I have nothing to do with addiction, I deal with the fight against drugs, in this fight I confiscate their opium, I tear up their coupons; now whatever the government intends to do is none of my business.

Introduction

‘Give me three months and I will solve the problem of addiction in this country’, declared the newly appointed head of the Anti-Narcotics Bureau in Tehran, Ayatollah Sadegh Khalkhali on the eve of the victory of the Islamic Revolution.Footnote 1 The ousting of the Shah and the coming to power of the revolutionaries had profound effects on the ideas, policies and visions that the Iranian state had vis à vis illicit drugs and addiction. Narcotics, in the eyes of the revolutionary state, did not simply embody a source of illegality, physical and psychological deviation and moral depravity, as was the case for the Pahlavi regime during its prohibitionist campaigns. Narcotics were agents of political and, indeed, counter-revolutionary value/vice to which the new political order had to respond with full force and determination. In times of revolution, there was no place for drug consumption. Criticism against the previous political establishment – and its global patron, the United States – adopted the lexicon of anti-narcotic propaganda; the idea of addiction itself, in some ways similarly to what had happened during the 1906–11 Constitutional Revolution, implied sympathy for the ancien régime of the Shahs and their corrosive political morality.

Under this rationale the period following 1979 saw the systematic overturning of policies laying at the foundation of the Pahlavi’s drug control strategy in the decade preceding the revolution. But it would be incomplete to describe the developments over the 1980s as a mere about-face of previous approaches. The Islamic Republic undertook a set of interventions that speak about the intermingling of drugs and politics in the context of epochal events in Iranian history, especially that of the eight-year war with Iraq and the transition from revolutionary to so-called pragmatic politics. This chapter explores the techniques that the revolutionary state adopted to counter the perceived threat of narcotic (ab)use and drug trafficking. Three major moments characterise this period: the revolutionary years (1979–81), the war years (1981–8) and the post-war years (1988–97).

Tabula Rasa: the Islamic Paladin Ayatollah Sadegh Khalkhali

On 27 June 1979, Ayatollah Khomeini declared, ‘drugs are prohibited’;Footnote 2 their trafficking, consumption and ‘promotion’ were against the rules of Islam and could not take place in the Islamic Republic. This ruling, although informal in nature, sanctioned a swift redirection of Iran’s previous approach to narcotic drugs, in terms of both control and consumption. As had happened in 1955, Iran seemed ready to go back to a policy of total prohibition and eradication of opiates, this time under the banner of Islam rather than that of the international drug control regime. It was not the concern of alignment with international conventions of drug control that guided the decision of the Iranian leaders, but rather the obligation to build a body politic detoxified of old habits, enshrined in a new ethics of sobriety in politics as well as in everyday life. This revolutionary vision had to come to terms with the existing programmes of opium maintenance and treatment started in 1969. What was going to be the lot of the registered opium users under the Pahlavi coupon system? In the zeitgeist of the first years of the revolution, between the return of Ayatollah Khomeini in February 1979 and the outbreak of the war in September 1980, the question acquired sensitive political value well beyond the technical considerations of medical management and opium production. Illicit drugs and their consumption reified a field of political contention and intervention, which went hand in hand with the legitimacy and vision of the newly established Islamic Republic and which would have lasting presence in its political transformation in later years.

On 25 August 1979, Iran’s interim president Mehdi Bazargan, who espoused a liberal orientation for the new political order, signed the ministerial cabinet act giving permission to registered opium users to purchase opium from the state at a fixed rate of thirty rials. The concession was meant to be an exceptional permission lasting for a period of six months, after which all opium users were required to kick their habit. Those who continued to use opium would have to rely on the black market and would be considered criminals. But given that Khomeini had already declared that the poppy had to be eradicated from all cultivated lands, the government allowed the Opium Transaction Organisation (Sazman-e mo‘amelat-e tariyak) – previously charged with the approval and provision of opium ‘coupons’ – to purchase a hundred tons of opium from India, a major legitimate producer of pharmaceutical opium.Footnote 3 Intended to assist those who had been under the previous regulated opium distribution system, the one-off transaction enabled the new political order to find alternatives in the field of drugs policy. Ayatollah Sadegh-e Khalkhali best emblematised the vision of this new model.

A mid-ranking cleric loyal to Ayatollah Khomeini prior the revolution, the Imam appointed Khalkhali as Iran’s first hakem-e shar‘, the leading state prosecutor. Just a few days after the victory of the revolutionary camp against the Shah, in mid-February, Khalkhali had taken up the demanding post of Islamic Robespierre.Footnote 4 Unsettled by the burdensome appointment, Khalkhali wrote to Khomeini, ‘I am thankful, but this job has blood and it is very demanding … I fear that my name [‘face’, chehreh] in the history of the revolution will be stained in blood and that the enemies of Islam will propagate [stories] against me, especially since I will need to judge the perpetrators of vice and corruption and crime in Iran’.Footnote 5 The assessment of his predicament, indeed, was correct, and Khalkhali’s name remained associated with the reign of terror of the revolution. As the supreme judge heading the Revolutionary Courts, Khalkhali fulfilled the task of annihilating the old guard of the Pahlavi regime in a reign of terror that also represented the cathartic moment of the revolution. What often goes unmentioned is that at the same time Abolhassan Bani Sadr, Iran’s first elected president, nominated Khalkhali as the first head of the Bureau of Anti-Narcotics.Footnote 6 Prohibition of drugs (and alcohol) became a new religion, with its punitive apparatuses of inquisitions. Khalkhali’s duty as Iran’s drug tsar lasted less than one year, but its effects were historically and genealogically profound.

Under Khalkhali, Iranian authorities eradicated the poppy crop for the first time in the country’s modern history. The endeavour, promised at different historical stages equally by Iranian Constitutionalists, anti-drug campaigners, the Shah and the United States, was eventually carried out with no international support in a matter of two years. After having called on producers to cultivate ‘moral crops’ such as wheat, rice and lentils, the authorities banned opium production on 26 January 1980.Footnote 7 Khomeini declared ‘smuggling’ and ‘trafficking’ haram, a statement which had no precedent in Islamic jurisprudence, and which signalled a shifting attitude and new hermeneutics among the clerical class.Footnote 8 Along with him, prominent clerics expressed their condemnation of drug use in official fatwas. Up until then Islamic jurisprudence had remained ambivalent on opium, maintaining a quietist mode of existence about its consumption.

Khalkhali personally oversaw the files of the convicted drug offenders in collective sessions. In several instances, charges against political opponents were solidified with accusation of involvement in drug dealing or drug use, thus making manifest the narratives, mythologies and suspicions that had characterised anti-Shah opposition during the 1970s. For instance, the prosecutors accused the leftist guerrilla movement of the Fadayan-e Khalq of harbouring massive amounts of opium (20 tons), heroin (435 kg) and hashish (2742 kg) in its headquarters, a finding that led to the execution (and public delegitimation) of the group apparatchik.Footnote 9 Similarly, high-ranking officials of the previous regime were found guilty of mofsed-fil-‘arz, ‘spreading corruption on earth’, a theological charge that contemplated as its prime element the involvement in narcotics trafficking, drug use and broadly defined ‘debauchery’.Footnote 10

Within this scenario, one can locate the role of revolutionary tribunals, heir to the Shah’s military tribunals, now headed by Khalkhali in the purification process. These courts judged drug cases together with crimes against the state, religion and national security, as well as those of prostitution, gambling and smuggling. Revolutionary courts brought public executions and TV confessions to prominence and into the societal eye as a means to legitimise the new political order and deter deviance from it. Khalkhali’s role in this narrative was central: as head of the Anti-Narcotics Bureau he was a regular presence in the media, with his performance being praised for its relentless and merciless engagement against criminals. On special occasions, he would personally visit large groups of drug addicts arrested by the Islamic Committees and Gendarmerie and gathered in parks and squares. Those arrested had their hair shaved in the middle and on the sides of the head, a sign of humiliation in a manner combining pre-modern punishment with modern anti-narcotics stigmatisation. A person’s appearance as a ‘drug addict’ would land him/her a criminal charge, with confiscation of drugs not being strictly necessary for condemnation. In video footage taken during one of Khalkhali’s visit, a man, one of the arrested offenders, says, ‘I am 55 years old and I am an addict, but today I was going to the public bath – everyone knows me here – I had no drugs on me, I was taken here for my appearance [qiyafeh]. No to that regime [the Pahlavi]! Curse on that regime, which reduced us to this’.Footnote 11 His justification hints at two apparently inconsistent points: he pleads guilty to being an addict, but also a person who did not commit any crime on that day; and he puts the burden of his status on the political order that preceded Khalkhali’s arrival, that of the Pahlavis.

The fight against narcotics and, in the rhetoric of this time, against its faceless patrons of mafia rings, international criminals and imperialist politicians produced what Michel Foucault defined in Discipline and Punish ‘the daily bulletin of alarm or victory’, in which the political objective promised by the state is achievable in the short term, but permanently hindered by the obscure forces that undermine the revolutionary zeal (Figure 3.1).Footnote 12 As an Islamic paladin in a jihad (or crusade) against narcotics, Khalkhali applied heavy sentences, including long-term incarceration and public execution, against drug traffickers involved at the top and bottom of the business hierarchy. He also targeted commercial activities involved, laterally, in the trade, including truck drivers, travellers’ rest stations (bonga-ye mosaferin), coffeehouses, and travel agencies.Footnote 13 Confiscation of the personal possessions of the convicted to the benefit of the law enforcement agencies or the Foundation of the Addicts (bonyad-e mo‘tadan) was standard practice. The Foundation, instead, dispensed the funds for detoxification programmes and medical assistance, most of which had a punitive character.Footnote 14 Albeit celebrated by some, Khalkhali’s modus operandi fell outside the legalistic and procedural tradition of Islamic law, especially regarding matters of confiscation of private property and the use of collective sentences. To this criticism, however, he responded with revolutionary zeal: ‘On the Imam’s [Khomeini] order, I am the hakem-e shar‘ [the maximum judge] and wherever I want I can judge!’Footnote 15

Again, as in 1910s and then 1950s, the Iranian state preceded American prohibitionist efforts and their call for a War on Drugs. It was under the fervour of the Islamic revolution and the challenge to extirpate, in the words of public officials, ‘the cancer of drugs’, that Khalkhali undertook his mission. Counter-intuitively, this call anticipated the US President Ronald Regan’s pledge for a ‘drug free world’ in the 1980s. Anti-narcotic and reactionary religiosity animated the ideology of the Iranian and the American states, though at different ends of the spectrum.

On the occasion of the execution of a hundred drug traffickers, Khalkhali declared: ‘I have nothing to do with addiction, I deal with the fight against drugs, in this fight I confiscate their opium, I tear up their coupons; now whatever the government intends to do is none of my business’.Footnote 16 Yet, his undertakings did not go without criticism; widespread accusations of corruption among his anti-narcotic officials and ambiguity over the boundaries of his powers tarnished his image as an Islamic paladin. Allegations of torture against drug (ab)users and mass trials with no oversight cast a shadow on the other side of ‘revolutionary justice’.Footnote 17 On May 12, 1980, three months after his appointment, Khalkhali submitted his resignation, which was initially refused by then-president Bani Sadr, who had to clarify in the newspaper Enqelab-e Eslami what the ‘limits of Khalkhali’s duties’ were.Footnote 18 By December of that same year, however, Khalkhali resigned from his post amid harsh criticism from the political cadres and fear throughout society.Footnote 19

His methods had broken many of the tacit and explicit conventions of Iranian culture, such as the sanctity of the private space of the house and a respectful demeanour towards strangers and elderly people. His onslaught against drugs, initially welcomed by the revolutionary camp at large, terrorised people well beyond the deviant classes of drug (ab)users and the upper elites of the ancien régime. Traditional households, pious in the expression of their religiosity as much as conservative in respect of privacy and propriety, had seen anti-narcotic officials intervening in their neighbourhoods in unholy and indignant outbursts. The disrespect of middle class tranquillity animating Khalkhali’s anti-drug campaign prompted Khomeini’s intervention on December 29, 1980. Aimed at moderating the feverish and uncompromising tone and actions of his delegate judge, Khomeini stated: ‘Wealth is a gift from God’ in a major public updating of revolutionary fervour. The eight-point declaration had to set the guidelines for the new political order:

Law Enforcement officers who inadvertently find instruments of debauchery or gambling or prostitution or other things such as narcotics must keep the knowledge to themselves. They do not have the right to divulge this information since doing so would violate the dignity of Muslims.Footnote 20

This statement also coincided with the dismissal of Khalkhali as head of anti-narcotics and the appointment of two mid-ranking clerics in his stead. The means of eradication of narcotics shifted with Khalkhali’s withdrawal from the drug battle. It also contributed a change in the phenomenon of illicit drugs.

The Imposed Wars: Iraq and Drugs (1980–88)

The Iraqi invasion of the southwestern oil-rich region of Khuzestan exacerbated the already faltering security on the borders, leaving the gendarmerie and the police in disarray. Easier availability of illicit drugs coincided with a qualitative shift. The trend that had started during the 1960s, which had seen upper-class Iranians acquiring a taste for heroin, was democratised in the years following the revolution, also as an effect of urbanisation. Despite Khalkhali’s total war on drugs, his means had remained ineffective and fragmentary, and his strategy relied on fear and the unsystematic searches for drugs. The prospect of eradication of illicit drugs in this ecology, with opium geographically and historically entrenched, was unrealistic. It soon coincided with the spread of heroin within Iran’s borders.

With tougher laws on drug trafficking, heroin had a comparative advantage on opium and other illegal substances. It was harder to detect both as a smuggled commodity and as a consumed substance. It guaranteed a much higher return on profits with smaller quantities, with European markets keeping up the demand for all the 1980s. Clinical records from this period point at a generational, geographical shift in the phenomenon of drugs: a majority of younger urban-origin (including recently urbanised) groups shifted to heroin smoking, with rural elderly people maintaining the opium habit.Footnote 21 In the absence of reliable data, this shift suggests a fall in the cost of heroin, whereas prior to 1979 heroin had remained an elitist habit. On the eastern front, the insurgency in Soviet-occupied Afghanistan had resulted in skyrocketing poppy production, with very large quantities of opium and refined heroin making their way through Iran. The sale of opiates across the world, and their transit through Iran, financed the mujahedin fight against the Red Army, a business model allegedly facilitated by the CIA in a bid to bog down the Soviet Union into a new Vietnam. Without adequate intelligence and with the bulk of the army and volunteer forces occupied on the Western front against Iraq, Iran’s War on Drugs had to rely on a different strategy.Footnote 22

By end of 1981, the Islamic Republic faced several crises: the invasion of its territories by Iraq (September 1980), the US embassy hostage crisis (November 1979–January 1981), the dismissal of the elected president Bani Sadr (June 20, 1981), and the concomitant purges carried out by Ayatollah Khalkhali since 1979. Heroin was not top on the agenda of the revolutionaries, but, by the 1980s, it turned into a visible trait of urban life. Its devastating effects were undeniable in the post-war period.

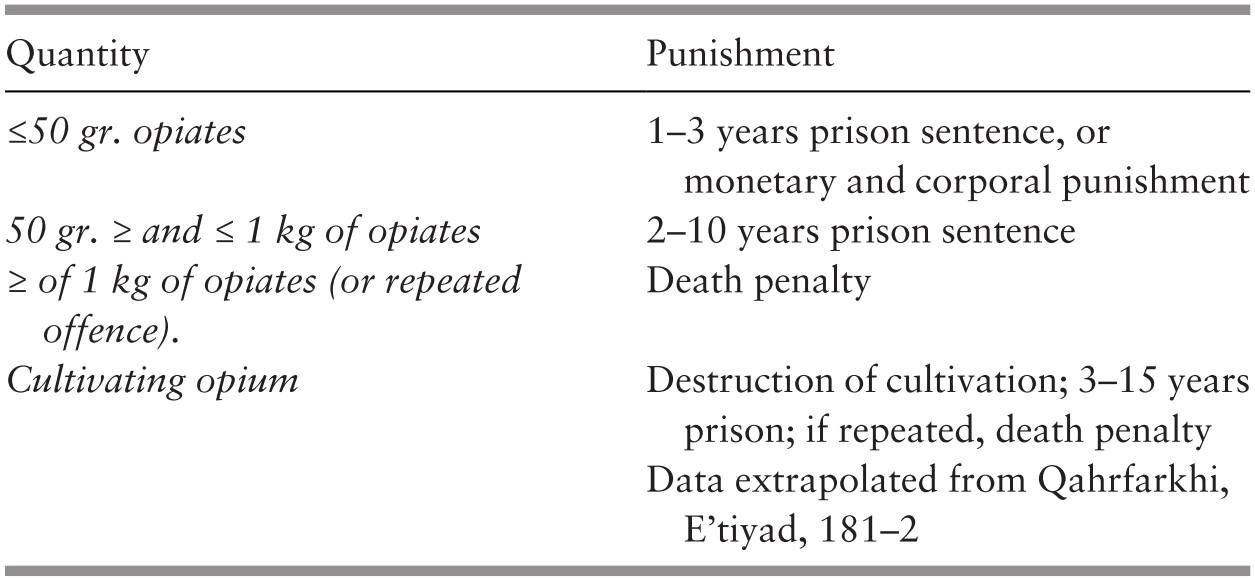

The authorities could not establish a new moral order free of narcotics. Hence, they recalibrated their focus towards the war and clamped down on political deviancy. Vis-à-vis drugs, the government’s rationale became governing the crisis through different sets of techniques. These techniques intermingled with those of the war front, buttressing the interpretation of the anti-narcotic fight as a second ‘imposed war’ (jang-e tahmili), the first one being Saddam Hussein’s invasion backed by imperialist forces. The Central Islamic Committee formulated the legal framework of both the war against Iraq and the war against drugs in November 1981 (Table 3.1). The Committee assigned the duty of drug control programmes to ‘Headquarters’ (setad) and their regional representatives, operating in direct contact line with the government executive. The law punished possession of quantities over one kg of opiates by the death sentence, even on the first offence; then it applied the death sentence also for minor repeated offences (more than three offences). Addiction, per se, was a criminal offence even without possession of drugs, a legal interpretation object of polemics up until the late 2010s.

Table 3.1 Punishment According to the 1980 Drug Law

This period also brought with it the imprimatur of later years and, as such, has genealogical value. Repressive practices of drug control did not terminate suddenly; instead, a shift in their practice occurred under different disciplining priorities: keeping addiction ‘out of the public gaze’; mobilising societal elements in the fight against narcotics; integrating the rhetoric of conspiracy and suspicion into the war on drugs. One could see this shift as the transition from revolutionary zeal in favour of republican means.

The Quarantine

Once the six-month period allowing drug users to kick their habit came to an end, the priority became ‘to prevent addiction from being visible from the outside and from becoming a showcase [vitrini]’.Footnote 23 Governing the crisis of drug use – and the management of public disorder – occurred through the quarantine. Hojjatoleslam Zargar, Khalkhali’s successor at the head of the Anti-Narcotics Bureau, remarked that ‘when arrested, the addict is considered a criminal and punished; then he is hospitalised and put under treatment and also condemned’.Footnote 24 This combination of incarceration and forced treatment could be observed in the massive entry of drug (ab)users into the penal/welfare system. The number of people arrested for drug (ab)use increased from 19,160 in 1982 to 92,046 in 1988.Footnote 25 The authorities set up state-run labour and detoxification centres across the country, some with the capacity to take in thousands. Conceived with little scientific acumen or medical knowledge, these centres forced interned people to work on land-reclaiming projects, construction sites and other manual activities while detoxifying. Their effectiveness would often depend on the skills and personality of the management cadres, driven mostly by amateur devotion rather than experience in treating addiction. Shurabad, located in southern Tehran, was to be the model of these centres. Here, lectures in ‘Islamic ideology’, sessions of collective prayer and forced labour would occupy the period of internment, which could last up to six months. Accounts of violence were numerous, with an unspecified, but considerable, number of deaths.Footnote 26

Quarantine was also carried out through other techniques, the most emblematic being that of the ‘islands’. Drug (ab)users, especially the poor and homeless, would be sent to unpopulated islands in the Persian Gulf, the jazirah.Footnote 27 Under extremely difficult physical and psychological conditions, they were forced into outdoor manual labour, in the desolated landscapes of the south. This ‘exile’ – indeed, the southern coast had been used in lieu of exile in modern Iranian history – enabled the authorities to cast off from the public space those unaligned with the ethical predicaments of the Islamisation project.

Quarantining drug (ab)users preserved the façade of moral purity and social order dear to the Islamist authorities and had also the objective of instilling fear into all drug consumers. Yet, by 1984, rather than a decline in drug use, categories hitherto thought of as pure and untouched by drugs seemed to be involved in it. In Mashhad, the local authorities inaugurated the first Women’s Rehabilitation Centre, while several hospitals across the country opened ad hoc sections for children dependant on opiates.Footnote 28 This would often come as a side-effect of the husband/father’s opium smoking and/or the consequences of arrests, which inevitably caused hardships on poorer families and the resort to illegal means of economic sustenance, such as drug dealing, smuggling, and sex work. The most affected geographical areas were Khorasan, Baluchistan and the southern districts of Tehran. There, widespread drug (ab)use coexisted with the dominant position of drugs in the economy and, consequently, with the devastating effect of anti-narcotic operations on the local population. Heroin consumption increased even in rural communities once known only for opium and shireh smoking. A small village in Khorasan, for instance, was reported to have ‘118 of 150 families addicted to heroin’.Footnote 29 The authorities associated public vagrancy with drug (ab)use, a feature of drug policy for the following decades. Several national campaigns against vagrants and street ‘addicts’ took place throughout the 1980s.Footnote 30 While solidarity with the mosta‘zafin (downtrodden) was expressed in the public discourse, the authorities were also eager to reorganise the public space, Islamising its guise, a process which did not tolerate the unruly, undisciplined category of the homeless.

Not all the efforts were detrimental to marginalised communities. A study of clinical access to addiction treatment carried out in 1984 in the city of Shiraz indicates that ‘government clinics, after the revolution, are now seeing a broader range of addicts than before’.Footnote 31 The rural population and working class men visited the public clinics in larger percentages than prior to 1979, suggesting that the revolution’s welfarist dimension had its inroads into the treatment of addiction too. Treatment was to some extent socialised over the 1980s, but this was potentially a consequence of the changing pattern of drug (ab)use – rise in heroin use – and of the pressure of state criminalising policies towards drug (ab)users. In other words, access to treatment among poorer communities came as part of the long-term effect of Khalkhali’s shock therapy. Although public deviancy – embodied by drug (ab)use – undermined the ethical legitimacy of the Islamic Republic, the narrative of narcotics fell within the local/global nexus of revolution and imperialism. In this nexus, world power, the global arrogance (estekbar-e jahani), plotted to undermine the Islamic Republic through the Trojan horse filled with drugs.

Drug Paranoia and the Politics of Suspicion

‘Everyday drugs and in particular heroin are designed as part of a long term programme by the enemies of the revolution, who through a wide and expensive network aim at making young people addicted’.Footnote 32 Thus read the first page of the newspaper Jomhuri-ye Eslami on August 5, 1986. The War on Drugs was the second chapter of the ‘Imposed War’, the name which the Iranian leadership had used to describe the conflict with Saddam’s Iraq. Not only held up by the upper echelons of power, the population at large espoused this interpretation of drugs politics. The alignment of US and Soviet interests – together with Europe and much of the rest of the world – in support of Saddam’s Iraq spoke too clearly to the ordinary people in Iran: the world could not accept a revolutionary and independent Iran. A grand geopolitical scheme depicted drug traffickers and their victimised disciples, drug users, as pieces of a global chess game masterminded by the United States and Israel.

The language used in reference to drug offenders (especially narcotraffickers) was eloquent: saudageran-e marg (merchants of death), saudageran-e badbakhti (merchants of misery), gerd-e sheytani (Satanic circle), ashrar (evils).Footnote 33 These went together with references to the conspiracy that worked against Iran’s anti-narcotic efforts: tout’eh-ye shaytani (diabolic conspiracy) and harbeh-ye este‘mari (colonial weapon).Footnote 34

The lexicon became an enduring feature of anti-narcotic parlance for years to come. There were certainly reasons for blaming international politics for the flow of drugs through Iran. With the Soviet Red Army involved in the Afghan war, the mujahidin took advantage of poppy cultivation as a profitable source of cash and people’s sole means of survival. Afghanistan became the leader in the opium trade, a position it still maintains uncontested. This trade moved through the territory of the Islamic Republic in alarming numbers – between 50 and 90 per cent of all opiates worldwide. In less than a decade, the price of heroin had decreased by five times in the streets of Tehran, establishing itself as a competitive alternative to opium.Footnote 35 Despite reiterated calls for stricter border control, the Iranian authorities were not able to divert their strategic focus eastwards until the end of the war. Geopolitical constraints made the central anti-narcotic strategy – based on supply reduction – in large part futile. Futility, however, did not mean irrelevance. Since the early 1980s, the Islamic Republic came top in opium and heroin seizure globally, an endeavour carried out against the grain of international isolation and lack of regional cooperation with opium producing countries such as Afghanistan and Pakistan.

By 1990, almost three million Afghans lived across Iran, many in Tehran and Baluchistan, both locations key to the drug network.Footnote 36 Of course, the social and ethnic networks connecting Afghan refugees with their social milieu across the border might have helped the smuggling of drugs (as everything else) into Iran. Poverty and lack of economic opportunities had their impact on the reliance of members of these communities on the political economy of the black market. Against this picture, Afghan refugees were object of sporadic episodes of suspicion which depicted them as ‘fifth column’ of international drug mafia aiming at destabilising the Islamic Republic.

The Baluch and the Kurds, both historically involved in the smuggling and illegal economy, including that of drugs, had a similar fate. The drug economy represented a major financial resource of their separatist agendas, which the government regarded with mistrust and open antagonism. For instance, in 1984–5 ‘of the 25,000 kg of drugs confiscated at the national level, 10,000 kg were seized in Sistan and Baluchistan alone’.Footnote 37 The flow of narcotics from the southeast prompted the government to install spatial security barriers between central Iran and regions bordering Afghanistan and Pakistan. The authorities built a security belt in the area of Kerman and across the surrounding desert, with several check points along the highway route. Military and intelligence was deployed to counter the drug flow, with limited success. Aimed at protecting Tehran from the influx of drugs, the barrier had to undercut revenues of those groups that opposed the central government. On the western border, a similar build up took place on the route through the Iranian Kurdistan region leading to Turkey. This spatial intervention localised the burden of the anti-narcotic combat along Iran’s geographical borders, which coincided in part with the ethnical and economic frontiers.Footnote 38

Popular Mobilisation against Illicit Drugs

The experience of the war against Iraq proved instrumental in the fight against narcotics. Revolutionary institutions and parastatal organisations provided a military dimension to the implementation of anti-narcotics operations, which brought in pasdaran (IRGC, aka revolutionary guards), appointees of Revolutionary Courts, basij forces (volunteers), and the many foundations that operated at the ambiguous margins of Iran’s state-led economy. The ‘call on duty’ of this decade also honed in on the narcotics combat. The propaganda machinery, tested with revolution and war, rolled fast on the topic of drugs too. Mosques had a primary role in this scheme. The fulcrum of moralisation programmes in neighbourhoods, they worked in close contact with the local Islamic Committees. In the case of arrests for ‘moral crimes’ (drug use, breach of gender code, gambling), the local committee would bring the offenders to the nearest mosque and, after an impromptu investigation, they could be taken to the Islamic court. State representatives held sermons in mosques, in particular during the officially sanctioned Friday prayers. For instance, in 1988 the national organisation of the Friday Prayers’ Leaders ‘signed a declaration in staunch support of the fight against drugs and the officials involved in the fight’ and called for the involvement of the clergy in the combat.Footnote 39 Pledging allegiance to the war on drugs was as important a duty as the obligation to support the troops on the Iraqi front.

The combat also developed real operational tactics; a number of military plans tackled both drug trafficking and public addiction throughout the national territory. The Revolutionary Guards and the Ministry of Interior conducted operation Val‘adiyat in the region of Hormozgan, which brought to justice ‘more than 2,400 addicts’.Footnote 40 Other operations involved naval units in the Strait of Hurmuz or security forces in urban centres, often with large deployments of troops.Footnote 41 The veneer as well as the structure of these plans bore profound similarities to the simultaneous military operations on the southwest border. Tactically, these operations did not rely exclusively on military personnel and regular forces. Instead, as has been a hallmark of the republican era, a large number of entities connected to parastatal foundations and local committees participated in the operations. The Basij-e Mostaza‘fin Organisation committed 500,000 volunteers to the war on drugs, with representatives being present (but perhaps not particularly active) across most of the urban and rural towns of the country.Footnote 42 Even in the urban fringes of the capital, such as the gowd, IRGC Committees had established councils and operational units where ‘the morally deviant elements in the community, e.g. gamblers and drug dealers, were identified and isolated’.Footnote 43

In the framing of the Islamic Republic leadership, the war on drugs was as existential an issue as the war against Iraq. President Ali Khamenei, echoing Khomeini’s slogan, circulated a statement pointing out that ‘the most important question after the war is the question of addiction’; his Prime Minister and later rival Mir Hossein Mousavi also stated, ‘we must give the same importance that we give to the war to the fight against drugs and addiction’.Footnote 44 After the resignation of Khalkhali, the anti-narcotics apparatus progressively shifted its focus to intelligence gathering, although this process did not fully materialise before the early 1990s. The Ministry of Information, the equivalent of intelligence and secret services, issued a communiqué to the public requesting full collaboration and information sharing about drug use and drug trafficking. It activated a special telephone number, the 128, and set up local mailboxes so that every citizen could contribute to the fight against narcotics. Newspapers published regular advertisements and distributed leaflets with slogans inviting people to stay alert and cooperate with the police regarding drug consumption.Footnote 45 This societal mobilisation produced a level of public engagement in that many families, whether under the influence of fearmongering propaganda or by the experience of ‘addiction’ in the lives of their cohorts, wanted to see the government succeed in the anti-drug campaign. Yet, it also had its counter-effects: collaboration with the authorities meant that discord and infighting could emerge within communities, where local jealousies, deep-seated hatreds or petty skirmishes could justify referral to the authorities with the accusation of drug (ab)use or drug dealing. To settle the score with one’s enemies, the catchall of ‘drugs’ proved instrumental. This also targeted the lower stratum of the drug market, with petty-dealers and ordinary users being identified instead of the bosses and ringleaders.

Mobilisation also meant that the military engaged in armed confrontation with the drug cartels that managed one of the most lucrative and quantitatively significant trades worldwide. Equipped with sophisticated weaponry and organised along ethnic, tribal lines – especially in the Zahedan region, along the border with Pakistan – drug traffickers would often outnumber and outplay the regular army units. When not confronting the army, traffickers would use un-manned camels loaded with drugs to cross the desert and reach a designated area where other human mules would continue the journey towards Tehran and from there to Turkey and Europe. The value of any drug passing an international border would double ipso facto.Footnote 46 Once stock reached the western border of Iran, it would be transferred via Iraq or Turkey towards richer European countries, with its value increased by a ratio of a hundred. The lucrative nature of this business made it extremely resilient and highly flexible in the face of any hindrance. Corruption ensued as a logical effect of the trade – as it has been the rule worldwide – and the Islamic Republic was no exception. In several instances, public officials were charged with accusations of drug corruption. The authorities did not take these accusations lightly, the punishment for collaboration with drug cartels being merciless, the death penalty for officials of higher ranking. In 1989, the head of the Anti-Narcotic Section of the Islamic Committee of Zahedan – the capital of opiates trafficking in Iran – was found guilty of ‘taking over 10 million [tuman] bribe from a drug trafficker’;Footnote 47 the head of the Drug Control Headquarters (DCHQ) in Mashhad, later in 1995, was judged for his ‘excessive violations in his administration’.Footnote 48 The Judiciary applied the maximum sentence. Both officials were hanged.

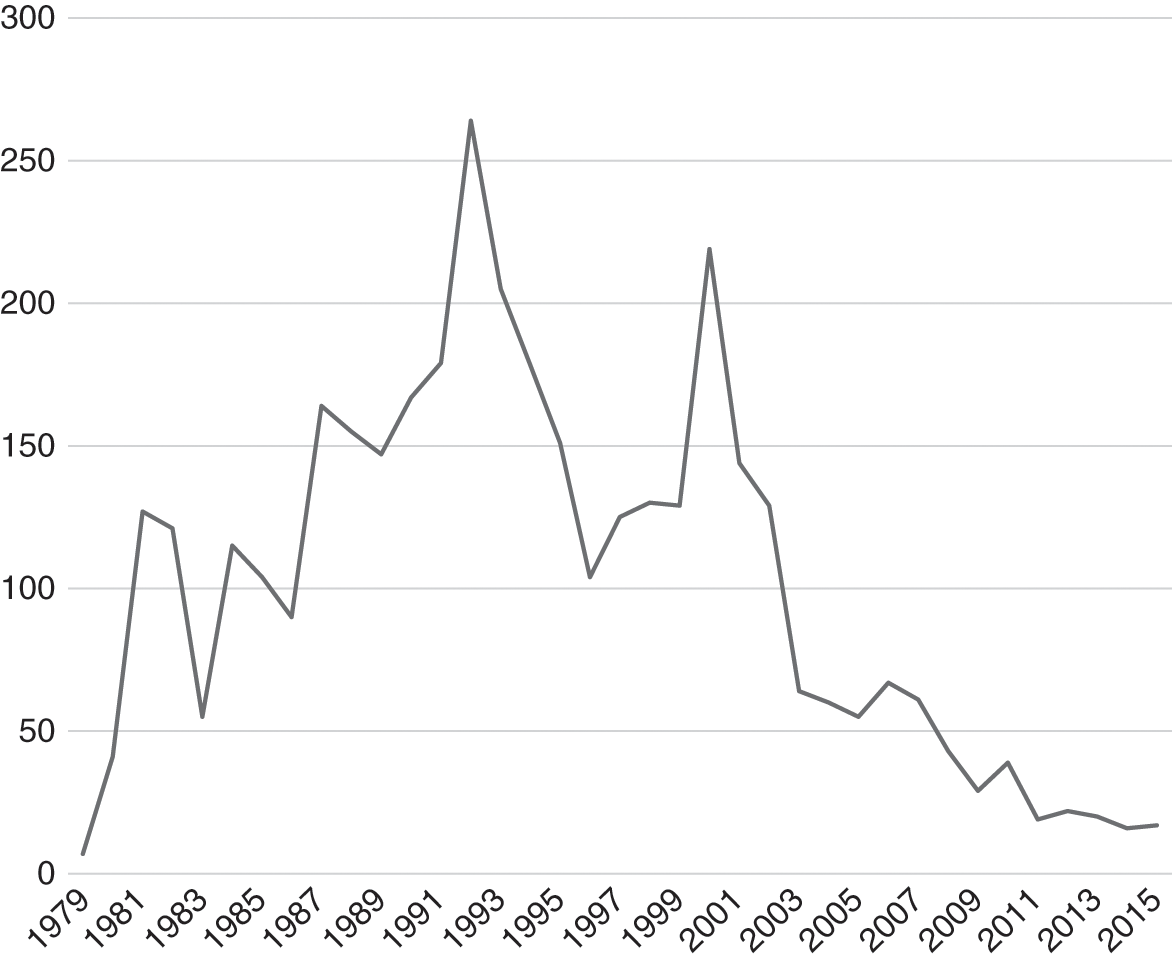

The Iranian state upheld its moral standing vis à vis these accusations by showcasing the human cost that its war on drugs had had since 1979. The number of soldiers and volunteers who lost their lives in anti-narcotic operations (or while on duty attacked by drug traffickers) increased from 7 in 1979 to more than 155 in 1988 and 264 in 1992. It steadily increased over the years of the Iran–Iraq War, reaching a maximum after the reforms of law enforcement in the early 1990s.

The government bestowed the title of ‘martyrs’, shahid, to all those who lost their lives on anti-narcotic duty (Figure 3.2). The families of the drug war martyrs had all the attached economic and social benefits that the title of martyr carried, approximately equivalent to that of the soldiers who fought and perished on the Iraqi front.Footnote 49 They entered the sacred semantic body of the Islamic Republic. While the Sacred Defence ended in 1988, the War on Drugs continued unhampered up to the present day, and with it the drug war martyrs, reaching a peak in the early 1990s, when narcotic combat topped the list of security priorities following the end of the Iran–Iraq War.

Figure 3.2 ‘War on Drugs’ Martyrs (per year)

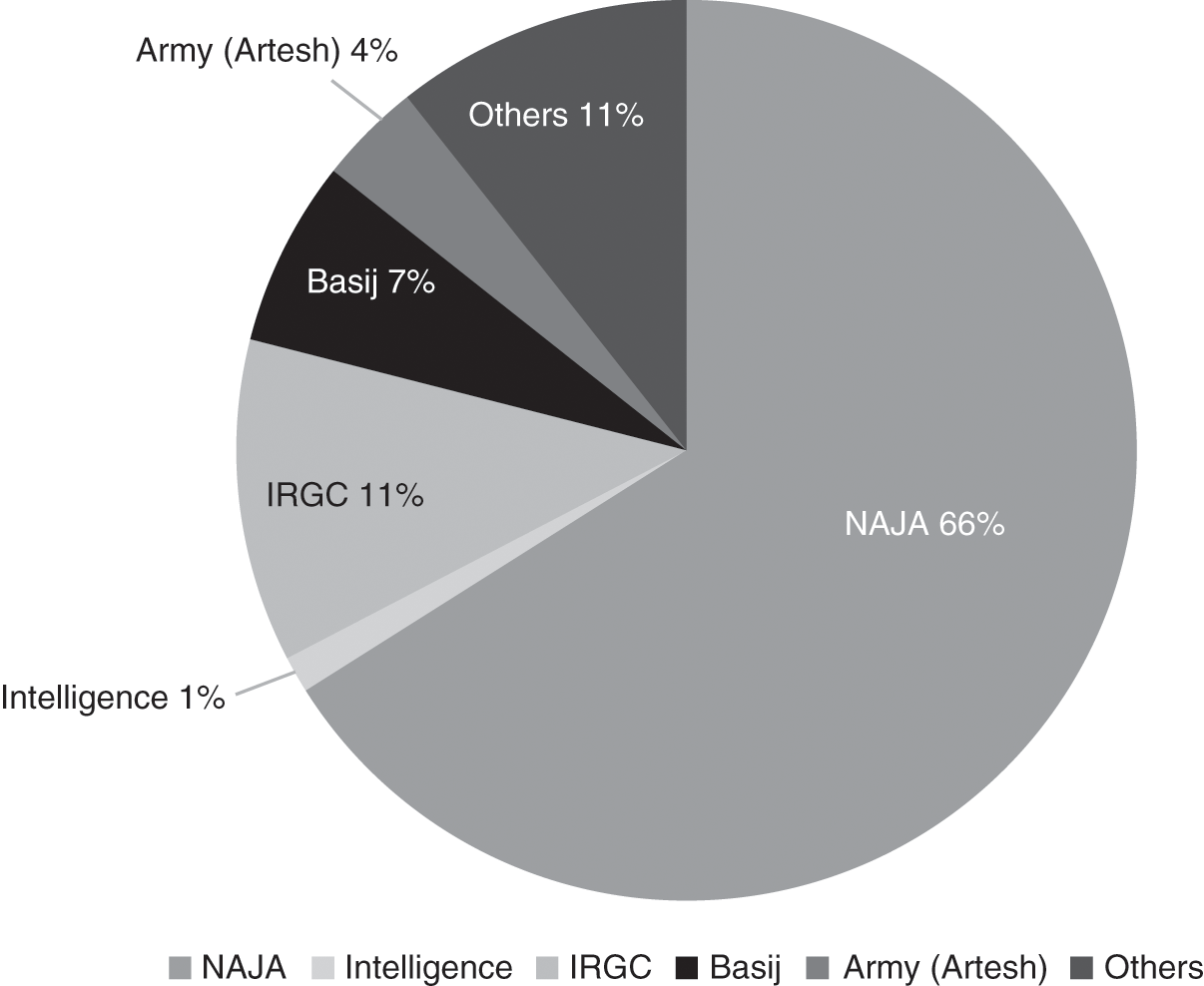

Of the 3,766 security and army members who perished between 1979 and 2015, the greatest share (66 per cent) is represented by the police (NAJA), followed by the IRGC and the Basij (both 11 per cent).Footnote 50 The numbers speak, in fact, of the mobilisation character of the ‘War on Drugs’, at least up to the mid 2000s. They also provide raw data on overall levels of drug-related violence in the Iranian context, which confirms that despite the four-decade War on Drugs, Iran has lower levels of violence when compared with other drug-torn contexts, such as 2010s Mexico, 2000s Afghanistan and 1980s Colombia (Figure 3.3).Footnote 51

Figure 3.3 ‘War on Drugs’ Martyrs

Although prevalent, the military/security mobilisation techniques operated alongside a number of more localised, civic and humanitarian initiatives that took place throughout the 1980s and indeed represented a first step towards broader programmes in the following decades. Here too, official and informal institutions worked alongside each other. The Construction Jihad (Jahad-e Sazandegi), for instance, launched autonomous programmes of treatment for female drug (ab)users and their children.Footnote 52 Islamic Associations (anjoman-e eslami) built large treatment camps across Tehran and other cities, often overlapping and exchanging patients with state-run centres mentioned above. The Komeyl Hospital was another important example. The hospital actively undertook addiction treatment under the financial support of twelve benefactors from the medical and scientific community. Patients received psychological support during detoxification, at the price of 12,500 rials. Without state support, the organisation relied on the patients’ contribution or the donations of sympathetic supporters.Footnote 53 Once the medical personnel considered the drug user recovered and stable, he (women were not admitted here initially), would be referred to the Construction Effort Organisation in order to find employment. In case of relapse, he would be sent to prison or a labour/treatment camp for imprisonment.Footnote 54 A system of treatment/punishment surfaced over the 1980s and connected a network of institutions, organisations, centres and people who belonged and did not belong to the state, allowing limited addiction treatment.

This coexistence of state and non-state support, at the fringes of legality, has an oxymoronic dimension, a feature that would fully develop in the following decades. This experience in the 1980s represented the genealogical ground for the models that materialise in the post-war period, at least in nuce.

After the War (1988–97): Policy Reconstruction and Medicalisation

With the end of the eight-year war against Iraq, the Islamic Republic entered a new phase of its politics, a period labelled ‘Thermidorian’ or ‘Second Republic’.Footnote 55 The Islamic Revolution of 1979 intertwined, intrinsically, with the ‘Sacred Defence’, bearing on the evolution of institutions and policies. Questions of political structure and constitutional legitimacy were put on hold for several years during the war, allowing for the adoption of short-term mechanisms of political management. It was not the end of war with Iraq – the war itself having been ‘normalised’ in the lives of Iranians (at least those living away from borders) – but the death of the Supreme Leader that represented the greatest moment of instability for the still-young Islamic Republic. A moment of unprecedented crisis, the political order faced its greatest challenge, for which, however, it had been prepared long before the event. Under the guidance of Khomeini himself, the leading figures of the state had taken a set of institutional measures to manage the post-Khomeini transition.

By the end of the war, the state moved from deploying the politics of religion to being more religiously political. End of the war also prompted the end of popular mobilisation targeted at an external threat (i.e. Iraq), and the need to refocus state formation towards domestic issues, including the rebuilding of infrastructures, of the war economy amidst low oil prices, and the redistribution of resources to those social classes who had selflessly supported the war effort. The coexistence of formal and informal institutions (e.g. the bonyad, the Islamic Committees), which had characterised the war years, needed readjustment for the necessity of post-war recovery.Footnote 56 Welfare policies and institutions had to be recalibrated and progressively formalised into readable bureaucratic and administrative machinery.

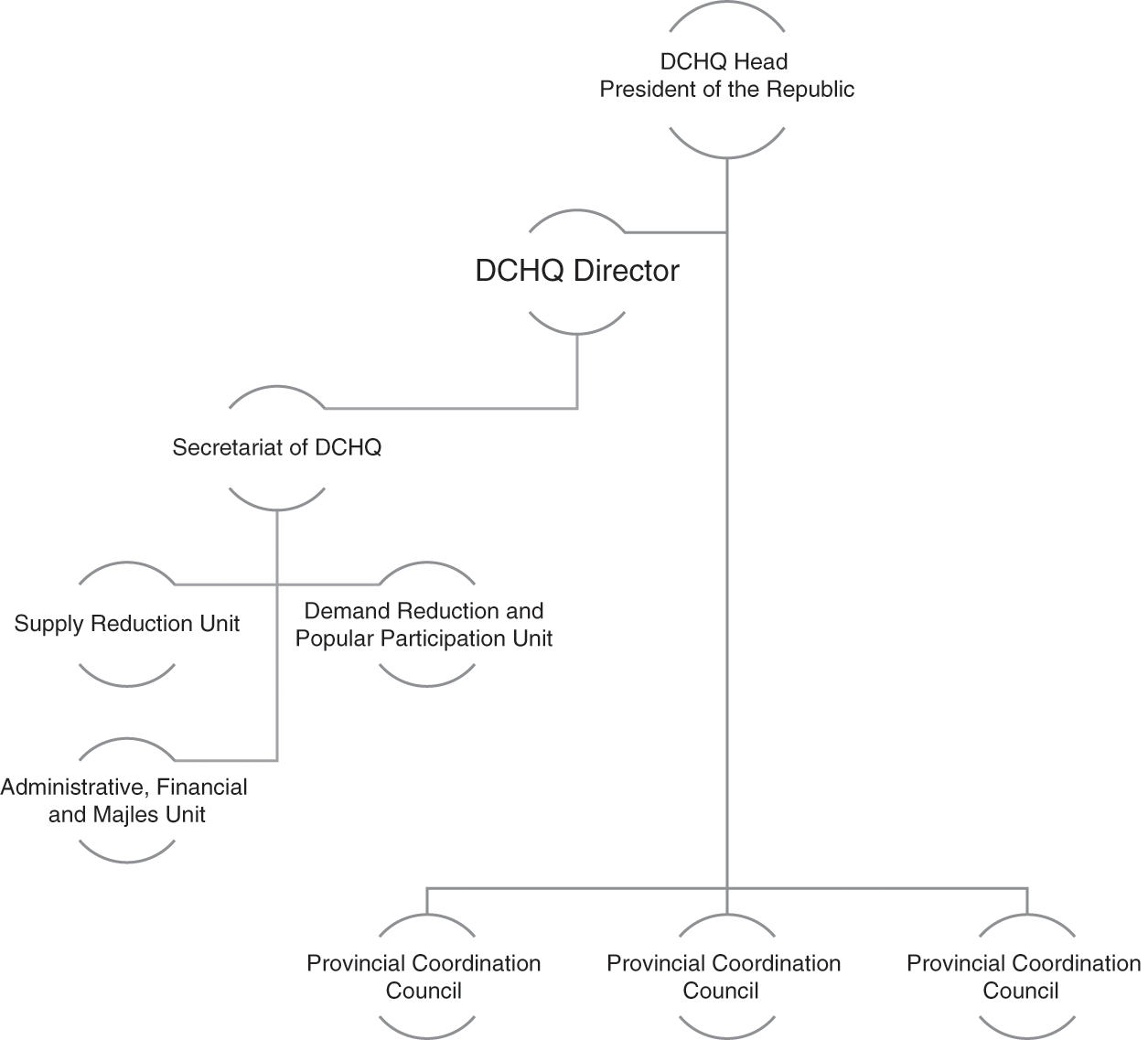

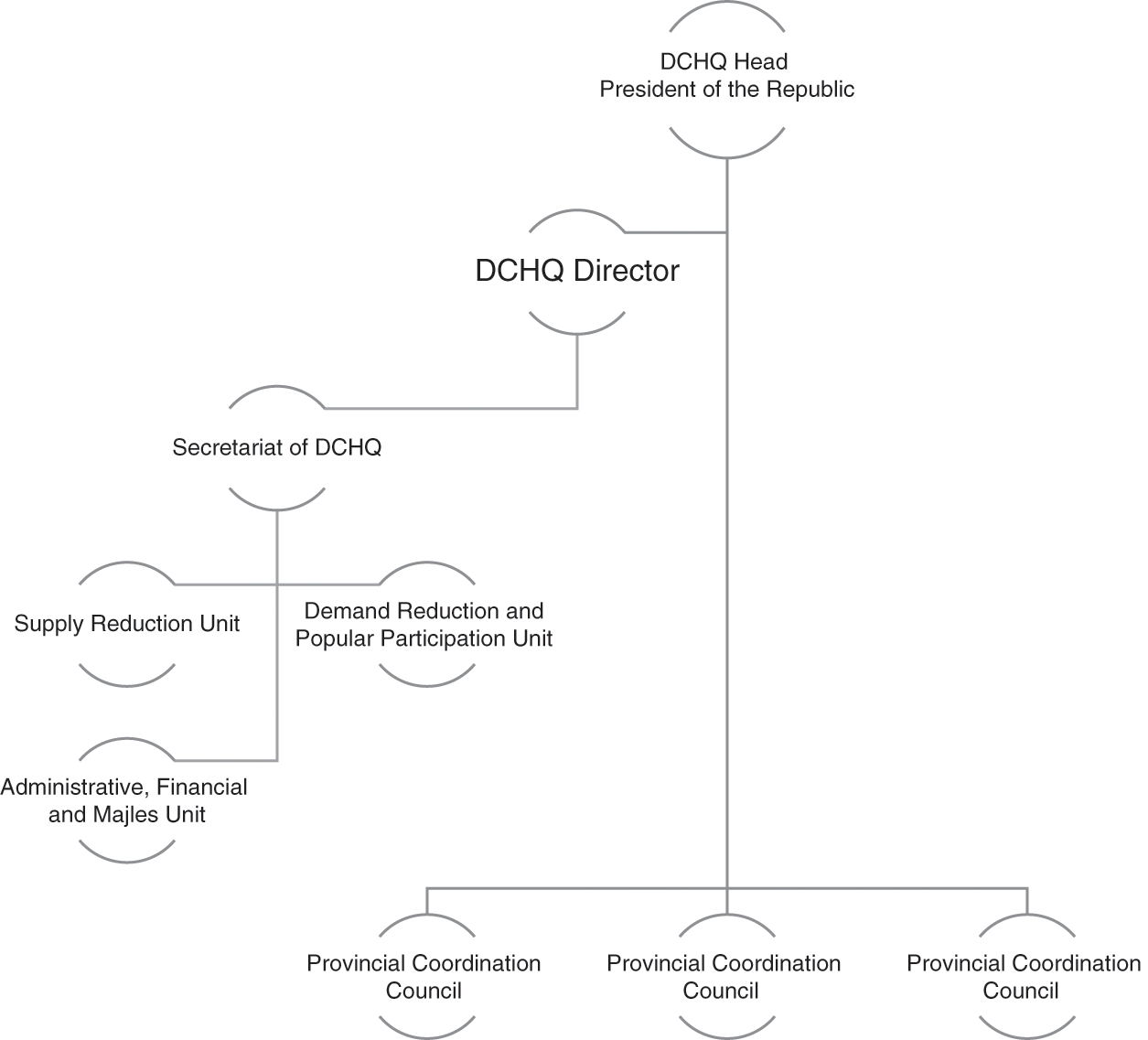

Institutionalisation and bureaucratisation occurred also in the field of drug policy. The creation of the Drug Control Headquarters (setad-e mobarezeh ba mavadd-e mokhadder) is the most significant development in the country’s drug policy structure, introduced following the approval of the text of the 1988 anti-drug law emanating from the Expediency Council.Footnote 57 Public officials’ experiences during the years of the war forged the mentality and practical undertakings of the post-war drug strategy. A distinctive signature of the war, the setad was a venue where officials of different political persuasions, institutional affiliation and expertise would meet and discuss matters of management in politics, security as well as economics, in collective terms. As an executive body, under the command of the president, the drug control setad advised the government and pushed in favour of structural reforms in drugs policy. The setad was also a model of intervention beyond the field of the drug war or, for that matter, the war. The number of governmental and intra-governmental bodies set up under the setad model has been a hallmark of Iranian politics since the 1980s. Among these, the Drug Control Headquarters has been the most powerful and financially significant, but others should not be left aside: the Irregular War setad,Footnote 58 the Moral Code setad (‘amr be-ma‘ruf nahi’ bil-monker), the Anti-Smuggling and Counterfeit Goods setad, the National Elections setad.

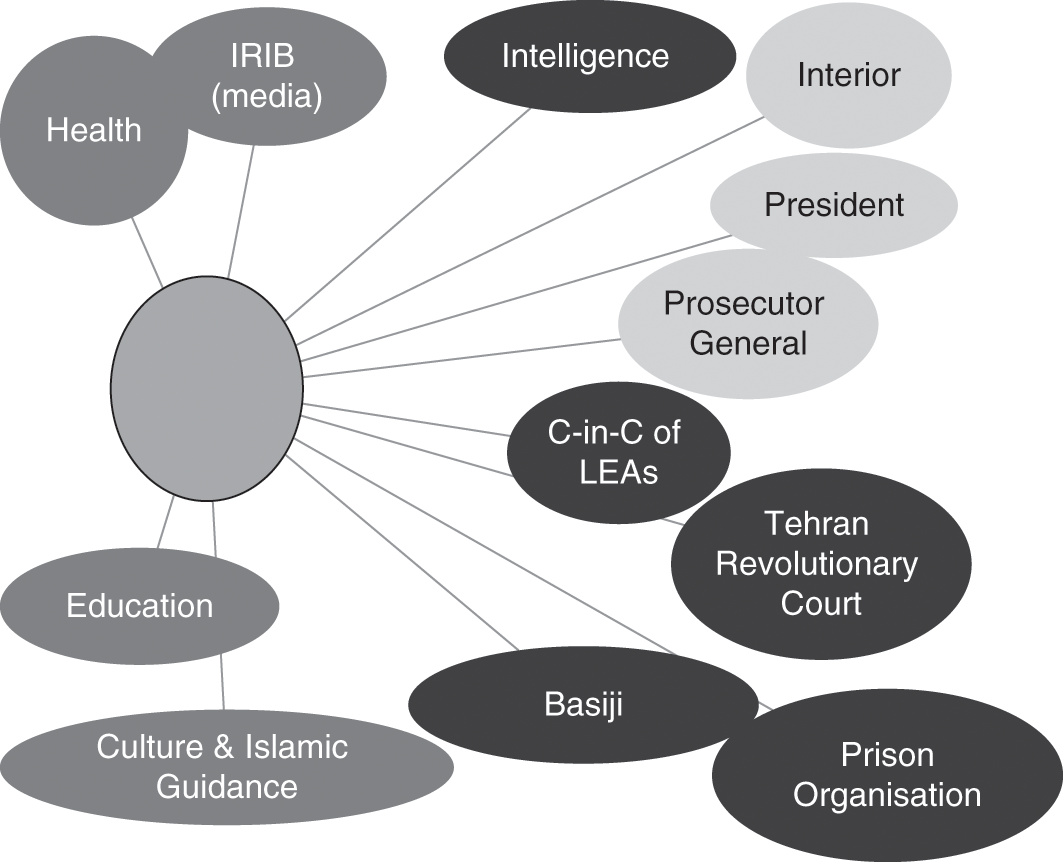

During the war, the headquarters became the most reliable and fastest way to respond to the urgencies of the front or to domestic problems, such as food shortages and security threats. With the conclusion of the war, however, the government dismantled the war headquarters. The drug war setad, however, had expanded and never ceased to operate since its creation. Its field of intervention spanned from anti-trafficking, intelligence gathering and judicial oversight – in other words, everything related to drug supply reduction – to rehabilitation, treatment (or drug demand reduction), international relations, prevention and research programmes. According to the 1988 law, the DCHQ is the place ‘where all the [drug] related executive and juridical operations shall be centred’ (Figure 3.4).Footnote 59

Figure 3.4 DCHQ Membership according to the 1988 Law

Heir to the Office for the Coordination of the Fight against Addiction, headed by Khalkhali in 1980, the DCHQ had the task of coordinating and executing the drug war nationwide. Weighted towards security-oriented programmes, with law enforcement, intelligence and judicial officials being more prominent, the DCHQ adopted a less security-oriented outlook from the 2000s. Its funding has increased constantly since its inception, as have its duties, which cover all the provinces in the country where the Local Coordination Council (shoura-ye hamahangi) of the DHCQ operate.

Its standing, nonetheless, has remained ambiguous. Because its place within the organs of the state is uncertain, the DCHQ is involved in every drug-related matter but does not hold responsibility and its presence at times remains incoherent and ineffective.Footnote 60 As a coordination body between different ministries, it rests upon a fragile compromise, which in practice is a coexistence of inconsistencies. The DCHQ works as an oxymoron, a site where otherwise incompatible mechanisms of political intervention find a place to operate (Figure 3.5). By bringing public agents with different approaches on drugs under the same roof, the DCHQ acted as the agency promoting, opposing, criticising and defending all and nothing in national drugs politics. It is both an institutional showcase for Iran’s War on Drugs and the engine of policies that, as I discuss in Part Two, have diverging political objectives.

Figure 3.5 DCHQ Structure in the 2000s

Despite its inconsistencies, the DCHQ had a significant impact on the first half of the 1990s. Under the directorship of Mohammad Fellah, a former intelligence and prison official, two important developments took place.

Deconstruction of scientific and medical expertise characterised the period following the Islamic Revolution in 1979. Instead, the war helped to reintegrate previously undermined professional categories, in particular scientists and doctors, who in the 1990s received renewed state support and encouragement for their activity.Footnote 61 The medical community gained influence in the making of the post-war approach to illicit drugs and, significantly, drug (ab)use. Mohammad Fellah seconded this trend and pushed tactically towards the medicalisation of ‘addiction’, with the objective of de-emphasising the crime-oriented weight of the drug laws. An outspoken critic of the 1980s policies, he argued for a medical approach and the abandonment of punitive measures. His push eventually succeeded in 1997 when the Expediency Council ruled that addiction was not a crime and could be therefore treated without punishment. Fellah’s other most significant endeavour was more covert. As head of the DCHQ, he facilitated the creation of NGOs in the field of addiction. In line with the mindset of these years, his attempt signalled the need to unburden the social weight of addiction through the inclusion of non-state organisms in tackling drugs. Not coincidently, one of the sub-sections of the DCHQ is specifically dedicated to ‘popular participation’ (mosharekat-e mardomi) in provision of welfare according to the drug laws. The seeds of this strategy, however, would be visible and effective only later in the 2000s.

Conclusions

Revolutions, combats and wars are events that dictate the rhythm of history. Less visible is the way these events impinge upon phenomena such as drugs consumption, drug production and the illegal economy. Drastic political change results in changing worldviews vis-à-vis drugs. This chapter accounted for the epochal transformation that drugs politics underwent from the fall of the Pahlavi dynasty – and its unconventional drug control programmes – to the populist and revolutionary onslaught against narcotics under the newly established Islamic Republic. Drugs acquired the value of political objects, charged with ideological connotation. They were anti-revolutionary first and foremost, only secondarily anti-Islamic. Part of an imperialist plot to divert the youthful strength of the revolution from its global goals, drugs coalesced all that was rotten in the old political order. Victory against illegal drugs was the ultimate revolutionary objective.

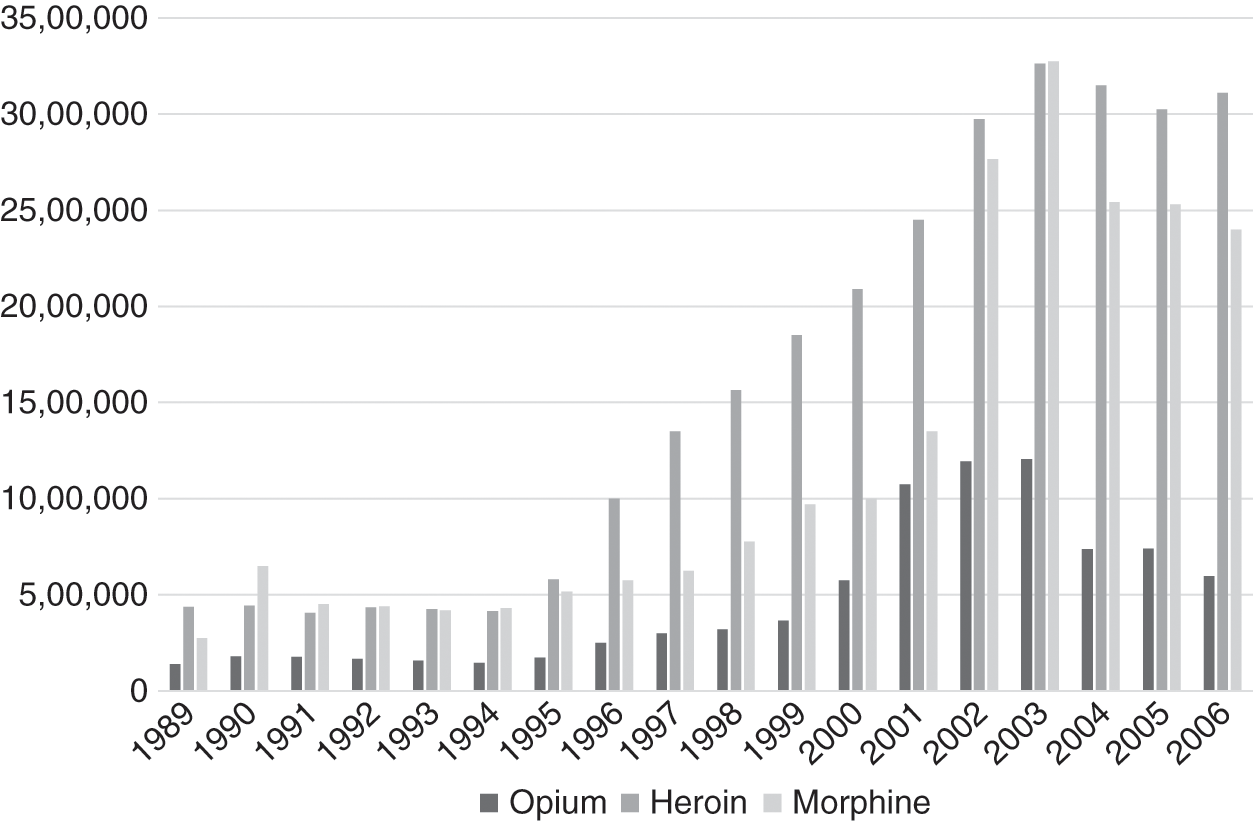

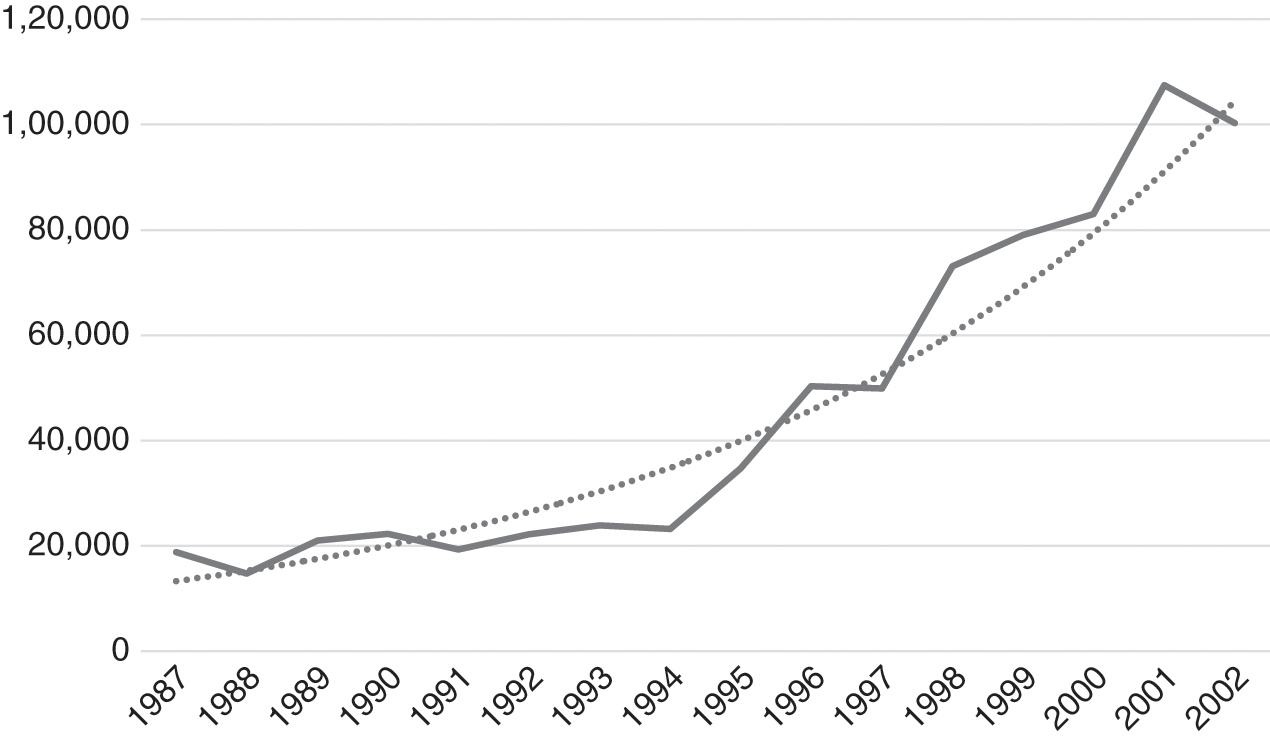

From the point of view of political practice, the combat against narcotics borrowed from those same methods used in the crisis management approach of the Iran–Iraq War. Mobilisation of popular forces, creation of multiple headquarters (the setadisation of politics) and the adoption of a language borrowing from the war discourse and its Manichean worldview. As the war ended, drugs politics shifted towards new methods and objectives. The inauguration of the ‘reconstruction era’ under president Ayatollah Hashemi-Rafsanjani (1989–97) meant that economic issues and the concerns of the middle class over security and public space became more central in policymaking. Since multiple competing agencies operated in law enforcement, in 1991 the government approved the merging of the City Police and the Gendarmerie and the Islamic Revolutionary Committees into the NAJA, the Islamic Republic Law Enforcement.Footnote 62 The centralisation of law enforcement increased the capacity of the police to control the public space, which resulted in a massive number of arrests, among which those for drug-related offences figured as the absolute highest. Similarly, it led to increasing number of drugs seizures, although this did not have a noticeable effect on drug price. By the late 1990s, drug prices stabilised – even considering Iran’s high inflation – and the public considered drugs as the third social problem after unemployment and high cost of life (Figure 3.6 and Figure 3.7).Footnote 63

Figure 3.6 Drug Prices from 1989 to 2006 (toman/kg)

Figure 3.7 Narcotic Seizure (all type) (1987–2002) (kg)

The shift from the external threat (Iraq) to the internal management of (dis)order had its direct effects on drug policy. With a government that pursued a smaller role for itself in the public life of Iranians and which sought the privatisation of some sectors of the economy, the management of the drug problem also faced transformation. The state-run treatment camps, amid the criticism of violence, abuse and mismanagement, were progressively closed, including that of Shurabad. There was an attempt to shift the provision of services for drug (ab)users to their families or, for that matter, to the private sector. In this, the reintegration of the medical professions was timely and instrumental.

By the end of the 1990s, there was a boom in private practice of treatment for middle-class drug (ab)users; their practice was not concealed from the public gaze and actually took place through advertisements in newspapers and on the radio, as well as posters on walls and in shopping malls. Although the government intervened to restrain the illegal market of treatment, private practices of cure and pseudo-treatment remained a vibrant sector of Iran’s addiction para-medicine. It was part and parcel of the socialisation of drug ‘addiction’ and the shift towards the privatisation of treatment that ensued in the later decades. Demobilisation, a key aspect of Rafsanjani’s politics, worked equally in the field of drugs politics. A new technocratic class gained legitimacy and asserted the right to manage the challenging environment of post-war Iran. It also promised to make this environment stable, prosperous and profitable for those operating in the private sector. These elements distinguished the basis for a new pragmatic approach to government, which set the stage for the emergence of reformism and post-reformism.