1. Introduction

A recurrent quest in linguistic research is for an overarching analysis that will account for the semantic and syntactic characteristics of modality-bearing items. Chinese nengyuan zhu-dongci ‘modal auxiliaries’, such as yinggai ‘should’ and keyi ‘can’ (henceforth referred to as modals), are – like modals in English – typically located between a subject and its predicate. Hereafter, modals in this position are termed sentence-internal modals. Semantically, modality is generally categorized into three major types: epistemic modality, which expresses a speaker’s knowledge, assumptions, and estimations; deontic modality, which denotes permission, obligation, or rules involving prioritization; and dynamic modality, which denotes ability, volition, or circumstances (for an overview, see Portner Reference Portner2009).

Modals can express many possible readings depending the choice of conversational backgrounds (Kratzer Reference Kratzer2012), and Chinese modals in their canonical position express the same range of modality as modals in other languages do (Li & Thompson Reference Li and Thompson1981: 182–183). For example, the words yinggai and keyi each express two types, with yinggai being either epistemic, as in (1a), or deontic, as in (1b), and with keyi being either deontic (2a) or dynamic (2b).Footnote 2

The same type of multiplicity of meanings is also found in English modals:

However, unlike in English, some epistemic and deontic modals in Chinese may occur before the subject of a sentence. These henceforth are referred to as sentence-initial modals. In one early Chinese-grammar manual (Lü [1980] Reference Lü1999), most uses of sentence-initial modals were assigned to the category zhu-dong ‘auxiliary’, and some of its examples of such sentence-initial modal sentences are shown in (5), with my glosses and translations.Footnote 3

Sentences as in (5) have been understudied. The current consensus among scholars of Chinese syntax is that the two above-mentioned modal positions are associated through some version(s) of optional subject-raising (e.g. Lin & Tang Reference Lin and Tang1995; Tsai Reference Tsai2010, Reference Tsai and Shlonsky2015; Lin Reference Lin2011, Reference Lin2012; Chou Reference Chou2013): i.e. that such modals are raising verbs. However, that idea should be reconsidered, because sentences like (5) exhibit syntactic restrictions and semantic functions that are very different from sentences like (1) and (2). This paper presents new evidence that the distribution of modals is constrained by their designated positions (contra the subject-raising proposals) and that sentences like (5) express focus readings, whereas those like (1) and (2) do not.

Native Mandarin speakers exhibit a keen sense of when sentences featuring the two modal positions should and should not be used. Consider a scenario in which two friends, A and B, are chatting in B’s house. Speaker A hears the doorbell ring and asks B about it, as in (6A). If speaker B wants to answer the question with a sentence containing an epistemic modal to express their own epistemic estimation based on the doorbell ringing, the answer with a sentence-initial modal (6B) is felicitous, whereas (6B’) with a sentence-internal modal is not.

Answers to an out-of-the-blue question such as ‘What happened?’ have been referred to as broad focus or sentence focus, indicating that the span of focus involves a proposition, thus is different from the span of a predicate focus or constituent focus (cf. Lambrecht Reference Lambrecht1994; LaPolla Reference LaPolla1995). In a sentence like (6B), having considered why the doorbell is ringing, speaker B uses the sentence-initial modal yinggai ‘should’ to assert an epistemic judgment on a modalized proposition: i.e. B’s epistemic judgment that after hearing the doorbell ring that ‘Zhangsan should have bought a pizza and returned home, which is what B believes to be the most likely explanation of the ringing that is relevant to the common ground (cf. Stalnaker Reference Stalnaker2002). Another key characteristic of this type of propositional focus is that it does not require a presupposition that a proposition is already at issue (i.e. a prejacent). That is, speaker B does not have to know with certainty that Zhangsan is arriving with a pizza at the time of this conversation. Thus, the focus at issue is different from verum focus, which requires a prejacent (Höhle Reference Höhle and Jacobs1992).Footnote 4

In this paper, the crucial characteristic that I try to account for is that (6B), with its sentence-initial modal, exhibits a strong sense of assertion on the modalized proposition that (6B’) does not share and that such a sense of modal assertion is obtained syntactically.Footnote 5 , Footnote 6 Hereafter, the type of sentence focus expressed in (6B), not requiring a prejacent, is labeled a propositional focus, to distinguish it 1) from verum focus, 2) from broad sentence focus that does not express assertion, and 3) from constituent focus, whose span is smaller than a proposition. Specifically, this paper presents new empirical evidence that sentence-initial modals are moved to the complementizer domain (CP) (Section 4), associated with a focus operator, marking the focus denotation of its c-commanding associates (Section 5), whereas sentence-internal modals form the canonical modalized sentences. As such, the analysis presented here assumes that the focus c-commanding association (Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1972) is critical in Chinese, whereas the specifier-head association happens covertly, as in Chinese wh-question formation (Huang Reference Huang1982; Tsai Reference Tsai1994).

This new proposal not only accounts for native speakers’ intuition and choices of modal sentences but also is important theoretically. Previously, based on an assumption that modals are lexical verbs, many researchers have relied on subject-raising to account for Chinese’s two modal positions. However, as shown in Section 2, several contrasts cannot be explained by such an approach, and an internal merge of modals may better account for the phenomenon at issue. Therefore, Section 3 presents this paper’s adoption of, first, a cartographic approach to deriving both sentence-internal modals (cf. Cinque Reference Cinque1999) and sentence-initial modals (cf. Rizzi Reference Rizzi and Haegeman1997) and, second, Rooth’s (Reference Rooth1985) alternative-semantics framework for expressing two different types of interpretations associated with modal sentences in Chinese. The remainder of this section reveals that Mandarin Chinese, although profoundly different from Germanic and Romance languages typologically, presents a neat example of the interplay of these syntactic-semantic mechanisms. Two main theoretical implications of this paper’s central proposal include, first, that features of information structure (such as focus) are formal features in syntactic derivation (cf. Rizzi Reference Rizzi and Haegeman1997; Miyagawa Reference Miyagawa2010) and, second, that identifying Chinese modals as distinct functional categories in the tense phrase (TP) domain (cf. Pollock Reference Pollock1989) provides an important new perspective from which to reconsider a current consensus in Chinese syntax: that the absence of V-to-T raising (Huang Reference Huang1993; Tsai Reference Tsai1994) subsumes the absence of T-to-C raising. New data presented in Section 4 show how modal raising interacts with scope-bearing heads in the TP domain. As such, with regard to the Move and Agree mechanism (Chomsky Reference Chomsky and Kenstowicz2001), this study supports the view that a probe’s strong features trigger the head-movement of its c-commanding goal.

New evidence presented in Section 5 shows that, in both the matrix and embedded clauses, sentence-initial modals are relevant to the valuation of focus features in CP and that this covert association interacts with wh-constituents, resulting in focus-intervention effects, just like other focus constituents do with wh-constituents (cf. Beck Reference Beck1996). Sentence-internal, canonical modals, in contrast, do not trigger such focus-induced interactions. Section 6 then elaborates types of focus that sentence-initial modals can express; and Section 7 presents this paper’s conclusions.

2. External or internal merge?

The existing literature on modal syntax does not consider differences in focus interpretation between sentences with sentence-internal modals, e.g. (1) and (2), and those with sentence-initial modals, e.g. (5). Instead, these two modal distributions are claimed to be derived by optional subject-raising in a biclausal structure, such as a vacuous structural alteration resulting from optional subject-to-subject raising in TP (Lin & Tang Reference Lin and Tang1995; Lin Reference Lin2011, Reference Lin2012; Tsai Reference Tsai2010, Reference Tsai and Shlonsky2015); optional topic A-movement in TP (Chou Reference Chou2013); or optional topicalization of a subject from the matrix-subject position (Specifier of TP) to the domain of the CP (Tsai Reference Tsai2010, Reference Tsai and Shlonsky2015). Each of these three proposals has some theoretical merit. However, empirical examination suggests that all three are ripe for reconsideration.

Proceeding from an assumption that null expletives in Chinese can be freely inserted when the subject is not raised to the matrix-subject position, Lin & Tang (Reference Lin and Tang1995) offered two accounts of the derivation` of the raising type of modals.Footnote 7 The first was that such modals are subcategorized as having a finite or non-finite complement, with the subject raising only when the complement is non-finite (7). But this would mean that the less commonly used sentence-initial modal (<3% in corpusFootnote 8) would be the only method of deriving Chinese modal sentences, which is contrary to observations.

Lin & Tang’s (Reference Lin and Tang1995) second account posits that the raising type of modal in Chinese is obligatorily subcategorized for a finite complement and that the Infl(ection) head of this finite clause optionally assigns the nominative Case. As such, the subject rises when the embedded finite Infl does not assign a nominative Case, and the subject does not rise when it receives the Case from the embedded finite Infl. Accepting this biclausal mechanism for the raising of subjects out of a finite clause, Lin (Reference Lin2011, Reference Lin2012) and Chou (Reference Chou2013) both claimed that the subject optionally rises from an embedded finite clause, either for special extended projection principle (EPP) features or topic features.Footnote 9 Another challenge to the subject-raising account arises if one accepts either of two claims: 1) that a null expletive can be freely inserted as the matrix subject or 2) that an embedded TP can optionally assign Case. Although optional Case assignment may be useful for explaining other phenomena (cf. Bošković Reference Bošković, Lima, Mullin and Smith2011),Footnote 10 the raising-verb account of epistemic and deontic modals results in incorrect predictions. That is, if modals took a raising structure and were initially merged in the sentence-initial position, sentences like (8) could further derive sentences like (9) after subject-raising. But, assuming that the same mechanism generates sentences like (9a) and (9b), it is unclear what prevents the construal of sentences like (9a). These observations also weigh against the idea that sentence-initial modals are sentential adverbs. Again, why adjunction is allowed in one, but not the other, is not immediately apparent.

Implicitly rejecting the lexical(-verb) analyses, Tsai (Reference Tsai2010, Reference Tsai and Shlonsky2015) argued that modals expressing different types of modality are realized in different syntactic domains. As shown in (10), epistemic modals (MPEpi) are in the CP domain, deontic modals (MPDeo) are in the Infl domain, and dynamic modals (MPDyn) are under vP.

As such, Tsai’s (Reference Tsai2010, Reference Tsai and Shlonsky2015) proposal neatly incorporates both the traditional functional Infl and lexical-verb analyses for Chinese modals. For the present purposes, one of Tsai’s claims is of particular concern. Following Diesing (Reference Diesing1992), it is proposed that a subject preceding a deontic modal is a definite outer subject, while a subject following such a modal is a nonspecific inner subject. Nonetheless, it should be noted that the subject following a deontic modal can often be a pronoun or proper name, such as in (5b) and (5c); and, being definite and referential, these conflict with what is required for an inner subject. Additionally, according to Li (Reference Li1998), a quantity-denoting nominal that is not referential can be a matrix subject – e.g. the nonspecific quantity phrase ‘two people’ in (11) – potentially occupying the outer subject position in (10).

Another phenomenon that has been reported in the literature, but has yet to be accounted for, is that Chinese modals with different types of modality can co-occur but only in a fixed order.

The contrasts illustrated in (12) reflect the semantic order of modals reported in prior literature, i.e. epistemic scopes over deontic (for a review, see Portner Reference Portner2009). The present study proposes that syntactically expressing such a modal order through functional projections of modals in the TP domain (cf. Cinque Reference Cinque1999) not only captures the modal hierarchy shown in (12) but also provides a unified structural explanation for data like (8) and (9). Section 3 presents this proposal: a modal-raising mechanism, and in Sections 4 and 5, new evidence of syntactic head-movement intervention and of semantic focus intervention effects highlights how the current proposal provides a better and unified explanation of these data.

3. The Proposal: Modal raising for focus

This paper proposes that changes in word order in Chinese are not ascribable to an optional or free derivation in syntax but are required by syntactic-feature computations to express specific information structures, that is, modal raising for focus.

Based on the similarities in the typical use of English and Chinese modals, the canonical position of Chinese ones – i.e. between a subject and its predicate – is here assumed to be generated in the split-Infl domain à la Pollock (Reference Pollock1989). This is in accordance with the traditional view of modals as functional categories in Chinese (Huang Reference Huang1988; Hsu Reference Hsu2005, Reference Hsu2015; Hsu & Ting Reference Hsu and Ting2008; Tang Reference Tang1990; Tsai Reference Tsai2010, Reference Tsai and Shlonsky2015; for English, see Chomsky Reference Chomsky1957; Roberts Reference Roberts1985). The tree diagram in (13) summarizes this proposal. Three structural assumptions are as follows. First, if one accepts that there is a c-command requirement for focus association (Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1972), focus-marking modals occur in the sentence-initial position to c-command its focus associate (e.g. TP, for propositional focus). Second, if one accepts the split-CP hypothesis (Rizzi Reference Rizzi and Haegeman1997), then sentence-initial modals can be derived by internal merge to the Focus Phrase (henceforth, FocusP) in the CP domain.

And third, proceeding from the assumption of Agree (Chomsky Reference Chomsky and Kenstowicz2001) – i.e. that an Agree relation should be established between a probe category that carries an uninterpretable feature, and a goal category (c-commanded by the probe) with a corresponding feature (Pesetsky and Torrego Reference Pesetsky, Torrego, Guéron and Lecarme2004) – it is proposed that the head of the FocusP bears a strong, uninterpretable focus feature, uFocus (Miyagawa Reference Miyagawa2010); probes a goal (in this case, a modal) with corresponding interpretable features; and triggers the head movement of the modal for feature valuation.

Given that head movement would be blocked by intervening (c-commanding) heads of the feature-relevant type (Rivero Reference Rivero1994; Li, Shields & Lin Reference Li, Shields and Lin2012), this analysis gains initial support from the order-restriction on double-modal sentences that is discussed in Section 2. That is, based on the structure in (13), to fulfill Agree as required by the Focus head, a goal (keyi) moves from its canonical position to a surface position, crossing another modal (yinggai) that counts as an intervening head containing the same type of feature, i.e. head-movement constraint. In contrast, moving the higher modal yinggai ‘should’ does not violate the constraint, because no intervening head blocks the movement. The following sections show that the head-movement mechanism is entertained in this proposal because interpretations of the two types of Chinese modal sentences differ only in one respect: that sentence-initial modals emphasize a modalized proposition, while typical modalized sentences do not carry such emphasis; moreover, this word-order difference triggers syntactic head-movement constraints with respect to other scope-bearing heads (Section 4) as well as semantic intervention effects with respect to focus elements (Section 5).

To account for various modal interpretations, Kratzer (Reference Kratzer, Eikmeyer and Rieser1981, Reference Kratzer2012) proposes that modal sentences are inherently relational – combining the modal base and the modal background (proposition) – and assuming a set W of possible worlds, one can view propositions as subsets of W, and the selection of the modal base determines the modal flavor. For example, a deontic modal like can will return true if and only if all the worlds in the set arrived at by taking the intersection of modal base applied to the evaluation world are worlds in which the proposition is true, as in (14a) (Kratzer Reference Kratzer2013: 192), and the same applies to an epistemic modal like must except that it expresses epistemic quantification, as in (14b).

The same range of modal readings are available and expressed by modals in the post-subject positions in Chinese, just as their English counterparts; however, such standard semantic mechanism that derives modal interpretations, although important, is insufficient in expressing that both types of Chinese sentences at issue involved modality but differ in terms of their focus denotation. Therefore, the framework of Focus Alternative Semantics is adopted to present my analysis of propositional focus. According to Rooth (Reference Rooth1985: 14), a focused constituent (

![]() $ a $

) contains an ordinary semantic value

$ a $

) contains an ordinary semantic value

![]() and a focus semantic value

and a focus semantic value

![]() , which is involved with a set of alternative denotations that include

, which is involved with a set of alternative denotations that include

![]() as a member. For example, a focus-sensitive operator like only marks a focused constituent, quantifies over its associated alternatives, and results in a set of alternative propositions. Therefore, a focused constituent like John in (15a) is associated with a set of alternatives, such as {John, Bill, Ken, …}, resulting in alternative propositions (15b). Among such alternatives, only one – ‘John saw a man’ – is relevant, and the focus operator only excludes the others.

as a member. For example, a focus-sensitive operator like only marks a focused constituent, quantifies over its associated alternatives, and results in a set of alternative propositions. Therefore, a focused constituent like John in (15a) is associated with a set of alternatives, such as {John, Bill, Ken, …}, resulting in alternative propositions (15b). Among such alternatives, only one – ‘John saw a man’ – is relevant, and the focus operator only excludes the others.

Applying this framework of alternative semantics to the phenomenon at issue, and assuming Kratzer’s (Reference Kratzer, Eikmeyer and Rieser1981, Reference Kratzer2012) semantic account to modality, I propose that modals in the TP domain express typical modalized sentences and that when a modal occurs in the sentence-initial position, it is associated with the focus operator in FocusP, marking its c-commanding modalized TP as focus. For example, the pre-subject modal yinggai in (16) marks a TP (β) as focus – the assumed LF is shown in (16b) – and asserts that this proposition is the most likely among the alternatives (16c). Below, for ease of discussion, modalized sentences involved with propositional focus are translated with the frame ‘It is the case that…’ to distinguish them from typical modalized sentences.

The next question to be asked under the current proposal is how to account for sentences such as (17), in which another phrase is located before the sentence-initial modal. According to Rizzi (Reference Rizzi and Haegeman1997), a topic projection may dominate FocusP in the split-CP domain; therefore, the phrase before the sentence-initial modal – e.g. wancan ‘dinner’ in (17) – can be analyzed as a topic of the sentence.

This was also claimed by Lin (Reference Lin2011: 63), who noted that speaker-oriented adverbs in Chinese – such as tanbai-shuo ‘frankly speaking’ – do not occur between a subject and its predicate and only occur outside of TP, for example (18). Therefore, if an adverb test is applied to (17), then (19) can support the CP-topic status of wancan proposed here. While the current proposal naturally accounts for examples (17) through (19), it is worth noting that the ungrammaticality of (18a) argues against proposals that epistemic modals initially merge at CP and derive the subject-modal order through subject raising (e.g. Tsai Reference Tsai and Shlonsky2015).

4. Other syntactic intervening heads

If the current proposal is tenable, other TP-internal scope-bearing heads, and not just the modals, can be expected to block the proposed head-movement. Two pieces of evidence for this are presented in this subsection: negation, and emphatic shi in cleft.

4.1 Negation

The first piece of evidence involves the interaction of the scope of modals with the sentential negation bu ‘not’.Footnote 12 The examples in (20) show that an ambiguous modal yinggai expresses an epistemic reading if it occurs before the sentential negation bu but a deontic reading if it occurs after the sentential negation bu.

When a sentence-initial modal expresses propositional focus, the sentence with an epistemic modal properly contains the sentential negation in its epistemic interpretation; see examples (20a) and (21). However, a similar attempt fails with a deontic modal, because the original scope of (20b) does not hold, as in (22).

If it is assumed that sentential negation is a propositional scope-bearing head (Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1969) in the TP domain (Haegeman Reference Haegeman1995), then the different modal interpretations in (21) and (22) can be accounted for by the proposed head-movement constraint. In other words, raising the deontic modal to the sentence-initial position for focus scope is blocked by the sentential negation, whereas the epistemic modal – being located higher than the sentential negation – is free to raise.

4.2 Emphatic shi in cleft construction

The second piece of evidence for the proposed head-movement of modals involves emphatic shi (glossed as EMP) in Chinese cleft construction. Existing research on this construction has concentrated on sentences containing emphatic shi and sentence-final de (DE)Footnote 13 (Simpson & Wu Reference Simpson and Wu2002; Lee Reference Lee2005; Cheng Reference Cheng2008; Paul & Whitman Reference Paul and Whitman2008). Hole (Reference Hole2011), based on a review of prior studies of Chinese cleft, suggested that true cleft construction in Chinese exhibits an exhaustiveness reading, like English cleft (Paul & Whitman Reference Paul and Whitman2008; Hsu Reference Hsu2019). In other words, while shi…de sentences, as in (23a), exhibit an exhaustiveness requirement similar to the exhaustivity associated with cleft constructions in other languages (Szabolcsi Reference Szabolcsi1981; Kiss Reference Kiss1998; Hedberg Reference Hedberg2000), bare shi sentences, as in (23b), do not.

I follow Lee (Reference Lee2005) (in the spirit of Teng Reference Teng1979 and Huang Reference Huang1988) regarding this emphatic shi as a focus-sensitive marker syntactically realized in the TP domain, c-commanding its focus associate,Footnote 14 and assume that – like another focus-sensitive operator, only – the exhaustive feature is valued at FocusP in CP in LF.

This TP-internal functional head shi serves as another diagnosis for the head movement proposed in this study. When the modal yinggai – which can express either deontic or epistemic modality – occurs in a cleft sentence, it carries a strong suggestive deontic sense if it follows shi, as in example (24b), but an epistemic one if it precedes shi, as in example (24c).

Sentences like (24) illustrate two important points. The first is that a sentence-internal modal can be a part of the background of a cleft construction. The second is that, in a cleft construction, modals with different types of modality co-occur with shi in a fixed order: i.e. epistemic modals before shi and non-epistemic ones after it. This ordering restriction is not likely to be due to semantic, scope-related reasoning, given that both deontic and epistemic modalities can be expressed either in the background clause of the cleft focus, as in (25), or inside the clefted unit, as in the English examples in (26).

Interestingly, with respect to sentence-initial modals, a contrast is observed between epistemic and deontic modals in cleft construction. That is, epistemic modals can occur in a sentence-initial position but deontic modals cannot, as shown in (27).

If one adopts the subject-raising viewpoint, however, it remains unclear why modals can directly merge sentence-initially in one of these cases (27a) but not in the other (27b). Thus, reconsidering (24), a simple explanation for the contrast illustrated in (27) could be that raising a deontic modal to the sentence-initial position for focus requires passing emphatic shi, which counts as an intervening head that blocks the movement. On the other hand, raising an epistemic modal is acceptable because no intervening head is involved, as shown in (28).

Before concluding this section, it is worth pointing out that unlike cleft sentences, modals – even deontic ones – located in TP must precede the copula use of shi (which is assumed to be a two-place predicate, see Mendez Vallejo & Hsu, Reference Vallejo, Catalina and Hsuin press) (29a, b) and that a deontic modal can occur at the sentence-initial position (29c), in contrast to (27b), in which a deontic modal follows emphatic shi.

Though the structural restriction of modals in the cleft construction has already been carefully considered, the information packaging of sentences like (27a) should be approached cautiously. If the cleft focus zai Ouzhou ‘in Europe’ is prosodically emphasized, as it usually is, then (27a) is infelicitous as a direct response to a prior discourse, due to a conflict between different types and spans of foci co-occurring in it: specifically, the propositional focus marked by the sentence-initial modal and the cleft constituent. Nonetheless, because information structure dynamically reflects the updated common ground as a conversation proceeds (Stalnaker Reference Stalnaker2002), such sentences can be accommodated as involving a second-occurrence focus (cf. Büring Reference Büring2015), as shown in a mini-discourse like (30A, B) (more examples are discussed in Section 5). A similar situation has been reported for English (Hole Reference Hole2011). In a mini-discourse like (30C, D), the cleft focus unit in Paris in speaker A’s utterance may later occur in a context where a new focus is updated in the conversation: e.g. Paul split up in (30D) as a corrective focus used to reject the presupposition provided in (30C). Therefore, the cleft focus in (30D) is considered a second-occurrence focus and does not attract the same level of acoustic prominence as the major focus does (Büring Reference Büring2015).

For purposes of the current study, it is important that – while the second-occurrence focus is allowed – the derivation of focus-marking must still respect structural restrictions, as indicated by the contrast shown in (28).

In summary, the examples in this section have shown that TP-internal, scope-bearing, functional heads impose the same head-movement constraints as those observed in double-modal sentences. Section 5 demonstrates that sentence-initial modals are focus-sensitive, whereas TP-internal modals are not.

5. Sentence-initial modals and focus intervention effects

This section’s discussion is centered on focus-intervention effects (Beck Reference Beck1996), especially as a means of diagnosing covert feature associations. It presents evidence that sentence-initial modals marking a propositional focus intervene in the construal of a constituent focus (e.g. wh-questions and only-focus) and that TP modals do not.

Chinese wh-phrases are known to stay in situ, and wh-features are valued at CP in LF (Huang Reference Huang1982; Tsai Reference Tsai1994). When modals occur at the beginning of a wh-question, the resulting sentences are ungrammatical, as can be seen from example (31).

However, the occurrence of sentence-internal modals does not influence the grammaticality of the construal of a wh-question, as shown in example (32).

The contrast shown between (31) and (32) suggests that the sentence-initial and -internal modals may have different functions, as the former block wh-interrogative readings, whereas the latter do not, just as would be expected from the typical use of modals. The same contrast of grammaticality in matrix clauses between the examples in (31) and those in (32) can be found within an interrogative CP complement. According to Huang (Reference Huang1982), verbs such as xiangzhidao ‘wonder’ take an interrogative CP that licenses wh-questions inside that interrogative CP. With a neutral intonation, typical wh-questions with clause-internal modals, such as (32a) and (32b), can be embedded under xiangzhidao, such as (33), whereas sentences, such as (31a) and (31b), having sentence-initial modals, cannot, such as (34).Footnote 15

These comparisons of the clause-initial and clause-internal modals interacting with wh-questions show that such contrasts would remain mysterious if the modals were raising verbs and if modal constructions allowed an optional subject raising (e.g. Lin & Tang Reference Lin and Tang1995; Lin Reference Lin2011, Reference Lin2012; Chou Reference Chou2013; Tsai Reference Tsai and Shlonsky2015). In other words, these examples highlight the mystery of why wh-phrases are not compatible with modals in a structure before the alleged subject-to-subject raising occurs but then become acceptable after raising. This set of data also challenges Tsai’s (Reference Tsai2010, Reference Tsai and Shlonsky2015) analysis of epistemic and deontic modals: for it is reasonable to wonder why the alleged outer subject (preceding a deontic modal) and the topic (preceding an epistemic modal) can co-occur with an in situ wh-expression, as in (32) and (33), whereas the same outer subject (following an epistemic modal and, presumably, preceding a deontic modal) and inner subject (following a deontic modal) cannot, as in (31) and (34).

In the current analysis, sentence-initial modals are associated with a focus operator in CP that focus-marks the entire proposition. Therefore, when a wh-phrase is independent of the intended propositional focus marked by the sentence-initial modal, the sentence can be expected to be ungrammatical. This is probably due to the intervention effects of focus that have been proposed by Beck (Reference Beck1996, Reference Beck2006) and Kim (Reference Kim2002).

For example, Korean wh-phrases stay in situ – e.g. nuku ‘who’ in (36a). When another argument, such as the subject Minsu in the same example, is marked with a focus operator, -man ‘only’, the sentence becomes ungrammatical, as in (36b). It has been argued that this results from an intervention effect whereby a wh-phrase in situ cannot be c-commanded by a focus operator, as schematized in (35).

The intervention effects of focus can be remedied when the wh-phrase is moved out of the evaluation domain of a focus or a quantificational phrase (e.g. Hoji Reference Hoji1985; Takahashi Reference Takahashi1990; Beck & Kim Reference Beck and Kim1997; Tanaka Reference Tanaka1997; Tomioka Reference Tomioka2007). This scenario is exemplified by the contrast between (36b) and (37): the sentence is improved after the wh-phrase nuku-lûl ‘who-ACC’ is moved outside the valuation domain of the focused subject Minsu-man ‘Minsu-only’.

This type of focus-intervention effect is observed in Chinese as well (Yang Reference Yang2012). If the subject focus zhiyou Zhangsan occurs in the same sentence as the question about the wh-object shenme-dongxi ‘what-thing’, the sentence is ungrammatical because of the intervention effect of focus, as schematized in (39).

Much as in the Korean examples given above, the acceptability of sentences such as (38) is greatly improved after the wh-phrase leaves the valuation domain of the FocusP (40).

The current study proposes that the ungrammaticality of modal sentences like (41) can be accounted for in the same way. In other words, the propositional focus (i.e. TPFocus), as in example (42), marked by a sentence-initial modal (with FocOp) and the wh-phrase (as an unrelated quantificational element) co-occur in the same valuation domain of focus.

On this basis, one can predict that sentences like (41) will be improved significantly after the wh-phrase leaves the evaluation domain of the focus operator, as illustrated in (43), below. This example indicates that the interactions of clause-initial modals with wh-questions are similar to the interactions of other focus elements with such questions, thus confirming that sentence-initial modals are associated with focus marking.Footnote 16

Similar intervention effects are found in modalized sentences containing other types of focus, such as only focus. As the following examples show, a sentence-internal modal is compatible with only focus, for instance, zhiyou Xiaomei in (44a), but a sentence-initial modal is not (44b). Again, the acceptability of the latter type of sentence can be improved if the only-focus is moved out of the valuation domain of the sentence-initial modal, as in example (44c).

Examples of focus intervention effects involving sentence-initial modals are shown in examples (41) and (44b) and the remedied counterparts (examples (43) and (44c), respectively) show that such focalized interpretations and their associated focus operators need to be licensed by relevant C heads and that head raising of modals to relevant C heads does not prevent such heads from attracting in situ wh-phrase and focus operators, as long as the foci’s licensing are not mixed/crossed within the same CP.Footnote 17 If this account is tenable, it is expected that when the C that will license an in situ wh-phrase is different from the C that a modal is moved to, each of such association can be properly licensed.

Therefore, it is important to consider the nature of the structural interaction between wh-questions and the sentence-initial modals in other types of embedded clauses. According to Huang (Reference Huang1982), verbs such as juede ‘think’ are subcategorized for a declarative CP that cannot license wh-questions within itself – unlike verbs such as xiangzhidao ‘wonder’. For purposes of the current study, this structure provides a useful environment in which to examine the proposed focus-intervention effects. That is, because the licensing domain of wh-questions is not in the embedded CP of juede, that embedded CP should allow a clause-initial modal.

Example (45) shows that the embedded wh-phrases of a juede sentence are interpreted at the level of the matrix CP.

Interestingly, an ungrammatical sentence that contains both a sentence-initial modal and a wh-phrase becomes more acceptable when it is embedded under juede. For example, in a scenario where everyone is assigned by Lisi to buy something, a person wondering about the purchase that Lisi has assigned to Zhangsan could ask, as shown in (46).

A similar amelioration effect can be found with only-focus, as compared with (38), as shown in (47).

Phenomena similar to those in (46) and (47) have been reported in other languages. In Japanese and Korean, for instance, the intervention effects found in wh-questions containing intervening quantifiers may be canceled or weakened in embedded declarative clauses, as in (48).Footnote 18

From the current analysis, it follows that the clause-initial quantificational operator, for example, yinggai in (46) and daremo-ga ‘everyone’ in (48b), does not intervene in the valuation of wh-phrases, because the valuations of wh-features and the quantificational operator are not in the same phase. That is, wh-features occur in matrix CP, whereas the scope elements are in embedded CP (cf. Uriagereka Reference Uriagereka, Epstein and Hornstein1999; Chomsky Reference Chomsky, Martin, Michaels and Uriagereka2000).Footnote 19 However, intervention effects do occur when the valuations of both types of quantificational elements (e.g. quantifier/focus and wh-phrases) appear in the same phase, e.g. in the same matrix clause or in the same embedded interrogative CP.

The above observations indicate that the phenomenon under discussion cannot be subsumed under optional subject-raising; i.e. Chinese modals cannot be raising verbs. However, the structural restrictions of modals and their associated phenomena can be accounted for if one accepts the present analysis that sentence-initial modals are in CP, focus-marking a TP, and that canonical modals are in TP. The contrasts presented in this section support the present paper’s assumptions 1) about the associations of focus with c-command and 2) that, in Chinese, the valuation of focus features between specifier and head is covert.

Additional new observations are presented in Section 6, as a means of elaborating on the types of focus that sentence-initial modals can express. The major types, i.e. propositional focus and subject focus, comply with the c-command requirement of focus association.

6. Focus types expressed by sentence-initial modals

6.1 Propositional focus, assertive polarity, and verum focus

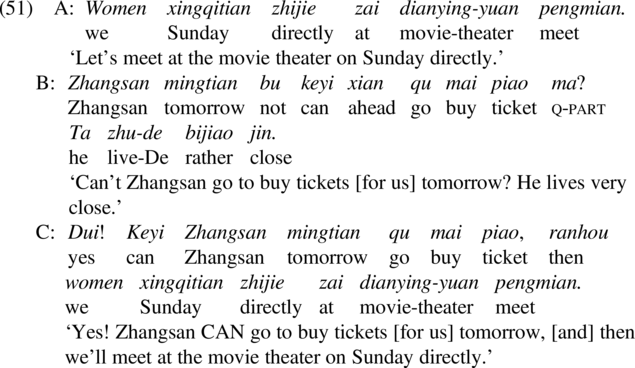

In addition to propositional focus discussed in the previous sections, sentence-initial modals in Chinese can express two other types of proposition-related focus: assertive polarity and verum focus. Their differences can be illustrated by considering the discourse in (49) and (50). The example (49) presents the propositional focus that has been discussed – focalizing a proposition that is not yet at issue – where keyi ‘may’ in speaker B’s response demonstrates the assertion of the proposition that Zhangsan can buy tickets [for us] tomorrow. After (49), speaker A could update the common ground by uttering a sentence like (50), to confirm that speaker B’s proposal is feasible and to then bring up a new idea. In such a case, the polarity of the proposition in (50) is emphasized (cf. Holmberg Reference Holmberg2015).Footnote 20 It should also be noted that the utterance in (50) follows the previous conversation in (49); and, because of (49), the propositional focus can become part of the background after updating the common ground – the assertive polarity being introduced; thus its following TP in (50) can be omitted.

‘It is OK that Zhangsan goes to buy tickets [for us] tomorrow, [and] then we meet at the movie theater on Sunday directly.’

Syntactically, examples like (50) illustrate two more important points. First, the focus unit of the same span can form a focus complex (a point addressed further in Section 6.2). That is, the polarity of the proposition expressed by the modal in (50) has been further emphasized by the emphatic marker shi. Second, the facts of the ellipsis support the functional-head analysis (Lobeck Reference Lobeck1995) of sentence-initial modals. In (50), the clause following the modal keyi (i.e. Zhangsan mingtian qu mai piao) can be omitted. Similarly, following the conversation in (49), if no other concerns need to be addressed, one may confirm B’s proposal simply by saying Keyi! ‘Can!’. These examples of clause ellipsis suggest that a functional head – i.e. focus, as proposed in the present study – may be involved.

Another type of proposition-related focus that has been widely discussed in the literature is verum focus, which in English and German typically relies on a stressed element in the left periphery of a sentence (associated with C) to emphasize the truth value of the prejacent (Höhle Reference Höhle and Jacobs1992; Lohnstein Reference Lohnstein, Féry and Ishihara2016).Footnote 21 Verum focus is also possible in Chinese, but is expressed by a linguistic device different from those in German and English, i.e. sentence-initial modals. In the discourse in (51), after speaker B proposes a plan (51B), speaker C considers the prejacent (51B) and uses (51C) to assert a belief in both the superiority and the feasibility of a different plan.

Example (51) indicates that Chinese sentence-initial modals can mark propositions that are at issue, like stressed English modals can (cf. Hole Reference Hole, Krifka and Musan2012). Structurally, these focus readings of sentence-initial modals can be accounted for if such modals are merged in CP for marking focus.

6.2 Subject focus

Although it is not the main concern of the current study, based on the well-established structural generalization – focus c-commanding association (e.g. Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1972; Tancredi Reference Tancredi1990; Aoun & Li Reference Aoun and Li1993; Bayer Reference Bayer1996) – the current analysis of sentence-initial modals can be extended to account for scenarios involving subject focus. Before the facts are presented, it is worth noting that due to the c-commanding association requirement, Chinese focus markers only associate with their immediately c-commanding constituents; thus, a sentence-initial focus marker can express a propositional focus or a subject focus but not an object focus.

The current proposal relies on the following assumptions: first, that differing spans of focus units in a sentence incur intervention effects during their focus-operator association (see Section 5), and second, that different types of focus of the same span can form a focus complex licensed by the same functional head, as a result of continuously updating of the common ground in conversations: a process exemplified by the compatibility of emphatic shi and sentence-initial keyi, shown in Section 6.1. It is important to note, however, that the proposed view of such focus complexes is not a Chinese-specific phenomenon and is not restricted to situations related either to verum focus or to focus marked at the sentence-initial domain. Similar examples can be found in English. For instance, the English cleft focus in Paris in (52a) can be modified by a focus particle, such as only, as in (52b) (see Hole Reference Hole2011). Examples (52c) and (52d) are their equivalents in Chinese.

The following mini-discourse examples demonstrate that sentence-initial modals can be compatible with the major types of subject focus, given appropriate discourse contexts.Footnote 22 The crucial point is that the focus span of the sentence-initial modals is on the subject only. Examples of this include the wh-subject in (53), the only-subject in (53D), (53E), the cleft-subject in (54B), and the even-subject in (54D).

In each of these scenarios, the focus features are valued by the relevant heads in CP and form a focus complex. Provided that there are appropriate updates to the common ground of conversations, it is assumed that these complex focus units are formed compositionally in semantics.

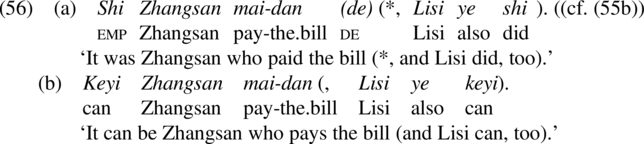

Last but not least, while cleft-subject is exhaustive (cf. Szabolcsi Reference Szabolcsi1981), the subject focus marked by the sentence-initial modal is not. A common paradigm utilized to show exhaustivity is based on the logical consequences that flow from whether the focus unit at issue is compatible with additional members being added to the focalized domain, for example (55).

The same type of exhaustive reading has also been reported for Chinese cleft construction, e.g. (56a) (Tsai Reference Tsai1994; Hole Reference Hole2011), whereas examples containing a sentence-initial modal, such as (56b), do not exhibit the same restriction. The difference shown in (56) provides further confirmation of the current study’s contention that sentence-initial modals are associated with unique focus features that differ both from only and from cleft foci.

7. Conclusion and residual issues

This study of the interpretations and structural characteristics of Chinese epistemic and deontic modals in the sentence-initial position has argued that sentences with sentence-initial and sentence-internal modals should not be treated as involving free-word-order alternations, whether resulting from an optional topicalization or from an optional subject-raising (e.g. Lin & Tang Reference Lin and Tang1995; Tsai Reference Tsai2010, Reference Tsai and Shlonsky2015; Lin Reference Lin2011, Reference Lin2012; Chou Reference Chou2013). The new evidence it has presented indicates that previous analyses of these matters have yielded incorrect predictions and cannot provide consistent explanations of the facts concerning the syntax and information-packaging expressed by modals in different positions.

7.1 Residual issues

One remaining question relates to the fact that, among the three major semantic types of modals, only epistemic and deontic ones may occur before a subject, while dynamic modals related to personal willingness, volition, and ability – like ken ‘be willing to’ and gan ‘dare’ – cannot. In (57), for instance, the modal keyi ‘can’ in the sentence-internal position can express either a deontic reading or a dynamic one. However, when this modal occurs before the subject, for example (58), only the deontic reading survives.

This contrast requires some further consideration of structural implementation. It is possible that dynamic modals initially merge in a lower position as the control verb, as proposed by Lin & Tang (Reference Lin and Tang1995), or inside vP, as proposed by Tsai (Reference Tsai and Shlonsky2015); and if so, it is not possible to raise to T and then to C. However, there are some challenges to both these accounts. Applying a control-verb analysis to dynamic modals requires accepting that this special type of control verb, unlike typical control verbs, does not assign a consistent theta role (e.g. the ‘adjunct’ theta role in Roberts Reference Roberts1985) and that this is inconsistent with the general theta criterion (Chomsky Reference Chomsky1981).

Semantically, it is well known that dynamic modals do not express modal interpretations at the level of propositions while epistemic and deontic modals do (Palmer Reference Palmer2001). Aspectual categories are generally assumed to be functional categories in the split-TP domain (Huang et al. Reference Huang, Li and Li2009; cf. Pollock Reference Pollock1989), but in Chinese, most are expressed as verb suffixes, ‘as a result of affix hopping in Phonetic Form’ (Huang et al. Reference Huang, Li and Li2009: 104). Only progressive aspect zai- and imperfective aspect mei(you) occur preverbally. Unlike other types of modals, dynamic ones usually are not compatible with aspect markers (similar to German, see Wurmbrand Reference Wurmbrand1999). Nonetheless, the examples in (59) show that occasionally, mei(you) occurs in a dynamic modalized sentence, provided that the dynamic modal follows the imperfective.

Examples like (59) suggest that dynamic modals are lower than aspect phrases. Therefore, the reason for dynamic modals’ inability to raise to C may be related to aspect-verb association, in which the aspect head blocks the potential head-movement of dynamic modals. However, comprehensive and holistic investigation of that issue must await future research.

7.2 Final remarks

This paper’s findings have three main theoretical implications. The first is that changes in word order in Chinese are not ascribable to an optional or free derivation in syntax but rather are required by syntactic computations to express specific information packaging, as evidenced by the interaction between sentence-initial modals and other focus elements. The second is that Chinese’s features related to information structure are active in narrow syntax (cf. Rizzi Reference Rizzi and Haegeman1997; Cinque Reference Cinque1999; Miyagawa Reference Miyagawa2010); and the third is that Mandarin Chinese, although profoundly different from Germanic and Romance languages typologically, includes both the split-CP à la Rizzi (Reference Rizzi and Haegeman1997) and split-Infl à la Pollock (Reference Pollock1989), presenting a neat mechanism of interaction between syntax and information structure (cf. Lechner Reference Lechner and Frascarelli2006; Szabolcsi Reference Szabolcsi2011).