11.1 Introduction

Indonesia’s first attempt at fossil fuel subsidy reform following the 1997 Asian financial crisis exacerbated the already dire economic crisis for people across the country. The dramatic increase in fuel prices ignited protests and violent riots, representing the breaking point in public patience for the Suharto regime’s rampant corruption and poor governance; the weeks of unrest following the reforms contributed to Suharto’s resignation in 1998. Numerous fuel subsidy reforms were attempted in Indonesia in the following decades but with varying degrees of success. Indonesia makes an excellent case study for analysis because it is illustrative of the challenges involved in subsidy reform in developing countries – including corruption, vested interests, democratisation and domestic energy consumption dependent on fossil fuels.

Indonesia is often referenced in the fossil fuel subsidies literature as a case of successful reform. However, these reforms have been going on for 15 years, and subsidies are still offered. This chapter asks whether the Indonesia case provides an example of successful subsidy reform by analysing three periods of reform: (1) the aftermath of the Asian financial crisis under Presidents Suharto, Megawati and Wahid (1997–2003), (2) the introduction of social assistance programmes under President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, also known as SBY (2004–13) and (3) the most recent reforms under President Joko Widodo, also known as Jokowi (2014–15). The success of these reforms will be examined through several angles: the durability of the reforms, the economic effectiveness in reducing the amount of government expenditures to fossil fuel subsidies and the ability of the reforms to increase state revenue and improve the overall distribution of socio-economic benefits.

This case study of Indonesia examines how domestic political actors influence the outcomes of macroeconomic factors in determining the relative success of fuel subsidy reforms. This chapter observes how ideas and norms surrounding fuel subsidy reform have changed over the three periods of analysis. Using qualitative analysis, and adopting a political economy approach, this chapter looks at the factors of external crisis, political leadership and strong communication campaigns and social assistance and evaluates them across three periods of reforms using process tracing (Checkel Reference Checkel2006; Collier Reference Collier2011). Data were collected from primary and secondary documents, field research and semi-structured interviews.Footnote 1

11.2 Drivers of Successful Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform

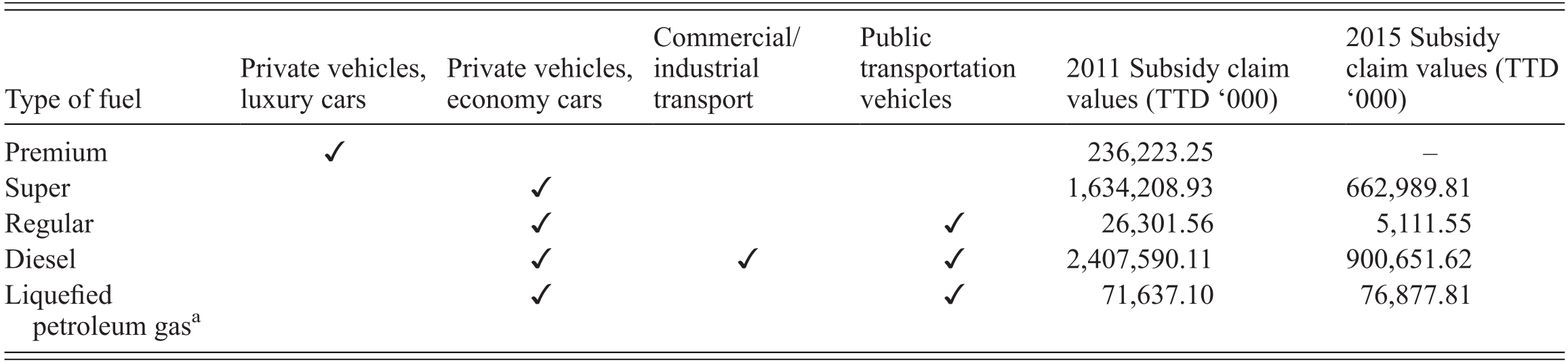

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), Indonesia allocated approximately 64 trillion Indonesian rupiah (IDR) (USD 5 billion) in its 2016 budget, compared to IDR 240 trillion (USD 19.3 billion) in 2014 (IEA 2016). The IEA estimates that only 5 per cent of the poorest third of Indonesian households benefit from this budget or consume subsidised fuel; by contrast, 70 per cent of the wealthiest top third of households consume subsidised fuels.

In their joint report for the Group of 20 (G20) on the phase-out of fossil fuel subsidies, the IEA, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the World Bank define an energy subsidy as ‘any government action that lowers the cost of energy production, raises the revenues of energy producers, or lowers the price paid by energy consumers’ (IEA et al. 2009: 5). This chapter will use this definition and hence only focus on policies that have an impact on fossil fuel prices (see also Chapter 2). Fossil fuel subsidies can be further broken down into production and consumption subsidies; this chapter focuses on the latter because it is the most politically significant kind of subsidy in Indonesia. In Indonesia, fossil fuel subsidies encourage energy consumption with cheap energy prices, distort energy markets, provide an opportunity for fuel smuggling and produce macroeconomic instability exacerbated by volatility in the currency exchange rates and global oil market (World Bank 2009; HSKIP 2013: 78–79; Bridle and Kitson Reference Bridle and Kitson2014; GSI 2014). Indonesia allocated subsidies to electricity and a range of fuels, including liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), kerosene, automotive diesel and gasoline.

It is important to distinguish between what qualifies as political reform and what drives successful reform. Hill (Reference Hill2013: 109) defines ‘successful reform’ as ‘durable and significant policy change that improves aggregate socioeconomic welfare, consistent also with an objective function that recognises distributional and environmental considerations’. ‘Durable’ implies that reforms are socially and politically acceptable or are not overturned by major political backlash.

The political economy literature has outlined several drivers of the degree of success of political reform or the decision to undertake such reform (see also Chapters 1 and 3). Macroeconomic factors such as economic crises and other kinds of crises provide the need and urgency to initiate required reforms that may be unpopular in stable economic times (Drazen and Grilli Reference Drazen and Grilli1993; Aswicahyono et al. Reference Aswicahyono, Bird and Hill2009; Hill Reference Hill2013). The role of public support for reforms – e.g. from community groups, industry associations and students – is important in determining the durability of political reforms (Basri and Hill Reference Basri and Hill2004). Agency in the shape of political leadership, informed by technical advisors, is important for building support for reforms, leading communication campaigns or persuading and incentivising diverging political interests to reach consensus (Hill Reference Hill2013; Wenzelburger and Horisch Reference Wenzelburger and Horisch2016). Political commitment to reform helps to mobilise action and enhances credibility and transparency for the changes (Garcia Villarreal Reference García Villarreal2010). Strategic communication campaigns that explain reforms and the policies for reducing negative impacts are an important element of successful reform, providing knowledge to ensure that the economic logic of the reforms is better understood by those most affected (Indriyanto et al. Reference Indriyanto, Lontah, Pusakantara, Siahaan and Vis-Dunbar2013; Pradiptyo et al. Reference Pradiptyo, Wirotomo, Adisasmita and Permana2015). This chapter aims to illuminate the political and economic factors that contributed to successful reform of fossil fuel subsidies in Indonesia.

The trouble with fossil fuel subsidy reform in Indonesia is that subsidies were originally implemented for poverty reduction purposes, yet they did not reach their targeted population. The World Bank found that for 2012, nearly 40 per cent of fuel subsidies went to the richest 10 per cent of households and less than 1 per cent went to the poorest 10 per cent, which makes fuel subsidies essentially ‘generous transfers of taxpayer money to the rich’ (Diop Reference Diop2014: 4). Indonesia’s fuel subsidies mainly covered transportation fuels, which largely benefited middle- to upper-class households that can afford vehicles (HKSIP 2013). Yet indirect impacts of fuel subsidy reforms negatively affected poor populations, since the increase in fuel prices created headline inflation, raising the overall cost of consumer goods and subsequent cost of living; this affects all consumers but hits the poor populations the hardest (Guillaume et al. Reference Guillaume, Zytek and Farzin2011; Beaton et al. Reference Beaton, Gerasimchuk and Laan2013; ADB 2015; Casier and Beaton Reference Casier and Beaton2015). Therefore, social assistance programmes were seen as a way to provide a cushion to the most vulnerable households against the indirect impacts of reforms. This is an important point in the case of Indonesia because it differs from other countries, where the populations directly affected by reforms receive compensation such as tax breaks or assistance through direct deposits into specific household or business bank accounts, as in the cases of India (see Chapter 12) and Iran (Guillaume et al. Reference Guillaume, Zytek and Farzin2011).

11.3 Political Economy of Fossil Fuel Subsidies in Indonesia

For the purpose of this chapter, fuel subsidy reform will be operationalised as the change in fuel prices to improve fiscal balances. However, the complete reform of these fossil fuel subsidies that are fixed below market prices requires the removal of price controls so that domestic fuel prices reflect global oil prices. A successful reform involves the achievement of socio-economic benefits as well as distributional considerations (Hill Reference Hill2013). Success is defined by the ability of the government to raise energy prices without overwhelming public protest, and to achieve economic objectives such as reducing government expenditures on subsidies and/or improving aggregate socio-economic welfare and development. In the case of Indonesia, this involves the reduction of budgetary deficits (Aldy Reference Aldy, Greenstone, Harris, Li, Looney and Patashnik2013), the redistribution of the budget to economic development and a buffer for poor populations affected by the negative externalities of fossil fuel subsidy reform (i.e. inflation and the rise in costs of consumer goods). While this buffer helps influence the social acceptability of reforms, it is arguably intertwined with what makes a reform durable. This section explores the case-study background and political economy of fuel subsidy reform in Indonesia.

11.3.1 Fossil Fuel Subsidies in Indonesia

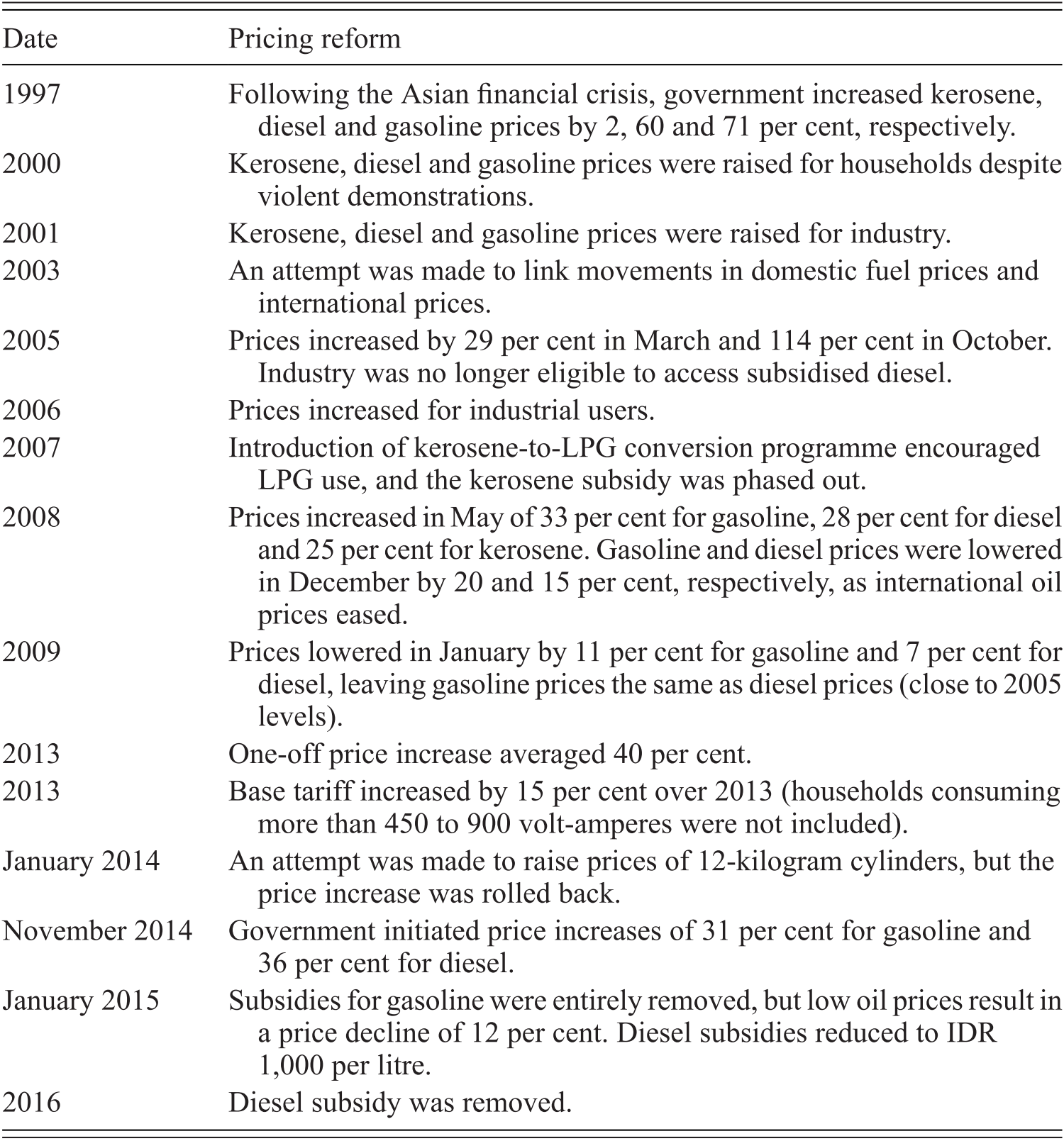

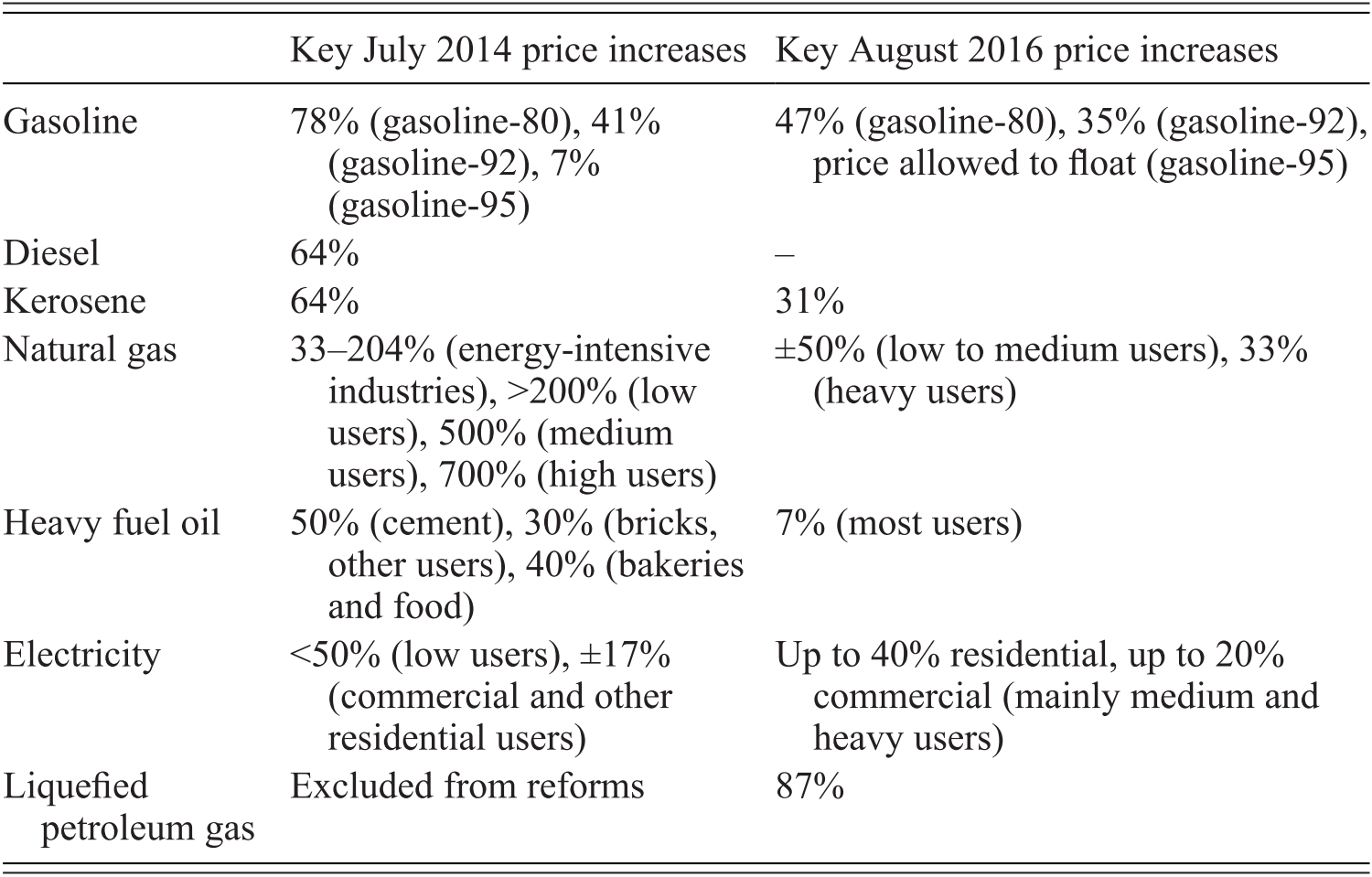

Fossil fuel subsidies have had a major impact on Indonesia’s energy policy, development and overall economic health – but not in the way the government intended. Following the 1973 oil crisis, Indonesia benefited from rising global oil prices and domestic production. As Indonesia became a member of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and a major producer in the mid-1960s, the government began subsidising fossil fuels for domestic consumption to alleviate poverty, to reduce the impacts of inflation and as a basic public service obligation underlined in the Constitution (GOI 1945). Oil exports fuelled an economic boom throughout the 1980s and 1990s, but mismanagement, overproduction and corruption led to long-lasting negative impacts. One of the most significant impacts is Indonesia’s transition from a net oil exporter to net importer in 2004 due to decades of mismanagement and lack of investment in the oil sector; this change meant the government began subsidising imported fuels, a policy that quickly became economically unsustainable when combined with dramatic increases in domestic energy demands. Subsidies consumed up to 24 per cent of government expenditure and contributed to ongoing energy crises caused by insufficient supply, growing demand and much-needed infrastructure investment (HKSIP 2013). These challenges put pressure on the Indonesian government to prioritise energy diversification, reduce subsidies and raise fuel prices. Table 11.1 provides an overview of the history of fossil fuel subsidy reforms in Indonesia from 1997 to 2016.

Table 11.1 Timeline of fossil fuel subsidy reforms in Indonesia

| Date | Pricing reform |

|---|---|

| 1997 | Following the Asian financial crisis, government increased kerosene, diesel and gasoline prices by 2, 60 and 71 per cent, respectively. |

| 2000 | Kerosene, diesel and gasoline prices were raised for households despite violent demonstrations. |

| 2001 | Kerosene, diesel and gasoline prices were raised for industry. |

| 2003 | An attempt was made to link movements in domestic fuel prices and international prices. |

| 2005 | Prices increased by 29 per cent in March and 114 per cent in October. Industry was no longer eligible to access subsidised diesel. |

| 2006 | Prices increased for industrial users. |

| 2007 | Introduction of kerosene-to-LPG conversion programme encouraged LPG use, and the kerosene subsidy was phased out. |

| 2008 | Prices increased in May of 33 per cent for gasoline, 28 per cent for diesel and 25 per cent for kerosene. Gasoline and diesel prices were lowered in December by 20 and 15 per cent, respectively, as international oil prices eased. |

| 2009 | Prices lowered in January by 11 per cent for gasoline and 7 per cent for diesel, leaving gasoline prices the same as diesel prices (close to 2005 levels). |

| 2013 | One-off price increase averaged 40 per cent. |

| 2013 | Base tariff increased by 15 per cent over 2013 (households consuming more than 450 to 900 volt-amperes were not included). |

| January 2014 | An attempt was made to raise prices of 12-kilogram cylinders, but the price increase was rolled back. |

| November 2014 | Government initiated price increases of 31 per cent for gasoline and 36 per cent for diesel. |

| January 2015 | Subsidies for gasoline were entirely removed, but low oil prices result in a price decline of 12 per cent. Diesel subsidies reduced to IDR 1,000 per litre. |

| 2016 | Diesel subsidy was removed. |

11.3.2 Political Economy of Fuel Subsidy Reform and Actor Constellations

Indonesia’s political economy and governance capacity – to implement reforms, address corruption and clientelism and achieve economic development – provide the foundation that underlies the history of fuel subsidy reform in the country. The politics of fossil fuel subsidy reform are intertwined with Indonesia’s history of oil production, whereby the government redistributed wealth earned from oil revenues through subsidies to reduce poverty (IEA 2016). The public acceptability of the reforms is therefore interlinked with the belief that the public is entitled to a redistribution of wealth from the production of national resources, national patrimony through subsidies or government compensation for increasing fuel and commodity prices through other forms of social assistance (Lockwood Reference Lockwood2015). Throughout the periods examined in this chapter, the government of Indonesia’s provision of either subsidies or social assistance as a complement to fuel subsidy reform is used to increase political support for the government rather than provide development and poverty alleviation.

The political economy of fossil fuel subsidy reforms provides insights into the various special interest groups that benefit from fuel subsidies and may challenge or create obstacles to subsidy reform. One of the sizeable interest groups in the Indonesian middle class that has an interest in maintaining subsidised fuel increases is owners of motorbikes or scooters (referred to as ojeks in Bahasa). There are an estimated 76 million scooters in Indonesia, which is approximately one scooter for every three people (Schlogl and Sumner Reference Schlogl and Sumner2014). Indonesia is strongly reliant on private transportation, and the government has systemically promoted motorbike ownership through substantial subsidies for transportation fuels, underinvestment in public transportation or rail systems and ‘public-sector hostility to non-motorized modes of transportation’ (Hook and Repogle Reference Hook and Replogle1996: 80). The motorbike owners who benefit from subsidised fuels have vested interests in maintaining subsidies and have actively opposed and protested fuel price hikes, although their opposition has been manipulated by political parties to protest subsidy reform.

Vested interests in industries that benefit most from subsidised fuels – such as the state-owned oil company Pertamina, the Indonesian oil-trading lobby, vehicle manufacturers and distributors and freight and public transport – remain opposed or ambivalent towards reforms and have lobbied intensively against them (IEA 2016). Pertamina’s interest in maintaining the fuel subsidies relates to the company’s inability to compete effectively in the downstream market due to insufficient investment in the company’s refining capacity, as well as a reliance on the certainty of continued subsidies. According to the IEA (2016: 72), Pertamina’s management has indicated that liberalisation of the fuels market would probably need to be accompanied by some protection for the company. In other words, according to Pertamina management, a clear timeframe for reform would have to be accompanied by greater public investment in upgrading Pertamina’s refining capacity. Other vested interests include vehicle manufacturers – who are closely engaged with the Ministry of Industry – that have an interest in maintaining the supply and demand for vehicles, which run on low-octane fuels, such as the subsidised RON88 fuels (IEA 2016). Transitioning out subsidised low-octane fuels would require an upgrade of vehicles to run on non-subsidised fuels.

Indonesia’s history of oil production and fossil fuel subsidies has created the country’s ‘oil and gas mafia’, known for its corruption, including embezzlement of funds from the Ministry of Energy, extortion, tax fraud and smuggling (Cassin Reference Cassin2014; Sukoyo Reference Sukoyo2014). One of the issues is the black market created by subsidised fuels – cheap, subsidised oil is smuggled and sold at below-market prices for a profit – to businesses or consumers who are not eligible for the subsidy or need more than their quota. Fuel smuggling contributes to distorted fuel prices and is a frequent negative externality of fossil fuel subsidies (Sdralevich et al. Reference Sdralevich, Sab, Zouhar and Albertin2014).

These vested interests and overarching macroeconomic factors have affected decisions taken on the reform of fossil fuel subsidies. The next sections delve into the historical perspective of the aftermath of the Asian financial crisis in 1997, when the first attempt to reform subsidies was implemented. They then examine SBY’s reforms and the introduction of social assistance, as well as more recent reforms under President Jokowi. Socio-economic and macroeconomic factors play an important role in the durability of these reforms.

11.4 Policy Tools for Navigating Macroeconomic Factors

11.4.1 Managing the Asian Financial Crisis

In the six months following the Asian financial crisis between July 1997 and January 1998, the rupiah collapsed from 2,500 against the USD to nearly 10,000, dramatically increasing prices and halting imports (Pisani Reference Pisani2014: 47). To abate the financial crisis, President Suharto committed to a 50-point agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to qualify for an emergency loan (Beaton and Lontoh Reference Beaton and Lontoh2010; IMF 2013). Some of the points included dismantling state and private monopolies and cutting subsidies of basic commodities, including fossil fuels. While the IMF package envisioned a gradual phase-out of subsidies between 1998 and 1999, the government dramatically raised prices on kerosene (25 per cent), diesel (60 per cent) and gasoline (71 per cent) in May 1998, prior to the first IMF loan disbursement meeting (Beaton and Lontoh Reference Beaton and Lontoh2010). The government pursued severe austerity and dramatic increases in fuel prices, creating inflation, without adequate buffers for the public or vulnerable populations, demonstrating the urgency in reducing government expenditures.

The result was disastrous. Student groups in cities across Indonesia went to the streets in protest of rising prices, which they deemed as resulting from corruption. The subsidy reform and fuel price increases were the tipping point in discontent with the rampant corruption under Suharto’s regime. For three months, protestors demanded the resignation of Suharto and eventually occupied Parliament. Suharto resigned and handed power to his vice president, B.J. Habibie, in May 1998 (Mydans Reference Mydans1998). The new government had a steep agenda, as the economy was in a state of freefall with high inflation, food shortages, bankruptcies and economic paralysis due to the rupiah’s dramatic depreciation. Nearly all subsequent attempts to reform subsidies by Presidents Wahid and Sukarnoputri (Megawati) between 2000 and 2003 resulted in violent demonstrations as students and the public felt that the price increases were linked to powerful interest groups (Bacon and Kojima Reference Bacon and Kojima2006; Beaton and Lontoh Reference Beaton and Lontoh2010). The government promised to use budget savings to help low-income households, but in reality, subsidies for rice and education were low in this period, and many compensation programmes did not materialise (Bacon and Kojima Reference Bacon and Kojima2006; Beaton and Lontoh Reference Beaton and Lontoh2010).

During this period, the external shock of the Asian financial crisis and the conditionality attached to the IMF stabilisation loan were the major factors driving the adoption of fossil fuel subsidy reform. However, despite the fact that the economic crisis was important in creating the urgency for reforms, it was unsuccessful in shifting fuel subsidy reform to ‘low politics’; the problems with corruption of the government surrounding this period were too severe for reforms to be disassociated from the dissatisfaction with the political system. The legacy of corruption and lack of governance capacity had left the public in outrage. Nevertheless, the fossil fuel subsidies became a symbol of oil wealth redistribution, particularly in the absence of adequate policies to reinvest oil welfare in infrastructure development or social welfare programmes. Subsidy reform therefore represented to the public further failures of the government and its ongoing corruption. Lastly, there was an absence of social assistance or political leadership adequately explaining reforms during this period, which further demonstrated the poor implementation of reforms and lack of governance capacity.

11.4.2 Yudhoyono and the Beginning of Social Welfare Politics

As Indonesia grappled with the damage of the Asian financial crisis, the second period (2004–13) marked the beginning of a shift in Indonesian energy policy, whereby the need to reform subsidies overrode the lack of political favourability for reform. In this period, the Indonesian government began initiating a social welfare system to compensate poor populations for the indirect economic burden of subsidy reforms. These programmes were important in shifting popular opinion in favour of subsidy reform, which helped make substantial price changes possible.

In 2004, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono was elected as the Indonesian president in the same year that Indonesia shifted from a net oil exporter to a net oil importer. The government’s subsidies on imported fuels had a disastrous impact on the budget and energy security; it exposed the government budget to major fluctuations in prices on the international market, to tariff barriers and to potential geopolitical vulnerabilities with security of supply. Spending on fossil fuel subsidies for gasoline, diesel and kerosene rose to USD 8 billion (out of total government expenditures of USD 374 billion; Beaton and Lontoh Reference Beaton and Lontoh2010: 8; World Bank 2017a). The SBY government was forced to remove fuel subsidies to alleviate the budget deficit (Interview 1). Fuel prices were increased in March by 29 per cent and then in October 2005 by 114 per cent, which reduced the deficit by USD 4.5 billion and then USD 10 billion, respectively (Beaton and Lontoh Reference Beaton and Lontoh2010).Footnote 2 This reform was politically possible – without major backlash from the public – arguably because of the introduction of social assistance programmes. These types of programmes not only provide a buffer for the resulting economic shocks from fuel prices increases, but they also provide credibility for the government’s commitment to social welfare (Perdana Reference Perdana2014).

The provision of social assistance also illustrates the government of Indonesia’s prioritisation of poverty alleviation and its shift towards a welfare state. In the early 2000s, in the post-Suharto era, the government became increasingly accountable to the public, and candidates in local and national elections promised ambitious social welfare assistance for education, poverty reduction and healthcare (Aspinall Reference Aspinall2013: 114). Social assistance became a salient issue in politics. SBY’s tremendous public support can be attributed to heavy investment in social programmes, which improved his poll figures (Mietzner Reference Mietzner2009). To overcome the political challenges of subsidy reform and to alleviate the burden of price increases on the poor, SBY’s administration started to provide cash-transfer and compensation programmes, including clean cookstove dispersals for kerosene-to-LPG conversion, and it increased spending on health, education and social welfare (Budya and Arofat Reference Budya and Arofat2011; World Bank 2013).

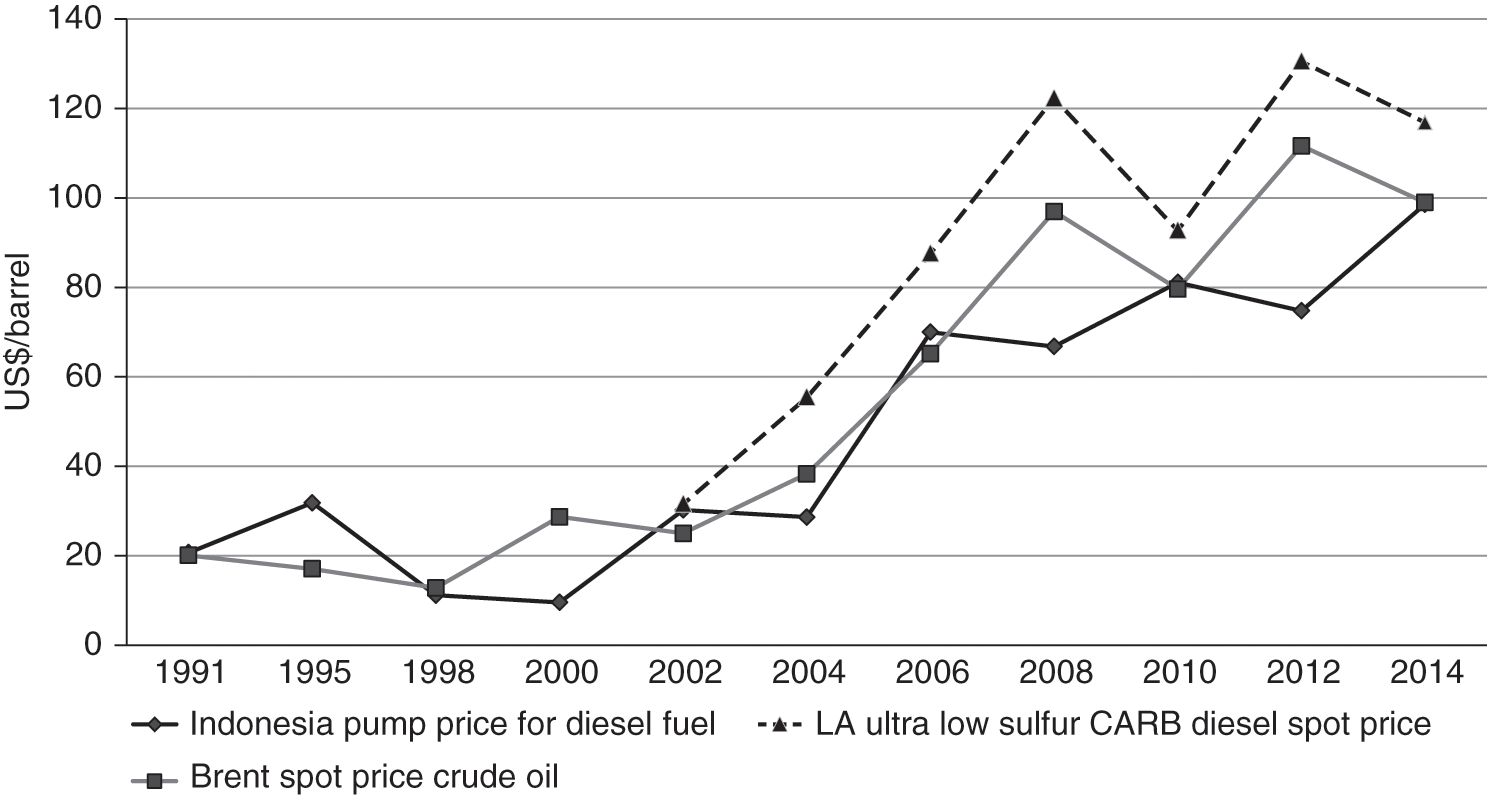

While this period showed the positive impacts of social welfare in shifting the political support for subsidy reform, increasing global oil prices also limited the fiscal impacts of fuel subsidy reforms. For example, in 2008 and 2011, when oil prices breached USD 100 per barrel, the fiscal burden of energy subsidies rose as well. In response to high oil prices, Indonesia attempted to initiate energy subsidy reforms and raise prices. In May 2008, the Indonesian government raised prices of diesel and kerosene and then lowered prices of diesel by 12 per cent, when international oil prices decreased (Beaton and Lontoh Reference Beaton and Lontoh2010; IMF 2013; ADB 2015). Although an unconditional cash transfer, a ‘rice for the poor’ programme and a loan-interest subsidy for small enterprises were dispersed through social assistance programmes, the fluctuations in oil prices were too volatile and affected prices at the pump; the subsidy reform was repealed (Figure 11.1).

These reforms illustrated the importance of political leadership with strong communication campaigns and social assistance programmes as a buffer against the indirect effects of fuel subsidy reform. However, the government had not incorporated a buffer to reduce the overall impacts of international oil price fluctuations on the population, meaning the continued cycle of fossil fuel subsidy reforms, price shocks and public unrest necessitated social assistance programmes or the repeal of subsidies. To fully remove subsidies and price controls, better implementation of subsidy reform coupled with buffers and the reinvestment of the subsidies budget in development was still needed.

11.4.3 Oil Market Fluctuations and Widodo’s Subsidy Reform Policy

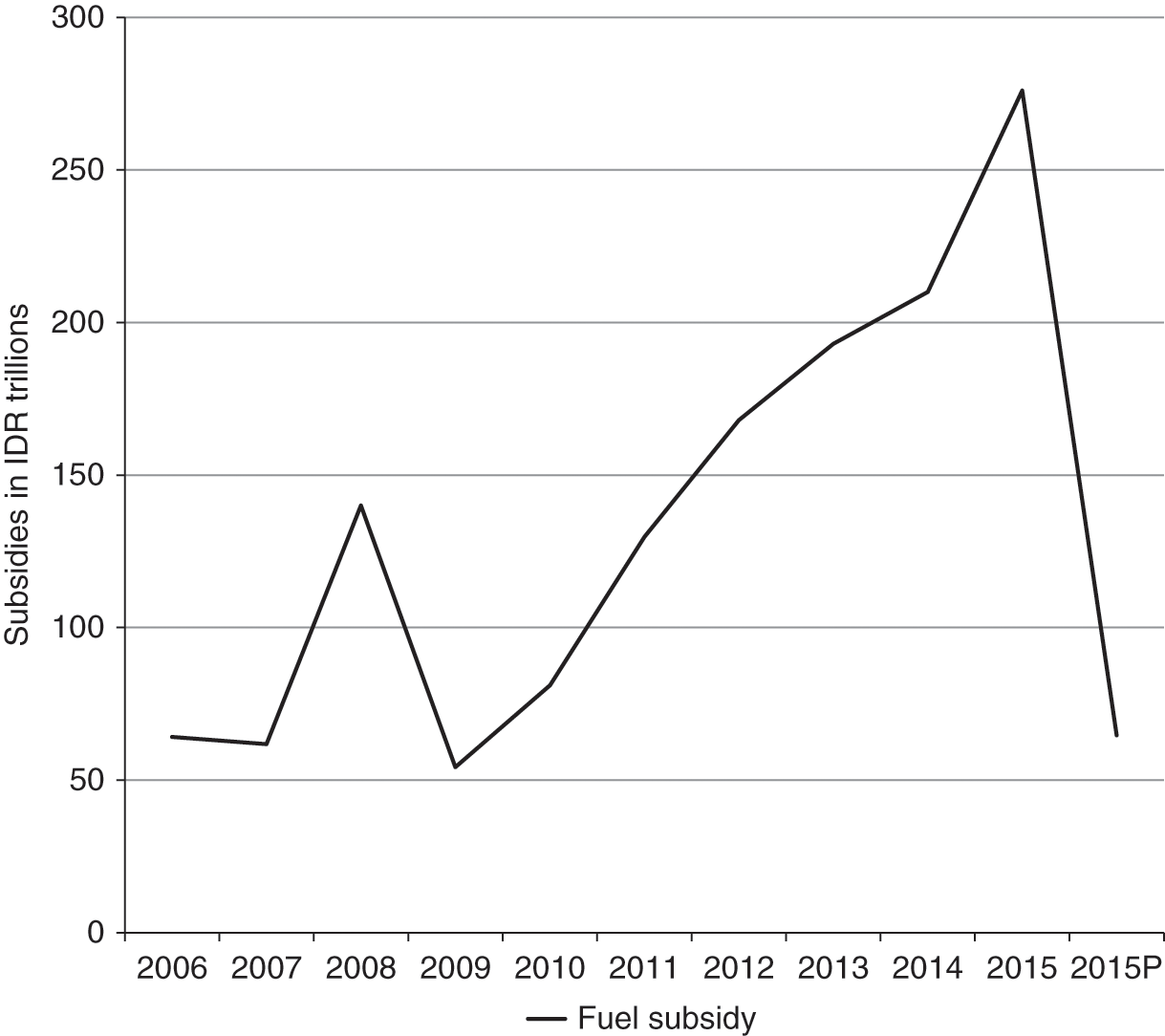

Energy subsidies on imported fuels leave fiscal policy vulnerable to fluctuations in global oil prices as well as currency exchange markets. A weakening of the rupiah means a higher price of energy products on the domestic market and subsequently a higher share of subsidies if domestic prices are not adjusted (Diop Reference Diop2014: 2). This was evident in the 2008 financial crisis, when the Indonesian rupiah lost 28 per cent of its value against the dollar between October and November 2008 (Basri and Rahardja Reference Basri, Rahardja, Ito and Parulian2011). Figures 11.1 and 11.2 show the response of the Indonesian government to volatility in the oil market through subsidisation.

Figure 11.2 Fuel subsidies in Indonesia (2006–15)

The Jokowi administration implemented its last series of reforms in 2014, under the rhetoric of the need to reallocate public finances towards infrastructure investment; the aim was to let domestic fuel prices follow the global oil market and to remove price controls (Interviews 2 and 3). In the lead-up to the implementation, the Ministry of Energy created the Oil and Gas Task Force to reform the oil and gas sector and reduce corruption, particularly within Pertamina. Faisal Basri was appointed as the head of the Task Force, and the technocratic team was made up of 11 members, including ministers, academics, bureaucrats and activists (Sipahutar Reference Sipahutar2014; Interview 4). The Task Force made the following recommendations for reforms in the oil and gas sector: the dissolution of Petral (Pertamina’s oil trading arm), the creation of the integrated supply chain unit within Pertamina to take over procurement of crude oil and petroleum products from Petral, a gradual fossil fuel subsidy phase-out with a social welfare programme, the creation of a buffer to better manage price fluctuations and more efficiency from upstream petroleum regulator SKK Migas (Cahyafitri Reference Cahyfitri2015; Interview 4). Fossil fuel subsidy reform would also be the most effective way to deal with the oil smuggling if domestic fuel prices matched international prices, as this would remove the incentive to smuggle fuels. Many of the recommendations of the Task Force were put in place, including the removal of gasoline subsidies from the budget (which de facto transferred the budget to pay off debts to Pertamina), the dissolution of Petral, increases in gasoline and diesel prices and other changes to address corruption in the oil and gas sector.

The major opposition to subsidy reform during this period was launched by Prabowo Subianto – Jokowi’s competitor in the 2014 elections and the son-in-law of Suharto (Kapoor Reference Kapoor2014). His ‘Red-White coalition’ opposes fuel subsidy reforms with a misleading argument that reforms are unnecessary in light of low oil market prices and the assertion that reforms will increase poverty (Wikipdr 2014). However, their opposition is likely linked to corruption and vested interests from the old so-called corruption, collusion and nepotism regime (commonly known as the ‘KKN’ regime) under Suharto (The Economist 2014).

The plans to fully reform fossil fuel subsidies in Indonesia preceded the crash of the global oil market in 2015. Scholars argued this was the best moment to implement the reforms because price shocks would be low (Benes et al. Reference Benes, Cheon, Urpelainen and Yang2015). The price for oil dropped to USD 30 per barrel in August 2015 but then rebounded to USD 49 per barrel in October 2016; in parallel, gas price fell from USD 400 to USD 318 per metric ton in June 2016, opening up the window for LPG subsidies reform (Lontoh and Toft Reference Lontoh and Toft2016). Furthermore, in 2015, the Indonesian rupiah depreciated to levels not seen since the Asian financial crisis, but then the currency rebounded in 2016 to IDR 13,271 against the USD from IDR 14,000/USD 1 (Nangoy and Suroyo Reference Nangoy and Suroyo2015; Lontoh and Toft Reference Lontoh and Toft2016).

The macroeconomic fluctuations have not led to dramatic changes in the subsidies policy in the budget, but there are changes in who bears the cost of subsidy policy and the transparency of the policy. Since the removal of subsidies was already signed into law in 2015, the 2016 budget did not include a budget line for gasoline subsidies, but it kept subsidies for 3-kilogram LPG tanks, diesel and new and renewable energy; a fixed diesel subsidy of IDR 1,000 per litre had a dramatic change in managing diesel subsidies (APBN 2016; Interviews 2 and 5). Between January and March 2015, the government implemented a series of prices changes, mainly decreasing domestic consumer prices in line with lower market prices. However, when international market prices increased, a price gap was created. The financial burden of the subsidies’ price gap was transferred to Pertamina, covering the difference from the production costs and market price of oil, which amounted to USD 1 billion (IDR 15 trillion; Otto Reference Otto2015; Samboh and Cahyafitri Reference Samboh and Cahyafitri2015; Witular Reference Witular2015). This was not a formal policy but rather seen as a response to the transitional period while the government continued to apply the three-month price adjustments (Interview 6). The government informally compensated Pertamina by keeping pump prices the same when global oil prices fell to account for price gaps and Pertamina’s deficit (Interview 6). While the long-term plan to peg the domestic pump prices to international prices will ameliorate this issue, there is still a great deal of policy support needed to make this transition. Stronger fiscal policy combined with investment in infrastructure and directed social assistance is still needed to successfully remove price controls and ensure the permanent reform of fossil fuel subsidies in Indonesia.

11.5 Drivers of Successful Reform of Indonesia’s Fossil Fuel Subsidies

From Suharto to SBY to Jokowi, the evolution of fossil fuel subsidy reform policies across the three periods of analysis help determine the factors contributing to the success and durability of reforms. The relevant drivers of successful fuel subsidy reforms in the case of Indonesia were agents actively promoting or opposing fossil fuel subsidy reform, as well as strategies comprising the provision of social assistance, political leadership and the framing of such reform. Macroeconomic factors, more precisely external crises, were also important influences in the success of fossil fuel subsidy reforms. The analysis that follows will discuss each factor in turn.

The largest factor influencing reforms in the case of Indonesia has been macroeconomic factors creating economic crises in Indonesia. Volatility in the oil market and currency exchange rates – as well as other external economic shocks – have had an enormous impact in driving fuel subsidy reforms in Indonesia. Macroeconomic factors included the Asian financial crisis, the shift of Indonesia from a net exporter of oil to a net importer in 2004, the 2008 global recession and increase in global oil prices and the depreciation of the rupiah in 2014. These external shocks have created economic crises and massive budget deficits in Indonesia because of subsidies on (especially imported) fuels. The shocks have driven the government of Indonesia to implement significant fuel subsidy reforms, even when they were extremely unpopular. While external shocks have played a large role in driving reforms, they also mitigate the effectiveness of reforms in general. Until the price controls are removed, fiscal policy will remain vulnerable to volatility in the oil and currency markets, creating pressure for increasing or reintroducing subsidies.

The provision of social assistance as a buffer to poor populations against the negative consequences of fuel subsidy reform is the most important factor in the success of reforms and can be considered a necessary condition. Social assistance became increasingly salient in political campaigns and has influenced the expectations of the public towards the provision of public goods by the government. While developmental states typically have a centralised policy of wealth redistribution and poverty alleviation, Indonesia’s fossil fuel subsidies can be viewed as an informal policy of ‘rent’ redistribution in exchange for political support (Khan Reference Khan, Khan and Jomo2000; Lockwood Reference Lockwood2015). The introduction of social welfare effectively reduced public protest to reforms by addressing the needs of the poor populations most impacted by the negative externalities of increased fuel prices. While social assistance provided a buffer against the impacts of the rise in fuel prices on the poorest populations in the short term, a long-term development strategy is needed to maintain macroeconomic stability.

Political leadership and strategic communication campaigns that increase the public’s knowledge of subsidy reforms are also necessary conditions for durable reforms. The political capital of SBY grew tremendously in 2006 and 2009 after the generous provisions of social assistance to compensate for fuel price increases. Likewise, Jokowi’s political leadership and agency in shifting the discourse of subsidy reforms to generate support and political backing was quite successful overall. In terms of economic effectiveness, some of the subsidy reforms have been more successful than others in relieving budgetary crises over deficits, which is mainly determined by the currency exchange rates and the prices of the oil market. The social acceptability and durability of the 2005–7 and 2013–15 reforms, combined with the alleviation of budgetary crises, make these two series of reforms the most successful. Many of the implemented reforms that were eventually retracted were still successful in temporarily relieving budgetary pressure by reducing government expenditures.

Overall, the leadership of reforms that combined social assistance and strategic communications lent legitimacy to the Indonesian government and generated support for the historically politically unpopular reforms. The last period of reforms under Jokowi demonstrated the success in shifting norms and ideas that previously depicted fuel subsidy reform as government corruption and inequitable wealth redistribution; such reforms are now seen as credible and necessary for fostering economic development through a focus on investment in infrastructure as a road to growth. Moving forward, there is still a need to further depoliticise fuel subsidy reforms and how fuel prices are set, which will require institutional reform in the government ministries that currently handle subsidy reforms.

11.6 Conclusion

Using a qualitative case-study analysis of fossil fuel subsidy reforms in Indonesia between the Asian financial crisis and recent reforms in 2015, this chapter investigated the factors that made successful, durable reform of fossil fuel subsidies possible. The major factors investigated were external shocks or economic crises, political leadership for reform, communication campaigns and social assistance. The analysis found that macroeconomic fluctuations leading to economic crises overwhelmingly drove reforms, but strong political leadership, strategic communication and social assistance were the most critical factors in facilitating durable reform in Indonesia – representing decisive political and economic policy choices. Two series of fuel subsidy reforms in Indonesia, first between 2005 and 2007 and then again between 2013 and 2015, were the most successful reforms because they achieved both social acceptability and economic objectives of alleviating government expenditures on fuel subsidies.

Indonesia’s history of fuel subsidy reforms offers insight into the tensions between political leadership for fuel subsidy reforms and vested interests in maintaining the status quo. The case study demonstrates that the domestic political drivers of successful and durable fuel subsidy reform determine the ultimate influence of macroeconomic factors such as financial crises and oil market volatility. The success of particular fuel subsidy reforms, particularly during periods of economic crisis, were influenced by the Indonesian government’s strong leadership in fostering support and lending credibility to politically unpopular energy price increases. The success in political leadership can be attributed in large part to the provision of social assistance and strategic communication of these programmes to the public.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the Swiss Network for International Studies, INOGOV, Graduate Institute Centre for International Environmental Studies, Swiss National Science Foundation and Harvard Kennedy School, which helped make this research possible. The author would also like to thank Henry Lee, Joe Aldy, Liliana Andonova and anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

12.1 Introduction

Consumer energy subsidies in developing countries are used in lieu of social security nets, aimed at shielding poor consumers from price shocks (Grubb et al. Reference Grubb, Hourcade and Neuhoff2014). However, energy subsidies are fiscally burdensome, crowd out social spending, disproportionately benefit richer people, distort energy markets and engender higher greenhouse gas emissions (Savatic Reference Savatic2016). Yet, reforming fossil fuel subsidies has been politically as well as administratively challenging. Several developing countries have made unsuccessful attempts at energy price reforms, sometimes with politically disastrous consequences (Salehi-Isfahani et al. Reference Salehi-Isfahani, Stucki and Deutschmann2015).

In view of the rising subsidy burden, the Indian government has undertaken a series of fossil fuel subsidy reforms over the last few years. For instance, the government successfully deregulated gasoline and diesel prices in June 2010 and October 2014, respectively (Ganguly and Das Reference Ganguly and Das2016). In 2012, to contain the subsidies for liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), the predominant ‘clean’ cooking fuel in India, the government restricted the subsidy benefit to six LPG cylinders (14.2 kilograms each) per household, which was subsequently raised to 12 due to political pressure (Nag Reference Nag2014).Footnote 1 Prior to 2012, there was no limit on the amount of subsidised LPG that a household could consume.

Reforming cooking fuel subsidies is particularly challenging due to opposition from poor households, as energy costs form a significant share of their expenditure budgets, even though they benefit disproportionately less than wealthier households (Savatic Reference Savatic2016). In 2013, the government of India introduced the Direct Benefit Transfer Scheme for LPG (DBTL scheme), a conditional cash-transfer scheme.

While cash transfers are a popular means of social assistance in developing countries, few countries have used them in the context of energy subsidies reform. In 2005 and 2014, the government of Indonesia implemented an unconditional but targeted cash-transfer programme to compensate poor families against fuel price rise (Savatic Reference Savatic2016; see Chapter 6). Iran implemented a uniform cash-transfer scheme in tandem with an energy price hike in 2010 to cushion its poor population and make the reform politically feasible (Salehi-Isfahani et al. Reference Salehi-Isfahani, Stucki and Deutschmann2015).

In the context of the global discourse on fossil fuel subsidy reform, the DBTL scheme is an interesting reform to look into for various reasons. First, unlike the conventional reforms for reducing the fossil fuel subsidy, the DBTL scheme focuses on improving the efficiency of the subsidy delivery mechanism to decrease the leakage of the subsidised commodity to unintended users and uses. Second, the DBTL scheme provides a platform for the government to selectively target the subsidy to specific groups of beneficiaries, instead of providing it universally (as was the case before it was introduced). Third, the sheer scale of the DBTL scheme, which covered about 139 million households in October 2015Footnote 2 – making it the largest benefit-transfer scheme in the world (MoPNG 2015e) – calls for its assessment, particularly because no comprehensive analysis currently exists.

This chapter presents the results of a performance evaluation of the DBTL scheme. It seeks to draw lessons from the overall experience of the scheme, focusing on the following three key questions: (1) How successful was the implementation process of the scheme, and what were the gaps in implementation, if any? (2) How successful was the scheme in achieving its stated objectives? (3) Why did the DBTL scheme achieve this degree of success? In answering these questions, we specifically focus on the key actors and stakeholder groups involved or affected by the scheme and on the strategies employed by each to design and administer the scheme as well as to overcome the challenges encountered during the scheme’s implementation.

The chapter begins with an overview of challenges associated with the LPG subsidy programme in India and the DBTL scheme. It then discusses the methodology adopted for the evaluation. Next, we discuss the results, focusing on efficacy of the implementation process, success of the DBTL scheme in achieving its stated objectives and the factors that made DBTL scheme implementation a success. We conclude with key lessons for fossil fuel subsidy reform processes for other countries while highlighting the next steps for DBTL scheme reform.

12.2 The LPG Subsidy and the DBTL Scheme in India

Several issues afflicting the LPG subsidy programme in India have been highlighted in the literature. These include (1) a rising subsidy burden, (2) a skewed distribution of the LPG subsidy (and of consumption) among urban versus rural areas and across income classes, (3) the diversion/leakage of subsidised LPG for unintended purposes,Footnote 3 (4) ownership of multiple connections by several households and (5) fake or ‘ghost’ connectionsFootnote 4 (Morris and Pandey Reference Morris and Pandey2006; Lang and Wooders Reference Lang and Wooders2012; Soni et al. Reference Soni, Chaterjee and Bandhopadhyay2012; MoPNG 2013; Clarke et al. 2014; Clarke and Sharma Reference Clarke and Sharma2014; Docherty Reference Docherty2014; Jain et al. Reference Jain, Agrawal and Ganesan2014). To address some of the challenges, these studies have proposed diverse reforms ranging from reducing the subsidy amount and imposing a realistic cap on a subsidised commodity (for each household) to implementing a direct cash transfer and targeting the beneficiaries.

To curb the diversion of subsidised LPG for unintended purposes and to ensure that the households received their subsidies, the government of India introduced the DBTL scheme. The scheme aimed to reduce leakages by achieving a common market price for LPG and by channelling the consumption-linked subsidy directly to the bank accounts of LPG consumers (MoPNG 2013). Under the scheme, households buy LPG at the market price (instead of the subsidised price) and receive the subsidy directly into their bank accounts (following the purchase, for a maximum of 12 cylinders of 14.2 kilograms each per household per year).

This scheme was first launched on 1 June 2013 and subsequently expanded to 291 districts in six phases covering 17 million people (Nag Reference Nag2014). The scheme was successful in curbing the leakages in the LPG distribution system, but it also suffered from numerous consumer grievances due to the speed at which it was rolled out and the requirement that a consumer should have an Aadhaar numberFootnote 5 to receive the subsidy (MoPNG 2014). In view of such issues, the DBTL scheme was suspended in early 2014, and an expert committee was established to review it.

Incorporating the recommendations of the committee, a modified DBTL scheme, also known as PaHaL (Pratyaksha Hastaantarit Laabh), was relaunched in 54 districts in November 2014 and expanded to the rest of the country in January 2015 (MoPNG 2015b). The modified scheme was launched with the following stated objectives (MoPNG 2015b): (1) protecting entitlement and ensuring that the subsidy reaches the consumer, (2) removing incentives for diversion, (3) weeding out fake/duplicate connections and (4) improving the availability/delivery of LPG cylinders for genuine users.

12.3 Methodology and Data Collection

To answer the research questions, we followed a mixed-methods approach that systematically integrates quantitative and qualitative research methods (Bamberger Reference Bamberger2013). Although the DBTL scheme is a pan-India scheme, we focused on three states, namely Gujarat, Haryana and Kerala, to get an in-depth picture of on-the-ground realities. We chose these states to capture diversity on three main criteria: (1) the proportion of households with an LPG connection, (2) the share of LPG consumers enrolled in the DBTL scheme and (3) the proportion of rural households in the state. The selected states also represent three different geographies (south, west and north). Most of the states in the eastern part of the country exhibit a low penetration of LPG and, due to limited resources, could not be included in the study.

For our assessment, we focused on all the key stakeholders involved in the scheme’s implementation, including

1. The Director (LPG) at the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas (MoPNG) responsible for coordination and implementation of the entire scheme,

2. National sales heads of each of the three oil marketing companies (OMCs),

3. Field officers of OMCs supervising LPG distributors at district level,

4. Lead district managers (LDMs) of lead banks at district level responsible for coordination and implementation of the scheme from the banks’ end, and

We conducted unstructured in-person interviews of the first two stakeholders and semi-structured telephone interviews of field officers (nine) and LDMs (three). We focused our interview with the Director LPG on national-level challenges that the scheme’s implementation encountered and how the ministry tried to overcome them. We also discussed the details of the implementation strategy that the government followed. Finally, we discussed the roles and responsibilities of the various actors involved, as well as the coordination efforts undertaken between different actors and institutions. In our interviews with national sales heads of OMCs, we focused on operational issues, support and directives received from the ministry, as well as their perspective on findings from consumer and distributor surveys, to add further nuance and context to the findings and validate them. For LPG distributors, we conducted a structured telephone survey of 92 randomly selected distributors to ensure that our findings were representative. The interviews and survey were focused on understanding stakeholders’ perceptions of the adequacy of the support received from other stakeholders, difficulties faced and measures taken to overcome these difficulties during the scheme’s implementation. We used stakeholder perceptions along with the extent of consumer enrolment in the scheme as measures to assess the efficacy of the implementation process.

To assess the scheme’s success in meeting its stated objectives, we conducted a telephone survey of 1,270 randomly selected LPG consumers, proportionate to the market share of the three OMCs in each state. The survey focused on consumer awareness about the scheme’s objectives, ease of enrolment and perceived impact of the scheme on service delivery. Further, since distributors were responsible for enrolling the consumers in the DBTL scheme and directly engaged with them, we also enquired about their perception of the scheme’s impact on customers, diversion of subsidised LPG and fake connections. To validate the results obtained from the survey and stakeholder interviews, and to derive lessons learned from the scheme’s implementation, we supplemented our findings with an analysis of official data (on LPG sales) and secondary data sources, such as government press releases. All the engagements were conducted in May 2015 (see Jain et al. Reference Jain, Agrawal and Ganesan2016 for a detailed methodology).

12.4 Efficacy of the Implementation Process

12.4.1 Status of Consumer Enrolment in the Scheme

Results from the distributor survey indicated an enrolment rate of about 85 per cent, with the highest rate reported in Kerala (87 per cent), followed by Gujarat (85 per cent) and Haryana (81 per cent). The findings correspond well with official data reported by the MoPNG, validating the representativeness of the survey.

However, in the consumer survey, a higher proportion of households (94.6 per cent) reported being enrolled in DBTL. The higher reporting could be partly attributed to those households who had submitted their application and perceived themselves as being enrolled, even though the enrolment process was not yet completed for them. This is reflective of the scheme’s ongoing process but also highlights the lack of information of consumers regarding their state of enrolment.

Households that reported as not being enrolled in the DBTL scheme (5.6 per cent) stated that lack of interest in the subsidy and lack of awareness about the enrolment process were major reasons. Further, rejection of documents by the banks and lack of a bank account were other reasons. Non-enrolment due to a lack of interest indicates the scheme’s potential in weeding out households that do not need the subsidy, a positive externality. This provides an important lesson that instead of providing a subsidy as a default, the government should ask for enrolment to receive subsidy benefits, which can help weed out non-deserving populations to some extent.

Though very few respondents cited the absence of bank accounts as a reason for non-enrolment, it highlights the fact that households without bank accounts could be left out of the scheme and, hence, miss out on the subsidy benefits. The important lesson here is to keep the scheme design inclusive when drafting such reform.

12.4.2 Stakeholder Experiences during the Implementation Process

12.4.2.1 LPG Consumers

We found that a majority (73 per cent) of the enrolled households reported the enrolment process to be ‘easy’; only 2.5 per cent found the process to be ‘difficult’. This indicates that the process was largely smooth. This could be attributed to the constant improvement in the process by the OMCs and innovative approaches adopted by the distributors, among other reasons. For instance, we found out during the field officers’ interviews that distributors in some urban areas of Haryana delivered and collected enrolment forms at the doorsteps of the households through their deliverymen. This indicates the importance of designing the schemes to minimise consumer effort for enrolment, resulting in a positive perception of the process and rapid enrolment.

As per the government procedures for DBTL scheme enrolment, households had to make either two visits (for Aadhaar-based allocation of funds or seeding) or just one visit (for bank seeding). However, we found that 45 per cent of the households made three or more visits to the banks and distributors combined, indicating inefficiency in the implementation process. Despite a certain inefficiency in the process, the majority of customers did not find the enrolment process difficult. Admirably, less than 1 per cent of the households enrolled reported instances of corruption at the hands of distributors or bank officials, indicating a highly transparent process.Footnote 6

12.4.2.2 LPG Distributors

Given the strict timelines for the scheme’s implementation, 88 per cent of the surveyed distributors reported facing one or more challenges during implementation (Figure 12.1). We further found that 75 per cent of distributors reported that the Aadhaar-based seeding process was easier than the bank seeding process. Under the former, distributors have to enter only the Aadhaar number, whereas under the latter, they are required to enter several data fields related to bank account details, which is relatively tedious and error prone. This highlights the importance of simple and easy procedures for ensuring hassle-free programme implementation.

Figure 12.1 Challenges for distributors during the DBTL scheme rollout in India.

Document verification or form submission at banks was reported as the major challenge under both categories. Banks often delayed the verification process and rejected high volumes of applications due to spelling mismatches. This suggests the importance of considering the procedural details and the resulting challenges in order to put contingencies and flexibilities in places. In this case, to meet the scheme’s timeline, the MoPNG directed OMCs and distributors to enrol customers through direct bank seeding, skipping the banks’ verification process in the short run, and later conducted the verification retrospectively.Footnote 7 Although this significantly increased the rate of enrolment, it also led to wrong entries of bank details by the distributors and thus affected the effectiveness of the subsidy-transfer process.

The absence of bank accounts for customers also posed difficulties to the distributors. It put the onus of guiding the customers (about opening new accounts) on the distributors, who had strict timelines to achieve the enrolment targets. Furthermore, about 36 per cent distributors did not find banks to be cooperative in handling and solving the customer complaints. At the national level, the Department of Financial Services (under the Ministry of Finance) was in alignment with the MoPNG to make the DBTL scheme a success and issued two sets of guidelines for banks to prepare themselves for DBTL scheme enrolment. However, it was found that banks were not entirely prepared for effective implementation of the scheme.

Due to delays or non-receipt of the subsidy in bank accounts, distributors had to tackle customers’ subsidy-related queries without sufficient information or capacity. Subsidy-related queries were specifically cited as a major challenge by 22 per cent of the surveyed distributors (see Figure 12.1). This shows the importance of an active communication system not only between implementing agencies but also with the customers to establish trust and empower the implementers.

While distributors reported various difficulties, the majority (87 per cent) acknowledged that the OMCs provided adequate support during the entire process. Based on our interviews with LPG leads, we found that OMCs supported the distributors in terms of both capacity building and financially (for the enrolment process). Field officers played a critical role in training and supervising the distributors.

12.4.2.3 Banking Personnel

Our interviews with LDMs revealed that banks were not well prepared for the scheme’s implementation, even though the Ministry of Finance’s Department of Financial Services issued notifications to the banks to facilitate adequate support. There was a lack of dedicated staffing in the banks for the DBTL scheme, with the responsibility bouncing from one employee to another; this often led to a waste of resources on repetitive capacity building. While the distributors received financial assistance from the OMCs on a per-enrolment basis, banks did not. Furthermore, banks lacked coordination between their headquarters and local branches. For instance, local bank personnel were not informed about the status of Aadhaar seeding when it was delayed at the central level, even though they were responsible for addressing customer enquiries.

The LDMs encountered several problems due to a lack of standardisation of the processes and protocols followed by different banks. For instance, banks were following different protocols to determine whether a joint account could be used for seeding with the LPG account (with or without Aadhaar). Such issues often created hassles for customers, distributors and LDMs.

LDMs also faced difficulties due to lapses in support from the distributors and gaps in information flows to the customers. On multiple occasions, LPG distributors shared LDMs’ contact details with the consumers for any subsidy-related queries. Consequently, LDMs were burdened by such queries, for which they were not responsible; they also did not have the capacity or information to deal with them. Interviews with senior officials at the OMCs and the MoPNG highlighted that the Ministry of Finance worked in close coordination with MoPNG and that towards the later stages, the coordination between banks, field officers and distributors improved significantly.

Overall, the DBTL scheme was well publicised and had fairly wide coverage, with efforts to increase enrolment rates by leveraging other ongoing schemes. While consumers found the scheme’s implementation largely smooth and transparent, distributors and bank personnel encountered several difficulties, particularly due to the short timeframe of implementation. However, its smooth rollout in the short four-month timeframe was facilitated by strong leadership by the OMCs and MoPNG, coordination between different stakeholders and constant improvements in the scheme during implementation.

12.5 Success of the Scheme in Achieving Its Stated Objectives

12.5.1 Effectiveness of Subsidy Disbursal to Consumers

Direct subsidy disbursal into the bank accounts of the beneficiaries was largely successful. Based on the consumer survey, 75 per cent of the households who purchased LPG cylinders after enrolling in the DBTL scheme reported receipt of subsidies in their bank accounts. The share was marginally lower in rural areas (73 per cent).

Notably, a significant proportion (16.6 per cent) of households was unaware of the status of their subsidy receipt, and a substantial share (8.6 per cent) reported non-receipt of subsidies for any cylinder purchased. We found that the issue was the lack of proactive information flows to consumers about their subsidy transfers, which was also confirmed by the findings from the distributor survey. Upon being asked about the main improvement area for the DBTL scheme, a quarter of the surveyed distributors highlighted the need to improve timely delivery of the subsidy as well as the information to consumers. Instances of non-receipt of subsidy were repeatedly cited as an issue by distributors, field officers and LDMs. However, all stakeholders mentioned that the rate of complaints significantly decreased over time.

12.5.2 Impact on Diversion of Cylinders

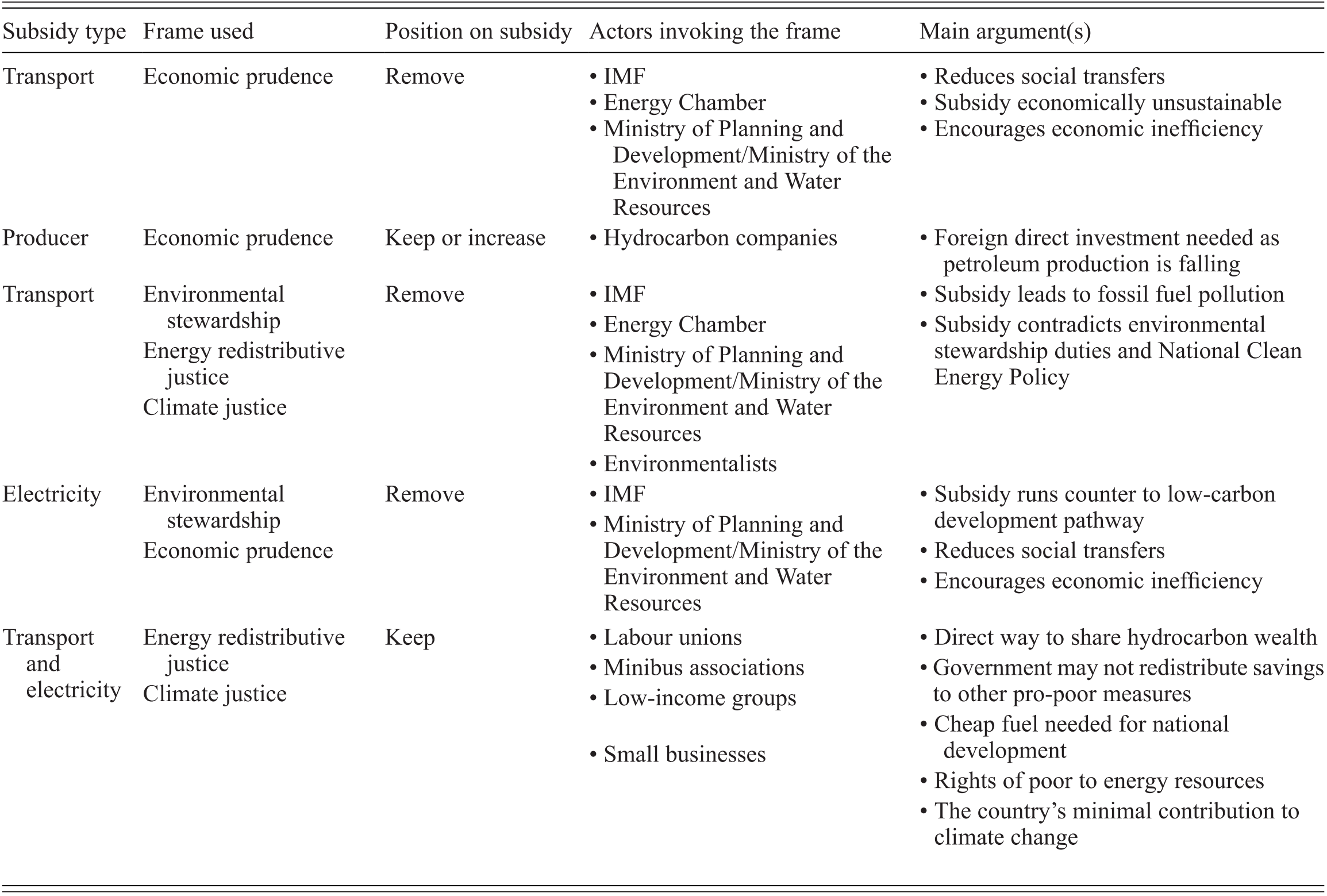

A majority (85 per cent) of the distributors reported that the scheme had a significant impact on reducing the diversion of cylinders. Our analysis of publicly available sales dataFootnote 8 of non-domestic LPG and auto-LPGFootnote 9 confirmed these findings.

The growth in the sales of non-household-packed LPG has been declining since 2009–10, with a negative growth rate in fiscal year (FY) 2013–14 and FY 2014–15. That began to turn around after November 2014, when the modified DBTL scheme was introduced. Since December 2014, the non-household-packed LPG sales have shown a significant positive growth rate, continuing for FY 2015–16, with an annual growth of 39.3 per cent (Figure 12.2). Such a marked increase in the growth of non-household-packed LPG can be attributed to the DBTL scheme’s impact in constraining the diversion of subsidised LPG from the distributors’ end; lower oil prices also had a partial impact by boosting demand.

Figure 12.2 DBTL scheme’s impact on growth of sales for non-domestic and auto-LPG in India.

Similarly, the LPG sales for transportation (auto-LPG), which have witnessed a declining growth rate since 2010–11, revived in January 2015 (concurrent to the nationwide launch of the modified DBTL scheme). For FY 2015–16, the overall growth in auto-LPG sales has been 4.3 per cent compared to a negative growth rate of 24.4 per cent in FY 2014–15 (Figure 12.2).

Even though the DBTL scheme has tried to facilitate a uniform market price of household LPG cylinders, there still is a difference between the market price for household and non-household LPG. The difference is due to the different tax structures applicable to household and non-household LPG and could still remain as an incentive to divert household LPG for non-domestic purposes. A reform in LPG taxation would be necessary to ensure entirely uniform pricing and further reduce the diversion of household LPG for unintended uses.

12.5.3 Impact on Eliminating Multiple and Fake Connections

LPG is a regulated commodity in India, and each household is allowed to have only one LPG connection. Duplicate connections, siphoning off subsidised commodities, have been a major challenge in LPG distribution. During the distributors’ survey, 84 per cent of the distributors reported that the scheme had a significant impact on controlling duplicate or multiple connections.

The government of India claims that the DBTL scheme has been able to eliminate close to 33 million ‘ghost’ (fake or duplicate) connections (MoPNG 2015f). All these ghost connections are basically inactive LPG connections (no refills done in the past six months). However, to estimate the extent of the scheme’s impact on controlling multiple connections, it is important to consider the number of inactive connections before the relaunch of the DBTL scheme (i.e. before November 2014).

An inactive connection also might not necessarily mean a ghost or duplicate/multiple connection. An unintentional impact of the DBTL scheme could be the conversion of some genuine LPG consumers into inactive connections, especially those from poorer economic backgrounds who have insufficient cash flows to buy LPG cylinders at the market price.

Under the scheme, the initial subsidy amount is transferred to the household’s bank account in advance to ensure that there is no additional outlay by the consumer while refilling a cylinder at the market price. However, in many rural areas, withdrawing money from the bank could mean losing out on half a day’s salary (as bank branches are far away). Consequently, some poorer LPG consumers might reduce LPG consumption, although our study did not test this hypothesis.

Thus, of the 33 million inactive connections, a significant proportion could be fake or duplicate. However, a more careful assessment is required to estimate the impact of the DBTL scheme in eliminating such connections while acknowledging the possible withdrawal of genuine households away from LPG due to reasons discussed earlier.

12.5.4 Impact on Availability and Delivery of LPG Cylinders

One of the four key objectives of the DBTL scheme was to improve the availability/delivery of LPG cylinders for genuine users. To assess this, we asked consumers about the change in delivery time of the cylinders in the previous two months. More than half the households reported that the timely delivery of cylinders had improved. Another 39 per cent of households reported no change in delivery time, whereas close to 9 per cent felt that the service had deteriorated. Interviews with senior officials at the OMCs suggest that the consumer perception of improved regularity in cylinder delivery could be attributed to the avoidance of collusions at the dealers’ and/or deliverymen’s end as a result of the DBTL scheme.

Overall, we found that the DBTL scheme was fairly successful in achieving its objective of direct transfer of subsidies to consumers, although some gaps remain. The scheme also succeeded in limiting the diversion of subsidised products and eliminating duplicate connections, although the extent of this needs to be carefully evaluated. Finally, the consumer perception of improved timely delivery of LPG cylinders following the scheme’s implementation could also be attributed to the DBTL scheme.

12.6 What Worked for the DBTL Scheme: Lessons Learned

This section discusses and highlights the key factors that led to the successful implementation of the DBTL scheme. It also elaborates on the lessons learned from the scheme’s implementation, which could be useful for designing fossil fuel subsidy reforms in other contexts and countries.

12.6.1 Political Leadership and Framing of the Narrative

We find that strong leadership from the national government was a prime factor behind the successful and smooth implementation of the world’s largest cash-transfer scheme, as it infused a momentum throughout the entire range of actors along the LPG supply chain involved in the implementation process. For instance, the scheme’s implementation was regularly reviewed by the Prime Minister (Prime Minister’s Office 2015) and monitored directly by the Minister of Petroleum and Natural Gas (MoPNG 2015d).

Unlike earlier initiatives for subsidy reforms, the DBTL scheme was implemented without any political backlash due to several factors. The dramatic fall in oil prices played a significant role in allaying public fears of any potential fallouts of the scheme. The government used this opportunity and framed the narrative on subsidy reforms as a measure to plug wasteful leakages and improve service delivery. Customer perception on this front was confirmed in our survey. The narrative was well timed, given popular sentiments against corruption (Sukhtankar and Vaishnav Reference Sukhtankar and Vaishnav2015).

For consumers, the scheme only changed the mode of subsidy disbursal and did not amount to subsidy withdrawal or reduction, which implied that only those accessing subsidies illegally were affected. These include local but unorganised commercial entities, which could not mobilise any opposition. While the LPG consumers who lacked access to banking services, mainly rural poor, might have been adversely affected, these cases were relatively few and diffused, given the low penetration of LPG in rural areas.

Thus, timely recognition of the opportunity for reform, smart framing of the narrative and direct monitoring by the political leadership at the national level were critical to the timely and successful implementation of the DBTL scheme.

12.6.2 Institutional Coordination

The scheme’s implementation involved multiple stakeholders, including several government ministries, the entire LPG retail supply chain, the banking sector and the district-level administration. Effective coordination across different institutions, with often different mandates, was essential for the scheme’s success.

For instance, regular meetings between the MoPNG and the Department of Financial Services were critical in ensuring overall alignment of banks in the scheme. The OMCs played a leading role in identifying and resolving bottlenecks by coordinating with all the relevant stakeholders throughout the scheme’s implementation. As one of the field officers interviewed suggested: ‘The entire implementation was under mission mode. From top to bottom, the momentum was buil[t] and leveraged, as everyone was pushing the roll-out collectively.’ An elaborate multi-tiered structure of project management teams was put in place to facilitate coordination and enable troubleshooting during implementation.

12.6.3 Exploiting Motivations at the Individual Level and Supporting Capacity Building

One of the interesting lessons from the DBTL scheme is that giving individual ownership and responsibility to stakeholders could be instrumental in the implementation of such large-scale public programmes. For instance, the senior and middle managers of the OMCs, along with the officials and Minister at the MoPNG, were the guardian officers for one district each (MoPNG 2015c). This created a sense of individual responsibility for effective implementation of the scheme in their respective districts. Further, the annual performance appraisal of the field officers of the OMCs was linked to the enrolment rate under the DBTL scheme.

Close to 16,000 LPG distributors across the country were mobilised, given individual targets and monitored on a daily basis for the scheme’s implementation. They also received periodic training and supervision from the field officers of the OMCs, along with adequate financial compensation to cover the costs incurred. Similarly, the bank personnel were trained by the LDMs, in coordination with the field officers. While an absence of dedicated bank personnel for the DBTL scheme led to delays and difficulties in the enrolment process, this was eventually overcome through continued efforts by MoPNG, Department of Financial Services, banks and LDMs.

The experience with the DBTL scheme provides an important lesson about effectively using different individual motivational drivers to facilitate effective and timely implementation of a government scheme.

12.6.4 Learning from Past Experience

As discussed in Section 12.2, the modified DBTL scheme incorporated insights from a review of the scheme’s first round of implementation. For instance, it included an alternative enrolment procedure, which addressed the politically sensitive issue of exclusion of LPG consumers lacking an Aadhaar number. Further, the review identified the difficulties faced by different stakeholders. This helped the OMCs to devise robust systems (such as improved information technology systems and software), along with teams of experts, to quickly respond to real-time on-the-ground enrolment issues. A comprehensive grievance-redressal system was also established in line with the recommendations of the committee to help resolve customer issues.

This shows the importance of reviewing reform programmes and incorporating the feedback of key stakeholders, particularly end consumers, to improve the scheme design and implementation processes.

12.6.5 Leveraging Existing Systems and Schemes

The DBTL scheme rested on the effective use of several other government schemes and efforts. Any digital cash-transfer scheme requires a branchless banking network and a robust authentication system (Banerjee Reference Banerjee2015). In the case of the DBTL scheme, the Core Banking SolutionFootnote 10 enabled electronic transfer of money to beneficiaries’ bank account, while the efforts towards the financial inclusion of the households ensured that most LPG consumers had or could open a new bank account to enrol in the DBTL scheme. In fact, about 14 per cent of enrolled households did not possess an existing account and had opened a new bank account to take advantage of the subsidy. About half of these accounts were opened under another national scheme for financial inclusion, Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana. This highlights the benefits of convergence and the need for greater coordination between different government schemes. Furthermore, the OMCs conducted a ‘know your customer’ drive before the DBTL scheme’s launch that created a digital database of beneficiaries (LPG consumers) and enabled the enrolment of customers under the DBTL scheme. The Aadhaar numbers, meanwhile, facilitated the online authentication of beneficiaries by linking their bank accounts to the core banking server (Banerjee Reference Banerjee2015).

While there was a clear convergence of past and ongoing schemes, sustained efforts must continue to improve the banking infrastructure and services for all households, particularly as rural and/or economically poor households will make up the majority of future LPG adopters in India.

12.6.6 Strong Emphasis on Awareness Generation

The DBTL scheme was well publicised through an intensive information education campaign. This comprised advertising through different media and direct outreach to consumers through the use of text messages, calls and public announcements (MoPNG 2014, 2015d). An information education campaign was devised and implemented for each district. The effectiveness of the awareness campaign was reflected in the consumer survey, in which all surveyed households knew about the DBTL scheme. However, there were gaps in awareness about the enrolment process and the status of subsidy transfer, which could be overcome through proactive information flows. The messaging in the awareness campaigns, which focused on ensuring households that they would retain their deserving subsidy benefit, also improved compliance with the scheme.

12.7 Conclusion

With increasing coverage and use of LPG as a domestic fuel in India, the need for reforming the LPG subsidy programme is growing. Apart from capping the consumption of a subsidised product, the Indian government implemented the DBTL scheme to improve the efficiency of subsidy disbursal and to reduce diversion of subsidised LPG to unintended users and uses.

This chapter assessed the performance of the DBTL scheme in terms of its implementation and the achievement of its objectives based on the experiences of key stakeholders. Using a mixed-methods approach, we found that the DBTL scheme fared well in both implementation and achievement of objectives. However, challenges remained pertaining to delays in the subsidy transfer, information gaps and a lack of financial inclusion. In summary, the DBTL scheme was successfully implemented due to strong political leadership at the national level combined with effective institutional coordination, strategies to motivate individuals, convergence of various government efforts, learning from past experiences and a focus on awareness generation.

By guaranteeing transfers directly to the beneficiary, the DBTL scheme made the reform of LPG subsidies and the liberalisation of LPG prices possible. It has paved the way for further reforms to improve the equity of the LPG subsidy programme by targeting the beneficiaries. The Indian government has already started excluding wealthy households on the basis of income information. Potential reforms, such as differential subsidies to different types of households – classified on the basis of income, socio-economic conditions, family size or urban-rural domicile – are now possible to further improve the targeting.

The largely positive experience of the DBTL scheme has inspired the government to use direct benefit transfer for other social benefits to improve the targeting and efficacy of government subsidy expenditures. However, the government should continue its efforts to ensure that no deserving consumer is deprived of the subsidy benefit due to a lack of information, difficulty during enrolment or poor access to banking services. Sustained efforts to bring such consumers within the scheme’s fold will be required, particularly as the penetration of LPG increases in rural areas, where access to banking services is a challenge.

The DBTL scheme is one of the few shining examples of fossil fuel subsidy reform achieving successful implementation on a massive scale without any significant public opposition. Strong political will and leadership, along with effective communication and messaging, coupled with a robust implementation plan and good management, led to the success of the DBTL scheme. Insights from this scheme could inform effective design and implementation of cash-transfer programmes in particular and fossil fuel subsidy reforms in general.

13.1 Introduction