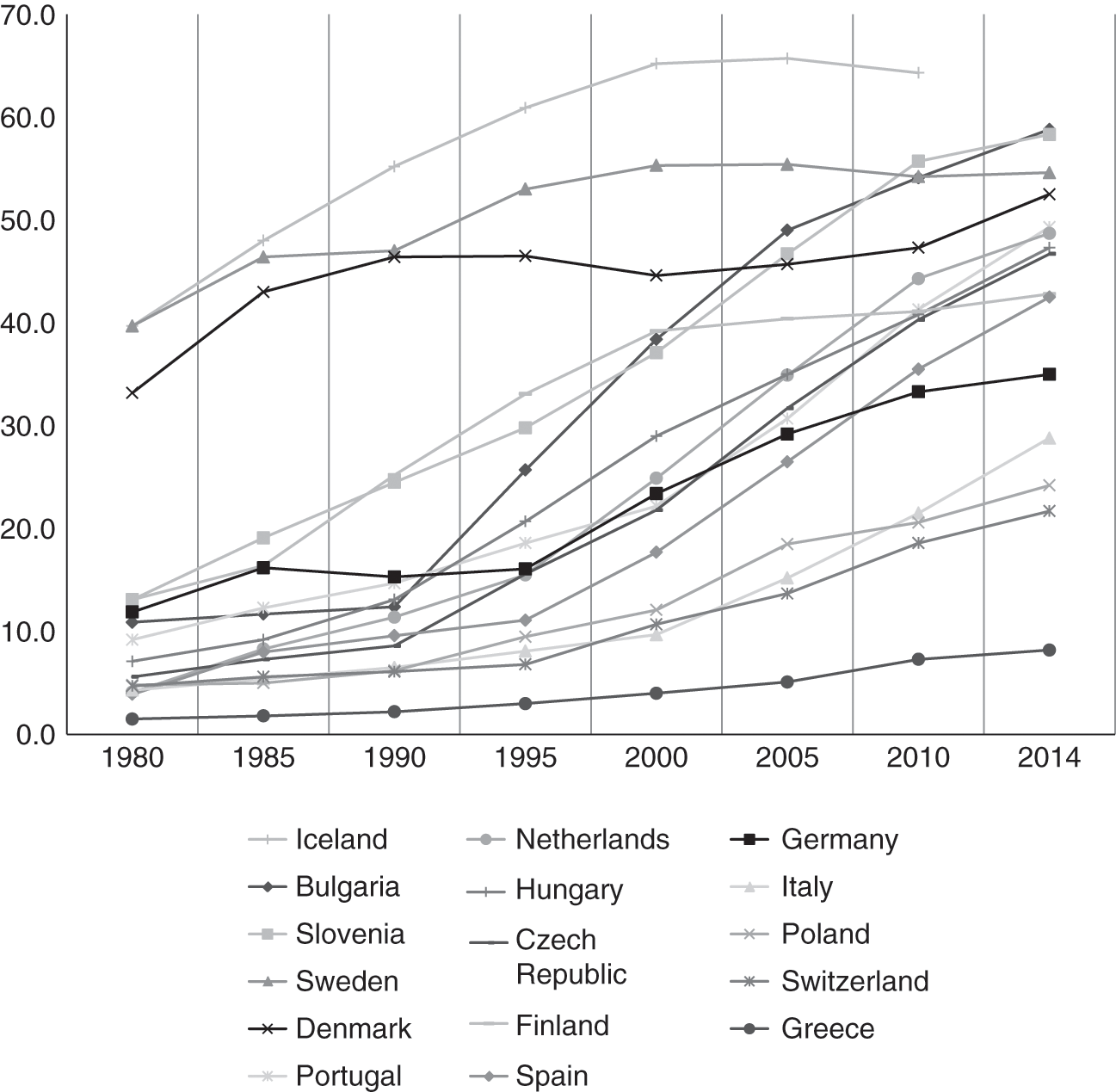

New family formation behaviors have increased nearly everywhere in Europe. Cohabitation, childbearing within cohabitation, divorce, separation, and repartnering have all become more common, even in places where scholars did not think that these behaviors would emerge (see Chapter 1). Recent data from the OECD (2016a) shows that nonmarital fertility, for example, increased dramatically in nearly every country in Europe throughout the 2000s, even across much of southern and Eastern Europe (Figure 4.1). However, European countries still vary widely with respect to the prevalence of new family formation behaviors. For example, in Norway, Sweden, and Denmark, the majority of births occur within cohabitation, while in other countries, such as Italy and Romania, childbearing within cohabitation is still relatively rare (Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Kreyenfeld and Sigle-Rushton2012). Figure 4.1 shows that although nearly every country in Europe experienced increases in nonmarital fertility, the year in which the increases began differs across countries, as does the speed of the increase.

Figure 4.1 Percentage of nonmarital births in selected countries, 1980–2014

The nearly universal increase in new family formation behaviors coupled with the diversity in the timing and rate of increase raises questions about whether the underlying causes are universal, or if the process of development is unique in each context. Several scholars have proposed overarching theories to explain the observed changes, the most well-known of which is the second demographic transition (SDT) (Lesthaeghe Reference Lesthaeghe2010; Van de Kaa Reference Van de Kaa1987). Proponents of SDT theory posit that shifting values, ideational change, and increasing individualization have led individuals to choose unconventional lifestyles and living arrangements, often defying the traditional marital pathway of their parents (Lesthaeghe Reference Lesthaeghe2010). SDT theory also implies that those with higher education were the forerunners of the change, as they challenged patriarchal institutions and focused on the pursuit of self-actualization (Lesthaeghe and Surkyn Reference Lesthaeghe and Surkyn2002).

There is scant evidence, however, that the emergence of new behaviors is due to the pursuit of self-actualization or practiced by the more highly educated. Indeed, recent evidence (as discussed in Chapter 1) indicates that childbearing within cohabitation is associated with lower education (Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Kreyenfeld and Kubisch2010), divorce has increasingly become associated with lower education (Matysiak et al. Reference Matysiak, Styrc and Vignoli2014), and the highly educated are more likely to marry (Isen and Stevenson Reference Isen and Stevenson2010; Kalmijn Reference Kalmijn2013). These studies suggest that new forms of family behaviors are associated with a “pattern of disadvantage.” Although social norms have shifted to become more tolerant of cohabitation and nonmarital childbearing, the less-educated face greater uncertainty and economic constraints, which is reflected in their relationship choices (Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Kreyenfeld and Kubisch2010).

Nonetheless, despite evidence that many aspects of the family are changing across Europe, and some of these new aspects are associated with lower education, a consistent association between family change and social class has not been observed for all behaviors or in all contexts (Mikolai, Perelli-Harris, and Berrington Reference Mikolai, Perelli-Harris and Berrington2014; Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Kreyenfeld and Sigle-Rushton2012). Superficial trends may be masking substantial underlying differences in specific processes and consequences. In fact, research has found that although many aspects of family formation are changing, they might not be converging in the same way or toward a similar standard (Billari and Liefbroer Reference Billari and Liefbroer2010; Sobotka and Toulemon Reference Sobotka and Toulemon2008). Several studies have found that while transitions to adulthood are becoming more complex, heterogeneous, and “destandardized” throughout Europe, trajectories do not appear to be converging on one particular pattern or type of new trajectory (Elzinga and Liefbroer Reference Elzinga and Liefbroer2007; Fokkema and Liefbroer Reference Fokkema and Liefbroer2008; Perelli-Harris and Lyons-Amos Reference Perelli-Harris and Lyons-Amos2015). In addition, while some elements of partnership formation, such as the postponement of marriage, seem to be universally associated with higher education, country context appears to be much more important for predicting partnership trajectories than individual-level educational attainment (Perelli-Harris and Lyons-Amos Reference Perelli-Harris and Lyons-Amos2016). Thus, while some aspects of family formation, such as the postponement of marriage and fertility, seem to be changing on a wide scale, others, such as long-term cohabitation and union dissolution, seem to be dependent on the social, economic, political, religious, and historical contexts that shape family behavior.

In this chapter, I will explore the diversity and similarity of partnership experiences throughout Europe, drawing on recent research and evidence. I will focus on the emergence of cohabitation as a new family form, especially as a context for childbearing. Cohabiting unions are heterogeneous living arrangements, with some couples sliding into temporary partnerships of short duration, others testing their relationship to see if it is suitable for marriage, and still others living in long-term committed unions with no intentions of marriage (Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Mynarska and Berghammer2014). Yet, on average, cohabiting unions are more likely to dissolve, even if they involve children (Galezewska Reference Galezewska2016; Musick and Michelmore Reference Musick and Michelmore2015). Also, as discussed above and in Chapter 1, childbearing within cohabitation is often associated with low education, resulting from a pattern of disadvantage (Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Kreyenfeld and Kubisch2010). Thus, the costs of union dissolution more commonly fall on already disadvantaged individuals, potentially exacerbating inequality.

This chapter will cover findings from a mixed methods project that examined cohabitation and nonmarital childbearing across Europe and the United States from different analytical perspectives.Footnote 1 First, I will describe the spatial variation in nonmarital fertility across Europe to illustrate how patterns of family change may be influenced by political or cultural borders as well as the persistence of the past. Second, I will outline the laws and policies governing cohabitation in nine European countries to demonstrate how welfare states may be ill-equipped to deal with the new realities of more people living outside marriage. Third, I will draw on a large focus group project to describe discourses surrounding cohabitation and marriage in eight European countries to better understand similarities and differences in cultural and social norms. Finally, I will address the potential consequences of new partnership behaviors by summarizing a recent project that examines the health and well-being of cohabiting and married people. This section will discuss whether marriage, versus remaining in cohabitation, provides benefits to adult well-being beyond simply living with a partner. Throughout, I will speculate about why partnership behaviors differ across countries. Taken together, these studies portray a complex picture of family change in Europe today and raise questions about whether the interrelationship between family trajectories and inequality may be mediated by country context.

The Diffusion of New Family Behaviors: Universal Change – Uneven Distribution

One of the best ways to illustrate the diversity of family formation behaviors is with a map (Figure 4.2, Klüsener, Perelli-Harris, and Sánchez Gassen Reference Klüsener, Perelli-Harris and Gassen2013). The variegated landscape of nonmarital fertility can reveal clues into the fundamental reasons why marriage has declined in some countries, while remaining the predominant context for childbearing in others. Figure 4.1 shows the percentage of nonmarital births across Europe in 2007, with the lightest regions indicating that less than 10% of births occur outside marriage and the darkest regions indicating that up to 75% of births occur outside marriage. Note that the diffusion of nonmarital fertility has primarily been driven by the increase in childbearing within cohabiting partnerships, not births outside a union (Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Kreyenfeld and Sigle-Rushton2012). Thus this map portrays a rapid increase in a new and emerging behavior. More recent nonmarital childbearing statistics on the national level (OECD 2016a) suggest that the entire map has become even darker over the past seven years as the percentage of births outside marriage has reached unprecedented highs; however, these statistics are not available on the regional level. The map shown here is important for showing gradations of patterns on the regional level, thus providing insights into the link between spatial variation and the persistence of the past (Klüsener Reference Klüsener2015).

Figure 4.2 Percentage of births outside marriage, 2007

First, notice that the patchwork of high and low regions does not necessarily accord with particular welfare regimes, or even typical geographic areas. Nonmarital fertility is very high in the Nordic countries, with the highest levels in northern Sweden and Iceland, reflecting a long history of female independence and permissiveness of alternative living arrangements (Trost Reference Trost1978). Nonmarital fertility is also high in France, where cohabitation rose rapidly during the 1980s, possibly due to policies which favored single mothers or as a rejection of the Catholic Church and the institution of marriage (Knijn, Martin, and Millar Reference Knijn, Martin and Millar2007). Eastern Germany also stands out as a region with particularly high levels of nonmarital fertility, dating back to the Prussian era (Klüsener and Goldstein Reference Klüsener and Goldstein2014) and increasing during the socialist period through policies favoring single mothers (Klarner Reference Klärner2015), and after the collapse of socialism, by high male unemployment and female labor force participation (Konietzka and Kreyenfeld Reference Konietzka and Kreyenfeld2002). Of the Baltics, Estonia has the highest level of nonmarital fertility, reflecting greater secularization than in Latvia and Lithuania, which have maintained Catholic or traditional social norms favoring marriage (Katus et al. Reference Katus, Põldma, Puur and Sakkeus2008). Bulgaria is another, southern European, country with unexpectedly high levels of nonmarital fertility, possibly due to cultural practices in rural areas or as a response to economic insecurity (Kostova Reference Kostova2007). Other regions also have surprisingly high nonmarital fertility, for example, parts of Austria and southern Portugal, which harken back to norms only permitting marriage upon inheritance of the family farm.

Very low levels of nonmarital fertility are primarily concentrated in southern Europe, for example, in Greece, Albania, and southern Italy. Studies have indicated that Italy has had a “delayed diffusion” of cohabitation, potentially because parents have opposed their children living together without being married (DiGiulio and Rosina Reference Di Giulio and Rosina2007; Vignoli and Salvini Reference Vignoli and Salvini2014). The vast majority of births also continue to occur within marriage in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, and Serbia, reflecting traditional religious and cultural practices (Klüsener Reference Klüsener2015). In addition, a large swathe of Eastern Europe has very low levels of nonmarital fertility, including parts of eastern Poland, Western Ukraine, and Belarus. Thus, this map and more recent data (OECD 2016a) indicate that some areas appear to be resistant to the changes sweeping across Europe, although some of the very low levels may be due to underreporting (Klüsener Reference Klüsener2015).

When we look closer at the map, we can further see that both political and cultural borders can be very important for delineating the patterns of nonmarital fertility (Klüsener Reference Klüsener2015). In some instances, distinct state borders imply that national policies and legislation can have a strong effect on decisions to marry. For example, the Swiss–French border denotes a sharp distinction between high levels of nonmarital fertility in France and low levels in neighboring Switzerland, despite sharing a similar language and employees who commute daily. The strong distinction in nonmarital fertility is most likely due to strict Swiss policies for unmarried fathers, who were not allowed to pass down their surname if they were not married to the mother of their child. Note, however, that these policies were recently relaxed, and 2014 estimates indicate rapid change with one fifth of all Swiss births outside marriage (OECD 2016a).

In some regions, however, state borders do not define patterns of nonmarital fertility, suggesting that cultural or religious influences are more important. For example, the percentage of nonmarital births is very low across the borders of eastern Poland and Western Ukraine, despite different family policy regimes (Sánchez Gassen and Perelli-Harris Reference Sánchez Gassen and Perelli-Harris2015), indicating that the long history of Catholicism in this area has maintained strong social norms toward marriage. Furthermore, some countries have strong differences within their borders, for example nonmarital childbearing varies considerably from the north of Italy to the tip of the boot. In sum, it is fascinating to stare at the map and recognize that both political and cultural factors may influence such a fundamental demographic phenomenon as the partnership status at birth. Below I investigate these factors in more detail.

Policies and Laws: Universal Rights – Unequal Treatment

Along with complex social and cultural factors, the countries of Europe are defined by a complicated array of policies, laws, and welfare institutions, all of which shape the family and the relationship between couples (Neyer and Andersson Reference Neyer and Andersson2008). Family demographers have long examined how welfare state typologies (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990) and constellations of family policies influence fertility (e.g., Billingsley and Ferrarini Reference Billingsley and Ferrarini2014; Gauthier Reference Gauthier2007; Thévenon Reference Thévenon2011) and lone parenthood (Brady and Burroway Reference Brady and Burroway2012; Lewis Reference Lewis1997). Here, I will discuss the laws and policies that govern marital and cohabiting relationships. This perspective will provide insights into how legal rights and responsibilities are similar or different across countries, sometimes as a result of underlying economic and welfare state models. It is important to keep in mind that laws and regulations often provide couples with a sense of security and stability, which may influence decisions around partnership formation and marriage. In addition, depending on how they are enacted and enforced, laws and policies may also potentially exacerbate disadvantage and inequality.

Up to the 1970s, marriage was the primary way of organizing family life. European states regulated couples and families primarily through the institution of marriage by providing rights such as joint taxation, widow’s pensions, and inheritance only to married couples (Coontz Reference Coontz2005). In addition, states regulated the relationship between parents and their children, for example, children’s rights to maintenance and inheritance and parents’ rights to child custody and recognition. Until the mid-twentieth century, marriage was the only living arrangement in which childbearing was legitimate, but gradually discrimination against children born outside marriage was abolished and single mothers were granted custody. By the mid-1970s, most European states had also developed legal mechanisms for dissolving a marriage that would regulate the division of assets and financial savings and provide alimony to the weaker party in case of divorce (Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Berrington, Gassen, Galezewska and Holland2017a).

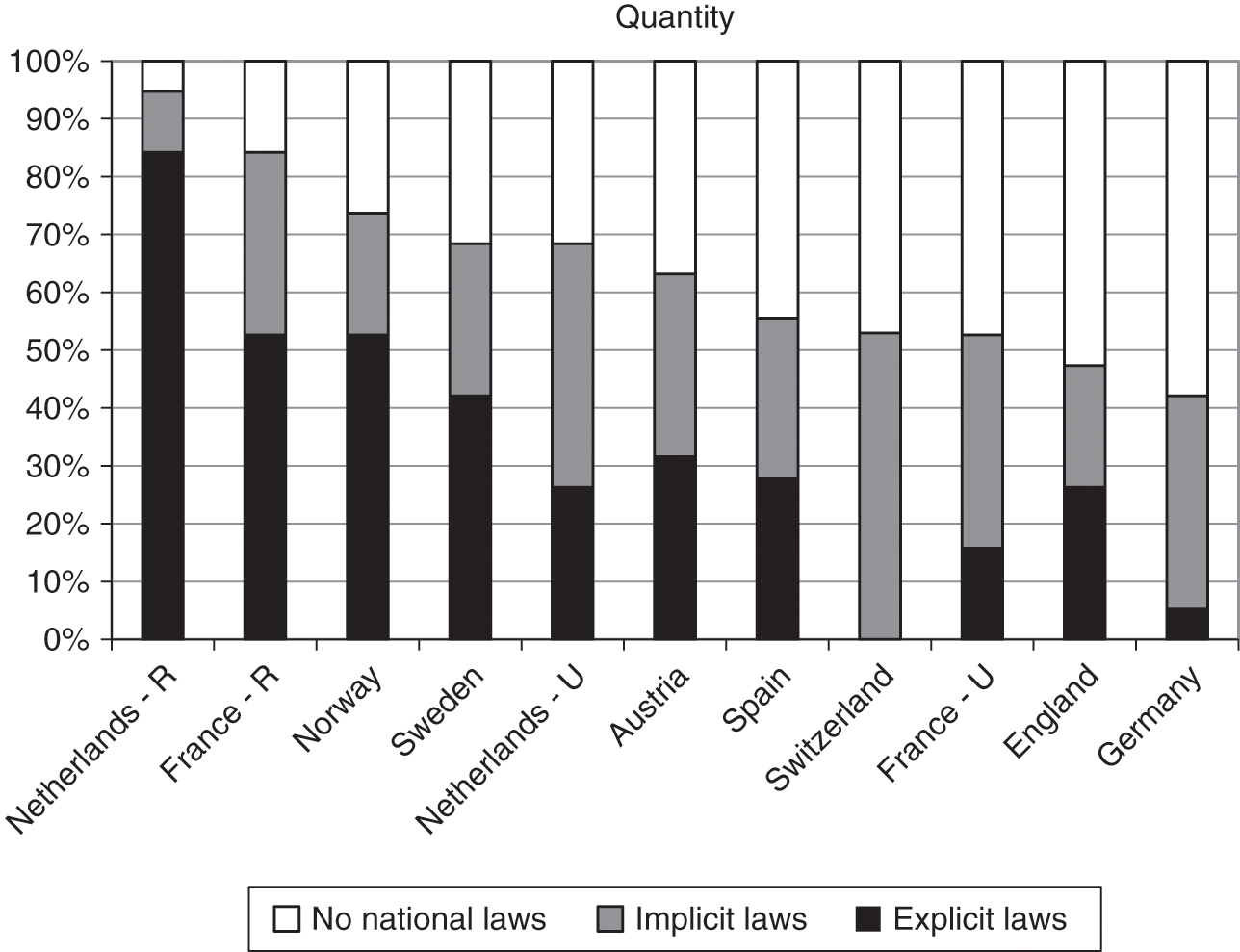

Over the past few decades, many states have started to extend the rights and responsibilities of marriage to couples living in nonmarital relationships (Perelli-Harris and Sánchez Gassen Reference Perelli-Harris and Sánchez Gassen2012). The extent of the legal recognition of cohabitation depends on historical developments, resulting in great variation in the degree of harmonization between cohabitation and marriage across the continent (see Figure 4.3). Generally, countries have taken one of several approaches to recognizing and regulating cohabitation (Sánchez Gassen and Perelli-Harris Reference Sánchez Gassen and Perelli-Harris2015). Some countries, for example, Sweden and Norway, have extended many marital rights and responsibilities to cohabiting couples, especially if they meet certain conditions such as living together for a defined period (e.g., two years) or having children together. Countries such as the Netherlands and France have implemented an opt-in approach, which entitles registered partners (in the Netherlands) or PACS (civil solidarity pacts; in France) to additional rights, such as joint income tax and inheritance, but made it easier for them to separate than divorce. Still other countries, such as England and Spain, have taken a piecemeal approach, with rights extended in some policy domains but not others. As Figure 4.3 shows, these different approaches have resulted in countries falling along a continuum in the degree to which they have harmonized cohabitation and marriage policies, with countries that have adopted registered partnerships and marriage-like arrangements at one end, and countries which favor marriage, such as Switzerland and Germany, at the other (Perelli-Harris and Sánchez Gassen Reference Perelli-Harris and Sánchez Gassen2012).

Figure 4.3 Percentage of policy areas (out of 19) that have addressed cohabitation and harmonized them with marriage in selected European countries

Note: R = registered cohabitation or Pacs; U = unregistered cohabitation.

One policy area that has changed in all countries has been the expansion of the rights of unmarried fathers. Unmarried fathers have the right to establish paternity and attain joint – or sole – custody over their children; however, in all countries they must take additional bureaucratic steps to establish paternity and/or apply for joint custody. Another area which is similar across most countries is the restriction of welfare benefits for cohabiting partners. Generally, unemployment benefits are means-tested and based on households, taking into account the income of all household members (including cohabiting partners). Other policy areas depend on the fundamental relationship between the state, the individual, and the family. Tax systems in Sweden and Norway, for example, are organized around the individual rather than the couple, resulting in similar tax rules for cohabiting and married individuals. Germany and Switzerland, on the other hand, which continue to favor the male breadwinner model, only allow married couples to benefit from tax breaks if one partner earns more than the other.

One of the areas which can have the greatest consequences for the reproduction of inequality is whether cohabitants who separate are protected by the law or have access to family courts. As many studies have shown, cohabiting couples have higher dissolution risks, even when the couple has children together (Galezewska Reference Galezewska2016; Musick and Michelmore Reference Musick and Michelmore2016). Often these couples have lower education and income, putting them at greater risk of falling into poverty (Carlson (this volume); Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Kreyenfeld and Kubisch2010). The lack of legal protection for cohabiting couples can be especially pertinent if one partner (usually the woman) is financially dependent, due to household maintenance and child care, or gender wage differentials. In some countries, such as the UK, the lack of legal regulation may restrict the vulnerable partner’s access to state resources that help to solve property disputes or apply for alimony (The Law Commission 2007). Even though the state may require unmarried fathers to pay child maintenance, the regulations may not be sufficient if the mother does not have access to the courts or the resources to hire a lawyer. In addition, cohabiting partners without children have no legal claim to resources, even if they contributed to the relationship, which could result in a substantial decline in living standards for the vulnerable partner (Sánchez Gassen and Perelli-Harris Reference Sánchez Gassen and Perelli-Harris2015).

Again, protections upon separation depend on whether the state has implemented registered partnerships and the degree to which the state organizes benefits around individuals or families. Registered partners in the Netherlands have many of the same rights as married partners in respect of the division of household goods, the joint home, other assets, and alimony. PACS in France have fewer regulations governing the division of household goods and assets, and no provision for alimony. Sweden and Norway regulate the division of household goods and assets for cohabiting couples, but the tax and transfer system is based on the individual. Most other European countries provide no legal guidance during separation for cohabitants, with the exception of provisos for those separating with children; for example, Germany and Switzerland require separated fathers to pay maintenance to their partners while their children are very young. Overall, this lack of regulation can make it very difficult for vulnerable cohabiting individuals to apply for maintenance or support, and as a result income may fall more after cohabitation dissolution than after divorce.

Nonetheless, it is important to remember that many individuals cohabit precisely because they want to avoid the legal jurisdiction of marriage. They may want to keep their finances and property separate, maintain their independence, and avoid bureaucratic entanglements. Previously married cohabitants may decide to remain outside the law to avoid a costly or time-consuming divorce or protect assets for their children. Given the variety of reasons for cohabiting, it is difficult to know to what extent laws should regulate cohabiting relationships, especially if people are likely to slide into relationships without knowing their responsibilities (Perelli-Harris and Sánchez Gassen Reference Perelli-Harris and Sánchez Gassen2012). In any case, it is important to keep in mind how legal and welfare systems may exacerbate the risk of disadvantage. The legal policies governing cohabitation, marriage, and separation across Europe may have implications for whether states protect vulnerable individuals from slipping further into poverty.

Culture and Religion: Universal Themes – Unique Discourses

As described above, the historical, cultural, and social context is fundamental for shaping attitudes and social norms toward family formation. Social norms are reflected in how people talk about families, and what they say about cohabitation and marriage. They also provide insights into how countries are similar or different from each other. This section draws on a cross-national collaborative project, which used focus group research to compare discourses on cohabitation and marriage in nine European countries (see Perelli-Harris and Bernardi Reference Perelli-Harris and Bernardi2015). Focus group research is not intended to produce representative data, but aims to provide substantive insights into general concepts and a better understanding of how societies view cohabitation. Collaborators conducted 7–8 focus groups in the following cities: Vienna, Austria (Berghammer, Fliegenschnee, and Schmidt Reference Berghammer, Fliegenschnee and Schmidt2014), Florence, Italy (Vignoli and Salvini Reference Vignoli and Salvini2014), Rotterdam, the Netherlands (Hiekel and Keizer Reference Hiekel and Keizer2015), Oslo, Norway (Lappegård and Noack Reference Lappegård and Noack2015), Warsaw, Poland (Mynarska, Baranowska-Rataj, and Matysiak Reference Mynarska, Baranowska-Rataj and Matysiak2014), Moscow, Russia (Isupova Reference Isupova2015), Southampton, United Kingdom (Berrington, Perelli-Harris, and Trevena Reference Berrington, Perelli-Harris and Trevena2015), and Rostock and Lubeck, Germany (Klärner Reference Klärner2015). Each focus group included 8–10 participants, with a total of 588 participants across Europe. The collaborators synthesized the results in an overview paper (Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Mynarska and Berghammer2014) and each team wrote country-specific papers, which were published in 2015 as Special Collection 17 of Demographic Research (entitled Focus on Partnerships). The results of this project are the basis for the discussion below.

The most striking finding from the focus group project was how the discourses in each country described a vivid picture of partnership formation unique to that context. In the countries with the lowest levels of cohabitation, Italy and Poland, focus group participants responded that cohabitation provides a way for couples to test their relationship, but in Poland participants tended to emphasize the unstable nature of cohabitation. In both countries, participants discussed the role of the Catholic Church, but in Italy the emphasis was more toward the tradition of marriage and family, while in Poland it was on religiosity and the heritage of the Church. In Western Germany and Austria, participants took a life-course approach to cohabitation and marriage: Cohabitation is for young adults, who are oriented toward self-fulfillment and freedom, while marriage is for later in the life course, when couples should settle down and be more responsible. Thus, marriage signifies stability, protection, and safety, especially for wives and children.

The discourses in the other countries were also unique. In the Netherlands, a recurring theme was that cohabitation was a response to the increase in divorce. Cohabitation was a way of dealing with possible relationship uncertainty, and marriage was the “complete package,” although registered partnerships or cohabitation contracts could also provide legal security. In the United Kingdom, participants expressed tolerance for alternative living arrangements, but unlike in the other countries, differences between higher and lower educated participants were more apparent. The higher educated tended to think marriage was best, especially for raising children, while the lower educated viewed cohabitation as more normative. In Russia, religion was again expressed in a different way. Orthodox Christians referred to a three-stage theory of relationships: Cohabitation is for the beginning of a relationship, registered official marriage comes soon after, and finally, when the relationship has progressed, a church wedding represents the ultimate commitment. Russian participants also discussed how cohabitation and marriage were linked to the concept of trust, which reflects the general state of a society in which individuals have difficulties trusting each other and institutions (Isupova Reference Isupova2015).

Finally, in some countries, cohabitation was much more prevalent and the focus group participants referred to cohabitation as the normative living arrangement. In Norway, cohabitation and marriage were nearly indistinguishable, especially after childbearing. Nonetheless, marriage was not eschewed altogether, and some still valued it as a symbol of commitment and love. Although marriage is increasingly postponed to later in the life course, often even after having children, it is still seen as a way to celebrate the couple’s relationship. In eastern Germany, on the other hand, marriage held very little symbolic value. The focus of relationships was more on the present rather than whether they would last into the future, and for the most part, participants in eastern Germany thought marriage was irrelevant. Klärner (Reference Klärner2015) speculates that the disinterest in marriage is due to the influence of the former socialist regime, which devalued the institution of marriage, but high levels of nonmarital fertility also have historical roots in the Prussian past (Klüsener and Goldstein Reference Klüsener and Goldstein2014), again suggesting that culture shapes behavior.

Given the unique set of discourses within each country, it is difficult to determine which specific social, economic, or legal factors influenced the responses in each country. Some general patterns emerged, for example, in countries with more similar legal rights, such as Norway, cohabitation was perceived to be mostly similar to marriage, while in countries with fewer protections for cohabitants, such as Poland, focus group participants considered cohabitation to be an unstable relationship. However, the association with legal policies was not clear-cut – for example, discourses in eastern and western Germany differed, even though both regions fall under the same marital law regime. Further, despite the lack of legal differences between de facto partnerships and marriage in Australia, many respondents still valued marriage. These cross-national observations again provide evidence that a complex array of cultural and historical factors shape family behaviors.

Despite the distinct discourses expressed across Europe, however, some common themes emerged, which suggests that cohabitation does share an underlying meaning across countries. First, participants in all countries generally saw cohabitation as a less-committed union than marriage, saying that marriage was the “ultimate commitment,” (United Kingdom), “one hundred percent commitment” (Australia), “higher quality” (Russia), or “more binding and serious” (Austria). Several distinct dimensions of marriage were revealed, for example security and stability, emotional commitment, and the expression of commitment in front of the public, friends, and family. Participants in some countries also discussed fear of commitment, especially among men, and due to the increase in divorce (see also Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Berrington, Gassen, Galezewska and Holland2017a). Although the expression of commitment through marriage was a major theme in most countries, many participants pointed out that other factors, such as owning a house or having children, were just as, if not more, important in signaling commitment. In addition, in nearly every country, a few “ideological cohabitants” argued that cohabiting couples were even more committed than married couples, because they did not need a piece of paper to prove their love. Overall, however, these individuals were in the minority, and cohabitation was seen as a less committed relationship than marriage.

Another theme which emerged throughout the focus groups was the idea that cohabitation is a testing ground allowing couples to “try out” the relationship before marriage. Testing was seen as providing the opportunity for partners to get to know each other and separate if the relationship did not work out. In some countries, participants said that cohabitation was the wise thing to do before marriage (Austria), or even mandatory (Norway), but in all countries cohabitation was recognized as a period when couples could live together as if married but (usually) experience fewer consequences if the relationship dissolved. As a corollary, cohabitation was seen as providing greater freedom than marriage, since it was a more flexible relationship. In some instances this meant that partners have greater independence from each other, for example keeping finances separate, and that they can pursue their own individual self-fulfillment – particularly appealing to women who want to escape the traditional bonds of patriarchy. Some asserted that forming a cohabiting partnership was particularly important after a bad experience with divorce. Others said that the freedom of cohabitation permitted individuals to search for new partners and leave the previous partner if a better one comes along.

The focus group discussions suggested that in most of these European countries, marriage and cohabitation continue to have distinct meanings, with marriage representing a stronger level of commitment and cohabitation a means to cope with the new reality of relationship uncertainty. Yet this uncertainty was not expressed with respect to economic uncertainty, as has often been found in US qualitative research (e.g., Gibson-Davis, Edin, and McLanahan Reference Gibson-Davis, Edin and McLanahan2005; Smock, Manning, and Porter Reference Smock, Manning and Porter2005). Although some European participants did discuss the high costs of a wedding, especially in the United Kingdom, they did not say that couples needed to achieve a certain level of economic stability in order to marry. Of course, the format of focus group research may have discouraged individuals from divulging certain reasons for not marrying, and in-depth interviews with low-income individuals may reveal different narratives, but on the whole, the focus group results suggest that the lack of marriage is not primarily about money, but more about finding a compatible partner. Thus, these focus group findings raise questions about whether cohabitation in Europe is quite different than in America, which appears to be experiencing a more extreme bifurcation of family trajectories by social class (Perelli-Harris and Lyons-Amos Reference Perelli-Harris and Lyons-Amos2016).

Consequences – Does Cohabitation Really Matter for People’s Lives?

While focus group participants often talked about marriage being a more committed and secure relationship, except in eastern Germany and, to some extent, in Norway, it is not clear whether cohabitation and marriage are truly different types of unions, and to what extent this matters for adult well-being. A large body of research has found that married people have better physical and mental health (Hughes and Waite Reference Hughes and Waite2009; Liu and Umberson Reference Liu and Umberson2008; Waite and Gallagher Reference Waite and Gallagher2000), but many of these studies compare the married and unmarried, without focusing on differences between marriage and cohabitation. Studies that do examine differences between partnership types often find mixed results (e.g., Brown Reference Brown2000; Lamb, Lee, and DeMaris Reference Lamb, Lee and DeMaris2003; Musick and Bumpass Reference Musick and Bumpass2012), still leaving open the question of whether marriage provides greater benefits than cohabitation.

On the one hand, certain aspects of cohabitation do seem to universally differ from marriage. For example, research has consistently found that, on average, cohabiting unions are more likely to dissolve than marital unions (Galezewska Reference Galezewska2016), even if they involve children (DeRose et al. Reference DeRose, Lyons-Amos, Wilcox and Huarcaya2017; Musick and Michelmore Reference Musick and Michelmore2016). Women who were cohabiting at the time of their first child also have lower second birth rates compared to married women, unless they marry shortly afterwards (Perelli-Harris Reference Perelli-Harris2014). In addition, certain characteristics are consistently negatively associated with cohabitation, for example subjective well-being (Soons and Kalmijn Reference Soons and Kalmijn2009) and relationship quality (Aarskaug Wiik, Keizer, and Lappegård Reference Wiik, Kenneth and Lappegård2012). Thus, some differences between cohabitation and marriage do indeed seem to be universal across countries.

Nonetheless, it is important to keep in mind that many quantitative studies present average associations that do not reflect the heterogeneity of cohabitation or the potential progression of relationships. As discussed above, cohabitation is an inherently more tenuous type of relationship, and many couples use this period of living together to test their relationships. While some of these couples break up, and some eventually marry, many others will live in long-term unions similar to marriage, but without official recognition. Many of these cohabiting relationships can be nearly identical to marriage, providing similar levels of intimacy, emotional support, care, and social networks, as well as benefiting from shared households and economies of scale. Studies of commitment (Duncan and Philips Reference Duncan, Phillips and Park2008) and the pooling of financial resources (Lyngstad, Noack, and Tufte Reference Lyngstad, Noack and Tufte2010) indicate that over time, couples in cohabiting relationships often make greater investments in their relationships, resulting in smaller differences between cohabitation and marriage. Thus, cohabiting relationships have the potential to be identical to marriage, just without “the piece of paper.”

A second key issue that may account for observed differences by relationship type is selection, which posits that different outcomes are not due to the effects of relationship type per se, but instead, the characteristics of the people who choose to be in that type of partnership. As discussed in Chapter 1, many studies find that cohabitants often come from disadvantaged backgrounds, for example their parents had lower levels of education or income (Aarskaug Wiik Reference Wiik2009; Berrington and Diamond Reference Berrington and Diamond2000; Mooyart and Liefbroer Reference Mooyaart and Liefbroer2016) and might have experienced divorce (Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Berrington, Gassen, Galezewska and Holland2017a). Selection mechanisms often persist into adulthood, for example men who are unemployed or have temporary jobs are more likely to choose cohabitation (Kalmijn Reference Kalmijn2011), and women with lower educational attainment are more likely to give birth in cohabitation than women with higher educational attainment (Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Kreyenfeld and Kubisch2010). Studies using causal modeling techniques to control for individual characteristics demonstrate that the union type itself does not matter for well-being; instead, the characteristics which lead to poor outcomes also lead people to cohabit rather than marry (Musick and Bumpass Reference Musick and Bumpass2012; Perelli-Harris and Styrc Reference Perelli-Harris and Styrc2018). Thus, although further research is needed to ensure a lack of causality, existing studies suggest that marriage does not itself provide benefits over and above cohabitation, given that the union remains intact. This is very important to note, given the common perception that cohabiting couples are less committed than married couples.

Again, however, cultural, social, policy, and economic context may be very important for shaping these interrelationships. Local and national context may attenuate differences between cohabitation and marriage in some countries but not in others. Social and cultural norms may reduce differences between the two relationship types if cohabitation is normalized with few social sanctions, or widen the gap if marriage is given preferential treatment or accorded a special status. We would expect few differences in behavior or outcomes in the Nordic countries, where cohabitation is widespread (Lappegård and Noack Reference Lappegård and Noack2015), but we would expect substantial differences in the United States where marriage tends to be accorded a higher social status (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2014).

The legal and welfare state system may also reduce or exacerbate differences. Legal regimes which recognize cohabitation as an alternative to marriage may provide protections that produce a stabilizing effect for all couples, thereby reducing differences in well-being. On the other hand, systems which privilege marriage – for example, with tax incentives promoting a marital breadwinner model – may result in greater benefits to well-being for marriage than cohabitation. Welfare states that provide benefits only to low-income single mothers may also discourage marriage, and even cohabitation, if benefits depend on the income of all adult household members (Michelmore Reference Michelmore2016). Finally, selection effects can differ across countries, with cohabitation primarily practiced by disadvantaged groups in some countries, or practiced by all strata in others.

Given that countries differ by social, legal, economic and selection effect context, the different meanings of cohabitation may result in differential outcomes across countries. To test this hypothesis, I led a project to examine the consequences of new family arrangements in settings representing different welfare regimes and cultural contexts: Australia, Norway, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The team systematically analyzed a range of partnership and childbearing behaviors, with a specific focus on outcomes in mid-life – around ages 40–50, depending on the survey – after the period of early adulthood relationship “churning” and most childbearing. The outcomes included mental well-being (Perelli-Harris and Styrc Reference Perelli-Harris and Styrc2018), health (Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Styrc and Addo2017b; Sassler et al. Reference Sassler, Addo and Lappegård2016), life satisfaction (Hoherz et al. Reference Hoherz, Perelli-Harris, Styrc, Lappegård and Evans2017), and wage differentials (Addo et al. Reference Addo, Perelli-Harris, Hoherz, Lappegård and Sassler2017). The team used a variety of retrospective and longitudinal studies, and one of the key concerns of the project was to address selection, which could explain the positive relationship between marriage and outcomes but differ across countries. We used a variety of methods, but primarily propensity score matching or propensity weighted regression, which allowed us to test whether those who did not marry would have been better off if they did marry.

Figure 4.4 shows the mean values and confidence intervals for three outcomes: Self-rated health, life satisfaction, and hourly wage in the local currency. The confidence intervals in bold indicate that the modeling approaches described above were unable to eliminate significant differences between married and cohabiting men and women. The results immediately confirm our main hypothesis: The benefits of marriage relative to cohabitation differ across countries, suggesting that context can shape the meanings and consequences of different partnership types. Before including controls, the confidence intervals indicate that married people have significantly better outcomes in the United Kingdom and United States with respect to self-rated health and hourly wages, and in the United Kingdom with respect to life satisfaction (the United States was not included in the life satisfaction study, and Australia was not included in the wage study). Differences in outcomes by relationship type were not as pronounced in Australia, Norway, and Germany, although cohabiting men in Norway did have significantly different wages from married men, and cohabiting men in Australia and women in Norway had significantly different mean life satisfaction from married individuals.

Figure 4.4 Mean values and confidence intervals for outcome variables in selected countries

Once we controlled for different aspects of the union, for example union duration and prior union dissolution, the differences between marriage and cohabitation in health, life satisfaction, and wages were reduced substantially in most studies. This finding suggests that one of the reasons we see differences between cohabitation and marriage is because cohabiting unions are often a testing ground and more likely to dissolve, or they are more commonly chosen as a second union. Cohabiting unions are also less likely to have children together, and controlling for children eliminated many of the differences between cohabitation and marriage. However, one of the main reasons for differences between cohabitation and marriage in mid-life is due to selection mechanisms from childhood, such as parental SES and divorce. After including these indicators in our models, differences by partnership type were reduced substantially and eliminated in the United States. However, some puzzling exceptions remained after including controls: British cohabiting men continued to have worse self-rated health than married men, and both British men and women who were cohabiting continued to have worse life satisfaction than their married counterparts. British married women continued to have slightly higher wages than British cohabiting women. Nonetheless, despite including a large battery of control variables, we suspect that other forms of selection still might account for any effects. Overall, the results suggest that taking into account the heterogeneity of cohabiting unions (as measured by union duration and having children together) as well as selection mechanisms from childhood can explain most of the marital benefits to well-being, but country context, such as welfare state regime and social norms, also matters. Thus, it is important to keep these factors in mind when assessing the extent to which the emergence of cohabitation itself is detrimental to adult well-being; in many places, simply forming a lasting partnership seems to be most important.

Conclusion

Throughout this chapter, I have grappled with the idea that some processes of social change are universal and others are still shaped and reinforced by country-specific factors. I have primarily focused on one of the greatest new developments in the family over the past few decades – the emergence of cohabitation – which has challenged conventional expectations that individuals enter into a lifelong union recognized by law and society. Many people have been alarmed by this development, especially because studies indicate that rates of union dissolution are higher among cohabitants than married couples, and that cohabitation is often associated with disadvantage or low subjective well-being. However, many studies mask the heterogeneity in cohabiting couples and therefore make assumptions about cohabitation that may not be accurate, especially across different settings. In this conclusion, I will briefly summarize and reflect on the different types of heterogeneity which are important to think about when considering whether emerging forms of family behavior, such as cohabitation and nonmarital fertility, are producing and reproducing disadvantage, or whether the behaviors are simply a product of new social realities and shifting norms.

First, countries are diverse and reflect heterogeneous patterns of change. Some countries have experienced rapid increases in cohabitation and nonmarital fertility, while others have not. The variation in family behaviors across Europe reflects different cultural, social, political and economic path dependencies, and the explanations for change cannot be boiled down to one factor. The nonmarital childbearing maps show that sometimes laws and policies can produce differences in behaviors that are distinctly demarcated at state borders, while sometimes religious and cultural factors create pockets of behaviors that stretch across state borders. The discourses from the focus groups also suggest that culture and religion continue to echo in social norms today. Thus, while some general explanations may be similar, we cannot assume that all countries are experiencing the same changes in the family for the same underlying reasons, or that the family change will have the same consequences in the long run.

Second, within countries, we see heterogeneous responses to social change, with some strata of society experiencing increases in new behaviors and other strata not. On the one hand, cohabitation and increases in nonmarital fertility are occurring across all educational levels in most European countries (Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Kreyenfeld and Kubisch2010). In many countries, cohabitation is becoming a normative way to start a relationship, regardless of educational level, and as a way to test that the relationship is strong enough for marriage. Yet transitions to marriage after the relationship is formed, especially before and after the birth of the first child, may be particularly important for producing inequalities. Across Europe, higher educated individuals are more likely to marry before a birth (Mikolai et al. 2016), and lower educated individuals are more likely to separate after a birth (Musick and Michelmore Reference Musick and Michelmore2016). These findings suggest that different groups may be responding in different ways to new behaviors, potentially leading to “diverging destinies” between the most and least educated (McLanahan Reference McLanahan2004). Thus, social change can influence different groups of people in different ways, and it is important to continue to recognize these heterogeneous responses.

Third, the meanings of cohabitation and marriage can change across the life course, and even throughout relationships. Individuals’ values and ideas undergo a process of development as they age and transition throughout different life stages, and this may result in shifting perceptions of cohabitation and marriage as they grow older. As the Austrian focus groups highlighted, people often think that cohabitation is ideal when individuals are young and free, but marriage is best when individuals are more mature and ready to take on more responsibilities, for example childbearing. This evolution of the importance of marriage may especially be embedded in cultures that perceive marriage to signify stability and security. On the other hand, the purpose and meaning of cohabitation may change as relationships progress. At the beginning of a relationship, cohabitation may be a desirable alternative to living apart and a testing ground to see if the relationship is secure, but as the partners become more committed, sharing a home and investing in a long-term relationship may be just as significant as an official marriage certificate. Thus, both cohabitation and marriage are imbued with multiple meanings that can change across multidimensional life courses linked to other life domains (Perelli-Harris and Bernardi Reference Perelli-Harris and Bernardi2015).

To reiterate, these different types of heterogeneity are essential to keep in mind when considering the association between partnership formation and inequality. The great complexity across settings, couples, and individuals creates challenges for understanding how family change is exacerbating or reinforcing inequalities. While some studies have begun to investigate to what extent family structure is responsible (or not) for increasing inequality (Bernardi and Boertien Reference Bernardi and Boertien2017a; Härkönen Reference Juho, Nieuwenhuis and Maldonado2018), far more research is needed to understand these complex relationships, especially in different contexts.