In a seminal article published more than thirty-five years ago, Footnote 1 Noel O’Regan compared the editions of three eight-voice motets by Orlando di Lasso (Confitebor tibi, Jam lucis orto and In convertendo) Footnote 2 with music manuscripts connected to the Chiesa Nuova, the church of the Congregation of the Oratory in Rome. Up to and including Wolfgang Boetticher, Footnote 3 musicologists had considered that these Roman manuscripts contained early versions of these motets, dating back to Lasso’s time in Rome in 1552–3, when he was in contact with Filippo Neri, founder of the Congregation of the Oratory. Footnote 4 They concluded that the Roman versions were closer to the composer’s intentions than the published editions. This initial assumption about the manuscripts, and the idea of a faithful copy compiled forty years later, were qualified by O’Regan, who demonstrated that these manuscripts contained not originals, but rather reworkings of the published versions, which had been prepared independently of Lasso’s will. The musical modifications consist in dividing the voices into two harmonically independent choirs, notably by removing the staggered voice entries and 6/4 chords. These handwritten enlarged versions testify to the growing popularity of cori spezzati in Rome, which O’Regan’s comparative study has helped to better situate chronologically.

Today, more attention is paid to the gap between written trace and sounding reality and to the rewriting and the plasticity of works; the transitional status of the writing is more readily considered in the flow of transformations that musical works undergo. The case of the polyphonic compositions of the Roman school – motets, psalms, antiphons, hymns and sequences to be sung either during liturgical services or at more informal spiritual meetings – is an excellent example of this renewed interest in philology, as the history of early polychorality is based in particular on comparative analyses of published editions and handwritten copies, with additional information from eyewitness accounts and payment records (including the remuneration of music copyists). Footnote 5 The study of the Roman manuscripts, and of how they were conceived, copied, used and circulated among the choirmasters, provides a better understanding of their origins and sheds light on the history of musical practices, since the manuscripts, intended for performers, bear the traces of use by musicians.

It is not known for which Roman church Lasso’s motets were adapted. Considering the manuscript anthologies in which these rewritten versions appear, they may have been copied for the Cappella Giulia, the Arciconfraternita della Santissima Trinità dei Pellegrini or the Chiesa Nuova, where much polychoral music developed. Footnote 6 It was for this congregation that the first Roman polychoral motets – which appear in Giovanni Animuccia’s Secondo libro delle laudi – were published in 1570.

In addition, the Oratory was a particularly active centre of arrangements of motets and masses. Footnote 7 Giovanni Francesco Anerio’s famous rewriting of the Missa Papae Marcelli by Palestrina, reduced from six to four voices, Footnote 8 is only one example among many. Several manuscripts from the congregation’s library contain spiritual motets, masses, laudi and madrigals that were rewritten, thereby modifying the polyphony and suppressing or adding parts. One of them (Rv O. 32), which belonged to Giovanni Giovenale Ancina, is a large eight-part manuscript by several hands, dating from the very late sixteenth century. It contains sixteen motets and twenty-four laudi, half of which were taken from Animuccia’s second book of laudi, and motets belonging to the Florentine Renaissance tradition. Though conservative in their texts and musical forms (with a preponderance of ballate grandi), some of them, initially for three or four voices, were reworked in O. 32 for a larger number of voices.

Here we can draw a parallel with the intense work done by this same congregation of largely erudite secular priests, who devoted time and particular care to copying and commenting on the sometimes monumental works of their confreres (such as the Annals by Cardinal Baronio), Footnote 9 expurgating texts and turning secular madrigals into spiritual ones. Footnote 10 These were then carefully reread, annotated and revised within a real scriptorium. Footnote 11

Noel O’Regan concluded his 1984 study by opening many perspectives on and questioning the authorship of the polychoral arrangements that were sung in one of the greatest Roman churches. Lasso, who had long earlier left Rome, could not be responsible for the revisions of his own motets, which were reworked and copied between 1580 and 1600. In addition, the manuscripts containing Lasso’s motets also contain later motets, both original ones by Ruggiero Giovannelli, Tomás Luis de Victoria, Giovanni Maria Nanino, Felice Anerio and others, and reworked versions of Palestrina’s and Luca Marenzio’s motets. Active at the time these manuscripts were copied, some of these musicians (such as Palestrina and Annibale Zoilo) could have been the authors of the reworkings of their own motets, as well as those of Lasso. Due to a lack of documentation, the history of these music books has remained unresolved, and it is still unclear who commissioned and copied this abundant musical material.

My aim here is to reopen this chapter in the musical and material history of the Roman manuscript books in the light of an unpublished document that provides valuable information on the way in which partbooks were conceived and compiled. The investigation has also led to possible new attributions and the results invite us to reconsider the multiple authorship in the constitution and transmission of the repertoire.

A MUSIC CENSOR’S ‘BEST OF’

During my research in the archives of the Congregation of the Oratory in Rome, and in particular in those of Giovanni Giovenale Ancina (1545–1604), Footnote 12 a scholar and polymath whose abundant manuscript archives have not yet been fully exploited, I found a small autograph notebook in the middle of a miscellany gathered under the generic title of canto ecclesiastico (Rf A. I. 35, c). This document had never previously been recorded in the archives of the Oratory of Rome. It contains lists of poetic incipits of madrigals, which successively classify vernacular vocal pieces by number of voices, then in alphabetical order, and finally by quires (quaterni and quinterni), ordering the pieces with a view to future publication. The patient search for poetic and musical sources, and the comparison with the works attributed to Ancina, led me to realise that these were the preparatory indexes intended to feed his great work, the well-known Tempio armonico Footnote 13 (of which only the first two parts were published). Simultaneously, these lists reveal the extent of the censorship project: they are indeed lists of secular madrigals he intended to turn into laudi and sacred canzonettas. Most of the titles show concordances with autograph notes by Ancina. Footnote 14

Musically, the expurgation takes the rather banal form of spiritual parodies of madrigals and canzonettas. Ancina’s action as a music censor is nevertheless fascinating, since this editorial work was linked to a pastoral approach in favour of spiritual music and the eradication of secular music, some episodes of which have acquired legendary status, such as his cutting up a book of madrigals by Jean de Macque Footnote 15 or the late ‘conversion’ of Marenzio on his deathbed. Footnote 16 These almost caricatured gestures were, however, the expression of an ethical and philosophical reflection on sacred music, which also led Ancina to become a counsellor for the Congregazione dell’Indice, which, at the end of the sixteenth century, was under the influence of the congregation of the Oratory. Footnote 17

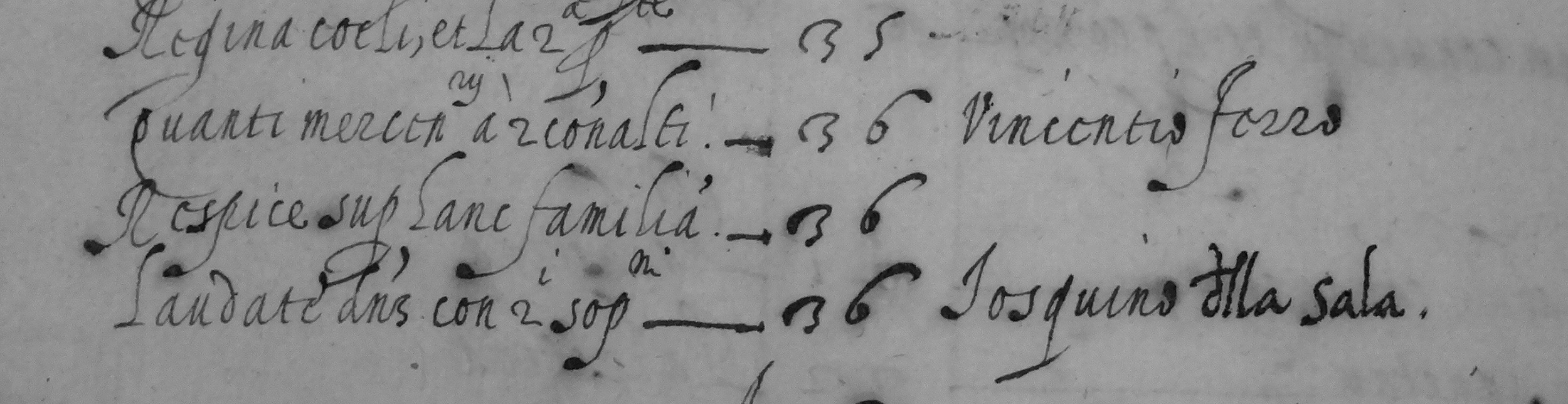

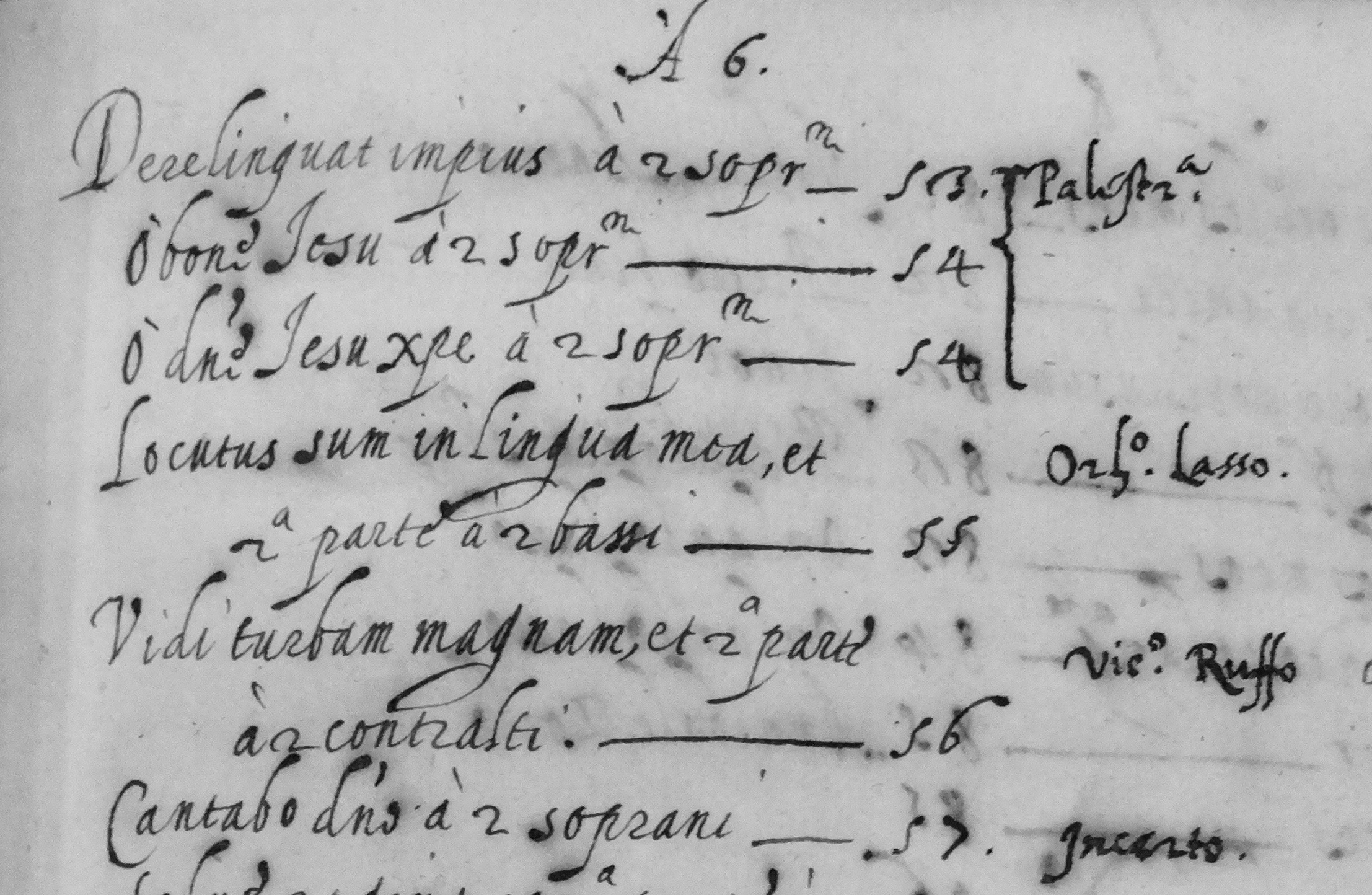

The initial title of the notebook Rf A. I. 35 c, added on the cover, announces laudi that are ready to print. Footnote 18 This has been corrected to another one specifying that there are also madrigals and motets (see Figure 1). Footnote 19 Indeed, the book also contains two further lists of motets, again in Ancina’s hand, but with no connection to the tables of spiritualised madrigals, nor to any kind of censorship: these lists simply occupy blank sheets of paper in the same notebook. An alphabetical table concludes the notebook (fols. 25r–28r), with an additional list on two unnumbered loose sheets (see Figure 2), entitled ‘Nota d’alcuni Motteti più scelti di diversi/da copiarsi trà quei di messir Prospero/che riescano più ariosi, vaghi,/et affettuosi per l’Oratorio’. This second list does not follow any of the organisational principles generally observed in motet books (i.e. by liturgical calendar or the number of voices), and could be the draft for an alphabetical table.

Figure 1 The title of Ancina’s notebook (Rf A. I. 35, c)

Figure 2 Ancina’s preparatory list of motets (Rf A. I. 35 c, loose sheets 1r–2v)

Collecting ‘the most beautiful motets for the Oratory’

How can we understand this choice of ‘the most chosen motets of various [authors] to be copied’ among ‘those of Messir Prospero’? The expression could designate motets ‘to be chosen from those of Messir Prospero’ (intended for Prospero Santini), but more probably means ‘to be copied to add to Messir Prospero’s repertoire’. The subjunctive ‘che riescano’ would then refer to all of Santini’s motets, and Ancina’s additions would help to make them more melodic, prettier and more moving (‘più ariosi, vaghi, et affettuosi’).

A Roman musician, ‘Prospero nostro’, as he was familiarly called by the Oratorians, was a central figure in the music of the Congregation of the Roman Oratory, where he seems to have been introduced by Jean de Macque, a personal friend of Ancina’s, in the mid-1580s. A lauda by Santini was published in a collective Oratorian book in 1588. Footnote 20 Organist at Saint-Yves-des-Bretons, Santini was named ‘brother of the house’ in November 1592, that is, a layman attached to the congregation of the Oratory, of which he became chapel master a few months later. This office provided for him to conduct the music of the church as well as that of the spiritual gatherings (the so-called oratories) and to perform the role of organist if necessary. He held this position from 1593 to 1602, when, although a layman, he was appointed Prefect of Music. For unknown reasons that may have been artistic, administrative or related to his secular status, Santini was dismissed a few months later, in July 1603, in favour of a perhaps more talented musician, the ‘Franco-Flemish’ Francesco Martini.

Of Santini’s works, the laudi are preserved, published in particular by Ancina in his Tempio armonico (1599) and his Nuove laudi ariose (1600). Dictionary records generally only mention his double-choir motet Angelus Domini descendit, on the grounds that it was published. Footnote 21 Yet, according to Ancina’s list, Prospero Santini is the author of at least five other motets. This is not surprising for a chapel master who served for ten years: rather, one would have expected a chapel master to have set many more motets and masses to music. If Ancina’s lists were indeed intended to enrich Prospero Santini’s repertoire, one might wonder why some of his own motets are included in the list. The purpose of the list was apparently not to introduce the chapel master to new motets, but rather to provide him with material: readable copies, perhaps arrangements, in separate parts, including his own works.

The title of these two lists indicates that the motets were intended for the Oratory. This polysemic term refers both to the congregation itself and to the ritualised spiritual meetings it promoted and organised. Some of these oratori were reserved for priests and prepared minds; others welcomed lay people. Open to the laity, the oratorio grande took place just before Vespers and included polyphonic music: polyphonic laudi and, in some circumstances, motets were sung, especially during winter vesperal meetings.

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, Oratorians tended to sing works with different numbers of voices in the same oratory, Footnote 22 but we do not know whether they were executed by a single choir or several. Testimonies remain imprecise. Despite the regular presence of instruments and the solemnity generally adopted during the winter period, no witnesses mentioned polychoral music during the oratories – even though Animuccia’s second book of laudi (1570) contains polychoral motets as well. It therefore seems difficult to establish whether the motets on Ancina’s list, many of which are polychoral, were intended for oratories or for the church, or both. After a date that remains uncertain, polychoral motets and masses were sung in the church of the congregation, the Chiesa Nuova, often with the collaboration of pontifical singers, during the most solemn offices: Easter, Christmas, the Nativity of the Virgin Mary and the feast of St Gregory, the patron saints of the church, and Saints Papias and Maur, whose relics were acquired by the Oratory, and whose feast was celebrated in a double service. After the death of the founder Filippo Neri in 1595, the anniversary of his death, on 26 May, provided an occasion for a spectacular display of splendour and was added to the solemn celebrations. In 1597 the decrees of the congregation for this occasion mention a ‘very solemn Mass, with music and four choirs, as never before sung not only in this church, but perhaps throughout Rome’. Footnote 23 In the following year, this commemorative Mass was embellished with a sermon by Ancina and a ‘very beautiful music’ with three choirs accompanied by a violin, trombones, harp and viola, conducted by Felice Anerio. Footnote 24 In 1599 the same Anerio composed a new solemn piece for three choirs. Footnote 25 It is not known precisely which motets were performed in these exceptional circumstances, any more than for oratorii and other spiritual gatherings, despite efforts to reconstitute the repertoire from the few musical sources preserved and the accounting records. Footnote 26

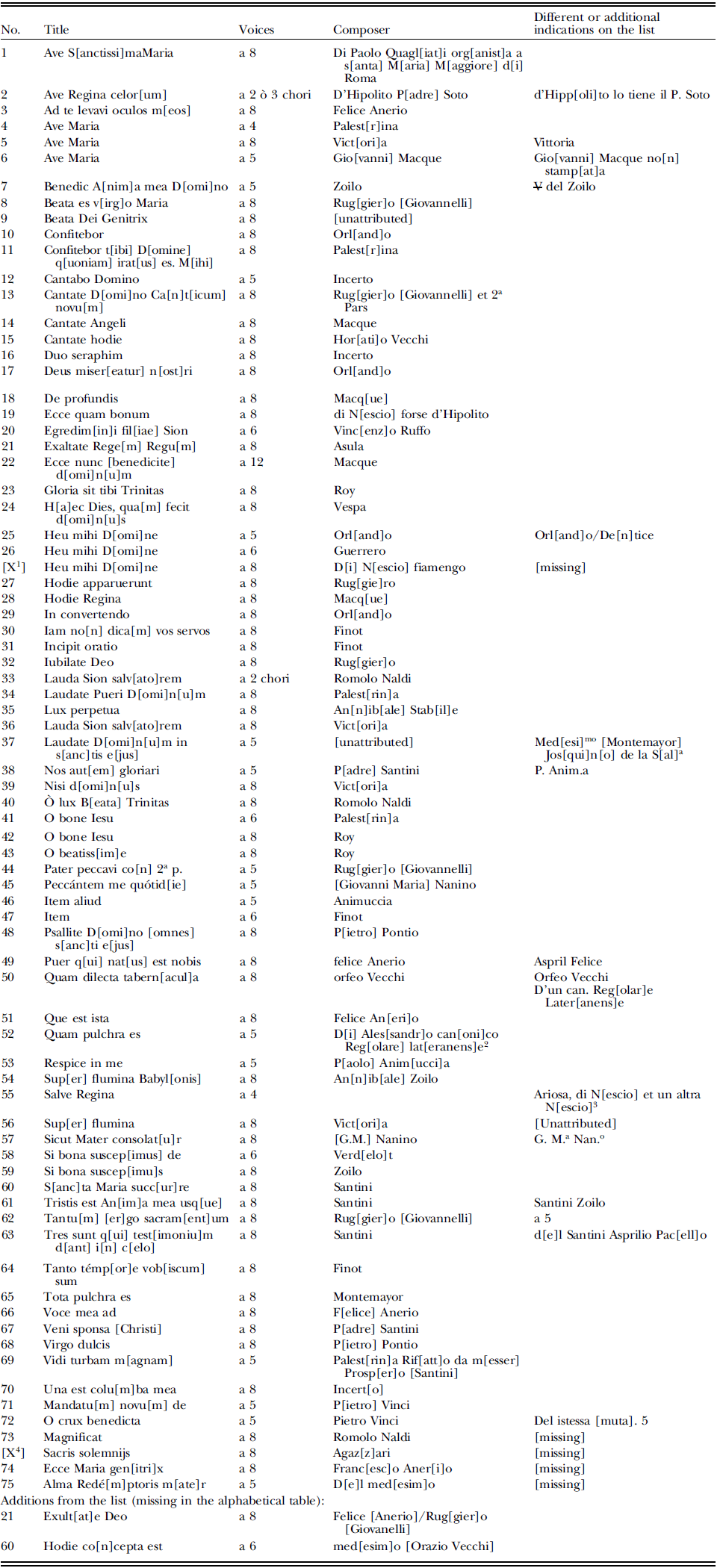

The list and the table drawn up by Ancina contain the same motets (seventy-four in the list and seventy-eight in the alphabetical table Footnote 27 ), but there are some discrepancies, probably unintentional (see Appendix, Table 1). They mention the textual incipit (often abbreviated), the number of voices and the name of the composer of each piece, with a few exceptions. This double list reflects the Oratorians’ interest in anthologies, which also characterises the three musical editions that have been attributed to Ancina. Footnote 28 It also illustrates the usual written way of passing on the motet: books of various authors, either printed or handwritten, were the most frequent mode of conserving, transmitting and disseminating the motet throughout the Renaissance – even if books by single authors played an increasing part at the end of the century.

Roman Musicians and Great Figures of the Motet

The eighty motets are the result of a selection made by a connoisseur, himself a musician working in the music chapels. Remarkable indeed are the number and variety of composers (see Appendix, Table 2). The majority are Roman or were active in Rome or Naples, where Ancina stayed from 1586 to 1596, playing a major role as an intermediary and promoter of church music. Footnote 29 These are often personal acquaintances of the Oratorian: Ruggiero Giovannelli, the brothers Felice and Giovanni Francesco Anerio, Jean de Macque, Cristoforo Montemayor and Asprilio Pacelli, as well as direct collaborators, such as Prospero Santini. Vernacular pieces by several of them also appear in Ancina’s Tempio armonico, exactly contemporary with these lists, and in his Nuove laudi ariose, published in the following year: works by Giovannelli, Nanino, Bartolomeo Roy (from whom he probably commissioned works) as well as Giovanni Animuccia and his brother Paolo, representatives of the previous generation, whose works he also republished. It is worth noting that Ancina did not select any Marenzio motets, even though he personally knew the musician.

Also present in this list of motets are chapel masters active in Rome such as Annibale Stabile, who had left the Urbs in 1595; Annibale Zoilo, who died in 1592; Romolo Naldi Footnote 30 and Paolo Quagliati, to whom Ancina refers by his position (‘organist at Santa Maria Maggiore’); and those from whose editions he republished several spiritual parodies in his Tempio armonico, Footnote 31 as well as the central figures Lasso (whom he did not know personally, but one of whose pieces he parodied Footnote 32 ), Palestrina, Tomás Luis de Victoria, and Francisco Guerrero, another Spaniard who passed, albeit briefly, through the Oratorian circles. Guerrero had been strongly supported by his compatriot Francesco Soto de Langa, a pontifical singer and pillar of the music of the Congregation of the Oratory, who had been in charge of editing his Liber Vesperarum. Footnote 33 As for Victoria, who had also left Rome, thirteen or fourteen years before Ancina drew up these lists, he had been a familiar of the Oratorians and close to Ancina. Copies of personal letters Victoria sent to the Oratorian priest are conserved in the archive of the Congregation of the Oratory. Footnote 34 At Ancina’s request, Victoria had dedicated to the Duke of Savoy his Motecta festorum totius anni, Footnote 35 which also contains a Latin epigram by Ancina. Footnote 36 And while in Naples, needing to provide the Neapolitan musical scene with good-quality music, Ancina insistently asked the Roman Oratorians to send him music by Victoria. Footnote 37

‘Ipolito’, who can be identified as Ippolito Tartaglino, Footnote 38 was also active in Rome (where he may have met Ancina) in the 1570s and in Naples in the 1580s. Footnote 39 Ancina refers to him by his first name, a sign that they were personally acquainted, as he does with Felice Anerio, Asprilio Pacelli and Ruggiero Giovannelli. However, he doubts the authorship of Ecce quam bonum. From Tartaglino’s works he also selected an Ave Regina celorum of which he did not have a copy at the time he drew up his list, since he indicates, in the margin of the title: ‘lo tiene il P. Soto’. We know of only one edition of Tartaglino’s music, dedicated to Alessandro Farnese and published by a little-known Roman printer, Giovanni Osmarino, in 1574. Footnote 40 The Neapolitan congregation of the Oratory, to which Ancina belonged for ten years, certainly had a copy to hand. Footnote 41 This book of motets for five and six voices in fact opens with an Ave Regina celorum. It is not known whether an Oratorian wrote a double- or triple-choir arrangement of this motet: no such version appears in today’s known musical sources. Footnote 42

In addition to these musicians linked, directly or indirectly, to Ancina, he also included works by lesser-known composers such as Josquino della Sala and the Franciscan Girolamo Vespa, active in Fermo, Osimo and Ascoli, whom Ancina probably met during the long journey through the Marches that he had just completed at the time he drew up his lists of motets.

Finally, the Oratorian selected works by composers from other geographical regions, mainly northern Italian composers: Vincenzo Ruffo, Pietro Vinci, Giovan Matteo Asola, Pietro Ponzio, Orazio Vecchi (whose madrigals Ancina intended to purify Footnote 43 ) and his homonym Orfeo Vecchi.

Like the anthologists of his generation, Ancina therefore selected both recent motets and older favourites such as Verdelot’s Si bona suscepimus for six voices. First published by Jacques Moderne in 1532, Footnote 44 it was one of the most widespread and frequently copied motets in the sixteenth century. Footnote 45 While its value as a model is sufficient to account for its presence in manuscript anthologies seventy years after its publication, or perhaps more, Footnote 46 its success with Oratorians was probably based on its Florentine connections as well: this motet, whose text is taken from the book of Job, was associated with the memory of Savonarola, as was Ecce quam bonum, taken from Psalm 132. Footnote 47 The first generation of the Oratory of Rome was faithful to Savonarola’s memory, associated with the republicanism of the Florentine diaspora in Rome. Musicians working for Filippo Neri, such as Giovanni Animuccia, himself a fervent piagnone, Footnote 48 may have contributed to the fortune of this motet in the Holy City. Footnote 49 Ancina’s affinity with this memory is confirmed by further pieces: an Ecce quam bonum by Tartaglino, and two settings of Si bona suscepimus: in addition to Verdelot’s Footnote 50 there is one for eight voices, which he attributes to Zoilo. A third one (anonymous, for five voices) is present in another Roman music manuscript copied in the same circles, Footnote 51 further proof of the link between this motet and the spiritual heritage of Filippo Neri.

Variety in the Music Pieces

The number of voices stated for each motet in Ancina’s lists also reflects a search for variety: fifty-three motets for eight voices, fifteen for five voices, eight for six voices, two for four voices, one for twelve voices and one ‘à 2 o 3 chori’. Footnote 52 The title of each of the two lists, which also announces motets for sixteen voices, is therefore incorrect, unless the lists are unfinished. Although not specified, a systematic analysis confirms that the number of voices is most probably that of the musical sources consulted by Ancina, who certainly copied out what he was reading or had in memory. The discrepancies between the list and the alphabetical table, which has the titles of the motets or their attribution (and, on one occasion, the number of voices) confirm, as do the corrections and the second thoughts, that these lists are a working document. A hasty and poorly written entry has added a Sacris solemniis by Agostino Agazzari.

Most of the eight-voice motets are by living composers, active in Rome and close to Ancina: Giovannelli, Macque, Victoria, Felice Anerio, Bartolomeo Roy and Prospero Santini, with additional older compositions by Dominique Phinot and Lasso. Well known to the Romans, and assimilated by Palestrina and Lasso, Phinot’s three motets Iam non dicam, Tanto tempore and Incipit oratio Hieremiae were then considered a model for writing for double choir, as those of Victoria would be in the following generation. For Ancina’s generation, the production of polychoral motets was rarely a result of the arrangement of earlier works. The majority of those he selected were originally polychoral and suited to the spatial venues that were used during the festive celebrations.

Ancina’s lists recall the principle that governs the drafting of the main manuscript anthologies of motets of his generation: juxtaposing the works of many different, though predominantly Roman, composers. In accordance with what can be observed more generally, the Franco-Flemish (but also Spanish) imprint on the motet in the first half of the century increasingly gave way to the influence of Italian composers, especially Romans. Ancina also combines the variety in the number of voices and the diversity of the texts and liturgical circumstances collated under the generic epithet of ‘mottetti’: the motets are associated with Psalms (such as Super flumina Babylonis, Confitebor, Quam dilecta tabernacula, Ecce quam bonum, Cantabo Domino, Ecce nunc benedicite), responsories (Quae est ista, Lux perpetua lucebit, Tristis est anima mea, Heu mihi Domine, Duo seraphim, Tres sunt …), Marian antiphons (Salve Regina, Ave Regina celorum, Beata Dei Genitrix, etc.) and non-Marian hymns (O lux beata Trinitas, Benedic anima mea Domino, Exaltate Regem regum), sequences (Lauda Sion), and Lamentations, regardless of their place in the liturgical calendar or the office during which they were sung. Motets for Easter Sunday Mass, such as Haec dies (Gradual) and Confitebor (Offertory), are mixed with pieces for Pentecost, the Holy Trinity (Gloria sit tibi Trinitas), the Blessed Sacrament (Egredimini filiae Sion), others sung at Christmas, mixed with motets per illo tempore. The absence of a liturgical rubric makes it impossible to determine the precise destination of all the pieces, but the majority were used in the liturgy, which confirms that Ancina was considering the repertoire of the church rather than (or as much as) that of the oratories.

At first glance, Ancina’s choices therefore seem emblematic of a particularly brilliant generation of composers of the Roman school and of the fin de siècle taste for eight-part motets, particularly evident in printed books of that time. He selected contemporary pieces which circulated among choirmasters who knew each other and shared common interests, but also works by previous generations of great masters of the motet, mixing conservative and innovative trends, as most Roman chapels did. In doing so, Ancina demonstrates a marked taste for polychorality. On closer inspection, however, his choice is not that ordinary: not all these composers had been in Rome, and not all were performed on a regular basis. Asola, Naldi, Vecchi, and even Verdelot were not or were only rarely present in Roman musical manuscripts. Ancina, who had an extensive musical library at his disposal, obviously knew their works. His choice could reflect his propensity to create extremely varied selections and, at the same time, some accommodate peculiarly Oratorian tastes – interalia by helping to perpetuate Savonarolian memory. Footnote 53

RELATED MUSIC COLLECTIONS

While this anthology provides information on the tastes of a scholarly musician of the late sixteenth century, it also raises many questions about the role of these two lists in the genesis of manuscript musical anthologies, their function, the sources that made them possible, and their future: was this considerable number of motets actually copied, or did it remain a vain wish? Was the intention to compile a new anthology of motets, to complete existing collections or collections in progress, or to draw up an idealised list which would not only select the best motets but also consciously reject others? Ancina’s lists do not correspond exactly to any known manuscript, but have much in common with several. Footnote 54

The Pateri Manuscript (Rsc G.792–5/Rn 117–21)

One third of the motets selected by Ancina are included in the ‘Pateri manuscript’, a large manuscript anthology by several hands copied between 1590 and 1600 that contains motets and paraliturgical pieces for four to twelve voices. Of the twelve original parts, nine have been preserved. Footnote 55 Fortunately, the missing parts of several motets can be reconstructed thanks to the partial copy of this manuscript drawn up in 1821 by the scholar and musician Fortunato Santini (who shares a name with the one mentioned in Ancina’s list), at the time when the complete partbooks were still kept by the congregation of the Oratory, before their confiscation and dispersion after 1866. Footnote 56

The manuscript contains 111 pieces classified by number of voices (see Appendix): ‘mottetti’ but also – something scholars generally fail to mention – five vernacular pieces for six voices: three laudi by Animuccia Footnote 57 as well as two spiritual madrigals by Marenzio and Philippe de Monte. Footnote 58 The manuscript is unfinished: its sections are separated by several pages prepared for music that remained blank. Moreover, though the first motets give the name of the composer, the more one advances in the manuscript, the fewer indications they bear. An incomplete index fills the first three folios of the canto primo part (Rsc G.792). It seems to have been filled before the music copy was completed, since the foliation does not correspond exactly to the contents.

Each volume is marked at the bottom left with the name Pompeo Pateri by the hand that completed the introductory table, which probably means he was the first owner. Pateri played an important role in the Oratorian community, which he joined in 1574. He left memoirs and, like other first-generation Oratorians, donated his personal library to the congregation. This collection of motets was most probably added after his death, just as were other books, both manuscript and print, mostly on spiritual topics, belonging to him. His set of motets was certainly copied in Chiesa Nuova circles, but we do not know if it was for use in the church or as Pateri’s own collection. Pateri was a music connoisseur. In 1582, he was in charge of training novices in plainsong. In 1589 Ancina wrote to him from Naples to get a copy of the Milanese edition of the motets of Matthias ‘fiammingo’ sent to him: Footnote 59 Pateri was therefore part of the circle of musicians of the Roman Oratory who shared, exchanged and circulated music books, especially between the Roman and Neapolitan congregations. He also participated in the private financing of a second organ, which was probably installed in the Chiesa Nuova in 1612. This costly acquisition made the Oratorian Church the first in Rome to be equipped with two organs placed face-to-face. Footnote 60 The main function of this second instrument (which may be the small organ still present in the tribune of the left transept) was to encourage the performance of spatialised polychoral pieces. This voluminous set of motet partbooks belonging to Pateri contains a significant proportion of polychoral works, tangible proof of the enthusiasm for polychorality.

At least twenty-one of the motets in the Pateri manuscript are listed by Ancina (see the Appendix). Such numerous concordances suggest further hypothetical matches. The five-voice Laudate Dominum selected by Ancina is probably that of Josquino Salespino, or Josquino della Sala. Considering the commonplace practice of arranging music, it can be hypothesised that other incipits in Ancina’s selection refer to rewritings (now lost) of motets present in Pateri’s collections with a different number of voices: might the five-voice Cantabo Domino that Ancina chose without knowing its author match the anonymous six-voice piece present in the Pateri manuscript? Is the anonymous eight-voice Duo Seraphim related to the four-voice motet by Victoria, present in Pateri’s manuscript and published by Gardano fifteen years earlier? Footnote 61 Does the Beata Dei genitrix for eight voices refer to Guerrero’s for six voices? No concordance can be established solely on the grounds that the motets are composed to the same text.

Errors and approximations, always possible in what looks very much like a draft, can complicate the search for sources, but also open up new avenues to explore. Ancina has selected a five-voice Respice in me by Paolo Animuccia. This motet does not appear in any known Roman manuscript. Footnote 62 The Pateri manuscript, however, contains an anonymous Respice hanc familiam tuam, also for five voices. Did Ancina commit a lapsus calami and confuse two very close incipits? All these hypotheses remain open, since Ancina’s lists do not include any music.

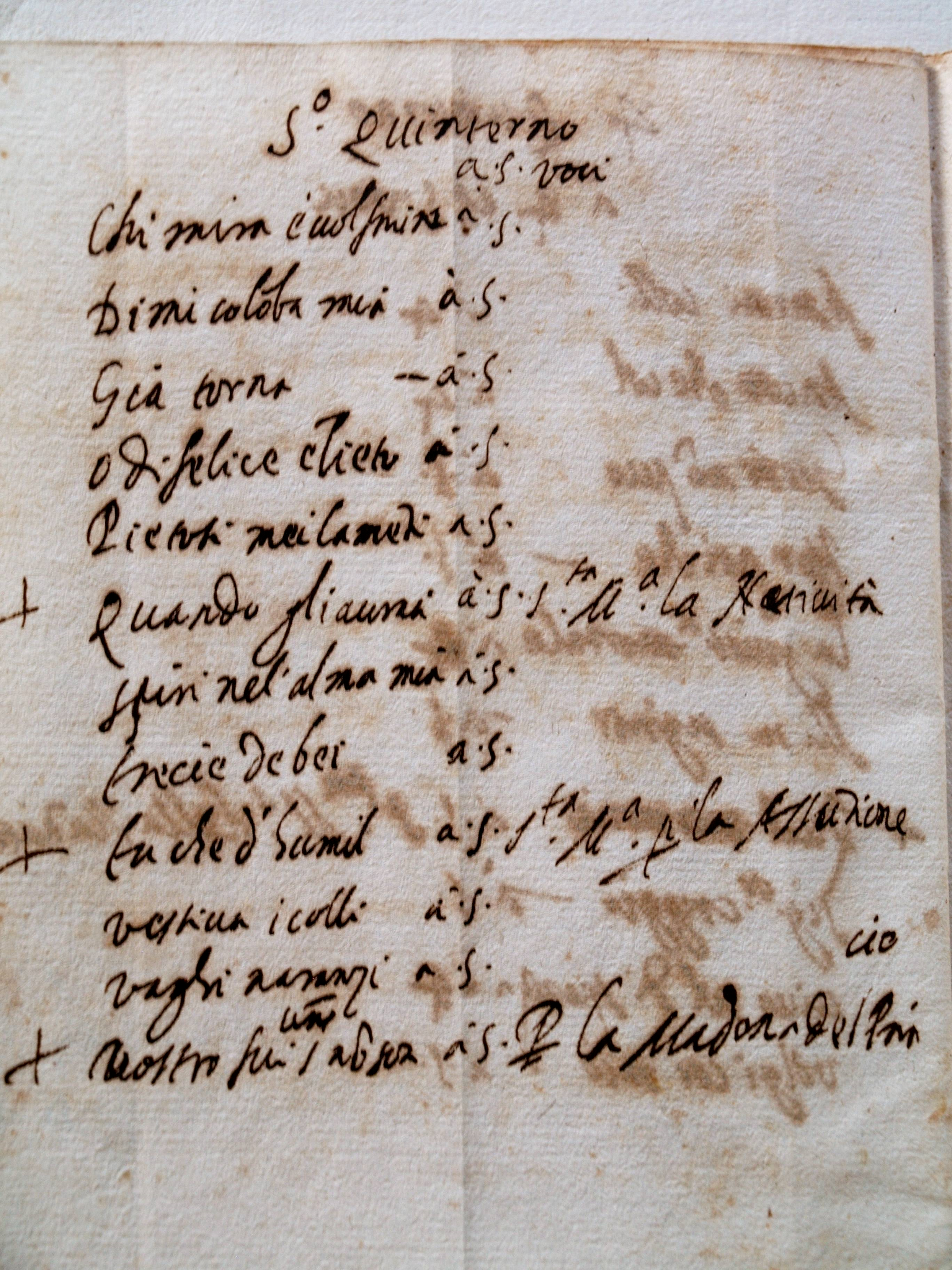

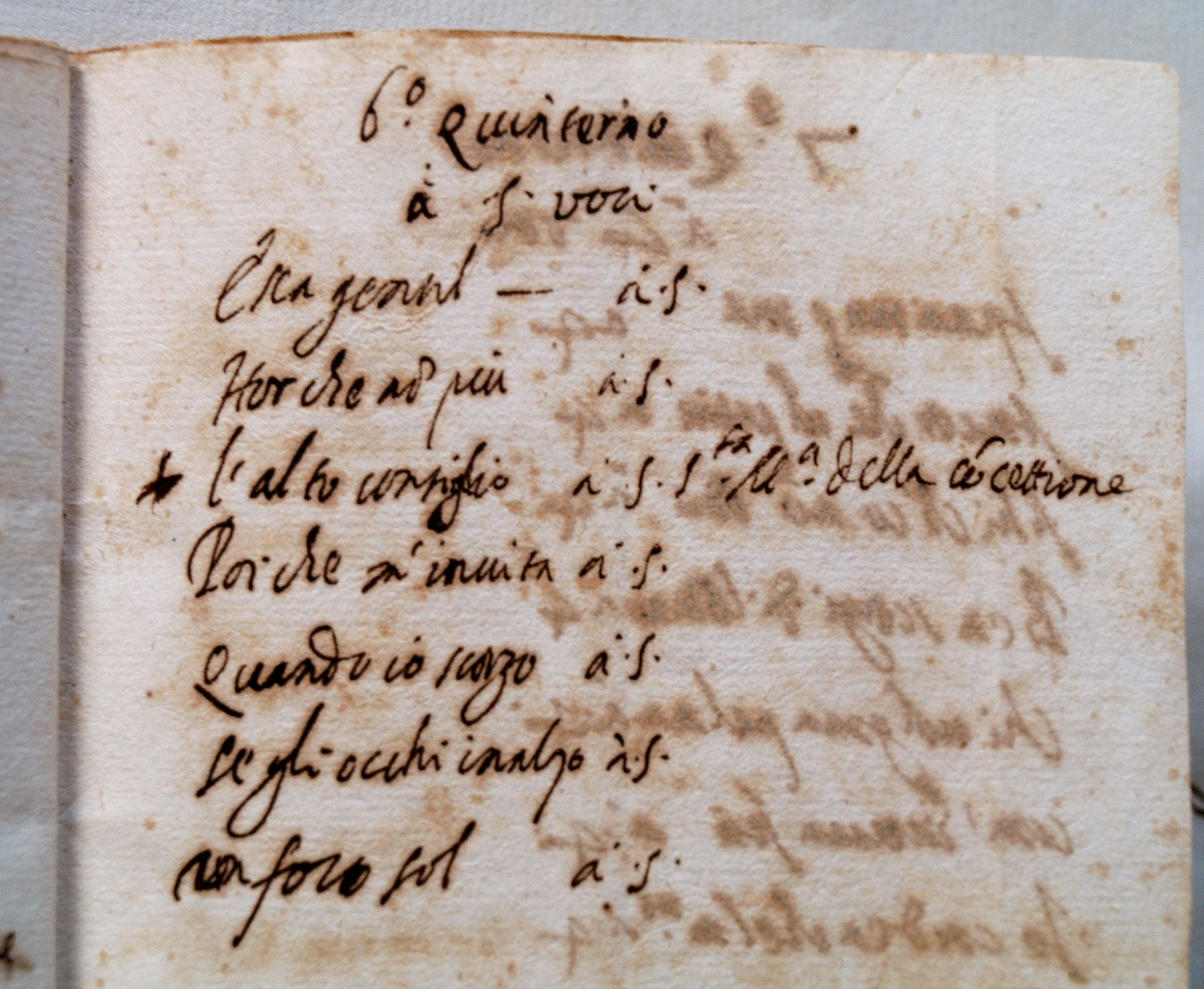

In any case, the certain concordances with the Pateri manuscript are so numerous that it would be tempting to consider it as the partial but fairly faithful realisation of Ancina’s project. One argument in favour of this is that he hesitated to attribute Ecce quam bonum. If he had had the Pateri manuscript in front of him, would he have hesitated? It seems, however, that this is what happened: this ‘forse’ reflects a doubt about the attribution he was reading when he drew up his lists. The Pateri set pre-dates – at least partially – Ancina’s list, and he used and even annotated it. The additions to the introductory table and some running titles, made by another hand in small writing in black ink, are without doubt in Ancina’s own hand (see Figures 3–5). The graphics and ink are exactly the same as in his motet lists. He most probably annotated the musical manuscript, and above all its table, when drawing up his list. Some hesitations confirm this. For example, he chose a Laudate Dominum for five voices, but does not indicate the composer in either of his two lists; in the Pateri manuscript, this motet is credited to ‘Josquino’. Ancina probably noticed the ambiguity and removed it after having read the music, by specifying ‘della Sala’ in the table of the book (Figure 4).

Figure 3 Rsc G.792, opening table, fol. 1r

Figure 4 Ancina’s hand on Rsc G.792, fol. 1v, excerpt

Ancina added to the table the names of several composers (Figure 5), clarified them (in the case of Josquino, the namesake of the famous Franco-Flemish master), corrected some poetic incipits, replaced others by the mention ‘2a pars’, removed a title (Hic vir despiciens by Guerrero) and then replaced it. In short, Ancina most probably made his annotations and corrections after the whole manuscript was copied. His interventions make up for the manuscript’s shortcomings: he attempted to improve the table, drawing up a selection at the same time. Indeed, some motets at the beginning of the manuscript’s index are marked with a cross, apparently by Ancina, who also used this method of selection in the margins of several laudi and motets in his autograph notebook Rf A. I. 35, c (see Figures 6–7). The fact that this beautiful manuscript belonged to Pateri was no obstacle to him. Ancina, a man of deep culture and singular character, did not hesitate to annotate other authors’ books, even to smear them with ink to the point of attracting reproaches and bitter remarks from his companions, some of whom were trying at all costs to retrieve their property from him.Footnote 63

Figure 5 Ancina’s hand on Rsc G.792, fol. 2r, excerpt

Figure 6 Rf A. I. 35, c [unnumbered page]

Figure 7 Rf A. I. 35, c [unnumbered page]

The ‘Mottetti di Anerio’ and Other Manuscripts

Rn 77–88, a manuscript in twelve partbooks from the archive of the Chiesa Nuova, contains 102 pieces for four, five, six, eight, twelve, sixteen and twenty voices. Footnote 64 Although it was later entitled ‘mottetti di Anerio’, it contains no motets by this composer; perhaps this set belonged to him. Though it shares repertoire with Pateri, it seems closer to the repertoire of the archconfraternity of Santissima Trinità dei Pellegrini and may have ended up in the Chiesa Nuova via Felice Anerio. Despite the date set by the national catalogue (‘17th century’), this manuscript pre-dates the Pateri partbooks and Ancina’s selection. It contains autographs by Zoilo, who had left Rome for Loreto in 1584. This ante quem date is not valid for the entire book, which is a collection in various hands. It has eight exact matches with Ancina’s lists (see Appendix, Table 3), one of which is lacking in Pateri. And we cannot exclude that Macque’s De Profundis, listed by Ancina among the eight-voice motets, is the one by this composer, for nine voices, preserved in Rn 77–88.

Rvat CG XIII.24 (olim Capp. Giulia 34), a manuscript in twelve partbooks (of which the third choir is lost), also contains a number of motets that overlap with the other two manuscript sets and therefore with Ancina’s lists. This could mean that the Chiesa Nuova – or at least Pateri – was keen to have music which was associated with the Cappella Giulia. These partbooks pre-date Ancina’s selection by about fifteen years; they entered the archives of the Cappella Giulia in 1584. Footnote 65 The handwriting and contents indicate that they were probably copied shortly before that. They contain four of the motets selected by Ancina, three of which are common to the ‘Anerio’ partbooks, which are almost contemporary with the manuscript.

Ancina’s lists also display four concordances with Rn 33–34/40–46, an untitled Footnote 66 set of thirty-five polychoral motets for eight to twelve voices. This collection, of which nine of the twelve separate parts are preserved, Footnote 67 is contemporary with the Pateri set (late sixteenth century) and with Ancina’s lists. Little is known about it, but O’Regan has suggested that it can be linked to the archconfraternity of Santissima Trinità dei Pellegrini. Footnote 68 As for Rn 77–88, it came into the possession of the Chiesa Nuova, but we do not know if it originated there or was conceived for use there. It should be pointed out that these four concordances are unique, as none of these motets appears in any other manuscript anthology.

Finally, Ancina obviously used books of single authors. Victoria’s Nisi Dominus comes either from the 1581 edition or from the partially autograph copy of Victoria’s antiphons (Rn 130) that the composer had prepared for the Oratorian Soto de Langa to publish and that remained in the Oratorian circles. Footnote 69 Similarly, one of the two four-voice Salve Regina settings listed by Ancina (one of which is described as ‘ariosa’) could be by Montemayor, from an autograph copy that this musician, active in Naples and Rome, had given him in October 1593. Footnote 70

Several concordances can also be found with later manuscripts and printed editions. Footnote 71 They testify to the permanence of the Roman motet repertoire, and are not of direct interest to research on Ancina’s lists.

Genesis and Chronology of the Manuscripts

The comparison between Ancina’s lists and the Oratory’s musical manuscripts sheds light on the respective roles of each of these documents. The manuscripts from the Chiesa Nuova do not necessarily reflect the repertoire in use there, since the archive inherited manuscripts from other communities or, more likely, from musicians and collectors. Each of them had their personal taste and conception of spiritual music and played a specific role – for example, though both Soto de Langa and Ancina edited anthologies, the former distinguished himself in musical editions of single-author books (by Guerrero and Victoria), while Ancina did not. It is therefore difficult to identify an Oratorian aesthetic in the sense of a community of tastes and a unified artistic policy, especially since the community was inspired by the principle of equality and independence of its members. Footnote 72 Nevertheless, musical concordances and several clues confirm that Ancina made his selection from several sources. In only one case did the Oratorian rely on his memory: in front of the Ave Regina celorum that he assumes to be by Tartaglino, he indicates ‘lo tiene il p. Soto’, a clue that he himself did not have it before his eyes. This is all the more significant as, at the time he drew up his list, Ancina was the librarian of the Congregation. He therefore had free access to the manuscript musical anthologies deposited by their owners. However, in this congregation of secular priests, the sharing of material goods remained limited. Most of the books, like paintings, were private property, even if they circulated among colleagues: this is the case of the Pateri set, not yet the property of the congregation, but which Ancina obviously used. In other words, he was aware of the existence of the manuscripts, had read them, but did not have them all simultaneously in front of him.

Print seems to have played a minor role in Ancina’s compilation work: the list specifies that Macque’s Ave Maria was not printed, which could suggest that the other pieces he listed were. In fact, apart from Vinci’s motets, which appear in Ancina’s list in the order in which they were published, and perhaps Lux perpetua by Stabile, Footnote 73 he seems mainly to have used handwritten sources. Many of the pieces he chose were unpublished and some (such as Salespino’s motets) remained so. In addition, books by single authors, collective editions and the vast majority of printed anthologies bore the composer’s name at the top of the pieces. However, Ancina, on several occasions, expressed hesitation, which confirms that he used handwritten sources instead. While the names left blank may be simple omissions, the mention ‘incerto’ proves that some authors were unknown or unfamiliar to him. Thus he attributed a motet to a ‘regular canon of San Giovanni in Laterano’; after hesitation, he crossed out this mention and handed the authorship over to Orfeo Vecchi. Similarly, in front of another title, he noted ‘forse d’Ipolito’: a doubt concerning a composer whom he nevertheless called by his first name. Ancina most probably did not refer to Tartaglino’s only edition, but to a manuscript now lost, or to his own memory.

Ancina’s lists, which were most probably intended to serve as the basis for a new anthology, therefore shed light on the process of collecting, selecting, classifying and, in some cases, rewriting musical pieces, operations of which the main manuscripts are the result. They also prove how firmly the constitution of the motet anthologies was based on the principle of addition, one manuscript being supplemented by others.

MUSICAL CONCORDANCES AND NEW ATTRIBUTIONS

Several motets in Rn 77–88 and in the Pateri set have no attribution. Some of them, whose composer’s name Ancina knew, were famous and concordances can be established with other musical sources, mainly printed. These attributions deserve to be added to the existing catalogues. The four-voice Ave Maria copied without a composer’s name in Rn 77–88 is none other than that of Palestrina. It also appears in the Pateri manuscript and in several published editions. Footnote 74 Similarly, Lasso’s Confitebor tibi is still considered anonymous in catalogues by the simple fact that it was copied without the author’s name in Rn 77–88.

The Pateri manuscript, on the other hand, contains both attributed and anonymous pieces, some of which can easily be identified: the Alma Redemptoris Mater is Palestrina’s. Footnote 75 The five-voice Mandatum novum, like the O crux benedicta that precedes it, is by Pietro Vinci, and was published in his Secondo Libro de Mottetti a cinque voci (Venice, Scotto, 1572). Indeed, it was added to Ancina’s lists under the name of Vinci. Footnote 76

In addition to these musical concordances, fresh attributions can be made. Several anonymous motets present in these manuscripts show no concordance with other music sources. Ancina’s lists are then of major interest. The similarity of literary incipits certainly needs to be supported by other elements, but it is nevertheless a reliable clue, all the more so as concordances are many and we now know that Ancina compiled his ‘best of’ from these sets of music. The eight-voice Sancta Maria, succurre miseris, anonymous in the Pateri manuscript, is most probably by Prospero Santini, as Ancina’s list suggests. The eight-voice Super flumina Babylonis from the same manuscript would, according to the same method, be by Annibale Zoilo. Footnote 77

This last case, however, is singular, since Fortunato Santini, scoring and copying most of the Pateri collection with the greatest care 120 years later, attributed this Super flumina to ‘Godmell’. Whom to believe? The contemporary musician, who lived and worked amidst the collections, or the great collector working at a distance of more than two centuries? Fortunato Santini sought to fill in the gaps in his source. Not only did he attribute the motets copied without the composer’s name, but he also modified several attributions that appear in the Pateri set. If several attributions of anonymous motets, particularly those of polychoral motets, are accurate, Footnote 78 many are wrong. Footnote 79 ‘Godmell’ is assigned eight motets in Santini’s copy, even though several are now attributed with certainty to other composers. Footnote 80 Ancina is partly responsible for this blunder perpetrated centuries after his death: in completing the Pateri manuscript, he attributed two motets to ‘Godimel’ (see Figure 3 above): a four-voice Da pacem with no author’s name and an Ecce nunc tempus admirabile that the table credited to ‘Mel’, an Italianised patronymic that refers either to Gaudio Mei (or Meli), a Provençal composer who made his career in Rome in the middle of the sixteenth century, Footnote 81 or to the madrigalist Rinaldo del Mel (1554–98), from Mechelen, which Ancina published in his Tempio armonico. As a consequence, Ancina decided by ascribing this motet to Gaudio rather than Rinaldo. Footnote 82 Fortunato Santini, 200 years later, extended this attribution to other motets, which incidentally reveals that he had trouble distinguishing stylistically different generations of composers. Fortunato Santini’s copies, however, are not sufficient to establish attributions. As far as the Super flumina Babylonis is concerned, the attribution to Zoilo therefore deserves to be considered likely.

CO-AUTHORSHIPS

The gaps between Ancina’s two lists, the hesitations about the number of voices of the pieces and the plurality of attributions nevertheless provide valuable insights into the plasticity of the motet and raise questions about what makes a piece of music’s identity.

If the textual incipits seem to be a reliable starting point for tracking motets, several elements obscure the identity of the compositions listed by Ancina. First, as already said, the Romans willingly adapted the number of voices of the music they performed – this is precisely the conclusion to which O’Regan’s study of Lasso’s motets leads. Ancina apparently reported the number of voices from the musical sources; the differences between his two lists and between the lists and the music books therefore raise questions about further versions that may have been reworked. Second, and here of greater importance, the name of the composer is not always clear. Ancina initially attributed the Puer natus est nobis which was to resonate under the vaults of the church for Christmas to ‘Aspril’, a name he corrects to ‘Felice’. Pacelli and Anerio were first cousins, and their careers crossed paths many times. Footnote 83 Did Ancina confuse them? He may also not have mastered the trade in music copies between the two musicians, both chapel masters and, as such, heavy consumers of polyphonic motets.

No hypothesis can be ruled out, but none has the value of a model, and each motet attributed to several composers, such as each riformato motet, must be examined in detail. Thus, when Ancina assigns the eight-voice motet Exultate Deo to ‘Felice/Rug.’, there is no evidence to suggest he was confused between Anerio and Giovannelli, since he was personally bound to both of them. Are we to understand that Giovannelli reworked a motet by Anerio? Or, more probably, that Anerio adapted a motet by Giovannelli for the Chiesa Nuova?

If the majority of the eight-voice motets in the Pateri manuscript were adapted to the polychorality in use at the Oratory of Rome, the same congregation, as has been said, was also making reductions. Palestrina’s Vidi turbam magnam, a six-voice motet published in 1569, Footnote 84 appears, still for six voices (CAATTB), in the Pateri manuscript. Footnote 85 Ancina did not select this version but its Oratorian avatar, a ‘Palestrina reformed by Messire Prospero’, reduced from six to five voices.

In fact, Ancina’s hesitations about the authorship of certain motets can be explained by this chapel master’s role as arranger. Several divergences between the list and the table concern Prospero Santini: Nos autem gloriari is attributed to Santini in the table, but to P. Animuccia in the list; Tres sunt qui testimonium for eight voices (sung at the Offertory of the Trinity, following Duo Seraphim clamabant) is attributed on one side to Santini but on the other to ‘del Santini Asprilio Paco.’, the first written over the second, which is underlined. The most likely hypothesis is that Santini adapted motets from Animuccia and Pacelli. In fact, Pacelli included an eight-voice setting of Tres sunt in his edition of double-choir motets of 1597. Footnote 86

Prospero Santini’s role revealed by these references in turn raises other questions. Following the logic disclosed by Ancina’s list, there is no evidence that the Sancta Maria, succurre miseris, which the Oratorian attributes to Santini, is entirely due to the Chiesa Nuova’s chapel master, who may once again have borrowed a motet and adapted it to the musical requirements of his own chapel. Even more: should the Veni sponsa Christi which Ancina attributes to Santini be considered lost, or is it an arrangement, by Santini, of Stabile’s Veni sponsa Christi present in the Pateri manuscript?

While he was not a prolific composer, Santini was therefore an active secondary author, quick to adapt pieces of music to the requirements of the congregation for which he worked. In addition, he may be the copyist, or one of the copyists, of these manuscripts.

CONCLUSION

From this monumental list, we first note the attributions: those of works, known elsewhere, by Lasso, Palestrina, Vinci, which deserve to be attributed in modern catalogues; but especially those which are totally new and which increase our knowledge of Annibale Zoilo and Prospero Santini, the man in the shadows who was nevertheless music master of one of the first polychoral cappelle musicali in Rome, the musician to whom the most beautiful motets of the time made their way, and whose talent as an arranger deserves recognition for the place he occupied in the ‘life chain’ of the works.

The case of Santini, rendered inconspicuous by a historiography combined with an anachronistic conception of the figure of the composer, invites us to consider the multiple ‘author-functions’ of the Roman motet – to use a Foucauldian concept particularly stimulating for studying the genetics of the Early Modern writing. Arrangements and rewritings obscure the first author’s figure in favour of a plurality of authorial figures and functions that still tend to be undervalued. While they often remain difficult to identify, the copyist, the arranger (and in this case we do not know whether they are the same), perhaps even the patron, play a decisive role in the creation of the motet, a musical genre dominated by a strong tendency towards recycling.

In the sixteenth century, composition (intended in its full etymological sense) always relied on existing material: textual sources, Footnote 87 but also musical ones, especially in the motet, undoubtedly the most complex and refined genre of its time, and suffused with intertextuality that drew upon veritable cultural networks. Footnote 88 Thus, if the composition itself is individual, it is nevertheless nurtured by multiple figures of authors, especially since imitation of the masters is of great value. Footnote 89 Taking into account this multiple authorship is just as effective for the material study of these music books. Writing a motet, circulating, interpreting, copying and conserving it requires a series of material and scriptural interventions on a work itself nourished by those that preceded it. It is as if the composer were to gather under his name a collective creation to which he gives form and meaning in a personal work, perhaps followed by a redistribution of authorship over the course of the operations, forming a cyclical process: proofreading and correction, copying and conservation, interpretation, arrangement, borrowing again, citation, composition. This shared dimension of creation and this readiness to rewrite and adapt, omnipresent among church musicians (and all the more so since they formed an organised community in Rome), reminds one of the semi-collective intellectual practices of scholarly circles, among which the Oratory, as has been said, held a prominent place. In either case, the boundary is porous between the composer, the copyist and the arranger.

This dynamic of adaptation and reworking – reflected in Ancina’s list, but above all in the many rewritings mentioned at the beginning of this article – made it possible to produce a large set of motets fairly quickly, especially polychoral ones. However, should we consider that the Romans’ enthusiasm for polychorality, by encouraging rewriting and adaptation, thwarted the composition of new pieces? Certainly not, since the ‘romanised’ Lasso, as the compositions on works by masters, colleagues, friends and cousins, Footnote 90 are undoubtedly forms of composition, or at least additional creations. As for the polychoral tropism that would have absorbed the creative energy, Ancina’s lists provide a qualified answer. Although posterior to all the manuscript collections examined here, motets with eight or more voices account for two-thirds of his lists, while the four-voice motets are almost absent. However, as far as they can be identified, most eight-voice motets selected by Ancina are not polychoral, but rather for single-choir voices. This balance lies halfway between the polychoral tradition represented by manuscripts 77–88 and 33–34/40–46, and Pateri’s much more diverse anthology, which contains half motets for eight or more voices (including a large proportion of polychoral motets) and half pieces for four, five or six voices.

In addition to this, comparing sources and considering their chronology highlights the effort of the Oratorian to ensure a great diversity of ages, styles and number of voices that could be used in various circumstances, which was one of the hallmarks of the chapel of his congregation. Such variety refutes the idea that the motet was subject to rapid change. On the one hand, the renewal required by the music chapels did not prohibit the reworking of existing works; on the other hand, the Oratorians, by combining seventy-year-old works and new compositions, manifestly had a very clear conception of the value of repertoire, demonstrably including a notion of heritage.

CNRS, IReMus, Paris

APPENDIX

Table 1 Transcription of Ancina’s alphabetical table (Rf A. I. 35 c, fols. 25r–28r) and discrepancies with the preparatory list

1Unnumbered.2This is presumably Alessandro Marino, who was a canon at the Lateran and who was named in the Bull of foundation of the Compagnia dei Musici di Roma.3This means there were two different Salve Regina settings by unidentified composers.4Unnumbered.

Table 2 Motets listed in Rf A. I. 35, c (by composer)

1Doubtful attributions are bracketed.

Table 3 Concordances between Rf A. I. 35, c and Roman sets of partbooks