Book contents

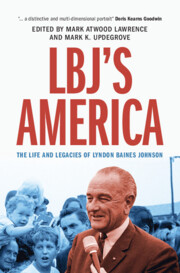

- LBJ’s America

- LBJ’s America

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Contributors

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Power and Purpose: LBJ in the Presidency

- Chapter 2 LBJ and the Contours of American Liberalism

- Chapter 3 Lyndon Johnson and the Transformation of Cold War Conservatism

- Chapter 4 The Great Society and the Beloved Community: Lyndon Johnson, Martin Luther King Jr., and the Partnership That Transformed a Nation

- Chapter 5 Lyndon Johnson, Mexican Americans,and the Border

- Chapter 6 The War on Poverty: How Qualitative Liberalism Prevailed

- Chapter 7 LBJ’s Supreme Court

- Chapter 8 “If I Cannot Get a Whole Loaf, I Will Get What Bread I Can”: LBJ and the Hart–Celler Immigration Act of 1965

- Chapter 9 “It’s Always Hard to Cut Losses”: The Politics of Escalation in Vietnam

- Chapter 10 Lyndon Johnson and the Shifting Global Order

- Chapter 11 “Through a Narrow Glass”: Compassion, Power, and Lyndon Johnson’s Struggle to Make Sense of the Third World

- Afterword: LBJ’s America

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Index

Chapter 1 - Power and Purpose: LBJ in the Presidency

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 19 October 2023

- LBJ’s America

- LBJ’s America

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Contributors

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Power and Purpose: LBJ in the Presidency

- Chapter 2 LBJ and the Contours of American Liberalism

- Chapter 3 Lyndon Johnson and the Transformation of Cold War Conservatism

- Chapter 4 The Great Society and the Beloved Community: Lyndon Johnson, Martin Luther King Jr., and the Partnership That Transformed a Nation

- Chapter 5 Lyndon Johnson, Mexican Americans,and the Border

- Chapter 6 The War on Poverty: How Qualitative Liberalism Prevailed

- Chapter 7 LBJ’s Supreme Court

- Chapter 8 “If I Cannot Get a Whole Loaf, I Will Get What Bread I Can”: LBJ and the Hart–Celler Immigration Act of 1965

- Chapter 9 “It’s Always Hard to Cut Losses”: The Politics of Escalation in Vietnam

- Chapter 10 Lyndon Johnson and the Shifting Global Order

- Chapter 11 “Through a Narrow Glass”: Compassion, Power, and Lyndon Johnson’s Struggle to Make Sense of the Third World

- Afterword: LBJ’s America

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Index

Summary

Warrior, dove, pragmatist, revolutionary, institutionalist – Lyndon Johnson inhabited a range of personas, each of which expressed his hopes, fears, vision, and philosophy. Johnson’s presidency expressed itself in those contradictions, securing extraordinary gains on behalf of those marginalized at home while unleashing bloodshed on millions living abroad. His lifelong desire for recognition, his powerful wish to be loved, his surpassing need to control and dominate, his deep-seated yearning to lift up the oppressed and ennoble the downtrodden – these attributes coalesced in a roughly five-year presidential tenure that harnessed the power of the state to effect fundamental change. This chapter offers a window onto his persona and its impact on his presidency. His strengths and weaknesses are evident in several dimensions of his management style, including his use of people, his workday habits, his pursuit of information, and his decision-making process. Each shaped his triumphs and his failures, and persisted throughout his life and career, as would the principles he gleaned at an early age – both the idealistic and the less ennobling. Collectively, these aspects reveal much about LBJ and his presidency, and provide a backdrop for deeper exploration of his legacy and significance.

Keywords

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- LBJ's AmericaThe Life and Legacies of Lyndon Baines Johnson, pp. 15 - 43Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2023