Objects recovered across the territory of modern Honduras (Figure 1) from the nineteenth century to the present have been described by art historians and archaeologists as having been executed in “Olmec style.” Such objects present archaeologists concerned with understanding changing social relations over time and who cannot be satisfied with simply mapping the presence and absence of unitary “cultures” or “styles” with a problem: what might “Olmec”-style objects mean in Honduras?

Figure 1. Location of Formative period Honduran archaeological sites.

Explanations entertained for stylistic and material identities between sites in the Gulf Coast of Mexico and those of the Mexican highlands or Pacific Coast, such as ethnic identity, political domination, or military control, are problematic for Honduran objects described as “Olmec-style,” which were made and used in villages much more distant from any of these other regions. We agree with Grove (Reference Grove, Sharer and Grove1989, Reference Grove1997) on the need to differentiate multiple uses of the term “Olmec.” Most references to the “Olmec” character of objects from Honduras simply link these things through form and iconography to a broadly distributed set of symbolic images that are not uniform across space, rarely considering local contexts of production and use. We argue that such innovative material practices, including use of similar canons of representation and new preferences for vessel forms, finishes, and decoration, raise questions that must first be answered in terms of local experience, local meaning, and local practices. In places with long histories of material exchange and the social relations they imply, like Mesoamerica, local practices always take place with reference to more cosmopolitan places, practices, and experiences. Our purpose here is not to attempt another redefinition of “Olmec” or to propose an alternative term. Rather, we want to explore the precisely situated local understanding of things in Formative period Honduras that were stylistically distinct from what had gone before, things marked in ways that can be related to other places more easily than to local histories, as a model for thinking about chains of similarities elsewhere in Mesoamerica.

What did it mean to the inhabitants of Formative period sites to make and use objects whose stylistic features would have made their users stand out locally as different while simultaneously connecting people in different areas? Were such locally distinctive objects viewed as evidence of “exotic” or foreign identity or just difference within the locality? In other words, were Formative period Hondurans trying to “be Olmec”? And what could “being Olmec” have meant to them?

THE HONDURAN FORMATIVE: PUERTO ESCONDIDO AND ITS CONTEMPORARIES

Formative period materials were among the earliest archaeological remains reported in Honduras (Gordon Reference Gordon1898a, Reference Gordon1898b). Very specific resemblances were identified between pottery in caves near Copan and at the Playa de los Muertos site on the Ulua River and sites in Mexico, especially Tlatilco (Longyear Reference Longyear1969; Porter Reference Porter1953). Originally, scholars assumed the Honduran sites were contemporary with these Mexican sites (Canby Reference Canby and Tax1951; Vaillant Reference Vaillant1934). With the definition of Olmec as Mesoamerica's first great art style, developed in the major centers of the Gulf Coast of Mexico, this interpretation changed. Honduran objects were viewed as products of delayed incorporation of a periphery into Mesoamerica, and pottery with Olmec-related motifs was assigned later dates than elsewhere in Mesoamerica (Sharer Reference Sharer, Sharer and Grove1989; Willey Reference Willey1969). The first radiocarbon samples from modern archaeological research at Playa de los Muertos and Los Naranjos seemed to support such a time lag in the introduction of Olmec-derived motifs in Honduras (Baudez and Becquelin Reference Baudez and Becquelin1973; Kennedy Reference Kennedy1980, Reference Kennedy, Urban and Schortman1986).

This picture of delayed participation in broader Mesoamerican practices began to shift in the 1970s (Healy Reference Healy, Lange and Stone1984a, Reference Healy and Lange1992). First, a group of pottery vessels was collected from caves near the Río Aguan on the northeast Caribbean coast that also contained human remains (Healy Reference Healy1974, Reference Healy and Lange1984b). These vessels were recognized as closely related to pottery with Olmec-style motifs recovered from the caves of Copan a century earlier. Shortly thereafter, stratigraphic excavations at Copan recovered burials with similar pottery (Fash Reference Fash1985, Reference Fash1991; Viel and Cheek Reference Viel and Cheek1983). While citing the arguments of others for dating these vessels later than elsewhere in Mesoamerica, including the then-accepted dating of jade (found in some of these burials) after 900–800 b.c., Viel (Reference Viel1993) also noted the possibility that the Copan vessels might actually be contemporary with San Lorenzo, San Jose Mogote, and Tlatilco in Mexico.

Subsequent research in Honduras has documented Early Formative occupation at Yarumela in the Comayagua Valley (Dixon et al. Reference Dixon, Joesink-Mandeville, Hasebe, Mucio, Vincent, James and Petersen1994; Joesink-Mandeville Reference Joesink-Mandeville1986, Reference Joesink-Mandeville and Robinson1987, Reference Joesink-Mandeville, Henderson and Beaudry-Corbett1993) and in the Oloman Valley of Yoro (Joyce et al. Reference Joyce, Hendon, Sheptak and Ann Cyphers y Kenneth G. Hirth2008). Caves in eastern Olancho were used for burials, with five samples of charcoal and carbon from human bone reported as calibrated one sigma (67% probability) dates bracketing an interval from 1030 to 515 cal b.c., with one additional sample reported as 1400 cal b.c. (Brady et al. Reference Brady, Begley, Fogarty, Stierman, Luke and Scott2001).

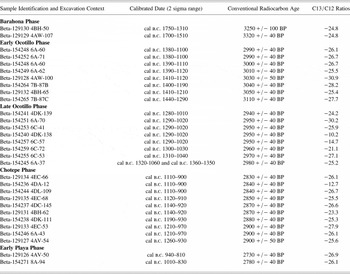

The most extensive excavations of sites in Honduras with Early Formative period features have been those we have codirected, first at the site of Puerto Escondido in the lower Ulua River valley (Henderson and Joyce Reference Henderson and Joyce1998, Reference Henderson and Joyce2004; Henderson et al. Reference Henderson, Joyce, Hall, Hurst and McGovern2007; Joyce Reference Joyce2004; Joyce and Henderson Reference Joyce and Henderson2001, Reference Joyce and Henderson2002, Reference Joyce, Henderson, Laporte, Arroyo and Hector Escobedo y Hector Mejía2003, Reference Joyce and Henderson2007; Joyce et al. Reference Joyce, Shackley, Sheptak and McCandless2004) and more recently at Los Naranjos, on Lake Yojoa (Henderson and Joyce Reference Henderson and Joyce2003; Tchakirides et al. Reference Tchakirides, Brown, Henderson and Blaisdell-Sloan2006). The radiocarbon record from Puerto Escondido, based on 42 samples analyzed to date, includes 30 samples spanning the Early Formative and initial Middle Formative periods (Table 1). The deepest, aceramic levels at the site were likely late Archaic. They precede the formation of sediments in which we recovered our earliest examples of pottery, deposits for which two radiocarbon samples support dates of 1750–1310 cal b.c. at the 2 sigma range. It is possible, as is the case elsewhere in Mesoamerica (Clark and Cheetham Reference Clark, Cheetham and Parkinson2002), that there is a discontinuity in cultural identity between the Archaic- and initial Formative-period inhabitants of the site. It is clear that occupation at Puerto Escondido did not lag behind historical developments elsewhere in Mesoamerica. The same is true of Los Naranjos: pollen from cores in Lake Yojoa suggests that inhabitants of the lakeshore were cultivating corn by the end of the Archaic period (Rue Reference Rue1989).

Table 1. Early and Middle Formative period radiocarbon dates from Puerto Escondido

Note: All samples are wood charcoal. Beta Analytic calendar calibrations calculated with calibration data published in Radiocarbon, Vol. 40 (1998), using the cubic spline fit mathematics published by Talma and Vogel (1993).

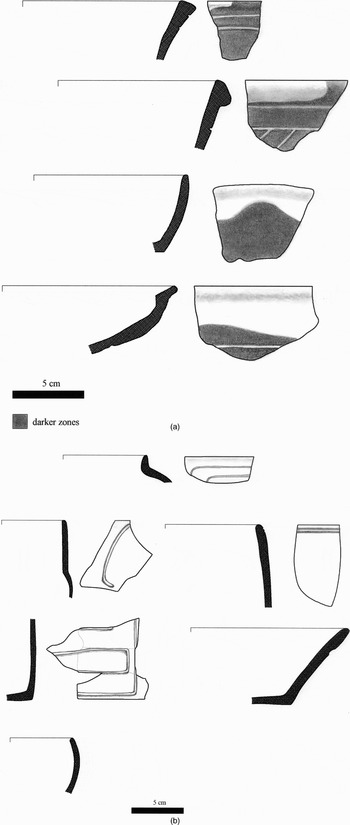

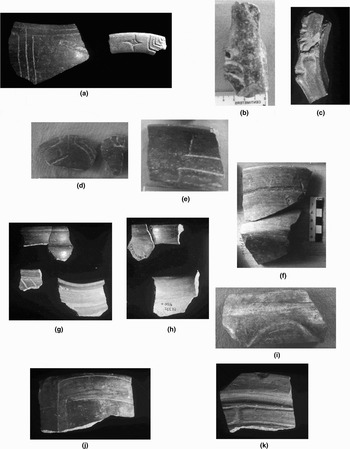

At Puerto Escondido, the first appearance of material culture with features that would elsewhere be identified as Olmec occurs during the Chotepe phase (Figures 2, 3). Radiocarbon results from 10 stratified samples of carbon from sediments in which Chotepe-phase diagnostics were recovered span a period from 1260–900 cal b.c. at the 2 sigma range. The diagnostic features of the Chotepe phase are comparable to those of the San Lorenzo, San Jose, and Cuadros phases (Blake et al. Reference Michael, Clark, Voorhies, Michaels, Love, Pye, Demarest and Arroyo1995; Coe and Diehl Reference Coe and Diehl1980; Flannery and Marcus Reference Flannery and Marcus1994), conventionally presented in uncalibrated date ranges (e.g., 1100–900 b.c.), and we have followed this lead in assigning conventional dates to the Chotepe phase while noting that in real calendrical years, the occupation of all these sites was earlier than these conventional phase dates would indicate, and all were approximate contemporaries.

Figure 2. Chotepe phase ceramics from Puerto Escondido: (a) Sukah Differentially Fired type. (b) Fía Gray type.

Figure 3. Photographs of sherds of Boliche Black, Fía Grey, and Bonilla Yellow-Brown vessels showing location of incised and carved motifs. All rim sherds unless noted: (a) Boliche Black (left) and Fía Gray (right) vessels with St. Andrew's cross (left) and star with hand-paw-wing (right); (b) Fía Grey and (c) Boliche Black rim sherds with modeled “Olmec” faces; (d) Boliche Black body sherds with corners of zoomorphic profile faces; (e) Boliche Black bowl with U-brackets; (f) Flat-base, flaring-wall Boliche Black bowl segment with sublabial groove; (g) and (h) exterior and interior views of Boliche Black (upper) and Fía Grey (lower) small jars; (i) Fía Grey incurved rim bowl with modeled animal face at right; (j) Boliche Black bowl with roughened panel with traces of red post-fire pigment, comparable to the Los Naranjos type Bogran Rugose-en-Zones; (k) Fía Grey bowl with large carved design.

Stratigraphically preceding our Chotepe-phase levels are others with Ocotillo phase features. The early part of these stratigraphic levels yielded eight radiocarbon samples with a span from 1440 to 1100 cal b.c. at the 2 sigma range. Six additional radiocarbon samples from stratigraphically later deposits span the range 1300–1010 cal b.c. at the 2 sigma range. We assign the Ocotillo phase conventional dates of 1400–1100 b.c. and suggest that late Ocotillo can be profitably compared to the Chicharras phase at San Lorenzo and especially to the Cherla phase of Soconusco (Blake et al. Reference Michael, Clark, Voorhies, Michaels, Love, Pye, Demarest and Arroyo1995; Coe and Diehl Reference Coe and Diehl1980). Early Ocotillo corresponds in general to the Ocos and Locona phases of Soconusco (Blake et al. Reference Michael, Clark, Voorhies, Michaels, Love, Pye, Demarest and Arroyo1995). Ocotillo-phase contexts include material that suggests participation in networks extending to the Pacific Coast was already established long before the Chotepe phase.

Ceramics from the deepest levels we tested at Los Naranjos are comparable to those of Chotepe-phase Puerto Escondido. While our radiocarbon samples are currently being analyzed and results of chronometric dating are consequently unavailable, these levels stratigraphically precede the early phase of construction of monumental Structure IV, assigned to the Middle Formative period Jaral phase by the original excavators (Baudez and Becquelin Reference Baudez and Becquelin1973). Jaral phase at Los Naranjos corresponds to the early Playa phase at Puerto Escondido for which radiocarbon samples yielded dates spanning 1010–810 cal b.c. Radiocarbon dates for Middle Formative period Playa phase materials elsewhere in Honduras support dating the beginning of related complexes across Honduras at around 900 b.c., which we take as the beginning of the Honduran Middle Formative (Joyce Reference Joyce1992, Reference Joyce, Langebaek and Cardenas-Arroyo1996; Joyce et al. Reference Joyce, Hendon, Sheptak and Ann Cyphers y Kenneth G. Hirth2008). Our excavations at Los Naranjos, adjacent to Structure IV, thus stratigraphically indicate the existence of a preceding Early Formative occupation with ceramics incised with complex motifs that recall the techniques and designs usually interpreted as indicating some integration into wider cosmopolitan networks of communication across Mesoamerica.

At Puerto Escondido and Los Naranjos, then, we have a sequence of occupation parallel to the Olmec Gulf Coast of Mexico and especially to contemporary sites in the Mexican highlands and Pacific Coast (Blake et al. Reference Michael, Clark, Voorhies, Michaels, Love, Pye, Demarest and Arroyo1995; Coe and Diehl Reference Coe and Diehl1980; Flannery and Marcus Reference Flannery and Marcus1994; Niederberger Reference Niederberger1976). Materials related to the broader Olmec style are present at these two sites between approximately 1300–900 b.c., during the late Ocotillo and Chotepe phases, corresponding to the Chicharras and San Lorenzo phases at San Lorenzo and the Cherla and Cuadros phases of Soconusco (approximately 1100–900 b.c.).

EARLY FORMATIVE HONDURAS: PUERTO ESCONDIDO

We have elsewhere described the nature of the Puerto Escondido site and our excavations there in some detail (Henderson and Joyce Reference Henderson and Joyce1998, Reference Henderson and Joyce2004; Joyce Reference Joyce2004; Joyce and Henderson Reference Joyce and Henderson2001, Reference Joyce and Henderson2002, Reference Joyce, Henderson, Laporte, Arroyo and Hector Escobedo y Hector Mejía2003, Reference Joyce and Henderson2007). In the latest Ocotillo strata, we have evidence for in situ experimentation with new techniques of ceramic manufacture, including controlled firing, which becomes common in and is diagnostic of the succeeding Chotepe phase (Joyce and Henderson Reference Joyce, Henderson, Laporte, Arroyo and Hector Escobedo y Hector Mejía2003). Innovations in pottery body and firing were combined with new vessel forms and modes of decoration in the Chotepe phase (1100–900 b.c.).

Our original sample of Chotepe pottery came from the floor of a deliberately burned and in-filled structure, measuring 5 m by at least 9 m, with thick rammed-clay walls. New vessel forms introduced include flat-bottom, flaring-walled bowls and necked bottles (Figure 2). The surfaces were usually unslipped, fired a light tan or black or differentially fired, with designs carved into the thick walls, sometimes with post-fire red pigment rubbed into excised areas (Figure 3). A small number of vessels, similar in form and decoration, were a metallic grey in surface color; some of these showed clear evidence of a white slip that was fired to produce the gray color. A very small number of these gray vessels used various approaches to produce a bichrome painted effect.

Ceramic analysis of approximately 15,000 sherds from Early to Middle Formative stratigraphic contexts has been completed. While the precise proportions may change as we refine our ceramic and stratigraphic analyses, in the Chotepe-phase assemblage recorded to date, the bulk of the pottery recovered (67%) can be assigned to unslipped coarse ware types (Urbe Plain and its varieties). Another 7% of the pottery is represented by coarse ware types with red-slipped zones (Rubí Red and its varieties). Approximately 22% of the assemblage are sherds from differentially fired, black, yellow-brown, or gray wares (Fía Gray, Boliche Black, Bonilla Yellow-Brown, and Sukah Differentially Fired). About 5% of the sample consists of sherds that carry incised or carved iconographic motifs, found on specific areas of Fía Gray, Boliche Black, and Bonilla Yellow-Brown bowls and bottles. We attribute the high proportion of these serving vessel types in our excavated sample to the kinds of activities these deposits represent and would not assume that these types would be such a large proportion of everyday assemblages. At the same time, however, in the Chotepe deposits we excavated, all serving vessel sherds consisted of these types; they entirely replace previously common brown paste bowls and bottles.

The newly employed modes—flat bottom, flaring- or cylindrical-wall bowls; surfaces in tones of gray and black produced by control of firing atmosphere, including contrasting dark and light zones; and carved and incised complex motifs large enough for one or two to cover the vessel; and specific motifs, including the hand-paw-wing, U-brackets, and the St. Andrew's cross—are among the features that have long been identified as “Olmec” in Honduras. Chotepe-phase ceramics from Puerto Escondido have recognizable precedents in Honduran excavations as early as the 1890s. Vessels collected in caves in the Copan Valley in the late nineteenth century and from the Cuyamel caves in the 1970s share the same range of shapes and repertoire of incised designs. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the type Bogran Rugose-en-Zones was defined at Los Naranjos based on sherds from similar vessels, recovered in platform fill, explicitly compared to Copan caves vessels (Baudez and Becquelin Reference Baudez and Becquelin1973:147–150). Healy (Reference Healy1974:440–441) identified a black incised cylinder from the Cuyamel caves with the previously recovered vessels from Copan as well. Later excavations near the center of Copan augmented the original sample, reaching a total of 27 complete vessels and 23 sherds, 7 of them diagnostic, assigned to the Gordon complex (Viel Reference Viel1993:33–41, 132–133). The forms and surface treatments of these Honduran vessels are similar to those at other contemporary sites elsewhere in Mesoamerica, especially, as has long been noted for Honduras, sites in highland central Mexico, such as Tlatilco (Porter Reference Porter1953). What has remained difficult to explain is why the local production in Honduras of numerous vessels with this suite of characteristics ever occurred and what their use in such events as household burials and house remodeling might have meant. The recovery of substantial deposits of Chotepe-phase ceramics in stratigraphic contexts at Puerto Escondido allows us to begin to answer these questions.

Other materials recovered at Puerto Escondido suggest that Chotepe phase people had significant wealth that they were willing to dispose of in contexts like the dense ceramic deposit we initially recovered. A number of worked or partially worked objects of marine shell, including conch, show that residents of this area of the site were making and using shell ornaments. Sherds from carved stone vessels, including the earliest example of the use of marble, were also part of this assemblage (Luke et al. Reference Luke, Joyce, Henderson, Tykot and Lazzarini2003). While the majority of obsidian flakes were made of material from regional sources in northern Honduras, obsidian from the Ixtepeque and El Chayal sources in Guatemala was present, used for blades more than flakes, in contrast with obsidian from sources closer to the site, which was used predominantly for flakes (Joyce et al. Reference Joyce, Shackley, Sheptak and McCandless2004). The range of exotic materials present and the kinds of objects for which they were used, including serving vessels, body ornaments, and tools, would have provided substantial opportunities for some residents of the site to distinguish themselves in everyday material practices.

Excavations in a second area at Puerto Escondido produced a parallel sequence of occupation. Chotepe deposits in this second area also included worked shell and carved and incised serving vessels. While these two areas had similarly diverse assemblages with exotic materials present in each, a third area sampled showed much less evidence of use of the distinctive incised pottery or exotic materials. Thus, our current understanding of Puerto Escondido during the Chotepe period is that it was a village with some neighborhoods that were capable of mobilizing greater resources and that were interested in using them in display while other neighborhoods had less interest in or ability to do the same.

Construction projects around 900 b.c. covered Chotepe phase houses with broad earthen platforms and, in one area, stone features. These new architectural projects coincided with other innovations, including the use of jade and the creation of large-scale stone sculpture, that suggest changes in social relations were taking place at the site (Joyce Reference Joyce1992, Reference Joyce2004, Reference Joyce and Beck2007a; Joyce and Henderson Reference Joyce and Henderson2002, Reference Joyce, Henderson, Laporte, Arroyo and Hector Escobedo y Hector Mejía2003, Reference Joyce and Henderson2006; Joyce et al. Reference Joyce, Hendon, Sheptak and Ann Cyphers y Kenneth G. Hirth2008). Early Middle Formative residents of these and other Honduran sites, such as Playa de los Muertos, participated in practices widespread over Mesoamerica. But this was not the beginning of such participation: innovations in ceramics that took place before 900 b.c., once described as delayed reflections of earlier developments in Mexico, are now clearly demonstrated to be contemporary with use of similar ceramics in Soconusco, highland Mexico, and the Gulf Coast. These earlier ceramics have been the center of debate about Honduran sites’ relations with the Gulf Coast Olmec and their contemporaries in Mexico (Longyear Reference Longyear1969; Porter Reference Porter1953; Willey Reference Willey1969). They are the objects that archaeologists and art historians have been most willing to call “Olmec,” and they thus raise the question, “What is ‘Olmec’ in Honduras?”

WHAT IS “OLMEC” IN HONDURAS?

The range of materials in Early and Middle Formative Honduras that suggest connections with a broader “Olmec” style is as extensive as anywhere in Mesoamerica, including the Gulf Coast of Mexico, even if the sample size recovered to date is smaller. Flat-bottom, flaring-wall bowls and bottles in differentially fired, black, or light tan fabrics, with excised designs often rubbed with post-fire red pigment, accompanied burials at Copan, in the caves of Copan, and in the caves of Cuyamel. Sherds from similar vessels have been recovered at Puerto Escondido and Los Naranjos. Other distinctive ceramic artifacts, while rarer, are part of the same assemblages. They include hollow and solid figurines (Figure 4) from Puerto Escondido and the Cuyamel Caves (Healy Reference Healy1974:Figure 4a–d; Henderson Reference Henderson, Eggebrecht, Eggebrecht and Grube1992; Joyce Reference Joyce2003, Reference Joyce, Renfrew and Morley2007b, Reference Joyce, Robb and Boric2008b), roller seals and stamps (Figure 5) from multiple sites including Puerto Escondido (Bachand Reference Bachand, Laporte, Arroyo, Escobedo and Mejía2003, Reference Bachand2005), and a unique pendant in the form of a clamshell (Figure 6) from Puerto Escondido (Joyce and Henderson Reference Joyce and Henderson2001). We need to understand their local contexts of use to interpret these objects. Those local contexts were, without exception, practices that took place at the face-to-face level within villages during marked events in the life course of people and houses.

Figure 4. Hollow figurine from the Ulua Valley, representing the type from which Chotepe phase fragments recovered at Puerto Escondido were derived.

Figure 5. Chotepe phase stamps from Puerto Escondido.

Figure 6. Ceramic pendant in the form of a clam shell from Puerto Escondido. Drawing by Yolanda Tovar.

Motifs produced with cylinder seals and stamps would have been incorporated as impermanent body ornamentation on the skin of people living in some Honduran villages (Bachand Reference Bachand, Laporte, Arroyo, Escobedo and Mejía2003, Reference Bachand2005). Examples excavated at Puerto Escondido (Figure 5) securely date stratigraphically to the Early Formative Chotepe phase. Motifs on seals from sites in the Ulua valley include close matches to examples from the central highlands of Mexico, especially Tlatilco (Bachand Reference Bachand2005; compare Porter Reference Porter1953). Notable are “star” designs on a background of diagonal criss-crossing lines, “Olmec” face profiles, and the hand-paw-wing motif.

These three motifs are also among diagnostic motifs on pottery from Chotepe-phase contexts (Figure 3). With the addition of the St. Andrew's cross or diagonal crossed bands, the star, face profiles, and hand-paw-wing make up the repertoire of clearly identifiable Olmec-style motifs on vessels from Puerto Escondido. Larger zoomorphic designs are represented by sherds that show the U-bracket that marks the lower jaw of crocodilians on central Mexican vessels. The complete cylinder from Cuyamel reported by Healy (Reference Healy1974:Figure 4e) carries a version of the crocodilian profile. Other sherds from Puerto Escondido and Los Naranjos can be compared to complete vessels with motifs recognizable as parts of shark zoomorphs wrapped around the exterior wall, including vessels from the caves of Copan (Joyce Reference Joyce, Langebaek and Cardenas-Arroyo1996, Reference Joyce, Mills and Walker2008a). These two zoomorphs, a crocodilian and a shark; dominate Honduran “Olmec” imagery, with shark-related imagery more common (Joyce Reference Joyce, Langebaek and Cardenas-Arroyo1996, Reference Joyce, Mills and Walker2008a; Joyce and Henderson Reference Joyce and Henderson2006). Serving vessels, bowls and bottles with these designs on them were clearly used in mortuary rituals and, as our data from Puerto Escondido suggest, for feasts among the living that would have commemorated special events, like the initiation of the first platform construction in the house compounds we excavated.

When compared to the wide range of naturalistic animals and recognizable zoomorphic images from sites in central Mexico to which they have often been compared, such as Tlatilco and Tlapacoya, Honduran ceramic designs are notably more abstract. In this quality, they resemble more the pottery of Pacific Soconusco (Lesure Reference Lesure, Clark and Pye2000), highland Oaxaca (Flannery and Marcus Reference Flannery and Marcus1994), and the Gulf Coast site of San Lorenzo itself (Coe and Diehl Reference Coe and Diehl1980). Ultimately, of course, it was the use of these vessels in serving food and to accompany burials that defined their meaning in the Honduran villages where there were made and used.

The presence of large, hollow, seated figurines has at times been cited as an additional characteristic relating Honduran sites to the Olmec. A small number of hollow figurines were recovered from the caves of Cuyamel (Henderson Reference Henderson, Eggebrecht, Eggebrecht and Grube1992), and fragments of hollow human and animal effigies (Figure 7) were recovered from Chotepe-phase strata at Puerto Escondido (Joyce Reference Joyce2003, Reference Joyce, Renfrew and Morley2007b, Reference Joyce, Robb and Boric2008b). The hollow and solid figurines of Chotepe-phase Honduras are entirely local in their specific forms and iconography and, again, must be understood in local contexts of use, which appear to have paralleled use of the carved serving bowls and bottles in both burials and other special events.

Figure 7. Fragment of animal figurine from Chotepe phase Puerto Escondido. Drawing by Yolanda Tovar.

BEING OLMEC IN MESOAMERICA

The contextual data for Honduran materials that have been related to the Olmec style provide the best basis to begin to address our central question: were Formative period Hondurans trying to “be Olmec”? And if so, what did it mean to “be Olmec” in Honduras, far from the Gulf Coast or central highlands of Mexico? Underlying these questions are issues concerning the relationship of characteristics of material culture with the actions of people, critical to understanding what it would mean to recognize a feature of material culture as diagnostic of an “Olmec” style.

Most researchers understand the repertoire of visual culture that is recognized as “Olmec” as evidence of concepts shared by people participating in similar ritual practices, founded on similar concepts of the structure of the universe. Thus, John Clark and Mary Pye (2000:218) offer a sophisticated way to imagine the spread of Olmec style, suggesting that we compare Olmec

to such terms as Victorian, Carolingian, Roman, or Byzantine, designations that convey a sense of cultural and/or political commitment to certain beliefs, practices, and material representations and that had a definite temporal and spatial distribution but do not encompass the entire history of a people, considered either biologically or linguistically.

Michael Love (Reference Love, Grove and Joyce1999), discussing assemblages from Pacific Coastal Guatemala similar to Honduran sites in their mixture of “Olmec” traits with local ones, argues for treating the everyday use of material culture marked with Olmec-related motifs as a way that ideologies separating elites and non-elites were incorporated in everyday experience, and naturalized. Lesure (Reference Lesure, Clark and Pye2000) explores a similar model for Pacific Coast Mexico, where he sees Olmec graphic style displacing an indigenous representational system in which local animals were featured. As Lesure (Reference Lesure, Clark and Pye2000:212) writes,

after 1000 b.c., social acts involved in the presentation and consumption of food took on new symbolic implications that put these human interactions into a higher-order cosmological framework than they had been seen in before. People organized ideas within this framework by imagining one or more fantastic creatures whose attributes stood for important cultural symbols.

Lesure sees this new conceptual framework as introduced from outside Soconusco as part of a new social order in which stratification was naturalized by reference to concepts symbolized by cosmological zoomorphs. Clark (Reference Clark, DeMarrais, Gosden and Renfrew2004) makes a more pointed argument along these lines, suggesting that engagements with the newly burgeoning materialities of the Early Formative period were central to the elaboration of concepts of “moral superiority,” necessary precursors to the naturalization of social inequality.

It would seem that “being Olmec” is understood by many contemporary researchers as a way of symbolizing and naturalizing newly developed social inequality. In our work at Puerto Escondido, we find evidence for associations of Olmec-style materials with other indicators of stratification (such as differential consumption of luxuries) that might be expected under such a model.

But this account raises other questions. As Lesure (Reference Lesure, Clark and Pye2000) notes, the specific form that “Olmec” style and its introduction take in any one place cannot be generalized. He suggests that the central Mexican highlands continued to produce an iconography of local animals while a preexisting graphic style in which animals were represented was eclipsed in Soconusco by Olmec cosmological zoomorphs. Different preceding histories would lead to different developments, even if the historical processes indexed by Olmec style were the same everywhere.

Models also should take into account the uneven distribution and differing abundances of objects of Olmec style. In any area, the number of objects in apparent Olmec style may be limited, and some will appear unique unless we take a regional scale of analysis. So Bachand (Reference Bachand, Laporte, Arroyo, Escobedo and Mejía2003, Reference Bachand2005) notes that the sample of stamps or seals from most sites is under a dozen; while she has identified over 300 in total, this required including all the area from Mexico to Honduras in her study. Artifacts with stylistic attributes identified as Olmec that are common in one area may be uncommon everywhere else. As a result, we may develop deep analyses of certain categories of artifacts based on unique features of sites where they are common, and shallow “explanations” of the same artifact category arrived at by applying the same ideas to sites where the very rarity of the objects in question should suggest different explanations may be needed.

BEING OLMEC IN HONDURAS

How then should we understand how people in Formative period Honduras were “being Olmec”? Let us begin from the perspective of the everyday experiences of people living in the multiple villages on the formative Honduran landscape. Members of kin groups who cultivated the plants on which they depended likely inhabited these villages. Their specific experiences of cultivating the land would have been variable. At Puerto Escondido, we know that cacao was being cultivated before 1100 b.c. (Henderson and Joyce Reference Henderson, Joyce and McNeill2006; Henderson et al. Reference Henderson, Joyce, Hall, Hurst and McGovern2007; Joyce and Henderson Reference Joyce and Henderson2007). The banks of the Ulua, Chamelecon, and Humuya (Comayagua) rivers were preferred sites of early occupation in this region (Pope Reference Pope1985, Reference Pope and Robinson1987). These rivers ultimately receive most of the water produced by rainfall in Honduras, so that unless there are regional droughts, the land is reliably supplied with abundant water. The sediments brought down from the Honduran highlands annually renewed the soil of river levees. The long-term investment in tree cultivation in such a tropical riverine levee environment would have led to unique relationships to the land and to past and future inhabitants of the same place (Joyce Reference Joyce and Beck2007a).

In contemporary highland communities in the valleys of Copan and Comayagua and in the lakeside settlement at Los Naranjos different regimes of cultivation would have been in place, even if some of the plants cultivated overlapped. At Lake Yojoa, pollen indicates that land was being cleared throughout the lake basin and that maize was being cultivated many centuries before the early houses we excavated at Los Naranjos were built (Rue Reference Rue1989). Maize cultivation in the lake basin would have been heavily dependent on rainfall. Local annual variations in rainfall would have had more of an impact on the maize cultivators of the lakeside than on the people of the Ulua riverbank communities, but the presence of the lake as a source of water and other resources would have buffered year-to-year fluctuations in harvests. The experience farmers at early Los Naranjos had of the land and natural forces would have been quite different from that of the people of Puerto Escondido.

Highland sites like Copan and Yarumela, located on rivers draining less land than those of the lower Ulua valley, would have experienced different conditions from either of the other regions. Local fluctuations in annual rainfall would greatly affect these valleys, as in the basin of Lake Yojoa. Like the lower Ulua Valley, there would have been a strip of more fertile land near the river, where cultivation could most reliably be carried out.

No single cosmology could have made sense of the diverse experiences of the natural and social world that would have arisen from the situated lives of farmers in these different villages. Imagined relations to ancestors, supernatural beings controlling rainfall, and plant spirits, all parts of suggested Formative Mesoamerican cosmologies, would have differed from place to place. In each place, different beliefs about the origins of local populations and their rights to land would likely have developed, particularly if, as has been suggested (Clark and Cheetham Reference Clark, Cheetham and Parkinson2002), the first farmers ignored the preexisting use of the landscape by mobile Archaic people whose territories they occupied with their new permanent groves, fields, and houses.

Nor would such differences in metaphysics have remained at the level of unconscious, unreflected givens. In Pierre Bourdieu's practice theory, such unchallenged ideas, doxa, are what guides behavior in any society (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Nice1977: 164–171). Our earliest traces of villagers at Puerto Escondido show that these people were connected to a broader landscape, extending 50 km to the west to encompass local obsidian sources, and even further to the south to the La Esperanza obsidian source (Joyce et al. Reference Joyce, Shackley, Sheptak and McCandless2004). Whether we conceive of obsidian being acquired directly from the sources (not entirely impossible for the more local sources) or by down-the-line exchange (the more likely possibility for even the local sources and the most reasonable initial assumption for the more distant La Esperanza source), acquiring it joined the early villagers in networks that had more significance than facilitating exchange. At a minimum, exchange of obsidian involved the creation of a common field of value in which both partners agreed that obsidian was useful and roughly calibrated their assessment of its value. It is possible to imagine these exchanges taking place purely as forms of barter, but it is more likely that they were facilitated by existing social relations between partners, formed by marriage, adoption, or claims of common origin that would have made reference to metaphysical concepts. Obsidian exchange in Archaic Puerto Escondido already implies the formation of fields of symbolic understandings expanding beyond the purely local.

Such fields of value clearly expanded in the Ocotillo phase. Earlier pottery at Puerto Escondido already shared modes of form and finish with sites along the Pacific Coast of Guatemala and Mexico. The clay body of these earlier ceramics, and those of the succeeding Ocotillo phase (1400–1100 b.c.) ceramics that continue to share modes with Pacific Coast sites, was locally made. Some of the resemblances between the pottery of Puerto Escondido and other Mesoamerican sites may be attributed to independent adoption of simple, multi-functional shapes, like tecomates (Arnold Reference Arnold, Skibo and Feinman1999). But other resemblances have no such simple functional explanation. Dentate stamping, a main decorative mode in earlier pottery, and narrow-line pattern burnishing, common in Ocotillo phase, are examples. The distributions of these modes do not define a single area of interaction. The former mode links Puerto Escondido to contemporary sites along the Pacific Coast from Soconusco to Nicaragua and Costa Rica. The latter mode is found in sites from Cuello in northern Belize to the Pacific Coast of El Salvador (Arroyo Reference Arroyo, Barnett and Hoopes1995).

How can we understand such distributions from the perspective of locally embedded daily practices, and how do locally structured practices simultaneously structure broader relations? Studies of design resemblances in archaeology traditionally assumed that designs are symbols of group or subgroup identity, displayed to others to clarify social relationships. More recent work has suggested that the recognition of design similarities as information drops off quickly, so that microvariation may be more interpretable within communities than are generalized similarities between communities (Bowser Reference Bowser2000). Common modes of forming and finishing vessels may better be considered products of learning how to make pots properly, evidence of being a proper person within a local context (Minar and Crown Reference Minar and Crown2001; Wallaert-Pétrie Reference Wallaert-Pétrie2001). Ways of making and finishing objects properly would have been among the values being coordinated in networks of villages in which at any time a few people might be moving as a result of marriage, adoption, or other forms of social affiliation.

While as archaeologists we see artifact modes and raw materials as the traces of social relations, it was the social relations themselves that formed the fields of value, not the reverse. The adoption of thin-line pattern burnishing in a number of Honduran communities as the dominant mode of decoration for unslipped and red-slipped pottery was the outcome of intervillage social ties that spread similar ideas of what proper pots should look like. Microvariation within each village could have been recognizable and interpretable to the ancient inhabitants. The patterning we record (diagonal or perpendicular lines, arcs) and placement on vessels may well have been quite legible to villagers in the kinds of very precise ways Brenda Bowser (Reference Bowser2000, Reference Bowser2004) has explored in her work on Amazonian potters.

In Honduras, as in Soconusco (Lesure Reference Lesure, Clark and Pye2000), there was already a symbolic representational system in place when “Olmec” motifs entered into the wider network of which Puerto Escondido was a part. The representational system of Ocotillo phase Puerto Escondido was geometric, with signs formed by sets of lines. Such signs do not communicate meaning primarily by resemblance (icons) but by convention, acting as indices and abstract symbols. This emphasis on noniconic signs, including an apparent absence of figurines before the Chotepe phase, differentiates the Honduran village from contemporary communities elsewhere in Mesoamerica (Joyce Reference Joyce, Renfrew and Morley2007b, Reference Joyce, Mills and Walker2008a).

The preference for conventionalized geometric motifs rather than iconic imagery that typifies Chotepe-phase Honduran pottery with excised “Olmec” motifs may be a way of making meaning through pottery decoration that builds on this existing local history. From the local perspective of Honduran potters, new imagery in broader networks to which they were connected may have been viewed less as representations of gods or supernatural beings, and more like crests, emblems of identity, where it is less important to be able to see a visual resemblance to a shark or crocodile than to present specific clusters of motifs consistently (Joyce Reference Joyce, Langebaek and Cardenas-Arroyo1996, Reference Joyce, Mills and Walker2008a). This is neither to say that the resemblance of a shark design on a vessel from Copan to an actual shark was entirely coincidental, nor to say that such crests were unrelated to sacred propositions and metaphysical accounts. But for new imagery to gain a foothold in a preexisting local set of social relations mediated by intercommunity communication, it would have had to be compatible with existing understandings of the place of humans in the world and their relations to ancestors and spirits and compatible with existing practices of representation and interpretation.

Based on the range of material practices seen there and the higher proportion of the local assemblage transformed during the Chotepe phase, Puerto Escondido would seem to have been a central place in the new network that linked Honduras and broader Mesoamerica in the late Early Formative period. For people at Puerto Escondido, this global network may well have introduced new media to create and symbolize social distinction within the community, but social distinction itself was already present, evident in differences in architecture, access to exotic raw materials, and use of these materials in costume. Exotic materials and costumes were likely used during community and household social ceremonies such as those at the time of burial. The elaboration of primary burials in village sites and secondary burials in mountain cave shrines was a local Honduran way of commemorating the dead and marking their social disarticulation and incorporation in groups of the deceased (Joyce Reference Joyce1992, Reference Joyce, Grove and Joyce1999). The incorporation in such burials of costume ornaments suggests the importance of individual life stages and other affiliations marked by these materials. The inclusion of serving vessels indexes food sharing by the groups of survivors in both everyday life and in special ceremonial meals.

While burials are most visible to us today, other contexts for the use of these things would have been ceremonies at birth, marriage alliance, and other life events (Henderson and Joyce Reference Henderson, Joyce and McNeill2006; Joyce and Henderson Reference Joyce and Henderson2007). These were moments when social relations were actively being reformulated, when shifts in social relations and the histories that grounded them could be proposed and tested, when mythic charters and ancestral epics would be appropriately recounted. Where graphically marked vessels were incorporated in burials, social identities were critically recomposed in life cycle events in ways that might not have been relevant outside the local context. For example, Honduran hollow figurines are notable for their depiction of features of old age and for the inclusion of indications of a central pubic apron that most likely was a garment of females (Joyce Reference Joyce2003). If images like this are, as John Clark (Reference Clark, DeMarrais, Gosden and Renfrew2004) argues, part of the genealogy that leads to monumental images of rulers, then Hondurans who were being Olmec apparently conceived of a special place in their metaphysics of distinction for certain adult and elderly women.

DISCUSSION

Honduran Formative peoples may well have striven to be “Olmec,” but they were not being Olmec in the manner of the contemporary Gulf Coast, central Mexico, or even Soconusco. In Honduras, to be “Olmec” was to be at once a participant in wider networks that coordinated value and propagated an acceptance of hierarchy and to be firmly rooted in local, diverse cosmologies that related humans to the land, to history, and to localized supernatural beings. To be Olmec in Honduras meant to create local material cultures of bodily adornment and feasting that expanded the ways that distinction could be made patent by drawing on practices of partners in wider networks. To be Olmec in Honduras was to innovate forms of social relations by employing the active capacity of material culture to reconstitute meanings, especially when mobilized in contexts already sanctioned for reformulating social relations.

Most, perhaps all, of the early materials that have been labeled “Olmec” in Honduras were likely of local manufacture. They do not constitute a canonical body of materials according to standards from the Gulf Coast, central Mexico, or Soconusco, nor should they be expected to do so. Honduran sites exemplify knowledge of the entire range of practices innovated elsewhere. They cannot be described as peripheral to Mesoamerican Formative period networks in any sense except the geographic.

If we are, following Clark and Pye (Reference Clark, Pye, Clark and Pye2000), to consider “Olmec” as a term like Byzantine or Victorian, we need to contend with the reality that these other historical stylistic terms do not label well-bounded geographic and temporal distributions of materials that had a single, well-defined source. Rather, they encompass a range of materials whose similar features stem from complex roots, including religious, economic, and social practices resulting in the movement of worked materials inspiring secondary products that might be faithful to the originals or quite innovative and, once distant from their sources, reinterpreted in ways quite distinct from their understanding at their sources. With such a proviso, we might be able to speak of Honduran Olmecs but with our focus firmly on the people and their practices, not the materials and the ideas we might assume they unproblematically represent.

RESUMEN

Los investigadores de la arqueología del periodo formativo han identificado objectos, rasgos, y temas artísticas como indicadores de un supuesto estilo “olmeca.” Cuando se encuentran objetos con tales rasgos en la zona del golfo de México, donde en sitios como San Lorenzo se desarollaba la cultura arqueológica propiamente dicho “cultura olmeca,” es posible considerarlos como evidencias de procesos de incorporación de la gente en esta cultura. La situación es sumamente diferente cuando se trata de rasgos, diseños y objetos semejantes fuera de la costa del golfo, como en las tierras altas de México, y siempre es más complicado cuando estos se encuentran a grandes distancias de la región del golfo, como es el caso de Honduras. Desde los finales del siglo XIX, se han destacado objetos de un supuesto “estilo olmeca” en Honduras, siempre de manufactura local y en proporciones bajas. Aparecen vasijas grabadas con motivos reconocidos en toda la zona mesoamericana como parte del sistema de símbolos asociado a la cultura olmeca y sus aliados y de objetos como sellos cilíndricos y estampaderas con los mismos diseños. Aunque nuncan llegan a ser predominantes, la presencia de estos objetos tiene que ser explicada. En este articulo proponemos que la explicación requiere atención a las condiciones locales. Consideramos lo que significa actuar de una manera conforme al estilo "olmeca" durante el período formativo temprano en Honduras.

Basándonos en nuestras investigaciones de campo en los sitios de Puerto Escondido y Los Naranjos, y en estudios de objetos excavados anteriormente de otros sitios en Honduras, sugerimos que podemos entender la situación hondureño sólo con un modelo de los efectos de la materialidad, la experiencia del ser humano y la creación de identidades humanas por medio de nexos con la materialidad.

Pensamos que los muchos asentamientos hondureños, con sus ambientes naturales muy variados, no participaban en una sola ideología o cosmología. Aunque podemos pensar que tenían generalidades compartidas en cuanto a las relaciones entre seres humanos y fuerzas sobrenaturales, si la religión es parte de la estructura social, debería variar entre una sociedad y otra. Cada aldea ocupado por una población formativa estaba al centro de su propio mundo social y su seleción de temas de arte, de objetos de uso cotidiano, de ceremonias y sus utensilios, tiene que considerarse como fundado en condiciones locales antes de buscar raices foráneas. Desde esto punto de vista, el desarrollo en Puerto Escondido de normas nuevas e innovadoras, para vasijas ceramicas entre 1100 y 900 a.C. se destaca como un cambio en la tradición local. El hecho de que las innovaciones exhiben tendencias a coincidir con normas de otras partes de Mesoamérica, por ejemplo, en la producción por medio del control de la cocción de vasijas con contraste entre negro y bayo o gris, nos indica que la población, o elementos de la población, de la aldea hondureña tuvieron conocimiento de prácticas de otras partes de un territorio cosmopolitano.

En Honduras, actuar como “olmeca” implicaba participar en una red de extensión muy grande, por medio de la cual los valores estuvieron coordinados por medio del canje y el compartimiento de prácticas cotidianas y rituales. Por medio de la participación en redes de interacción, ideales de jerarquía fueron propagados. A la vez, las prácticas e ideales obtuvieron fuerza de sus raices en cosmologías locales y diversas, en relación con los seres humanas, sus historias, sus nexos con la tierra y con seres sobrenaturales de la localidad. Actuar como “olmeca” en Honduras significaba crear materialidades para ornamentar la persona y para los festejos, para ampliar las modalidades de indicar distinción social, utilizando prácticas de otras partes de la red internacional. Actuar como “olmeca” implicaba innovar nuevas formas de relaciones sociales empleando activamente la capacidad de la materialidad de reconstituir significaciones, particularmente cuando la materialidad estaba utilizado en contextos ya aprobados por la tradición de reformular relaciones sociales, como las ceremonias mortuarias.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Fieldwork in Honduras has been carried out with the permission of the Instituto Hondureño de Antropología e Historia. We would like to acknowledge the several directors of the Institute who have supported our work over many years and in particular the former Jefe de Investigaciones, Lic. Carmen Julia Fajardo, and the former Regional Representative of the Institute for the North Coast, the late Lic. Juan Alberto Durón. Funding for research described here was provided by grants from the National Science Foundation, Wenner-Gren Foundation, H. J. Heinz Charitable Trust, and Foundation for Ancient Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. A version of this paper was presented in the symposium “Identidad social: localidad y globalidad en el mundo prehispánico e indígena contemporáneo/Social Identity: Local and Global in the Pre-Hispanic and Contemporary Indigeneous World,” organized by Julia Hendon and Miriam Judith Gallegos Gómora at the 52nd meeting of the International Congress of Americanists, Sevilla, July 20–21, 2006.