In summer 2016 during field research, my interviewee who had worked in the Accra Metropolitan Assembly (AMA) as a senior official remarked about the positive impact of a disaster that would provide the opportunity to reconstruct Accra's seaside communities of Ussher Town and James Town.Footnote 1 The communities are located near one of the city's prime areas. The interview revealed that some officials in the AMA secretly hoped that fire would raze the neighborhoods and the destruction would shock and distract the communities from mobilizing against longstanding official redevelopment plans.Footnote 2 A disaster would cut the cost of a largescale demolition scheme fated to provoke widespread grassroots opposition. Politics of disaster derives its basic idea from the view that a catastrophic event reduces the likelihood of popular hostility to an urban renewal project proposed by powerful interest groups seeking to reconfigure a city's physical and social fabric.Footnote 3 The secret aspiration in the AMA is not new. It is profoundly similar to Gold Coast Governor Arnold Hodson's reconstruction plan 77 years earlier: when an earthquake struck Accra in 1939, the British colonial regime saw a chance to rebuild a city which, in the mind of these officials, would be a worthy capital for the Gold Coast. However, the botched reconstruction plan exposed the weakness of the British colonial state and spread discontent, priming Accra for anticolonial nationalism.

Scholarly work has treated disaster, like fire, earthquake, disease epidemic, and flooding, as an integral part of humanity's history. Disaster has left its mark on Accra's history. Ato Quayson has shown that recurring disasters in Accra propelled official efforts to remodel Ussher Town and James Town in accordance with colonial urban visions.Footnote 4 Focusing on the June 1939 Accra earthquake, D. J. Blundell also sees an opportunity in the catastrophe to enhance Accra's disaster preparedness and infrastructure.Footnote 5 Similarly, historians who have studied disaster outside Accra have demonstrated the ways in which these events challenged politicians and experts to collaboratively develop modern methods of disaster mitigation and preparedness, including building codes, regulatory bodies, and emergency response strategies.Footnote 6 However the responses of society's powerful, including elected officials and corporate leaders, to disaster impacted ordinary people unequally. They used disaster as an excuse to carry out and justify unsound policies and practices that had violent and detrimental impacts on underserved people, minority communities, and the environment.Footnote 7 Naomi Klein argues that disaster capitalism occurs when private interests displace those of affected communities in the wake of catastrophe in the neoliberal era.Footnote 8 At the same time and in ways largely unexplored, however, disaster provides a moment of clarity for ordinary people to see the limits of power. Less powerful people have leveraged disaster because of its loud, dramatic, and attention-grabbing nature. Angry city residents torched hotels, cinemas, nightclubs, commercial shops, and other physical manifestations of imperialism and privilege to make a statement and effect change.Footnote 9 Examining the June 1939 earthquake, just before the outbreak of war in Europe, the article argues that during a moment of growing nationalism in Africa, disaster, its aftermath, and the responses of urban residents generated widespread discontent in Accra.

As the capital city, Accra became the symbolic center for anticolonialism in the nation, a movement which culminated in 1957 with the Gold Coast becoming the first colonial state in sub-Saharan Africa to attain political independence. Research has shown that the city was a key scene where Gold Coast nationalism emerged.Footnote 10 Dennis Austin, Adu Boahen, and David Apter have traced the beginnings of anticolonial nationalism to popular discontent, manifesting in events ranging from cocoa hold-ups when chiefs, farmers, and traders coalesced in protest against the pricing policies of European export firms in the 1930s to an outburst of rioting in Accra in 1948, when the police shot into a group of unarmed military veterans and killed two of them.Footnote 11 The veterans were on the way to the governor to seek redress to their economic hardships. As Jeffrey Ahlman notes, it was the volatile economic and political situation that propelled Kwame Nkrumah to serve as the general secretary of the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC) and form the Convention People's Party (CPP).Footnote 12 Jean Allman summarizes this crucial moment, which coincided with the earthquake and post-disaster reconstruction, as one marked by growing consciousness of socioeconomic and political deprivations, setting the stage for national mobilizations, decolonization, and the emergence of new African states.Footnote 13 Recent scholarship by Allman, Jennifer Hart, and Carina Ray about ethnicity and class, auto/mobility, and interracial sex reflects granular complexities and contradictions in the growing tension and widespread anticolonial nationalism.Footnote 14

However, the historiography on anticolonial nationalism does not account for the earthquake and its aftermath, despite the fact that it laid bare the weakness of colonial power and intensified urban resentment against colonial rule. As will be seen, the earthquake afforded Governor Hodson, the most powerful 'man on the spot’, the opportunity to attempt reconstruction of the city along lines that, in his assessment, would position Accra to better serve its functions as the colonial capital, an entrepôt port city, and a commercial hub. His attempts were not successful. But they instigated anticolonial sentiments and prepared residents to join the ranks of the educated elite and nationalists. In tracing the earthquake and the events linked to it chronologically and in detail, the article builds on Naaborkor Sackeyfio-Lenoch's and John Parker's books on the roles of Africans in making Accra.Footnote 15 It shows that the process of urban redevelopment helped to mobilize Accra residents in support of nationalism while creating divisions among them, with repercussions for the years leading up to independence and beyond.

How Accra's residents responded to the earthquake and official reconstruction plans is evident in scores of documents. Based in the Gold Coast and Britain, newspapers updated the public about official disaster relief plans and the responses of affected residents. The governor and his officials routinely invited the press not only to cover disaster relief meetings and pass on the information to the public, but also to gather information about the popular mood. Information to and from officials was read aloud and translated to Accra's overwhelmingly nonliterate majority of fishermen, petty traders, laborers, servants, shoemakers, bricklayers, and blacksmiths.Footnote 16 An influential newspaper, The Gold Coast Independent, for example, covered quite a lot of the events linked to the disaster. The news was, of course, mediated through Accra's African reading public, including schoolteachers, lawyers, clerks, medical doctors, and journalists, who were fluent in English and the local Ga language. The urban crowd consumed newspaper articles, short commentaries, and editorials, some of which recorded the misgivings of residents. African journalists and Accra's residents who published in the newspapers were critical in shaping the opinions and actions of the public and officials. The official renewal plans, letters, reports, and petitions circulating within the colonial bureaucracy in Accra and between the governor and the secretary of state for the colonies in London also provide proof of individual and group protests against residents’ land being used for reconstruction and rehousing.Footnote 17 Ga residents of Accra held the colonial state responsible for losing swaths of agricultural land and produce, arousing widespread discontent, especially amongst those who had worked these lands for generations. The hardships resulting from the destruction of their farms were exacerbated because of the inflation and scarcity of essential commodities on account of the Second World War.Footnote 18 Official correspondence further reveals consternation in the Ga communities about the colonial rehousing project. The Ga thought state housing would cost the community their control of Accra as their ancestral home.Footnote 19

People and places in Accra

Accra extends from the coastline of the Gulf of Guinea to the Akwapim hills. It is historically and currently the capital city of modern Ghana in West Africa. The city is marked by rivers, lagoons, and open surf beaches. Accra was home to the Ga centuries before British colonizers established it as the capital of the Gold Coast. The Ga entered the transatlantic economy, which embraced Europe and the Americas, as traders, using their ‘middleman’ position on the trade in enslaved people, oil palm, cocoa, ivory, guns and gunflints, liquor, textiles, and gold between African traders in the interior and Europeans on the coast. Serving the Atlantic economy as an entrepôt port since the seventeenth century, Accra and its diverse Ga-speaking intermediaries attracted a cosmopolitan population from within and outside Africa. As a city that served multiple functions, including shipping, commerce, and security, Accra provided multiple opportunities that in turn attracted migrants who the Ga regarded as strangers, some of whom incorporated into the community. Traders from the interior arrived in Accra daily to buy fish, which was the primary industry, and salt. In the first population census of Accra in 1891, officials recorded one out of four adult males in Accra as fishermen. The fishing industry was characterized by a division of labor with profound implications on gender relations, urban economy, and domesticity. While men did the fishing, women preserved, marketed, and traded the fish.Footnote 20

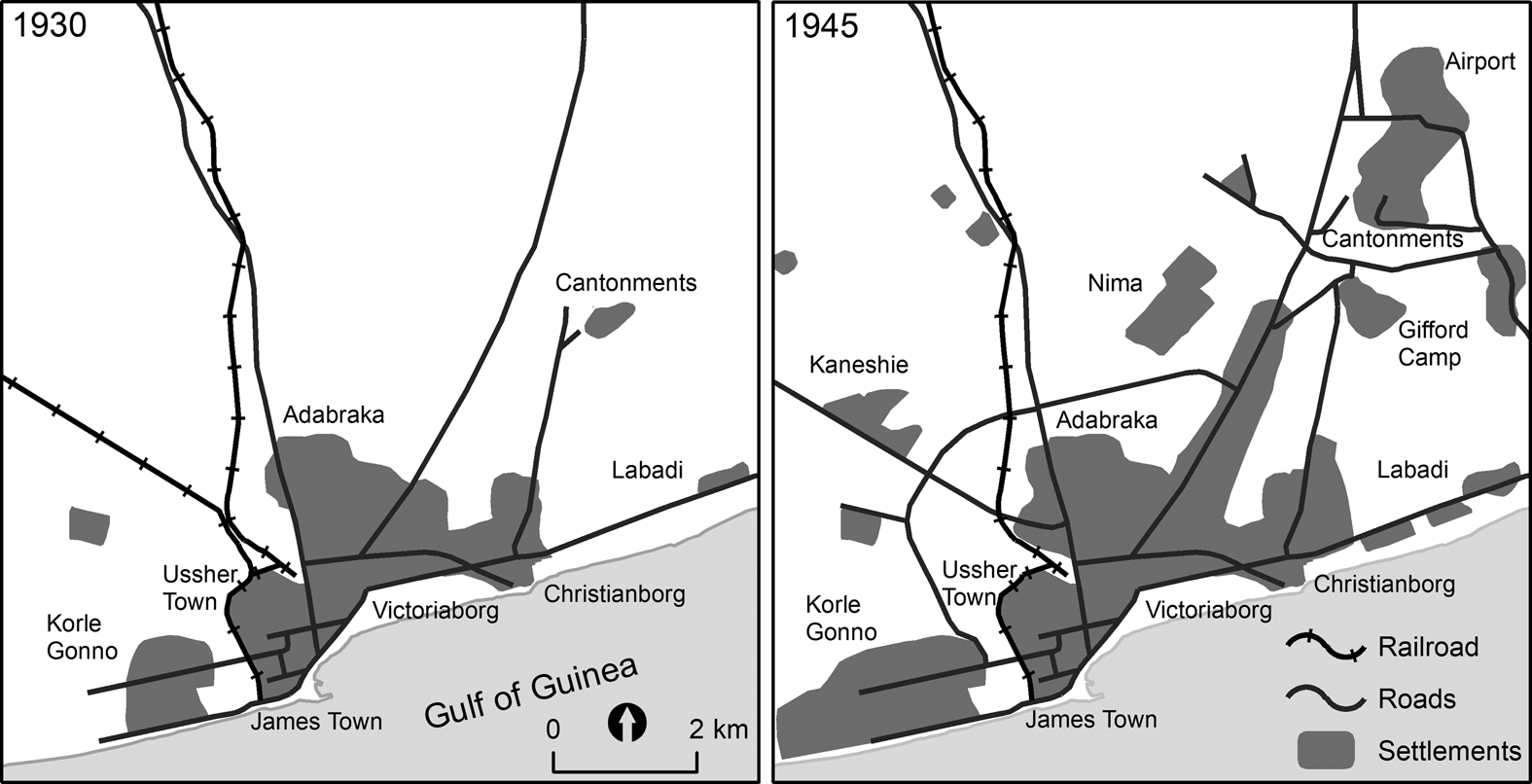

In 1877 Accra became the capital city, three years after British imperial planners and colonial officials declared the Gold Coast Colony. It covered Ussher Town, James Town, Victoriaborg (European segregated area), and Osu (Christiansborg), all of which were within three miles reach of one another. According to the 1891 census count, 19,999 residents lived in the municipal area.Footnote 21 It remained the capital of the colony through formal independence. Although nationalist leaders renamed the colony as Ghana after colonial rule ended, they maintained Accra as the capital city. In the time between becoming the capital and seat of government through the present, Accra took on crucial additional functions related to administration of government, security services, and the economy. As a result, expatriate communities of British, Germans, Italians, and Americans, among others, increased over time.Footnote 22 The demographic growth, along with the construction and arrangement of its physical features, including telegraphic, postal, and communication facilities, roads, commercial premises, railway termini, port facilities, and residential areas were influenced by cocoa exports in the first decades of the twentieth century.Footnote 23 The physical infrastructure catered to the needs of the growing cosmopolitan population. As shown in Fig. 1, the city grew considerably. The population increased from 61,588 in 1931 to 135,926 in 1948.Footnote 24 The 1939 June earthquake was the most disastrous occurrence to strike Accra since its founding as the colonial capital city. Accra residents had never seen physical development activity or administrative intervention in their lives at such high levels as they did in the earthquake's aftermath. To them the disaster was both a promise and disappointment.Footnote 25

Figure 1. Accra Population and Residential Expansion between 1930 and 1945

From ‘The Growth of Accra’ map series in the 1958 Master Plan, the maps above geo-reference the current roads and recreated the 1930 and 1945 settlements, roads, and railroads so they align with the plan and with each other. James Town and Ussher Town are to the west of Victoriaborg and east of Korle Gonno. The rehousing schemes were in different parts of the city, including Korle Gonno, Christiansborg, Labadi, and Kaneshi.

Source: Map created by Ryan Kirk.

The June 1939 earthquake

The earthquake shook Accra in the evening of Thursday 22 June 1939. Tragically, the African communities in Ussher Town and James Town were hard hit. The communities were densely populated in stone buildings as well as mud and thatch houses. As a result of that first shock, some houses collapsed while others cracked and became too dangerous for habitation. Many of these structures collapsed over subsequent days, following persistent aftershocks and heavy rainfalls.Footnote 26 Thousands of people were displaced.Footnote 27 Two days after the major tremor, officials recorded 149 casualties, including 16 deaths, all of whom were Africans.Footnote 28 The Red Cross Society and colonial agents provided relief, including blankets, food, medical aid, and makeshift shelter.Footnote 29 For a moment, the colonial administration contemplated the possibility of relocating the capital of the colony from Accra, in view of the extent of the damage and because of a geological observation that Accra was a ‘major danger spot’ and liable to future quakes.Footnote 30 But colonial officials reconsidered the relocation plan when they saw an opportunity in the disaster — much like neoliberal era disaster capitalism — to remake the Ga urban core, implementing a plan that had been on the drawing board since Accra became the capital city in the nineteenth century.Footnote 31

The initial tremor shook the coastline city at 7:23pm and lasted approximately a minute. But to the residents who lived through that terrifying experience, it was hard to give the exact duration. The sound, sight, and feel of the quake were frightening, as was the ensuing reaction of residents. The assistant colonial secretary, Harold Cooper, noted that the quake was not a subdued rumble that increased in sound ‘as the uneasy minute passed, but a sudden deafening clamour which pursued a monotonous and nerve-wracking course until it ceased as abruptly as it had begun’.Footnote 32 It was followed by a total blackout and a ‘shrill and eerie wail’ from the African neighborhoods.Footnote 33 The moon appeared ‘sickly green’ and ‘a great dust cloud hung like a pall over the region for hours’.Footnote 34 Negley Farson III, a special correspondent of the Daily Mail and author of The Way of a Transgressor, who was hospitalized at Korle Bu Hospital when the coastline trembled, described his bed bucking and the ‘air filled with a continuous noise like the roaring of an underground train’.Footnote 35

The aftershocks struck terror in the hearts of residents. Africans and non-Africans slept outside their homes for fear that the recurring minor shocks would bring down their houses and bury them alive.Footnote 36 Torrential rainfalls made matters worse as residents, state officials, and other agencies battled not only diseases, hunger, and homelessness, but flooding as well. According to Farson, churches were filled up while prayers and sermons took longer than usual, and after services, residents went out to ‘fire antique muzzle-loaders into the air to ward off evil spirits’.Footnote 37 As one African depicted the violence of the earthquake and torrential rainfall in vernacular English, ‘Almighty vexed plenty. First he make palaver for underneath; now he make palaver for top’.Footnote 38 God was extremely angry and a show of the anger was the serious trouble from the ground below and sky above. All this description about church, evil spirits, and God reveals not only Ga cosmology of a distant supreme being and super natural forces manipulating the worlds of the living, the dead, and unborn, but also a plural landscape of healing traditions routinely deployed in moments of adversity to restore a balance between the physical and metaphysical realms.Footnote 39 As elsewhere in the world, the Ga too saw the hands of supernatural forces at work in the quake and rainfall.Footnote 40

While the Ga could explain the earthquake from the perspective of their belief system, they were stunned by the official response to the disaster. When the hardest-hit communities were struggling with displacement, destruction, and deaths, officials were delighted the ‘disaster had one happy effect’: ‘the unhealthy congestion which existed in the center of Accra had now disappeared’.Footnote 41 It appeared the right time to relocate recalcitrant residents, complete the destruction, and turn the center of Accra into a tabula rasa ready for construction projects. Governor Hodson revealed the plan to the secretary of state for the colonies in London:

My policy is, therefore, directed towards securing at the same time not only the reparation of the earthquake damage and the rehousing involved therein but also the clearance and re-planning of those congested areas which would have had to be dealt with by slum clearance schemes in the near future…. It may be mentioned that in preparation for the introduction of slum clearance schemes in Accra, a matter which has long been in the mind of Government, several layouts had already been set out on the outskirts of the town.Footnote 42

In the minds of colonial officials, the close-knit urban settlement patterns of the Ga communities looked like ‘slums’. The demolition would clear the way for wider streets, and up-to-date commercial and residential buildings, all of which would enhance the commercial, port, security, and administrative status of Accra.Footnote 43 If initially Accra residents seemed too despairing and distracted to oppose a demolition scheme, these moves soon provoked defiance.

Chaos and defiance on the coast

The earthquake intensified the struggle for Accra, especially around Ussher Town and James Town. Since becoming the capital of the colony, the urban experience was marked by struggles among the Ga communities — and between the Ga and non-Ga, including the colonial administration and European commercial interest groups — to control the levers of power, transaction, and exchange.Footnote 44 In addition to the colonial state, which for decades had been bent on reconstructing the seaside neighborhoods of Ussher Town and James Town into modern-looking thoroughfares, business premises, and residential areas, other conflicting interest groups added complexity to the struggles to remake and preserve the urban fabric. Religious authorities, public health and urban planning experts, African business entrepreneurs, Western-educated elites, and immigrant communities envisioned the city differently, especially with regards to how much of the African indigenous religious landscape, precolonial urban forms and architecture, and indigenous sources of livelihood should remain in the center of a British colonial capital.Footnote 45 The seaside neighborhoods and its environs were fiercely contested as the core of Ga precolonial urbanism located in a prime site near the port, a European segregated residential area, and the colonial administrative center.Footnote 46

At the heart of the contest were debates over the changing meanings of land and land tenure. The experiences of past major disasters, like a fire in Ussher Town in 1894 and a plague outbreak in the city in 1908, precipitated far-reaching physical developments, including the widening of Accra's main commercial thoroughfare (Otu Street) and the construction of the new suburban areas of Korle Gonno, Adabraka, and Korle Woko (Risponsville). Ga landowners were aware that urban and suburban land held significant political and economic value.Footnote 47 Living under a colonial dispensation in which officials enacted new land laws and placed monetary value on land purchased from families and chiefs, Ga-speaking people reinterpreted landed property in ways that brought about disputes.Footnote 48 Legal battles in the supreme court over land — which were meant for roads, public buildings, private residences, warehouses, and other physical constructions, acquired by officials and wealthy individuals — came under public scrutiny and the compensation received by African litigants from suits were open affairs known to the urban crowd.Footnote 49 In this atmosphere, discussions about land and landed property in the area energized the public. Thus, despite colonial reconstruction plans threatening Ga communities, these proposals provided colonial officials with allies amongst local landholders, who were understandably enticed by the prospect of owning property in a newly upscale commercial, recreational, and residential urban core.

The official plan to take advantage of the earthquake to ‘sanitize’ Accra proved to be long drawn out, further dividing Ga-speaking people. A few days after the disaster, representatives of the fishing communities who lived and worked in and around Accra learned about the official plan to reconstruct the city. Following tradition, the fishing communities convened a mass meeting in the morning of July 12 to consider the plan, especially the part that envisioned a new fishing village at Chorkor, to the west of Korle Lagoon. The fisherfolk were deadlocked, and the proposed reconstruction scheme became enmeshed in ongoing intergenerational tension.Footnote 50 Led by one Otoo, a faction constituted by young generation declared that they ‘did not like the site suggested by the District Commissioner as the sea at Chorkor [was] very rough, and it [was] difficult for one to carry on fishing business there’.Footnote 51 The roughness of the sea at Chorkor increased the likelihood of drowning, posing risks to both fisherfolk and the fishing industry as a whole.Footnote 52 The older, established fisherfolk ultimately dismissed the meeting, commanding that the young must ‘leave all matters entirely in the hands of the elders’ to make the final decision.Footnote 53

The Ga mantse (paramount chief) took to the airwaves and attempted to dissuade the young fisherfolk from doing anything that would disrupt the official vision of remaking the city. It was evident that the broadcast was the outcome of multiple meetings with elder fisherfolks, the mantsemei (chiefs), and colonial officials. The mantse declared support for the proposed relocation and rebuilding plan and urged the young fisherfolk to cease any further opposition to the elders, the mantsemei, and the colonial administration: ‘Those of my listeners who are associated with the inhabitants in some of these congested areas will readily agree with me that the proposed rebuilding of these areas is not only a measure towards bringing the inhabitants to present day living but an utmost desideratum’.Footnote 54

That echoed Hodson's idea to demolish the ‘slum’ neighborhoods in Accra, a plan expressed in the governor's correspondence with the secretary of state two weeks earlier. Declaring support for the colonial state, the mantse and his council of elders confirmed the official belief that ‘in every large centre [principally Accra] in the Gold Coast the local Authorities’ were ‘keenly alive to the urgent necessity for the removal of their congested slum areas’, suggesting a tension between traditional officeholders and ordinary people over urban renewal.Footnote 55 The earthquake and the post-disaster reconstruction plans brought the tension to the fore, further estranging the young fisherfolk from the mantse and his council of elders. The implications of a strained relationship between ordinary people and their mantsemei had dire consequences for indirect rule and reveals another catalyst for growing popular support for anticolonial nationalism.Footnote 56

On the surface, it looked like the Ga mantse and the elders selflessly supported Accra's renewal plans, but that was not the case. About two months after the earthquake, an editorial in one of the Gold Coast's most read newspapers, The Gold Coast Independent, revealed ongoing land sale negotiations involving the elders and residents relocating from the earthquake zone.Footnote 57 When colonial officials got wind of the legitimate negotiations, they stepped in, stopped the deals, and proposed their own land acquisition terms.Footnote 58 To the elders, having landed property near an upscale and commercial district near High Street, warehouses, banks, firms, and other expensive property meant a greater chance of accumulating wealth for themselves and posterity. But to the young fisherfolk and ordinary Ga residents, the editorial reeked of past land disputes and illicit land sale by elders traditionally entrusted with land custodianship. It also evoked memories of official overreach of forcibly relocating Africans and purchasing their land in the name of public use and public health. The nonliterate majority going about their daily lives, of course, had no access to colonial urban blueprints. But they saw the intensifying infrastructure development taking place around them, the swelling migrant population, and the frequent land disputes, some of which were tied to (illicit) land sales. Indeed, the legal battles in the supreme court over land and landed property came under public scrutiny.Footnote 59 Rumors of any behind-the-scenes land deals were bound to inflame passions, cause chaos, and stifle well-intentioned urban (re)construction projects.

The media, run by a section of Accra's Western-educated Africans, initially expressed excitement at the prospect of remaking Accra into a new city from the ‘ashes of old Accra’, but became dissatisfied later with how officials mishandled the reconstruction.Footnote 60 Initially attempting to dissuade the defiant young fisherfolk and some of the uncooperative members of the Ga communities, The Independent stated that residents should acquiesce to the official plans in the interest of ‘progress and the will to build an Accra to be proud of’.Footnote 61 The newspaper would later berate the colonial state for poorly handling the post-earthquake reconstruction. In addition to competing with the elders for land, officials sanctioned the unrestrained demolition of houses that were not seriously affected by the shocks without providing alternative housing for victims. Contributors to the newspaper and the editors joined the calls by the African representatives in the Accra Town Council to immediately halt the demolition.Footnote 62 By acting with speed and taking advantage of the misery and distraction to secure the area, the colonial state was ‘making good use of the opportunity afforded by the earthquake to make a clean sweep’ for its self-serving renewal and repurposing plan.Footnote 63 Officials increased the house bulldozing when they failed to get the communities to accept their financial and other incentives.Footnote 64 That desperate move incurred widespread displeasure among the educated elites who had been the closest allies of the colonial state months earlier. While some of the educated elites had families and friends in the communities, others were directly affected by the earthquake, rampant demolition, and displacement.Footnote 65

Rather than discourage rebuilding at the earthquake-hit zone, the uncontrolled demolition spread defiance in Accra. In 1940, the European president of the Accra Town Council expressed a frustration felt by colonial officials when he remarked ‘it was the practice that when a shack was demolished on a certain spot at the request of the council, it was erected on another site only a few yards away’.Footnote 66 Months earlier, the secretary of state had made a similar remark after learning that African landlords and households were reconstructing their houses in Accra where the colonial state was planning to appropriate and repurpose: ‘I know that before the war it was your desire to turn the disaster of the earthquake to a good by the rebuilding of the town in a manner worthy of the capital of one of the larger British Colonies’.Footnote 67

The self-help rebuilding activity in the center of Accra prompted the secretary of state to follow up on the earlier correspondence with Governor Hodson about the plan to reconstruct the area as a residential and commercial zone that would have a network of wide streets to bolster the commercial, port, security, and administrative functions of Accra. A further blow to the governor's plan occurred in 1942 when two-thirds of the Ga who had accepted new housing on the outskirts of Accra moved back to their original quake-destroyed neighborhoods. The exodus occurred after officials announced they would begin charging rent for the new accommodations.Footnote 68 Ga households and the fisherfolk were not used to paying rents in Accra which they rightfully treated as their ancestral home.Footnote 69

Meanwhile, the European president of the Accra Town Council was compelled to respond to an editorial in a local newspaper that called him out for contributing to widespread discontent by being insensitive to residents still counting their losses. Strongly worded, the editorial condemned the council for going after rate defaulters by putting up their houses for sale despite the catastrophe and rising cost of building materials and consumer goods.Footnote 70 It appeared the council was ‘looking out for such conditions’ to take ‘its pound of flesh’.Footnote 71 By sowing the idea of a vengeful colonial-controlled council, the paper potentially derailed any effort to inspire loyalty in support of the raging world war. The editorial prompted the president to try to mollify public anger, including by explaining the council's lenient rate collection policy. The governor might have been satisfied with the explanation that the council had enacted a relief program for the ratepaying public who had financial difficulties because of the disaster.Footnote 72 But public opinion had already been swayed by the accusation of the council showing insensitivity, indifference, and callousness by collecting ‘bad money’ from a community which was paying through ‘the nose for things it needs, at 100 percentum more but from the same earnings’.Footnote 73

The failure to readily reconstruct Accra compelled the governor to seek outside expertise. In 1943, the Colonial Office assigned Major E. Fry Maxwell the task of advising Accra officials about what do to with the supposed ‘slums at their worst’ of Ussher Town and James Town.Footnote 74 The young fisherfolk made good on their promise not to relocate.Footnote 75 The unrestrained demolition activity in the months following the earthquake exacerbated housing shortages and fueled anger.Footnote 76 Officials attributed their failure to reconstruct Accra to a lack of statutory power to enforce compliance. Colonial (re)planning had followed a practice of acquiring land and making layouts based on the advice of a handful of officials in the departments of health, public works, survey, and lands. The ad hoc planning and development practices that happened after the earthquake caused legal and practical difficulties which, in the opinion of officials, were ‘the most radical and likely to cause embarrassment’.Footnote 77 The colonial state's inability to realize its vision for Accra dealt a blow on the power which it projected. It was in this context that the Town and Country Planning Ordinance of 1945 came into effect to not only help to enforce Fry's proposal to (re)plan Accra but control the reputational damage to colonial power.Footnote 78

The official perspective of the post-earthquake reconstruction debacle discounts vital contributing factors. While the colonial state and colonial laws complicated land tenure and meanings of landed property, and aroused suspicion among ordinary residents concerning official urban (re)planning, no governor wanted to court the disloyalty of colonial subjects and foment political instability during the Second World War. The stakes were high for the young fisherfolk whose lives and livelihoods depended on living and working near the center of Accra. Numerous Ga households also regarded the core of Accra as their home where their ancestors rested.Footnote 79 Deeply attached to the land, the Ga-speaking people were not going to acquiesce to a plan involving relocating the community and disrupting their belief system. There was also a broader implication in demolishing and repurposing an area that was traditionally the heart of Ga power: as implied by the secretary of state in the correspondence with Governor Hodson less than a year after the disaster, the demolition and reconstruction of Accra, as envisioned by the colonial state, would project the dominance of British imperialism over Ga traditional authority.Footnote 80 It would bring decades of colonial struggle for complete control of the capital city to a high-water mark. The opposite was also true for the Ga who held Accra as the center of their political, economic, and ritual power. The quest for control partly explains why Ga elders, seeking to maintain their traditional right of ownership of the political and sacral core of their homeland, moved to negotiate for and own the land before colonial officials could put their own land acquisition effort into motion.Footnote 81 The factors all complicated the calculus for British officials of whether it was worth risking disloyal subjects and a chaotic capital during wartime to pursue an unpopular urban renewal effort.

Rehousing

An immediate and unprecedented state-sponsored housing estate scheme was one of the most notable ways the earthquake spurred the rapid transformation of Accra in the 1940s. Never had the colonial state intervened in the lives of ordinary people through public housing as it did after the quake.Footnote 82 However, acquiring land for the construction of the estates was fraught with misunderstanding between African landowners and colonial agents who negotiated on behalf of the state. While some African landowners imposed limitations on the state regarding who and for how long the houses were to be sold and rented, others refused to negotiate with the agents based on their well-founded suspicion that the state was putting up the houses not for the exclusive purpose of providing a relief for people hit hardest by the earthquake.Footnote 83 Although these setbacks forced the state to rethink how widely to expand and develop the city, the rehousing scheme extended the municipal area and drew the colonial regime into the urban housing market in unprecedented ways.Footnote 84 Through a rehousing committee, it constructed 1,251 two-room suburban houses around Christiansborg, Kaneshi, Mamprobi, Abose Okai, and along South Labadi Road, bringing a rare chance to relocate the Ga just as they were distracted and grieving (see Fig. 1).Footnote 85 But it was an opportunity officials seized upon.

Within a year the incomplete houses became available to shelter homeless earthquake victims temporarily until the rehousing committee converted them into permanent houses arranged in different grades. The committee constructed separate houses for the fishermen across Korle Lagoon. Similarly, it built separate accommodations for Accra's migrant residents who served as manual laborers for the state.Footnote 86 The committee's plan to construct ‘approach roads to better-class areas so that they did not traverse the poorer districts’ envisioned Accra as a class-based segregated city, a layer that would have complicated its racially divided look.Footnote 87 However, wartime shortages and rising costs in building materials and laborers constrained the scheme. The rehousing committee regularly reported setbacks by noting the long list of applicants wanting to purchase unavailable houses.Footnote 88 Demand outstripped supply and housing shortages continued to plague Accra.

In constructing the houses, confusion arose from double land allocation and added to the chaos and dissatisfaction in the Ga communities and with the committee and the colonial state. The custodians of land, including some elders, reallocated land owned and farmed by individuals and families.Footnote 89 At Abose Okai, for example, where the Tagoe brothers had employed manual laborers to work on their three large farms, the rehousing committee sanctioned the destruction of their crops to make way for building new houses. The brothers petitioned for a compensation of £50 but received less than a quarter of that amount after swearing an affidavit and corresponding with different colonial departments many times.Footnote 90 In a similar petition to the colonial governor, one Noi Mensah, who owned a fruit farm at Chorkor, expressed his grievance against the chair of the rehousing committee for alienating his fruit farm ‘by a stroke of the pen without the slightest consideration’.Footnote 91 The monetary compensation for losing his fruits could never make up for the loss. Passed down to him by his forebears, the land held deeper meanings to Noi Mensah.Footnote 92 Any trees not cut down to make way for construction became part of the property of the new houseowner.Footnote 93 In both cases, and numerous similar petitions, colonial officials often redirected petitioners to elders and chiefs, who also could not resolve the grievances satisfactorily.Footnote 94 To the petitioners, their elders and chiefs were in collusion with the colonial state. With no recourse to reclaim their property through traditional authority, the Ga who lost their land saw an ally in the African educated elites who were frequently at odds with the elders and chiefs and would later lead the anticolonial struggle.Footnote 95

The housing scheme magnified unease in the Ga communities about the growing immigrant population. Being a colonial capital, Accra attracted population influx, even amidst its visible physical transformation. The rehousing committee had to grapple with the vexing question of the ‘stranger’ who was a migrant and not from amongst Ga. In some cases, however, it was the migrant ‘outsider’ who had the financial means to purchase or rent a house, afford utilities, and pay rates because of their direct access to the cash economy.Footnote 96 In the beginning of the land negotiations, the elders and custodians of land inserted clauses in land transfer deeds to restrict the committee from freely selling houses to the ‘outsider’.Footnote 97 As expected, the provision was not one that would be followed by a committee seeking to realize its investment and possibly plough profits back into the rehousing scheme.Footnote 98 One Odate Sakyi, who was from Sempey royal lineage in James Town, sought redress by reminding the chair of the rehousing committee quite strongly:

Further I am to inform you that I am a direct nephew of the late Sampy Manche Amege Akwei of James Town Accra, and that I have a priority of claim to Sampey Stool Lands over anyone who has no blood relationship with the Sempeys. As you are aware The Accra Royal Mausoleum Lands at Mamprobi, as the Akan or Twi name implies, are not given to strangers no matter how long they may have been residing in any quarter of Accra. The acting Mankralo and his friends knew this very well but because of money all those who have no immediate use of the two roomed buildings got them although they are strangers.Footnote 99

Royals and Ga within the Sempey community had priority claim over houses in Mamprobi. The colonial administration simply dismissed Odate's complaint and declared that the ‘outsider’ (Nigerian occupant of the house) was ‘properly a tenant of Government and should not be disturbed’.Footnote 100 Official support of the Nigerian occupant violated the clauses in the deed dictating the terms of family and community land transfer. It also disregarded the idea of rehousing, first and foremost, earthquake victims. The earthquake's aftermath gave rise to an early articulation of the concerns of Ga Shifimo Kpee (Ga Standfast Association), a protest movement in mid-1957 against poor housing and the influx of strangers in Accra.Footnote 101

Supporting Odate, a newly formed union of Ga residents in west and northwest Korle Gonno observed correctly that housing had more far-reaching implications for the future of Accra than the committee appeared to see. A stranger housed under the rehousing scheme had a voting right and could determine the city's destiny. When voting was expanding to accommodate the city's expansion, the Ga residents of Kaneshi, Abose Okai, and west and north Korle Gonno found out that they were being ‘clean left out’.Footnote 102 While seeing that the colonial rehousing scheme excluded them from voting, they noticed, to their surprise, that ‘outsiders’ residing in their neighborhoods were:

Entitled to vote and the real citizens of Accra, who indirectly pay rates, etc. are clean left out. We are definitely of the opinion that the franchise was primarily intended for real citizens as well as strangers who rent rooms, now citizens are out and strangers carry a substantial number of votes. Strangers are more or less birds of passage; they are here to earn their living.Footnote 103

Ga households lived in extended families, but the practice of registering a handful of the heads of families excluded other members of the households — who contributed to rent, rate, utility, and the general upkeep of houses — from the official rolls.

Residents lucky to be allocated two-room houses in up-and-coming affluent neighborhoods faced a barrage of challenges in their new homes. Through their neighborhood representatives, residents of Christiansborg Estate showed their dissatisfaction with the new neighborhood and the houses. In a petition to Governor Maxwell Burns in April 1945, they recounted problems and made demands. Initially built as two-room houses planned to be converted for permanent accommodation, the houses did not afford residents a comfortable living. The houses offered poor protection against heat, cold, rains, and burglary, and residents tired of waiting. Not only did they demand structural improvements to the dwellings, but they also appealed for streets and drains. Near the neighborhood was the hospital for lepers, which the residents resented. Residents feared widespread infection as they saw lepers roaming freely in the neighborhood and sharing a public water fountain with them. To them, the living conditions were an impediment to ‘settle peacefully and adjust themselves to the requirements of their social development’.Footnote 104 In making the demands, the residents registered their frustration with the earthquake relief program. Official responses appeared encouraging and further legitimated the claims of the residents, but wartime constraints prevented officials from making the improvements in a timely manner.Footnote 105

Conclusion

Contrary to the expectations of my interviewee and the AMA, the aftermath of a disaster is not always clear-cut. While colonial officials, Ga elders and chiefs, and African elites all saw opportunities in the idea of rebuilding a ‘modern’ Western-style capital city in the aftermath of the earthquake, the specifics of these opportunities differed. These varying interests interacted and clashed with one another between 1939 and 1945. For the colonial state, the disaster provided the opportunity to acquire newly valuable land to rebuild the city to serve its functions as a colonial capital, an entrepôt port city, and a commercial center. Ga chiefs and elders saw in the disaster a chance to acquire land for their personal profit and reassert their traditional authority. Western-educated Africans were excited at the chance to remake a new city along Western lines, hoping that the state would provide adequate housing for the earthquake victims. The colonial state mismanaged these expectations in pursuit of its self-serving vision for the city, thereby spreading frustration across all divisions and constituencies. Further exacerbating the discontent, the official vision of rebuilding the city threatened the fisherfolk and Ga residents with displacement and loss of their livelihoods and social worlds. Some residents actually lost their farmland to urban redevelopment, a project that their chiefs and elders supported. In its lame attempt, the colonial state generated a common sense of frustration, which prepared the ground for the young men, chiefs, and the educated elites to band together.

While the earthquake was an opportunity for the state to seize land and displace the Ga, the disaster provided clarity for the residents of Accra. In the moment of catastrophe, the residents were, of course, distracted trying to survive amid aftershocks and incessant and torrential rainfalls. When the dust settled, however, the city's residents saw clearly the cracks and crevices of colonial rule. The earthquake laid bare the limits of colonial power in both the state's failure to reconstruct the city as it envisioned and the defiance and challenges officials encountered in land acquisition and housing. Before the UGCC, the military veterans, and the CPP appeared on the scene in the capital city after 1945, residents were already frustrated with the colonial state because of the botched earthquake reconstruction efforts. While revealing intense community debate and profound divisions at the granular level, the post-earthquake reconstruction period shows a common anticolonial agitation which bridged different urban constituencies and primed them for the nationalist message.

Acknowledgements

I want to express my gratitude to Jean Allman, Timothy Parsons, and Sara Berry for their support and helpful feedback on previous drafts of this article. I also appreciate Ryan Kirk for creating the map. In addition, I am thankful for the invaluable support provided by Brian Pennington, Baris Kesgin, Amy Allocco, and the Center for the Study of Religion, Culture, and Society at Elon University during the revision process. Lastly, I would like to acknowledge the anonymous reviewers for their constructive and encouraging feedback on the article.