“A Cascade of Contradictory Orders”

Torch’s success had been eased by the surprise and magnitude of the Allied invasion that had sparked turmoil in the fragmented command structure of French North Africa (AFN), a confusion amplified by Darlan’s presence in Algiers. To these factors was added what General Jean Delmas qualified as “a certain innocence, a spirit of discipline, the oath (to Pétain) led l’armée d’armistice into passivity and powerlessness,” that sabotaged a staunch opposition to the Allied invasion in Morocco and Algeria.1 Unfortunately for the Allies, that same “passivity and powerlessness” that had facilitated success in Morocco and Algeria helped to shuffle Tunisia out of reach. From an Allied perspective, Tunisia offered AFN’s most exposed link, for several reasons. First, it was most vulnerable to Axis invasion either directly from Italy or through Italian Tripolitania, which made Tunisia’s defense a challenge. Second, at the Axis control commission’s insistence, Tunisia was sparsely garrisoned. But this had not especially worried the French, as Tunisia and the Constantinois were considered less likely targets of an Allied invasion. Therefore, defense measures were vague and ad hoc, despite the large concentrations of Allied planes and ships at Gibraltar noticed on 7 November.2 Third, Tunisia contained a large Italian population favorable to the Axis. Fourth, because Torch had prioritized Morocco over Tunisia, unlike in Casablanca, Oran, or Algiers, commanders in Tunis had to react not to an Allied armada, but to an Axis assault. Finally, no resistance mobilized in Tunis that might have disputed Axis access to Bizerte, or especially to El Aouina airfield in Tunis, the initial entry point of the Axis invasion, replicating Monsabert’s momentary sequestration of Blida outside of Algiers for Allied benefit, actions that might have bought enough time for an arrival of British troops.

This did not happen in part because of confusion and delay in Algiers, as Darlan and Laval attempted unsuccessfully to harness the Allied invasion to force Hitler to revise the conditions of the armistice. The result was “a succession of orders and counter-orders” that increased confusion in a way that basically “created competition among several headquarters, thus several commanders, each with a modicum of authority and all independent in the hierarchy of rank and functions in the chain of command,” writes Robin Leconte.3 Of the three main decision-makers in Tunis, two were admirals who took their rudder orders directly from Vichy, not Algiers. Meanwhile, the commander of ground forces in AFN, Alphonse Juin, complained that the Commandant supérieur des troupes tunisiennes (CSTT), General Georges Barré, failed to take decisive action to prevent the Axis seizure of El Aouina. In Juin’s telling, Barré’s “hesitation,” that triggered the Tunisian “tragedy,” was a direct consequence of the deliberate scrambling of the French chain of command upon Weygand’s 1941 departure. Barré’s primary concern was to keep his communications open with Algeria. This allowed Axis forces to occupy Bizerte and Tunis ahead of the arriving British First Army, thereby giving Rommel a new lease on life.4 Unfortunately, blaming subordinates and systemic command muddle became a convenient alibi for Juin to obfuscate his own role in the Tunisian “tragedy.” In January 1942, Juin had accurately anticipated events that would incite the Axis to invade Tunisia, and predicted almost exactly how that invasion would unfold.5 Why, then, were the French, and Juin in particular, not better prepared to react?

Most historians have focused rightly on Darlan’s nefarious role. Of course, Darlan was only playing Laval’s game to protect the zone libre by giving permission to Hitler and Ciano at Munich to invade Tunisia. When even that huge concession failed to protect Vichy’s sovereignty, Darlan reluctantly switched sides.6 Yet, Juin’s abdication of responsibility did not go unnoticed, either at the time or subsequently. Alternative explanations for Juin’s hesitation highlight the fact that, as a great admirer of Rommel, and facilitator of the Paris Protocols, he nurtured a pro-Axis bias. A more benign, Allied-friendly interpretation of his behavior suggests that, aware of the ambiguous loyalties of l’armée d’Afrique, Juin played the clock, certain that Berlin’s response to Torch would result in the invasion of Vichy’s zone libre. Such action would implode the 1940 Armistice, expose the hollowness of Vichy “sovereignty,” and tip French loyalties definitely to the Allies.7 Juin’s main concern was to maintain French control of AFN and prevent a Muslim uprising. He quickly concluded that assisting the Anglo-American invasion offered the best guarantee of continued imperial sovereignty.8

As in Algeria and Morocco, the tangled command structure combined with policy ambiguity and ethical uncertainty to produce “la confusion des ordres” in Tunisia and the Constantinois, which often whiplashed local commanders, who were either abandoned to make their own decisions or forced to decide which of their superiors’ contradictory directives to obey.9 This was compounded, in the view of Robin Leconte, by the realization that several senior French officers had conspired with the Anglo-Americans, which signaled a politically fluid situation that made commanders up and down the hierarchy reluctant to issue orders that might be countermanded by their superiors, or that their subordinates might not obey. Their decision not to act was confirmed by news from Algiers which arrived at the end of the afternoon of 8 November of a local ceasefire concluded between Darlan and American General Charles Ryder. Nevertheless, the order issued at 13:45 from XIX Corps commander General Louis Koeltz to General Édouard Welvert, commander of the Division de Marche de Constantine (DMC), had been to march on Algiers. When Welvert asked if that order were still in effect, he was informed at 18:45 that, “following the evolution of the situation, General Welvert has complete freedom to take all of the necessary measures.” In other words, the senior command had abdicated its authority, leaving officers on their own. Tension increased on 9 November as Luftwaffe aircraft began to land at El Aouina in Tunis and Sidi Ahmed airfield at Bizerte. Welvert was besieged by subordinate commanders demanding instructions, including Barré in Tunis, who reported that Vichy’s permission for Axis planes to land in El Aouina had brought French officers to the verge of mutiny. In other words, the French command was caught between the need to stop the spread of “dissidence” in the ranks and pressure to repel an Axis invasion.10

This confusion rippled down the chain of command to Sétif, almost 300 kilometers southeast of Algiers, where on Sunday morning, 8 November 1942, Second lieutenant Jean Lapouge, who had arrived only eight days previously in the 7e Régiment des tirailleurs algériennes (7e RTA), was awakened by his batman with news that the Americans had invaded. Lapouge hailed from a family of infantrymen, being the son of a colonel of Zouaves and the grandson of an infantry general. A devout Catholic and former Boy Scout, an organization whose motto was “son of France and a good citizen,” Lapouge’s destiny since boyhood had been Saint-Cyr. Although the French military academy had been shifted by the occupation from its Paris suburb to Aix-en-Provence in the zone libre, Lepouge had graduated with his class, baptized “promotion Maréchal Pétain,” only a few days earlier. As a native of Oran, he predictably had chosen an armée d’Afrique regiment upon graduation, which had assigned him to lead the machinegun platoon in one of its companies. It wasn’t much of a machinegun – a gas-actuated, air-cooled Hotchkiss that sat on a tripod and weighed 25 kilos. Each company was meant to maintain an inventory of four of them, as well as two 81 mm mortars. The Hotchkiss could in theory fire 450 8-millimeter rounds per minute. In fact, its firing strips held only 24 rounds, requiring its three-man crew constantly to reload. If, that is, they had any munitions – the Axis control commissions permitted the Constantine Division, of which 7e RTA was part, only 30 cartridges per rifle and 200 per machinegun for a 9-month period. The control commissions were equally parsimonious in their authorization of vehicles and petrol, which meant that the few trucks in the division’s inventory were most often requisitioned civilian vehicles in precarious mechanical repair.11 The result was a reliance on mules to transport munitions and other impedimenta. The Hotchkiss had been a state-of-the-art weapon – in 1914! But it was par for the course in the 7e RTA, whose two battalions were de-motorized and armed with Great War-vintage weaponry pulled by horse-drawn logistics. “Junk” was the verdict pronounced by American General George Patton when he had encountered French armaments at Casablanca in November. Under these circumstances, he marveled that the French fought as courageously as they did.12

Thinking his batman was engaged in a practical joke of the sort frequently played on new cadets at Saint-Cyr, Lapouge pulled the sheet over his head, rolled over and tried to go back to sleep. But the commotion in the corridor convinced him to rise, dress, and report to barracks, where he was confronted by his irate company commander, who reprimanded him for his tardiness. The DMC was reacting to Darlan’s order sent at 07:30 that morning to resist the Allied invasion. But there was no Allied activity reported off the Constantinois and Tunisia. Rumor circulated that several senior French officers in Algiers had defected to the Anglo-Americans. The regiment collected its equipment and marched north to Kherrata, a village in the Kabylia that dominated a narrow, north–south passage between Sétif and the Gulf of Béjarïa. “Our orders were to stop the Americans!,” Lapouge remembered, although why the French might think that the Allies on their way from Algiers to Tunisia might detour through Kherrata remains a mystery. The 7e RTA strung mines along the road through the narrow pass and sited their machineguns. The next day, amid rumors that American troops joined by defecting French soldiers were marching on Sétif, Alsace native and 7th Infantry Brigade commander Colonel Jacques (Jacob) Schwartz asked his DMC Commander Welvert for instruction: “Fire [on the mutineers] without hesitation,” came Welvert’s reply. Rather than fire on French troops, and apprised of German planes landing at El Aouina, Schwartz ordered his soldiers back to barracks.13 At 23:00 on 10 November, word finally reached Lapogue’s company that they were no longer to shoot at the Americans. On 14 November, the 7e RTA boarded a train that deposited them at Tébessa on the frontier with Tunisia. The following days melded into a fog of marches and counter-marches with heavy packs, with the fatigue of setting up camp only to break it down, and hike to a new destination.14

Lapouge’s change of orders, from battling the Americans on 8 November to joining them only two days later, suggested an extenuated transition accompanied by hesitation, prevarication, and a muddle of orders and counter-orders – in essence, a breakdown of authority and hierarchy which caused many officers to make their own decisions. In fact, Torch followed by the Axis invasion of Tunisia forced the French military to confront an existential crisis. Unlike conventional Second World War forces, where political authority remained uncontested, soldiers in France after June 1940 were forced to choose between different concepts of legitimacy. The French army had been humiliated by its 1940 defeat. The rationale for the armistice had been poorly understood in AFN, which had required Vichy first to dispatch Weygand to shore up the loyalty of its imperial soldiers and impose an oath to the Marshal, and subsequently to scramble the chain of command to thwart a wholesale defection. This ultimately boomeranged as it fragmented the response in AFN to the simultaneous Allied and Axis invasions of November 1942.

However, Torch, and the subsequent Axis invasion of Tunisia, triggered a lengthy six-day crisis as a splintered, confused, and politically insecure command in North Africa spewed imprecise, often contradictory, frequently canceled orders that ricocheted between Algiers, Tunis, Casablanca, Vichy, and Army and Navy commands with their separate and often conflicting political agendas, service networks and personal loyalties. Lower down this multilayered and whiplashed hierarchy, officers, with partial information and battered by rumor and confusion, were forced to choose which authority, which city, which service network, which intermediary commander, or which order or countermanded order to obey. French officers were often left to interpret the orders received in pragmatic ways. Together with time, this fluid situation multiplied misunderstandings and confusion in the military chain of command, creating space for initiative and the negotiation of individual “moral choices” within the hierarchical framework. Uncertainty and confusion generated competition between command echelons, and tensions within the rank structure between inter-dependent leaders and subordinates.15

Defending Tunisia

Even before the Torch planners began to consider the invasion of AFN, Tunisia was already viewed by senior French commanders as the critical node and the point most vulnerable to Axis invasion. However, one difficulty with the Vichy policy of “defense against whomever” in AFN was that it failed to define the threat and to establish clear strategic priorities for dealing with it. British advances into Cyrenaica in early 1941 had the French imagining how to reoccupy the demilitarized zone in southern Tunisia to disarm retreating Italians who might appear before the Mareth Line, a Maginot-like clutter of pill boxes and strong points built to seal the “bottleneck” between southern Tunisia and Italian Tripolitania. The arrival of Rommel in North Africa in February 1941 and the establishment of a strong Luftwaffe presence in Sicily had forced Weygand to consider the possibility of an Axis invasion of Tunisia. Le Délégué général du government had vehemently objected to the second Paris protocol struck between Darlan and Abetz on 27–28 May 1941, which would have allowed the Germans “in civilian clothes” to use Bizerte as a supply point for the Afrika Korps. By threatening to open fire on any German who appeared in Tunisia, he managed to scupper that part of the “protocol” at least, although the Darlan–Abetz bargain did spring Juin from his Oflag while eventually supplying 2,000 French trucks for the Germans.16 On 28 September 1941, with the Mediterranean increasingly engulfed in the war, Weygand had issued a defense plan that posited the most likely threats to AFN to be German incursions either through Spain and Spanish Morocco or into Tunisia with the naval base at Bizerte as the principal target.17

Deprived from 19 November 1941 of Weygand’s unifying vision and authority, Juin, Darlan, and de Lattre de Tassigny subsequently split over how best to defend Tunisia. At the base of this disagreement was the question of who might constitute the greater menace to AFN. With his navalist perspective and a more collaborationist construct of Vichy “neutrality,” Darlan’s priority was to defend against an attack by les Anglo-Saxons.18 As a land-warfare professional unencumbered by Darlan’s – and the French navy’s – ironclad Anglophobia, Juin, like Weygand, was preoccupied with the possibility of an Axis incursion either from Sicily or through the Mareth Line. But, mindful of Weygand’s fate, “prudence” initially required Juin merely to list the potential invasion routes into AFN rather than prioritize them for his subordinates. However, when, on 30 January 1941, Juin issued his instruction personnelle et secrète (IPS) detailing the Axis threat to Tunisia, it raised such a tsunami in the collaborationist spas of Vichy that he ordered it destroyed. Henceforth, rather like Alsace-Moselle, the defense of Tunisia against an Axis incursion became something to be thought of always, but spoken of never.19

In the absence of an agreed-upon external enemy, predictably the French high command declared war on each other. During his time as Délégué général and taking inspiration from those “hedgehogs” that had imploded on the Somme and Aisne in 1940, Weygand had envisioned taking a stand in the north by transforming Bizerte and Tunis into a French Tobruk. In November 1941, Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, commander of Tunisian ground forces (CSTT) from September 1941 until he was relieved in February 1942, and Alphonse Juin, land forces commander in AFN, had wrangled over how best to secure the Maghreb’s eastern marches. That what should have been a sober staff Kriegsspiel quickly degenerated into an ad hominem slanging match was hardly surprising, as Juin and the temperamental de Lattre had been bitter rivals since Saint-Cyr.20 Speaking as the resident français d’Algérie, and from a geopolitical optic that considers geography as destiny, Juin viewed Tunisia as “merely the prolongation towards the east of Algeria’s Constantinois.” Juin’s mandate was to defend AFN, of which Algeria – sovereign French territory – was the keystone, with vulnerable protectorates buttressing the flanks. Judging that a forward defense of Tunisia was impractical, Juin’s preference was for French forces to fall back on the Tunisian Dorsal, the eastern extension of the Saharan Atlas that slices through the frontier between Tunisia and the Constantinois. Not surprisingly, perhaps, while Juin’s early strategic withdrawal was subsequently endorsed by the French official history of the campaign, many contemporaries found it questionable.21

Juin dismissed de Lattre’s vision for a forward defense on the Mareth Line as impractical without air cover and adequate logistics. The debate was further complicated by the fact that no one could agree whether the main threat was through Tripolitania in the east or Bizerte in the north. Juin won the argument by backchanneling Darlan, then Defense Secretary, that he too feared a British incursion through Tripolitania, and encouraged him to work Wiesbaden for the very reinforcements, armaments, logistical capabilities, and upgrades of the Mareth Line that would make de Lattre’s plan feasible. It was in this context of working to secure German cooperation for the defense of southern Tunisia against the British that Juin had met with Göring and General Walter Warlimont in Berlin on 21 December 1941.22

But, in the opinion of one of his biographers, the actual reason for Juin’s rejection of de Lattre’s concentration in southern Tunisia was that it posited a scenario of Erwin Rommel in search of a Tunisian sanctuary should he be put to flight in Egypt and harried across Libya by the British. Were that to happen, Juin had no intention of resisting Rommel, Jean-Christophe Notin speculates, but rather would join forces with him to fight the British. “We’ll fight the Anglo-Saxons. I guarantee it,” Juin had promised Laval. This alleged declaration joined the widely accepted rumor that Juin had given his word not to take up arms against Germany as a condition for his release from Königstein, to become the ball and chain that the controversial Marshal of France dragged behind him for the remainder of his life.23 A skeptical Costagliola counters that Juin had been made well aware, in the wake of his failed December 1941 encounter with Göring and Warlimont, that the political and military foundation for a joint Franco-Axis defense of southern Tunisia had not been laid. Furthermore, Juin feared that to make common cause with the Axis would open AFN to Anglo-American reprisals. The bottom line was that Berlin did not trust the French, fearing that, if they were allowed to rehabilitate the Mareth Line, it might be used to block Axis forces retreating across Tripolitania.24

But whatever the complaints about Juin’s character – and they were legion – most admitted that his strategic analysis was thorough, a trait that would make him especially appreciated by the Americans. Juin’s predilection to fall back into Algeria was also based on the realization that Tunisia offered a fragile redoubt for the defense of AFN. At Italian insistence, Tunisia was lightly garrisoned, with only one lean eight-battalion division of around 12,000 troops, scattered in garrisons throughout the territory.25 Juin complained that the significant Italian population in Tunisia and eastern Algeria contained many Axis sympathizers, who compromised his ability to camouflage troops as native police, scatter supplemental soldiers in inconspicuous remote garrisons, or create secret arms caches, as had become commonplace in Morocco.26

If the loyalty of the European population was in doubt, the potential for indigenous defection was even greater. In August 1942, the French had incarcerated Habib Bourguiba, the leader of the Tunisian nationalist party Neo-Destour at the Fort Saint-Nicolas in Marseilles. And while Bourguiba had counseled his followers not to be seduced by Axis blandishments, Tunisian Muslims were bombarded by appeals from such pro-Axis stations as Radio Bari, Radio Berlin, Radio Roma, and, from January 1943, Radio Tunis, as well as being showered with tracts written by the propaganda office of Major Mähnert in Tunis and distributed along the front, promising favorable treatment to tirailleurs and Frenchmen who deserted to Axis lines. However, treachery seems not to have been widespread among the 26,000 Tunisians eventually incorporated into the French army between 1942 and 1945, in large part because it did not take a genius to realize, in the wake of El Alamein, Stalingrad, and Torch, that Axis days were numbered. Nevertheless, the food situation in AFN continued to be a critical worry for French officials, who feared that famine might shift the loyalties of Muslims in Morocco and Algeria toward the Axis. So, Juin had to calculate what percentage of his meager forces should be held back for internal security.27

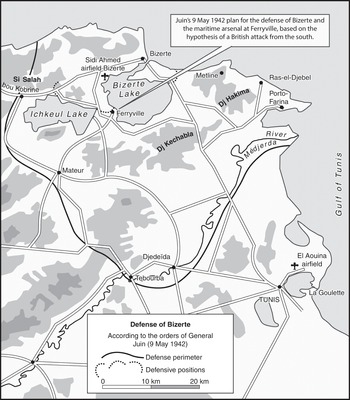

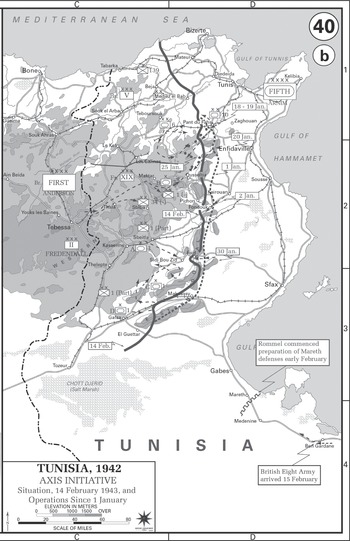

In January 1942, de Lattre was relieved by Juin protégé Georges Barré, in a switch-out that permanently damaged relations between two of France’s most senior generals. In the short term, however, the July 1942 fall of Tobruk and Rommel’s subsequent surge into Egypt, that helped to precipitate the Allied decision for Torch, had seemed to render the Juin versus de Lattre strategic debate temporarily academic. By January 1943, when Rommel did appear on his Tunisian doorstep, Juin and his armée d’Afrique had wobbled into the Allied camp. Rommel’s one-time aficionado now became his antagonist.28 But, if de Lattre’s Mareth Line defense scheme had departed with his recall to France, no agreed-upon plan to defend Tunisia (Map 1.1) had been resolved. In Weygand’s view, holding Bizerte was vital. In February 1942, Darlan also had informed Juin that the retention of Bizerte in the face of a British attack was “primordial” even at the expense of other points, because it would “attract the maximum of (British) assets.”29

Map 1.1 Map of northern Tunisia.

Following Darlan’s directive, Juin, together with Barré and Bizerte commander Vice-Admiral Edmond Derrien, wargamed the defense of Bizerte on 8–11 April 1942. Juin’s conclusion was that the defense of Bizerte’s harbor, arsenal, and industrial facilities would require a defense perimeter 104 kilometers long. Defending this perimeter would require the totality of French reserves in AFN and “risk the fate of North Africa and the field army on a single battle.” His solution was to remove Bizerte from control of the CSTT, and hand its defense over to Derrien, who would concentrate on defending Ferryville, at the southern end of the Lac de Bizerte, which contained France’s sole overseas navy yard and arsenal, and the Menzel Djemil isthmus that separates the Lac de Bizerte from the sea. In the meantime, three divisions of troops rushed from Algeria and Morocco would lift the siege of Bizerte within thirty days. Juin’s plan was confirmed in a 9 May 1942 IPS, and CSTT Barré was to finalize its details by 22 August.30

In his memoirs, Juin insisted that his plan simply remained faithful to Weygand’s vision.31 Unfortunately for Juin, he was sent back to the drawing board by Darlan, now commander in chief of French forces, and Pierre Laval, who had been restored as premier in April 1942. “The military value of Tunisia remains in its harbors,” Darlan lectured Juin on 2 May, and “The Tunis–Bizerte group must be tenaciously defended, above all Bizerte … The defense of Bizerte against a land attack must be reevaluated; covering forces must fight tooth and nail to keep the enemy for as long as possible far from the position; the battle for the isthmuses being the final recourse.” Because Darlan’s corrective arrived at the last minute, Juin’s 9 May IPS, which renounced the defense of Mareth, of the eastern ports of Gabès, Sousse, and Sfax, and of Tunis, remained the battle plan for the moment. But it nevertheless specified that, although abandoned, “their harbors and airfields would be rendered unserviceable” (italics in the original). But this admonition lacked urgency, because the calculation at Vichy was that other imperial locations were judged to be more likely Allied objectives, a strategic misstep reinforced by the 5 May 1942 British seizure of Diego-Suárez (now named Ansiranana) in Madagascar. So, it did not seem to matter much that command of Bizerte would fall to Admiral Derrien, while “the command of Tunisia” would revert to CSTT Barré, “charged with organizing the south, and the center of Tunisia, and to hold the mountainous zone to the east of Béja.”32 These remained Barré’s marching orders, modified slightly by a further IPS – Juin’s last before Torch – of 22 August, that laid out the “phases of maneuver” that incorporated Darlan’s instructions “to insure no matter what the preservation of Bizerte.” But the assumption upon which Juin’s defense plan was based remained a British attack on Bizerte from the south.33 In the event, the enemy, the direction, and the configuration of attack diverged wildly from Juin’s planning assumptions.

But conflict scenarios seemed remote in AFN’s somnambulant autumn of 1942, as Rommel had kicked the British into the Nile delta, Juin shuffled his troops away from the beaches and back to their winter quarters in Morocco, the Wehrmacht slouched toward Stalingrad, and the decadent Americans seemed incapable of wresting the distant island of Guadalcanal from Japanese control. Vichy’s complacent planners settled on “stalemate” as the war’s ascendant narrative. At least this postponed the need to reconcile conflicting threat assessments, and problems caused by a splintered chain of command and a penury of troops and matériel. But Juin at least recognized that this disorder at the top delivered mixed messages to l’armée d’Afrique that translated into “hesitations and contempt, because resistance to one implies for better or worse collaboration with the other.”34 This wavering at the top, accelerated from 8 November by the fact that the command in Algiers was taken hostage, first by a resistance group and subsequently by the Americans, produced a “lassitude” in the leadership, stoked fear that “dissidence” had compromised l’armée d’Afrique, and abandoned officers at the local level to their own devices. In these conditions, Costagliola points out that officers were freed to decide on the “relative value” of orders according to when they were issued and who or what service issued them, even as the octogenarian Marshal at Vichy squawked “You have heard my voice on the radio, it is the one you must obey.”35

A Confused Chain of Command

Finally, and most critically, if Torch had triggered Vichy’s unmasking, the slow-motion treason that played out in Tunisia further disaggregated and paralyzed an already-contorted French chain of command. Not surprisingly, while a system cross-wired to short-circuit potential pro-Allied conspiracies in AFN perhaps served the purposes of Vichy “neutrality,” it hardly optimized French defense of Tunisia against invasion, especially when command consensus over the most likely threat to AFN, and how to counter it, remained undefined and in dispute.36 Nor did it match Torch planning assumptions. In August 1942, the British Joint Intelligence Committee opined that the rapid arrival of Allied forces in Tunisia would forestall a large Axis invasion. A major premise – indeed, aspiration – of the decision to attack Casablanca had been that token French resistance would delay an Axis invasion of Tunisia long enough to permit Allied forces to leapfrog east from Algiers to Bône, and overland to Tunis. Furthermore, Allied planners had calculated that it would make no strategic sense for Berlin and Rome to commit substantial forces to a major campaign in Tunisia.37 Unfortunately, Hitler had been taking decisions that defied military logic at least since his September 1939 attack on Poland – some might argue ever since the 1935 remilitarization of the Rhineland. And while, in November 1942, the jury was still out on Stalingrad, so far, Der Führer’s gambles had mostly paid off. Nor could Torch’s architects factor in the likely reactions of the French high command in Tunisia, largely because they were indecipherable. But, in the event, even Allied hopes for token French resistance in Tunisia would prove illusory. In November 1942, “Defense against whomever” joined “la comédie politique d’Alger,” the fragmentation of the French chain of command, and Juin’s reflex to retreat into Algeria, leaving the door to Tunisia ajar to Axis forces.

The September 1942 command reorganization that separated AFN into “terrestrial” and “maritime” sectors, in theory, had divided military authority in Tunisia as elsewhere in AFN, into army and navy spheres. The “terrestrial” theater in Tunisia, stretching from the lower Medjerda valley to the frontier with Tripolitania, was commanded by Barré. A decorated Great War veteran, CSTT Barré had spent virtually his entire career in l’armée d’Afrique, commanding the 7th North African Division in 1940. A Weygand protégé, he was subsequently retained in the Armistice Army, assigned in late 1940 to oversee the demilitarization of the Mareth Line. Barré was also an acolyte of his superior in the hierarchy, Juin, who had eased his promotion to lieutenant general (général du corps d’armée) as a prelude to de Lattre’s February 1942 reassignment under protest to lead a stripped-down Armistice Army “division” at Montpellier. Juin’s little command coup supplanted the temperamental and ambitious de Lattre with the less able but more pliant Barré. Juin’s command changeout was also meant to insure that, in the event of invasion, French troops in Tunisia would not be locked into a sacrificial defense of Bizerte and Tunis, thus opening Algeria to invasion from the east. If Juin could not win his strategic argument with Darlan and de Lattre on the merits, he would prevail through a reshuffle of personnel.

Tunisia’s “maritime” sector translated into the “arrondissement maritime de Bizerte” that extended from the coast, down the Medjerda valley to the Algerian frontier. Its commander – a sixty-one-year-old, one-eyed veteran of the First World War, Edmond Derrien – had been slated to retire in 1941, and probably wished that he had. But as an ADD (ami de Darlan, friend of Darlan), he had been enticed to stay on with a promotion to vice-admiral. Many believed that Derrien had been elevated above his competence, as his nickname on the lower decks was Der-rien-de-tout (not up to much). His command included the “fortified camp” of Bizerte that incorporated France’s sole overseas naval arsenal and shipyard as well as the harbors of Tunis, Sousse, and Sfax. A garrison of soldiers called “le groupement de Bizerte” defended the Bizerte naval compound.38 For matters of naval combat and defense of harbor installations, Derrien’s immediate superior was Admiral Moreau, prefect of the IVe Région maritime in Algiers. However, “in the event of operations,” Derrien fell under the orders of the “General commanding the Theater of operations in Tunisia for everything concerning the defense of the Bizerte sector.” This should have been Barré, who held the same rank as Derrien, but who answered to “the Commander in Chief in North Africa” – namely Juin.39 The fact that the “groupement de Bizerte” was commanded by Derrien and not Barré would further disarticulate the French response because it would resurrect the Darlan–Juin quarrel over the strategic value of Bizerte, set the navy against the army, and ultimately sabotage the authority of Darlan, Juin, and Moreau in Algiers in favor of Vichy and Tunisia’s Resident General, Admiral Jean-Pierre Esteva.

This was because Derrien was close – physically, personally, and through service affiliation – to Esteva (Figure 1.1). German diplomat and self-styled Arab authority Rudolph Rahn described the Resident General and Dardanelles veteran as a “Gentleman of a certain age, stocky, with a large gray beard, boasting a reputation for a profound piety and a sense of almost infantile self-satisfaction.” Nevertheless, he judged Esteva “incapable of making any decision.”40 Esteva answered in theory, through Vichy’s foreign affairs secretariat, ultimately to Laval. But, because he was also a full admiral who had commanded both the Far East and the Mediterranean fleets, he had close personal relations with Darlan, whom he addressed in the familiar tu form, as well as with Admiral Gabriel Auphan, who managed the Vichy admiralty.41 The chain of command technically ran through General Georges Revers as chief of the general staff to Eugène Bridoux, the secretary of state for war, or to Auphan, who was both head of the French Admiralty and Commander in chief of Maritime Forces, who depended for their authority on Laval and ultimately Pétain. In fact, after some initial soul searching, Derrien would opt to follow the orders of Esteva and Vichy, rather than listen to Juin and Darlan.

Figure 1.1 Admiral Jean-Pierre Esteva, Resident General of Tunisia, with German representative and Arab expert Dr. Rudolf Rahn, and Major Henri Curnier, commander of the Légion des volontaires français contre le bolchévisme in Tunisia, at the entrance of Bordj Cedria camp (Borj Cédria, Tunisia) on 15 March 1943.

Two Commanders, Two Choices

The reaction in Tunis to news of Torch would be complicated by command turmoil in Algiers, multiple scenarios for the defense of Tunisia, none of which seems to have received final command imprimatur, and a tortuous multi-service chain of command, with Tunis, Algiers, and Vichy all claiming precedence, and through which arrived orders, instructions, suggestions, and directives to the men on the ground. As a consequence, as elsewhere in AFN, drift, equivocation, and confusion characterized the leadership in Tunisia on 8–13 November, as communications were periodically severed, and contradictory orders arrived from various headquarters. Claims of authority from Darlan, Juin, Noguès, or Esteva, not to mention assorted figures at Vichy, as well as uncertainty that subordinate commanders would follow orders that ran counter to their individual consciences, combined to stifle command initiative. The result during those fateful hours and days, as the “orders and counter-orders” ricocheted across and around Mediterranean shores, was that Barré and Derrien shared with their superiors a culpable hesitancy and indecision, even passivity, in the face of an initially anemic Axis invasion, which filtered down to their subordinates, whose attitudes influenced their command choices.42 By 14 November, “the passivity which had begun through indecision had … to be continued because of material weakness,” concludes Paxton.43

A “menace” warning went out in the late afternoon of 6 November as reports reached Tunis of an Allied naval buildup at Gibraltar.44 In the late morning of 7 November, troops in Constantine and Tunis were put on alert. That evening, Juin ordered Barré to deploy his defense dispositions for the harbors, beaches, and airfields in Tunisia. Moreau passed on Darlan’s order to block the Bizerte shipping canal, but in a very oblique manner that left Derrien much leeway.45 The 8 November opened at 00:25 with a warning from the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) of the possibility of Allied landings at Bône, Philippeville, or Tunis, and the OKW offered Luftwaffe support to the French. At 01:00, American consul in Tunis Hooker Doolittle presented Esteva with a letter from President Roosevelt announcing that the invasion was, “uniquement des Américains,” and asked that American troops be granted free passage into Tunisia, which Esteva rejected. At 01:45 on 8 November, Barré received an order from Juin “to put in place, at 08:00, the first echelon of troops designated to defend ports and beaches in the Tunis subdivision, the air bases and landing zones. Keep other subdivisions on alert.” As a result, Barré subsequently issued a stand-to order condemning “Anglo-Saxon” aggression and admonishing his soldiers “to execute the orders of the Marshal.”46 At 03:50, as news of the attack on Oran arrived, Derrien sent out a “défense totale” order, which required the manning and arming of coastal batteries, preparations for the defense of the Bizerte arsenal, and the call up of reservists. At 05:00 the Germans offered Luftwaffe support from Sicily, followed by proposals to send Luftwaffe liaisons to Tunis to coordinate operations. At 09:45, an order from Vice-Admiral Auphan – “We are attacked. We will defend ourselves. That’s my order” – was disseminated to all services. He directed that the La Goulette canal be blocked to deny entry into Tunis harbor.47

At 14:00, Vichy gave its permission for two Luftwaffe liaison officers to reach AFN to coordinate operations with the CSTT.48 Barré learned in the late afternoon through the Vichy war secretariat that, “in the case that General Juin can no longer exercise command,” Darlan had put him in charge of an operational theater designated as “Tunisia–Constantine,” which mirrored the Morocco–Oranais command arrangement that had been imposed on Noguès. “Thus, at the end of the day on 8 November, the situation seemed clear,” declares the official French naval history. “General Barré had taken command of the Eastern Theater and the defense plans were activated. The adversaries were the Americans and the British.” The Axis announced that they would dispatch the Schnellboot (or S-Boot, rapid attack boat) flotilla based in Sicily to Tunisia, together with Italian troops and 88 mm dual-purpose anti-aircraft and anti-tank guns originally designated for Rommel.49 However, a telephone conversation between Barré and his new subordinate Major General Édouard Welvert, commander of the Constantine division, concluded that there was no Allied invasion in their sector, which caused them to doubt the information they were receiving. Their main concern seemed to be the reports of the “dissidence” at Algiers that had temporarily detained Juin and Darlan, and the fear that there might be similar plots afoot in Constantine or Tunis.50

The problem was that the definition of “dissidence” was evolving, as the navy gradually assembled under the banner of Pétain and Esteva, while the army elected to follow the orders of Darlan, Juin, and XIX Corps commander Louis Koeltz.51 Obeying Darlan’s message, on the morning of 9 November, Barré ordered his scattered and ill-armed forces to prepare to resist the Allies as the “first aggressors,” although in his memoirs he insisted that his positions were “reversible.” At midnight on 8 November, the German high command had sent an “ultimatum” to the French government via the German armistice commission at Wiesbaden that the Luftwaffe must be allowed to base planes in Tunisia and the Constantinois to resist the Anglo-American invasion. This was followed by permission from Vichy at 08:45 on 9 November for Axis forces to use the air bases in Tunisia and Constantine, as well as the ports of Bizerte and Tunis. Darlan informed Barré at 07:00 on 9 November that “The Americans, having been first to invade Africa, are our adversaries and we must oppose them alone or with help.”52

On 9 November, the commander of the Sétif subdivision, Colonel Jacques Schwartz, received a report that American and French troops had left Algiers marching toward the southeast and asked Welvert about “the attitude to adopt if it’s a question of non-loyal French troops?” The Division Commander ordered him to “shoot without hesitation,” which presumably resulted in Lapouge’s 7e RTA being ordered to defend the Kherrata pass.53 In the morning of 9 November, two Luftwaffe liaison officers dispatched by Kesselring arrived at El Aouina, the Tunis airport, after having first landed at Sétif in an unsuccessful attempt to contact Darlan. During their meeting with Barré and Esteva, the two officers announced that German aircraft would soon be arriving in Tunisia, and handed the two Frenchmen “a list of requirements that constituted the basis of military collaboration.” Barré ask for a postponement: “We told them that we would let them know our response after consultation with the Marshal and the Chief of the Government. Our interlocutors agreed to await this reply.”54 At 05:20 on 10 November, Barré was informed that General Bridoux at Vichy had given permission for the Germans to land at El Aouina. In a communication with Welvert, Barré expressed concern that Vichy had allowed the Germans to land before the Allies had attacked Tunisia, and that this had caused “unsettling commentaries from the majority of officers on whose loyalty I can no longer count.” In other words, the command was beginning to get pushback from its subordinates over its decision to allow the Axis unfettered access to Tunisia. Perhaps this resistance was encouraged by news that arrived at 11:00 on 10 November, that Darlan had signed an armistice with the Americans, news incompatible with Barré’s order to allow German planes to land at El Aouina. At 17:55 on the evening of 10 November, Welvert at Constantine received the order from Juin to “resist the Axis.” But three hours later, he complained to XIX Corps commander Koeltz that Tunis was telling him the opposite. “What should I do?,” he asked. Koeltz’s answer: “absolute neutrality.” In Leconte’s view, this offered an example of how a subordinate in the French hierarchy avoided responsibility for executing orders “of doubtful origins.” He did not ask for a written confirmation of Barré’s order. Rather, he simply sought out someone else in AFN’s fractured military hierarchy who would supply a different directive, which allowed him to take no action.55

The French official history insists that the German demand to use El Aouina was an ultimatum, not a request, one acquiesced to by the French representative at Wiesbaden – fifty Ju 52s, twenty-five Ju 87s, twenty-five Messerschmitt Bf 109s, two Ju 88s, and one Ju 90 appeared over Tunis at 12:30, flying so low that their black crosses and even, some claimed, the faces of the pilots were visible from the ground.56 A detachment of the 4e RCA with two squadrons of tanks under the orders of Colonel, later General, Guy Le Couteulx de Caumont took up a position on the hill overlooking the airbase. An after-action report written on 19 November 1946 placed the Luftwaffe’s arrival (Figure 1.2) three hours later.

Around 15:30 the sky was full of vibrations of the first German planes overflying Tunis before landing at El Aouina. A motorized detachment of the 4e RCA (Régiment de chasseurs d’Afrique) was ordered to El Aouina to oppose the arrival while a battery of the 52e RAA (Régiment d’artillerie d’Afrique) took up a position in the region of Notre-Dame du Belvédière overlooking the air field. The alert was given – the German landing had begun. The news spread like wildfire … The motorized detachment of the 4e Chasseurs arrived on the airfield just as the large transport planes were offloading their cargos. The armored vehicles took their position, their turrets swung round, the machinegunners with their fingers on the triggers. In a few seconds, the planes with their black crosses would be the first objectives – emotions were taut. But the brief order rang out: “don’t shoot.”57

If this post-war report fails to mention who issued the stand-down order, it was because, far from opposing the Germans, Colonel Le Couteulx’s mission, according to the 1946 after-action report, was to “assure the protection of the Axis detachments and see that they don’t venture beyond El Aouina to avoid any incident at Tunis were they to go there.” Barré was to prepare an order explaining the government’s decision to allow Axis use of Tunisian airfields. In the meantime, French forces deployed to prevent an Allied amphibious landing. Shore batteries were armed, submarines prepared to sortie, while ships were scuttled to block the entrances to the harbors at Bizerte, La Goulette at the entrance to Tunis harbor, and Sfax.58 When Welvert sent the 3e RCA on a reconnaissance of southeastern Tunisia, its commander, Lieutenant colonel Pierre Manceau-Demaiu, was informed by the naval command in Sfax that “at a minimum” they would assume an attitude of complete neutrality toward Axis forces. When Manceau-Demaiu urged that they adopt an aggressive posture toward the Axis, naval officers denounced him as a “dissident” and threatened forcibly to take over command of his squadron.59 A similar “economy of force” reflex saw Air Force chief in AFN General Jean Mendigal order his pilots to evacuate their aircraft to Biskra in southern Algeria, well out of harm’s way, an order which Juin never reversed after Mendigal had refused his superior’s direct order on 11 November to resist Axis forces. Obviously, “defense against whomever” excluded resistance against Axis forces.60

Unfortunately, as Darlan prevaricated and Clark threatened in Algiers, from 9 November, Axis forces had been allowed resistance-free access to Tunisia, “courtesy of the French authorities.”61 Furthermore, by exposing the hypocrisy of “defense against whomever,” Vichy had gambled on the loyalty of l’armée d’Afrique. “I must tell you what emotion this occupation of El Aouina by the Axis air forces has caused, and the unsettling commentaries that it has provoked among the majority of officers upon whose loyalty I can no longer rely,” Barré reported to Vichy on 9 November.62 After being notified of the landings at El Aouina and that an Axis convoy was scheduled to arrive at Bizerte, Derrien had what the Viard Commission, set up in August 1943 to investigate command behavior in Tunisia in November 1942, called “his first ‘National’ reaction,” when he signaled the Admiralty at 16:00 on 9 November: “I must inform you that these events have produced reactions that for the moment I can control in the army, the air force and the navy at Bizerte. But I cannot answer for the consequences.” In other words, Vichy was being informed by its senior commanders that the rank-and-file military was unwilling to accept collaboration with the Axis. And while Axis use of air bases such as “Sidi Ahmed (Bizerte) and El Aouina (Tunis) might probably be acceptable, a joint occupation certainly will not be.” The French Admiralty replied that the Anglo-Americans had initiated the crisis, and that Vichy had no choice but to “submit” to Axis force majeure. “Obey Navy Commander in Algiers (Moreau),” the Admiralty urged. In a message to Esteva, Vichy’s Secretariat of Foreign Affairs too laid the blame on the Anglo-Americans and pleaded that they were powerless “to prevent one or the other of the belligerents carrying the war onto our soil.” At least, it pointed out, “The government has [already] requested that no Italian reinforcements be sent to Tunisia and count on this being honored.”63 Clearly, the Maréchalisme of the armed forces in North Africa was taxed to breaking point as Berlin and Rome exposed the duplicity of “defense against whomever.”

“A new phase opened, of a particular character,” the 19 November 1946 report continued. “At that point, it was a question of delaying the enemy forces without fighting them. One had to avoid engagement at all costs, but nevertheless contain the advance of the invader.”64 In fact, this 1946 report tried to portray French confusion, prevarication, and the passive posture adopted both by the Constantine division and by the CSTT in the face of Axis invasion as a clever delaying strategy against Axis forces.65 As Leconte demonstrates, inaction was rather the response of an insecure senior command caught between pressure from their subordinates to resist the Axis and fear of issuing an order that would set the spas of Vichy boiling. On the morning of 10 November, Darlan proclaimed a ceasefire throughout AFN and “complete neutrality toward all the belligerents.” These instructions were passed on to both Barré and Derrien at noon, who relayed the order to their subordinates. Moreau in Algiers also directed commanders in Bône, Philippeville, and Bougie not to resist American arrivals in those harbors. However, amid complaints that Barré was not cooperating with the Germans, and insistence from Auphan that the Bizerte channel be unblocked to allow access to the Axis flotilla, in the afternoon of 10 November, the Admiralty announced that the Germans had been given free access into Tunis and Sfax. The Secretary of State for War at Vichy, General Eugène Bridoux, forwarded the same information to Barré, with instructions to avoid contact between French and German troops while not abandoning Tunisian soil.66 In the evening, Barré learned that Juin had been reinstated as commander in chief. At 23:00, Auphan messaged that an Axis flotilla would soon arrive at Bizerte. Consequently, the harbors at Bizerte, Tunis, and Sfax were to be unblocked, an order rescinded on the next day, 11 November.67

The French army’s official history asserts that orders to resist neither the Americans nor the Axis placed Barré in an “ambiguous position.”68 At this moment, however, directives from Algiers and Vichy began to diverge for good. According to Notin, only on 10 November, two days after the Allied invasion had been launched, did Juin contact Barré by telephone.69 The CSTT told Juin that Vichy had given permission for the Germans to land at El Aouina. Rather than contradict those instruction, at 19:30 on the evening of 10 November, Juin gave the following order: “Take dispositions to resist and cover communications [with] Algeria.”70 In other words, Juin preferred to defend Algeria, rather than prevent the Germans from seizing El Aouina. At 17:30 on the evening of 10 November, lumbering Bristol Beaufighters flying from Malta attacked El Aouina and left a Luftwaffe tanker, three fighters and two bombers in flames as well as two German pilots gravely wounded. This British attack caused Le Couteulx’s 4e RCA, allegedly stationed as observers at El Aounia, to scatter and regroup at Pont du Fahs.71 German air reprisals fell on Bône, Philippeville, and Bougie. On the morning of 11 November, Derrien ordered the French fighter squadron at Sidi Ahmed outside of Bizerte to withdraw to Kairouan to make room for arriving German fighters.72 Derrien would later disingenuously complain that he could not defend Bizerte in part because he lacked air cover.

On 11 November – the critical day in Tunisia – events began with Juin informing Vichy that, as Pétain had disavowed Darlan’s ceasefire order and “Given that with Admiral Darlan I am in the hands of the Americans, in my judgment I am unable to exercise command of operations and can only give complete independence to the commanders of the eastern and western theaters (Noguès and Barré).”73 The Vichy admiralty insisted that Noguès was now in command in AFN, and that the order to resist the Anglo-Saxons remained in force. A communication from Auphan that arrived at 14:55 explained that while “my personal preference is passivity vis-à-vis all belligerents,” the government’s decision on the posture to adopt against the invaders would be reached on that evening. Desperate for clear orders, Derrien at Bizerte phoned Moreau, Esteva, and Barré in an attempt to cut through the confusion. “It’s difficult to exercise command,” Moreau told Derrien, because the Americans had cracked down on French radio communication between the Hôtel Saint-George and Bizerte. “I delegate authority to you over your military establishment. Tell the Resident General,” came Moreau’s pass-the-buck message to Derrien – “in other words, ‘sort it out yourself,’” in the unvarnished language of the Viard Commission. That proved difficult to do when Esteva insisted that Darlan had been disavowed by the Marshal, Juin “had given a free hand to Barré–Derrien in Tunisia” (in fact, he had ordered Barré to retreat to Algeria), and, at noon, news arrived of the German invasion of the zone libre, that allowed Darlan to “reclaim his liberty.” Barré told Derrien that he was following the order to remain “neutral” and planned that evening to begin withdrawing his troops, transport, and matériel to the west, a move that had been approved by Esteva. In these confused circumstances, the only military order that a “disconcerted” Derrien could think to issue was to prepare to scuttle.74

On 11 November, German forces had begun to disembark at Bizerte and La Goulette (Tunis), while the Luftwaffe airlifted more troops into El Aouina and Sidi Ahmed, the Bizerte airfield. At 08:45, Derrien informed Auphan at Vichy that “my understanding is that the arrival of German troops in Tunisia is authorized. The struggle continues against the Anglo-Saxons.” Juin also told Barré by telephone that he was to observe “strict neutrality toward all belligerents.” At 10:35, Barré informed Esteva that he would begin his withdrawal toward the Dorsal. Esteva raised no objections, while Juin also gave him the go ahead to depart “in the evening of 11 November.” But news of the invasion of the zone libre caused Moreau in Algiers to signal at 15:47 that “We reclaim our freedom of action. The Marshal no longer being free to take decisions allows us to take those which are more favorable to French interests, while remaining loyal to his person.” Juin, too, urged that the Axis invasion be resisted: “From the reception of this order the position of neutrality vis-à-vis the Axis ceases,” read his Order 395, sent out in the afternoon of 11 November. “All attempts at intervention by Axis forces in AFN must be resisted with force. Prepare for active operations.” This was followed by Order 396, which told XIX Corps (Koeltz) to put Algeria on general alert, recover camouflaged material, deny the Luftwaffe access to air bases in the Constantinois, and liaise with US forces. At roughly 17:00, Juin phoned Barré to tell him to “beat it” out of Tunis to a line running through Béja, Medjez-el-Bab, and Téboursouk. As commander of the only motorized force in Tunisia, Le Couteulx was diverted from El Aouina, where he might easily have mastered the roughly 1,500 lightly armed Axis troops there, to cover Barré’s retreat. At 17:00, Barré phoned Derrien from Esteva’s office to say “Everything’s changed. We’re fighting the Axis.” Left to defend Bizerte, Derrien too informed the soldiers and sailors of the Bizerte garrison that “Our enemy is the German and the Italian … Go for it with all your heart against the adversaries of 1940. We must avenge ourselves. Vive la France!”75

However, Juin quickly realized that his desire to take the fight to the Axis, still thin on the ground in Tunisia on the afternoon of 11 November, was not universally embraced by his senior subordinates. Esteva avoided contact “on a transparent pretext [a visit to the Bey] and probably to cover himself if need be.” Esteva then forced Derrien to withdraw his order to resist the Axis allegedly because it opened Barré’s retreating troops to attack. As Barré and his staff departed for Souk-el-Arba, Derrien received strict orders from Auphan in the Admiralty that “you must allow the Italo-German forces disembarking in Tunisia free passage without getting involved. Follow the orders of the Marshal.”76 Exercising his legendary prudence, at 20:00 on 11 November, Juin issued Order 397 that “suspended” Orders 395 and 396. He later insisted that this stand down was issued because Koeltz and air force commander Mendigal refused to act until given the green light by Noguès, whom Vichy had named to replace Darlan. Also, Barré feared that it would subject his retreating troops to Luftwaffe attack before they reached Medjez-el-Bab.77 At this point, the Viard Commission recognized Derrien’s dilemma: Barré and Juin refused to reinforce Bizerte; Esteva claimed to want no action that allegedly might jeopardize Barré’s retreat, but in fact made himself unavailable for command; Vichy ordered him not to oppose the arrival of Axis forces; while Noguès’ silence was deafening. At the same time, Kesselring redirected General Walter Nehring, who had been passing through Rome on his way to take command of the Afrika Korps, to take charge of the buildup in Tunisia and advance his troops toward the Algerian frontier.78

Juin’s decision to withdraw Barré from Bizerte–Tunis opened him to criticism. On 12 November, the French still maintained an overwhelming superiority over what was estimated to be 1,000 German soldiers with a few anti-aircraft guns at El Aouina, 20 fighters at Sidi Ahmed, and 2 Italian troop transports at Bizerte, that had yet to offload their artillery and tanks, and whose destroyer escorts had already departed. Pétain ordered Barré to reverse his withdrawal and remain to defend Tunisia against the Anglo-Americans.79 The two Admirals Esteva and Derrien had preferred to reinforce Bizerte. However, Barré believed that the occupation of the zone libre meant that the commencement of hostilities with the Axis was only a matter of time. It would take too long to pull his outlying garrisons into Bizerte, which, as has been seen, was considered by Juin to be an indefensible position in any case, one subject to incessant Luftwaffe attack. At this critical moment, Vichy Secretary of State for War Bridoux had authorized Barré to retreat toward the Eastern Dorsal on the pretext that he wanted to avoid any conflicts with French soldiers who might resist arriving Axis forces. “General Juin, who was commander-in-chief while avoiding behaving like one, issued suggestions,” Viard subsequently opined. On the morning of 11 November, Barré had distributed order No. 2 to evacuate troops, equipment, and matériel toward concentration zones along the line Béja–Medjez-el-Bab–Téboursouk. On the night of 11–12 November, along with the troops, 800 vehicles disguised as civilian automobiles and lorries, 147 locomotives and 2,500 rail cars, odds and ends of weaponry collected from secret arms caches, as well as reserves of petrol and coal, began to travel west.80

Thus, according to Viard, the “tragedy of Bizerte” was shaped by multiple factors, among them “uncertainty and lack of character of the leaders,” even in the wake of “the outrage of the total occupation of France.” The committee attributed this hesitation to act, when every minute counted, to “the mystique of the Marshal.” They also faulted French military culture. These military leaders were so “anxious to be commanded” that their “bureaucratic scruples obscured the bigger picture of national interest and the Honor of our Arms.”81 There was plenty of individual blame to spread around, beginning with Pétain, whose personal messages on several occasions stoked resistance to the Anglo-Americans. Darlan’s evasion of responsibility had been particularly egregious. “Admiral Darlan refused on the 10th to issue orders for Tunisia even though the Americans asked him to, and after the 10th never gave the order to oppose the Germans at El Aouina airfield … Therefore, he bears part of the blame for the occupation of this airbase by the enemy.” Juin had suspended Orders 395 and 396 to resist Axis forces in Tunisia. “Between the critical dates of 11 and 13 November, [Noguès] never gave an order to his subordinates who anxiously awaited them, and who until the night of 12 November remained a partisan of neutrality.” Had Juin and Noguès acted more forcefully, the Axis occupation of Tunisia might have been aborted on the tarmac at El Alouina. Moreau left Derrien without guidance, while Esteva was the critical influence on Derrien’s decision to surrender Bizerte to the Axis. Barré also shared responsibility, because he had failed to keep Derrien, his direct subordinate, in the picture, but instead issued contradictory orders. Derrien’s error was to have executed Vichy’s orders after 11 November, even in the knowledge that the government was held hostage by the Germans and even when these orders were vague.82

Juin’s passivity and prevarication came in for special censure by Viard. From midday on 10 November, when he resumed command, his orders were vague, even “equivocal.” Rather than demand El Aouina’s defense, he directed Barré to “resist and cover communications [with] Algeria.”83

“It seems that on 11 November, General Juin had reason to recommend the immediate initiation of hostilities against the Germans but made the mistake of not imposing his will by giving the order for a speedy attack on the airfield at El Aouina, where the Germans were not at that moment in a position to resist for long,” Viard concluded. “As a result, as the Germans continued to reinforce, this offensive tactic became less and less viable. And it seems obvious that from the moment that the enemy occupied Tunis [14 November], General Barré’s tactic of temporization imposed itself on the French command until the day it felt able to reject German requests presented in the form of an ultimatum on the night of 18–19 November, which resulted in the initiation of hostilities the following morning.”84

Viard had probably not been aware of the pre-Torch debate over how best to defend Tunisia, that had split Juin and de Lattre, and the defense plans worked out in May. One might certainly make a case for Barré’s withdrawal to preserve his force, join with the Constantine division, and shield Algeria, in keeping with a long-war strategy. However, in the commission’s view, Juin’s behavior simply fit a pattern for France’s North African command, one in which the surprise and confusion of Torch, combined with the intentional fragmentation of authority and a paralysis of initiative caused by a slavish devotion to Pétain reinforced by the quasi-mystical “Oath to the Marshal,” had pitched the French command into accountability avoidance mode. As commander in chief of French forces, Darlan’s decision simply to recuse himself on 11 November by withdrawing his order to oppose the Germans who cascaded into the zone libre and Tunisia in clear violation of the 1940 armistice agreement, placing his precious High Seas Fleet in peril, redefined the concept of command negligence, and telegraphed spinelessness to his subordinates Koeltz and Mendigal, who pressured Juin to withdraw his 11 November Order 395 to oppose the Germans in Tunisia. Viard concluded that, “on his own initiative,” Mendigal was more intent on ordering his obsolete air force in Tunisia out of harm’s way, “for military reasons for which it is difficult to find a justification,” than on actually directing it to defend Tunisia. Mendigal’s evacuation order, opposed neither by Juin nor by Barré, “had grave consequences for which they all share responsibility.” Barré initiated his retreat at a time when he might successfully have denied El Aouina to the Luftwaffe. When, on 12 November, eleven Ju 52s landed at Sidi Ahmed, and the avant garde of what would become an armada of Axis ships and boats sailed into Bizerte, “French guns … were silent,” while French tugs nudged the invaders’ ships toward their docks. If only Torch had been so trouble-free! Moreau phoned Derrien to whine about the “shambles” in Algiers, but clicked off without attempting to sort out the shambles in Tunis. Auphan mumbled pious Maréchalist homilies into the line about “the secret path of Providence that leads our country toward its destiny.” Juin asked him to send his three battalions stationed at Bizerte to Barré. Derrien refused, but it was not clear what purpose he otherwise intended for the Bizerte garrison, except to fight the Anglo-Americans or surrender them to the Germans. Noguès, the designated commander in AFN, gave no sign of having a pulse. Derrien had spent 12 November on the phone with his superiors – the Marshal, Esteva, Barré, Juin, Moreau, and Auphan – in a futile quest to divine a direction. In the end, in an act of “passive obedience,” he chose Esteva, rather than his direct superior Barré, who seemed obsessed with clearing out of town as fast as possible. To be fair, Derrien had the responsibility to defend a naval base, an arsenal and shipyard, and a small flotilla of boats, none of which was easily transportable. Yet, his passivity constituted neither a military nor a patriotic reflex. In the meantime, “the fate of Bizerte had been decided,” along with that of Derrien. “All of this concluded in the decision of 8 December (to surrender Bizerte to the Germans).”85

In Juin’s defense, his directives appeared at last to have caused l’armée d’Afrique to shed its cocoon of “neutrality.” As seen at 17:00 on 11 November, Barré had phoned Derrien to announce “Everything’s changed. We’re fighting the Axis.”86 However, rather than order Le Couteulx to police up the lightly armed German paratroops at El Aouina, Barré commanded Le Couteulx’s force to serve as his rearguard as he sought to retreat to a viable defensive position before initiating hostilities. He asked Derrien not to fire on Axis aircraft so as not to provoke reprisals. He also rejected Juin’s 12 November request that he initiate hostilities with the Germans, saying that he wanted first to regroup on better defensive positions. Barré had departed Tunis during the night of 11 November to establish his headquarters at Le Kef, 30 kilometers from the Algerian border, where the first Allied liaison officers appeared on 15 November.87 Barré subsequently justified his tactical withdrawal toward the frontier as necessary to rendezvous with Allied forces and with Welvert’s Constantine division. However, as early as September 1944, archivists noted that Barré’s command log for the period 9–18 November had been considerably expunged.88

Like that of Moreau, Darlan’s authority over French sailors also appeared tenuous. As with Laborde in Toulon, Esteva completely snubbed Darlan’s 11 November invitation to rally to the Allies. This Gallic Cancan caused Eisenhower to explode. “Confronted with these high geostrategic stakes, French preoccupations seemed derisory,” Notin concurs.89 In the view of Eisenhower, the parochialism and bickering of French military leaders, and an obsession with maintaining a fig leaf of French sovereignty over a region that was clearly shifting under their feet, were seriously impeding campaign progress. This absence of a single message from a unified, resolute leadership disoriented many French officers, and led to prevarications, contradictory orders, and desertions that made the French appear to be unreliable partners.90 As Juin’s biographer notes, the combination of the political divisions at the top of the French military with the equivocations and indecision witnessed in Algiers, where everyone in a command position sought to shirk responsibility, followed by vague orders, “invitations” and “suggestions,” issued in an obvious desire to avoid conflict with the Germans and accountability at Vichy, coalesced to give the impression to Allied commanders that Darlan’s hesitation resulted from the fact that he was not in firm control of his subordinates. Worse, in the eyes of the Allies, these French flag officers did not even seem to be good patriots. Rather, to the Americans, they appeared as poorly rehearsed actors in frantic pursuit of the play. It did not bode well for future command cooperation, or rearmament, as France slowly and apparently with great reluctance backed into the Allied camp faute de mieux.91

“Never at any moment having issued any order to attack German forces that had set foot in Tunisia and having approved the withdrawal order issued on 11 November by General Barré, [Juin] is responsible, in his capacity of commander in chief from the 10th [November], for the fact that Axis forces could penetrate Tunisia without encountering the slightest opposition,” Viard concluded. Juin’s defense was that he had been fired as commander in chief by Vichy, an assertion for which Viard could find no evidence. “Juin remained commander by right and in fact and became responsible for the posture of benign neutrality toward the Axis in Tunisia.” At no time did Barré cease to believe that Juin was his hierarchical superior. And at no time did Juin issue firm orders to attack the Germans. Had the French resisted, then Rommel, in full retreat from El Alamein, might have surrendered in Tripolitania or southern Tunisia three or four months earlier, Viard speculated.92 In fact, as Robin Leconte argues, the success of Torch resulted not from a clandestine resistance, or a defection of senior officers from Vichy, but from bottom-up pressure from the lower tier of the military hierarchy:

… pressure from the soldiers on the officers, the links of hierarchal subordination, the long hours of indecision that followed 8 November, the presence of Axis forces and the risks encountered by troops in Tunisia, all combined to tip AFN [into the Allied camp]. The decisive element proved to be the margin of maneuver allowed, despite themselves, to officers on the ground, left to their own devices in the middle of a confused hierarchy with intermittent contact.”93

Juin dodged and ducked, insisting that Darlan, not he, had been in command. But Notin concluded that, “By defending Barré, he was defending himself.”94 However, in this moment that called for clear command direction, many suspected that Juin’s command failures were the result of his pro-Vichy, if not pro-Axis, sentiments. A more generous interpretation might conclude that he was merely reverting to his original plan to preserve his forces – and to protect Algeria – by extricating French troops to the Dorsal. But this explanation, too, has serious weaknesses.95 Gaullist soldiers bestowed the derisive nickname “Juin ’40,” a moniker lifted from a marching song (“Juin ’40, la France est à terre. Présent répond les volontaires.”) about rallying to defend France in June 1940, on their commander: “It required all the blood spilled by the French in North Africa and Italy and in France to whitewash this great general of the acrimony accumulated by his hours of indecision incurred during the American invasion,” Georges Elgozy, who would fight through the Tunisian campaign, remarked bitterly.96

As the official navy history points out, on 12 November, Derrien still had two choices: defend his command against Axis encroachment, or sortie his ships and submarines, destroy anything in his arsenal that was not transportable, and, with his garrison, join Barré’s bolt for the Dorsal. Derrien’s fateful decision to remain in Bizerte was based on five factors. First, he believed that he did not have the means to defend Bizerte against Axis attack. Second, he considered that the abandonment of the harbor with its ships, arsenal, and shipyard, as well as what he and Esteva considered its strategic position in Tunisia, without a direct order was unlawful and tantamount to abandoning a perfectly seaworthy ship. A third factor is to be found in the confusion over who was in charge, contradictory orders, and lack of firm guidance from Algiers. Fourth, the news that the Americans had put Giraud in charge provoked a Gaullist-like reaction from Derrien that Washington had no right to dictate who was to lead French forces. Therefore, the “felonious general” (Giraud) had no legal claim to issue orders. This helped to open an inter-service divide, especially after Admiral Platon arrived in Tunis to enforce the message of “neutrality” toward the Axis. In these circumstances, Esteva, Derrien, and the navy commanders in Sfax opted to follow orders from Vichy, whose position at least had been consistent.97

Derrien viewed himself as a tragic figure, a victim of French command chaos in the wake of Torch. However, he took his decision neither to retreat nor to resist while fully realizing its implications. “I have seven citations and twenty-four years of service, and I’ll be the admiral who handed over Bizerte to the Germans!,” he lamented.98 During the next three days, he was given every opportunity to reverse course – after all, he conceded that the Axis would occupy Bizerte one way or another. On 12 November, Juin telephoned to persuade him to join Barré’s withdrawal, but could only reach Derrien’s chief of staff, who informed the commander in chief that Derrien would abandon Bizerte only on Noguès’ orders. In the late morning of 12 November, twenty Messerschmitts landed at Sidi Ahmed, the airfield for Tunis. Two Kriegsmarine liaison officers appeared to announce the arrival in Bizerte that afternoon of two patrol boats escorting two Italian freighters, that began to discharge troops and their cargo of artillery and tanks. On 13 November, Derrien was admonished by Barré, and ordered by Darlan to resist the arrival of Germans at Bizerte. Derrien and Esteva complained that they lacked the means to resist, although by the end of the day on 13 November only 2,000 Axis troops had arrived at Bizerte, accompanied by thirty armored vehicles and three batteries of 88 mm cannon. Another 400 to 500 Germans were at Sidi Ahmed.

“Thus, on the evening of 13 November, the military leaders in Algeria and Morocco decided to take up arms at the side of America and Great Britain to fight Germany,” concluded the Viard Commission. “But in Tunisia, General Barré, Admiral Esteva and Admiral Derrien passed up the last opportunities open to them on the 12 and possibly 13 November to resist the Germans with some chance of success by taking the offensive. General Juin did not figure out how to impose on them that option which he seemed to favor, and he continued to wait impatiently for the opening of hostilities without ordering his subordinates to take the initiative.”99

On 14 November, Giraud became overall military commander in AFN, with Juin in command of land forces. Derrien sent a staff officer to Barré carrying a letter meant for Juin, exposing his command dilemma at Bizerte. Many of his soldiers were untrained recruits. Two boatloads of German reinforcements were scheduled to arrive that day. He had no aviation. If he resisted, the Germans would take hostages in the town. And so on.

To sum up, I’m in a fix and don’t see a way out. I’m going to be the admiral who gave Bizerte to the Boches and yet, I only followed orders. My military honor is shot. I hesitate to be responsible for the massacre of hundreds of brave young men to save my reputation. I’m going to temporize: it’s the only solution. I fear also that at the first shot, I’ll see the arrival of transport planes here from Tunis or further afield. I’ll be submerged.100

The staff officer was ordered to request a written order from Juin “to throw the Axis forces into the sea.” But he would require reinforcements before he would be willing to execute such an order, which Barré refused to give him because he did not want to create a Tobruk-like redoubt in Bizerte.101 However, with British forces approaching from Bône and Axis forces lacking amphibious operations capability to land outside of a harbor, the analogy with Tobruk seemed contrived.

In the meantime, Algiers and Vichy spewed contradictory directives. Juin continued to ask the retreating Barré “when are your guns going to fire?”102 Moreau ordered the navy commanders at Tunis, Sousse and Sfax to destroy their equipment and withdraw to the west – Sousse and Sfax deferred to Tunis, while a shore battery disarmed and a minesweeper scuttled in Tunis harbor, and its captain managed to reach Barré’s line at Medjez-el-Bab. Simultaneously, the ubiquitous Auphan reminded officers of their oath of loyalty to the Marshal, and ordered Derrien to tune out Algiers.103

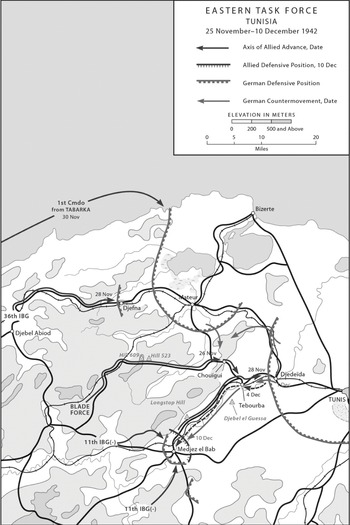

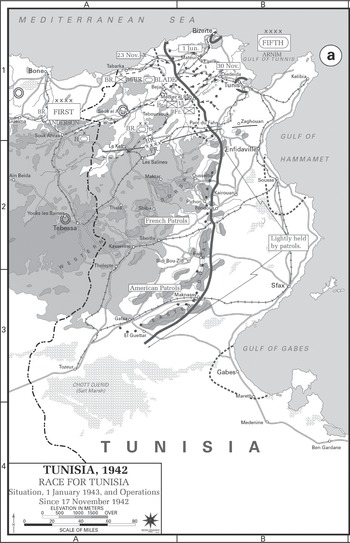

On 14 November, British troops seized Bône and its airfield. The next day, 300 men from the US 509th Parachute Regiment toppled out of 33 C-47s over the airfield at Youks-les-Bains, 20 kilometers north of Tébessa on the Tunisia–Algeria border. After a few tense moments, poorly armed French troops entrenched around the field welcomed them with open arms. This would become a major base for the US Twelfth Air Force during the Tunisia campaign. British troops pushed to within a mere 56 miles of Tunis. The number of Axis troops at Bizerte on 14 November had grown to 3,500, mostly Italians, as the Germans occupied the Tunis telephone exchange. The Viard Commission’s point was that, had the French leadership in Algiers and the command team in Tunis evinced more energy, focus, and moral courage early on to confront the Axis incursion at El Aouina and defend Bizerte and other Tunisian harbors, they might have spared the Allies a long and costly campaign.