This chapter sketches out the nature and scope of the evidence available for Greek housing during the first millennium BCE. Drawing on textual sources, the significance of the house in ancient Greek (mainly Classical Athenian) culture is investigated. Some of the processes (both human and natural) which have shaped the material remains of the houses themselves are outlined.

The Idea of a House

A house is more than simply a building. In modern western culture it is a deeply symbolic structure: ownership of a house or home is a dream to be striven for even (if the economic crisis of the early twenty-first century is any guide) where attaining that goal requires unsustainable sacrifices in other aspects of life. At the same time, a house is also a vehicle for self-expression. Its location, style and decoration often proclaim its occupants’ membership of specific social, economic, ethnic or other groups (either consciously or subconsciously); somewhat paradoxically, its decoration also often simultaneously demonstrates their individuality. These two conflicting messages can often be in tension with each other within the context of a single building.

In the ancient Greek world, too, housing carried strong symbolic associations. Archaeology and texts both show that we should be careful not to assume that these associations were the same as our own. The words for ‘house’ (oikia) and ‘household’ (oikos) are closely related and in some ways the house seems to have embodied the survival and continuity of the household, transcending individual generations of human lives. Relevant written sources offering an insight into the symbolic aspects of Greek houses derive mainly from the context of fifth- and fourth-century BCE Athens. These texts must be read with a critical awareness of their context: they present the personal perspectives of their writers (with all the geographical, social, gender and other biases those may entail) and they are constrained by the conventions of the various genres in which they are composed. It is important to remember that attitudes are likely to have changed through time and space. Indeed, some of those changes are explored through the material record in the later chapters of this book. But the written sources do, nevertheless, offer a sense of some of the range of associations houses may have evoked, at least in Classical Athenian culture. They, therefore, represent a helpful starting point for thinking about some of the parallels and contrasts between ancient Greek and modern western attitudes towards housing.

A superficial reading of the Classical Attic texts suggests that, as in many cultures, elite, male Athenians (the authors of these accounts) construed the house as a female domain, in contrast with the public sphere, which is often portrayed as male. But as we shall see, a closer look reveals that this is a rhetorical trope which does not, in fact, convey the full range of associations carried by a house. The physical building itself was also articulated as being central to the (male) householder’s identity and to the well-being of the household. A particular form of punishment, known as ‘kataskaphe’, was carried out in Athens and elsewhere. This involved (among other things) the complete destruction of a convict’s entire house and presumably also the dispersal of its contents. The material significance of this act of punishment will become increasingly clear as we explore the symbolism of the house through Athenian texts and look at the character of the Greek domestic environment using archaeological evidence. Broadly speaking, however, kataskaphe dismantled the household by removing its living space. This meant eliminating both stored foodstuffs and the durable goods which might have been used to produce, or been exchanged for, further supplies. Kataskaphe was also a deeply symbolic act. It must have erased a man’s social identity by depriving him of the location in which he could be found by, and entertain, his friends and associates. It would also have destroyed the paraphernalia of domestic cult, which may have included both apotropaic Herms (stone markers with sculpted heads sacred to the god Hermes) at the house entrance and altars located in and around the central courtyard. It may also have dispersed his household.

Housing was not only important spiritually and materially, but it also carried symbolic weight, and in a variety of textual sources it is taken as emblematic of an owner’s character and personal conduct. At Classical Athens, a degree of moderation and self-restraint is articulated as the expected norm in this, as in other aspects of life. For example, the orator Demosthenes, speaking during the mid fourth century BCE, comments repeatedly that the prominent statesmen of earlier generations – Aristeides, Miltiades, Themistokles and Kimon – lived modestly in houses which were no different from those of their less illustrious fellow citizens (Text Extract 1). We do not, of course, have any way of knowing whether Demosthenes was right, and his comments are made for comparative purposes, contrasting the modest houses with the magnificent religious buildings of the Periklean Akropolis and with the opulent buildings of the Macedonian king, Philip II. Nonetheless, the fact that Demosthenes is able to use such claims to rhetorical effect suggests that there was probably at least some degree of contemporary public support for restraint of ostentation and expenditure on houses but that, at the same time, there may have been citizens beginning to indulge themselves in precisely this manner. (As we shall see in Chapter 7, this interpretation is supported by the archaeological evidence for the housing of this period more broadly.)

Demosthenes’ perspective is shared by other authors: a similar point is made by Xenophon, also writing in the fourth century BCE, who suggests that it is much better to spend money on beautifying the city as a whole than on decorating one’s own private house (Text Extract 2). Restraint over the lavishness of housing is also mentioned by Plutarch, writing four centuries later, when discussing the fourth century BCE Athenian tyrant Lykourgos, one of whose actions was said to have been to introduce a law preventing individual houses from becoming too extravagant (Text Extract 3). But the level of decoration in housing at Athens was perhaps viewed as unrepresentative of that in the Greek world more generally, even at a later date, if the comments of Herakleides Kritikos are to be believed: writing in the mid third century BCE, he claimed that there were still few lavish houses in Athens (Text Extract 4). (His description of this city contrasts with his picture of Tanagra, in Boiotia, which he says is most beautifully built, the houses having fine porches.)

At the same time as being a public symbol, an individual’s house also seems to have been regarded as very much his own domain. The act of crossing the threshold placed an obligation on a visitor to act according to specific social codes. Writing in the first century CE, Plutarch comments that a visitor should give a warning of his approach so as not to catch a glimpse of some domestic activity which should not be witnessed by an outsider (Text Extract 5). In the context of Classical Athens, major transgressions by would-be callers come to the fore. Plato and Xenophon offer several descriptions of situations in which visitors did not follow the normal protocols, instead arriving drunk and demanding to see the owner of the house even if he was busy (for example, Alkibiades arriving at Agathon’s house in Plato’s Symposium, 212 C-D: Text Extract 6). In Athenian legal speeches, episodes in which a man enters another man’s house without permission are portrayed by the prosecution as outrageous. The transgression is often compounded by the fact that such uninvited guests are said to have burst in on female members of the household. (See Text Extract 7; the gender dynamics represent part of a wider sensitivity about social contact between women and unrelated men, a theme taken up again in Chapters 4 and 7.)

A number of sources imply that as well as these kinds of social rules covering the behaviour of visitors, there were also expectations about appropriate domestic behaviour which applied to the residents of a house. In Athenian drama some disapproval is displayed towards wives who leave their houses too frequently or without proper reason. (For instance, in a very fragmentary text, the comic playwright, Menander, writing in the late fourth to early third century BCE, portrays a man chastising his wife for going into the street outside: Fragment 546 K). Passing over the threshold thus seems to have been a symbolic act for both visitors and residents, and its significance is perhaps confirmed by numerous references to doorkeepers. In theory, their job seems to have been to control who came into the house, although they are sometimes depicted as failing to keep out unwanted guests, as was the case with Alkibiades in Plato’s Symposium, mentioned above (Text Extract 6). At the other extreme, the doorkeepers themselves are portrayed as capable of ignoring normal social rules, as in Plato’s description of Kallias’ doorman, who tries to exclude even callers who observe the social etiquette and have genuine reason to enter (Text Extract 8). A house also played a more pragmatic role – as an economic asset. Inscriptions from a range of locations including Athens and also the city of Olynthos in northern Greece (discussed in detail in Chapter 4), attest to the mortgaging and sale of urban houses (Text Extract 9).

Even taken together this textual information offers only partial coverage of a narrow range of topics and is limited in its geographical scope. It also draws on sources ranging over several centuries in time. The authors, nevertheless, reveal glimpses of what appears to be a durable and deeply entrenched system of beliefs surrounding domestic life. The fact that a number of texts of different genres describe incidents (real or fictitious) in which there was a failure to observe apparent norms, suggests that such norms were widespread and that there may have been some degree of ambivalence about them, such that they may not always have been followed in the course of day-to-day life. The house, therefore, seems to have constituted something of a contested space – a context in which social rules and boundaries were negotiated through the behaviour of, and interaction between, different social groups (male: female; resident: non-resident; younger: older; higher status: lower status, etc.). Study of ancient Greek housing thus potentially enables us to explore some of these tensions and boundaries.

The model sketched above offers a few strands of information about some aspects of the symbolism attached to housing by specific individuals, during particular periods and in certain locations, pointing up some major differences between ancient Greek and modern western conceptions of the house as a social and symbolic space. But the cultural significance of housing is likely to have changed through time and space within the Greek world. Our textual sources are too few, and too limited in their chronological, geographical and social coverage, to provide a full and nuanced picture. Instead, it is necessary to turn to the archaeological evidence, which is the main subject of this book. The remainder of this chapter explores the nature of the evidence itself, laying out some of the general characteristics of Greek houses during the first millennium BCE. The history of research on this material is sketched, including some of the main issues which have been discussed. These sections serve as a background for the more detailed chapters that follow, which ask what the evidence of housing can tell us about Greek domestic life and about Greek society more generally, highlighting patterns of continuity and change across time and space.

The Nature of the Archaeological Evidence for Ancient Greek Housing

Houses have survived at large numbers of sites of different dates from across the ancient Greek world. There are many characteristics they have in common: on the Greek mainland the most widely used building technique was to form a low stone wall or socle on which was erected a superstructure composed of sun-dried mud bricks. Mudbrick is easy to obtain, relatively straightforward to work with, and has good insulating properties. In fact, this building method was used in Greece into the twentieth century, and still continues in use in some other parts of the world. Its disadvantage, though, is that the mud is very vulnerable to damage by water, which dissolves the bricks, turning them back into mud. The stone socle raised the bricks above ground level, preventing rainwater from pooling against exterior walls and dissolving them. There is some evidence to show that, as with much more recent buildings constructed in this way, the exterior walls were sometimes provided with a coating of lime plaster which would have guarded against rain splashes. On Delos, where the exterior walls are constructed entirely of stone and therefore survive better than mudbrick, evidence survives of several coats of plaster including an outer layer coloured white (Figure 1.1). These structures and evidence from other stone-built houses at Ammotopos suggest that such houses would have presented the passerby with a relatively blank façade, pierced only by a single street door with perhaps a few openings for ventilation high in the wall. A small number of other features may have provided hints about the identity and status of the occupants within, however: in a few cases the use of large blocks of well-cut ashlar masonry in the socle of the façade may have served to differentiate a particular house from those around it. The financial inscriptions mentioned above seem likely to have been set into the façades of the houses to which they applied, where they would have warned any prospective purchasers that a particular property was encumbered, or attested to the house changing hands. Presumably, they might also have conveyed information about the identities of the owners, their wealth and who their associates were, since guarantors and witnesses to the transactions are listed (Text Extract 9).

Pitched roofs with deeply overhanging eaves are also likely to have been used to keep rain away from the exterior walls (as has been suggested for the heröon building at Lefkandi: see Chapter 2). Evidence for the exact design rarely survives archaeologically although in large interior spaces it was sometimes supported by internal posts, as indicated by post-holes or stone bases. During the Early Iron Age, such roofs were normally thatched, but by the fifth and fourth centuries BCE terracotta roof tiles were widespread on domestic buildings. They would have been supported on wooden beams and sometimes seem to have been removed when the houses were abandoned, since they are not always found in large numbers during excavation. It is frequently assumed that at least part of the roof would have been pitched inwards towards the courtyard (as shown in Figure 3.4), enabling the household to collect rainwater from the roof in a cistern for household use. Among the various types of pan- and cover-tile, other designs are occasionally found. For instance, a few examples resemble the opaion mentioned in textual sources – a tile with an opening to vent the smoke from a hearth. More substantial ‘chimney pots’ were also used, and an example has been found on a Classical house near the Agora at Athens. Elaborate, decorative, exterior fixtures include painted and moulded terracotta tiles and antefixes designed to decorate the roof, painted terracotta simas (panels which ran along the tops of walls beneath the eaves) and carved stone column capitals: examples of all these elements have been found in the large and ostentatious House of Dionysos at Pella (discussed in Chapter 7). Flat, clay roofs may also sometimes have been used for certain parts of the house or in particular building styles, especially for some of the smaller rooms or more modest structures. The main alternative to this kind of mudbrick construction was to build walls entirely of stone, a method particularly common in Crete and the Aegean islands. Stone is obviously a more durable material than mudbrick, although more, and more specialised, labour was required for quarrying, transportation and construction. In stone buildings, the roof was probably often flat, composed of wooden cross-beams and stone slabs with weatherproofing of compressed clay, as in the Geometric-period houses of Zagora on Andros.

Both mudbrick and stone houses frequently had open courtyards which were sometimes paved or cobbled. Floors were commonly composed of compacted earth which was sometimes topped with rolled clay. From the Classical period onwards more durable surfaces began to be provided, at first in only one or two rooms, and then more widely throughout the house. These consisted of cement, sometimes with inlaid pottery sherds or small pebbles. The earliest mosaic floors, introduced around 400 BCE, consisted of black and white pebbles placed in geometric or figural patterns; later they were composed of specially cut stone tesserae (small cubes) in a range of different colours. The decorative effect of mosaic floors was increasingly enhanced by plaster walls with designs in both true fresco and fresco secco techniques (that is to say, painted either before or after the plaster had dried). At first, simple panels were created in different colours, but by the Hellenistic period figural designs were being used as well as painted architectural features which were enhanced by moulded plaster (the so-called masonry style, a forerunner of Roman wall painting).

The transitions between the interior and exterior of the house, and between different rooms, were sometimes marked by thresholds. In earlier houses these were normally composed of small stones, but by the Classical period they were sometimes made from a single large, stone block, normally with cuttings where wooden doors would have been set. In stone-built houses door lintels and jambs were sometimes monoliths – single large blocks of stone, which retain the cuttings for bars and bolts. Doorways seem to have been one of the main routes through which light entered the interiors of these buildings. To some extent they were supplemented by windows, but window glass was not used until the Roman period and then only rarely. This meant that openings to the outside let in not only light, but also potentially rain, heat, cold or drafts. If there had been large openings to the exterior, passersby in the street would have been able to look in. In the later houses at Delos, which were built of stone and preserved to a considerable height, there are only a handful of window openings to the exterior: these have cuttings in their stone sills suggesting the placement of bars for security, and shutters which could presumably have been closed, making up for the lack of window glass. As we shall see in Chapter 3, by the Classical period, most houses had an internal courtyard which acted, among other things, as a lightwell, enabling daylight and fresh air to ventilate the interior through doorways and probably also through adjacent inward-facing windows. The remains of stone window mullions, carved in the decorative Doric or Ionic architectural orders (styles) occasionally survive. These are no longer in situ because the mudbrick walls into which they were set have long since collapsed, but they seem to have belonged to windows oriented inwards into the courtyard (as in the House of the Mosaics and House II at Eretria: see Chapter 6). Artificial light was provided by torches, oil lamps, hearths and braziers, but the amount and quality of such light must have been relatively poor, making daylight a valuable asset and one worth taking account of in house design.

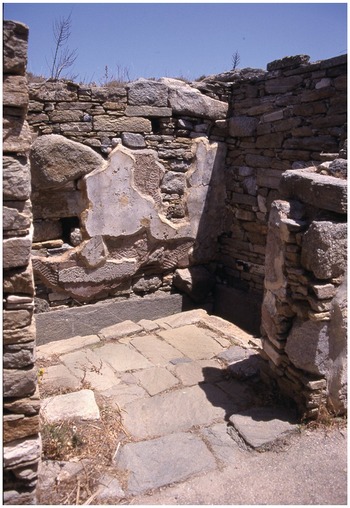

In comparison with the houses of modern, western society, those of the ancient Greek world had relatively few amenities. In addition to acting as a lightwell, the courtyard provided a bright and well-ventilated space for a range of economic activities such as processing crops or practising crafts including metallurgy, manufacture of ceramics or sculpting. Built-in features were limited in number and range. Raised stone ledges or benches against the walls provided seating or, in some houses of the early first millennium, supported storage vessels. Storage for smaller items was sometimes also provided by shelves or niches in walls. Another major fixed feature of some houses was a hearth consisting of an ash-filled area, sometimes demarcated by stone slabs (Figure 4.6). This was used for cooking, heating and lighting. Water was supplied by a well or cistern, normally located in the courtyard, although not every house had its own water source. From the Classical period onwards, some urban dwellings were provided with terracotta drains to carry waste water out to the street, and there were fixed toilets in some. Archaeological evidence dating to the late fifth and early fourth centuries BCE reveals ceramic vessels used for this purpose, as at Olynthos, where a urinal was found in situ in an exterior wall. A number of houses at Delos, which date to the second to first centuries BCE, are provided with small rooms enclosing multiple-seat toilets. This type of installation consisted of a wooden or stone seat with holes cut into it, above a channel along which water could be directed to carry away the waste. Archaeologically, it is this channel which typically survives (Figure 1.2). More often, though, terracotta chamber pots would have been used, and at least one terracotta object identified as a child’s ‘potty’ survives from the ancient Agora in Athens. From the sixth century BCE onwards, bathing sometimes took place in a terracotta bathtub (Figure 1.3). Such vessels had fixed locations but were not plumbed in; instead, they relied on water being poured in from smaller containers. The bather had only sufficient space to sit (with knees bent) on a raised bench at one end, rather than stretching out flat as in a modern, western tub. Water would have collected around the foot end and could have been scooped up again in order to wash the upper body. By the end of our period, bathing facilities in some locations were becoming more elaborate: in Sicily, for instance, a larger, cement bathing installation was sometimes fed with water heated by a furnace in a neighbouring room. Finally, from the fifth century BCE, if not earlier, some houses possessed upper storey rooms over at least part of the lower storey. These were supported on wooden beams set into the walls and were accessed via a stairway. In some cases flights of stairs may also have led from the ground floor up to exterior workspaces on flat roofs.

Figure 1.3 Replica of a terracotta bathtub in situ at Olynthos (house A v 6; a mend with lead clamps is visible).

The processes involved in planning and constructing these houses are difficult to investigate. Local resources and the environment must have played a role alongside social factors (as shown in Chapter 5). In many of the regions discussed in this volume the climate is warm and dry for much of the year, making it possible, and even desirable, to carry out domestic activities outdoors or in a roofed but well-ventilated space. In a few places where the climate is cooler or damper, such as the mountains of Epiros, courtyards were sometimes diminished in size. Further afield in culturally Greek communities on the northern Black Sea coast, the earlier houses were typically semi-subterranean, possibly mitigating against harsh winter conditions. Settlement location also to some extent determined the materials available: for example houses on the Aegean islands, where timber was relatively scarce but flat stones relatively plentiful, were typically built of stone, in contrast with those on the mainland, where mudbrick normally prevailed. At the same time, the topography of the settlement site must have influenced the size and form of houses to some extent, perhaps explaining the narrow, linear houses of Azoria and Kavousi Kastro (Chapter 5). Nevertheless, some communities adopted regular plans despite unfavourable terrain, as at Vroulia on the island of Rhodes (Figure 2.13). In some cases, significant investment was required to minimise such difficulties, as at Priene, where extensive terracing was used to facilitate the construction of a linear street grid and courtyard houses (Chapter 5). A further influence on the forms taken by settlements and houses was the history of the individual community: the city of Athens, for example, grew up over time, with irregular plans and oddly shaped house plots between (Chapter 3). But many cities which were newly planned and -built during the fifth and fourth centuries BCE were organised on a regular grid, with straight streets intersecting at intervals which produced rectangular ‘insulae’, or blocks of buildings, between, offering spaces for orthogonally planned houses. Inscriptions from Black Corcyra on the Dalmatian coast and from Pergamon, show how cities delegated responsibility for laying out areas of land and maintaining the urban environment, to individuals and groups within the community. This would have led to a co-ordinated approach to the planning and construction of housing. Such planning and oversight can be seen in the way that houses share party walls, not only in the new foundations like Olynthos, but also in established cities like Athens. It is unclear whether individuals were responsible for the construction of their own homes or whether the task was a specialist one. In the context of Olynthos, Nicholas Cahill has suggested convincingly that the creation of a row of houses was a collaborative project. The outer walls of each block were built at one time, necessitating co-operation. On the other hand, the styles of construction used for the socles were different in different houses, implying that several teams of builders had been at work. Cahill speculates that those teams consisted of members of the households planning to live in the houses, helped by their extended families together with friends. In such a situation, the final layout of the house would have been governed not only by the dimensions of the plot and the need to use drainage patterns which would fit with those of the neighbours, but also perhaps by the requirements of the first set of occupants. Jamie Sewell has argued, in addition, that economic and technological factors also played a role in shaping the houses at the site, and that structures which were of comparable size and similar layout were built because the materials for each house were provided in standardised dimensions and quantities. This is an intriguing idea and fits with the generally agreed upon hypothesis that the houses in question may have been built over a relatively short period to accommodate households moving into the city from elsewhere. Nevertheless, in relation to Olynthos, at least, it may overestimate the degree of formal similarity between properties. The layout and room dimensions are, in fact, quite variable, while it is actually the total area and common range of facilities that are the most striking similarities between the houses as a group. (Sewell’s theory may also overestimate the desire and capacity of the city to provide materials.)

The ‘family, friends and neighbours’ model is not the only way one could envisage the process of construction involving teams of workers: if an individual row of houses was to be built in a short time for incoming residents, teamwork might simply have been the most efficient method – involving either groups of future residents, or existing citizens anticipating the arrival of new settlers. The use of such construction methods in the Classical Greek world has been documented in monumental buildings through observation of masonry styles, while small numbers of inscriptions preserve contracts for constructing temples, showing that specific elements were allocated to different craftsmen. The identities of those who were involved in laying out and building houses like those at Olynthos and elsewhere will probably remain unknown and may well have varied from place to place and time to time. What this discussion shows is that a given house will potentially have been shaped by a variety of factors, including the personal preferences of individual households, the materials and time available, and the local historical or political circumstances, as well as more general cultural expectations. For archaeologists, the challenge is to distinguish these and other influences from each other by looking at the houses themselves and also by viewing them within their broader architectural, geographical and chronological contexts.

In addition to the architectural features of a house, excavation also uncovers evidence for the furnishings and possessions of its former inhabitants in varying numbers. In comparison with those one would expect in a modern western household, these ‘finds’ are normally relatively sparse, although they increase in quantity, variety and sophistication through the period covered here. Organic materials, such as wood and textiles, do not survive archaeologically except in rare circumstances, so the presence of such items as furniture and cushions usually has to be deduced indirectly. They are sometimes represented on painted pottery, and they are also listed on the Attic Stelai (inscriptions detailing objects confiscated by the Athenian state and put on sale as punishment following the conviction of the general Alkibiades and his associates in 415/14 BCE). Neither source is straightforward to interpret for various reasons: the text on the stelai is incomplete; the precise meaning of the vocabulary used is not always certain; and the documents may not have consisted of complete inventories of the houses involved. The images on pottery needed to be similar enough to the experience of viewers to be readily interpretable, but this does not mean that the furnishings they depict can be taken as in any way ‘typical’. These sources do, nevertheless, provide insights into some of the sorts of items that may once have been kept in some houses.

The stelai list a range of perishable goods including grain, wine, olives, olive oil and firewood, alongside containers such as baskets and boxes. Pieces of furniture include stools, chairs and tables. Other kinds of items may have a better chance of surviving archaeologically, including agricultural tools such as hoes and pruning hooks, which may have been made of metal. A few pieces of personal clothing are listed such as cloaks and sandals. In general, though, the lists highlight the contrast between attitudes towards property in the ancient Greek world and those of the modern west. The overwhelming majority of the items seem to be utilitarian and for the use of the household as a whole. It is tempting to wonder whether the owners of the household took away prized personal items before the property was confiscated, though this is a question we cannot, of course, answer. The images on painted pottery show rooms fitted out with similar furniture to that listed, with couches, tables and stools. Patterned textiles, particularly cushions, are a prominent element.

Archaeologically, the vast majority of artefacts found in excavated houses are ceramic. From the beginning of our period, these include vessels for serving, storage, and cooking, but also other items such as equipment for domestic cloth production (loom weights and spindle whorls). By the fifth century BCE, this range has broadened to include decorative elements such as wall plaques and architectural mouldings. The comfort and appearance of individual rooms would have been enhanced by the presence of the textiles mentioned above, which, in many cases, were probably produced by members of the household, and would have been used for cushions and throws. Small amounts of metal (mainly bronze, but also iron) served a variety of purposes, including fixtures or fittings such as nails, handles and door knockers and portable braziers. Bronze, silver and exceptionally even gold, were also used for items such as drinking cups and containers for mixing wine with water. Wood, ivory and bone were formed into boxes, pins, combs and other personal items. By the late fourth and third centuries BCE glass was occasionally used as inlay for wooden containers or furniture, and even for small perfume bottles.

As noted above, the number and variety of objects found in domestic contexts changes through time, with later houses generally yielding more, and more costly, possessions. But there are many exceptions to this generalisation since there are several other factors at work. These include the location of the settlement, the socio-economic status of the original occupants of the house, the circumstances of its abandonment, its state of preservation, and the aims and methods of the excavators. In practice, these factors will all have interacted to shape the assemblage surviving from any one house, but it is helpful to consider the potential effects of each one in isolation. Taking first the question of location: it seems that access to trade routes and raw materials may have affected the quantities of basic items present since there are certain regions in which, even as late as the third century BCE, households seem to have had relatively few possessions in comparison with contemporary households elsewhere. For example, in Olbia, a Greek city north-west of modern Crimea, there seems to have been a shortage of even one of the most basic domestic commodities of all – pottery: not only were the quantities found by excavators relatively small, but there were unusually large numbers of vessels which had broken and then been mended with lead, suggesting that they were valuable, or even irreplaceable.

In relation to the social status of the original occupants of the houses, throughout the period discussed in this volume the status and resources of a household will have been important factors in determining house size as well as the number and range of artefacts found within. At the start of our period, the majority of dwellings were small, single-room structures, with an average area of about 80 m2 and without surviving evidence of architectural elaboration. There is some variation in size, but while larger buildings may have been associated with wealthier individuals and/or households, the house rarely seems to have been used to symbolise status in a straightforward way. Elites asserted their social position through a variety of other means, including burials and, later, sanctuary dedications, as well as practices such as feasting. By the mid fourth century BCE, better-off members of society were investing increasing resources in their houses, creating larger structures with more rooms and more architectural decoration. As noted in Chapter 3, for many urban dwellers in the fifth and fourth centuries BCE, owning a house which conformed to a particular set of architectural conventions may have expressed citizen status, or at least, an aspiration to behave like a man of citizen status in a citizen state. It therefore seems to have been important to have a structure that ‘fitted in’ with those around it.

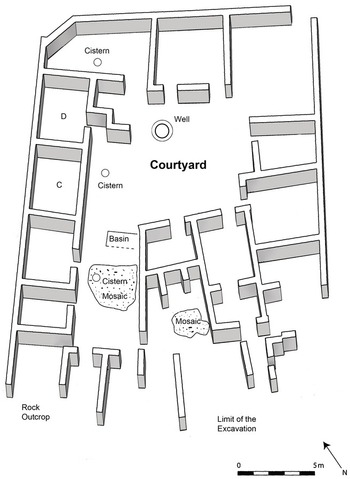

By the third century BCE, members of the elite routinely spent large amounts on building and furnishing their houses. At the same time, however, there must have been a considerable proportion of the population who continued to live in much smaller, less elaborate structures and with fewer possessions. Excavators have focused the majority of their attention on higher-status buildings. Poorer households are, therefore, likely to be under-represented archaeologically, but they can certainly be detected at a few sites: in the context of fifth-century BCE Athens, for example, the smallest houses discovered in the area around the Agora consist of only two or three rooms and an open courtyard. At Olynthos, a few house plots on the North Hill were subdivided to provide accommodation for several households at around the same date. In second- and first-century BCE Delos, recent work has emphasised the presence, alongside elaborate, wealthier residences, of a number of small establishments combining commercial facilities with modest residential accommodation (Figure 1.4). Textual evidence also points to the existence of ‘synoikiai’ – multiple-family dwellings or apartments, from at least the fifth century BCE. Such structures have yet to be positively identified archaeologically, but some forms of permanent or temporary residential accommodation are beginning to be isolated. A possible example is ‘building Z’ at the Kerameikos, which in its best-preserved phase (phase 3) some scholars have identified as a brothel (Figure 1.5). Even if this identification is correct, to judge from the array of domestic pottery, weaving equipment and personal items, individuals may have resided in the building at least for part of the time, while its scale also suggests the possibility that it may have served as a communal dwelling.

The circumstances leading to the abandonment of individual houses are highly variable and obviously help to determine what was left behind to be found during an archaeological investigation. In some cases, houses were vacated hurriedly with only limited time for residents to prepare, and perhaps little opportunity to take their possessions with them when they departed. For example, at Olynthos, historical sources tell us of the siege, capture and ultimate destruction of the city in 348 BCE by king Philip II of Macedon, who is said to have killed or enslaved all the inhabitants. In such circumstances the occupants are unlikely to have been able to carry away many of their things, but the houses may have been looted by Philip’s army and a few seem to have been burned. Excavators found evidence of the hurried abandonment of the city in the form of caches of valuables which had been buried under the earth floors of some of the houses. These included several hoards of coins and also larger items such as a portable bronze brazier. Although the final abandonment of the houses at Olynthos is likely to have been rapid, the circumstances meant that their contents may not have been organised in their normal fashion. Even the fixtures and fittings could have been affected: the historian Thucydides, describing the flight of the rural population from the Attic countryside during the Peloponnesian War in 431 BCE, mentions that the inhabitants took with them not only their household equipment but also the woodwork from their homes. The portability of structural components implied by Thucydides is borne out in the evidence from a number of inscriptions. Leases dating between the fourth and second centuries BCE for farmhouses, both in Attica and on the island of Delos, specify that wooden fixtures and fittings belonged to the tenant and they were, therefore, presumably removed at the end of the tenancy. Similarly, the Attic Stelai also include items such as doors and ladders.

Salvaging of fixtures, fittings, furniture and possessions is likely to have been more systematic where the occupants of a structure moved out in a leisurely, pre-planned fashion. The scale of such activities normally has to be inferred during excavation from the amount and condition of the material remaining: for example, at the Classical farmhouses in Attica near the Dema wall and near the Cave of Pan at Vari, the last inhabitants seem to have been particularly thorough in cleaning their houses prior to departure. Only small fragments of pottery remained in crevices in the bedrock, and at the Dema house even most of the roof-tiles were missing. At Athens there is some evidence that, as well as salvaging possessions, the process of leaving a house may have involved ritual activity. This may have introduced new configurations of material not characteristic of the house’s use as a dwelling: a number of properties excavated in and around the Agora yielded pyres in the floor deposits of some of the rooms. There is also, occasionally, evidence that while certain rooms in a structure may have been abandoned, others continued to be occupied (for example, in house C in the Athenian Agora, discussed in Chapter 3, a shop or workshop with direct access from the exterior seems to have remained in use after the remainder of the complex had fallen into disuse). It is possible that derelict buildings served as dumps used by the occupants of neighbouring properties. The process of abandonment would, therefore, have led not only to the removal of some items, but also to the introduction of others which were not part of the original domestic assemblage.

The abandonment process is thus likely to have transformed a house to a greater or lesser degree, depending on the circumstance of its final occupants’ departure, their level of resources, and the behaviour of neighbours (including whether the building was re-occupied at a later date). Other transformations will have taken place as the structure became part of an archaeological, rather than an inhabited, landscape. The extent to which structural elements, fixtures and possessions are preserved differs from site to site. A key influence is the micro-environment in and around a building. In most of the locations discussed in this book, there is a moderate amount of moisture in the air and soil. Under these circumstances organic materials such as wooden roof beams begin to rot even if they have not been removed. At the same time, mudbrick walls degrade very quickly once roofs and protective surface coatings are no longer in good condition. The individual sections of brick collapse and, in most cases, dissolve back into mud, leaving the stone socle which outlines the plan of the building but reveals little about its superstructure.

Where houses are built principally of stone, they are normally better preserved. The town of Delos (discussed in Chapter 7) offers a striking example: here, roof- and floor-beams have long since disappeared and the uppermost courses of stone have collapsed, but the house walls often still stand to a height of several metres, preserved beneath the stone tumbled from the upper parts of the superstructure. These buildings thus retain the openings for doors, windows and stairways, and reveal where structural alterations have been made, such as blocking doors or inserting additional walls which do not bond (are not integrated physically) with those of the original structure. During excavation, painted wall plaster is sometimes found on both interior and exterior walls, although exposure to air, rain and sunshine following excavation means that much of this has now disappeared. While at such sites organic materials like wood, food and textiles do not generally survive, it is occasionally possible to retrieve traces of foodstuffs parched by fire. These include grain, fruit seeds and olive pits; as, for example, at the large, fourth-century BCE farm site of Tria Platania, on the eastern slopes of Mount Olympos (discussed in Chapter 7). Here, large storage jars found in situ contained pips from grapes, while archaeobotanical evidence for a wide variety of other foodstuffs was also found in the soil, including wheat, olives, beans, lentils, peas, blackberries and cherries. In a few instances, fragments of textiles may also be preserved in charred form, although this is most common at burial sites where a body has undergone cremation (as in the male burial under the heröon building at Lefkandi, discussed in Chapter 2), rather than in domestic contexts. If the soil is not too acidic, animal bones and shells can sometimes also offer some information about food production and diet. For example, in the tower compound at Thorikos in Attica (discussed in Chapter 3), the excavators were able to determine that the inhabitants of one house ate pork and shellfish, discarding bones and shells under a staircase in the courtyard.

In exceptionally dry climates or in small areas of a site or building which have been serendipitously free of moisture, mudbrick can survive. At the Graeco-Roman village of Karanis (Fayum, Egypt) the desert environment has preserved the mudbrick walls of numerous houses to a height of several storeys. As with the stone walls at Delos, here archaeologists have been able to study details of the superstructure such as the locations of windows and wall niches, and also occasional painted plaster decoration. Wooden structural elements such as door leaves and window shutters are often preserved here as well, although the wood has lost its structural qualities, resulting in the collapse of beams supporting floors and roofs. Textiles and other organic materials are also present here, too, directly attesting to a variety of aspects of life which elsewhere have to be inferred indirectly. At the other end of the spectrum, wood, seeds and other organic substances can also be preserved where levels of groundwater are high. Saturation soon after the abandonment of a house excludes oxygen and prevents the action of bacteria which cause decomposition. Such situations are rare among Greek sites, but they do sometimes apply to small deposits like those found in wells, where groundwater has been consistently high since Antiquity. An example, excavated in the Athenian Agora (the main square of the ancient city) in 1937, contained two wooden buckets and a wooden comb, all dating to the Late Roman period.

A final consideration affects the interpretation of those artefacts which have survived and been recovered by archaeologists. It is tempting to regard objects found in different locations around the house as representing items left behind by the inhabitants as they went about their daily routines. This would mean that activities carried out in various locations could be ‘read’ from the items found there. In practice, however, there are a range of explanations for an item arriving at the spot in which archaeologists find it. It may, of course have been used there, but it may also have been stored there until required elsewhere. Furthermore, at the time a house was abandoned, an individual object may no longer have been being used for the purpose for which it was originally made: it could have been set aside as rubbish but disposed of within the boundaries of the house (for instance, in a pit under the floor or in a courtyard – as in the koprones or rubbish pits in the houses in Athens and at Halieis in the Argolid, discussed in Chapters 3 and 4) or it could have been intended to be stored temporarily pending disposal elsewhere. Given the relative scarcity of possessions, they must also have been intensively recycled – either intact or in fragments – for other purposes: at Olynthos, for example, a small, fine ware jug was used for mixing mortar to prepare a floor. Even broken pottery sherds had secondary functions – for instance as building materials – as in House I at Eretria (discussed in Chapter 6), where they were used in the mortar matrix of the walls, layered between the stone core and plaster surface. The observations of excavators in attempting to distinguish between artefacts deposited in connection with these different types of scenario are clearly crucial if artefacts are to be used to assist in reconstructing patterns of activity within the domestic context.

Past Research on Ancient Greek Housing

Regardless of the processes leading to the deposition of objects within a house or the effects of decay, the information recovered from any excavated house is heavily dependant on the aims and methods of the archaeologists carrying out the investigation. Until the late-nineteenth century little archaeological research had been done to uncover and understand the remains of the houses of Classical Greece. Early ideas about their architecture and organisation were, therefore, based on the ancient textual sources and on analogies with the extensively excavated remains of houses from Roman Herculaneum and Pompeii, in Italy. At the turn of the century, ancient Greek houses began to be excavated in increasing numbers. Substantial blocks of multiple-room houses with central courtyards were unearthed during large-scale campaigns at Priene, Delos and Olynthos (Map 1).

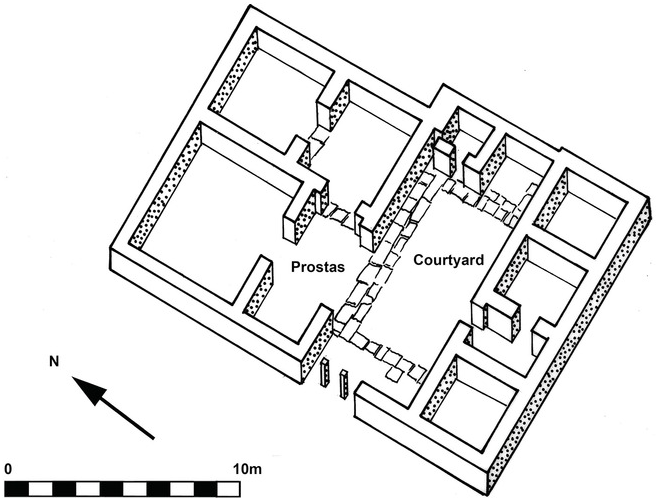

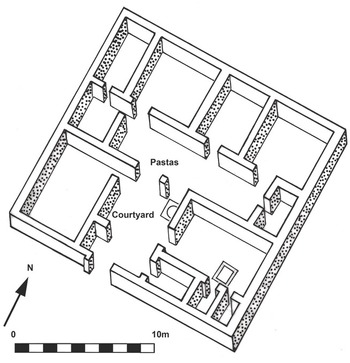

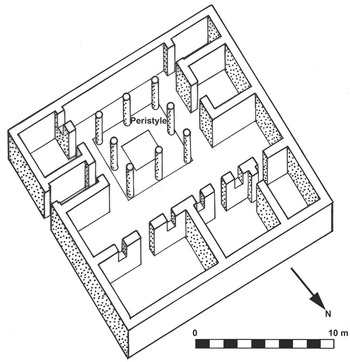

For most of the twentieth century the interpretation of these and other excavated sites continued to be dominated by a reliance on texts. Priene and Olynthos, in particular, were used as ‘type-sites’ to exemplify two different house designs whose patterns of organisation were said to correlate with descriptions given by the Roman architect Vitruvius. In the ‘prostas’-type, which is sometimes also found on mainland Greece as at Abdera, the courtyard and main room are articulated through a deep but relatively narrow porch, identified as Vitruvius’ ‘prostas’ (Figure 1.6 and see Text Extract 10). At Olynthos, by contrast, a number of the rooms are accessed via a broad portico, identified as a ‘pastas’ (Figure 1.7), which occasionally ran around all four sides of the courtyard to form a ‘peristyle’. As we shall see in Chapter 7, however, the peristyle-house is exemplified by a number of the larger residences on Delos (Figure 1.8).

The textual sources thus formed the basis both for distinguishing the types, and also for creating the labels that were associated with the various configurations of the physical remains. The word peristyle itself is derived from the Greek term ‘peristylion’, meaning ‘having columns all around’, a fair description of the courtyards for which excavators generally use this word. Terminology from the texts was also borrowed for other elements of the excavated buildings; for example, a variety of ancient authors mention a space called the ‘andronitis’ or ‘andron’, which is used for male drinking parties or ‘symposia’. Some black- and red-figure vases appear to show such parties (Figure 1.9), with the participants reclining on couches. A number of excavated houses incorporate one room (or, more rarely, several rooms) in which the floor has a raised border, and the door is placed off-centre, as if to accommodate couches along the walls. It seems a fairly good guess that such features can be associated with the surviving descriptions and images, and that these rooms can reasonably be termed andrones (the plural of andron). In the case of other terms, however, things are less clear-cut. For example, texts also make reference to a ‘gunaikon’ or ‘gunaikonitis’ – usually translated as women’s quarters – in opposition to the andron or andronitis. Yet it is unclear where such a space would have been located and what its features would have been. Indeed, it seems probable that the term does not refer to a specific room but rather indicates the domestic part of the house, away from the andron.

Being aware of the fact that the basis for applying some of these Greek words to the archaeological material is not always very strong is not merely a question of pedantry: the use (or misuse) of these terms can result in circular arguments and can be actively misleading since they can form the basis for assumptions about the role of a room in daily life. At the same time, the inhabitants may not necessarily always have used space in the way the builders envisaged, particularly where a house was occupied for several generations. The ancient vocabulary is, therefore, employed only sparingly here and texts are not relied upon to draw direct inferences about the possible uses of the rooms concerned. Rather, discussion of their roles is based directly on the architectural and (where available) artefactual evidence for the activities which may have taken place there.

The major campaigns of exploration at Olynthos and Karanis, both carried out during the 1920s and 1930s, were unusual in paying attention to housing at a time when most classical archaeologists were drawn to monumental religious and civic buildings like temples and theatres. As noted above, however, the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries also saw the excavation of significant numbers of houses at a few other ancient Greek sites, including Priene and Delos. The primary goal of the excavators was normally to explore the layout of individual structures and the way in which they fitted into the urban plan. Limited interest was also taken in the domestic artefacts – particularly as a means of dating a structure, or where they were perceived to be of intrinsic artistic interest. The work carried out at Olynthos and Karanis was well ahead of its time in that inventories were made listing some of the pottery, metalwork and other domestic artefacts uncovered, along with information about where in individual houses some of them were found. The stated aim of this approach was similar in each case and was relatively straightforward, namely, to provide a context for ancient literature. (The excavators of these sites were re-orienting the priorities of accepted archaeological practice quite radically. It is perhaps no coincidence, therefore, that the field director at Karanis, Enoch Peterson, had previously worked for the excavator of Olynthos, David Robinson, at his earlier excavation of Pisidian Antioch, in southern Turkey.)

Through most of the twentieth century, the goals of many excavators of ancient Greek houses remained relatively static, with priority given to understanding their architecture and layout. Increasing numbers of directors were, however, inspired to fuller recording of the associated artefacts, and particularly, the locations in which they were found, even if those data were not always fully published. This was particularly the case in the settlements of the early first millennium BCE. For example, at Nichoria (discussed in Chapter 2), which was excavated in the 1970s, sufficient information was recorded to enable a distribution map to be drawn up of the objects found in one structure, Unit IV.1. Towards the end of the twentieth century, the aims of studies of ancient housing began to shift. The influence of ideas from other academic disciplines (particularly household archaeology, first developed for analysing other cultures in different parts of the world) offered the possibility of using excavated houses in order to address questions about ancient society. In the early first-millennium contexts these questions included the nature of the social structure and the origins of later cult practices. For the fifth and fourth centuries BCE the character of relationships between the two sexes was a major issue. At the same time, the introduction of computers made the storage and analysis of data much faster and more straightforward, enabling (for example) statistical analyses of Robinson’s original data from Olynthos.

Scholarship on the topic of ancient Greek housing has been transformed since the late 1980s, when two landmark publications suggested in different ways, and on very different scales, that the forms taken by Greek houses were intimately connected with fundamental aspects of political and social life. This assumption has formed the basis of a variety of further work which has sought to re-evaluate excavated evidence as a means of addressing social questions. These studies have incorporated ideas and analytical techniques developed by archaeologists working in other cultural contexts. Today, it is clear that Greek housing can be used actively as a tool for understanding Greek society, rather than simply to illustrate social-historical accounts based on texts. This body of material offers unique insights into aspects of culture not addressed by written sources, a means of redressing some of the biases inherent in those sources by allowing access to the activities of a wider variety of social groups in a greater range of locations, and it enables a more dynamic view of change through time.

Large numbers of Classical and Hellenistic houses have now been excavated and studied, from locations across the Greek world. As knowledge has improved, it has become clear that there was considerable variety in scale and plan. Like the houses at Priene and Olynthos, many are organised around an open courtyard with the rooms entered individually via some kind of portico. One exception to this general pattern is a type of house known as the ‘hearth-room house’, which was identified and described more recently than the other types (Figure 1.10). Here, the layout is dominated by a large interior space featuring a central hearth and giving access to many of the other rooms. The courtyard is relatively small and typically only a few rooms open off it. So far, this type seems to have been relatively rare, being found on the central western Greek mainland (at Ammotopos and Kassope in Epiros – see Chapter 4) although houses from elsewhere sometimes include some of its organising principles. There has recently been a dramatic increase in the information available from the island of Crete, where there also seem to have been distinctively different patterns of spatial organisation from those found in other areas, with internal courtyards developing relatively late and being comparatively rare (discussed in Chapter 5).

The future promises an increase in the breadth and sophistication of the questions asked of the archaeological remains of houses, with associated demands on excavators to recover more information, for example comprehensive lists of artefacts and the locations in which they were found. At the same time, an important expansion is taking place in the variety of types of data, requiring more widespread adoption of a number of scientific techniques. These include analysis of fragments of bone and botanical remains, which reveal patterns of activity across the house and offer an insight into diet and foodways (among other things). At the same time, the introduction of soil micromorphology and geochemical studies is adding a new dimension, leading, for example, to improved understanding of the nature of early metallurgy and how it was integrated with other domestic activities. More widespread use of these and other scientific techniques in the field promises greatly to expand our knowledge of the range and organisation of domestic activities, and of the role ancient Greek houses and households played in relation to wider society.

Today’s excavation projects uncover relatively small numbers of houses in comparison with their predecessors. At Olynthos, for example, Robinson’s excavations fully or partially uncovered a total of approximately one hundred houses during only four seasons of work. Part of the reason this was possible was that, in common with many other directors of this era, Robinson had long field seasons and was able to pay for the participation of large numbers of local workers (for instance, his notebooks show that, during the 1928 season, there were two hundred people working simultaneously at the site). But it is also the case that projects carried out at that time neglected much information which is now regarded as significant and the collection of which makes excavation much slower and more laborious. For instance, today it is standard practice to explore the stratigraphy (the vertical sequence of deposits) making diagrams of the different levels as viewed from the side (section drawings), as well as horizontal plans. Such information is vital in enabling archaeologists to identify and distinguish between different phases of occupation and can even be used to isolate material coming from collapsed upper storeys. For example, both Ioulia Vokotopoulou’s work at Olynthos during the 1990s and the work of the more recent Olynthos Project have demonstrated that at least two different levels are potentially distinguishable in houses from the site. Nevertheless, no section drawing from David Robinson’s original excavation is included, either in his publication or in the original field notes. Even in terms of the recovery and recording of artefacts, in which he was so ahead of his time, Robinson would today be criticised: the small numbers noted from each room suggest that he focused on those which were largely complete, discarding others which, although fragmentary, may have held important information about the organisation of activity in a house. (For example, the number of ceramic items recorded from house A viii 10, including the unpublished items listed in the notebooks, totals 16, although in addition, two deposits were recorded as containing ‘much coarse pottery’; by comparison, the number of ceramic items recovered from house 7 at Halieis, excavated in the 1960s and 1970s, totalled around 6,230 and is estimated to represent the remains of at least 824 different vessels. The preliminary findings of the Olynthos Project in house B ix 6 suggest that it was particularly the coarse and plain pottery that Robinson’s team neglected to preserve or record, although Robinson left no indication of his criteria for retaining or discarding material.)

Despite the availability to today’s archaeologists of mechanised and computerised equipment, therefore, modern excavations are able to proceed at only a fraction of the speed of those of Robinson and Peterson. For example, exploration of a single Archaic house at Euesperides (modern Benghazi in Libya) by the Libyan Society during the 1990s took three field seasons. This slow rate of progress means that, at most sites, our knowledge is restricted to a much smaller number of structures. To some extent the effect of this can be mitigated by the use of new, non-destructive geophysical techniques such as electrical resistance and magnetometry, which, if soil conditions are right, can reveal the plans of unexcavated structures, as at the site of Plataia in Boiotia, where such work revealed the pattern of streets, building blocks and even the internal walls of individual structures. Similar results were obtained more recently at Olynthos by the Olynthos Project.

In the context of this book, one challenge in attempting to piece together the ‘big picture’ is to integrate the information derived from excavations which have focused on architecture, with that from the small number of projects which have had more ambitious goals and have published a wider range of information. It is unclear how representative our current excavated sample might be of the full spectrum of houses occupied by ancient Greek households. As noted above, there is likely to be a bias towards the recovery of houses belonging to higher status households, which must have been larger, more substantially constructed, and consequently, better preserved and more visible. These are also the structures which tend to be more attractive to excavators because they offer more information from which to understand the organisation of the original building. At the same time, they often contain features considered to be aesthetically pleasing, such as mosaics, whose discovery was, at least in the context of some of the earlier excavations, a major motivation for excavation. It is, therefore, likely that smaller, flimsier, low status structures are under-represented in our sample of excavated houses. At the same time, regional variation may have been obscured to some extent by the fact that the amount of excavation that has taken place in different parts of the Greek world varies. It therefore seems likely that as research intensifies and more data are gathered, an increasingly detailed picture will emerge of similarities and contrasts between houses in different regions or dating to different time-periods.