Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is a triple challenge – concurrently affecting health, economics and social protection. Social protection measures have played a crucial role as a resilience strategy during the COVID-19 pandemic both in the Global North and South (Béland et al., Reference Béland, Cantillon, Hick and Moreira2021b; Leisering, Reference Leisering2021; Greer et al., Reference Greer, Jarman, Falkenbach, Massard da Fonseca, Raj and King2021). Nearly two-thirds of countries in Europe and East Asia stepped in quickly with changes to social protection during the first peaks of infections (Kempf & Dutta, Reference Kempf and Dutta2021, p. 520).

There is emerging literature of comparative studies on COVID-19-related social protection measures with emphasis on certain social protection aspects (e.g. Aidukaite et al., Reference Aidukaite, Saxonberg, Szelewa and Szikra2021; Bariola & Collins, Reference Bariola and Collins2021; Béland et al., Reference Béland, Dinan, Rocco and Waddan2021a; Casquilho-Martins & Belchior-Rocha, Reference Casquilho-Martins and Belchior-Rocha2022; Cook & Grimshaw, Reference Cook and Grimshaw2021; Daly, Reference Daly2022; Greener, Reference Greener2021; Greve et al., Reference Greve, Blomquist, Hvinden and van Gerven2021; Kempf & Dutta, Reference Kempf and Dutta2021; Moreira & Hick, Reference Moreira and Hick2021; Moreira et al., Reference Moreira, Léon, Coda Moscarola and Roumpakis2021; Pereirinha & Pereira, Reference Pereirinha and Pereira2021; Seemann et al., Reference Seemann, Becker, He, Maria Hohnerlein and Wilman2021; Soon, Chou, & Shi, Reference Soon, Chou and Shi2021). In this paper, we re-develop an analytical framework to conduct a systematic qualitative analysis of change repertoires with a comparative perspective in the Global North. This study answers two research questions. What kinds of changes did ten welfare states implement during the first year of the pandemic, in 2020, compared to pre-pandemic social protection measures? Do changes in social protection show differentiation or similarities within and beyond welfare regimes?

The comparative study includes ten welfare states representing five different welfare state regimes: Germany and the Netherlands represent the Continental model, the United Kingdom and the United States represent the Anglo-American model, Italy and Spain represent the Southern European model, Japan and South Korea represent the Asian welfare state model and, finally, Finland and Sweden represent the Nordic model. All the countries can be defined as advanced capitalist Organization for Economic Co- operation and Development (OECD) economies. With a theory-driven framework and qualitative thematisation, we analyse what types of changes the countries implemented in social protection and to which extent these changes represented continuity vis-à-vis previous social protection measures. We refer to social protection as institutions constituting rules for legitimate implementation and as an analytical unit in the study (e.g. Streeck & Thelen, Reference Streeck and Thelen2005). Our approach continues new institutionalist comparative analyses (Hall & Taylor, Reference Hall and Taylor1996; Harty, Reference Harty and André2017).

First, we show rapid COVID-19-related changes were primarily incremental changes to existing pre-pandemic social security systems rather than new initiatives. Second, a tentative interpretation following our analysis is a convergence within risk categories and trends in social risk coverage across the studied countries. Somewhat surprisingly, the changes to social security systems related not just to emergency aid to mitigate traditional risks but, to a greater extent, also to prevent new risks from being actualised.

In the following, we start with insights into the theoretical and analytical framework while also reviewing previous literature on COVID-19-related changes to social protection. Then we outline our methodological approach and the context of the study. The third section reports the results with case examples discussing similarities and differences across welfare states. The paper ends with a summary of the key findings and conclusions with insights for future comparative research.

Rethinking changes in social protection within the COVID-19 context

Interpreting changes within the pandemic context calls into question the theoretical and analytical framework that accounts for changes during the pandemic. While social security systems vary significantly in countries, the welfare states share to a lesser or greater extent the commitment to promote a good life in societies through a variety of non-contributory and contributory benefits and services. In 2020, the share of social protection expenses in OECD welfare states were, on average, one-fifth of gross domestic product (GDP) (OECD, 2022).

Policy changes have widely been examined and explained with institutional theories and methodologies (e.g. Campbell, Reference Campbell2010; Frericks, Höppner, & Och, Reference Frericks, Höppner and Och2020; Hall, Reference Hall1993; Hall & Taylor, Reference Hall and Taylor1996; Pierson, Reference Pierson2004; Starke, Kaasch, & van Hooren, Reference Starke, Kaasch and van Hooren2013; Streeck & Thelen, Reference Streeck and Thelen2005). In our study, we highlight the importance of the pandemic as an external condition for change and account for the theory of path dependence affecting an overall logic of change. Path dependence works in this study in two ways: first, directly as part of the methodological formation of our study and, second, indirectly in the discussion with a conclusion of the significance of welfare regimes in explaining the COVID-19-related changes in social protection.

According to the path-dependence thesis, the institutional logics of existing social protection systems have layered and developed for a long time and are affected by earlier decisions, rules and legitimations (Kangas, Reference Kangas2020; Starke, Kaasch, & van Hooren, Reference Starke, Kaasch and van Hooren2013; Streeck & Thelen, Reference Streeck and Thelen2005). Thus, comprehensive reforms are difficult to make. Castles (Reference Castles2010) has analysed how unexpected national and international emergencies affect the character of welfare state interventions and welfare state development with examples of major events in history. One of the arguments was that the type of welfare state (and regime) matters to the quality of the changes. If governments implement entirely new measures, welfare states may break away from existing path dependencies and create new ones for social protection reforms (Van de Ven et al., Reference Van de Ven, Polley, Garud and Venkataraman1999). Recently, a study based on policy change theories (Hogan, Howlett, & Murphy, Reference Hogan, Howlett and Murphy2022) examined whether policy ideas and routines transformed because of the pandemic or were they merely a continuation of the status quo ante. Researchers argue that more than a pandemic being a critical juncture or turning point, the emphasis on a set of concepts related to the path creation might enable to explain the dynamic of complex policy change. Thus, even being temporary in nature, the changes to social protection and the introduction of new measures could be initiatives of path creations that might have an effect on policy trajectories in a long run. Specifically, this is the case when governments introduce completely new social protection measures and when pandemic is reinforcing changes that are underway. Thus, path dynamics during the COVID-19 pandemic can include various moments from path initiation to path termination. For example, initiation of a path trajectory can lead to development (path reinforcement). The trajectory can change its direction or speed (path clearing) and finally end to path termination. Path termination can also happen through gradual policy dismantling over time (Hogan et al., Reference Hogan, Howlett and Murphy2022).

Whether the measures introduced in the wake of the pandemic are departures from the existing schemes and, as such, represent innovative ideas of social protection has been one topic of interest in previous studies. There is already growing evidence of comparative studies on the Global South during COVID-19. A meta-analysis of 36 country case studies concluded that most changes were expansionary but focused on temporary and targeted benefits instead of universal benefits (Dorlach, Reference Dorlach2022). Differences were found between responses in developing and emerging economies. Leisering’s (Reference Leisering2021) comparative study concluded that, overall, the crisis has not been used as an opportunity to generate new ideas on social protection. The main feature has been to expand rather than reform old models. In advanced economies, the scope of the social protection measures has been much broader compared to rudimental changes in developing economies (ibid.).

During COVID-19, the comparative studies in the Global North have largely focused on welfare state comparisons within welfare regimes (Aidukaite et al., Reference Aidukaite, Saxonberg, Szelewa and Szikra2021; Béland et al., Reference Béland, Dinan, Rocco and Waddan2021a; Cantillon, Seeleib-Kaiser, & van der Veen, Reference Cantillon, Seeleib-Kaiser and van der Veen2021; Casquilho-Martins & Belchior-Rocha, Reference Casquilho-Martins and Belchior-Rocha2022; Greve et al., Reference Greve, Blomquist, Hvinden and van Gerven2021; Hick & Murphy, Reference Hick and Murphy2021; Moreira et al., Reference Moreira, Léon, Coda Moscarola and Roumpakis2021; Soon, Chou, & Shi, Reference Soon, Chou and Shi2021). Mostly, the scope of the research has covered one or two subthemes in social protection like short- time schemes (Cook & Grimshaw, Reference Cook and Grimshaw2021), protection of standard and non-standard workers (Seemann et al., Reference Seemann, Becker, He, Maria Hohnerlein and Wilman2021), work-family policies (Bariola & Collins, Reference Bariola and Collins2021), care-related measures (Daly, Reference Daly2022) and housing and referrals compared to the Great Recession 2008 (Moreira & Hick, Reference Moreira and Hick2021). Some studies have already examined the resilience defined in the ability of individuals, households, civil society organisations and state institutions to cope with and adjust to the COVID-19 pandemic, the economic lockdown and job and income losses (Pereirinha & Pereira, Reference Pereirinha and Pereira2021). These show differences in responses by welfare regimes and the success of the welfare states in coping with COVID-19 (Greener, Reference Greener2021), evidencing that in the early wake of the pandemic, liberal welfare states managed more poorly than others.

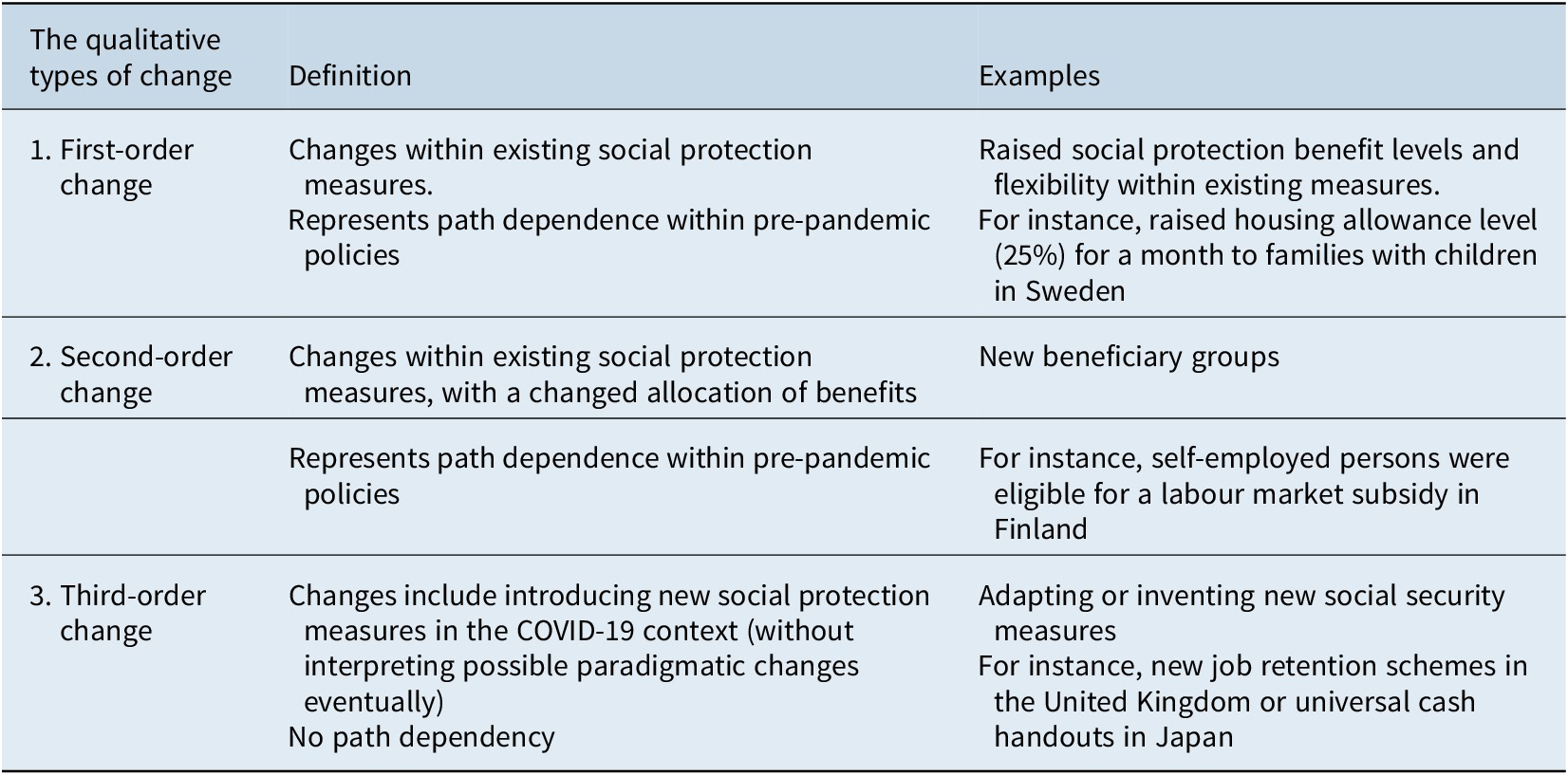

In this study, we re-develop an analytical framework and institutional perspective introduced by Hall (Reference Hall1993) using social protection measures as an analytical unit. The first-order change happens when settings of the policy instrument are changed. In our study, this refers, for instance, to a raise of benefit levels and horizontal expansions. A second-order change happens when policy measures and settings to achieve the goals change. With theoretical considerations, first- and second-order changes are related to the path-dependence thesis. However, the path dependence varies depending on whether there are changes to pre-pandemic instruments and measures, such as scaled-up benefits (first-order change), changed eligibility criteria (to pre-pandemic instruments and measures), or added new beneficiaries (second-order change). Changes to all three policy components – settings, instruments, and objectives – lead to an overall reform. According to Peter Hall, the third-order change arises from reflecting on previous experiences when the whole (sub)system will reform (Hall, Reference Hall1993, pp. 278–279). Hall’s third level of change means paradigmatic change, where the entire cognitive system and the normative and cognitive views change. In his studies, a radical shift from Keynesian to monetarist modes of macro-economic regulation was an example of third-order change.

We define first- and second-order changes as incremental changes (see Starke, Kaasch, & van Hooren, Reference Starke, Kaasch and van Hooren2013), but all changes can be interpreted as an initiation of path creation, temporary or not. Our interpretation of third-order changes happens in the COVID-19 context when introducing new social protection measures (instruments), even temporarily in contemporary societies due to the pandemic. In the pandemic context, there new social protection measures can be introduced as exceptional and emergency measures beyond existing social security schemes, so-called off-paths. Thus, third-order changes are not understood as major paradigmatic changes that could only be verified and analysed afterward, like in Peter Hall’s historical analysis. Although that could be an option, especially when changes are happening as path-breaking. It is more or less likely that a crisis like a global pandemic, which affects the lives of many and poses severe threats to societies, may induce a rethinking of the principles and institutions of social protection that change current social security instruments (Capoccia & Kelemen, Reference Capoccia and Kelemen2007; Leisering, Reference Leisering2021; Van de Ven et al., Reference Van de Ven, Polley, Garud and Venkataraman1999).

Research design

In the 2000s, welfare states underwent several reforms and transitions within social security and welfare provision. Also, gender aspects have given nuanced aspects to welfare state studies (e.g. Hemerijck, Reference Hemerijck2020; Pierson, Reference Pierson2004; Sainsbury, Reference Sainsbury and Sainsbury1999). In Nordic welfare states, the redistributive effect of social benefits has been significant. The emphasis on the governmental pillar and the generosity of social security, family policies enabling women’s full participation in the labour market, high employment rates and a wide range of universal services have distinguished a model from other welfare regimes. Liberal welfare states like the United States and the United Kingdom have relied more on a residual governmental role with targeting and need-based and income-tested benefits and, in parallel, on work-conditional benefits. In turn, in continental European countries, the security of (male) breadwinners with insurance traditions and employment guarantees has been dominant. A firm reliance on family in welfare provision in southern European countries has traditionally negatively affected women’s economic independence. However, it still affects the reconciliation of work and care-related duties in families (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen, Esping-Andersen, Gallie, Hemerijck and Myles2002).

Ideal-type welfare systems, as introduced by Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990, Reference Esping-Andersen1999, Reference Esping-Andersen, Esping-Andersen, Gallie, Hemerijck and Myles2002) and further developed and critiqued by many scholars, represent different welfare provision and coverage modes (see also Aspalter, Reference Aspalter2006; Bambra, Reference Bambra2007; Ferrera, Reference Ferrera1996; Sainsbury, Reference Sainsbury and Sainsbury1999). We used welfare regimes as a criterion for selecting the welfare states to be included in this study. The study includes ten welfare states, primarily European countries, representing five distinct welfare regimes. In this study, Germany and the Netherlands represent the corporate-conservative regime. The United Kingdom and the United States represent the liberal regime. Moreover, we included Italy and Spain in the Mediterranean regime and South Korea and Japan in the East Asian welfare regime. Finland and Sweden are representatives of the socio-democratic regime.

The data used in this study cover the period from 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2020. We collected information on the social protection measures taken in the wake of the pandemic to mitigate the social and economic impacts of the pandemic on individuals, families and households in the selected countries. We collected material on the content of the measures from documents produced by governments, parliaments and ministries. We also used up-to-date COVID-19 databases maintained by the following international organisations: International Monetary Fund (IMF), the OECD, the World Health Organization (WHO), International Social protection Association (ISSA) and Eurofound. In addition, research material was supplemented with follow-up information from additional research and media sources available. This data set with references was collected, used and presented in a working paper published by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health in publications of the Social Security Committee in Finland (Mäntyneva et al., Reference Mäntyneva, Ketonen, Peltoniemi, Aaltonen and Hiilamo2021, pp. 82–90).

The study was limited to the governmental and national-level social protection measures; regional, local and supra-national measures were excluded from this study. Moreover, non-monetary benefits, such as social services, were excluded from the analysis, even though they are an integral part of social protection systems, especially in the Nordic welfare regime.

Methodology

Theory-driven thematic content analysis was carried out by first classifying and defining the content of the measures by themes, then analysing and comparing measures in the included countries (Krippendorff, Reference Krippendorff2004). The starting point was identifying whether a social protection measure was compensating for a social risk emerging from the pandemic or if the measure was aimed to prohibit new risks from appearing. This classification of preventive and mitigating measures was the first phase of the thematic content analysis. The data were coded to preventive and mitigating measures and classified into ten themes and subthemes. Themes 1–5 represented traditional social risks, and we classified themes 6–10 as new risks in modern societies. Included themes are (1) unemployment benefits, (2) sickness benefits, (3) pensions, (4) benefits for families with children, (5) minimum income schemes and last-resort benefits, (6) direct payments beyond risk categories, (7) employment promotion, (8) benefits for students, (9) prevention of over-indebtedness and (10) housing support. Accounting for various social security systems in OECD countries apart from, for instance, employment promotion, most social security measures covered particularly non-contributory systems. Table 1 shows a thematic framework.

Table 1. Themes included in the study.

Second, we redeveloped Peter Hall’s theory of political change to make an analytical framework to study the pattern of changes in an abbreviated period (Table 2). The explanatory framework includes the distinction between the three diverse types of change, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Analytical framework.

As discussed above, first-order changes were flexibility within old measures and vertical expansion – like raised benefit levels – within existing social protection measures. Second-order changes expanded benefits to new beneficiary groups, and third-order changes were new initiatives.

Flexibility within pre-existing social security systems and scaling up benefits

An overview of the absolute number of first-order policy changes introduced by welfare regimes during the study period is pointed out in Figure 1. Our study suggests that both Nordic and Mediterranean welfare states made a significant effort in employment promotion to save jobs. Nordic welfare states made several changes to students’ benefits compared to other welfare regimes. Mediterranean and Nordic welfare states had more changes within pre-existing social security systems than Continental or Liberal welfare states. A number of measures representing the Asian regime were, in turn, between these two groupings.

Figure 1. First-order changes by types and welfare regimes.

First-order changes were increases in benefits, removing the waiting period for unemployment benefits and extending benefit periods. Overall, simplification of procedures (and easing conditions) was widely applied.

Thematically and in qualitative terms, similar changes beyond the welfare state regimes were applied in all studied countries. Governments eased eligibility criteria to get family allowances, extended the benefits and granted sickness benefits during school and day-care closures. Sweden and the United States introduced preventive sickness benefits for at-risk groups. In some countries where the share of informal day-care is significant, countries compensated for day-care expenses (e.g. the Netherlands, Italy, the United Kingdom and South Korea). Furthermore, countries delivered compensations during school closures (e.g. Italy and Spain) and raised care-related benefits (including housing allowance) in Continental welfare states – in the Netherlands, Germany, Sweden and Italy. For instance, in Germany, the conditions for receiving child benefits eased, and the income tax relief for single parents doubled between 2020 and 2021. In turn, in Sweden, the housing benefits for families with children were temporarily increased significantly, by a quarter, but only for a brief period.

In Liberal countries like the United States, there are many means-tested programmes for allowances to families with children. During the pandemic, support for childcare was provided to those working in sectors critical to the COVID-19 crisis, such as healthcare workers, rescue workers and sanitation workers. Applying for the childcare allowance has also been possible in the United Kingdom through the Universal Credit. Initially, the benefit was limited to workers in critical sectors, but soon eligibility criteria were eased, and the benefit was available to all in need. As the transition to the Universal Credit takes place gradually, support for childcare costs has been available through tax credits, in which usual rules were relaxed; for example, working less because of the pandemic did not affect tax-free childcare. In addition, if the family’s income level fell significantly because of the pandemic, they could apply for the High Income Child Benefit Charge (HICBC).

Combining work and retirement, especially among healthcare workers, was facilitated in Norway, the United Kingdom, Germany and Spain. In Spain, raising pension savings was eased, as was done in the United States. In South Korea, people could apply for suspension of monthly national pension payments. The conditions of last-resort benefits were changed least in four welfare states – Finland, the United Kingdom, Italy and South Korea – all representing different welfare regimes. In Finland, recipients of last-resort benefits were granted extra temporary epidemic compensation (75€ per month per person) for a maximum of 4 months.

While schools were closed and distance learning was not possible, students still received study support, for instance, in Sweden, Germany and the United Kingdom (also during quarantine or illness), including student loans. In Japan, students with financial difficulty received a cash grant that helped them cope with tuition fees and living expenses. The cash grant (€800–1600) reached approximately 430,000 students in the year 2020. In Germany, students could receive emergency grants (1–2 months) of a maximum of €500 under certain conditions. Several countries (Sweden, Norway, Germany, the United States and Finland) allowed postponements to student loan repayments and a reduction of payment instalments.

Recognition of over-indebtedness is one of the new risks in societies emphasised in country responses, especially in the Netherlands. Liberal and Mediterranean countries notably implemented changes to housing support. Common measures were eviction bans and suspensions. In the above-mentioned welfare regime countries and Japan, for example, electricity, gas or water supply or telephone connections were not cut off due to unpaid bills. Interest-free times and extensions of payment periods were common in studied welfare states. United Kingdom households could receive tax reliefs and reductions in tax payments. In Spain, people in difficult financial situations had income support for housing.

Expanding the social protection coverage

The second-order changes directed pre-existing compensations to new beneficiary groups. These changes gathered unemployment benefits, sickness benefits, benefits for families with children, minimum income schemes and last-resort benefits and employment promotion. Consequently, most of the measures introduced in 2020 did not diverge from the pre-pandemic social protection schemes but were expansions to existing social protection. Second-order changes are mapped by risk categories and by welfare regimes in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Second-order changes by types and welfare regimes.

The most significant extension of social protection in the countries studied was the access of those working in atypical employment, such as freelancers, to unemployment insurance. Many countries guaranteed income security, in particular in case of temporary job loss and, in some cases, because of caring for a child due to sickness.

As Figure 2 highlights, a remarkable share of the changes in Mediterranean countries was related to unemployment benefits. In Spain, where the proportion of atypical employment is high, efforts were made to secure the livelihoods of those in various employment relationships otherwise excluded from unemployment insurance. For example, temporary workers whose employment contract of at least 2 months ended during the emergency and who were not entitled to unemployment benefits could receive temporary support (€430/month). Unemployment benefits were granted to self-employed workers, including seasonal workers, during the emergency when income fell by at least 75% of the previous month’s earnings. A similar type of support was targeted at domestic workers who met certain conditions and at the workers under so-called permanent discontinuous contracts. In addition, eligibility criteria for unemployment benefits changed, including the wide tourism and cultural sectors.

Most of the social protection measures mentioned above were part of the expansion of The Temporary Employment Adjustment Scheme [ERTE (Expediente de Regulación Temporal de Empleo) scheme], which became applicable already in February 2020 and was extended several times with some changes along the way. Freelancers, the self- employed and other atypical workers received additional support in Italy, as in many other countries. In pre-pandemic times, wage subsidies were possible for some sectors and employees. In 2020, wage subsidies expanded to all, including the self-employed.

In continental Europe, in Germany, as part of the social protection package, the self- employed had more access to jobseekers’ basic benefits (Grundsicherung für Arbeitssuchende) and the related means testing was suspended. In the Netherlands, a temporary bridging measure meant that self-employed professionals (TOZO), self- employed workers and independent contractors could apply for income support. The benefit did not involve means testing, but the spouse’s income test did apply. The so- called flex workers benefitted retroactively from the support system’s temporary bridging fund for flex workers (TOFA). In turn, representatives of Liberal welfare regime states, the United Kingdom and the United States, improved their social protection for self-employed freelancers, independent contractors and gig workers. In the former, the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme allowed for 70–80% wage compensation by the state under certain conditions.

Furthermore, in the United Kingdom, the Universal Credit was increased and availability conditions were relaxed. In the United States, unemployment benefits were provided to persons who usually would not be eligible. Unemployment insurance was extended to grant compensation even if a person had exhausted their entitlement to the benefit.

Similarly, in Japan, health insurance was extended so that an employee who was infected, quarantined or isolated because of coronavirus was entitled to paid sick leave. The measure also applied to self-employed and gig workers under certain conditions. Similar to other included countries, in South Korea, unemployment benefits extended to cover groups not previously covered by unemployment protection, such as the self- employed, freelancers and other non-standard contract employees.

New risk-based benefits and direct payments beyond risk categories

To take our analysis further, the third-order changes were interpreted as new benefits. These instruments related to the direct payments but also the benefits for families with children, employment promotion and student benefits, as presented in Figure 3. The use of direct payments to citizens and residents was implemented in many countries to all like in South Korea and Japan, to a remarkable proportion of citizens and residents or was more targeted like in Germany. In Germany, families with children were allowed the one-time child bonus (approximately €300). Furthermore, in Japan, a one-off payment was directed to single parents (about €400 with a raised benefit depending on the number of children), and all families eligible for child allowances received a lump sum of about €80.

Figure 3. Third-order changes by types and welfare regimes.

Remarkable changes happened in Mediterranean countries. Italy introduced new emergency income, which was paid first in two instalments, each with a value between €400 and €800 (€840 for families with severely disabled members or non-self-sufficient members). Later in September 2020, previous applicants received €400 extra as a one-time payment. The tight eligibility criteria to receive the citizen income was, in the beginning, the reason emergency income was needed. At the same time, the conditions for receiving citizenship income, which was introduced before the pandemic, were made more flexible.

The pandemic accelerated the decision-making related to Minimum Vital Income in Spain to replace regional schemes in which redistribution to residents was not equal. New employment promotion measures were implemented in the United Kingdom and the United States. The Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme was introduced in the United Kingdom in March 2020. It enhanced income security for over 11 million employees by allowing working part-time and receiving subsidies for the time not worked in 2020. The result of a political struggle scheme continued, and eligibility criteria were changed several times. First, the government paid up to 80% of the wages of those made redundant under certain conditions. Since then, employers’ share of the costs increased. In the United States, to promote employment, the state temporarily funded 100% of Short-Term-Compensation (STC) programmes, in which employers reduce employees’ working hours instead of laying them off. States that did not have an STC programme have been able to set one up with support from the federal government. The use of these schemes became, however, less significant than expected. Second, stimulus payments were directed to the majority of the population and were repeated when the pandemic lengthened.

Interpretations of similarities and differences in changes within welfare regimes

We sum up our results by giving the importance to welfare regimes. Even welfare regimes have the explanatory power of welfare states to explain differences in modern welfare states. In this study, differences were evidenced only to a small extent. In continental European countries and the Liberal welfare states, the number of first- order changes was slightly smaller compared to other countries. Thematically, first- order changes with social risk categories in all societies showed convergence beyond regimes. The Mediterranean regime countries were distinct regarding second-order changes extending the benefits coverage, notably to work patterns like the self- employed and freelancers. Instead, the absolute number of the expanding measures was modest in Nordic countries and continental Europe. Third-order changes to mitigate traditional risks were rare in the data set, occurring in representative welfare states in Asian and Liberal countries.

As Figure 4 indicates, one preliminary conclusion and hypothesis for studies in the future can be drawn from welfare regime differences. In the Asian welfare regime, Japan and South Korea protected people against traditional risks more than preventing the new risks that were emphasised in European countries. Against public debate as massive emergency responses, the evidence shows that countries implemented a wide range of preventive measures. However, the Asian welfare states adopted more bold measures than other representatives of different regimes.

Figure 4. Mitigative and preventive measures by welfare regimes.

To deepen understanding, Table 3 explains that all welfare states have had primary priorities, also distinct from peer countries within welfare regimes. Sweden, Finland, Italy and Spain prioritised unemployment prevention as a number of preventive measures. Even in Spain there was a need to fill the gaps in unemployment protection. In turn, Germany and the Netherlands evidenced differences in responses, as did Japan and South Korea and Liberal countries. While Germany emphasises the prevention of over-indebtedness and benefits for families with children, the Netherlands was in line with Nordic countries, introducing several changes to employment promotion. Changes to sickness benefits and also to employment promotion were needed in South Korea. In Japan, the government made changes to protect the incomes of families with children and prevent unemployment with temporary allowances.

Table 3. Welfare state response profiles in pairs.

Conclusions and discussion

To conclude, the most studied social protection measures caused by the pandemic in year 2020 were following pre-pandemic politics. Most changes showed flexibility within pre-existing social protection measures and expanding without departures from core social protection measures in those countries. The results demonstrate vertical expansion within welfare systems (e.g. Pierson, Reference Pierson2004). The COVID-19 pandemic caused mostly first-order changes within existing social protection measures (76%, 128/169). This finding is partly in line with the path-dependence thesis and partly with previous studies (Moreira & Hick, Reference Moreira and Hick2021; Seemann et al., Reference Seemann, Becker, He, Maria Hohnerlein and Wilman2021).

A tentative interpretation following our analysis is a convergence within risk categories and trends in coverage across the countries. Thematically, emergency measures had the same characteristics from one country and welfare state regime, to another. Most of the measures were changes to unemployment protection to improve the unemployed situation and, as a preventive measure, employment promotion measures to preserve jobs and temporary cessation of illness and quarantine. In addition to the international social protection dimension, the study evidenced the priorities in country profiles, particularly in continental Europe, in Liberal countries and Asian countries. Our results resonate, to some extent, with previous studies that showed divergence in response in Liberal welfare regime countries (Béland et al., Reference Béland, Dinan, Rocco and Waddan2021a; Hick & Murphy, Reference Hick and Murphy2021) and Southern European countries (Casquilho-Martins & Belchior-Rocha, Reference Casquilho-Martins and Belchior-Rocha2022; Moreira et al., Reference Moreira, Léon, Coda Moscarola and Roumpakis2021).

The second-order changes were rarer (15%, 26/169). They included pandemic responses to amend social protection for the people like the self-employed, freelancers and businesses affected by COVID-19. That was the case in all welfare regime countries and particularly in Mediterranean countries. The pandemic hit especially hard in Italy and Spain, where the number of infections was huge and more deaths due to COVID-19 occurred compared to other studied countries in 2020. Also, stringency measures, including workplace and school closures, closures of public transportation, cancellation of public events and international travel controls, were strict in Italy and Spain (Hale et al., Reference Hale, Angrist, Goldszmidt, Kira, Petherick, Phillips, Webster, Cameron-Blake, Hallas, Majumdar and Tatlow2021). That explains, at least partly, why changes to social protection were needed. The expansions made the problems in modern social security systems visible, at least during emergencies. However, if eased eligibility criteria to increase the critical mass of beneficiaries (e.g. citizen income in Italy) would continue, changes might turn out to be transformational (compare Starke, Kaasch, & van Hooren, Reference Starke, Kaasch and van Hooren2013).

Last, amid the pandemic, we identified third-order changes (9%, 15/169) as novel measures compared to pre-pandemic policies. Liberal welfare states – the United Kingdom and the United States – and representatives of Asian countries – Japan and South Korea – introduced new initiatives. They included measures related to employment promotion, student benefits and direct income transfers. Overall, five welfare states – the United States, Spain, Italy, Japan and South Korea – used direct income payments as emergency income for individuals and households. Beyond traditional risk categories, direct payments were targeted to a significant share of the people or to all citizens and residents. Additionally, gig-economy workers’ social protection is to be developed. The share of social expenses has been modest (12% of GDP) compared to other welfare states. In South Korea, the pandemic has accelerated the public debate on basic income with regional experiments going on. We interpret this with the difference between emerging and mature welfare states (e.g. Aidukaite et al., Reference Aidukaite, Saxonberg, Szelewa and Szikra2021).

In mature welfare states, where social protection systems and instruments are layered, the flexibility within social security systems and measures during the pandemic is functional. When welfare states are not yet mature, innovations and adaptations are more visible than inconspicuous. For instance, in South Korea, there are ambitious aims to develop a national social insurance for the unemployed that will replace existing sector-specific schemes (Shin, Reference Shin2022).

The general assumption in the COVID-19 social protection literature has been that social protection measures have only been reactive responses to emerging needs. Our contribution has been to show with empirical analysis that preventive measures dominated overprotective measures in all countries except the Asian regime countries – Japan and South Korea. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, social investments in preventive measures have been one characteristic distinguishing the Nordic welfare regime from other regimes (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen, Esping-Andersen, Gallie, Hemerijck and Myles2002, p. 45). However, social protection measures applied during the pandemic favoured preventive measures in all studied European welfare states.

Social protection responses to COVID-19 demonstrate that new social risks, such as supporting housing and preventing over-indebtedness, were an important part of the package. During the Great Recession in 2008, measures to prevent mortgage defaults and evictions were not widely applied, unlike during the COVID-19 pandemic (Moreira & Hick, Reference Moreira and Hick2021).

This study has some limitations. Our conclusions concentrate solely on changes due to the pandemic. The convergence of the changes does not render void the fact that the coverage and level of social protection, and also the level of social expenses, have varied at baseline in the studied welfare states and regimes. East European post- communist countries, which were excluded from this study, have also gone through many important changes. Adding representatives of Eastern European emerging welfare states countries would have given a broader analysis of the COVID-19 responses in the Global North. It is also important to note that we analysed policy changes but not policy outcomes. The capacity of the welfare states to perform and achieve desired impacts through social protection measures is a crucial question and should be of interest for comparative studies in the future. The path creations of initial responses during the pandemic may open new insights into the question of the policy change in contemporary welfare states. By the same token, if incremental improvements will lead to transformations or not should be analysed in future studies.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank all reviewers for their thoughtful comments. The research for this article was funded by the Academy of Finland Strategic Research Council Project “Manufacturing 4.0 – Reshaping social policies” (WP5) and Academy of Finland special funding for COVID-19-related research (No: 13355273). Authors have no potential conflicts of the interests.