Introduction

Gender equality is now clearly established as a policy action area for the international community. Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5 calls on all nations to achieve gender equality and empower women and girls. Key global bodies, such as the UN, the World Bank, and the European Union promote gender equality across their activities. United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 and the successive nine Women, Peace and Security (WPS) resolutions state that countries must consider the needs and rights of women in their security policy, and over ninety countries have adopted National Action Plans (NAPs) on WPS. At the same time, however, there has been a simultaneous pushback from certain states and political actors against gender equality policy, and, in some, at the very concept of gender itself.Footnote 1 Worldwide, there has been a rise in illiberal, populist radical right politics, which often espouses anti-feminist and homophobic attitudes.Footnote 2 This has the potential to destabilise what are now internationally accepted standards around gender equality.Footnote 3

Two such countries that have witnessed contemporary political resistance to the idea of gender are Brazil and Poland. Jair Bolsonaro was elected to the Brazilian Presidency in 2019 on the back of a homophobic and misogynistic campaign. This has continued in office, including a crusade against so-called ‘gender ideology’ and the attacking of gender studies in universities.Footnote 4 In Poland, the 2015 election saw the Law and Justice Party (PiS) win an outright majority. In 2020, Poland declared that they would withdraw from the Istanbul Convention on violence against women. In 2021 laws further restricting abortion in the country to an effective blanket ban were enacted, despite widespread street protests.

In spite of these illiberal moves with regards to gender equality, both Poland and Brazil have enacted NAPs on WPS. Poland did so in 2018 under the PiS Government, and Brazil in 2017, in the context of the political crisis relating to Dilma Roussef's impeachment and the rise of Bolsonaro. Why have they done so? Why have two governments that have been responsible for regression on gender equality measures chosen to work on the WPS agenda? Why do states that are resistant to gender equality (and multilateralism) engage with the WPS agenda and produce NAPs in relation to it?

This article has two main aims. Firstly, it contributes important comparative case study work to the literature on WPS. There is relatively little work on the Global South (particularly Latin America) and Central/Eastern Europe; equally there is little work on how anti-gender states and politics interact with WPS.Footnote 5 This article aims to address these gaps. Secondly, it aims to empirically demonstrate how the utility of a feminist institutionalist (FI) framework, as adopted here, can help to deepen our knowledge of the WPS agenda. We argue here that an FI framework helps us to understand how NAPs come to be; how they emerge in political contexts we might not expect them to; and that ultimately an FI approach gives us a more dynamic understanding of the WPS agenda, seeing it as a political and contested process both within states and in conversation with international actors.

In what follows we argue that the NAPs in Brazil and Poland were created due to unique features of the institutional arrangements around both in each country – particularly the work of key critical actors, and the militarised nature of the agenda that inhibits CSO awareness and involvement. As such, the well-documented militarisation of the WPS agendaFootnote 6 impacts not just the content of NAPs but also the broader institutional context in which they are created. We further argue that NAPs have been adopted in these countries as the result of external pressure, particularly from NATO in the Polish case, and that they are largely seen by these states as a necessary box to tick in relation to their foreign and security policy. The Brazilian and Polish NAPs are thin in terms of their aims, monitoring, and budgeting, as we show below, and largely exist as symbolic rather than substantive documents. The NAPs therefore allow these states to exist, in the words of one Brazilian interviewee, in an international ‘VIP club’, but provide little in terms of government action and commitments. This symbolic nature of WPS has key implications for the agenda and scholarship related to it, and for the study of gender politics in these two countries. As such, the article makes a key contribution to the literature on the WPS agenda but also bolsters academic arguments that the idea of gender ‘backlash’ needs greater complexity – as we show here, in relation to their domestic and international audiences, states are willing to adopt very different attitudes to gender if it helps to further their interests.

The article proceeds as follows. Firstly, we consider the concept of anti-genderism and the literature related to it, paying specific attention to Brazil and Poland. We then introduce FI as the methodological framing for our analysis, before providing greater context on our two case studies and their NAPs. A consideration of our in-depth interviews in Brazil and Poland follows, before a concluding discussion.

‘Gender ideology’ as ‘symbolic glue’

Recent decades have witnessed a global rise in public discourses and organisations acting in opposition to ‘gender ideology’. The term is described by scholars as an empty signifier or ‘symbolic glue’,Footnote 7 which acts as an umbrella to bring together a wide range of populist, nationalist, conservative, right wing, and religious interests. Uniting these positions is a discourse where movements and leaders reimagine memory of the past and define national boundaries through a vocabulary of kinship (for example, ‘motherland’) and masculinist claims of protection. The gendered dimensions of these nostalgic narratives and founding myths of national identity reflect the power of a dominant patriarchy, emphasising traditional family gender roles and heteronormative notions of gender identity.Footnote 8

Some scholars refer to anti-genderism as a backlashFootnote 9 against dominant ideas around women's and gender equality, including an opposition to same sex marriage and LGBTQ+ rights, restricting women's reproductive rights and policies addressing gender-based violence, as well as a hostility towards gender studies and gender equality education. However, to consider this opposition simply as ‘backlash’ is too reductionist. Anti-gender movements can be seen as a symptom of a wider social and economic crisis, particularly growing concerns about citizens’ control over the state and its policies, with their anti-gender outlook being ‘for the most part, just a handy cover’.Footnote 10 Furthermore, the concept of ‘backlash’ may be too simplistic or Western-centric for many of these local contexts. Many countries that are currently seeing a manifestation of anti-gender politics have had a much more complex transition towards equality between men and women compared to the gradual shift in policies and attitudes in most Western countries. Such countries’ journeys have been influenced by transitions from communism and military dictatorships, and vastly differing local circumstances with regards to religion, state capabilities, and women, and the discussion of sexuality in public life. ‘Backlash’ does not therefore adequately capture the anti-gender phenomenon.Footnote 11

‘Anti-genderism’ brings together a transnational and ideologically diverse set of actors and values but is embedded through ideas of the local. It is the specific combination of localised dynamics alongside the international sentiment that provide the basis for a powerful anti-gender discourse. For example, in the case of Central and Eastern Europe, opposition to gender ideology plays on experiences of post-1989 democratic transition and is referred to as being worse than communism and Nazism put together.Footnote 12 Mila O'Sullivan and Kateřina Krulišová argue that in the rhetorical pairing of the words ‘gender’ and ‘ideology’, ‘“ideology” evokes the historical trauma of communist rule’, thus situating the specific cases of Central and Eastern Europe in their immediate pasts.Footnote 13 Equally, in a Brazilian context, anti-genderism is linked to wider social progressivism and placed in contrast with the militarised nostalgia for the past dictatorship that Bolsonaro embodies.Footnote 14

At other times, gender is seen as a contemporary colonising tool used by the ‘West’ and transnational institutions (embodied by the EU, UN, WHO, World Bank, NGOs) to impose liberalising values. Resistance to ‘gender ideology’, embodied in international agreements such as the Istanbul Convention, is centred upon a threat to national identity, values and tradition as well as the protection of sovereignty and resistance to a global liberal elite. The attacks on gender equality have therefore moved beyond a conservative anti-feminism focused on sexual and reproductive rights, to a much broader ideological construct which involves critiques of a cosmopolitan elite and struggles for national sovereignty in a global liberal system.Footnote 15 For Agnieszka Graff and Elżbieta Graff the 2008 economic crisis revealed the weakness of neoliberal economics as well as liberal democracy as a space for processes of inclusion, equality, and freedom.Footnote 16 The resistance to this diffusion of pro-gender norms can therefore be situated within the wider growth of liberal norms in the international arena and opposition towards contemporary global capitalism.Footnote 17

Anti-genderism in contemporary Brazil and Poland

The notion of ‘gender ideology’ has a long history in Brazil (and Latin America more broadly),Footnote 18 but has intensified under the campaign and subsequent election of President Jair Bolsonaro.Footnote 19 His election was an abrupt right turn for Brazilian politics, which had been ruled by the left wing PT party (Partido dos Trablhadores; Worker's Party) from 2003 until 2018. Under PT, and particularly under the Presidency of Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva (Lula), a raft of major social reforms was enacted. The cash transfer programme Bolsa Família saw money given directly to over 13 million families by 2019,Footnote 20 with specific branches of this targeting pregnant and breastfeeding women. The later Minha Casa, Minha Vida initiative was the country's first attempt at large-scale public housing construction. Lula's presidency also saw the introduction of affirmative action policies in higher education, with the aim to increase the numbers of black students gaining degrees. The recipients of these programmes were largely poor people of colour with some, such as Bolsa Família, specifically directed towards women. The contemporary rejection of liberal moves around race and gender and turn to Bolsonaro therefore needs to be understood in the context of recent Brazilian politics, and in part as a rejection of the past PT presidencies and the political and social changes that they have enacted.

Gender in particular had been used by Bolsonaro and the right in Brazil as a litmus test to indicate how far the country has strayed from its perceived values. Before and after his election, Bolsonaro espoused strongly homophobic, racist, and misogynistic views.Footnote 21 In his inauguration speech in January 2019, Bolsonaro declared that: ‘We are going to unite our people, embrace the family values, respect the religions and our Judeo-Christian tradition, fight against gender ideology, while preserving our values.’Footnote 22 Such rhetoric is not unique to Bolsonaro alone in his government – his Minister for Women, Family and Human Rights, Damares Alves, said in her inauguration that Brazil was initiating a new era, in which ‘boys wear blue and girls wear pink’.Footnote 23 ‘Fake news’ around the state's alleged involvement in children and gender and sexuality education was endemic in the run-up to Bolsonaro's election.Footnote 24 This mobilised Brazil's large conservative Pentecostal and Evangelical churches in particular, who were a key force in his victory.Footnote 25

This sense that Brazil has ‘lost its way’ manifests itself largely in relation to gender but is closely linked to Bolsonaro's nostalgic stance on Brazil's past dictatorial rule. Bolsonaro has spoken fondly of the dictatorship and himself had a long military career. In his electoral campaign, he declared that he wanted to make Brazil what it was ‘40 or 50 years ago’, when it was ruled by the military.Footnote 26 When voting to impeach former President Dilma Rousseff in 2016, he praised the Army Officer who had been convicted for the torture of her and hundreds of others.Footnote 27 Brazil's ‘Culture Wars’ therefore extend beyond questions of gender and sexuality, linked to more fundamental questions about the country's past and its ongoing legacy in Brazilian politics and society.

In Poland, the electoral victory of PiS was similarly fuelled by a conservative campaign against ‘genderism’.Footnote 28 Since 2012, anti-gender movements intensified following the signing of the Istanbul Convention.Footnote 29 Despite already having one of the most restrictive abortion laws in the EU, in 2020 the Constitutional Court ruled that the 1993 law allowing abortion in cases of severe and irreversible foetal abnormalities was unconstitutional. The ruling, which meant that abortion was now only permitted in cases of rape, incest, or when the woman's life is in danger, initiated the largest street protests in the country's recent history. The decision is not only a reversal of reproductive rights but also raised wider concerns of democratic backsliding, particularly the legitimacy and transparency of the Constitutional Tribunal. Former Prime Minister of Poland Donald Tusk commented, ‘To throw in the subject of abortion and produce a ruling by a pseudo-tribunal in the middle of a raging pandemic is more than cynicism. It is a political wickedness.’Footnote 30

Amid criticisms from political opponents for undermining democracy, human rights and the rule of law, PiS remain politically popular.Footnote 31 The party are trusted on socioeconomic issues and have delivered significant social spending pledges that were central to their 2015 electoral success. Most significant of these is ‘Family 500 Plus’ – a child benefit programme that provides financial support to low-income households – and has been described as a pro-natalist family policy that frames women as the caregivers and introduces an earlier retirement age for women resulting in lower state benefits.Footnote 32 While cementing the role of women as the primary care givers within the traditional family model, such policies have been popular among those who felt they had been left behind by Poland's post-communist economic transformation.

An important moment for tracing anti-genderism in Poland was the country's accession to the European Union in 2004. This process of Europeanisation brought with it increasing unease about citizens control of the state and external interference in the domestic policy environment. For example, regulations on EU funding involved relatively strong provisions on gender equality and included sanctions for non-compliance. Gender mainstreaming has therefore been fostered by external international commitments and implemented via bureaucratic processes. Marta Rawłuszko argues that the implementation of such elitist and technocratic conditions unintentionally provided the impetus for anti-gender mobilisation through depictions of colonisation and infiltration of the state by means of gender ideology. Therefore, anti-genderism is also symbolic of the resentment felt towards negotiating EU membership as ‘outsiders’ and having to ‘catch up with the West’ as a key part of the country's post-communist ‘democratisation’.Footnote 33

Across both contexts, the attacks against ‘gender ideology’ not only demonstrate resistance to gender and LGBTQ+ equality but growing concerns about sovereignty and control of the state. Emphasising the growing role of unelected bodies and ‘foreign elites’ plays on the suspicion of global and transnational institutions who promote individualism, human rights, and gender equality at the expense of traditional family values, the nation, and Christian values.Footnote 34 Therefore, as seen in other illiberal contexts, the demonisation of ‘gender ideology’ provides a symbolic glue to unite a broad range of right wing conservative actors as part of a wider transnational opposition to the neoliberal international order.Footnote 35 This, however, appears to be at odds with involvement in liberal norms and policy agendas at the international level, with WPS being one key example.

Feminist institutionalism and WPS

Since its formal inception in 2000 with the first UN Security Council Resolution, NAPs have been a key means through which the WPS agenda is both realised and studied. Denmark was the first country to adopt a NAP in 2005 and since then a further 92 countries have followed suit. NAPs show how a state aims to ‘translate’ complex international legal and policy documentation into domestic strategy.Footnote 36 They provide the clearest insight into what is going to be prioritised by states in relation to WPS, and how the agenda is going to be taken from relatively abstract legal text to working policy. In 2015, UNSC Resolution 2242 called on UN member states to further adopt NAPs and encouraged the extensions of these frameworks to regional organisations. Eleven have now produced Regional Action Plans (RAPs), including the EU, the African Union, and NATO.Footnote 37

The proliferation of NAPS has brought strong scholarly interest in their development. Academic work has addressed the development of NAPs within particular regions, including Africa,Footnote 38 the ASEAN community,Footnote 39 and South America.Footnote 40 Much work has also looked at individual countries’ NAPs.Footnote 41 Other scholars have explored how particular areas of the WPS agenda emerge in NAPs, such as countering violent extremism,Footnote 42 or the focus on SGBV.Footnote 43 Literature has also considered the relative silences that have been seen in NAPs with relation to refugee and asylum seeking women,Footnote 44 reproductive rights,Footnote 45 and sexuality.Footnote 46 The majority of this work focuses on deconstructing policies, content, and language of NAPs, although more recent work also considers the visual elements of NAPs.Footnote 47

There has been less academic interest in the production of NAPs or the behind-the-scenes processes that go about creating them. Some work has addressed the interplay between the institutional context and the policy focus on WPS. Megan Dersnah considers the role of gender experts in the shift in WPS to a greater focus on SGBV.Footnote 48 O'Sullivan and Krulišová consider the behind-the-scenes development of the Czech NAP.Footnote 49 Barbara Trojanowska addresses the Filipino context, and the importance that the institutionalisation of the agenda has had in seeing off challenges to it under Duterte.Footnote 50 Beyond a few such examples, however, the majority of the work on WPS and NAPs prioritises the content of NAPs over the process of their creation. While there are clear empirical and methodological reasons for doing so, this creates a gap in our knowledge. Without an understanding of NAP development, we miss key insights into the politics of their production – including how the scope of the NAP is framed, how civil society is or is not involved and in what capacity, and why certain areas of policy are included or left out.

We propose that insights from feminist institutionalism and thinking are useful here to help explain how NAPs are created and how their focus changes across context. Feminist institutionalism (FI) is interested in the ways that the ‘formal structure and informal “rules of the game”’Footnote 51 of institutions are gendered. It is concerned with the ‘co-constitutive’Footnote 52 nature of political institutions – the ways in which institutions create gendered rules, and gendered rules in turn help to shape institutions. It focuses on the ways in which the state is not a monolithic entity, nor merely a microcosm of the broader society in which it exists, but rather a set of different bodies each with differing impacts on policy creation and action. It is often interested in the ‘logic of appropriateness’ within states, and the extent to which that helps or hinders action around gender and policymaking.Footnote 53 As such, it helps to explain how the gendered nature of institutions impacts the scope and agenda of political and policy outcomes.

More recent FI work is also an attempt to move between the current ideological impasse of much feminist theory.Footnote 54 A dichotomy has emerged in contemporary feminist scholarship between that which argues that feminism has been co-opted to the ends of neoliberal economic and state agendas, and that which argues that feminism remains instead a critical and resistant force around the world. In many ways, the literature around the WPS agenda represents a clear example of this duality. The agenda has been widely critiqued for being watered down, for losing its original pacifist focus, for overemphasising women's victimisation, particularly in the context of sexual violence, for being increasingly militarised, and for a ‘ritualistic’Footnote 55 rather than a committed quality. As such, some have argued that the WPS agenda has become co-opted.Footnote 56 At the same time, its continued championing by the UN and other key bodies, its relative youth compared to other international norms, and high-profile occurrences such as the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize in 2018 to Nadia Murad and Denis Mukwege for their work against sexual violence in conflict, indicates that WPS has had a transformative impact on mainstream understandings of security and has the potential to continue to do so. The tensions between a ‘strong co-optation thesis’Footnote 57 that views all feminist engagement with the state as doomed, or a naïve focus on resistant and powerful individuals/institutions has lead in many ways to a theoretical impasse, which can be equally seen within the academic and practitioner discourse on WPS.

The methodology afforded by FI offers a way out of this either/or conundrum. FI methods offer a way to understand both ‘the limitations, shortfalls, missteps and intended and unintended consequences of insider actions and strategies, at the same time as being sympathetic to the need to engage with existing institutional arenas’.Footnote 58 This combination of sceptical insider knowledge is obviously particularly important in contexts like those that we consider in this article, where feminist actors within states may have complicated relationships with those in power, and may face great hostility to their work from the political institutions they are engaging with. Furthermore, the ways in which anti-gender states such as Brazil and Poland have used WPS may suggest a co-optation of gender equality ideas – but it also provides an important opportunity to think about how feminist actors work within the state to find ‘small wins’Footnote 59 and windows of opportunity for change.

A FI framework can thus help to contribute important insights into the literature on WPS. It can help to highlight the importance of the institutional context in a NAP's creation, including how they come to focus on specific areas and not others; to show the role of bureaucrats/critical actors with the passage of NAPs (to ‘brings actors back in’);Footnote 60 and it can be used to illustrate the political trajectory of NAPs and the broader agenda around WPS in a government after they have been written. A FI framework allows us to see NAPs not just as discursive entities, but as political documents, which have been created through a protest of contest, and negotiations by multiple actors, agencies, and institutions.Footnote 61

Methodologically FI opens up the ‘black box’ of an institution and allows a focus on actors and processes.Footnote 62 Louise Chappell and Fiona Mackay recommend getting ‘as close as possible through interviews and ethnographic methods, in addition to studying core texts’.Footnote 63 A combination of in-depth elite interviews and analysis of the NAPs’ content was employed. This combination was to ensure an understanding of both the substance of the finished documents, but also the process of their creation.Footnote 64

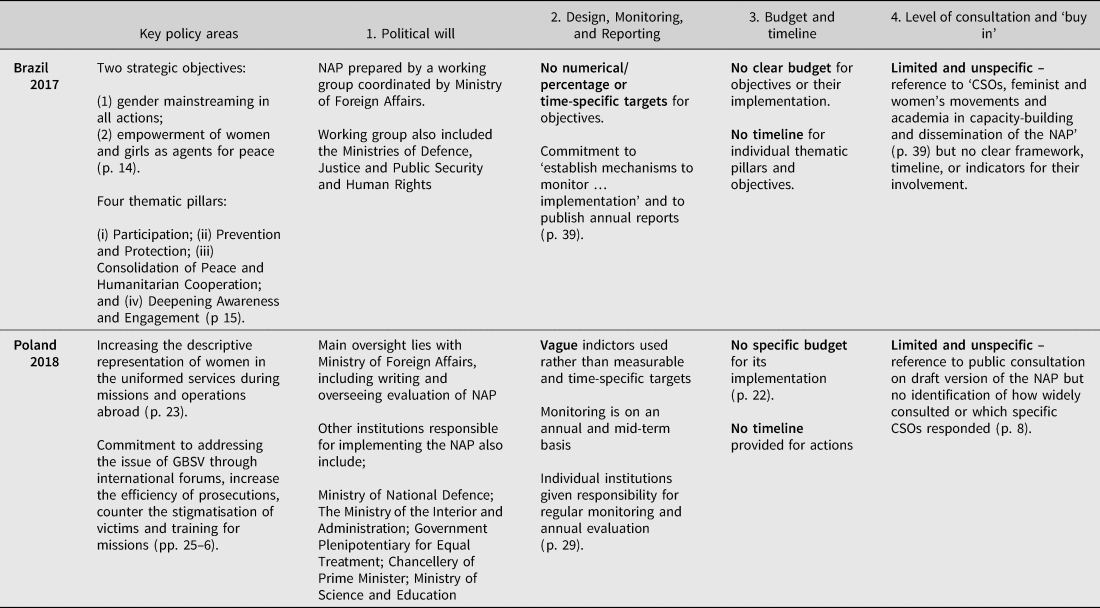

The content of the NAPs were analysed in order to provide a summary of the documents’ breadth, design, and focus. To comparatively assess the NAPs, a framework derived from work by the NGO Inclusive Security and their concept of a ‘high-impact NAP’ was applied. It argues that there are ‘four key challenges in the design and implementation of NAPs: (1) lack of political will; (2) failure to include relevant design and monitoring and reporting methods; (3) no defined budget or timeline; and (4) lack of “buy-in” due to limited or no consultation with a wider set of government agencies, as well as groups like civil society, minorities, and men.’Footnote 65

In addition, interviews with individuals involved in the production of the two NAPs in Brazil and Poland were sought. A relatively small number of interviews were conducted but were specifically requested with key individuals in both case study countries who had been closely involved in the writing and production of the NAPs. Ten interviews in English were conducted with individuals in Brazil and Poland, from a range of backgrounds including civil society, state bureaucracy, and academia. Interviews lasted around an hour each and were inductively coded via NVivo according to the themes that emerged in each. Given the sensitive nature of this research, all quotes are attributed anonymously.

Brazil and Poland make for an appropriate comparison in this area for several reasons. Both have enacted their first NAP in recent years (Brazil in 2017, and Poland in 2018). Both had transitions from dictatorial/authoritarian systems in similar time periods. As shown above, both have also seen the rise to power of governments that espouse strongly critical positions on gender and have made efforts to roll back national and international standards on gender equality. This happened in very similar time frames in each, making for appropriate comparison. The cases also provide two comparative examples from different geopolitical contexts. In the European context, Poland had pre-existing commitments to WPS through military alliances that are important to the country's security (for example, NATO). Providing a case study from the Global South, Brazil is an opportunity to highlight the role of critical actors in this context where existing literature on WPS is accused of ignoring their agency in implementing and shaping the agenda.Footnote 66

NAP development in Brazil and Poland

The NAPs of both countries are notable for being largely conservative in their aims and vague in their ambitions. The two documents are also similar in that they are both externally focused and frame conflict as something that happens beyond domestic borders.

As Table 1 shows, both NAPs largely fail the criteria for a ‘high-impact NAP’. Neither has a clear budget or timeline for implementation. Where dates do exist in the Brazilian case, interviews suggested that they have not been met. Both largely had vague objectives, with little detailed sense of monitoring or reporting. Both equally showed little sense of how CSOs were going to be involved in the agenda in either country moving forward. Various departments are named as responsible for the implementation of the NAPs, yet it was not clear from the documents alone how well the actions have been coordinated or the extent of ‘political will’ across various ministries.

Table 1. Policy content of Brazilian and Polish NAPs.

Sources: Adapted from Mirsad Miki Jacevic, ‘WPS, states, and the National Action Plans’, in Sara E. Davies and Jacqui True (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Women, Peace and Security (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2019), p. 273. Government of Brazil (2017), National Action Plan on Women, Peace and Security, Brasilia. Unofficial translation, funded by ARC DP160100212 (CI Shepherd); Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Poland 2018, Polish National Action Plan on Women, Peace and Security 2018–21, Warsaw.

While providing an overview of the NAPs’ content and design, this initial analysis was also used to inductively structure interviews with key actors involved in WPS and its implementation across the two case studies. Interviews enabled a closer examination of the institutional challenges that existed throughout the process of NAP formation. We discuss the findings here along three thematic lines which emanate from FI thinking: (a) the interaction between CSOs and government; (b) the influence of international institutions and actors; and (c) the role of critical actors within the institutions.

a. Civil society's involvement and interaction with government

There was limited government interaction with CSOs in the process of writing both NAPs. Only one CSO, and only one individual within that CSO, was involved in Brazil. This individual stressed in interview that she was there because of her expertise, which was needed by the government to write the NAP. Beyond this limited involvement, there was a repeated sense from interviews that civil society in Brazil was not heavily invested in the WPS agenda. Interviews repeatedly stressed that CSOs and the broader women's movement had little understanding or awareness of the WPS agenda and the ways in which it might be useful to Brazilian civil society/activism.

[W]omen's movements in Brazil don't really think WPS agenda can be an … agenda that addresses their main concerns and priorities. (Interviewee 4)

[P]eople are not really engaged and do not necessarily know what the NAP is. (Interviewee 1)

This was related to the fact that WPS is perceived as a militarised agenda in Brazilian civil society. The history of military-civil society relations in Brazil means that there is greater reticence on the part of CSOs to engage with an agenda that seems to be aligned with military interests (Interviewee 2). This was also reiterated by the portrait that interviewees portrayed of the dominant role that the Department of Defence played in the production of the NAP – ‘there were some issues that had to be taken out in order … to appease Defence. Especially Defence’ (Interviewee 2). Finally, interviewees also stressed that the WPS agenda was ‘an agenda from the [Global] North’ (Interviewee 1). As such, it did not speak to the specific issues around WPS facing Brazil and that CSOs and activism mobilise around. The combination of limited state interest in external involvement and the lack of CSO interest in WPS meant that civil society played a very limited role in the development of the Brazilian NAP.

Relatedly, all interviewees stressed dissatisfaction that the NAP spoke so little to Brazil's domestic concerns. Brazil poses a paradox for the WPS agenda. Although the country is in many ways deeply insecure,Footnote 67 its problems do not fit the mould of security and conflict as the agenda (or the UN Security Council more broadly) understands it.Footnote 68 Blame for this refusal to adapt the WPS agenda to Brazil's domestic circumstances was again largely placed at the feet of the Government, in particular the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and their desire to limit the NAP to international concerns: ‘even with people who believe in the WPS agenda in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs they would be very sceptical of including anything that might give an impression that we are not very stable or that we are facing problems’ (Interviewee 1; also Interviewees 4 and 5). Interviewees closely involved with the process also stressed how the vision of the NAP forwarded by civil society was drastically watered down by the government in the final document.

Furthermore, interviewees largely reported that the government has done little around the WPS agenda since the NAP was published.

I: How did it (the NAP) continue into the Bolsonaro presidency?

R: Some would say that it didn't continue. (Interviewee 5)

He [Minister] launched the plan but then nothing was really done after that. (Interviewee 1)

[A]s far as I know, they [the government] don't talk about the NAP. (Interviewee 5)

Interviewee 1 related an anecdote where she heard a Brazilian diplomat who had worked in Syria give a presentation on her work with Syrian women. When she approached the diplomat afterwards to ask her about her work and its relationship to the NAP, the diplomat had never heard of the document despite working in this area for some time. The absence of political will around the agenda has extended beyond the creation of the NAP and there appears to be little interest in its promotion or implementation.

This sense of an unambitious and unclear NAP was reflected in the interviews conducted. Interviewees felt that the NAP was very limited in its aims: ‘There is nothing there that will oblige anyone or necessarily impose anything … Brazil committed to this plan without having any cost so they are not so afraid.’ (Interviewee 4) The lack of government action around the NAP as described above, in addition to its very limited aims, saw interviewees convey a sense of a missed opportunity. At times interviewees shared a worry that the NAP had contributed to problems by creating the appearance of action when there had been none. Some evoked a sense of being complicit with the government rather than enacting change:

I'm not even sure if Brazil should really have this NAP and if this is like something that helped to get where we want in terms of progressive perception of what gender equality should be and what our concerns should be. Because I feel that we had like a bunch of real engaged people that kind of forced this plan to happen and convinced the right authorities there at the right moment but it doesn't reflect like our plan, doesn't reflect a country momentum, or demands from civil society, it doesn't – so it is not real in this sense. (Interviewee 4)

This was also referenced in the context of the absence of domestic issues in the NAP and government resistance to this. Overall, interviews reflected the sense that the Brazilian government was not keen to be especially innovative in their NAP, did not clearly engage with CSOs and that the Department of Defence in particular exerted control over the tone and focus of the document.

In Poland there was a similar sense of reluctance from the government at an earlier stage of the NAP's inception, which pre-dated the election of PiS. During the period of government by Donald Tusk's centre-right party, Civic Platform (PO), there was an unwillingness from the relevant ministries to take ownership and lead coordination efforts on WPS. This reluctance was illustrated by a general sentiment of, ‘yeah we're interested in this resolution, and it'll be great, but we don't really want to take the lead’ (Interviewee 7). The Government Plenipotentiary for Equal Treatment, which does not have its own budget and sits within the Chancellery of the Prime Minister, were described as ‘The only office that positively reacted to the proposed implementation of UNSCR 1325 and the creation of the Action Plan’ (Interviewee 10). None of ministries involved in implementing existing projects related to 1325 (due to international obligations, for example, NATO missions) wanted to take over the coordinating role of the NAP (Interviewee 10).

Despite these initiatives initially driven by women in the military and civil society, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs resisted pressure to implement a NAP on the basis that the resolution could be implemented in other ways (for example, Poland already participated in the reporting system on the implementation of UN, EU, and OSCE-led resolutions). In 2013 a civil society organisation involved in advocacy for 1325 commented on the continued absence of a Polish NAP being ‘attributed mainly to the lack of political will and lack of inter-ministerial cooperation in Poland … the situation may be an outcome of resistance to acknowledge the importance of gender equality issues in Polish politics in general.’Footnote 69 Considering the political concerns around gender mainstreaming that existed pre-2015, alongside the lack of political leadership on the issue, the eventual adoption of the NAP under the right wing PiS government in 2018 is even more surprising.

The second part of the NAPs’ journey began after the election of PiS in 2015, where initial signs made the formation of a Polish NAP appear even more unlikely. Interviewees noted how during this time of political change in Poland, the Women in Uniformed Services advisory group, originally formed to coordinate the work of relevant ministries and civil society on a Polish NAP, was disbanded (Interviewee 8). In addition, key actors with extensive knowledge and experience in this field were not invited to cooperate in any future efforts, despite declaring a willingness to do so (Interviewee 10).

The eventual arrival of the NAP in 2018 came from the Department of the Security Policy, within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, where there seemed to be very minimal, if any, continuation from the work carried out pre-2015. Those who worked on the creation of the NAP knew little of these previous efforts.

I know that there were attempts – 2014, ‘15, something before but I didn't know much about it … I think that was interesting and crucial in development of this NAP, that it came to us, the Department of the Security Policy. (Interviewee 6)

The internal story of the NAP was that ‘the document was developed in the governmental environment and later was consulted with civil society’ (Interviewee 6). Following approval from the ministries involved, an online consultation process was opened which received comments from two NGOs.

For those in civil society involved in the pre-2015 efforts to create a NAP, the arrival of the final document in 2018 was surprising as they were not aware of a consultation process or reached out to for feedback.

I know that these feminist organisations that we've worked with and human rights organisations in Poland were not consulted in the process of developing that NAP. Even though there had been an advocacy, that was civil-society led, this product that we ended up with, the current National Action Plan, was not adopted through a consultative process. (Interviewee 7)

The fact that civil society actors and individuals who were deeply involved in previous efforts to implement a NAP were unaware of this later process, suggests the final document was produced quickly and had a limited consultation process only after the document was written.

Across both contexts therefore, there was severely curtailed civil society involvement in the production of the NAP, and a lack of clear political will to comprehensively work on the agenda from government.

b. International actors

The influence of international actors and the multilateral political architecture was also important for both countries. In Poland, the creation of the NAP in 2018 can be traced to various sources at the international level. Firstly, several interviewees commented that the impetus for starting work on the NAP post-2015 was Poland's membership of the WPS National Focal Points Network (managed by UN Women Secretariat). It was described as a ‘crucial’ forum (Interviewee 10) and ‘really important’ (Interviewee 6) for the exchange of experiences and good practices. Original coordinating efforts to work on the Polish NAP were met with a reluctance by ministries to take ownership and lead on the implementation and monitoring of the agenda. However, by 2018 development of the NAP was facilitated by participation in this network alongside the personal decision of the Director of the Security Policy Department at the time, that Poland should actively engage in this agenda.

Secondly, external pressure was mounting from the international community for states to implement their own NAPs. Initially, NATO used the 15th anniversary of 1325 to affirm their commitment to the agenda and sent ‘a very clear signal’ during the NATO summit in Warsaw (July 2016) to member states ‘about their obligations to develop National Action Plans’ (Interviewee 10). Another catalyst from the international community for the NAP's appearance in 2018 was Poland's membership in the UN Security Council (as a non-permanent member), which began that same year.

Poland became a member of the Security Council and we started as a Department to gather information about Women, Peace and Security from different organisations and then when we received all theses emails from our embassies that Poland is one of not many countries which doesn't have a NAP … So really we had to have it and we started to work on a draft on April 2018. (Interviewee 6)

After 2015 the international pressure meant that the implementation of a NAP could not be sidelined, particularly in light of Poland's role on the UN Security Council. It was no longer possible to claim that 1325 could be implemented through existing partnerships and obligations rather than a NAP.

That's what's important. I would say, for the Western countries to join the Security Council without the NAP, it's a big challenge you know. How many years can you repeat that? ‘We do implement it, although we don't have a NAP’… and we were doing this for many years. (Interviewee 6)

As described by one interviewee, the NAP was an opportunity for Poland to project its image as a ‘reliable and responsible player in global politics’ (Interviewee 10).

In Brazil, the impetus appears to have been a statement at the UN made by a Brazilian delegate that the country aimed to launch a NAP (Interviewee 4). This initially appears contradictory to the reticence to engage with the agenda described above. Again, however, as in the Polish case, this willingness to engage with WPS on Brazil's part can be seen through an eagerness to promote the country as a good global citizen. Although, as shown above, the government did very little to promote the NAP internally, at times they were strategically keen to reference their work on WPS at the international level – ‘They [the government] use the fact that we have the NAP and they value that … they just mentioned the NAP when it's politically interesting’ (Interviewee 4). Even then, government reference to the NAP was only made in the context of issues that were perceived by the interviewees to be insignificant or tangentially related to WPS. Interviewees referenced a recent award given to a female Brazilian military peacekeeping figure by the UN,Footnote 70 but stressed that this had little to do with the WPS agenda or the NAP.

Furthermore, interviewees expressed a sense that having a NAP and referencing it in this piecemeal fashion gives Brazil a symbolic power on the world stage:

Having a NAP sort of puts Brazil in a club – in a VIP club even though it's not really. It should not be part of this club. And so sometimes we feel like we were used because the NAP … is being used [to] promote the ideals of a government that is very much against women's rights … It's basically enabling the government – [giving it] the right of passage in certain spaces [where] it doesn't belong. (Interviewee 2)

Maybe it's more a message to the international community than actually something that they think it could be really used or really applied in terms of both international and local projects. More symbolic, more imaginary … we are participating in a community of international countries that have that policy. (Interviewee 5)

The absence of political will as described in the previous section paradoxically sits alongside a context in which both governments are also interested in strategically promoting themselves as members of the WPS ‘club’. Their development of NAPs is used symbolically to stress their participation in the multilateral liberal system.

c. Critical actors

Finally, interviews in both countries stressed the importance of a handful of critical actors or ‘femocrats’Footnote 71 in the production of the NAPs. Brazilian interviewees stressed that the NAP was the result of ‘a very small number of women’ (Interviewee 1) who had the support of key people within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (and to a lesser extent the Ministry of Defence).

[W]hat happened was that there were a couple of young women … they convinced their bosses and people who were at a higher level in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. … They found some allies in the bureaucracy and then people within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs actually embraced the idea and decided to pursue it. (Interviewee 1)

This was particularly due to the support given by one mid-level woman in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs who provided leadership and mobilisation for the NAP. Initially sceptical, she became ‘convinced’ (Interviewee 2) of the importance of the agenda and ‘championed this process through which the NAP … became really a state process’ (Interviewee 4).

Interviews also stressed the importance of these critical actors who were ‘strategically engaged with each other and with strategic people’ (Interviewee 1), often creating channels of communication that bypassed official government meetings. One interviewee described how she would meet privately with another interviewee prior to official government meetings in order to ensure that they would present a united front:

[W]e would pretend we were not friends … she would come to me and say, ‘Look. [Government Agency] is going to say no to this, this, this and this’ and then we would prepare together – the day before [in order to counteract their arguments against changes to the NAP] (Interviewee 2)

In sum, the force behind the NAP was a small group of committed individuals, with little concerted will on the part of the Brazilian government.

Similarly, a handful of individuals were responsible for initiating and producing Poland's NAP. Following engagement with the WPS National Focal Point Network and Poland's membership of the UNSC, the reaction towards the creation of a Polish NAP from the Director of the Security Policy Department was described as ‘We have to do it. We have to have it’ (Interviewee 6). Work on developing the NAP then followed throughout April/May 2018 before consultation with ministries later than year. Rather than it being a centralised governmental commitment to the principles underpinning 1325, critical actors and networks at the international level proved instrumental in facilitating the creation of the Polish NAP.

This activity and engagement in supporting liberal international norms and agendas, as distinct from the domestic political context, is described by one interviewee below.

The Polish Permanent Mission to the United Nations is pretty progressive … while they were in the Security Council, they would raise issues related to women's participation, the protection of women in the conflict in Yemen, let's say, or in Syria, but then domestically, it doesn't so there is a difference. I think part of it might be very cynical thinking, it's just projecting yourself and hoping no-one will look at what's happening at home, but I think sometimes it's also driven by individuals. (Interviewee 7)

Discussion

From a comparison of the two case study countries, two main themes emerge.

1. Institutional arrangements are important to understanding NAP creation and content

Critical actors or ‘femocrats’Footnote 72 inside and outside the state institutions were key to the process of producing the NAPs in these two countries. This was particularly the case in Brazil where a handful of individuals (including one or two more senior figures) within key Ministries and civil society were central to championing the progress of the NAP. In the Polish case, the presence of key actors pushing for a NAP within state institutions and armed services, alongside civil society actors, existed pre-2015. However, it was only in response to international pressure and expectations, particularly given Poland's membership on the Security Council and NATO membership, that the process of developing a NAP gained wider institutional support. The role that a very small number of people played in both NAPs’ creation is an important understanding to be added to the WPS literature, illustrating the relative contingency of the agenda in these states. From the outside, the production of a developed NAP may suggest a vibrant culture for WPS within the workings of the state and a clear commitment to the agenda. The focus on the institutional progress of the NAPs that this article has given suggests instead that the agenda's progress has in fact been very tentative in both countries and has hinged on a small number of ‘femocrats’.

The militarisation of WPS has long been establishedFootnote 73 and it is therefore unsurprising that the agenda arrived in both countries largely through a focus on their militaries (and, in the case of Poland, via their military alliance with NATO). This encourages military involvement and a focus on women in the military, which in turn inhibits CSO involvement. This is particularly the case in these two countries given the role that the military inhabit in the context of post-communist/post-dictatorship contexts. The findings from this research therefore show that the militarisation of the WPS agenda impacts not only the content of the NAP, but also the institutional environment in which they are produced, with civil society less likely to take interest in the agenda when a key policy focus is on the military.

In demonstrating the importance of the institutional context in these two settings, the utility of FI for work on WPS has also been shown. As previously stated, the majority of work on NAPs has focused on their content as opposed to their production. Yet, as shown here, a textual analysis of NAPs can only go so far. FI allows us to think more closely about their development, their contingent arrival, and about the particular influences within the state (in these cases, the military) that might shape the agenda's focus as it moves from the realm of abstract Security Council Resolutions, to concrete domestic policy. As a framework, its adoption may be useful for further areas within feminist IR.Footnote 74

2. WPS has a ‘ritualistic’Footnote 75 and symbolic element

As the above has shown, the NAPs themselves are largely unexciting documents. They forward a liberal feminist perspective on WPS, which focuses on increasing women's representation in military and peacekeeping forces. They are weak in terms of their monitoring and implementation, and ability to assign a clear budget to WPS aims. Both have also had little CSO involvement in the process of their creation and do little to encourage that moving forwards. The lack of measurable targets and specific aims in both documents creates a picture of them as tickbox exercises, lacking innovation or sustained engagement with the agenda.

The NAPs produced are also largely the result of external pressure. In the Polish case, movement on the NAP appears to have come largely via the encouragement of NATO and the application for UNSC membership. In Brazil, there appears to have been a greater role for domestic critical actors, but action taken on the part of the key Ministries was instigated in part by promises made on the UN stage. Again, this is also reflected in the incredibly limited domestic CSO involvement in each country, and the very small role they appear to have had in encouraging uptake of the agenda. Neither context saw sustained or detailed engagement with civil society in the writing of these policies. It is also seen in the low awareness and interest there seems to be in WPS in both contexts, related to the militarisation of the agenda discussed above, and the relative inattention given to adapting WPS to suit domestic needs, rather than a pre-existing international script.

WPS thus appears attractive to these governments because it gives them symbolic clout on the world stage and in the context of their role within transnational bodies such as NATO and the UN. Interviews stressed that engagement with the WPS agenda and the development of a NAP were seen as key to unlocking access to the global political stage for these countries. This reduction of WPS to a simple foreign policy tool has been remarked in Western contexts,Footnote 76 but this is an interesting finding here given the anti-gender bent of the current administrations in both countries. The fact that they feel it necessary to engage with the WPS agenda in spite of its normative basis suggests that there is a flexibility and realism to their otherwise loud opposition to ‘gender ideology’. In some ways, this demonstrates an awareness that exists already in the literature that WPS can be co-opted to other ends. Indeed, while supporting the transformative potential of WPS, interviewees also acknowledged how the agenda can easily be reframed and co-opted away from its progressive and pacifist origins:

While I stand by the interpretation of the Resolutions as very progressive and they can in fact be used by women to very progressive ends, in themselves they do not include language that would be inflammatory in the same way that the definition of gender and the definition of family in the Istanbul Convention is for the anti-gender movement. So I think it's really because of that, and while Women, Peace and Security yields itself to more progressive interpretation, it does also yield itself to the very narrow interpretation of, ‘This is about how many women we have in the military’, and that's something you can sell more easily even to the most conservative circles (Interviewee 7).

While this is clearly seen in the cases of both Brazil and Poland, the context of these NAPs also goes much further. What is seen here is not only the narrowing of WPS to a simple focus on the military, but also an employment of WPS in states where governments are rolling back gender equality and are often actively resisting the very concept of gender itself. The fact that governments who have relapsed on domestic gender equality initiatives can still be associated with WPS in terms of their foreign policy has worrying implications for the agenda's global development. If, as we have seen, it can be used in a piecemeal and limited fashion by these states, yet they still gain through their association with it, this suggests that the aims of the agenda have been hollowed out.

Furthermore, much of the existing literature on anti-genderism highlights the technocratic and elitist tendencies of international commitments in enforcing gender mainstreaming at a domestic level. In this case of foreign policy, the process of NAP creation in Brazil and Poland can also be viewed as a technocratic exercise. Rather than reaching its transformative potential, or even aiming at funding or resourcing its commitments, in both cases WPS has been narrowly defined and, as a result, has proved relatively uncontroversial at the domestic level. Having a NAP has become a symbol/signifier of progress, with little actual commitment required on the part of states, allowing them to play their part in the liberal international system while simultaneously espousing anti-gender discourse and policy domestically.

As a result, the development of NAPs complicates the idea of gender ‘backlash’ that has been a strong trend in literature on Poland and Brazil (and elsewhere). Although much academic literature has focused on the anti-gender movements in both countries as an example of ‘backlash’ against gender equality and liberal ideas, many others have called into question the overly simplistic narrative that the term encourages.Footnote 77 In the case of WPS we see both Poland and Brazil promoting women's inclusion in a liberal fashion, particularly in relation to military recruitment. Thinking about WPS in these countries shows again that we need to complicate the understanding of ‘backlash’ in each, with this research adding in an international and foreign policy component that is under considered in other literature. Like David Paternotte argues, a narrow focus on ‘backlash’ does not allow us to see the ‘wider project’ in which these policies exist.Footnote 78 While women's rights are definitely regressing in some areas of (largely domestic) policy in these countries, in others, such as WPS and the NAPs, they seem to be uncontested and, in fact, promoted.Footnote 79 Again, states’ willingness to address gender equality in their foreign policy while largely deriding it in their domestic policy suggests that gender equality (and WPS) carries a certain symbolic function on the global stage that it does not at home. If states want to enter certain key international arenas and to improve their standing in global relations, they must work with this agenda even if it runs counter to much of their other intents. Discussions of gender ‘backlash’ are therefore too simple – states are willing to adopt different (indeed almost contradictory) attitudes to gender in different locales if it helps to further their interests.

Conclusion

In recent years both Brazil and Poland have elected governments that espouse homophobic and sexist agendas, and which contain key figures who have contested the very idea of gender itself. They have taken regressive measures around gender equality, including limiting access to abortion and restricting LGBTQ+ rights. Yet both have also continued to engage with the WPS agenda, a measure that promotes not only gender equality but does so in concert with the international liberal community that has also been vilified by both states. This article has gone some way to explaining how we can understand this paradox.

Firstly, it has shown that the institutional context in which a NAP is created is important. Both NAPs were the result of a small group of individuals, often facing resistance and obfuscation on the part of either government. The military context in which the WPS agenda emerged in both countries was important, in that it acted to inhibit civil society's involvement and to encourage a narrow focus in both contexts on women's inclusion in the military. Secondly, it has shown that the attraction of a NAP lies in part in the perceived soft power that it gives these states on the world stage. NAPs are adopted even when this runs counter to a state's domestic discourse on both gender and multilateralism, suggesting that gender equality carries a certain weight and importance for the international community that necessitates it engagement – as one interviewee put it, giving states access to a ‘VIP club’. As such, even if the content of a NAP goes against the government's stance domestically, its interest in the WPS agenda can still be explained. This complicates the oft-cited idea of a ‘backlash’ or regression around gender, as states adopt different attitudes in different areas.

In making the above arguments, the article has shown that NAPs need to be understood as products of the political and structural context from which they emerge. Viewing them only as completed documents misses important understandings of how they came to be, how states understand them, why they focus on particular areas and how work around the agenda develops (or doesn't) after their publication. It has done so through a FI framework, illustrating the utility of such a mechanism for work on WPS. As stated previously, much work on WPS has hit an impasse around its sense of the co-optation of the agenda. An FI framework allows a way out of this, showing the ‘small wins’ that occur within the ‘black box’Footnote 80 of the state and the complex journeys that NAPs take in the course of their production. As such, this article may suggest a blueprint for FI and further work within WPS scholarship or feminist IR more broadly.

This article has also highlighted future areas of interest for scholarship on the WPS agenda. The particular circumstances of Brazil and Poland's recent past warrant more attention than this article can afford – future research might be interested to think about the different trajectories that WPS has taken across states who have transitioned from authoritarian governments, the legacies this has left, and the impact they have on the agenda's development. Future work might also connect this to the developing literature on the ways in which autocratic and dictatorial states selectively leverage women's rights for their own gains.Footnote 81 Equally, this article has explored contexts in which NAPs have been developed in spite of anti-gender governments. Future research might also think about other similar contexts where NAP development has not occurred, for example Hungary.

Acknowledgements

We thank the UK Political Studies Association for their support for this research via a grant from the 2021 PSA Research and Innovation Fund. Jennifer Thomson is funded by the ESRC, grant number ES/V016407/1. Thanks to Hilde Coffé, Micha Germann, Kateřina Vráblíková, Ana Catalano Weeks, and Iulia Cioroianu who all read and provided extensive feedback on an earlier version of this article. Thank you also to Marta Rawłuszko and Weronika Grzebalska for discussions that helped us in framing the article. For the purpose of open access, the authors have applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising.

Dr Jennifer Thomson is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Politics, Languages and International Studies at the University of Bath. Author's email: j.thomson@bath.ac.uk

Dr Sophie Whiting is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Politics, Languages and International Studies at the University of Bath. Author's email: s.whiting@bath.ac.uk