Introduction

There is a longstanding consensus that civil society and interest organizations are weak and underdeveloped in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) due to lasting legacies of civic oppression (Howard, Reference Howard2003; Borragán, Reference Borragán2004; Ekiert and Foa, Reference Ekiert and Foa2011). Under communism, associational life was essentially governed by the party state. Although these regimes promoted some civic organizations, for example sport and youth associations, participation was generally state-regulated and mandatory, while organizational leadership had little leeway to autonomously focus on organizational development.

Yet despite their historical weakness, civic organizations seeking confrontation with communist regimes ultimately became key actors in bringing down communism. The Polish anticommunist opposition was fueled by the Solidarność workers’ movement. In Czechoslovakia and Hungary, civic groups consisting of academics, students, and common citizens allied with trade unions pushing to subvert communist rule. Paradoxically though, civic organizations were again largely marginalized after 1989–90, as the socioeconomic transformation process was generally spearheaded by technocratically operating executives (Dimitrov et al., Reference Dimitrov, Goetz and Wollmann2006). Hence, scholars have argued that the prevalence of strong executives (Zubek, Reference Zubek2005) – compounded by the existence of private clientelistic networks (Pleines, Reference Pleines2004) and wide-spread apathy towards the political process (Pop-Eleches and Tucker, Reference Pop-Eleches and Tucker2011; Kostelka, Reference Kostelka2014) – have created unfavorable playing fields for organized interests. This is compounded by the collapse of workers’ unions during the 1990s (Ost, Reference Ost2011; Kostelka, Reference Kostelka2014).

However, there has been a recent boom in analyses of organized interests in the region. Scholars have covered, among other things, population ecologies (Labanino et al., Reference Labanino, Dobbins, Czarnecki and Železnik2021; Rozbicka and Kamiński, Reference Rozbicka and Kamiński2021) and advocacy strategies (Rozbicka et al., Reference Rozbicka, Kamiński, Novak and Jankauskaitė2020; Czarnecki, Reference Czarnecki, Dobbins and Riedel2021), while also exploring state-interest group interactions (Ost, Reference Ost2011; Olejnik, Reference Olejnik2020; Dobbins and Riedel, Reference Dobbins and Riedel2021) and lobbying regimes (Vargovčíková, Reference Vargovčíková2017; Rozbicka et al., Reference Rozbicka, Kamiński, Novak and Jankauskaitė2020). Most recently, observers have also produced studies on the concrete impact of organized interests on policymaking (Horváthová and Dobbins, Reference Horváthová and Dobbins2019; Rozbicka et al., Reference Rozbicka, Kamiński, Novak and Jankauskaitė2020).

While we have learned more about the environments in which CEE interest groups operate, we still know little about their internal development. The article addresses this research gap by exploring the determinants of interest group professionalization in CEE, based on an original survey of 428 Czech, Hungarian, Polish, and Slovenian healthcare, higher education, and energy policy groups active at the national level. Our research question is straightforward: what are the main drivers of organizational professionalization in the post-communist region? Building on pre-existing studies of organizational professionalization, we explore how three bundles of distinct factors – funding sources, interorganizational cooperation, and (organizations’ standing in) the domestic interest group system – affect the intensity of organizational professionalization.

We first provide a historical overview of organized interests in CEE, before discussing the state-of-the-art and conceptualizing professionalization. In Section 3, we outline our theoretical framework, which places a stronger emphasis on the domestic drivers of professionalization than previous studies (Klüver and Saurugger, Reference Klüver and Saurugger2013; Maloney et al., Reference Maloney, Hafner-Fink and Fink-Hafner2018; Czarnecki and Riedel, Reference Czarnecki, Riedel, Dobbins and Riedel2021), before discussing our new dataset and methodological approach in Section 4. Section 5 showcases our statistical analyses, and in Section 6, we propose a roadmap for future research.

Contextual background and state-of-the art

It is frequently argued that interest groups face formidable pressures to professionalize their activities. The professionalization of lobbying skills enables organizations to more effectively cater to members’ interests and gain access to decision-makers (Beyers, Reference Beyers2004). The training and deployment of lobbyists, the creation of internal monitoring systems, and accumulation of specialized knowledge can be seen as key investments in the viability and political clout of organizations. Hence, they have strong incentives to professionalize in order to enhance their advocacy capacities and position in policymaking (Albareda, Reference Albareda2020). In particular in new democracies, organizational professionalization can potentially be seen as an additional key to democratization, as the more professionalized organizations are, the more effectively they can interact with policymakers in the interest of constituents. Hence, professionalized organizations may ultimately fortify the linkages between decision-makers and various segments of civil society, that is the members of organizations and others benefiting from the collective goods they produce. Organizational professionalization may also facilitate the transmission of input and expertise ‘from below’ to policymakers.

Seen critically though, organizations with highly professionalized lobbying staff may also become detached from their member base (Hwang and Powell, Reference Hwang and Powell2009; Heylen et al., Reference Heylen, Willem and Beyers2020), potentially resulting in declining membership. While professionalization is generally seen as being correlated with better access to policymakers (Albareda, Reference Albareda2020), it need not automatically enhance the democratic quality of organizations, as tedious consultations and consensus building with members may be cumbersome to efficient lobbying (Grömping and Halpin, Reference Grömping and Halpin2019).Footnote 1

In either case, the question of professionalization is particularly interesting in the postcommunist context. Although it is shortsighted to speak of a complete tabula rasa for organized interests after 1989 (Labanino et al., Reference Labanino, Dobbins, Riedel, Dobbins and Riedel2021), their playing field has radically changed. Postcommunist democracies faced unparalleled challenges in establishing effective institutions of political representation to channel civic demands into policymaking. A substantial growth in organizational foundations occurred, in particular during the democratization and EU accession process (Dobbins and Riedel, Reference Dobbins and Riedel2021). Reform-oriented governments have also aimed to promote social dialogue, appear more responsive to citizens and manage social divisions by establishing new platforms for formal consultations with interest groups (Ost, Reference Ost2000).

Altogether, democratization transformed the linkages between organized associations and the state, resulting in unprecedented new opportunities for organizations to develop. Unlike under communism, where interest intermediation was channeled through the state and party bureaucracy, CEE interest groups now operate within parliaments, ministries, and new interest intermediation forums, while also fostering ties with governments, oppositional parties, and like-minded partner organizations. They are free to calibrate their strategies to members’ needs, consolidate ties with rivaling groups, or actively lobby the public outside formal political channels. Thus, there are strong reasons to assume that CEE interest groups are dedicating greater energy to the professionalization of their internal operations and strategic activities.

Professionalization of interest groups in CEE and beyond

Professionalization is a relatively marginalized area of interest group research, as most studies shy away from exploring the internal workings of individual groups due to enormous methodological challenges. In addition, the term professionalization is used somewhat elusively. For example, some authors explore how grassroots movements evolve into formal professional organizations (e.g., van Deth and Maloney, Reference van Deth and Maloney2012). Other studies analyze the lobbying profession from a sociological perspective. Under the banner of ‘learning to lobby’, there is a large strand of research dealing with the personal qualities and identities of lobbyists (e.g., Coen and Richardson, Reference Coen and Richardson2009; Holyoke et al., Reference Holyoke, Brown and LaPira2015). Diverse researchers have looked at how lobbyists gather expertise and cultivate political ties (e.g., Groß and Kieser, Reference Groß and Kieser2006; McGrath, Reference McGrath2015). Another strand of research explores professionalization as an independent variable by testing how organizational professionalization impacts membership and political influence (e.g., Hollman, Reference Hollman2018; Heylen et al., Reference Heylen, Willem and Beyers2020).

Yet how exactly do we conceptualize professionalization and what has the existing literature taught us? According to Imig and Tarrow (Reference Imig and Tarrow2001), professionalization is a process of transformation of internal structures of organized interests. This entails the creation of a professional workforce and culture, in which specialized knowledge is applied to respond to social problems. Professionalizing organizations thus aim to enhance the skills of their members through formal training, the development of monitoring and benchmarking systems, and more systematic reflection on organizational strategy. Hence, both ‘operational’ and ‘expert knowledge’ is necessary (Carmin, Reference Carmin2010: 187), which is usually ‘acquired through the professional training of lobbyists’ (Staggenborg, Reference Staggenborg1988; McGrath, Reference McGrath2005: 125).

So far, only a few studies comparatively explore the driving forces behind the internal development of interest groups, most of them covering only a few cases (e.g., Greenwood, Reference Greenwood2002; Maloney, Reference Maloney, Kohler-Koch, Bièvre and Maloney2008; Saurugger, Reference Saurugger2012; Fraussen, Reference Fraussen2014). However, more recent studies by Klüver and Saurugger (Reference Klüver and Saurugger2013), Maloney et al. (Reference Maloney, Hafner-Fink and Fink-Hafner2018), and Czarnecki and Riedel (Reference Czarnecki, Riedel, Dobbins and Riedel2021) have significantly advanced research. Klüver and Saurugger (Reference Klüver and Saurugger2013) explore whether the professionalization of EU-level interest groups differs across group type. Accordingly, ‘cause groups’ often aim to transition from volunteer-based organizations towards organizations with a professional workforce. However, mainly focused on protest, they often lack fixed bureaucratic structures and routines. This makes them more susceptible to internal divisions and demobilization. They argue that sectional or business-oriented groups are more focused on members’ special interests that generate concentrated costs and benefits, which in turn materially affect their supporters (Klüver and Saurugger, Reference Klüver and Saurugger2013). Generally, such groups can better monitor and mobilize their members and manage internal divisions. Moreover, as sectional groups primarily pursue insider lobbying (Binderkrantz et al., Reference Binderkrantz, Christiansen and Pedersen2015), they may need to hire professionalized lobbyists and effectively monitor their success. Yet Klüver and Saurugger find no significant differences across group type, rather that financial endowment explains (at least a small share of) the variation in professionalization levels.

Czarnecki and Riedel (Reference Czarnecki, Riedel, Dobbins and Riedel2021) engage more systematically with Europeanization processes, conceptualized as both formal umbrella organization membership and more informal ties with like-minded organizations from other European countries as drivers for the professionalization of CEE interest groups. They find that it is not membership in supranational umbrella organizations or funding from EU-level interest organizations that necessarily lead to professionalization, rather, to a much greater extent, strong informal ties with organizations from other European countries pursuing similar objectives. Their findings somewhat contradict those of a panel-based study by Maloney et al. (Reference Maloney, Hafner-Fink and Fink-Hafner2018) which identifies EU funds as a key driver of professionalization of approximately 50 Slovenian interest organizations.

However, we argue that these studies only paint a partial picture of the dynamics driving organizational professionalization and – despite their laudable advancements – perhaps insufficiently grasp the multiple international, domestic, and organization-specific catalysts for professionalization.

Theory, hypotheses, and variables

Our analysis advances preexisting research by integrating a more differentiated scope of potential determinants of professionalization and weighing their specific impacts against one another. We contend that three bundles of factors – organizational funding sources, interorganizational cooperation, and (organizations’ standing in) national interest group systems – may be decisive. Our framework is based on our conviction that there are numerous potential pathways towards professionalization. Specifically, professionalization may be driven not only by ‘hard’ (i.e., monetary resources), but also ‘soft’ factors (i.e., interorganizational communication and learning) as well as the competitive environments in which organizations operate at the national level. In the following, we present our tri-dimensional framework, which builds on, but also adds new twists to preexisting analyses of the determinants of organizational professionalization (e.g., Maloney et al., Reference Maloney, Hafner-Fink and Fink-Hafner2018; Czarnecki and Riedel, Reference Czarnecki, Riedel, Dobbins and Riedel2021).

Organizational funding sources

First, it is intuitive that organizations require resources to professionalize (Baumgartner, Reference Baumgartner2009). Greater financial means allow groups to hire experts or invest in expertise accumulation, which can be used to lobby politicians. As highlighted above, Klüver and Saurugger (Reference Klüver and Saurugger2013) determined that organizational resources are much more definitive for professionalization than organizational age, size, or type.

Yet not merely organizational resources per se, rather the source of funding may be decisive. Maloney et al. (Reference Maloney, Hafner-Fink and Fink-Hafner2018) contend that another important factor for professionalization processes is public funding. Governments may effectively mandate groups to adopt specific organizational structures. As Czarnecki and Riedel (Reference Czarnecki, Riedel, Dobbins and Riedel2021: 201) argue: ‘public funding…may simply demand professionalization’, as government subsidies may not only offer organizations a key resource-related advantage over non-subsidized groups, but also may require interest groups to adopt specific modes of operation or internal standards (see also Fraussen, Reference Fraussen2014).

In the same vein, EU funds may be an additional catalyst for organizational professionalization. Generally, such funds are managed and distributed by member state governments themselves (Nicolaides, Reference Nicolaides2018), thus constituting a special form of government subsidies. In fact, Crepaz and Hanegraaff (Reference Crepaz and Hanegraaff2020) argue that many interest organizations would cease to exist without EU funding. Regarding CEE, Císař and Vráblíková (Reference Císař and Vráblíková2010) showed that Czech interest groups receiving EU funds operate with significantly larger budgets, hire more staff, and develop their management structures, a finding echoed by Maloney et al. (Reference Maloney, Hafner-Fink and Fink-Hafner2018) for Slovenian interest groups and Guasti (Reference Guasti2016) for NGOs in CEE in general.

Hypothesis 1a: Organizations receiving subsidies from their own governments are more likely to professionalize.

Hypothesis 1b: Organizations receiving EU funds are more likely to professionalize.

Interorganizational cooperation

Besides potential new funding sources, EU accession has reshaped the playing field for CEE interest groups. The accession process brought about new national-level organized interests aiming to impact the negotiation process. Increasing ties with like-minded western organizations and EU-level advocacy groups may have triggered processes of networking, learning, and diffusion, as EU and western organizations have provided substantial logistic and strategic support for various CEE civic organizations (Carmin, Reference Carmin2010; Guasti, Reference Guasti2016; Fagan and Kopecký, Reference Fagan and Kopecký2017; Vándor et al., Reference Vándor, Traxler, Millner and Meyer2017).

Along these lines, European and international networking and cooperation between organizations may also function as a catalyst for organizational isomorphism, in particular mimetic isomorphism (DiMaggio and Powell, Reference DiMaggio, Powell, Powell and DiMaggio1991). It is frequently argued that organizations seeking to secure their survival align themselves with structures perceived as successful and legitimate in their organizational environment. This is particularly relevant for CEE organizations, which historically suffer from numerous weaknesses in interest articulation, such as the frequent lack of clear strategies, skills, and organization, a lacking representative character and often underdeveloped channels for interest intermediation (Borragán, Reference Borragán2001: 64–67). The intensification of ties with western counterparts may prompt CEE organizations to mimic the structures and processes of foreign organizations perceived as ‘more professional’, which in turn may enable them to overcome their structural weaknesses.

Of particular significance in this regard are international umbrella organizations. Whether situated at the EU level or beyond, umbrella organizations bundle the interests of national-level members, enable national organizations to participate in transnational policymaking, and represent their interests internationally. As Eising (Reference Eising2016) shows, EU umbrella organizations provide member associations crucial information on EU policies and thus function as ‘middle-men’ between the national and supranational level. In line with hypothesis 1b, the proximity to EU institutions may also facilitate organizations’ access to project funding. For example, Hanegraaff and van der Ploeg (Reference Hanegraaff and van der Ploeg2020) found that EU umbrella membership boosts the financial and professional resources of domestic groups, while also increasing access to EU-level institutions. Going beyond this, we argue that EU umbrella organizations may provide the additional long-term benefit of being an arena for the isomorphic emulation of organizational strategies perceived as successful (DiMaggio and Powell, Reference DiMaggio, Powell, Powell and DiMaggio1991). Yet it is also equally plausible that transnational synergetic effects take place outside umbrella organizations and instead be stimulated by alternative forms of interactions such as bilateral expertise-sharing, coordination, and/or involvement in epistemic policy communities (Haas, Reference Haas1992).

Hypothesis 2a: Organizations which are members of European/international umbrella organizations are more likely to professionalize.

Hypothesis 2b: Organizations which network with like-minded European/international organizations are more likely to professionalize.

However, this transnational perspective potentially overlooks the fact that organizations ultimately operate foremost in national ecosystems and may equally benefit from interactions with like-minded domestic organizations. Recently, the interest group literature has shed light on interorganizational cooperation as a key determinant of lobbying success. Junk (Reference Junk2019), for example, shows that lobbying coalition diversity may signal broad social support for legislation, while a recent analysis of healthcare organizations by Horváthová and Dobbins (Reference Horváthová, Dobbins, Dobbins and Riedel2021) reveals that cooperation between groups significantly enhances access to parliaments and governing parties. Yet national interorganizational cooperation may offer additional benefits to organizations regarding their internal development. While scholars have written extensively on the impact of transnational communication on policy emulation and convergence (e.g., Knill, Reference Knill2005), we contend that national-level interorganizational cooperation may equally unleash isomorphic effects. Tight synergies with like-minded domestic groups, that is when coordinating strategies or sitting jointly on advisory boards, may make organizations increasingly aware of their own weaknesses, promote the share of expertise, experiences, and personnel, and subsequently unleash mutual mimetic and learning effects.

Hypothesis 3a: Organizations that are members of national umbrellas are more likely to professionalize.

Hypothesis 3b: Organizations that closely cooperate with like-minded national-level organizations are more likely to professionalize.

Self-critically, we could also argue that professionalization itself (i.e., time, staff, and resources) is a precondition for interorganizational cooperation, hence raising issues of causality. Nevertheless, we assume – in line with mimetic isomorphism – that national organizational ecosystems generally comprise various more professionalized organizations which ‘weaker’ organizations aspire to cooperate with, learn from, and emulate, hence ultimately boosting their professionalization.

Organizations’ standing in the domestic interest group system: competition and ‘insiderness’

Previous accounts of organizational professionalization also arguably overlook the domestic lobbying context. While the stringency of lobbying laws may affect professionalization (see Rozbicka et al., Reference Rozbicka, Kamiński, Novak and Jankauskaitė2020), we argue, more broadly, that the competitive environments in which they operate may be an equally crucial determinant. In simple terms, organizations find themselves in a permanent struggle with other organizations for members, resources, and access to policymakers. As Hannan and Carroll (Reference Hannan and Carroll1992) maintain in their seminal analysis of organizational ecology, as organizational density grows, the ‘supplies of potential organizers, members, patrons, and resources become exhausted’. In other words, the more organizations operating in a specific area, the greater the interorganizational competition. High organizational densities also limit interest groups’ access to policymakers (Hanegraaff et al., Reference Hanegraaff, van der Ploeg and Berkhout2020). We argue that the competitive environment may reverberate at the level of organizations (see Berkhout et al., Reference Berkhout, Hanegraaff and Maloney2021 for a recent study), as the quest for survival in dense environments and heavy competition from rivaling organizations may prompt them to optimize their structures and operations.

Hypothesis 4: Organizations that perceive stronger organizational density are more likely to professionalize.

Finally, we contend that insider status in the national interest group system may be a crucial predictor of professionalization. We follow Fraussen’s (Reference Fraussen2014) argument that institutionalized interactions with public authorities may fuel organizational development, regardless whether these result from corporatist-style arrangements or less formally systematized interchanges. In an analysis of a Flemish environmental organization, he shows that its involvement in policy formulation and/or implementation enabled it to accrue material and immaterial resources to further invest in its internal development. Along these lines, professionalization may also be driven by the accumulation of expertise through intensive, state-interest group interactions, in particular, when organized interests participate in advisory boards. While it cannot be ruled out that exclusion from policymaking may also prompt groups to recalibrate their strategies (see e.g., Beyers and Kerremans, Reference Beyers and Kerremans2012), we argue in line with Fraussen (Reference Fraussen2014) that ‘insiderness’ is more likely to be a catalyst for professionalization.

Hypothesis 5: Organizations that perceive strong coordination with the state are more likely to professionalize.

Data and methods

Between February 2019 and June 2020, we conducted an online survey of national-level interest groups in healthcare, energy, and higher education policy in Czechia, Hungary, Poland, and Slovenia. The policy areas represent large portions of public budgets and are key to the long-term well-being of nations. Moreover, they are not interrelated, thus providing solid foundations for general insights. The country selection is motivated by their broader similarity (e.g., postcommunist democracies, new market economies, EU members), but also by diversity regarding three decisive characteristics for interest group politics: election funding, lobbying regulations, and the level of political-economic coordination/corporatism. Czechia has a very liberal economy with privately funded elections and weaker lobbying regulations (McGrath, 2008; Šimral et al., Reference McGrath2015). It is ranked low in classifications of corporatism (e.g., Jahn, Reference Jahn2016). Poland also is a relatively weakly coordinated market economy and generally ranked lower on the corporatism dimension (Jahn, Reference Jahn2016). However, elections are publicly funded, and extensive lobbying regulations and reporting requirements exist – despite various loopholes (Kwiatkowski, Reference Kwiatkowski2016; Rozbicka et al., Reference Rozbicka, Kamiński, Novak and Jankauskaitė2020). Hungary exhibits stronger market coordination (Duman and Kureková, Reference Duman and Kureková2012; Tarlea, Reference Tarlea2017), whereby elections are publicly funded and lobbying activities – at least formally – tightly monitored, but since 2010 only loosely regulated (Laboutková et al., Reference Laboutková, Šimral, Vymětal, Laboutková, Šimral and Vymětal2020; European Commission, 2020). Slovenia is the most coordinated and corporatist market economy in CEE (Bohle and Greskovits, Reference Bohle and Greskovits2012; Jahn, Reference Jahn2016). Regulatory controls over lobbying, party funding, and electoral campaigns are comparatively weak (despite heavier coordination by the 2010 anticorruption law, hence providing a polar opposite case to Poland, see Rozbicka et al., Reference Rozbicka, Kamiński, Novak and Jankauskaitė2020).

Before carrying out our standardized survey, we compiled datasets of ‘population ecologies’ of all interest groups operating in the three policy areas and four countries. The main sources were national online registries for civil society organizations. We used a harmonized set of keywords for each language and filtered out regional-level organizations and companies listed in the registries.Footnote 2

Our survey first requested information on membership structures (e.g., employees, volunteers, member firms, individual members, etc.). We then asked each organization about affiliations with European, international, and national umbrella organizations. Additional questions addressed the frequency of consultations between interest groups, parties, and governments, generally on a 1–5 scale (never, biannually, annually, monthly, weekly). We also asked about the perceived level of political coordination on 1–5 scales.

The third segment focused specifically on professionalization-related activities such as the training of lobbyists, fundraising, strategic planning, and human resource development. It also included questions about financial sources and financial stability. We received responses from 428 CEE interest organizations with an overall response rate of 33.9% (see online appendix).

Construction of variables

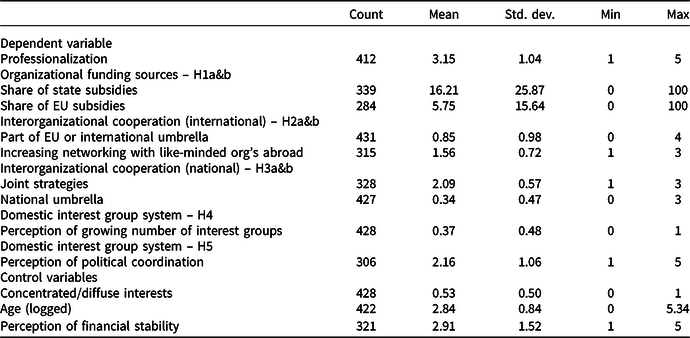

Instead of reinventing the wheel, we largely align our definition of professionalization with preexisting conceptualizations, in particular Imig and Tarrow (Reference Imig and Tarrow2001) and Klüver and Saurugger (Reference Klüver and Saurugger2013). We conceive professionalization as a process through which organized interests hire professionalized staff, ideally with special training (see also Heylen et al., Reference Heylen, Willem and Beyers2020) with the aim of creating a professional workforce (McGrath, Reference McGrath2005). This, in turn, enables them to focus on their strategic orientation and reflect more systematically on their short- and long-term operations, while evolving into responsive organizations. Besides a stronger focus on financial stability (e.g., through increased fundraising activities), another key dimension of professionalization is the accumulation of expert knowledge pertaining to both internal organizational operations as well as technical issues the organization deals with (see Carmin, Reference Carmin2010; Albareda, Reference Albareda2020). Finally, and importantly, professionalized organizations are generally equipped with mechanisms to monitor the effectiveness of their operations.Footnote 3 Table 1 provides an overview of all variables.

Table 1. Summary statistics

Notes: Coding of professionalization: composite variable based on the row mean of focus on organizational development, human resources development, fundraising, evaluation of efficiency, and effectiveness as well as strategic planning (each measured on a scale 1–5 where 1 = much less than 10–15 years ago, 2 = less, 3 = same as before, 4 = more, 5 = much more than before) and the variable staff (scale 1–5 representing 5 quantiles based on the total amount of staff). Coding of state subsidies, EU subsidies: indicated as share of budget in percentages. Coding for membership in European and/or international umbrella: 0 = no member, 1 = member in either one European or one international umbrella, 2 = member in either multiple European and/or international umbrellas, 3 = member in either one/multiple European and/or one/multiple international umbrellas, 4 = member in multiple European and international umbrellas. Coding of networking w. like-minded organizations: 1 = no, 2 = somewhat, 3 = very much. Coding of joint strategies: composite variable based on the row mean of cooperation in joint statements, joint political strategies, in representation on advisory boards (each measured on a scale 1 = never, 2 = occasionally, 3 = frequently). Coding of national umbrella: 0 = not part of national umbrella; 1 = part of national umbrella. Coding of the perception of growing number of interest groups: 0 = not growing, 1 = growing. Coding of perception of political coordination: 1 = very weak, 2 = weak, 3 = moderate, 4 = strong, 5 = very strong. Coding of concentrated/diffuse: 0 = diffuse, 1 = concentrated. Coding of age: age as of 2020 transformed into a logarithmic scale. Coding of perception of financial stability: 1 = stable for less than 1 year, 2 = stable for 1–2 years, 3 = stable for 3–5 years, 4 = stable for about 5 years, 5 = stable for more than 5 years. Source: own data and own elaboration.

In line with this broader understanding of professionalization, we took two steps to construct our dependent variable – organizational professionalization. First, we calculated the organization-specific mean score of five variables reflecting increasing professionalization processes: organizational and human resources development, fundraising, strategic planning, and evaluation of efficiency and effectiveness. The wording (i.e., increased) is rooted in our strong assumption that CEE organizations were largely unprofessionalized approximately 15 years ago due to lacking traditions of organized lobbying and the dominant position of national executives in policymaking (Goetz and Wollmann, Reference Goetz and Wollmann2001).Footnote 4

To what extent does your organization focus on the following activities as opposed to 10–15 years ago (or since its founding, if founded more recently)? (1) organizational development; (2) human resources development; (3) fundraising; (4) strategic planning; and (5) evaluation of efficiency and effectiveness (scaled 1–5, see Table 1).Footnote 5

Similarly to Klüver and Saurugger (Reference Klüver and Saurugger2013), we included staff in our composite variable of professionalization, as we believe having lobbying staff significantly reflects organizational development. This aspect is supported by other studies which emphasize hiring professionalized staff, ideally with special training, as a key fundament of professionalization (e.g., Heylen et al., Reference Heylen, Willem and Beyers2020).

Due to the extreme spread of staff numbers spanning from 0 to nearly 6000, we opted for a categorical variable (1–5) based on quintiles. Our aggregate variable for organizational professionalizationFootnote 6 is thus constructed as the mean of the above-mentioned variables and a categorical variable for staff scaled 1–5.Footnote 7

Independent variables

We collected organization-specific data on the share (0/100) of government subsidies (H1a) and EU funds (H1b). EU funds are generally granted to national governments, which allocate them to specific organizations (Nicolaides, Reference Nicolaides2018). This makes a clear-cut distinction of funding sources difficult. Nevertheless, our survey questions asked for the specific share from both national governments and EU sources separately, and we assume that our respondents credibly distinguished between both original sources.Footnote 8

To grasp the effects of national and transnational interorganizational cooperation (H2a&b, H3a&b, respectively), we test umbrella membership and interorganizational cooperation separately both at the national and international levels. National umbrella membership is captured by a dummy variable (0 = no membership, 1 = membership). For the international level, we created a composite umbrella membership variable which entails whether an organization is part of a European or international umbrella organization.Footnote 9 Considering that transnational networking may occur outside umbrella organizations,Footnote 10 we also included variables capturing such cooperation. International networking is measured based on our survey question: ‘In recent years, have you increasingly networked with like-minded organizations abroad when trying to influence national legislation?’ on a 1–3 scale (no; yes, somewhat; yes, very much).

Assuming that active engagement with other national-level organizations may also stimulate professionalization, we constructed a composite organization-specific variableFootnote 11 consisting of three dimensions:Footnote 12 How often does your organization cooperate with other interest organizations in: (1) representation on advisory boards; (2) joint statements; and (3) joint political strategies? (never, occasionally, frequently).

We took two steps to generate variables reflecting groups’ standing in the domestic interest group systems. Assuming that organizational density may enhance professionalization (H4), we asked: In your opinion, is the number of interest organizations attempting to influence decision-making and legislation in your area increasing, decreasing or stable over the past 10–15 years? (strongly decreasing to strongly increasing, 1–5). As for the perception of political coordination with the state (H5), we asked: How would you rate the level of policy coordination/political exchange between the state and your interest group? (very weak to very strong, 1–5).

We also controlled for the perceived levels of financial stability of interest groups (scale 1–5), group type, that is whether groups represent concentrated or diffuse interests,Footnote 13 and transformed organizational age into a logarithmic scale.

Analysis

Are CEE interest groups professionalizing? Do they vary in terms of venues and strategies for professionalization?

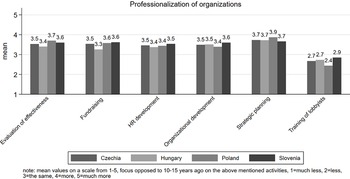

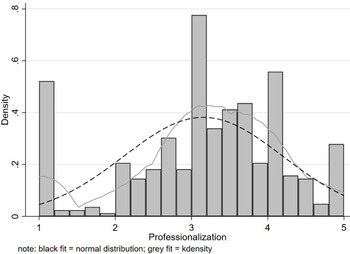

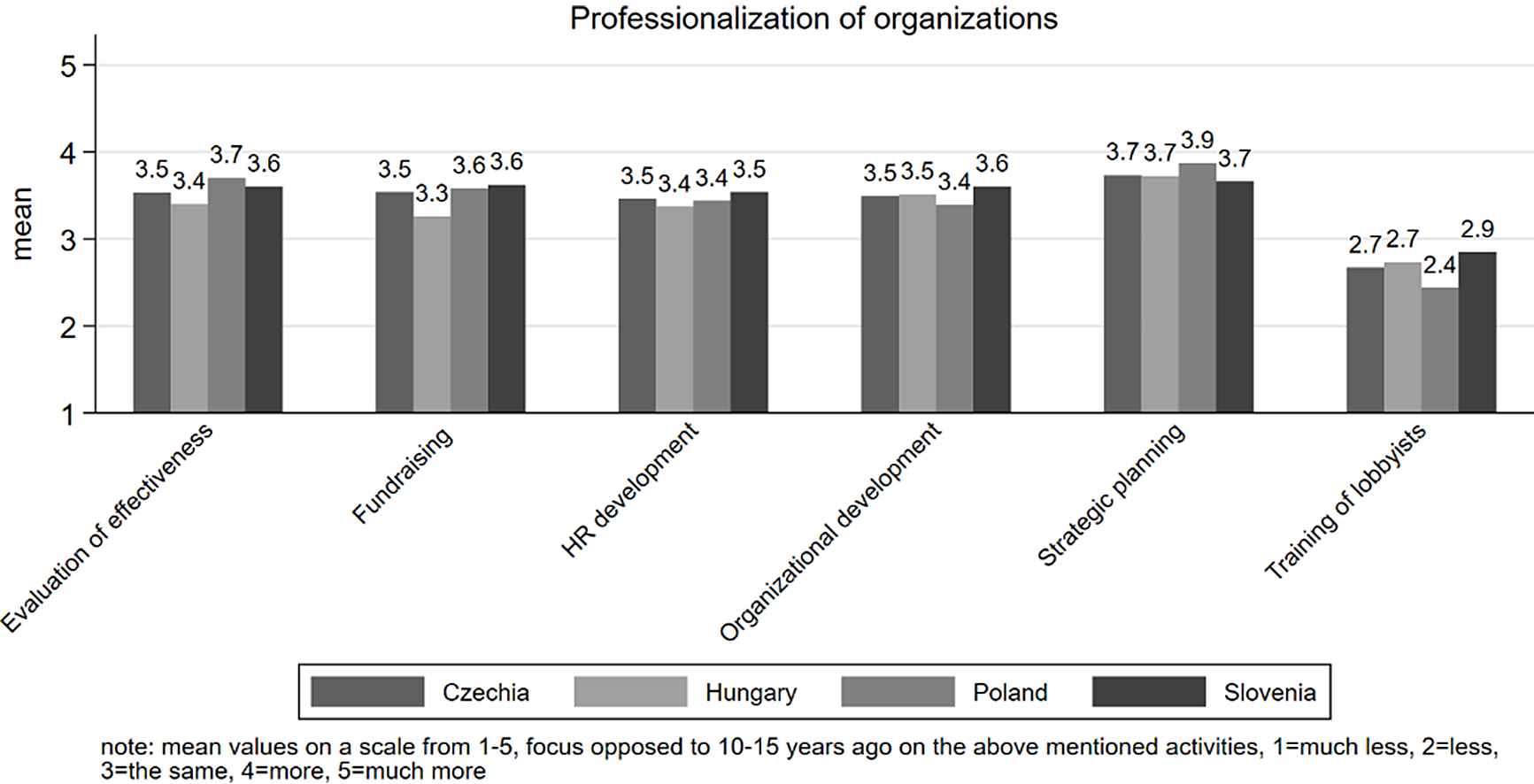

Our descriptive statistics show that there is a striking lack of variation between countries, but indeed an increasing trend across the board (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Increasing levels and forms of professionalization by country (aggregated for all policy fields).

Figure 2. Densities of the dependent variable (professionalization).

Figures reflecting various moderate country differences regarding interorganizational cooperation, networking with European organizations, umbrella memberships, and external funding sources (i.e., EU and national subsidies) can be found in online appendix (Appendix Figures A1–A5).

Our aggregated dependent variable for professionalization in the multivariate analysis is semicontinuous, hence enabling us to stick to a linear regression model with cross-sectional panel data (see also Klüver and Saurugger, Reference Klüver and Saurugger2013; Hanegraaff et al., Reference Hanegraaff, van der Ploeg and Berkhout2020). Country fixed-effects were applied to control for country-specific omitted variable bias.

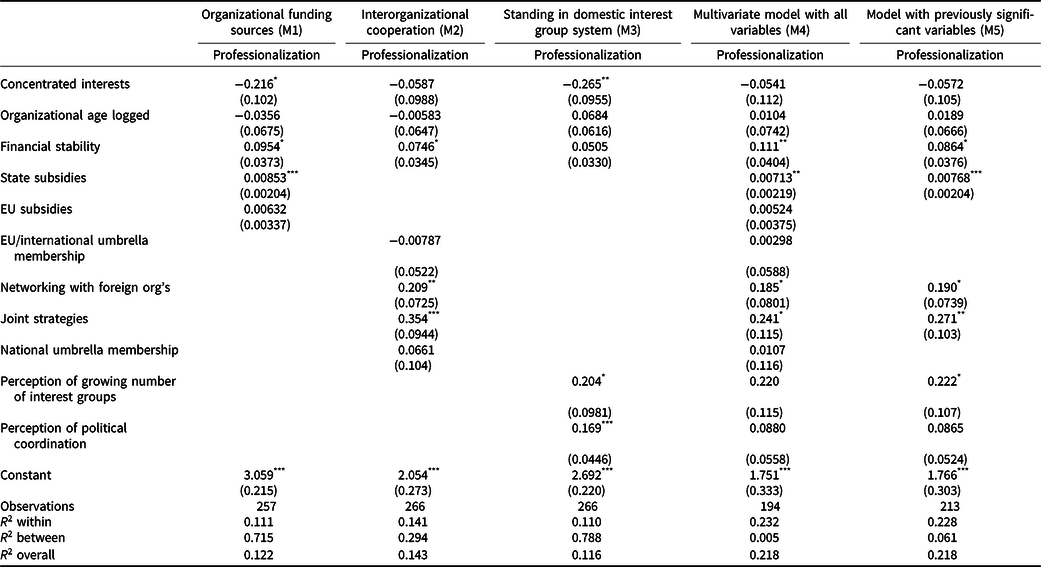

We first conducted separate regressions based on our three bundles of factors potentially driving professionalization – organizational funding sources, interorganizational cooperation, and (organizations’ standing in) national interest group systems – to single out the statistically most significant variables within these groups of factors. In a second step, we conducted two additional multivariate analyses (see Table 2), one including all proposed variables potentially affecting professionalization (Model 4), and one including only the variables that proved significant in models 1–3 (Model 5). We apply linear regressions as the fit was normally distributed. Values on the dependent variable are quite normally distributed with only one outlier, which is not problematic (Norman, Reference Norman2010) (see Figure 2). The models explain up to 23.2% (M4) of the variance within and up to 78.8% (M3) between our panel units with an overall value up to 21.8% (M4 and M5).Footnote 14

Table 2. OLS regressions, country fixed-effects models

Standard errors in parentheses.

* P < 0.05.

** P < 0.01.

*** P < 0.001.

Source: own elaboration.

In Model 1 (M1), we tested the effects of funding sources on professionalization, while also checking for the financial viability, age, and type of organizations (concentrated/diffuse). Unsurprisingly, our control variable financial stability has a relatively weak but significant positive effect on organizational professionalization. Put simply, the more financially stable an organization, the more it can invest in further professionalization measures. However, the findings become more interesting when we differentiate funding sources. Although EU funds may be a major lifeline for CEE interest groups, our data also show no relationship between EU funding and increased professionalization (see Czarnecki and Riedel, Reference Czarnecki, Riedel, Dobbins and Riedel2021 for a similar finding). This lends support to an argument put forward by Guasti (Reference Guasti2016) that many western/EU-based donors left CEE after approximately 2005–10 and shifted their activities further east (e.g., ex-USSR, Balkans) because the transformation process was seen as complete. State subsidies, however, have a rather weak, but significant and robust effect: a standard deviation increase in the share of state subsidies of the organizational budget enhances the professionalization composite index by 0.22 points (H1, see Table 1 for the summary statistics of the variables).

In Model 2, we tested to what extent interorganizational cooperation enhances professionalization. We did not find support for international (H2a) or national umbrella membership (H3a). This is surprising in view of other findings which show that umbrella membership can significantly enhance the political clout of interest groups (Fraussen et al., Reference Fraussen, Beyers and Donas2015). In contrast, networking with like-minded EU-level organizations and developing joint strategies with other domestic groups proved to be significant and of similar strength (M2). In the overall models (M4 and M5), this effect remains likewise strong. Similarly, the coefficient for joint strategies with domestic organizations has a positive effect on professionalization. Hence, we can confirm H3b: cooperation with like-minded organizations appears to promote organizational professionalization. Put differently, across our sample we find less formalized interorganizational cooperation activities such as networking with EU-level organizations and developing joint strategies with domestic groups to be more significant predictors of professionalization than formalized forums of cooperation such as umbrella organizations.

We now explore the set of factors grasped in Model 3, that is organizations’ standing in the domestic interest group system. As shown above, we asked individual organizations about their perception of whether the number of interest groups was decreasing, stable, or increasing in their area. As shown in Table 2 (Model 3), the perceived increase in the number of organizations proved significant for organizational professionalization and shows a robust effect throughout the tested models. This is an important finding because it shows that interest groups adjust their strategies to the ‘environmental pressures’, that is, to increased competition for resources, constituents, and influence at high organizational density levels. There is also a strong relationship between perception of being incorporated into the political coordination process and professionalization, that is every unit increase on the five-point scale reflecting political coordination is associated with 0.169 unit increase in professionalization. However, this latter effect loses its strength and significance in M4 and M5.

Finally, our control variable ‘concentrated/diffuse’ in Models 1 and 3 shows that being a concentrated interest correlates with not increasingly professionalizing. Instead, it appears to be more diffuse groups – here patients’ and healthcare awareness groups, ecological associations as well as employees’ and students’ organizations – which are investing in internal organizational development. However, the effect of ‘concentrated/diffuse’ proves to be heavily dependent on model specifications once we control for interorganizational cooperation and the domestic interest group system (M2, M3, M4, and M5). We also estimated all models with random effects instead of country-fixed effects, which yielded similar results. Hence, we believe our findings to be robust (see online appendix Table A1).

However, the demonstrated relationship between political coordination with the state and professionalization evokes the classic ‘chicken-and-egg problem’: does professionalization itself enhance political coordination with the state, or is the state actively promoting the professionalization of certain organizations? We believe the former is more plausible. As noted above, we also find state subsidies to be a predictor of professionalization, albeit relatively weak. Nevertheless, this lends some evidence to the side of the equation that it is often ultimately the state driving the professionalization of a certain set of organizations through funding incentives. This somewhat supports Olejnik’s (Reference Olejnik2020) argument on ‘patronage corporatism’ in the region, namely that postcommunist governments often find themselves in a symbiotic relationship with certain politically favorable organizations. Specifically, governments engage in political consultations and exchange with social partners with coinciding interests, many of which often directly receive government subsidies to accumulate political support. Our results reveal that such privileged organizations may capitalize on their proximity to the state by professionalizing their internal structures.

In Model 4, we test the robustness of our findings including all variables. What is interesting is that, among the funding-related variables, only the share of state subsidies and financial stability stay significant. The variables testing international networking, as well as the perception of political coordination all prove to be robust, although it is again difficult here to determine the direction of causality, that is whether being professionalized is a ‘ticket’ to transnational networking activities, or whether transnational networking is the driver of professionalization. The same applies to M5, in which we included only the variables that proved significant in Models 1–3. However, some effects are slightly weaker here. Yet the effect of national-level joint strategies with other organizations remains significant and relatively strong in M5 as does the perception of political coordination and networking.

Thus, our data essentially reflect three storylines. First, as shown with different degrees of significance in Models 3–5, we see that the domestic interest group system makes a difference. An increasing number of groups in the playing field is prompting organized interests to professionalize, hence suggesting a link between density and professionalization. Second, Models 4 and 5 add weight to the observation about patronage corporatism (Olejnik, Reference Olejnik2020): although the effect is relatively weak despite statistical significance, organizations benefiting from state subsidies and actively coordinating with the state appear to be funneling resulting material and nonmaterial resources into further professionalization, which in turn further consolidates their symbiotic relationship with the state. The state in turn may draw on such organizations to garner public support for its policy agenda, likely to the detriment of excluded organizations. On the upside though, the beneficial effects of joint action for achieving policy goals with domestic peers and networking on the EU/international level also are supported by our data. That is, interest groups lacking patronage/clientelistic embeddedness can potentially compensate their disadvantage with intensive domestic and international cooperation. In other words, networking and joint strategy-making can unleash mimetic isomorphic effects between organizations and ultimately boost the professionalization of previously structurally weaker organizations.

Conclusions

While this analysis allowed us to present a crucial first step in mapping the professionalization patterns of CEE interest groups, the lack of time-series data makes it difficult to gauge the validity of the causal mechanisms over time.Footnote 15 However, also in view of fluctuating political landscapes, our approach has enabled at least preliminary insights into the multitude of factors driving the internal professionalization of interest groups in CEE. First of all, our findings underscore those of Klüver and Saurugger (Reference Klüver and Saurugger2013) and Maloney et al. (Reference Maloney, Hafner-Fink and Fink-Hafner2018) that organizational resources are key to professionalization. However, unlike Maloney et al. (Reference Maloney, Hafner-Fink and Fink-Hafner2018), we found EU funding to be less important for professionalization than support from national governments. In line with Fraussen (Reference Fraussen2014) and Olejnik (Reference Olejnik2020), our data indeed show a ‘visible hand’ of the state in promoting organizational professionalization.

Moreover, our results lend much support to the soft power of isomorphic learning, both through domestic interorganizational joint strategy-making and transnational networking (outside formalized umbrella organization structures). Finally, our analysis is the first to our knowledge to tentatively link organizational professionalization with organizational density (conceptualized as the perception of growing numbers of groups).

This paper has the disadvantage of having aggregated data from four specific countries for the sake of a larger number of observations. Future research should therefore zoom in on the causal drivers of organizational professionalization within specific countries over time. Moreover, we encourage researchers to develop more exact measurements of population density and more systematically assess its effect on professionalization. Scholars should also further pursue the already developing research agenda on the relationships between professionalization, (hierarchical vs. bottom-up) internal organizational decision-making, and membership (Albareda, Reference Albareda2020; Heylen et al., Reference Heylen, Willem and Beyers2020; Berkhout et al., Reference Berkhout, Hanegraaff and Maloney2021). The question of internal organizational democracy (or the lack of) is particularly relevant in the CEE context where interest organizations were historically appendages of the party-state bureaucracy and lacked traditions of directly incorporating members into decision-making. Finally, and importantly, the presented data reveal little about the effects of selective state funding on singular groups. Specifically, are (national-conservative) CEE governments driving the professionalization of a diverse array of rivaling organizations (e.g., patients’ and medical associations, employer’s and employee’s associations, ‘clean’ and ‘dirty’ energy organizations) or only subsidizing certain segments of the organizational landscape, hence unilaterally driving professionalization? (e.g., only ‘dirty’ energy or employers)? Future analyses should therefore definitely explore how the ideological couleur of both governments and organizations affects the flow of state funds and which types of interest groups are benefitting.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773922000054.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge generous project funding from the German DFG (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) and Polish NCN (Narodowe Centrum Nauki).