As we saw in Chapter 1, the historical and institutional development of Hieradoumia in the late Hellenistic and early Roman imperial periods was in many ways unlike that of other parts of inland western Asia Minor. Large-scale migration into the region in the later Hellenistic period created an ethnically and culturally mixed society, in which it is effectively impossible to distinguish ‘indigenous’ Lydian and Phrygian elements from ‘imported’ Greek, Macedonian, and Mysian cultural forms. As a result of the settlement policies of the Seleukid and Attalid kings, urbanism in the region during the Hellenistic period was minimal, in terms both of settlement agglomeration and polis-institutions; instead, the late Hellenistic koina of the region (the Mysoi Abbaitai; the Maionians in the Katakekaumene) seems to have served as a functional alternative to organization by poleis. The scattered villages of the region were, eventually, lumped together into poleis, but this development was (or so I will argue in Chapter 10) late and marginal. The result of this combination of trajectories, by the turn of the era, was a region which possessed a highly distinctive shared culture, but lacked a strong focus of collective identity.

Nonetheless, the strongest argument for treating Roman Hieradoumia as a distinct and meaningful culture zone is not the region’s particular historical and institutional development between, say, 200 BC and AD 200. It is, instead, a case based on material culture – more specifically, the emergence in this region of two highly idiosyncratic and instantly recognizable local commemorative practices, the familial epitaph and the propitiation-stēlē. It is almost entirely from these two categories of epigraphic monument that our knowledge of the social structure of Hieradoumia derives. The aim of the present chapter is to introduce these two categories of monument, to describe their distribution in time and space, and to indicate some of the ways in which they can be used to reconstruct the particular statics and dynamics of Hieradoumian society. As we will see, although the two kinds of monument were set up in different places and to very different ends, they in fact bear close resemblances in both physical appearance and – more surprisingly – in textual content.Footnote 1 As these formal similarities suggest, both commemorative practices should be seen as ways of expressing a single distinctive Hieradoumian cultural ‘outlook’ on the world. In Alois Riegl’s famously knotty formulation, they are different facets of a single Kunstwollen or ‘artistic volition’ – the expression in diverse artistic and textual genres of a single distinct worldview, specific to a particular place and time.Footnote 2

It is, of course, hardly surprising that the inscribed monuments of one region look different from those of another region. Microregional diversity in epigraphic practice (particularly the funerary sphere) is characteristic of much of the ancient Greek world, both at the level of the individual city and its territory, and at the level of cultural regions as a whole; inner Anatolia is no exception.Footnote 3 Nonetheless, the geographic clarity and definition of the Hieradoumian ‘material culture zone’ is striking and significant, and it maps with satisfying precision onto that stretch of the middle Hermos valley which underwent the peculiar pattern of historical and institutional development described above. As I will argue throughout this book, there is good reason to think that the distinctive Kunstwollen of the rural communities of the middle Hermos valley, as expressed in their two chief commemorative cultures, may reflect real differences between the social structure of this region and other parts of inland western Asia Minor. If so, that is perhaps rather exciting, and might even be methodologically consequential.

2.1 Familial Epitaphs in Roman Hieradoumia: Overview

Between the first and third century AD, the men and women of Hieradoumia regularly commemorated their dead with a highly distinctive local type of epitaph. Here is a characteristic example, from a village on the territory of Saittai, dated to early AD 167:Footnote 4

Year 251, Day 18 of the month Dystros. Herakleides, son of Herakleides, and Fl(avia) Sophrone (honoured) Sophrone their daughter, and Eudoxos her husband (honoured her), and Demophilos and Nysa her husband’s parents, and Herakleides her son, and Demophilos her husband’s brother, and all her own people (idioi) honoured her, having lived for 26 years.

Figure 2.1 Epitaph of Sophrone, from Hacı Hüseyn Damları. TAM V 1, 175.

Around a thousand epitaphs of this basic type are known, almost all of them dating between the mid-first and the mid-third century AD.Footnote 5 The ‘Hieradoumian’ epitaph type is characterized by four distinctive features:

(1) Physical form and decoration. The monuments typically take the form of a thin trapezoidal marble stēlē tapering towards the top, terminating in a triangular pediment with akroteria, with a rough tenon below for fixing to the ground. The upper part of the shaft generally carries a depiction of a vegetal wreath, incised or in low inset relief, either above the inscribed text or – as in the example depicted in Figure 2.1 – between the date and the remainder of the text. In a minority of cases, instead of a wreath, the upper part of the shaft bears a sculptural depiction of the deceased (who may be accompanied by one or more other figures), either in a recessed niche or in low relief projecting forward from the face of the shaft.

(2) Date and age. The overwhelming majority of epitaphs either begin or conclude with a date in the form Year – Month – Day (more rarely, Year – Month, or Year alone), indicating – as we will see shortly – date of death. Age at death is indicated in around 30 per cent of cases, as in the example quoted here.Footnote 6

(3) Grammatical structure. The name of the deceased is invariably given in the accusative case, followed or preceded by the name(s) of at least one commemorator, always in the nominative. The act of commemoration is almost always indicated by means of the verb τ(ε)ιμᾶν, ‘to honour’, in the aorist tense (ἐτείμησεν in the singular, ἐτείμησαν in the plural). We very occasionally find other verbs used, such as στεφανοῦν, ‘wreathe’, μνησθῆναι, ‘commemorate’ (with the genitive), or καθιερῶσαι, ‘consecrate’.Footnote 7 The verb is sometimes omitted, leaving a simple ‘accusative of the deceased’ and ‘nominative(s) of the honourer(s)’.

(4) Familial commemoration. Most epitaphs feature a more or less extended list (in the nominative case) of the relatives who joined in commemorating the deceased, most commonly consisting of around four to six persons, but sometimes running into the dozens. These relatives are sometimes accompanied by acquaintances and friends from outside the deceased’s immediate kin-group, and/or by corporate bodies of one kind or other (trade guilds, cult associations).Footnote 8

Not all of these features are found on every monument, but together they make a sufficiently distinctive ‘package’ that there is in practice no real difficulty in identifying and classifying marginal cases. Figures 2.2–2.5 illustrate some of the kinds of variation found within the basic Hieradoumian monument type. Figure 2.2 is a ‘standard’ Hieradoumian epitaph from the territory of Saittai, with virtually the full complement of typical textual and iconographic features (lacking only the day of the month and the age of the deceased).Footnote 9 Figure 2.3, from Silandos, includes all the same formal features, but is visibly of much cruder workmanship: both pediment and wreath are asymmetric, and the lettering is far less professionally executed.Footnote 10 By contrast, Figure 2.4, from the ancient village of Taza, is at the very top end of the scale for technical quality; it commemorates two individuals, a husband and wife (the latter still living at the time the monument was erected), and carries a relief depiction of the couple instead of a wreath.Footnote 11 Finally, Figure 2.5 is an epitaph now in the Uşak Archaeological Museum, of uncertain provenance, but certainly from Hieradoumia (probably somewhere in the eastern part of the region). The inscribed text is of the normal Hieradoumian type (date, ἐτείμησαν-formula, etc.), but the upper part of the stēlē carries an unusually elaborate relief depiction of the deceased woman, standing within a ‘bower’ of curling vine branches loaded with grapes, flanked by decorative pilasters with capitals supporting an archivolt with two fascias.Footnote 12

Figure 2.2 Epitaph of Apollonios, from Çayköy. TAM V 1, 102.

Figure 2.3 Epitaph of Papas, from Karaselendi (Silandos). SEG 57, 1225.

Figure 2.4 Epitaph of Menophilos and Meltine, from Kavaklı (Taza). SEG 34, 1200.

Figure 2.5 Epitaph of Bassa, uncertain provenance. SEG 39, 1294.

In terms of their overall geographic distribution, ‘Hieradoumian-type’ epitaphs are almost exclusively confined to the middle and upper Hermos valley. The westernmost boundary of the Hieradoumian ‘epitaphic zone’ can be drawn very sharply along the western flank of the Katırcı Dağı mountain range, the dividing line between the territories of Gordos and Loros to the east and the territories of Thyateira and Attaleia to the west (Maps 1 and 2).Footnote 13 To the west and south-west, the cities of the lower Hermos valley (Sardis, Magnesia under Sipylos) and the Lykos plain (Thyateira, Apollonis, Attaleia, Hierokaisareia) have produced virtually no epitaphs of this type. West-Lydian epitaphs generally take a quite different form: dated epitaphs are very rare, and epitaphs were typically erected (κατασκευάζειν, ποιεῖν) by a single individual for several family members, whose names are listed in the dative case.Footnote 14 To the south and south-east, Hieradoumian-type familial epitaphs do appear in the hill country north of Philadelphia, but very seldom in the plain of the Kogamos river itself.Footnote 15 No epitaphs of Hieradoumian type are known at Blaundos, in south-east Lydia. To the north, Hieradoumian-type epitaphs remain dominant up to, but not beyond, the Simav Dağları mountain range (ancient Mt Temnos). Two epitaphs of Hieradoumian type have been found at the modern village of Yassıeynehan, in the upper Selendi Çayı valley (probably the far north-east of the territory of Silandos); beyond Mt Temnos, only a single example is known from the territories of Synaos and Ankyra Sidera, in the plain of Simav.Footnote 16

Within the Hieradoumian culture zone, sub-regional variation is relatively slight. Most of the longest examples of Hieradoumian-type epitaphs, listing dozens of separate family members, derive from the western part of the region (Gordos, Daldis, Apollonioucharax), although there are exceptions.Footnote 17 Most of the earliest dated examples seem also to derive from the west, particularly from the towns of Gordos and Loros. It therefore seems reasonable to suppose that this particular commemorative habit originated in the western part of the region in the late Hellenistic period, before gradually being adopted in towns and villages further up the Hermos valley to the east over the course of the first two centuries AD. Conversely, in the north-eastern part of Hieradoumia (in particular on the large territory of Saittai), epitaphs tend to be relatively short, typically only listing half a dozen relatives or (more often) fewer. Saittai was also home to a distinctive ‘non-familial’ variant of the Hieradoumian epitaph type, in which individuals (usually, but not always, adult males) are commemorated by a trade association or other corporate body rather than by their kin; epitaphs of this ‘guild’ type are all but unknown elsewhere in the Hieradoumian culture zone.Footnote 18

It is particularly striking that the characteristic funerary practices of late Hellenistic and Roman Sardis seem to have left virtually no influence at all on the middle Hermos region. At Sardis, the most common form of funerary monument is the inscribed cinerary chest (usually bearing the deceased’s name in the nominative, with no relatives mentioned), a monumental type which is all but unattested in Roman Hieradoumia.Footnote 19 The absence of Sardian influence on Hieradoumian commemorative culture is particularly striking in light of the abundant evidence for members of the Sardian elite owning large estates in rural Hieradoumia (see Chapter 10, Section 10.2).

2.2 Familial Epitaphs in Roman Hieradoumia: Dating and Chronology

The overwhelming majority of gravestones from Roman Hieradoumia record the date of death, either at the beginning or at the end of the epitaph, and usually in the form Year – Month – Day. This is one of the most idiosyncratic features of the epitaphs of this region compared to other parts of the Greek East: the inclusion of dates of any kind on epitaphs is exceptionally rare in the ancient Greek-speaking world at any period. Here is a typical dated Hieradoumian epitaph from the city of SaittaiFootnote 20:

Year 297, (Day) 10 of the month Xandikos. Aur(elius) Bassos her husband, and Aur. Asklepides and Aur. Bassianos her sons, and Aur. Frugilla her granddaughter honoured Bassa, who lived creditably for 51 years.

Figure 2.6 Epitaph of Bassa, from İcikler. TAM V 1, 122.

This particular tombstone, like most dated epitaphs from Roman Hieradoumia, carries the ‘full’ threefold dating by year, month, and day (Figure 2.6). Epitaphs dated by year and month alone are also widely found in the region; tombstones dated by year alone are distinctly less common.Footnote 21 The year of death is generally reckoned according to either the Sullan era (85 BC) or the Actian era (31 BC), or in a few cases both. Although the Sullan era was by far the more widely used of the two, some towns in the region did use the Actian era (e.g. Daldis), and hence Hieradoumian-type epitaphs which lack a firm provenance cannot always be dated with confidence.Footnote 22 The epitaph of Bassa is firmly attributed to the vicinity of Saittai, a city which is known to have used the Sullan era, and the text can thus be securely dated to AD 212/213.Footnote 23 In fact, in this particular case, the use of the Sullan era is neatly confirmed by internal evidence; 10 Xandikos of Year 297 of the Sullan era corresponds to early spring AD 213, very shortly after the constitutio Antoniniana. In the epitaph, the four surviving members of the family all bear the nomen ‘Aurelius’ (unattested in earlier inscriptions from Saittai), while the deceased does not.Footnote 24 It is therefore highly likely that the constitutio Antoniniana took effect in Hieradoumia in the interval between Bassa’s death and the erection of her tombstone.

781 epitaphs from Hieradoumia and neighbouring regions can be dated to the year with reasonable confidence.Footnote 25 Their chronological distribution, grouped by ten-year bands, is presented in Figure 2.7. Dated epitaphs of the first century BC and of the Julio-Claudian period are relatively few in number, with a slow rising trend across the first sixty years of the first century AD. Epitaphic production rises sharply in the Flavian period (after AD 70) and reaches a peak in the later Antonine and early Severan period (160s–190s); it then drops off very sharply in the second half of the third century, and inscribed epitaphs cease altogether in the early fourth century; 90.3% of all dated epitaphs from the region (n = 705) date to the two centuries between AD 70/1 and AD 269/70. As we will see later in this chapter, precisely the same overall trends can be seen in the chronological distribution of dated votive and propitiatory monuments from Roman Hieradoumia (Figure 2.17); dated public monuments from the region are too few for meaningful analysis.

Figure 2.7 Chronological distribution of dated epitaphs from Hieradoumia and neighbouring regions (n = 781).

Can we be certain that the dates on Hieradoumian tombstones represent the date of death, rather than (say) the date on which the tombstone was erected,Footnote 26 or even the date on which a copy of the epitaph was deposited in the city archives?Footnote 27 My view is that we can. In eight epitaphs – not, it is true, a particularly large number – the phraseology makes it all but certain that the recorded date does indeed reflect the date of death.Footnote 28 In one, highly anomalous case, a certain Dionysios of Saittai is honoured with two separate tombstones, erected by different corporate groups, both dated to 19 Peritios, AD 167/8; this date must surely reflect Dionysios’ actual date of death.Footnote 29 Moreover, in a few cases where two or more individuals are commemorated by the same epitaph, separate dates are given for each deceased individual: in such instances, the two (or more) dates must surely reflect their actual dates of death.Footnote 30 More problematic are the numerous epitaphs which commemorate two or more individuals, but where only a single date is given; in such instances, I take it that the date probably reflects the most recent date of death, or the fact that one or more of the individuals commemorated is in fact yet to die.Footnote 31 In only a very small number of cases does the recorded date demonstrably not represent the date of death.Footnote 32 In the absence of strong arguments to the contrary, it therefore seems safe to assume that the dates recorded on Hieradoumian Lydian epitaphs do indeed generally represent the (or at least a) date of death; as we will see in Chapter 3, patterns in the seasonal distribution of recorded dates provide strong prima facie support for this assumption.

Of development over time in the Hieradoumian familial epitaph – evolution, refinement, decadence, decline – there is none. In both their physical form and their textual conventions, the last extant epitaphs, from the very early fourth century AD, are, to all intents and purposes, indistinguishable from those of the Julio-Claudian period.Footnote 33

2.3 Familial Epitaphs in Roman Hieradoumia: Families

It is of course quite normal for Greek and Latin tombstones to be erected by close kin of the deceased. But the epitaphs of Roman Hieradoumia typically list not just one or two close family members, as is standard elsewhere, but family groupings which may run to dozens of individuals. In one extreme case, a deceased eighteen-year-old priest at the village of Nisyra was commemorated by no fewer than thirty-two named relatives, teachers and friends, plus seven unnamed spouses, and an uncertain number of children.Footnote 34 All of these kinsmen and friends are precisely located in the deceased’s family tree: paternal and maternal uncles and aunts, brothers- and sisters-in-law, step-kin, foster-siblings, and so forth.

The form of self-representation of familial groups in the epitaphs of Roman Hieradoumia is very much sui generis: there is nothing else quite like this in the vast corpus of funerary epigraphy from the Greco-Roman world.Footnote 35 The only remotely meaningful analogies that I know of come from Rhodes and neighbouring parts of coastal Asia Minor (the Rhodian Peraia, Xanthos), where, in the second and first century BC, there was a short-lived trend for private honorific statues to be erected by large extended families – up to twenty-one relatives, including uncles and aunts, cousins, nephews and nieces, and kinsmen by marriage.Footnote 36 However, unlike in Roman Hieradoumia, these late Hellenistic Rhodian ‘family monuments’ were not tombstones; only in a very few cases can we be sure that the honorand was deceased at the time the statue was erected.Footnote 37 Nor is there any reason to think that this short-lived Rhodian familial ‘statue-habit’ exercised any direct influence on the commemorative practices of Roman Hieradoumia, and I suspect that we are dealing with entirely independent developments.

As a result of the commemorative practices of Roman Hieradoumia, we know more about family and kinship structures in this small region than in almost any other part of ancient western Eurasia.Footnote 38 As we will see in Chapter 4, thanks to these familial epitaphs, the kinship terminology of Roman Hieradoumia is known to us in extraordinary detail. We can reconstruct large extended families with absolute precision and can say something about how those families chose to represent themselves. Even if not all the individuals listed on an epitaph literally co-habited in the same dwelling, the fact that they (and not others) all joined in commemorating a deceased relative clearly tells us something about family forms in the region (see Chapter 5). Finally, we can start to say something about distinctive interfamilial strategies in Roman Hieradoumia: marriage, adoption, fosterage, and so forth.

The relationship of the ‘honouring’ individuals to the deceased seems generally to have been recorded as precisely as possible. The relevant kinship term can either appear in the nominative, describing the honourer (Μᾶρκος ὁ πάτηρ ἐτείμησεν Γλύκωνα, ‘Marcus, the father, honoured Glykon’), or in the accusative, describing the deceased (Μᾶρκος ἐτείμησεν Γλύκωνα τὸν υἱόν, ‘Marcus honoured Glykon, his son’). Similarly, if a man’s brother’s wife dies, he can either describe himself as her δαήρ (‘husband’s brother’) or describe her as his ἰανάτηρ (‘brother’s wife’). In some epitaphs, kinship terms appear in the nominative throughout; in others, the accusative is consistently preferred, and sometimes we find a mixture of the two.Footnote 39

The choice of one or the other ‘grammatical perspective’ was not entirely random. In describing cross-generational kinship relationships, there seems to have been a general preference for marking the elder generation: so the terms for ‘grandfather/-mother’ are far more common than the terms for ‘grandson/-daughter’. Furthermore, individuals seem always to have tended to gravitate towards the most precise kinship term available. As we will see in Chapter 4, the inhabitants of Roman Hieradoumia had a very rich and specialized kinship terminology for different categories of uncle and aunt (the mother’s brother, the father’s brother, the father’s brother’s wife …), but no distinct terms for the nephew and niece. Hence, when an uncle chose to honour his deceased nephew, he almost always opted to use the nominative (Γλύκωνα ἐτείμησεν Μᾶρκος ὁ πάτρως, ‘Marcus, the uncle, honoured Glykon’), while when a nephew chose to honour his deceased uncle, he generally opted to use the accusative (Γλύκωνα ἐτείμησεν Μᾶρκος τὸν πάτρως, ‘Marcus honoured Glykon, his uncle’).Footnote 40 In cases where the terminology would have been equally precise either way (e.g. siblings, cousins), the choice between the two possible grammatical perspectives seems to have been more or less arbitrary.

It is very difficult indeed to say what determined the length of the list of relatives in any given text (although, as we have seen, there is a distinct concentration of longer texts in the western half of the region). At the village of Nisyra, in autumn AD 120, a certain Hipponeikos was commemorated by his mother and his brother alone; at the same village, in winter AD 183, a boy called Dionysios, who died nine days short of his tenth birthday, was commemorated by his father and mother, brother and sister, paternal uncle, maternal aunt, two unspecified kinsmen, grandfather, maternal uncle, six slaves, four friends, and three foster-parents.Footnote 41 Can we conclude from this that Hipponeikos lived in a tight-knit nuclear family and that Dionysios belonged to a sprawling multigenerational household? Or simply that Dionysios’ family was rich, and Hipponeikos’ family was poor? It is better to confess that we simply do not know.

Nor can we be certain in any given case that the list of relatives honouring the deceased represents the complete register of those to be found around the family dinner table on Sundays (as it were). On occasion, the deceased is honoured by very small children, who cannot conceivably have been conscious actors in the commemorative process.Footnote 42 In at least two instances, individuals listed among those honouring the deceased were demonstrably already dead themselves (!).Footnote 43 In some cases, all the honouring relatives are recorded by name; in others, large parts of the family are listed in summary form, as in an epitaph for a brother and sister (perhaps twins) from Nisyra, who were commemorated by the brother’s two children, the woman’s husband and son, ‘their paternal uncles and paternal aunts, their cousins, their foster-siblings, their relatives, their private association, and their homeland’.Footnote 44 In very many inscriptions, however, long or short the list of named kinsmen may have been, the register of those honouring the deceased is rounded off with a general summary phrase such as ‘… and all the relatives, acting in common’ (καὶ οἱ συνγενεῖς πάντες κατὰ κοινόν), apparently a catch-all formula for those relatives who are not listed by name.Footnote 45 All this makes it difficult or impossible to use the funerary epigraphy of Roman Hieradoumia as hard statistical evidence for the size and shape of the extended family in the region: the list of named relatives provided in any given text seems not to have been governed by any firm rules or norms, but simply to have reflected the whim of the particular family concerned.

Nonetheless, the mere fact that we have so many epitaphs from the small towns and villages of Roman Hieradoumia listing so many members of the deceased’s extended family and social circle is a significant and profoundly startling social phenomenon in its own right. Nowhere else in the Greek-speaking world (with the partial exception of late Hellenistic Rhodes) did people choose to commemorate their kin in this remarkable manner – why did they do so here? As we will see in Chapter 4, this commemorative habit in fact goes hand-in-hand with a far richer and more precise terminology of kinship than we find anywhere else in the Greek world. Hieradoumian funerary practices in the first three centuries AD therefore reflect a culture in which kinship relations were not just more visibly commemorated, but were actually more finely defined, than in any other part of the Roman Empire. And as I will argue in Chapters 5 and 6, although Hieradoumian epitaphic practice does not allow us to ‘see’ familial structures in a direct and straightforward way, recurring patterns in the ways in which extended kin groups chose to commemorate themselves can nonetheless tell us a very great deal about the characteristic forms of familial groups in the region.

2.4 Familial Epitaphs in Roman Hieradoumia: ‘Honour’

A final distinctive feature of Hieradoumian epitaphs is the conception of the tombstone as an ‘honour’ paid by living relatives to the deceased, as seen most clearly in the ubiquitous epitaphic formula ὁ δεῖνα ἐτείμησεν τὸν δεῖνα, ‘x honoured y’, a usage which is almost entirely confined to Hieradoumia and immediately neighbouring regions.Footnote 46 This ‘honour’ was primarily conceived as residing in the erection of an inscribed stēlē to mark the place of burial, rather than the act of formal burial per se. This is made explicit in a few cases, as for instance in a verse epigram for a youthful doctor from SaittaiFootnote 47:

The young doctor Diophantos – his sister Teimais honoured him with a carved stēlē and with this inscription, as did her husband, blameless Praxianos.

Several Hieradoumian epitaphs lay particular emphasis on the making and erection of the stēlē as the primary honour conferred on the dead, by singling out those relatives who took on the specific responsibility for the construction of the funerary marker. So, for instance, in a verse epitaph from the village of Iaza in the Katakekaumene (Figure 2.8) the deceased was ‘adorned and buried’ by all his (unnamed) kin and ‘honoured with a stēlē and noble inscription’ by his (named) foster-father and wife:Footnote 48

Here I lie, Trophimos, who was reared in the city of Kollyda, and the earth covered me in Iaza, as Fate assigned. All my kin adorned and buried me, their kinsman; and Chrysanthos honoured me, his threptos, with a stēlē and noble inscription, as did Hermione, for her husband. This is the honour (geras) due to the dead, and my memory is everlasting. Year 317 (AD 232/3), month Artemisios.

Figure 2.8 Epitaph of Trophimos, from Ayazören (Iaza). TAM V 1, 475.

A still more extreme example of conceptual separation of the burial proper from the ‘honour’ conferred by the inscribed stēlē derives from the city of Sardis where, at some point in the second century AD, a certain Apollophanes constructed a familial tomb for his deceased wife Antonia, for himself, and for other individuals specified in his will. The chief funerary inscription was inscribed on the front face of the tomb itself, which probably took the form of a monumental sarcophagus: ‘Apollophanes son of Apollophanes, of the tribe Asias, constructed the memorial (τὸ μνημῖον κατεσκεύασεν) while still living for himself and for his deceased wife Antonia, daughter of Diognetos, etc’. But alongside this tomb structure, Apollophanes also set up a pedimental stēlē depicting his wife in low relief, with the simple inscription ‘Apollophanes son of Apollophanes, of the tribe Asias, honoured her (ἐτείμησεν)’. This ‘honorific’ stēlē was only one element in a larger package of burial rituals, and its full significance would only have been apparent to the viewer in the context of the wider tomb complex: indeed, the stēlē did not even carry Antonia’s name.Footnote 49

Explaining why the inhabitants of a particular region might originally have adopted a given set of epitaphic formulae is necessarily going to be speculative (assuming that ‘why’ is even a meaningful question in this context). But the honorific ‘colouring’ of Hieradoumian epitaphs does strongly suggest that this epitaph type might have originated in a kind of ‘generic transferral’ of the conventions of civic honorific epigraphy. The notion that the form and language of Hellenistic inscribed honorific decrees might have influenced the shape of funerary commemoration in Hieradoumia is not as implausible as it might seem at first sight. Across large swathes of inland Asia Minor, the habit of inscribing (Greek-language) texts on stone begins only in the second or first century BC; in very many places, the earliest inscribed texts known to us are civic honorific decrees.Footnote 50 For many communities in inner Anatolia, the practice of inscribing written texts of any kind on stone may well have begun with ‘public’ honorific decrees, and only subsequently been extended to ‘private’ texts like tombstones, making the idea of generic transplantation of honorific conventions into the funerary sphere less peculiar than it might intuitively appear.

The argument for ‘generic transferral’ can in fact be made more strongly than this. Among the earliest inscribed texts from Hieradoumia, dating to the late Hellenistic and early Julio-Claudian periods, we find a distinctive and unusual group of hybrid public/private monuments which blur together the genres of ‘civic honorific’ and ‘private epitaph’.Footnote 51 In this group of ‘hybrid’ monuments, elite individuals are honoured after their death both by the local dēmos and by their grieving relatives. This genre seems to have been particularly popular at the small towns of Loros and Gordos, neighbouring communities in the valley of the Kum Çayı (the ancient river Phrygios), between the mid-first century BC and the mid-first century AD.Footnote 52 Here is a typical example, from Gordos, dated to spring AD 37Footnote 53:

Year 121 [AD 36/7], day 1 of the month Xandikos. The dēmos of the Ioulieis Gordenoi and the dēmos of the Lorenoi honoured Neon son of Metrophanes. Metrophanes (honoured) Neon his son, Apphias and Menandros (honoured) their brother, Thyneites (honoured) his wife’s brother, Alke (honoured) her step-son, Artemidoros and Ammias (honoured) their cousin (?), the kinsmen and slaves (honoured him) with a golden wreath.

Figure 2.9 Epitaph of Neon, with posthumous honours conferred by the dēmoi of Iulia Gordos and Loros. TAM V 1, 702.

These hybrid public/private monuments, which served simultaneously as a record of public honours and as a private tombstone, seem to be a local peculiarity of Hieradoumia (Figure 2.9). Naturally, monuments of this kind would only ever have been set up for members of the local elite.Footnote 54 But it is, I hope, fairly easy to see how they could have served as a kind of ‘intermediary stage’ between Hellenistic civic honorific decrees and the ordinary sub-elite familial epitaphs of Roman-period Hieradoumia.

Various other elements of Hellenistic honorific practice similarly became ‘fossilized’ in the Roman-period funerary epigraphy of the region. On the most formal level, the use of the tapered pedimental stēlē as the typical form of gravestone in Hieradoumia – rather than (say) the sarcophagus, bōmos, cippus or doorstone – may well have been influenced by the widespread usage of pedimental stēlai for the inscribing of honorific decrees in the Hellenistic period. Perhaps most striking of all is the vegetal wreath which we find depicted on the overwhelming majority of Hieradoumian grave-stēlai, either incised or (more often) in low inset relief. This iconographic feature is certainly a direct imitation of the visual repertoire of Hellenistic inscribed honorific decrees, which often feature schematic depictions of vegetal wreaths, reflecting the common practice of crowning civic benefactors with gilded wreaths. On the funerary stēlai of Roman Hieradoumia, the Hellenistic ‘honorific wreath’ takes on a complex and baroque visual life of its own: we find wreaths integrated into abstract decorative patterns (Figure 2.10); wreaths with a portrait of the deceased at their centre, looking out as if through a circular window (Figure 2.11); and giant, intricately carved wreaths with the entire epitaph inscribed within (Figure 2.12).Footnote 55

Figure 2.10 Epitaph of Servilius, from Gordos. TAM V 1, 705.

Figure 2.11 Epitaph of Oinanthe, from Aktaş. TAM V 1, 13.

Figure 2.12 Epitaph of Hesperos, from Kömürcü. TAM V 1, 823.

It is a delicate question whether the wreaths depicted on Roman-period Hieradoumian epitaphs should be understood as reflecting a ‘real-life’ practice of honouring the dead with wreaths, or whether this is simply a conventional visual shorthand for the respectful grief felt by relatives for the deceased. In favour of the first hypothesis, we can point to a substantial cluster of Hieradoumian epitaphs in which the standard verb of ‘honouring’ is expanded to the more explicit phrase ‘honour x with a golden wreath’ (τειμᾶν χρυσῶι στεφάνωι), as in the epitaph for Neon of Gordos quoted above.Footnote 56 When Greek cities honoured their benefactors with public burial in the late Hellenistic period, the funerary honours conferred by the dēmos often included a golden or gilded wreath, which was placed on the deceased in the course of his/her funeral;Footnote 57 this practice probably underlies the incised wreaths surrounding the words ὁ δῆμος (‘the dēmos’) which often appear on late Hellenistic funerary stēlai from Smyrna and other parts of western Asia Minor.Footnote 58 In an early Hieradoumian-type epitaph from Saittai, a woman explicitly says that she has wreathed her husband ‘with the wreath depicted above’; on a late Hellenistic gravestone from Maionia, a relief depiction of the deceased and his parents is surrounded by four small holes, probably for fixing a metal wreath to the front of the stēlē.Footnote 59

All this seems strongly to imply that the wreaths depicted on Hieradoumian grave-stēlai represent real wreaths employed in funerary ritual. But some caution is required, since vegetal wreaths, either incised or in low relief, also appear in monumental contexts where we can be pretty certain that no ‘real-life’ wreaths were involved. Most notably, we have several examples of votive dedications to various deities inscribed on pedimental stēlai bearing images of vegetal wreaths (Figure 2.13).Footnote 60 In no case is there any indication that the votive stēlē serves even incidentally to ‘honour’ persons either alive or dead. The conclusion seems inescapable that on these votive dedications, we are dealing with an irrational transferral of a standard decorative schema into an epigraphic genre where it no longer bears any representational meaning. We therefore cannot rule out the possibility that on some, or many, of the hundreds of tombstones which bear an image of a wreath, the same may be true.

Figure 2.13 Votive dedication to Hekate, from Menye. TAM V 1, 523.

2.5 Propitiation-stēlai in Roman Hieradoumia: Overview

To turn from the epitaphs of Roman Hieradoumia to the propitiation-stēlai erected at the rural sanctuaries of the region is not just to move from one genre of evidence to another; it is to enter what appears to be a completely different moral universe. On their tombstones, in formulaic prose or sober and dignified verse, the peasants and small farmers of the region showed off the impeccable virtues of the deceased, and the honour dutifully paid to them by the large and tight-knit familial units to which they belonged. Yet when one opens the pages of Georg Petzl’s extraordinary corpus of Die Beichtinschriften Westkleinasiens (‘The confession-inscriptions of Western Asia Minor’, almost all of which derive from Roman Hieradoumia), one is instantly plunged into a colourful world of theft, sexual promiscuity, impiety, witchcraft, and interpersonal violence, much of it conducted within those very same tight-knit family groups which represented themselves with such grave decency in their epitaphs.Footnote 61

The sense of wild disjunction between the Dr Jekyll of the epitaphs and the Mr Hyde of the propitiatory inscriptions is only heightened by the remarkably close physical and formal similarities between the two epigraphic genres. In both cases, we are typically dealing with small tapering white marble stēlai with triangular pediments topped with palmette acroteria, often with a sculptured image in low relief at the top of the shaft; both categories of text typically begin or end with a date, in the format Year – Month – Day. The stēlai were evidently produced by the same workshops, and it looks very much as though the region’s lapidary workshops produced generic ‘blanks’, which could be used equally for tombstones or for propitiatory inscriptions (or other dedications or votives).

What actually is a ‘propitiatory inscription’? In the most schematic terms, it is an inscribed stēlē erected in a sanctuary, bearing a narrative of a private moral or religious transgression which was subsequently punished by the gods (typically in the form of the death or illness of the perpetrator or a family member). The text usually goes on to narrate the way in which the perpetrator propitiated the god’s anger (generally by the very act of inscribing and erecting the stēlē itself); many texts conclude with a short eulogy of the god’s power. Here are two fairly characteristic examples, from a rural sanctuary of ‘Zeus from the Twin Oaks’ on the territory of ancient Saittai (Figures 2.14 and 2.15):

To Zeus from the Twin Oaks. I, C(laudia) Bassa, having been punished for four years and having no faith in the god, having been successful concerning my sufferings, I dedicated the stēlē in gratitude, Year 338 [AD 253/4], day 18 of the month Peritios.Footnote 62

Great is Zeus from the Twin Oaks! I, Athenaios, was punished by the god on account of my error, because I was unaware; and having received many punishments, I had a stēlē demanded of me in a dream, and I wrote up the powers of the god. I inscribed the stēlē in gratitude in Year 348 [AD 263/4], day 18 of the month Audnaios.Footnote 63

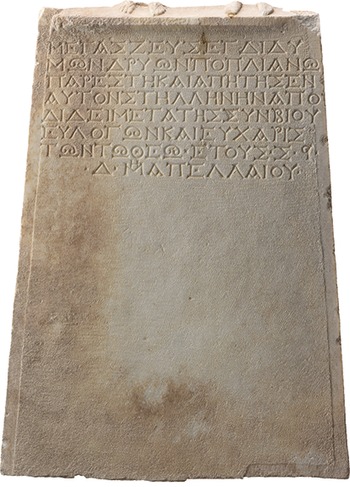

As will be clear, a fair amount of variation is possible even between near-contemporary texts from the same sanctuary (which are probably the work of the same stonemason, at that). Physically, one has a pediment, the other does not; one begins with an acclamation of the deity (‘Great is Zeus!’), the other with the name of the deity in the dative (indicating that the stēlē is formally a dedication to the god); one bears an account of the god’s ‘demand’ for a stēlē by way of propitiation (‘I had a stēlē demanded of me’), the other does not – and so on. In light of this pervasive variation in form and structure, it is unclear how hard a line we can legitimately draw between these ‘propitiatory stēlai’ (a category which is, after all, a modern scholarly construct) and other votives and dedications from Roman Hieradoumia. Take, for instance, the following dedication from the sanctuary of Zeus from the Twin Oaks, dated around a generation earlier than the two texts quoted above (Figure 2.16)Footnote 64:

Great Zeus from the Twin Oaks appeared to Poplianos and demanded a stēlē of him, which he gives along with his wife, with praise and gratitude to the god. Year 294 [AD 209/10], in the month Apellaios.

Formally speaking there is very little indeed to distinguish this monument from the stēlai of Claudia Bassa and Athenaios quoted above: their physical form is extremely similar; the god ‘demands’ a stēlē from Poplianos in a dream, exactly as he would later do for Athenaios; all three dedicators speak of their ‘gratitude’ (εὐχαριστέω) to the god; all three texts end with the date of erection of the stēlē in the format Year – Month – Day.Footnote 65 In short, the category of propitiatory inscriptions is a ‘fuzzy concept’: a fairly easily recognizable subgroup within the larger category of Hieradoumian votive and dedicatory stēlai, characterized by certain loose affinities of theme (a concern with divine punishment and propitiation), but lacking hard definitional boundaries.Footnote 66

Figure 2.14 Propitiatory inscription of Claudia Bassa. SEG 33, 1012.

Figure 2.15 Propitiatory inscription of Athenaios. SEG 33, 1013.

Figure 2.16 Votive dedication of Poplianos. SEG 57, 1224.

2.6 Propitiation-stēlai in Roman Hieradoumia: Structure

As one would expect, the textual structure of the propitiatory inscriptions varies a great deal. Nonetheless, some standard (or at least recurrent) features can be identified. The inscriptions often begin with a short acclamation of the god to whom the stēlē was erected, in the form ‘Great is Meis Artemidorou who possesses Axiotta and his power!’.Footnote 67 The ‘narrative’ part of the text frequently begins with the conjunction ἐπεί, ‘since, whereas’, a feature which is otherwise almost unknown in Greek votive and dedicatory inscriptions, and which presumably should be taken as an imitation of the typical structure of Greek honorific decrees (‘Since x has been a good man …’). The texts then proceed through a set of four fairly conventional ‘narrative stages’, not all of which are found in all inscriptionsFootnote 68:

(1) Almost all of the texts begin with at least some minimal description of the act which incurred the gods’ wrath. In many cases, only context-specific vocabulary is used (‘I swore a false oath’; ‘I entered the sanctuary while in a state of ritual impurity’; etc.), but when the action is described in generic terms, the most common word used is (ἐξ-)ἁμαρτάνω, ‘err’, and the act itself is a ἁμαρτία or ἁμάρτημα, ‘error’.Footnote 69 Hamartia is one of the most controversial terms in Greek ethical vocabulary, but it is widely accepted that the term does not connote ‘sin’, so much as a ‘mistake of fact’, a broad concept which may in Greek thought encompass both moral failing and ignorance of the true state of affairs.Footnote 70 Similarly, in Roman Hieradoumia, hamartia is demonstrably conceived primarily as an act of ‘ignorance’ rather than ‘sin’. This is clear from the terms used as synonyms for ἁμαρτάνω: we regularly find people describing their actions in terms of ‘unawareness’ (ἀγνοέω) or ‘forgetting’ (λανθάνομαι).Footnote 71 This does not signify that they did not know that they were doing anything wrong, but rather – or so I take it – that they were ‘unaware’ of the gods’ willingness to impose fearful punishments for what they themselves conceived as venial rule bending.Footnote 72

(2) The act of hamartia is then followed by a description of the divine punishment, again sometimes described with context-specific vocabulary (‘the god slew him/her’), but most commonly indicated with the verb κολάζω and/or the noun κόλασις, or with the near-synonyms νεμεσάω and νέμεσις.Footnote 73 In light of this punishment, the perpetrator of the ‘error’ is compelled to acknowledge the power of the gods. The term used for this is ἐξομολογέομαι, ‘recognise/acknowledge (the gods’ power)’, and the ‘recognition’ generally follows close after the act of punishment. The term ἐξομολογέομαι has in the past often been taken to mean ‘confess (one’s sin)’, but this is certainly incorrect: the sense ‘acknowledge the power of the gods’ is explicit in one case, and in other texts, this sense is clearly preferable to ‘confess’.Footnote 74

(3) The gods then typically demand propitiation or redress, sometimes in response to a direct enquiry from the perpetrator as to what he/she needs to do to appease the gods’ anger.Footnote 75 The technical term for the ‘demand’ made by the gods is ἐπιζητέω, sometimes with the form of redress explicitly specified (e.g. ἐπεζήτησε ὁ θεὸς στήλην, ‘the god demanded a stēlē’); a few texts use instead a clause introduced by the verb κελεύω.Footnote 76 The act of propitiating or appeasing the god is indicated with the verb (ἐξ-)ἱλάσκομαι, in place of which we occasionally find the verb (ἐκ-)λυτρόομαι, ‘pay a ransom’, particularly in cases where the act of propitiation involves a payment of cash or other goods to the deity.Footnote 77 The most common form of propitiation is the simple act of erecting an inscribed stēlē, often described with a phrase like ‘writing up on a stēlē the power of the gods’ (στηλ(λ)ογραφῆσαι τὰς δυνάμεις τῶν θεῶν).Footnote 78

(4) Finally, texts often conclude with an expression of ‘gratitude’ to the gods (usually with the verb εὐχαριστέω), and/or a statement that in future the perpetrator and his family ‘will praise the gods from now on’ (ἀπὸ νῦν εὐλογοῦμεν and similar). The idea of ‘bearing witness’ (μαρτυρέω) to the gods’ powers appears in the concluding lines of several texts; at the sanctuaries of Apollo Lairbenos and Zeus from the Twin Oaks, this act of ‘bearing witness’ is expressed in a standardized formula, ‘I proclaim that no-one should despise the god, since s/he will have this stēlē as an exemplar’ (παραγγέλλω μηδένα καταφρονεῖν τοῦ θεοῦ, ἐπεὶ ἕξει τὴν στήλην ἐξεμπλάριον).Footnote 79

There is clearly some room for debate about what the ‘central’ function of these texts might be, depending on whether we choose to lay the emphasis on the original transgressive act (‘confession-inscriptions’); the propitiation of the gods’ anger (‘propitiation-inscriptions’); or the act of praising and bearing witness to the gods’ power (‘exaltation-inscriptions’). To my mind, the accent ought to lie firmly on the latter two aspects, not the first. The transgression itself often not mentioned at all, or is described in only the vaguest of terms – sometimes no more than the simple statement that ‘I erred’ (ἡμάρτησα).Footnote 80 As we have seen, the concept of ‘confession’ is seldom explicitly articulated in these texts, and it is far from clear that the texts reveal any real conception of ‘sin’ or ‘sinfulness’. No less important, the generalizing statements with which the texts conclude – the ‘lessons learned’, if you like – only very seldom refer back to the details of the transgression.Footnote 81 Instead, the take-home messages generally focus solely on the appropriate attitude to be adopted towards the gods and their powers: ‘I proclaim that no-one should despise the god’; ‘I shall praise the god from now on’; ‘I have written up the powers of the god on a stēlē’. These formulaic phrases strongly suggest that the problem was not so much the original transgression itself, but rather the underlying contempt for the gods that these transgressions demonstrated.

It therefore seems to me – and I am certainly not the first to say so – that to call these texts ‘confession-inscriptions’ is positively misleading. It focuses on a relatively incidental part of the narrative (the description of the original transgression which revealed the perpetrator’s contempt for the gods); it also introduces inappropriately Christianizing categories (‘sin’ and ‘confession’) which are largely absent from the texts themselves. The point of these texts is rather to bear witness to the power of the gods (as manifested in the punishment) and to encourage readers to adopt an appropriately respectful attitude towards the gods and their powers. Several modern scholars have therefore preferred to refer to the texts as ‘propitiatory inscriptions’; although I am not sure this quite captures their primary function, it is certainly better than the alternative, and I have no appetite for inventing yet another name.Footnote 82

2.7 Propitiation-stēlai in Roman Hieradoumia: Chronology and Geography

Given the difficulty of drawing clear dividing lines between propitiatory inscriptions and other private votives and dedications, it would be somewhat misleading to tabulate the chronological distribution of propitiatory inscriptions alone. Figure 2.17 therefore gives the overall distribution over time of all dated ‘private’ religious texts from Hieradoumia (propitiatory inscriptions, votives, dedications: n = 219). Sixty-one of these dated texts are classed as ‘confession-inscriptions’ by Petzl and are indicated in dark grey. As one might have hoped, the overall distribution is pleasingly similar to that of dated epitaphs from the region (compare Figure 2.7 above). We see the same paucity of dated private religious inscriptions in the late republican and Julio-Claudian periods (40s BC–60s AD); as with dated epitaphs, we see a sharp rise in the Flavian period (70s–90s), a peak in the later Antonine and early Severan periods (160s–190s), and a dramatic drop-off in the second half of the third century, with production of dated propitiatory and other private religious stēlai ending around AD 300; 87.2% of the dated propitiatory inscriptions and other private religious texts from the region (n = 191) date to the two centuries between AD 70/1 and AD 269/70; the comparable figure for epitaphs is 90.3%.

Figure 2.17 Chronological distribution of dated propitiatory inscriptions and other private religious texts from Hieradoumia and neighbouring regions (n = 219).

It will quickly be seen that the distribution of propitiatory inscriptions is broadly in line with that of other private religious texts, at least in the second and third century AD. However, the genre does not really emerge until the turn of the first/second century AD. The two earliest dated texts in Petzl’s corpus of ‘confession-inscriptions’ are both in fact generically ‘marginal’ cases. The earliest dated text (AD 58) is an extended series of acclamations of Meis Axiottenos, with a narration of the help provided by the god in freeing the dedicator from custody; no ‘error’ or propitiation is involved.Footnote 83 The next dated text (AD 72) is the only known propitiatory inscription in verse (five elegiac couplets); the content fits well into the main run of propitiatory inscriptions (a man vows to erect a stēlē if he recovers from illness, fails to do so, has further tortures imposed on him, and finally dedicates a more lavish stēlē), but the idiosyncratic use of verse may suggest that the generic ‘norms’ of propitiatory stēlai were not yet fully established.Footnote 84 We should probably see the later Julio-Claudian and Flavian periods as a transitional phase, during which the regionally specific Hieradoumian practice of monumentalizing acts of propitiation was gradually emerging out of older and more conventional votive and dedicatory practices. I will offer a tentative explanation for this chronology in the final pages of Chapter 9 below.

When we turn to look at the geographic distribution of propitiatory stēlai, we find some interesting similarities and differences with the distribution of the Hieradoumian-style familial epitaph. The geographic ‘core zone’ of both epigraphic practices is identical: the middle Hermos valley between Satala in the west and Tabala in the east, with dense concentrations of relevant texts on the left bank of the Hermos in the Katakekaumene (Maionia, Kollyda, and the villages to the north: Map 3) and on the right bank of the Hermos in the large territories of Saittai and Silandos (Map 2). By my count, 138 of the 175 texts in Petzl’s corpus (78.9%) can be certainly or very plausibly attributed to this ‘core zone’.Footnote 85 A further seven texts derive from closely neighbouring regions: one from Buldan, south-east of Philadelphia near Apollonia–Tripolis, and six from Sardis.Footnote 86 Eight monuments derive from various parts of western and central Phrygia, but in each case, their classification as propitiatory stēlai is questionable at best.Footnote 87 Twenty-one of the remaining twenty-two texts derive from the remote rural sanctuary of Apollo Lairbenos, some distance to the south-east of the main Hermos cluster, on the left bank of the Maeander in the modern Çal ovası (Map 1).Footnote 88 One final outlier is said to derive from Akçaavlu, in the upper Kaystros valley north-east of Pergamon; but since the text refers to a cult of Zeus Trosou, a deity whose sanctuary is known to have been located near the sanctuary of Apollo Lairbenos at modern Akkent, it is quite possible that this stēlē has ‘migrated’ northwards from the Çal ovası in modern times.Footnote 89

Two features of this geographic spread are of particular interest. First, the total absence of propitiatory texts from the westernmost part of the Hieradoumian culture zone, west of the Demrek (Demirci) Çayı: we have not a single propitiatory inscription (and, for that matter, very few votive and dedicatory texts of any kind) from the territories of Gordos, Loros, Daldis, or Charakipolis, all of which have produced substantial numbers of Hieradoumian-type epitaphs. Second, the presence of a substantial group of propitiatory stēlai from the rural sanctuary of Apollo Lairbenos, far to the south-east of the main Hieradoumian culture zone, located in a region which has produced no epitaphs of the distinctive Hieradoumian type. There is nothing particularly disturbing about these geographic ‘mismatches’: it would, indeed, be startling if the spatial distribution of two distinct groups of cultural artefacts ever mapped onto one another with absolute precision. It is worth noting that the ‘outlying’ group of propitiatory inscriptions from the sanctuary of Apollo Lairbenos does in fact show some minor but consistent differences from the ‘main’ Hieradoumian group: none of the stēlai from the sanctuary of Apollo Lairbenos bear dates, and none of them include acclamations of the deity.

In short, the distribution of propitiatory stēlai in both time and space, while not identical to that of Hieradoumian-type epitaphs, is certainly close enough to suggest that the two monumental practices can usefully be treated as different aspects of a single distinctive regional culture.

2.8 Epitaphs and Propitiations: Towards a Cultural History of Roman Hieradoumia

This final point can in fact be pushed one step further. As we have seen, in formal terms, there are very strong overlaps between the propitiatory inscriptions and the epitaphs of Roman Hieradoumia: their physical form is more or less indistinguishable (pedimental stēlai with a decorative feature on the upper part of the shaft), and both categories of text typically begin or end with a date in the form Year – Month – Day. But the affinities between the two groups of texts in fact go further than that. One of the most striking recurrent features of the propitiation-stēlai is the conception of the immediate family unit as a single ‘moral entity’ which bore collective responsibility for the errors of its members. When an individual committed a hamartia, his or her closest relatives were considered to be implicated in the act in various ways: the god’s punishment often fell not on the perpetrator, but on one or more close kinsmen or -women, and it was very often other family members who ended up performing the formal act of propitiation (sometimes, but not always, after the perpetrator’s death). Here, for example, is a propitiatory stēlē from a sanctuary of Meis Labanas and Meis Petraeites (almost certainly at the village of Pereudos), in which divine vengeance fell on the perpetrator’s son and granddaughter, who are depicted alongside the penitent man in the relief panel (Figure 2.18) Footnote 90:

Great are Meis Labanas and Meis Petraeites! Since Apollonios – when a command was given to him by the god to reside in the house of the god – (5) when he disobeyed, (the god) slew his son Iulius and his grand-daughter Marcia, and he inscribed on a stele the powers of the gods, and from now on (10) I praise you.

Figure 2.18 Propitiatory inscription of Apollonios. SEG 35, 1158.

Table 2.1 Persons said to have been punished for a relative’s hamartia in Hieradoumian propitiatory inscriptions

Petzl no. | Perpetrator | Person(s) punished (killed) | Person(s) depicted on relief |

|---|---|---|---|

1994, no. 10 | Male | Perpetrator and ‘whole household’ | Perpetrator |

1994, no. 62 | Female | Father | Victim |

1994, no. 7 | Male (?) | Son | Perpetrators and victim |

1994, no. 64 | Male | Two sons | None |

1994, no. 69 | Female | Perpetrator and son | None |

2019, no. 127 | Male | Son and daughter-in-law | None |

1994, no. 37 | Male | Son and granddaughter | Perpetrator and victims |

1994, no. 34 | Male | Daughter, ox and donkey | None |

1994, no. 45 | Male | Daughter | None |

2019, no. 168 | Female | Daughter | None |

1994, no. 71 | Male | Female relative | None |

2019, no. 160 | Male | Female relative | None |

1994, no. 28 | Male (?) | Son-in-law (?) and others (?) | None |

1994, no. 113 | Male | Ox | None |

This collective responsibility seems generally not to have extended very far within the family group. We have no examples of persons being punished for the sins of their uncles or aunts, brothers-in-law, or sisters-in-law. Instead, as is clear from a glance at Table 2.1, divine punishment generally fell either on the perpetrator or on his/her children alone; we have single instances of punishment being extended to the perpetrator’s father, daughter-in-law, son-in-law, and granddaughter, and a solitary example where the perpetrator’s ‘whole household’ was made ‘close to death’.Footnote 91 It may be significant that we have no certain cases of a spouse or a sibling being punished: the underlying conception seems to be that divine anger tends, as a general rule, to travel ‘vertically downwards’ within the perpetrator’s family lineage. In fact, this fits rather nicely with wider local conceptions of the ‘heritability’ of guilt: epitaphs from Roman Hieradoumia (and other parts of inland Asia Minor) often include a curse-formula stating that the gods’ anger will pursue tomb robbers ‘to their children’s children’, and in a propitiatory inscription from the village of Perkon, a penitent man likewise claims to have ‘appeased the gods, to my children’s children and my descendants’ descendants’.Footnote 92 As it happens, we have no examples of foster-children (threptoi) being punished for their foster-parents’ transgressions; but we do find the children of two women who have committed a hamartia of some kind collectively propitiating the goddess ‘on behalf of their children and foster-children’, indicating that it was seen as a realistic possibility that the goddess’ anger might fall on either their natural children or their threptoi.Footnote 93

When it came to the propitiation of the gods, we find a somewhat wider range of family members taking on responsibility for appeasing the gods’ wrath, although still very seldom extending far beyond the immediate nuclear family group: the evidence is collected in Table 2.2.Footnote 94 Once again, the perpetrator’s sons and daughters are by far the most heavily represented, although we also find spouses, siblings, grandchildren, foster-children, and – in a case where the offenders seem to have been children – parents.Footnote 95

Table 2.2 Persons responsible for seeking appeasement on a relative’s behalf in Hieradoumian propitiatory inscriptions

Petzl no. | Perpetrator | Person(s) responsible for appeasement | Person(s) depicted on relief |

|---|---|---|---|

1994, no. 8 | Unknown | ‘The family’ (syngeneia) | None |

1994, no. 22 | Male and female | Parents | None |

1994, no. 9 | Male | Son | None |

1994, no. 46 | Male | Three sons | None |

1994, no. 74 | Female | Son | None |

2019, no. 135 | Female | Son | None |

1994, no. 39 | Male | Perpetrator and son | None |

1994, no. 24 | Male | Son and two grandsons (by a different son) | None |

2019, no. 142 | Male | Son and daughter’s daughter | None |

1994, no. 54 | Male | Daughter | None |

2019, no. 143 | Male | Daughter and son | None |

2019, no. 151 | Female | Perpetrator and daughter | None |

1994, no. 70 | Two females | Daughters and sons | Perpetrators (breasts/leg) |

1994, no. 36 | Female | Heirs (klēronomoi) | None |

1994, no. 69 | Female | Daughter’s daughter and her three brothers | None |

1994, no. 44 | Female (and her threptos) | Grandson | None |

1994, no. 58 | Female | Husband | None |

1994, no. 102 | Female | Husband | None |

2019, no. 141 | Male | Wife | Perpetrator (leg) |

1994, no. 15 | Male | Wife | None |

1994, no. 68 | Male | Wife, child and brother ‘with the children’ | None |

1994, no. 34 | Male | Wife (?), three sons and one daughter | None |

1994, no. 72 | Male | Brother | None |

1994, no. 18 | Male | Brother, heirs, brother-in-law (?) | Perpetrator |

1994, no. 4 | Male | Two foster-daughters (tethrammenai) | Perpetrator |

The underlying conception of the workings of divine punishment and propitiation is not in itself distinctive: as readers of Greek tragedy will be well aware, the concepts of ‘ancestral fault’ and ‘inherited guilt’ had a long prehistory in Greek thought.Footnote 96 What is unusual and striking is the decision of so many Hieradoumian families to place all the mortifying details of these familial catastrophes on public display, at what was no doubt a serious cost to familial honour. In short, just as with the familial epitaphs of Hieradoumia, the propitiatory inscriptions of the region also served as a form of familial self-representation, underlining in both words and images – even in this most reputationally damaging of contexts – the solidarity of the family unit as the basic ‘building-block’ of Hieradoumian rural society.

As will by now be abundantly clear, the propitiatory inscriptions of Roman Hieradoumia are of immense value for our understanding of religious mentalities, ritual practices, and (thanks to their extensive descriptions of divine ‘punishments’) the social history of illness in Roman Asia Minor. Over the past generation or so, the texts have attracted a large body of first-rate scholarship coming from one or more of these perspectives.Footnote 97 For us, though, the primary interest of these texts lies elsewhere, in their status as a highly localized cultural epiphenomenon, the product of a particular rural society located very precisely in space (the middle Hermos valley) and time (the first three centuries AD). Indeed, as we have seen, one of the most remarkable things about the propitiatory inscriptions is how closely they map on to the geographic and chronological contours of the Hieradoumian ‘familial’ epitaphic habit. The two monumental genres can usefully be treated – as they will be in this book – as the two halves of a local diptych, speaking to us about a single, largely rural village culture. Put crudely, the epitaphic half of the diptych tells us about social norms: the ways in which individuals, families, and corporate groups wished ideally to be seen and remembered by their peers. The accent throughout is on honour, sentiment, familial and corporate solidarity, and the exemplary virtues of the deceased. The propitiatory half of the diptych tells us about moments of social dysfunction – moments when a member of Hieradoumian rural society has deliberately or (less often) inadvertently transgressed that society’s collective norms. The epitaphs reflect the mechanisms of solidarity within peasant society; the propitiatory texts give us a series of brief but sometimes brilliant glimpses into the subterranean tensions of that society, when the interests of one family member rub up hard against those of another, or when one household ends up locked in a vendetta with another, or when an individual chooses to put him- or herself at odds with the wider community. Neither aspect of Hieramounian culture – neither the static nor the dynamic – can be properly understood without the other.

In the chapters that follow, I shall attempt to trace the outlines of the society that produced these two remarkable bodies of cultural artefacts. This society was, I will argue, a fundamentally kin-ordered one, in which laterally and vertically extended kin groups played a central role in the organization of social life. The forms and functions of kinship in Roman Hieradoumia will be described in three lengthy chapters (Chapters 4–6), dealing in turn with kinship terminology, household structure, and the circulation of children between households (‘fosterage’). In Chapter 7, we will look at the extra-familial corporate groupings (friends and neighbours, cultic and trade associations, political communities) who appear alongside kin groups in commemorative contexts. Chapter 8 turns to the role played by the village sanctuaries of Hieradoumia in the organization of rural society, with a particular focus on land and labour. Chapter 9 draws on the narratives recorded in the propitiatory stēlai to evoke some of the inter- and intra-familial dynamics of village life in Roman Hieradoumia. Chapter 10 attempts to draw some of these threads together into a coherent picture of the social structure of Hieradoumia in the first three centuries AD. Before all that, though, we ought to begin with a few words about the region’s underlying demographic regime.