In February 1892, a French mining journal published a report on oil seepages at Chia Sorkh, a patch of desert roughly 90 miles west of the Iranian city of Kermanshah. Suspecting that there might be deposits buried nearby, William Knox D’Arcy, an English businessman, sent a delegation to Iran’s ruler, the Qajar shah, to secure rights to “obtain, exploit, develop, render suitable for trade, carry and sell” any oil that might be found. The shah accepted D’Arcy’s offer of a £20,000 lump sum and 16 percent of “net profits.” A team of English drillers discovered oil seven years later in Khuzestan, Iran’s southwestern province.Footnote 1 By 1920 Iran was a major producer. The oil industry was run by the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC), a British corporation and successor to D’Arcy’s original venture. Iran’s government had little say in how the company operated – “unaware,” wrote Iranian engineer Mustafa Fateh, “except for a few involved in the work”Footnote 2 – and received only a slim tithe that rarely amounted to 16 percent of net profits.Footnote 3

Twenty years later, with Iran now under Anglo-Soviet occupation and state finances in disarray, the American financial expert Arthur C. Millspaugh arrived in Tehran. Charged with assisting the bankrupt Pahlavi state after the invasion of 1941, Millspaugh assumed jurisdiction over Iranian finances. Iran was, as he put it, “psychologically and politically unprepared” to operate as a modern nation-state, charging into a modern future “[like] a child forced prematurely to live the life of an adult.”Footnote 4 Foreign control featured both in how Iran’s oil was produced and in how the riches of oil were spent. Both APOC and Millspaugh reflected the idea that Iran’s oil was too valuable to be left in Iranian hands.

This chapter explores the origins of the global oil economy, Iran’s relationship with the international oil companies, and the circumstances surrounding the American entry into Iran and policy of dual integration. In the first half of the twentieth century, private corporations constructed systems for extracting oil based on coercive power and the legal regime of the concession. Despite fears that the oil would soon run out, the industry’s greatest problems were abundance and the threat that overproduction posed to prices and profits. The challenge of abundance was matched by that of security – specifically the companies’ need to secure overseas possessions from resource nationalism. In Iran, the assertive new Pahlavi state sought political legitimacy and financial power by challenging the British oil company. While the company desired cooperation with the Pahlavi shah, it obtained much greater security in 1941 when Anglo-Soviet armies invaded Iran, deposed the shah, and placed the oil fields of Khuzestan under occupation. Control over the oil resources of the Global South was a strategic objective for the Great Powers and a commercial goal of the major oil companies, which combined their dominance of production with collusion at the corporate level to manage output, maintain profits, and mitigate competition. The Pahlavi state attempted to leverage access to oil for its own ends, both to play Great Powers against one another and to secure financial resources and prestige.Footnote 5

For the United States, controlling oil went hand in hand with advancing a developmentalist agenda. Americans treated Iran as a test case for an “enlightened” wartime policy, seeing the country’s instability as a sickness caused by elite corruption and foreign imperialism. Wartime advisors arrived in Iran under the belief that administering a cure would require American management, even as American companies made a concerted effort to break the British monopoly over Iranian oil. This confused, and ultimately failed, policy found clarity in the context of the Cold War, where the protection of Iranian territorial integrity and the development goals of the pro-US Pahlavi government were united under the American mission to safeguard Iran and the rest of the oil-producing Middle East from Soviet influence.Footnote 6

Issues of oil and development – of petroleum and progress – were closely intertwined. By 1947 a new American approach had emerged that linked the sale of Iranian oil on the global market to an indigenous development program fostered by Pahlavi technocrats and American developmentalists. The British oil company became the primary instrument of American policy in Iran, as its operations offered the key to ensuring the country’s economic development and territorial integrity. Concern for Iran’s future stability was paramount. Equally important was maintaining access to oil in order to feed Western consumption and protect the United States and its allies from the danger of shortage.

1.1 Oil Imperialism and Petro-Nationalism

As soon as oil became vital to the functioning of industrial society, fears arose over when it would run out. “The time will come,” warned Indiana’s state geologist in 1896, “when the stored reserve [of oil] … will have been drained.”Footnote 7 The first survey of US petroleum reserves conducted in 1908 determined that American oil would be exhausted by 1935.Footnote 8 This, of course, did not happen. New deposits were found to replenish national reserves, and the United States remained a net exporter of oil until the 1940s. The “oil scarcity ideology” was based more on fears of future insecurity than on accurate readings of geological data.Footnote 9 Chief among those fears was the worry that the United States – which accounted for more than half of world oil consumption in 1919 – would become dependent on imported oil, shackling the nation’s future prosperity to foreign interests. In the wake of World War I, the US government encouraged American oil companies to go abroad and secure oil for future domestic consumption.Footnote 10

Though they were wary of direct government oversight, the oil companies formed close ties with Washington and accepted federal help in pushing their interests abroad. “Such cooperation … may not be in strict accord with the laws of competition,” noted Jersey Standard’s A. C. Bedford in the Oil and Gas Journal, “[but] does not necessarily signify disaster.”Footnote 11 While public–private cooperation served national needs, the companies cooperated with one another for commercial reasons. Since the nineteenth century, oil markets had been defined by intense fluctuations. Producers tended to increase output as quickly as possible in a rush to out-pump their competitors before prices collapsed. In time, companies adopted vertical integration, growing large enough to control every aspect of oil’s production, refining, transportation, and marketing – a model pioneered by John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, which by the 1890s controlled roughly 90 percent of the American petroleum market. The companies could also manage the market through horizontal integration, colluding with one another through formal or informal cooperative agreements. Horizontal and vertical integration acted as breaks on oil’s volatility, ensuring profitability and mitigating the harmful effects of destructive competition.Footnote 12

By the early twentieth century, the global oil industry was dominated by a small number of vertically integrated companies, known as “majors.” The largest were the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey (Jersey Standard) and Royal Dutch / Shell. These firms were later joined by APOC (later AIOC and then BP), the Texas Oil Company (Texaco), Gulf Oil, the Standard Oil Company of California (Socal, later Chevron), and the Standard Oil Company of New York (Socony, later Mobil).Footnote 13

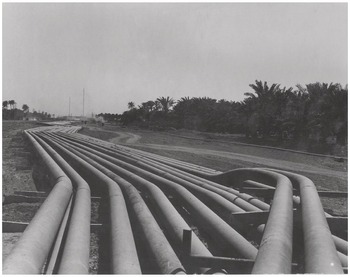

The United States dominated the industry (five of the seven largest firms were American) and possessed domestic reserves to rely upon. For other Great Powers, oil was an imperial venture. In June 1913, as the Royal Navy transitioned from coal to oil, First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill recommended that His Majesty’s Government purchase a controlling stake in APOC to ensure stable access to affordable crude oil in Iran and elsewhere in the Middle East. After discovering oil in 1908, APOC built a refinery on the island of Abadan connected via pipelines to oil fields in Khuzestan (Figure 1.1). By 1927 the company possessed fixed assets of £48 million while Iranian production reached 3,161,000 tons per year (64,519 barrels per day, or bpd). APOC joined Shell, Jersey Standard, and several other American majors as a vertically integrated oil company, albeit one that served political as well as commercial interests.Footnote 14 “Persia,” as Iran was still known, acted as a strategic petroleum reserve for the British Empire, while APOC also worked to secure a concession in neighboring Iraq – a League of Nations mandate granted to Britain following World War I.Footnote 15

Though Iran was never formally colonized, APOC’s presence was unmistakably colonial. In Abadan, European staffers enjoyed social amenities, swimming pools, and social clubs, while the Iranian workforce lived in sprawling slums paying exorbitant rents to predatory landlords. APOC employed Europeans to fill technical jobs and Indians to serve as clerks and administrators, retaining Iranians to run industrial activities without providing them additional education or training. Such dynamics helped to ensure the dominance of the management, which in turn supported stable production and ensured long-term profitability.Footnote 16 The global oil industry was dominated by such inequities. The oil fields of Indonesia, which came online in the 1880s, and those of southeastern Texas in the early twentieth century were colonial spaces divided along racial lines.Footnote 17 Americans transplanted the forms and functions of Jim Crow to the deserts of Arabia during the 1930s.Footnote 18 Abadan, with its comfortable European quarter and sprawling refinery slum, was no different.

APOC carried on its activities without interference from the Qajar government in Tehran. Iran’s rulers exerted little influence on the provinces, and the company relied more heavily on local proxies, including pro-British tribes and the Arab sheikh of Mohammerah (the Arabic name for the Iranian port city of Khorramshahr), than on support from the Iranian state.Footnote 19 But oil companies could not ignore the central governments entirely, for a simple reason: The oil produced out of the ground was, legally speaking, the property of the state. Companies acquired concessions from the local governments to search for and exploit minerals in a specific area for a specific period of time. The state retained sovereignty over oil and could expropriate or nationalize privately held property through legislative fiat.Footnote 20 In practice, however, the legal regimes surrounding concession agreements were bound up in relevant power dynamics. In Mexico, local law was either willfully misinterpreted to suit the oil men’s interests or ignored entirely. Reserves worth millions of dollars could be acquired “[for] 300 or 400 pesos,” wrote geologist Everette Lee DeGolyer.Footnote 21 Concessionary regimes were lopsided in the favor of companies, which could set the terms of equitability – the substance of a “fair” agreement – with little input from the local governments.

In time, opposition to the imperial influences of the companies increased. In Mexico, hellish working conditions and low pay prompted labor demonstrations in the 1920s. Article 27 of the 1917 constitution asserted national sovereignty over mineral rights: In the realm of oil exploitation, “the dominion of the Nation is inalienable and indispensable.”Footnote 22 This opposition – combined with the deteriorating geological conditions of most major Mexican oil fields – encouraged the companies to shift their attentions to Venezuela, where output increased from 900 bpd in 1918 to 289,000 bpd in 1928.Footnote 23 The experience proved the threat of resource nationalism, but it also illustrated the companies’ flexibility. Should a challenge emerge, investment could be shifted elsewhere, so long as oil was abundant. In the words of one official in the US State Department’s Office of Petroleum Affairs, the policies of major oil companies “resemble those of the Vatican – both can afford to wait.”Footnote 24

While oil’s abundance gave the companies flexibility when faced with rising petro-nationalism, it depressed prices and increased destructive competition. As policymakers in London and Washington worried about potential shortage, oil executives contemplated a lack of markets and price wars that would sap profitability. In 1925, the American Petroleum Institute, the major lobbying group for the American oil industry, published a report concluding that there was “no immediate danger” of reserves being depleted, provided prices remained high enough to drive continued investment.Footnote 25 The dominance of a few vertically integrated companies encouraged cooperation to maintain prices and avoid destructive competition. In September 1928, the heads of the three largest majors – John Cadman of APOC, Walter Teagle of Jersey, and Henry Deterding of Shell – met at Achnacarry Castle in Scotland to formalize cooperative management of the global oil industry.Footnote 26 “Excessive competition has resulted in the tremendous overproduction of today,” they stated.Footnote 27 In the Middle East, production would be controlled through a “self-denying” clause known as the Red Line Agreement, while the majors agreed to leave market share “as-is” to mitigate competition.Footnote 28 What was imagined was not a cartel, but an oligopoly – a cooperative arrangement of producers who colluded to limit output while continuing to compete with one another under controlled conditions.Footnote 29

There was no “free” oil market. In the oil fields of Iran, Mexico, Venezuela, Indonesia, and elsewhere, colonial regimes ensured foreign control of oil resources which were, legally speaking, the property of the state. Globally, the companies colluded to restrict competition. In 1931, as the Great Depression caused oil demand to plummet, National Guard troops were deployed to shut down oil wells in Texas and Oklahoma. Violence served to produce scarcity, ensuring profitability – the tools of empire were deployed on the American oil patch.Footnote 30 The companies were not always comfortable with government intervention but would accept it when necessary. The paramount need, according to W. S. Farish of Humble Oil, was to prevent “unrestrained competition” and permit “orderly production.”Footnote 31 Yet while the issue of abundance was managed through collusion, the challenge of petro-nationalism remained unresolved, as APOC would discover when a new government rose to power in Iran.

1.2 “A Bird That Lost Its Feathers”: Oil and Pahlavi Iran, 1921–1941

In February 1921, a column led by the military commander Reza Khan marched into Tehran and overthrew the regime of the Qajar shah.Footnote 32 Within several years, the new dictator had rebuilt the army, defeated several insurrections, subdued Iran’s semi-autonomous tribes, and brought the state under his control. In 1925, the national parliament, or Majlis, decided to make him the new shah by law. A single deputy, Mohammed Mosaddeq, objected to having executive and royal power placed in the same hands. The deputy’s objection was not enough to stop the relentless drive of the new government.Footnote 33 Reza Shah Pahlavi I assumed the Peacock Throne in 1926, with his son Mohammed Reza (seven years old, “a wee mite … without any reserve or nerves” according to APOC chairman Sir John Cadman) at his side.Footnote 34

Iran’s bourgeoisie hailed the arrival of the military dictator as a turning point in the nation’s history. Lying between the rival empires of Russia and Britain, Iran had struggled against pervasive foreign influence throughout the nineteenth century. Popular discontent spiked in 1890 when the Qajar shah ceded control of Iran’s tobacco trade to a British interest. A general revolt erupted in 1906, forcing the shah to recognize the country’s first constitution and national parliament. The constitutional government survived years of invasion and fiscal crisis, before collapsing in the wake of the 1921 coup d’état. Former revolutionaries like Sayyed Hasan Taqizadeh, who had once argued that Iran “outwardly and inwardly, physically and spiritually, become European,” rallied to the dictatorship, hoping to use it as a vehicle for a national revival.Footnote 35 Others looked for a more tangible reconstruction. “As long as we refuse to dedicate ourselves to an economic revolution,” wrote Ali-Akbar Davar, the shah’s minister of justice and author of Iran’s first modern legal code, “we will remain a submissive nation of disaster-stricken, starved, and tattered cloaked beggars.”Footnote 36 Tehran was rebuilt, hospitals and schools erected, and a Trans-Iranian Railroad established to connect the capital to the provinces. Reza Shah built a system of state-owned factories and pumped most of the foreign exchange earned through exports into building up the country’s industrial base, though he reserved payments from the British oil company for more exotic items, including modern armaments that he purchased from a special account.Footnote 37

While Europe offered a vision of what Iran could become, eliminating foreign influence formed an important part of the new regime’s agenda. In 1927, Reza Shah announced the “abrogation of capitulations.” Like Article 27 of the Mexican constitution, the law was meant to express Iranian independence from foreign influence.Footnote 38 In an important act of fiscal reform, the regime formed a new central bank, the Bank-e Melli, to manage the national money supply, a mandate formerly held by the Imperial Bank of Persia, a British institution. But it was the oil company that received special attention. Touring the oil fields, the shah – an imposing, authoritative figure who made a habit of striking people with his cane when he thought them flippant or disobedient – made it clear that the days of British autonomy were over. “Iran,” he declared, “can no longer tolerate the profits of its oil going into foreigners’ pockets.”Footnote 39

During meetings with APOC chairman Sir John Cadman, Reza Shah’s minister of court, the urbane Abdolhossein Teymurtash, described the industry as the “Tree of Life” upon which Iran’s financial and economic wellness depended.Footnote 40 The oil royalty represented only a portion of Iran’s revenue: A study by the shah’s American financial advisor Arthur C. Millspaugh estimated APOC’s payments constituted between 9 percent and 12 percent of the state budget between 1922 and 1926, while the industry was an enclave detached from the rest of Iran’s predominantly agricultural economy.Footnote 41 Nevertheless, the Pahlavi state was determined to exert pressure on the company in order to secure better terms and more revenue. “We do not say that the Persian government should abolish the concession,” explained Teymurtash to Cadman, “but we do say that it should be revised … we have been cheated quite badly in this bargain.”Footnote 42

APOC’s chairman believed the company needed to change its policies. It was clear, Cadman wrote in 1926, that strong feelings had grown among Iran’s elite, “due to the impression that [APOC] was taking huge profits out of the country and doing very little for its inhabitants.”Footnote 43 A thoughtful and intelligent man, Cadman displayed an astute understanding of Iran’s new political status quo. “There is a new Persia to-day and the old method of dealing with her is out of date,” Cadman wrote in 1928. The company had to act, Cadman argued, before Iranian demands grew too great: “[W]e are out to save our own skin.”Footnote 44 In 1932, oil prices crashed amid the global depression. APOC’s royalty to Iran fell to just £306,872. Facing a depleted treasury and furious over the slow pace of negotiations, Reza Shah canceled the D’Arcy Concession in November. Shortly thereafter he had Teymurtash arrested. The minister later died in prison.Footnote 45

Cancellation was not nationalization. Despite the rhetoric of the Pahlavi regime, the shah was not prepared to take over the industry. Instead, his government argued that APOC had reduced the royalty through “prodigality and extravagance.”Footnote 46 It had not, in other words, lived up to its side of the D’Arcy Concession. The British response was one of indignation. Whitehall discussed whether the cancellation warranted a military intervention and additional warships were moved into the Persian Gulf.Footnote 47 But Cadman opted for diplomacy. He traveled to Iran in April 1933 and after several days of discussions compelled the shah to intervene personally. According to one account, Cadman promised “essentially what the Shah wanted, if not in the form his ministers and experts recommended.”Footnote 48 The concession area was reduced by 80 percent, while Iran was promised an annual royalty minimum of £750,000. The agreement came with a hefty lump sum: Payments to the Iranian government for 1933 totaled £4,107,660. In a brief speech, Cadman described the company as “a bird which had lost a great deal of plumage” but that would in time “regain its feathers.”Footnote 49 “The general feeling,” wrote the American minister, “is that the Persian Government has more or less proven its case.”Footnote 50

In private, however, Cadman felt he had won a major victory. APOC now had a concession that would not expire until 1993. The company’s longtime legal advisor proclaimed it “the best concession he had ever seen.”Footnote 51 Some of the less favorable articles in the 1901 D’Arcy Concession were eliminated, clarifying the terms of the company’s control. Most importantly, the new agreement forbade Iran from changing or withdrawing from the concession agreement without consulting APOC. Cadman successfully concealed the actual extent of the deal’s terms. “It was not desirable,” he told the Foreign Office, “to stress the many features of the agreement which were favorable to APOC until the appropriate time.”Footnote 52 By the time observers in Iran realized the scope of the new concession, it was too late.

The cancellation crisis of 1933 established a trend that dominated the relationship of the Pahlavi regime to the international oil industry over the next thirty years. While nationalist rhetoric and invocations of sovereign power allowed Iran’s government to pressure the company, the shah was more interested in the appearance of a moral victory – and cash. A new basis in equitability appeared in 1933, thanks to British pressure and Cadman’s adroit diplomacy, but it was largely illusory: While APOC paid Iran more money, its control of Iranian oil did not change.

As future Iranian petro-nationalists would point out, Iran’s case against APOC was weakened by the terms Reza Shah accepted in April 1933, suggesting the shah colluded with the British.Footnote 53 Existing accounts (including the company’s own archives) make it very clear that the decision to cancel had been made by the shah himself, partly in a fit of pique over the failure of his ministers to reach a new oil deal.Footnote 54 As Sayyed Hasan Taqizadeh, the shah’s minister of finance, told one APOC official: “[A]ll important matters in this country are decided by the great man of the time.”Footnote 55 Cadman made sure Iran’s great man remained satisfied. Between 1932 and 1941 APOC paid the shah’s government £25 million.Footnote 56 The company became the “Anglo-Iranian Oil Company,” or AIOC, and made an effort to improve living conditions in Abadan. These were token gestures: The company’s goal, Deputy Chairman William J. Fraser declared during a meeting of the company’s executive leadership, was not to educate or train Iran, “but to exploit its oil resources.”Footnote 57 The new agreement provided the company a legal basis for doing so for another sixty years.

Cadman died in May 1941. In August, Anglo-Soviet forces invaded Iran, removed Reza Shah from power, and occupied the country. The move, ostensibly meant to purge the country of German influence, ensured Allied control of the Iranian oil fields and the supply line from the Persian Gulf to the Soviet border. As British troops garrisoned Abadan, foreign control over Iranian oil appeared permanent. But the conditions of war upended the fragile truce won by Cadman in 1933. The Anglo-Soviet occupation opened Iran up to a new age of Great Power competition. And the arrival of the United States, with its untested and experimental new policy, produced a set of circumstances which would alter the status quo governing Iranian oil.

1.3 Occupation, “Incapacity,” and Expertise: American Advisors in Iran, 1941–1945

Reza Shah’s power collapsed amid the Anglo-Soviet invasion of August 1941. In the vacuum left by his departure, Iran split into spheres of influence: Soviet in the north, British in the south.Footnote 58 Symbols of the country’s modernization were turned toward the war effort. The Trans-Iranian Railway was used to shuttle Allied war material from the Persian Gulf to the Soviet Union and the British forced the Bank-e Melli to print billions of new rials (the national currency) to fund the occupation. The number of rials in circulation grew from 990 million in 1939 to 6.8 billion by 1944, causing rampant inflation that was further compounded by food shortages and a breakdown in trade.Footnote 59 The war was a national calamity, one that would leave a permanent scar on all who lived through it.

Despite the shock of the invasion, the fall of the first Pahlavi liberalized Iranian politics. New political organizations emerged, including the Hizb-e Tudeh, or “Party of the Masses,” formed by a group of leftist intellectuals freed from Reza Shah’s prisons in 1941. Like the Pahlavi regime, the Tudeh expressed an ideology of national transformation, albeit one influenced by Marxist-Leninist principles. The Engineers’ Association, a group of Western-educated doctors, lawyers, and professionals expressed the need for administrative reform and an end to corruption.Footnote 60 The ‘ulama, Iran’s Shi’a clerical class, also returned to the fore. One tract, Kashf al-Asrar (Secrets Revealed), denounced European “decadence” typified by Reza Shah’s reforms and called for a return to Islamic governance. The author, a relatively obscure cleric named Ruhollah Khomeini, did not object to the institution of monarchy. But he did suggest the shah be bound by Islamic jurisprudence.Footnote 61

Though frequently at odds with one another, these new dissidents embraced a worldview centered on rejecting foreign influence over domestic political affairs (though this would change in the case of the Tudeh Party). The position was expressed eloquently by the nationalist Majlis deputy Mohammed Mosaddeq, the same man who had opposed Reza Khan’s ascension in 1925. In 1944 Mosaddeq suggested Iran adopt a position of “passive balance” (muvazanah-e manfi) also referred to as “negative equilibrium.” Trying to balance foreign interests – like offering additional oil concessions to balance the AIOC position in Khuzestan, for example – was like “asking a man, who has lost one of his arms, to cut his other arm for the sake of balancing his body.”Footnote 62 Iran should adopt a neutral position and forge an independent course, he argued.

Amid such foment, the Iranian elite – aristocrats, merchants, and landowners who dominated the Majlis – shared power between themselves and the new shah, twenty-one-year-old Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, the first Pahlavi’s eldest son. Despite the dissent from the right and left, the elite directed most of their attention toward securing foreign patronage in the belief that balancing British and Soviet interests would allow Iran to remain nominally independent, a political philosophy known as “positive equilibrium.” Some saw the need to attract a “third force,” to counter the Anglo-Soviet presence. For a small clique led by the young shah, the United States of America seemed a natural choice. An American presence would balance that of the Soviets and British and permit Iran to retain its independence once the war was over.Footnote 63

President Franklin D. Roosevelt received the first Iranian request for assistance in January 1942. There were compelling strategic reasons to respond favorably. Protecting the “Persian Corridor” was a major wartime objective.Footnote 64 A larger American presence in Iran would facilitate “the steady transportation of American supplies to Russia.”Footnote 65 The British, who thought a US presence would strengthen their position in the oil fields, endorsed a more active American role in managing the supply line. Iran was filled with “reactionary politicians with unsavory reputations,” said the British ambassador. It could do with some political guidance.Footnote 66

While US troops helped manage the supply line, American advisors assisted the Iranian government manage the fallout from the occupation. Missions were sent for the army, which after the invasion had been left “demoralized, inefficient … and almost disintegrated,” and to the gendarmerie, the latter led by Colonel H. Norman Schwarzkopf, the former chief of the New Jersey State Police.Footnote 67 By 1943, there were missions assisting Iran’s government with everything from police training to grain distribution. Americans were in positions of authority throughout Iran’s administration. “We shall soon be in a position,” noted the State Department’s Wallace Murray, “of actually ‘running’ Iran.”Footnote 68

Americans found the country baffling. “There are so many different Irans,” wrote New Yorker correspondent Joel Sayre. Apart from missionaries who had traveled to Iran to establish schools or the occasional oil executive looking to crack the British monopoly, very few Americans visited Iran (or “Persia” as it was still widely known) before the war. Sayre described a country that fit the American image of a romantic Orient, but only from certain angles. The men in Western business suits walking the streets of Tehran, speaking Persian-accented French while smoking cigarettes and sipping coffee, bore little in common with the “ancient people” loading ass-carts near the port of Khorramshahr.Footnote 69 A guide for US Army personnel helpfully pointed out that Iranians “belong to the so-called Caucasian race, like ourselves,” and were to be treated with the courtesy and respect owed to white Europeans.Footnote 70 At the same time, Americans saw Iran as a place of backwardness, suffering from “the evils of greedy minorities, monopolies, aggression and imperialism,” according to Patrick J. Hurley, Roosevelt’s Middle East envoy.Footnote 71 There was an unmistakable sense of otherness attached to the country and its inhabitants that suffused official US discourse, particularly among those like Hurley who lacked any background in Iranian history, language, or culture.

For a time, American policy toward Iran was surprisingly ambitious, considering the country’s relative lack of importance to traditional US interests. Troubled by Iran’s economic distress and political instability, officials focused on two culprits: foreign imperialism and elite corruption. A report from the military attaché in November 1942 described Iranians as “appallingly illiterate,” led by a political class who welcomed US help “[to] save them from the British and Russians.”Footnote 72 Iran was riddled with mismanagement and graft, on the verge of “economic chaos and possible revolution.”Footnote 73 In an important State Department memorandum, Middle East specialist John Jernegan argued in early 1943 that Iran had fallen victim to imperialism and needed to be rebuilt with help from American experts, acting as a “test case” for a new foreign policy based on the principles of the Atlantic Charter. An aid campaign and expanded advisory missions could preserve Iran “as an independent nation … self-reliant and prosperous, open to the trade of all nations and a threat to none.”Footnote 74

For a time, such ideas found purchase at the highest levels of government. Hurley wrote in late 1943 that Iran required a course of “nation building,” with teams of US advisors reconstructing the Iranian administrative state from scratch.Footnote 75 Roosevelt, who paid more attention to Hurley than to his own State Department, visited Tehran for the Big Three conference in December and was struck by the rampant inequality, “[where] less than one percent of the population owns practically all the land.”Footnote 76 Egged on by Hurley, Roosevelt secured Churchill and Stalin’s signatures to a “Declaration for Iran,” which recognized “the assistance which Iran has given in the prosecution of the war,” and promised that once the war was over, Iran’s economic problems would be given “full consideration.”Footnote 77 It is unclear whether the British or Soviet leaders thought much of the declaration, but Roosevelt seemed to take it seriously. He confessed himself “rather thrilled with the idea of using Iran as an example” of what the United States could accomplish “by an unselfish foreign policy.” The president admitted the challenge was immense: “We could not take on a more difficult nation than Iran.”Footnote 78

Alarmed by the disorganization in Iranian state finances, the United States dispatched a large mission to assist the shah’s Ministry of Finance. The mission was led by Arthur C. Millspaugh. Among the many Americans sent to Iran during the war, Millspaugh was unique in the sense that he had real experience with Iranian internal affairs. Twenty years earlier, Millspaugh had served as financial advisor to the government of Reza Khan. From 1921 to 1927, Millspaugh reordered Iran’s budget, producing one of the first studies of the Iranian economy ever published in English.Footnote 79 Millspaugh arrived in Tehran in the wake of the 1921 coup, praised by Iranian newspapers as “the last doctor called to the death-bed of a sick person.” Millspaugh had mixed feelings about his new home. “A weak … immature country,” with a “primitive and medieval” economy dominated by “reactionary” elements, Iran seemed to struggle against the tide of history.Footnote 80 Millspaugh did not think Iranians racially inferior – “apart from the superficialities of dress and manner, they look, think, talk, and act like the rest of us,” he wrote. But he doubted the Pahlavi government’s ability to manage state finances efficiently, despite the “strong will” of its ruler. Finance was a “difficult piece of machinery for a representative government to operate,” and Iran appeared to lack “enlightened and effective public opinion in support of honest, efficient and law-observing administration.”Footnote 81

In 1942, Roosevelt’s State Department asked Millspaugh to return to Iran and resume his role as financial advisor. He took the assignment with considerable reluctance. Time and lingering bitterness over his ejection from Iran in 1927 had made Millspaugh cantankerous. He was more dismissive of Iran’s capacity for self-government than he had been twenty years earlier. “Morale is low among Iran’s young men,” he warned one Iranian diplomat. “They need someone who can protect them when they do good work and discipline them when they go wrong.”Footnote 82

Millspaugh arrived in Iran and set about reordering state finances as he saw fit. His team imposed rigid guidelines on the budget, mandating new rules in the bazaar and managing the nation’s financial affairs with little input from the Majlis or the shah’s ministers.Footnote 83 Millspaugh’s attempts to cut military spending irritated the shah, who regarded the army as his personal sphere of influence, while the mission’s proposed progressive income tax threatened the interests of the aristocracy and merchant class.Footnote 84 Bank-e Melli Governor, Abolhassan Ebtehaj, lambasted Millspaugh for taking over the country’s financial system and freeing up billions of rials for the importation of luxury items “like silk fabrics and toothbrushes.”Footnote 85 Millspaugh, in response, demanded the authority to fire Ebtehaj, who left for the Bretton Woods Conference in July 1944 promising to have Millspaugh removed as soon as he returned.

The drama surrounding the American advisor dominated Tehran’s press and limited the amount of work Millspaugh was able to accomplish. The growing anti-foreign chorus within Iran’s fractured political scene saw Millspaugh as emblematic of Iran’s continued weakness. In a fiery address to the Majlis on July 6, 1944, Mosaddeq declared the Millspaugh mission to be “incompatible with the constitution.” The Americans had taken control of the Iranian state, reducing the shah’s finance minister “to the status of an advisor,” and using their power to print “an unlimited quantity of notes,” causing inflation and hardship, Mosaddeq argued. If Millspaugh was not willing to subordinate himself to the government, he must step down.Footnote 86 In early 1945, the State Department bowed to Iranian pressure and withdrew its support for the financial mission, forcing Millspaugh to leave Iran.Footnote 87

The Millspaugh mission embodied an important element within the American advisor campaign. For all its idealism, the missions considered the Iranians as patients to be treated, rather than as equal partners. In Millspaugh’s view, Iran needed to be saved, both from the imperialists and from itself. Such direct intervention provoked a strong reaction among Iranians who were determined to limit foreign interference in internal affairs. All Iranians from the shah to administrators like Ebtehaj and nationalists like Mosaddeq opposed the Millspaugh mission. Though they recognized Millspaugh’s shortcomings and did not regret his departure, other American officials tended to find fault in his Iranian hosts. “The primary reason” for Millspaugh’s failure, concluded an embassy official in March 1945, “[was] a total lack of cooperation on the part of all classes of Iranians.”Footnote 88 The aristocracy had conspired against Millspaugh: “[C]orrupt and selfish political elements,” wrote one report, “stand to lose personally” had the advisor succeeded in passing his intended reforms.Footnote 89 This confirmed the belief, widespread among the Americans, that the Iranian elite stood in the way of the country’s reform and stability. “I am convinced,” wrote Ambassador Leland Morris, “that no influential group … desires foreign financial or economic advisors.”Footnote 90 The onus was placed on the Iranians themselves, who had shown “a regrettable lack of clarity,” by first requesting advisors and then rejecting them when they overstepped their authority.Footnote 91 The patient, in the American view, had turned away the medicine.

Though they drew on previous experiences by missionaries and financial advisors, the wartime missions constituted the first substantive form of development assistance offered by the United States to Iran. They began an era of engagement that would last more than twenty years. The experience, however, revealed several major sources of friction. For Americans, Iran appeared immature, unstable, and in need of foreign assistance. The key causes of its instability were imperialism, elite corruption, and administrative incompetence. These were not controversial points. Many Iranians, particularly among the educated middle-class, agreed that the country’s government was poorly run and there was widespread opposition to the influence of the British in the south and Russians in the north. But the American conception of Iranian incapacity would pose significant challenges to cooperation, both in the 1940s and in the future. While Iran appeared incapable of administering its own reform, indigenous reactions to direct assistance rendered the effectiveness of that assistance limited, as the Millspaugh mission illustrated. These elements imbued future American development endeavors with a distinctly ambivalent attitude – how to save a country if the inhabitants turned away your aid?

For these reasons, the missionary spirit proved fleeting. By 1945, the drive to assist Iran through advisors had dissipated. Figures like Hurley and Jernegan lost out to a group of policymakers – Dean Acheson, Loy W. Henderson, and a series of new US ambassadors to Iran – who were skeptical of advisors. Eugene Rostow scoffed at the missions as “an innocent indulgence in messianic globaloney,” while Acheson regarded Hurley’s program of assistance with deep suspicion: Sending out “indoctrinated amateurs, ignorant of the politics and problems of the Mohammedan world,” to transform countries like Iran seemed the height of folly.Footnote 92 There was nevertheless a recognition of Iran’s importance to American interests. As Roosevelt’s advisor, Harold Hoskins, noted in early 1945, the United States ought to increase its commitment to Iran’s progress, “not for any sentimental reasons,” but for the sake of national security.Footnote 93 Iran’s significance to the United States lay in its position athwart the world’s largest and most valuable oil fields. This view grew clearer once the context of an ideological struggle against communism solidified in 1946 – a conflict where Iran was to be an important battleground.

1.4 Oil, Iran, and the Cold War

As it entered World War II, US oil reserves equaled 46 percent of the world total. The United States accounted for two-thirds of global oil production.Footnote 94 Large domestic discoveries and access to oil in Latin America left the United States and the major US oil companies with enough crude to supply the domestic economy and fuel the global war effort. However, fears of a postwar shortage preoccupied policymakers. Consumption outpaced the rate at which new fields were discovered, and it was estimated the United States would become a net importer by the late 1940s. While there were initiatives that aimed at bringing the US government directly into the oil industry, wartime oil policy supported efforts by private companies to seek new concessions and secure reserves held overseas, in the hope that it would improve American energy security in the postwar period.Footnote 95

Conscious of the American interest in overseas oil, the Pahlavi government extended an invitation to the Standard Vacuum Oil Company (StanVac), a venture co-owned by Jersey Standard and the Standard Oil Company of New York (Socony), to offer a bid on areas outside the AIOC area in early 1943. Like the advisory missions, this was intended to draw in American support for Iran as a counter to the influence of the British and Soviets. “It has long been the wish of the Government,” explained Iran’s ambassador in Washington, “to have American companies represented in the development of Iran’s petroleum resources.”Footnote 96 The young shah, eager to obtain a more meaningful US commitment, insisted to the US charge d’affaires that they could count on his “sympathetic consideration,” noting how Iran “needs money badly.”Footnote 97 The thinking was straightforward: An oil concession would solidify the US presence and balance the AIOC concession in the south. It would also buttress state finances. While payments from AIOC still constituted less than 15 percent of the state budget, the oil industry had become an important source of foreign exchange. A concession, moreover, would be permanent, securing a lasting US commitment to Iranian independence – the policy of positive equilibrium in action.

The companies were interested. Both Jersey and Socony were “crude short”: They had plenty of markets (and would have more once the war was over), but not enough oil to feed them all. StanVac served as the companies’ distribution subsidiary in the eastern hemisphere and needed access to Middle East oil to meet postwar demand. Apart from a thin share of the concession in Iraq, neither Jersey nor Socony had access to Middle East reserves. The AIOC monopoly had vexed American companies for years – Jersey attempted twice in the 1920s and 1930s to break into Iran, without success.Footnote 98 But the companies demurred, waiting for State Department permission before sending executives to Tehran. Given the importance of preserving the Anglo-American alliance, there were risks involved in permitting US companies to enter Iran. Officials at the embassy warned that an oil concession would irritate the British and potentially trigger a Russian reaction.Footnote 99

Such concerns were ignored. The State Department “looks with favor upon the development of all possible sources of petroleum,” Secretary of State Cordell Hull told StanVac executives.Footnote 100 Hull, a fierce advocate for American commercial interests, believed further penetration of the Middle East by American companies would ensure postwar energy security. He was also interested in seeing oil form a part of the general US program to rebuild Iran. As he explained to Roosevelt, it was in the US interest that Iran be able “to stand on her feet without foreign control.” While the advisory missions would shore up Iran in the short-term, the nation’s independence would be ensured if the United States made its interest explicit through an oil concession. “From a more directly selfish point of view,” Hull wrote, it was in the interest of the United States “that no great power be established on the Persian Gulf opposite the important American petroleum development in Saudi Arabia,” where Socal and Texaco, two other US majors, were developing a concession.Footnote 101 Iran’s oil was important, but the country’s strategic location was arguably of greater importance. The desire to dominate Middle East oil compelled the United States to seek a concession in Iran.

The concession scramble played out in chaotic fashion. Royal Dutch/Shell, an Anglo-Dutch company, was another “crude short” firm with an interest in expanding its Middle East access. Shell executives arrived in Tehran in early 1944 and began approaching Majlis deputies, promising a concession with a $1 million lump-sum payment to sweeten the deal.Footnote 102 StanVac arrived in Iran to find Shell with a considerable head start. The situation grew more complicated when another US company, Sinclair Oil, joined the fray. As Shell had the most favorable negotiating position, the concession scramble sent off alarm bells among the more Anglo-phobic US officials fearful that American capital was about to get shut out. Persian Gulf oil constituted “the greatest single prize in human history,” wrote John Leavall, the petroleum attaché in Cairo, but British tampering had produced a situation “combining the worst features of feudal economy and capitalism.” Unless living conditions improved, oil nations of the Middle East would succumb to revolution, while American oil concessions “would cease entirely to be under our nation’s control.”Footnote 103 To Leavall’s chagrin, Hull would not back either StanVac or Sinclair, as an intervention might undermine the principal of free enterprise.

Before the Majlis could consider any of the new concession offers, a Soviet delegation arrived in Iran to discuss a concession covering the northern provinces. Where the Anglo-American proposals were commercial, the US ambassador believed a Soviet concession would function as an “agreement between states,” and cement Moscow’s control over Iran’s north.Footnote 104 The Soviet intervention worried the Iranians. Rather than open up the situation to a three-sided Great Power competition, Prime Minister Mohammed Sa’ed suspended concession discussions until after the war. Nationalist deputies led by Mosaddeq then pushed a bill through the Majlis that made it illegal for Iran’s prime minister to offer concessions until after the occupation – all foreign troops had to vacate Iranian territory before any new bids could be considered.Footnote 105 The move tied the government’s hands and halted the concession scramble.

With negotiations on hold, the Americans puzzled over the Soviet move. On the face of it, a Soviet oil concession in northern Iran made sense. The Soviet Union shared a border with Iran that was over 1,000 miles long. Soviet oil production was depressed due to the war and Moscow would need new sources to facilitate the postwar economic recovery.Footnote 106 Herbert Hoover Jr., the son of the former president and an oil advisor to the Iranian government, thought that the only natural market for Iran’s northern oil was the Soviet Union. If Iran wished to utilize this oil, it would have to do business with Moscow.Footnote 107 “The Russians are still suspicious of the US advisory program,” a report from the Office of Strategic Services concluded, while the Office of Petroleum Advisor determined that “pragmatic economic interest” motivated the Russian move.Footnote 108 Given their position in Khuzestan, the British were circumspect over the threat of a Russian concession. According to the ambassador in Tehran, there should be no objection, “provided that [the] concession is granted … freely and not under pressure.”Footnote 109 Britain was prepared to accept a permanent partition of Iran so long as it protected AIOC’s position.Footnote 110

The Soviet move in Iran prompted concern among a group of US officials who viewed communism as an existential threat to the United States and the postwar international order.Footnote 111 According to the charge d’affaires George F. Kennan in Moscow, “apprehension of potential foreign penetration” motivated Soviet policy. Iranian oil was important not as an economic asset, “but as something it might be dangerous to permit anyone else to exploit.”Footnote 112 Loy W. Henderson, head of the State Department’s Near East division and an ardent anti-communist, rejected the idea of entertaining Russian demands for a concession, “regardless of how reasonable,” and declared that the United States would not deal with the Soviets “behind the back of a small country.” In a long memo written in August 1945, Henderson insisted that the United States protect Iran from threats to its sovereignty, which he felt were “implicit in the Russian desire for access to the Persian Gulf.”Footnote 113 Wallace Murray, the ambassador in Tehran, felt a Soviet concession in Iran’s northern provinces would threaten “our immensely rich oil holdings in Saudi Arabia.”Footnote 114

Kennan emphasized Russian territorial ambitions in his famous “Long Telegram” from February 1946, suggesting that firm resistance to such advances would cause Stalin to reconsider. As the breadth of Soviet ambitions became clear after the Potsdam Conference of July 1945, Iran emerged as a point where the United States could resist the threatening spread of Soviet hegemony. In the words of historian Louise Fawcett, “In Eastern Europe it was already too late, in Iran it was not.”Footnote 115

Events in March 1946 appeared to justify American concerns. While British and American troops withdrew, Soviet forces remained and backed separatists in the northern province of Azerbaijan. Stalin told Tehran that the troops would leave once he was promised an oil concession. Officials at the US embassy warned of an imminent Soviet offensive while the American consul in Tabriz delivered panicked reports of a three-pronged attack on Iraq, Turkey, and Iran.Footnote 116 President Harry S. Truman perceived in the Soviet actions a “giant pincers movement against the oil-rich areas of the Near East.”Footnote 117 Ambassador to Iran George V. Allen warned that Iran could become a “Russian puppet state,” that “slavish Soviet tools and unscrupulous adventurers” might facilitate a coup d’état. The Persian Gulf would become a realm of “intense international rivalry … with control of all Middle East oil as one of the vital matters at stake.”Footnote 118 While the United States coordinated a response in the United Nations, the British considered ways to protect their position in the Iranian oil fields.Footnote 119 Defending AIOC’s profits was “imperative … for our commercial and economic well-being,” according to Defense Minister Emanuel Shinwell.Footnote 120 With the Soviets entrenched in Azerbaijan and the British determined to retain control over the oil fields of Khuzestan, Iran’s permanent partition loomed.

The Pahlavi government was not a passive participant in the crisis. Anxious to stave off further Soviet aggression, the shah’s Prime Minister, Ahmed Qavam, traveled to Moscow in April and met with Stalin personally. An experienced politician known for his intelligence and strength under pressure, Qavam flattered the Soviet leader, promised him an oil concession, and suggested turning Iran into a republic.Footnote 121 Having secured the Soviet promise to withdraw, Qavam returned to Tehran and publicly embraced the Tudeh Party, bringing several communists into this government. The prime minister, drawing on support from his followers in the Majlis, also drew up plans for an ambitious economic program. Before departing Moscow, Qavam convened a gathering of Iran’s most eminent economic minds in March 1946.Footnote 122 “The standard of living of the great masses of the Iranian people,” he declared, “though extremely low before the war, has become still worse.” He proposed that Iran launch a national program of economic revitalization. Offering another fig leaf to Iran’s communists, Qavam took a page out of the Soviet book and called his new program the Seven-Year Plan.Footnote 123

While he appeased Moscow, Qavam’s real plan was to maintain American support for Iran’s territorial integrity. He continued to meet with both British and American ambassadors throughout the crisis. His Seven-Year Plan, meanwhile, was part of a general push by the Pahlavi government to secure US financial assistance. “Patriots,” explained Ebtehaj to Ambassador Allen, were trying to save the country from Soviet conquest, and a US declaration of physical assistance would have “considerable moral effect.”Footnote 124 Ebtehaj signed a deal with an American firm, Morrison & Knudsen Inc., to prepare an economic survey on which the plan could be based. In October 1946 Husayn ‘Ala, Iran’s representative to the United Nations, sent a note to the International Bank of Reconstruction and Development – the US-backed financial institution better known as the World Bank – requesting a loan of $250 million for the new national development plan.Footnote 125 The shah repeatedly invoked Iran’s need for social and economic reform to Allen, while still pushing for an oil concession to balance the one Qavam would offer to the Soviets. Allen reported the odd spectacle of a foreign leader “begging Americans to take an oil concession.”Footnote 126 The Seven-Year Plan was a tool to lure American support back into Iran, after the failures of the advisory missions and the oil concession scramble.

The United States shifted to a stance of active containment toward the Soviet Union in 1946.Footnote 127 Yet there were doubts on whether direct assistance to Iran was prudent. Henderson thought that concrete aid for Iran was vital for preserving its territorial integrity. “Unless we show … that we are seriously interested” in assisting Iran, he concluded, the Iranian people would become “so discouraged that they will no longer be able to resist Soviet pressures.”Footnote 128 At the same time, means for assisting Iran seemed limited. The idea of an American oil concession had lost its appeal, with the State Department warning American oil executives to steer clear of Iran until the crisis over the Soviet concession had been resolved. Though the Soviet actions in Azerbaijan gave credence to the growing concern in Washington that confrontation with the Soviets was inevitable, the response of the Truman administration was cautious and focused largely on marshaling support for Iran in the United Nations.Footnote 129 In November, Assistant Secretary of State Dean Acheson assured Allen that the United States was prepared to furnish Iran with more military aid and would support its independence with “appropriate acts.”Footnote 130

The onset of the global Cold War clarified the US position on Iran, as it did with the Middle East in general. The region, though a British sphere of influence, was crucial for meeting the energy needs of the United States and the Western world as a whole. Iran, like the region’s other states emerging from various stages of colonialism, required support to ward off the threat of communism. Yet if US policymakers determined the need to assist Iran, they had not yet settled on a means. Both the advisory missions and oil concession search had proven to be dead ends. While Soviet forces left Iran and the shah’s troops successfully reoccupied the separatist province of Azerbaijan in December 1946, for the United States a definitive solution to the crisis – an answer to Iran’s state of instability – had not presented itself. Fortunately, at that moment the oil oligopoly came to the rescue, providing a solution tailored to the needs of the US government.

1.5 The Dual Integration of Iranian Oil

In late 1946, the global oil market stood on the verge of another crisis. Despite the rapid decline in military consumption, civilian consumption was set to rise dramatically, driven by demand for motor fuel and oil products for heating.Footnote 131 Prices rose and fears mounted that supply would be unable to meet demand. To secure the orderly exploitation of the major Middle East oil fields and prevent destructive competition, the largest oil companies came together for a series of accords historians would dub the “great oil deals.”Footnote 132

The deals were motivated by commercial concerns. The colossal abundance represented by the Middle East oil fields threatened markets with instability and overproduction, as most of it was in the hands of a few companies with inadequate market outlets. AIOC, for example, produced 408,000 bpd yet anticipated markets for only 224,000 bpd after the war.Footnote 133 Socal and Texaco, which together held the concession over Saudi Arabia, were in a similar position. Socony, Jersey Standard, and Shell all lacked oil for their markets, a commercial quandary that had driven them toward obtaining a concession in Iran in 1944. As competition loomed, the companies decided to share the spoils of the Middle East between them. The resulting agreements remade the global oil economy and imposed a form of international cartelization that would endure for nearly three decades.

Jersey Standard and Socony made a deal with Socal and Texaco for participation in Saudi Arabia, forming a new company, the Arabian American Oil Company (Aramco). Jersey and Socony also agreed to fund a pipeline with AIOC, in return for 134 million tons of AIOC crude purchased over twenty years. Shell secured a long-term contract for oil from Gulf, AIOC’s partner in Kuwait.Footnote 134 The companies were now bound up in mutual agreements to share Middle East oil among themselves: four US majors shared Saudi Arabia; Iraq was split among the US companies, AIOC, Shell, and a French firm; Kuwait was split between Gulf Oil and AIOC, while Iranian oil would now flow to Shell, Jersey, and Socony, thus ending their interest in an Iranian oil concession. As the largest and most mature Middle East oil producer, AIOC was guaranteed a market. Overall, the deals achieved what State Department officials called “orderly development,” along lines that were unmistakably cartelistic.Footnote 135 This process provided the oligopoly a firm basis for controlling the flow of oil in a way that would ensure profitability and mitigate competition. The deals also served American strategic interests and gave the United States an escape from its awkward position in Iran in the wake of the Azerbaijan crisis.

When news of the deals broke in late December 1946, Ambassador Allen was ecstatic. The deals would increase Iran’s revenue “and consequently contribute to the economic stability of Iran for which we are working.”Footnote 136 The deals meant that the United States could gracefully decline further entreaties from the shah regarding a US oil concession. On March 12, 1947, President Harry S. Truman promised US assistance to any friendly government threatened by communism.Footnote 137 Yet Iran would get no aid, for practical reasons. Despite Truman’s rhetoric and the preponderance of American power internationally, the United States had no interest in antagonizing the Soviet Union in Iran and did not wish to waste limited resources. Greece and Turkey were offered financial assistance. Iran, meanwhile, would have to subsist on oil revenues and loans from the World Bank.

Iran’s omission from the new US policy prompted a startled response from Qavam. Iran, he argued, “must have the strength and means of resisting … Communistic infiltration by raising the standard of life of the people.”Footnote 138 But Qavam’s entreaty fell on deaf ears. The prime minister was falling out of favor with US officials like Allen, who found the young shah a much more promising potential ally. Mohammed Reza Pahlavi scored a considerable moral victory in late 1946 when he led troops into separatist Azerbaijan, reclaiming control of the province. According to Allen, who played tennis with the shah once a week, the larger US goal of maintaining Iran’s “territorial integrity” could best be achieved through a policy that supported “[the] improvement of conditions of Iran’s workers and peasants” through the Seven-Year Plan. This would counter Soviet accusations that the United States supported “only [the] reactionary ruling class,” who Qavam seemed to represent.Footnote 139 The shah’s government, meanwhile, “has little to gain by granting us an oil concession,” wrote Under Secretary of State Robert A. Lovett, since Iran could now fund its postwar economic recovery through the funds provided by AIOC, “in harmony with the spirit of the Seven Year Plan of economic development,” formerly announced in March 1947.Footnote 140

AIOC had unexpectedly become the single most important factor in the Anglo-American campaign to build up Iran to the point that it could “stand on its own feet.” Given the company’s attachment to British imperialism and the rising petro-nationalist opposition within Iran, the US dependence on AIOC was very risky. The company pinned its future profitability on a steady expansion in Iranian production: From 1947 output was expected to increase 8 percent per year, reaching 40 million tons (816,400 bpd) by 1953. “Politically and strategically, Iran is at present the key to the whole Middle East,” wrote one company report.Footnote 141

As the British-owned oil industry increased in commercial and strategic importance, it grew into an important target for Iranian nationalists. According to one Iran Party member, after the Azerbaijan Crisis attention turned to the British oil concession, “the most important source of our national wealth and a source of pain for the country.”Footnote 142 In October 1947, the Majlis rejected the Soviet oil concession offer. At the same time, the assembly passed a bill prohibiting any new oil concessions and called on the government to examine Iran’s sovereign rights “in regard to the southern oil concession.”Footnote 143 The bill was a clear legal challenge to AIOC. Harold Pyman of the Foreign Office felt that the law would be used as the basis for some “tiresome” action against AIOC, which had also contended with a spike in labor militancy, including a major strike in July 1946, and growing public criticisms of its housing and welfare policies in the oil city of Abadan.Footnote 144

This rise in Iranian petro-nationalism elicited shrugs from American officials like Allen. There was likely to be “some difficulties” over the British concession, “but we shall ride them out as best we can,” he wrote, “without much damage.”Footnote 145 The fact that Iran had now outlawed the very idea of an oil concession did not trouble Allen. Once the Soviet threat to Iranian oil was resolved in late 1947, attention from Washington began to drift. Iran, in the British area of responsibility, would be left to “put its own house in order,” according to the State Department, with help from AIOC and other proxies.Footnote 146

1.6 Conclusion

Foreign control had been the hallmark of the Iranian oil industry since the days of the D’Arcy Concession. The oligopoly, acting through the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, solidified its hold over Iranian oil first by negotiating equitability and eventually through coercion, leaning on British military power to secure the oil fields of Khuzestan in 1941. The war opened up the Iranian state to the influence of American advisors, who had found Iran a baffling venue in which local nationalism and evident incapacity blunted the effect of direct assistance. The Pahlavi state, to ensure its survival, attempted to secure a lasting American commitment through an oil concession. But the United States avoided making its own commitment. By 1947, American policy in Iran was based on the expansion of Iranian oil production and the assumption that oil would help pay for Iran’s development. Assistance would come from proxies, the most important being the British oil company.

Local development and global oil were closely linked. Through AIOC and the oil deals of 1946, Iran was smoothly integrated into a postwar petroleum order that fed Middle East oil into the economic reconstruction of Western Europe and Japan – delivering oil to the Marshall Plan and generating stupendous profits for the oligopoly. The companies ordered the oil market as they wished, preserving the cartelization of the 1920s and ensuring profits while limiting competition. In the view of the Pahlavi government and its Great Power benefactors, oil wealth would help pay for the Seven-Year Plan, an indigenous development program which the Anglo-American powers would assist indirectly through private actors and proxies like AIOC.

Officials like US Ambassador George V. Allen doubted the weight of Iranian petro-nationalist attacks: “[T]he Iranian economy,” noted Allen, “made the uninterrupted exportation of oil a necessity.”Footnote 147 Consciously or not, Allen’s position mirrored that of John Cadman years before. The Iranians, the thinking went, needed the revenue from AIOC’s operations to carry out their economic development plan. They would never endanger such a lucrative source of income. Foreign control over Iranian oil resources formed a crucial part of the American strategy. It was only through the mechanisms of the companies and the management of the oligopoly that Iranian oil wealth could be ensured.

Similarly, US officials felt that foreign experts would be needed to guide Iran’s economic development plan. Allen spoke for many US officials when he observed Iran’s need for a “complete revolution … of management.”Footnote 148 John Jernegan, whose 1943 memo had suggested Iran as a test case for the Atlantic Charter, embraced a more authoritarian vision four years later, suggesting at one point that the United States back a “strong-man” to shepherd Iran’s development program, the Seven-Year Plan. “Iran is a backward country,” he argued, “and not fully prepared for democratic processes.”Footnote 149 The legacy of Millspaugh lingered within the new US policy, feeding a growing belief that Iran required foreign assistance or, at the very least, a strong central government in order to carry out successful oil-based development. By 1947 the basis of a new strategy in Iran had been established. American expertise would guide the plan, funded through the operations of the British oil company. Oil’s global expansion would power the local transformation of Iran and prevent its fall to communism. It was the dawn of dual integration.