Relief, apprehension and curiosity may have occupied the thoughts of the first people to set foot on Malta’s shore sometime around the late sixth millennium BC. There was risk in the sea crossing, but the goal, a landmass which barely registered on the horizon from their homeland, probably in Sicily, must have been within their maritime capabilities. Thus conquered, this journey may have been made often by early seafarers, often enough to gauge that the islands could support their way of life before they made the commitment to stay. From that point forward, the human occupation of the Maltese Archipelago has contributed to a remarkable tableau shaped by endurance, ingenuity and adaptation.1

Most travellers to the archipelago today find their way to historic Mdina and Rabat, two towns sitting cheek by jowl on high ground in the heart of the main island – one of its most historic and picturesque locations. Around this central vantage point, visitors can see the expanse of Malta stretching to its shores. Their first impression might be that the landmass is not great and that its landscape, verdant in winter but parched by harsh summers, shows the unmistakable imprint of lives lived through countless passing generations. Looking east, encroaching urban areas are a compact hotchpotch of yellow limestone buildings that dazzle the senses in the midday sun. They advance inland from the coast as an unstoppable tide of development. Roads are soon lost from sight among houses but can be traced as they thread their way through rural areas north and west. Though the roads beckon to be followed, Malta’s western reaches are much less travelled.

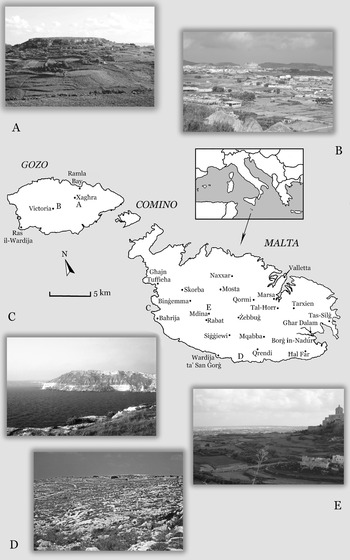

Close to Mdina, the valley dips and rises west to the Mtarfa plateau, and beyond that, the island tilts upward. Agricultural production takes place within the confines of small land holdings clearly defined by dry-stone walling – stone is never in short supply in these islands. The demarcation between urban zones and the countryside is often abrupt, and remarkably, given the small size of the islands, it is still possible to have a sense of the remote in some pockets of the countryside. Travellers seldom make their way to the western edge of the island, but what they miss is the dramatic cliff edge at land’s end plunging into the vast sea which stretches out to an unbroken horizon. If visitors travel to the north island, Gozo, there is less development, the land is weathered to a series of distinct plateaus and the impression of the rural dominates the senses.

Environmental Setting of the Island Cultures

Past visitors to the archipelago were equally struck by its harsh appearance, but usually any negative first impressions dissipated as the traveller explored the islands. An overriding spirit of enquiry, engendered by the Maltese landscape, was captured by Sir Richard Colt Hoare in 1819:

Nothing can be more uninteresting than the first aspect of this territory, to those who enter it on the land side. An extent of country, rather hilly than mountainous; thousands of stone walls, dividing and sustaining little enclosures, formed like terraces; villages so numerous as to bear the appearance of a continued town; and the whole raised on a barren rock, with scarce a tree to enliven the dusky-tinted view; such are the objects which first meet the eye of a traveller. This cheerless scenery struck me the more forcibly, after having quitted so recently the fertile and verdant regions on the opposite coast of Sicily. Indeed, I could nowhere find a parallel to it, except in some parts of the dreary Contea di Modica. Yet this was the spot which poetry and fiction had assigned as the voluptuous abode of Calypso! However, nature under all her forms, and in all her productions, frequently veils beneath an unpromising exterior, singularities, and even excellencies, which awaken curiosity, and raise admiration. Such was the case at Malta.2

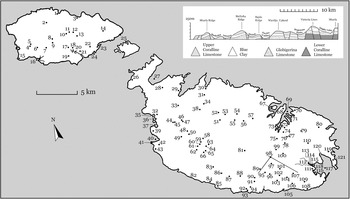

The geology of the Maltese Archipelago proved to be just as alluring to early travellers and scholars as its ancient human history.3 Comprising three main islands – Malta, Gozo and Comino – its area spans a total of only 316 km2 with additional uninhabited minor landmasses. Located in the central Mediterranean region, the position of the archipelago has long been recognised as economically, politically and strategically advantageous. Insularity must have been a defining quality for inhabitants who called the islands their home.4 The sea forms both a barrier and a means of connectivity through maritime communication to not-so-distant neighbours: from shore to shore, Sicily lies some 80.5 km from Gozo; from Malta to Pantelleria, it is around 224 km; to Linosa, 132 km; to Lampedusa, 161 km; and to Tunisia, 303 km. Sea levels dropped by some 120 m during the last glacial period (from 70,000 BP), at which time Malta and Sicily were linked to Italy in a land mass referred to as the Hyblaean Plateau. If people did frequent these southern reaches of the European continent, however, they also withdrew into the large territory to the north rather than risk becoming isolated.5 Around 12,000 BC, whatever narrow land bridges remained were permanently submerged, isolating Malta. Land links to Africa that might have afforded the passage of human and animal migrations are unlikely on present evidence, with a 40-km stretch of open water forming a perpetual barrier.6

Geological components of the islands consist of layers of limestone – Lower Coralline, Globigerina and Upper Coralline – laid down as marine deposits. Blue clay (or marl), over which lies a greensand (sandstone) layer, is trapped between the Globigerina and Upper Coralline strata. Globigerina is softer than the other limestone deposits and varies in hue from whitish to rich yellow. It is the preferred building material in Malta, and a number of large quarries can be found on the islands which exploit these deposits and vary in thickness from 20 to 200 m.7 This stratum, too, has been subdivided according to depositional layers into Lower, Middle and Upper Globigerina. Small amounts of chert (the term is used for the lesser-quality pale to very dark grey flint with a granular texture),8 which forms in the local Middle Globigerina limestone deposits, were used for tools, but the islands are devoid of high quality-flint. All other materials, such as obsidian (volcanic glass), basalt and metals, found in ancient contexts were imported.

The Lay of the Land

Malta was shaped by a series of uplifts and subsidence to form a tilted landmass, higher on the western side of the island, with dramatic eroded coastal cliffs rising abruptly to over 200 m above sea level and gradually sloping down to the east (Figure 1.1). The landmass is fractured by a series of smaller fault lines which lie approximately north-east–south-west, particularly evident in the western half of the island (Figure 1.2, inset). A major division is formed by the Great Fault line (along which are built British fortifications known as the ‘Victoria Lines’) in Malta spanning from Fomm ir-Riħ in the west to the eastern shore at the foot of Madliena Tower; north of this, smaller fractures have shaped the islands into a series of ridges and valleys (from south to north, Binġemma, Bidnija, Wardija, Bajda, Mellieħa and Marfa Ridges). In southern Gozo, a fault line along a similar bearing formed the Ta’ Ċenċ cliffs.9

Figure 1.1. Map of Malta: (A) View eastward to In-Nuffara (in 2007); (B) view west to Victoria (in 2009); (C) Fomm ir-Riħ Bay, looking north from Ras ir-Raħeb, with geological strata visible in the cliff face (in 1998); (D) looking west across rocky landscape towards the Misqa Tanks area, near the prehistoric sites of Ħaġar Qim and Mnajdra (in 1991); (E) view eastward from Mtarfa to Mdina and surrounding fields (in 2013)

Figure 1.2. Map of Malta. Gozo: (1) Marsalforn, (2) Ta’Kuljat, (3) Ramla Bay, (4) Għajn Abdul, (5) Il-Mixta, (6) Santa Luċija, (7) Kerċem, (8) Victoria, (9) Taċ-Ċawla, (10) Santa Verna, (11) Xagħra Circle, (12) Ġgantija, (13) In-Nuffara, (14) Il-Haġra l-Wieqfa menhir, (15) Ras il-Wardija, (16) Xlendi Bay, (17) Xewkija, (18) Tal-Knisja, Mġarr ix-Xini, (19) Ta’ Ċenċ, (20) Mġarr ix-Xini, (21) Għar ix-Xiħ, (22) Għajnsielem, (23) Mġarr, (24) Xatt l-Ahmar. Comino: (25) Santa Marija Bay. Malta: (26) Il-Latmija cave, (27) Mellieħa Bay, (28) Mellieħa, (29) Xemxija, (30) Burmarrad, (31) Tal Qadi, (32) Għajn Tuffieħa, (33) Qala Hill, (34) San Pawl Milqi, (35) Golden Bay, (36) Għajn Tuffieħa Bay, (37) Ġnejna Bay, (38) Bidnija, (39) Qala Pellegrin, (40) Fomm ir-Riħ Bay, (41) Ras ir-Raħeb, (42) Il-Kunċizzjoni, (43) Baħrija, (44) Mġarr, (45) Ta’ Ħaġrat, (46) Skorba, (47) Żebbieħ, (48) Binġemma, (49) Nadur Tower, (50) Qallilija, (51) Mosta, (52) Fort Mosta, (53) Naxxar, (54) L-Ilklin, (55) Lija, (56) Attard, (57) Birkirkara, (58) Mtarfa, (59) Ġnien is-Sultan, (60) Għajn Qajjied, (61) Għajn Klieb, (62) Nigred, (63) Mdina, (64) Domus Romana Museum, (65) Rabat, (66) Għar Barka, (67) Manoel Island, (68) Valletta, (69) Grand Harbour, (70) Kalkara, (71) Birgu (Vittoriosa), (72) Kordin I, II, III, (73) Marsa, (74) Paola, (75) Tal Ħorr, (76), Ħal Saflieni, (77) Tarxien megalithic structure, (78) Santa Luċija, (79) Buleben, (80) Bidni, (81) Żebbuġ, (82) Dingli Cliffs, (83) Buskett Gardens, (84) Għar Mirdum, (85) Wardija ta’San Ġorġ, (86) Girgenti, (87) Laferla Cross, (88) Siġġiewi, (89) Ta’ Wilġa, (90) Misraħ Sinjura, (91) Qrendi, (92) Misqa Tanks, (93) Mnajdra, (94) Ħaġar Qim, (95) Mqabba, (96) Ħal Millieri, (97) Tad-Dawl, (98) Malta International Airport, (99) Luqa, (100) Bir Miftuħ, (101) Ħal Kirkop, (102) Safi, (103) Żurrieq, (104) It-Torrijiet, (105) Wied Moqbol, (106) Tal-Bakkari, (107) Ta’ Ġawhar, (108) Għar Ħasan, (109) Ħal Far, (110) Żejtun, (111) Birżebbuġa, (112) Għar Dalam, (113) Ta’ Kaċċatura, (114) Borġ in-Nadur, (115) St. George’s Bay pits, (116) Pretty Bay, (117) Marsaxlokk Bay, (118) St. George’s Bay, (119) Tas-Silġ, (120) Il-Magħluq Harbour, (121) Delimara Peninsula (map by C. Sagona). (Inset) Cross section showing the geology of northern Malta, its stratified bedrock and fault lines

As limestone decays, it forms fertile red- to brown-coloured terra soils. Historically, farmers have also made soil by breaking up the stone and adding organic material in the course of intensive land-use practices.10 Generally, soil cover is thin, half a metre or less, with the deepest deposits accumulating in the valley floors. Erosion has had a significant impact, exposing the bedrock over large swathes of land in the west of the island.

Deep cores and other environmental samples have facilitated reconstruction of the climatic conditions from ca. 45,000 years BP in the central Mediterranean region, which is likely to have some bearing on climatic conditions in the archipelago. Though the chronological depth of these analyses exceeds the scope of this study, of interest are findings concerning the Holocene period, which witnessed the rise of agriculture and animal husbandry in lands to the east, enabling human colonisation of remote island locations in the Mediterranean Sea. The Postglacial period (ca. 10,450–9700 BP) ushered in a warmer, humid climate, a result of which was that forest cover of deciduous and oak trees increased in the central Mediterranean region. Colder and dryer events punctuate the record at around 8400–8000 BP and ca. 6600–6000 BP, but the trend towards more arid conditions prevails and is especially marked in North Africa.11 Whether Malta experienced the same degree of forestation is less certain, but pollen extracted from cores in the silted valley of the Burmarrad (from deposits 14 m deep) indicate that minor stands of Erica, Pistacia and Quercus were present in Malta in a mid-Holocene record characterised by dense scrubland. Analyses of cores taken from this and the Marsa regions have found that soil erosion from highlands led to silting in valleys and the mouths of waterways. Thinning of tree cover and loss of vegetation on slopes and higher areas may have been triggered by arid conditions or, equally possible, such changes may have resulted from land clearing after people colonised the island.12

Marl layers vary in thickness (up to 75 m in places13) and are especially apparent on the eroded coastal margins (see Figure 1.1). This clay source was exploited for pottery production and for architectural use in antiquity.14 The impermeable clay layer, with the overlying greensand, traps rainwater that percolates down from the surface to form perched aquifers, which erupt as vital springwater sources. These springs compensate for the relative scarcity of surface water. Aquifers were further tapped at intervals by farmers in rural regions who developed subterranean water galleries, akin to qanat technology, that Keith Buhagiar suggests might date back to Roman and Islamic times in the islands.15 None of the natural water sources can be classed as rivers; rather, weathered valleys (Maltese ‘wied’) may carry water in streams, creeks or wadis, but because farmers have redirected the spring flows, many are dry. Large pits, cisterns and water channels which have captured and controlled water throughout the human occupation of the islands have been documented and will be discussed in the pages that follow.

The Learned Scholar, Antiquarian, Artist and Collector

The merits of this central Mediterranean location were recognised by ancient classical scholars; Malta may not have been at the forefront of political forces in the wider known world, but the islands did not go unnoticed. Of the Phoenician settlers, their Punic descendants, Hellenised neighbours and inhabitants of the not-so-distant Roman heartland who influenced the course of history for the main islands of Malta and Gozo, there is some written account. Such ancient texts sketched a broad historical framework for the times in which they were written. But the Bronze Age and Neolithic inhabitants before them, the nameless generations, had to wait until the modern era for their history to be uncovered. Classical commentaries, notable among them works by Diodorus Siculus, Cicero and Ptolemy, concerning the islands that they knew as Melita and Gaulos formed a starting point for historical enquiry as early as the sixteenth century AD. In reality, a time before the Phoenician never really concerned the deliberations of the antiquarians. Theirs was a quest to accommodate history as it emerged from biblical, Greek and Latin texts. Early chronicles of the islands can be threaded with fanciful and legendary events, antediluvian notions and mismatched associations between historic accounts and prehistoric ruins.16

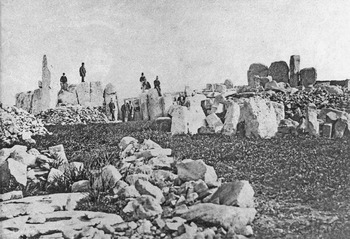

By the seventeenth century, an increasingly mobile elite emerged, for whom personal enlightenment could be measured not just by their writings but also by accumulated objects of interest which they gathered during their journeys. In many respects, it would be otiose to focus too deeply on the individuals who penned the first histories of the islands, as numerous studies have already done so with encyclopaedic fervour. Nonetheless, antiquarian accounts and artistic representations are still valued for their depictions of urban centres when the islands were less developed.17 Some will feature throughout this work simply because the written accounts or sketches by these early scholars carry the reader back to a time when development was modest and ancient ruins were still obvious in the landscape, before urban expansion at best hemmed in some relics of the past and at worst obliterated them.

Regarding Malta, the starting point for the early modern era is Quintinus (Jean Quintin d’Autun), whose description of the islands, classed as the earliest written account, drew on his personal observations made between 1530 and 1536.18 What survived of early collections of antiquities, particularly those assembled by Giovanni Francesco Abela, later formed the nucleus from which the National Museum of Archaeology grew.19

Giovanni Francesco Abela (1582–1655)

Abela’s intellectual pursuits led him to amass an eclectic array of imaginative curios of less reliable attribution and genuine artefacts from tombs, as well as objects he obtained from digging in ancient sites. The collection was effectively the first museum in Malta, housed in his Villa di San Giacomo in Marsa and arranged aesthetically with provenance factored into the order of artefacts.20 Woven into the fabric of the collection and threaded through his treatise, Malta Illustrata: Della Descrittione di Malta Isola nel Mare Siciliano con le sue Antichita, ed altre Notitie, was the basis for lasting recognition of Malta’s cultural heritage among scholarly society not just in the islands but also throughout Europe. Abela’s book was the first systematic account of Malta’s known history. Despite, or perhaps because of, the acclaim given to Abela’s private museum, his collection was plundered in the decades after his death. What artefacts remained came finally under state care in 1811 during British rule and were first housed in the library, the site of the fledgling national museum collection in Valletta.21 Judging by the sheer quantity of artefacts sourced in Malta, the most remarkable aspect is that the tombs, the source of many objects, appear to have remained largely intact until the 1600s.

A significant part of the scientific enquiry turned to the natural world. Although fossil bones appeared in early displays, including Abela’s, they were explained as evidence of the giants written into classical narratives, notably the Cyclops of Homer’s Odyssey and giants in Old Testament tradition.22 By the nineteenth century, such interpretations could no longer be sustained in the light of decades of intense scrutiny of fossil remains which had exposed a rich faunal array of extinct species or ancestral remains of living animal species in fossil-rich deposits of Sicily and Malta. Giants’ teeth, under close examination, were identified as belonging to pigmy elephants. Thomas A. B. Spratt and Andrew Leith Adams, in particular, while on duty in Malta (the former within the Royal Navy, the latter in the Royal Army Medical Corp), actively explored, identified and excavated caves or other fossil-bearing deposits.23 Adams also made some observations regarding the archaeological sites in the islands, recorded in his Notes of a Naturalist in the Nile Valley and Malta, published in 1870.

History of Archaeological Investigation

A strong Maltese identity grew within the political disquiet of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries AD. The islands benefitted from the development of port infrastructure, which, in turn, became the focus of growing urban hubs, but the population chafed under the constraints of foreign rule. Malta was governed by the knights of the Order of St. John (1530–1798), experienced a brief French interlude under Napoleon (1798–1800) and subsequently became a British possession (officially from 1814 to 1964). Each regime tried, to varying degrees, to mould the island population to comply with foreign sensibilities on socio-political and religious levels. Throughout this time, the value of the archipelago as a strategic and economic mid-point in the Mediterranean steadily grew, and with growth came increased prosperity.24

Wider trends in scholarly pursuits and growing local sentiments towards cultural heritage crystallised in 1865 with establishment of the Archaeological and Geological Society of Malta (Figure 1.3).25 Although the society lost momentum in the course of the next decade, its members, nonetheless, contributed significantly to the identification and documentation of the islands’ fixed and movable archaeological heritage. Most importantly, the association comprised a cross section of society – Maltese and European – whose names appear in numerous accounts of discoveries made in Malta and Gozo. From its inception, key figures in the movement appear to have both stimulated the government’s recognition of its obligations and acted upon the resulting official concern for the historic and archaeological record. In 1881, the Council of Government established the Permanent Commission for the Inspection of Archaeological Monuments.

Figure 1.3. Photograph reproduced from the Letters Book of the Archaeological and Geological Society of Malta 1860 (society scrapbook). Members of the society (including two women) photographed among the stones of the unexcavated site of Ħaġar Qim.

Antonio Annetto Caruana’s contribution, in particular, should not be overlooked. Although dated now, his lengthy government-commissioned reports, written during the 1880s and 1890s, do give a reasonably clear account of the known archaeological sites and an overview of the ancient artefacts which had found their way into government and private hands.26 No less important during this time was the quest to document inscriptions found on the island. Among them was a pair of monuments with bilingual texts that were instrumental in the decipherment of Phoenician alphabetic writing by Jean-Jacques Barthélemy, facilitated by the accompanying Greek version. One of these monuments was eventually deposited in the Louvre after it was given to the French king, Louis XVI, in 1780 by Emanuel De Rohan, Grand Master of the Order.

Caruana was forthright in pointing out the failings of past governing bodies to preserve historical sites, condemning the loss of artefacts of national importance which had been spirited away from the islands, and scathing about the continuing trend for discoveries of the day to remain in private hands.27 He made concerted efforts to track down ancient objects held in various government departments, found during the course of building the islands’ defences and infrastructure, so that they could be brought together under the protection of the National Library.28 While it could be said that through the publication of his reports, Caruana effectively put the British government on notice not to repeat the failings of the past, it is also the case that the sense of protecting ancient remains was matched in Britain itself, resulting in the 1882 Ancient Monuments Protection Act. This movement was carried to the lands of the Empire and was manifest in, for instance, the Archaeological Survey of India and the establishment of an Archaeological Department in Burma.29

Notwithstanding his positive steps towards consolidating and safeguarding the cultural heritage of the island, Caruana was a product of his time and a theological education; history to him was bound to the biblical narrative. Depending on one’s interpretation, Caruana either could not or would not consider a period in Malta earlier than the Phoenicians, who figured in the biblical accounts. But no amount of Christian zeal could sustain the link he made between the prehistoric megalithic structures in Malta and Gozo (ca. 3600–2500 BC) and the Phoenicians of the first millennium BC.30

Scientific rigour gradually transformed the approach to ancient world studies and archaeological fieldwork. The likes of Henry Rhind in 1856 had already started to question the Phoenician involvement in the construction of the lobed buildings which we now know belong to a prehistoric era.31 Around the turn of the twentieth century, Albert Mayr, in particular, brought the logic of archaeological interpretation of his time into his discussions concerning the ancient remains of the archipelago. Malta was the focus of much of his research, and Mayr’s work benefitted directly from his surveys of the ancient sites and examination of private and museum collections during visits to Malta in 1897–1898 and 1907. Nonetheless, he was influenced by Arthur Evans, who following prevalent diffusionist theory, looked to Mycenae for antecedents of the spiral iconography decorating some of the megalithic monuments and pillars (or baetyls) as a focal point of ancient devotion.32 Notions of Aegean influence endured until radiocarbon analysis provided a means of absolute dating that plunged the megalithic lobed structures deep into a prehistoric, Neolithic past.

New Archaeological Directions during the Twentieth Century

Within the first half of the twentieth century, a time of political and economic instability that resulted in two world wars and a depression, it is probably fair to say that the direction of Malta’s allegiances mattered not just in the wider arena but also at home among its population as it moved resolutely towards independence. There was a groundswell that looked to shake off British rule and rekindle links with Italy, a historic relationship characterised by cultural affinities nurtured among the intellectually elite in Malta.33 In light of these trends, British scholars realised that they were not alone in recognising the great prospects for fieldwork and sustained research programmes on the islands (focussed firmly on the prehistoric remains). They became vocal in their calls to reinvigorate interest in the islands, lest they lose to the machinations of international political rivalry the potential to excavate independently on British-held territory in Europe and their historic advantage in Malta.34

Work undertaken by Luigi Maria Ugolini from 1924 to 1935 comprised a systematic documentation of the prehistoric holdings in the museum in Malta and an architectural survey of the monuments. A member of the Italian Fascist Party from 1924, Ugolini was appointed Inspector of Excavations and Archaeology in Italy (1930), and his research in Malta in 1931 was directly funded by the state at Benito Mussolini’s instigation. Ugolini’s was a significant contribution to the study of Malta’s prehistory,35 but his untimely death in 1936 and the spectre of war ordained that the extensive archive of data he and his colleagues had amassed languished, forgotten, in the Museo Nazionale Preistorico Etnografico ‘Luigi Pigorini’ until it was rediscovered in 2000.36

Albert Mayr’s publications, followed closely by Erich Becker on Christian and Jewish iconography in the islands’ funerary contexts,37 and Ugolini’s research were catalysts for renewed fieldwork, largely organised through the British School at Rome under the directorship of Thomas Ashby (1906–26). Such interest in the islands must be measured against the significant role Sir Themistocles Zammit played in the first quarter of the twentieth century. The distinguished career of this learned Maltese doctor was multi-facetted. Renowned in the field of medical research, he was both the first director of the National Museum, when it became an institution independent of the library, and an active field archaeologist.38

He was the type of true scholar not only in depth of knowledge and range of accomplishments, but in the generosity with which he placed his knowledge at the disposal of others [His Excellency, Sir Harry Luke, The Officer Administering the Government, 28 February 1936].39

It is clear from those who acknowledged his help in their publications that Zammit was a scholar of note and, most importantly, a facilitator – perhaps the most positive and productive aspect of his illustrious career. It was largely through his assistance that the work of Ugolini and numerous visiting scholars was undertaken. No less remarkable and to his credit was his scholarly recognition of notable women in the field, and after meeting Margaret Murray (1863–1963) in England in 1920, he encouraged her to conduct excavations in Malta, principally at the prehistoric site of Borġ in-Nadur. His invitation was well founded. She was then in her late fifties and had years of fieldwork and active research still ahead of her (well after retirement), but her contribution to Malta’s archaeological record developed during five seasons in the island is noteworthy. Her publications on the cultural remains found at Borġ in-Nadur and the Bronze Age of Malta were comprehensive, and although they are now dated, in some respects they were unparalleled for many decades.40 Accompanying Murray were her colleagues and friends Edith Guest, who worked on skeletal remains and photography, and Gertrude Caton-Thompson (1888–1985), who had been asked by Zammit to work at Għar Dalam, close to the site of Borġ in-Nadur.41 Only in very recent times, some eighty years after Zammit, have women of Maltese nationality begun to break through the glass ceiling of a field which has been dominated by men.

Although the intertwined issues of nationalism and politics can be detected in the archaeological pursuits of those who carried out research and fieldwork in Malta, Zammit was not preoccupied by such political interests.42 Preserved in the numerous field diaries he kept (see, e.g., Figures 3.12 and 5.1, nos. 10–12) and throughout his annual museum reports to the government are notices concerning the presence of prominent expedition members, independent scholars or others who assisted him in the field, which clearly indicate that Malta was a hub of archaeological activity.43 Fully aware of the significance of the islands’ exceptional ancient past, Zammit brought discoveries to a wide audience through a range of scholarly reports and publications. He embraced the principle that the holdings of the museum were of international significance, an asset that needed safeguarding for the future, and he made the collection available to researchers.44 Overall, there is a strong sense that he was participating fully in the international domain. He challenged entrenched views by looking to a Neolithic age for the megalithic buildings, an aspect that Ugolini worked to substantiate.45 Zammit was not alone in bringing Malta’s heritage into focus, and notable among his countrymen who were involved in archaeological investigations at this time were Giuseppe Despott (1878–1936), Napoleon Tagliaferro (1857–1939) and Paul F. Bellanti (1852–1927).46

After Themistocles Zammit died in 1935, acting directors were appointed to the Museums Department who shepherded the collections through World War II. John Ward-Perkins briefly took up the position of the inaugural chair in archaeology at the then Royal University of Malta in 1939, an appointment which has been seen as a direct counter to the Italian cultural influence infiltrating Malta.47 War had a huge impact on the island generally, and the archaeological remains did not escape. Some sites came to light in the course of preparations for conflict, during works on the airfield, military barracks and the digging of shelters; others were presumably lost ‘unnoticed and unrecorded’ in the flurry of quarrying and building activity that took place during the war.48 Dr Joseph George Baldacchino was appointed director of the museum from 1947 to 1955, and after him, Charles, Zammit’s son, took up this post, having formerly served in various curatorial capacities in the archaeological section of the museum between 1932 and 1958.49 At the end of the war, a survey of the damage was made that included the ancient sites of Kordin and Tarxien, as well as damage to Roman-period buildings at Ta’ Kaċċatura near Birżebbuġa. Reconstructed pottery was reduced to sherds again in the damp storage conditions of the museum basement.50

A post-war programme to survey and bring structure to Malta’s prehistoric record came with funding from the Colonial Welfare and Development Fund. This project was undertaken by a large research team, guided by Stuart Piggott and John Ward-Perkins, and was brought to its conclusion by John D. Evans (Research Fellow, Pembroke College, Cambridge).51 During this period, David Trump (1958–63) and Francis S. Mallia (1959–71) were Curators of Archaeology at the Museum while its collections were ordered and catalogued and museum displays were put in place. Excavations undertaken at Skorba, Baħrija, Ta’ Ħaġrat, Kordin III and Santa Verna (Gozo) in the 1960s by Trump provided vital missing chronological links in the developing prehistoric sequence. Their combined efforts, assisted in no small part by the staff of the National Museum, established the prehistoric cultural scheme for the islands, a sequence that took shape from the 1950s (with variations in nomenclature and cultural adjustments over that time).52 The basic cultural framework came with the publication of Evans’ Prehistoric Antiquities of the Maltese Islands in 1971. Essentially, the sequence remains the accepted model.

Whatever perceived colonial overlay nurtured this British initiative, it was severely challenged by the arrival of the Italian Missione archeologica a Malta on the eve of Malta’s independence in 1964. The Italian excavation programme spanned 1963 to 1970, albeit initially focussing on the later remains (Phoenician, Punic and post-Punic periods) on the island at the sites of Tas-Silġ and San Pawl Milqi; in the second season, excavations also took place at Ras il-Wardija in Gozo.53 Hitherto, interest in the first millennium had been severely overshadowed by the preoccupation with the prehistoric period. The likes of Ward-Perkins actively lobbied against expanding research into this area, opting to maintain the strong focus on the prehistoric record which characterised the initial parameters of the funding.54 Not until the 1990s did independent research projects target the hundreds of Phoenician, Punic and Roman-period tombs that had been steadily documented throughout the twentieth century in particular. And these studies, I believe, were conducted outside of any contemporary political agendas.55

Development of radiocarbon dating put an end to any lingering diffusionist notions, sustained largely by distant cultural comparisons.56 Based on the new, scientifically generated absolute dates, it was found that many cultures in Western Europe which had formerly been linked with Near Eastern civilisations were significantly earlier. It was clear that distinct regional cultures had emerged independently. In an overview of these advances in archaeological research which appeared in the landmark study, Before Civilization: The Radiocarbon Revolution and Prehistoric Europe, Colin Renfrew clearly and sharply reset the research agenda.57 A new chronology was emerging that effectively stopped in its tracks the accepted mode of interpreting the past. As Renfrew pointed out, what remained were reasonably well-defined, area-specific cultural sequences, acceptable though circumscribed relative chronological links and restricted regional studies that were still valid.58 He outlined the challenge that remained: ‘We are left with an alarming void – a mass of well-dated artifacts, monuments and cultures, yet with no connecting interpretation of how these things came about and how culture change took place.’59

The wave of fundamental change also affected Malta’s long-accepted place in the ancient world. John Evans may have begun his work programme from the position that cultural trends permeated the Mediterranean from the Aegean and came specifically into Malta through Sicily, but by its end, he accepted the new chronological paradigm, reassessing the data accordingly. On the basis that Malta’s prehistoric cultures were not born of distant Aegean regions, Evans’ response was to mull over the implications of insularity and isolation on independent cultural development, which he explained in a paper with the evocative title, ‘Islands as Laboratories for the Study of Culture Process’.60 Regarding the prehistoric finds in Malta, Renfrew tackled the issue of cultural organisation and the implications of spatial distribution of the monuments in regard to territories. By looking to other regions, which developed ‘temple cultures’, he came to similar conclusions to those of Evans – that such independent cultural trajectories were ‘both possible and natural’.61 The door was opened to new theoretical models by which to interpret archaeological evidence for ancient cultures. Malta, with its remarkable prehistoric sites, has continued to provide particularly fertile ground for the application of new ways of interpreting the past – but more of this in the pages that follow.

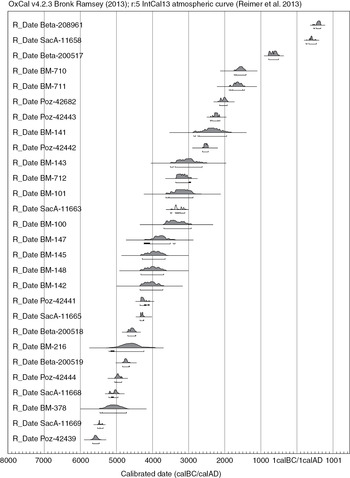

The necessity of accruing new dates to the existing body of data Renfrew saw, in the 1970s, as an essential way forward. Although radiocarbon dating has been available since the 1960s, the technology has not been applied as a matter of course to new finds in Malta, especially in the Bronze and Iron Age contexts (probably due to the high cost of processing rather than the absence of suitable samples). Even within the prehistoric era, much hinged on a handful of absolute dates from a few well-defined levels.62 Noteworthy is recent work carried out in the Xagħra Circle burial ground in Gozo that has generated a suite of nineteen new radiocarbon readings which have suggested some refinements for some phases (Tables 1.1 and 1.2 and Appendix A).63

Table 1.1. Radiocarbon dates from cultural contexts in Malta (for detailed listing see Appendix A)

Table 1.2. Radiocarbon dates from environmental contexts in Malta (for detailed listing see Appendix A)

From the closing decades of the twentieth century, the nature of governance of the islands’ ancient heritage has been thoroughly reviewed, culminating in the 2002 Cultural Heritage Act overseen by the Superintendence of Cultural Heritage organisation, which was established at the same time. The act applies to immovable and movable as well as intangible heritage in regard to the ongoing protection, conservation and promotion of a wide spectrum of Malta’s cultural assets. Within the organisation, there is a Committee of Guarantee, which liaises between relevant cultural heritage and the government agencies and Heritage Malta, overseeing operation of the provisions set out in the act and management of heritage assets and museums.64 No less important was establishment of the Malta Environment and Planning Authority (MEPA) in 2001, within which is the Heritage Planning Unit (HPU), which manages data and identifies heritage assets for protection.65 The resulting restructuring has permeated all aspects of the Maltese cultural record, and the digital age has made the workings of these agencies transparent. State of the Heritage Reports appear annually and on the web, replacing the Annual Report on the Working of the Museum Department. Regrettably, the Bulletin of the Museum was short-lived (1929–35); otherwise, detailed publication of past and new finds and fieldwork remains the one area which has not been developed. Malta’s unique record has been internationally recognised, with the prehistoric sites of Ħal Saflieni, Ġgantija, Ħaġar Qim, Mnajdra, Tarxien, Skorba and Ta’ Ħaġrat falling under the UNESCO Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural Heritage (established in 1972).66

Hand in hand with almost two decades of legislative reform and unprecedented restructuring of museum and cultural heritage practices, significant trends in research have led scholars to revisit key sites that were excavated decades ago. Documentation generated during fieldwork, museum archives and excavated material in museum stores, as well as the sites themselves, have been reassessed in the light of current archaeological practices and theoretic interpretations. Considering that many of these early investigations underpin the broad archaeological sequence constructed for the Maltese Archipelago, this focus on achieving higher definition and clarifying past discoveries is extremely worthwhile; Borġ in-Nadur,67 Ta’ Ħaġrat and Skorba68 have been the subject of such revisions. Similarly, archaeologists continue to revisit sites with a view to refining chronological sequences and acquiring additional data in line with current archaeological practice, for example, the Xagħra Circle (Gozo), Tas-Silġ and the Żejtun villa sites.

Despite the early archaeological exploration of the islands and their dominant place especially in general studies of the prehistoric period, many gaps in research have begun to be addressed only recently. Lithic material from the islands often was dismissed, possibly as it did not compare favourably with offshore industries.69 Fine sifting was carried out at Borġ in-Nadur in the 1920s by Margaret Murray, and some debitage from stone tool production was recovered, but such fine resolution was otherwise under-represented.70 Recent research into lithic material from past and modern excavations represents a marked step away from perfunctory listings and a focus only on the formal tools.71 There is, however, a similar need for research to be carried out on the entire prehistoric bone tool industry, as well as food-production implements (or tools used for other functions) such as pestles, mortars and grinding stones of any period.72 Excavation reports, too, though often slow to eventuate, now include a suite of archaeological and scientific analyses; most notable is the Xagħra Circle (Gozo) report that appeared in 2009 and Tas-Silġ (northern and southern sectors).73 The Xagħra Circle presented the first major analysis of human remains from a mass burial ground of the prehistoric period; it is the long-awaited counterbalance to the loss of data from the early excavations at Ħal Saflieni, about which we know comparatively little. There have been no major studies on human remains from Phoenician-Punic tombs in the islands. There is a backlog of unpublished material on Phoenician-Punic tombs and later catacombs excavated after the 1970s, mostly recovered through salvage operations. Field surveys have been undertaken; most remain unpublished or under-published, but finds from the joint Belgo-Maltese Survey Project in the north of Malta are very promising.74

Summary

The archaeological record for the Maltese Archipelago is complex and one of extremes. Research has been lopsided, dominated by investigations into cultures that produced monumental prehistoric architecture. Such sites were easy targets for the budding field of archaeology, and later, they presented ideal case studies for successive theoretical models which sought to explain how people lived and structured their communities. Fragile habitation deposits and signs of intensive land use over the millennia have left a challenging record. At times tightly packed stratigraphy occurs in key locations (such as Skorba and Tas-Silġ), while other sites are marked by meagre evidence that people once lived there. Ancient accumulations of human settlements which are characterised by mounds (tepes, tels, tells or höyüks) in the Near East are not apparent in the Maltese landscape. Modern human land use reflects a dramatic pattern of concentrated urban zones encroaching into age-old rural areas, which are characterised by small agricultural plots defined by dry stone walls. It is challenging to conceptualise a very different prehistoric terrain where settlements were smaller but probably more evenly dispersed across the islands or a scene where Phoenician-Punic urban development formed in central Malta and Gozo, interacting with outlying hamlets that grew around commercial hubs.

The early years of archaeological discussion were artefact based (especially focussed on pottery) in Malta, just as they had been in other regions.75 Such an approach has tended to be broad, typologically driven and, in Malta, hampered by a dearth of site-specific chronological discussions. Pursuit of past cultures in Malta throughout the history of its archaeological investigations has been influenced by the desire to compartmentalise major cultural phases defined for the islands, but the path of change is rarely clear-cut. In the modern era, the plethora of scientific analyses has opened up an array of possibilities to delve into the human story, from what filled the pot for the daily meal to the bigger picture of the genetic heritage of the population. Nonetheless, the definition of ancient cultures in the first instance rests on the material remains. While there is a trend towards downplaying the role of typological studies of artefacts in the scheme of building human history, environmental research, chemical, residue and use-wear in artefact analyses, recognition of spatial and chronological contexts of finds, identification of sources of raw material and research into production techniques continue to gather momentum.76 International interest in the islands’ prehistoric past has been reasonably steady over the course of the last century, but finds from the full spectrum of human occupation, spanning Bronze and Iron Ages as well as times of Roman influence, have continued to accumulate, and these need to be brought into the discussion to make full sense of each phase in its turn. What follows is an account of this remarkable record of human history.