Prohibition [of opium] was motivated by prestige reasons. At a time of modernization, which in most developing countries means imitation of Western models, the use of opium was considered a shameful hangover of a dark Oriental past. It did not fit with the image of an awakening, Westernizing Iran that the Shah was creating.Footnote 1

Introduction

What does the history of drugs consumption tells us of the life and place of Iranians in the modern world?Footnote 2

Narcotics, themselves a quintessential global commodity, figured prominently in the history of Iran. It all started with opium in ancient times. Panacea painkiller, lucrative crop, poetic intoxicant and sexual inhabitant, in the course of the twentieth century traditional opium users found themselves in a semantic landscape populated by the announcement of modernity. A ‘psychoactive revolution’ had happened worldwide, in which Iranians participate actively: people acquired the power to alter their state of mind, at their will and through consumption of psychoactive substances. Availability of psychoactive drugs had become entrenched in the socio-economic fabric of the modern world, complementing the traditional use of drugs, opium in particular, as a medical remedy.Footnote 3 With high drug productivity and faster trade links at the turn of the twentieth century, narcotics became widely available across the world. Iran, for that matter, produced large amounts of opium since the commercialisation of agriculture, which occurred in the late nineteenth century.

Old rituals turned into modern consumption, which was technological, through the use of hypodermic needles and refined chemicals; stronger, with more potent substances; and, crucially, speedier.Footnote 4 This ‘psychoactive revolution’ did not proceed unnoticed by political institutions. Although nameless characters in modern history, drug users have been an object of elites’ concerns in the political game of disciplining, modernisation and public order.Footnote 5 Spearheaded by the United States’ reformist momentum, a new regime of regulation of psychoactive substances, initiated in the early 1900s, reshaped the world into a more moral, read sober, one.Footnote 6 By the mid 1950s, consumption of intoxicants found narrow legitimate space and it was clamped down on by the police. Orientalised as a cultural practice of enslaving ‘addiction’ and pharmacological dependency, the use of drugs outside the West emerged in dialogue with global consumption trends and not simply as a tale of mimicry of Western consumption.Footnote 7

This chapter provides the background to the transformations that drug policy experienced before the 1979 Islamic Revolution. It describes processes of state formation, drugs politics and addiction during the pre-1979 period.Footnote 8 As in the case of other state policies during this era, ‘abrupt reversals, sudden initiatives and equally sudden retreats’ characterise drugs politics.Footnote 9 Iran adopted the whole range of policies with regard to narcotic drugs – from laissez-faire legalisation to total ban – since the inception of the first prohibitionist agenda in 1909 and, especially, over a period of four decades, between 1941 and 1979, when drug prohibition became a central element of the domestic and international discourse. Before streaming into this historical trajectory, the chapter discusses briefly the birth of the category of ‘addiction’ (eti‘yad) in its global-local nexus. This is situated in a period of great political transformation, corresponding to the Constitutional Revolution (1906–11) and the slow demise of the Qajar dynasty (1780–1925). The birth of ‘addiction’, one could argue, coincided with the naissance of modern political life in Iran.

Modernity and Addiction

American sociologist Harry Levine argues that the category of addiction is an invented concept dating back to the late eighteenth century. Its immediate relation is not to the idea of inebriation, as one might think, but to that of individual freedom, and therefore, to liberal governance.Footnote 10 The word ‘addiction’ itself has its etymological root in the Latin addicere, which refers to the practice of enslaving someone. In Persian, the Arabic-origin term e‘tiyad, suggests the chronic return, relapse or familiarity to something. Both terms express the impossibility of being ‘free’ and, therefore, the inability to make judgements or take decisions (especially in the case of addicere). This idea, generated in the medical knowledge of late nineteenth century Europe, gained prominence in Iran when foreign-educated students returned to their country and started using the lexicon, images and aetiology of Western medicine. Incidentally, Iranian intellectuals had relied almost exclusively on the accounts of foreign travellers in order to narrate the history of drugs, thus orientalising the life of the drug itself.Footnote 11

The emergence of a discourse on prohibition signed a moment of modernity in the political life of the early twentieth century, a modernity which was, nonetheless, at odds with the everyday life of Iranians. There, opium was the unchallenged remedy of the masses; it was administrated by local apothecaries (‘attari) as painkiller, sedative for diarrhoea, lung problems, universal tonic or, simply, a panacea for just about everyone who manifested symptoms, however vague, of physical or psychological malaise. The hakim – a traditional doctor – would dispense it ‘when challenged by an illness that he could not treat’.Footnote 12 British doctors travelling in Iran reveal that ‘to practice medicine among Persians means constant contact with the subject of addiction to opium. It crops up a dozen times a day … ’.Footnote 13 Rather than being only a medical remedy, opium also had its place in everyday rituals and practices. Opium smoking, using a pipe (vafur) and a charcoal brazier (manqal), usually occurred in front of an audience – either other opium smokers or just attendees – the interaction with whom encouraged the reciting of poetry – Sa‘adi, Ferdowsi and Khayyam being main poetic totems – and inconclusive discussions about history and the past in general. Opium had the reputation of making people acquire powerful oratorical skills. This circle, doreh, enabled ties of friendship and communality to evolve around the practice of smoking, especially among middle and upper classes, with opium being ‘the medium through which members of a group organized’.Footnote 14 In the course of the twentieth century, people habituated to this practice were referred to, somewhat sarcastically, as the pay-e manqali, ‘those who sit at the feet of the brazier’. Conviviality, business, relaxation and therapy converged in the practice of opium smoking.

Opium was a normative element of life in Iran. At the end of the day of fasting or before the sunrise hour in the month of Ramadan, ambulant vendors would provide water and, for those in need, opium pills by shouting in the courtyards and in front of the mosques, ‘there is water and opium! [ab ast va taryak]’.Footnote 15 In northern Iran, mothers would give small bits of opium to their children before heading to the fields to work. Later, before bedtime, children would be given a sharbat-e baccheh (the child’s syrup), made of the poppy skin boiled with sugar, which would ensure a sound sleep.Footnote 16 These stories have global parallels; in for instance popular narratives in southern Italy, under the name of papagna (papaverum), and in the UK under the company label of Godfrey’s Cordial. At the time of modernisation, such practices contributed to the demonization of the popular classes (workers and peasants) in the public image, describing their methods as irresponsible and not in tune with modern nursing practices.Footnote 17 Individual use, instead, would be later described by modernist intellectual Sadegh Hedayat through his novels’ narrators, whose characters dwelled, amid existential sorrows and melancholies, on opium and spirit taking.Footnote 18 By 1933, Sir Arnold Wilson, the British civil commissioner in Baghdad, would be adamant arguing that ‘[t]he existence in Western countries of a few weak-minded drug addicts is a poor excuse for under-mining by harassing legislation the sturdy individualism that is one of the most enduring assets of the Persian race’.Footnote 19 The frame of addiction as inescapably connected to opium use, however, had already been adopted by Iranian intellectuals and political entrepreneurs in the early days of the Constitutional Revolution. The demise of the old political order, embodied by the ailing Qajar dynasty, unleashed a reformist push that affected the social fabric – at least in the urban areas – and models of governance, with their far-reaching influence over individuals’ public life.

Reformists and radicals in the early twentieth century, either inspired by the Constitutionalist paradigm or because they effectively took part in the upheaval, called for a remaking of Iranian society and of national politics, starting from the establishment of a representative body, the Parliament (Majles) and the adoption of centralised, administrative mechanism in health, education, language, social control and the like. Constitutionalists represented a wide spectrum of ideas and persuasions, but their common goal was reforming the old socio-political order of Qajar Iran. Modernisation, whatever its content implied, was the sole and only medium to avoid complete subjugation to the imperial West.

By then, opium had come to play an important role in the economy of Iran, known at the time as Persia. In the Qajar economy, the poppy was a cash crop that provided steadfast revenues in a declining agricultural system. With commercialisation of agricultural output, opium became omnipresent and with it the habit of opium eating, supplanted since the early 1900s with opium smoking. Constitutionalists referred to opium addiction as one of the most serious social, political ills afflicting the country. They were actively advocating for a drastic cure of this pathology, which metaphorically embodied the sickness of late Qajar Iran.Footnote 20 Hossein Kuhi Kermani, a poet and reformist intellectual active over these years, reports that when Constitutionalists conquered Tehran, they started a serious fight against opium and the taryaki (aka, teryaki, the opium user), with missions of police officers and volunteers in the southern parts of Tehran with the objective to close down drug nests.Footnote 21 These areas would be theatres of similar manifestations a hundred years later, under the municipal pressure of Tehran’s administrations.Footnote 22

The Constitutionalists’ engagement with the problems associated with opium coincided on the international level with the first conferences on opium control. The first of these meetings happened in Shanghai in 1909, the milestone of the prohibitionist regime in the twentieth century. In Shanghai, Western powers attempted to draw an overview of the world’s drug situation in a bid to regulate the flow of opium and instil a legibility principle in terms of production and trade, with the ultimate objective to limit the flow of commercial opium only to medical needs. Iran participated in the meeting as part of its bid to join the global diplomatic arena of modernity. Ironically, the Iranian envoy at this meeting, Mirza Ja‘far Rezaiof, was himself an opium trader, disquieted by an appointment which could have potentially ‘cut his own throat’, given that opium represented Iran’s major export and his principle business.Footnote 23

Amidst the momentum of the Constitutionalists’ anti-opium campaigns, Iran became the first opium-producing country to limit cultivation, and to restrain opium use in public.Footnote 24 On March 15, 1911, a year before The Hague Convention on Opium Control, the Majles approved the Law of Opium Limitation (Qanun-e Tahdid-e Tariyak), enforcing a seven-year period for opium users to give up their habit.Footnote 25 This provision also made the government effectively accountable for the delivery of opium to the people, with the creation of a quota system (sahmiyah), which required the registration of drug users through the state administrative offices and the payment of taxes against the provision of opium. In other words, the law sanctioned public/state intervention in the private sphere of individual behaviour – i.e. consumption – and granted the inquisitor’s power to the officials of the Ministry of Finance. Even though this decision did not mean prohibition of the poppy economy, it signified that the new politics triggered by the Constitutionalist Revolution followed lines tuned with global trends towards the public space and therefore with modern life (style).

Whether opium prohibition was inspired and reproduced under the influence of Western countries or it had indigenously emerged, is a debate that extends beyond the scope of this chapter.Footnote 26 What can be discerned here however, are the effects of state-deployed control policies on the social fabric. The formation of modern Iranian state machinery made possible a steady intrusion, though fragmentary, into the life of opium users and of opium itself. In the pre-twentieth-century period, in fact, Iranian rulers had at different times ruled in favour of or against the use of opium and other drugs (including wine), but at no time had they had the means to control people’s behaviour and so affect the lives of multitudinous drug users. The Shahs themselves have been known, in popular narratives, as divided into those fighting against, or those indulging in, the use of opium. At times, the rulers would indulge in drug use so heavily as to destabilise their reign.Footnote 27 By the time of the Constitutional Revolution, the idea of a ruler whose mind and body is intoxicated by opium or other substances had become a central political theme, fuelling, among other things, an Orientalist portrayal of power in the Eastern world. The reformers of this period used the failure of past sovereigns to warn against the danger of intoxication, marking clearly that modernity did not have space for old pastimes. Genealogically, reformers interpreted opium and addiction to it as the cause of national backwardness, a leitmotif among revolutionaries during the Islamic Revolution of 1979 (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 Donkey Smoking Opium in a Suit

The small statue dates back to the late 1950s, early 1960s.

State Building on Drugs

When the old Qajar monarchy fell apart and the military autocrat Reza Khan rose to power, the priorities of the Constitutional Revolution narrowed down to the imperative of state building, centralisation, control over the national territory and systematic taxation. For this and other reasons, the poppy maintained its firm place as a key asset in the national economy. Opium represented a major source of state building for the newly established Pahlavi state from 1925 onwards. It contributed directly to the creation and upgrading of the national army, a fact that, by 1928, pushed Reza Shah to create the Opium State Monopoly.Footnote 28 By that time, Iran was producing 30 per cent of the world’s opium, exporting enormous, unregistered quantities towards East Asia.Footnote 29 Although the government intended to restrain opium consumption, they were neither capable, nor willing to give up an important share of their revenues, some years as high as 9 per cent of the total gross domestic product.Footnote 30 As a strategic asset, opium never came under full state control; resilient farmers, including nomadic tribes threatened by the encroachment of the state and its anti-tribal/sedentarisation policy, continued to harvest and bargain with the authorities, at times successfully, at others contentiously. Emblematic of the contentious nature of opium politics, even before Pahlavi modernisation, was the bast (sanctuary) taken by the people of Isfahan in the city’s Telegraph Compound in 1923, which, in a matter of days, if not hours, turned into a full seven-thousand-person demonstration against attempts by the central government to gain full control, with hefty taxation, over the production of opium.Footnote 31 Members of the clergy participated, not least because considerable portion of vaqf lands (religious endowments) in Iran’s southwest were cultivated with the poppy. Opium, as such, constituted a vital source of capital, which made poppy growers (or better, their capitalist patrons) the wealthiest class.Footnote 32 Inevitably, this led to an economy of contraband of vast proportions, which had few equals globally and which supplied the market at its bottom and top ends, respectively petty merchants in the many ports connecting Bushire to Vladivostok, and legitimate pharmaceutical houses which used Persian opium ‘because of its superior quality and high morphine content’.Footnote 33 Capital accumulation over the first half of the twentieth century among a circumscribed class of landowners might have well occurred because of opium production.Footnote 34

Beside the international trafficking networks, the opium economy produced a social life of its own, one in which, well into the Pahlavi era, the presence of the state remained a latency. With the creation of the Opium Monopoly, the state required all the opium produced locally to be stocked into governmental warehouses, which were administrated by state officials. Yet, much of the opium sap never reached these locations or, when it actually did, it did so only at face value, with quantities much inferior to the actual production. Concealed during the harvest period, opium was then sold at a higher price to smugglers who would resell abroad at higher rates.Footnote 35

The list of those involved in the opium economy was not restricted to landowners, cultivators and smugglers. Labourers, commission and export merchants, brokers, bazaar agents, chiefs, clerks, manipulators, packers, porters, carpenters, coppersmiths, retailers, and mendicants were part of this line of production. During harvest time, they were often accompanied by a motley crowd of dervishes, story-tellers, musicians, owners of performing animals and a whole industry of amusement providers who were paid for their company or ‘given alms by having the flat side of the opium knife scrapped on their palms’.Footnote 36 An observer of such events reports from 3,000 to 5,000 strangers in a single area during the harvest season. The village mullahs, who might have blessed the event with a salavat (eulogy to the prophet and his family) were given sap of premium opium as tokens of gratitude . In the first decades of the century, among the 80,000 inhabitants of Isfahan, about one quarter gained their living directly or indirectly in the opium economy.Footnote 37 The front store of shops advertised the narcotic with signs as such ‘Here the best Shirazi and Isfahani Opium is sold!’Footnote 38 Stephanie Cronin indicates that, in certain regions of the country, opium had even become a local currency in times of political instability.Footnote 39 When the modernising state increased its effort at controlling the opium economy, the effect was that the large number of middlemen and beneficiaries of this economy remained unemployed or saw their revenues decline significantly. It is plausible to think that many of these categories joined forces with the widespread associations of smugglers which had enriched the informal economy ever since. The risk of ‘moral reputation’ and ‘moral isolation’ compelled Iranian policymakers to cooperate with the international drug control regime.Footnote 40 For the first time in Iranian history, the crime of smuggling (qachaq) was also included in a new legislation. It is reported that between the late 1920s and the early 1930s, more than 10,000 traffickers were arrested per year, prompting the government to acknowledge that there were more people smoking contraband opium than government opium.Footnote 41 Yet, while signing the Geneva Convention on Opium Control (1925), a diplomatic agreement that provided statistical information on the production and trade of opium, the Iranian delegation maintained its reservations on the key issue of certification and restriction of exports to those countries in which opium trading was illegal.Footnote 42 Smuggling flourished as never before, a historical fact that deserves a more accurate account than that provided here.

Reza Shah himself was a regular user of opium, although it is said, perhaps hagiographically, that he smoked twice a day standing on his feet – as opposed to those laying on their side indulging in poetry, conversation and day-dreaming.Footnote 43 In this image, one can interpret the difference between the traditional Shahs of the pre-Pahlavi period – several of them known opium users – and the moderniser Shah who used opium without losing his mental alertness and bodily stamina. Together with the Islamic veil, the traditional hat, nomadic life and sufi practice (tasavvof), opium smoking was in fact seen as a habit that would have little space in the making of modern Iran.Footnote 44 Its place, even within the practice of apothecaries, had to be substituted by modern science and Western medicine. Restrictions started to be applied to opium, as other allegedly customary elements such as ethnic attire, the veil and traditional hats were banned from being used in public. Reza Shah banned the use of opium for those in the army and in the bureaucracy.Footnote 45 Nevertheless, the Majles itself reportedly had a lounge in which deputies could ease their nerves and discuss issues of concern over an opium pipe.Footnote 46 It was the façade of the life of opium, particularly when confronted by Western observers, which preoccupied the Shah. To demonstrate that the real concern of the government was alignment with Western models of governance and behaviour, in 1928 the government approved the Opium Restriction Act, which made opium cultivation legitimate only after government certification through the State Opium Organisation. The Organisation supervised all opium exports as agreed by the 1925 Geneva Agreement; together with the Ministry of Finance, it collected the opium residue (sukhteh) from public places and managed the sale of cooked opium residue (shireh-ye matbukh) to the smoking houses (shirehkesh khaneh).Footnote 47 The idea that the government was keen to purchase the residue of smoked opium contributed, indirectly, to the shift from traditional opium eating – as it had been diffused in Iran from times immemorial – to smoking, which was a practice emerging at the turn of twentieth century, under the influence of Chinese opium culture. This shift in governmental policy had a lasting effect on drug consumption over the following decades.

Under the order of the Allied forces and with the Anglo-Soviet Occupation of Iran, Reza was sent into exile in 1941. Earlier that year, the government had, in a populist push, banned opium production in twenty-two regions – but not Isfahan – in a move that would have had drastic consequences were Iran not occupied by the Allied Forces.Footnote 48 De facto, the ban was a complete failure. Cultivators in these regions protested by selling their opium at very cheap prices, in order to empty their stock so that the government had to allow cultivation again in order to refill the national opium reservoir, a strategic asset in periods of conflict.Footnote 49 The resilience and tactics of the farmers exemplified well the influence that these non-elites could have on policymakers. However, the consequences of their defiance were catastrophic; cheap prices combined with the perception of opium as an essential source of relief from pain and protection against illnesses, incited large numbers of Iranians to consume it and, in some cases, to set up small opiate factory-shops to cook and sell the opium residue.Footnote 50

It is with the setting up of these small opium-cooking factories that an opium derivate gained popularity among the working class: shireh. Considered more detrimental and addictive than opium, with a higher morphine content, shireh was sought by longer-term smokers. Mostly smoked by working-class men in specific factory-shops, it had a greater stigma, often making it comparable to that of the brothels in the moralising public narratives.Footnote 51 Interestingly enough, these places were called dar-ol-‘alaj, the Arabic expression for ‘clinic’ or ‘treatment house’, which hints at the inseparability of recreational and self-medicine in opiate use over this period.Footnote 52 In Tehran alone, there were more than a hundred shirehkesh-khaneh spread across the city from south to north. In one instance, a bus operated as a peripatetic smoking house on the Karaj road to avoid police raids aimed at closing them. The driver’s aid shouted the slogan, ‘we take away dead, we bring back alive [morde mibarim, zendeh miyarim]’.Footnote 53 But the widespread use of opium and shireh reached a climax during the allied occupation (1941–46), due to the unsettling conditions in which most people lived, especially in the central and northern regions.

War, Coups d’État and International Drug Control (1941–55)

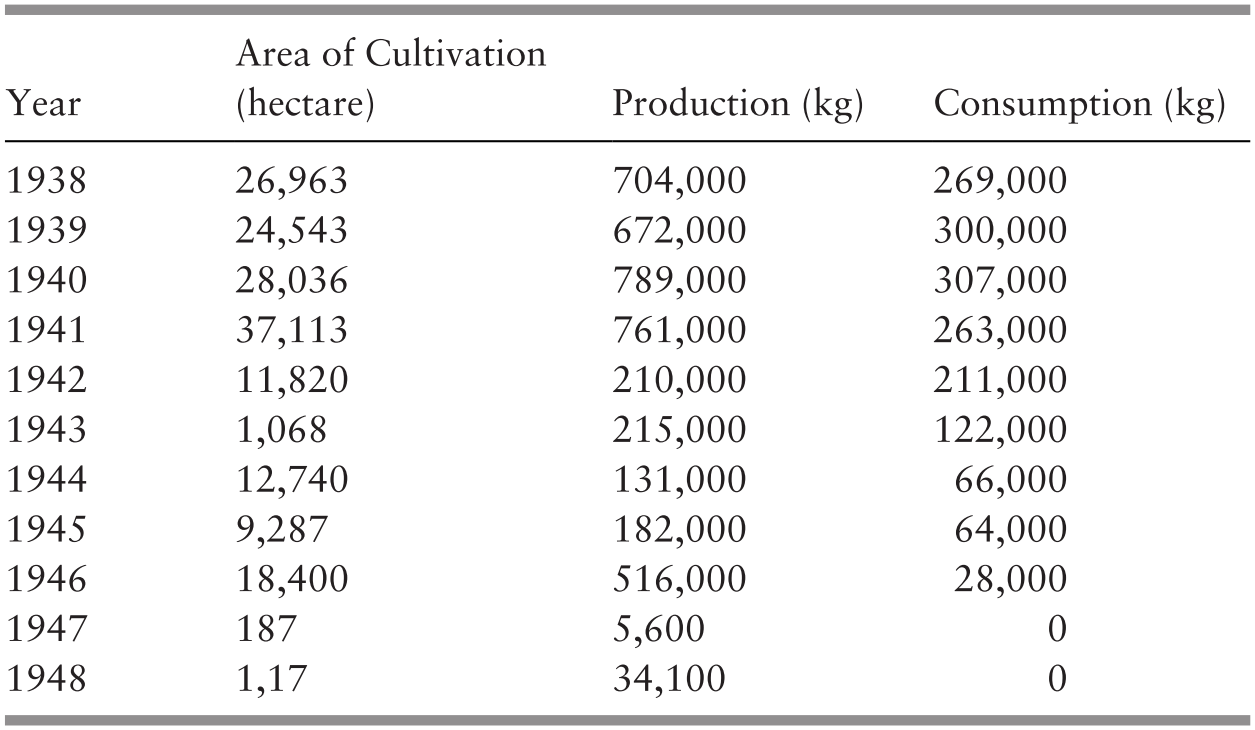

In 1944, the government of the United States circulated a joint resolution signed by Congress among all opium-producing countries, which urged these countries to effectively eradicate or reduce poppy cultivation and to limit their opium production to legitimate medical needs.Footnote 54 One of the primary reasons was the seizure of opium in the United States, three-quarters of which had allegedly originated in Iran and crossed the Pacific thanks to Chinese merchants heading to San Francisco.Footnote 55 Thus, a global network of opium smuggling had been born before the coming of organised criminal groups, although the Iranian authorities maintained that they had progressively eradicated poppy cultivation (Table 2.1). The reality on the ground, in fact, spoke of a stupendous flow of opium out of Iran, much to the concern of Western powers – a concern that was mostly an expression of concern (the threat of opiate addiction against the nation), without real concern (the embeddedness of opiates in popular practice).

Table 2.1 Poppy Cultivation, Production and Consumption (1938–48)Footnote 56

| Year | Area of Cultivation (hectare) | Production (kg) | Consumption (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1938 | 26,963 | 704,000 | 269,000 |

| 1939 | 24,543 | 672,000 | 300,000 |

| 1940 | 28,036 | 789,000 | 307,000 |

| 1941 | 37,113 | 761,000 | 263,000 |

| 1942 | 11,820 | 210,000 | 211,000 |

| 1943 | 1,068 | 215,000 | 122,000 |

| 1944 | 12,740 | 131,000 | 66,000 |

| 1945 | 9,287 | 182,000 | 64,000 |

| 1946 | 18,400 | 516,000 | 28,000 |

| 1947 | 187 | 5,600 | 0 |

| 1948 | 1,17 | 34,100 | 0 |

By the end of World War II, a small number of US narcotics officials, many of whom had been previously working as intelligence officers, helped the Pahlavi state to re-produce a prohibitionist regime in Tehran, which, in their strategy had to embody a global model for the rest of the region and beyond.Footnote 57 Through this collaboration, US influence within Iran increased significantly, especially for what concerned the repressive, coercive institutions of the Pahlavi state: police, intelligence and the army. For their part, the Iranian authorities had repeatedly played the opium card to convince the United States to provide development assistance funds, by highlighting the threats of opiates and Soviet communism. In this setting, Iranian authorities remained purposefully ambivalent, refusing to provide clear information to the FBN officials, convinced also of the geopolitical relevance that Iran had acquired in respect to the Soviet anathema. Knowledge about the drug situation came mostly from non-governmental sources, which at times concocted a distorting image of opium consumption and culture in Iran.Footnote 58

The emergence of the Society for the Fight against Alcohol and Opium, created in 1943, proved tactical to this situation. It campaigned aggressively for the prohibition of all alcoholic spirits and opiates and announced astonishing data on ‘addiction’. In its first three years, it distributed around 80,000 information leaflets, participated in more than a hundred public meetings and intervened regularly on national radio.Footnote 59 Members of this organisation belonged exclusively to the elites, among whom were members of parliament, judges, prominent public figures and their wives. Their influence operated in a discursive way towards the public, but it also affected the perception of the drug problematique among the authorities, including American officials. They circulated statistics, for instance, with the purpose of engendering a sense of crisis:

two million grams of opium used daily … six million rial lost every day … 5,000 suicide attempts with opium [women’s figuring prominently] … one thousand-three hundred shirehkesh-khaneh operating in the country, one hundred thousand people dying every year for opium use and fifty thousand children becoming orphans.Footnote 60

Furthermore, the Society arranged theatre pieces about opium which often depicted a caricatured opium smoker as the sources of all social and family evils, from which the expression khanemansuzi (burning one’s household) gained popularity. On November 22, 1946, the Society organised a public ceremony of the vafursuzan (opium pipe burning, literally ‘those burning the vafurs’) – antecedent to the Islamic Republic’s opium-burning ceremonies – to which foreign dignitaries would participate, praising their moral prohibitionist effort.Footnote 61 In its manifesto, this society declared, ‘it seems that the question of the effects of opium and alcohol has reached a point where the extinction of the Iranian race and generation will take place … In the name of the protection of the nationality, this committee has been created’.Footnote 62 This mixture of Persian nationalism and sense of crisis tainted the official discourse on drugs and pushed lawmakers to adopt tough measures on drug consumption.

The Society’s stance on drugs ignored the extent to which opium was part of the cultural norms and everyday customs of Iranians. Instead, it was instrumental in introducing legislations that targeted public intoxication among the popular classes. The new anti-drug propaganda described opium as a primary impediment to labour, although Iranian workers had traditionally used opium for its tonic effect.Footnote 63 Coincidently, the government issued, first, a ban on the fifteen-minute work break for opium smokers, and then circulated a communiqué pointing out that ‘workers should not use opium on their jobs’.Footnote 64 Employment of officials had to be based on their avoidance of opium use, a behaviour that could have cost them their place at work.Footnote 65 Modernisation of the national economy, which had to move conjunctly with social behaviour, passed through the progressive abandoning of opium in favour of other habits, such as alcoholic drinks. The teriyaki was inherently weak and its place in the post-1941 public discourse condemned as underserving. Associated with lying, the addict was unreliable in the workplace, a perception that was widespread in the rural as much as the urban centres.Footnote 66

The new bureaucratic apparatuses of the state, bolstered by the ideological and logistical support of the US anti-narcotic officials endowed the Anti-Opium Society with unprecedented clout over this issue. On January 28, 1945, hence, a deputy from Hamadan, Hassan Ali Farmand, who had previously opposed the Opium Monopoly in 1928, introduced a bill for the total prohibition of cultivation of poppies and use of opium.Footnote 67 Between 1941 and 1953, the Majles approved a number of legislative acts: the creation of a ‘coupon system’ for registered drug users; the prohibition of opium cultivation in 1942–43; a ban on opium consumption in August 1946 under Prime Minister Ahmad Qavam, which lasted only ten months; and, under the government of Mohammad Mosaddeq (1951–53), a law amendment banning production, purchase and sale of opium and its derivatives and the consumption of alcoholic drinks.Footnote 68 Over this period the government declared a war on coffeehouses, which were either to be closed or to cover up the use of opium within the building; enforcement of laws against public intoxication (tajahor) incremented, enshrining a legal framing which would prove durable up to the new millennium.

Prohibitionist rhetoric gained further momentum during the oil nationalization under Mosaddeq when the parliament voted unanimously to ban alcohol and opium use within six months.Footnote 69 The move, however, was largely a populist tactic to gather support (including that of the clergy: alcohol ban) at a time when economic sanctions and international isolation were crippling the life of Iranians. Even government officials had very little belief in the effectiveness of this law. Asked by a journalist whether one could get a drink in Tehran six months from the entry in force of the law, a government official laughed and responded, ‘Yes, and six years from now, too’.Footnote 70 At the same time, with state finances shrinking because of the stalemate in the oil industry, Mossadegh, in agreement with the Majles, had pushed for a steady increase in opium production in order to compensate for the drop in oil exports. The strategy had its limited results and ‘the government reported opium revenues of over 200 million rials a year from 1951 to 1954, about 20 percent of the total’.Footnote 71 In 1952, the United Nations accused Iran together with Communist China of smuggling opium, following a period of poor cooperation between the country and the US-led international drug control regime.Footnote 72 The British government also attempted to delegitimise the nationalist government in Tehran, ahead of the planned coup, by, among other methods, ‘spreading the rumor that Mosaddeq reeked of opium and “indulged freely” in that drug’.Footnote 73 But, paradoxically, while the United States and the United Kingdom planned to topple Iran’s democratically elected prime minister, the United States purchased, both legally and illegally, large amounts of Iranian opium, out of the fear that the ‘Soviet bomb’ and the outbreak of a nuclear confrontation amid the Korean War (1950–53) would bring unprecedented levels of casualties.Footnote 74 Opiates endured as the global painkiller, while the Cold War mentality required the primacy of strategic calculi over other diplomatic objectives, including that of international drug control.Footnote 75

Opium Prohibition and Westoxification: (1955–69)

With the CIA-orchestrated coup d’état that brought Mohammad Reza Pahlavi back to the peacock throne, the United States gained greater influence over Iran’s domestic politics. For the FBN and its chief Anslinger, this meant that Iran had to become a global model of the prohibitionist regime. The decision to cooperate with Washington’s in fieri War on Drugs, writes Ryan Gingeras, provided an essential model for future agreements, ‘should America’s global campaign against narcotics proceed successfully’.Footnote 76

Jahan Saleh, Minister of Health under Mohammad Reza Shah, promotor of the ban, conceded that, ‘Prohibition [of opium] was motivated by prestige reasons. At a time of modernization, which in most developing countries means imitation of Western models, the use of opium was considered a shameful hangover of a dark Oriental past. It did not fit with the image of an awakening, Westernizing Iran that the Shah was creating’.Footnote 77 Prohibition worked instrumentally in the securitisation of domestic politics, while it steadily aligned the monarchy with the US-led camp. Thus, in November 1955, Jahan Saleh pushed for the approval of the Law Prohibiting Poppy cultivation and Opium Use. He argued that there were around 1.5 million drug addicts out of a population of 19 million.Footnote 78 Given the embeddedness of the opium economy and culture, the legislative process encountered obstacles from a variety of social groups, such as coffeeshop owners, opium traders, apothecaries, landowners in poppy-cultivated regions and those who thought that the poppy was an inalienable part of Persian culture and backbone of its people’s economy.Footnote 79 Yet, the public perception of drug (ab)use as a social liability and danger to people’s health outplayed the economic benefits of the poppy. Reports were widespread that the number of opiate (ab)users – the term used was inevitably ‘addict’ – had reached two million; in areas such as Gorgan, the Caspian region, it was said that 90 per cent to 100 per cent of the population was addicted (addiction in these cases probably signifying opium consumers).Footnote 80 Evidently, some exaggeration was at play and instrumental in causing a public crisis about opium, a feature that would prove long lasting.Footnote 81

In his speech in front of the Senate, the proposer of the prohibition bill, Jahan Saleh, first downplayed the financial value of opium for the economy, then made clear that the health of people had no monetary price and that ‘people’s productivity would consequently increase by hundredfold’.Footnote 82 This did not convince his opponents, who requested the bill to be discussed in all the relevant committees, which were numerous. The request however was rejected by senator Mehdi Malekzadeh, who with emphatic sentiment and a trembling voice, reacted, ‘I am a staunch supporter of this bill, I know every bit of it, there is not a single section of this bill that does not have a financial or judicial aspect, but this is a health bill and when confronted with health questions other questions have no value. This is a bill on the lives and wellbeing of people’.Footnote 83 By prioritising the public health dimension of the opium crisis, the proponents intended to bypass challenging political questions. After all, health crises are moments of reconfiguration of the political and social order.

Following the debate, the bill passed to the Majles, which approved it and added to its text an article on the prohibition of alcohol sale and procurement, much to the astonishment of the royal court and the modernist elites. Negotiations ensued to remove reference to alcohol; the Shah himself, during a meeting with the members of parliament, stated that ‘one of the significant undertakings that have been made is the outset of the fight against opium, which must be fulfilled with attention’, leaving out any reference to the issue of alcohol and spirits.Footnote 84 By October 30, 1955, the text was amended in reference to alcohol and approved as the ‘Law on Prohibition of Poppy Cultivation and Opium Use’.Footnote 85 The law envisaged heavy penalties for producers, traffickers and consumers. If found with fifty grams of opium or one gram of any other narcotic, the offender could face up to ten years of solitary confinement, and later the death sentence. For the ‘addict’, a six-month period of grace was conceded to kick her/his habit. Opium use in public places, such as cafes and hotels, could incur hefty fines and between six months to one year imprisonment, with recidivists seeing the weight of the sentence increased.Footnote 86 It was a moral onslaught accompanied with the machinery of policing, which caused a drastic rise in the adulteration of opium, causing, according to an observer, ‘deleterious effects’ on consumers.Footnote 87

The target of this new policy was not the international drug networks that operated throughout Iran. Instead, subaltern groups, such as paupers, sex workers, vagrant mendicants and members of tribes that operated smuggling routes, paid the highest price, in the guise of prison and stigmatisation. It is no coincidence that the institutionalisation of a national system of incarceration took place during these years.Footnote 88 The prison regime did not specifically punish drug consumption by that time; rather it focused on inebriation and the breach of public morality, with an emphasis on other drugs such as hashish, understood as heterodox by the religious establishment and ‘left leaning’ by the police, similarly to how FBN director Harry J. Anslinger regarded cannabis as the drug of the perverted jazz milieu.Footnote 89 Two years after the entry into force of the law, the government had to declare an amnesty for drug offenders, because of the overcrowding of the facilities. Shahab Ferdowsi, then advisor to the Ministry of Justice, revealed that ‘poor people are paying the price of this policy’.Footnote 90 Imposed as a modernising programme, prohibition targeted those categories that were at odds with the Pahlavi view of what Iranian society should look like. That meant targeting – unsystematically – a good many outside the modernist city-dwellers.

The state discourse promoted, by indirect means, ‘useful delinquency’ as opposed to political opposition, the effects of which can be seen in Tehran thugs’ participation during the coup against Mossadegh.Footnote 91 The words of Michel Foucault come timely for this claim: ‘Delinquency solidified by a penal system centred upon the prison, thus represents a diversion of illegality for the illicit circuits of profit and power of the dominant class’.Footnote 92 It is clear that the creation of a moral public, whether in political terms (anti-Communism, Westernised), or in social terms (productive, healthy and law-abiding), was among the central concerns of the Pahlavi state, while at the same time it was also a tactical expedient. Besides, there was also ‘appetite for medicine’.Footnote 93 The Bulletin of Narcotics reports, ‘Iran, in a special programme inaugurated in November 1955, established treatment centres in its several provinces to provide withdrawal and short-term rehabilitation for addicts’.Footnote 94 But it later adds, ‘those addicts who are convicted of crime usually receive no special treatment, and are sent to prison as are other law violators’.Footnote 95 In the words of the Iranian Minister of Health Amir Hossein Raji, the objective was:

to cure those who can be cured and to remove by imprisonment those who cannot be cured; to stop the supply of drugs from external and from internal sources, to fill the place of the poppy crop in the agricultural economy of the country; to create a social climate in which the use of drugs is reprehended.Footnote 96

The discretion of treatment, the diagnosis of curability and the necessity of punishment coalesced in the governance of illicit drugs. The stated formed new powers in the terrain of social control, citizens’ well-being and public health. In 1959, the law was further tightened, outlawing the possession of poppy seeds with punishments of up to three years, despite these seeds being widely used in foodstuff, including bread.Footnote 97 Beside the heavy sentences, the prohibitionist regime of 1955 reproduced itself by funnelling the monies generating by drug confiscations (including property) to the anti-narcotic machinery.Footnote 98 By the early 1960s, the government was allocating a five million dollar budget for anti-narcotics, while the United States provided around 250,000 USD for Iran’s contribution to international drug control, including military hardware, planes, helicopters and training.Footnote 99 It is evident how anti-narcotics went hand in hand with the expansion of the intelligence service: in 1957, coincidentally, Garland Williams, one of the influential FBN supervisors, arrived in Tehran to set up a narcotic squad, while the CIA and the Mossad were establishing the SAVAK, Iran’s infamous secret service.Footnote 100

Concomitant to the militarisation of the drug assemblage (here an anti-narcotic assemblage), in 1961, a cabinet decree re-instated the capital penalty for those engaging in drug trafficking following the signing of the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (1961). The international agreement ‘exhorted signatory states to introduce more punitive domestic criminal laws that punished individuals for engagement in all aspects of the illicit drug trade, including cultivation, manufacture, possession, transportation, sale, import, export or use of controlled drugs for non-medical purposes’.Footnote 101 The international drug control machinery advised governments to incarcerate users; it also threatened to apply an embargo against those countries which held non-transparent attitudes on illicit drugs.

Over this period, the number of sentences in Iran increased substantially, concomitantly with the announcement of the state-led ‘White Revolution’ in 1963. Announced by the Shah as the new deal for Iranian agriculture, the reform sought to overhaul the century-old pattern of land possession and cultivation. Beside manoeuvring limited land redistribution to middle and small land-owners, the White Revolution facilitated the creation and expansion of large agribusiness, at detriment of all other cultivators. Mohammad Reza Shah’s call for social renewal found large-scale opposition, led by sections of the clergy, including Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The protest went down in history under the name of the ‘June 5 Revolt (Panzdah-e Khordad)’. It was severely repressed and Khomeini was sent into exile, the start of a long journey that would see him return to Iran only in February 1979. In his book, Islamic Government, Khomeini also writes about the Shah’s approach to illicit drugs and the adoption of the death sentence for drug offences:

I am amazed at the way these people [the Pahlavi] think. They kill people for possessing ten grams of heroin and say, ‘That is the law’ … (I am not saying it is permissible to sell heroin, but this is not the appropriate punishment. The sale of heroin must indeed be prohibited but the punishment must be in proportion to the crime). When Islam, however, stipulates that the drinker of alcohol should receive eighty lashes, they consider it ‘too harsh.’ They can execute someone for possessing ten grams of heroin and the question of harshness does not even arise!Footnote 102

More royalist than the king, more catholic than the pope, the Iranian state was also more prohibitionist than the leader of drug prohibition, the United States. The authorities turned this model into a special Iranian fetish, a model for the supporters of ever-harsher punishments against drug consumers worldwide. The side effects surfaced promptly. With harsher punishments against opium (and drugs in general), harder drugs gained popularity, with their accessibility, too, widening. As an old drug policy motto says, ‘the harder the enforcement, the harder the drugs’. With stricter control, harder drugs became available to the public at the expense of traditional drugs such as opium, a rationale that goes also under the name of the ‘Iron Law of Prohibition’.Footnote 103 In 1957, two years after the entry into force of the prohibition, a man was hospitalised for heroin abuse after being found in the Tehran’s Mehran Gardens.Footnote 104 It is the first reported case of heroin ‘addiction’ in Iranian history. The appearance of heroin signalled the changing social life of drugs over this period and in the following years.

Heroin was more difficult to detect, easier to transport for long distances, more lucrative with higher margins of profit and at the same time, with a much stronger effect than opium. It required no specific space for its use and, unlike opium, did not have a strong smell, which could attract unsolicited attention. Yet, heroin had no place in popular culture, neither as a medical nor recreational product and its repercussions on the user’s health were far more problematic than opium and shireh. If opium had an ambiguous status within Iran’s table of values and social habitus, being simultaneously medical, ritual and indigenous, heroin incarnated the intrusion of global consumption behaviours in the pursuit of pleasure and modernity.

By that time, the state regarded the question of ‘addiction’ as an epidemic that had to be isolated, as if it were cholera or the plague. Heroin instead instantiated, in the vision of the critics of the Pahlavi regime, a paradigmatic case of what intellectual Jalal Al-e Ahmad would call ‘Westoxification [gharbzadegi]’. The words of Jalal Al-e Ahmad, without referring to heroin directly, echoed the way heroin gained popularity among the urban modernist milieu. ‘Gharbzadegi is like cholera’, he writes, ‘a disease that comes from without, fostered in an environment made for breeding diseases’.Footnote 105 The environment to which the author refers, was the modernisation programmes promoted by Mohammad Reza Shah during the 1960s and 70s, which, along with globalising trends in cities, produced a changing flow of time: faster transportation, less reliance on the land-based economy, exposure to Western industrial modes of consumption, with technology acquiring an ever-more-dominant role in people’s lives, and individuality as the meter of being in the world. Life changed, together with a change in epoch, and life, at least for those exposed more directly to these changes.Footnote 106 To this contributed Shah’s so-called ‘White Revolution’ starting from 1963; the mass exodus from villages to urban centres, Tehran predominantly, signified an epochal change in the life of Iranians, at all levels, and the acquaintance with forms of sociability, consumption and recreation that differed substantially from that of rural communities. Inevitably, consumption patterns (including that of psychoactive, narcotic substances) changed in favour of modern substances.

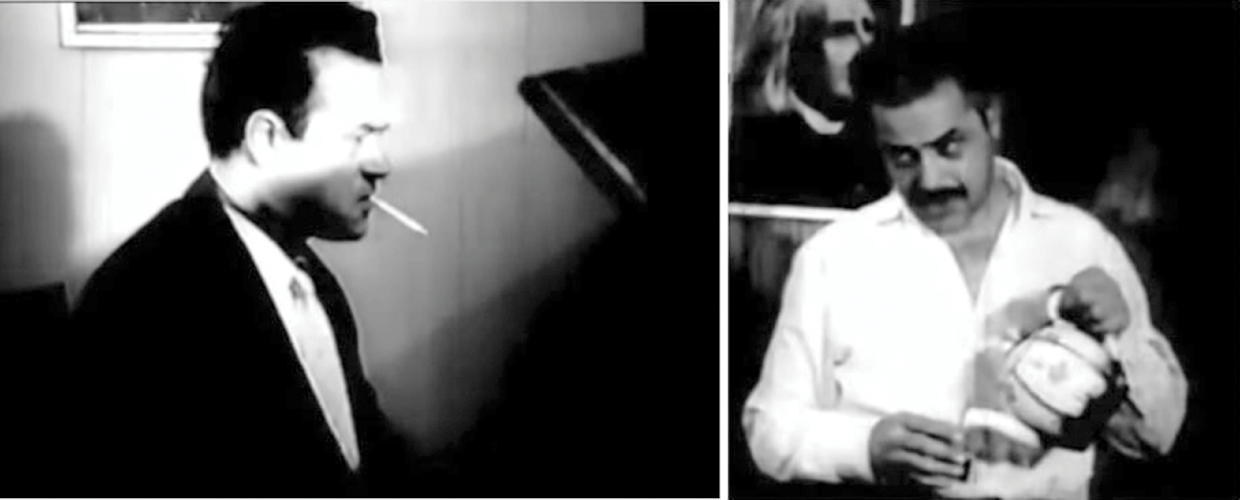

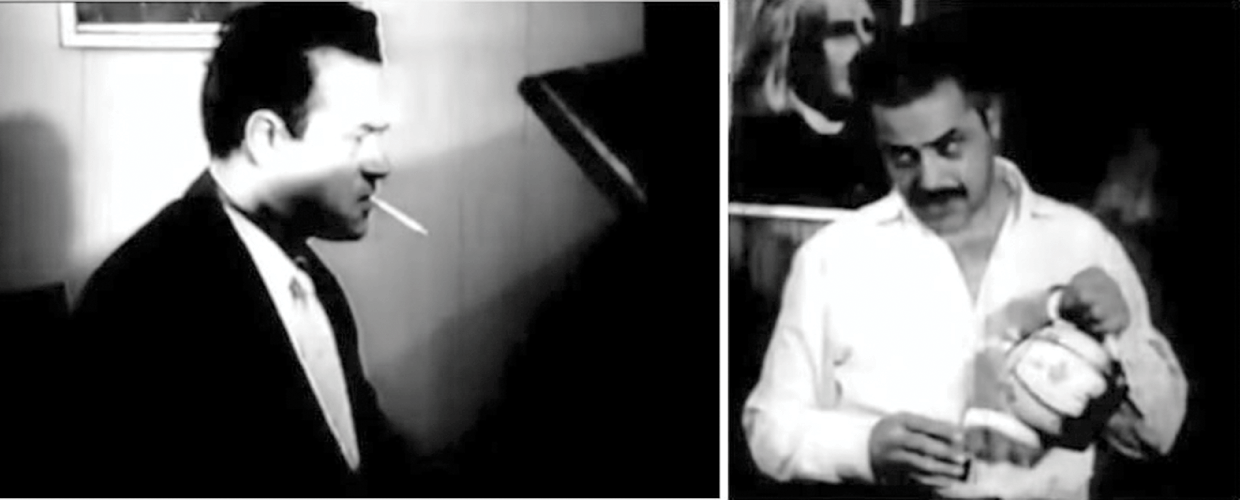

According to Al-e Ahmad, Westoxification occurred through the impotency of indigenous models of consumption and production faced with Western supremacy in technology, industry and trade. Upper-class young people often embraced the nascent counterculture of the 1960s, where it also coincided with the ascent of heroin culture in Europe and North America. Heroin use in Iran did not enter into the practice of the ordinary people at least up to the end of the Pahlavi era, but remained a rather elitist pastime, given the higher price and its availability in urban areas.Footnote 107 Examples of this genre of life are provided by films such as Mohammad Ali Ja‘fari’s The Plague of Life, or Morphine (Afat-e Zendegi ya Morphine, 1960), which portrays the life and fall of a wealthy, modern(ist) man, Hamid, well-respected by family and society, and deceived by a beautiful cabaret singer (Shahla Rihali) to collaborate with a drug trafficking organisation, because once he injects morphine (or heroin), he is at the mercy of his dealers and meets all their requests just for another shoot. Hamid, who prior to the encounter with morphine used to wear impeccable black suits, suddenly metamorphoses into a southern Tehrani luti, with an unclean shirt and facetious mannerisms. From being a gifted classical piano player, he is transformed into a moustached baba karam, who drinks black tea and plays only folk music (Figure 2.2).Footnote 108

During this period, the problem of drug (ab)use experienced an evolution and a complication. New drugs and new social groups entered the illegal economy, blurring the boundary of legality. Following the 1955 prohibition law, organised criminal groups entered into the world and mythology of Iran’s drugs politics. Secret laboratories mushroomed across the country, with the northwest Tabriz and Malayer, becoming a key production zone. Prohibition made the business of opiates highly profitable and persuaded groups of ordinary people who previously had little contact with the opium economy to set up production lines of morphine and heroin. In the police accounts, bakers, butchers and other ordinary workers used their workplace, house or farmhouse to produce amounts of opium derivatives and to sell it to traffickers.Footnote 109 By using opium smuggled into Iran from Afghanistan, or morphine base coming southward from Turkey, ‘heroin chemists’ developed underground networks of procurement and production.Footnote 110 A contemporary commentator acknowledged that the process of transformation ‘is not more complex than making a bootleg of whiskey in the United States’, a similarity that recalls the early days of US prohibition and the production of moonshine. At times, heavy armed confrontations occurred, especially when the traffickers were members of tribes or Afghans. For example, in 1957, an eleven-hour shooting battle broke out between the Gendarmerie (in charge of anti-narcotics) and the Kakavand Tribe, in the Kurdish town of Kermanshah, leaving eighteen tribesmen dead and forty-five wounded.Footnote 111 These outbursts of war-like violence heightened the sense of crisis that characterised the world of drugs, unprecedented for the Iranian public. Increased confrontation signified also that the financial bonanza of heroin trafficking had soon established international connections between local drug business and a transnational network of associates that reached the wealthy markets of the West.

The road to hell is paved with good intentions. That is not the case for the Pahlavi state. At the time when FBN advisors advocated in favour of Iran’s ‘selfless effort’, the American intelligence was also well informed about the Shah’s acolytes’ role in the international narcotic trade.Footnote 112 Gingeras reports that among the families directly involved in the narcotic affairs, apart from the Pahlavi, the CIA had mentioned the ‘Vahabzadeh, Ebtehajh, Namazee and Ardalan families’.Footnote 113 The shah’s twin sister, Princess Ashraf Pahlavi, had been allegedly involved in cases of narcotics trafficking and critics of the Pahlavi regime associated her with international criminal organisations. It was reported that in 1967, while on her way out of Geneva airport, Ashraf’s luggage was searched by the Swiss antinarcotics police, who allegedly found large amounts of heroin. Because of her diplomatic immunity, she was not prosecuted, but the international media covered the event in-depth, causing a scandal. Swiss and French newspapers spread the news about the incident, although official accounts have so far remained contested, especially by supporters of the Pahlavi monarchy. Ashraf sued Le Monde for these allegations and eventually won her libel case, having the story retracted.Footnote 114

Two other high-ranking officials had already been involved in a similar case. In 1960, the Swiss authorities warned of an Iranian national, Hushang Davvalu, suspected of shipping heroin into Europe. Ten years later, the police searched his house in Switzerland, where they found narcotics. Davvalu, who suffered from heart problems, was allowed to return home to Tehran.Footnote 115 Shah’s two brothers, too, were seemingly embroiled in the trafficking business. Hamid-Reza Pahlavi, the younger brother, is described in the account of the SAVAK as ‘having established in Takht-e Jamshid Street a headquarter, which used air companies to smuggle drugs, especially opium from outside the country into Iran, to produce heroin and then distribute it in Tehran and other cities’. The document describes also the involvement of high officials in the army who at times escorted the prince in his business trips. Hamid-Reza reached considerable fame to the point that the best heroin available in Tehran, in the 1960s, was known as heroin-e hamid-reza.Footnote 116

The other brother of the Shah, Mahmud-Reza, had also been caught up in the business. A bon vivant with a habit for opium and heroin, his relation with the Shah was strained and he was forbidden to participate in events at the royal court.Footnote 117 Since 1951, American officials have also been observing the movements and affairs of Mahmoud-Reza across the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. In February of that same year, Charles Siragusa, an experienced investigator of the FBN, spotted the prince ‘in a purple Cadillac with two beautiful women’ in Hamburg. The FBN discovered that Mahmud-Reza, under the alias Marmoud Kawa, smuggled heroin between Tehran, Paris, New York and Detroit, but the United States never followed up the lead in this case and instead arrested an Armenian associate of the prince, who operated a network, among whom were part also Iran’s counsels in Brussels and Cairo.Footnote 118 Thence, Iran’s diplomatic corps acquired the reputation of a drug trafficking network, despite attempts to cover up the scandals.

As previously said, US regional interest in the Middle East and the ongoing Cold War priorities prevented the FBN from disclosing the vast network of international heroin trafficking that operated under the Pahlavi family. The state itself remained in a paradoxical position: it hardened its drug laws, it militarised its drug control strategy and expanded its intelligence networks through anti-narcotic cooperation with the USA, but it acquiesced in not interfering with high-calibre heroin trafficking networks, often connected or known to the royal court. Iran became the regional machinery of US anti-narcotic strategy, through intelligence and information sharing, but also one of the main hubs for illegal narcotics in the region.Footnote 119

The means of enforcement of the drug laws improved steadily, the number of people punished for drug offenses increased dramatically, and prison populations reached unprecedented levels with administrative costs becoming a burden in budgetary allocations. Welfare for drug rehabilitation remained weak and the promise to uproot drugs from society sounded like a farce. In 1969, however, the government overturned the 1955 opium prohibition and established a regulated system of opium distribution and poppy cultivation. This occurred, most symbolically, when newly elected US president Richard Nixon declared the beginning of the ‘War on Drugs’.

Iranizing Prohibition?

The second half of twentieth century saw prohibition of drugs turning into a central issue in the global political debate. Intermingling of domestic and foreign affairs in drugs politics was the rule. Nixon’s call for a ‘War on Drugs’ influenced the discourse on illicit drugs across the globe. Indeed, US domestic politics had its leverage over international narcotics control. In his bid to win the US election, Richard Nixon had to defeat two enemies: the black voter constituency and the anti-war left, both galvanised by the vibrant movements of the late 1960s. As his former domestic policy advisor revealed in 2016, ‘we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities’.Footnote 120

As the United States embraced a more systematic prohibition, its close ally the Shah seemed to go in another direction. Counter-intuitively, the Iranian government introduced a groundbreaking policy, which had few systematic precedents globally and which apparently defied, on its own terms, the prohibitionist regime. In 1969, the Iranian government re-introduced state-supervised poppy cultivation and opium production and, crucially, opium distribution programmes on a mass-scale. The move occurred for several reasons, the main being the refusal by Iran’s neighbours, Turkey, Afghanistan and Pakistan, to eradicate their local production of opium, most of which passed through Iran, with a considerable part of it being turned into smoke by Iranians. In the words of the former Minister of Health Saleh, ‘gold goes out, opium comes in’,Footnote 121 with capital flight becoming a serious threat to economic development. Payment for opium depleted the gold reserves over the 1960s. Moreover, the government sought to decrease the economic burden of its anti-narcotic strategy, which had caused hardships for families whose breadwinner had been incarcerated for drug offences. An eightfold increase in heroin confiscation occurred between 1964 and 1966, prompting the government to reconsider the feasibility and effectiveness of the prohibition of opium. Heroin, a more dangerous substance but easier to transport and to consume, had become popular among an increasing number of citizens.

The government considered the 1969 drug law reform as a fresh start for the country’s drug strategy. The judicial authorities granted amnesty to people condemned under the 1955 drug law and the government introduced a vast medical system of drug treatment and rehabilitation, a model that resembled in its vision the ‘British model’ of heroin maintenance, but which differed radically from it in its quantitative scope.Footnote 122 It also made the promise to the United States that Iran would reintroduce opium prohibition once Turkey and Afghanistan had done the same.Footnote 123 But despite the Turkish ban on opium between 1969 and 1974 – which occurred under heavy US pressure on Ankara – poppy fields flourished undisturbed in Iran up to the fall of Shah in 1979.

The legendary ‘coupon system’, which is still recalled by many elderly Iranians, permitted the issue of vouchers to registered opium users. The new law granted consumption rights to two main groups. The first one was that of people over the age of sixty who would receive their ration after approval of a physician. The other group was that of people between the age of twenty and fifty-nine, who manifested medical, psychological symptoms for which opium could be used or who could not give up their opium use, for which the state assumed the responsibility to supply them with opium. The symptoms for which one could receive the coupon, included headache, rheumatism, back pain, depression, arthritis, etc., assessed by a governmental panel under the Ministry of Health. A consumer could purchase a daily dose of opium (between two and ten grams) from a licenced pharmacy or drug store.Footnote 124 The GP or the pharmacy then issued an ID card with a photograph, personal particulars, the daily amount of opium, and the pharmacy from which he/she should secure the opium ration. The public had access to two kinds of opium. One of a lower standard, which the government took from opium seizures of illicit traffic, coming mostly from Afghanistan and to a lesser extent Pakistan, costing six rials per gram; and the other, known for its outstanding quality – sometimes recalled as senaturi (‘senatorial’) – produced in the state-owned poppy farms, priced at seventeen and a half rials per gram.Footnote 125

With the comfort of guaranteed availability of opium, the registered user could walk to a convenient pharmacy and, at a price intended to annihilate the competition of the illegal market, purchase the highest quality of opium, worldwide. By 1972, there were about 110,000 registered people out of an estimated total population of ca. 400,000 opium users; in 1978, about 188,000 with 52 per cent of those registered under the age of sixty.Footnote 126 Those who did not register could buy opium, illegally, from registered users, who often had amounts in excess of their need and could re-sell it, or access the illicit market of Afghan and Pakistani opium, which remained in place especially in rural areas. The figure of the ‘patient-pusher’ appeared in the narrative of opium,Footnote 127 with an intergenerational mix where elderly opium users would register for the coupon in order to avoid younger users having to rely on the illegal market, or to make some marginal profit from reselling the coupons.Footnote 128 To have opium at home, after all, was part of the customs of greeting hosts and a sine qua non in areas such as Kerman, Isfahan and Mashhad.Footnote 129

The illegal market did not disappear overnight; in areas in which the state had limited presence, people kept on relying on their networks. People living in villages, for instance, witnessed very little change after the 1969 policy or, for that matter, any previous policy. Distances were great, physicians few and distribution networks weak. Women, too, had a tendency not to register (although they did in some case), mostly due to the negative perception of female opium smokers, especially when young.Footnote 130 The public perception was that working classes registered for the coupons, given that opium dispensaries stood in less wealthy areas, especially in Tehran. In reality, bourgeois classes benefited from the distribution network too. But only a small proportion of the total population registered.

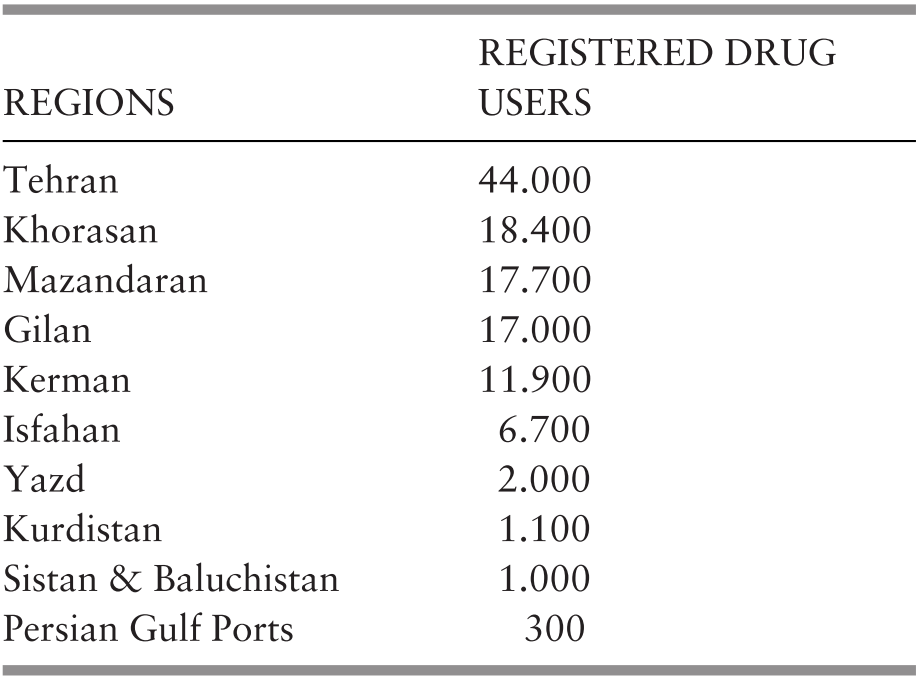

Treatment and rehabilitation facilities were also insufficient. The main hospital for the treatment of drug abuse in Tehran, the Bimarestan-e Mo‘tadan (Addicts’ Hospital), had only 150 beds in 1970, while in the rest of the country lack of infrastructures was even more blatant.Footnote 131 The private sector provided treatment services, including psychiatric and psychological support, but mainly addressed the urban bourgeois class, who could afford their higher fees.Footnote 132 The oil boom of the early 1970s – the grand leap forward of Iranian politico-economics – produced limited effects on state intervention. The majority of registered users were in the urban centres of the north, in particular in Tehran and the Caspian region, whereas areas with a historical connection to opium and the poppy economy had significantly lower numbers of registered patients (see Kerman). People with access to opium without the mediation of the state opted for the illegal market.

By the mid -1970s, drugs and politics intertwined because the royal court had firstly been accused of operating an illegal network of drug trafficking and, now, had become the main legitimate provider of narcotics to the population (Table 2.2). Socially and culturally, the presence of drugs was also conspicuous. The International Conference of Medicine, which took place in the northern city of Ramsar in 1971, dedicated its entire convention to the issue of addiction. Its proceedings advised the government to ban poppy cultivation or to keep it at a minimum required for essential medical needs for the certified drug addicts. Moreover, it suggested stopping the coupon system out of the risk of opium diversion to the general population and the widespread over-prescription practiced by doctors.Footnote 133 The government refused to take either of these suggestions and the coupon system lived up to the days of the Islamic Revolution in 1979.

The 1969 drug law, however, was not dissonant with global prohibitionist discourse. Since the 1920s, UK doctors had prescribed heroin to patients who were dependent on the substance. In 1967, the Ministry of Health instructed doctors to continue this practice to prevent the spread of heroin trafficking in the UK, despite increasing pressures against it.Footnote 134 The model allowed an opiate abuser to seek medical support in special clinics, housed in hospitals and under the supervision of psychiatrists. The fundamental difference in the 1970s was the quantitative dimension of the Iranian programme, which numbered hundreds of thousands of people, compared to the UK model which accounted for a mere 342 in 1964.Footnote 135 Similarly to the UK, addiction was reframed as a disability and not simply a disease, with its consequences bypassing the simple individual and being borne by family and society.Footnote 136 The Iranian government made the National Iranian Society for Rehabilitation of the Disabled the institution in charge of treatment and maintenance of drug users.Footnote 137 In this regard, the programme was not a niche attempt to control a marginal population, but a vast societal endeavour with the purpose of addressing a public health concern. Neither it was a move towards drug legalisation or comprehensive medicalisation of the drug use. Instead, it embodied a different form of prohibition, the effect of which touched mostly on poorer communities.

The 1969 law disposed that drug trafficking crimes needed to be judged, not by civilian courts, but by military courts. This upgrading of the security sensitivity on the narcotic issue can be partly interpreted as the Shah’s signal to his closest ally, the United States, of Iran’s sincere pledge to stop the flow of heroin; and partly as a means to buttress coercive means against those operating in a terrain which was exclusively the turf of the state, namely opium production.Footnote 138 A CIA memorandum reported that ‘Tehran has embarked on a stringer smuggling eradication program’, with more than ninety smugglers executed between 1969 and 1971.Footnote 139 In 1975, it was estimated that there were 6,000 prisons spread throughout Iran, with drug offenders being still the largest population.Footnote 140 Instead of establishing a system of regulation, with an underlying non-prohibitionist mindset, the Iranian state adopted a double form of intervention aimed ultimately at the exclusive control of the narcotic issue by itself, both on domestic distribution and production. In practice, competing groups with close ties to the state – one could call them the rhizomes of the state? – such as corrupted elements of the court, transnational elites connected to smugglers, and drug producers inside and outside Iran outplayed the state’s drug strategy to their own benefit.

Conclusions

Timothy Mitchell writes that ‘the essence of modern politics is not policies formed on one side of this division being applied to or shaped by the other, but the producing and reproducing of these lines of difference’.Footnote 141 In this regard, Mitchell’s historicisation is reminiscent of Foucault’s genealogical approach: it is not a ‘quest for the origins of policies or values, neither is ‘its duty to demonstrate that the past actively lives in the present’.Footnote 142 The task of genealogy, paraphrasing the French philosopher, is to record the history of unstable, incongruent and discontinuous events into a historical process that makes visible all of those discontinuities that cut across state and society.Footnote 143 This chapter traced a genealogy of prohibition in modern Iran and its relation to the process of modern state formation. The birth of the drug control machinery in Iran dates back to the aftermath of the Constitutional Revolution (1906–11) and forms part of the wider global inception of prohibitionist policies in the early twentieth century. Sponsored by the United States, the Shanghai Conference in 1909 represented a first global effort to draw homogenising lines of behaviour (sobriety, temperance, order: legibility) – haphazardly – into the body politic of the world system. Opium, as such, symbolised an anti-modern element, a hindrance in the modernisation destiny of any country. Opium, and addiction as its governmental paradigm, embodied a life handicapped by dependence, impotency, apathy and above all, slavery. Within a matter of decades, the adoption of this discourse produced apparatuses of narcotic control and prohibition. Accordingly, Iran went through a period of inconsistent experimentation, both for the state as a governmental machinery, and the people as interlocutors of and experimenters with the phenomenon of illegal drugs. In detailing these processes, the chapter unmasked the Pahlavi state’s relation to social and political modernisation through an analysis of this period’s drugs politics. This setting provided the contextual prelude to subsequent socio-political and cultural transformations that accompanied and followed the Islamic Revolution of 1979.

In the opium popular mythology, an apocryphal story narrates the discontinuities described at the close of this chapter. Four public officials, connoisseurs of opium (tariyak shenas) and professional opium users (herfei), would go every morning in the Opium Desk within the Office of the Treasury (dara’i) to test the quality of the state opium, before attaching the government banderole to those opium cakes up to standard for national distribution. With the revolution in 1979 and the closure of the Opium Desk, all four of them died because of khomari (hangover for the lack of opium).Footnote 144