The crisis has revealed challenges of different models for business schools. At the same time, as history shows, institutions of higher education are resilient organizations with a high adaptive capacity. Hence, responses to the crisis range from strategic continuity to disruption caused by financial impediments. It can be assumed that a new landscape of schools and programs will emerge.

In order to investigate the adaptive structures of business schools, this chapter has three objectives:

Analyze the main uncertainties of the future.

Present different scenarios of adaptive structures of business schools.

Develop models of business schools in the future.

For this purpose, the chapter draws on the extensive literature of adaptation in higher education institutions and uses learnings from recent accreditation experiences. Implications for practice, with a special emphasis on structure and strategy, conclude this chapter.

Introduction: Uncertain Futures for Business Schools

Universities are among the oldest organizations in the world and therefore have always been subject to changes in their institutional environment (Bok, Reference Bok2009; Hardy et al., Reference Hardy, Langley, Mintzberg and Rose1983; Weick, Reference Weick1976). In response to these changes, universities, like business schools, developed a resilient structural form and strong internal processes that make them successful institutions (Pinheiro and Young, Reference Pinheiro, Young, Huisman and Tight2017). Over time, scholars of organization theory and sociology have therefore characterized universities as professional bureaucracies (Mintzberg, Reference Mintzberg1989), loosely coupled systems (Weick, Reference Weick1976), or organized anarchies (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, March and Olsen1972). Major features include a differentiated structure of independent and autonomous experts who are intrinsically motivated by the quality of their work and their professional standards in research and teaching; a relatively stable but complex environment with constant student demand and secured funding; a professional support structure administering services; and a relatively lean leadership cadre with a collegial and participative governance style. These features are complemented by a set of boundary-spanning activities that guarantee a translation of external demands into internal responses (e.g., technology-transfer units, interdisciplinary research institutes). With this, the constant exchange between the inside organization and the external environment has turned universities into institutions that are rather sensitive to societal developments.

The model of business schools has also evolved over time as an elaborate system of core processes and support services. From a value-chain perspective (Peters et al., Reference Peters, Smith and Thomas2018), they provide different degree programs (bachelor, master, PhD in all forms) with the help of sophisticated support activities ranging from faculty management to the learning infrastructure. Depending on their financial viability and market position, business schools have developed different business models. In recent years, the ecosystem of business education has changed dramatically with the rise of learning technologies, increased globalization, mobility and competition, the need for short-cycle education, heightened public expectations for relevance and impact, and more (Cornuel, Reference Cornuel2007; Locke, Reference Locke, Callender, Locke and Marginson2020; Peters et al., Reference Peters, Smith and Thomas2018). Business schools – as a result – are in a state of flux.

The developments of 2020 and 2021 have added further. Universities arrived at volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity (VUCA) challenges (Korsakova, Reference Korsakova2019). VUCA challenges have been introduced to higher education markets by a combined appearance of different trends. Volatility is triggered by the fact that societal conditions are not constant (Meyer and Sporn, Reference Meyer and Sporn2018). Demographics are changing, and the demand for education is constantly changing. Uncertainty encompasses the notion of the missing predictability of institutional development and, for example, employment arrangements moving from permanent to precarious. Without a doubt, the complexity has increased for higher education. There is not one challenge that is occurring but a facet of issues that need the attention of universities and schools. Ambiguity arises for higher education in the sense of multiple contradicting demands in the form of more impact and more innovation or more quality and more diversity. VUCA does create the need for a profound rethinking of the organization of universities and business schools. In a sense, they are moved out of their comfort zones of stable environmental conditions (Bennis and O’Toole, Reference Bennis and O’Toole2005).

Adding to the already-existing dynamic environment came the COVID-19 crisis. The consequences have included issues like online teaching competence; safety for students and faculty; research disruption as a result of the lack of opportunity to travel and network; and administrative threats caused by the rising costs of response, for example, new infrastructure needs, personnel challenges caused by the home office, or the impact of the pandemic on student learning and outcomes, thus influencing their qualifications for the job market (Baker, Reference Baker2021; Marinoni et al., Reference Marinoni, van’t Land and Jensen2020).

All these changes can trigger financial restructuring and reorganization. Globally, schools are facing changes in student demand for educational programs. Those programs creating revenue for business schools are especially in jeopardy of financial restructuring. For example, some Australian and US schools have been downsizing their program offerings. Strategies have been revised as to the portfolio of program offerings, and mergings of different program types have been the result. The faculty has been restructured in the process as well, in the sense of replacing full-time faculty with colleagues who work on a part-time and flexible basis. Altogether, the COVID-19 crisis led to financial restructuring that scrutinized existing strategies and reformulated them in order to face a much more uncertain future (Lockett, Reference Lockett2020).

In this chapter, business schools and their adaptive capacity are the major foci. Along those lines, many business schools around the globe have chosen accreditation as a way to have a visible and sustainable tool at hand for quality management and continuous improvement. The European Foundation for Management Development (EFMD) is the major provider of formative evaluation schemes and strongly emphasizes – among other things – diversity, internationalization, and impact. Major accreditation systems include institutional assessment (under the name EFMD Quality Improvement System [EQUIS]) and program assessment (under the name EFMD Accredited). Hence, and because this volume is dedicated to 50 years of EFMD, this chapter also looks at EFMD accreditation when analyzing business schools.

The Role of and Impact on EFMD Accreditation

Accreditation at EFMD over the last 25 years has developed into a very successful system of assuring quality, on the one hand, and producing a visible global brand of excellently performing business schools, on the other hand. Today, there are some 200 EQUIS-accredited schools and some 130 EFMD-accredited business programs. Standards and criteria of accreditation encompass institutional factors like strategy, resources, faculty, networks with the world of practice, internationalization, research, and last but not least, students and programs. A peer-review system of colleagues from accredited institutions and representatives of corporates and nonprofit organizations regularly evaluates all these areas. Through the decades-long experience, a clear understanding of the different models of business schools developed within EFMD. Respect for diversity regarding different forms and market positioning has been a key element in this development and reinforces the understanding of business schools as a driver for societal change (Cornuel, Reference Cornuel2005; Thomas and Cornuel, Reference Thomas and Cornuel2012).

Now, through the COVID-19 crisis, the accreditation system has become challenged as well. One aspect involves the actual delivery of the accreditation, which had to move online. According to the schools involved, this has worked rather well. The other aspect is certain standards used in accreditation that have turned into areas of major concern: digitalization; internationalization; and ethics, responsibility, and sustainability (ERS).

Digitalization is the most obvious area of change in recent months. From one day to the other, business schools worldwide had to move to virtual classrooms and offices. Within days, universities and business schools reorganized teaching and research and worked with administration remotely. In the assessment during an accreditation visit, digital venues played a bigger role and helped those that were able to build their activities on an already-existing digitalization strategy. Others were pressed to respond quickly without much preparation.

Internationalization is another standard of EFMD accreditation featuring prominently. The pandemic crisis put all efforts of mobility on hold. Schools have been in the process of responding with virtual internationalization, internationalization without mobility, online mixed teams, or virtual visiting professorships. Again, the business models of many accredited business schools have been challenged.

ERS is a third area where accreditation standards need to be developed further. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, business schools have paid more attention to the increased inequality of students and their access to online learning. Sustainable measures of resource use have become more widely discussed (e.g., travel regulations), and the integration of stakeholder diversity has increased in prominence (de Wit and Altbach, Reference de Wit and Altbach2021).

Theory of Adaptive University Structures

The crisis has revealed the limits of university business models and available resources. At the same time, history shows that universities and business schools are resilient institutions with a high adaptive capacity. Hence, responses to the pandemic are expected to range from strategic continuity to disruption caused by financial impediments. Building on existing theories of adaptive university structures (Sporn, Reference Sporn1999) and entrepreneurial universities (Clark, Reference Clark1998), this chapter presents scenarios and possible business models of the future.

The question of disruption or continuity of strategy uses the following definition:

In an organisational context, business continuity management (BCM) has evolved into a process that identifies an organisation’s exposure to internal and external threats and synthesises hard and soft assets to provide effective prevention and recovery. Essential to the success of BCM is a thorough understanding of the wide range of threats (internal and external) and a recognition that an effective response will be determined by employees’ behaviour during the business recovery process.

Although strategic continuity is important, business schools and universities need to be analyzed regarding their adaptive capacity. The notion of adaptation to environmental challenges has been debated in higher education research since the 1990s. Under the topic of entrepreneurial university (Clark, Reference Clark1998) or responsive university (Tierney, Reference Tierney1998), research focused on describing the mechanisms of adaptation and the role of organizational aspects prevailed. Up until today – with the ever-changing turbulent environment for higher education institutions – these theories are of great importance.

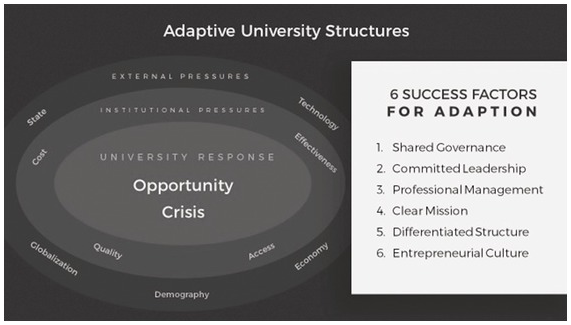

The work on adaptive university structures (Sporn, Reference Sporn1999) seems especially fitting for the analysis in this chapter. The model proposes six factors of influence (see Figure 9.1): shared governance, committed leadership, professional management, clear mission, differentiated structure, and entrepreneurial culture. The interplay of these six forces shapes the ability of business schools to respond to their environment – an environment that is defined as a crisis or opportunity by the institutions. In this sense, the model also assumes an open-systems and institutional approach to university adaptation (DiMaggio and Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983).

Regarding the external environment, business schools and universities are viewed as embedded in an institutional context to which they have to respond. Clark has coined this as the demand–response balance – a condition where the university is aligned with the expectations of external stakeholders. For the sake of adaptive structures, it is important to note that the sense of crisis or opportunity is a necessary precondition for higher education institutions to respond.

A very important facet of adaptation is shared governance. Business schools, like universities, are bottom-heavy organizations with a dominant role of the experts (i.e., the professors). This group requests a key position in the functioning of the institution. Their contribution to teaching and research is the building block for the core value of business schools. The notion of shared governance is then interpreted as the involvement of the experts in all decisions in order to facilitate faculty buy-in and motivation. Basically, shared governance helps leaders to build their work on the support of the key players in the organization.

Following from that is the importance of committed leadership. In times of organizational transition, leaders are becoming the key drivers for change. Their understanding of the institutional environment can help to translate both threats and opportunities into strategies for the future. Leaders help to motivate internally in order to make necessary changes more transparent. At the same time, committed leaders are able to develop a vision that is shared by the university community. Thus, the interplay between faculty interest and leadership dedication can form an important alliance for successful adaptation.

The rise of professional management of business schools has contributed to the success of institutional adaptation. Over the last few decades, university administration has moved from a bureaucratic to a professionalized organization (Musselin, Reference Musselin, Krücken, Kosmützky and Torka2007). With this comes the evolution of a new class in schools and universities – the “third-space professionals” (Whitchurch, Reference Whitchurch2012). They are well educated in the field of their work (e.g., quality management, marketing, student services) and constitute a separate new group inside business schools – next to leadership, faculty members, and administration. Their work is characterized as service oriented, professional, and knowledge driven. Through their boundary-spanning capacity (e.g., entrepreneurship or technology-transfer centers), they are able to develop adequate responses to external pressures.

A clear mission has proven important for successful adaptation and change. Shared decision-making practices, committed leaders, and professional managers need to base their work on a clear mission and set of goals that are shared by the academic community and that combine past developments with future perspectives. A common understanding of the external challenges is a key feature of successful adaptive university structures. This clear mission is embedded in a vision and a strategy that help the institution to move forward.

A differentiated structure provides the higher education institution with different ways to respond to external needs. A business school could, for example, develop competence fields with different functions and services (undergraduate college, graduate school, entrepreneurship center). These differentiated units are relatively autonomous in terms of design and adjustments of their offerings and are at the same time accountable to central leadership.

The entrepreneurial culture is the remaining building block of adaptive structures. This refers to a set of institutional norms and values emphasizing opportunity-driven and solution-oriented behavior. Burton Clark, the famous higher education researcher, once talked about “joint institutional volition” (Clark, Reference Clark2004) as the major driver for organizational transformation in institutions of higher education. This implicit openness for innovation paired with a common understanding of the future can help the institution to move through a disruptive period. The coherence makes change and adaptation successful.

Adding to the notion of adaptive structures is the importance of a process view. Clark (Reference Clark2004) presented three dynamics through which sustained change happens. First, reinforcing interaction is a key element in the process. The institution needs to provide enough opportunities to interact and exchange views on the issues involved. Decisions are in line with the envisioned future and enhance a change-oriented culture. Second, a sense of perpetual momentum is needed in order to support the – what he called – self-reliant university. Ongoing adjustments, negotiations, interactions, environmental scanning, and so forth should be in place to maintain organizational dynamics and agility. Third, the institution needs to develop an ambitious collegial volition. Clark makes a strong argument that only an “ambitious volition helps propel the institution forward to a transformed character”; he goes on to say that “inertia in traditional universities has many rationales, beginning with the avoidance of hard choices” (Clark, Reference Clark2004, p. 94).

In order to discuss strategic continuity or disruption in the sense of adaptive structures of business schools further, it is necessary to look at the notion of strategic development versus disruption. For this, an example from the area of accreditation can help to illustrate how schools have responded to the challenge of maintaining a sense of quality improvement in times of severe societal crisis caused by the pandemic.

Back to the Practice of Accredited Business Schools: An Example

As was explained earlier in this chapter, business school accreditation is based on certain standards and criteria (see www.efmdglobal.org/). Among them are digitalization, internationalization, and ERS embedded in the main areas of strategy, teaching and research, and faculty and students, as well as connections to the world of practice. In all areas, EFMD defined a clear understanding of the meaning and implementation choices. At the same time, the COVID-19 crisis has challenged the accreditation system, and certain questions emerged that need to be addressed in order for the system to be fit for future quality-assurance exercises.

One recent example of a global business school – the Nottingham Business School China (NUBS China) – deliberating on the move from crisis management triggered by the pandemic to opportunities is informative. After a period of major disruption and immediate response to the COVID outbreak, the business school looked at the opportunities ahead and developed five opportunities for the future (Lockett, Reference Lockett2020) that resonate well with other accreditation experiences:

Opportunity 1: Extending the use of digital learning

Opportunity 2: Innovation in assessment

Opportunity 3: Research and external engagement

Opportunity 4: Reviewing the use of resources

Opportunity 5: Challenging internal bureaucratic processes

As this list shows, digitalization can create an opportunity for business schools. New ways of learning within existing programs or new offers will evolve. This will include hybrid, virtual, or blended formats as well as flipped classrooms or cross-campus, cross-institution, and cross-country collaborations.

Assessment can be redesigned as well, in the sense of working more closely with students on their educational journey. Feedback can be provided online or through a link between faculty and students enhanced through technology.

Research and engagement require time and dedication. As the example shows, time can become available through the confinements and home-office arrangements. The future could possibly bring more opportunities to publish and to work on relevant topics in that way, creating an impact on society and the academic community.

The use of resources is also affected throughout the crisis. Resource needs that are decreasing in some areas (e.g., travel) can be used for investment in other, new areas (e.g., online delivery) in order to meet market demands.

As described earlier, decision making at business schools can be cumbersome and bureaucratic. The pandemic crisis showed new ways of working together in order to develop solutions. This could lead the way for more efficient and effective ways of management.

This example demonstrates the power of the pandemic crisis and its effects on the way business schools are run. In order to take this one step further, scenarios are presented that show different types of institutional responses.

Scenarios of Adaptive Structures Responding to Crisis

Scenarios are often used to give a plausible description of a possible “future reality,” including some deliberations about the steps that lead to the future state and possible actions taken (Dean, Reference Dean2019). Based on past research (Pinheiro and Young, Reference Pinheiro, Young, Huisman and Tight2017) and experiences during the last year, three responses to the pandemic crisis are suggested: resilient schools, reengineered schools, and reinvented schools. In this section, the major characteristics and conceptions of the most affected accreditation standards (international, digital, ERS) and the response patterns (disruption or continuity) are presented before moving to the description of the varying adaptive structures and business models of these types.

Type 1: The Resilient School

Resilience refers to the notion that lies at the heart of business schools and universities since their foundation. It is the ability to be prepared, adaptable, and responsive to an external demand – be it a crisis or an opportunity. The literature (Pinheiro and Young, Reference Pinheiro, Young, Huisman and Tight2017; Sporn, Reference Sporn1999) draws a picture of flat, expert-driven institutions that are firmly embedded in their institutional environment (Olsen, Reference Olsen, Maassen and Olsen2007; Pettigrew et al., Reference Pettigrew, Cornuel and Hommel2014). Collegial leadership and a shared understanding of the functioning of the business school dominate decision making and action. A stable environment with secured funding and constant student demand is a prerequisite in this constellation. The power of the experts (professors of all levels) is based on a high degree of autonomy, the quality of the expertise, and individualized connections to the external environment. Resilient schools will mostly be found in public systems with a long tradition of higher education and a pledge for the “traditional model” of the university (Musselin, Reference Musselin, Krücken, Kosmützky and Torka2007).

Regarding the consequences for internationalization, the resilient school has invested sufficiently in the development of a functioning digital infrastructure, adequate teacher training, enhanced student services, and robust information technology (IT) support. Internationalization has been transformed in the sense of providing online opportunities for exchange through, for example, online intercultural learning teams and virtual visiting professors. ERS has been mostly concerned with acting responsibly in the manner of addressing rising inequalities and the widening digital gap; for example, according to a recent survey, 40 percent of students worldwide lack online access (Martin and Furiv, Reference Martin and Furiv2020).

Resilient business schools are apt for strategic continuity rather than disruption. Although the sudden crisis caused by the pandemic hit these business schools hard, they were able to respond sufficiently to address the most pressing issues in teaching and research. Further plans will most likely include “to move back to the classroom” and suggest the continued practice of existing strategies.

Type 2: The Reengineered School

On the contrary, reengineered business schools are more market dependent and driven by student demand. Hence, their functioning is dominated by a “business logic” where tuition-fee payments and a potential drop in enrollment numbers are major threats. The school leadership needs to respond with potential layoffs of faculty, closure of programs, or a combined set of measures that will “reengineer” the school in the sense of making it financially viable.

For reengineered schools, the changing pattern of internationalization represents a challenge caused by a drop in student mobility. Investments in this area will include solutions to satisfy demand through online offerings (e.g., exchange without mobility). Digitalization becomes the decisive tool in this scenario and will be used in all aspects of teaching and learning. The third area is ERS with respect to, for example, working students who lost their job and who will not be able to finish their degree programs. It is in the interest of those business schools to find a way to support those students and bring them back on campus (see global survey results in Marinoni et al. [Reference Marinoni, van’t Land and Jensen2020]).

Strategic disruption features prominently at the reengineered business school. The leadership often exercises crisis management in order to reassess and review existing strategies, stressing program efficiency and cost management. Examples are business schools in Australia or the United States where faculty restructuring and program redesign have led to a new portfolio and structure.

Type 3: The Reinvented School

A third scenario describes a school that has had a pathway of innovation and is ready to respond to an unexpected crisis. These innovator business schools can demonstrate a history of innovation and redesign. Reinvented business schools are stakeholder centered (mostly students, employers, and public officials). Their teaching model is constantly adapting and has been using models like the flipped classroom and transformative approaches to learning. Outreach is global, and faculty is part of a community of “entrepreneurs.” Connections with practice are key components to guarantee impact. Technology plays a large part in reinvented business schools as IT is used creatively to facilitate student and faculty work.

The reinvented business school is familiar with internationalization, digitalization, and questions of an ESR nature. The global outreach of these institutions has created a culture and structure that are built on the values of international mobility and exchange, with the objective of offering the best opportunities for graduates. Virtual and up-to-date technologies are part of their entrepreneurial tradition (Taylor, Reference Taylor2012). Innovation in the reinvented business school resembles the constant exploration of new opportunities and implementing them for the good of the institution. The impact of the reinvented school has included areas, such as, for example, ethics training, responsibility regarding health issues, or new sustainable infrastructure.

The reinvented business school is able to define the pandemic as a disruption that will create a revised strategy based on the sense of opportunity. Leadership has a strong entrepreneurial identity, the academic community believes in the value of exploration and experimentation, and the infrastructure is agile enough to adapt to new circumstances. This open mindset to newness paired with a strong foundation in institutional values and culture helps the business school to overcome the obstacle of a crisis in a way that will further develop and sharpen the strategic thrust.

The three scenarios are suggested categorizations of schools responding to the COVID-19 crisis based on certain assumptions (e.g., volatile environment, changed demand). Other types and different forms are certainly conceivable, depending on the institutional reality of business schools. For this chapter, these different types are taken one step further, with the goal of presenting models of business schools. This can sharpen the understanding of the diversity of business schools and their manner of responding to environmental changes.

Models of Business Schools in the Future

The modeling of business schools includes important aspects of organizational functioning (Pinheiro and Young, Reference Pinheiro, Young, Huisman and Tight2017): external orientation, core values, use of resources, internal dynamics of management and leadership, the locus of control, the modus operandi as the way to respond, and the positional objective or aspiration (see Table 9.1). When combined with the different types described in the previous section, three models of the business school emerge: the resilient, the strategic, and the innovative. These models of business schools will be combined with the elements of adaptive structures in order to provide a full account of their organizational characteristics (Sporn, Reference Sporn1999, Reference Sporn, João Rosa, Magalhães, Veiga and Teixeira2018).

Table 9.1. Models of Business Schools (based on Pinheiro and Young, Reference Pinheiro, Young, Huisman and Tight2017)

| Resilient | Strategic | Innovative | |

|---|---|---|---|

| External orientation | Cherish complexity | Control complexity | Use complexity |

| Core value | Robustness | Efficiency | Change |

| Resources | Allow slack | Maximize | Invest |

| Internal dynamics | Support variety | Rationalize | Capitalize |

| Locus of control | Networks: loose coupling | Hierarchy: tight coupling | Teams: independent actors |

| Modus operandi | Exploration | Exploitation | Innovation |

| Positional objective | Thriving – adapting to niche | Winning – being the best in the field | Creating – offering new solutions |

The Resilient Model of the Business School

The model of resilient business schools is built on the institutional tradition and past successes enabling a robust structure. Schools’ organization shows an external orientation that appreciates complexity in a stable and predictable environment; that is, strategies make use of the complex nature of its diverse markets. Slack resources help to support all elements of a network of loosely coupled units (e.g., institutes, centers, individual professors and department chairs). The school explores opportunities as they emerge and adapts to niches in order to thrive.

Applying the approach of adaptive structures (Sporn, Reference Sporn1999), the resilient school will most likely react to a crisis with the understanding that it needs to be addressed and overcome. Internal functioning is very much dominated by shared governance involving academic stakeholders. Leadership and administration have a complementary role to play in this process. The focus is on transactional aspects with which the different involved parties agree on a strategic orientation. The structure is differentiated and allows the organization to respond to diverging environmental demands. An entrepreneurial culture is not dominant in this model but might exist in some of the differentiated parts. This model is most likely to be found in systems with public funding with less competition, such as those in some European countries.

The Strategic Model of the Business School

The strategic model of business schools features a hierarchical structure and tight coupling of the different elements; that is, leadership and management can work based on the notion of efficiency and rationalization. This model resembles an enterprise approach to schools’ management. Environmental complexity needs to be controlled, and resources are scarce. Allocation is driven by the goal of developing a competitive advantage. A market position is exploited to the extent that the school is highly competitive based on its core competencies.

The adaptive structures of strategic business schools have a stronger commitment from leadership to successful change activities. Governance is geared towards professional values. Professional management needs to be in place in order to guarantee the success of the programs. Entrepreneurial responses mainly encompass exploiting programs for economic value. The structure is focused on hierarchical arrangements. The strategic model of business schools often includes redesign and reengineering as a consequence of a crisis, as examples from more competition-oriented systems in the UK and the United States demonstrate.

The Innovative Model of the Business School

Innovative business schools are institutions with a strong entrepreneurial identity and an emphasis on change. The value of constantly developing existing programs further and designing up-to-date new offerings lies at the center. The organization is built around capitalizing on teams of creative actors and investing resources for innovation. Innovative business schools use the results of environmental complexity as opportunities. They are able and agile enough to respond quickly and successfully.

Regarding adaptive structures, innovative business schools combine the different areas for success. Their shared governance involves the relevant stakeholders to the extent necessary to secure the implementation of new initiatives. Committed leadership is a key building block – inspirational and visionary leaders help the business school to move forward. A professional infrastructure and staff help to develop feasible and sustainable solutions in a team-oriented fashion. The clear mission and vision act as the glue uniting the different groups and stakeholders behind a common idea and model for the future – based on a strong entrepreneurial culture. Differentiation is relevant in the sense that different actors are brought together to form networks and find creative ways to adapt. Innovative business schools can be found in all systems and often emerge from a financially independent position, with a history of change and widespread support for innovation of the academic community.

Concluding Thoughts

This chapter set out to analyze the adaptive capacity of business schools in the era of the COVID-19 crisis. For this, an account of the institutional environment was provided, followed by a description of possible theoretical foundations of adaptive structures. As a result, the chapter suggests three models of business schools based on their context, tradition, and structural arrangement: the resilient, the strategic, and the innovative. This analysis is not all-embracing or universal; depending on the viewpoint, different models could be developed. To conclude, areas for consideration by practitioners and researchers are presented.

First, business schools are complex organizations with the challenge of finding the right balance between resilience and change. The question arises as to how business schools can stay agile and resilient at the same time, given the complex internal environment of diverse stakeholders and their demands. These schools will most probably look for strategic continuity by following an agreed-upon plan and making adjustments where needed.

Second, business schools have the chance to develop the notion of innovation through crisis. In recent EFMD meetings of deans and directors, the pandemic was described as an opportunity for change. With this transformational view of leadership, business schools are able to capitalize on the ability to adapt. Schools can also become more innovative through a visionary strategy for the benefit of the institution.

Third, the question of strategic continuity or disruption of business schools is determined by multiple factors. The context and location play a role, as does the role of leaders, the faculty, and the students. For the analysis and practice, a key starting point would be to fully grasp the type and model of the business school and build the strategy accordingly.

EFMD, with its global presence, has a responsibility and a role to play in this situation. The continued belief in an open system characterized by diversity and inclusion while securing a high level of quality will provide business schools with the opportunity to learn from each other’s practices. By understanding their specific contexts, benchmarking and mutual learning can be facilitated. With this, EFMD can help business schools to maintain their legitimacy and social impact in society.