The study of the ancient Mediterranean world has traditionally been a hotbed of ancestralist rivalries and competitive modern genealogies (nationalist and cosmopolitan, Christiano-centric and anti-Christian). This is especially true for what have been – from a European viewpoint – the privileged cultures of Greece and Rome. No account of Roman religion can be free of centuries of layered debate on these issues: consciously or unconsciously, the field is a tangle of constantly outdated ‘presentisms’ deriving their authority from accounts of a special, shared and collective past.Footnote 1 But Roman religion has a very special place within these narratives: it is not Christianity – it represents the past before the continuing Christian present, which Western scholarship has either upheld or detested since the Enlightenment – and it is not Greece, wherein the highest cultural and philosophical ideals of Europe were always vested. In no other field with which this book is concerned are the self-contradictions of a long history of varieties of investments more directly manifest, than in the subject of visual and material culture in relation to Roman religion.

Let us begin, as histories of Roman religions never begin, with an object. Of all the types of object we have from the Classical past, perhaps none so typifies our sense of ancient religion as the altar (Figure 3.1).Footnote 2 Altars are everywhere, with an impressive spectrum of possible artistic embellishments, inscribed ancient languages and contextual settings. They impel us to think of what many see as the defining ritual that differentiates religions in the ancient and the modern periods, ‘paganism’ from Rabbinic Judaism or Christianity, polytheism from monotheism: the act of blood sacrifice.Footnote 3

Figure 3.1 Raphael (1483–1520), The Sacrifice at Lystra (Acts 14:8–18, where the Lystrians offer sacrifices to Saints Paul and Barnabas after they have cured a lame man). Bodycolour on paper mounted onto canvas. Cartoon for a tapestry in the Sistine Chapel, commissioned by Pope Leo X and unveiled in 1519. Height: 350 cm, width: 560 cm, made c. 1515–16. Victoria and Albert Museum, on loan from the collection of Her Majesty the Queen.

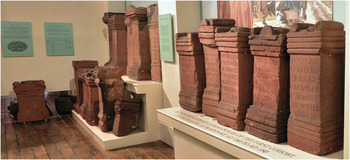

In 1870, a spectacular concentration of altars was discovered at the Roman fort of Alauna – modern Maryport – in Cumbria, Britain: seventeen sandstone altars were found buried in pits in a field.Footnote 4 Many carry inscriptions, most with dedications to Iuppiter Optimus Maximus (Jupiter Best and Greatest), and many have friezes with geometric decoration (Figure 3.2). Further finds followed in later years, in addition to discoveries from the eighteenth century and earlier, and it is for this collection of altars that Maryport is best-known. Individually, the altars are not particularly remarkable; there are many examples of sandstone altars dedicated by Roman soldiers from Britain, they are not especially well-carved; the choice of deity is not unusual. What makes them stand out is their number, and the circumstances of their burial.

Figure 3.2 Altars in the Senhouse Museum found at Maryport, UK. Dedicated in the 2nd century AD by the ‘I cohors hispanorum’ and their various commanders. Sandstone. All of a square type, but no two altars are the same either in dimension or decoration. Senhouse Museum.

Nevertheless, they afford some information about the religious life of those who lived there in the past. They point to the names of gods – important foci of worship; they provide names of individuals and groups too, offering a social dimension; the form of the altars speaks not only to religious practice, but to traditions in religious dedications, and the quantity of them might point to degrees of popularity. But to what extent, in interrogating such issues, is it appropriate to divide the totality of any one of these material objects into separate empirical chunks? Is it legitimate to focus only on the name of the god without considering the dedicant, the object’s form, the decoration and the find context? These points, quite simple when levelled at just one object or a small assemblage, become more complex when expanded to the entire group. How do we relate one of these altars to the others found or to the site as a whole? How do we compare this site to others? And how do we relate them all to evidence for ancient religion more generally, including to varied forms of text written in different languages, and to an enormously varied visual and material world?

These questions circle around issues of evidence and the disciplinary specialists who contend with them, in particular historians, art historians and archaeologists, all of whom work on religion in the ancient world. The desire to cross disciplinary divides in order more effectively to study ancient religion – and in this chapter, in particular, Roman religion – has long existed. But a fundamental challenge remains. This is an issue that will become familiar over the course of this volume: the problem of commensurability. Is there a way of interpreting any one of these altars from Maryport so as to grant equal weight to its inscribed text, artistic features, and archaeological context? One of the aims of this chapter is to interrogate the ways ancient historians, art historians and archaeologists approach objects like these altars, and to examine how the questions asked of them are burdened by the preconceptions of each discipline. Can such objects of material and visual culture function in the writing of Roman religion, and in the writing of history more broadly?

Part of the challenge in the field of Roman religion, and its material culture more broadly, lies in the history of the disciplines. We start from the premise that Roman religion, as a set of practices and rituals with a series of objects and buildings as its accoutrements and setting, was fundamentally rooted in visual and material culture. Scholarship on Roman religion and Roman art has painted the two in parallel lines. Richard Gordon neatly encapsulated the disciplinary difficulties: ‘The “experts” on ancient religious art are art historians, not historians of religion.’Footnote 5 To these one might add a third: archaeology. Despite Gordon’s acute observation – articulated in the late 1970s – the absence of a sustained dialogue between ancient history, art history and archaeology remains a problem for discussing the materiality of Roman religion. To bring together different methods and media that would allow us to work with them in an even-handed fashion is one of the biggest challenges currently confronting the study of ancient religion.

Roman religious art, inasmuch as it can be distinguished as a category at all, has traditionally been seen mainly as art and not as a set of empirical data with a broader relevance for the history of religion. Roman religion as a topic of interest comes under the purview of Ancient History, and the study of it is to a great extent influenced by the preferences of this field for a dependence on textual sources (including epigraphy). The historic gap between the three disciplines concerned in different ways with the Maryport altars – ancient history, art history and archaeology – has affected the ways ancient religion has been written. This requires an examination of the different priorities of these three disciplines in approaching ancient religion, and religious material culture.

This chapter looks at each discipline in turn, starting with ancient history, and moving to Roman art and archaeology. These sections address some of the historical reasons for the lack of a meaningful language for the discussion of Roman religious material culture. We use the example of the Maryport altars to illustrate the divergent approaches each field can take to the same objects. The conclusion emphasizes the modern scholarship that is challenging the old narrative of parallel lines, and is starting to draw them together.

1. Historians’ Constructions of Roman Religion

An altar should be a good introduction to the materiality of Roman religion. It is a physical witness of sacrifice, arguably an actor – with agency (culturally contingent on its ritual context, to be sure) – within performative religion. Any example should be useful to historians interested in sacrifice as a transactional process between the human and divine worlds, as an instantly identifiable part of ritual, indeed a key setting for its action. But rather than focusing on the objects on which sacrifices were performed, historians have approached sacrifice – and indeed the study of ritual more generally – through the traditional medium of texts.Footnote 6

How might historians approach the Maryport altars? Can they be more than illustrations of a ritual setting or used as support for claims founded on the priority of textual sources? One starting point is with their inscriptions, which tell the viewer something about the dedicant, the god or gods to whom the altar was dedicated and the provincial epigraphic habit.Footnote 7 Let us examine one altar in particular, known (after its inscription, just to emphasize the priority of the written) as RIB 823, made from red sandstone probably in the reign of Hadrian (about 130 AD) and excavated before 1725 (Figure 3.3).Footnote 8 Its inscription reads:

This may be translated as: ‘To Jupiter Optimus Maximus. The First Cohort of Spaniards, which is commanded by Marcus Maenius Agrippa, tribune, set this up’. The First Cohort of Spaniards is first attested in Britain in the first century AD; members of this cohort are responsible for most of the inscribed altars found at Maryport.Footnote 10 In addition to this offering by the cohort as a whole, Maenius Agrippa dedicated at least three other altars, all as tribune; this, along with the testimony of the other finds, suggests that there was a strong tradition of dedicating altars to Jupiter Optimus Maximus among these soldiers.Footnote 11 The choice is not unusual; this epithet belonged to the temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline in Rome, and signified his worship as supreme god.Footnote 12

What can the rest of the altar tell us about Roman religion? It stands as a signifier of religious practice; does its function as an altar make it a sacred object? Was it intended as a specific indication of the cohort’s religious identity as a collective, of Agrippa’s own personal religious and social identity, or was it the kind of ubiquitous dedication that people in his position normally made, in this case attributed to the cohort as a whole?Footnote 13 As an object, it perhaps throws up more questions than it provides answers. But this should not be seen as a hindrance to studying religious material culture. Its very elusiveness as an object – particularly when compared to the more concrete nature of its textual inscription – gives an insight into why altars, such as those found at Maryport, have been largely disregarded in the writing of the history of Roman religion, unless they were major surviving monuments of the past, such as Augustus’ Ara Pacis.Footnote 14

What Is ‘Roman Religion’?

Ancient history as a discipline has largely left material culture – with the exception of epigraphy – to archaeologists or scholars of ancient art. This section therefore focuses on Roman religion itself: in what ways it exists as a category, and whether it is workable as an adjectival label to hang onto material culture. It addresses two major problems for the study of Roman religion: the lack of a coherent definition and the traditional preference of historians for textual sources. These are by no means the only two problems for the field, but the specific interest of this chapter in finding a viable unified language of discourse brings them particularly to the fore.

The hope of finding a clear definition of ‘Roman religion’ is both unrealistic and anachronistic. The subject is vast, and encompasses great temporal, geographic, linguistic and categorical variation. Its start and end dates are imprecise, and subject to debate. If we begin with the foundation of Rome, should we incorporate mythology into the religious history of the city? To what extent do these origins frame the religious landscape of the Republican and Imperial periods? Moreover, the search for an end date could take us up to the reign of Constantine and the advent of legalized Christianity (AD 306–337), to the fall of Rome (AD 476), or even to the fall of Constantinople (AD 1453) depending on whether our emphasis is on traditional polytheistic worship, on the city of Rome, or on the survival of aspects of a pre-Christian imperial model in Byzantium.Footnote 15 The geography of the subject covers the sprawl of the Roman Empire, including local, civic, provincial and state-sponsored practice, as well as the spread of new forms of religious worship through diaspora and mission.Footnote 16 And how far can Romano- or Italo-centrism be allowed to define religion in the context of an empire spanning the entire Mediterranean?

The categorical variation in what constituted religion is especially difficult to convey. The term ‘religion’ covers the traditional collection of gods at Rome, the advent of new and local gods from across the empire, the role of the state in propagating cultivation of imperial cults (however we may understand them), the longevity of ancient traditional civic and rural polytheisms, the place of magic, the beliefs of a household and the role of individuals in choosing a personal form of worship that suited them best, the range of so-called mystery and initiation cults, the differences between local religions and more universal ones. It raises questions about the role of sacrifice versus other ritual acts, such as the sprinkling of incense or libation,Footnote 17 the distinction between public and domestic worship, and understandings of belief.Footnote 18 It even includes early forms of the modern world religions of Judaism and Christianity, which we might no longer consider to be particularly ‘Roman’, but played significant, even transformative, roles in the Roman religious landscape.

There is no precise ancient definition of religion, no straightforward Greek or Latin term that the modern scholarship can adopt, and this makes the task of approaching the subject more complex. As such, the study of Roman religion may seem frequently to depend upon the preferences and interests of individual historians or to be subsumed into wider historical fashions and trends. Nonetheless, definition continues to be the key to exegesis for many scholars of ancient religion. One of the main problems lies in our restricted linguistic choices for discussing religion: the terms that we use, and the conceptions of religion that underpin them, are inevitably informed by our experience of modern world religions. The approach of many ancient historians educated in Europe or America has therefore been shaped by a Christian legacy of writing about religion and has frequently been a reaction to it.

Despite these complications, the characterisations of some of the field’s most important figures continue to colour scholarship. For Theodor Mommsen, the great nineteenth-century Prussian historian, Roman religion was cold, formalistic, and state-controlled:

it was of a very earthly character, and scarcely different in any material respect from the trembling with which the Roman debtor approached his just, but very strict and very powerful creditor. It is plain that such a religion was fitted rather to stifle than to foster artistic and speculative views.Footnote 19

The message is clear: compared to the more spiritual character of monotheism, Roman religion was transactional, legalistic, and based on social models of reciprocity and justice.Footnote 20 Rather than seeing religion, Mommsen saw the Roman legal system, replicated in different social structures; in essence, Mommsen denied the very religiosity of Roman religion. This is to say that he denied that Roman religious structures had more than a social purpose: they were the opposite of personal, spiritual – and Protestant – approaches to Christianity.

Defining Roman religion from a social – or even a state – perspective is widespread. One approach has been to emphasize certain aspects of Roman religion that speak more to social, economic or political structures than to religious elements per se.Footnote 21 The project of integrating Roman religion into wider Roman society, and into particular social structures, has enjoyed widespread popularity; the methodologies involved have varied, almost from historian to historian, though certain themes and terms have gained especial purchase. The mid-twentieth-century German historian Franz Altheim clearly saw Roman religion as an intrinsic part of all other areas of life in the Roman world, which should not be separated from them without losing something of its nature:

A history of Roman religion, as a special subject of study, can only be orientated by a history of Rome in general. It can only be understood as a part of a coherent whole, which, regarded from another standpoint, presents itself to us as the history of Roman literature, of Roman art, of Roman law, and which, like every history, has its focus in the history of the state.Footnote 22

The conception of Roman religion as inherent in all other areas of Roman society, that collectively focused on the state – which in Altheim’s work of the 1930s and 1940s had distinct debts to National Socialist ideology – would later give rise to the idea of an ‘embedded’ religion, that could not be separated from Roman literary, artistic, legal and political life along the lines by which we comprehend religion today.Footnote 23 This template for seeing religion as an intrinsic part of society is closely related to the polis-religion model of work on Greek religion.Footnote 24

Recently, there has been a surge of interest in finding the voice of the individual in history, including in the history of religion.Footnote 25 The recognition of the power of individuals can also be seen explicitly in what one might call the ‘late-Capitalist’ model of a competitive religious marketplace in the Roman world.Footnote 26 The focus on the individual allows scholars to bypass some of the difficulties inherent in changing conceptions of religions and social structures; the centre of research revolves around the individual at a certain time and in a certain place, and the ways in which her or his identity was shaped.Footnote 27

These approaches – which are by no means exhaustive – are wide-ranging and potentially incompatible; it is perhaps understandable that there has traditionally been a reluctance to address the issue of how to integrate into this already-heady mix the study of religious material culture. The French school of ancient religion took visuality and archaeology seriously, notably in the work of Jean-Pierre Vernant on ancient Greece,Footnote 28 and of Romanists in the wake of Robert Turcan and John Scheid.Footnote 29 The landmark publication in 1998 of Religions of Rome by Beard, North and Price included an entire volume dedicated to sources with literary and epigraphic texts presented alongside images.Footnote 30 But none of this can be described as a fully equal integration where material culture is the driving empirical data for the study of Roman religion, rather than the illustrator of texts.

In using the term ‘Roman religion’, one must acknowledge its many imperfections: it can imply the predominance of the city of Rome, ascribe unity to a widely disparate number of religious beliefs and practices based on geography and empire, and it forces us to subscribe to the cult of catch-all expressions. But it can nevertheless prove useful. Roman religion might better be understood as an amalgamation of religious forms, ideas or practices in the Roman period.Footnote 31 It is a necessarily imprecise term that can allow us to think in terms of connections, without implying uniformity. It is this very imprecision that has the potential to allow scholars to work more with material culture, not forcing readings on the material, but allowing it to speak. As the search for absolute definitions of Roman religion have given way to more open approaches, material culture has more opportunity to play a part in scholarly conceptions.Footnote 32

The Privileging of Texts

Nonetheless, there remains a discernible preference for textual, and particularly literary, sources. This emphasizes the instinctive bias and training of many ancient historians and is an inclination that has led ancient historians to look for texts in order to understand Roman religion. In Christianizing the Roman Empire, Ramsay MacMullen questions the biases of historians:

We ourselves naturally suppose, immersed as we are in the Judeo-Christian heritage, that religion means doctrine. Why should we think so?Footnote 33

One response to his question could be that our modern understanding of doctrine, and hence of religion (if ‘religion means doctrine’), frequently depends upon texts. Nonetheless, while ancient historians are unlikely to express an explicit interest in Roman religious doctrine, this can appear to be the aim of those who focus on texts at the expense of archaeological material.Footnote 34 A recent movement towards the intellectualization of Roman religion has reinterpreted certain Roman texts as attempts to articulate and describe religious activities and behaviours.Footnote 35

One of the most famous of such texts, Varro’s Antiquitates rerum divinarum was dedicated to Julius Caesar in 46 BC. Although the full work has been lost, sufficient quotations survive in Augustine’s De civitate dei for a partial reconstruction. The treatment of religious material culture – in particular, the use of images of the gods – is especially interesting. Varro claims that the ancient and original form of Roman religion did not use images of the gods, and that this led to a purer relationship with the divine; the introduction of images, by contrast, had brought about a lessening of fear and an increase of error.Footnote 36 A similar argument is put into the mouth of Lucilius Balbus in Cicero’s De natura deorum (43 BC). Balbus posits that images of the gods, which teach worshippers how deities look and dress, have brought about a perversion of religion.Footnote 37

Such texts are not value-neutral guides to visual culture in Roman religion. Varro espoused an erudite, complex and hybrid position with debts to Academic, Stoic and Cynic philosophy, and this is evident throughout the Antiquitates;Footnote 38 in De natura deorum, Cicero creates a philosophical dialogue to examine religion. Both of these writings reveal the preoccupations of their authors: tradition and status (as exemplified through rituals and priesthoods), and a fast-changing political landscape in the late Republic in which ‘old’ values were becoming obsolete. While they – and others like them – provide information on certain factual points, and an excellent presentation of a particular apologetic position within a complex debate, they give neither a full picture, nor an unbiased one.

If some of the key internal Roman accounts argue against the importance of visual culture to religion, it is hardly surprising that this stance has been echoed by subsequent historians. The preference given to textual over material or visual evidence is in part due to a tradition of writing history, from a German Protestant heritage in particular, in which words, and the understanding gained through reading texts, has long been valued over the use and interpretation of images and material culture.Footnote 39 This model has habitually written religion out of texts, at the expense of the wealth of religious visual material from the ancient world. Yet relying upon textual evidence raises several problems: it tends to privilege elite and literate voices, it reduces visual evidence to the role of an aesthetic supplement, and it may over-simplify history. The focus on texts can overlook not only the value of material and visual evidence in reconstructing a more comprehensive picture of religious behaviours, but also the important contribution that can be made by more cognitive approaches to religion.Footnote 40 The bottom line is that – today as in antiquity – religious practice and imagination cannot be separated from the spaces, decorations, objects and implements with which and within which devotion is practised. The question is to what extent scholarship can grasp this experiential world.

2. Art Historical and Archaeological Formulations of Religion

Can images, objects and physical contexts be employed to cast different kinds of light on Roman religion? What questions would we like them to answer, and what are the limitations that their forms impose? If the questions that we ask of material culture were initially designed for an entirely different form of evidence (i.e. for texts), they are bound to lead to unsatisfactory conclusions. This is a simple point, though one that is often overlooked: we either must change the type of answers we want, or change the questions.

Material culture is by its nature particular. We can group and categorize images, objects, types of building and so on, but when we assess them, they are rooted in the physical world.Footnote 41 Traditionally, that physicality is itself approached through two – not always compatible – disciplines: archaeology (addressing material culture) and art history (addressing visual culture). Most scholars today would agree that the modern notion of ‘art’ cannot be applied to the ancient past without careful consideration. The resulting discussions have taken a number of routes, including the search for the beginnings of art history and a form of artistic appreciation in the ancient past itself.Footnote 42

Others have questioned whether ‘art’, or perhaps ‘Art’, is a suitable term at all.Footnote 43 These discussions demonstrate the subjectivity of the word, but equally indicate the continuing desire to grant to material objects the power to move us in the way that ‘art’ as a descriptive category suggests.Footnote 44 While much of the evidence that art historians and archaeologists may call upon is the same, and any division is ambiguous, the fact remains that Classical art historians and archaeologists are frequently different beasts with different methodological choices. This is well illustrated in studies of ancient religion. Michael Squire wrote recently that, ‘any division between (“subjective”) art history and (“objective”) archaeology is a chimera of our own modernist making’.Footnote 45 This creature has long existed. The histories of the two complementary fields are necessarily intertwined, but they are different disciplines with distinct modes of analysing their chosen material.Footnote 46

Roman Art and Religion: Category and Style

Our Roman altar from Maryport (Figure 3.3) has never excited the interest of art historians. It is debatable whether it possesses ‘artistic’ elements at all – it lacks figural representation that for many would raise it above the ‘decorative’;Footnote 47 and its features are so common as to express little individuality. They are coarsely executed in a simple way, and not of great quality when compared to other ancient material. On the other hand, the ornamental roundels with rosettes at the top are sufficiently distinctive to have aided the restoration of a missing corner only excavated in 2011.Footnote 48 This form of ornamentation is characteristic of a number of other altars at the site (notably RIB 826, which was also dedicated by Agrippa although this has an additional circle and dot motif), but less elaborate than the demi-lunes, zig-zags, vegetal scrolls and ribbing found on other altars in the Maryport group. This altar, to be blunt, is not evidence that art historians are likely to engage with. This raises two interconnected questions for this section: first, what has historically constituted ‘art’, in particular ‘Roman art’?; and second, what is ‘religious art’?

The usefulness or even the validity of Roman art as a category has historically been in doubt. Traditionally, Roman art has been a disciplinary placeholder between (the glories of) the Greek tradition and the advent of the (decadent) Middle Ages.Footnote 49 Even when granted autonomy, Roman art existed either as an offshoot of Greek art or as a passive body under the influence of other artistic cultures; at its best it was an emulation of Greek or a precursor to late antique artistic developments; at its worst a symptom of decadence and decline.Footnote 50 The independent study of Roman art as a positive phenomenon in its own right was born very late – at the end of the nineteenth century – in the Viennese work of Franz Wickhoff and Alois Riegl. But it was always regarded as a mixed bag – not a pure result of a single spurt of ethnic genius (as in Greece) but a dualism or pluralism of eclectic styles, classes, racial and cultural impulses that ultimately depended on a large, pluralist and culturally mixed imperial system comprising many languages, visual styles and cultural traditions.Footnote 51 That pluralism is specifically parallel to the well-known religious pluralism of the Roman Empire.Footnote 52 This sense of Roman visual culture as derivative of Greek, with little value accorded to models of replication or the eclectic and creative use of existing visual categories to generate new models of meaning and representation until the last generation,Footnote 53 was thus accentuated by the plurality of variants found throughout the empire. It is this lack of founders, originators and most importantly ‘artists’ that led to a prevailing view that Roman art, particularly portraiture with veristic tendencies, lacked the ‘spiritual animation’ of the Greek classical ideal.Footnote 54 The legacy that it has imparted to Classical art history is the repression of possible religious meanings in artistic material, from the Classical Greek period through to the advent of Christianity as the state-endorsed religion of the Roman Empire.

The wedge between art and religion is not easily removed: to discuss religious art is not necessarily to discuss religion. In several texts from the late nineteenth century onwards, a great many artworks were brought together and assessed precisely because of their ‘religious’ character.Footnote 55 But such corpora failed to turn discussion of the art under examination back onto religion, or to do so without being constrained by textual accounts of what religion should be. These were art historical accounts of religious material, not religious histories. Though not greatly concerned with religion, two seminal works published in 1987 encapsulate the move for Roman art to speak back to and about society. These were Paul Zanker’s Augustus und die Macht der Bilder, and Tonio Hölscher’s Römische Bildsprache als semantisches System.Footnote 56 Establishing an approach that still invigorates the discipline, these texts enabled a view of the ingenuity of Roman art as lying in the creative use of earlier, even preconceived, styles, forms and media to convey different meanings from those intended when those models were created (whether in Classical or Hellenistic Greece, or earlier in Rome, or in Egypt or in the near East).Footnote 57 Defining Roman visual culture in these terms meant that it had more wide-ranging implications for use as evidence in historical questions – including the study of ancient religion – than had been possible before.Footnote 58

Since the 1980s there has also been an increasing number of art historians interested in religion. In 1981 the first volume of the great iconographic encyclopaedia of ancient mythology, the Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (LIMC), was published, its run finally finishing in 2009.Footnote 59 This was followed by the specifically religion-centred iconographic Thesaurus cultus et rituum antiquorum (ThesCRA) published between 2004 and 2006.Footnote 60 The Institute of Religious Iconography at the University of Groningen published its annual ‘Visible Religion’ between 1982 and 1990 with several contributions from Classical scholars, and at the end of the decade, David Freedberg’s The Power of Images was published, dealing with all manner of magical and religious manifestations of art across cultures.Footnote 61

But with what might be described as ‘degree-zero’ art-historical objects without much distinctive iconography, like the Maryport altar, there has been little attempt to find a language or means for including them into a historical account of religion, despite the fact that they offer such rich and extensive primary evidence for religious practice and its accoutrements.Footnote 62 Not only has scholarship failed to make such things speak back to social formations, it has failed to find a way of letting them speak at all.

Archaeology and Religion: ‘Ritual’ versus ‘Religious’ Classification

The role of archaeology for the study of religion, and Roman religion in particular, might seem to be self-evident.Footnote 63 The enormous number of images of gods in one form or another, of temple complexes, and other paraphernalia (prominent amongst them, altars), contextualizes and helps us visualize the ancient world. It is evidence that religion left its mark. But the extent to which it is possible to analyse archaeological remains in order to assess religion is debatable: what exactly can one hope to ascertain?

When the largest collection of altars from Maryport was found in 1870, questions immediately arose as to why they had been placed there.Footnote 64 Laid in a series of pits, the altars had clearly been removed from their original stations, but had evidently achieved a new and deliberate position that could reveal a particular form of behaviour. Initially it was supposed that the altars were buried for safe-keeping by those who had used them for religious purposes,Footnote 65 possibly as a result of military invasion.Footnote 66 Half a century later, it was suggested that they had in fact been buried year on year, in a kind of ritualized pattern, following the dedication of a new altar at the start of the year.Footnote 67 At the end of the 1990s this hypothesis was discounted because the supposed ritual of burying was shown to be without basis.Footnote 68 In 2012, following excavations the previous year, the burial of the altars was shown to coincide with the building of a large timber-frame structure, meaning that the stones were used as packing material.Footnote 69 In other words, interpretive assumptions shifted from a fantasy of residual and resistant paganism preserving its sacred objects via a model of ritual ideology to straightforward pragmatism.

What the studies of the Maryport altars have in common is a focus on classifying the act of burial.Footnote 70 The need for systems of classification is particularly pronounced in archaeology, and because of this we may propose two questions about the discipline’s development from the late nineteenth century onwards. First, what influenced the formation of the classification system that determined what was and what was not ‘religious’? Second, what has been the impact of ‘ritual’ as a means of classification, and what is its relationship with understandings of religion?

The tendency to want to refer to an object as being either one thing or another has persisted.Footnote 71 Such categorization became, to a greater or lesser extent, a dichotomy separating the religious from the unreligious, spurring the kinds of distinctions that still govern how many archaeologists ‘do’ religion: looking for the abnormal and irrational to characterize something as ‘religious’- or ‘ritual’-based, against their descriptive opposites.Footnote 72 That reflex for identifying ritual objects reveals much about how religion has become relegated to the eccentric category of the socially non-normative, an unfortunate and anachronistic result of the prevalence of secularism in the academy.

The French sociologist Émile Durkheim and the Durkheimian school had a profound impact on the development of archaeological approaches to religion from the late nineteenth century onwards.Footnote 73 The notion of the sacred and the profane as a means of distinguishing religious material, central to Durkheim’s The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912),Footnote 74 has been immensely influential; Durkheim’s definition of religion and his means of categorizing what is religious had lasting appeal.Footnote 75 He posited that religion was inherently a social process; what was not social, was not religious, but rather ‘folklore’.Footnote 76 Religion, when viewed in this way, was inseparable from other social phenomena.Footnote 77

Julian Droogan recently examined the intermingling of such ideas with Marxist conceptions of religion and society, which were dominant in scholarship in the later twentieth century. The combination of viewing religion as society, and the denial of religion as being more than a product of economic and material conditions (in Marxist terms), ultimately made the study of religion a secondary aim for archaeologists.Footnote 78 Little of what developed in the archaeological interpretation of religion in the early twentieth century was theorized until the 1980s.Footnote 79 The importance of the definition, however, is evident from the lack of classical archaeological works that attempt to deal with deeper problems of religion beyond cataloguing material.

There has been a reluctance on the part of archaeologists to see religion as part of their remit. The attitude is typified by Christopher Hawkes’ ‘Ladder of Inference’.Footnote 80 Hawkes claimed that the four steps ranging from the easiest to the hardest to infer from archaeological phenomena are: the techniques used to create them; the subsistence-economics that was built on them; the social and political institutions that built them; and, finally, to infer religious institutions and spiritual life from them. Hawkes was not wrong to argue that understanding religion from archaeology alone is hard, but was he right to close the door on such an aim?Footnote 81

Over the last thirty years there has been a surge of interest in developing archaeological techniques for challenging just the sort of argument that the likes of Hawkes had put forward, in the hope of finding a place for archaeological investigations in the study of religion. Hawkes’ point, as he made clear, is that religion and spiritual life cannot be approached ‘unaided’ or in other words, without a textual history. The great challenge to this proposition, in terms of archaeological studies, has been focused on landscape and on ritual, in particular within the burgeoning field of cognitive archaeology. In the last thirty years there have been dozens of conferences, edited volumes and monographs produced on this topic within Classical archaeological circles, all responding to this new intellectual movement.Footnote 82

In the alignment of material culture with the study of ancient religion, Simon Price’s influential book of 1984, Rituals and Power, and Colin Renfrew’s 1985, The Archaeology of Cult were both landmark publications, heavily reliant on archaeological findings and their interpretation. Both also drew extensively on the work of the anthropologist Clifford Geertz.Footnote 83 Relativism, so important for anthropologists keen to allay fears of cultural bias, allowed particular evidence to be viewed as culturally specific. Sociological approaches that had once suppressed religious meanings in material culture could now be utilized to think about religion. Material evidence could provide indications about the religious habits of ancient communities, and such approaches were also a means of avoiding the baggage of contemporary, Eurocentric schemes of what constituted religion. In the decades since, numerous Classical archaeologists have taken the study of ritual to heart.Footnote 84

Yet little attention has been paid to defining the relationship of ritual to religion and vice versa. The contribution to understanding of religion made by studies of ritual thus remains founded upon uncertain principles. Without clarity on this, ritual-centred approaches cannot hope to play more than a marginal role in responding to the larger question of what we mean by the term ‘religion’.Footnote 85 For example, the LIMC’s successor, the Thesaurus cultus et rituum antiquorum (ThesCRA), as a multi-volume condensation of contemporary academic opinion on images and religion, has been damningly summarized: ‘Notwithstanding the great usefulness of such a compendium, it is frankly a monumental testimony to a series of presumptions and presuppositions grounded in no argument or analytic justification whatsoever.’Footnote 86 It lacks any discussion of either the category of ‘ritual’ or that of ‘religion’, nor of the equation of these two terms throughout. This is a signal instance of the optimistic inclusion of evidence and subjects of inquiry without a fundamental appraisal of the problems they bring.

Ritual is something that might be observed, as for example in scenes of processions in Roman art, or inferred from the nature, context or comparability of a particular object to others, as in the case of the Maryport altars (both their dedications and potentially their burials). But in what sense is the ritual that they suggest religion? Clearly, there was some religious substance in the regular dedication of altars by members of the same military company; but the mid-twentieth-century theory (entirely unsupported by evidence) that the Maryport altars were buried in an annual ritual represents a good example of ungrounded optimism in inferring ritual and religion from archaeology. This assumption has recently been rejected in favour of pragmatic interpretations of the burials as enabling building foundations. In Durkheimian terms, ‘secular’ rituals, like going to work every morning at the same time, do not necessarily occupy ‘sacred’ as opposed to ‘profane’ space.Footnote 87 Might works of art or objects of material culture operate differently if viewed as either ritual items or religious items? And how might we relate studies of ritual to comparable studies of religion? These are more troubling questions than perhaps they should be, throwing into light the gap between ambition and practice in archaeology.

3. Conclusions

At present, the study of Roman religion through material culture is caught between the currents of the three broad disciplinary approaches we have been discussing: historical, art historical and archaeological. We have demonstrated in each sub-section how the interpretation and use of the Maryport altars could be affected by these often-competing lines: historians have valued the inscriptions over the objects; art historians have not engaged with them at all; archaeologists have seen them mainly in terms of their collectivity and what their burials may entail. The challenge is partly located in the difficulties of communicating across disciplinary boundaries. The trouble is that, whether striving against or working within subject boundaries, one encounters the deeply ingrained problems that prevent effective cross-disciplinary communication and comparison. While there is no desire to keep these approaches distinct from one another, there remain no sustained precedents for a comparative dialogue.

Ideological biases of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries have denied the significance of material evidence in relation to religion, denied the religiosity of aesthetically judged objects, and denied the significance of an object or image’s religious aspects in relation to other social structures. In part, at least in relation to questions in the study of religion, this is connected to the fact that the ancient ‘polytheistic’ religions of antiquity are an outlier in the bigger narrative of the world religions, including the main thrust of this volume. Unlike the world religions – and indeed unlike some universalizing religions that ultimately never ‘made it’, such as Manichaeism – the religions of Graeco-Roman antiquity, with the exception of Judaism and Christianity, were not founded on written scriptures. Since academic method in studying religion is profoundly dependent on starting from scripture (itself a process embedded in centuries of theology in Europe and Asia), the lack of scripture has always complicated the study of ancient religion. This is why the study of ancient religion has largely lain in the purview of the ancient historian and to an extent, the archaeologist, rather than in the hands of theologians. With recognition of material culture’s central place in ancient religion, the focus has rightly shifted and specialists working on this material have increasingly participated in discussions of religion.Footnote 88

The result has been a certain discomfort about how to marshal an evidential base for ancient religion and indeed the problem of what constitutes appropriate empirical evidence at all. Religion only became an interesting aspect of the study of material culture when it was acknowledged that images and objects could play more than one significant role even for the same person, and that different viewers saw the same thing differently. But as soon as response to objects, rather than the meaning of objects became the object of study, the evidence that material culture could provide in relation to religion ran into direct conflict with constructions of religion that have traditionally sought the kinds of firm categories constructed through scripture and its commentarial exegeses.

This chapter has shown that we need a discourse that allows us to talk across our various forms of evidence, without unduly stressing one evidentiary base or methodological framework. It is worth asking whether it is possible to write a religious history entirely from material and artistic evidence. For many, it will be very difficult to grasp how such a thing could be done. How will we know what was meant, who was who, what things were for? These are reasonable doubts; but only insofar as we cling to the traditional types of history, and history of religions, that are written from texts. To reverse the question, can we write an adequate religious history without material and artistic evidence? For the ancient world, the answer must be no. In part, this is because the Greeks and Romans never conceived of their religious life in the kind of textual terms defined by scriptures: how can we know how they visualized their gods, how they framed them in space, what their procedures for worship were, without the evidence of material culture?

Our ability to incorporate material evidence into our pictures of the past is dependent upon a continued interrogation of the methods we use. The particularity of material evidence remains problematic. The idiosyncrasy of many objects and images, not to mention contexts, makes it extremely difficult to talk across time and space in the way we do when discussing economics or political power. But, in transforming object-specific studies to broader histories, we should expect to challenge our preconceptions not only of what religion was, but of how we write about religion and construct history more generally. The very introduction of material evidence into our picture of religion, long excluded by a dominant textual tradition, is part of the way we may break this cycle. But in doing so, we have to be aware that many of the ways that we do history or think about religion must necessarily be questioned as a result.

Objects like the Maryport altars offer a valuable example of methodologies and questions rooted in material culture. What they might tell us is not necessarily confined to one aspect of religion: as well as religious practice, we might think of religious identity, of belief, of the sacrality of the altars themselves and the extent to which they are religion. Their materiality and the dimension of time, the fact of their continued existence in a changing world, makes it almost impossible for them to have maintained the same nature and degree of significance amongst the people who used them from the day of their creation to the time when they were buried. The altars may not be able to reveal all that we wish to know about them, but to have such expectations is to miss the point: no single piece of evidence can ever provide the full and final answer. Few things ever come with a maker’s mark and complete biography attached. The key is to ask questions of them and to use them to help answer questions.Footnote 89 It is these doubts and possibilities, this type of reflection, which needs to be built into materially engaged histories of religion in the future.

We have recently seen a greater willingness from scholars to talk about religion beyond what have traditionally been conceived of as the boundaries of the disciplines of art history and archaeology, and similarly a desire to use material evidence by historians. Concerted efforts have been made to respond not just to the call for increased use of visual material as an intrinsic part of the evidence for Roman religion, but to face the challenges that this presents. These have come from all sides of the disciplinary divides and are frequently configured as inter-disciplinary approaches.Footnote 90 It is to this kind of model that we must look, in order to challenge the common perceptions of how to study Roman religion, be that through a historical, art historical or an archaeological perspective.