrease the financial incentives of lessees to efficiently invest in preserving and improving the land upon which they reside. Additionally, the governing CLT boards typically have representation from the homeowners and other stakeholders from the area to better serve the needs of the local community. Yet these same boards also depend on public and private contributors to financially sustain their operations, which makes them potentially beholden to the influences of entities outside the community. Moreover, the focus on housing and the ground lease structure can limit the potential of the CLT to manage its property more effectively for the benefit of the local community.

This land commons management structure creates additional challenges for the CLT board that arise from both an information commons and a cultural commons. First, CLTs rely on interorganizational information flows where knowledge sharing creates greater efficiencies. This includes valuable advice on designing and executing various intraorganizational processes that exploit this common knowledge and expertise.

Second, a culture has been created between existing CLTs around the country that has produced many examples of endogenous mutual support in this information-sharing effort, including examples of mutual encouragement between separate CLT management teams to address overwhelming challenges, such as the Covid-19 pandemic. Yet this contrasts with the culture that has developed between the CLT board and the private homeowners and other lessees residing on CLT lands. Many empirical observations indicate that an edifying culture results only after proactive engagement is implemented by CLT management, specifically actions that invest in the ongoing success of the homeowners and the other lessees.

Ultimately, there are many real-world success stories of CLT organizations achieving the very goals they were designed to fulfill. These organizations have chosen this management structure to serve local communities better in ways that are not possible through traditional private landownership, and they have overcome the difficult challenges inherent in managing a common pool resource. A greater understanding of how CLTs have surmounted these challenges can assist future efforts to establish new CLT organizations.

Introduction