Then it was autumn.

1 A Brief History of the Concept of Dementia

1.1 Earliest Historical Traces of Dementia

The earliest references to dementia were discovered in an ancient Egyptian text written in the twenty-fourth century BCE. Even though it is not a medical record, the text describes clearly in hieroglyphs the situation of Ptah-Hotep, who was a vizier during the Fifth Dynasty of Egypt. According to the text, Ptah-Hotep spent every night becoming more ‘childish’. His inability to remember yesterday was also noted. Progressive behavioural changes as well as memory decline suggested that Ptah-Hotep was developing a dementia syndrome [Reference Smith, Atkin and Cutler1]. Ironically, he was highly esteemed for writing maxims, early Egyptian ‘wisdom’ literature, that instructed young men on appropriate behaviour and promoted self-control instead of childishness. The next identified reference to dementia or mental decline in old age was in the writings of classical authors.

1.2 Transition from Age-Related Senility to Dementia

Papavramidou [Reference Papavramidou2] studied ancient Greek and Byzantine writings from the seventh century BCE up to the fourteenth century CE in order to examine how people viewed ageing, senility or dementia in the classical era. She studied literary texts as well as scientific manuscripts and concluded that the history of dementia may be divided into two periods distinguishing between different types of ontologies associated with mental decline, the period before and after Posidonius in the late second to the early first century BCE (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Scholars addressing senility and dementia in the Greco-Roman period

In the first period, authors mainly refer to dementia or senility as a condition brought forward by age. Indeed, already in the seventh century BCE, Pythagoras proposed that old age came with mental derangement. Specifically, a regression of mental faculties began at age 60 and by the age of 80 one would have reached a state of ‘imbecility’ or ‘infancy’. Two centuries later, Hippocrates referred to a similar phenomenon using the term ‘morosis’ (becoming a child) as a decline in the intelligence associated with ageing. Plato and Aristotle explained this decline as a result of bilious ‘humours’ or excessive black bile that was trapped in the body in old age and hence led to forgetfulness and reasoning problems.

However, in the second period, starting with Posidonius in the late second to the early first century BCE, there was a differentiation of the medical ontologies relating to dementia. Posidonius was the first to separate dementia due to old age (‘leros’) from dementia due to other causes (‘morosis’). In a similar vein, Cicero – second century BCE – noticed that not all older people developed ‘senile imbecility’, only the ‘weak’. According to him, an active mental life could offer the possibility of postponing senility. In the centuries that followed, many causes for dementia were described. Galen in the late first to the early second century CE clarified that a little humidity adding to cold in the brain was the main reason for morosis, as this mixture leads to inertia of the brain. Aretaeus in the second century CE referred to morosis occurring when melancholia aggravates. Psellus in the eleventh century and Actuarius in the thirteenth to fourteenth century CE wrote that cold and humidity specifically affect the ventricles of the brain, thus causing morosis. These concepts and ideas were maintained for several centuries as during the ‘dark’ Middle Ages, advances in understanding of dementia halted abruptly. Even though people were undeniably afflicted by dementia in this period, no relevant written sources are known.

According to Berchtold and Cotman [Reference Berchtold and Cotman3], the next notable step in understanding dementia after the classical period was taken in the early 1600s during the Enlightenment. The English philosopher Francis Bacon wrote a book entitled Methods of Preventing the Appearance of Senility in which he noted that old age is the home of forgetfulness. In the second part of the seventeenth century, different types of dementia were characterized by Thomas Willis (1621–75), who was the personal doctor of Charles II. In his book Practice of Physick, he suggested that dementia might result from: (1) congenital factors, (2) age, (3) head injury, (4) disease or (5) prolonged epilepsy.

Only in the eighteenth century was ‘senile’ dementia considered distinct from usual ageing since the emerging new science of post-mortem study had shown that people with this condition had smaller brains than their healthy counterparts [Reference Fotuhi, Hachinski and Whitehouse4].

1.3 Biomedical Model with Alzheimer’s Disease as the Public Face of Dementia

In the 1890s, Alois Alzheimer and Otto Binswanger extensively described the critical role of atherosclerosis in the development of brain atrophy and coincident senile dementia. A decade later, Alzheimer was the first to discover specific changes in the brain that might be associated with symptoms of dementia. He studied a relatively young woman, Auguste Deter, who displayed progressive personality changes, confusion, suspiciousness towards her husband and hallucinations. Afterwards, pronounced memory problems occurred [Reference Cipriani, Danti and Carlesi5]. After her death at age 56, Alzheimer investigated changes in her brain post-mortem and found senile plaques that had been observed before only in older people, and first described neurofibrillary tangles. He reported on this in a case study entitled ‘About a Peculiar Disease of the Cerebral Cortex’ in 1907 and gave a lecture that received little attention.

For most of the twentieth century, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) was considered a rare condition that affected mainly younger people and caused ‘pre-senile’ dementia. Hardening of the blood vessels, on the other hand, was considered a major contributor to cognitive decline in late life. Moreover, the causes for hardening of the blood vessels were sought in the organization of society that forced seniors to become inactive and isolated. According to Rothschild and many other psychiatrists, reduced stimulation of the brain was believed to result in cognitive deterioration [Reference Fotuhi, Hachinski and Whitehouse4].

A shift occurred in the early 1970s when studies of large numbers of post-mortem brains of older individuals observed extensive senile plaque loads that correlated with the clinical occurrence of dementia [Reference Blessed, Tomlinson and Roth6]. This shifted the field to attributing senile dementia to ‘Alzheimer’ pathology as opposed to vascular pathology and brought forward the term ‘senile dementia of the Alzheimer’s type’, later to be replaced by AD irrespective of age, although early-onset (i.e. before the age of 65) and late-onset AD do have some different clinical features.

While recognition that senile plaques contain an amyloid protein was first proposed by Bielschowsky [Reference Bielschowsky7], the insoluble nature of the deposited protein made biochemical characterization difficult. With advances in molecular techniques in the 1980s, it was possible to sequence the amyloid protein and then clone the encoding gene, the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene. The APP gene is located on chromosome 21, which aligned with the observation that trisomy 21 (Down’s syndrome) individuals universally develop AD pathology by their early 40s with most also developing dementia. Subsequently, mutations in the APP gene were identified in autosomal dominant early-onset AD and soon after in presenilin genes that influence APP processing. This led to the formulation of the amyloid cascade hypothesis that postulated that the primary pathology is in amyloid deposition, which then leads to neurofibrillary tangles, synaptic dysfunction, neuronal loss and symptoms. Alzheimer’s disease thereafter remained the ‘face’ of dementia for a long period. However, increasingly, it has become clear that there are many ‘faces’ of dementia and many degenerative illnesses that trigger cognitive decline or behavioural changes and subsequent dementia.

1.4 The Current Definition of Dementia

Dementia is a condition that may be caused by a wide range of diseases. Specifically, dementia is defined as a clinical syndrome of global cognitive decline affecting one or more cognitive domains, including complex attention, learning and memory, language, executive function, perceptual motor function and social cognition. The cognitive decline is severe enough to cause loss of independence by impairing the capacity to perform instrumental and/or basic activities of daily living. Individuals with dementia may experience difficulties that are so pronounced that they cannot live independently and over time become fully dependent on others.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia, accounting for approximately 60% of all dementia diagnoses either alone or in combination [Reference Schachter and Davis8]. However, many diseases are associated with dementia. The most recent (fifth) edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) replaces the term ‘dementia’ with ‘major neurocognitive disorder’ (NCD) and also distinguishes between acquired and developmental NCD, although many of the conceptual challenges are common to both [9].

1.5 The Spectrum of Cognitive Decline

In older people, dementia can be conceptualized as a syndrome encompassing advanced cognitive and functional decline, representing one end of a loose continuum ranging from ‘usual’ ageing to subjective cognitive impairment, mild cognitive impairment and finally dementia [Reference Knopman, Beiser, Machulda, Fields, Roberts, Pankratz and Petersen10].

Usual – as opposed to ‘normal’ – cognitive ageing is characterized by reduced mental speed and less working memory capacity, leading to difficulties in spontaneous recall, less ability to multitask, slower organization and the appearance of greater indecision. These changes typically do not interfere with the level of functioning in an individual and do not cause distress. Subjective cognitive decline (SCD), on the other hand, refers to an experience of cognitive failing that is distressing to the individual. Subjective cognitive decline is not a universal aspect of ageing, and it should be noted that many individuals with dementia do not perceive and are not distressed by their cognitive impairment. There are several possible causes of SCD. For some individuals, the experience of deteriorating cognitive skills might be a first signal of a pathological process that has not yet been detected in neuropsychological testing or brain imaging. For others, these distressing subjective changes may not reflect brain pathology, but rather result from a tendency to be introspective or to value cognitive functioning more than other domains of functioning. For yet others, this might reflect experiences resulting from depression, sleep impairments or alcohol use.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is different from SCD because cognitive decline, beyond what might be expected from usual ageing, is present but does not impair functioning enough to be dementia. These alterations are detected in neuropsychological testing and others also notice a change in functioning [Reference Petersen, Caracciolo, Brayne, Gauthier, Jelic and Fratiglioni11]. Still, a person with an MCI can function at a high level and continue to live independently. Clinicians distinguish single-domain and multiple-domain MCI, as well as amnestic and non-amnestic MCI. These all have different prognoses, although with enough time most individuals with MCI develop different types of dementia, which is why MCI is often referred to as a dementia ‘prodrome’ [Reference Busse, Hensel, Guhne, Angermeyer and Riedel-Heller12, Reference Ganguli, Snitz, Saxton, Chang, Lee, Vander Bilt and Petersen13]. For instance, an amnestic, multiple-domain MCI may result in Alzheimer’s dementia more often than a non-amnestic, single-domain MCI [Reference Fischer, Jungwirth, Zehetmayer, Weissgram, Hoenigschnabl, Gelpi and Tragl14]. In contrast, non-amnestic MCI appears more likely to be a prodrome for non-Alzheimer’s dementia.

Dementia, finally, represents the most severe form of decline, in which a person is no longer able to function independently, with the term ‘de-mentia’ referring to the loss of mind. As is common in this ‘medical’ discourse, the most important discriminator of dementia from MCI or usual ageing is in the functional and social domain, referring to the possibility to function day to day independently or need support from others.

While there have been considerable scientific advances in understanding the pathogenesis of the several dementia aetiologies, many challenges remain. First, the distinction between a disease, referring to the underlying pathology, and a syndrome, referring to the impact a disease has on the experience and functioning of an individual, often remains troublesome to clinicians as well as to patients and their families. As a result, people are unsure concerning the prognosis of a condition, or which types of symptoms can be understood as a part of the disease and which symptoms might represent a psychological reaction to disease symptoms. Another issue is the current focus on early detection of diseases, even in the presymptomatic phases. Often, to people in whom a vulnerability to develop a certain disease has been detected, such a vulnerability is implicitly considered a first stage in the disease process [Reference Chen, Ratcliff, Belle, Cauley, DeKosky and Ganguli15]. Even to clinicians or researchers, this distinction is not always clear. This may cause unnecessary distress, even more so as there is currently not yet a cure for the neurodegenerative causes underlying dementia.

To add to the confusion that sometimes arises from the different names that exist for a condition characterized by progressive cognitive decline, the latest version of the DSM-5 has utilized an alternative categorizing system to refer to cognitive impairment [9]. As mentioned earlier, the manual distinguishes between mild and major neurocognitive disorders corresponding with MCI and dementia, respectively. Indeed, dementia was considered as a stigmatizing label that needed to be replaced by a more neutral reference to the symptoms that are observed [Reference Blazer16, Reference Rabins and Lyketsos17]. However, there was no clear consensus on the use of the terms ‘major’ and ‘mild’ neurocognitive disorder [Reference Rabins and Lyketsos17, Reference George, Whitehouse and Ballenger18].

2 Broader Models of Dementia

2.1 Challenges to the Traditional Medical Model

The development of a biomedical model has certainly advanced the approach to dementia. In previous centuries, largely devoid of scientific medical knowledge, individuals with symptoms of dementia such as disorientation or hallucinations were at risk of being persecuted for witchcraft; they were stigmatized and often isolated. Also, old age was often unconditionally associated with senility.

Fortunately, biomedical research has enlightened some of the pathogenic mechanisms behind dementia, hence making it an identifiable disease that does not warrant punishment or exorcism. Instead a treatment is required whereby the primary focus is on reversing impairments by means of ‘medical-somatic’ therapy or pharmacotherapy. Still, the application of a bygone biomedical model aimed at curing impairments caused by an illness has been limited as there is no cure for many of the neurodegenerative causes of dementia and quite often there are few effective pharmacological treatments of burdensome disease symptoms such as memory loss and disorientation [Reference Jones, Hungerford and Cleary19]. Finally, neurobiological changes can explain only some of the considerable variety that is observed in individuals with dementia, with little conformity to any predetermined stage-like progression.

Hence, an excessively narrow application of the medical model risks minimizing the psychological and social sequelae of the disease, especially its effects on a person’s experience of and reaction to certain symptoms. It also carries the risk of limiting the therapeutic potential of interventions focussing on the social environment by underappreciating the role of caregiving in patient outcomes.

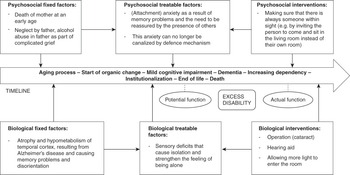

Fortunately, in the 1970s, treatments were also starting to focus on the consequences of dementia, concentrating on how to deal with impairment, the reorganization of the living environment and social environments. Also, psychosocial care gradually gained importance, defined as the treatment of psychological and behavioural symptoms that occur when an individual tries to cope with or adapt to the limitations caused by dementia (see Figure 1.2) [Reference Taft, Fazio, Seman and Stansell20–Reference Finnema, Droes, Ribbe and van Tilburg21]. This treatment aims to support the person with dementia and their family and thus increase well-being.

Figure 1.2 Different perspectives in the treatment of dementia [Reference Jones, Hungerford and Cleary19]

2.2 Biopsychosocial Models of Dementia

A treatment that encompasses all three perspectives and that considers interventions focussed on cure, rehabilitation and support as complementary is the biopsychosocial model, which was introduced in 1977 by the internist and psychiatrist George Engel at Rochester University Medical Center in the USA [Reference Engel22]. He stated that to understand the full impact of an illness and treat it adequately, one should not just consider biological factors, but also personal and social factors of the individual with the illness.

In the 1980s and 1990s, many researchers developed biopsychosocial models that focus specifically on psychogeriatric care and dementia. A review by Finnema et al. [Reference Finnema, Droes, Ribbe and van Tilburg21] describes among others the dynamic systems analysis (DSA) model, utilizing a system-theory perspective in which complex interactions are emphasized instead of ‘simple’ and linear relationships. Hence, treatment of symptoms coinciding with dementia is based on the understanding of symptoms as the result of an interaction between somatic disease, cognition, personality, communication, the social environment and life history. Changes in any of these factors may have a therapeutic effect by altering the interaction.

Many practical applications exist of such biopsychosocial models. For instance, a major success in the USA is the person-centred, individualized Maximizing Independence at Home (MIND at Home) approach, which was developed in 2006 at Johns Hopkins University; it derives from an assessment of the individual needs of persons with dementia living at home, along with those of their caregivers [Reference Rabins, Lyketsos and Steele23–Reference Samus, Johnston, Black, Hess, Lyman, Vavilikolanu and Lyketsos24]. It accounts for psychosocial determinants of health and behaviour and appreciates the importance of individual psychology in the development of illness and the central role of non-pharmacological therapies in improving clinical outcomes and quality of life. The assessment leads to a tailored set of interventions to address these needs using continuously evolving, evidence-based protocols. The MIND approach has been shown to delay transition from home to a nursing home, improve life quality and reduce care burden and healthcare costs.

Similarly, in the UK, Spector and Orrell [Reference Spector and Orrell25] have developed a biopsychosocial approach which can be used as a tool for understanding individual cases (see Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 Case illustrating the biopsychosocial approach of Spector and Orrell [Reference Spector and Orrell25]

In this illustration, a 75-year-old person with Alzheimer’s dementia is admitted to hospital as a result of increased anxiety and the need to constantly be with the partner, who reports a great care burden. Psychologically, there are events in the past that cannot be changed. The man lost his mother at an early age. Additionally, his father was unable to be responsive and care for his son, as he was experiencing a complicated grief process himself. Biologically, AD causes disorientation and memory problems. Therefore the environment is often unfamiliar, which causes anxiety, and the man seeks reassurance through proximity of carers. At home, this is usually the partner. Finally, sensory deficits increase feelings of being isolated and alone. Interventions can be aimed at reducing this feeling of loneliness and hence decreasing levels of anxiety. Specifically, proximity to others may be promoted, and sensory function may be ameliorated. Feelings of anxiety may hence be reduced. In some cases, however, when other interventions appear insufficient, pharmacological treatment can be indispensable to alleviate symptoms. The biopsychosocial model illustrated summarizes the disease process (using a timeline), fixed and changeable psychological or biological factors. It encourages that dementia is recognized as something which is flexible, allowing for change, adaptation and improvement. The discrepancy between potential and actual function can be diminished, leading to less ‘excess’ disability. In some cases, this can postpone institutionalization and promote well-being. Preliminary research has already shown the benefits of applying such a model as this leads to a greater understanding of individuals with dementia and an improvement in caregivers’ abilities to develop interventions. Caregivers also report feeling more knowledgeable [Reference Revolta, Orrell and Spector26].

Obviously, many more approaches in Europe and worldwide have proven their value as interventions that successfully concentrate on the well-being of the individual with dementia and their caregivers by focussing on disease symptoms, consequences and psychosocial factors. Interestingly, there are also different psychosocial models used in dementia care, derived from more general theoretical frames, such as the attachment theory, psychodynamic models or crisis and coping models. The majority of the research on biopsychosocial models in dementia, however, involves the person-centred approach, originally introduced by Kitwood [Reference Kitwood27]. We first discuss the person-centred approach to dementia care and then briefly describe some of the other psychosocial models that have been developed.

2.3 Person-Centred Models of Dementia

I had become the guardian not only of George’s medical history but also of the story of his life, a story that was increasingly difficult for him to articulate and of which it seemed that I alone knew many of the facts. Experiences, feelings, all kinds of memories from six decades of lived life, somehow all this had come into my keeping.

Kitwood [Reference Kitwood29] proposed an integrative and dialectical framework for dementia. In order to visualize the model, he used a simple equation:

In the equation, D stands for dementia, P for personality, B for biography, H for physical health, NI for neurological impairment and SP for social psychology.

There is a primary focus on the experience of an individual with dementia. In particular, person-centred models aim to understand how identity is formed and how it can be maintained in individuals with dementia. Kitwood and Bredin [Reference Kitwood and Bredin30] believe the psychological ‘self’ has the potential to survive long into the illness. Hence, they looked at what a person with dementia needs and suggest that it is (1) love, (2) comfort and trust that comes from others, (3) attachment and a sense of familiarity when individuals with dementia so often feel as though they are in a strange place, (4) to be included in care and in the lives of others, (5) to be involved in the processes of normal life and have sources of fulfilment and, finally, (6) to have an identity related to personal history and preferences that distinguish them from another person and make them unique [Reference Kitwood27, Reference Mitchell and Agnelli31].

According to Sabat and Harré’s [Reference Sabat and Harré32] social constructionist view, there is a personal singularity, a private self, that remains intact throughout the illness despite the debilitating effects of dementia (see Chapter 3). However, there is also a ‘public’ self or selves that can be lost indirectly as a result of the illness. In particular, negative social interactions can bring forth a detrimental effect on the sense of identity and well-being of a person with dementia. Kitwood [Reference Kitwood27] also delineated 17 types of ‘malignant’ social interactions which can lead to a diminished sense of self and self-worth (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 ‘Malignant’ social psychology developed by Kitwood [Reference Kitwood27]

| Type | Definition |

|---|---|

| Treachery | Use of deception to distract or manipulate |

| Disempowerment | Not allowing someone to use abilities that one still has |

| Infantilization | Treating someone like a child |

| Intimidation | Causing someone to feel frightened as a result of verbal threat or physical power |

| Labelling | Referring to people inappropriately by using a term that describes and classifies them (associated with concepts of self-fulfilling prophecy or stereotyping) |

| Stigmatization | Treating someone as if they were an outcast |

| Outpacing | Providing information or asking questions/offering choices too quickly so information becomes difficult to understand or questions become impossible to respond to adequately |

| Invalidation | Not acknowledging the reality or experience of a person |

| Banishment | Excluding someone physically and/or emotionally |

| Objectification | Treating someone as an object (e.g. during washing, clothing etc.) |

| Ignoring | Talking about someone in their presence as though they are not there |

| Imposition | Forcing someone to do something |

| Withholding | Failing to provide attention or to fulfil an obvious need |

| Accusation | Blaming someone for their inability or misunderstanding |

| Disruption | Suddenly disturbing a person and interrupting their activity, speech or thought |

| Mockery | Making fun or joking at the expense of someone |

| Disparagement | Telling someone that they are worthless |

Snyder [Reference Snyder33] illustrated how negative social interactions may impact the well-being and ‘personhood’ of individuals with dementia. She describes how patients experienced being informed about their diagnosis by a neurologist and found that many had the impression that there was no compassion, no regard for or interest in the feelings of the individual who received a diagnosis, leading to an experience of being depersonalized by the healthcare professionals rather than feeling cared for. Snyder [Reference Snyder33] speculated that perhaps these healthcare professionals were not uncaring, but they might have been inclined to position the person with dementia wrongly as someone who, because of the illness, cannot engage in a discussion about what the diagnosis means to him or her.

Case

Doctor: How are you today?

Person with dementia: I am alright, but I need to get home. My children need to be picked up from school. Can someone show me the way out?

Doctor: There’s no need for that. Your children are at home. You are in hospital. We will take care of you.

Person with dementia: I don’t need to be taken care of. It’s my children that need taking care of! Who can let me out? [Walks impatiently towards the exit and then towards the nursing station.]

Doctor: Has she been agitated all afternoon?

Nurse: Yes, we’ve tried to distract her, but she doesn’t want any coffee …

This conversation illustrates how individuals with dementia are sometimes subtly and involuntarily excluded from conversations, not taken seriously, and hence isolated in their experience. In some cases, this means that activities are taken over unnecessarily and decisions are made for the person with dementia without involving him or her. Specifically, in this example, the doctor addresses a nurse when the person with dementia is still present and talks about her behaviour as though she was not there. She is treated as someone who needs help from others rather than as a concerned mother who wants to take care of her children. She feels misunderstood. This interaction causes further distress rather than being reassuring.

The opposite of malignant social psychology, according to Kitwood, is positive person work [Reference Kitwood27]. It consists of 12 different types of behaviours and may lead to improvement of the condition, referred to as ‘rementia’ (see Table 1.2) [Reference Kitwood27, Reference Epp34].

Table 1.2 Positive person work as developed by Kitwood [Reference Kitwood27]

| Type | Definition | |

|---|---|---|

| Social interactions | Recognition | Being recognized as a person with unique thoughts, feelings or preferences |

| Negotiation | Consulting with someone about their preferences and if possible involving them in decision-making | |

| Collaboration | Promoting partnership between the healthcare professional and the person with dementia in carrying out an activity | |

| Play | Providing activities that stimulate self-expression and enjoyment | |

| Timalation/stimulation | A form of interaction that stimulates the senses (e.g. massage or aromatherapy) | |

| Celebration | Celebrating special occasions such as an anniversary or an achievement | |

| Relaxation | Offering a low-level intensity of stimulation and providing personal comfort | |

| Psychotherapeutic interactions | Validation | Acknowledging someone’s emotions and feelings and responding to them |

| Holding | Creating a safe psychological space by containing distress and allowing self-revelation | |

| Facilitation | Enabling a person to do what he or she would otherwise be unable to do; stimulating the use of remaining abilities rather than pointing out errors | |

| People with dementia can take a leading role in | Giving | Person with dementia presents him or herself in a positive, helpful way |

| Creation | Individual is stimulated to be creative and offer something to the interaction spontaneously |

One example of positive person work is recognition, which occurs when someone thanks a person with dementia, affirms his or her views or greets him or her with his or her preferred name. Another form of positive person work is play – for instance, when individuals with dementia can undertake activities that engender spontaneity, self-expression, giving and enjoyment, such as a gardening session in which they can explain to the therapist how to tend to a plant. In line with the effect that Kitwood [Reference Kitwood29], predicted Macrae [Reference Macrae35] found no loss of self or personhood in a small group of Canadian individuals with AD who were surrounded by supportive caregivers, with little evidence of negative social interactions. Individuals led meaningful lives and they were not concerned with the loss of their identity. Hence, indirectly, this study could support the hypothesis of how the absence of malignant social psychology and the presence of positive person work may reduce threat to the ‘self’ or ‘selves’ and promote well-being [Reference Kitwood29].

Other researchers have also looked at possibilities for strengthening a person’s sense of self-worth and identity. Harrison [Reference Harrison36], for instance, suggested that caregivers try to look at the individual with dementia within the context of this person’s life, which may help strengthen a feeling of continuity and hence preserve personhood. A recent systematic review found that reminiscence and life story work – which is not restricted to the recollection of memories, but also concerns an evaluation and reappraisal of the life course – are important interventions in trying to understand a person’s biography and in stimulating a sense of identity [Reference Johnston and Narayanasamy37].

However, there are some criticisms of the personhood notion proposed by Kitwood [Reference Kitwood29] and Sabat and Harré [Reference Sabat and Harré32]. In particular, Kontos [Reference Kontos38] states that the body should be given an active and agential role in the constitution and manifestation of selfhood as it is a substantive means by which individuals with dementia engage in the world and in which agency is not derived from a cognitive form of knowledge. She refers to an ‘embodied selfhood’ that has the potential to improve dementia care when it is better understood, and hence needs to be explored further in empirical research. In a similar vein, Fazio and Mitchell [Reference Fazio and Mitchell39] studied the persistence of ‘self’ in AD using visual recognition of the body. Even though individuals did not remember a photographic session that occurred a couple minutes earlier, there was an unimpaired self-recognition of themselves on the pictures taken, suggesting that the body is an essential element in the maintenance of a sense of ‘identity’ [Reference Fazio and Mitchell39].

Irrespective of the definition of personhood and self, the person-centred approach to dementia has been broadly applied and it has evolved over the years – for example, the Values-Individualized approach-Perspective taking-Social environment or ‘VIPS’ framework developed by Dawn Brooker [Reference Brooker40] and applied by Rosvik et al. [Reference Rosvik, Kirkevold, Engedal, Brooker and Kirkevold41]. There have been several literature reviews looking at commonalities in the models and practices derived from the concept of ‘person-centred care’, leading to a general conclusion that personal choice and autonomy are of great importance [Reference Kogan, Wilber and Mosqueda42]. In the most recent review, Fazio, Pace, Flinner and Kallmyer [Reference Fazio, Pace, Flinner and Kallmyer43] concluded that, even though there is no consistent and clear statistical proof of the impact of person-centred care, there is sufficient evidence to warrant six recommendations. First of all, it is important to know the person living with dementia as a unique person who supersedes his or her diagnosis. Second, it is important to accept the person’s reality, thereby promoting effective and emphatic communication. Third, it is important to identify and support ongoing opportunities for meaningful engagement, related to earlier or new interests and preferences, and to stimulate the experience of joy and purpose in life. Fourth, it is important to build and nurture authentic, caring relationships. People with dementia need to be connected and treated with dignity and respect. Also, it is important to create a supportive community for individuals, family and staff. This allows for comfort and creates opportunities to celebrate accomplishments. Finally, care practices need to be evaluated regularly and changed if necessary.

2.4 Psychological Adaptation-Based Models of Dementia

When models focus on individual psychology and specifically on coping of the person with dementia in order to explain behaviour or mood symptoms, they may be referred to as ‘psychological adaptation-focussed’ models of dementia.

In the psychodynamically inspired model of Hagberg [Reference Hagberg, Miesen and Jones44], for instance, personality-related symptoms are considered one of the most sensitive indicators of the onset of dementia. In particular, the development of defence mechanisms is hypothesized to depend on cognitive maturation. Defence mechanisms are conceptualized as ‘mediators’ in conflicts between the individual’s needs and environmental requirements. Rather than immediately showing feelings of frustration or anxiety, as they age, individuals become more efficient in channelling conflicts between their own needs and limitations in fulfilling these needs that are induced by the environment. Cognitive development and maturity is thought to solidify these strategies and, given intact cognition, the ‘solutions’ are believed to become more and more sophisticated. As dementia primarily affects cognition, defence mechanisms will change or become inefficient. This, in turn, can become evident in behavioural changes in a person with dementia. Changes are twofold, according to Hagberg [Reference Hagberg, Miesen and Jones44], as the author suggests that there may be regressive behaviour on one hand and a shift in the dynamics from a conflict-free sphere to a conflict area on the other. Lack of defence strategies could uncover anxieties that are overwhelming for the individual with dementia and have to be dealt with by family or healthcare professionals. Hence, the kind of behaviour that becomes evident as a result of failing defence mechanisms may feel childlike to the social environment.

Another model that is in essence an interactive psychodynamic model is the adaptation-coping model. This model is also concerned with understanding the person’s adaptation to the consequences of living with dementia and the influence the relationship with the social and physical environment can have on this process, in addition to personal history and disease-related factors. According to the adaptation-coping model [Reference Finnema, Droes, Ribbe and van Tilburg21, Reference Brooker, Droës and Evans45], which was based on the coping theory of Lazarus and Folkman and the crisis model of Moos and Tsu, living with dementia demands fulfilling certain adaptive tasks, such as dealing with increasing disabilities, developing an adequate care relationship with caregivers, preserving an emotional balance and positive self-image, maintaining social relationships and coping with an uncertain future. When the coping is less adequate, behavioural and mood symptoms can develop. Also, when the person is unable to cope with one or more adaptive tasks, he or she can even end up in a crisis. Support is therefore based on an individual psychosocial diagnosis which indicates the tasks and context in which the person experiences difficulties or distress, as shown by behaviour and mood disruptions and the defence and coping strategies he or she uses to maintain emotional balance. The three strategies to support the cognitive/practical, social and emotional adaptation are reactivation, resocialization and optimizing the emotional functioning, respectively. The subsequent concrete action plan consists of relevant psychosocial interventions, varying from cognitive stimulation activities, music therapy, art therapy and psychomotor therapy to reminiscence, and depends on the personal preferences and cognitive and functional abilities of the person.

A final model concerning the understanding of behaviour of people with dementia as an expression of their needs and as a manner in which they hope to fulfil these needs has been inspired specifically by a combination of ethology, psychodynamic theory and psychiatry. Attachment theory, originally conceived of by the psychiatrist John Bowlby [Reference Bowlby46] in the context of behaviour displayed by children towards their parents, was used as an explanatory model in understanding ‘parent fixation’ in individuals with dementia [Reference Miesen47]. Attachment behaviour consists of all efforts to gain proximity to a primary caregiver or attachment figure in order to experience feelings of safety, warmth and security. It is especially prominent in stressful situations. Based on his clinical experience and behavioural experiments, Miesen [Reference Miesen47] found that almost every older adult with dementia, at some point in the disease process, develops the conviction that his or her parents are still alive and some also experience the desire to find them (referred to as ‘parent fixation’), leading to ‘wandering’ or emotionality. He interprets this behaviour as a need for security while being confronted with the many losses, disorientation and anxiety that are the result of the disease. Interestingly, empirical research showed that a staff training in attachment theory resulted in an increased awareness of emotional needs of residents and at the same time in a reduction of anxiety and distress in these residents [Reference Dröes, van der Roest, van Mierlo and Meiland48]. More in general, a homelike, familiar and secure environment seems crucial to promote well-being in individuals with dementia.

2.5 Environmental Adjustment-Focussed Models of Dementia

When the focus lies specifically on adjustment of the social or living environment to the needs of a person with dementia, models may be referred to as ‘environmental adjustment focussed’. Hall and Buckwalter [Reference Hall and Buckwalter49], for example, developed the progressively lowered stress threshold (PLST) model. According to them, it is important that the environment of individuals with dementia is adjusted to their cognitive as well as their functional abilities. The model distinguishes four stages in AD, each associated with different levels of stress tolerance further reducing throughout the day, and warranting a different organization of the physical and social environment. Factors that can increase distress throughout the day are fatigue, demands that exceed the capacities of the person with dementia, exposure to overwhelming or conflicting stimuli, emotional reactions to losses, physical stressors and, finally, changes regarding the caregiver, environment or routine.

Similarly, Souren and Franssen [Reference Souren and Franssen50] emphasize that there are four different stages in AD, originally conceptualized by Reisberg et al. [Reference Reisberg, Ferris, de Leon, Franssen, Kluger, Mir and Cohen51], and postulate that each stage warrants a specific approach and environment. In the first phase, there is a loss of planning and initiative, and therefore encouragement is needed. When insight, judgement and motivation reduce in the second phase of the illness, the caregivers need to intervene more actively in order to ensure safety and well-being. The third phase encompasses a loss of learned routine activities and speech, necessitating a partial taking over of activities. In the final phase, with complete loss of spontaneous motor movement, there is a complete taking over of activity.

2.6 Relationship-Centred Care in Nursing Homes

A final framework focusses on relationship-centred care. This approach supersedes the idea of adjusting the living and social environment to the needs of the person with dementia. Instead, in the development of relationship-centred care in nursing homes, Nolan and his colleagues [Reference Nolan, Brown, Davies, Nolan and Keady52] highlighted the importance of staff, carer and the person with dementia all working together. The Senses Framework addressed a sense of security, continuity, belonging, purpose, achievement and significance with the goal of attaining/reaching an enriched environment of care for the person with dementia and for the caregiver [Reference Nolan, Brown, Davies, Nolan and Keady52]. Table 1.3 provides a little more detail on the Senses Framework.

Table 1.3 The six senses [Reference Nolan, Brown, Davies, Nolan and Keady52]

| Sense | Definition |

|---|---|

| Sense of security = to feel safe within relationships | |

|

|

| Sense of continuity = to experience consistency | |

|

|

| Sense of belonging = to feel part of things | |

|

|

| Sense of purpose = to have personally valuable goals | |

|

|

| Sense of achievement = to make progress towards a desired goal | |

|

|

| Sense of significance = to feel that you matter | |

|

|

Importantly, the Senses Framework emphasizes interpersonal processes and experiences from a range of stakeholders, ensuring that a balanced approach to care and decision-making is taken whenever possible.

It is clear that there are many different models focussing on the treatment of dementia and derived from several (psycho)social theories. These models are not mutually exclusive, but are best used alongside each other as they can broaden our perspective and allow us to better tailor our interventions to each person and caregiver individually. Still, there are limitations to the models discussed.

2.7 Limitations and Possible Routes for Further Development of a Biopsychosocial Model of Dementia

First of all, the development of biopsychosocial models have tended to use AD as the exemplar, mainly amnestic AD as the most common type of dementia. The combination of biological and psychosocial models is best understood in this context, and provides powerful approaches to management. Atypical AD and the other dementias, specifically the behavioural variant and semantic variants of frontotemporal lobar degeneration, have been less explored and create particular challenges. For example, in biparietal AD and cortical basal degeneration, the prominent parietal damage can mean that touch becomes unpleasant and individuals may demonstrate rejection behaviour [Reference Warren, Hu, Galloway, Greenwood and Rossor53]. This can negate the advice of Kitwood [Reference Kitwood27] to use massage. The behavioural changes in the behavioural variant of frontotemporal degeneration (bvFTD) and a number of individuals with semantic dementia present another unique challenge for the application of psychosocial models developed for AD. In contrast to the preservation of the psychological self until late in AD as described by Kitwood and Bredin [Reference Kitwood and Bredin30], personality in FTD can be the first change preceding deficits in cognitive domains. Moreover, nosognosia (lack of illness insight) can present a particular challenge in management. Nosognosia is well described in survivors of stroke – for example, Anton syndrome with cortical blindness and lack of awareness of a left hemiparesis, referring to the weakness or the inability to move on one side of the body in right hemisphere strokes in right-handed people. Nosognosia of cognitive deficits also occurs in the dementias – for example, the memory deficit in AD. It appears distinct from denial of cognitive failure that might reflect psychological defence mechanisms, but rather seems related to damage to the neural network that can compute awareness of the deficit. Future biopsychosocial models will need to accommodate not only the rich variety of psychological and social factors, but also variability in the pattern of neurodegeneration.

Still, irrespective of these limitations, as is the case in psychotherapeutic practice in general, an important guideline seems to be that the basis of warm and genuine contact, time and attention, and respecting autonomy and individuality seems necessary in professional dementia care [Reference Wampold54].

3 Anthropological Perspectives on Dementia

It is a mistake to assume that Western classifications, explanations and subsequent decisions concerning treatment of disease are self-evident across the world [Reference Randall55]. There is relatively little knowledge about how disorders of old age are experienced and understood in non-Western settings [Reference Pollitt56]. Yet anthropology emphasizes that knowledge and behaviour are usually logical but highly dependent on a person’s context [Reference Young57]. Hence, in order to fully comprehend the impact of dementia, it is important to gain an idea of the different contexts in which individuals with dementia reside, even more so as social and cultural factors predict recognition of symptoms, help-seeking strategies and caregiving behaviours. Researchers have looked at different types of societies in different areas of the world, such as the USA, Hawaii, Africa, UK, China, India and Japan.

One major difference in perspective that has become evident concerns the level of material well-being and the development of a healthcare system, which was for a long time associated with industrialization. Even though there are differences in levels of ‘acculturation’ as a result of increased migration [Reference Oxlund58], in most underdeveloped nations across the world, knowledge of dementia remains limited [Reference Kehoua, Dubreuil, Ndamba-Bandzouzi, Guerchet, Mbelesso, Dartigues and Preux59, Reference Mushi, Rongai, Paddick, Dotchin, Mtuya and Walker60]. Memory problems or other cognitive symptoms are usually still interpreted as a natural result of ageing. As older people are often highly respected in less developed countries because of the wisdom they can share with younger members of society, people with memory problems are well cared for at home. When the prestige of being an elder decreases, often alongside the level of industrialization or development, neglect becomes more apparent. For instance, in more urbanized regions of sub-Saharan Africa, older adults with dementia are neglected more often than in rural areas because they cannot be productive and provide income [Reference Hashmi61–Reference Braun and Browne62]. Behavioural issues associated with dementia are often more problematic. In some African regions, it is believed that an individual with behavioural problems may be possessed by a demon or affected by a curse, or this person might be suspected of willingly committing a criminal offence [Reference Braun and Browne62]. Hence, people are sometimes put through exorcist rituals or they may be incarcerated for several years, instead of receiving the medical or psychosocial aid they need (see Box 1).

Benin, like other sub-Saharan African countries, is faced with an ageing population. Approximately 4.4% of the population is currently older than 60 years. As a result, the prevalence of old age diseases such as dementia is also rising. Specifically, there is a prevalence rate of 2.3% in the rural areas of Benin and up to 3.7% in urban areas. Hence, people are increasingly confronted with dementia and it is therefore interesting to see how the disease is experienced and conceptualized.

A qualitative study conducted by Josiane Ezin-Houngbe in a few large communities in southern Benin (Porto-Novo, Allada, Comé, Lokossa) included the responses of 30 individuals, and it showed that there was not a single word that refers to dementia. Instead, there were several terms referring to dementia:

‘the spirit has gone into childhood’ or ‘the person has returned to childhood’ (Ayi-yikpè)

‘the disease of old age’ (Kpeykpozon)

‘the person who says things that have no coherence or meaning’ (Numalémalé)

‘the person who speaks to say nothing’ (Gblo-no)

‘a person who forgets, a person whose thinking is unstable’ (Ayifena-No)

Interestingly, dementia was not always considered a disease. Sometimes it was conceptualized as a normal part of ageing. A man is born as a child, grows up and ends up again as a child. Other non-medical causes for dementia were witchcraft or punishment for previous crimes. Indeed, it is believed that a person who has done much harm to innocent souls may be haunted by them in the ‘evening of his or her life’.

Caregiving is mostly done by women, partners or children of the person who is ill. If family members refuse to take on this role, they risk being isolated, scorned and even cursed for it. Whereas female members of the family are usually involved in caregiving, male family members are often responsible for financial contributions to the household. When a parent becomes ill, a woman is expected to leave her own home and take care of her mother or father, which may lead to marital conflicts. Many children solve this problem by taking on a housekeeper.

Josiane Ezin-Houngbe

In Indian American societies, some behavioural or psychological symptoms that coincide with dementia are considered a supernatural gift. Specifically, hallucinations are regarded as communications with the dead (‘those we cannot see’, rather than ‘those who are not there’) [Reference Henderson and Henderson63–Reference Traphagan65]. This interpretation is consistent with the context, as Indian American tribes are convinced that older individuals who are closer to death may have more contact with the deceased.

In ‘developed’ countries such as the USA, UK or China, people are often aware that dementia is an illness that requires medical and psychosocial treatment and that it may be characterized by cognitive as well as psychological and behavioural symptoms. However, there are still differences in the way people with dementia are viewed and treated. One study demonstrated that American society may be more instrumentalist, emphasizing the disability and need for institutionalization associated with dementia, whereas the UK tends to focus more on emotional aspects of the disease. In China, dementia care was usually provided by family, most often the eldest son. However, cultural values are changing, partly as a result of the ‘one child’ policy and the subsequent shift in the demographic reality. Many children are unable to care for ageing parents and meet other demands in life at the same time. In a recent study by Calia, Johnson and Cristea, [Reference Calia, Johnson and Cristea66] a task that requires people to associate freely to the word ‘dementia’ illustrates how dementia has become more of an ‘inconvenience’ to Chinese individuals (see Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4 Results from a free association task with ‘dementia’ as a stimulus across the USA, UK and China, based on results from the study by Calia et al. [Reference Calia, Johnson and Cristea66]

Another difference in the way people are viewed and treated when they display symptoms of dementia across the world is related to the findings displayed in Figure 1.4 and refers to the more individualistic versus more sociocentric orientation of a society [Reference Hashmi61, Reference Chiu and Tsoh67]. Japanese culture is typically described as sociocentric, whereas American culture is often regarded as more individualistic. Some authors argue that these orientations are mutually dependent and dynamically constituting the experiences of one individual within a specific culture [Reference Shimizu68]. One may conclude that, even though there is no clear-cut difference, some cultures have a more individualistic or a more sociocentric orientation and people with dementia appear to be treated differently, in line with the most dominant orientation in one culture. For instance, behavioural problems or increased dependency on others are considered ‘shameful’ in Japan. People have not been able to care for themselves and prevent the development of cognitive decline through exercise. Hence, they become a burden to others. In India, there is a taboo as well. However, this is related to the belief that dementia may be caused by a ‘neglectful family’. Cohen [Reference Cohen69], for instance, describes a situation of a woman who is thought to have become forgetful and disorientated as a result of intergenerational conflict. In particular, her son marrying a foreigner is considered the direct cause of her illness. Behavioural problems are interpreted as the result of neglect, memory loss as the consequence of shock and sorrow. Many doctors view medical treatment as ineffective. Rather, changes in the family might procure improvement in functioning.

In most sociocentric countries, care is provided by the family. Usually female members of the family are responsible for older people who display symptoms of dementia. However, there is one exception. A study that researched caregiving for older people with dementia in Hawaii found that care for older people with dementia is provided by the person the family thinks could care best. This may be a male or female member of the family. He or she receives control over and becomes the ‘coordinator’ of the care. Medical care is only sought when the doctor is a friend or someone the family knows well [Reference Braun and Browne62]. However, the only study on caregiving for a relative with dementia in Hawaii was conducted in 1998, which may mean that the findings do not take into account changes that have taken place in the social structure in Hawaii in the past decades.

Finally, irrespective of the level of development and the individualistic or more sociocentric orientation of society, dementia is seen as a condition that may lead to dehumanization globally. In Japan, for instance, to become a burden without ever being able to reciprocate the care offered may procure the loss of one’s basic humanity [Reference Henderson and Traphagan64]. In Western cultures, on the other hand, cognitive changes that impact autonomy and personal control may result in a similar experience of not being a full human being. Hence, across cultures it seems important to seek out ways in which people with dementia might retain a continued sense of identity and purpose by contributing to society [Reference Ikels70]. The importance of ‘empowering’ individuals with dementia, making them feel in control of their life, as well as valued as a person with a history, cannot be underestimated. The following paragraphs summarize the first steps that have been taken in order to promote empowerment in people with dementia, a feeling of control and safety, primarily looking at the history of dementia care in the UK, where the movement towards social inclusion of individuals with dementia knew an early start and has shown much progress.

4 Societal Perspectives on Dementia: A Movement towards Social Inclusion

We first outline how people with dementia moved from being positioned as those who were considered not to have a ‘self’ into today’s citizens with growing peer-to-peer self-advocacy opportunities. Indeed, it is people with dementia who are now taking forward their own campaign for civil liberties under the banner of human rights and they are supported in this endeavour by the Alzheimer organizations and the World Health Organization in their (2017–25) global action plan on the public health response to dementia [71]. It is this movement and momentum towards social inclusion in society that we now trace, but to do that we must first turn back the clock to view a previous landscape of (in)formal care and organizational language that negatively framed the lived experience of dementia (see also Chapter 2).

4.1 Times Past

In the early 1980s, Brice Pitt’s text Psychogeriatrics [Reference Pitt72] explored the clinical characteristics of dementia, diagnostic considerations and procedures that needed to be followed during the person with dementia’s inevitable downward trajectory towards double incontinence, faecal smearing and death. As Pitt [Reference Pitt72] himself indicated, dementia was a ‘tragic disorder’ whereby:

Sometimes it seems as if the true self dies long before the body’s death, and in the intervening years a smudged caricature disintegrates noisily and without dignity into chaos.

Chaos and faeces – hardly an enticing introduction to the field. At this time, as it had been for many decades beforehand, it was not uncommon for people with dementia to be admitted to single-sex psychogeriatric wards – for example, at one of the (many) Victorian asylums spread across the UK – once care had broken down at home [Reference Andrews73]. Such asylum-based care was provided free by the National Health Service and it is safe to say that most people with dementia admitted to such ward environments lived and died there hidden away from the public, their families and the gaze of the outside world. Looking at the (limited) literature from this time [Reference Andrews73], it is difficult to find any positive language, imagery or affirmations about living with dementia and a rationale as why anyone would want to take on a caring role in such circumstances, either as a family member or as a member of a profession such as social work or mental health nursing.

However, amongst this societal neglect, the seeds of change were beginning to be sown. In the UK, one of the few policy reports in the 1980s that addressed the needs of people with dementia and their carers – a 1982 Health Advisory Service report called ‘The Rising Tide’ [74] – set out the components of a service for people with dementia and recommended that ‘the role in providing support, advice and relief at times of special difficulty to families and primary health and social services is an essential ingredient in a successful comprehensive service’ (p. 17). Such an overt commitment to carers and people with dementia was later reinforced by the King’s Fund Centre [75] in a far-sighted project paper published two years later that detailed the principles of good service practice. By astutely avoiding sharing any exemplars of good practice in the report, the authors were able to set out a challenge to service providers and national policymakers. This was achieved by providing five key principles that outlined philosophical and practical beliefs about personal empowerment for people with dementia. These five key principles [75] (pp. 7–8 abridged) called for an acknowledgement that:

1. People with dementia have the same human value as anyone else irrespective of their degree of disability or dependence.

2. People with dementia have the same varied human needs as anyone else.

3. People with dementia have the same rights as other citizens.

4. Every person with dementia is an individual.

5. People with dementia have the right to forms of support which do not exploit family and friends.

Nearly 40 years on, these five key principles still speak a truth. However, in 1984, society and the caring professions were not quite ready to listen to these empowering values or, perhaps more important, to act on them.

As a consequence, in the research literature of the 1980s, people with dementia were predominantly positioned as a ‘burden’ and the direct cause of the caregiver stress and coping so widely reported at the time [Reference Poulshock and Deimling76–Reference Pratt, Sclunall, Wright and Cleland77]. As an illustration, a significant contribution to advancing understanding about the meaning of care from the experiences of carers of people with dementia emerged from a study conducted in the USA by Miriam Hirschfield [Reference Hirschfield and Copp78–Reference Hirschfield79]. In this study, the author interviewed 30 carers of people with dementia (the sample also included unstructured interviews with seven people with mild cognitive impairment, but those data were not reported), and developed the concept of ‘mutuality’ as ‘the most important variable’ ([Reference Hirschfield79] p. 26) to explain the social relationship between families and the person with dementia. In outlining the properties of ‘mutuality’, Hirschfield [Reference Hirschfield79] suggested that:

It grew out of the caregiver’s ability to find gratification in the relationship with the impaired person and meaning from the caregiving situation. Another important component to mutuality was the caregiver’s ability to perceive the impaired person as reciprocating by virtue of his/her existence.

Accordingly, mutuality was about carers’ ability to find meaning, gratification and reciprocity in their caregiving role and relationship to ‘the impaired person’ (i.e. the person with dementia). Hirschfield [Reference Hirschfield79] also reported that ‘mutuality’ was seen to exist within four parameters:

1. High mutuality from within the relationship (internally reinforced mutuality).

2. High mutuality due to circumstances (externally reinforced mutuality).

3. Low mutuality.

4. No mutuality survived.

Feelings of low mutuality were synonymous with poor adjustment within the family and negative feelings towards the person with dementia. This negative adjustment was as likely to be present in those caring for a person with mild dementia as those caring for a person living through its later stages. Hirschfield [Reference Hirschfield79] outlined three other variables which influenced the planned continuation of home care: (1) management ability, (2) morale and (3) tension. Interestingly, the operational definition of tension included the feeling of ‘being tied down’, and this was conceptualized as the carer’s restricted opportunity for free time and lack of individual privacy. Indeed, it was the combination of low/no mutuality survived coupled with ‘severe tension’ that Hirschfield believed to be the driving force for carers to consider admission into care for the person with dementia, thus predicting the breakdown of care at home. Hirschfield [Reference Hirschfield79] illustrated the existence of this phenomenon via the following case example of ‘no mutuality existing’:

I used to love my father; I used to love to see him come through the door. Now when he comes I hate it. It is like my emotions have changed. I hate to think that I hate my father now, but I just hate the disease he has. It’s like I consider him dead three or four years ago … some people say ‘that’s your father’ but when you hear a door banging all night long you can’t sleep.

With the son’s description of the father being considered dead ‘three or four years ago’ Hirschfield’s case illustration also identified another significant concept in the literature at the time – namely, anticipatory grief and social death [Reference Sweeting80–Reference Sweeting and Gilhooly81]. Such imagery and negative language were later used to define the experience of living with AD as ‘coping with a living death’ [Reference Woods82], an identity marker that left little room for hope or well-being. A new broom was necessary to sweep away such negative and troubling representations, however well intentioned the overarching messages and the underpinning social science.

4.2 Time for a Change

Starting with the work on personhood and person-centred care by Tom Kitwood and members of the Bradford Dementia Group in the UK in the late 1980s [Reference Nolan and Keady83, Reference Kitwood84], and later built upon by others (see paragraph 2.3), new conceptual theories and standpoints about the lived experience of dementia began to emerge. This new wave of studies put the person with dementia’s experience front and centre. As Kitwood wrote as the suffix to the title of his seminal book Dementia Reconsidered, published in 1997, and shortly before his untimely death, ‘the person comes first’ [Reference Kitwood84]. Such an open acknowledgement of the value attached to the experience of living with dementia helped create the space for the social inclusion and social citizenship to emerge: a relational dynamic for people with dementia that continues to the present day.

Whilst academic insights are important, they are not the final word. Indeed, it could be argued that the words and communicated life experiences of people who live with dementia both say so much and do so much to promote social change and social awareness. Stemming from the USA, two books published four years apart kick-started this new insight into the lived experience of dementia based upon individual testimonies. The first publication (in the world) emerged at the time of Kitwood’s early writings in the late 1980s and was published in 1989. This was a relatively short book entitled My Journey into Alzheimer’s Disease written by the Reverend Robert Davis [Reference Davis85], who was aged 54 at the time of the onset of (undiagnosed) AD. Underpinned by his Christian faith, pages 21–82 of this publication were written by the Reverend Davis and articulated a seven-month transition and adjustment to the onset of AD. The remainder of the publication was an interpretation of the later experience of dementia written by Reverend Davis’ wife. This moving account portrayed the fear and uncertainty which accompanied Reverend Davis’ journey into AD:

I can no longer speak in public, and I shatter psychologically in any pressure situation. Mental and emotional fatigue leave me exhausted and confused. Mental alertness comes now only in waves at random hours of either the day or night.

The book also revealed that the couple’s close marital relationship held them together during the onset and progression of dementia, particularly during the early months when Reverend Davis was struggling to make sense of his accumulating losses. Despite his best efforts, his inability to correct the situation was personally devastating to him as he had ‘read a book a day from seventh grade on’ (p. 29). Indeed, it was his inability to resolve this situation that eventually led Reverend Davis and his wife to seek medical help, although their diagnostic quest would prove to be a traumatic experience. In the book, Reverend Davis [Reference Davis85] continually cites his reliance on existential coping techniques to make sense of this experience with the dementia, ‘part of God’s plan’ (p. 80) to test his faith, reconcile his past and affirm the durability of his marital relationship. There was also the belief, expressed both during his account and later by his wife, that AD had brought the couple closer together and that they were able to ‘work through it’ as a partnership once there was an awareness of the name and prognosis of the condition. It was this overriding combination of Christian belief, love and partnership that best summarized Reverend Davis’ journey into AD and one that appeared to continue until the time of his death.

Four years later, another younger person with dementia living in the USA, Diana Friel McGowin, also wrote an influential book/testimony that provided a lucid account of being ‘dragged’ into AD [Reference McGowin86]. McGowin described the emotional, physical, social and sexual turmoil this process had upon her life and that of her family. However, in contrast to the account provided by Reverend Davis and his wife, for McGowin, the early transition into AD was marked by the denial of events by her husband and his reticence to acknowledge that she was failing in any way, as this extract from the book highlighted:

The electric bill was higher than usual because my clothes dryer was not shutting off automatically. I frequently forgot to remove the clothes from the dryer and there were many days when the laundry load tumble-dried all day. Jack was furious, emphasising how much current the clothes drier used. All I had to do was remember to take the clothes out, he said.

For McGowin, such an exchange placed an additional layer of stress upon an already difficult situation, a process that led to ever-increasing cycles of blame and recrimination. Indeed, McGowin revealed that her husband continued to deny the reality of events for several years, which placed responsibility for responding to the symptoms directly with her and led to ‘severe tension’ in their marital relationship – a descriptive marker that directly echoes the earlier work of Miriam Hirschfield outlined in this section [Reference Hirschfield and Copp78–Reference Hirschfield79]. However, this time, it was McGowin, as the person with dementia, who was communicating the relationship challenges she was facing and proving, at a stroke of a pen, that care was not a unidirectional process (i.e. carer to person with dementia) and instead consisted of complex interrelational dynamics.

The importance of these two pioneering personal testimonies should not be overlooked. In their own ways, both books enabled people with dementia to voice their own lives and to remind the public and society as a whole that people with dementia were not simply objects to be studied and reported upon, but human beings who had much to give, share and communicate. It was, after all, their condition and not the exclusive property of others.

4.3 Time for New Horizons

Fast forward to the present day and people with dementia are now intertwined in the fabric of many procedures and practices in dementia care, be that service planning, research, policy, education, disseminations or design. Global, national and local forums have been established to enable the voices of people with dementia to be heard, with examples including:

Dementia Alliance International (www.dementiaallianceinternational.org)

European Working Group of People with Dementia (www.alzheimer-europe.org/Alzheimer-Europe/Who-we-are/European-Working-Group-of-People-with-Dementia)

DEEP network (www.dementiavoices.org.uk)

Scottish Dementia Working Group (www.alzscot.org/our-work/campaigning-for-change/have-your-say/scottish-dementia-working-group).

3 Nations Dementia Working Group (www.alzheimers.org.uk/get-involved/engagement-participation/three-nations-dementia-working-group)

Many of these initiatives are supported by public donations and/or dedicated charitable organizations such as Alzheimer Europe (www.alzheimer-europe.org) and the Alzheimer’s Society (www.alzheimers.org.uk). Over the past 20 years or so, the pace of change has been rapid. However, it should not be forgotten, that in the UK at least, it was not until 2012 that people living with dementia were called ‘citizens’ in influential policy and strategy reporting and ascribed a status that was first set out in the five key principles of the 1984 King’s Fund Centre report [75].

Developing this point, Bartlett and O’Connor [Reference Bartlett and O’Connor87] have put forward ideas around social citizenship to describe the ways in which people with dementia could remain socially included and active citizens. The authors underpinned social citizenship with an ongoing rights-based approach, as seen in their definition of social citizenship:

Social citizenship can be defined as a relationship, practice or status, in which a person with dementia is entitled to experience freedom from discrimination, and to have opportunities to grow and participate in life to the fullest extent possible. It involves justice, recognition of social positions, rights and a fluid degree of responsibility for shaping events at a personal and societal level.

Constructing a theory of dementia through a rights-based approach has also been picked up and articulated by people with dementia themselves and adopted by the World Health Organization in its (2017–25) global action plan on the public health response to dementia [71]. As a further illustration of this movement and momentum, in England, the Dementia Action Alliance has outlined five ‘Dementia Statements’ that people with dementia believe are essential to upholding their everyday quality of life:

We have the right to be recognized as who we are, to make choices about our lives including taking risks, and to contribute to society. Our diagnosis should not define us, nor should we be ashamed of it.

We have the right to continue with day-to-day and family life, without discrimination or unfair cost, to be accepted and included in our communities and not live in isolation or loneliness.

We have the right to an early and accurate diagnosis, and to receive evidence based, appropriate, compassionate and properly funded care and treatment, from trained people who understand us and how dementia affects us. This must meet our needs, wherever we live.

We have the right to be respected, and recognized as partners in care, provided with education, support, services and training which enables us to plan and make decisions about the future.

We have the right to know about and decide if we want to be involved in research that looks at cause, cure and care for dementia and be supported to take part.Footnote 1

As current policy and practice strategies develop to take account of the everyday lives of people with dementia, a rights-based approach to social citizenship that embodies such relational qualities may well be a foundation on which to build lasting change for people with dementia.

Finally, as we have highlighted throughout this section, sensitive language use is very important to the positive positioning of people with dementia and to enabling social inclusion. As a recent example of such work, in a co-produced study conducted alongside people with dementia, and with people with dementia as part of the authorship team, Caroline Swarbrick and her colleagues in the UK [Reference Swarbrick, Khetani, Riley and Keady88] provided language guidance for use in any dementia-related outputs or publications. Some of the main outcomes of this work are highlighted in Table 1.4.

Table 1.4 Language guidance for use in any dementia-related outputs or publications

| When writing about ‘dementia’ |

|---|

| Terms to use: |

|

| Terms to avoid: |

|

| When writing about ‘people’ |

| Terms to use: |

|

| Terms to avoid: |

|

| Adapted from Swarbrick et al. [Reference Swarbrick, Khetani, Riley and Keady88] |

Socially inclusive practices for people with dementia also extend to the environments where everyday life is played out. This can be seen in the rise of the dementia-friendly community movement [Reference Shannon, Bail and Neville89] and in better understanding how people living with dementia age in place [Reference Kaplan, Andersen, Lehning and Perry90]. On this latter issue, Clark et al. [Reference Clark, Campbell, Keady, Kuhlberg, Manji, Rummery and Ward91] have recently undertaken a major mixed-methods study looking at how people with dementia connect to the spaces, places and people in their neighbourhood. The authors suggested that ‘small acts of kindness’ displayed by neighbours and friends helped people with dementia remain both socially connected and positively positioned in a relational network. The transcending message here is that it is sometimes not only major public health and dementia awareness initiatives that are required, but also a recognition that micro interpersonal practices in the neighbourhood help maintain the social identity and inclusivity of people with dementia. And in many ways, all of us have a civic obligation to play our part in both undertaking and maintaining such actions.

5 Political Perspectives on Dementia

In line with this, there is also an increased political interest in dementia, which results in part from the demographic reality that populations globally are ageing and hence the number of individuals with dementia is rising, which leads to rapidly increasing healthcare costs. The World Health Organization estimated that 47 million people worldwide had dementia, which results in a total cost of more than $1 trillion (USD) in 2019 [Reference Wimo, Guerchet, Ali, Wu, Prina, Winblad and Prince92]. Moreover, the number of individuals with dementia will increase to 75.6 million by 2030, leading to even greater costs in the near future (see also Chapter 14).