The catastrophic events in Eastern Europe that began with the First World War and ended with revolution and civil war precipitated a vast displacement of humanity.Footnote 1 This disaster continued beyond the cessation of Russo-German hostilities in 1918. Between the Bolshevik takeover of October 1917 and the end of the Russian civil war in late 1921, between two and three million subjects of the former tsarist empire departed the lands of their birth.Footnote 2 As a result, in the interwar decades, Russian colonies existed in almost every European capital. The scale of the emigration ensured that these communities made their presence felt in their adopted cities and, not by coincidence, the literary and cinematic worlds of the period tempted the European imagination with wistful tales of princesses working as servants, White generals driving taxis and former Okhrana agents drinking their way to a slow death in Parisian cafes.Footnote 3

Perhaps because of this forlorn image of the fallen, the historiography of the emigration has hitherto focused on the plight of the émigrés themselves. Most particularly, it has dwelt on the condition of their existence in Germany, France, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia and elsewhere.Footnote 4 This has included examinations of the émigré contribution to contemporary political and cultural developments, both in a European context and amidst ‘Russia abroad’.Footnote 5 Berlin, for instance, where Vladimir Nabokov temporarily resided, is usually configured as the literary centre of exile.Footnote 6 The French capital, on the other hand, is connected to émigré politics and its internecine struggles. Pavel Miliukov, leader of the centre-right Kadet party, his Socialist Revolutionary counterpart, Viktor Chernov, and the former prime minister of the 1917 Provisional Government, Alexandr Kerenskii, all spent time in Paris. As for Prague, given the overwhelming presence of academics and intellectuals in the city, it acquired the epithet ‘Russian Oxford’ in the 1920s and 1930s.Footnote 7 The overall picture that emerges is of a community broadly composed of the intellectually and culturally talented, various political leaders and those from the highest echelons of tsarist society who slipped through the Bolshevik noose. In its vaguest terms, it is depicted as ‘White’, a notion that belies the social, ethnic and political diversity of the emigration.

Given this slightly skewed perspective, historians have had little to say about the emigration from the perspective of the host state, particularly in relation to the Czechoslovak case. The attitudes and policies of President Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk and his government have merely formed a benevolent backdrop to life as an émigré. This is a surprising historiographical lacuna. After all, this was an age when immigration and its enduringly controversial nature presented dilemmas to all European governments. The most recent study of the émigré community in Prague, for instance, reveals that when Czechoslovakia implemented Russian Action (‘Ruská pomocná akce’) in March 1921 – a scheme instigated and managed by the Czechoslovak ministry of foreign affairs to materially assist Russians in exile – the government granted an allowance of 1,000,000 crowns.Footnote 8 By no means a paltry sum, it appears as no more than a source of temporary succour for the displaced. Initially, Russian Action aimed to support around three thousand émigrés already resident in the first republic, but was also designed to the cover the expense of the transportation of others to, and their resettlement in, Czechoslovakia.Footnote 9 By 1924 the amount expended by the scheme had swelled to some 100 million crowns per annum, though only around 20,000 émigrés lived within Czechoslovakia's borders.Footnote 10

Even allowing for inflation during this economically uncertain period, the regime's financial commitment to the emigration appears sufficient indication of its devotion to the plight of refugee Russians. The Czechoslovak public, the outside world and the émigrés themselves were no doubt persuaded that the policy was humanitarian in intent and, indeed, this has been the view of historians. Elena Chinyaeva, for instance, contends that humanitarian ideals superseded any other intention, with political aims not featuring markedly in the regime's agenda.Footnote 11 Other historians have deemed it ‘an extraordinarily generous gesture . . . unique in the annals of interwar Europe’.Footnote 12 No doubt, from the perspective of exile this appeared the case and it could be easily counterpointed with less generous examples. Contemporary commentators took a similar view and, writing in 1938, Sir John Hope Simpson, author of an extensive study on the refugee problem, regarded Czechoslovakia's policy as ‘astonishingly liberal and far-sighted’.Footnote 13

That the policy was supposedly liberal and forward-thinking has been linked by historians of the Prague emigration, especially Andreyev and Savický, to the general liberal outlook of the first republic, often described as central Europe's ‘bastion of democracy’ in the interwar period.Footnote 14 From their perspective, the generosity of the Masaryk regime chimes easily with its democratic outlook, although they make no effort to assess that democracy critically. Their comments, for instance, on the high levels of press censorship in the first republic did not prompt a reappraisal of the Czechoslovak democratic brand. Rather, they conclude that in order to gain an appreciation of émigré life in Czechoslovakia, the émigré press of another state, such as France or Yugoslavia, should be consulted. Furthermore, Andreyev and Savický express incredulity at the ‘mechanisms of influence’ that sometimes operated in relations between the émigrés and the government.Footnote 15 Surely, though, the whole émigré enterprise mounted by the Masaryk regime was operated entirely via the ‘mechanisms of influence’? The Czechoslovak parliament, for instance, was not consulted about the implementation of Russian Action. As for many policies in the first republic, presidential influence reigned supreme.

In the light of this emphasis on Czechoslovak generosity scholars have noted the republic's role in helping to preserve the essential intellectual, ethnic and cultural strands of Russian life in emigration. These strands were actively encouraged by the setting up of a Russian law faculty, a university, a pedagogical institute and, perhaps most famously, the Russian Historical Archive Abroad. All these institutions received financial assistance from the Czechoslovak state. The support of Russian intellectual and cultural organisations was emphasised by repeated reference, in both government and community discourse, to a shared sense of Slavic destiny. Mark Raeff noted that Russian Action aimed to express gratitude for ‘previous Russian help in furthering the national aspirations of Czechs, Slovaks and other Slavs’.Footnote 16 It seemed obvious, to the instigators of Russian Action and the émigrés themselves, that Russia's displaced should reside in an ostensibly Slavic nation receptive to their needs. The evidence to back up this perspective abounds, not least in the light of the active participation by leading Czechoslovaks in Russian cultural events, and their support for émigré newspapers and institutions besides those of an educational bent.Footnote 17 There were, undoubtedly, many Czechs and Slovaks who felt impelled to reinvigorate slovanstvo – the alleged historical, spiritual and ethnic nexus they shared with Slavic brethren. This relationship also had a political dimension, which had existed since the mid-nineteenth century, but in the recent past had centred on the Neo-Slavic movement that developed in the decade prior to the Great War.Footnote 18

The political reasons for supporting the emigration were not confined to the realms of slovanstvo. Indeed, while much has been written about the community and the manner of its arrival in Czechoslovakia, the deeply embedded political motives of the regime have received only cursory attention. In viewing Russian Action as a ‘generous gesture’, the broader context of Czechoslovak domestic politics has been overlooked or downplayed. Chinyaeva argues, for example, that ‘Russian Action was not directly dependent upon the swings of Czechoslovak internal politics’.Footnote 19 In this regard, the activities of the émigrés themselves, and their organisations and internal relations, have overshadowed the Czechoslovak domestic arena and the role it played in instigating Russian Action.

Yet, for the builders of Czechoslovakia, a number of political considerations surely played a role in Russian Action, since they related to issues crucial throughout the republic's short existence. Ethnic questions, in particular, remained at the forefront of domestic discontent. This was not only the case in relation to the republic's German-speaking minority, the Sudeten-/Böhmendeustche, but also to the Hungarians, Poles, Ukrainians and Rusyns residing within its borders. Further aggravation sprang from Slovaks, who resented the Prague government and its attempt to forge a nation of Czechoslovaks in the Czech image. Did Masaryk and his government consider these factors when embarking on its émigré policy? Given the possibility of internal resentment towards the émigrés, was the potential for an escalation in ethnic tension considered by the regime? And did the possibility that émigrés might share their own grievances and throw in their lot with other disgruntled ethnic groups figure in Masaryk's ambitions?

These questions have not yet been posed convincingly by historians of the Czechoslovak emigration. This omission seems especially curious, since the early 1920s was a period not only of ethnic but also of social tension and of increasing unemployment.Footnote 20 The transition from Habsburg rule to independence was not entirely smooth. At the same time as émigrés were arriving in the republic, prolonged strikes were occurring, for instance in the mining industry. The unstable early years of the new republic culminated, in 1923, with the assassination of the minister of finance, Alois Rašín, widely viewed as the architect of the regime's failed economic policy.

There are other aspects of Czechoslovakia's political motives in promoting Russian immigration that need to be considered. Although the emigration occurred in the midst and as a result of dramatic events, the international dimensions of Czechoslovakia's policy have also been overshadowed by the humanitarian aspect.Footnote 21 Although Czechoslovakia did not intend to embrace en masse the defeated troops of Admiral Anton Denikin's army, its undertaking effectively supported Russia's ‘official’ political opposition. In 1919, among the earliest émigré arrivals were members of the Socialist Revolutionary Party (SRs), who, as their name suggests, were on the left of Russian politics.Footnote 22 This was not an accident of fate. As existing interpretations of the emigration have noted, Masaryk and his government encouraged the SRs to come to Czechoslovakia in order to learn about democracy first-hand.Footnote 23 Once they were fully appraised of this political mystery, it was intended that they should return to Russia and disseminate their knowledge. The Czechoslovak leadership hoped, provided the external impetus was sufficiently guided and encouraged, that a fully fledged, Western-style democracy would be born in Russia. In welcoming opponents of Bolshevism to Czechoslovakia, was the regime wary of infringing on future relations with Russia? To what extent did the potential diplomatic repercussions figure in the government's émigré policy? Again, such key questions have hitherto been eclipsed by the insistence on regarding the Masaryk regime's motivations solely within humanitarian parameters.

This article takes a closer look at the political motives of the Masaryk regime in promoting the resettlement of Russian émigrés to Czechoslovakia. Rather than focusing on benevolence as the core component of Russian Action, it looks beyond the liberal epithets often applied to interwar Czechoslovakia. Rather, it emphasises the need to consider the first republic's policy in the context of a new and ambitious state. At home and abroad, the priority was peace and stability. These, too, appear liberal ambitions, but, as this article indicates, Czechoslovakia was bound by deep-set ideological considerations and eager to claim its place on the international stage. This was especially evident during a crucial phase of the emigration, the massing of refugees in the former Ottoman capital, Constantinople.

Crisis in Constantinople

Until 1921, émigrés arrived in Czechoslovakia in dribs and drabs. Many sought personal intercession from Masaryk and other leaders in order to be allowed to move to Czechoslovakia and seek assistance from Russian Action. There are letters in the archives that recount the pitiful and desperate plight of those driven from Russia by revolution and civil war.Footnote 24 The manner in which such people gained entry into Czechoslovakia again seemingly confirms the regime's open-handedness and benevolence towards émigré Russians. But such cases only partially reveal the government's motives in promoting Russian Action. A fuller picture emerges from the government's reactions to the Russian refugee crisis in south-east Europe in 1921. This crisis was prompted by the final routing of the volunteer army in the Crimea in late 1920, which in turn precipitated a mass evacuation across the Black Sea to various ports in south-east Europe. Its epicentre was Constantinople, where approximately 170,000 former subjects of the Russian empire were to be found.Footnote 25 This humanitarian catastrophe was further exacerbated by thousands of other refugees, scattered throughout Bulgaria, Greece and Anatolia as a result of the break-up of the Ottoman Empire. By the beginning of 1921, such was the scale of Russian refugee crisis that it commanded the attention of the international community, especially the League of Nations.Footnote 26

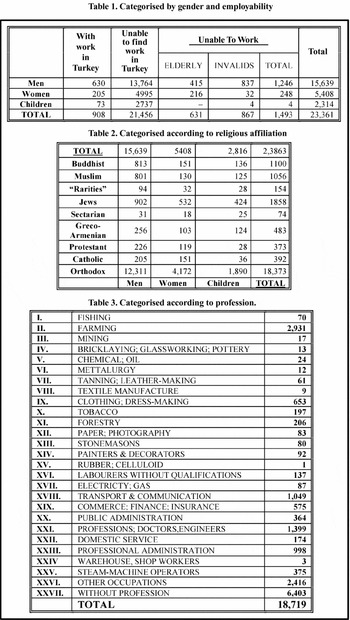

This disaster was seized on by Czechoslovakia as a means of fulfilling its aims in Russian Action. By August 1921 a number of Czechoslovak emissaries, including members of the Czechoslovak Agricultural Union (Zemědělská jednota Ceskoslovenská republiky), reached south-east Europe and toured various refugee camps, including those in Constantinople. In investigating the refugee problem at first hand, the Czechoslovaks were armed with a specific brief.Footnote 27 Out of the thousands of refugees in the city and its environs, certain groups were targeted for relocation to the first republic and readied for imminent return to Russia. Constantinople was host to the full diversity of the emigration, in political, ethnic and social terms (see Figure 3). Of the émigrés already resident in Czechoslovakia, most originated from the political, intellectual and middle classes. But in Constantinople, it was the lowest stratum of tsarist society that was given the highest priority. Agricultural workers were of particular interest. For the Masaryk regime, the social position and potential of these individuals was of the utmost importance. It was imagined that the peasant would prove more susceptible to the correct political influences than other social groups. Ideological considerations, guided by the Czechoslovak state, were the basis for the regime's support of Russian Action.

Czechoslovak motives

In the early 1920s Czechoslovakia's policy towards the Russian emigration was founded on a single premise. Masaryk and his government fervently believed that Bolshevism's foothold in Russia was precarious and that, at any moment, it was bound to collapse. ‘Communism in Russia’, according to Masaryk, ‘exists only on paper’.Footnote 28 Such a view permeated Czechoslovakia's émigré policy throughout the civil war and beyond. The assurance of Red victory in early 1921, did not prompt a reappraisal of Czechoslovak policy. Indeed, Russian Action was instigated in March 1921, long after the death knell of the White armies was sounded. Furthermore, notwithstanding an escalation in the Russian refugee crisis in late 1920 – hastened by the destruction of the White army in the Crimea – Czechoslovakia's conviction as to the fleeting nature of Bolshevism remained unshaken.

The Czechoslovak government's belief that Lenin's regime stood on the precipice of imminent collapse was based on the certainty that, as a political and economic ideology, Bolshevism was simply unworkable. After enduring three years of war and four years of revolution, Russia was, according to Edvard Beneš, Czechoslovakia's foreign minister, ‘at the bottom of an economic and political chasm’.Footnote 29 In his view, even the Bolshevik regime recognised that Russia was living in such desperate times that drastic measures were required, hence the introduction of the New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1921.Footnote 30 NEP allowed for a partial restoration of capitalism in Russia, and to many external observers it appeared to be a Bolshevik admission of communism's failure. For Czechoslovakia the NEP symbolised the last hours of a nine days’ wonder. By 1921, seven catastrophic years ensured the destruction of the essentials for any form of rule. Although other states in Europe had suffered equal privations in this period, the situation was far worse in Russia, since even before the war it had not possessed many of the necessities crucial to a modern state, a view frequently expounded by Masaryk.Footnote 31 In addition, the crisis wrought by the exodus of thousands of people, most of whom appeared to originate from the tsarist empire's embryonic middle and professional classes, ensured that Russia's already primitive social structure was incapable of economic progress. Russia had lost the very people it needed the most. Such a perspective, widely shared by the first republic's leadership, encouraged the notion that Bolshevism's demise was not too far away. It was not surprising, given this view, that in implementing Russian Action the Czechoslovak government gave no consideration to domestic ethnic questions or to diplomatic relations with Russia. The émigré residence in Czechoslovakia was expected to be of short duration. In the diplomatic arena, the first republic expected that it would soon do business with a new Russian government, one which would presumably be serviced by grateful former émigrés.

At first glance, it appears extraordinary that such a small state, which survived for barely twenty years, should have aspired to take such a prominent role in the revival of a state much bigger and more important than itself in an international context. This rings true not only because Czechoslovakia was a self-designated ‘small nation’ in Europe, but also because it was a new state, born from Habsburg ashes in October 1918.Footnote 32 Prior to this, Czechoslovakia's component parts had been subsumed under Habsburg rule, with no national autonomy (a dream to which Masaryk and others had aspired in the 1890s), let alone any role in international affairs. However, the First World War had undoubtedly endowed the leaders of this new state with incredible self-confidence. In particular, the acknowledgement of T. G. Masaryk and his compatriots Edvard Beneš and Milán Štefánik as the legitimate leaders of Czechoslovakia by the British, French and, later, US governments, no doubt contributed to this.Footnote 33 So, too, did the active role the Czechs, in particular, played at the Paris Peace Conference.Footnote 34 At the beginning of the 1920s Czechoslovakia's position on the world stage appeared, therefore, guaranteed, especially in the wake of Edvard Beneš's efforts at settling the uneasy relations in central Europe with Czechoslovakia's ratification of the ‘little entente’ with Romania and Yugoslavia in 1920–1.Footnote 35

In addition, given the absence from the European scene of a disgraced Germany, Austria and Hungary and of a chaotic Russia, Czechoslovakia's belief in its place as an equal alongside Britain and France should not be viewed entirely with incredulity. Its position in the League of Nations, for instance, reaffirmed its elevated position in the international hierarchy. The League took very seriously its contributions to both the Russian refugee crisis and famine relief.Footnote 36 Czechoslovakia appeared, at least to itself, as a key component of the postwar world order and in the immediate future it did not see any possible challenge to this, not least since it shared much of the world-view of its fellow-victors at Versailles, including a pronounced anti-Bolshevik outlook. The early 1920s was, of course, a period of extreme anti-Bolshevik sentiment, when horror stories about Lenin's land were the daily diet of western Europe's newspaper readers. It is not surprising that the League of Nations and its signatories grasped at the optimistic hope that Bolshevism's end was none too distant.Footnote 37 Such views were also found in the United States. The organisation that led to the distribution of famine relief in Russia in 1921–2, Herbert Hoover's American Relief Association (ARA), appointed a number of military figures who, once Bolshevism started to teeter, would be on the spot to supply the death blow.Footnote 38

Anti-Bolshevik sentiment reverberated throughout the Czechoslovak hierarchy in the early 1920s.Footnote 39 In a regime dominated by intellectuals, several leading scions wrote books and articles and gave speeches on anti-Bolshevik themes. Masaryk and his regime made little secret of these tendencies and, not by coincidence, Czechoslovakia was one of the last states to grant de jure recognition to the USSR, in 1935. In the early years of independence, Masaryk, for whom Russia and its people were a long-held fascination, declared Bolshevism to be the ‘logical consequence of Russian illogicality’ and his numerous public pronouncements on Lenin's revolution left little doubt as to his convictions.Footnote 40 During a speech he delivered to coal miners in Březové Hory, south-west Bohemia, in 1920, the Czechoslovak president pointed out the ease with which Bolshevism had claimed power in Russia. This was due, in large part, to Russia's illiterate peasant population.Footnote 41 The docile, unworldly and primitive Russian peasant was, in Masaryk's view, unprepared for social and political revolution and formed a passive mass, unable to react to the Bolshevik whirlwind.Footnote 42 These observations were voiced with some authority, as Masaryk was considered a leading expert on Russia at this time,Footnote 43 attested by his many visits there, before and during the First World War, and, in particular, his book The Spirit of Russia (originally published in German as Rußland und Europa), a meticulous assessment of tsarist politics and society.Footnote 44

Another prominent figure, Karel Kramář, the republic's first prime minister (1918–19), was renowned for his anti-Soviet opinions. In his 1921 book, Ruská krise (The Russian crisis), Kramář propounded an historical assessment of Russia and the reasons why it had succumbed to Bolshevism. Once again, the passivity of the peasantry was cited.Footnote 45 It might be said that, married to a Russian, he had a personal investment in the fate of the former tsarist empire, although his leading role in the Neo-Slavic movement revealed a life-long interest in Russia and its people.Footnote 46 Kramář's dedication to slovanstvo continued throughout the interwar period. It was, in part, his belief in panslavic brotherhood that led him, in 1919, to set up the first relief programme for Russians fleeing Bolshevism.Footnote 47 Later on, he became a key figure for émigrés and it was often through his personal intervention that refugees were permitted to settle in Czechoslovakia.Footnote 48 Moreover, as one of Czechoslovakia's delegates at the Paris Peace Conference, Kramář repeatedly advocated the necessity of creating a ‘panslavic democratic federation’.Footnote 49

Despite its apparently western orientation and friendly relations with France and Britain, especially as espoused by foreign minister Beneš, Czechoslovakia's leaders were still held by older attractions such as panslavism. The confidence that emanated from the Czechoslovak hierarchy ensured that there was a widespread view that panslavism's destiny lay in Czechoslovak hands. Writing to Masaryk during the Paris Peace Conference in February 1919, Kramář observed:

If Russia can be saved and a Slavic democracy created, under a republican federation, it would be our construction and in the future we would be prominent in the Slavic [world] – and we would not have to be afraid of German Ostpolitik and a German–Russian–Japanese alliance.Footnote 50

The need to save Russia from Bolshevism and to guarantee Europe's future security was a commitment to which Czechoslovakia had already subscribed. This was apparent through its involvement during the revolutionary events of 1917 and the creation of the Czech Legions, which played a role in the Russian Civil War.Footnote 51 Old allegiances and bonds imbued the first republic with a sense of mission about Russia. Again, although this appears quite out of proportion to its standing on an international scale, from the Czechoslovak perspective this was not a misjudged mission. After all, against all odds, a small state which had been ruled by another government for over three hundred years had managed to achieve independence. In a sense, therefore, the unachievable had already been attained. Why, therefore, could Russia not be saved?

In a notional Slavic hierarchy, Czechs and Slovaks were the success story for the first time. The aftermath of world war and revolution prompted the displacement of a position previously occupied by Russia. In addition, despite the rebirth of an independent Poland and the creation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, Czechs and Slovaks were more suited to the task than any other Slavic peoples. Poland, for instance, was deemed by Masaryk as too unstable internally and Ukraine as incapable of taking ‘the lead’.Footnote 52 Only Czechoslovakia was in a position to ensure the continued existence of panslavic aspirations. Such ambitions reveal a great deal about the political culture of this newcomer to Europe. In the domestic arena, the parliament was confidently forging a new state with the ratification of the constitution and introduction of various laws which attempted to mould a disparate people into one nationality, Czechoslovaks.Footnote 53 If national revolution was being forged successfully at home, why not abroad?

That Czechoslovakia had a role to play in international matters was amply expressed in Edvard Beneš's 1921 foreign-policy speech. He listed Czechoslovak spheres of influence throughout the continent, although he decried any need for direct intervention in Russia, in other words a military campaign. Instead, he referred to the ‘decisive phase’ which was occurring at that moment and strongly hinted at a Bolshevik loss of power. It was ‘impossible’, he noted, ‘for the regime to survive for much longer in its present form’.Footnote 54 At this time, Beneš did not personally advocate a panslav policy for Czechoslovakia. Instead, his gaze was set firmly westwards, towards France and Britain.Footnote 55 It was not until the late 1930s, and most particularly during the Second World War and its aftermath, that he believed that Czechoslovakia's fate was inextricably bound up with that of Russia.Footnote 56 Nevertheless, Russian Action was instigated under the auspices of the foreign ministry, drawing resources directly from its coffers. For Beneš, therefore, the need to encourage émigrés to relocate to Czechoslovakia was impelled by something other than slovanstvo.

In view of Bolshevism's impending collapse, the Czechoslovak government felt itself incumbent to make practical preparations for the future Russia. The emigration, albeit a human tragedy, could be utilised for the advantage of Russia and the world. Once Bolshevism ceased to exist, Russia would require a swift injection of expertise from a range of professions, including intellectuals, engineers, scientists and teachers, in order that its society and economy could be resuscitated. Moreover, as the 1921 famine in Ukraine and the western provinces had demonstrated, it also required expertise in agriculture. In declarations at the League of Nations, famine and refugee relief were linked, revealing Czechoslovakia's single purpose:

On 10th February 1922, the Secretary-General of the League of Nations communicated to the Members of the League a memorandum which he had just received from the Czechoslovak Government regarding the help to be afforded to Russian refugees and the famine-stricken Russian population. The Czechoslovak Government explained that from its point of view these two questions must be considered and solved together. The economic situation of Russia at the present time requires a large number of specialist workers, both intellectual and manual, to restore the normal economic life of the country. The Czechoslovak government is convinced that these necessary ‘active forces’ must be chosen from among the Russian refugees.Footnote 57

The future Russia, in Czechoslovak eyes, would remain a predominantly agricultural state.Footnote 58 Russian peasants were to be schooled in Czechoslovakia's advanced agricultural technology, new knowledge that would instigate unheard-of progress in the Russian countryside. There was a final aim in Czechoslovakia's policy towards peasant refugees. In directly invigorating Russian agriculture and dragging it out of its medieval past, Czechoslovakia would reap further future benefits by ensuring economic links between the two states.Footnote 59 The potential dividends were, therefore, numerous.

It was a policy supported by another anti-Bolshevik politician, Antonín Svehla, leader of the Czechoslovak Agrarian Party (Republikánská strana zemědělského a malorolnického lidu), which arguably played the most important role in stabilising Czechoslovak parliamentary politics and, as part of the famous Pětka (Five), the ruling coalition, in the 1920s. Occupying the right of Czechoslovak politics, as its title suggested, it represented rural smallholders and peasants. Russian Action was publicly encouraged through the party's daily newspaper Venkov (Countryside) and from October 1921 it featured a regular ‘Russian section’ (in Russian).Footnote 60 At the 1922 party congress, the year after Russian Action was instigated, the Agrarians adopted a programme which included a condemnation of Bolshevism and expressed the ‘desire that Russia would “once again become an equal factor in the world economy”‘. A central tenet of the Agrarians’ world-view was a belief that the Slavs’ historical roots lay in the peasantry. It was hardly surprising, therefore, that it supported Russian Action, or that an associated institution, the Czechoslovak Agricultural Union, did too.Footnote 61

The intertwined assistance to emigration and famine relief encouraged justification of the policy in the Czechoslovak press, often with anti-Bolshevik overtones. In Venkov, the conservative organ of the Agrarians, famine relief was described as ‘practical slovanstvo’, in the economic interest of not just Russia, but the world.Footnote 62 Svěhla's party also declared an affiliation with Viktor Chernov and the SRs in Venkov.Footnote 63 Sympathy for the victims of the famine appeared in Lidový Noviny (People's News), which represented the centre ground in Czechoslovak politics. An article penned by the former Czech Legionnaire and future playwright František Langer drew a stark picture of the 1921 famine and urged compassion for its victims, noting the involvement of other civilised states, such as France and the United States.Footnote 64Lidový Noviny also approvingly discussed Czechoslovakia's plan for Russian émigrés.Footnote 65 Furthermore, it overtly criticised the Bolshevik regime for pursuing its ideological aims, rather than filling the bellies of its citizens. A cartoon by Joseph Lada, a satirist most famous for his illustrations to Jaroslav Hašek's The Good Soldier Švejk, portrayed Russia as an emaciated bear, driven on by the Bolshevik whip (Figure 1). A similar theme was evident in a cartoon by František Kratochvíl, another important satirist of the interwar period, who mocked Maxim Gorkii's appeal to Europe for famine relief while carrying the firebrand of revolution (Figure 2).

Figure 1. ‘The Pathetic Russian Bear’. Mr Hoover: ‘Mr Lenin, that bear must be fed as well as trained.’ Josef Lada, Lidové Noviny, 20 Sept. 1921, 4.

Figure 2. ‘Incompatibility’. (Maxim Gorkii asking for Europe's help) ‘If you want to set the fires of revolution there, Maxim, don't come begging with your cap in hand here.’ František Kratochvíl, Lidové Noviny, 1 Sept. 1921, p. 4.

There was, therefore, implicit and explicit support for the regime's Russian policy from sections of the press. One newspaper, however, made repeated attacks on Russian Action, émigrés, the Masaryk government and its members. Rudé Pravo (Red Right), the daily newspaper of the Czechoslovak Communist Party (Komunistická strana Československa – KSC) was vociferous in its denunciations, although it was not controlled by a ‘truly “Bolshevik” leadership’ at this moment.Footnote 66 Nevertheless, its defence of Communist Russia was inevitable. Although the KSC was not a party of government in the early 1920s, it attracted extensive popular support, especially in municipal elections in Prague. Its newspaper reflected the KSC's critical view of the Masaryk regime and was unafraid of attacking individual figures, especially on the right. Russian Action, inevitably, drew its venom.

Rude Pravo often attacked Kramář for his association with Russian Action.Footnote 67 In addition, the émigrés themselves appeared in its pages in a variety of negative guises. Those already resident in the first republic were described as ‘General Wrangel's [Commander of the Volunteer Army] mercenaries’ and ‘martyrs’, ‘fascists’, antisemitic ‘Black Hundreds’, ‘Germanophiles’ and as part of an international plot to spread reactionary and monarchist propaganda.Footnote 68Rudé Pravo also played on a host of potential domestic insecurities. In particular, it drew a direct correlation between the current economic crisis, widespread unemployment and industrial unrest in Czechoslovakia, and the government's funding of émigrés. In 1922 it announced, ‘One thousand Czech agricultural workers are without work! In their homeland they are living in terrible poverty!’ And yet, it observed, the government had brought one thousand ‘Wrangel mercenaries to Czechoslovakia’ and provided them with employment which honest Czechs had been denied. As a result, in the view of Rudé Pravo, the government was actively ‘supporting counter-revolutionaries throughout Europe’.Footnote 69

The concerns of Rudé Pravo raise questions about the true political orientation of the Russian arrivals in the first republic and how closely this was monitored by the regime. As already noted, in Bolshevik eyes the Masaryk regime has already welcomed counter-revolutionaries, in the form of SRs, but they could hardly be characterised in the same light as the ‘Wrangel mercenaries’ derided by Rudé Pravo. Given the concerns raised in some corners of the press, did the Czechoslovak government consider the political outlook of further arrivals? A foreign ministry pamphlet, published in 1924, outlined the essential criteria that were applied, in theory, to all émigrés seeking refuge in Czechoslovakia:

1. The poverty of the petitioner is the sine qua non of assistance.

2. The goal of the Action does not solely consist of supplying the means of subsistence for émigrés, but they are encouraged to work, notably intellectual work, knowledge which will assist their nation after their return to Russia.

3. Assistance is not to be influenced by political, religious and ethnic considerations.

4. The abuse of assistance through the promotion of counter-revolutionary propaganda is forbidden.Footnote 70

Clearly, the latter clauses indicate that political considerations played a part in Russian Action's implementation. The regime was concerned that émigré groups of an overtly political colouring might create problems for Czechoslovakia, both internally and externally. In particular, soldiers and officers of the Volunteer Army were not welcome in Czechoslovakia, precisely because they often espoused undesirable political views.Footnote 71 This was a far-sighted perspective. In 1922, a letter to the ministry of foreign affairs revealed that in Yugoslavia, where a large section of the Russia emigration was military in origin, soldiers often fell victim to pro-German and pro-Bolshevik propaganda.Footnote 72 Such individuals would, of course, have fallen precisely into Rudé Pravo's category of ‘Wrangel mercenaries’.

Czechoslovakia found it difficult, however, to adhere to these principles, not least because of the diversity of the emigration. This was especially the case when confronting the humanitarian disaster in Constantinople. Those brought from Constantinople were no doubt impoverished, but, as we shall see, their political orientation endangered any hope that émigrés would not promote counter-revolutionary propaganda. In addition, the 1924 regulations did not reveal the entire scope of the Czechoslovak programme, since they made no reference to the desire to bring peasant émigrés to the first republic. Yet in Constantinople these people were found at the top of Czechoslovakia and the League of Nations’ agenda.

The mission in Constantinople

At the same time as Czechoslovak representatives turned up in Constantinople to view prospective candidates for resettlement, the League of Nations despatched its special commissioner, Sir Samuel Hoare. Events in Constantinople, which remained jointly occupied by France, Britain and Italy until 1923, commanded the immediate attention of the international community. This was hardly surprising, since it occupied a crucial strategic position and the anxiety generated was heightened by the fear of Bolshevik infiltration in Anatolia. The early resolution of the Russian refugee crisis was, therefore, high on the international community's agenda and it fully mobilised the resources of the League. It was largely due to Hoare's initiative and the willingness of several states to take in sufficient numbers of refugees that, by the end of 1923, the Constantinople problem was considerably dissipated.Footnote 73 Hoare was well connected to the Masaryk regime and, during the First World War, was an important supporter in Whitehall of the Czech and Slovak independence movement.Footnote 74 In the early years of independence he was a regular visitor to Prague, and during the Constantinople crisis he maintained a correspondence with Edvard Beneš. It is evident from these exchanges that the aims of Hoare's visit to Constantinople were comparable to those of the Czechoslovak delegation.Footnote 75

Figure 3 Samuel Hoare's Census of Russian Refugees in Constantinople, Sept. 1921 (Samuel Hoare to Fridtjof Nansen, 8 Feb. 1922, Part II, Box 4, File 8, TEM. The original version is in French). Only Table 2 tallies correctly.

On arriving in Constantinople, Hoare undertook to draw up a survey of its Russian habitants. Although it only represented a fraction of the total emigration, its revelations may have further impelled the certainty of Bolshevism's impending downfall in Czechoslovakia. While it surveyed just 25,000 refugees, it revealed that Russia was now deprived of thousands of skilled workers from a wide variety of professions (Figure 3). More than 50 per cent of the total was formed by people who represented occupations from the professional and skilled strata of tsarist life. They had once been doctors, engineers, civil servants, transport and communication workers, and employees in the empire's insurance, financial and commercial sectors. No small part, therefore, originated from the tsarist empire's emergent middle class. At the lower end of the social scale were domestic servants, dressmakers, labourers and peasants, although those in the agricultural sector were classified under the heading ‘farming’.Footnote 76

The presence of so many skilled workers among the refugees in Constantinople may have given the Czechoslovak delegation cause to wonder as to how Russia could possibly be resurrected without them? How, for instance, in the absence of engineers, could the shattered railway system be rebuilt? Little wonder, therefore, that the Masaryk regime encouraged engineers to come to Czechoslovakia and they were among those who directly appealed to the president and Kramář.Footnote 77 In other respects, however, Hoare's survey must have been a disappointment. When compared with the social structure of imperial Russia, it revealed an imbalance in relation to the lower social orders. The total drawn from the agricultural class (fewer than 3,000), in particular, bore little statistical correlation to the peasantry which made up around 85 per cent of the tsarist empire. Nevertheless, recruitment from the agricultural classes remained the priority for the representatives of the Agricultural Union, and they set about finding suitable candidates.Footnote 78

By early November 1921, an initial party of approximately 900 refugees was on its way to Czechoslovakia. A second party, of around 1,100, departed two weeks later.Footnote 79 In an ironic twist, however, the search for agricultural workers led the Union to the large community of Cossacks lodged in south-eastern Europe. Indeed, almost all those recruited from Constantinople belonged to one Cossack Host (clan) or other, including Don, Kuban and Terek. Others were recruited from the community of Kalmyks, a Mongol tribe, but who described themselves as Cossacks.Footnote 80 Inadvertently the Union recruited representatives from the most conservative and reactionary social and political elements of the former tsarist empire. Not only were Cossacks infamous for their supreme role in violently quelling disorder during the tsarist era, but they were the initial recruits to the Volunteer Army formed in late 1918. They were, therefore, the first of Bolshevism's sworn enemies in the civil war, but they reflected precisely the kind of right-wing, militaristic sections of the emigration that Czechoslovakia did not wish to see relocated within its borders.Footnote 81 However, given the limitations placed on Czechoslovakia's representatives in Constantinople, by both the Masaryk government and the League of Nations, it was essential to adhere to the social criteria already laid down. The priority was to enlist from the lowest social orders and it is clear from the correspondence that the Agricultural Union was fully aware that its recruits were Cossacks, since it dealt directly with the leaders of several Hosts.Footnote 82 Cossack relief agencies also made direct appeals to Czechoslovakia's representatives.Footnote 83

In presenting the case for relocation to Cossack leaders in Constantinople and to those who were among the first to leave for Czechoslovakia, the Masaryk regime's delegates were keen to awaken panslavic feelings and alluded to a shared sense of destiny between Russians and Czechoslovaks. They also promised the prospect of a useful stay in central Europe. In a speech to departing refugees, reported in one of Constantinople's émigré newspapers, the Czechoslovak consul, Dr V. Vitek, plucked heavily at Slavic heartstrings. He also expressed the hope that those relocating to Czechoslovakia would make the most of their experiences there, which, he anticipated, would be of short duration:

Our agriculturalists, inspired by a warm and fraternal sympathy for the Russian people, have sent me to Constantinople to help you, our Russian brothers . . . We intend to work with you [in Czechoslovakia] for the economic restoration of your rich country. When you get to our country, you will be studying our intensive system of agriculture. The Agricultural Union will organise courses for you on agricultural science, and you will be shown instructive cultural models and industrial enterprises. I ask you to profit from the occasion by studying a variety of matters which will prove useful in the future for the regenerated Russia . . . I wish you bon voyage, my brother cultivators, and for the joining of our work for our mutual benefit and for la Grande Russia slave!

These sentiments were matched by a Cossack representative, Pavel Dudakov, who tried to allay any concerns held by those embarking on the journey to Czechoslovakia:

You are not leaving enslaved, but as brothers and disciples. The fertile regions of the Don are devastated and transformed into a desert. Study culture and science in a rich country and you will acquire useful knowledge for the future.

It is not surprising that those leaving Constantinople were worried about what a future in Czechoslovakia would hold for them. They must have wondered whether they would ever be able to return to Russia, but moving to a strange land surely precipitated fears of one kind or another. Certainly, there were worries about what they would be required to do once they reached Czechoslovakia, and these were evident in Vitek's speech:

We have not come here to look for agricultural workers: we wish to welcome you in [Czechoslovakia] as our brothers and to share a morsel of bread with you . . . and like true Slavs, share hard agricultural work.

Given Vitek's reassurances, it is evident that some Cossacks were concerned that they might merely be employed as labourers in Czechoslovakia.Footnote 84

These fears were not without foundation. Although Czechoslovakia had a clear ideological purpose in assisting the Cossacks, it is evident from correspondence between the League of Nations and the Masaryk government that these refugees were regarded as agricultural labourers who could be retrained easily. A telegram sent by Hoare to Beneš revealed that Constantinople's refugees were indeed destined to experience hard agricultural work in Czechoslovakia:

I am very anxious to ensure arrival of all russian labourers in time for agricultural season STOP as journey takes long time . . . STOP if there is [risk] of any labourers failing to obtain work upon their arrival and becoming a charge of your government we could guarantee maintenance for short period.Footnote 85

At no point in the correspondence, however, was the term ‘peasant’, either in Czech (sedlák), Russian (muzhik) or English, employed to describe the Cossacks.Footnote 86 Yet being described as an agricultural labourer may not have given comfort to those embarking on the arduous journey from Constantinople, and Cossacks, accustomed to a distinctive position in tsarist life, were surely concerned about their future status.

Additional comfort was not to be gleaned once the first party reached Czechoslovakia. While some were enrolled in higher educational institutions, the majority of the 2,000 or so who eventually made it to the first republic, after a convoluted journey over sea and land, wound up working on farms in Moravia.Footnote 87 No doubt they were granted first-hand experience of Czechoslovak agricultural methods, but it was achieved by hard endeavour. Many laboured from four o'clock in the morning until ten o'clock in the evening, endured unheated living quarters in winter and received pay of between 10 and 180 Czechoslovak crowns per month. A long letter of protest about these conditions was sent by Cossack leaders to the ministry of foreign affairs and the Agricultural Union. In addition, concern was expressed about the perceived diminution of social status that the Cossacks believed they suffered in Czechoslovakia. It was requested, in particular, that a passport be issued specifically for Cossacks, in order that they be ethnically and socially distinguished from other refugee groups.Footnote 88 Correspondence between the foreign ministry and the Agricultural Union further hinted at these problems.Footnote 89

By the end of 1922, and certainly by the beginning of 1923, Cossacks working on Moravian farms were moved to act on their position in Czechoslovakia. Many voted with their feet. Some sought new lives in France and Yugoslavia, while others took advantage of the changing diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia.Footnote 90 In 1923, after the USSR granted an amnesty to specific categories of refugee, Cossacks included, many were permitted return to their former home provinces.Footnote 91 A handful of Cossacks and Kalmyks remained in Czechoslovakia in the 1920s, but most were enrolled on courses in higher education or were granted financial relief from the funds of Russian Action.Footnote 92 Those who did stay behind were often viewed with suspicion by the Czechoslovak authorities and any hint of political activity was subjected to government surveillance.Footnote 93 Thus the potential for émigrés to stir up internal political disorder was endlessly on the mind of the regime.

On a number of levels, the Czechoslovak policy towards agricultural refugees can be deemed to have failed. Originally the Masaryk regime intended that around 5,000 or more agricultural workers should be recruited for relocation to the first republic, an undertaking guaranteed to the League.Footnote 94 In the end, however, no more than 2,000 made it to Czechoslovakia, with another 1,000 enrolled in institutions of higher education. For those set to work on Moravian farms, the widespread disappointment at their treatment in Czechoslovakia is palpable in correspondence to the Agricultural Union and the foreign ministry. For this particular group of refugees the policy disappointed at the most basic human level. The fact that the policy's intentions were ideological, not humanitarian, was the fundamental reason for its failure. Had the regime been more concerned about these refugees as people, and not as tokens of ideological confrontation, their human needs might have been met more substantially. The scheme's final failure was heralded by the government's inability to recruit sufficient numbers. Once those who made it to the first republic began to express dissatisfaction, this particular component of Czechoslovakia's refugee policy was abandoned.

It did not follow, however, that Russian Action was discarded in its entirety, even when it became apparent that Bolshevism, at least in its Soviet manifestation, was not about to collapse. Indeed, the Masaryk regime acknowledged the presence of the USSR in European affairs in 1923, when various trade agreements were signed between the two states and the first diplomatic representative of the USSR, K. K. Yurienev, was permitted residence in Prague.Footnote 95 Nevertheless, the hand of welcome remained extended to Russian émigrés, and their influx into Czechoslovakia continued until 1925.Footnote 96 But the policy of Russian Action had to be realigned, although the Masaryk regime's financial and cultural support remained in place until the demise of the first republic in September 1938. Overt statements, however, about the need to rebuild Russia were not made after the late 1920s, although Rudé Pravo remained convinced into the 1930s that the Czechoslovak government was actively supporting counter-revolutionary forces in Europe.Footnote 97 Again, it was not too far from the mark, since the Masaryk and Beneš regimes issued regular payments to prominent émigrés, including Chernov, General Brusilov and Kerenskii, and to various publications, until the 1930s.Footnote 98

The real abandonment of Russian Action by Czechoslovakia came during the new (third) republic created in 1945, when Beneš's volte-face in foreign policy had already taken place. During the Second World War Beneš increasingly believed that Czechoslovakia's interests lay not in the west, but in the east. The ‘gifting’ of the Russian Historical Archive Abroad, assiduously built by émigrés in the 1920s, from Czechoslovakia to the Soviet Union, symbolised not only the end of Russian Action's aspirations, but the changing tide in Europe's political and diplomatic alignments.Footnote 99 It also emphasised that throughout its existence the emigration was regarded by the Czechoslovaks in ideological, rather than humanitarian, terms.