There has been a long history of suicide discourse, and although there are discrepant reports on the first documented suicide (e.g., Ramses II, Lucretia, Periander, Empedocles), this phenomenon has been present worldwide for millennia. Writings touching on suicide can be found from cultures in ancient Greece and Rome, sub-Saharan Africa, China, Russia, Indigenous cultures in North, Central, and South America, and others (see Battin, Reference Battin2015 for a robust overview).

In some cultures, suicide is part of legend, with the memory of the deceased revered. For example, Cleopatra, queen of Egypt, died by suicide after her army’s defeat at Alexandria. Rather than be a trophy, she took her own life. The story of Lucretia, who died by suicide to protect her honor and speak out against Etruscan rule, is credited as the origins of the Roman Republic (Ruff, Reference Ruff1974). As a result, Lucretia was venerated for centuries and her story recounted in many pieces of art and literature (e.g., Canterbury Tales, Dante’s Inferno, Rembrandt’s Lucretia). Other ancient Romans and Greeks (e.g., Empedocles, Cato) endured similar fates, dying by suicide to achieve transformation or preserve their honor or legacy (Chitwood, Reference Chitwood1986; Drogula, Reference Drogula2019). It is in dying by suicide that these individuals cemented their names in history. Suicide after defeat in war as a means to preserve honor can be seen across time and geography. In Japan, seppuku (or hara-kiri) is a ritualistic suicide in which the samurai died by self-disembowelment to preserve their family’s honor. In these examples, the underlying philosophy is death before dishonor (Pierre, Reference Pierre2015).

The Stoics (e.g., Marcus Aurelius, Seneca, Epictetus, Cato, Musonius) taught that virtue is the only good, and if there was a potential to behave virtuously, then suicide is not rational (Englert, Reference Englert1990). However, they acknowledged circumstances under which it may be acceptable, honorable, or an expression of freedom (Falkowski, Reference Falkowski2016). While they argued that suicide based on life dissatisfaction was wrong, they acknowledged benefits of suicide as a means to avoid oppression, colonization, or subjugation. Seneca was unique in that he emphasized the freedom suicide offers in the absolution of fear, pain, and embarrassment. Some argued that dying for friends or country was acceptable, and Musonius argued that if suicide would benefit others more than would remaining alive, then suicide could be virtuous (Burton, Reference Burton2022).

Many religions, mostly monotheistic (Judaism, Christianity, Islam), condemn suicide (Barry, Reference Barry1995; Gearing & Alonzo, Reference Gearing and Alonzo2018). For Christians, particularly Catholics, views have shifted over time. Initially, martyrdom was viewed as a way to prove loyalty to God, but following the writings of St. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, the view transitioned to disapproval. For example, Thomas Aquinas makes several arguments against suicide, including that the commandment “Thou shalt not kill” includes oneself and life is a gift from God that must not be rejected. As such, the Church ultimately labeled suicide a mortal sin resulting in an eternity in hell (Torgler & Schaltegger, Reference Torgler and Schaltegger2012). In the Middle Ages, the Church would inflict further punishment: denying burial, punishing the corpses, or appropriating their estate, leaving survivors without resources (Torgler & Schaltegger, Reference Torgler and Schaltegger2012).

In the Enlightenment, the Church’s strict doctrine came under question. Writings from David Hume (Frey, Reference Frey1999) and others argued that some suicides can be viewed as moral and universal condemnation is unwarranted. Hume also highlighted the irony that the person experiencing misery has the God-given power to end his suffering, but do not for fear of offending God. This more secularist view argues that a person is their own master, free to kill themselves if they wish, and in some scenarios it is a positive, honorable, and emancipating endeavor (Beauchamp, Reference Beauchamp and Brody1989; d’Holbach, Reference d’Holbach1770; Hume, 1777).

Darwin’s (Reference Darwin1859) theories caused further debate as many grappled with reconciling religious, secular, and evolutionary perspectives, which influenced philosophers like Friedrich Nietzche. As a result, Nietzche’s writings emphasized the importance of finding value in life, regardless of the existence of Heaven. The focus on the present moment, the current life, is reinforced by his view that if value and meaning cannot be found in one’s current existence, then it must be created for oneself, rather than anticipating an afterlife. This also informs his view that death should be an experience and decision that falls under one’s own control, a voluntary death and respectable act (Nietzsche, Reference Nietzsche and Levy1964).

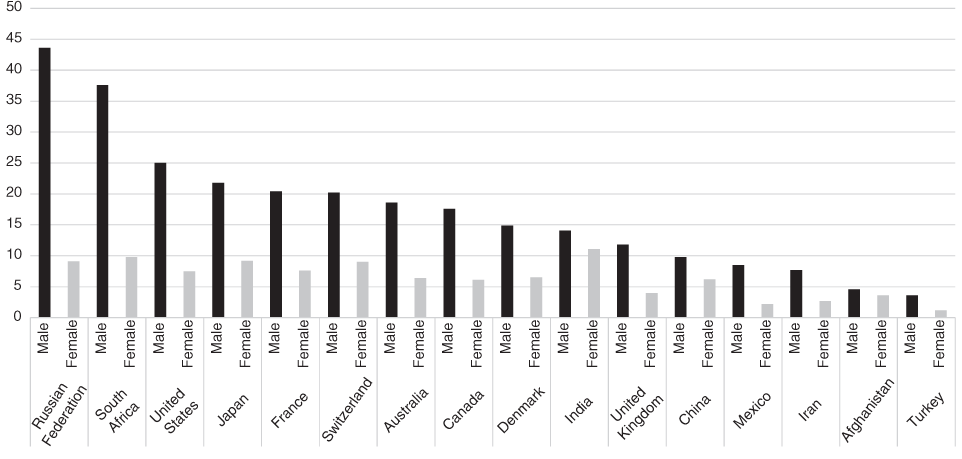

These views of suicide and its morality have evolved and pendulated over time, as informed by the zeitgeist. Currently, suicide is viewed as a significant public health issue worldwide (see Figure 1.1; Knox, Reference Knox2014; World Health Organization, 2014), with someone dying by suicide every 40 seconds (World Health Organization, 2019). Suicide contributes to premature mortality, morbidity, lost productivity, and healthcare costs (U.S. Office of the Surgeon General and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, 2012; World Health Organization, 2014), and has wide-ranging consequences for survivors and society as a whole (Barman & Kablinger, Reference Barman and Kablinger2021; Cerel, Reference Cerel2008; Jordan & McIntosh, Reference Jordan and McIntosh2010; McDaid et al., Reference McDaid, Bonin, Park, Hegerl, Arensman, Kopp and Gusmao2010; Ruskin et al., Reference Ruskin, Sakinofsky, Bagby, Dickens and Sousa2004). As a result, numerous organizations have set suicide prevention as a top priority (Carroll, Kearney, & Miller, Reference Carroll, Kearney and Miller2020; Stone et al., Reference Stone, Holland, Bartholow, Crosby, Davis and Wilkins2017).

Figure 1.1 2019 crude suicide rates by sex, all ages (per 100,000), for selected countries.

Suicide has traditionally been addressed with a focus on the individual and clinical interventions (Bryan & Rozek, Reference Bryan and Rudd2018; Isacsson et al., Reference Isacsson, Maris, Silverman and Canetto1997; Jobes, Au, & Siegelman, Reference Jobes, Au and Siegelman2015; Linehan et al., Reference Linehan, Korslund, Harned, Gallop, Lungu, Neacsiu and Murray-Gregory2015). However, many who die by suicide have not received mental healthcare in their last year (Miller & Druss, Reference Miller and Druss2001), limiting the impact clinical interventions can have. Further, suicide is the result of diverse biological, genetic, social, cultural, psychological, and behavioral factors that may not addressed by clinical interventions (De Leo, Reference De Leo2004; Qin et al., Reference Qin, Agerbo and Mortensen2003; Turecki et al., Reference Turecki, Brent, Gunnell, O’Connor, Oquendo, Pirkis and Stanley2019). As such, suicide prevention requires integrated approaches to address upstream risk factors and public health approaches to reduce risk in the whole population (Center for Mental Health Services & Office of the Surgeon General, 2001; Knox, Reference Knox2014; Knox et al., Reference Knox, Conwell and Caine2004; Lytle, Silenzio, & Caine, Reference Lytle, Silenzio and Caine2016).

Public health approaches incorporate clinical- and community-based interventions to address the health status and needs of a population in addition to focusing on at-risk individuals. These efforts focus on prevention strategies and the implementation of high-quality services at the population level (World Health Organization, 2012). The public health approach to suicide prevention includes: reducing stigma; increasing help-seeking; increasing lethal means safety; providing access to crisis lines and effective treatment; prevention strategies for the general population, at-risk groups, and individuals; community-based programs; and others (Knox et al., Reference Knox, Conwell and Caine2004; Lytle et al., Reference Lytle, Silenzio and Caine2016; Parcover et al., Reference Parcover, Mays and McCarthy2015; World Health Organization, 2012).

However, despite years of significant suicide prevention efforts, suicide rates in the United States have continued to rise (Hedegaard, Curtin, & Warner, Reference Hedegaard, Curtin and Warner2018; Perlis & Fihn, Reference Perlis and Fihn2020) until very recently (Curtin, Hedegaard, & Ahmad, Reference Curtin, Hedegaard and Ahmad2021). Increasing deaths of despair, including suicide, have contributed to greater mortality rates in the United States than sixteen other industrialized countries, a discrepancy that has been growing for two decades (National Academy of Sciences, 2021). Several hypotheses as to why these types of deaths are rising have been proposed and potential interventions suggested. Sterling and Platt (Reference Sterling and Platt2022) highlight how the sixteen countries with decreasing deaths of despair offer more support for their residents, such as through prenatal and maternal care, maternity leave, preschool provision, school equity, no or low tuition for universities, lower cost medical care, and significant vacation time. Given the range of potential interventions, it is unlikely that a single approach will reduce suicide rates (Lytle et al., Reference Lytle, Silenzio and Caine2016). Thus, our current understanding is that integrated efforts that blend cutting-edge clinical advances with community-based policies and resources will likely be more fruitful to destigmatize, address, and prevent suicide.