During the past three years, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has caused disruptions and changes in global societies and brought to attention the current and future threats of world-wide public health emergencies. As of the end of 2022, it is estimated that there have been 16 to 18.2 million deaths related to COVID-19. Reference Acosta1 During the past two and a half years, there have been remarkable successes in responding and preventing the spread of the pandemic and dramatic failures at the same time.

The COVID-19 pandemic was officially recognized by the World health Organization (WHO; Geneva, Switzerland) in March 2020. Probably the most dramatic success in addressing the pandemic was the development of multiple effective vaccines in less than a year. Reference Li, Wang and Pang2 Further was the rapid ability to redesign COVID-19 vaccines to address variant changes in the virus. Reference Li, Wang and Pang2 Without the development and updating of the vaccine, it is likely that the death toll from the virus would expand unchecked, possibly altering human populations as occurred during the plagues of the middle ages.

Another little recognized success in addressing the pandemic was the professionalism and dedication demonstrated by public health and medical care providers in community access to testing and vaccination. The organized and professionalism of health workers showed dedication that helped define the extent of the pandemic and provide large numbers of people with vaccine-induced immunity to the virus. Most commendable were those who provided primary health care in hospitals, clinics, long-term care facilities, and ambulances. The dedication of health care providers was a true example of altruism at the risk of personal harm to self and family.

Along the line of health care providers performing direct clinical care, health care systems further developed telemedicine using established online communication platforms. The expansion of telemedicine helped maintain community health care for non-acute conditions and will likely change future health care delivery to improve access to health care for those populations with internet access.

Due to previous preparation for possible pandemic influenza, public health systems had planned and exercised in response to a viral pandemic. While COVID-19 was more highly infectious and deadly compared to influenza, the same principles as used to prepare for a viral pandemic were developed and quickly applied for the COVID-19 pandemic by experienced public health providers.

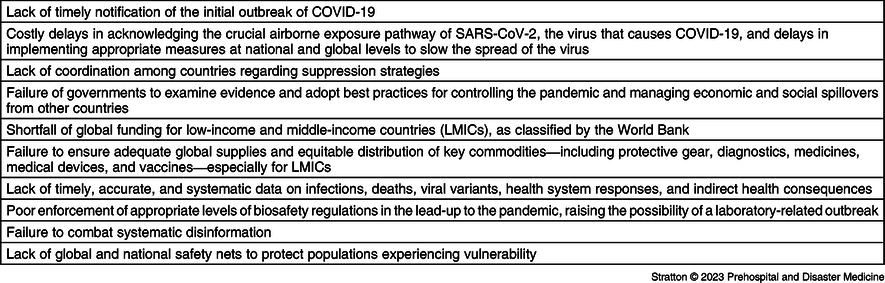

In September 2020, the Lancet Commission on COVID-19 explored the early failed experiences with COVID-19 spread and control among the world’s populations. 3 The Commission report was presented to the United Nations General Assembly in 2020 with the hope that identified failures in the global response to the pandemic would be addressed. Subsequently, a follow-up Commission report on the global pandemic experience was made in 2022 with ten world-wide failures in international cooperation listed. Reference Griffin4 To date, these Commission reports have been the most comprehensive analysis of the impacts of the pandemic on global public health. Reference Griffin4 Below, three of the ten Commission findings relative to public health and government failures during the pandemic are addressed (Table 1).

Table 1. Lancet COVID-19 Commission Findings

Note: Source cited: The Lancet. 2022;400(10359):1224-1280. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01585-9.

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; LMIC, low- and middle-income countries.

An early pandemic response failure was “the lack of timely notification of the initial outbreak of COVID-19.” International agreements regarding disaster risk reduction are defined by the United Nations with the Sendai Framework and includes agreement among United Nations members for the prompt notification of infectious disease outbreaks the may spread across national boundaries. Reference Sachs, Abdool Karim and Aknin5 The failure of the government and public health officials of the country in which the first evidence of the COVID-19 outbreak has been well-established. 6 As opposed to international agreements and ethics, the COVID-19 country of origin suppressed knowledge of the original outbreak and further censored and individuals who recognized the disease. 7 Further social media and communications channels were censored with respect to discussion of the COVID-19 outbreak. 7 The active government suppression of notification of world health groups of the COVID-19 outbreak allowed trans-boundary spread of the disease and the rapid development of a pandemic as infected individuals traveled world-wide by air and ship. It is likely the reason for government suppression of notification of COVID-19 was the concern that the economic and political standing of the origin nation would be threatened. To add to the lack of cooperation by the origin nation, any efforts to assess the epidemiology and beginnings of COVID-19 were thwarted by the refusing to allow multinational based epidemiological evaluations. Governmental failures in adhering to international disaster risk reduction standards and overt suppression of the original outbreak was a primary cause for rapid unrestricted global spread of COVID-19 (Author’s opinion).

To further illustrate government failure, the WHO was found by the Commission to have been slow to declare a Public Health Emergency of International Concern regarding COVID-19. The virus spread outside the original outbreak area was recognized in a number of areas in January 2020, yet the WHO delayed in declaring the emergency until March 2020. Reference Griffin4 The failure to adhere to the WHO’s own United Nations Sendai Framework was likely driven by political pressures, including protection of the country of origin from world scrutiny. Different from the rapid notifications and actions taken previously by the WHO regarding the Ebola outbreak on West Africa, it also appears that WHO is influenced by wealthy nations (donors) as opposed to lower-income nations (Author’s opinion).

Another finding of the Lancet Commission was the “lack of timely, accurate, and systematic data on infections, deaths, viral variants, health system responses, and indirect health measures.” Reference Griffin4 Basic competence public health is the reliance on systematic population-based data to determine appropriate population threats and effectiveness of corrective actions to limit effects of a pandemic. To date, the global mortality rate from the COVID-19 pandemic can only be estimated due to lack of valid and accurate data. Reference Acosta1 Even for highly developed and technologically sophisticated nations, the COVID-19 data cannot be validated. For example, in the United States, infection rates were determined by tracking those persons who elected to be tested for COVID-19, representing a convenience sample method. Convenience samples are not drawn at random from the target population. Therefore, the research cannot be generalized to a cohort or population other than the sample group. A further issue with convenience sampling is that there is not an ability to determine potential sampling error, selection bias, and motivation bias of participants to engage with COVID-19 testing. Further, mortality data were primarily calculated by in-hospital death data with out-of-hospital deaths generally not included, representing an incomplete data gathering methodology. Further, COVID-19 case-based mortality was not defined, and potentially those who died of any non-COVID-19 cause, who were also determined to have COVID-19 positive testing, were included in the mortality data, causing lack of reliability of mortality data estimates.

A third failure identified by the Commission was “the failure to combat systematic disinformation.” Social media platforms are the modern means of dispersing information in many world social groups. The WHO and public health announcements through traditional media were cumbersome and fell behind the dispersal of social media information. Failure of both public health and government to understand and address the influence of social media was dramatic during the pandemic. Often, efforts such as masking, closure of public venues, and social distancing requirements were instituted in many nations without communication of the rationale for such measures to those relying on social media. Unfortunately, formal public health and government COVID-19 messaging was usually based on outdated practices of issuing government statements and reliance on traditional media, showing a lack of understanding of the communities and populations that public health and government are responsible for serving during a pandemic.

In summary, there were national and global successes and failures in government and public health prevention and response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The global community now faces the unknown long-term effects of the pandemic and hopefully public health and government leaders can adapt to the “new COVID-19 world.”