Introduction

The current COVID-19 crisis has triggered unprecedented upheaval on a global scale. From a strictly public health point of view, however, humanity has proven itself capable of joining forces and transcending political boundaries.

The Crisis Is Transforming Management and Leadership

Coming hot on the heels of our bicentenary year, the pandemic has had a severe impact on the work of École Supérieure de Commerce de Paris (ESCP) across all of our European campuses, affecting our faculty members and international students alike. The crisis has confounded forecasters completely and now raises serious questions as to the responsibilities of managers and the meaning attached to their work.

For the heads of higher education institutions, this issue takes on a dual significance. First and foremost, there is the question of the meaning, usefulness, value, and purpose of the knowledge we produce for society in general. Then, of course, there is the dissemination of actionable knowledge for the benefit of our stakeholders: students, alumni, businesses, organizations, and public administrations.

As deans of business schools, our duty reaches above and beyond the production and dissemination of knowledge, methods, and managerial practices. It also consists of guiding and responding to events and overseeing the constant adaptation of individuals within structured social systems.

Finally, as an academic specializing in leadership, I find myself wondering how business schools can best prepare the business leaders of the future for the challenges they will be facing.

I. Rethinking Leadership after the Experience of Multiple Lockdowns

1. ESCP as a Pan-European Business School

Our school was founded in 1819 and has rarely closed, even during the darkest periods of the three wars of 1870, 1914, and 1939. ESCP has 7,300 students in initial training, in programs ranging from bachelor to doctorate, and 5,000 managers in executive education (ExecEd). The school is unique in that it boasts campuses in six European countries, with national recognition as a Grande Ecole in France, as a university in Germany by the Berlin Senate, as a university in Italy, as a university in Spain, and as a British higher education institution. All of these campuses are managed and coordinated by a team that is united around European values and the ESCP culture: Excellence, Singularity, Creativity & Pluralism.

The pandemic has hit ESCP in several waves:

The first phase came in February–March 2020, when our Turin campus was the first to be hit. The resilience and relevance demonstrated by the Italian entity in its reactions provided some good practices for the benefit of the school as a whole, as the Madrid, Warsaw, Berlin, and Paris campuses were then confronted in turn with the challenges of managing a school in lockdown. Finally, the London campus was the last to close. During this initial lockdown phase, the school capitalized on its previous experience of coordinating multiple campuses, and our faculty members built on their experience of using digital tools. There was a reconceptualization of the student recruitment process for the start of the 2020–21 academic year, with written tests but no oral interviews so as to place all candidates on an equal footing, whatever inequalities there might be in their access to good-quality digital facilities. We must salute the continued research efforts by the faculty who leaped into action and succeeded in producing Managing a Post-Covid19 Era (Bunkanwanicha et al., Reference Bunkanwanicha, Coeurderoy and Ben Slimaneecsp2020), a collection of impact papers enabling students, employers and companies, and governments to better understand the global pandemic and its multifaceted implications for our societies.

The second phase came with the start of the new school year, from September 2020 through to the end of the year. After a start to the new school year with the students present in person, in compliance with the health regulations, a second partial lockdown was put in place with the introduction of a curfew. Because the various governments did not all make this decision at the same time, the organization of student mobility was disrupted, but it did provide an opportunity to put the new teaching facilities to use. At ESCP, we opened the Phygital (contraction of physical and digital) Factory, a place where our faculty can record their teaching modules easily. At the same time, increasing proportions of remote courses were organized, both synchronously and asynchronously. As an indication, whereas 3,070 courses were delivered online during the first lockdown, the second lockdown saw a significant increase to 4,200 online courses, representing more than 80,000 hours of teaching. ESCP has now entered a period of “Mobility and Motility” where students keep enjoying the experience of physical mobility and the experience of learning in just moving intellectually.

The third phase began in January 2021, with the various states making different decisions regarding the physical presence of students in higher education institutions. The latter is currently in a hybrid phase, with the possibility for students to return, subject to a maximum of 20 percent of the students physically present. However, the schools have now mastered the digital tools for the courses and services they offer, which is a big difference compared to the first lockdown. In March 2020, the schools were unable to organize the recruitment orals. This year, however, they will take place digitally, which shows the confidence higher education institutions now feel in their adaptation to digital technology. However, there is a feeling of weariness at present – weariness with the digital world, as well as with the lack of social contacts for our young people at a very important time in their student lives. It is this psychological aspect that led President Macron to keep the schools open. This third phase has also brought an awareness that ExecEd will no longer concern the same services or same profiles, and we will come back to that in detail in Part II. Similarly, in the governance of higher education institutions, meetings are taking place with a high level of quality, especially board meetings, and the same goes for the governance of the EFMD board and the EFMD deans conference, which I was able to attend at the beginning of February 2021. The level of satisfaction of the deans was very high, despite the distance and lack of real contact.

2. Responding to the Pandemic: Our Eight Key Takeaways

In short, the school’s internal stakeholders – students, faculty, administrative staff – have been strongly mobilized, and from our vantage point today, at the beginning of 2021, we can outline eight practical lessons that will inevitably change the way a Business School is run, in a lasting manner.

1. Taking the 20-40 digital turn today: ESCP has become convinced that neither students nor management research has anything to gain from the uberization of the business school model. What is needed is more widespread use of the forms of blended learning that were already emerging before the pandemic. We have also chosen to give the teaching staff a great deal of pedagogical flexibility. Looking to 2040, it has been decided to have a minimum of 20 percent digital and 40 percent in-class teaching for all courses. This will allow some teachers to favor 80 percent of class time with their students present in person and 20 percent remote, for example, or others might prefer to divide their teaching into 40 percent face-to-face content and 60 percent digital. This will make it possible to adapt the pedagogy of management disciplines. The challenge now is to produce digital modules that can be integrated into a symbiotic face-to-face architecture.

2. Delivering premium asynchronous courses: The crisis has revealed the need to provide students with courses of the highest standard wherever they are in the world. This has led many business schools to produce prerecorded (asynchronous) modules to take account of the realities of time-zone differences. Pedagogically, the production of an asynchronous module is much more demanding than filming a synchronous course livened up by questions from students. The asynchronous module must captivate the learner from beginning to end by means of a teaching sequence that is punctuated with videos of illustrations and quizzes for midterm evaluations, along with impeccable presentation materials.

3. Rethinking ExecEd: As will be discussed in Part II of this chapter, the changes underway in ExecEd are drastic. Corporate expectations will be radically different once the pandemic issues are resolved. The share of digital methods will increase, whereas the duration of seminars will be shortened considerably. Business school professors will be invited as expert witnesses, rather than as the half-day facilitators they were in the past, when they would give presentations with (albeit sophisticated) overhead transparencies and pass from one subgroup room to another to encourage executives to solve case studies. If the business school professor previously took the lead over the group of learners, it will now be the university or a pedagogical coordinator it has appointed who will lead the group of business school professors invited to the company’s training.

4. Striking a new equilibrium between research and teaching: The rise of digital technology will require business school deans to speed up the production of educational capsules for students and continuing education managers in a short space of time. This will have consequences for business school rankings, where the quality of an institution will be measured in terms of research, student selectivity, the pedagogical quality of teachers, and the size of the business school’s digital offering. Digital technology will not replace research; it will become an additional criterion for evaluation.

5. Launching a massive real estate plan despite the uncertainties: The question of business school real estate is being raised once again as we move from managing real estate to digital estate. The need will shift from managing classrooms, floor space, and teacher researchers’ offices to questions of ergonomics, furniture, and equipment adapted to digital technologies and teaching resource storage capacity in terabytes.

6. Not resting on the success of our flagship programs: Digitization is reshuffling the cards when it comes to educational portfolios, with the expected flowering of specialized and regularly updated digital certificates. The accumulation and combination of these certificates can lead to lifelong diplomas.

7. Anticipating what Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft (GAFAM) and educational technology (EdTech) will be able to offer tomorrow: This will involve establishing a position for the major digital and EdTech companies in higher education. They have a technological advantage in the global spectrum and have the financial muscle to acquire renowned universities, but they also run the risk of being rejected by the governments that serve as regulators of higher education. In any case, business schools will not be able to avoid taking this potential new player, partner, and predator into account.

8. Positioning higher education institutions in relation to EdTech: It is striking that there is much more talk about the transformation and innovation of EdTech companies than about the transformation of business schools. EdTech companies tended to be seen as subcontractors for the business schools before the pandemic, and increasing digitalization should not reverse that relationship. It would be a bit like science being hosted by Wikipedia.

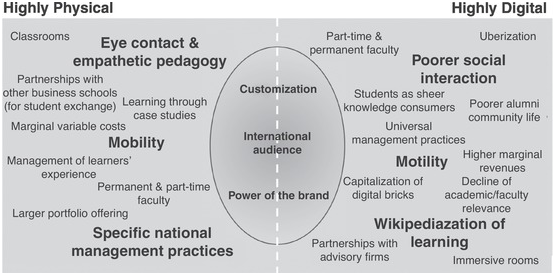

Business schools must therefore skillfully weigh up the advantages and risks when they engage in a pedagogical mix that combines physical and digital. Figure 14.1 shows the main elements to be taken into account, bearing in mind that there is no absolute “one best way” and that a balanced mix needs to be constructed according to parameters such as the duration of the training, the level of the participants, the size of the group, and the variety of the international audience.

Figure 14.1 Finding the right pedagogical mix.

3. Executive Profiles and Competencies

In a recently published work, Rebecca Henderson (Reference Henderson2020) of Harvard Business School explains that managers now have no choice but to totally reinvent capitalism. In La Prouesse Française (French Prowess), published in 2017, I insisted on the defining characteristics of the French style of management, highlighting its strengths and the weaknesses in need of a rethink (Suleiman et al., Reference Suleiman, Bournois and Jaïdi2017).

The COVID-19 crisis has thrust this debate front and center. Attentiveness to well-being at work, respect for individuality within groups, and a commitment to the greater good are all key pillars of European humanist culture. These values have come rapidly to the fore through the decisive measures taken to protect citizens, respect individual liberties, and prepare for the economic recovery of the European Union.

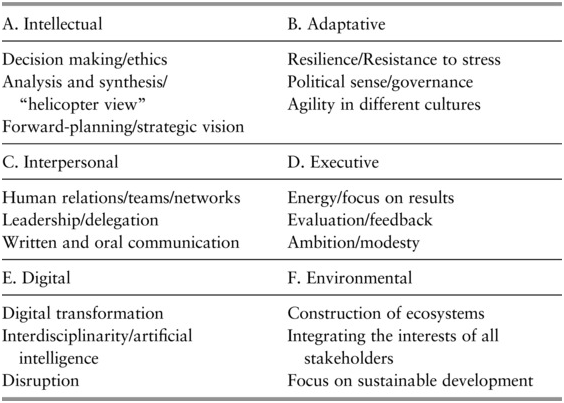

Leaders in both the public and private sectors are acutely aware of the impact of this enforced pause, this moment of reflection on a global scale, and must learn the lessons of the current crisis. Going forward, the six major dimensions identified in Table 14.1 will be of primary importance by 2030.

Table 14.1. Qualities and Aptitudes Required of Future Leaders

| A. Intellectual | B. Adaptative |

|---|---|

Decision making/ethics Analysis and synthesis/“helicopter view” Forward-planning/strategic vision | Resilience/Resistance to stress Political sense/governance Agility in different cultures |

| C. Interpersonal | D. Executive |

|---|---|

Human relations/teams/networks Leadership/delegation Written and oral communication | Energy/focus on results Evaluation/feedback Ambition/modesty |

| E. Digital | F. Environmental |

|---|---|

Digital transformation Interdisciplinarity/artificial intelligence Disruption | Construction of ecosystems Integrating the interests of all stakeholders Focus on sustainable development |

The ESCP Community Rises to the Occasion Once Again

I could not be more impressed by, or proud of, the monumental work done by the ESCP faculty – and all in record time! Students, alumni, and decision makers will find herein a rich profusion of ideas, debates, and pragmatic proposals for the future of the post-2020 economy.

What variety and depth of talent we have in the academic community of our business school! All of our European campuses, all of the disciplines of management studies, and all of the principal dimensions of decision making are represented here. Six overarching themes emerge, corresponding to the major challenges awaiting managers: the digital transformation (particularly at work); the limits of individualism and the rise of new forms of collective action; inclusive management/leadership; the resilience of businesses in times of crisis; uncertainty and the need for change (or stability) in the financial markets and the markets for goods and services; and finally, the challenges this crisis raises for higher education.

II. Business Schools Must Engage in Strategic Partnerships

During the past decade, large companies have made profound changes to the way they design programs within their corporate universities. Overall, they have shortened the duration of seminars for senior executives and managers, professionalized their program managers, internationalized the sourcing of their speakers, increased the variety of teaching tools, opened up the themes to include individual development and codevelopment, introduced metrics to systematically evaluate the added value perceived by participants, and so on.

This has led to the creation of much more varied ecosystems than in the past. The main idea behind this contribution is to show that the Grandes Écoles no longer have to do everything in-house, from collecting the company’s needs to providing certificates once the seminar is over, including the implementation of face-to-face or distance learning sequences. The trend that is emerging for the new decade will consist of business schools creating, devising, and professionalizing partnerships with other business schools, with consortia of leading companies in certain sectors of activity, and most certainly, with the leading professional service firms (PSFs), the consultancy firms for which education is at the heart of their strategy.

The ExecEd environment will be different tomorrow, driven by new quality expectations, a new relationship to the workspace, and new organizational and time-management habits. New types of partnerships will flourish in the coming decade. They will deliver diplomas and certificates from largely digital offerings, and the highest-profile and most reputable of them will succeed in attracting corporate leaders to take on a doctoral thesis based largely on their professional expertise.

1. Digitalization and Customization as Partners

Among the major developments of the past decade, there is one absolute certainty: digitalization is going hand in hand with the customization of ExecEd needs. The interviews I have conducted with many directors of corporate universities underline the trend toward microlearning, that is, highly specialized, carefully customized modules. At first glance, this may seem paradoxical if we think that digitalization boils down to automation, the accumulation of teaching resources, and increasing storage of knowledge (knowledge accumulation). In fact, if we know how to identify the needs of each learner in detail (senior executives and managers), if we know their previous experience, their personal approach to the digital world, and the time they have available for their personal training, then digitalization will make it possible to (1) provide them with specific resources, (2) guide them in their choice of modules, (3) provide them with numerous self-assessments, and (4) provide them with points of reference in relation to other managers in their category, all while respecting their rate of progress in conjunction with their direct bosses and line management. To do this, three main conditions must be met:

1. The business school must have a vast pool of teaching resources at its disposal.

2. The business school must have an information system linked to its teaching; this does not exist in many cases because the information systems mainly manage the administrative life of the business school, leaving pedagogical matters in the hands of teachers. If the business school succeeds in establishing the connection between pedagogy and information system, this opens up numerous possibilities for tracing individual paths and maintaining the motivation of participants to go further.

3. Because of the faster obsolescence of management knowledge, it is essential to have knowledge that is constantly updated and targeted by sector of activity, company size, and management issue. This is all the more essential because ExecEd is increasingly committed to lifelong learning, with shorter programs that are more dispersed throughout the career.

Today’s business school, taken in isolation, with its permanent faculty of between 150 and 300 professors generally, will not be able to provide the answers to this variety of needs requiring constant updating and dealing with heterogeneous business sectors and countries.

Alliances will be required, first to boost the revenues that will be increasingly necessary to finance investments (growing faculty size, digital development, rethinking buildings and real estate, etc.). Business schools will not disappear totally – there will always be a need for research production and teaching professionals (management faculty reproduction). The decade from 2010 to 2020 saw the Shanghai research ranking reach its acme, introducing a race toward high productivity in research, and business schools will continue to be ranked according to their ability to select the best students, their ability to produce research, and their ability to produce and market attractive and updated digital modules.

2. Partnerships at a Crossroads

In terms of alliances to be made, business schools are currently at a crossroads; according to the trendsetters, these alliances will be of four main kinds:

1. Alliances inside the existing network of business schools in order to provide a broad range of resources, combining materials from reputable business schools located in different geographies: the CEMS, with Bocconi, Cornell, Calcutta, and Keio, among others, is one illustration of a such a pioneering initiative.

2. Alliances with a consortium of companies (by sector, size, country). Business schools, mostly those with specialized know-how (supply chain, finance, leadership development, etc.), will thrive on a real-time connection with industrial partners. The latter will provide the expertise and high-caliber teaching leaders that will make the consortium extremely attractive to students.

3. Alliances with EdTech are also very likely, although there are risks of cannibalization. EdTech companies will be seeking academic legitimization, whereas schools will be in search of technological innovations.

4. Alliances with consulting companies will certainly be more promising because business schools and professional service firms (PSFs; consulting and advisory firms) are almost next of kin. Both are knowledge extensive and have education as a common differentiating factor. Business schools have the mission of grooming future leaders, whereas PSF or audit and advisory firms excel in tailoring management advice to the upper echelons of organizations.

My take is that it will be hard for business schools to establish sustainable alliances with all of these different players at the same time. Business school deans and governance will find themselves facing strategic choices and having to weigh up the relative benefits of their newly wrought relationships: the likelihood of boosting ExecEd revenues, raising their profile and enhancing their reputation, creating a sustainable and inimitable advantage, and increasing outstanding faculty and selected students.

3. Partnerships for MBA and Doctorate Programs

Alliances may also develop on several specific program levels (bachelor, master/MSc, and PhD). I would take the example of the visionary Next MBA program that Mazars developed in 2012 with participants from six or seven leading international companies. In this spirit, Mazars is working with business schools to develop its top leaders through a PhD degree. It provides the experience of research, with the dissertation topic being aligned with the job profile of the future leaders. Whereas in the past, top leaders would not find the time to enroll in a time-consuming PhD program, in the 2020s, we will certainly see growth in executive PhDs for senior managers eager to look at their practice with hindsight and contribute to management science. Such doctoral undertakings are very likely to have the following features:

1. Academic production focused on the hot managerial issues the leaders have on their front burners. In the near future, corporate social responsibility may very well also include academic social responsibility (ASR), especially in business environments fraught with risks of fast knowledge obsolescence.

2. These PhD degrees will serve as markers to differentiate the development paths of high-caliber leaders who will be seen as able to translate knowledge into action. As PhD holders, they will obtain a token of in-depth investigation skills and a sign of helicopter-view abilities.

3. Their doctoral pieces may get published in journals because they will present guarantees of scientific regard, as well as transferability to practitioners.

4. These future “leaders and doctors” will ideally be mentored by a tandem of two PhD supervisors representing the two worlds of academia and practice, very much in the approach and spirit of Peter Drucker in The Practice of Management (Drucker, 1955/Reference Drucker2007):

Above all, the new technology will not render managers superfluous or replace them by mere technicians. On the contrary, it will demand many more managers. It will greatly extend the management area, many people now considered rank-and-file will have to become capable of doing management work. The great majority of technicians will have to be able to understand what management is and to see and think managerially. And on all levels the demands on the manager’s responsibility and competence, his vision, his capacity to choose between alternate risks, his economic knowledge and skill, his ability to manage managers and to manage worker and work, his competence in making decisions, will be greatly increased.

5. PhD dissertations of this new kind will necessarily be innovation oriented. Disruptive methodological approaches must be encouraged.

6. It goes without saying that digital transformation aspects will be central to most dissertations of the 2020s.

7. The augmented “doctor and leader” is bound to play a key role in the dissemination of knowledge to peers internally and clients externally. This constitutes a radical change from the times when knowledge was reserved only for the learned.

4. The Making of the New Corporate University

From all of the previously discussed points, the profile of tomorrow’s new corporate university will emerge. Broadly speaking, its characteristics will include the following:

1. A close link with the company’s strategy. The role of the university will clearly be seen as a support mechanism for the company’s global strategy. A specific budget will clarify the contributions of each participant (business units, central budget, the participants themselves, etc.), whether for training activities or for obtaining certificates and diplomas, because all this will be done in the framework of partnerships with business schools.

2. Close coordination with career management. More than ever, the corporate university will be linked in with the systems for identifying potential and career development. Several modalities will exist on the spectrum:

Option 1 – participants are sent by career management.

Option 2 – the university defines the profiles of the participants it hosts.

3. Identification of target populations. This presupposes the existence of a sufficient internal population to justify the existence of a dedicated structure. In terms of volume, we find the following:

Level 0 – COMEX and extended COMEX (top 300)

Level 1 – COMEX-1 staff and leading experts (top 2,000). Integrate expertise and functional aspects.

Level 2 – those considered capable of joining level 1 (“key players”).

Level 3 – “key business lines of the company.” The aim is to provide business units with training that is specific to their profession and know-how.

Level 4 – “customers, suppliers, and ecosystem.” Corporate universities will also develop modules bringing together the different stakeholders in the company. In the extreme, participants from competing companies will reflect together on sector developments. The environmental, social, and governance (ESG) dimension will be more prominent than ever before in the modules and certificates issued.

4. A range of offers. There will be variety in the portfolio of education courses, their durations, e-learning methods, certification, and the possibility of combining several modules that will progressively earn credits towards obtaining a diploma. All the content will be updated very regularly. Participants will also be the developers of modules for others.

5. A metric and permanent tracking. Assessments will be carried out in an automated way to evaluate (1) the individual progress of participants, (2) the overall quality of a program, (3) the efficiency of the corporate university, and (4) the internal and external stakeholders. Obviously, a tracking system linked to information systems will make it possible to follow up with and motivate participants by tracking what they have received and read, or not, and so forth. This learner-centric approach will make it possible to provide highly individualized services. This is the advent of learning analytics, the main vocation of which will be to motivate and accompany participants in their learning. The electronic terminals (e-beacons) placed in the company will remind participants of their training duties.

6. External recognition through accreditation bodies, such as Corporate Learning Improvement Process (CLIP)/European Foundation for Management Development (EFMD), partners of business schools, professional branches, and so forth. Just as there are business school rankings, the visibility of company universities will be reflected in rankings highlighting the triple added value for the individual, for the company, and for society.

Conclusion

Our community is particularly proud of the mission statement we set for ourselves a few years ago: “To inspire and educate business leaders who will impact the world.” In that collective spirit, it falls to me to salute the initiative of three colleagues who have launched and steered this project with incredible energy and commitment. On behalf of our president, Philippe Houzé, and everybody here at ESCP, I would therefore like to take this opportunity to thank Pramuan Bunkanwanicha, Régis Coeurderoy, and Sonia Ben Slimane, without whom the project would never have risen to such heights. The call for contributions inspired a veritable flood of original scientific work, despite the fact that faculty members were already overburdened by the sudden need to create teaching materials for remote learning while also preparing for an unprecedented level of digital engagement in 2020–21. Once again, I would like to express my admiration and extend my sincere thanks to all the colleagues who have contributed to this wonderful outpouring of intellectual solidarity and stimulation. Thank you for sharing so generously the fruits of this prolific period of reflection, inspired by these uncertain times.

ESCP is a business school with a profound connection to the European humanist tradition. As we traverse this time of global crisis, I am reminded of a passage from the memoirs of Jean Monnet, one of the founding fathers of the European Union, published in 1978. His words ring as true now as ever, and they offer a beacon as we navigate these turbulent times: “When people find themselves in a new situation, they adapt to it and they change. But so long as they hope that things may stay as there are, or be the subject of compromise, they are unwilling to listen to new ideas” (Monnet, Reference Monnet and Richard1978, p. 344).