An obscure nineteenth-century French portrait of two women of color has recently enjoyed some newfound popularity, even though its full story remains elusive.1 The simple title of the drawing alone is intriguing: “Signare et negresse de Saint-Louis en toilette.” Even those who do not read French can pick out the word “negresse” and guess that it is a reference to the black or “Negro” woman standing with her head tossed back and to the side. But what was a signare? The viewer might guess correctly that the term “signare” refers to the fair-skinned woman seated at the focal point of the drawing. Solving the rest of the puzzle requires more specialized knowledge about foreign places and French terms. Saint-Louis is not a reference to the mid-western American city, but the name of an island just off the coast of Senegal in West Africa. The phrase “en toilette” translates as “full dress.” But who were these women, and why would they have been portrayed in this extravagant clothing that made use of European and African styles to create something more, at the same time?

Fueling the mystery, scholars debate who the women in the image were, or at least who the signare was. A signare (“lady”; derived from the Portuguese word senhora) was an elite woman of African descent from the region of Senegal and neighboring coastal regions. The “Negro woman” would have been a servant or, more likely, a formerly enslaved woman, recently freed in the aftermath of the 1848 French Revolution and emancipation decree.2 The portrait was an engraving that first appeared in a travel magazine in 1861, but it was itself a copy of a drawing, based on a watercolor, believed to have been painted in Paris around 1849. One scholar has argued that the seated woman, the signare, was Mary de Saint-Jean, the wife of Barthélémy Durand Valantin, a free man of color, who in 1848 was the first man elected from Senegal to the French Chamber of Deputies.3 In fact, Mary de Saint-Jean’s own compelling background and biography make her an attractive candidate as the unnamed signare at the center of the image.

Mary de Saint-Jean was the daughter of the mayor of Gorée, also a free man of color, but her mother, Annacolas Pépin, has an even more enduring legacy in the historical record. Anne-Nicolas (Annacolas) Pépin was the grand-niece of Anne Pépin, who was rumored to have been the lover of the French governor of Senegal at the end of the eighteenth century. Anne Pépin has become almost a mythic character in the history of Gorée, but traces of her prosperity also remain in the historical record. Art historian Mark Hinchman has uncovered records for nine homes that belonged to Anne Pépin at some point in her lifetime. Her relatives and descendants carried forward her legacy. Anne Pépin’s brother, Nicolas Pépin, also a wealthy merchant, built the fancy house that has become associated with his daughter, Annacolas, who also became rich and influential in her own right.4 That home, with its iconic double spiral staircase, was immortalized in a drawing by Adolphe d’Hastrel de Rivedoux; the house is simply described as “A Residence at Gorée (House of Anna Colas).” Today, the building has been transformed into a museum known as the Maison des Esclaves (The House of Slaves), one of the most infamous, controversial, and visited tourist attractions in West Africa.5 If scholars agree that Annacolas Pépin owned this (now notorious) home, others are not convinced that the woman in “Signare and Negro woman from Saint-Louis in Full Dress” was her daughter Mary de Saint-Jean.6 But it may not matter if the woman was Saint-Jean. Instead, it is important when and where the lost watercolor likely was originally completed and the fact it featured the otherwise ignored “Negro woman.” The image of the women (Figure P.1) provides more than a simple glimpse into the curious life on a small island off the coast of West Africa. Instead, the two women relate to a longer, more interesting story about the legal practices and cultural significance of citizenship in France’s Atlantic world empire.

Figure P.1: “Signare et négresse en toilette,” (Signare and Negro Woman in Full Dress).

This reproduced drawing may depict Mary de Saint-Jean, wife of the first man of color to serve as a representative in the French Chamber of Deputies between 1848 and 1851, together with a woman who was probably formerly enslaved. If it was Saint-Jean and she was in Paris at the time, the image illustrates this history of Gorée as an insular community that also faced outward to the rest of the world. On the surface, the image depicts two unnamed women of color of very different social standings. Hidden behind the coy expression of the seated woman is the long-standing political influence of signares as merchants and property owners. The woman standing next to her also could represent hundreds of thousands of enslaved people who were freed under France’s second emancipation decree in 1848.

At best, the evidence that the woman in the image was Mary de Saint-Jean is circumstantial since so many signares featured in artwork during the nineteenth century were not identified by name. Less controversy surrounds the idea that the creator of the original image was Edouard Auguste Nousveaux, an official artist for the Ministry of the Navy. Nousveaux had spent time in Senegal in the early 1840s but it is believed that he painted the original watercolor of “Signare and Negro Woman” in his studio in Paris around 1849. The year 1848 had been auspicious: it marked the beginning of the short-lived Second Republic (1848–52), during which the Provisional Government decreed slave emancipation in France’s empire, for a second and final time. In the whirlwind of revolutionary fervor, the Provisional Government also deemed the French-controlled outposts based at Gorée and Saint-Louis in Senegal eligible to elect one representative to the Constitutional Assembly and the Chamber of Deputies. Saint-Jean’s husband, Barthélémy Durand Valantin, was voted in as deputy in 1848 and 1849 but had resigned by 1851. By 1852, the seat was suppressed by the dictatorship of Napoleon III. Even if the stint was brief, Saint-Jean reputedly lived in Paris sometime around 1848 and 1849.7

Whether or not the women’s identities can be confirmed, their portrait is striking for how it staged both women in their version of their “Sunday best,” without hinting at the importance of the historical moment. If it is Saint-Jean, she sports a coquettish half-smile and is adorned in classic signare attire. Her outfit includes an elaborate headscarf done up in the shape of a pointed crown, a billowy white blouse, and a voluminous throw tossed over her shoulder and the lap of her hoop skirt. While the blouse and hoop skirt would have blended in well in the streets of Paris, her headdress and her piece of elaborately patterned brocaded African fabric or pano d’obra (high cloth) could have caused a stir.8 Even though I have seen versions of the painting with the “Negro woman” cropped out, it was the expression on the black woman’s face that first intrigued me. In an almost haughty stance, with her head angled back and looking askance at the viewer, she is dressed in a simpler but still stylish version of her master’s clothes. Her head is uncovered and she wears no fabric over the shoulder; her bare feet peek out from beneath her patterned, but simple, full, flowing skirt.9

The original painting displays much more than two women of color – one wealthy and elite, the other dependent and formerly enslaved – against a nondescript background. Though the duplicated drawing circulated during a moment in the 1860s when the Republic was suppressed by dictatorship, 1848 had marked a definitive shift in claims to rights and citizenship for hundreds of thousands of Africans and Antilleans in France’s colonial holdings in the Atlantic world. The seated signare embodied a population of several hundred elite women and men, many of them of both African and European descent, living in coastal enclaves along the West African coast. For her part, the black woman standing tall with one arm akimbo could have represented thousands of free and recently freed Africans in the small French colonial settlements in Senegal, as well as the hundreds of thousands of free and freed people in the Antilles who also, theoretically, became citizens of France in one fell swoop in 1848. Those stories, and images such as “Signare and Negro Woman,” make this history compelling because so much has been simultaneously proclaimed, assumed, and left unsaid about the meaning and practice of citizenship in France’s colonial empire.

When people of color have claimed to be French – whether in the Antillean or African colonies or in France itself – they were troublesome precisely because they often did not deny that they were African, Antillean, black, and/or a person of color. The French concept of citizenship, however, has been framed, since its origins, as universal and “colorblind.” For several decades, scholars have exposed the mythmaking behind the ideal of a French nation and empire devoid of race and racism, recognizing what many people of color had been experiencing in their daily lives as the enslaved, as colonial subjects, and as second-class citizens. Still, the ways in which so many women and men of color embraced their complex racial, local, and ethnic identities revealed how local dynamics and global forces, deeply imbued with race and gender, profoundly shaped the interpretation of the concept of French citizenship in France and its empire.10

Thus, in those moments when people of color claimed to be French, they often implied or declared outright that they were French and something more – rather than French, but something else. Because “Signare and Negress” was probably originally created in Paris in the heat of the 1848 Revolution, I read the image as a representation of what it could mean to be “French and more.” A century earlier, documents and activities by free and enslaved women in places such as Saint-Louis and neighboring Gorée island reveal that elite local women and men living there had very different ideas about how they were part of a community and a larger French empire. Yet in 1848, neither woman, regardless of their different status and wealth, could have legally claimed much in terms of political rights in 1848 or 1849, beyond customary rights or basic freedom from enslavement. The year 1848 marked a shift, but questions about citizenship, belonging, and freedom for people of color remained unanswered.

For lack of a better term, I generally use the phrase “people of color” to describe Africans and all orders of people of African descent from the period of the eighteenth to twentieth centuries covered in this book. At times, I may also use the modern French term “métis” for people of African and European descent, although it is not a neutral descriptor given its history among Native American populations in Canada and in colonial and present-day understandings. The idea of the métis or the process of métissage (mixing, specifically “race-mixing”) conjures a troubled history of racial categorization, sexual violence, and abandoned children in the history of slavery and colonialism.11 At the same time, when used in the present, the reference to a person as “métis” could either be a sign of denigration or a celebration of idealistic notions about a postracial society. Literary scholar Valérie Loichot remarks that still in the twenty-first century, “[m]étissage in the French imaginary … represents love and hate, fear and desire, lust and disgust.”12 My use of all of these terms of racial designation is deeply fraught. Similarly, the phrase “people of color” is not a simple descriptive term or a straightforward translation of gens de couleur, a term used to describe people of African, European, and/or Native American descent in the Antilles and Latin America. Even as a form of self-identification, the term gens de couleur was deeply implicated in the racist ideology of the times. “People of color” may roll off the tongue or onto the page fairly easily because in the twenty-first century usage, many use the term “people of color” to capture a whole range of people descended from indigenous populations from Africa, Asia, and the Americas. I have no choice but to use a dated term with problematic modern sensibilities in mind.

Nevertheless, I will never use “colored” or “free coloreds” as shorthand for people of color because of the history of the term “colored” in the United States to designate African Americans, often in the depths of the segregationist Jim Crow era. There is a similar loss in the translation of the French term mulâtre, which in Haiti, in particular, has acquired a redolent and much more layered meaning that incorporates notions of class and education. The famous saying, “The rich black who can read and write is a mulâtre; the poor mulâtre who can’t read or write is black,” may be overwrought because black people did not simply “become” mulâtre with wealth and success.13 Historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot described color as a “commodity in the game of inter and intraclass alliances.”14 While I use the term mulâtre in the historical context, especially when it was the prevailing term, I will not use the English translation “mulatto” in this book unless it is in quotes. This choice is not only because of the negative, racist connotations behind the word in the United States. The term is not only offensive simply because it is derived from the word for “mule,” but also because a mule is the result of crossbreeding a female horse and a male donkey, making the mule sterile. Alternate racist theories about the sterility, superiority, degeneracy, and “tragedy” of the “mulatto” surfaced in different forms in medical, anthropological, social, and popular culture theories after the term had been in use, showing how much those ideologies reflected cultural and political change. Nevertheless, the idea of the “mulatto” is a profound reflection of the anxieties and violence around race, sexuality, and babies born of black women’s bodies in slave-holding societies.15

The struggle over words masks a deeper question of rights, just as the image of the signare and her servant obscures the politics of citizenship in 1848. No matter what terms are used, people of African descent continue to struggle to enjoy full privileges and protections of citizenship in the places they call home. To push on that ongoing exclusion of people of color from the full rights of citizenship in so many places, I purposefully refer to just “citizenship” and “citizens” in the title of the book, and the titles of the prologue and epilogue. After all, this book seeks to show that the story of the struggle for citizenship for people of color is a universal one.

Contours of the Book

My prologue begins with the image of the “Signare and the Negro Woman” because of the subtle connections that the portrait makes to the main themes explored in the rest of the book: legal debates, gender dynamics, and the impact of urban landscapes on the history of citizenship during French colonial empire. It matters that the original painting was created during a historical moment that complicated legal questions when some formerly enslaved men and free men of color in France’s colonies technically became full citizens. Each chapter of this book revolves around a core legal document, series of texts, or political moment that reflects specific debates around citizenship. Gender is considered as an integral part of debates over citizenship in these urban landscapes. For example, the French emancipation decree of 1848 legally turned the enslaved into citizens, but no women anywhere in France’s empire, not even white ones in France, would be able to claim full citizenship rights until a century later. Still, in this book, gender informs the nature of citizenship beyond questions of women’s right to vote by examining gender in a range of power relationships and gendered metaphors. Finally, although the portrait provides no context for where it was painted, the self-fashioning of the signare and her servant reflected their connections to urban lifestyles and environments in western Africa, Europe, and the Antilles. Flashpoints and crises over citizenship occurred in ports and cities, significant for their location, populations, and singular as well as interconnected histories.

My book engages shifting ideas in the study of French empire and transnationalism while challenging some of the persistent trends in the growing body of literature on the intersection of citizenship, race, and French empire. Two approaches dominate in the theme of race and French empire. First, many scholars focus on the most elite political activists and writers and their struggle to reconcile their simultaneous deep engagement with and critique of France.16 The central phrase in the title of my book – “free and French” – does draw from one of the best-known black historical figures of all time, Haitian revolutionary Toussaint Louverture, and the ultimate form of political writing, his 1801 Constitution. Louverture’s 1801 Constitution also sought to maintain Saint-Domingue as a French colony, with its own laws and with citizens who were “free and French.” This book then explores what it has meant to be free and French more broadly, from the perspective of a wider range of enslaved, free, elite, and working women and men of color. Studies of French empire also often either take a perspective from metropolitan France or a main location in Africa or the Americas. Such a tactic often privileges European or American sites more than African ones.17 Women and men of color were mobile, either through coercion or their own volition, affected by their travel between France and its empire and among its colonies in different corners of the globe. In turn, this movement around the French empire shaped the production of ideas about rights and citizenship among women and men of African descent.18

Given how people of color have been mobile and have claimed rights despite their limited access to citizenship, the concept of transnationalism easily comes to mind. Transnationalism implies an identity grounded in one place with real or imagined links to another location or homeland. Theorists have warned for some time about facile uses of transnationalism as shorthand for migration, diaspora, international, or cultural difference. Such approaches flatten the complex contexts and circumstances that have forced the movement of people, products, and capital between different parts of the world at specific moments in history.19 In the process of homogenizing transnationalism, migration and travel often becomes universal and romanticized as a site of privilege for people in the Western world. Meanwhile, people of color only seem to travel the world as the enslaved, as refugees, or illegal immigrants, perennially in-between, and devoid of full nationality and citizenship. When people of color claim such complex nationalities or transnational identities, it is often portrayed less as a positive sign of privilege than as “unbelonging,” particularly in postcolonial literature.20 Yet, even if they did not use the phrase, people of color on the move conjured the possibility of themselves as “citizens of the world.”21

As a result, scholars have proposed other terms to try to capture the unique nature of the experiences of people of color in the Atlantic. For example, Ifeoma Nwankwo has written of black cosmopolitanism, and Mamadou Diouf has described vernacular cosmopolitanism. Scholars of the Indian Ocean pose other models of transoceanic exchange in the form of an Indian Ocean public sphere.22 In each of these models, authors try to capture globalized identities of people of color who have been, at once, rooted in a region and time yet connected to a much wider world. Despite often being denied recognition as citizens, people of color often struggle to obtain legal rights locally, while remaining aware of the shared circumstances and struggles of other people of color.

Africans and people of African descent have not only long been in motion across oceans and deserts, they have also reflected upon the nature of their own mobility. The writing of the history of Africans and people of African descent has likewise long incorporated this “global vision.”23 My book grapples with activism, migration, and intellectual work related to citizenship during French empire on at least two levels. On the one hand, women and men in Africa and the Americas actively debated their rights or status in letters, petitions, or even performance. On the other, women and men of color, sometimes only by the grace of their mere presence or activity – on city streets, plantations, or at momentous historical events – provoked anxiety about definitions of empire, citizen, gender, and nation within the history of France and a wider world.

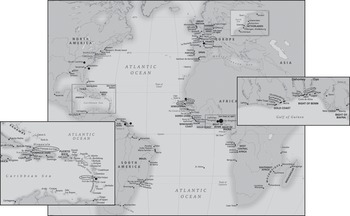

Map P.1: French Atlantic World, 18th–20th centuries

Map of the French Atlantic world with all the ports and cities discussed in detail in the book as well as secondary locations mentioned in the text. Primary locations analyzed in detail are circled: Le Cap, Saint-Domingue; Gorée, Senegal; Saint-Pierre, Martinique; Porto-Novo, Dahomey; Paris, France; Dakar, Senegal.

Marked secondary locations within French Atlantic and beyond it include: Charleston, South Carolina; Saint-Louis, Senegal; Cayenne, French Guiana; Fort-de-France, Martinique; Bordeaux, France; Dahomey kingdom; Oyo kingdom. Base map courtesy of Yale University Press.

Rather than a basic chapter outline, the rest of this prologue reflects upon how legal history, gender, and urban studies bind the places and historical figures featured in each chapter into an overarching narrative. The book is divided into three parts that underscore an urban studies theme by evoking the ideas of foundations, construction, and planning. At the same time, intertwined in each of these building metaphors are concepts related to political transformation and identity formation among individuals as well as in the French nation and empire. The chapters roughly follow a chronology from the turn of the nineteenth century through the early independence era in the 1960s, covering the colonial port cities of Gorée, Senegal; Le Cap, Saint-Domingue; Saint-Pierre, Martinique; Porto-Novo, Benin; as well as Paris, France, and Dakar, Senegal, after independence. At the same time, the historical context covered often moves back and forth in time, pauses, and accelerates – as does the physical movement of the people whose stories are highlighted.

Citizenship as Variations on a Theme

Across France’s Atlantic empire, citizenship emerged as a salient theme during pivotal moments in French history: the French Revolution, the July Monarchy, the 1848 Revolution, and World War II. But these events looked different when viewed from urbanized outposts at the edges of empire. Similarly, citizenship, as a concept and as a practice, had to operate differently in a colonial context, especially as Africans and Antilleans tried to shape its meaning in new ways. Often there were key texts that were either new innovations or variations on a theme of rights and citizenship. Still, meanings of citizenship varied because citizenship involved more than legal codes. Each chapter also explains how the culture, experience, and interpretation of citizenship had an even more profound impact on people of color, women, and/or colonial subjects, who were often excluded or on the edges of legal status.

For example, in the heat of the French and Haitian Revolutions, Toussaint Louverture’s 1801 Constitution sought to rebuild Saint-Domingue (Haiti) as part of the French empire, based on the ideals of “purity,” family, and rural labor that allowed people of color and the poor to access citizenship but only in certain ways. In Gorée, the adoption of the French Civil Code in 1830 revealed locally contested visions of rights in the French empire that had been built upon eighteenth-century activities, letters, and petitions by wealthy women and men of color, concerned with their own position in society. If the rhetoric of belonging, particularly as deployed by the wealthy women known as signares, provided a basis for citizenship rights in Senegal after 1848, the majority of the population – the free African women and the recently freed enslaved women – were excluded. Indeed, in so many cases, the notion of being “free,” even during a moment of revolution and upheaval, often came with contingencies.

The year 1848 is remembered for the emancipation of slaves in the French empire, but in Saint-Pierre, Martinique, enslaved women and men staged protests that forced the declaration of their freedom before an official decree arrived. That particular protest seemed to have been seething at least from the 1820s and 1830s, when the port city had been the site of a petition scandal involving free men of color and uprisings by the enslaved population. However, when people in Martinique technically became “French” in 1848, they still found themselves saddled with a second-class citizenship.

In the 1890s, most Africans living in the rest of France’s West African colonies became colonial subjects without any rights at all. Porto-Novo was a diverse African kingdom, with Muslims, returned Brazilians, and Catholics, that the French transformed into the colonial capital of Dahomey. During the 1910s and 1920s, Porto-Novo newspapers and petitions reflected local concerns but mirrored events in interwar Paris where Africans, such as Dahomean subject-turned-citizen Marc Kojo Tovalou Houénou, similarly engaged in activism. In 1924, Houénou decried French colonialism and argued for French citizenship for all Africans, demanding: “Absolute autonomy for the colonies or complete assimilation … without any distinction of race.” Houénou’s professed loyalty to his “French motherland” has been misunderstood as a desire to erase “blackness.” For Houénou and many others, to be black and French was not a paradox.

Meanwhile, Paris was becoming home to more students and veterans of color and, after 1946, some became representatives as France transformed its empire into the French Union. But African and Antillean politicians, some of them women, struggled to protect the rights of laborers, women, and veterans as they debated and argued over provisions of the 1946 Constitution and later laws of the French Union. In each of these cases, as varied as they were, women and men of color often suggested that they could be French and something more at the same time, redefining the meanings of citizenship in relation to their local circumstances and a wider world.

Engendering Citizenship Anew

If it has been challenging to theorize how race intersected with ideas of French citizenship over time, the study of gender has also been difficult to incorporate across empire. Gender informed these debates over citizenship beyond the common ways in which we chronicle lives of women or describe men in terms of their masculinities. The question is how to infuse gender into our understandings of citizenship as a legal framework and life experience. In their introduction to an important volume on transnationalism and the African diaspora, scholars Tina Campt and Deborah Thomas discuss the framing of the African diaspora as a masculine space based on travel and migration and argue that feminist theory can illuminate the study of transnationalism and the diaspora even if the subject is neither women nor gender.24 I would argue that not only can we reimagine migration and transnationalism as gendered processes, both feminized and masculinized, but that neither women nor masculinity need to be the main theme of gender analysis.

Each of my chapters proposes a way to frame these questions of empire and citizenship in ways that reflect how gender operated in the local society during the pertinent time period. One by one, the chapters build upon each other to present a multi-faceted sense of citizenship during colonial empire. Beginning with the first chapter on Le Cap, Saint-Domingue, I outline the idea of a “revolutionary citizenship” that, at its core, was racialized and gendered, even as these central principles were denied by framers of citizenship in France and Saint-Domingue. As the story continues in Gorée, Senegal, the gendered aspect of citizenship relates to more than the prevalence of women as wealthy and influential interlocutors. Their political work revealed how much claiming rights related to definition of a “cultural citizenship,” especially in the absence of laws that defined or safeguarded rights. Still, the most creative theoretical framing comes in chapters that analyze gender on a range of symbolic levels.

For example, because of the historical and symbolic importance of Carnival celebrations in Saint-Pierre, Martinique, often celebrated as the “Little Paris of the Antilles,” I use the term “carnivalesque” as a metaphor to discuss citizenship as elusive and as an inversion. Saint-Pierre also was often exoticized and feminized as a place by visitors, who often obscured the reality that this “Little Paris” was a space physically dominated by enslaved and free people of color, making it more of a “Black Paris of the Antilles” (Chapter 3). Similarly, Chapter 4, on Porto-Novo, Dahomey, begins from the perspective of the unique, cosmopolitan history of Porto-Novo before and after the beginning of French colonial rule. What I refer to as the “trans-African” nature of Porto-Novo incorporates local understanding of identity and belonging, including gendered kinship and familial networks, as a central feature of any definition of citizenship.

In a very different context, in my fifth chapter on interwar Paris, I discuss the limited nature of specific citizenship laws that applied to West Africa from the 1910s to the 1930s. West African colonial subjects were deemed French nationals without any citizenship rights, similar to French women in the metropole. When a small percentage of Africans and their families did obtain the “quality of French citizen,” I argue that they remained “unnatural” citizens.25 Yet, after the war, in the formation of the French Union, when African and Antillean politicians argued for complex understanding of citizenship rights as both equal and equivalent, they evoked what some scholars have found to be a common French feminist formulation of “equality in difference.” Dating at least to the nineteenth century, “equality in difference” arguments exposed the limits of gender equality in a sexist society, but also ran the risk of essentializing femininity and womanhood.26 By trying to emphasize equivalence, not difference, alongside equality, African and Antillean politicians tried to free themselves and their constituents from a tight, if not impossible “double bind.” Finally, if this prologue establishes that French citizenship always reflected a certain internationalist and gendered outlook, the epilogue then suggests the continued importance of such a dynamic as Africans and Antilleans continued to navigate the politics of citizenship in the immediate aftermath of empire during the 1966 First World Festival of the Negro Arts in Dakar, Senegal.

Trans-African Cities

In addition to taking race and gender seriously as themes in the study of citizenship, the chapters of this book take location as the organizing principle and point of departure. The highlighted events occurred in urbanized outposts of empire that served as homelands and as destinations for colonial subjects and citizens. With the exception of the chapters focusing on Paris, the others examine the landscape of port cities in France’s empire on both sides of the Atlantic.27 Unlike most recent studies, which focus on the urban Atlantic solely either in the period of the Atlantic slave trade or in the postcolonial era of megacities, this book not only spans the colonial and postcolonial era on both sides of the Atlantic, it also recognizes how people lived and imagined connections between different urbanized towns and cities.28

The very topography of each location covered in this book also reflected the specific culture, economics, and politics of space that shaped interactions among people of color, whites, women, and men. For example, in eighteenth-century Le Cap, the wealth of the city, with its grid of elegant stone buildings, contrasted with the deprivation in the surrounding hills, where thousands of slaves toiled on plantations. During the same time period, on Gorée, the lines between people of color, Europeans, slaves, and free looked different because spacious homes owned by African and mixed-race women and men sat beside French government buildings and the enslaved lived within these compounds and homes. Nineteenth-century Saint-Pierre, cultural capital of Martinique, was also a slave-holding society, but it operated differently from Le Cap or Gorée. Referred to as the “Little Paris of the Antilles,” Saint-Pierre was known for its steep paved streets, overflowing fresh mountain-water fountains, and its Carnival festivals. The annual celebrations captured the shared culture and racial divisions that culminated in raucous parades in which the whole city – black, people of color, enslaved, white, women, children, and men – participated. In each of these landscapes and spaces where enslaved and free people of color lived, toiled, and played, there was the potential to create what Stephanie Camp referred to as a “rival geography” often “set in motion” that challenged the demands of whites and elites who owned enslaved people or who sought to control people of color in general.29

The situation in the new colonies in Africa in the twentieth century was yet another story. In a diverse kingdom such as Porto-Novo, Dahomey, which became a colonial capital, the layout of the city reflected layers of history. Older parts of the kingdom hugged the lagoon, with serpentine alleys connecting different quarters, while the French part of the colonial capital lay on its outskirts, with some government buildings superimposed on the neighborhoods where returned Brazilians had built homes half a century earlier. In fact, the French section of Porto-Novo took its inspiration from the wide boulevards that cut across Paris after that city was rebuilt during the nineteenth century.

Meanwhile, neighborhoods such as Montparnasse, in addition to the Latin Quarter and Montmartre, in Paris became home to African and Antillean students and soldiers who came to the capital in larger numbers, beginning in World War I. Echoing the processes of adaptation that occurred in colonies across the French empire, Africans and Antilleans left an imprint, however faint on the culture and politics in different corners of the French capital. After World War II, when France transformed its colonial empire into the French Union, some of those students and veterans returned to Paris as politicians, taking their ideas and activism into the National Assembly itself.

When the First World Festival of the Negro Arts took place in 1966 in Dakar, a number of those same political leaders and artists descended on the capital of independent Senegal, with its modernist architecture circled by a winding coastline. During the day, people fanned out into neighborhoods, stadiums, theaters, and museums to attend performances and exhibits. At night, some traveled by ferry across the bay to watch a production about Gorée’s past. The play depicted Gorée’s history as it unfolded on the streets of the island and in relation to world events – all set to a spectacular sound and light show.

The intellectual, physical, and artistic activism of Africans and Antilleans played out differently in these contexts because environment alone cannot explain why slave rebellion erupted in one setting while letter-writing campaigns prevailed in another. In each of these places, interactions between African, European, and women and men of color ranged from profound violence to detached indifference to intimacy, sometimes simultaneously. Ideas about citizenship always have been as local as they have been shared, globalized conversations.

* * *

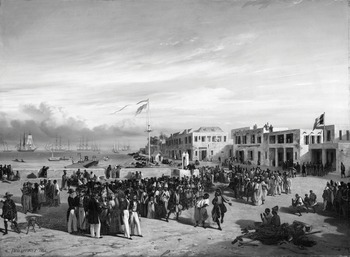

The painting that graces the cover of this book and appears below was also completed by Nousveaux while he was in Gorée in the early 1840s, and it also represents another local manifestation of a grander historical moment.30 The image depicts a festival in Gorée to mark the 1842 visit by the French Prince Joinville of Orleans on this way to Brazil to marry the Princess Francisca. Standing in the foreground with the French officials are likely Annacolas Pépin and her daughter Mary de Saint-Jean. Local historian Jean-Luc Angrand argues that Pépin was a key actor among the wealthy merchant men in Gorée who were sensing the growing importance of Dakar across the bay and had begun agitating for economic development opportunities for Gorée. 31 While the painting demonstrates the power and influence of mulâtre signares and men, near the dance at the center of the painting are many African signares, Muslim men, more mulâtre signares, perhaps some French officials or sailors, enslaved people, African leaders, as well as an array of people engaged with and indifferent to the display. Rather than tell a straightforward story of mulâtre dominance, Africans and women dominate the human landscape while architecture, ships in the distance, and flags waving overhead tell the story of French trading post. The politics at stake may be more obvious in this historical painting of the Prince’s visit but the extent of the power of signares in the eighteenth century and the continued forms of their influence in the nineteenth century could still be lost on the viewer. Moreover, once the final revolutionary push came in 1848, wealthy signares would find themselves more behind the scenes politically, not because they were people of color, but because they were women, devoid of political rights in the new French Republic.

Figure P.2: Edouard Nousveaux, “Le Prince de Joinville se rendant au Brésil assiste à une danse indigène sur la Place du Gouvernement à l’île de Gorée en décembre 1842,” 1846. (The Prince of Joinville on his way to Brazil attends a dance on Gorée Island)

Even if scholars dispute the identity of the signares and other dignitaries standing closest to the French prince in the foreground of the painting, the entire scene depicts a complex community in Gorée, composed of free people of color and free Africans of high social standing. The dress of some of the people in the image suggest that different members of the community practiced Islam, Christianity, and likely forms of indigenous religion, all in the shadow of the French flag flying above.

That interplay between the local and the global also brings back to mind the image of “Signare and Negro Woman from Saint-Louis in Full Dress” because I have taken a small intimate moment and interpreted it with broader historical and political meaning. But what could the women have been thinking as they posed for Nousveaux? The casual yet direct gaze of both women toward the viewer may be interpreted as eroticizing and as empowering to the male gaze of the readers of the journal where the image was reproduced. bell hooks’ theory of the “oppositional gaze” offers another interpretation. People of color sometimes stared in defiance of the colonial, the slave-owner, or the man who commanded them not to look.32 The simultaneous flirtatious and daring gaze of both women also made them appear connected, though they remained separated by status. That tension, perhaps, reflected the long, unspoken history of intertwined African and free communities of color in a small yet urbanized place such as Gorée.

At the same time, “Signare and Negro Woman” tells nothing of the profound political upheaval of the period. Instead, the viewer of the portrait is lured to the light-drenched face of the signare whose body is drawn as the epitome of femininity, with impossibly small, dainty hands and weighed down with layers of sumptuous fabric and jewels. But who insisted that the black woman appear in the picture? Was she supposed to be a further “adornment” for the unidentified signare? The woman standing tall was no young, fawning enslaved girl popular in other images and descriptions of signares. Instead, the unnamed black woman (who, for me, stole the show) opened up a series of questions about the complex power dynamics related to the culture and politics of citizenship in this world, where women like them could live and travel, together. Even with an opening portrait hinting at how free and freed women of color moved around the Atlantic during momentous historical moments, people of color remained vulnerable to violence and assaults on their rights, bodies, and spirit. Many still found ways to make a new home, take on a new name, and seek to belong to a new nation.