If Americans had fought in World War II to achieve a sense of security, to be free from fear, such peace dividends did not last long. By the late 1940s, the United States once more seemed under assault, from threats both foreign and domestic. As Cold War political lines hardened, the distinction between external and internal menaces became ever more difficult to perceive. Not only was the globe under threat from a vast communist conspiracy – all ostensibly controlled by Moscow, many believed – but the tentacles of communism apparently were reaching deep into American society. Just as threatening, the postwar consumer society appeared to be enfeebling an entire generation of men. It was no coincidence that contemporary social critics spoke of “proletarianized” white-collar workers who were losing their individuality in corporate America. How would such men defend the nation? How could they at once counter communist aggression, at home and overseas, while resisting pressures to conform to a society seemingly intent on emasculating them?1

While communist conspirators posed a threat, so too did women. Indeed, American women appeared more menacing than Stalin’s red henchmen. It looked as if female antagonists were attacking men from all sides. Suburban wives and mothers were exercising a “suffocating control” over sons and husbands. Femmes fatales stood ready to pounce on unsuspecting men, exploiting female sexual wares to deceive and demoralize.2 Call girls and mistresses chipped away at the moral integrity of American society. And, in this era of persistent war, female “camp followers” preyed on decent servicemen, a “sinister force” which threatened the nation’s “entire defense programs.” As one account in Real Combat Stories warned, becoming involved with these “harlots” was to “engage in a game of Russian roulette.”3

This general atmosphere of persecution, fear, and distrust of women and other forces that might weaken the World War II-era military man intimated larger anxieties gripping American society. The designs of global containment, aimed at preventing communist expansion overseas, rested on accepting a healthy dose of fear at home. Fear of nuclear Armageddon. Fear of communist subversion. Fear of men not measuring up in an apocalyptic battle pitting good against evil.4 Such worries ran deep enough for historian Richard Hofstadter to argue in 1964 that a “paranoid style” in American politics had created a central image in which a “vast and sinister conspiracy” had been “set in motion to undermine and destroy a way of life.” Yet these same anxieties – domestic, ideological, geopolitical – were essential to pulp culture writing.5

In this era of Cold War anxieties, adventure magazines helped shape young male readers’ world views, driving home an alternative version of masculinity for a mass society seemingly bent on weakening American manhood. They imparted hope for rehabilitation, a way to meet the contemporary challenges besetting the nation’s men.6 Moreover, the pulps’ message was timely. In terms of expectations about sex, gender roles, and the societal responsibilities of both men and women, the period from World War II through the late 1960s saw a great deal of upheaval. The postwar macho pulps thus offered a paradigm for men to embrace, a way to exemplify a traditional sense of masculinity in an uncertain time. Within the magazines, men were once more the unencumbered protector and provider. There, they could bask in gallant stories of the glorified male warrior. And, as one Vietnam veteran recalled, they could return to a heroic time, “before America became a land of salesmen and shopping centers.”7

Cold War Anxieties

Despite the unconditional surrender of their enemies in World War II, Americans could not shake a deep sense of insecurity as they entered the postwar years. They worryingly faced new villains. Indeed, they helped to create them. Communist devils conveniently replaced sadistic Nazis and savage Japanese as the new foe.8 The 1950 McCarran Act, for example, declared that the world communist movement posed a “clear and present danger to the security of the United States and to the existence of free American institutions.” In the process, the bill limited civil liberties, requiring all communist organizations to register with the attorney general and authorized the president to proclaim the existence of an “Internal Security Emergency.”9 Apparently, the nation once more was at war.

Yet what if American men, feminized by the postwar consumer society, could not meet the demands of this new war? What if they had become too soft? These were hardly new questions and, in truth, reflected prevalent concerns over “modern manliness” at the opening of the twentieth century. Then too, men seemed under siege. They were becoming “overcivilized” in this new industrial age, soft and flabby, all while American society was being “womanized” by first-wave feminists demanding political emancipation.10 This obsession over masculinity, and the challenges to it, may not have reached a crisis, but clearly the opportunities to prove one’s manhood seemed ever more constricted in a decadent, modern society.11

The antidote came from the likes of Teddy Roosevelt, charismatic men who advocated living a “strenuous life.” To be sure, only traditional gender relations supported such a rejuvenation. As Roosevelt pronounced in 1899, “When men fear work or fear righteous war, when women fear motherhood, they tremble on the brink of doom.”12 Men’s magazines of the day took notice, selling the ideals of a physical culture based on sport and outdoor adventure. Such newly reinvigorated men then could transfer their prowess to arenas where it mattered. As Century Magazine put it, strong men would no longer fight “in the fields or forests,” but rather “in the battles of life where they must now be fought, in the markets of the world.” It took few steps to marshal this philosophy in support of an expansionistic, if not imperialistic, US foreign policy. Only virile, vigorous men could lead the nation – and the world.13

Such gendered language reemerged during the Cold War. Only strong men could steer and protect a strong nation. George F. Kennan, the author of containment doctrine, evocatively portrayed the Soviet government “as a rapist exerting ‘insistent, unceasing pressure for penetration and command’ over Western societies.”14 By the 1960s, Lyndon B. Johnson was using far less subtle language when it came to US foreign policy. The president derided one administration official for “going soft” on the war in Vietnam, scornfully asserting “he has to squat to piss.” Reacting to the late 1966 bombing of North Vietnam, LBJ proudly declared, “I didn’t just screw Ho Chi Minh. I cut his pecker off.” Yet behind this bravado lurked a chronic anxiety. Biographer Doris Kearns shared with her readers Johnson’s fears of being regarded as a “coward” and an “appeaser.” To journalist David Halberstam, the president desperately wanted “to be seen as a man… he wanted the respect of men who were tough, real men, and they would turn out to be hawks.”15

To help combat these anxieties, many Americans during the Cold War era turned inward to the family, the “cornerstone of our society” in Johnson’s words, which would help promote civic values, morals, and patriotism.16 Yet men’s adventure magazines alluded to problems with such conceptions. Apparently, all was not well at home. The November 1959 issue of Cavalcade, for example, ran a story on the “recent revolution in sex customs” that was causing a spike in extramarital relations. Changing mores – “largely in the matter of the woman’s behavior” – implied that the traditional American family might be breaking down. Worse, it seemed, men were bearing the brunt of these changes. That same autumn, Challenge printed a story on the “millions of anxiety-ridden American men” who faced “serious mental illness” because they could not cope with numerous “upsetting sex problems.” According to the article, these men were “deeply troubled because they feel sexually inadequate, abnormal or guilty.”17

Not surprisingly, the macho pulps spoke little of the costs endured by women who were forced to subordinate their own desires to reinforce traditional values. Not all freely chose the postwar “retreat to housewifery.” In the pulps, though, it was men who suffered as a result. As women increasingly controlled the domestic sphere, so a popular narrative went, they became an “idle class, a spending class, a candy-craving class.”18 In social critic Philip Wylie’s eyes, men were spending most of their time supplying “whatever women have defined as their necessities, comforts, and luxuries.” No wonder then, as the editors of Look magazine argued, women’s new “economic and sexual demands” were “fatiguing American husbands.” Of course, where fears lurked, so too did opportunities exist. Thus, thumbing through adventure magazine ads, readers might remedy their ailments by sending in for a guide explaining “How to double your energy and live without fatigue.”19

Surely, not all men lived in panic during the 1950s, but the pulps did reflect widespread gender anxieties of the day. The domestic costs of containing communism at home, coupled with concerns about the dampening effect of women’s desires for affluence and security, suggested that suburban life might be corrupting real men. Certainly, popular novels like Revolutionary Road and The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit spoke to these anxieties, as did pulp articles like “Why Do We Have to Marry Women?”20 Men’s adventure magazines thus might be seen as an outlet for the frustrations of living in a conformity-inducing society. If Betty Friedan correctly surmised that male outrage was the result of an “implacable hatred for the parasitic women who keep their husbands and sons from growing up,” then the macho pulps offered a wish fulfillment for those fantasizing about reaching their full potential as manly men.21

The corporatization of America further fanned male anxieties. Arthur Miller’s Willy Lohman and William Whyte’s “Organization Man” both illustrated the decline of individuality, if not spirit, in an era of consumer capitalism where mass corporations seemingly reigned supreme. Moreover, these works suggested that World War II veterans were having a difficult time reintegrating into a society that did not fully appreciate their sacrifices. In the 1956 film version of The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, Betsy Rath accosts her husband Tom for being more cautious since returning home from war: “You’ve lost your guts and all of a sudden I’m ashamed of you.”22 Two years later, an Esquire essay by Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. argued that men had retreated “into the womblike security of the group” and that mass democratic society itself constituted an “assault on individual identity.” “The frontiersmen of James Fenimore Cooper,” Schlesinger lamented, “never had any concern about masculinity; they were men, and it did not occur to them to think twice about it.”23

But how to maintain a sense of self-reliance when you were accepting government handouts? Take, for instance, the GI Bill which expanded access to education for an entire generation of American veterans yet clearly fell within the realm of social welfare expenditures. Some eight million World War II vets, just under fifty percent of the eligible population, received training benefits from the program. Roughly two million Korean War veterans did the same.24 In addition, federal housing loans enabled young families, many for the first time, to purchase their own homes. Might it be that such welfare programs offering education and advancement came at a cost? Didn’t white-collar jobs stimulate fears of feminization? Perhaps this is why the most common reason veterans cited for not using the GI Bill was that they “preferred work to school.” Indeed, men’s adventure magazines walked a fine line when it came to questions that were so intertwined with class conceptions. The pulps extolled the benefits of military service, and how it could promote social advancement, yet openly venerated working-class ideals and their value to proving one’s manhood.25

Thus, it seems likely that many white, middle-aged men, bored or frustrated with their postwar lives, read men’s magazines to regain a sense of what the periodicals were selling most – adventure. As historian Heather Marie Stur argues, the pulps “glorified the outdoorsman and the warrior as the antidote to stifling wives and domestic responsibilities.”26 According to Stag, the US Navy held “that exactly half the guys who volunteer for and go on Antarctic duty are there to escape women. If they’re married, then Antarctica represents a cooling-off period.” Men magazine went further. A July 1964 article, “A Young Legal Mistress for Every Man,” asked readers if they were “plagued by a nagging wife” and if their jobs were driving them crazy. The “natural solution”? A querida who could serve as the “married male’s last link with his romantic bachelor past.” On the word of Men, the system worked so well that “even wives are for it.”27

Despite these potential solutions, in numerous magazines – from Cosmopolitan to Playboy to Man’s Action – it appeared as if wives were gaining the upper hand to “dominate” the American male. Modern mass society supposedly had feminized men. Cosmopolitan argued that “a boy growing up today has little chance to observe his father in strictly masculine pursuits.” Writing for Playboy in 1958, critic Philip Wylie decried the “womanization of America,” a “sad condition” in which women had secured dominance over men. The article’s tagline left no doubt where Wylie stood: “an embattled male takes a look at what was once a man’s world.”28

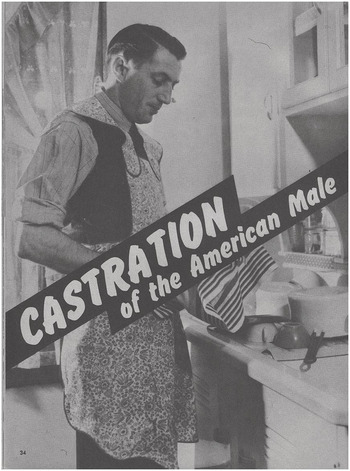

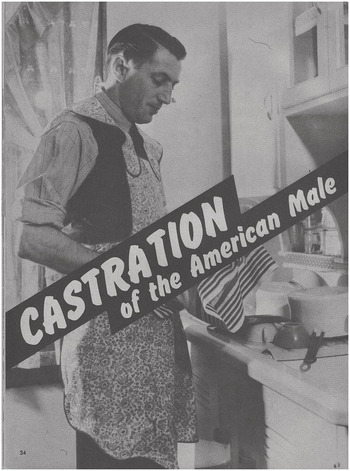

Adventure magazines went a step further: men weren’t just being emasculated by the domestication process, they were being fully “castrated” by women in the home. Sir! offered a 1962 contribution titled “The Mental Castration of Husbands.” Author Joe Pearson argued that “frustrated females” were waging “an all-out campaign against their mates.” The goal, apparently, was to turn the man into a “converted housemaid.” One year later, Brigade followed suit with “Castration of the American Male.” A photograph of a sullen husband, in floral apron doing the dishes, accompanied the article. In it, Andrew Petersen claimed that the “manly virtues – strength, courage, virility – are becoming rarer every day… Femininity is on the march, rendering American men less manly.” By mid 1966, the process of emasculation seemed complete as Man’s Action asked if men’s “sex guilts” were making them impotent.29

In an era of endless war against communism, concerns abounded that this emasculation of the American man might undermine military readiness. One periodical worried that if men were “denied a sphere of vigorous action,” they could lose their “chance of heroism.” The macho pulps, though, took the matter head on, especially in the immediate aftermath of the Korean War. Famed aviator Alexander P. de Seversky, writing for Man’s Day in 1953, pushed back against impressions that “American boys have suddenly become ‘afraid to fly.’” To Seversky, there was “nothing wrong with our young manhood.” Yet doubts persisted. In 1955, Senator Estes Kefauver (Democrat, Tennessee, a member of the Senate Armed Services committee) penned an essay for Real Adventure on the problems of American men being rejected for military service. Kefauver found that one of every ten men would be unqualified for service because they were “emotionally unfit or sexual deviants or unable to stand up mentally under the strain of army life and combat.” The problem had left the United States “shockingly, dangerously vulnerable,” so much so that the senator asked his young readers, “Are you the ninth man?”30

While fears of military unpreparedness reflected broader social anxieties, such concerns did not extend to matters of race in Cold War America. Men’s adventure magazines were written by and for white men. Rarely did African Americans appear in the pulps’ pages. Occasionally, men’s magazines would focus on contemporary racism, such as a 1952 Stag article highlighting a black World War II army air corps veteran who tried to move into a Chicago suburb.31 A few pulp stories drew attention to the 1963 assassination of civil rights activist Medgar Evers, and True published an essay on “The Klansman.” But nowhere could readers listen to the stories of Ralph Ellison, James Baldwin, or even Louis Armstrong.32 Only in periodicals like Ebony and Duke could black men find similar treatments on masculinity and the challenges and opportunities of the Cold War consumer culture.33

Catering to a white male audience meant that men in minority groups – blacks, Latinos, Asian and Native Americans – were not recognized in the pulps as “real” or “full” men. This, despite the US armed forces becoming increasingly diverse in the 1950s and 1960s. Mexican American Raymond Buriel, for example, believed that if he and his peers “went into the military and served, nobody could question … our place here.”34 Yet such aspirations seldom made it into the macho pulps. In large sense, adventure magazines not only deprived minority men of a place within the dominant narrative of masculinity enjoyed by fellow white soldiers – a kind of “sexual camaraderie” – but also implied that these men were not truly part of the heroic warrior–sexual conqueror paradigm. The “All-American” melting pot infantry squad, so popular in wartime movies, rarely saw action in pulp adventure stories.35

In other endeavors like sports – baseball and boxing, in particular – white Americans might allow some form of racial integration. Within the postwar pulps, blacks almost always were portrayed as athletes. Stories ran on boxers Jack Johnson, Floyd Patterson, and Sam Langford, “The Boston Tar Baby,” or on African American weightlifters like George Paine.36 Racial fears and sexual anxieties, however, proscribed black men from being more. If their heroes were white, pulp writers could combine martial exploits with sexual conquest. An African American man, though, could never be linked to such sexual fantasies, especially those involving the taking of a white German Fräulein, a popular target of pulp heroes. White sexual champions, even predators, were acceptable, not black ones. In this vein, American Manhood published an article on venereal diseases and covered only syphilis and gonorrhea, because other STDs did “not occur too often among white people” and thus did not warrant discussion.37

Sporadic storylines did emerge of minority soldiers performing acts of heroism. Stag ran a few paragraphs on Private First Class Milton Olive, the first African American to earn the Medal of Honor in Vietnam, while Male featured Sioux Indian athlete and US marine lieutenant Billy Mills, who won a gold medal at the 1964 Olympics.38 But in these stories, the hero never attained the sexual rewards reserved for his white compatriots. Or, in many cases, the recognition. As one civil rights leader, quoted in Stag’s piece on Olive, shared, “Men who have won our country’s greatest honor have become, in a sense, unknown soldiers.”39

Of course, men engrossed in these magazines may have been less apt to think about the state of racial inequality in 1950s America. Still, not all seemed right with the world. A host of Cold War anxieties – racial, gendered, social, domestic – intimated that working-class men were somehow not reaping the full rewards of a mass, consumer-based society. Despite the sense of a growing middle class, many Americans still felt they were being left behind, still confronted with the realities of social and economic inequality. Perhaps this explains why men’s adventure magazines promised quick fixes to life’s daily problems. One advertisement declared that you could “achieve more social and economic success” by developing a “stronger he-man voice.” Here was your chance to “Be a ‘Somebody,’” the ad proclaimed. An essay in Real assured readers that “Your Screwy Idea Can Make You a Million,” the money-making brainstorms including whiskey-flavored toothpaste, do-it-yourself voodoo kits, and wax for “butch” haircuts.40

These strange ideas vowing profitable businesses, laughable in retrospect, illustrated genuine worries that men weren’t measuring up in the aftermath of World War II. They also underscored the class component of men’s adventure magazines. A sense of fiscal insecurity permeated ads and storylines of working-class men unable to take full advantage of the postwar consumer culture. One correspondence school advertisement, for instance, asked, “Are you expendable?” Another queried readers on whether they were “standing still” on their jobs. “Will recognition come?”41 And as the nation inched closer to full-scale war in Vietnam, Male offered an exposé on why work pensions might not be “worth a red cent.” So distressing were these economic hardships that Saga found it necessary to publish an article on men who, “working overtime, commuting to the suburbs, [and] taking care of a lawn,” could no longer even afford a mistress.42

For pulp readers, though, an alternative to these frustrations existed. Adventure magazines promised untapped resources to achieve or regain one’s masculinity. Pay raises, promotions, women, heroism, and success in life all lay within reach. Or so the pulps implied.

Selling a New American Man

Despite magazines’ promises of advancement and security, working-class anxieties never seemed to subside during the years leading up to America’s war in Vietnam. While the nation’s gross national product grew by over $200 billion between 1950 and 1960, many male workers felt increasingly overworked and underpaid. Studies showed that “disposable time” dropped for working-class men, while the income inequality gap grew between them and the middle class.43 Moreover, job attitude surveys suggested a widely held dissatisfaction with work. Sociologist C. Wright Mills even claimed there was a “fatalistic feeling that work per se is unpleasant.” Men’s magazines might have revered working-class ideals of the “self-made man,” but such notions increasingly appeared more myth than reality. Could it be that World War II had also failed in delivering “freedom from want”?44

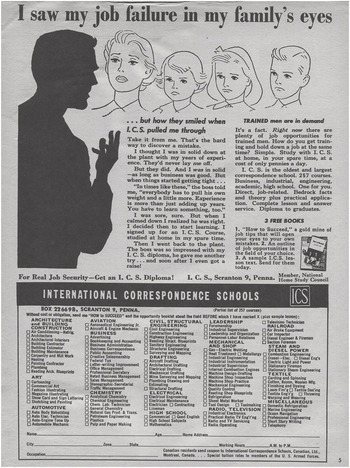

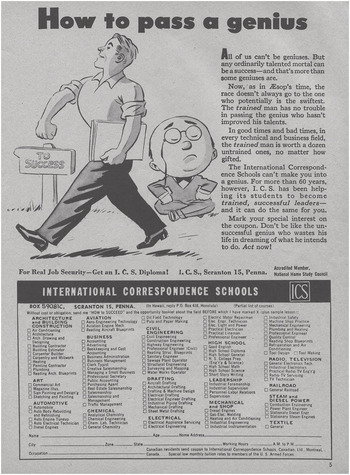

Worries over being unable to provide for one’s family reintroduced fears from the Great Depression, when high unemployment rates undermined men’s identities as breadwinners. This relationship between work and masculinity remained strong well into the 1960s, and pulp adverts were sure to exploit these associations.45 In Battlefield, the Commercial Trades Institute ran an ad on training to become a skilled auto mechanic. Here was an opportunity to “make your income grow with family needs.” International Correspondence Schools, though, put shame at the center of its advertising campaign. “I saw my job failure in my family’s eyes,” declared a man looking into the disappointed faces of his wife and three children. Needless to say, such gendered conceptions of work ignored women’s economic dependence on men. But compassion wasn’t necessary in the pulps’ definition of manhood. Real husbands and fathers were providers, plain and simple.46

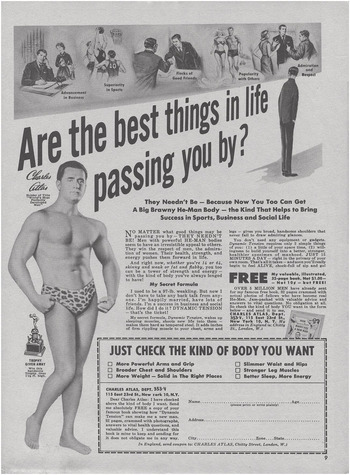

One remedy to this occupational angst was to focus on the male body. Certainly, there was a military component at play. In early 1953, for example, American Manhood, a muscle-building and physical culture magazine, paid tribute to the burly men of the US Army’s tank corps who stood “ready to hold the forces of Repression at bay.”47 Yet class further layered martial images of the body. Male published “College Men Are Sexually Inferior” in July 1954. According to the author, Dr. James Bender, not getting into college may have left some men with “an uneasy sense of inferiority.”48 Nevertheless, the strong, “average” man could still discern an attainable path toward masculine fulfillment, simply by following ostensibly proven methods. Pulp ads sold strength and vitality as key components of success, and by the 1950s, magazine adverts were commanding a hefty percentage of advertising revenue within the United States, as companies purposefully linked consumption with the achievement of status.49 But these ads were not just selling goods and services. Advertisements, targeting working-class men, were also promoting and reinforcing a conception of manhood that paralleled magazine storylines and artwork. Masculine dominance, in a sense, could be purchased (and, thus, validated), through new job opportunities, “how-to” sex manuals, or products enhancing one’s physical stature and looks.50

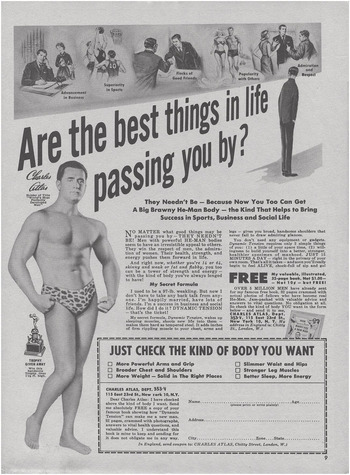

Towering above the mail-order business stood Charles Atlas, an Italian American bodybuilder who titled himself “The World’s Most Perfectly Developed Man.” Atlas left little ambiguity in arguing that real men could “just pick the kind of body” they wanted, amass bulging muscles, and go on to perform heroic acts of strength, either on the beach or in the boardroom. Yet male anxieties never lurked far below the surface. “Don’t Be Half A Man!” exclaimed one popular ad. “Don’t Spend Your Life on the Sidelines” decried another.51 In these adverts, “real he-men” were not “held back by a half-a-man body.” Instead, they had chosen to attain their “dream build” which brought them success in everything they did. And, of course, women were “naturally attracted to the strong, red-blooded man who radiates magnetism.” Thus, getting “power-packed shoulders” would “make girls go ‘Ga-Ga’ on the beach.” Atlas’s version of manhood rested on the assumption that “big brawny he-men grab the most attention, the best jobs, [and] the prettiest girls.”52

Joe Weider, editor-in-chief of American Manhood, replicated this connection between men’s bodies, sexual attractiveness, and hoped-for sexual conquest. The magazine’s editorial policy noted that bodybuilding would lead to “impressive muscular development,” “strong character,” and one’s place in society as a “respected citizen.” In many ways, Weider’s magazines were little more than eighty pages of ads for his system of muscle building. He exhorted his readers to be proud of their bodies and “Stop Being a Weakling Today!” To Weider, “millions of boys” were “underdeveloped and weak,” being bullied and “pushed to the side.” But, like Atlas, he had the solution. Hardened bodies could propel young boys into manhood.53

Yet these bodies were an idealized version of masculinity that may have seemed improbable for the average reader to attain. Consumption thus became a way to assuage male insecurities, a chance to transform one’s self and remake one’s body. As one pulp editor recalled, virility was a “subject close to the male fiction reader’s heart.” Both stories and advertisements therefore played on these fears of being an imperfect, even deficient man.54 Challenge, for instance, noted that “Americans spent $167 million in 1957 for non-prescription ‘quick pills’ to sooth minor disturbances.” Meanwhile, ads stoked men’s anxieties over their loss of virility – and their hair. Most pulp magazines included at least one advert on “the miracle of hair regrowth.” Taylor Topper told prospective customers there was no need to be bald and that they could “feel better” and do their jobs better. “Don’t be ignored,” the ad declared,“because you look older than you are.”55

In the Cold War era, moreover, any loss of virility could have stark military consequences. When American POWs in the Korean War refused repatriation, ostensibly because they had succumbed to communist brainwashing, critics worried that soft, flabby American men were not strong enough to endure “advanced new techniques of psychological torture and mind control.”56 President-elect John F. Kennedy, writing on the “Soft American” for Sports Illustrated in 1960, argued that the “first inclination of a decline in the physical strength and ability of young Americans became apparent among United States soldiers in the early stages of the Korean War.” Military officers shared Kennedy’s concern. The head of physical education at West Point, Colonel Frank J. Kones, feared that without a vigorous fitness program, “our children will certainly become a race of eggheads walking around on bird-legs.”57

This decline in “moxie,” according to one army general, not only placed the nation at risk in an ideological war with the communists, but also informed popular attitudes about the country’s enemies. Russian soldiers were hearty. Chinese and Vietnamese troops lived and fought on a bowl of rice a day. The Korean War images of brainwashing, in comparison, depicted American GIs as weak, succumbing to the greater strength of the Reds. In the 1956 film The Rack, for example, Paul Newman plays a former POW from Korea on trial for treason. At movie’s end, he is convicted, despite the many tortures he experienced while a prisoner.58 Arguably, The Rack spoke to American weaknesses far more powerfully than The Manchurian Candidate (1962), in which the target of Chinese subversion was a spineless politician. That Paul Newman could succumb to torture suggested the nation might not be producing men worthy of military service. Marine Colonel Lewis “Chesty” Puller went further, linking indulgent American lifestyles to an existential threat. As he declared to his troops in Korea, “Our country won’t go on forever, if we stay as soft as we are now. There won’t be an America – because some foreign soldiers will invade us and take our women and breed a hardier race.”59

Following Puller’s logic, for the United States to survive the Cold War, strong American men also needed to procreate. Here, the macho pulps stood ready with advice columns and advertisements for readers who hoped to “banish sex ignorance” and avoid “shameful errors” that might ruin their lives. An ad for the book Sex and Exercise listed a host of potential sexual pitfalls. “Keep your virile powers healthy and strong. Protect yourself against impotency. Conquer weakening habits. Night losses. Sex fatigue.” Indeed, as one article on “Sex Knowledge for Young Men” warned, there were “beautiful aspects of sex,” but also a dangerous, “gloomy side.” Thus, “heavy petting” – kissing and “handling and fondling of more intimate parts of the body” – could lead to unwanted pregnancies or, apparently worse, venereal disease.60

While women might be toxic vehicles carrying gonorrhea and syphilis, “well hidden in the vulva or vagina,” they also generated fears that men might underperform in marriage. Challenge offered advice for the “many men [who] stumble through the crisis of the wedding night like bulls in heat.” Stag ran a similar ad counseling “the bewildered groom” on the “hazards of the first night.” “How Much Is ‘Too Much Sex?’” asked yet another report from Showdown. The possible nightmares piled up from story to story. Virginity could cause cancer. Infertility was normally the husband’s fault. Emotional, psychic, and physical deficiencies kept men from an “ideal sexual union.” Frigidity and differences in age undermined happy marriages. No wonder young pulp readers might be anxious about their sexual performance. As Battle Cry proclaimed, “Ignorance Can Ruin Your Sex Life.” The answer, “according to prominent authorities,” was that “book learning is no substitute for actual, practical experience.”61

Recommending that men be more promiscuous surely increased the prospects of young pulp readers developing or reinforcing sexist attitudes toward women. Constantly proving one’s manhood required testimonials that men were not, in fact, inferior. “Sex guides” consequently offered advice on the “causes and cures of female frigidity,” how “techniques of seduction” could open up new worlds for readers, and the need to be persistent when one’s sexual advances were discouraged. If glamour girls were a “pain in the boudoir” – the pulps regularly used the term “girls” over “women” when discussing sex – men still could gaze upon them without repercussion. As Men declared, “Ogling girls is the God-given prerogative of any male with corpuscles in his veins and hormones that aren’t completely atrophied.”62

Cartoons similarly reinforced these attitudes. In one sketch, a naked male doctor, with only a stethoscope draped around his neck, exposes himself to a female patient in a low-cut black dress. Entering the waiting room, he asks “Who’s next?” In another, a male executive is seen tape measuring a female job applicant’s chest. “I don’t mean to pry, sir,” she queries, “but what has this to do with typing 120 words a minute?” Apparently, professional men in positions of power could act without any fear of consequences.63

These depictions surely left their mark on young men, especially those with limited sexual experiences. As one Vietnam veteran recalled of his childhood, the erotic content of men’s magazines “held the promise of wonderful possibilities for the future and was for years as close as I would come to the forbidden pleasures of the opposite sex.” Yet the tensions between desire and fear promoted an underlying sexism pitting man against woman. Ads ran on how men could achieve the “ultimate conquest,” while advice columns told readers how to avoid “bedroom barracudas.”64 A Men story from 1961 on boosting one’s “sexual batting average” noted how the “male–female relationship is a highly competitive one.” Consequently, numerous pulp offerings instructed men on how best to find “tramps” and “all-out love kittens” or how to turn “temporary virgins” into “eager, passion-starved women who’ll ‘swing’ with the first man available.” Male even promoted emotional manipulation, arguing that the best time “to finesse a girl into the hay is when she’s just been jilted by a guy. She’ll be out to prove her ‘femininity,’ that she’s really an effective sex partner, and will often go on a wild bedroom fling to prove this.”65

This Cold War sexism advanced in the macho pulps could be found in the 1940s armed forces as well, especially targeting women who served in uniform. Those who volunteered in World War II were met with disdain, condescension, or outright hostility. As one advisor on wartime women’s units found, “If the Navy could possibly have used dogs or ducks or monkeys, certain of the older admirals would probably have greatly preferred them to women.” Many male GIs saw their female counterparts as whores, lesbians, or “confused women who think they want to be men.” Moreover, a number of these women suffered intense slander campaigns aimed at demonstrating their unworthiness to wear the uniform.66 Similar attitudes persisted after the war. Male recruits in basic training were called “ladies” by overbearing drill instructors, while Battlefield published a 1959 cartoon that reeked of outright sexism. In it, a curvaceous WAC stands in front of a male officer’s desk, her uniform outlandishly tight-fitting. “You said no to my pass yesterday, Corporal, so I’m doing the same to your request for a furlough.” The double-meaning of “pass” underpinned the joke, but the quid pro quo clearly qualified as sexual harassment.67

While popular images both scorned and eroticized women in uniform, men’s adventure magazines picked up on the realization that army training was not providing basic information on wartime sex to new recruits. Sex education within the military ranks had never embodied sound pedagogical practices, but the World War II experience seemed to demand a reconsideration of training methods.68 The pulps lambasted the army’s “Mickey Mouse” training films for not being more honest, thereby inadvertently promoting venereal disease within the ranks. Apparently, these movies fell into two ineffective categories – the “shocker” and the “preacher.” To Battle Cry, the “shocker” proved particularly futile since “bleeding canker sores were too much to take for some of the weaker stomachs.” The problem seemingly stemmed from the “American attitude toward sex – a guiltiness and a sense of shame, perhaps – which makes it impossible even for grown-up Army strategists to face the facts of life without fear and trembling.”69

Though the pulps suggested that Army films might be too “straight-laced,” the magazines themselves contributed to a stilted sense of what was acceptable, if not normal, for how young men should view women. Ads for lingerie products, stag movies, and pornographic photos all depicted women as objects to be consumed or controlled. Readers, for instance, could purchase glossy photos of Brigitte Bardot, “that delectable piece of French pastry,” for only one dollar. Or they could order The Pleasure Primer, which ran under the tagline “No woman is safe (or really wants to be) when a man’s mind is in the bedroom.” Might such language leave a young man with the impression that women didn’t really mean it if they spurned his sexual advances?70

Of course, an unskilled “cog in the machine” likely had little chance of wooing someone like Brigitte Bardot. Men’s magazines therefore offered opportunities to achieve status and financial security. Advertisements ran the gamut, from jobs in meat cutting, which offered “success and security,” to training as auto mechanics, plumbers, steamfitters, and welders. One man “hit his stride” by becoming a locksmith, while others found “profits hidden in broken electrical appliances.”71 Striving for status took center stage in these ads. “Be a Clerk all my life? Not Me!” declared one advert. “Don’t Stay Just a ‘Name’ on the Payroll,” proclaimed another. By the mid 1960s, ads spoke of “unlimited opportunities … in programming IBM computers” where the “prospects for high pay and professional standing” were “unlimited.” In a sense, these careers offered opportunities to embrace the ideal of becoming a skilled artisan, a highly trained worker whose talents were admired and valued. As one advertisement pledged, “Here is your chance for action and real job security.”72

Once more, though, anxieties lingered. What if these trade jobs did not offer higher status as promised? What if pulp readers were falling behind their more educated peers? Advertisements thus pushed self-help booklets aimed at personal growth. Or at least the impression of growth. “Everyone takes Bill for a college man,” began one ad, “until he starts to speak. Then the blunders he makes in English reveal his lack of education.” Because these mistakes were holding men back, correspondence courses vowed to help them “Speak and Write Like a College Graduate.”73 If they had been barred from better jobs because of a lack of education – “Sorry, we hire only high school graduates” ran one advert – then there were plenty of chances to finish high school at home. As the Wayne School in Illinois encouraged, men who had “had enough of just working in a rut,” who wanted to “make up rapidly for lost time,” could “know the feeling of pride and confidence that comes with saying, ‘Of course, I’m a high school graduate.’”74

This selling of a new American man, however, had its limits. A young working-class male might improve his vocabulary or earn a few extra dollars a month, but how much adventure came with packing meat or repairing electronics? Though several ads promised “Exciting Outdoor Careers of Adventure,” becoming a game warden or fish hatcheryman hardly garnered as much respect as a combat veteran with rows of medals on his chest.75 Perhaps unsurprisingly then, many young men who ultimately went to Vietnam recalled seeking a sense of adventure there. One recalled, while driving a delivery truck at home, that “the bug hit me to try something different.” Another remembered that he “burned for a new adventure,” while still another admitted being afraid to serve but also realizing that joining the army “was probably the greatest adventure I was going to have in my life.”76 Especially if such service could be linked to larger notions of defending the nation against an enemy threatening freedom across the globe.

The Red Menace

Men’s adventure magazines from the 1950s and 1960s made it clear that World War II had spawned a new threat, not just overseas, but at home as well. Pulp writers shared the fears of US foreign policy experts who believed that Soviet communists had transformed the whole world into a massive battlefield. To them, the Cold War had become a “titanic contest” between good and evil.77 If Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy was correct in arguing that Americans had become apathetic to evil in the aftermath of World War II, that there was an “emotional hangover and a temporary moral lapse which follows every war,” then the pulps offered a tangible reminder that the communist threat was authentic.78

Articles abounded of “fanatical communists” bent on world domination. Soviet agents murdered US diplomats in Europe, while others trained “fake Americans” in the Ukraine who then would live in the United States and steal state secrets. Russian spy fleets, posing as “oceanic expeditions,” trawled along US coastlines, setting up a “high seas espionage network capable of everything from stealing the results of our latest missile test to sneaking Red agents into America!”79 Another report focused on a huge “Russian undersea armada” and questioned if the Soviet navy was planning a “submarine Pearl Harbor.” “The danger is now,” declared the piece. So pressing had the threat become that the head of the KGB apparently held so much power, he could “tip it to total annihilation of the world any time he chooses.”80

Making matters worse, the threat came not only from the Soviets, but from the Chinese as well. In the aftermath of the 1949 communist victory in the Chinese civil war, many Americans mistakenly deemed Mao’s China merely a puppet of Moscow.81 Pulp writers thus spoke of Chinese brainwashing and torture and of the “million-man Chicom horde” and its plans for a “merciless ‘blitzkrieg’ that would gut free Asia.” One author described Peking as the “capital of a slave-state where ‘brainwashed’ millions toe the line.” Additionally, an exposé on the Cultural Revolution described Chinese Red Guards, unleashing an “orgy of death,” as “murder monsters who may be America’s front-line enemies in World War III.”82

In fact, the global communist threat appeared so dangerous that perhaps the United States was being harmed in playing by the rules. Battle Cry published a 1957 screed titled “Let’s Scrap the Geneva Convention.” According to the author, the “terrorists of the Kremlin must be made to realize that their soldiers will suffer the same fate they mete out to others if they are captured.”83 This view of the enemy, that savages only responded to force, permeated into the highest levels of government. During the Eisenhower presidency, General James Doolittle, hero of the first air raid over Tokyo in World War II, conducted a review of CIA activities. In his report, Doolittle painted communists as an “implacable enemy” pursuing global supremacy. “There are no rules in such a game,” the general argued. “Hitherto acceptable norms of human conduct do not apply.” Thus, covert operations aimed at regime change could be seen as legitimate foreign policy tools, leading to American-inspired coups from Guatemala to Iran.84

Such moral relativism appeared to make sense, especially since communists were engaging in unconventional warfare across the globe. In Southeast Asia, North Africa, and Latin America, revolutionaries were avoiding decisive encounters with their enemies and relying on “indirect, irregular, unconventional strategies.”85 Their challenges, however, usually were local. Not so for the United States. Locked in a global contest to contain communism, nearly every spot on the map could be judged vital to US national security, thereby justifying almost any military means. And because the threat had materialized on America’s doorstep – Fury described “Crazy Ché” Guevara as the “toughest guy in the Western Hemisphere” – there seemed little alternative but to engage the enemy on his terms.86

But what if the threat was domestic as well? What if communist subversives, from Latin America and beyond, had infiltrated the United States and were planning to conquer the nation? Without question, men’s adventure magazines contributed to Cold War hysteria over this threat of domestic communism. Male, for instance, wrote of secret Red “subversion clubs” that were popping up in every American town, while For Men Only believed that communists had a “carefully built espionage setup in America.” South of the border, insurgents were attempting to build a “new Red dominion” in the Western Hemisphere and “take control of the Panama Canal.” These fears of communist subversion reached ludicrous heights. One Stag confidential from 1964 linked the ideological threat to what would soon become a national debate over reproductive rights. “Many of Cuba’s abortionists, refugees from Castro, are on the loose now in our southern states, giving America a whole flock of abortion centers.”87

Such irrational fears, present long after the political demise of Wisconsin’s infamous senator, were emblematic of Cold War McCarthyism. The constant dread of imminent war allowed political opportunists the chance to strike out at “Communists, near-Communists, and nowhere-near-Communists” with little concern for social injustices. Thus, equating the Communist Party with a “huge iceberg,” as did McCarthy, where the most dangerous part was “under water and invisible” made sense.88 Who had evidence to credibly question how deep the true threat went? In line with the macho pulps, wily politicians saw merit in conflating contemporary political issues with sexual anxieties. As “Tailgunner Joe” told reporters at an impromptu press conference, “If you want to be against McCarthy, boys, you’ve got to be a Communist or a cocksucker.”89

Even military men were not immune from castigation and charges of conspiracy. McCarthy undoubtedly overreached by accusing former five-star general and Secretary of State George C. Marshall of betraying American interests, but genuine fears endured that GIs might be susceptible to communist infection. Vietnam veteran Ron Kovic recalled his childhood certainties that communists “were infiltrating our schools, trying to take over our classes and control our minds.”90 In the January 1957 issue of Real Men, Mark Davis shared “The Red Plan to Conquer America,” in which a “weird Soviet-supported dope ring” was attempting to “sap the strength of American fighting forces.” This it did by turning thousands of GIs into “sick, helpless and almost insane dope addicts.” Man’s Adventure followed with a story on a US Army private who deserted during the Korean War, improbably catching the eye of Mao himself and becoming a “commander of the Communist Chinese terror-troops in Mongolia!”91

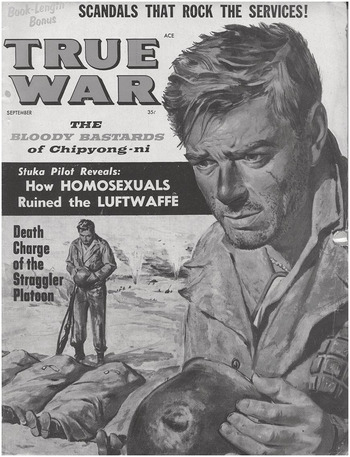

Overshadowing all these anxieties, the fear of nuclear Armageddon became part of daily conversations across Cold War America. In military circles, scientific laboratories, and popular media outlets, the possible end of civilization pervaded the cultural landscape. Naturally, the pulps contributed to what one anthropologist called a “fear psychosis” by asking frightful questions. “Can the Hell Bomb Destroy the World?” “What Are Your Chances for Survival?”92 Yet even here, men’s magazines could incorporate sexual innuendo into the mix. The “Barracks Beauty” for the September 1957 issue of True War, Marley Sanderson, was described as “radioactive” and an “experiment in atomic energy.” Sir! introduced Iris Bristol, a popular pin-up model, as a “Fallout Shelter Girl,” meaning “the girl we’d most like to come up out of the fallout shelter with.” In one 1958 account, which estimated more than fifty million dead from a nuclear war, Real War predicted “Women will be selling themselves for an apple – if it isn’t radioactive.” For young readers, would it not later be unsurprising that in war-torn Vietnam, women also would be offering themselves to American GIs for a morsel of food?93

Despite the awesome destructive power of nuclear weapons, adventure magazines ensured these soldiers remained central to the nation’s security. While nuclear war might be an “atomic-hot nightmare haunting every battle-tough pro in our armed forces,” courageous boys still could find a man-making experience in uniform.94 One pulp story from 1958 imagined an apocalyptic global struggle ten years into the future, “The Last War on Earth.” After Russian divisions crashed into Germany, the world plunged into war. In North Africa and the Middle East, Arab forces harassed their enemies but “lacked the courage or ability to overrun the ‘hated Americans.’” Meanwhile, back in Europe, the Russians “spent human lives with a callousness that shocked even hardened veterans.” While all sides employed new armaments, they were “only an adjunct to the basic and age-old weapon – the foot soldier.” Of course, the Americans prevailed because “in the last analysis it was the clash of men against men that tipped the scales. As in every war, the great ultimate weapon was man. To nobody’s surprise, G.I. Joe turned out to be far better than Commie Ivan.”95

Perhaps as a corrective to the potentially emasculating reliance on technology, the macho pulps drove home storylines in which real men protected the nation’s security. Stag, for example, ran a 1961 cover story on US Air Force Chief of Staff Curtis LeMay, “The American General Russia Fears Most.” While the article gushed over the Strategic Air Command’s bomber fleet, LeMay’s grit took center stage. “The way to win a war,” the general sparingly briefed his men, “is to hit the enemy hard and keep right on slugging him.” Not surprisingly, a few years later LeMay would be recommending to President Johnson that the US Air Force bomb North Vietnam back “into the Stone Age.”96

Only true heroes, warriors with the requisite “balls,” were capable of defending the nation – not just from communists, but from women right here at home.97

The Sexual Menace

In line with many contemporary depictions in popular culture, men’s adventure magazines presented multiple constructions of women. Some were decorative status symbols, akin to men’s private property that could be flaunted in public. Some were sexualized objects to be sought after. Others were damsels in distress, oftentimes innocent victims of war, “helpless, passive creatures who could only be saved by the heroic actions of brave men.”98 Still others were sexual predators, tramps, and femmes fatales who graced the pages of noir thrillers or, in the pulps, seduced Nazi counterintelligence agents and by morning had become their “willing slave.” As Woody Haut observes, regardless of how “they were described, women in pulp fiction culture were objects of male fantasy and obsession.”99

Photographic spreads of scantily clad women surely propelled many male fantasies. Taking their cue from World War II-era pin-ups, men’s adventure magazines regularly included photos of “cheesecakes,” women in seductive poses and various stages of undress. The pulps, though, portrayed their models differently than pin-up icons like Betty Grable or Playboy centerfolds. Hefner’s Playmates, for example, were crafted as sensual yet “sexually naïve,” provocative yet sweet, if not innocent-looking girls next door.100 While World War II pin-up Rita Hayworth might be seen as more erotic than wholesome, she still offered American soldiers a vision of romantic escape rather than cheap sex. In either case, these women were highly sexualized models fashioned for male gratification.101

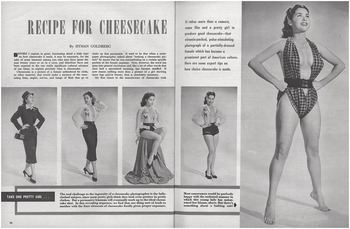

The pulps’ cheesecake girls, however, appeared far more lascivious. Alluring, “racetrack-curved” women promised both pleasure and sexual knowledge to the voyeuristic male reader. In “Recipe for Cheesecake,” Man’s Day laid out how a “persuasive lensman” could induce a girl to show “more legs and/or bosom” and how “professional clothes-shedders” made the “most willing subjects.” It apparently took little encouragement to get these women to strip off their brassieres or undress completely. “An amazing number of women,” the story recounted, “don’t wear panties, and it is even more amazing how many women who don’t wear panties forget that they are not wearing them when posing for pictures.” The pulps may not have explicitly represented the sexual act, but these pin-ups appeared to be offering a clear invitation.102

Fig. 1.5 Man’s Day, March 1953

Body measurements almost always accompanied these pictorial spreads, a way for men to rank order their “pulse-stimulating” pin-ups on an inch-by-inch basis. Moreover, the women were presented as one-dimensional, almost vacuous, sex objects. Cheesecake “comes naturally to Karen” read one spread in Man’s Magazine.103 In an interview with Real, model Lisa Varga was asked why she posed for cheesecake. “Because the photographers want me to,” she responded. After noting Lisa’s measurements, the interviewer queried, “Do most men try to seduce you soon after you meet?” He then asked if her build developed by itself or if she helped it along with “bust exercises.” By the late 1960s, Stag and Man’s Epic were sharing their first exposures of fully naked breasts, even as one model noted that “ninety percent of the men I’ve met were real wolves.”104

If men were wolves, then women must be damsels in distress in need of a savior. Of course, the pulps never wrestled with the contradiction that men needed to protect women from other men. Instead, damsels craving rescue advanced plotlines wherein the hero could prove his courage and generosity, and, if all went well, be sexually rewarded for his troubles. In such stories, Nazis proved a customary villain. American protagonists saved French girls from Nazi raiders, repatriated female nurses who unknowingly crossed over enemy lines, or ferried the “wives and daughters of local French politicos to safety in England.”105 In one tale, the hero bursts into a “pest-ridden female penal castle” to rescue “dozens of young, golden-bodied girls [who] were held in helpless bondage by sadistic, lust-crazed male guards.”106

Yet, even while being portrayed as helpless victims, women could not be trusted. Fears of social degeneracy and juvenile delinquency ran rampant throughout much of the 1950s, feeding anxieties that women in the postwar era were not meeting their societal obligations. J. Edgar Hoover, for instance, blamed moms’ “absenteeism” for the spike in postwar juvenile delinquency. War-worker mothers, the argument went, had fallen down on the job by not providing a decent home for their children, instead tempted to escape their household routines and earn a little spending money in war jobs. As the FBI Director claimed, the “lack of wholesome influences at home are contributing factors to youthful misbehavior.”107

These fear-mongers maintained that women exhibited the most alarming social misbehavior, especially young, single ones deemed to be from the lower class. Just as it underpinned discussions of martial masculinity, class loomed large in these debates. Women from “delinquent subcultures” often were portrayed as excessively independent and mature, the product of a “permissive” social climate that failed to set proper boundaries.108 They were rebellious troublemakers living outside of accepted sexual norms, painted as “loose” girls at the center of a teen pregnancy “epidemic.” In such popular narratives, women were not supporting their men as they should, but rather contributing to a society that seemed intent on undermining the traditional male role. In short, they posed a danger not only to men, but to society as a whole.109

Women supporting the war industry during the 1940s no doubt contributed to these worries. Yet it is important to note that Rosie the Riveter never truly upended larger social norms. Historian D’Ann Campbell concludes that “while the war certainly caused an increase in the average number of women employed, it did not mark a drastic break with traditional working patterns or sex roles.”110 True, the number of women working outside the home rose in the first decade of the Cold War, confusing conventional definitions of gender roles and challenging many women to rethink their identities in relation to their supposedly proper roles as wives and mothers. But, for the most part, traditional, patriarchal norms remained in place after World War II.111

In men’s adventure magazines, however, women of the postwar era apparently had shed their inhibitions and were creating sexual havoc across America. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the macho pulps tended to depict women as sexually liberated death merchants. Men wrote of “Young Girl Wolfpacks” who were “utterly nonchalant about sex,” terrorizing US cities, and making “male gangs look like Little Leaguers.” Clearly, a double standard was at play here. The pulps were offering men advice on how to get women to have sex with them, yet apparently many of those same women were vicious predators. Thus, in “Death Wore a Tight Bikini,” author William Ard described his female antagonist as an “undressed, murdering kitten.”112 Another tale on housing development sex parties blamed “destitute young Mothers” for turning public housing projects into “vice ridden jungles devoted to booze, brawls and alarmingly casual sex.” To ensure readers understood the class component, the author quoted a Washington psychologist who maintained that the “poor often have sex as their only pleasure. But they have it in abundance.”113

Even into the mid to late 1960s, as cultural norms already were shifting, the pulps remained wedded to storylines where “Beatnik Girls” and “Cycle Girl Gangs” thumbed their noses at society by “living for speed, sex, and violence.” In the 1966 “Sex Revolt of Young Society Girls,” Barry Jamieson wrote of the unconventional behavior from a “new breed” of good-time girls who could beat out “hardened sex pros in talent for far-out bedroom capers.”114 The list of hedonists ran long. Nymphomaniacs, “calldoll bait” bleeding soft-hearted Americans, lustful madams engaging in “all sexual activity” where nothing was barred. These women were as tantalizing as they were dangerous. “All-or-Nothing Girls” illustrates how generational changes seemingly were challenging traditional gender roles. “Throwing out the old belief that the male takes the lead in the act of lovemaking,” the article claimed, “this new breed of passion-starved young woman is re-writing the bedroom rules to satisfy her own, newly-liberated cravings – and the guy who doesn’t understand her needs would be better off living in a monastery.”115

Men might benefit from this sexual liberation, but the pulps left readers with the impression that women still threatened good social order. Worse, “tramps” were preying upon the armed forces, a phenomenon popularized in World War II by “Victory Girls” who notoriously swarmed around military bases in search of easy sex. (Congress passed the May Act in 1941 which made prostitution near these bases a federal offense.) Such “sex happy dames” remained after the Korean War, “parasites and vultures that feast on the loneliness of the Serviceman.” Of course, while female “scum” preyed upon “unsuspecting” soldiers, the GIs themselves were just on “the harmless prowl.”116

In 1960, Man’s Magazine presented a disturbing piece on sex and the armed forces. According to the story, “the uniform doesn’t corrupt the boy,” a clear intimation that it was the women in town who did. And yet, away from home, these poor, corruptible soldiers “often felt free to patronize floozies and brothels.” In one scenario, the “virginal” eighteen-year-old Bart, drafted and sent to Fort Bliss, is pressured by other GIs to go to Juarez, Mexico. Bart is “appalled by the bare-breasted whores” but is afraid to “seem chicken” in front of his comrades. When he finally accepts a Mexican prostitute’s offer, he not only remembers the army doctor’s warning that Juarez is a “venereal hotspot,” but also is “frightened of the brazen whore who attempted to force his sexual ardor.” In the end, poor Bart “simply could not arouse himself, and remained impotent,” leaving as “virginal as when he’d entered” the brothel.117

The contradictions in Bart’s story clearly escalate upon closer inspection. If American GIs were so moral, why were they actively seeking out prostitutes? Were the Mexican women taking advantage of the US soldiers or vice versa? And if sex was intended to be a man-making experience, what did Bart’s inability to perform say about his masculinity? (Of course, when he rejoins his pals he pretends to “have enjoyed the whore’s favors.”) Such incongruities also could be seen in portrayals of women not being loyal to their soldier. In a story on “Dear John” letters, Battle Cry derided female backstabbers for kicking a soldier “in the seat of his pants when he is most helpless.” Naturally, it was acceptable for the GI to play “‘housey-housey’ with fraulein or mama-san” overseas – at least the “woeful little women” at home had “family and friends to soften the blow.” Given that wives and girlfriends were expected to be obediently supportive while their men were away defending democracy, such sexual double standards hardly required further explanation by male pulp writers.118

Worse, female culprits could be operating from within the armed forces. One 1956 pulp story asked if army nurses were “saints or sinners,” suggesting that at least some were taking sexual advantage of combat GIs. The fact that white women were rare in World War II combat zones like New Guinea – the “native belles were hardly alluring by American standards of feminine beauty” – only heightened men’s temptations. Furthering sexual contradictions, Battle Cry even admitted that nurses required armed escorts at all times. “The plain truth was that the nurses were being protected from their own sex-starved countrymen.”119 Still, most narratives placed blame on promiscuous women. Thus, tramps disguised as nurses also competed with wartime American Red Cross volunteers and USO girls for men’s favors. Real War exposed these “bawds for the brass,” highlighting the girls “who drank the Scotch, played pound-the-pillow with the officers and often cleaned up big dough.” To ensure class issues remained in close view, the article reminded readers that these “dames … were all from well down the ladder.”120

Condemning lower-class “harlots” – they were “ubiquitous” in America, according to Philip Wylie – conveniently redirected male anxieties of women purposefully upending traditional sexual norms. Seductresses were not moral anchors of society. In subverting their femininity, they were chipping away at family and social stabilities so necessary to men dominating contemporary gender roles. Thus, even while men were out “doll-hunting,” they castigated “sexually reckless females” and “abandoned, man-destroying” women.121 In the process, even class issues could be overturned, as in one story where a twenty-nine-year-old socialite was “able to enjoy herself sexually only with men who are socially inferior to her.” According to Stag, she was one of “many thousands of ‘troubled women.’” Occasionally, men also could misstep in the sands of these shifting sexual norms. Real Adventure, for example, reported a doctor’s prognosis that increasing rates of vasectomies were leading to “more venereal disease, more illegitimacy among the young and more wife-swapping among the middle-aged.” So portentous had “that operation” become, that the physician wondered “where the next generation of children will come from?”122

Still, men’s adventure magazines reflected a widespread male unease that women were articulating themselves in ways that challenged prevailing sexual conceptualizations. Perhaps no better example could be found than in Betty Friedan’s 1963 The Feminine Mystique. Author and activist Friedan argued that women could no longer ignore that inner voice saying “I want something more than my husband and my children and my home.” Fulfillment as a woman meant more than just becoming a “housewife-mother.” The task was to move beyond the public images of housewives buying “washing machines, cake mixes, deodorants, detergents, rejuvenating face creams, [and] hair tints.” Instead, Friedan called for women to “accept or gratify their basic need to grow and fulfill their potentialities as human beings, a need which is not solely defined by their sexual role.”123

Such appeals for greater social and sexual freedoms sat uneasily alongside yet another challenge to Cold War gender norms. “The pill,” which was first approved for contraceptive use in the early 1960s, promised further shifts in the balance of sexual power and independence. If women could more freely choose when and how often to have sex, how could certain men not feel threatened? Indeed, many pulp writers were. One article on “sexually aggressive women” lamented how oral contraceptives had given the “American girl a sexual freedom she never had before … A great many women are so highly-sexed they insist on calling all the shots in the bedroom.”124 Man’s Magazine bemoaned the fact that men’s “dominant role is being challenged as more and more wives use oral contraceptives.” So confusing had this sexual state of affairs become that pulp writers were showcasing single “bachelor girls” who now were preying on married men. By 1967, a True Action story on the “new morality” demonstrated the outcome of women’s sexual independence – “quickie love affair girls” had made the “double standard … as outdated as grandma’s whale-bone corset.”125

Of course, gendered double standards never quite extinguished themselves. Real men could keep them alive and, if properly approached, benefit from these changing sexual norms. The challenge, for critics like Norman Mailer, was to fight against the “built-in tendency to destroy masculinity in American men.” By winning “small battles” in the bedroom or in combat – performance in one augured well for performance in the other – men could contest and even reverse their supposed decline.126 Take, for instance, Ian Fleming’s Goldfinger, in which James Bond is able to bed the “psycho-pathological” lesbian Pussy Galore. When Bond comments “They told me you only liked women,” she replies, “I never met a man before.” This penetrating masculinity surely served as an example for embattled men, a reassuring fictional release from the domination of the “new” American woman.127

Without question, men’s adventure magazines contributed to these misogynistic imaginings. Several articles highlighted the rewards of wife swapping, while Man’s Magazine posited that “outrageous sex demands” from husbands were often “harmless, healthy, legitimate desires.”128 In “How to Handle Those New Free Love Girls,” Men offered readers thirteen hints on handling “the astonishingly liberal-minded sexual behavior of many of today’s women.” Dr. Efrem Schoenhild began by arguing that women were never liberated from sex and that even “Man-hating women are by no means free of the attachment to the male.” To the doctor, women needed the “male influence” and a “man’s strength and solidarity.” After offering advice on arousing a woman’s curiosity and not getting “hung up” on her body, Schoenhild left men with an important message: “Remember, your role is to lead.”129

The pulps frequently intimated that well-to-do men held certain advantages in leading and, notably, in profiting from women’s sexual liberation. Just like Playboy, men’s magazines presented affluent masculine role models to whom working-class readers could aspire. Modern executives flew on private company jets and enjoyed mid-air orgies with “airborne vice girls.”130 For those who could afford a Caribbean cruise, they might catch a single woman like the one showcased in Man’s Illustrated. “When a girl like me goes on vacation, she wants to let off steam. That may mean a little drinking, a lot of laughs with good company and a liberal sprinkling of sack time with the right partner.” (There was nothing to worry about if this vacationer became “hot and bothered” since she was on the pill.) In fact, according to the pulps, it appeared as if “mod-affluents” had time for little else besides sexual tourism on the high seas. Bluebook noted that the liquor bill alone on one “pleasure craft bash” rivaled “better than a month’s pay for the average working stiff.” Apparently, this new version of freedom of the seas came with a hefty price tag.131

As young draftee Bart’s Mexican misadventure implied, though, keeping up with liberated women evoked plenty of sexual anxieties. Men now had to gratify themselves and their sexual partners. What if they failed to assert their virility? What if they disappointed in bed? The pulps tackled these fears in numerous ways. In one cartoon from Stag, a bride, still in her wedding dress, returns home to her parents carrying two suitcases. “Then, about four in the morning, Albert lost his luster,” she complains.132 An advertisement from the Vitasafe corporation hit upon a similar theme. A frustrated wife wearing lingerie and dark lipstick sits up in bed next to her sleeping husband. As she stares directly into the camera lens, the ad cries out “He Didn’t Even Kiss Me Goodnight!” Lastly, in “The Failure,” readers confront a man who has left his wife but cannot perform with his newfound mistress, silently “raging helplessly at this stupid, worthless body.” The article failed to mention what this impotence may have suggested, though by story’s end our adulterer has little remorse for cheating on his wife.133

Fears of not being able to perform sexually in this new age engendered one final anxiety, perhaps the most disquieting of all. If men could not derive pleasure from or provide pleasure to women, might it be possible they were gay? The 1948 and 1953 release of the sexual behavior studies collectively known as the “Kinsey Reports” left in their wake a frenzied debate over how Americans should define “normal” sexual conduct.134 Alfred Kinsey, a biologist by training, revealed a wide range and variation of sexual activity – some eighty-five percent of his subjects admitted to premarital intercourse and sixty-nine percent had sex, at least once, with a prostitute. For the pulps, though, Kinsey’s finding that thirty-seven percent of adult men had engaged in homosexual activity to orgasm presented a troubling conclusion. In Barbara Ehrenreich’s words, gay men could be viewed as “failed” heterosexuals, an admission of “defeat” on the part of American manhood. While the macho pulps openly repudiated those in the gay community, the disquieting fact remained that impressionable young men might be vulnerable to the contagion of homosexuality.135

This homophobia ran rampant in the macho pulps. To American Manhood, homosexuals were “simply mentally sick people and should be regarded as such.” Apparently, though, young men constantly needed to guard their masculinity as some boys became gay after “being taught by older persons while they were in their formative years before puberty. This is one danger all young boys are subject to.” Man’s Magazine published an exposé on “New York’s Homosexual Underground,” written by a reporter who posed as a gay man for twenty-four hours. In imparting what he saw – “the pathetic, the bizarre, the sick” – the author admitted that most of it “would make a normal person want to vomit.” When the intrepid reporter, for instance, meets Billi, a “queen’s queen,” it is clear that the nightclub inhabitant isn’t a real man. “I shook hands with him. It was like grasping a limp piece of putty.”136

In other stories, wives could “go lesbian” or men might unsuspectingly marry one since “scientific investigators [had] discovered that better than 50% of all women have some lesbian tendencies.” Perhaps unsurprisingly, the pulps ran more than a few accounts on electric shock therapy to treat this alleged ailment. So alarming had the threat become that Americans considered adopting methods of relief from foreign enemies. As Male related, the “Russians may have come up with a surefire way to cure homosexuals. They’ve been using electric shock treatments … After 28 horrible treatments most of the deviates wind up cured and get married to girls.”137 Some men and women went further, electing for sex change operations that left even sympathetic pulp writers astonished. One author deemed transgender people a “true legion of the damned … incredible victims of a colossal blunder by Nature.” Through the “wizardry of modern medicine,” one former GI, George Jorgensen, Jr., transformed into a “beautiful woman” and could “now look forward to a happy and a normal marriage.”138

Jorgensen’s reassignment surgery, which garnered national attention at the time, incited further unease that the homosexual menace might undermine military readiness. Sexual perverts might infect straight soldiers, resulting in sissified armed forces unable to defend against the communist threat. Popular conceptions held that homosexuals were emotionally unstable, prone to panic, and filled with neuroses – hardly traits needed to win on the modern battlefield. In fact, True War shared an ex-Stuka pilot’s tale of how high-strung, hysterical “perverts” had ruined Hitler’s air force. Misconstruing T. E. Lawrence’s sexual orientation, Sir! described Lawrence of Arabia as both desert fighter and woman hater. “Captured and tortured by a homo caliph, he may have come to believe he was a homo, too.” Under the strain of combat, even the most celebrated western guerilla fighter might be turned into a homosexual.139

If Lawrence of Arabia was vulnerable to infection, how could the US armed forces inure their own draftees from homosexual contamination? At induction centers across the country, the threat seemed real enough. Gay men might blend unnoticed into the military ranks, causing unseen havoc, or, if discovered, bring discredit to the armed forces. The toughest “thing a psychiatrist at an induction center has to determine,” Stag declared, “is whether a man is homosexual. Some homosexuals try to pass as heterosexuals in order to get in. Some try opposite tack – play being ‘queer’ in order to stay out.” Male was certain there were “high ranking military men hiding homosexual pasts,” thus “easy marks for strong-arm extortionists.” The macho pulps made it adamantly clear to their readers. Homosexual men and women posed a clear and present threat to Cold War society and, in particular, the US armed forces.140

And yet gay men ranked among adventure and muscle magazine consumers. George Takei, Star Trek’s Sulu, was one of them. Growing up in a Japanese American internment camp as a young gay man, he later recounted reading these magazines because they offered a way to look at strong, attractive men in slinky bathing suits while keeping his own sexual preferences hidden. In fact, some of the earliest American homoerotic photographers – Bruce of Los Angeles and Lon of New York – ran ads selling “Dramatic Dual Photos” where the “physiques emphasize the dramatic impact of the pose.” Bruce marketed “Cowboys of the West,” glossies of ruggedly handsome young men in cowboy hats, hyped as “distinctly different source material on the man of the range.” These appeared in the same magazines where writers declared homosexuality a mental illness or a “maladjustment of glands” that could be cured by heavy physical exercise.141

Of course, magazine editors had to navigate these waters carefully. At the height of the “lavender scare,” sexual inquisitions had been swept into the larger anti-communist crusade. Publishing homosexually oriented material came with the risk of censorship or, worse, indictment for obscenity. By the mid 1950s, as Andrea Friedman notes, most commentators “understood homosexuality and Communism to flow from like sources – moral corruption, psychological immaturity, sex-role confusion – and to pose similar dangers to the nation.”142 Perhaps in this way, pulp readers saw themselves as righteous citizens, protecting American masculinity while safeguarding the United States from threats at home and abroad. In an ironic twist, though, World War II itself had contributed to the rise of “homophile” organizations intent on discreetly but more successfully integrating gay men and women into American society.143

All told, the multitude of Cold War anxieties left many men in an uneasy state. Fears over sexual performance and inability to provide for one’s family. Fears of communist subversives and of nuclear Armageddon. Fears that women were emasculating men and “taking charge of sex relations.” Of course, not all men shared these concerns. It seems probable, though, that pulp readers more intimately felt the weight of these uncertainties. They might have been more inclined to suffer from economic disparities in the 1950s and 1960s. They likely were in the position to be more frustrated when the women in adventure magazines – so desirable yet so dangerous – never materialized in real life. They may have been more predisposed to accept the pulp narrative that communist women and “savage” locals were far different from the pretty cheesecake fantasy living in Hometown, USA. Or worse, readers worried that when American women rated their “menfolk,” they were not measuring up to the idealized sexual conquerors inside the pages of the macho pulps.144

If pulp definitions of masculinity emerged as fragile in relation to women, then perhaps one’s manhood could better be demonstrated on the field of battle. There, at least, men could be liberated from the “castrating scissors” of female thighs. What better way to transmit these martial virtues to young men than through the shining example of their fathers who had served so valiantly in World War II?145