This chapter will explore the archaeology of Early Anglo-Saxon settlement in England from the 5th through the 7th centuries CE. As we saw in Chapter 1, urbanism in Britain effectively ended sometime in the early decades of the 5th century. Here we will examine the nature of the settlements that were established in Britain in the 5th century and what they can tell us about social organization in early post-Roman Britain. Before we review the archaeological evidence, we will briefly examine the historical background to the Early Anglo-Saxon period.

Historical Background

The 5th century represents a major period of change in British archaeology and history. As we saw in Chapter 1, the diocese of Britain was no longer part of the Roman Empire after the early years of the 400s. Whether the emperor Honorius’s letter was addressed to the Britons or not, the removal of Roman troops in 407 essentially left the diocese on its own. It should not surprise us that many of the institutions that were put in place to support the Roman administration – including coinage, taxation, and urban centers – largely disappear along with the end of Roman political hegemony.

The nature of the early post-Roman world has been a subject of debate for centuries (see Wood Reference Wood2013 for a comprehensive review of this topic). As modern medieval archaeology has developed in the past 60 years, most of the early models were based on historical sources. The problem is that there are very few contemporary written sources for 5th- and 6th-century Britain. Of the major British sources – Gildas, Bede, and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle – only Gildas can be seen as broadly contemporary with the events he describes. Gildas was a British cleric who was probably born in northwest Britain, was educated in a classical tradition, and was writing in Latin in Wales, probably around 540 CE, although some authors would date this work as early as the late 5th century (see, for example, Higham Reference Higham1994, 141). Gildas’s De excidio et conquestu Britanniae (On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain) was meant as a sermon, condemning his contemporaries for the state of affairs in Britain at that time. The first part, however, provides a brief history of Britain from the time of the Roman conquest up until Gildas’s time. The Venerable Bede, who wrote his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Angelorum (An Ecclesiastical History of the English People) in the early 8th century, drew heavily on Gildas for his early history. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which was compiled in Wessex in the 9th century and survives in nine copies, probably incorporates written records from the 7th century onward but is not describing truly contemporary events until the reign of King Alfred. In short, the British historical record for the 5th and 6th centuries is very limited.

Moreover, as Barbara Yorke (Reference Yorke1990, Reference Yorke1993) has suggested, many of the documents that do survive were constructed to legitimate the kings who emerged in the late 6th and early 7th centuries CE. The documents provided genealogies for these early kings, usually going back to a pair of eponymous ancestors, whose names, like Hengist and Horsa, began with the same letter. They are not a reliable reflection of the history, in the modern sense of the word, of the 5th and earlier 6th centuries. If we use these documents as historical sources, we run the risk of treating these documents the way that Archbishop Ussher used the “begats” in the Old Testament to reconstruct the age of the world.

The British sources are supplemented by even more limited sources from the European continent. Prosper Tiro, writing in southern Gaul, reports that Germanus, the Bishop of Auxerre, visited Britain in 429 to combat the Pelagian heresy. Germanus also visited the shrine of St. Alban at Verulamium at that time. A Gaulish chronicler suggests that the provinces of Britain were subjugated by the Saxons in 441–2.

The British and continental sources were used to develop a picture of post-Roman Britain that remained the dominant narrative through the 1950s. The historical account can be summarized as follows. With the withdrawal of Roman military forces, the leaders of the diocese of Britain were forced to see to their own defenses. In order to protect Britain from external attack, a British leader, described by Gildas as a “proud tyrant,” invited the Saxons to settle in Britain. The Saxons turned on their hosts and overran the eastern part of the country. The British defeated the Saxons at the battle of Mons Badonicus, leading to a period of peace that seems to have prevailed in Gildas’s time, but eventually the Saxons conquered most of eastern England. The indigenous British population was slaughtered, forced west, or subjugated by the Anglo-Saxons. Bede (1.15) provides a particularly colorful description of the process:

[T]hese heathen conquerors devastated the surrounding cities and countryside, extended their conflagrations from the eastern to the western shores without opposition and established a stronghold over nearly all the doomed island. Public and private buildings were razed; priests were slain at the altar; bishops and people alike, regardless of rank, were destroyed with fire and sword, and none remained to bury those who had suffered a cruel death. A few wretched survivors captured in the hills were butchered wholesale, and others, desperate with hunger, came out and surrendered to the enemy for food, although they were doomed to lifelong slavery even if they escaped instant massacre. Some fled overseas in their misery; others, clinging to their homeland, eked out a wretched and fearful existence among the mountains, forests, and crags, ever on the alert for danger.

During the past 50 years, this traditional model has been challenged by archaeologists, historians, and, most recently, geneticists. The concerns raised include questions about the role of migration in the process, and even whether there was an Anglo-Saxon migration at all. Others have also questioned whether there are possible continuities between Late Roman Britain and Early Anglo-Saxon England, on the rural if not the urban level. Finally, geneticists have begun to examine the relative contributions of British and Anglo-Saxon males to the modern English gene pool and their implications for Anglo-Saxon settlement and social organization.

The question of the nature, scale, and existence of the Anglo-Saxon migrations to Britain is a particularly contentious one. The traditional historical model was a migrationist one, suggesting that the cultural and linguistic changes that appear in Anglo-Saxon England resulted from substantial population movement. While migration was seen as one of the classic causes of cultural change in the first half of the 20th century, migration was de-emphasized as a means of change in the 1960s as the theoretical focus in archaeology shifted away from culture history and toward more processual, ecological, and economic explanations for social change. In addition, as a result of two world wars, there was certainly a trend toward focusing on the British, rather than Saxon, antecedents of contemporary English society (Harke Reference Härke1998).

In recent years, this debate has been characterized as one between the “movers” and the “shakers” (Halsall Reference Halsall1999, 132; see also Wood Reference Wood2013, 310–12). The movers are those scholars who see the migrating peoples as a catalyst for social, political, and economic changes in the Late Roman and post-Roman world. The shakers, on the other hand, argue that tensions within the Late Roman Empire shook it to its foundations, and the barbarian invasions are simply symptomatic of larger internal problems.

Critiques of the 5th-century migrationist model take several forms. At a most basic level, historian Michael E. Jones (Reference Jones1998) argued that a close but literal reading of the historical texts would suggest that the Anglo-Saxons arrived in a relatively small number of boats. Jones (Reference Jones1998, 47) notes that Gildas tells us that the Anglo-Saxons arrived in three boats, followed by reinforcements. He sees Gildas’s account as a classic example of a mercenary revolt, and warns that “the small number of invaders described by Gildas must be treated seriously by the historian” (Jones Reference Jones1998, 53). Bede (1.15), following Gildas, tells us that the Angles or Saxons initially came to Britain in three long ships at the invitation of King Vortigern. Given what we know about pre-Viking watercraft, this would not involve a large number of immigrants (see also Higham Reference Higham1994, 41). Other estimates of the number of immigrants vary, but most range between the low tens of thousands and the low hundreds of thousands (Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Stumpf and Härke2006, 2651).

Other scholars have argued that what we may see is a classic example of elite dominance (Renfrew Reference Renfrew1987; Ward-Perkins Reference Ward-Perkins2000; Anthony Reference Anthony2007, 117–19; see Hills Reference Hills2003 for a comprehensive review of this issue). In this model, a small number of militarily successful Saxons may have led much of the rest of the population to emulate their success by adopting their language and material culture. The recently published cemetery at Wasperton in Warwickshire (Carver et al. Reference Carver, Hills and Scheschkewitz2009) provides the kind of data that can be used to support a model of acculturation. The cemetery, which was in continuous use from the 4th through the 7th centuries, shows burial rites that seem to reflect political, rather than demographic, changes. The cemetery begins with traditional 4th-century Roman burials. These are followed by what appear to be Christian burials in the 5th-century sub-Roman period. These are followed by Anglo-Saxon burials in the later 5th and 6th centuries. The earlier cremations from the later 5th and early 6th centuries show parallels with the Rhineland, while the later inhumations show links with East Anglia and Wessex. The burial rites in this frontier area seem to reflect the changing political dominance in the region. The inhabitants of the site, who were bread-makers during the Roman period, cast their lot with the Christians of western Britain in the first part of the 5th century, but shifted their allegiance to the dominant Anglo-Saxon polities by the 6th century.

K. Dark (Reference Dark2000) has argued for continuity of British power and influence throughout the 5th into the 6th century in both eastern and western Britain. While the case for British continuity in the west can be made on the basis of a range of historical, archaeological, and linguistic criteria (see previous chapter and below), the case for the same degree of continuity in eastern England is somewhat harder to make. Dark has argued that the areas that show an absence of early Pagan Anglo-Saxon cemeteries in the east are areas that were controlled politically and militarily until the English kingship begins to emerge in the late 6th century. Given the absence of settlement continuity in many urban and rural settlements in eastern England, Dark’s case remains unproved. However, the possibilities for long-term continuities in the use of the landscape (see, for example, Oosthuizen Reference Oosthuizen2016; see also Oostheuzen Reference Oosthuizen2017) would lend support to Dark’s model.

Recently, population geneticists have entered the fray. Using Y-chromosome data drawn from a sample of modern British males from central England and North Wales, Weale et al. (Reference Weale, Weiss, Jager, Bradman and Thomas2002) argued that the modern English population was indistinguishable from modern Frisians, but significantly different from the modern population of North Wales. They suggest that these data are best explained by a substantial migration of Anglo-Saxon males into England, but not Wales, in the immediate post-Roman period. While the data certainly show that modern English males are genetically different from modern males in North Wales, the assumptions used in this model and the conclusions drawn from it are more problematic. First, it is not clear that the modern population of rural North Wales can be taken as similar to the population of eastern England during the Roman period. North Wales has experienced substantial depopulation in modern times, and Wales also experienced substantial contact with Ireland in the early Middle Ages. The authors do not address the substantial genetic variation that is seen within the modern North Wales population. Second, the modern genetic data from central England were drawn from people living in small towns whose paternal grandfathers had been born in the same region. This was done as a way of minimizing the effects of migration to large towns and cities in the post-medieval period. However, as we shall see below, Early Anglo-Saxon England was non-urban, so this may not address issues of population movement in the early medieval period. The third problem is that massive migration may not be the only explanation for genetic difference. Other explanations for these data are possible. For example, Thomas et al. (Reference Thomas, Stumpf and Härke2006) suggest that an apartheid-like social structure that limited the reproductive opportunities for British males could also explain the genetic patterns seen by Weale et al. (Reference Weale, Weiss, Jager, Bradman and Thomas2002). Recently, Pattison (Reference Pattison2008) has suggested that a steady, small-scale flow of immigrants from northwest Europe could also explain the Y-chromosome data seen by Weale et al. (Reference Weale, Weiss, Jager, Bradman and Thomas2002) and Capelli et al. (Reference Cristian Capelli, Redhead, Abernethy, Gratrix, Wilson, Moen, Hervig, Richards, Stumpf, Underhill, Bradshaw, Shaha, Thomas, Bradman and Goldstein2003). In short, the genetic data can be interpreted to support either a migrationist model or an elite dominance model for the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons in southern and eastern Britain.

A recent study by Leslie et al. (Reference Leslie, Winney, Hellenthal, Davison, Boumertit, Day, Hutnik, Royrvik, Cunliffe, Lawson, Falush, Freeman, Pirinen, Myers, Robinson, Donnelly and Bodmer2015) has attempted to clarify the genetic issues by studying genome-wide SNP (single nucleotide polymorphism) data from 2039 individuals from the United Kingdom and comparing those data to genetic data obtained from over 6000 individuals from across western Europe. Their data provide clear evidence for an Anglo-Saxon migration, but they suggest that the proportion of Anglo-Saxon ancestry in the modern central and southern English population is likely to be between 10 and 40 percent (Leslie et al. Reference Leslie, Winney, Hellenthal, Davison, Boumertit, Day, Hutnik, Royrvik, Cunliffe, Lawson, Falush, Freeman, Pirinen, Myers, Robinson, Donnelly and Bodmer2015, 313). In addition, their data indicate that there was very little input from the Danish Vikings, despite their political control of parts of eastern England in the Late Anglo-Saxon period (Leslie et al. Reference Leslie, Winney, Hellenthal, Davison, Boumertit, Day, Hutnik, Royrvik, Cunliffe, Lawson, Falush, Freeman, Pirinen, Myers, Robinson, Donnelly and Bodmer2015, 313).

Chronological Issues

One of the critical issues archaeologists face in addressing questions of Early Anglo-Saxon settlement and the possibilities of continuities in settlement patterns from the Roman/sub-Roman period to the Anglo-Saxon era is the question of dating. As noted in the previous chapter, two of the materials that are commonly used to date Roman sites in Britain and elsewhere are pottery and coins. Both present serious problems when trying to date early 5th-century sites.

The last Roman bronze coins to have reached the diocese of Britain were those of the House of Theodosius (388–402). While it is certainly possible that some of these coins stayed in circulation after the first decade of the 5th century, there are good reasons to think otherwise. Low-value bronze coins would have served two principal functions in Late Roman Britain. First, they served an administrative function. They were used to convert between taxes in kind and taxes in coin and to pay for services. Second, they also served a commercial function in 4th-century Roman Britain. As Esmonde Cleary (Reference Esmonde Cleary1989, 96) has shown, when there was an acute shortage of bronze coinage during the 350s, there was extensive counterfeiting. Most of the copied coins appear to have been used for commercial transactions. No such copying took place after 402, indicating that coins were no longer needed for commercial purposes. Data from 140 Roman period sites in Britain show that coin loss increased substantially in the Late Roman period (Reece Reference Reece1995, 183; Gardner Reference Gardner2007, Fig. 3.8). While this increasing loss rate may reflect the more widespread use of coinage in commercial transactions during the 4th century, Gardner’s (Reference Gardner2007) study of Roman military sites shows that many Late Roman coins ended up in refuse contexts in the late 4th century. As Gardner (Reference Gardner2007, 79) notes, the presence of these coins in Late Roman refuse deposits may “suggest a tension between coins being more widely used than they were previously, and at the same time less worthwhile to keep – to the extent that many were thrown away.” These data suggest that early 5th-century Britain no longer had a monetary economy. Coins, therefore, cannot be used to date most 5th-century sites.

Pottery presents many of the same problems. Terra sigillata or “Samian” fine wares were imported into Britain from central and southern Gaul in the 1st and 2nd centuries. The chronology of this industry is well established, and many of these ceramics can be dated to within a decade or two. In the Late Roman period, a number of centers of pottery production were established in southern and eastern Britain. These kilns were generally located in rural locations, but were situated in places where they could provide fine wares to the civitas capitals (Esmonde Cleary Reference Esmonde Cleary1989, 91). Unfortunately, these production centers seem to have gone out of use at the beginning of the 5th century. While some Roman pottery sherds were found at Early Anglo-Saxon sites such as West Stow in Suffolk, the disproportionately high number of bases and their continued use into the 6th century suggest that these pots may have been selectively chosen from a rubbish deposit and that this scavenging continued for an extended period (Plouviez Reference Plouviez1985, 85).

Given the problems with using Late Roman coins and pottery to date the 5th-century sites in Britain, most chronologies have been based on artifact typologies, and particularly on comparisons to better-dated material from the European continent. Dendrochronology has played a role in areas where waterlogging has led to the preservation of wood, but its role to date has been relatively limited. Until recently, radiocarbon dating played a relatively minor role in dating Early Anglo-Saxon sites. Traditional methods of radiocarbon dating require large samples (generally at least 25 grams of material) and often produce standard deviations that are too large to be useful in what is a historical time scale. As noted above, the advent of AMS dating in the 1980s, which allows archaeologists to date smaller samples, and with the development of better methods for preparing and cleaning samples, radiocarbon dates are playing an increasingly important role in Anglo-Saxon archaeology. For example, a series of carefully selected radiocarbon samples from the ostensibly Late Roman cemetery of Queenford Farm and the nearby Early Saxon cemetery Berinsfield in Oxfordshire allowed Hills and O’Connell (Reference Hills and O’Connell2009) to show that the cemeteries had been used sequentially rather than concurrently. The radiocarbon dates indicated that the Queenford Farm cemetery was primarily in use during the 4th century, while the Berinsfield cemetery was in use from the 5th to the early 6th century. If the two cemeteries had been contemporary, they might have provided some support for the apartheid-like model for Anglo-Saxon social organization. Instead, these data suggest that the native population in the region adopted Anglo-Saxon burial customs in the 5th century.

Despite the chronological problems that plague the archaeology of the 5th century, the archaeological data suggest that much of the diocese of Britain went through a process of de-Romanization in the late 4th and early 5th century. As we saw in Chapter 1, this is much more than a political change. Not only were the Roman troops withdrawn from Britannia, never to return, but the Roman towns and villas were depopulated as well. Smaller British polities survived in the west, in places such as Wroxeter and Congresbury–Cadbury, but by the end of the first half of the 5th century, Britain had largely ceased to be Roman. This chapter will explore the nature of the settlements that replaced the towns, villas, and small rural settlements in eastern England during the 5th century.

The Archaeology of Early Anglo-Saxon Settlement

One of the problems facing archaeologists who study Early Anglo-Saxon settlement in Britain is that relatively few Early Saxon settlements have been excavated to a modern standard, and even fewer have been completely published. While somewhere between 30,000 and 40,000 Pagan Anglo-Saxon burials have been discovered in Britain, there are probably only a few dozen 5th- and 6th-century settlement sites that have been excavated in any detail, and only a handful of those have been comprehensively published.

The earliest large-scale excavation of an Early Anglo-Saxon settlement was undertaken by E. T. Leeds at the site of Sutton Courtenay in Berkshire (Leeds Reference Leeds1923, Reference Leeds1926–7, Reference Leeds1947) (see Figure 2.1). In the 1920s, Leeds salvaged about two dozen sunken-featured buildings (SFBs) from gravel quarrying. These structures, known as grubenhäuser on the European continent, are generally rectangular with rounded corners. They are sunk about a half meter into the earth and are marked by one, or sometimes three, postholes at either short end. While Leeds identified a small number of postholes, he did not identify any posthole structures other than the grubenhäuser, and he assumed that these sunken-featured buildings served as the dwellings for the Early Anglo-Saxons.

Figure 2.1. Map of southern Britain showing the locations of the Anglo-Saxon sites discussed in this chapter. Drawn by Douglas V. Campana using open-source software.

The first Early Anglo-Saxon settlement to have been extensively excavated and published was West Stow in Suffolk (Figure 2.2) (West Reference West1985). The West Stow site is located in the Lark River valley in the Breckland region of northwest Suffolk, near Bury St. Edmunds. The site was associated with a cemetery which was discovered in the course of gravel digging in the 19th century. More than 100 graves, including both inhumations and a few cremations, were excavated in the 1840s and 1850s. The excavations recovered 151 objects, plus beads, but the quality of the recording is so poor that the individual grave groups cannot be reconstructed.

The West Stow settlement site was discovered by Basil Brown in the 1940s, and preliminary excavations took place there under the direction of Vera Evison in the late 1950s. Major excavations were carried out at the West Stow settlement by Stanley West between 1965 and 1972 (West Reference West1969, Reference West1985). West had attended Cambridge University at a time when the theoretical focus of archaeology was shifting toward questions of economy, technology, and environment, so the focus of the excavation was on the recovery of material that could be used to reconstruct Early Anglo-Saxon settlement patterns and subsistence technology. For example, flotation techniques, which were being developed while the excavation was ongoing, were used at the site in 1972 (Murphy Reference Murphy and Rackham1994).

Excavations at West Stow uncovered 69 sunken-featured buildings clustered around seven small “halls,” spread across an area of about 1.8 ha. Unlike Leeds, West (Reference West1985, 116–18) argued that the bottoms of the SFBs were not living floors. Instead, the excavations at West Stow suggested that the pits were covered by larger, suspended timber floors. The reconstructions of these dwellings can be seen at the West Stow Anglo-Saxon village today (Figure 2.3). The halls are rectangular post-built structures that are generally less than 10 m in length, far smaller than similar structures on the continent (West Reference West1985, 19). Detailed chronological analyses indicate that only about three of these settlement clusters would have been in use at any one time. The halls were interpreted as the main dwellings for each cluster, while the sunken-featured buildings served as outbuildings such as workshops and barns. West (Reference West1985, 168–9) suggested that the site was probably occupied by three extended families throughout most of its history.

Figure 2.3. Reconstructed sunken-featured building at West Stow County Park. The program of reconstruction began in 1974.

Initial analysis suggested that the site was first occupied in the early 5th century, and that it was abandoned around the middle of the 7th century CE. A small number of sherds of Ipswich ware were recovered from the fills of some of the latest of the SFBs. Other fragments of Ipswich Ware were recovered from the ditches and from the general cultural layer, known as “Layer 2.” Reanalysis of the chronology of Ipswich Ware indicates that it was not produced until about 700–20 CE (Blinkhorn Reference Blinkhorn and Anderton1999, Reference Blinkhorn2012). This means that the West Stow settlement must have survived into the early 8th century, adding at least 50 years to the settlement’s history. West (Reference West2001), however, notes that the longer chronology is inconsistent with the experimental data on the lifespans of the timber buildings.

West (Reference West1985, 167) believed that he had excavated the total Early Anglo-Saxon settlement at West Stow. However, recent discoveries have also challenged West’s view of West Stow as a small hamlet that was probably occupied by no more than three extended families at any one time. Rescue excavations were carried out in 2007 in advance of the construction of a new gift shop for the visitors’ center at the West Stow site (Gill et al. Reference Gill, Goffin and Carruth2015). These excavations, known as West Stow West, identified six additional sunken-featured buildings and a posthole structure, indicating that the site may have been much more extensive than was originally thought.Footnote 1 With these new discoveries West Stow looks more like the other sprawling Anglo-Saxon settlements that were established in the 5th century.

The long-term programs of excavation at West Stow allow us to say something about the way the Early Anglo-Saxons made use of the Lark Valley environment. The settlement itself was located on the river terrace. This terrace area also would have provided fields for agriculture and some limited woodland with pannage for pigs. The rich grazing areas closer to the river were probably used by cattle. The Lark River would also have supplied freshwater fish, and it was home to aquatic birds such as ducks. The upland areas of the Breckland region would have been ideal for grazing sheep and a few goats. The distribution of known Anglo-Saxon finds in the Lark Valley suggests that these settlements were strung out along both sides of the river. This settlement pattern would have given each farmer access to the rich pastures of the Lark Valley, the farmland and woodland along the river terraces, and the upland grazing areas.

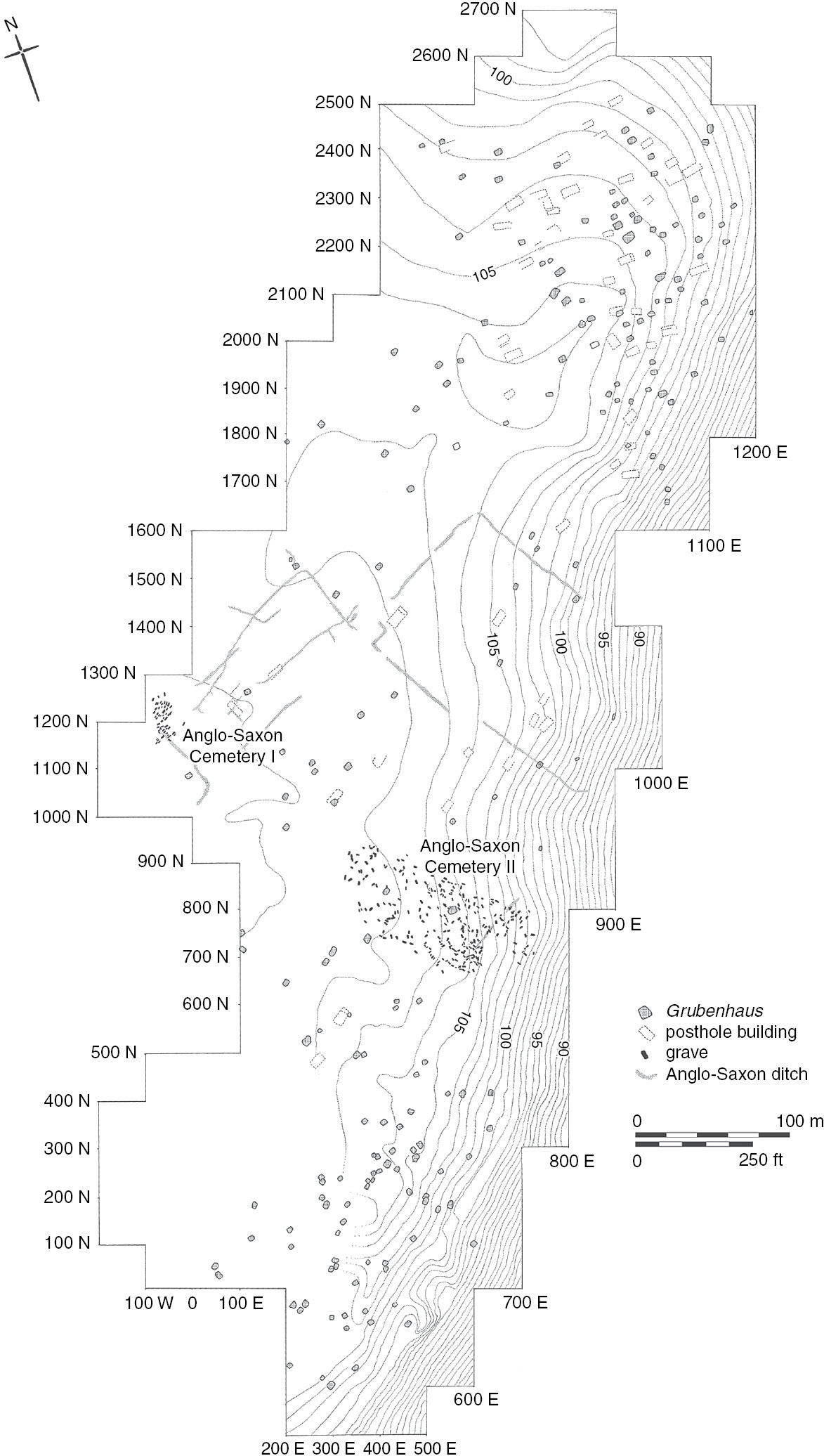

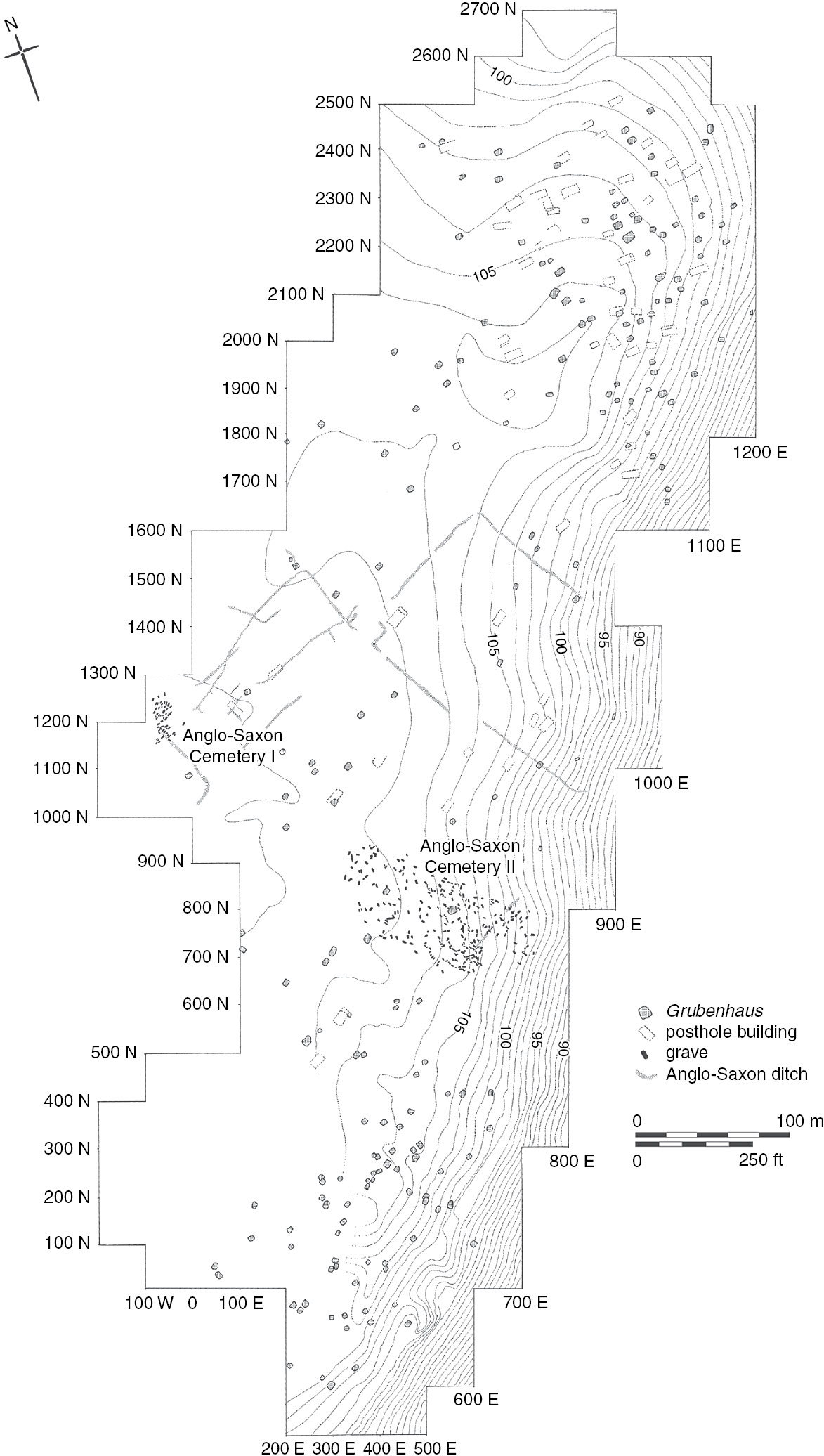

The most extensively excavated and fully published of the Early Anglo-Saxon settlements is the site of Mucking in Essex (Hamerow Reference Hamerow1993; Hirst and Clark Reference Hirst and Clark2009). Crop marks seen from the air initially revealed the archaeological potential of the Mucking site, which is located on the 100-meter gravel terrace overlooking the Thames estuary (Hamerow Reference Hamerow1991, 3). The site was excavated by the late M. U. and M. T. Jones, but the results have been published by other scholars. Excavations revealed two Pagan cemeteries, 53 posthole buildings, and 203 grubenhäuser spread over 18 ha. The site was continuously occupied from the first half of the 5th century through the late 7th or early 8th century.

Two models for the settlement history have been proposed. The first by Hamerow (Reference Hamerow1993, 86–9) suggests that the Mucking settlement is made up of a series of farmsteads whose locations shifted around the two cemetery sites (Figure 2.4). Ancestral ties to the cemeteries explain why the Early Anglo-Saxons continued to inhabit this relatively inhospitable site, although it may have been initially chosen for its strategic location overlooking the Thames.

Tipper (Reference Tipper2000, Reference Tipper2004) suggested an alternative model based on the re-study of the ceramic and the settlement data. He suggested that there was a single nucleus of settlement in the 5th century located in the southwest area of the site. This was augmented by a secondary settlement at the north end of the site which was first established in the 6th century. While Hamerow saw the settlement as shifting throughout the Saxon period, Tipper suggested that two separate and stable communities, separated by the cemeteries, occupied the terrace area during the 6th and 7th centuries. Tipper also noted the three ditched enclosures in the central area of the settlement, which probably date to the late 7th to early 8th century, and suggested that they may have been associated with the contraction of the settlement at the end of the Early Anglo-Saxon period (Tipper Reference Tipper2004, 37–9). Similar ditches have been identified from the final phase at West Stow (West Reference West1985, 54), some of which contained Ipswich Ware, indicating that they were filled in the early 8th century. These data hint at the changes in land tenure and/or organization that seem to have taken place at the end of the Early Anglo-Saxon period. Hirst and Clark (Reference Hirst and Clark2009, 445) note that after Mucking was abandoned in the late 7th or early 8th century, the site reverted to agriculture and that the subsequent field system developed out of these 7th–8th-century ditched enclosures.

A third large Early Anglo-Saxon site has been excavated at West Heslerton in Yorkshire. The site has been extensively surveyed and excavated under the direction of Dominic Powlesland, but it remains incompletely published (Powlesland et al. Reference Powlesland, Haughton and Hanson1986; Powlesland et al. Reference Powlesland1998; Powlesland Reference Powlesland, Hawkes and Mills1999, Reference Powlesland, Geake and Kenny2000). The site is located on the south side of the Vale of Pickering and at the foot of the Yorkshire Wolds (Powlesland Reference Powlesland, Hawkes and Mills1999). Excavations were carried out at the settlement between 1986 and 1995. The site shows some 4th-century Late Roman activity, principally associated with the ritual use of a spring. The Early and Middle Anglo-Saxon features are distributed over 13 ha and include 130 grubenhäuserand 90 posthole structures, plus a cemetery that was excavated earlier (Powlesland et al. Reference Powlesland, Haughton and Hanson1986; Powlesland Reference Powlesland, Hawkes and Mills1999).

The Anglo-Saxon settlement was discovered in 1982 in an area that was experiencing damage from plowing. A spring located in the center of the south half of the settlement was the setting for the construction of two shrines in the 4th century. The presence of some very Late Roman or sub-Roman pottery suggests that the shrine remained an important ritual location into the early 5th century.

The stream, which is fed by the natural spring, formed the focus of the Early Anglo-Saxon settlement. The layout of West Heslerton shows some zoning that is not apparent at either West Stow or Mucking. There appear to be distinct areas of the site dedicated to housing, crafts, and agricultural processing. No boundary lines or ditches are apparent in the northern half of the settlement. The northeast appears to have served primarily as a dwelling zone, and posthole structures or “halls” dominate in this area. A high concentration of grubenhäuser are located to the west of the stream channel. As is the case at West Stow, these structures seem to have been covered by a wooden floor. Powlesland (Reference Powlesland, Hawkes and Mills1999) and his colleagues interpret this as an area devoted to crafts and agricultural processing. In addition to crop storage, crafts carried out in this area include spinning, weaving, metal-working, animal processing and butchery, and possibly bone-, leather-, and horn-working. There is no evidence to suggest that these crafts were carried out on a large scale. Rather, they seem to represent local production for local consumption.

The southern part of the settlement has a very different layout. Extensive enclosures are visible on both sides of the stream. These enclosures appear to have been built in the Late Roman period, and their layout was maintained throughout the Early Anglo-Saxon period. They are marked by ditches and slots for fencing. During the Middle Saxon period, when settlement contracted to the Late Roman core of the site, new enclosures and boundary ditches were constructed. Powlesland (Reference Powlesland, Hawkes and Mills1999) has suggested that the Middle Saxon settlement may represent an early manor. Coin evidence suggests that the site was abandoned around 850 CE.

The excavations at West Heslerton raise two interesting questions for the study of early medieval urbanism. The first, of course, is the question of Roman-to-Saxon continuity at the site. The site was clearly used in the late 4th century, and probably into the early 5th century, as a shrine. Its location at a spring is not surprising, since many Roman and pre-Roman ritual sites are located at springs and other aquatic features. Powlesland (Reference Powlesland, Hawkes and Mills1999) dates the Early Anglo-Saxon settlement to ca. 475–675 CE. Whether the late 5th-century inhabitants represent Romanized Britons, immigrant Anglo-Saxons, or some combination of the two, what we see at West Heslerton is clearly not continuity in Roman urban settlement. Other questions of Roman–Saxon continuity will have to await the full publication of the excavation.

A second and more critical question is whether the ordered layout of the site represents a type of “proto-urban” settlement in the Early Anglo-Saxon period. Powlesland (Reference Powlesland, Hawkes and Mills1999) asks whether the zoning and planning seen at West Heslerton represent a failed Early Anglo-Saxon attempt to establish sites of a more urban nature. He further wonders whether this was part of a broader trend toward Early Saxon urbanism which could not be sustained. While we await the final publication of the site, I think that the answer to these questions should be an emphatic no. While there is certainly evidence for settlement planning and zoning at West Heslerton, there is no clear evidence for substantial craft specialization. As Powlesland (Reference Powlesland, Hawkes and Mills1999, 62) notes, there is no evidence for large-scale textile production at West Heslerton. Similar evidence for small-scale textile production has been recovered from other Early Saxon sites, including West Stow and Kilham in East Yorkshire (Hunter-Mann Reference Hunter-Mann2000, Reference Hunter-Mann2001). In many ways, the zoning we see at West Heslerton presages the kinds of zoning we see in some later Early Saxon and Middle Saxon rural settlements. For example, at Brandon in Suffolk (Tester et al. 2014, 372–4; see Chapter 3) there is clear evidence for a waterfront industrial zone where activities such as textile production took place.

Moreover, there is no evidence that the site of West Heslerton was providing services to a broader hinterland. While the lava querns provide some evidence for long-distance trade (see below), there is no evidence to suggest that West Heslerton was a focal point for broader trade in these imported items or that it served as a market for the surrounding countryside. The planning clearly points to some degree of leadership, but that should not surprise us. Historical and archaeological evidence both indicate that leadership was a feature of both native British and Anglo-Saxon societies.

What conclusions can be drawn about Early Anglo-Saxon settlement from the large-scale excavations at West Stow, Mucking, and West Heslerton? All three appear to be rural settlements of substantial size that include both post-built structures and grubenhaüser. The small “halls” appear to have served as dwellings, while the sunken-featured buildings were used as workshops and storage facilities. While these sites appear to have made use of the Roman landscape, there is no clear continuity in residential settlement. West Heslerton is built around what was a Late Roman ritual site. The West Stow settlement is located on an unoccupied site, although it is close to the Late Roman settlement of Icklingham. There was also a Late Roman settlement in the area of Mucking, although the Roman material from the site has not yet been fully published. In addition, Cemetery II at Mucking was bounded by Roman enclosure ditches on both the north and the south (Hirst and Clark Reference Hirst and Clark2009, 759). This may suggest continuity of land use or land tenure, even if there was no obvious continuity of settlement.

The economic data from these sites point to a degree of autarky or economic self-sufficiency (Crabtree Reference Crabtree2010b). While the faunal data from Mucking are limited due to poor preservation, and the data from West Heslerton have not been fully published, the extensive faunal collection from West Stow indicates that animal husbandry was not geared toward specialized products for exchange (Crabtree Reference Crabtree1990). Faunal collections from a range of smaller Early Anglo-Saxon sites, including Quarrington in Lincolnshire (Rackham Reference Rackham2003) and Kilham in East Yorkshire (Archer Reference Archer2003), reveal an Early Anglo-Saxon economy that is unfocused and designed to produce a range of products, such as meat, milk, wool, and traction, for local consumption. Gerrard (Reference Gerrard2013, 13) has recently argued that Late Roman farming communities were overproducing crops to meet the demands of the Roman state. When these demands disappeared in the 5th century, the agropastoral system changed to one that was focused on less intensive forms of agricultural production such as cattle and sheep pastoralism.

A recent study of Anglo-Saxon deer hunting (Sykes Reference Sykes2010, 178) shows that Early Anglo-Saxon sites, including West Stow, tended to include a high proportion of meaty body parts. This is consistent with animals that were butchered at the kill site and whose low-utility parts were discarded there. Only the meat-bearing bones were carried back to the settlements. Hunting was not a common practice, and it was carried out as a means of risk reduction, rather than as a means of social differentiation. In short, hunting served as a dietary supplement at times when other food sources may have been running low.

While subsistence practices were focused primarily on local needs, this does not mean that these sites were isolated and cut off from local, regional, and international trade networks. The presence of Neidermendig lava for quern stones at West Heslerton (Powlesland Reference Powlesland1998) in both Early and Middle Saxon contexts points to trade with the continent, although whether this trade was direct or indirect is not known. At a regional level, the presence of a marine flatfish in 6th-century contexts from West Stow indicates trade and contact with the coast (Crabtree Reference Crabtree1990, 27), and the presence of a beaver incisor may indicate contact with the fenland region. By the mid- to late 6th century, Illington-Lackford pottery appears at a series of settlement and cemetery sites including West Stow in a 900 square km region in East Anglia. The pottery is marked by distinctive stamps and designs, and it is the first standardized pottery to appear in post-Roman Britain. Its presence at West Stow and other contemporary East Anglian sites also points to local and regional exchange, although this may have taken one of a number of forms, including trade, gift exchange, and redistribution by a local leader (Russel Reference Russel1984, 528; Hamerow Reference Hamerow and Fouracre2006, 279). If the latter is the case, then craft specialists may have been attached to local leaders, rather than itinerant or independent crafts workers.

Another striking feature of the settlement evidence from the 5th and early 6th century is that the architecture and settlement layouts show little evidence for differences in status or wealth. All the dwelling units appear to be made up of a small, central hall surrounded by a series of sunken-featured buildings that served as outbuildings. There is no clear evidence for high-status or low-status dwellings before the late 6th century. As Hamerow (Reference Hamerow and Christie2004, 307) notes, status does not appears to be expressed by the ability to support large numbers of people in a single household.

Many of these Early Anglo-Saxon settlements have little in the way of boundaries. While some possible animal pens are present, there are no enclosures around buildings or sets of buildings before the late 6th century at the earliest (Hamerow Reference Hamerow and Christie2004, 307). For example, the ditches that are visible at West Stow can be assigned to the final phase of the settlement. That phase was initially dated to the late 6th–7th centuries CE. However, a number of these ditches include Ipswich Ware, which suggests that they may be as late as the early 8th century CE. The settlements are also somewhat mobile; dwellings are not rebuilt in the same place, although at West Heslerton there are examples of replacement buildings that are adjacent to earlier buildings (Powlesland Reference Powlesland, Geake and Kenny2000, 24). The individual dwellings are generally not surrounded by fences, ditches, or other territorial markers.

The question of the nature of the society that inhabited these sites is an interesting one. The excavators of both West Heslerton (Powlesland Reference Powlesland1998) and West Stow (West Reference West1985) do not see these settlements as high-status communities. Higham (Reference Higham2004, 15–16), however, suggests that the quantity of artifacts recovered from West Stow, and probably West Heslerton, is too large to have been produced by an economy based primarily on subsistence farming. He notes that the excavation at West Stow produced, among other things, 66 iron knives, a large number of spindle whorls and loom weights, and a range of other metal items including arrowheads, shield bosses, and brooches. Powlesland (Reference Powlesland1998) reports that the larger West Heslerton site produced over 200 iron knives, plus additional fragments. Higham seems to imply that the denizens of West Stow and probably West Heslerton must have relied heavily on tribute to support their lifestyles. There are three problems with this argument. First, knives would have served a variety of functions, from eating utensils to butchery tools to weapons, in Early Anglo-Saxon society. It is not unreasonable to assume that the community of West Stow discarded 66 knives over a period of almost 300 years. The second is that smaller Early Anglo-Saxon sites, such as Quarrington and Kilham, seem to show the same economic patterns as those seen at West Stow. The third is that there are good continental models for Migration Period sites that rely primarily on tribute. At sites such as Gennep (Heidinga Reference Heidinga, Nielson, Randsborg and Thrane1994, Reference Heidinga and Crabtree2001) in the Netherlands, the inhabitants appear to have subsisted primarily on tribute. The site provides extensive evidence for hunting and metal-working, but the evidence for animal husbandry and agriculture is limited to horse breeding. At West Stow, the evidence for hunting is limited, and the presence of neonatal and young juvenile cattle, sheep, and pigs indicates that animal husbandry was taking place on site.

No one, however, would argue that Early Anglo-Saxon sites and communities were egalitarian. The variations seen in the quantities and quality of grave goods in the large inhumations and cremation cemeteries point to a society that had significant differences in social status, political power, and material wealth. The problem is that we have almost no historical evidence about the nature of 5th- and 6th-century Anglo-Saxon society. A number of authors have noted that many of the 7th-century Anglo-Saxon kingdoms are similar in area and geographic extent to the pre-Roman Iron Age tribal territories in Britain. Higham (Reference Higham2004, 8) notes that the territory of the Trinovantes is remarkably similar to the territory of the 7th-century East Saxons. However, the question of whether there was a degree of continuity in political administration at the local level is far more difficult to answer. For example, we do not know the structure and extent of a single Roman estate, so it is difficult to determine whether any of these estates, or any smaller land units, may have passed into Saxon hands. Moreover, there has been a tendency to project the social and political structure known from 7th- and 8th-century England back onto the 5th and 6th century, even though it is likely that Early Saxon England, as well as sub-Roman Britain, was made up of a series of smaller and more loosely organized polities.

Archaeological and landscape data from West Sussex provide some evidence to support the presence of these smaller 5th- and 6th-century polities (Semple Reference Semple2008). Graves and cemeteries in this region were located along crests of escarpments and on edges of rough pasture overlooking the coast, the estuary, and the rivers (Semple Reference Semple2008, 417). Both primary and secondary barrows were located so as to dominate entry points into west and central Sussex (Semple Reference Semple2008, 420). Semple (Reference Semple2008, 423) has argued that these funerary monuments define a series of small, river-centered polities that emerged in the political chaos of the post-Roman period. That these small polities are centered around river valleys is particularly significant, since McCormick (Reference McCormick2010) has argued that one of the most significant changes in transportation during the 5th century was the change from land-based transport during the Roman period to water-based transport in the post-Roman era.

If we imagine that much of eastern England was made up of small, river-based polities in the 5th and 6th centuries, then there is no need for the substantial food rents that characterized the 7th and 8th centuries CE. In the Middle and Late Anglo-Saxon periods, the king and his followers “ate” their way through their kingdoms. A possible Middle Saxon food-rent collection site has been identified as Higham Ferrers, Northamptonshire (Hardy et al. Reference Hardy, Charles and Williams2007). In the 5th and 6th centuries, it is likely that chiefs, war leaders, and retainers could move through their entire kingdoms in a matter of days, and the burden of taxes and tribute is likely to have been much less. As Hamerow (Reference Hamerow and Christie2004, 307–9) has suggested, “the seventh and eighth centuries seem truly to be the period when, at least in southern England, settlements became more firmly inscribed onto the landscape as both secular and religious landlords extended growing influence over their estates.”

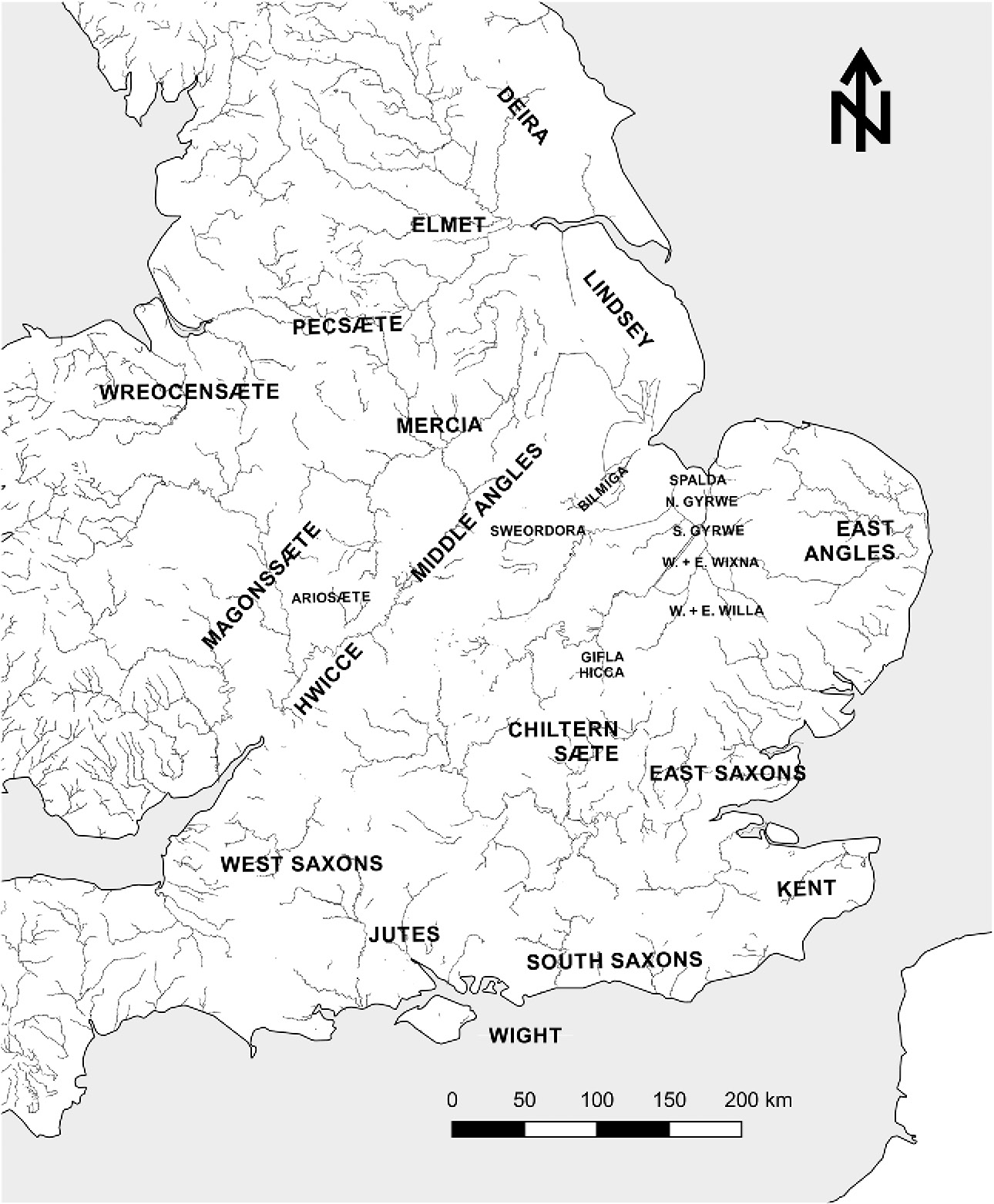

If the west Sussex model can be extended to other parts of eastern England, it suggests that we are looking at a region made up of a patchwork of small polities. Some of these polities appear to have survived into the Middle Anglo-Saxon period (7th–9th centuries CE), since they appear in the Tribal Hidage, a document that seems to be a tribute list for the emerging Mercian kingdom in the Midlands (Figure 2.5). It is also likely that these small polities could unite for purposes such as warfare and raiding. For example, Yorke (Reference Yorke, Goetz, Jarnut and Pohl2003) has suggested that the Angles and Saxons may have been confederations or gentes in 5th- and 6th-century Britain. Small British polities also existed in the regions outside the initial Anglo-Saxon settlements.

Figure 2.5. Anglo-Saxon polities at the time of the Tribal Hidage, probably in the late 7th century. Redrawn after Yorke (Reference Yorke1990, Map 1, p. 12), with permission of the author.

Many of the known Early Anglo-Saxon settlements are located on comparatively marginal land, such as breckland and gravel. While those who would see substantial continuity in post-Roman rural settlement might argue that the better lands were already taken by native British farmers, it is equally possible that these lands were chosen for non-agricultural reasons. Moreover, while these areas may not have been ideal for the intensive cereal and livestock farming that was practiced during the Roman period to meet the needs of the towns and the military, they would have been appropriate for more extensive subsistence practices that were designed to meet local needs. This is consistent with the pollen data from East Anglia, which provide no evidence for woodland regeneration in the post-Roman period, but which suggest a decline in cereal agriculture in favor of stock-raising.

The archaeological data suggest that for most of the 5th and 6th centuries CE Britain was a rural society. The towns and cities of Roman Britain were depopulated, and Anglo-Saxon settlements that were established between 450 and 550 were strikingly non-urban in character. While towns and cities were seen as essential elements of Roman culture and worldview, it might be argued that cemeteries played a more prominent role in Early Anglo-Saxon society. Lucy (Reference Lucy2000, 152) notes that cemeteries are located on high ground while settlements are located in more sheltered valley regions. While Early Anglo-Saxon rural settlements like West Stow and West Heslerton were occupied throughout the entire Early Saxon period, by the end of the 6th century we see changes in the character of Anglo-Saxon settlements that may mirror other substantial changes in Anglo-Saxon society.

Settlement Changes in the Late 6th and 7th Centuries

In this section, I will argue that the archaeological evidence points to changes in settlement patterns that first appear in the late 6th and 7th centuries CE. These include the appearance of rural settlements with more elaborate architecture than the typical Early Saxon villages such as West Stow, the appearance of possible royal sites, and the establishment of the earliest of the rural estate centers. These data suggest that a true settlement hierarchy is emerging in Anglo-Saxon England by the 7th century CE. I will further suggest that these changes mirror broader changes in Anglo-Saxon society and that they laid the foundation for the political consolidation and urbanism that become apparent in the Middle and Late Anglo-Saxon periods.

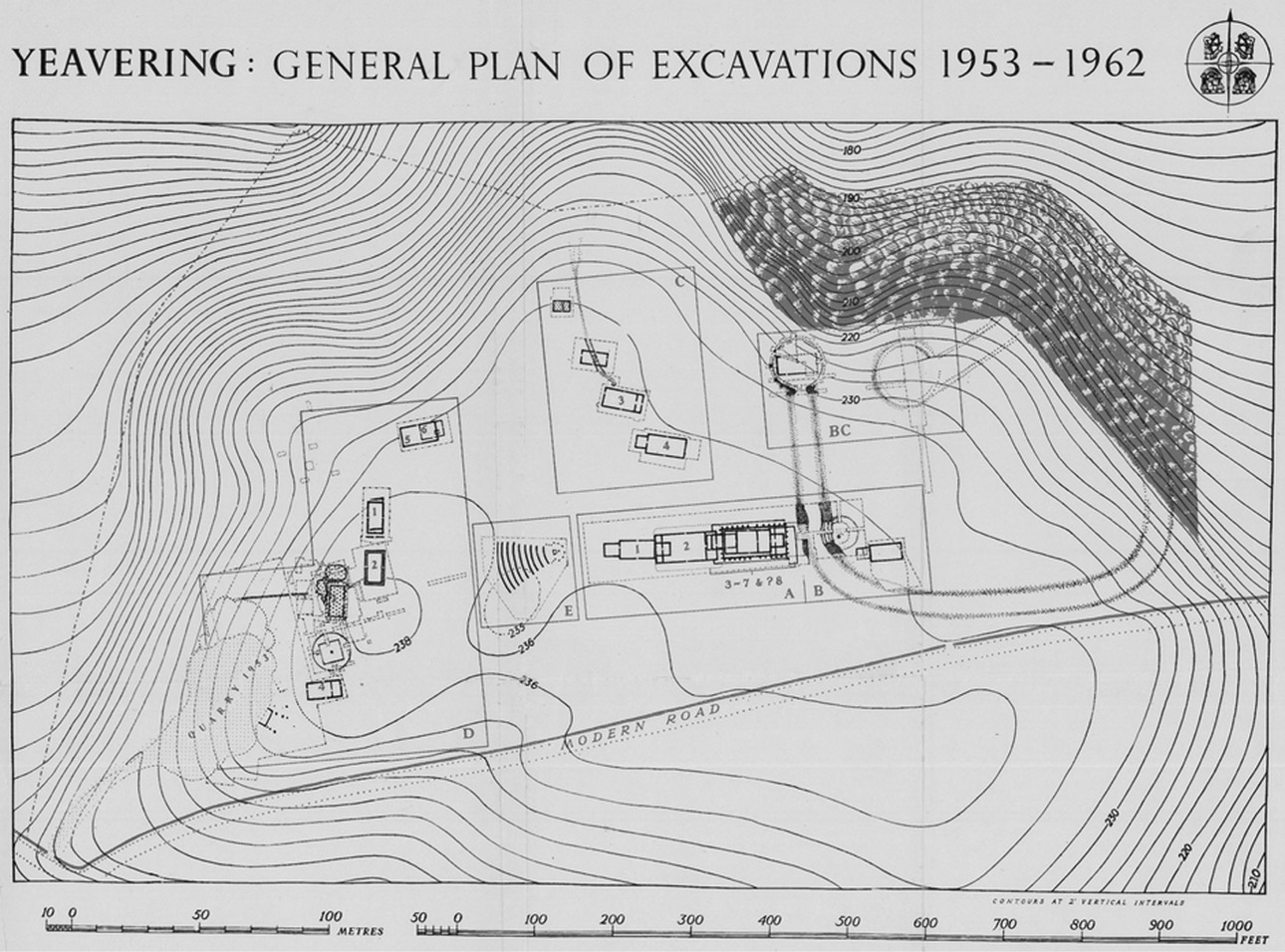

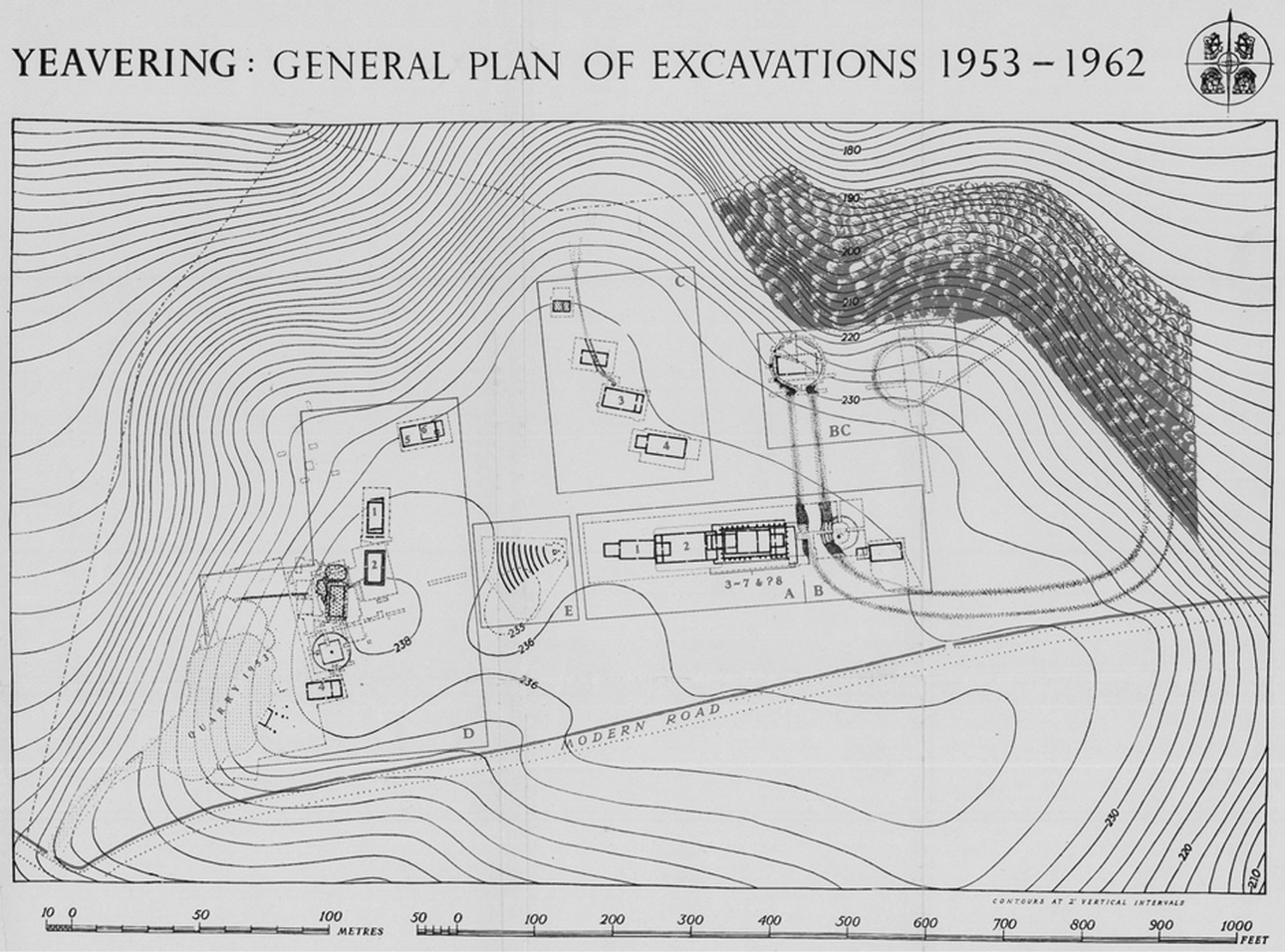

At the top of the settlement hierarchy is the royal palace at Yeavering in Northumberland (Hope-Taylor Reference Hope-Taylor1977). The site was discovered through aerial photography in 1949 and subsequently excavated by Brian Hope-Taylor between 1953 and 1962 since the site was threatened by quarrying. Yeavering is the site of prehistoric activity, including a henge monument and burials. The Anglo-Saxon settlement at the site was established in the second half of the 6th century as one or two small homesteads (Scull Reference Scull1991), and a number of Early Anglo-Saxon burials were placed near the prehistoric ones. In the early 7th century (Phase IIIc) it developed into an elaborate settlement and ceremonial complex (Figure 2.6). The complex included a large timber hall, Structure A4, as well as a number of other carefully laid-out timber buildings. The hall is one of the largest buildings of this date that is known from England. Other structures included a large enclosure whose function is not clear, possible Pagan monuments including postholes that may have served as settings for carved poles, and a grandstand-like structure with tiers of steps leading down to a throne. The site does not appear to have been occupied year round. It is probable that the early Northumbrian kings were eating their way through their territories in the 7th century. While the king was in residence at Yeavering, he may have collected tribute, hosted feasts, and settled disputes.

A second level in the settlement hierarchy is represented by the settlement at Bloodmoor Hill, Carlton Colville, Suffolk (Lucy et al. Reference Lucy, Tipper and Dickens2009). The site was occupied from the 6th to the earlier 8th century CE, and it was subject to a recent program of excavation. The excavated area included over 30,000 square meters, and the excavations uncovered 38 sunken-featured buildings, 9 post-built structures, and over 270 pits. The site yielded extensive evidence for metal-working, including crucibles, molds, and substantial collections of scrap metal. These data suggest that specialized craft production was taking place at the site, probably carried out by specialists who were attached to the lord of the estate. The mid- to late 7th-century graveyard also included high-status female burials. The excavators have suggested that Bloodmoor Hill may represent an early estate center.

Archaeozoological data also support this interpretation. While most Early Anglo-Saxon sites have a pastoral economy based on autarky or economic self-sufficiency (Crabtree Reference Crabtree2010b), the pattern of animal management seen at Bloodmoor Hill is more complex. While pigs seem to have been raised for local consumption and cattle were kept for dairying and for traction, the sheep seem to have been reared for more specialized wool production (Higbee Reference Higbee, Lucy, Tipper and Dickens2009). This kind of specialized production is seen much more commonly at later Middle Saxon estate centers including Brandon in Suffolk, Wicken Bonhunt in Essex, and Flixborough in Lincolnshire (Dobney et al. Reference Dobney, Jaques, Barrett and Johnstone2007; Crabtree Reference Crabtree2010b, Reference Crabtree2012; Crabtree and Campana Reference Crabtree, Campana, Arbuckle and McCarty2015).

Additional intriguing data come from the 7th-century site of Cowdery’s Down in Hampshire (Millett and James Reference Millett and James1983). Excavations revealed 18 structures that were dated to the 6th–7th centuries CE on the basis of radiocarbon. They included 16 posthole or trench-built constructions and only two sunken-featured buildings. The buildings were assigned to three sequential phases, and the settlement was composed of three, six, and ten major structures along with two fenced enclosures in each phase. A striking feature of Cowdery’s Down is the presence of these fenced enclosures, which are not seen on earlier sites. The size and techniques used to construct these buildings set them apart from most of what is known of Anglo-Saxon domestic architecture. Marshall and Marshall (Reference Marshall and Marshall1991, Reference Marshall and Marshall1993) surveyed 267 Anglo-Saxon domestic buildings from the 6th through the 9th centuries CE. Several of the buildings from Cowdery’s Down are among the largest and widest structures included in their survey. The largest structures at Cowdery’s Down are also distinguished by the presence of possible cruck architecture (Figure 2.7). Using this method, the outer door frames extend into the roof, and the roof is supported by curved timbers known as crucks. The presence of this type of architecture suggests the presence of skilled carpenters who may have been attached to local lords. Millett and James (Reference Millett and James1983, 247) suggest that the large buildings reflect high social status. In each phase, a major structure is located inside, but close to, the enclosures. The excavators suggest that this may represent a chief’s house. There is also evidence for careful planning in Phase C. The largest building, structure C12, is centrally located on the crest of a ridge. Very few artifacts were recovered from the site, and the excavators (Millett and James Reference Millett and James1983, 249) suggest that the site might have been occupied seasonally as part of a peripatetic kingship, a feature that is well known from the later Middle Saxon period.

Figure 2.7. Reconstruction of structure C12 at Cowdery’s Down.

Cowdery’s Down, along with Yeavering, provides some of the earliest evidence for repair, remodeling, and in situ replacement of Anglo-Saxon buildings. Two of the buildings from Phase B of the Anglo-Saxon settlement were rebuilt in the same location in Phase C (Millett and James Reference Millett and James1983, 213; Hamerow Reference Hamerow, Hamerow, Hinton and Crawford2011, 135).Footnote 2 The choice to rebuild on the same footprint, along with the presence of fenced enclosures around the structures, suggests that attitudes toward space, and possibly land and property ownership, were beginning to change in the 7th century. In this context it is interesting to note that some of the very latest structures at West Stow are a series of ditches, some of which cut through earlier Anglo-Saxon features, which may represent property boundaries. As noted above, these ditches were originally dated to the 7th century on the basis of Ipswich Ware (West Reference West1985, 54). With the redating of Ipswich Ware, they are now almost certainly 8th century.

The process of settlement transformation in the late 6th and 7th centuries can be seen most clearly at the Anglo-Saxon site of Lyminge in Kent (Thomas Reference Thomas2013). The Early Saxon settlement at Lyminge was established in the 5th century. Up until the late 6th century, the settlement is composed of small, earth-fast timber buildings and sunken-featured buildings, but unlike the settlement evidence known from West Stow and Mucking, artifactual and burial evidence indicate that Lyminge was home to one or more rich and powerful households (Thomas Reference Thomas2013, 120). The small finds from the site include a diversity of glass vessel forms, and the Early Anglo-Saxon faunal assemblage is dominated by the remains of pigs, which are often associated with high-status settlements (Thomas Reference Thomas2013, 125). The Lyminge cemeteries included evidence for a horse burial and a grave of a 6th-century woman who was wearing a Scandinavian gold bracteate. A bracteate is a small, circular gold pendant that is worn around the neck; it is often associated with women of the highest rank.

The character of the settlement changes in the late 6th century with the construction of a very large timber hall at the headwaters of the Nailbourne River. The hall measures 21 m by 8.5 m and includes internal partitions at the east end. A smaller post-in-trench building is located to the east of the great hall, suggesting that these buildings are part of a planned cluster of high-status buildings. The great hall is closely comparable to the buildings seen at Cowdery’s Down and Yeavering (Thomas Reference Thomas2013, 126–7). Place-name evidence suggests that Lyminge was a royal vill at this time.Footnote 3 The site subsequently emerges as a monastic center in the late 7th century.

While there is no clear archaeological evidence for the development of urban centers in the later 6th and 7th centuries CE, the changes that we see in settlement patterns are reflected in other aspects of the archaeological record and in the beginnings of the historical record as well. Thirty years ago, Arnold (Reference Arnold and Bintliff1984, 280) pointed out that we see a clear change in Anglo-Saxon burial practices in the early 7th century. In the 6th century and earlier, the richest Pagan Saxon graves are found in communal cemeteries. By the 7th century, the richest graves contain even greater wealth and are often found isolated from the rest of the population.

The classic example of a wealthy 7th-century grave is the burial in Mound 1 at Sutton Hoo (Figure 2.8). The site was initially discovered in 1939 on the eve of World War II and was published by Bruce-Mitford (Reference Bruce-Mitford1972). Mound 1 contained the remains of a ship burial, although the body of the deceased was never recovered. A richly furnished burial chamber was constructed in the center of the 27-m-long ship. The grave was equipped with a helmet, shield, and sword, as well as large quantities of decorated metalwork, including a belt buckle, shoulder clasps, and a purse lid. The purse contained 37 gold tremises, each from a different mint in Francia, as well as three coin blanks and two ingots. The body was accompanied by Byzantine silver bowls and two silver spoons engraved with the names Paulos and Saulos (Paul and Saul). Other grave goods include a mail coat, leather shoes, textiles, and drinking horns made of aurochs (wild cattle) horn (Figure 2.9).

Figure 2.8. Image of Sutton Hoo Mound 1 as it exists today.

Between 1983 and 2001 Martin Carver (Reference Carver2005) led an ambitious program of survey and excavation that was designed to place the Sutton Hoo grave mounds into a broader landscape context (see also Williamson Reference Williamson2009). It included extensive survey of the cemetery and the surrounding area and re-excavation of a number of the burial mounds. Carver’s research showed that the initial 6th-century cemetery at Tranmer House was established in the northern part of the Sutton Hoo area. It contained cremations and inhumations and continued in use until the close of the 6th century (Fern Reference Fern2015). It began as a folk cemetery, but wealthy individuals were clearly present by the later part of the 6th century. The successor cemetery at Sutton Hoo that included Mound 1 was opened at the end of the 6th century “to commemorate people with enhanced social pretensions” (Carver Reference Carver2005, 490). This cemetery includes nearly 20 mounds that were constructed in the late 6th and 7th centuries. These burials may be associated with the kings that appear in Anglo-Saxon king lists for East Anglia, since the site is close to the royal center at Rendlesham. During the 8th to 11th century, the site was transformed into a place of execution.

What kind of settlement might have been associated with Sutton Hoo? While Bede reports that Swithelm, king of the East Saxons, was baptized at Rendlesham, the exact location of this Anglo-Saxon royal settlement was unknown until recently. In 2007 a local landowner in Rendlesham reported that illegal metal detectorists were looting his fields at night. His complaint eventually led to an extensive program of archaeological survey that covered 160 ha. Systematic metal detecting was used to identify and record finds from the plow soil, and magnetometry (see Chapter 4) was used to identify buried remains in the areas where the surface finds were densest (Scull et al. Reference Scull, Minter and Plouviez2016). Magnetometers detect slight changes in the earth’s magnetic field, which can be caused by sub-surface features such as pits and ditches and iron objects. The archaeologists also examined aerial photographs of the region.

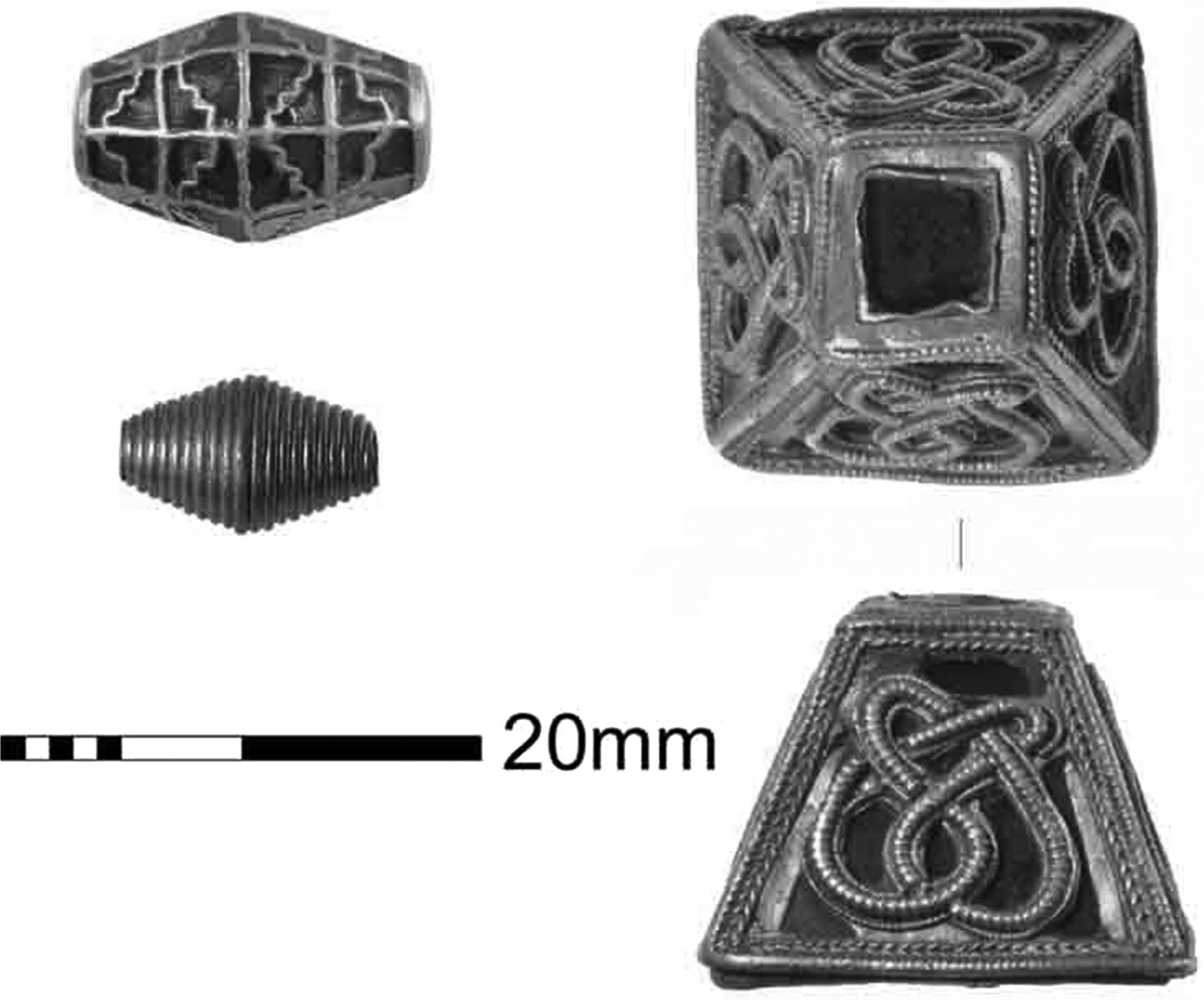

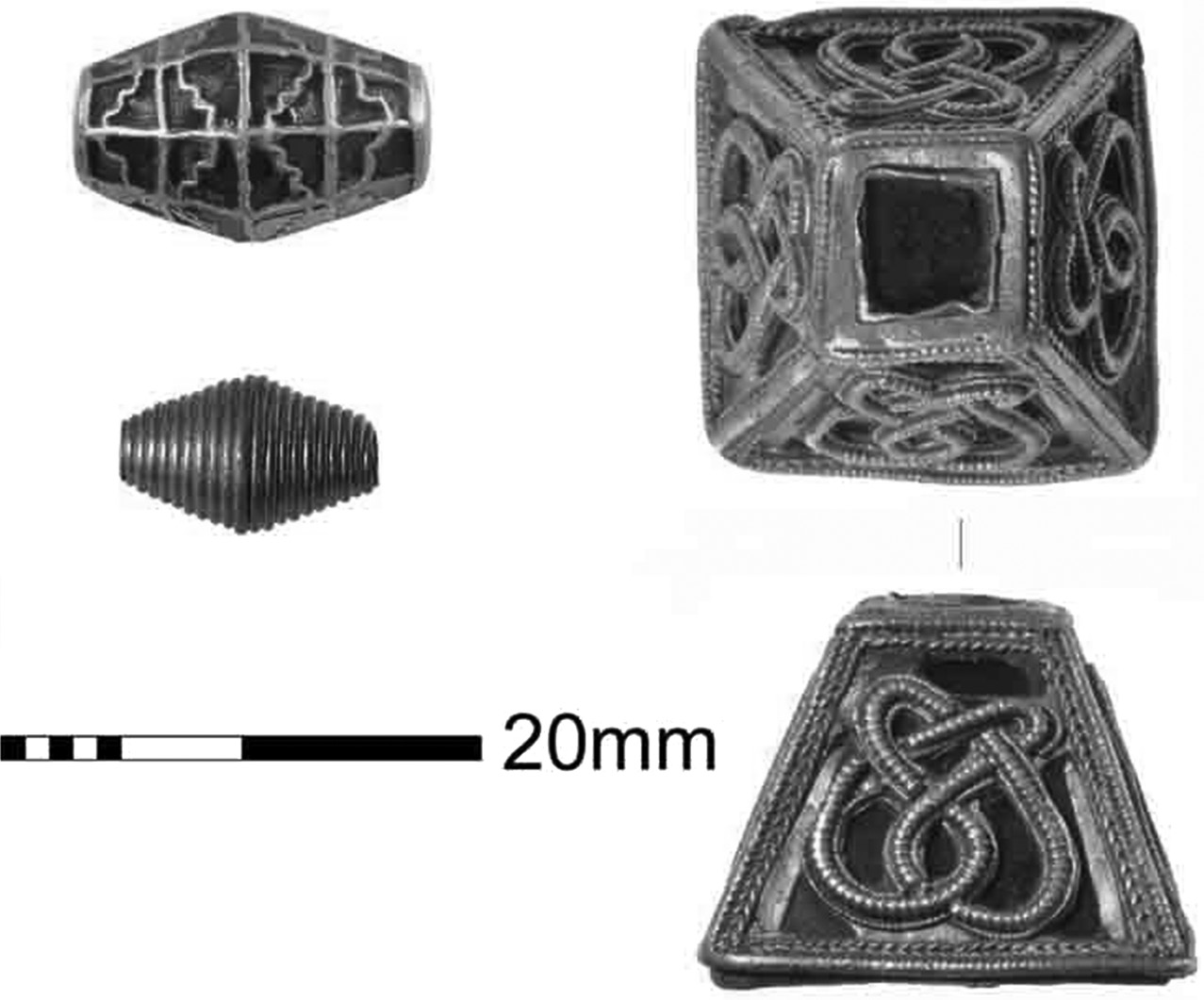

The survey revealed a concentration of small finds and features in an area covering about 50 ha (Scull et al. Reference Scull, Minter and Plouviez2016, 1597). This area is located about 4 miles (7 km) northwest of Sutton Hoo along the River Deben. The Anglo-Saxon finds range in date from the 5th through the 8th century CE, but the site reached its zenith between the early to mid-6th century and the second quarter of the 8th century (Scull et al. Reference Scull, Minter and Plouviez2016, 1601; Minter et al. Reference Minter, Plouviez and Scull2014, 52). The finds provide evidence for metal-working, as well as dress fittings, jewelry, silver coins, and mounts for hanging bowls, all from northern and western Britain (Figure 2.10). Imported items include Coptic bowls from the eastern Mediterranean, in addition to Byzantine copper coins and Merovingian gold coins (Plouviez Reference Plouviez2014). The presence of coins and weights indicates that Rendlesham may have been the location of periodic fairs or markets. The evidence for trade and commerce decreases in the early 8th century, just as Ipswich was expanding (Minter et al. Reference Minter, Plouviez and Scull2014, 53). The role of Ipswich as a major center for trade and exchange during the 8th and 9th centuries will be examined in Chapter 3. The rich and extensive settlement at Rendlesham indicates that the emerging East Anglian royal house was not just collecting food rents from the surrounding countryside, but it was also engaged in craft production, trade, and exchange. Scull et al. (Reference Scull, Minter and Plouviez2016, 1605) suggest that it served as “a permanent centre for agrarian or economic administration, a periodic residence for a peripatetic elite, and a periodic meeting places for military and jurisdictional assemblies.”

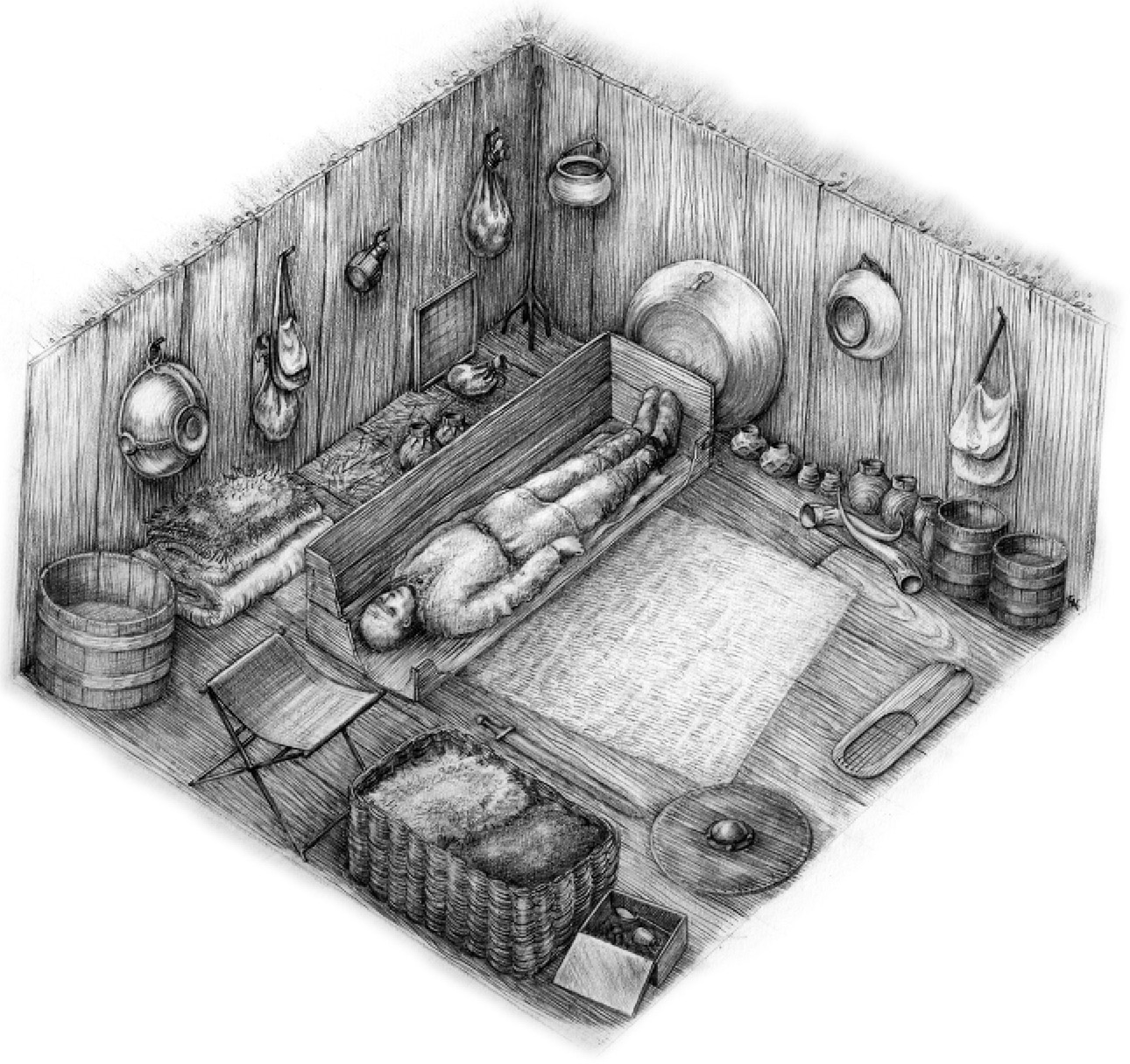

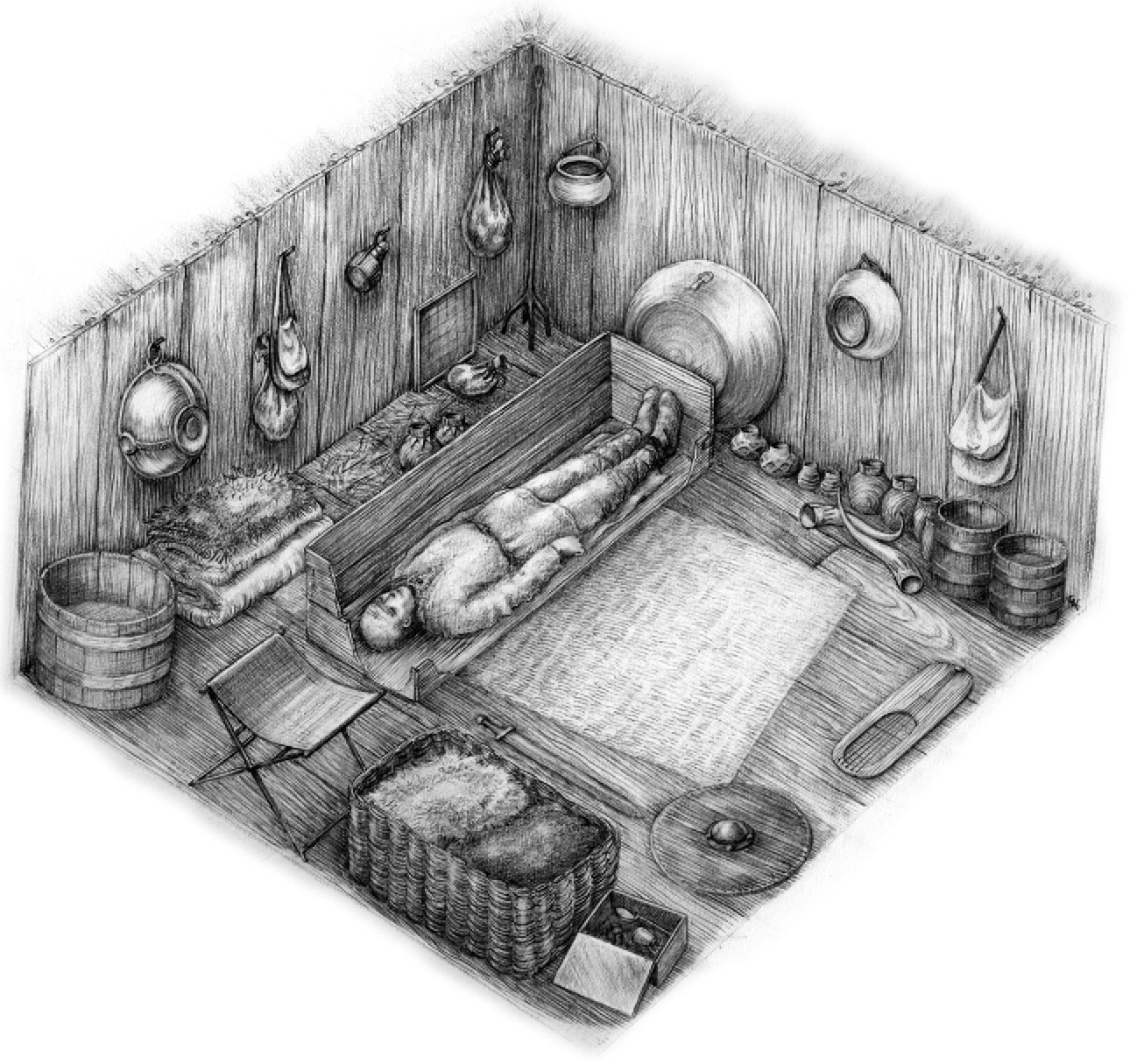

While Sutton Hoo Mound 1 is probably the best known of the wealthy early 7th-century Anglo-Saxon graves, it is certainly not the only one. One of the most spectacular finds of the 21st century is the so-called prince’s grave at Prittlewell in Essex (Blair, Barnham, and Blackwell Reference Blair, Barham and Blackmore2004). The burial was discovered in a known Anglo-Saxon cemetery by the Museum of London Archaeological Service in 2003 in advance of a road improvement project. It included an underground chamber that was probably originally covered with a mound. The chamber had timber-lined walls and a plank roof and was 4 m square and about 1.5 m deep. When the roof collapsed, the contents of the burial were sealed (Figure 2.11). Although the acidic soils destroyed all traces of the body, the burial was furnished with weapons and feasting equipment, as well as two gold foil crosses, two Merovingian gold coins, and a lyre. Other imported items include a flagon and bowl from the eastern Mediterranean, Coptic bowls, and a Byzantine silver spoon similar to the ones that were recovered from Sutton Hoo.

A number of other rich late 6th–earlier 7th-century princely burials are known from other parts of southeast England, although most were excavated before the advent of modern archaeological techniques. These burials are generally covered with barrows and usually command long views. A well-known example is the 7th-century burial at Taplow in Buckinghamshire. The barrow, which dominates the surrounding landscape, was excavated in 1883 under less than optimal conditions. The deceased was buried facing west in an oak chamber. He was laid out on a bier and accompanied by three sets of weapons and 19 feasting and drinking vessels, including four glass claw beakers and gilt silver mounts for drinking horns that were made from aurochs (wild cattle) horn. Since aurochs had been extinct in Britain for many centuries, these horns must have been imported from somewhere in east-central Europe. Other imported items include a Coptic bowl and stand. Luxury items such as the gold and garnet buckle are now housed in the British Museum. Many of the items in the burial appear to be Kentish in origin, and Webster (Reference Webster2001) notes that this region represented the furthest west extent of Kentish power at about 600 CE; the area subsequently came under Mercian domination. Webster suggests that the interred may represent a Kentish sub-king who ruled under Mercian authority.

The archaeological data clearly show that by the late 6th to earlier 7th-century housing and burial rites were being used to express differences in social status, political power, and material wealth. While Anglo-Saxon England of the 5th and earlier 6th century was by no means an egalitarian society, these archaeological data can be interpreted to suggest the emergence of a small, powerful class of chiefs or kings by the late 6th century. Drawing on the more limited historical data, Yorke (1989, Reference Yorke1993, Reference Yorke, Goetz, Jarnut and Pohl2003) has suggested that the 5th- and 6th-century confederations of Angles and Saxons broke up and were transformed into a series of smaller kingdoms around 600 CE. She further suggests that it was the Franks trying to control cross-channel trade who may have provided the impetus that caused powerful military leaders to transform themselves into ruling dynasties (Yorke Reference Yorke, Goetz, Jarnut and Pohl2003).

The question of how the transformation took place has been poorly theorized, and only a few explanations for this process have been proposed. Many historians have simply avoided this issue because the documentary record for the period is so limited. Unlike prehistoric archaeologists, many Anglo-Saxon archaeologists have been reluctant to draw parallels to similar processes of socio-political change outside Europe. However, Scull (Reference Scull1993), Yorke (Reference Yorke, Goetz, Jarnut and Pohl2003), and Oosthuizen (Reference Oosthuizen2011, Reference Oosthuizen2016) have addressed this issue from three different, but not necessarily mutually exclusive, perspectives.

Scull (Reference Scull1993) was one of the first archaeologists to address this issue from a processual perspective. Like Hodges (Reference Hodges1982) before him, Scull (Reference Scull1993, 67) suggests that the control of trade played a major role in the emergence of Anglo-Saxon kingship. Scull sees Early Anglo-Saxon society as made up of internally ranked, patrilineal descent groups farming their own territories. He suggests that there was competition between these lineages, and, by the later 6th–7th century, there was competition between elites at both the local and regional levels and an increase in social ranking. This can be seen in the emergence of the settlement hierarchy and the princely graves. Scull (Reference Scull1993, 76) also suggests that external links may have played a role in this transformation.

Scull (Reference Scull1993, 77) sees this transformation as a multi-stage process beginning with ranked lineages competing with one another. Some initially achieve local hegemony; then competition between local chiefs leads to temporary regional or interregional hegemonies. These, in turn, are transformed into a more permanent political hierarchy with a more formal administrative organization. Scull (Reference Scull1993, 77) sees control of trade as a critical factor in this process because it allowed for the acquisition and redistribution of exotic imported items. He also suggests that population growth may have been a motivating factor, as it put pressure on land as a social resource (Scull Reference Scull1993, 77–8).

Yorke (Reference Yorke, Goetz, Jarnut and Pohl2003) has taken a different approach to the formation of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. As noted above, she suggests that in the late 6th to 7th century the older confederations of Angles, Saxons, and Jutes were broken up. At that time, we see the beginnings of a process of secondary state formation. While Yorke does not provide an explicit model for this process, she suggests that the ability to create and exploit both agricultural surpluses and other sources of wealth played an important role in this transformation (Yorke Reference Yorke, Goetz, Jarnut and Pohl2003, 402). She also suggests that the conversion to Christianity may have been an important underpinning of these Early Anglo-Saxon kingdoms (Yorke Reference Yorke, Goetz, Jarnut and Pohl2003, 406).

Oosthuizen (Reference Oosthuizen2011, Reference Oosthuizen2013) has recently proposed an alternative model for kingdom building in the 6th–7th centuries. She notes that Early Anglo-Saxon societies were pastorally oriented and suggests that there was a long-term continuity in grazing rights and rights to the common from prehistoric to early historic times. Oosthuizen suggests that these flexible, adaptive, and absorptive rights may have provided the foundation for the political, economic, and social changes of the Middle Anglo-Saxon period. While Scull’s model is based on competition, Oosthuizen’s focuses on consensus, legitimacy, and collective assent.

Oosthuizen (Reference Oosthuizen2016) has developed these ideas further in a recently published paper. She suggests that long-term continuities in agricultural land use and forms of collective government are related to substantial continuity in population between Roman Britain and Early Anglo-Saxon England. She argues against “migration from northwest Europe as being the triggering factor in the emergence of new forms of political governance that led to the emergence of the early ‘Anglo-Saxon’ kingdoms” (Oosthuizen Reference Oosthuizen2016, 209). However, she admits that this argument does not mean that there is no merit in an elite replacement or dominance model. Long-term continuities in property rights, land use, and population are not necessarily inconsistent with the emergence of a dominant military elite, which may have included both indigenous inhabitants and continental migrants or their descendants.

One point that deserves further discussion is Yorke’s contention that the ability to create and exploit agricultural surpluses (and other sources of wealth) was crucial to state formation in Anglo-Saxon England. Here Yorke is essentially talking about what Childe (Reference Childe1950) referred to as a social surplus. It is the creation and extraction of the agricultural surplus that is critical to its use in political economy. Patron–client relationships, structured relationships between people of unequal rank, may have played a critical role in the creation and extraction of social surplus in Anglo-Saxon England. These relationships are features of traditional Roman, Celtic, and Germanic societies, and they would have entailed rights and responsibilities on behalf of both the patron and the client.

Archaeological data and literary evidence can be used to try to reconstruct this process. One of the obligations that a client would have had to his chief or king would have been food rent. The chief could have used the food rent as a form of social capital to support activities such as feasting. Feasting plays an important role in Anglo-Saxon literature such as Beowulf, and it is significant that the princes’ graves contain a number of items that seem to be associated with feasting. Feasting encourages loyalty, which is crucial in warfare and in competition between rival elites. The princes’ graves all include substantial sets of weaponry. Control of exotic luxury items is important not only because they are symbols of status and wealth, but also because they can be used to reward loyalty in followers.

I would argue that those leaders who were most successful patrons were likely to have emerged as kings in the early 7th century. It could even be argued that some of the continental elites were patrons of the emerging Anglo-Saxon royal houses. Formalizing many of the traditional patron–client ties may have served as the basis for the administrative structures of the Middle Anglo-Saxon period. A focus on patronage is compatible with the models proposed by Scull, Yorke, and Oosthuizen. Following Scull (Reference Scull1993), successful patrons will be better able to compete with other elites at the local and regional levels. Successful patrons may have styled themselves as the “heirs of Rome,” following Yorke (Reference Yorke, Goetz, Jarnut and Pohl2003, 402; see also Oosthuizen Reference Oosthuizen2016). As Hunter (Reference Hunter1974) has shown, by the beginning of the Middle Anglo-Saxon period, the Roman and Germanic traditions had been successfully fused in the minds of the Anglo-Saxons. In addition, successful patrons may have been part of large groups who shared common grazing rights, following Oosthuizen (Reference Oosthuizen2011). Elite patrons who were best able to control economic surpluses and use them to their own benefit may have emerged as kings by the early 7th century.

In conclusion, it is worth emphasizing that despite the changes in settlement patterns, social organization, burial practices, and rural economy that took place in the later part of the Early Anglo-Saxon period, these changes did not directly lead to or necessitate the re-emergence of towns at this time. However, these changes provide the social and economic background for the re-emergence of towns in the Middle Saxon period, which will be discussed in the following chapter.

Western Britain in the 5th–7th Centuries

The patterns of settlement, subsistence, and technology that existed in western Britain during the 5th through the 7th centuries are strikingly different from those that we have seen in eastern England. At the top of the settlement hierarchy are a series of fortified sites, including a number of reoccupied and refortified Iron Age hillforts (Burrow Reference Burrow1981). These includes sites such as Dinas Powys in Glamorgan, Wales (Alcock Reference Alcock1963, Reference Alcock and Crabtree2001) and Congresbury–Cadbury in Somerset (Rahtz et al. Reference Rahtz, Woodward, Burrow, Everton, Watts, Leach, Hirst, Fowler and Gardner1992), which may have served as royal centers for sub-Roman British polities. These polities were ruled by kings, described by Gildas as tyrants, but who are probably military strongmen and their retinues (Costen Reference Costen2011, 16). The various fortified sites may have been used on a peripatetic basis by these kings (Thomas Reference Thomas1988, 429).