Alone, in the saffron garb of the Buddhist bhikshu, he started on his mighty journey, even though the Chinese Emperor had refused his permission. He crossed the Gobi desert, barely surviving the ordeal, and reached the kingdom of Turfan, that stood on the very edge of this desert. A strange little oasis of culture was this desert kingdom. It is a dead place now where archaeologists and antiquarians dig for old remains.

The ‘discovery’ of Dunhuang and the suddenness with which it leapt into world fame constitute one of the romances of twentieth-century exploration and archaeology.

In 1955, the Punjabi scholar and Hindu nationalist Raghu Vira (1902–1963) found himself in a run-down Polish car jolting violently through the arid landscape of China’s northwestern Gansu Province. Following in the footsteps of his great hero, the Austro-Hungarian archaeologist Aurel Stein, Vira was on his way to visit the Dunhuang caves. Its famous Buddhist frescos promised to offer tantalizing glimpses of ancient India’s artistic legacies thousands of miles northeast of New Delhi.Footnote 3

Inspired by the work of the Greater India Society (GIS), Vira had founded the International Academy of Indian Culture in Lahore which aimed to compile a comparative, Pan-Asian survey of ancient Indian literature.Footnote 4 Vira’s visit to Dunhuang was part of a three-month study tour and quest to gather documents pertaining to the ancient Sino-Indian cultural intercourse.Footnote 5 At a later point, Vira found himself bonding with the first premier of the People’s Republic of China, Zhou Enlai, over a topic that appealed to both Indian and Chinese intellectuals at the time: the travels and travails of the seventh-century Buddhist monk Xuanzang (c.602–664 ce) as recorded in the travelogue Great Tang Records on the Western Nations. In his quest to visit the sites associated with Buddha’s life and teaching, Xuanzang had completed an epic seventeen-year overland journey that included stopovers in the Silk Road hubs of Turfan, Kucha and Bamiyan, and a longer sojourn at the famous “international” monastery of Nalanda.Footnote 6

This shared interest in ancient Sino-Indian interactions reflected a new historical consciousness. In 1924, Rabindranath Tagore’s China lecture tour had fueled wider public interest in the Buddhist connectivities linking the Indic and Sinic spheres, and inspired Asianist agendas that called for cultural cooperation and a renewal of ancient bonds.Footnote 7 One such initiative was the founding of the first department of Chinese Studies on Indian soil at Tagore’s international university of Visva-Bharati. On the occasion of the inauguration of “Cheena Bhavana,” the young Indira Gandhi read out a message from her father, Jawaharlal Nehru, who hailed the institute as a new chapter of Sino-Indian collaboration and a fitting tribute to the “memories of the long past that it invokes.”Footnote 8 Tagore had been in touch with leading Chinese politicians ever since his China tour and kept up a correspondence with high-profile figures such as Chiang Kai-shek, the head of the National Government of the Chinese Republic. Inspired by Tagore’s contagious idealism, Kai-shek visited Visva-Bharati in February 1942, a year after the poet’s death. In a Welcome Address, Rathindranath Tagore recalled how his father had tried “to bring back to life the ancient cultural amity” and the “unity between our two ancient peoples.”Footnote 9

Rathindranath’s invocation of Sino-Indian “ancient cultural amity” alluded to a specific chapter of the past: the diffusion of Buddhism and Indic art forms via the Silk Roads of Central Asia to the Far East during the first millennium ce. Even if Chinese pilgrims such as Xuanzang had come to India, Asia’s Buddhist ecumene had been energized, as Tagore put it in a letter to Nehru, by “the overflow of [India’s] glorious epoch of culture.”Footnote 10 But what had triggered this geographically expansive vision of India’s past?

In the first decades of the twentieth century, a series of German, French and Raj-sponsored archaeological expeditions had ventured into Central Asia and their spectacular finds opened new historical vistas on the connected histories of the Silk Roads. The exploits of Aurel Stein, Paul Pelliot, Albert von Le Coq and others brought to light forgotten polities, abandoned cities and unknown scripts, and yielded a vast collection of manuscripts and artifacts. It turned out that in “Chinese Turkestan” – at the beginning of the twentieth century a remote and inaccessible region where Chinese sovereignty was only loosely enforced – Sinic, Indic, Greco-Roman, Persian, Tibetan and Turkic influences had fused, and in the process energized one of the most remarkable experiments in cross-cultural artistic borrowing that the ancient world had ever witnessed. Archaeological evidence hinted at the presence of at least three “world religions” – Buddhism, Christianity and Islam – as well as a bewildering variety of other cults ranging from Zoroastrianism and Manicheism to Hindu practices.

The notion of Chinese Turkestan as a cultural and religious crossroads undoubtedly added to its romantic and scholarly appeal, and the evocative image of the archaeological hero stumbling upon lost cities, priceless artifacts and treasure-troves of religious manuscripts, has had a lasting imprint on the Western imagination of the region.Footnote 11 However, in interwar British India, the appeal of the Silk Roads was decoupled from such Eurocentric connotations. Indian intellectuals focused instead on the Buddhist connectivities that had come to light and reframed the Far Eastern odyssey of Buddhist doctrine and art as a glorious saga of Indian civilizational diffusion. In the 1920s and 1930s, this Indocentric prism inspired an alternative framing of the region which today roughly overlaps with the Chinese autonomous region of Xinjiang. Central to this framing was the notion of “Serindia,” a term popularized by Aurel Stein, which blends India with the Latin designation for China (Seres – “the land of silk”).

This chapter foregrounds the interwar European and Indian “discovery” of the Buddhist legacies of the Silk Roads. It charts how the archaeological quest for the ancient past in Chinese Turkestan triggered a reconfiguration of the notion of “Indic civilization,” both in spatial and historiographical terms. Although there is an excellent body of scholarship on “the discovery of ancient India” in the colonial era, most studies have focused exclusively on the role of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) and the legacies of the Raj, and correspondingly limited their purview to the Indian subcontinent.Footnote 12 Conversely, the rich body of work on the “archaeological pioneers” of the Silk Roads remains disconnected from broader questions about the reception and impact of their finds among intellectual circles in British India. However, as this chapter shows, the archaeological expeditions in Central Asia changed the narration of India’s past for good. Furthermore, the recovery of the Buddhist past in Central Asia, and the art historical interpretation of the finds, were closely linked to debates on the cultural heritage of Gandhara and the importance of the “Greek factor” in Indic/Asiatic art, a question which preoccupied both European and Indian scholars.

Since the quest for Serindia is best understood in light of broader developments in the discursive sphere of Orientalism and archaeological practice, this chapter offers first a brief analysis of the major paradigm shifts that brought ancient India into the orbit of world history. After sketching the wider context and imperatives that triggered the advent of Buddhist archaeology in South Asia and the Gandhara region, the story shifts to Chinese Turkestan. As the chapter unfolds, we see how the Far Eastern quest for the spatial horizons of Greco-Roman aesthetics, spearheaded by European archaeologists and art historians, gradually gave way to an Indocentric approach: “Indic” replaced “Greek” as the superior classicism and civilizing impulse that had temporarily uplifted local culture and left its ennobling aesthetic imprint in Central Asia and across the wider Asian sphere. The legacies of Serindia were, in turn, mobilized by GIS scholars and Indian intellectuals to bolster visions of Greater India.

Orientalist Trailblazers: Looking for Greece and the Buddha

The Sanskrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than Greek, more copious than Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of the verbs and the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident.

Thus spoke Sir William Jones (1746–1794), the versatile Anglo-Welsh barrister who combined a lively historical imagination with a penchant for Oriental languages. Although few of his historical speculations, including the conjecture which identified the historical Buddha as hailing from Ethiopia and Stonehenge as “one of the temples of Boodh,” have withstood the test of time, Jones pioneered an approach to the study of Indian history and civilization that was remarkably open-minded, boldly ambitious and bounded “only by the geographical limits of Asia.”Footnote 14

This bold vision and ambitious research agenda lost its momentum once its precocious driving force died prematurely, and the logic of disciplinary specialization, in tandem with the advance of knowledge, made scholars increasingly puzzle within narrower frames. Yet the “Jonesean moment” did not pass without some groundbreaking insights that would inform the research agenda for several generations of Orientalists to come. Apart from a broader Indocentric approach to Asia’s past, Jones brought to light the Indo-European language family and established a chronology of ancient Indian history with the help of Greek sources. Jones’ early musings on the shared roots of Sanskrit, Greek, Latin and the Germanic languages anticipated the birth of comparative linguistics in the early nineteenth century and “proposed new and unexpected relations among nations, and in so doing revolutionized the deep history of Europe and of India, and indeed of the world.”Footnote 15 The nineteenth-century quest for the mother of all Indo-European languages gave rise to all sorts of theories and speculations about the homeland of the original “Aryans” and became, as the century progressed, increasingly linked to racial discourses. This later racialization of the Aryan trope and the ugly politics for which it was employed in the twentieth century, is a far cry from what the discovery of the Indo-European language family initially proposed, namely that the history of India was connected to that of Europe and Persia. Comparative linguistics suggested that at some point in a dim ancient past, “Europeans” and “Indians” may well have been living side by side in an as yet unidentified Indo-European homeland which had, not unlike the legendary dispersal of mankind following the “confusion of tongues” at Babel, given rise to different branches of civilization. Thus, unexpectedly, the colonial presence of the British in Calcutta could be regarded as a “family reunion” of sorts, a metaphor that chimed with the Mosaic ethnology that informed early Orientalist research and budding Romantic sentiments subscribing to the Ur-unity of mankind. The Aryan kinship narrative, however, sat uneasily with the quotidian reality of East India Company rule in Bengal and many local Brahmins were, as Tony Ballantyne has put it, “not edified by the prospect of being cousins with ‘beef-eating, whiskey-drinking Englishmen’.”Footnote 16

If “claiming kin” was the first important Jonesean intervention, the second insight was concerned with synchronology and attempted to locate events of Indian history within a familiar European chronology informed by the Christian calendar. With the help of Greek sources, Jones was able to establish that the Mauryan emperor Chandragupta (Greek: Sandracottus) was a contemporary of Alexander the Great. He, thus, not only opened a new window on the dynastic past of the subcontinent, but also integrated India for the first time into a world-historical narrative by bringing the subcontinent within the orbit of events familiar to students of European history.Footnote 17

When we zoom out in order to gain a broader perspective on trends within the burgeoning field of Indology, we see that the quest for the origin of the Indo-European languages and an obsession with the ancient Sanskrit texts of the Vedas, inaugurated by “East India Company gentleman scholars” such as William Jones, Charles Wilkins (1749–1836), Henry Thomas Colebrooke (1765–1837) and the pioneering French polymath Anquetil-Duperron (1731–1805), found its climax in a generation of predominantly German philologists such as Franz Bopp (1791–1867), Albrecht Weber (1825–1901) and Friedrich Max Müller (1823–1900) in the second half of the nineteenth century.Footnote 18 The craze for Sanskrit and Indomania within European intellectual circles during what Raymond Schwab described as Europe’s “Oriental Renaissance” was, however, primarily a text-based encounter with India.Footnote 19 The infatuation with literary gems such as Kalidasa’s “baroque” play Shakuntala, the lyrical poem Meghaduta (“Cloud Messenger”) and eminent sacred texts such as the Rig Veda, Bhagavad Gita and Valmiki’s Ramayana had little bearing on the realities of modern India.Footnote 20 In fact, of the previously alluded-to generation of leading German Sanskritists neither Bopp nor Müller nor Weber ever set foot on Indian soil. They were typically working on their dictionaries, grammars and literary translations from their desks in Berlin, Oxford or Paris, and even though European scholarly and cultural elites engaged enthusiastically with the beautifully crafted pieces of prose, poem and liturgy that reached them from far-away “exotic” India, the texts themselves shed very little light on the history of the subcontinent and its people.

While comparative linguistics was still going strong, there was another trend that departed from the strictly text-based and ahistorical musings of the leading philologists. Instead, it relied on field expeditions and all sorts of uncoordinated amateur-archaeological initiatives that, bit by bit, revealed the existence of forgotten polities as well as a major religion that had once thrived throughout the Indian subcontinent: Buddhism. More interested in reconstructing South Asia’s past than extolling the subtleties of Vedic mantras and speculating about biblical analogies, British officers with a predilection for antiques such Colin Mackenzie (1754–1821) and Charles Masson (1800–1853) were soon followed by individuals operating with a more systematic approach. Alexander Cunningham (1814–1893), who is often invoked as the founding father of Indian archaeology, used in his quest for “hard facts” the travel accounts of Chinese pilgrims such as Faxian (c.377–422 ce) and Xuanzang (c.602–664 ce) and thus identified many ancient sites, from the ancient Buddhist university of Nalanda and the stupas of Bharhut, Kushinagar and Sanchi to places associated with Siddhartha Gautama’s life at Sarnath and Bodh Gaya. In this piecemeal fashion, a wholly forgotten Buddhist sacred geography was reconstructed. Although Cunningham is often positioned as the figure in whose work we can witness “the shift from philology to archaeology as the new authenticating ground for Indian history,” it is important to bear in mind that the sort of tope-riffling, amateur-archaeological approach he pioneered could only proceed because he relied on the work of French Sinologists such as Jean-Pierre Abel-Rémusat, translator of Faxian’s account (Foe Koue Ki), and Stanislas Julien, whose multiple volume Voyages des Pèlerins Bouddhistes appeared in the 1850s.Footnote 21

At the same time, Cunningham was very explicit about the benefit of archaeology as opposed to the philologists’ inclination to focus on India’s literary legacy. As he stated with characteristic bluntness, “the discovery and publication of all the existing remains of architecture and sculpture, with coins and inscriptions, would throw more light on the ancient history of India … than the printing of all the rubbish contained in the 18 Puranas.”Footnote 22 Such sentiments were reflective of a deep general distrust among European observers of Indian accounts in which history, myth and legend seemed hopelessly entangled. An echo of Cunningham can still be discerned in prominent historical works published during the first decades of the twentieth century. According to the architectural historian James Fergusson, for example, “in such a country as India, the chisels of her sculptors are, so far as I can judge, immeasurably more to be trusted than the pens of her authors.”Footnote 23 The French Indologist Alfred Foucher struck a similar chord when praising the merits of sculptural evidence over textual sources: “Stones,” he asserted, “are by no means loquacious” yet “they atone for their silence by the unalterableness of a testimony which could not be suspected of rifacimento or interpolation.”Footnote 24

It is well documented how the epigraphic, sculptural and numismatic evidence brought to light by Cunningham and others enabled scholars such as James Prinsep (1799–1840) to decipher the ancient Kharoshti and Brahmi scripts and unlock the history of a powerful dynasty, the Mauryas, and its most prominent ruler, Asoka, who after a dramatic conversion had become one of Buddhism’s foremost patrons.Footnote 25 But archaeological material never speaks for itself and the British quest for India’s ancient past was structured by a highly selective gaze. The pioneer-archaeologists that set out across the subcontinent to follow in the footsteps of ancient Chinese pilgrims or with fragments of Megasthenes’ famed Indika in their travel bag, had a very clear set of priorities and a concomitant series of blinders.Footnote 26 Above all, there was a strong Buddhist bias that guided most archaeological activity.Footnote 27 Whereas the Sanskrit past was dismissed as fanciful and mythical, the more “reliable” Chinese, Greek and Roman sources proved to yield direct results in terms of findings. All one had to do, as Cunningham had shown, was find a good translation, follow the ancient route and dig wherever the scenery hinted at the presence of an old vihara, stupa or city as described in one of the old travel narratives. This Buddhist bias ensured that the archaeological activity in British India was, until Lord Curzon launched a wider subcontinental effort with the Ancient Monument Preservation Act (1904) and created the position of Director General for the Archaeological Survey of the British Raj (1902), predominantly focused on sites associated with the life of the Buddha in Northern India.Footnote 28 The blinders that came with these Buddhist lenses meant that prehistorical, Islamic or Hindu sites received much less attention and remains that yielded evidence of a plural religious history were often stripped of such “later superstitions” and reclaimed for Buddhism.Footnote 29

Beyond the Raj’s northwestern frontier, the search for antiquities was initially inspired by a remarkably tenacious obsession with the legacies, routes and exploits of the Macedonian conqueror Alexander the Great. It was not until the first decades of the nineteenth century, and especially following the East India Company’s conquest of the Punjab in 1849 at the expense of the Sikh empire, that British agents such as John Malcolm, Mountstuart Elphinstone, Charles Metcalfe, Henry Pottinger, William Moorcroft, Alexander Burnes and Charles Masson started to make extensive forays in this region and beyond. In the context of the “Great Game” or “Tournament of Shadows” many of these figures traveled disguised as natives via the northwest passes into Central Asia and Afghanistan to explore, survey, report and win the trust of local rulers and princelings.Footnote 30 Most of these colorful characters made frequent references to Alexander the Great, developed an antiquarian zest for Indo-Greek coinage, tried to locate ancient Greek “colonies” or the elusive Kafiristan, and traced evidence of Alexander’s transient presence in the barren deserts and mountain regions through which he was believed to have led his army into battle against the Indian monarch Porus.Footnote 31 Many of their discoveries and insights were communicated to the Asiatic Society of Bengal in Calcutta, where scholars like Prinsep and H. H. Wilson awaited their reports.Footnote 32

It was not just the romance of Alexander and his heroic exploits that put a spell on many a British officer; the military urge that drove Alexander to India signified a moment in world history in which “Europe” and “India” met for the first time. The image of a Greek conqueror making his presence felt in the subcontinent did, in fact, invite all sorts of analogies with the British Empire.Footnote 33 Thus, Alexander was not just an ancient hero but the connective tissue linking ancient India to the Classical World, and a precursor and colonial model that could be studied and emulated. Above all, Alexander embodied the civilizing impulse emanating from the West.

Following in the footsteps of Alexander the Great, British agents such as Alexander Burnes and Charles Masson were predisposed to find Greek antiquities.Footnote 34 When the region once occupied by ancient Bactria became accessible, James Prinsep, staying put in Bengal as Assay Master of the Calcutta mint, anticipated “a multitude of Grecian antiquities gradually to be developed.”Footnote 35 All the same, it soon became clear that not all excavated antiquities pointed towards the West; there was increasing evidence of an altogether different civilizational and artistic impulse that had its roots in the subcontinent, namely Buddhism. When early nineteenth-century explorers such as Mountstuart Elphinstone and Jean-Baptiste Ventura came across the ruins of the Manikyala stupa, built during the reign of the Kushan emperor Kanishka and located today in the environs of Islamabad, there was much confusion with respect to its function and its builders. In a note submitted to the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal (1833), Burnes dithered between the old assumption that “in these ‘topes’ we have the tombs of a race of princes who once reigned in Upper India” and a new conjecture which stated that “they may, however, be Boodhist buildings.”Footnote 36

In the course of the nineteenth century, it became increasingly clear that the latter assertion was the correct one. Burnes’ observations were made in a period which saw the advent of Buddhist studies in Europe.Footnote 37 Although the existence of Buddhism as a Pan-Asian religion of Indian origin had been anticipated in the conjectures of Enlightenment scholars such as Nicolas Fréret (1688–1749) and Joseph de Guignes (1721–1800), it was only with the publication of Eugène Burnouf’s Introduction à l’histoire du Buddhisme indien (1844) that the web of early speculations, misinterpretations and hypotheses was brushed aside by a work that was solely based on original Sanskrit and Pali sources.Footnote 38 A major impulse for reconstructing the history of textual Buddhism came in the form of a bundle of Sanskrit documents sent to the Société Asiatique by the British Resident at the Court of Nepal, Brian Houghton Hodgson (1800–1894). By distributing Sanskrit texts to different research bodies in Calcutta, London, Oxford and Paris, Hodgson played a pivotal role in launching the scholarly study, translation and interpretation of key doctrinal texts that ultimately enabled Burnouf to sketch, for the first time, a comprehensive outline of Buddhism.Footnote 39 As Burnouf emphasized, a proper study of Buddhism, a religion no longer present in India where it had originated, could only proceed on the basis of Sanskrit texts from Nepal and Tibet and Pali texts from Ceylon.Footnote 40

The Hellenized Buddhas of Gandhara: An Art Historical Conundrum

Textual Buddhism became increasingly tied to a material reality in the wake of the archaeological recovery of stupas, viharas, coins, sculptures and wall-paintings from Ajanta to Sanchi. This process was epitomized in the statuary and artifacts that were, in piecemeal fashion and starting in the mid-nineteenth century, removed from sites associated with the ancient polity of Gandhara in northern Punjab. Gandhara had reached its apogee under the Kushan dynasty in the first centuries of the Christian era. The Kushans were nomadic pastoralists, a prominent branch of the Yuezhi tribe hailing from the Central Asian steppes, who had settled in ancient Bactria and the area around the Swat Valley, a region which today straddles the borderland of Pakistan and Afghanistan. Although Gandhara was primarily associated with the Buddhist creed, Hindu and Zoroastrian cults were also established, the latter dating back to days when the region was a satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire.Footnote 41

In the early aniconic phase of Buddhist art, lasting roughly until the first century ce and exemplified in the sculptural reliefs of the Sanchi and Amaravati stupas, the Buddha was not depicted, but instead symbolized by the Bodhi tree, an empty throne, the Dharma wheel, a footprint or a parasol. When the first Gandharan sculptures appeared from the rubble of Taxila and the Swat Valley, the classical features of the Buddha figures and Bodhisattvas were perceived as tangible evidence that the Greek impulse had transformed the practice of Buddhist worship from an aniconic tradition into a religion whose fundamental teachings, and the important moments of the founder’s life, could be expressed with the chisel in stone. Following preliminary digging by Cunningham in the 1860s, Taxila was systematically excavated by John Marshall during the first decades of the twentieth century. From Marshall’s report it is clear that the presence of Greek remains was the main inspiration for concentrating his time and resources on this site.Footnote 42

The critical reception of Gandhara’s sculptural oeuvre in art historical circles was ambivalent. The substantial hoards of sculptures and reliefs provided tangible proof that “Greek” aesthetics had left their mark much further East than surmised. But in terms of aesthetic merit, opinion was divided. Hellenism may have found a new lease of life beyond the home-turf of celebrated classical sculptors such as Phidias and Leochares, but it was considered a “decadent” and “second-rate” Greco-Roman style that could hardly be put on a par with the masterpieces of Athenian plastic art. Under the influence of the Winckelmannian paradigm that conceived of art history as a process in which organic growth, the attainment of stylistic purity and maturation was followed by decadence and degradation, European art historians were inclined to read the hybrid art of Gandhara as a story of decline, the last ripple of a Hellenistic wave that was long past its Classical Golden Age when it reached the Indus region in the wake of Alexander the Great’s military campaign. Such Greek lenses made them judge Gandharan art with the familiar classical yardstick by which standard it was seen as a decline from the masterpieces found in Athens, Magna Graecia or Rome. The Gandhara style was above all conceived as “a strange and quaint mixture”: could the hundreds of sculptures unearthed in the Taxila region be described as “Hellenized Buddhas” or were they rather “Indianized figures of Apollo”? Were these friezes and stone colossi “Asiatic coin[s] struck in European style” or was the inverse true?Footnote 43

Scholars evidently lacked an adequate art historical language that could capture the different stylistic impulses mingling in the Gandharan torsos and stucco heads. In an early attempt to come to terms with the ambiguous legacy of Gandhara, Gottlieb Wilhelm Leitner coined the label “Graeco-Buddhist” in 1870.Footnote 44 Leitner (1840–1899) was an Austro-Hungarian educational administrator with antiquarian tastes working in Lahore, who played a prominent role in bringing Gandharan sculpture to public attention. However, the Irish Indologist and art historian Vincent A. Smith asserted that the term “Romano-Buddhist” would be more appropriate as he considered Rome, and outposts of Roman culture such as Palmyra and Baalbek (Heliopolis), crucial mediators of Greek influence on the Gandhara style.Footnote 45 But when turning to the stylistic and iconographic details, Smith had a hard time disentangling “pure” Greco-Roman elements from those belonging to “Asiatic” aesthetic traditions.Footnote 46 Evidently, Gandhara was a liminal zone where different civilizational impulses mingled, petered out and dissolved into something altogether new. This newly discovered civilizational space was a novelty hard to capture with existing vocabulary, but the labels applied to the hybrid Gandharan art typically emphasized the Western classical element.

The emphasis on Greek influence resonated with a center–periphery model of art history in which the West had agency as the transmitter of art and the East featured as the passive recipient of such ennobling aesthetic impulses.Footnote 47 Art historical interpretation was, thus, far from an innocent intellectual exercise. It reflected the same spirit of benevolent superiority and pedagogical agenda that informed the colonial civilizing mission. The thesis that the Buddhist sculptural tradition was inconceivable without the creative spark of Hellenic genius was not just an art historical curiosity but buttressed Western theories about an Orient that needed the helping hand of an altruistic West. Albert Grünwedel’s pioneering study of Buddhist art, for example, rehearsed the common scholarly opinion at the turn of the twentieth century that “talent in sculptural art exists only in a limited degree among the Indian Aryans.”Footnote 48 According to the German scholar and archaeologist Albert von Le Coq, the Greek way of representing a deity in sculpture was a revelation for “Indian artists [who] lacked either ability or courage to venture upon a graphical representation of the All Perfect.”Footnote 49 It was therefore only natural for one of the foremost scholars specialized in the art of Gandhara, Alfred Foucher, to see the “hand of an artist from some Greek studio” or the “industrious fingers of some Graeculus of more or less mixed descent” at work.Footnote 50 Evoking the aesthetics of Gandhara in front of a Parisian audience, Foucher emphasized the wonderful classical features of specimens found so far away from the Hellenic heartland:

Your European eyes have in this case no need of the help of any Indianist, in order to appreciate with full knowledge the orb of the nimbus, the waves of the hair, the straightness of the profile, the classical shape of the eyes, the sinuous bow of the mouth, the supple and hollow folds of the draperies. All these technical details, and still more perhaps the harmony of the whole, indicate in a[n] amaterial, palpable and striking manner the hand of an artist from some Greek studio.Footnote 51

Another redeeming feature of the Gandharan style, apart from its alleged Greek stylistic inspiration, was its “‘irréproachable tenue’ in dealing with the relations of the sexes.”Footnote 52 The prudish European art critics claimed that, in contrast to the “monstrous,” multi-limbed and deeply erotic creations of “Hindu art,” the sculpture of Gandhara did not share the common reproach of lasciviousness.Footnote 53 Classical restraint held the baser impulses in check and elevated the art of Gandhara, despite its failings, above the later sculptural traditions to which, or so the argument went, it gave rise. The classically trained eye noticed in later medieval Hindu sculpture a measure of ornamental excess which contrasted unfavorably with the lingering traces of grace, elegance and simplicity which, it was believed, only a Greek hand could have bestowed on the Gandhara sculptures.Footnote 54 For Foucher, the Buddha image was a Greek gift to Indian civilization which helped the latter overcome the somewhat clumsy way of representing the Buddha by aniconic symbols. Occasionally, he toned this picture of Hellenistic agency down by stressing that “the Indian mind has taken a part no less essential than Greek genius in the elaboration of the model of the Monk-God.”Footnote 55 In the broader scheme of things, Foucher considered himself “a friend of the East” and was thus happy to invoke the Buddhist image as an instance of unique collaboration between Orient and Occident.

Gandhara became celebrated as a site where Indian ideals found expression in a debased Hellenized form, and marked according to European critics such as Vincent A. Smith the epitome of the Indian sculptural tradition. The Gandharan stucco heads and torsos were, according to Smith, “the best specimens of the plastic art ever known to exist in India.”Footnote 56 The debate about the origin of Indian sculpture would become a thorny issue. Authors such as the Ceylonese art historian Ananda Coomaraswamy dismissed the Gandhara argument in favor of the more “indigenous” Mathura school of sculpture, thus shifting the site where the Indian sculptural tradition had allegedly been developed from the borderlands of the northwest to the plains of North-Central India and, by implication, beyond the stronghold of Indo-Greek culture.Footnote 57 Critics such as Coomaraswamy not only rallied against the notion that India had been initiated into the sculptural tradition by “Greek teachers,” thus denying Indian artists any creative agency, but also questioned the Western obsession with Gandhara and the comparative neglect of more authentically Indian aesthetic schools. Furthermore, the same European scholars that hailed Gandhara as the epitome of the Indian sculptural tradition would, in the same breath, relegate Gandhara, a far-flung offshoot of decadent Hellenistic and Roman aesthetic impulses long past their creative momentum, to the footnotes of classical art histories.

Yet the discovery of Gandhara as a hub for all sorts of aesthetic constellations did not only provide evidence of classical influence from the West. It also hinted at the spread of Indian civilization, in the form of Buddhism and concomitant art forms, into Central Asia and the Far East. What began as a quest for Alexander’s imprint in the region, in time opened up new historical vistas on the role of Indian civilization in the ancient world not just as a recipient of Western impulses and Greco-Roman inspiration but as a source of diffusion in its own right. Whereas comparative linguistics had brought Vedic India within the orbit of European civilization and Gandhara linked India to the classical civilizations of Greece and Rome, thus “opening the door to the West,” the study of Buddhism triggered all sorts of questions about the role of Indian civilization beyond the Bay of Bengal and the Himalayas. As we will see next, archaeologists and art historians such as Le Coq, Grünwedel, Foucher and Stein would embark on long and demanding missions to trace the influence of Gandhara into Afghanistan, Central Asia and even into the deserts of Chinese Turkestan.

Enter Chinese Turkestan: Desert Revelations from Serindia

If Gandhara placed the Indian art tradition for the first time, albeit on decidedly unfavorable terms, on a world-historical canvas, a number of momentous discoveries in Central Asia’s vast desert realm, “Chinese Turkestan,” dramatically expanded notions of a Greater Indian civilizational sphere. Chinese Turkestan, a contested term today, was the common European label for the area that roughly overlaps with the modern autonomous region of Xinjiang.Footnote 58 It referred specifically to the basin of the Tarim river which, fed by the melting snow of the encircling mountains, sustained the few oasis towns until it petered out in the salt-encrusted marches of the ancient seabed of Lop Nor. At the heart of the region lies the vast Taklamakan Desert. Aurel Stein, with a fine sense for what he believed to be the balance of historical agency in this realm, popularized the label Serindia for the region and referred to the culturally and aesthetically hybrid art objects found in Central Asia as Serindian art.Footnote 59

The dawn of the twentieth century witnessed an increasingly frantic activity with different archaeological teams being sent by their respective governments “on mission” to explore these vast desert expanses. They searched for ruins of ancient Silk Road polities whose art and religions bore, it turned out, strong Indian imprints. In the 1890s, the pioneering explorations by the Swede Sven Hedin in the region around Lake Lop Nor, the Tarim basin and Taklamakan Desert had revealed the existence of a “Hindu Pompeii” under the desert sands.Footnote 60 Stein, Austro-Hungarian by birth but employed by the British Raj, embarked on three groundbreaking missions covering sites such as Turfan, Khotan, Miran and Dunhuang (1900–1901/1906–1908/1913–1915). The Museum für Völkerkunde (Berlin) sent Albert Grünwedel and Georg Huth (1902–1903), Grünwedel and Albert von Le Coq (1905–1907) and Le Coq alone (1904–1905 and 1913–1914) to explore the northern Tarim basin with a focus on Turfan and Kucha.Footnote 61 The Japanese count and Buddhist monk Kozui Otani organized several missions to Central Asia between 1902 and 1912,Footnote 62 and Tsarist Russia, whose territories had expanded to include parts of Central Asia was represented by Dimitri Klementz (1898), the brothers Berezovskij (1905–1907), Pyotr Kozlov (1907–1909) and Sergei Oldenburg (1909–1910 and 1914–1915). Tsarist and Soviet interest in Buddhism had been piqued by the discovery of a Buddhist population of Mongol descent near Lake Baikal.Footnote 63

However, the biggest coup, from a scholarly perspective, was made by a French expedition team led by the young linguist Paul Pelliot (1906–1909). Pelliot, dubbed “Prince parmi les sinologues,” was a brilliant polyglot who had distinguished himself in the defense of the French delegation during the Boxer Uprising in Beijing (1900).Footnote 64 Near Dunhuang, he discovered in the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas a priceless collection containing thousands of manuscripts as well as numerous paintings on silk, hemp and cotton cloth that would shed a spectacular new light on the diffusion of Buddhism in Central Asia and China.Footnote 65 The library had accidentally come to light when a local monk decided to refurbish a cave temple. Pelliot had come well prepared; he kept in close touch with his German colleagues at the Museum für Völkerkunde in Berlin and had, due to his wife’s Russian background and contacts, direct access to the latest publications and discoveries made by Russian expedition teams. Furthermore, Pelliot distinguished himself by his command of local languages, including Chinese, Russian, Uighur, Turkish, and an even rarer knowledge of the ancient Tocharian and Sogdian scripts. Whereas Stein had during an earlier raid of Dunhuang’s notorious walled-up library of Cave Number 17, removed primarily manuscripts with Indian scripts and a number of others with a happy-go-lucky approach, Pelliot browsed frantically for three weeks through the whole collection to select the specimens he considered to have most scholarly value.Footnote 66

The main trigger for these explorations was the initiative, proposed during the 7th International Congress of Orientalists in Rome (1899) and later institutionalized at the 8th Congress in Hamburg (1902), to establish an International Committee for the historical, archaeological, linguistic and ethnographic exploration of Central Asia and the Far East.Footnote 67 By that time the first fragments of texts in the Kharosthi and Brahmi scripts had already found their way to Europe. Most notable among these documents was the so-called Bower manuscript, named after the British intelligence officer Hamilton Bower. While touring Chinese Turkestan in 1889, Bower had obtained a series of birch-bark documents from the Kucha region whose oblong-shaped leaves (pothi) were, as the German-British Orientalist Rudolf Hoernle discovered, written in the ancient Brahmi scripts.Footnote 68 The manuscript, dating back to around the sixth century ce, contained fragments of Indian medical texts and invocations of the Buddha and several Hindu deities. Far older than any such documents found in the subcontinent, it caused a sensation in scholarly circles and provided evidence for the diffusion of Indian languages and ideas beyond the Himalayas. As the eminent Indologist Sten Konow noted, these new finds in Chinese Turkestan revealed “what a predominant role Indian Civilisation played in Asia at a very early period” and threw an “unexpected light … on many questions concerning Indian archaeology itself, Indian art, Indian literature, and Indian history.”Footnote 69

Recovering this past could no longer rely on individual initiative alone and demanded international coordination and intellectual cooperation. In a lecture delivered during the Hamburg Congress, Stein had flagged in front of his colleagues, including the Dutch Sanskritist Hendrik Kern, Foucher and Grünwedel, the tantalizing prospect of further archaeological exploration in Chinese Turkestan. His talk was accompanied by “beautiful lantern views of the scenes visited and objects found during his expedition” and even “a select collection of the antiquities and specimens of writing brought back by him.”Footnote 70 The Arabist C. J. Lyall, reporting back to the Indian Government, considered Stein’s performance in Hamburg “the most interesting and most appreciated” feature of the Congress.Footnote 71

Rising nationalist sentiments and animosities were, initially at least, not an insurmountable obstacle for international scholarly cooperation. As Sylvain Lévi noted in 1914, even in “days of exacerbated nationality, a calm and refreshing breeze of wide humanity blows in the happy corner of Central Asian studies.” He added, for good measure, that he had never witnessed before “such an extensive exchange of visits between savants of all nations” as had been triggered by “the discoveries of Turkestan.”Footnote 72 Such lofty talk notwithstanding, there was an obvious competitive edge to these early expeditions in which different governments, as well as the explorers themselves, were keen to claim the glory of the most spectacular discovery for their respective nation, if not for themselves. Moreover, any existing sentiments of scholarly solidarity turned out to be short-lived. World War I intervened and not only ruptured the “Orientalist Republic of Letters” but also made direct contact almost impossible. Some scholars had to exchange their desk and spade for a gun. Paul Pelliot, for example, found himself, only a few years after his spectacular discovery in Chinese Turkestan, at the Dardanelles front. The International Congress of Orientalists would not gather for almost two decades but when the meetings resumed in 1928, the more jovial interactions that characterized the early Congresses had, especially in the case of French–German interaction, cooled down considerably.Footnote 73

The impact of the expeditions was, however, momentous. A vast collection of newly discovered manuscripts allowed scholars to reconstruct the complex networks of missionaries, pilgrims and patrons that facilitated the diffusion of Buddhism in Central Asia and China. In order to do so, scholars had to crack the code of a number of newly discovered “dead” languages such as Sogdian, Tangut, Khotanese Saka, Tocharian, and Kushano-Bactrian. Above all, these archaeological expeditions, as well as later discoveries in Bactria by the Mission Archéologique française en Afghanistan (1924–1925), led by Alfred Foucher, revealed to what extent Indian civilization had influenced and fused with the Chinese, Persian and Turkish spheres in Central Asia.Footnote 74 The “Greek factor,” which had – in particular with reference to the hybrid Indo-Greek sculptural tradition of Gandhara – been made so much of in relation to the subcontinent’s history in the nineteenth century, was now properly reduced to just one force leaving its imprint on a sphere that witnessed over the centuries the most bewildering experiments in cultural symbiosis and cross-fertilization. Tangible evidence went beyond mere linguistics and came often in the form of sculptures, frescos and coins that powerfully illustrated such connected histories. To get an idea of what such a “Silk Road polity” had looked like, a scholar just had to pick up a Kushan coin on which Bactrian scripts combined Greek letters to write a Persianate language, and Buddhist motifs blended with an eclectic pantheon of Greek, Hindu and Persian deities.Footnote 75 As the eminent French Indologist Sylvain Lévi evocatively put it, the archaeological explorations in Chinese Turkestan had revealed a veritable “Babel des croyances humaines,” an ancient discursive space where Buddhist monks mingled with Nestorian Christians, Zoroastrian priests and followers of the prophet Mani.Footnote 76

In order to illustrate how the Classical/Greek lens was increasingly complemented by a new perspective which stressed the impact of Indian civilization in Central Asia and China, it is worthwhile to zoom in on the career and writings of Aurel Stein. More than any other archaeologist of his generation, Stein’s missions in Chinese Turkestan, sponsored by the British Raj and narrated for a broader audience in attractive prose, brought to light a lost civilizational template that, he alleged, bore a strong Indian imprint.

Aurel Stein: Pioneer of the Silk Road

Buddhism is a historical fact; only it has not yet been completely incorporated into history: sooner or later that will be achieved.

One knows these modern travellers, these overgrown prefects and pseudo-scientific bores despatched by congregations of extinguished officials to see if sand-dunes sing and snow is cold. Unlimited money, every kind of official influence supports them; they penetrate the furthest recesses of the globe; and beyond ascertaining that sand-dunes do sing and snow is cold, what do they observe to enlarge the human mind?

Born into a Jewish family in the booming Austro-Hungarian metropolis of Budapest, the odds that Aurel Stein would emerge as one of the most famous archaeological explorers employed by the British Raj were decidedly low. Educated in Dresden and Vienna, Stein developed an interest in Sanskrit studies and followed lectures in Leipzig and Tübingen with well-known Orientalists such as Georg Bühler and Rudolf von Roth. In 1885, he moved to England with the aim of studying the Oriental collections held in Oxford, Cambridge and London. There he made the acquaintance of the Assyriologist Henry Rawlinson and the Scottish Orientalist Henry Yule who, together with the example set by the elusive Hungarian explorer Sandor Csoma de Koros, inspired Stein to contemplate a career path in India.Footnote 79 Academic positions in Europe were scarce and Stein followed in the footsteps of Orientalists such as Georg Bühler and Hendrik Kern who used a temporary sojourn in India to polish their Sanskrit with local pandits and collect precious manuscripts in the hope that India would eventually become the springboard that landed them on a Sanskrit chair in Europe. Thus, when the dual position of Registrar at Punjab University and Principal of Oriental College Lahore became vacant, Stein embarked in 1887 with high hopes from the port of Brindisi on a new adventure that would start, as for so many other first-timers, once the contours of Bombay became visible in the distant haze.

From Stein’s first book project, a translation of Kalhana’s Rajatarangini: A Chronicle of the Kings of Kashmir (1900), it is clear that his initial entry point into the world of Indology was Sanskrit studies. But as the months in India turned into years, Stein moved beyond the confines of classical philology and developed a penchant for more “hands-on” tasks. Over time, he became less inclined to see a professorship in Europe as the desired destiny of his career: India had opened up a new world of opportunities in terms of archaeological exploration and surveying, a useful skill he had acquired during his year of military training in Hungary. This would turn out to be helpful in selling some of his later expeditions as surveying-cum-archaeological missions to the utilitarian bureaucrats of the Raj.Footnote 80

The travels and travails of the youthful world-conqueror Alexander the Great were the great driving force behind Stein’s curiosity. When he joined the French scholar Foucher on a tour of Gandharan sites in the Swat Valley (1896), he imagined himself “on classical soil and enjoyed every minute of it.”Footnote 81 His first major expedition (1898) saw him joining the Buner field force on a punitive raid into Baluchistan where he aimed to shed light on the Macedonian hero’s route while the officers dealt with “tribal disturbances.”Footnote 82 His fondness for all things Greek was expressed in tiny details. The bookplate that graced his publications was designed by his friend Fred Andrews and featured Pallas Athena. Yet although Stein never quite shed his classical lenses, his sojourn in Lahore opened up new horizons. Under the tutelage of Lockwood Kipling, father of Rudyard and curator of the Lahore Museum, Stein studied the first specimens of Gandharan sculpture that had been unearthed in Taxila. This triggered a lifelong interest in Buddhist art and shifted his gaze beyond the Himalayas where the deserts, or so he surmised, might yield spectacular finds.

With a much-leafed copy of Xuanzang’s Great Tang Records on the Western Nations in his pocket and a well-provisioned expedition force, Stein intended to follow in the footsteps of Sven Hedin, the Swedish surveyor and pioneer of exploration in Chinese Turkestan who had visited some of the key sites Stein hoped to excavate.Footnote 83 Yet convincing the penny-pinching officials of the Raj – “the Boa Constrictor of Babudom” in Stein’s somewhat unhappy formulation – of the necessity of embarking on such long and expensive trips which involved generous conditions of leave from his official duties in the Punjab, required dogged persistence and above all diplomatic skill.Footnote 84 According to his biographers, Stein possessed both and had also the good fortune that his first expedition coincided with the brief Viceroyalty of Lord Curzon, whose Forward Policy and appetite for trans-frontier exploration was combined with a deep interest in history, archaeology and geography.Footnote 85 Stein and Curzon were already acquainted before Stein pitched his expedition proposals. They had met in Lahore where Stein had guided Curzon through Kipling’s collection of Gandharan sculpture. Curzon’s interest in the region is evident from a book on the source of the Oxus river that he wrote before assuming the position of Viceroy of British India.Footnote 86

All the same, Chinese Turkestan lay “beyond the stimulating influence of Bible associations” and Stein had to find compelling arguments to persuade the administration to give a green light for missions in territories beyond the Raj.Footnote 87 Stein’s strategy was twofold. On the one hand, he played the competitive card and framed the area around Khotan, an important oasis on the southern rim of the Taklamakan Desert, as belonging to the “British sphere of influence.”Footnote 88 The paper trails of the multiple Stein expeditions in the National Archives of India (NAI), reveal that Stein succeeded in making the competitive quest for archaeological treasure in Chinese Turkestan a matter of Government concern in which “imperial honour” was at stake.Footnote 89 Although Stein was by birth an Austro-Hungarian Jew, he had become a naturalized British citizen and was awarded a KCIE (Knight Commander of the Indian Empire) in 1912. Among the Chinese dignitaries he encountered in towns such as Khotan, he was keen to play his part as a representative of the British Empire and often took care to dress in his European finery: black coat, sun-helmet and patent leather boots. Competition was, however, not only a matter of geopolitics or imperial rivalry. It was also deeply personal. There was always the lingering fear that the Germans or French would outflank him in the race to Khotan and reach sites where plenty of loot was to be expected earlier than he did. As his first biographer, Jeannette Mirsky, points out, Stein was particularly wary of the Germans who “always go out hunting in packs” and by the time of his third expedition, he had come to regard Chinese Turkestan as a personal preserve whose marvelously textured past he had almost single-handedly brought to light.Footnote 90

A second strategy employed by Stein to garner support for his missions consisted of playing up the deep influence of Indian civilization in these far-flung regions. John Marshall, Director General of the ASI, downplayed the competition for spoils as a valid argument for further expeditions and repeatedly implored Stein to devote his energies to excavate sites within British India. Undeterred, Stein stressed that Chinese Turkestan was a field “in which India may justly claim a predominant interest,” because “the spread of Buddhist religion and literature over Central Asia and into the Far East is the greatest achievement by which India has influenced the history of Asia in the past.”Footnote 91 Khotan, Stein reminded officialdom, was “distinctly Indian in origin and character” and systematic exploration would hence “yield finds of great importance for Indian antiquarian research.”Footnote 92 After multiple Central Asian expeditions, Stein’s notion of Indian civilization had become much more elastic than Marshall’s and he suggested that Chinese Turkestan was part of India’s cultural patrimony and fell, thus, within the purview of the Raj’s custodianship.Footnote 93

Furthermore, Stein and other explorers had long warned that “natives” could not be trusted with these priceless artifacts. Buddhist statuary and murals, in particular, were deemed at risk of religiously motivated desecration and had to be “saved for science” before iconoclastic Muslims, “treasure-seeking natives” and the local climate reduced what was left to rubble. This framing implied that Chinese Turkestan was a geopolitical void and evaded the question of Chinese sovereignty in the region. In the first decades of the twentieth century, recurring civil wars following the dissolution of the long-teetering Qing Empire prevented an effective exercise of sovereignty in Chinese Turkestan and provided a window of opportunity for explorers like Stein that lasted until the 1920s.Footnote 94 Stein and Le Coq typically evoked Chinese Turkestan as a place “lost in time,” a frightful desolate waste of arid deserts, tamarisk scrub and barren mountains where the life-giving rhythm of civilization had long since ceased to beat. It was depicted as a place of romance and adventure and not for the faint-hearted; frostbite was common, brackish water often the only life-sustaining liquid to be had, and long trying marches separated the sparse archaeological sites. Only at remote intervals did apricot and mulberry trees announce the proximity of an oasis town promising a temporary relief from the monochromatic khaki of the desert and the notorious sandstorms called buran.Footnote 95 Yet, as The Times deftly reported in 1907, the intrepid explorers carrying the banner of Western science in these remote regions were rewarded because sometimes “a mere scraping of the surface sufficed to lay bare files of records thrown out before the time of Christ.”Footnote 96

Stein was well aware of this unique moment. Already in 1912, he requested the authorities to swiftly approve his expedition, because “the Chinese Government (has not) as yet raised objections to foreign exploitation of ancient remains in the country. But it is impossible to foresee how long such favourable conditions will last.”Footnote 97 Chinese Turkestan was one of the last “free-for-all” sites where archaeologists and treasure seekers could slip their spoils across the border without risking intervention from the local authorities. In Egypt, the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East, the likes of Lord Elgin, who infamously looted the Parthenon marbles from Athens’ Acropolis at the beginning of the nineteenth century, were increasingly bound to stricter regulations and had a more disadvantageous (from the viewpoint of Western sponsors and museums) sharing of the finds.Footnote 98 Stein also engaged in surveying operations although the local authorities repeatedly warned the British Consul in Kashgar that Stein “must travel in a manner conformable to treaties, and must not survey.”Footnote 99 But when Stein embarked on a Fourth Expedition in 1930, the Chinese authorities were reluctant to let him proceed and insisted that all finds were to remain in China. The Chinese had closed the door on him at last and after a few unsuccessful and cumbersome months he was forced to return to India empty-handed.Footnote 100

The Chinese objection to archaeological missions led by foreign powers was as much informed by concerns over sovereignty as by a renewed national interest, from the 1930s onwards, in the ancient Han incursions into Central Asia. As Nile Green observed, in the first decades of the twentieth century, Chinese translations of Stein’s travelogues and Chavannes’ work on the Tang-era accounts of Chinese Turkestan, had fueled interest in this region as part of China’s “national” past.Footnote 101 Correspondingly, Chinese scholarly interest focused on the Chinese manuscript hoards and finds recovered from the desert sands or cave libraries. This cannot be solely attributed to nationalist agendas; in the early twentieth century, only a few European specialists could distinguish and decipher the scripts of ancient dead languages such as Sogdian, Tangut, Khotanese Saka, Tocharian and Kushano-Bactrian. Hence, when a Chinese official stationed near Dunhuang in the early 1900s dismissed a series of Sanskrit sutras that had come to light as a “flurry of raindrops in a windy storm, with letters puny as flies,” he was no exception.Footnote 102

It is important to bear in mind that the Chinese framing of the European archaeological expeditions in Central Asia as criminal endeavors hurtful to national interest only gained momentum in the mid-1920s. As Justin M. Jacobs has shown, the Chinese reaction had initially been ambivalent, combining an element of personal praise for the “hardy” European explorers such as Stein and Pelliot, whose contributions to Sinology were valued, with a more neutral assessment of the act of removing and transporting these objects abroad.Footnote 103 In fact, by the late 1920s, when Stein was debunked as an imperialist treasure seeker, Sven Hedin returned to Chinese Turkestan to co-direct, together with the philosopher and historian Xu Xusheng, a Sino-Swedish expedition which brought him fame in Chinese scholarly circles.

“On the ground” in Chinese Turkestan, Stein and other expedition teams relied on local officials whose cooperation, hospitality and willingness to procure essential supplies were indispensable.Footnote 104 When local Chinese administrators or monks questioned Stein’s appropriation of artifacts and manuscripts, he brushed these objections aside.Footnote 105 However, when he got access to the secret library at the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas, Stein was torn about the ethics of removing materials from a site where Buddhism was still actively practiced. Stein decided that frescos and sculptures belonged to popular cult practices and should be left undisturbed (he nevertheless removed numerous paintings from Dunhuang), while manuscripts had to be salvaged for experts able to read or decipher them. Not all explorers shared Stein’s ambivalent attitude towards the ethics of their practices. Albert von Le Coq had no scruples about writing above the entrance of his temporary lodgings in huge letters “ROBBERS’ DEN.”Footnote 106

Finding Indian Influence on a Cultural Palimpsest

In the 1920s, archaeological discoveries received extensive news coverage across the globe. Stein’s expeditions shared the limelight with Howard Carter’s spectacular discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun (1922) and Leonard Woolley’s excavation of Ur in Mesopotamia.Footnote 107 It is estimated that Stein’s missions alone yielded a staggering 40,000 artifacts and manuscripts that ended up in museums in Britain and India.Footnote 108 The archaeological discoveries in Chinese Turkestan brought to light a cultural palimpsest on which Indian, Tibetan, Iranian, Chinese, and Turkic influences mingled with classical impulses that had been radiating from the Greco-Roman world. Albert von Le Coq captured the sentiment of revelation widely shared among archaeologists with an interest in the East:

Since the exploration of the ruins of Nineveh by Sir Austin Henry Layard, no expedition has yielded results that can be compared in importance with those achieved by these researchers in Central Asia; for there a New Land was found. Instead of a land of the Turks, which the name Turkestan led us to expect, we discovered that, up to the middle of the eighth century, everywhere along the silk roads there had been nations of Indo-European speech, Iranians, Indians, and even Europeans.Footnote 109

This concept of the “Silk Roads” as a label for the ancient trade nexus between China and the Mediterranean was a relatively new notion. Baron Ferdinand von Richthofen (1833–1905), a German geographer who traveled in the Lop Nor region, had coined the term Seidenstrasse(n) in 1877.Footnote 110 The pioneering expeditions of Stein, Le Coq, Grünwedel and Pelliot imbued the concept with new meaning by opening up vistas of cultural geography that would eventually redraw the fault lines that assigned civilizations to clearly demarcated zones. Thanks to Stein’s impressive photographic record, specialists who had not traveled to Central Asia could help identify the contributions of Greco-Roman, Indian, Iranian, Tibetan, Uighur and Chinese schools of arts, including their regional variations. In the process, they brought to light one of the most remarkable experiments in cross-cultural artistic borrowing that the ancient world had witnessed.Footnote 111 The notion of culture as something self-contained and immobile received a severe blow as the Silk Road discoveries revealed how porous civilizational spheres had really been. The finds of Stein and his colleagues provided spectacular evidence that routes often trumped roots in the development of culture, and made a significant contribution to the evolution versus diffusion debate that occupied anthropologists, prehistorians and historians alike.Footnote 112 The Serindian art displayed in museums in Paris, London, Berlin, Delhi, St. Petersburg and Tokyo further destabilized the old Winckelmannian perspective that interpreted art traditions as rarified and isolated phenomena operating according to a logic of autochthonous and organic evolution (and decline). The sculptures and frescos discovered in Chinese Turkestan undermined this paradigm by revealing that a unique art could evolve by blending different aesthetic traditions into a new stylistic vocabulary.

Figure 1.1 Gandhara Buddha, 1st–2nd century ce. The European “discovery” of the Gandharan sculptural tradition inspired art historians to trace the imprint of “Hellenistic artistic genius” on the arts of India and Asia. In the first sculptural representations of the Buddha, the Greco-Roman stylistic influence is reflected in the folds of the drapery and iconography. This statue, from around 200 ce, is exhibited in the Tokyo National Museum.

Figure 1.3 Aurel Stein, here with his expedition team at Ulugh-mazar (center, with dog), opened up new (art) historical vistas by tracing the spread of “Indian” aesthetics and culture in Chinese Turkestan or “Serindia.”

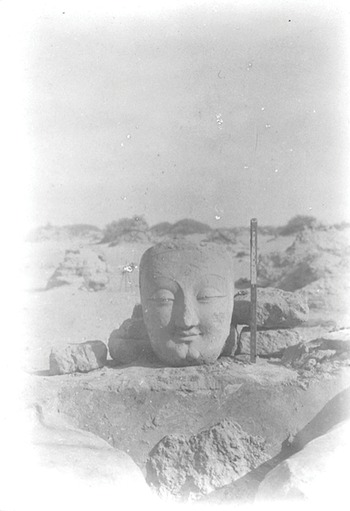

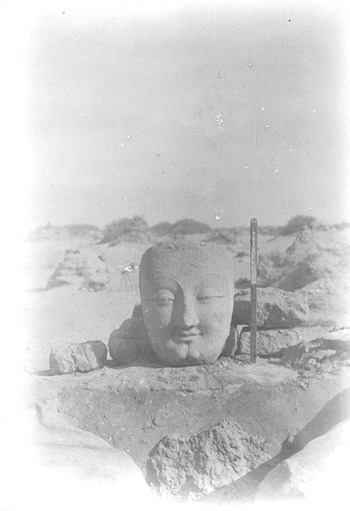

Figure 1.5 View of excavated Buddha head from ruin M.I.I. at Miran, Stein Expedition, December 1906. Archaeological discoveries in Miran, Khotan, Kucha and Turfan revealed an ancient Buddhist civilizational template and inspired GIS members to study ancient India’s civilizational imprint on Central Asia and the Far East.

The romantic appeal of hybrid Silk Road polities notwithstanding, the identification of multiple layers of culture and different aesthetic traditions was informed by a clear hierarchy with regards to which artistic and civilizational legacies were most keenly traced.

First, a persistent classical bias ensured that every artifact hinting at Greco-Roman influence was hailed as proof that the onward march of classical culture had not petered out among the hills of the Swat Valley, but spread its touch of artistic genius in the guise of the Buddha image deep into China and from there to Korea and Japan.Footnote 113 Whereas the manuscripts hinted at a polyglot Buddhism, the artifacts – often in the form of frescos, stucco-reliefs and seals – bore marks that no classically trained archaeologist was likely to misattribute. All the talk of degeneration notwithstanding, traces of Gandharan art in Khotan and beyond were hailed as evidence revealing the Far Eastern odyssey of Greco-Roman art. As Stein had written:

the vista thus opened out to us is one of far-reaching historical interest. We already knew that classical art had established itself in Bactria and on the north-west frontier of India. But there was little to prepare us for such tangible proofs of the fact that it had penetrated so much further to the east, half-way between Western Europe and Peking.Footnote 114

At Keriya, Niya, Lop Nor and Miran, “the colossal stucco relievos show[ed] the closest relation to Graeco-Buddhist sculpture of the first centuries of our era” and the frescos were “so thoroughly Western in conception and treatment that one would expect them rather on the walls of some Roman villa than in Buddhist sanctuaries on the very confines of China.”Footnote 115 At the same time, classical art was under a constant threat of becoming further “debased” by blending with “Oriental aesthetics.” As Le Coq noted of a statue unearthed at Karakhoja, it was still sublimely classical in the Gandharan style and “not yet degraded by Eastern Asiatic misunderstandings of classic forms.”Footnote 116

The explorations in Chinese Turkestan could thus be read as a quest for the spatial horizons of classical aesthetics. It is perhaps not surprising that European explorers were genuinely excited to find in far-flung lands traces of familiar Greco-Roman art, and we should bear in mind that they were hardly expert judges of art that they had never encountered before and often evaluated under trying conditions. Nevertheless, a classical confirmation bias permeates the accounts of archaeologists active in Central Asia. For example, upon leaving Niya, Stein mused: “Where will it be next that I can walk amidst poplars and fruit trees planted when the Caesars still ruled in Rome and the knowledge of Greek writing had barely vanished on the Indus?”Footnote 117 Such thoughts become doubly suspect when Stein reveals in the same account that the key finds in Niya comprised a large collection of perfectly preserved wooden tablets that equaled “the aggregate of all the materials previously available for the study of Kharoshthi, whether in or outside India.”Footnote 118 While unearthing some of the most important documents that could shed a light on the diffusion of Buddhism from India to Chinese Turkestan, Stein appeared thus mentally disengaged and wallowed in the romance of classical allusion. Le Coq remained too under a Philhellenic spell and tellingly titled his expedition account Auf Hellas Spuren in Ostturkistan (1926), although his main finds comprised Buddhist art and Indian manuscripts rather than Grecian antiquities. Le Coq had a low opinion of Buddhist art, which he considered “horrid” and “boring,” and it was the quest for Hellenistic traces which inspired him to undertake expeditions into Chinese Turkestan.Footnote 119

Even in Dunhuang’s frescos, where evidence of Greco-Roman influence was tenuous, classical traces were still equated with the highest artistic merit. Stein’s classical notion of aesthetics went beyond a taste for simplicity and proportion. Like many of his European contemporaries, Stein disapproved of the Hindu and Mahayana practices that depicted deities with multiple limbs. With respect to Dunhuang, he approvingly wrote that “it was pleasing to note the entire absence of those many-headed and many-armed monstrosities.”Footnote 120 Pelliot, working at the same site, also praised the chaste and decent nature of the art, and contrasted it with the “obscene” and “lewd” Tantric tradition of sculpture which he evidently abhorred.Footnote 121

Stein identified Khotan as the crucial hub from which classical aesthetics had radiated eastwards into China proper. However, in contrast to the Gandhara region, there was no evidence to suggest that “Greek artists” had ventured so far east. Instead, the notion of Khotan as a center of aesthetic diffusion for a much larger region was backed up with historical theories that speculated about the conquest and even colonization of Khotan by “Indian immigrants” from Taxila.Footnote 122 This theory would be further disseminated by Sylvain Lévi, who referred to another oasis town, Kucha, as a “colonie aryenne.”Footnote 123 In short, the implication was that Indian agency, and especially the Kushan dynasty under the leadership of the famous patron of Mahayana Buddhism, Kanishka the Great, was responsible for diffusing the legacies of classical art in the oasis towns of the Taklamakan Desert where no Macedonian had ever ventured.

Second, the diffusionist narrative that emerges from the accounts of Central Asian explorers betrays another bias: ancient China featured almost always as the passive recipient of cultural influences from the West and was assigned little historical agency in Chinese Turkestan. At best, the Chinese role was reduced to a barely visible scribble on a cultural palimpsest boldly marked by Hellenistic, Indian and Iranian legacies. As Le Coq noted with some surprise, despite the strong Chinese imperial presence in this region throughout the centuries, it was “impossible to find anywhere the slightest suggestion of Chinese influence in either the architecture, painting, or sculpture of these subordinate peoples. All their forms are Indian or Iranian on a late classical basis.”Footnote 124 Stein is another case in point when it comes to “Chinese blinders.” He did not read Mandarin and approached Chinese Turkestan with an Indocentric perspective, meaning that he was mainly interested in the region as the endpoint of civilizational waves and aesthetic impulses emanating from the west and south. For example, at Dunhuang, Stein reported how he frantically browsed through numerous scrolls and manuscripts in the hope “for finds of direct importance to Indian and Western research.”Footnote 125 Ironically, Chinese logistical support and ancient Chinese pilgrim accounts enabled Stein to inscribe India and the Classical West onto the civilizational template of Chinese Turkestan while leaving out much of the Chinese contribution to its richly textured past. A Chinese review of Stein’s On Central Asian Tracks in fact discredited the work on account of Stein’s linguistic inability and noted that the monograph did not include a single Chinese character.Footnote 126 Apart from a short-lived obsession that saw Stein tracing the Chinese limes and the occasional reported find of a Chinese copper coin, a piece of lacquered wood or a slat of tamarind inscribed with Mandarin characters, Chinese antiquities were mostly curiosities of little consequence for the overall historical panorama that Central Asian explorers, perhaps with the exception of Paul Pelliot, presented to their readers.Footnote 127

Third, how did the notion of Indian influence factor in this picture? Was it simply subsumed under the Hellenistic Gandharan label or assigned a narrative thread of its own? Both, it seems, were the case, but in British India, Stein’s allusions to the ancient diffusion of Indian civilization piqued most interest and gave rise to accounts in which ancient India replaced “Greece” as the fount of an expansive classicism.Footnote 128 Stein’s own thought evolved too and while his Philhellenic obsessions never slackened, he developed a deep interest in India’s civilizational imprint beyond the Himalayas. His Sanskrit education had been an indispensable intellectual foundation that allowed him to identify Indian scripts – inscribed on wooden, wedge-shaped tablets or impressed on birch-bark – when these came to light during excavations. As Stein put it, “the early spread of Buddhist teaching and worship from India into Central Asia, China and the Far East” was “the most remarkable contribution made by India to the general development of mankind.”Footnote 129 Besides, aiming at a readership that transcended the small circle of specialists, Stein had early on realized “the necessity of enlisting the interest of [the] wider public for a field which has yet much to reveal as regards the far-spread influence exercised by the ancient civilization, religion, and arts of India.”Footnote 130 The shift from Greece to India was never complete but if the latter did not quite replace the former, the two interests certainly coexisted. A long front-page rendering of Stein’s travails in The Times Literary Supplement evoked this shift by describing how Stein’s interest in Alexander found him, rather unexpectedly, on the trail of Chinese pilgrims and the Buddha:

At the very outset of the long journey we find Sir Aurel, as he rides along the Talash Valley, alert to note the physical features of the scene of one of Alexander’s mountain campaigns, and deciding that the broad military road which he was travelling had seen the Macedonian columns pass by on their way to India … But soon the traveller is on the look-out for vestiges of a very different kind from those of the conqueror from Greece: he is tracing the footsteps of the Chinese pilgrims, solitary wayfarers, led across fearful deserts to seek the holy places of the Buddha in his native land. And at once we are brought into touch with two great movements which have been momentous in the history of mankind – the marvellous march of Alexander into India, and that other progress out of India to the remoter East, the victorious journey of the Buddhist faith.Footnote 131

This, we should remind ourselves, was a new perspective on India’s ancient history. As Foucher had noted in 1914, the transregional circulation of Buddhism had been established as an historical fact but its legacies still had to be incorporated into historical narratives.Footnote 132 When John William Kaye wrote his History of the War of Afghanistan in 1851, he could dismiss the Buddhist legacy of the region in one sentence: “I have very little to say [about the Buddhas at Bamian] except that they are very large and very ugly.”Footnote 133 With the advance of Buddhist studies, the discovery of Gandhara and other Buddhist monuments on the subcontinent, and the groundbreaking expeditions in Chinese Turkestan, such statements soon belonged to a benighted past. Buddhism, interpreted as reflecting an instance of Indian civilizational agency, had spread far and wide and so did Indic literary and aesthetic traditions.Footnote 134 Despite their many failings, biases and questionable ethics, archaeologist-explorers such as Stein opened up historical vistas that set new terms for writing the history of ancient India and the wider region. A “lost” Buddhist geography had been unearthed and was incorporated into world and art historical narratives. As a result, the notion of Indian civilization was reconfigured – in terms of historical agency, India, the Buddhist heartland, had “arrived” as a shaper of world history in Asia, and in terms of space, the notion of Indian civilization had become more elastic, encompassing a cultural geography that reached far beyond the Himalayas.

From Serindia to Greater India: Indian Readings of the Silk Road Exploits

Thus the desert sands had things concealed in their bosom which were long lost to India.

Forgetfulness would have been a bliss, if the subconscious had not retained the memories of the past to unloose them at the crucial moments. Past would have been a dead past, if the earth had not preserved in its bosom the ancient foot-marks to help its recovery.

In British India, the Silk Road exploits of European archaeologists, but in particular Aurel Stein, had received widespread coverage in dailies and monthlies such as the Modern Review and the art historical journal Rupam.Footnote 137 By the mid-1920s, the notion that Serindia was part and parcel of a Greater Indian civilizational sphere had become de rigueur among scholars associated with the GIS. According to GIS member, Government epigraphist and later Director General of the ASI Niranjan Prasad Chakravarti, the collections of paintings, sculptures and manuscripts unearthed in Chinese Turkestan had thrown new light on various complicated problems of Indian history.Footnote 138 The prominent Indologist and historian R. C. Majumdar praised in his lectures “the wonderful archaeological explorations of Sir Aurel Stein” which had revealed “the nature and extent of the cultural influence of India in this region.”Footnote 139 Another Bengali intellectual with an interest in the legacies of ancient India, Benoy Kumar Sarkar, hailed the various expeditions for their contribution in bringing “to light an underground ‘Greater India’ from among the ‘ruins of Desert Cathay’.”Footnote 140 In his Presidential Address to the All-India Oriental Conference held in Baroda in 1934, K. P. Jayaswal likewise emphasized how “knowledge of the expanse of Indian culture in Central Asia is being widened” through the efforts of European and American archaeologists and, above all, “our indefatigable scholar Sir Aurel Stein.”Footnote 141