In the previous chapter, I demonstrated that William Turner’s “commonwealth thinking” enabled him to navigate the competing notions for textual authority that emerged in his writing. Turner’s bibliographic self-consciousness, his awareness of how print could serve his professional and spiritual interests, continued to develop over the course of his careers as a physician, natural historian, and divine. For Turner, disseminated printed books could serve as surrogates for their absent author, multiplying a singular text’s impact by being in many places at once. Yet printed books could also serve as nuanced opportunities for authors to display their domination over a knowledge domain that was – thanks to print – ever increasing. As more and more printed herbals emerged on the continent, herbalists like Turner needed to manage not only their own investigations into plants but also the threat of information overload.Footnote 1 Paradoxically, because it is much easier to edit and revise a printed codex than to assemble a large manuscript book from scratch, the affordances of print helped authors sort and manage these concerns, and Turner continued to revise earlier editions of his magnum opus even as he wrote new material.

By coupling his roles of natural historian and reformer, Turner’s commonwealth thinking caused him to view his role within printed English botany as serving as a local authority gathering botanical knowledge on England’s behalf, incorporating the work of foreign others into his native own. Though he expresses some trepidation that his synthesis may be seen as the product of other men’s labor, Turner insisted that his acts of approval and correction simply brought accuracy to existing accounts of the beauty of God’s creation – a creation that has only one true Author. As he sought to make herbal knowledge widely known within the English commonwealth, Turner could therefore evaluate continental herbal editions and amplify those authors whose accuracy he found worthy of citation; and where other herbalists were found wanting, Turner could use his own work as an opportunity to correct their deficiencies. Turner’s appeal to the English herbalist’s communal role, and his bibliographic ego, would cast a long shadow upon the English herbals that followed.

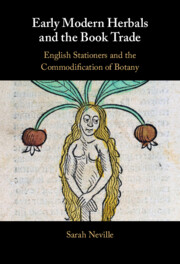

In the concluding chapter of this book, I show how Turner’s anthological approach to herbal authorship was widely understood to be a feature of the genre by returning to the large, illustrated herbal that was the subject of my prologue: John Gerard’s Herball, or General Historie of Plants, first set into print by Bonham and John Norton in 1597 (Figure 8.1).Footnote 2 This commodious work of 1,392 folio pages (plus preliminaries and indexes) contained 2,190 distinct woodcuts, including the first printed illustration of the potato.Footnote 3 Gerard’s Herball was remarkably successful: it was twice reprinted, and it remained an authoritative botanical textbook through the eighteenth century. Copies of the book were regularly bequeathed by name in wills, and as we have seen, poets such as John Milton profitably mined its descriptions for details about plants and their uses. Yet despite the evidence of Gerard’s wide renown among his contemporaries, his reputation as a herbalist has suffered from accusations of plagiarism that have plagued discussions of his work since the publication of the book’s revised second edition in 1633. This chapter will explain how this narrative about Gerard’s 1597 Herball came about, paying close attention to the perspectives of the volume’s publishers to reveal that the logic of the traditional account of Gerard as a plagiarist makes little sense in the context of early modern herbal publication.

Figure 8.1 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie of Plants (1597).

Thinking Materially about The Herball (1597)

Because of their complex and expensive formatting, large herbals are a monumental publishing endeavor, and illustrated printed books like The Herball often found their genesis not in individual authors but in the publishers who would finance and profit from the sale of such books. Such conditions were foundational to the genre: in 1542, Leonhart Fuchs singled out his publisher, Michael Isingrin, as being put to “enormous expense in publishing this work,” an effort that Fuchs tried to honor in the dedicatory epistle to De historia stirpium. The book’s imperial decree was designed to protect not Fuchs’s authorial rights but Isingrin’s substantial financial investment. Unfortunately, the accuracy of images of God’s creation proved hard to protect with a royal privilege, and, as I reveal in Chapter 1, the illustrations of De historia were soon copied by other publishers eager to market herbals of their own. Within three decades, the collaborative woodblocks of plants made by Albrecht Meyer, Heinrich Füllmaurer, and Viet Rudolf Speckle for Fuchs’s herbal had been copied and recopied in books throughout Europe – including in Turner’s celebrated Herball of 1551–1568.Footnote 4 As early modern readers’ demands for illustrated herbals increased, the woodblocks that supplied these botanical images were likewise in high demand among the publishers who catered to these customers. Matched sets of botanical woodblocks became commodities that could generate rental incomes for the publishers who owned them. Accessing a suitable set of woodcuts, therefore, was a priority for any publisher who wished to invest in an illustrated new herbal but who did not have the extraordinary resources required to commission thousands of woodblocks for themself.Footnote 5

I have argued throughout this book that historians of herbals need to “think materially” in order to better understand the way that the genre developed in early modern England from unillustrated, anonymous small-format books into the massive folio tomes authored by the “fathers” of English botany. Thinking materially involves recognizing the commercial and artisanal agents who were responsible for a book’s production, and it inhibits the hasty, but common, critical instinct to credit a work’s appearance in print to the author responsible for its verbal text. Attention to the ways that printed books circulated as valuable commodities reveals that this impulse to “author-ize” printed artifacts can be misleading; when reading the book as a crafted object, the complexity of the thing we call “Gerard’s Herball” reveals that its creation was instigated not through the textual efforts of the man whose name eventually prominently appears on the work’s engraved title page but through the investment and the skill of the book’s manufacturers. In Brett Elliott’s words, a volume like Gerard’s Herball was “a publisher-led book.”Footnote 6

In order to net a profit, a printing project on the scale of The Herball needed to be led by someone with advanced management and marketing skills. John Norton would later become one of the most successful English stationers of his age, a figure whose systematic comprehension of the European book trade would enable him to be the primary bookseller to Sir Thomas Bodley, the founder of Oxford’s Bodleian Library.Footnote 7 Like his stationer forebear John Day, Norton’s aptitude for evaluating and selecting books to invest in was demonstratively superior to that of his contemporaries, a talent that served Norton well from the moment he obtained his freedom of the City in July 1586. Norton had been bound to his uncle, the bookseller William Norton, as an apprentice quite late, at the age of twenty-one, and his maturity upon his freedom seven years later allowed him immediately to locate opportunities for profit in the import trade. John Barnard identifies his skill as a “cultural broker and facilitator … Norton’s business shows how far early seventeenth-century capitalism depended upon the effective utilisation of the openings provided by kinship, clientage, patronage, and government favour.”Footnote 8 Key to Norton’s lasting relationship to Bodley was the stationer’s deep familiarity with continental and English book trends, a familiarity that allowed Norton to notice that, despite the English translations of Dodoens that occasionally reappeared in London bookshops, an Englishman had not authored an illustrated vernacular herbal since the last publication of William Turner in 1568. Such a considerable investment required careful planning, and what Norton did in response to this perceived gap in the marketplace suggests his awareness that there were requisite elements of the herbal genre that English readers expected to have satisfied if they were to lay out large sums of money for what would be a massive and expensive volume.

In order to produce an illustrated herbal, Norton needed both a text and the means to produce images, and while potential English herbalists seem to have been common enough (Turner listed several qualified Englishmen in his 1551 New Herball, and the community of naturalists on Lime Street was growing), complete sets of botanical woodblocks were a much more limited resource.Footnote 9 Norton therefore may have started his project by locating the means to produce botanical illustrations, reasoning that he could source both a text and (if needed) a party to reconcile image and text together, once the woodblocks were secured. Norton’s connections to continental booksellers allowed him to acquire a large set of botanical woodblocks that had previously been used in a herbal published in Frankfurt in 1590: Nicolaus Basseus’s edition of the Eicones plantarum of Tabernaemontanus (USTC 642288). It is also possible that Norton settled on the production of a new English herbal only after being presented with an opportunity to rent the set of woodblocks sometime after Eicones appeared in print. (The blocks were later returned to Basseus, who used them for subsequent editions.) Correctly anticipating that a new, illustrated English herbal would necessarily be a sizable investment, Norton persuaded his cousin Bonham Norton to share the costs – and the risks – of financing the large publication.

At 371 edition-sheets, The Herball was the second-largest book that Bonham and John Norton would ever finance, putting it in the top 1 percent of the largest books published during the entire STC period of 1475–1640. Assuming a modest print run of only 500 copies, the paper alone for The Herball would have cost the Nortons more than £135, an expense they would have needed to bear upfront in order to enable their hired printer to start printing. The labor costs for composition and impression would be nearly as much again. The Herball’s paper volume dwarfs even the Shakespeare First Folio (227 sheets), making it comparable to folio editions of the Authorized Version of the Bible (366 sheets). Even then, however, printing the first edition of the Authorized Version in 1611 was expensive – so much so that the King’s Printer Robert Barker had to borrow money to finance it. (Incidentally, Barker reached out to the wealthiest stationers he could find: Bonham Norton and John Bill, John Norton’s former apprentice and agent in continental affairs.)Footnote 10

Publishing large books like the Bible was expensive enough, but illustrated books posed additional problems. The Herball’s large size and its thousands of woodcut illustrations meant that it was an unusually complicated book to produce, requiring production skills of the highest order. For its printing, the Nortons hired Edmund Bollifant, a partner in the syndicate of Eliot’s Court Press, thereby ensuring that the text would be accompanied not only by the botanical woodcuts Norton had rented but also by the syndicate’s impressive suite of ornamental capitals. More importantly, Bollifant was familiar with the challenges of the genre: he had recently printed an illustrated herbal of his own, a “corrected and emended” third edition of Henry Lyte’s English translation of Rembert Dodoens’s Cruydeboeck (1595; STC 6986). The Herball was such a monumental undertaking that it accounted for more than half of the Eliot’s Court Press’s output in 1596 and 1597. John Norton entered the rights to the title “sett forthe in folio and in all other volumes with pictures and without” on June 6, 1597.Footnote 11

Yet how – and when – did John Gerard get attached to John Norton’s herbal project? Most explanations of the provenance of The Herball’s textual content derive not from the evidence of the 1597 text itself but from the preface to the second edition of 1633, another “publisher-led enterprise,” published at the behest of John Norton’s widow Joyce and her business partner Richard Whitaker.Footnote 12 On its title page, Joyce Norton and Whitaker’s 1633 edition was marketed as being “very much enlarged and amended” by the London apothecary Thomas Johnson, whom Norton and Whitaker hired to carry on the accretive herbal tradition by updating Gerard’s earlier text and annotating it with his own observations. The 1633 edition was just as described: despite Johnson’s efforts to streamline the text, its bulk increased to a whopping 431 edition-sheets per copy, straining the limits of what could be bound in a single codex. (When Robert Cotes would enter the rights to John Parkinson’s Theatrum botanicum into the Stationers’ Registers two years later, he would highlight its size, calling it “an herball of a Large extent.”Footnote 13 When it was finally published in 1640, Parkinson’s book was even slightly larger than the revised Gerard, requiring 442 edition-sheets per copy.)

Johnson’s many additions and emendations in 1633 to the earlier text included a new address to the reader that was designed, in his words, to “acquaint you from what Fountaines this Knowledge may be drawne, by shewing what Authours haue deliuered to vs the Historie of Plants, and after what manner they have done it; and this will be a meanes that many controuersies may be the more easily vnderstood by the lesse learned and judicious Reader.”Footnote 14 Johnson’s musings on the history of botanical study begin with King Solomon and pass through a variety of classical authors including Aristotle, Galen, and “The Arabians” before turning to more recent authors like Ruel, Brunfels, and Fuchs, whose publications he lists by both date and format. Johnson’s survey offers a useful expression of the breadth of botanical books, many published only on the continent, that were available to an urban professional in London in the 1630s, thereby confirming what Leah Knight calls “the bookishness of early modern botanical culture.”Footnote 15 Like Turner, Johnson evaluates the work of his predecessors: authors are praised for their innovations, but he also occasionally offers reproofs for errors or for deceitful practice. Both Mattioli and Amatus Lusitanus are found wanting, “for as the one deceiued the world with counterfeit figures, so the other by feined cures to strengthen his opinion.”Footnote 16 When he comes to Tabernaemontanus, Johnson notes that the woodcuts used in his book were “these same Figures was this Worke of our Author [i.e., Gerard] formerly printed.”Footnote 17

Upon arriving at Gerard, Johnson’s comprehensive botanical history slows to include a brief biography of the authoritative figure whom Johnson’s editorial efforts are designed to serve. Yet, when approaching the more recent history of Gerard’s life, Johnson becomes less careful. He claims that Gerard died in 1607, “some ten years after the publishing of this worke,” when Gerard actually lived until 1612 and continued to be a figure of considerable status in the Barber-Surgeon’s Company after his term as Master in 1607. As Johnson was an apothecary, his lack of familiarity with the history of the Barber-Surgeons is understandable, but his biography of Gerard reveals that tensions among London’s three types of authorized medical practitioners of physicians, surgeons, and apothecaries also carried over into the herbals of the seventeenth century. After the Society of Apothecaries had finally broken free of the powerful Grocers’ Company in 1617 only with the assistance of the Royal College of Physicians, the Apothecaries’ professional loyalties were clear, and evidence of them can be seen in Johnson’s attitudes towards the barber-surgeon Gerard. Johnson commends Gerard’s efforts in extending herbal knowledge on behalf of the nation but finds his expertise wanting: “His chiefe commendation is, that he out of a propense good will to the publique aduancement of this knowledge, endeauoured to perfome therein more than he would well accomplish; which was partly through want of sufficient learning.”Footnote 18 Just as the physician Turner suggested that contemporary apothecaries were ignorant of their subjects, so does the apothecary Johnson suggest that the barber-surgeon Gerard lacked a proper education. He criticizes Gerard for being insufficiently “conuersant in the writings of the Antients,” and takes Gerard to task for having “diuided the titles of honour from the name of the person whereto they did belong,” errors that might better be ascribed to one of Bollifant’s compositors than to the text’s author.Footnote 19 That Johnson’s indignation finds its source in professional jealousy soon becomes clearer as Johnson explains that his caviling was prompted by Gerard’s Herball having generated a fame outstripping what Johnson feels is deserved: “I haue met with some that haue too much admired him, as the only learned and iudicious writer.”Footnote 20 In the three decades since its publication, Gerard’s massive Herball had dominated English herbalism, blocking other herbalists from view. For Johnson, then, Gerard’s Herball met with its success because it proved insufficiently intertextual, misleading the “lesse learned and judicious” readers that he addresses in his own preface. By the end of the address, Johnson’s narrative of the herbal genre may be read retrospectively, when it becomes less an informative chronicle than a defensive intertextual correction designed to remedy what he sees as Gerard’s profound anthological failure. For all Renaissance botanists, including Johnson, the solution to a problematic book was always another book.

Johnson’s indignant professional position also helps to explain what comes next, an account of Gerard’s authorship of The Herball that builds on these earlier charges of insufficient learning by charging Gerard with the more serious accusation of plagiarism. In their discussions of plagiarism, Christopher Ricks and Peter Shaw have maintained that the offense doesn’t consist merely in using the work of another author but in doing so “with the intent to deceive.”Footnote 21 While copying another’s work for one’s own use is widely acceptable in the early modern practice of commonplacing, allowing for the publication of such work as one’s own deceives readers who might be unable to locate their original source.Footnote 22 In this way, plagiarism is distinguished from more acceptable uses of others’ work such as quotation, imitation, repetition, and allusion, all of which are, by virtue of the accuracy of their attribution, ethically acceptable. The offense of plagiarism is thus a moral one, an attempt at dishonesty. As we saw in Chapter 1, herbalists and physicians writing for print publication had long accused each other of illicit copying – such accounts regularly appear in the pages of Fuchs and the other herbalists that Johnson mentions as they updated old works. Despite (or perhaps because of) the humanist Republic of Letters that saw naturalists sharing samples, woodcut images, and plant descriptions throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the field of herbalism also saw incidents of acrimony, accusations, and disdain.Footnote 23 Some herbalists, like Mattioli and L’Obel, were notoriously embittered by other naturalists’ success, itemizing their failures and finding fault with any work that inadequately commended their own. Calling out contemporaries for their insufficient citation and acknowledgment was thus wholly conventional in herbals, especially by the early 1630s, when Johnson was invited by Norton and Whitaker to edit Gerard’s Herball. His indignation is at once opportune (provided by the occasion of a new reprint of an old edition) and entirely orthodox.

In his account of “how this Work was made vp,” Johnson carries on herbals’ tradition of paratextual recrimination by asserting that Gerard’s 1597 text derived from a lost translation of Rembert Dodoens’s Stirpium historiae pemptades sex (USTC 401987) that had been begun by a “Dr Priest,” probably Robert Priest, then a member of the College of Physicians of London. Dodoens’s Pemptades had been published in Antwerp by Christopher Plantin in 1583 and Johnson reports that “shortly after” Priest had been hired to translate the work from Latin into English “at the charges of Mr. Norton,”Footnote 24 confirming that the creation of what later became known as “Gerard’s Herball” was prompted not by an originating author but by an originating stationer. Though Johnson’s goal with this summary is to undermine Gerard’s authority, the story that Johnson tells of The Herball’s provenance is the tale of how an expensive and specialized edition of a book eventually came to be produced. Priest, however, died “either immediately before or after the finishing of this translation,” and Priest’s manuscript translation of Pemptades then found its way into Gerard’s hands, according to an unnamed someone “who knew Dr. Priest and Mr. Gerard.”Footnote 25

What was eventually published in 1597 as The Herball was ultimately not just a translation of Dodoens but a much larger, and decidedly more English, volume. Gerard drew on his extensive knowledge of English flora as well as his firsthand knowledge of how exotic foreign plants would fare when transported into the English climate. Johnson explains this discrepancy between Dodoens’s and Gerard’s texts by noting that Gerard reorganized his volume to fit the botanist Matthias de L’Obel’s new system of classification that ordered plants not by pharmacological use value but by their morphological characteristics. In Gerard’s Herball, plants are grouped together according to their kinds, enabling readers to examine what makes one species of basil or wolfsbane distinct from another. Johnson claims that Gerard’s primary goal in adopting L’Obel’s classification scheme was to disguise evidence of his use of Priest’s translation: “Now this translation became the ground-worke whereupon Mr. Gerard built vp this Worke: but that it might not appeare a translation, he changes the generall method of Dodonaeus, into that of Lobel, and therein almost all ouer followes his Icones both in method and names, as you may plainly see in the Grasses and Orchides.”Footnote 26 Johnson’s moral position is clear and damning: “I cannot commend my Author for endeauouring to hide this thing from us.”Footnote 27

Johnson’s indignation on Priest’s behalf is largely baseless. Gerard could read (and write) in Latin, and he could easily have accessed Dodoens’s Pemptades without Priest’s intervention simply by acquiring a copy of Plantin’s 1583 edition. What’s more, as Robert Jeffers has noted, Gerard’s Herball included not only those plants suitable for medical use but also those with culinary and aesthetic applications as well as new exotics, and as a result, “Dodoens’ classifications would not have answered his purpose fully.”Footnote 28 Further, because Gerard was taking his own botanical notes through the 1570s, his organizational structure would have been determined long before Pemptades was first published, and it reasonably bears evidence of influence from Pena and L’Obel’s Stirpium aduerseria noua (1570–1571; STC 19595).Footnote 29 As Gerard approached the task of reconfiguring his work to suit Norton’s commission, he continued to use the classification method with which he was most familiar. Gerard’s use of L’Obel’s method of organizing his subject matter had little to do with Priest’s translation of Dodoens, but because Johnson’s goal is less to defend Priest than to demonstrate Gerard’s inadequacy as a herbalist and as a botanist, his critique rests in finding fault with Gerard’s technical capacity. Johnson suggests that Gerard was stymied by the woodblocks Norton presented him:

this fell crosse for my Author, who (as it seemes) hauing no great iudgement in them, frequently put one for another … and by this means so confounded all, that none could possibly haue set them right, vnlesse they knew this occasion of these errors. By this means, and after this manner was the Worke of my Author made vp, which was printed at the charges of Mr. Norton, An. 1597.Footnote 30

While Johnson’s account of Gerard’s matching woodblocks with the wrong descriptions seems damning, these kinds of errors are as likely to result from a compositor’s mistakes in a print shop, as occurred with Peter Treveris’s accidental swapping of the woodblocks for bombax and borage that I discussed in Chapter 5.

A verification for Johnson’s account appears to come from a book published in 1655, an edited collection of L’Obel’s writings from a manuscript written shortly before L’Obel’s death in 1616. In Stirpium illustrations, L’Obel claimed that Gerard had used his work without proper acknowledgment, and he reports that he had been hired by Norton to edit Gerard’s manuscript once its inadequacies had become apparent. L’Obel and Gerard had at one time been friendly, and L’Obel had even lent his name to Gerard’s writings, providing a substantial commendatory letter for the 1597 Herball. Shortly before The Herball was finished printing, however, Gerard and L’Obel had fallen out, and L’Obel’s grudge against Gerard continued for the remainder of his life. If Johnson’s account of the making of the original volume is correct, then L’Obel’s story of Gerard’s failures provides additional verification for the charges of plagiarism that were leveled against Gerard. Yet there is little reason to trust L’Obel, and his biographer, Armand Louis, is not convinced that his account of editing Gerard is true. Louis notes there are no contemporary reports testifying to L’Obel’s version of the events, adding that the botanist, particularly in his old age, was often cantankerous. “It is not impossible,” Louis surmises, “that L’Obel’s concerns and accusations were merely the ruminations of a rancorous and embittered old man who felt threatened by others’ authoritative rise in his dearly-loved field.”Footnote 31

Bookish details in L’Obel’s biography put additional strain on his veracity and help to explain his animus. A Flemish physician, L’Obel had first come to London as a Protestant refugee in the late 1560s, when he settled in the Flemish hub of Lime Street. In 1570–1571, L’Obel and Pena collaborated to produce Stirpium aduersaria noua, which was entered by Thomas Purfoot into the Stationers’ Registers and later printed. Even though Purfoot obtained the license to print Stirpium, it was L’Obel who appears to have funded its publication. In 1603, the Flemish author wrote a letter complaining that, of the original print run of 3,000 copies, he still had 2,050 remaining.Footnote 32 That print run was double what the Stationers’ Company would eventually set as the maximum for a single edition, and at 120 edition-sheets, the expense for L’Obel must have been enormous.Footnote 33 “Thank God it is all paid for,” L’Obel explained to L’Ecluse, “but the booksellers haven’t allowed it to make a profit.” By 1576, Purfoot had sold 800 copies of Stirpium to Plantin to bind with copies of Plantin’s edition of L’Obel’s Plantarum seu stirpium historia (STC 19595.3), a deal that also included Plantin acquiring the set of botanical woodblocks that Purfoot had used in printing his London edition.Footnote 34 Outside of the bulk sale to Plantin, Pena and L’Obel’s Stirpium aduersaria noua sold exceptionally poorly, with only about 150 copies being purchased over three decades.Footnote 35 What appears to have happened is that Pena and L’Obel, recent immigrants, radically misjudged the English marketplace for herbals when they paid to publish their own work in its original Latin rather than translating it. Familiar with the bestselling herbals of Fuchs and Mattioli on the continent, the pair overestimated the audience in England for an expensive Latin herbal, as well as interest on the continent for a Latin herbal that had been printed in London and dedicated to a Protestant queen. Writing reflectively at the end of his life, L’Obel was thus motivated as much by the failure of his Latin herbal to find readers (a failure he blamed on English booksellers), and his jealousy of Norton’s support for Gerard, as he was by Gerard’s textual malfeasance.Footnote 36

Johnson’s and L’Obel’s case for Gerard’s plagiarism has been picked up by historians and oft repeated, but Johnson’s evidence for vilifying Gerard breaks down even in the telling.Footnote 37 As Johnson reports it, the book that became Gerard’s Herball began not with Gerard at all but with a publisher’s recognition of an opportunity to profit: “Mr. Norton,” surveying what Christopher Plantin was doing on the continent, saw room in the marketplace for an English translation of Dodoens’s Pemptades and sought to commission one.Footnote 38 Recognizing that successful printed herbals are illustrated, Norton also acquired a large sequence of woodblocks. These blocks corresponded to the text of a different herbal, but it seems clear that Norton reasoned he could hire someone to reconcile Tabernaemontanus’s images with Dodoens’s text. The anthological impulse of the early modern herbal can thus be found not simply in the textual “gathering” of the authors so identified on these books’ title pages but also in the material efforts of the publishers who assembled their herbal commodities from parts.Footnote 39 This facet of herbals’ material forms is revealing: if Johnson’s unnamed informant was accurate, and John Norton actually did commission a translation of Dodoens from Priest, the stationer owned the rights to use that text in whatever form he chose thereafter – which included handing off the manuscript to someone else once Priest was unable to finish it. Stephen Bredwell, one of Gerard’s commendatory verse writers in 1597, suggests that exactly such a thing happened:

The first gatherers out of the Antients, and augmentors by their owne paines, haue alreadie spread the odour of their good names, through all the Lands of learned habitations. D. Priest, for his translation of so much as Dodonæus, hath thereby left a tombe for his honourable sepulture. M. Gerard coming last, but not the least, hath many waies accommodated the whole work vnto our English nation.Footnote 40

In saying that Gerard “accommodated” those who came before him, Bredwell not only recognizes Gerard’s anthological “gathering” efforts but endorses them, celebrating Gerard’s synthesis in the volume’s new English presentation. In other words, the “commonwealth thinking” of William Turner was recognized and celebrated when it reappeared in the writings of his native successor.

Thus, with Priest’s death and inability to finish his translation, John Norton had a problem, but it was one that was solved by a bookseller with a talent for figuring out what a public would buy. His choice to deploy Gerard as his herbal’s authorial figure was a smart one: while Priest was relatively unknown, Gerard in the 1590s was a gardener of some celebrity. He had been superintendent to the gardens of Sir William Cecil, Baron Burleigh, at Burleigh’s residences in the Strand and at Hertfordshire since 1577, filling the void for botanical patronage in Cecil’s service following the death of William Turner in 1568. In addition to tending Burleigh’s gardens, Gerard had a large garden of his own in Holborn near the River Fleet. He was of such renown that in 1586 he was appointed curator of the garden of the College of Physicians, which would otherwise have had no reason to grant such authority to a mere barber-surgeon. Through his associations with Cecil, Gerard gained many advantages, including access to the latest plant specimens from the Americas and status in the growing botanical scene of Renaissance Europe, acquainting him with the leading physicians, scientists, and botanists visiting London and the Court. In 1597, Gerard was appointed Warden of the Barber-Surgeons’ Company, and after the publication of The Herball, his status in London only continued to increase: by August 1604, Gerard had been appointed surgeon and herbalist to James I, and he was elected Master of the Barber-Surgeons’ Company on August 17, 1607.Footnote 41 Historical accounts from a variety of sources reveal that, unlike Priest, Gerard’s fame and influence were significant enough in late Elizabethan London to have sold books on its own. In short, there is a clear rationale why a savvy stationer like Norton would have wanted Gerard’s name on a book he produced. Gerard’s biographer, Robert Jeffers, suggests that he had been working on a herbal project throughout his career as a surgeon, and Norton’s offer would have been a welcome opportunity to “accommodate” that manuscript into an expanded and revised form.Footnote 42

In his own address to the reader, dated December 1, 1597, Gerard made the form, and the anthological nature, of his work clear. He writes,

I haue here therefore set downe not onely the names of sundry Plants, but also their natures, their proportions and properties, their affects and effects, their increase and decrease, their flourishing and fading, their distinct varieties and seuerall qualities, as well of those which our owne Countrey yeeldeth, as of others which I haue fetched further, or drawene out by perusing diuers Herbals set forth in other languages, wherein none of my country-men hath to my knowledge taken any paines, since that excellent Worke of Master Doctor Turner.Footnote 43

In admitting to “perusing diuers Herbals,” Gerard both echoes and cites his English forebear William Turner, who admitted to having “learned and gathered of manye good autoures” in the writing of his own book.Footnote 44 Turner’s defense, as I and others have noted, relies on the breadth and diversity of his gathering, as well as on the way that Turner justifies this synthesis as being for the good of the English nation. It is not surprising, then, that Gerard’s account continues by specifically focusing on his fellow “country-men” who have contributed to the herbal genre: “After which time Master Lyte a Worshipfull Gentleman translated Dodonaeus out of French into English: and since that, Doctor Priest, one of our London Colledge, hath (as I heard) translated the last Edition of Dodonaeus, and meant to publish the same; but being preuented by death, his translation likewise perished.”Footnote 45 Missing from this account is Pena and L’Obel, whose status as foreign nationals residing within England rendered their contributions to English botany unworthy of inclusion in this particular list. Gerard’s account of English-language herbals written by Englishmen, then, is in keeping both with the extant evidence and with what John Norton saw in the marketplace before commissioning the book that bears Gerard’s name and advertises his status as a high-ranking Londoner on its title page.Footnote 46

Gerard’s book is, like the herbals that came before it, inherently intertextual, drawing from its predecessors and, in turn, providing its successors with ample opportunities for allusion, borrowing, and correction. In using Gerard’s Herball as a guide for his botanical exegesis, John Milton was following in the footsteps of other authors; decades earlier, in his Poly-olbion (1612), Michael Drayton had identified the author as “skilful Gerard.”Footnote 47 Editions of Gerard or quotations taken from them appear in the libraries of John Donne, Anne Southwell, Elizabeth Freke, and Lady Anne Clifford, among many others.Footnote 48 Gerard’s reputation also continued through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries: the works of John Coakley and Sir Joseph Banks testify that Gerard’s Herball in its various editions continued to be of use in their own naturalist studies. Gerard’s Herball remained a reference text to students of botany through the nineteenth century; as late as 1806, Richard Weston noted that “[a]t this day the book is held in high esteem, particularly by those who are fond of searching into the medicinal virtues of plants.”Footnote 49 Descriptions of copies held in rare book libraries throughout the world suggest that many copies of Gerard’s Herball saw heavy use, bearing evidence of plants being pressed between their pages.

Yet the intertextuality of The Herball that makes it so valuable is not restricted to its verbal and illustrative botanical content; it can also be seen in the volume’s organizational form and structure. The Herball’s detailed indexes indicate that the book was especially suited for use as a reference text, and the indexes’ interconnectivity suggests that Gerard (and his publisher) depended upon readers’ familiarity with similar finding aids from works such as Gibson’s edition of The Grete Herball of 1539 and Wyer’s innovative later editions of the little Herball.Footnote 50 Plants were listed in Gerard’s Herball by their proper names in both English and Latin, and each entry was keyed to a page reference; other indexes were organized according to the illnesses or injuries that simples distilled from the listed plants could treat or provided equivalency tables uniting proper names with their local or regional monikers. English readers of herbals had been familiar with these tables for some time, but The Herball’s indexes were so comprehensive that the book could be useful for both those searching for medical remedies and those who were interested in plants for their own sake. Whether they were Gerard’s innovation or, more likely, Norton’s, the indexes ensured that The Herball could serve a variety of readers. Gerard’s massive and comprehensive tome was considered so useful to Stuart medical practitioners that it was specifically bequeathed in a surgeon’s will of 1628, which offered to “George Peren, barber-surgeon, my yearball known by the name of ‘Gerard’s Yearball.’”Footnote 51 As a result of the book’s extended value for Renaissance readers, editors of early modern texts still consider Gerard’s Herball a valuable resource in explaining contemporary botanical knowledge, and for this reason the volume is cited regularly in the commendatory notes of Shakespeare’s plays where botanical elements play a significant role.Footnote 52

Johnson was correct that his author’s book in 1597 had actually been initiated by its publisher, but he seemed less willing to acknowledge that he, too, in 1632, had been subjected to the same commercial bibliographic impulses. Though Johnson complains to his readers that he was forced to work quickly, he tries to obscure who the commissioning agent was that set the clock ticking: “But I thinke I shall best satisfie you if I briefely specifie what is done in each particular, hauing first acquainted you with what my generall intention was: I determined, as wel as the shortnesse of my time would giue me leaue, to reetaine and set forth whatsoeuer was formerly in the booke described, or figured without descriptions.”Footnote 53 As he lists his numerous mechanisms for “enlarging” and “amending” the 1597 Herball, Johnson positions himself as an authoritative and active subject, even though the book he corrects does not actually recognize him as its author. An inattentive reader might be forgiven for thinking that it was Johnson’s initiative alone that necessitated Gerard’s text being updated and reprinted for sale in 1630s London.

Yet, of course, in commercial terms, it wasn’t really Johnson’s project at all. The impetus for the creation of the second edition of The Herball was its publishers, and it derived from their noticing the appearance of a competing English volume: John Parkinson’s Paradisi in sole paradisus terrestris. Or A Garden of all sorts of pleasant flowers which our English ayre will permit to be noursed vp: with A Kitchen garden of all manner of herbes, rootes, & fruites, for meate or sause vsed with vs, and An an Orchard of all sorte of fruit-bearing Trees and shrubbes fit for our Land together With the right ordering planting & preseruing of them and their vses & vertues (1629, STC 19300). Though Parkinson’s book did not list plants’ medical virtues and was not technically a herbal but a horticultural treatise, Paradisi borrowed many of the genre’s elements in its account of English kitchen gardens, floral gardens, and orchards.Footnote 54 Moreover, Parkinson’s composition of Paradisi was, as is traditional with herbals, anthological and derived from his perusing the work of others, particularly the herbals of his fellow Englishmen. Having surveyed the bibliographic field, Parkinson found space for his elevation of flowers because the topic had been little approached:

In English likewise we haue some extant, as Turner and Dodonaeus translated, who have said little of Flowers, Gerard who is last, hath no doubt giuen vs the knowledge of as many as he attained vnto in his time, but since his dates we haue had many more varieties, then he or they euer heard of, as may be perceived by the store I haue here produced.Footnote 55

To stationers like Joyce Norton and Richard Whitaker, who happened to hold the rights to copy Gerard’s text, Parkinson’s Paradisi was a wake-up call that a market for English herbals not only continued to exist but needed an update;Footnote 56 and Parkinson himself promised soon to provide one:

I haue beene in some places more copious and ample then at the first I had intended, the occasion drawing on my desire to informe others with what I thought was fit to be known, reseruing what else might be said to another time & worke; wherein (God willing) I will inlarge my selfe, the subiect matter requiring it at my hands, in what my small ability can effect.Footnote 57

Recreating what her late husband had done over three decades earlier, Joyce Norton and her business partner Richard Whitaker sprang into action. The first thing they needed was a set of botanical woodblocks, and Whitaker knew just where to turn. By the 1630s, the Plantin Press in Antwerp had assembled a comprehensive collection of botanical woodblocks that numbered in the thousands. In 1632, Christopher Plantin’s grandson, Balthasar Moretus I, managed the shop and Whitaker turned to Moretus to supply the woodblocks that were needed to reprint an edition of Gerard’s Herball.Footnote 58 Whitaker requested the blocks in July of 1632 and, a month later, they were on their way to England. Another set followed in September. All told, Norton and Whitaker rented almost 3,000 woodcuts, comprising images that had appeared in the most recent works of Dodoens, L’Obel, and Carolus Clusius. These found their way to Johnson: “Now come I to particulars, and first of figures: I haue, as I said, made vse of those wherewith the Workes of Dodonaeus, Lobel, and Clusius were formerly printed, which, though some of them be not so sightly, yet are they generally as truly exprest, and sometimes more.”Footnote 59 Yet time, the bane of Johnson’s editorial efforts, was of the essence, as Moretus wanted his blocks back as soon as possible, for without them he could not publish any new botanical treatises at all, and his printing house was in high demand. Both in England and in continental Europe, the technical and financial constraints upon publishers and printers limited the activities of authors and authorial figures like Thomas Johnson.

Johnson did work very, very quickly: his letter to the reader is dated October 22, 1633, and it must have been written after most of the volume had been printed by Adam Islip, who may also have shared in the publication costs of the edition. In just over a year, Norton and Whitaker had commissioned and produced a formidable tome that enabled them to continue to profit from Gerard’s name and reputation while simultaneously offering for sale the latest and best botanical images offered anywhere in Europe (Figure 8.2). Their investment paid off: the 1633 edition sold well and sold fast – so much so that, despite an increasingly irate sequence of letters from Moretus desperate for the return of his woodblocks, Norton, Whitaker, and Islip kept them long enough to reprint another revised edition of the herbal in 1636 (STC 11752).Footnote 60 Extremely protective of their investment, Norton, Whitaker, and Islip even went so far as to petition King Charles to have their work protected by royal decree, lest anyone try to publish an epitomized, or shortened, version of it. On March 1, 1633, a letter was brought to the Stationers’ Company wardens from the king “that none pr[e]sume to imprint any Abridgment or Abstract of their Copie called Gerards Herball.”Footnote 61 For forty years after its initial publication, Gerard’s Herball dominated the marketplace for English herbals thanks not to the efforts of its putative author but because of the strategic maneuvering of its publishers.

Figure 8.2 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie of Plants (1633).

Redefining Textual Authority

As I have shown, Gerard’s agency had little to do in organizing the publication of the book that bears his name, though his efforts to gather and to supplement what became The Herball’s text were central to its success. What is curious about the censure of Gerard in botanical histories is the singling out of this early modern botanist above all others as guilty of the complex and anachronistic crime of plagiarism. The previous chapters of this book reveal that the majority of sixteenth-century English herbalists and publishers of herbals drew material from the works of their predecessors, taking what information they thought relevant and discarding or dismissing the rest; furthermore, especially in the case of the accompanying woodcut illustrations, copying was the norm rather than the exception. Stationers, acutely aware of competition from other publishers, sought to differentiate their texts by adding the name of an established authority or supplemental material based upon an editor’s personal experience. Later, stationers added detailed indexes to their herbals to make their texts more user-friendly, simultaneously justifying the higher costs of their illustrated editions by suggesting that owners of their texts would be able to self-medicate and no longer require the services of physicians and apothecaries. An examination of herbal literature printed in England between the little Herball of 1525 and the publication of Gerard’s Herball in 1597 indicates that, rather than being guilty of plagiarism, Gerard was writing and compiling his text in accordance with the norms and customs of printing herbals in England during the Tudor period.

It is evident from examining the printing history of early modern herbals that not only were woodcut illustrations and paratextual materials borrowed and copied from one botanical text to another but the written works of earlier herbalists provided a starting point for later ones. In some cases, herbals began as translations of an earlier work in a different language, but a translator’s incorporation of their own commentary into the text was in keeping with the anthological approach to botanical study that had begun with the German Herbarius of 1485. Thus sixteenth-century English herbals became more collaborative as the century progressed – not only were herbalists directly referencing each other but they were often aiding each other’s publications by trading illustrations and plant specimens.Footnote 62 Alternatively, they were also denigrating each other’s work and citing multiple inaccuracies in order to justify their own updated or corrected works. A modern scholar of herbal literature of this period can view this conflation of texts either as an incidence of mass plagiarism and unscrupulous scientific citation or as evidence of a rapidly developing science practiced by an expanding circle of recognized experts who circulated their work in print.Footnote 63 By the time Gerard entered the botanical scene at the end of the century, more than half a dozen large volumes of plant lore had been on the market for decades. Expecting Gerard to author a completely original text in such an environment would be unreasonable, and, as John Norton and later Joyce Norton knew, publishing such a wholly original work would likely have been unprofitable.

Most of the sixteenth-century herbalists in England and on the continent took material from the works of their predecessors to confirm or to refute their own observations. As the Frankfurt printer Christian Egenolff pointed out in his disputes with Johannes Schott and Leonhart Fuchs in the 1530s and 1540s, this borrowing is reasonable: there is a limit to the originality that natural historians can claim in their accounts of God-created nature. Copying was the norm rather than the exception as early botanists sought to organize the rapidly increasing printed information available about plants into a comprehensive system. While they circulated through the channels of the book trade, herbals were locations for plant investigators to publish theories that could later be assessed by fellow and competing botanists in their own herbal publications – and to do this they needed to quote, borrow, and build upon each other’s work.

Yet botanists did not use herbals only as occasions for disagreements about the particulars of plant characteristics and classifications. Because plants are by their nature rooted in place, a comprehensive understanding of them across ecosystems was necessarily dependent on an observer’s ability to travel to gather specimens. One reason for the infamous tulip craze in Europe in the seventeenth century was the bulbs’ capacity for traveling very long distances while suffering little damage. Tulip bulbs are easily transported, while other plants are more firmly rooted in their geographies: it is more difficult to bring a tree or a shrub from overseas and guarantee its survival in transit, let alone nurture it through its lifespan in a hostile new climate. Herbalists like Gerard therefore itemized the exotic plants that they could raise in their gardens to demonstrate what plants could survive the London winters.Footnote 64 Herbals authored in other regions could solve the problem of geographical deficiency for landlocked botanists by enabling them to acquire information about species that were outside of their own climates of reference. One of The Herball’s commendatory letter writers, the surgeon Thomas Thorney, notes that, by bringing his private expertise into the public sphere, Gerard’s Herball makes his work a public service. Thorney celebrates the ways that the work is a representation of Gerard’s Holborn garden, but Thorney also hints that books make plants accessible to those who cannot travel to them:

Thorney’s advocacy for Gerard celebrates both Gerard’s book learning and his hands-on botanical experience, but his poem also suggests that books themselves serve the needs of readers by bringing the outside indoors. The mechanical process of illustrative and textual reproduction extends the reach of a single plant specimen and individually prolongs the life of an individual flower. The celebration of “well-cut” herbals prescribed by Robert Burton in 1621 thus finds its seed in the preliminaries of earlier illustrated works. Yet the capacity for herbals to serve as surrogates for visits to local places also led to their adaptation in the service of colonial enterprise. As Christopher M. Parsons has shown, the description of plants in the travel accounts authored by American explorers embedded travelogue readers in landscapes that allowed them to imagine inhabiting and settling such spaces themselves.Footnote 66 It is not difficult to see how both the content and the forms of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century herbals could later serve the imperial needs of eighteenth-century colonial botany.

For his part, Gerard knew that his anthological labor was by no means finished. In his dedication to Cecil, Gerard explains that, through his participation in the collaborative effort of Renaissance botany, he expects others to find errors in his opus. He insists that by gathering together the text he has “ministered matter for riper wits, and men of deeper iudgment to polish; and to adde to my large additions where any thing is defectiue, that in time the worke may be perfect.”Footnote 67 Gerard repeats these sentiments later in his address to his readers; he has presented “a worke, I confesse, for greater clerks to vndertake, yet may my blunt attempt serue as a whetstone to set and edge vpon some sharper wits, by whome I wish this my course discourse might be both fined and refined.”Footnote 68 Since 1633, John Gerard has endured little from history but scorn. His “course discourse” was not perfect, and the anthological means by which it came to be is no longer fashionable. Yet was John Gerard a thief, a plagiarist? Time and botanical scholarship have often told us so; but more time and more investigation into the agents who made and sold herbals in early modern London seem to tell us otherwise.

Gerard’s later status as an “authoritative English herbalist” was not simply the result of Gerard’s own activity; it was a marketing strategy first produced by John Norton in 1597 that was later reinforced by Joyce Norton and Richard Whitaker in 1633 and 1636. The famous gardener would soon be Master of the company of Barber-Surgeons and he was known to many at court through his service to William Cecil – putting Gerard’s name on a book about plants in 1597 was simply good business. Recognizing the preeminence of stationers in the production of English herbals helps scholars recognize the ways that scientific authorship and scientific expertise were necessarily limited by commercial concerns. Before botanists could emerge to “authorize” herbals, the genre first needed to become a vendible print commodity. Early anonymous works like the little Herball and The Grete Herball demonstrated to printers and booksellers that they could make money manufacturing books about plants in the English vernacular; and as the reading public grew and demand for these texts increased, medical practitioners like physicians soon realized that print offered them a venue for professional advancement. By asserting their authority over this new genre of the printed English herbal, physicians like Thomas Gibson and William Turner could likewise proclaim their authority over the professional sphere of vernacular healing, mimicking the ways that print was used to encourage Protestant reform. The decisions that John Norton made when he chose to publish a new English herbal in 1597 show that he was fully cognizant of the genre’s history and that he recognized what could make these books so popular and so profitable. Thirty years later, when preparing Gerard’s Herball for its second edition, Joyce Norton and Richard Whitaker recognized that professional apothecaries like Thomas Johnson and John Parkinson also had a vested interest in promoting and authorizing the herbal genre. Attending to the “stationer-function” therefore helps to demonstrate how herbal authors devised their texts in response to printers’ and booksellers’ material and financial concerns. It was through the commodification of English herbals as occasions and locations for botanical knowledge that the “fathers of English botany” became authorized experts.