Performed at Drury Lane and printed in The London Chronicle in 1757, Havard’s ‘Ode to the Memory of Shakespear’ positions its subject – a ‘Master-Genius’ who ‘reigns alone’ and cannot be threatened by ‘Fear, Usurpation, or Decay’ – as a kind of omnipresent cultural monarch and global colonizer.Footnote 2 Shakespeare’s dramatic achievement – which, as Havard puts it, soars sublimely ‘Above the Rules’ and rejects the classical unities of time, action, and place – is directly likened to Columbus’s exploration of the Americas and connected, approvingly, to a colonial project of political, cultural, and wartime hegemony. This use of Shakespeare as a symbol of global domination emerges as a distinctive and influential one during the Seven Years’ War, when, as Michael Dobson summarizes, he was ‘praised more and more insistently in terms of world exploration and conquest’.Footnote 3 By way of comparison, during the Nine Years’ War (1593–1603), the Exclusion Crisis (1679–81), and the Jacobite Risings of 1715 and 1745, Shakespeare is most conspicuously mobilized to reflect on political divisions within the nation, rather than transnational ones.Footnote 4 Increasingly politicized aesthetic debates fuelled a shift in emphasis and entrenched Shakespeare’s pre-eminence as a cultural combatant. While earlier writers, such as John Dryden, felt compelled to excuse and/or adapt Shakespeare in response to a resurging interest in classical rules that emanated in particular from France, the escalating political tensions and state of war between Britain and France from 1756 to 1763 prompted, as Dobson, Frans De Bruyn and others have explored, confident declarations of Shakespeare’s natural genius and the sublimity of his writing.Footnote 5 These ideas were not new, but reached uncharted heights during this conflict and in its aftermath. Voltaire was a pivotal figure in this shift. He had a long-standing ambivalent relationship with Shakespeare, but once he started pointedly to assert the superiority of French writers, such as Pierre Corneille, over Shakespeare, the response in Britain crystallized: Shakespeare was elevated on a global stage as a representative of Britain’s cultural and political dominance – and crucially, as this chapter argues, in ways that served to construct narratives of conflict and commemoration.Footnote 6 Although they do not articulate a political application as emphatically as Havard’s ode or involve production agents with direct political designs, performances of Shakespeare’s plays at the Theatres Royal in London, especially John Rich’s Henry V in 1761, encourage a similar reading that aligns Shakespeare, his historical subject, and Britain’s new king, George III, with a wartime narrative of victory and commemoration through theatrical spectacle.

The Seven Years’ War (1756–63) was one of the first truly global conflicts, spanning five continents and three oceans, and involving a smorgasbord of different political issues and shifting alliances that can be broadly divided into two main coalitions in Europe: one led by Britain in alliance with Hanover, Prussia, and Portugal, and the other led by France in alliance with Austria, Russia, and later Saxony, Sweden, and Spain.Footnote 7 In Europe, skirmishes first broke out when the French captured Menorca in June 1756 and when Prussia invaded Saxony in August 1756, while in the Americas, tensions erupted over French and British colonial disputes, and in India, renewed conflict broke out over French and British settlements. Britain’s official entry into the European conflict arose through George II’s Hanover connection, which divided public opinion as some believed that the monarch’s German sympathies compromised British interests.Footnote 8 At the time, the most useful face of the conflict for inspiring confidence and support in Britain was, by far, the wars in the North American colonies and the promise they carried of imperial expansion. It is in this cause, as suggested by Havard’s ode, that Shakespeare is most consistently employed. Victories in the Americas were regularly used to divert attention away from dissatisfaction with the continental war. For example, the anonymous print ‘The Applied Censure, or Coup de Grace’ (1759) aims to justify the conflict’s ongoing costs by appealing to popular enthusiasm for Britain’s colonial acquisitions: a horse symbolizing Hanover kicks down the king of France and secures stability in Europe, leaving the British lion to attack the French cock in the Americas and force the surrender of the colonies. The lion is grateful for this diversion from Hanover: ‘O Pretty! O Pritty! Thou hast save[d] me a great deal of labour & trouble, I have crush’d the Cock & secured America.’Footnote 9

Instrumental in this promotion of conquest was the Whig politician William Pitt the Elder, who had initially opposed intervention in the Hanover conflict. In a much-criticized volte-face, he formed a coalition in 1757 with the Old Corps Whig Thomas Pelham-Holles, first Duke of Newcastle (Prime Minister between 1754 and 1756 and between 1757 and 1762), that lasted for most of the war, with Pitt as secretary of state and leader of the House of Commons.Footnote 10 One of Pitt’s key oratorial themes for influencing government and public opinion was to emphasize the glory of Britain’s colonial achievements, rather than scrutinize the divisive continental campaign.Footnote 11 Wartime reporting often attributed victories in the war to Pitt, as if he were directly responsible.Footnote 12 Dedications to Pitt also abounded in new publications, including the novel Chrysal, or The Adventures of a Guinea (1760), which claimed that this dedicatory act seemed almost mandatory and that neglecting to do so would be ‘a breach of the general gratitude, which, at this time, swells every honest heart, in Britain’.Footnote 13 Similarly, Tobias Smollett quipped in a letter to John Harvie on 10 December 1759 that ‘Mr Pitt is so popular that I may venture to say that all party is extinguished in Great-Britain’.Footnote 14 Shakespeare’s wartime import – as described and applauded in Havard’s ode – is in the service of the broad war aims and narrative of colonial achievement that were consistently propagated by Pitt and his supporters.

Pitt’s strategies seem to have been effective at specific stages of the conflict. Public support for the wars was high in 1759 – dubbed the ‘Year of Victories’ – a time that witnessed successes at Fort Duquesne (in November 1758, but not reported in Britain until January 1759), Fort Ticonderoga, Fort Niagara, Guadeloupe (in the West Indies), and, most significantly, Quebec, which led to British control of New France. An atmosphere of celebration seems to have prevailed in Britain: bell ringing, illuminations, fireworks, bonfires, and processions throughout the country greeted the news of wartime victories. In a letter to George Montagu on 21 October 1759, Horace Walpole remarked that ‘[o]ur bells are worn threadbare with ringing for victories […] I don’t know a word of news less than the conquest of America’.Footnote 15 An outpouring of congratulatory prints, poems, and addresses (including eighty presented to George II, enough, as Walpole quipped, ‘to paper his palace’) responded enthusiastically to the news of success in the Americas.Footnote 16 The House of Commons became, according to Walpole, ‘a mere war-office’, and the rhetorical strategies of Pitt and George II made it look ‘as if we intended to finish the conquest of the world next campaign’.Footnote 17 These speeches, publications, and public shows of celebration demonstrate, as M. John Cardwell summarizes, ‘how Britain’s deepening commitment [to the war] was overshadowed by the glory of its imperial and maritime triumphs’ and support Linda Colley’s description of it as the ‘most dramatically successful war the British ever fought’.Footnote 18 While public and parliamentary opinion was far from united or consistent – and divisions increased as the war’s costs and duration became prolonged – public shows, cultural figures and texts, and the news media helped to construct and circulate optimistic narratives of national triumph that could be seen to reflect favourably on the war’s progress.

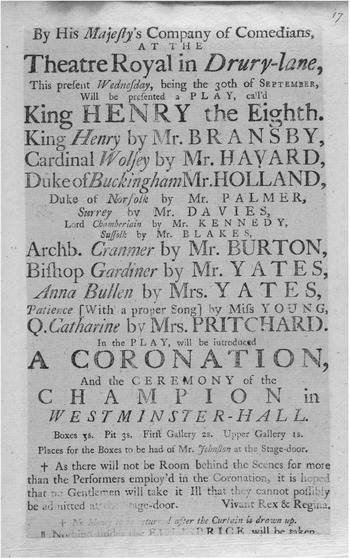

Shakespeare – as performance, text, and cultural figure – was instrumental in this process, and was often presented as a combatant against France within new texts and pamphlets. During this conflict, images of political and cultural domination are, as suggested by Havard’s ode, inextricable. Edward Young’s Conjectures on Original Composition (1759), a treatise that applauds the natural geniuses of Shakespeare, Bacon, Newton, and Milton, claims that ‘all the winds cannot blow the British flag farther, than an Original spirit can convey the British fame; their names go round the world; and what foreign Genius strikes not as they pass?’Footnote 19 Similar to Havard’s ode, artistic and scientific achievements, involving, as the treatise puts it, a daring disregard for classical rules of composition and imitation, are indicative of political domination on a global scale and seem to foresee future British successes during the conflict. The mobilization of Shakespeare as an opponent of France, in particular, was shaped by Voltaire’s engagement with the writer and, as Kathryn Prince put it, his ‘antipathy towards the English enthusiasm for Shakespeare’.Footnote 20 During the height of the conflict, Voltaire made a sustained attack on the absurdities of Hamlet in Appel à toutes les nations de l’Europe (1761), suggesting that, as Prince outlines, England was neglecting Enlightenment cosmopolitan principles in favour of regressive nationalism.Footnote 21 According to this reading, Britons were using Shakespeare during a global war as a means of asserting national superiority and therefore fracturing an elite and transnational cosmopolitan culture. Testament, perhaps, to Voltaire’s Enlightenment principles is the fact that he asked Pitt in 1761 to subscribe to his edition of Corneille’s letters, claiming that it is ‘worthy of the greatest ministers to protect the greatest writers’, a request that, in the midst of the war, straddles conflict lines.Footnote 22 Voltaire directly promotes the separation of culture from wartime loyalties in his letter to Pitt: ‘[w]hile you [i.e. Pitt] weight the interets [sic] of england and france, your great mind may at one time reconcile Corneille with Shakespear’.Footnote 23 In contrast, what could be seen as a symbolic combat between British and French cultural authorities took place in David Garrick’s new pantomime Harlequin’s Invasion, first performed in December 1759 at Drury Lane. It concludes with Shakespeare’s ghost as a deus ex machina that rises at the end to announce victory over the French Harlequin. The playscript’s transfer of authority could be read along staunch nationalist lines – as ‘Shakespear Rises: Harlequin Sinks’ – and, in the pantomime’s final moments, a procession of characters from Shakespeare’s plays enter to praise the ‘Thrice happy […] Nation that Shakespear has charm’d’ (see Figure 1.1). Although this reading can, as discussed later, be challenged, some early audiences clearly saw this pantomime as marking out a cultural battleground, and, indeed, its main events were later adapted into another pantomime that similarly positions this conflict along national lines: Shakespeare versus Harlequin.Footnote 24 While the examples so far all testify to Shakespeare’s use within new texts, productions of the plays themselves also resonate with the ongoing conflict in ways that posit support for British war aims. The fact that France was Britain’s consistent wartime enemy during the eighteenth century ensured that many of Shakespeare’s histories were readily adaptable as patriotic wartime fare, given the antagonism between the two countries that feature in these plays. Henry V was, as Emma Smith points out, staged every year during the conflict, a repertory choice that could reflect public enthusiasm for the dramatization of famous historical victories against France.Footnote 25

Figure 1.1 Final scene from David Garrick’s Harlequin’s Invasion: A Christmas Gambol.

Support for the wars taking place in the Americas and Europe was not unanimous, however, and some expressed doubts over their justification, including Samuel Johnson in his ‘Observations on the Present State of Affairs’:

The general subject of the present war is sufficiently known. It is allowed on both sides, that hostilities began in America, and that the French and English quarrelled about the boundaries of their settlements, about grounds and rivers to which, I am afraid, neither can shew any other right than that of power, and which neither can occupy but by usurpation, and the dispossession of the natural lords and original inhabitants.Footnote 26

If, as Johnson describes, the war was merely to acquire power and seize colonial possessions, then its justification cannot be defended, an evaluation that alludes to the principles of just war theory that invalidate the legitimation of expansionist wars. Set against these dissenting views, Shakespearean productions offer a useful point of access for understanding the appeal of conquest and its rhetoric, and the power of public spectacle. Of all the wartime contexts considered in this book, Shakespeare’s onstage and print mobilization during the Seven Years’ War could be described as the most united: Shakespeare emerges as a cultural figurehead for the promotion of British victory. While there are growing fractures in public support for the conflict, as indicated by Johnson’s account, Shakespeare’s currency is most firmly connected to the prosecution of the war, the celebration of its military victories, and the construction of confident wartime narratives – a position reinforced through the conditions of production at the Theatres Royal and through the dominant emphasis of printed political texts that enlisted Shakespeare in their cause. Although production agents at the Theatres Royal were not themselves political actors, their commercial interests and the coincidence of the war with the coronation of a new king, George III, contributed to the wartime significance of their Shakespearean productions that seem to promote and authorize conquest.

In order to address these points, this chapter offers a focused discussion of two important, but overlooked, productions at the Theatres Royal, London in late 1761: David Garrick’s Henry VIII, acted seven times between 30 September and 9 October 1761 at Drury Lane, and John Rich’s Henry V, which ran for an unprecedented twenty-three consecutive nights, starting on 13 November, at Covent Garden.Footnote 27 The latter was, as Charles Beecher Hogan points out, ‘the longest [run] accorded to any play by Shakespeare in the eighteenth century’.Footnote 28 These performances reveal how Shakespeare could be used to present the ongoing conflict as a story of British conquest, authorized by the monarch, that promises future victories and political stability, while, at the same time, testifying to an interplay of competing agendas through their different agents of production and reception. The productions prioritize the representation of royal spectacle and respond to the recent coronation of George III on 22 September 1761, which are key factors directing their wartime application. Although George had been king for almost one year (his grandfather, George II, died on 25 October 1760), his public coronation did not take place until the following year. Every performance of Henry V featured The Coronation as an afterpiece, and a similar, although less elaborate, spectacle appeared at Drury Lane. In these productions, the staging of monarchical spectacle and/or historical conquests led by the monarch seems contemporarily attentive, but contrasts with the political reality of 1761, when George III was actively promoting peace in opposition to the efforts of Pitt as leading war minister. The productions anticipate the commemoration of Britain’s wartime colonial acquisitions in a way that erases – or at least minimizes – the emerging divisions that surrounded the war’s conduct and profound costs. Unlike later state mobilizations during the Second World War, for example, these productions were not sponsored by the government or the state more broadly – although Pitt and others associated with the ‘Leicester House’ circle had earlier patronized the work of contemporary playwrights, including John Home’s Douglas (1756), in an effort to renew and influence ‘public spirit’.Footnote 29 The Shakespearean productions reflect the responses of different publics – of theatrical practitioners and audiences – to the conflict, but they do share a striking parallel with the strategies of Pitt and his supporters, albeit repurposed in a distinctive way that positions the new king as a symbolic authorizer of the conflict and reveals the power of spectacle to rewrite recent history.

Staging Spectacle in 1761

Commemorations through cultural appropriation, to draw on Supriya Chaudhuri’s work, ‘negotiate multiple temporalities’, drawing together ‘different kinds of time – the “universal” time of the classic, the sedimented time of history, and the time of the reformed present’ for the purpose of constructing a unified and cohesive narrative.Footnote 30 Shakespeare has proved to be a powerful cultural figure through which various communities or groups have staged commemorative acts and negotiated their wartime identities. But, as Monika Smialkowska and Edmund King discuss in their collection Memorialising Shakespeare, the process is ‘not always straightforward, since it involves not only finding similarities but also smoothing over differences between Shakespeare’s period and the groups’ own historical realities, as well as reconciling the often conflicting needs of the individuals within the groups themselves’.Footnote 31 While Coppélia Kahn and Clara Calvo describe the 1623 Folio as one of the earliest acts of Shakespearean commemoration – as a publication venture designed to memorialize and monumentalize the dramatist – most critical work on commemoration focuses on later events, sometimes taking Garrick’s 1769 Jubilee in Stratford as a starting point.Footnote 32 I concentrate, however, on two earlier productions – Garrick’s Henry VIII and Rich’s Henry V – to show how they represent a nascent form of Shakespearean wartime commemoration. Not only do these productions reveal an interest in Shakespeare’s cultural capital (which can also be witnessed in the strategies underpinning the First Folio publication and Garrick’s Jubilee), they also carry additional wartime currency that positions them at a crossroads of multiple acts of commemoration that seem to consign the ongoing wars to the past.

The plays’ multiple temporalities – that of their historical subject matter, their identity as early modern cultural texts, and their eighteenth-century coronation spectacles – contribute to the multi-layered acts of commemoration that they incorporate. Both plays dramatize English history and, in the case of Henry V, a famous wartime victory against the French that could be applied to the contemporary wars as a national history of military success. Both Garrick’s and Rich’s productions featured a replica of George III’s coronation, introducing another temporality that brings the histories into the present and underscores their contemporaneity. A consequence of audience demand, their sustained performance runs – a modest seven times for Henry VIII, but a staggering twenty-three consecutive times for Henry V – make them repeated performance events that solidify their import as wartime acts of memorialization that celebrate Shakespeare as a national dramatist and George III as royal authority.

To show how these productions – through their design, but also the circumstances of their production and reception – establish a triumphant narrative of conflict that glosses over escalating uncertainty about the war’s methods and progress, this section analyses several spectacles staged in late 1761: the two Shakespearean plays and their coronation replicas, George III’s actual coronation on 22 September 1761, and the burning in effigy of war minister William Pitt following his sudden resignation in October 1761. While Pitt, as already discussed, had been enthusiastically praised as a successful war leader and strategist who brought glory to Britain, his reputation and the wartime optimism of the ‘Year of Victories’ were somewhat tarnished by the time of his resignation, which was on account of disagreement over the conduct of the war and other government ministers’ push for peace. The Shakespearean productions at Drury Lane and Covent Garden offer an alternative wartime narrative: George III, as opposed to Pitt, becomes directly linked with Britain’s pursuit of military conquest, which is somewhat at odds with the new king’s investment in peace. The productions capitalize on public enthusiasm for the coronation, with the result that Garrick’s and Rich’s replicas connect George III to the promotion of the war effort, a displacement that is especially apparent in the performance run of Henry V at Covent Garden. The productions resemble a commemorative act, whereby the political realities and complexities of the war are reshaped and simplified to boost audience morale and to reflect uncritically on its progress. Indeed, as patent theatres, both Drury Lane and Covent Garden were closely connected to the king. They relied on him for support and the renewal of their patents, a condition of production that encourages an interpretative link between their theatrical offerings and the royal patron. Although George III regularly attended the public theatres, none of the performances of Henry VIII and Henry V in autumn 1761 took place by royal command or were seen by him. The new king is solidified as an ‘authorizer’ of these theatrical events and wartime narratives even – and perhaps especially – through his absence.

The Coronation and Henry V

The official coronation of George III took place on 22 September 1761, a spectacle that had been planned for almost one year. It prompted an outpouring of panegyrics to the king and his new wife, Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, whom he married on 8 September 1761. The Public Advertiser was awash with notices for pamphlets and prints that marked the occasion, including an account in The London Magazine that, it claims, offers the ‘fullest and most satisfactory Relation of the whole Ceremony, Form, and Conduct of the Royal Coronation’, alongside a ‘curious Enquiry into the Causes of our having a Champion to appear’.Footnote 33 The inclusion of the royal Champion, a hereditary office that had descended through the Dymoke family since 1377, was a regular feature of monarchical coronations – specifically at the coronation banquet – since at least the reign of Richard II. It involves the ceremonial appearance of the King’s (or Queen’s) Champion as a fully mounted knight, who then issues a combat challenge to anyone present who disputes the monarch’s right to rule.Footnote 34 In addition to this account, the September issue of The London Magazine also included a range of ‘eyewitness’ reports, an article showing the order and formation of the coronation procession, and a series of loyal poems suggestive of the public interest and patriotic fervour that the coronation ignited.Footnote 35

This royal enthusiasm does not necessarily indicate support for the ongoing wars of which George III was the new royal figurehead and under whose name British forces fought. The coronation could be seen as a spectacle that symbolized the clear shift in the conduct of the Seven Years’ War that had taken place on the king’s accession one year earlier, a political shake-up that had, as Cardwell summarizes, ‘profoundly affected the balance of power within the government and its attitude’ towards the war.Footnote 36 Ministers had competed over who would curry favour with George III, a scrambling for influence and position in an era before the emergence of clear-cut political parties. Samuel Butler’s ‘The Quere?’ (c. 1760), for example, shows the figure of Britannia debating the best type of coal to ‘heat a British Constitution’, the options being ‘Pitt, Newcastle, or Scotch-coal’, which correspond to the three leading political figureheads: William Pitt; the Duke of Newcastle; and John Stuart, third Earl of Bute.Footnote 37 It was Bute who secured his position as George III’s political favourite, and together they made clear their aim to establish peace and bring an end to the war’s escalating costs. Unlike his grandfather, the new king was less interested in maintaining Britain’s wartime commitments to Hanover and was hostile to the ongoing continental conflict.Footnote 38 The Pitt-Newcastle ministry, which had sustained the war thus far, started to crumble and, in his first declaration to the Privy Council on 25 October 1760, George expressed his firm desire for a resolution to this ‘bloody and expensive war’.Footnote 39 On this point, Pitt came into direct conflict with the king. He insisted that the comment was emended in the printed edition of the speech to ‘an expensive but just and necessary war’ – an editorial act of censorship that offended the king and indicated their diverging attitudes towards the conflict.Footnote 40 Pitt’s careful choice of adjectives reveals that he sought to link the conflict with the principles of just war theory, by claiming that its cause is justified and ‘necessary’, and implying that it was a last resort, rather than an acquisitive project with a primary aim of colonial expansion.

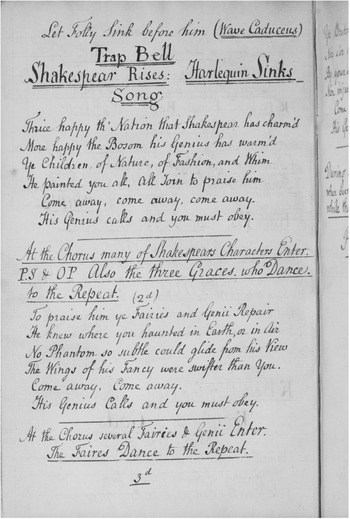

The spectacular dramatization of royal authority and military victory in Rich’s production of Henry V was intensely topical, tightly intertwined with both the recent coronation of George III and Queen Charlotte and with debates surrounding the ongoing war. While the coronation of earlier monarchs, including George I and George II, had also been commemorated through publications and the onstage performance of scenes or music from them, Rich invested considerable time and money in the development of his version, which proved successful with audiences.Footnote 41 Through its initial exclusive pairing with Henry V and the fact that its staging seems to blur the boundary between Shakespeare’s play and the contemporary royal spectacle, the replica positions George III as a figurehead for Britain’s conquests – both past (at the Battle of Agincourt) and present (during the Seven Years’ War). This effect is solidified through the thematic coherence of the performance event, which did not include any other theatrical piece. During the eighteenth century, productions at the Theatres Royal in London almost always consisted of a main play followed by an afterpiece, which was often a pantomime, farce, or musical performance that could offer a pronounced shift in tone and style from the first piece. One year before, on 5 May 1760 at Covent Garden, Henry V was performed with a series of dances between the acts – ‘The Drunken Peasant’ in Act 2, ‘The Fingalian Dance’ in Act 3, and ‘The Lamp-Lighters’ at the end of the play, all of which accompanied other main plays during the season – and was followed by the farce A Duke and No Duke as an afterpiece.Footnote 42 In contrast, pairing The Coronation with Henry V and excluding all other theatrical pieces helped to preserve an atmosphere of monarchical and national triumph. It emphasizes the English victory over the French that concludes the play, breaking down the threshold between the main theatrical piece and afterpiece. This blurring is also suggested by the playbill for the first performance (see Figure 1.2), which contains a cast list and describes the production as ‘the History of King Henry the Fifth, With the Conquest over the French at the Battle of Agincourt […] To which will be Added The Procession from the Abbey at the Coronation, With the Representation of Westminster-Hall, and the Ceremony of the Champion’. It concludes with the standard Latin tag ‘Vivant Rex & Regina’.Footnote 43 Given that Henry V ends with the ‘Conquest over the French’ and the promise that Henry’s heirs will succeed to the French throne, the eighteenth-century coronation replica could be seen as a symbolic ceremony that legitimizes these gains and links the two monarchs, George III and Henry V. Indeed, the ceremony of the royal Champion explicitly staged the legitimation of the monarch. The Champion calls out for any challengers who dispute the new king’s right, a re-enacted ritual at Covent Garden that, appended to a play about the conquest of France, seems to extend this claim of authority over France and, by extension, over Britain’s new wartime possessions.

Figure 1.2 Playbill for Henry V, performed at Covent Garden on 13 November 1761.

By conjoining his version of the coronation with Henry V, Rich’s production as a whole seems to take on a commemorative role, starting to authorize wartime narratives that link the act of making victorious war with the king, rather than with parliament and its leading war minister, Pitt. Its interpretative impact was increased through performance repetition and frequency. The splicing of Henry V and The Coronation continued for twenty-three consecutive days (from 13 November to 9 December 1761). No play of Shakespeare’s had ever received a performance run of this length, nor would another occur again during the eighteenth century. The length of the run was determined by audience demand and approval, a point that highlights the significance of reception agents within the development of wartime drama. While Garrick staged his version only eight days after George III’s coronation, Rich took much longer in order to reproduce the event as minutely as possible. As Phyllis Dircks describes, Rich had distinguished himself as the ‘originator of English pantomime’ and tended to introduce extravagant costumes, scenery, and staging innovations into his productions.Footnote 44 The Coronation was clearly a lavish spectacle, promoted in The Public Advertiser for three consecutive days (10–12 November) before its opening on 13 November, and, according to Thomas Davies, Rich’s version ‘fully satisfied [the public’s] warmest imaginations’, even though the ‘expectations of the public had been much raised’.Footnote 45 Extant accounts in the Winston Theatrical Record reveal high takings from the first performance on 13 November (£244 7s) to 26 November (£230 18s), when the Winston record ceases.Footnote 46 All the intervening performances, with the exception of one on 20 November, brought in well over £200 per night, which exceeds the takings for other plays staged at Covent Garden at a similar time.Footnote 47

Had the theatrical (and political) conjunction of Henry V and George III’s coronation not proved popular, one or both of the pieces would have been rotated out of the schedule. The former eventually was: on 11 December, 2 Henry IV (alongside The Coronation) replaced Henry V, offering an alternative main play that features the same central character, another military victory (over, in this case, the rebellious English lords), and the coronation of Prince Hal as Henry V in the play’s final scene.Footnote 48 The two coronations – of Henry V within the play and of George III in the afterpiece replica – again encourage an interpretative connection between the two monarchs. This strategy to revive audience interest appears to have worked: 2 Henry IV was staged for a total of eleven nights in December 1761.Footnote 49 The Coronation was also performed on 28 December with Richard III, on 29 December with Henry V, and on 30 December with King John. These patterns continue in January 1762: The Coronation was performed another seventeen times, with one of four Shakespearean histories – Henry V, 2 Henry IV, King John, or Richard III.Footnote 50

Although Rich oversaw the initial design of The Coronation and its performance with Henry V, he was not the only production agent involved, and he did not have any influence over these later repertory combinations or over ongoing tweaks to the productions as the performances continued. On 26 November, twelve days into the run of Henry V, Rich died at his home next to the theatre in Covent Garden, during, as Thomas Davies recalls, ‘the heighth of the public eagerness to see [The Coronation]’.Footnote 51 The management of Covent Garden passed jointly to Rich’s widow, Priscilla, and Rich’s son-in-law, John Beard, who was an actor and singer.Footnote 52 While we often associate a production’s manager or director, leading actor, and writer with positions of prime agency and influence, these roles could be in flux and a range of other production and reception agents contribute to its development. For the company’s new managers, Shakespeare’s histories were also deemed to be the most suitable theatrical companions for a replica of George III’s coronation, a repertory decision that actively links Shakespeare with the staging of royal authority. While Garrick’s version of the coronation (discussed later) accompanied plays of different theatrical genres and by different writers, The Coronation at Covent Garden was only ever staged with one of Shakespeare’s English histories and could be seen to reinforce the nationalistic impulse that Voltaire criticized among British uses of ‘Shakespeare’.

Returning to the initial production run of Henry V, one crucial aspect of its design that helps to emphasize a triumphant narrative of military conquest is the absence of all the Choruses, which marked a change in theatrical practice. None of the playbills or advertisements lists the part of the Chorus, and some reviews discuss the significance of its omission directly. Earlier in the war, performance notices and playbills for Henry V up to 1760 include the Chorus, a part played, for example, by ‘Mr Ryan’ during a performance on 5 November 1757 that was staged by ‘Command of his Royal Highness the Prince of Wales’ – the future George III.Footnote 53 Through its omission in 1761, the performance text recalls the play’s first quarto edition of 1600.Footnote 54 As critics of the folio and quarto versions of Henry V have independently explored, the Choruses (which were printed for the first time in the 1623 Folio) can serve to complicate a celebratory interpretation of Henry’s victories against the French and introduce a note of critical distance through the discrepancies that arise between the Chorus’s version of events and the realities of the French expedition staged in the surrounding scenes.Footnote 55 The 1761 production removes this ongoing tension between retrospective narrative and wartime experience and creates a play that is narrowly focused on the pursuit of victory.

The evidence of the text used for performance suggests that local emendations also concentrate attention on the aims of foreign conquest and remove moments of comic relief and critical reflection. There is, however, some uncertainty, in the absence of a surviving promptbook, about the script used in 1761, making it difficult, as Emma Smith cautions, to discuss specifics of the production and its design with confidence.Footnote 56 It is likely that the script resembled the text published in John Bell’s acting versions of Shakespeare’s plays printed in 1773/74 from, as his editions advertise, the prompt books at Covent Garden and Drury Lane and accompanied by commentary notes from Francis Gentleman. The title page of Henry V (1773) claims that the printed text is ‘As Performed at the Theatre-Royal, Covent-Garden, Regulated by Mr. Younger, Prompter of that Theatre’ and contains a cast list that features many of the actors from the 1761 production in the same roles.Footnote 57 Because Gentleman, the plays’ somewhat idiosyncratic commentator, also seems to have edited the plays and, as Smith puts it, prescribed, rather than just described, their performance on stage, Bell’s acting editions are not straightforwardly documents back to stage. Bell’s version of Henry V nevertheless offers the closest approximation of the 1761 Covent Garden production and draws attention to several significant textual cuts.Footnote 58 For example, Princess Katherine’s role is much reduced. The wooing scene in Act 5 is shortened, and the language-learning scene (Act 3 Scene 4 in modern editions) is omitted – although, as Hogan shows, the part of Katherine’s lady-in-waiting, Alice, does not appear in eighteenth-century cast lists, which suggests that the language scene was not regularly staged in any production.Footnote 59 Other textual changes also serve to focus attention on the play’s military plot. Speeches are shortened to end on an abrupt and confident declaration of military action. When Henry addresses his nobles, prior to the entrance of the French ambassador in Act 1 Scene 2, he concludes tersely and determinedly:

Shakespeare’s text(s) include another eight lines that reflect on the process of writing history and the possibility of failure and death in the pursuit of military glory – that, in failure, their bones will lie ‘in an unworthy urn, | Tombless, with no remembrance over them’ (1.2.228–29) – a qualification of confidence in victory that is absent from the acting edition.Footnote 61

Other changes lessen the violence of war and improve Henry’s character. The king’s brutal address to the citizens of Harfleur contains significant cuts, including the vivid imagery of ‘mowing like grass | Your fresh fair virgins and your flow’ring infants’, who will be ‘spitted upon pikes’, while ‘the mad mothers with their howls confused | Do break the clouds’ (3.3.93–94, 118–20).Footnote 62 Some changes may have been prompted by a recognition of the war’s growing costs in terms of lives and finances: Henry’s local comment (in both quarto and folio versions) that he ‘doubts not of a fair and lucky war’ as now ‘every rub is smoothèd on our way’ does not appear in Bell’s edition.Footnote 63 Similarly, Henry’s warning to Canterbury before the Archbishop delivers his justification of the French war – that ‘never two such kingdoms did contend | Without much fall of blood, whose guiltless drops | Are every one a woe, a sore complaint’ – is omitted.Footnote 64 We cannot, however, confirm when these textual changes took place or if they were intended, within a wartime context, to construct a historical fantasy about military success against the French. The cuts in Bell’s edition also serve a practical purpose: they create a shortened acting version and accommodate the company’s staging requirements. They do not necessarily have a deliberate political design, but the changes nevertheless have the effect of simplifying, amplifying, and approving the aims of war within the play and its antagonism towards France.

Rich’s production offers a freshly contemporized version of Henry V, achieved through the king’s centralized and airbrushed representation and the coronation afterpiece. The yoking together of Shakespeare’s play and a replica of the recent spectacle conflates the two monarchs, Henry V and George III, and the temporally and geographically distant victories at Agincourt and those of the Seven Year’ War – of which the conquests of Quebec (1759) and Montreal (1760) were perhaps the most widely reported and would lead to Britain’s acquisition of New France as part of the Treaty of Paris that finally ended the war in 1763. At Covent Garden, the removal of the Choruses and the addition of The Coronation ensure that the play functions as a vehicle for optimistic reflection on the ongoing war that echoes the representation of Henry V in other contemporary publications. For example, a ballad printed in 1760 – ‘King Henry V, his Conquest of France’ – presents the Battle of Agincourt as a jovial adventure in which English soldiers marched with ‘drums and trumpets so merrily’ and ‘kill’d ten thousand of the French’, while ‘the rest of them they ran away’, constructing a (predictable) contrast between English valour and French cowardice.Footnote 65 Surviving evidence from reception agents for the 1761 production at Covent Garden – such as the following review from St James’s Chronicle – offers a similar reading of the theatrical spectacle, drawing attention to continuities between print and stage mobilizations of Shakespeare during this conflict:

Henry the Fifth still continues to beat the French every Evening at this Theatre [i.e. Covent Garden]. We cannot but applaud the Sagacity of the Performers in omitting the Chorusses which Shakespeare has annexed to this Historical Piece; since they would at present appear lame and mutilated, for want of an additional one on the grand Ceremony that now concludes the Piece: A Deficiency, which arose from its never having once entered the Brain of the Poet, that this Play would ever be concluded with a Coronation.Footnote 66

This review not only confirms that the omission of the Chorus was an innovation of this production (relative to recent staging patterns and not the entire performance history of the play), it links the production’s merits to the concluding coronation. The latter ceremony secures the reviewer’s praise and surpasses the Choruses that Shakespeare supplied. Rather than encouraging critical reflection, the Choruses – for this reviewer – approve the play’s conquests, but appear ‘lame and mutilated’ next to the ‘grand Ceremony’ that now ends the play and more clearly puts forward an aggrandizing wartime narrative. Indeed, the impact of the play is suggested by the review’s opening line – that ‘Henry the Fifth’ (which could apply to the monarch or to the play as a whole) ‘continues to beat the French every Evening’. This comment is particularly telling because of its multiple applications: it not only indicates the repetition of the production and its success with audiences (outperforming plays by French dramatists, such as Voltaire’s Alzira, or Spanish Insult Repented, last performed in 1758 at Covent Garden), but also conflates the dramatization of a fifteenth-century victory with the ongoing battles against the French in the Seven Years’ War. It is a re-enactment that seems to reflect optimistically on continuing contemporary successes. The elaborate spectacle of The Coronation, the emendations to Shakespeare’s text, and the repetition of the Covent Garden production position the outcome of the French wars as predetermined and triumphant, limiting the production’s potential to offer a critique on war. It seems to authorize – before the conclusion of the conflict – a narrative of Britain’s participation: the victories have brought glory and colonial gains to the nation, and the monarch is the author of these successes.

This theatrical event, however, elides George III’s investment in peace and Pitt’s former influence as Secretary of State and war advocate. As already mentioned, the accession of the new king precipitated a change in Pitt’s political fortunes and the war’s conduct. Substantial peace negotiations started in May 1761, and, by this time, many politicians inclined towards peace, including Newcastle and John Russell, fourth Duke of Bedford. Pitt himself was willing, in response to parliament’s and the public’s growing desire for an end to the conflict, to negotiate a settlement.Footnote 67 He was nevertheless insistent that the terms of the peace recognize Britain’s military successes during the war that he had so earnestly pursued.Footnote 68 Complicating the negotiations still further was the fact that France formally ratified an alliance with Spain through the Bourbon Family Compact on 15 August 1761. This alliance made a renewed war with Spain seem likely, and Pitt pushed for Britain to retaliate by initiating a military strike. When other members of the Cabinet refused, Pitt resigned, a shock development that the ministry formally announced on 10 October.Footnote 69 Public interest was widespread, and publications thought to disclose information about Pitt’s resignation were seized upon, sometimes mistakenly. In a letter to Philip Yorke, Viscount Royston (later second Earl of Hardwicke), Reverend Thomas Birch reports that Edward Young’s Resignation, which is ‘a religious address to Mrs Boscawen on the death of her husband’, now ‘sells much on acc[oun]t of the title, being thought to mean a political Resignation’.Footnote 70 Newspapers revealed further details of Pitt’s departure, including his grant of a peerage and an annual pension of three thousand pounds. These particulars sharply divided public opinion. Some saw Pitt’s resignation and acceptance of the pension as a betrayal of his principles and an indication of his personal avarice for global conquest in the name of ‘Britannia’.Footnote 71 William Hogarth, for example, satirizes the contrasting policies of Pitt, George III, and Bute in his engraving ‘The Times’ (1762; see Figure 1.3). A figure representing Bute (and displaying on his sleeve the initials ‘G. R.’ to indicate the king’s support) attempts to extinguish a fire, symbolizing the ongoing war, in a chaotic London street. The scene includes a globe of the world, engulfed in flames, which Bute is hosing with water, whilst Pitt (identifiable by the millstone around his neck, symbolizing the pension and marked ‘3000 £ per annum’) strives to preserve the global conflict by fanning it with bellows. Pitt is presented as a warmongering advocate for conquest, while Bute and George III are invested in peace. Formerly championed as a strong wartime leader and compared to Elizabethan military heroes, including Robert Devereux, second Earl of Essex, Pitt provoked antagonistic public responses and spectacles (although he continued to have his defenders).Footnote 72 Just one week after his resignation and two days after it was formally announced, Richard Rigby reported in a letter to John Russell, fourth Duke of Bedford, that ‘Mr Pitt is to be burnt in effigy to-night in great pomp in the city [i.e. London]’, a place that had been a bedrock of Pitt’s supporters.Footnote 73 While George III became aligned with Henry V on stage, Pitt’s fortunes seemed to underline an earlier satirical comparison offered by Arthur Murphy in The Test: that Pitt – parodied within the pamphlet’s dramatic farce as ‘William IV’ – is akin to Shakespeare’s Richard III. While Murphy’s parody of Pitt admits in soliloquy that he intends to ‘seize the helm’, he imitates Richard III and feigns reluctance to power and money, as Shakespeare’s duplicitous monarch does in Act 3 Scene 7, before the Mayor and citizens of London.Footnote 74 Shakespeare provides a vehicle for activating topical political reflection in print and on stage, but the mobilization that would sustain public enthusiasm in London was one that celebrated national successes.

Figure 1.3 William Hogarth, ‘The Times, Plate 1’ (London, 1762).

Although he often attended the theatre, George III does not seem to have been interested in the wartime spectacle staged at Covent Garden. Indeed, the king interrupted the unbroken run of Henry V and The Coronation on 10 December for a performance of The Miser and Thomas and Sally, ‘By Command of their Majesties’.Footnote 75 Similarly, on 7 January 1762, a mostly unbroken run of The Coronation with one of Shakespeare’s histories was halted by Royal Command – this time for a performance of The Merry Wives of Windsor and The Knights.Footnote 76 One year earlier, on 23 December 1760, Charlotte Fermor had reported in a letter to her mother, the Countess of Pomfret, that George III ‘hardly ever bespoke any other than Shakespeare’s historical plays, all which they say he has ordered to be revived and takes great pleasure in’.Footnote 77 Command performances of, for example, Richard III and King John appeared, respectively, on 21 November and 23 December 1760. By late 1761, however, the king seems to have been less interested in attending the theatre to see these monarchical histories and their conquests. During this pivotal period in domestic and wartime politics, George did not attend any of Shakespeare’s histories. In Rich’s production, impersonators of the king and court staged a temporally malleable history that positioned the real monarch as its authorizer in absentia. What I hope to show through this extended example is that Covent Garden’s production of Henry V and The Coronation not only offers a monarchical and national fantasy about wartime military successes, it constructs a narrative of royal authorization that diverges from George III’s own policies, elides the building opposition to the war, and seems, in the midst of conflict, to commemorate its outcome and the position of Shakespeare as a central cultural figurehead within wartime memorialization. It is a local and London-centric display of wartime commemoration, and the conditions that facilitated this theatrical success were specific: Henry V was not, for example, performed even once at the Theatre Royal in Bath during the Seven Years’ War.Footnote 78 The production at Covent Garden involved production agents invested in elaborate spectacle, alongside a ready audience, and created a performance event that resonated with wider uses of Shakespeare as a cultural symbol for British conquest over France.

Nationalism, David Garrick, and Henry VIII

Garrick’s production of Henry VIII with ‘A Coronation, And the Ceremony of the Champion in Westminster-Hall’ was staged just eight days after George III’s coronation on 22 September (see Figure 1.4).Footnote 79 Some earlier productions of Shakespeare and Fletcher’s play had also advertised the inclusion of a coronation using similar phrasing. For example, on 21 September 1758, a performance at Drury Lane with Edward Berry in the title role included ‘an Exact Representation of the Coronation, And the Ceremony of the Champion in Westminster-Hall’.Footnote 80 In both cases, the advertised ‘Coronation’ was not strictly an afterpiece, but part of the play: it refers to Anne Boleyn’s coronation as Henry VIII’s queen within Act 4 Scene 1. What makes Garrick’s 1761 production significant is the fact that he sought to replicate the procession and ceremonies from George III’s coronation within this scene and, similar to Rich’s Henry V, he did not include an afterpiece following the main play, an omission that was atypical and establishes the theatrical event as a sustained royal spectacle that does not shift in tone through the inclusion of, for example, a comic afterpiece. The earlier production of Henry VIII in 1758 mentioned above included A Duke and No Duke as the afterpiece, while another production on 9 November 1758 added the farce Diversions of the Morning.Footnote 81 As the coronation within Henry VIII concentrates attention on Anne Boleyn, rather than the king, Garrick’s replica focused on Queen Charlotte’s position in the recent coronation. While Garrick’s production was not as successful as Rich’s and was harshly criticized by some audiences and reviewers, it represents another significant example of national, cultural, and royal commemoration at a growing crisis point within the ongoing conflict and seems to underline a connection, involving multiple temporalities, between Shakespeare and the staging of royal authority that is used to bolster an image of British cultural and political hegemony. However, Garrick’s production is also instructive because extant evidence reveals a range of agendas and responses that complicate a singular narrative of its wartime import and whether it can be seen to encourage audiences to reflect on the conflict or offer entertainment that distracts from it.

Figure 1.4 Playbill for Henry VIII, performed at Drury Lane on 30 September 1761.

An edition of Henry VIII, published in 1762 for a consortium of stationers (including the Tonson family and John Rivington), offers some indication of how the coronation in Garrick’s production was performed. This text is an acting edition that, as advertised on its title page, reflects how ‘it is Performed at the Theatre-Royal in Drury-Lane’ and the printed cast list corresponds with the opening performance on 30 September 1761.Footnote 82 In the coronation scene (Act 4 Scene 1 in the Folio and modern editions), all of Shakespeare and Fletcher’s dialogue is removed and replaced with a lengthy outline of a procession and a separate order for the ‘Champion’s Procession in the Hall’, both of which draw on contemporary accounts of George III and Queen’s Charlotte’s coronation.Footnote 83 It splices together the two locations associated with these events – Westminster Abbey for the coronation and Westminster Hall, where the coronation banquet and ceremony of the Champion took place. The latter was not a feature of Shakespeare and Fletcher’s play, and the printed playbook does not indicate how the ritual unfolded or include dialogue for the Champion’s challenge, offering a partial record of this contemporary interpolation in the play. The order of the coronation procession draws heavily on accounts of George and Charlotte’s procession to the Abbey. Its beginning, for example, exactly follows printed reports of the royal spectacle, led by the ‘King’s herb woman’ and ‘six Maids’, the ‘beadle of Westminster’, the ‘high constable of Westminster’ and a series of drummers and trumpeters.Footnote 84 Garrick’s procession also features the French dukes of Normandy and Aquitaine, which were a widely discussed feature of George III’s coronation. An article in the September issue of The London Magazine explores the tradition of prominently featuring these French dukes during every royal coronation, a notable inclusion because these titles were no longer current in Britain and therefore required noble ‘actors’ to take on these roles. For George and Charlotte’s coronation, they were played by Sir William Breton (Aquitaine) and Sir Thomas Robinson (Normandy).Footnote 85 Garrick’s inclusion of these French dukes within Anne’s coronation creates a multi-layered sequence of representations: theatre actors played English noblemen who were, in turn, standing in for defunct French titles that indicated England’s prior claims to parts of France.Footnote 86

What Garrick offered was a production of Henry VIII that featured, embedded within it, an abridged performance of an eighteenth-century spectacle that focused attention on the staging of royal power in a way that limited the potential for critical reflection. The coronation scene, with some omissions and substitutions, mostly replicated the ceremony for George III through to the appearance of the queen – Anne in the play and Queen Charlotte in the 1761 printed accounts – at which point the theatrical ceremony seems to have ended, offering a wordless procession that closely restages the first two-thirds of the king and queen’s coronation that took place just eight days previously.Footnote 87 Through this ‘updated’ staging, Garrick’s ‘Coronation’ omits the ongoing commentary provided in the 1623 Folio by two unnamed ‘Gentlemen’, which was printed immediately after the Folio’s short outline of the procession, but was clearly intended to be spoken during it. This commentary registers a degree of critical distance from Anne’s coronation, particularly when one of the gentlemen suggests that the nobles, who are like stars, are ‘sometimes falling ones’ (4.1.55–57). By removing this dialogue and embellishing the pageantry and length of the coronation, Garrick also removes this critical distance. There are no onstage observers to offer a critique of the signs and symbols of royal power. Within the context of the ongoing wars, this production seems to celebrate royal authority at a time when the waging of war was closely linked – symbolically, if not also in practice – with the person of the monarch.Footnote 88 However, unlike the production of Henry V at Covent Garden, which directly links George III with a military victory against the French, Henry VIII is not invested in wartime debate or representations. What makes it a significant production, especially for my purposes, is its staging of multiple temporalities that collectively deflect attention away from the play’s questioning of monarchical inviolability. It echoes – and directly incorporates – some of the euphoric accounts of George III and Charlotte’s coronation, and positions the play as a patriotic history that could encourage audiences to reflect optimistically on British political and cultural influence. While Rich’s Henry V has an inflammatory potential – it stages war and prompts audiences to applaud Britain’s military victories – Garrick’s Henry VIII takes audiences away from the direct business of war to the display of monarchical power and legitimation, especially through the ceremony of the Champion. This display could nevertheless have a similar effect and reinforce Britain’s war aims and its claims over new colonial possessions.

Contemporary publications linked the recent royal ceremonies of George and Charlotte’s marriage (on 8 September) and coronation (on 22 September) with images of British conquest, which, albeit indirectly, establishes a connection between the Drury Lane production and its wartime context. Also printed separately in St James’s Chronicle, a collection of verses on the ‘Royal Nuptials’ concludes with a poem ‘To the Queen’ that concentrates on ‘Britannia’s Praises’.Footnote 89 It encourages Charlotte to trace with ‘rapt Reflection Freedom’s favorite Race’, and refers specifically to Britain as a conquering, imperial nation that has ‘glow’d untam’d through many a martial Age’. It emphasizes the achievements of earlier monarchs (including Henry V and Edward III), scientists, and poets (including Spenser, Shakespeare, and Milton), as well as the glory and ‘Opulence of hoarded War’, when, from Britain’s ‘Ports a thousand Banners stream; | On every Coast her vengeful Lightenings Gleam’. The poem unambiguously applauds foreign conquest brought about by military successes, but also, as the poem presents it, through representatives of royal, artistic, and scientific merit. Queen Charlotte is part of this programme and spectacle of conquest:

Charlotte is presented as another of Britain’s new possessions – and this positioning of women as conquered objects shares a close parallel with Shakespeare’s dramatization of historical queens, including Anne Boleyn, as well as Katherine in Henry V. Garrick’s addition of a contemporarily focused coronation spectacle in Henry VIII furthers this effect. It breaks down the boundary between past and recent events, as the image of Anne/Charlotte is offered to theatre audiences for their approval and possession as a symbol of ‘Britannia’s Praises’.

While Garrick’s production aggrandizes royal authority in a way that could, in the context of the ongoing war, boost audience morale, patriotic sentiment, and support for recent victories, reception agents do not always respond in line with the aims of production agents, and Garrick’s spectacle was not greeted with much enthusiasm. In his Memoirs of the Life of Garrick (1780), Thomas Davies ridicules Drury Lane’s replica of the coronation and suggests it had limited impact:

[A] new and unexpected sight surprised the audience, of a real bonfire, and the populace huzzaing and drinking porter to the health of Queen Anne Bullen. The stage in the mean time, amidst the parading of dukes, duchesses, archbishops, peeresses, heralds &c. was covered with a thick fog from the smoke of the fire, which served to hide the tawdry dresses of the processionalists. During this idle piece of mockery, the actors being exposed to the suffocations of smoke, and the raw air from the open street, were seized with colds, rheumatisms, and swelled faces. At length the indignation of the audience delivered the comedians from this wretched badge of nightly slavery, which gained nothing to the managers but disgrace and empty benches.Footnote 91

The production did not satisfy audiences as Rich’s lavish and expensive spectacle at Covent Garden later would. Garrick seems to have reused old costumes, while complications arising from the use of a real bonfire caused the actors to choke and turned the ceremony, according to Davies, into an ‘idle piece of mockery’. Despite the evidence of its design, some reception agents felt that it had limited power as a production that commemorated the royal coronation or one that could reflect optimistically on the war and Britain’s new ‘possessions’. Garrick nevertheless persevered with his version of the coronation. After an initial seven-night run with Henry VIII, the ‘wretched badge of nightly slavery’ was repeated at the end of different plays for a total of twenty-six nights between 30 September and 4 December.Footnote 92 For these later performances, Garrick’s Coronation was removed from its position within Henry VIII and re-presented as a self-standing spectacle – ‘sometimes at the end of a play, and at other times after a farce’ – that focuses even more attention on the contemporaneity of the display.Footnote 93 On 16 October, for example, it was performed as an afterpiece following Jonson’s The Alchemist.

While Garrick’s agency is central in the development of his Coronation, it does not necessarily follow that my account of the spectacle’s wartime significance reflects his own political views. Garrick seems to be most invested in this production as a commercial enterprise and as a way of courting the new king’s favour, which could benefit Drury Lane’s royal patent. Garrick corresponded regularly with George’s favourite, the Earl of Bute, asking for his ‘Sentiments upon my Friend Mr Home’s Plays’ and for favours and promotions for friends, including Thomas Gataker.Footnote 94 His letters display an interest in the progress of the war in terms of how it might affect theatrical operations and the staging of specific plays. In a letter to James Harris, later first Earl of Malmesbury, about the performance of his pastoral, The Spring, Garrick reflects that if ‘a peace is settled by the middle of October (at which time I have your leave to perform it), it will be a most lucky circumstance in our favour’.Footnote 95 Garrick seems broadly to applaud British cultural and political achievements, which is suggested theatrically through, for example, his local textual emendations to Cymbeline, first performed on 28 November 1761 and running for ten almost-consecutive nights.Footnote 96 Garrick’s adaptation cuts Lucius’s comment, in Act 3 Scene 1, about the Romans as conquerors of Britain and, in the conclusion, removes all references to Britons paying tribute.Footnote 97 As Valerie Wayne argues, these changes ‘minimize the influence of the Romans on British history’ and simplify the ‘conflicting allegiances that Shakespeare sets up’, which seems to bolster support for the British war effort.Footnote 98

Within a conflict that was presented, in shorthand, as a war against France, Garrick refrains, however, from obvious anti-French sentiment. While critical accounts of Garrick’s pantomime Harlequin’s Invasion, first performed in the aftermath of the 1759 victories, stress its role as anti-French propaganda, Jonathan Crimmins offers an insightful revision of this view.Footnote 99 Rather than concentrating solely on the final scene when Mercury descends to banish the French Harlequin and the effigy of Shakespeare rises to a rendition of Garrick’s ‘Heart of Oak’, Crimmins shows how the antics of the English throughout the pantomime are hardly commendable nor do they inspire national pride. Garrick’s design may be more usefully linked to practices and problems of reconciliation, at the same time as playfully engaging with the criticism he received for hiring a French troupe of dancers in November 1755 for Les Fêtes Chinoises, a ballet by Jean-Georges Noverre, which led to riots at Drury Lane. Reflective perhaps of an Enlightenment cosmopolitanism, Garrick was himself appreciative of French culture for which he was cajoled in publications such as The Visitation; or An Interview Between the Ghost of Shakespear and D-v-d G-rr--k, Esq (1755). In this poem, Shakespeare’s ghost complains to Garrick about the prevalence of ‘foreign Foppery’ at Drury Lane, performed at the expense of weighty British plays about ‘bloody Crowns’ and ‘Nobles [striving] with noble Deeds’, and recommends that Garrick stage Henry V, a play that he ‘need not fear […] will miscarry’.Footnote 100 Garrick did not, however, stage Henry V at any point during the war and, in Henry VIII, deploys spectacle in a way that is not antagonistic towards the French. Nevertheless, the context of the Seven Years’ War and the reification of Charlotte, in contemporary publications, as a new British possession that inscribes a competitive and aggressive relationship with other nations serve to enhance the production’s interpretative ‘currency’ as an albeit critically unsuccessful commemoration of British dominance on a global stage.

During this conflict, Shakespeare on stage broadly supports British war aims and imperialism, sometimes in ways that feature France as a political or cultural combatant – in, for example, Henry V ’s military ‘Conquest over the French’ or Harlequin’s Invasion, with its symbolic cultural combat between Shakespeare and the French Harlequin. It was, as Colley suggests, a ‘dramatically successful’ war, but public opinion was not uniform, nor was there an unquenchable desire to see jingoistic productions of Shakespeare’s plays or topical wartime drama on stage.Footnote 101 Even during the height of Britain’s victories, there was still uncertainty about the merits of the conflict – although this disquiet tends to be drowned out by more numerous celebratory accounts.Footnote 102 Quoted earlier, Johnson distrusted the war’s justification, seeing it as a shameful competition over power and land. Similarly, Oliver Goldsmith’s ‘On Public Rejoicings for Victory’, published in The Busy Body on 20 October 1759, features a spectating narrator who ironically embraces the war’s victories and claims that its extreme costs can be overlooked when focusing on distracting spectacles: ‘I cannot behold the universal joy of my countrymen without a secret exultation, and am induced to forget the ravages of war and human calamity, in national satisfaction.’Footnote 103 The stage and Shakespeare were, however, mostly used for patriotic purposes that were not explicitly critical of the ongoing war. But they were not always successful or impactful as wartime commentary: Garrick’s contemporarily focused royal spectacle in Henry VIII was the target of some harsh criticism. While Harlequin’s Invasion was performed frequently at Drury Lane, which suggests audience demand, it did not appeal to all. On 13 October 1760, Charles Brietzcke attended Richard III and Harlequin’s Invasion with John Larpent, and complained that the performance ‘was not over till 11’, concluding that he ‘shan’t be in a Hurry to go again till there is better Co[mpan]y in the Boxes’, which suggests the theatrical event, for this reception agent, was rather tiresome and of little topical urgency.Footnote 104

Similarly, while William Hawkins’s adaptation of Cymbeline, first performed at Covent Garden on 15 February 1759, offered a substantial rewriting of Shakespeare’s play in the service of an aggrandizing narrative of British wartime success, it had limited impact. Hawkins, a professor of poetry at Oxford, sought to have his ‘truly British’ drama ‘wear a modern dress’ through numerous allusions to the Seven Years’ War that fortified its contemporary importance, as outlined in the Prologue:

Throughout, Hawkins uses Shakespeare’s play to valorize the pursuit of military glory and conquest, making textual additions that celebrate wartime resistance and changing some of the events within the play. For example, Hawkins, going a step further than Garrick would in 1761, reverses the issue of tribute at the play’s conclusion. Rather than Britain agreeing to pay tribute to Rome, the British victory is so complete that Augustus is compelled to pay ransom for the Roman prisoners. While the production is in keeping with, as Dobson describes, ‘popular views of [Britain’s] destiny’ witnessed in, for example, the ‘paper war’ that was taking place in print, Hawkins’s adaptation does not seem to have been successful on stage. It was performed seven times between February and April 1759, meeting with, as Hawkins claims in his print dedication to the Countess of Lichfield, ‘unprecedented difficulties and discouragements’.Footnote 106 New topical drama was not always successful either. A pantomime called The Siege of Quebec; Or, Harlequin Engineer dramatized the defeat of the French and the conquest of Quebec in 1759, attempting to capitalize on the popularity of Harlequin as a symbol for French culture and featuring Britannia as ‘the Genius of England’. Underlining its contemporaneity as a wartime spectacle, it featured an ‘Emblematical Representation of General Wolfe’s Monument’ to commemorate the death in battle of James Wolfe, who led Britain’s forces in Quebec and was the subject of many paintings and prints that presented his death as heroic self-sacrifice.Footnote 107 This pantomime was only performed once, however, on 14 May 1760 at Covent Garden and was never printed. What this swift survey aims to suggest, in other words, is that while the stage and Shakespeare are conspicuously used to support British wartime efforts and align a triumphant narrative of conquest with royal authority, such aims were not systematically pursued by all production agents, nor were they consistently successful with reception agents.

Conclusions

During the Seven Years’ War, Shakespeare – on stage and in print – was a key figure through whom audiences could, as Goldsmith’s narrator satirically applauds, be ‘induced to forget the ravages of war’. The royal spectacles of Garrick’s Henry VIII and Rich’s Henry V could induce this process of forgetting. In Rich’s production, the conflation of George III and Henry V seems to have been exceptionally successful on the evidence of reviews and an extended performance run, prompting the wartime satisfaction that Goldsmith’s narrator ironically refers to above. Those responsible for these productions were theatrical agents – Rich, Garrick, and their actors and designers – and not all of them would have held the same agendas; indeed, both managers likely prioritized commercial and staging factors in their productions above direct political commentary and persuasion. The construction of wartime narratives and the commemoration of recent military victories through their monarchical authorizers may not have been a core aim for those involved. Instead, it emerges as a consequence of interlocking conditions of production: the desire of both Garrick and Rich to capitalize on the recent coronation; Rich’s penchant for extravagant theatrical spectacles and expertise in pantomime design; the audience’s appetite for dramatizations of military victories; and the success of William Smith in the character of Henry V – to name a few contributing factors. Francis Gentleman praises the ‘commendable national vanity which makes Britons fond of seeing Britons distinguished on the theatre of life’, and this perspective seems to have been widespread, even witnessed in texts by writers who questioned the merits of the ongoing conflict.Footnote 108 For example, while Samuel Johnson disapproves of the war’s causes and justification, he nevertheless sympathizes with the British war effort above the French, and considers how Britain may prove successful against those who ‘invade our colonies’, a presumption of ownership that complicates his earlier misgivings about imperial usurpation.Footnote 109 Shakespeare is used to elide the complexities of conflict and to step back uncritically to embrace comforting notions of Britain’s cultural and political superiority.

Indeed, the Seven Years’ War had, as De Bruyn describes, ‘a catalytic effect’ on the transformation of Shakespeare into ‘a fitting emblem of the country’s national character and imperial ambition’.Footnote 110 Other commemorative projects that spliced together (with varying transparency) Shakespeare and wartime ‘achievements’ were launched in the conflict’s aftermath. Garrick’s 1769 Stratford Jubilee, which famously did not stage a single play of Shakespeare’s or quote from them directly, was primarily a ‘nationalizing’, patriotic festival planned in the years immediately following the war’s conclusion that, as Dobson describes, celebrated Shakespeare as a British icon and required ‘the performed exclusion of foreigners from his festival’.Footnote 111 Bell’s editions of Shakespeare and publications on British theatre were also imperial projects that, as one review in The Times remarked, secured the extension of Britain’s fame through ‘the wide circulation of the British Classics’.Footnote 112 These efforts were underscored further by Gentleman’s commentary in Bell’s editions and his own Dramatic Censor (also published by Bell) that pointedly extoll the nation’s wartime achievements. Similarly, Edward Capell, who dedicates his edition of Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies (1768) to Augustus Fitzroy, third Duke of Grafton (Prime Minister between 1768 and 1770), presents it as ‘an object of national concern’ because the plays ‘are a part of the kingdom’s riches’: the ‘worth and value of which sinks or raises her in the opinion of foreign nations, and she takes her rank among them according to the esteem which these are held in’.Footnote 113 An interest in connecting Shakespeare to a project of imperial expansion is promoted in Maurice Morgann’s Essay on the Dramatic Character of Sir John Falstaff (1777), which presents Shakespeare as a conqueror of the Americas and maps his influence directly on to geopolitical features:

When the hand of time shall have brushed off his present Editors and Commentators, and when the very name of Voltaire, and even the memory of the language in which he has written, shall be no more, the Apalachian mountains, the banks of the Ohio, and the plains of Sciola shall resound with the accents of this Barbarian: In his native tongue he shall roll the genuine passions of nature; nor shall the griefs of Lear be alleviated, or the charms and wit of Rosalind be abated by time. There is indeed nothing perishable about him.Footnote 114

Morgann’s positioning of Shakespeare as a natural and immortal genius is emphatically linked to Britain’s victory over France and the acquisition of colonies, while Voltaire is France’s equivalent cultural-political representative. Morgann prophesizes that the memory of Voltaire (and, by extension, French power) will be forgotten in the Americas, which will instead resound with the words of Shakespeare and the authority of the British. The events and aftermath of the Seven Years’ War therefore see Shakespeare mobilized as a cultural and political representative – one that would have a lasting influence not only in Britain, but also in America and France, and during the two revolutionary wars that dominated the rest of the eighteenth century.