Introduction

The Black Sea, known as Pontos Eukseinos in ancient times, has always had a multicultural structure. Throughout its history, it has served as an intercultural bridge and become home to religious communities, language groups, empires, nations, and states of different ethnicities. For these historical and cultural reasons, the cultural formation that has emerged with water acts as a “cultural canal” in the Eastern Black Sea region. In academic studies, what is aimed by turning our geographical view, which usually focuses on structures on land, to the waters and by considering the meaning of the “location” is to demonstrate how this view has changed over time and that the intellectual lines we draw around peoples and civilizations are much more amorphous and worth re-examining than we think.Footnote 1 When we consider any period of history, it is possible to observe that the water in rivers, lakes, and seas has enabled the development of trade networks, facilitated the exchange of goods and ideas, and taken a role in the formation of port cities. Thanks to the water, which affects the life around it in every aspect, new opportunities in agriculture have been discovered and new architectural typologies have been generated.

Method

David Harvey has explicated heritage as a process or human condition.Footnote 2 According to Rodney Harrison, on the other hand, heritage is the traditions and habits that constitute the heritage practices, collective identity, and memory.Footnote 3 Based on these definitions, it is possible to conclude that “heritage” is a tool for “transferring knowledge,” which has a counterpart in the entire history of humanity. While this tool enables us to establish healthy ties with the past, it also guides us to carry our cultural codes into the future. The idea of cultural landscape as an element of the concept of heritage, on the other hand, is in a wider range than the idea of “site” and creates both a conceptual and physical space for the layering of competing values and meanings.Footnote 4 Natural and man-made water landscapes encompass the power of water – that is, water as a means of energy production and a destructive force, its place in the philosophy of life, and its role in the perception of built spaces.Footnote 5 Even though the issue of natural heritage has been brought to the agenda by many expert organizations in the process dating back to the 2010s, the coexistence of water and heritage, which is a part of this issue, and the impact of water on life have not been considered within the framework of this heritage. This drawback has led to the failure to document the problems on the subject and the emergence of new risks due to the neglect of the subject.

This article draws attention to the value of water as a piece of heritage and how these values should be integrated within the cultural landscape in order to be perceived as a natural heritage and to give it a longer life. Furthermore, the study focuses not only on the protection and recovery of cultural and water heritage but also emphasizes the development of proposals to ensure their sustainability. Similarly, in the context of these concepts, the risks that will arise if the water values of the Eastern Black Sea region are not protected have been debated. Furthermore, the relationship between the subject of water heritage and the concepts of dispossession, the right to landscape and local activism, cultural diversity, which have emerged through the evaluation of the findings obtained by reviewing the international legal/policy texts and literature, is one of the areas to which this study draws attention.

As far as the works created by the combination of nature’s production and human labor together are concerned, they explain the nature of society and the evolution of settlement.Footnote 6 At this point, the cultural landscape is situated in a critical position at the interface between nature and culture, tangible and intangible heritage, and biological and cultural diversity. The tangible and intangible elements of the water landscape in the Eastern Black Sea region are very important for the culture of the region. This distinctive water landscape emerges in recognition of the embodied culture and history.

The concepts of cultural landscape and rural landscape are composed by the joint contributions of human beings and nature. While protecting these areas, a sustainable approach should be adopted that keeps the development and changes of the areas under control by providing a holistic perspective. The conservation of cultural landscapes should focus on the “management of change,” aimed at creating a future in which the past plays a convenient role.Footnote 7 One of the issues debated in this study is the development of the protection of water landscape/water heritage, which is one of the cultural landscape areas, and the “conservation of water, heritage and nature together,” based on national and international texts. In the first conference on “Water and Heritage,” organized by the International Council of Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) in The Netherlands in 2013, the concept of water landscape was highlighted in the Amsterdam Declaration, and the new approaches created by this concept were also investigated in this study.Footnote 8

The Amsterdam Declaration was signed at the end of the ICOMOS Amsterdam Conference, which was organized with the aim of “creating public opinion about the water and heritage awareness shield” and “building bridges between the water and culture sectors to protect the world deltas.”Footnote 9 Since 2015, books on water and heritage issues, supported by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and ICOMOS, have been published as a guide in this study and deal with different issues and strategies related to water and heritage: Water and Heritage: Material, Conceptual and Spiritual Connections, published in 2015; Cultural Heritages of Water, published in 2017; and The Cultural Heritages of Water in the Middle East and Maghreb, which was published in 2020 as Adaptive Strategies of Water Heritages: Past, Present and Future under the direction of ICOMOS Netherlands. Even though the area was scanned in general terms in these studies, areas such as water and energy production, natural water landscapes, water-related narratives, education, and legal issues were not mentioned.

Possession of a rich water heritage is a substantial factor in choosing the Eastern Black Sea region as a study area. The fact that there are few studies in the relevant literature on the subject in which “natural water resources” and “water and energy production” are associated with heritage has been instrumental in the selection of this subject. Furthermore, according to the scale in the Statistical Regional Units ClassificationFootnote 10 in the Decree of the Türkiye, Level 1 refers to the Eastern Black Sea region; Level 2 refers to the Trabzon subregion; and Level 3 covers the region consisting of Trabzon, Ordu, Giresun, Rize Artvin, and Gümüşhane.Footnote 11 Even though the Eastern Black Sea region seems to be at the center of this article, which deals with common and similar heritage and landscape values, Artvin, Rize, and Trabzon have been focused on due to the intense risks and dangers to the water heritage in these areas. The culture of the so-called “subregion” has been shaped by the region in general. The fact that this region is Türkiye’s second largest water basin is the most important factor that gives the region the above-mentioned features.

In the present study, the question of why water is a vital resource for the region was asked again in order to obtain new answers, the values of the region that developed with water were documented, the “water heritage” components in the region were identified, and their importance was emphasized. In this region, the existing risks arising from the neglect of heritage and the new risks that may arise as a result of continued neglect will be identified. In this study, the importance of a holistic approach, along with its requirements, is emphasized in order to preserve the natural beauties and sustain the cultural heritage in the Eastern Black Sea region.

Threats to nature in the region and risks in the region

Landscape is a dynamic system that is constantly being transformed under the influence of natural processes and social needs and a layered entity that connects the past to the present. The landscape is always open to significant changes, even without human intervention. A cultural landscape cannot be preserved unchanged.Footnote 12 However, human-made interventions with the intention of causing direct harm or indirect interventions can cause irreversible damage and losses in the landscape. There is no doubt that water is the primary source of life for all living things, and its existence is imperiled every moment. It is expected that climate change will increase floods and droughts, affect groundwater and sea levels, and cause disasters with higher frequency and severity.Footnote 13 When all these reasons are listed, the necessity of protecting water resources and issues such as access to water, water safety, and water culture gradually become more and more important.

Due to the topographical nature and rainfall intensity of the Eastern Black Sea region, the risk of flooding, overflow, soil erosion, and landslides is significantly high in the region. These risks increase exponentially every year. Even though the risk of landslides has been recognized, rural settlements in the region have been established on the banks of streams and rivers and on the foothills of the mountains, and they continue to be established. Erosion occurs in 96 percent of the Eastern Black Sea lands, and severe erosion constitutes almost one-half of this issue.Footnote 14 Besides natural disasters, problems in land use and distortions in the organization of nature-human relations has also caused very delicate and important ecological problems. For instance, since hazelnut and tea sprouts are planted for plantations in some of the forest areas that can hold soil and water, the planted areas cannot fulfill the same function as the forest.Footnote 15 When we consider the decisions that have been made with respect to settlement in the region, it is clearly seen that water does not always have positive results on settlement areas.

In recent years, due to road construction works, small pebbles have been removed from streams during rehabilitation and construction work near the roads. The “Green Road” project, which is aimed at connecting the plateaus as a tourism investment, started in 2005; however, this project has damaged the nature of the Eastern Black Sea region.Footnote 16 The new road in question has not only prevented people from reaching the sea and closed down their connection with the sea, but it also broke off the connection of settlements with each other. The increment in the construction of highland roads causes these roads and the roads between the highlands to be exposed to heavy traffic in the summer months, and the excess usage causes tourists to turn to these roads and to transport users to the plateaus above their capacity. The fact that the region is accessible to more local and foreign tourists than it can sustain causes damage in terms of the cultural and natural beauty, even though it makes a contribution to the financial development of the region (see Table 1).

Table 1. Values and risks associated with the water heritage of the Eastern Black Sea region

The richness of the region in terms of water resources creates advantageous conditions for the hydroelectric power (HEP) plants. The presence of a more regular flow regime than other regions and dense river network formed by impermeable groundFootnote 17 make the region an important center for small-scale HEP plants. While nearly 20 HEP projects were developed by the State Hydraulic Works (Devlet Su İşleri or DSI) in the Eastern Black Sea Basin before 1989,Footnote 18 today, 125 plants are in Trabzon (Artvin ranks second in terms of HEP density), while the number of HEP projects in the Eastern Black Sea has reached 350.Footnote 19 Due to HEPs and stone quarry works, the trees and plants in the region have been damaged, streams have been drying up, the population of forest and sea creatures has been decreasing, and water resources have been lost. During the HEP construction process, the natural beds of streams and rivers have been diverted without considering the reports written by scientists on the subject. As a result of these interventions, the location of the stream beds has been changed and the quality of the water has been degraded. Another change that has been observed in the natural life of the region is the deterioration of the structure of water, air, and soil due to more HEP plants being built than the area can sustain as well as newly opened stone quarries and mining operations. Furthermore, some other practices that harm the natural vitality of the region have been increasing the risks on the region.

Mining enterprises are those enterprises that have been allowed to operate the most in these forested areas.Footnote 20 Due to the gold mine that opened in Artvin, drinking water resources and the lands of the settlement area near the stone quarry were damaged. Even though the public reacted against it, the practices continued. The works to open a stone quarry in İkizdere are still underway despite the protests and objections of the villagers.Footnote 21 The nature, vitality, and biodiversity are being damaged in tunnel work throughout these mountainous regions, and the loss of natural and cultural heritage has been accelerating irreversibly. Currently, global climate change, pollution, and changing political and social patterns is impacting both the water sources and heritage at various levels.Footnote 22 This is another aspect of climate change that needs to be considered in terms of its impacts on the natural heritage, along with its causes and consequences.

New insights brought about by the water landscape and water heritage values

According to Cornelius Holtorf and Graham Fairclough, the issues such as the expansion of the concept of heritage and the diversification of landscape and cultural heritage provide an opportunity to understand the history of environmental and landscape changes and, therefore, to model the future scenarios in this regard.Footnote 23 The concept of “water heritage” is a concept that emerges when considered in the context of endangered water resources, water-related heritage, values and structures, the above-mentioned risks, problems and processes, cultural heritage, or cultural landscape. This context entails framing water by associating it with the concept of conservation. Henk van Schaik, Michael Valk, and Willem Willems similarly have emphasized the vital importance of water-related heritage for the conservation of cultural and natural values.Footnote 24 According to Diederik Six and Henk Schaik, on the other hand, water heritage can be defined as a concept that includes all components of the relationship that people have established with water since their existence.Footnote 25 Many issues such as water infrastructure, water management, irrigation and supply of drinking water, water conservation, architectural structures related to water, landscape associated with water, belongingness of water, traditions related to water are all associated with the concept of water heritage. The concept of water heritage is rooted in the nature and culture.Footnote 26

The development process of the concept of water heritage in international principles

The water heritage systems in the world consist of physical and functional structures, conceptual and organizational principles, and cultural and spiritual values. Water is an integral part of architecture and urban design, cultural identity, historical experience, public participation, entertainment, and tourism. The potential of water to connect the living heritage sites, the capacity of water-related heritage to connect the past, present, and future, and the role of water as a heritage in spatial developments, landscape design, and urban planning should be taken into account for a sound assessment of the subject. Carola Hein and colleagues have highlighted the need to re-evaluate the long-standing relationship with water, culture, and built heritage, and they have emphasized the importance of history and heritage as these relationships are redesigned.Footnote 27 According to Six and Schaik, within the scope of the concept of water heritage, the work, situation, or perception that emerges as a result of the relationship between water and society should be evaluated as cultural heritage, and the water resource itself should be considered as natural heritage.Footnote 28

Water heritage is present in the areas that are closely linked to traditions and narratives.Footnote 29 Water heritage often sheds light on how a society functions as a whole. In fact, it is worth noting that the water heritage is often a modest repetition of local elements of everyday life belonging to ordinary individuals.Footnote 30 Hein and colleagues mention that water-related heritage contains, preserves, and transmits water-related best practices, worst disaster events, history of water systems, and cultural memory.Footnote 31 According to Henk Ovink, “learning from past” is not only looking back but also looking forward.Footnote 32 Accordingly, tracing the existence of water, the inventions on this subject, and the struggles to manage water – thus, “learning from the past of water” – makes this concept all the more important.

Even though the daily water use structures, where social life and periodic practices are maintained,Footnote 33 appear as ordinary objects, they are living heritage objects. Charles King has connected the expression of what makes a place unique to the community relationship and explains that “what distinguishes one place from another is the deep and permanent connections between the people and communities.”Footnote 34 How then can the cultural landscape be defined? In the context of these statements, considering the fact that the people living on the water’s coast have made this place unique with their real experiences, the water heritage values in the Eastern Black Sea region will form a defining identity for the communities of the region. Heritage signifies and defines elements of identity more than the historical objects. With the inferences to be made from the complex relations between water and society, the total potential of the water heritage should be acknowledged more closely, and it will be easier to transform the achievements related to this heritage into practice.

The emergence and development of the concept of “water heritage and heritage coexistence” after 2010 can be pursued through national and international legal/administrative frameworks and documents. But, before doing so, it will be enlightening to consider the international development process leading to the definition of the concept of water landscape in order to make sense of this concept. The fact that there is a deep-rooted link between tangible cultural heritage and natural heritage and increasing threats to water have triggered experts in the field to develop new agreements/conventions. With this in mind, the Nara Conference on Authenticity, which was held by ICOMOS in November 1994, emphasized cultural diversity and heritage diversity. Landscapes were first defined as part of historic sites or designed landscapes and gardens. The idea of conserving natural areas or landscape areas that we define as ordinary has emerged in recent years. The 1975 Amsterdam Declaration was an important declaration in that it stated that architectural heritage included not only monumental structures and their surroundings but also all urban and rural areas with historical and cultural characteristics in the context of the concept of “integrated conservation.”

One of the early documents on the subject is the 1982 Florence Charter (also known as the Historical Gardens Charter), which drew attention to the need to protect the landscape areas with all their tangible and intangible elements.Footnote 35 The annexation of the definition of cultural landscape to the World Heritage Convention by UNESCO in 1992 was a turning point in the conservation of cultural landscape areas.Footnote 36 The 1995 Recommendation on the Integrated Protection of Cultural Landscape Areas is another important document in this regard.Footnote 37 This is the most well-known distinction used by UNESCO to classify cultural landscape areas. Organically developed cultural landscape areas are the areas that have lived up to their present state with the relationship they have established with the natural environment and the reactions to it, resulting from the social, economic, administrative, and theological obligations. These areas are divided into two groups as “developed” and “ongoing development.” The areas with strong theological, artistic, or cultural ties but with little or no material culture are classified as “supplementary cultural landscape areas.”

Natural landscape was accepted as a concept in the Council of Europe’s 2000 European Landscape Convention (also known as the Florence Convention), and it was extracted from being just an image, its scope was expanded, and it was associated with all areas of heritage, and, therefore, it was made to include both tangible and intangible, built and natural heritage.Footnote 38 Article 2 of the the Faro Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society, which was adopted by the Council of Europe in 2005, states that cultural heritage includes all aspects of the environment resulting from the interaction between people and places. At the same time, this convention promotes an integrated approach that takes into account cultural, biological, geological, and landscape diversity, making policies that reflect this diversity.Footnote 39 According to Graham Fairclough, the approach of the Faro Convention “created a concept of ‘new heritage’ that considered heritage more as values, especially intra-community interactions between people and their environment, and between people themselves.”Footnote 40

Fairclough, considering landscape and heritage as pillars of social sustainability, stated that it was this human-centered perspective that distinguished the Faro Convention from the previous heritage conventions.Footnote 41 Francesco Selicato, on the other hand, does not distinguish between tangible and intangible cultural heritage and has stated that the two are intertwined.Footnote 42 The 2013 Amsterdam Declaration was a call-to-text document for water, heritage, and planning professionals to share the innovative strategies on heritage conservation and water management, forge links between communities, and identify opportunities for collaboration for their mutual benefit.Footnote 43 The topic of the eighteenth General Assembly of ICOMOS, convened in Florence in 2014, was established as “heritage and landscape as human value,” and, in the published declaration, attention was drawn to the fact that cultural heritage and landscape were a part of the identities of communities. According to the declaration, landscape was the living memory of past generations and a resource through which future generations could provide tangible and intangible connections with the past. For these reasons, landscape was defined as an integral part of cultural heritage.

In the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development announced by the United Nations in September 2015, 17 Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) targets to be achieved by 2030 were identified. In these targets, it was recommended that the protection of natural and cultural heritage should be strengthened and that efforts should be augmented in the world by emphasizing the fundamental role that heritage and culture play in human development.Footnote 44 Three of the SDGs were water-related issues.Footnote 45 Even though these targets emphasize the governance and operation of water and the importance of biological diversity, the cultural heritage issue associated with water did not include water heritage. In Target 11.4 and other articles on cultural heritage, the concept of water heritage was not addressed separately. However, when Targets 6, 13, and 14 and SDG 11.4 were taken together, the concept of protecting water heritage was also explicated within the SDG. As a result, it is possible to say that the concept of water heritage is in fact compatible with all of the SDG targets and that the concept serves all objectives.

The International World Water System Heritage (WSH) program, which was initiated by the World Water Council in cooperation with the International Commission on Irrigation and Drainage in 2016, established a registry system for the intangible values of water-related heritage.Footnote 46 The WSH program aims to define and protect human-centered water management systems, organizations, regimes, and rules.Footnote 47 The 2017 Principles for Rural Landscape Heritage, prepared by ICOMOS and the International Federation of Landscape Architects, is an up-to-date text that has not changed the cultural landscape classification of UNESCO and that addresses the concept of rural landscape, the components of rural landscapes, heritage values, and threats to these values. The document states that threats to rural landscapes reflects the interrelated changes that should be examined under three headings: “demographic and cultural,” “structural,” and “environmental.”Footnote 48 When we consider the general guidelines of the works, it was emphasized that the scope of the definition of cultural landscape has expanded today; that the concept used for areas shaped by humans and nature together is associated with the environment, raw materials, basic food and water resources, and sustainability over time; that it is closely related to the protection of the right to life of future generations; and that the protection of these areas has begun to be seen as a human right.Footnote 49

National regulations on water values in Türkiye

In Türkiye, when the national framework regarding heritage and environmental protection is examined, laws such as Law no. 2863 on the Protection of Cultural and Natural Assets, Law no. 2872 on the Environment, and Law no. 2873 on National Parks come to the fore. The concepts of “cultural assets” and “natural assets” are included in Law no. 2863 on Conservation, but the integrated relationship between the two concepts was not mentioned in this law. Even though various arrangements have been made over time, the concept of cultural landscape has failed to find a place in the legal platform.Footnote 50 With Decree no. 648 in 2011, the authority for the protection of natural assets and natural sites and to take decisions on this matter were removed from the Ministry of Culture and Tourism and transferred to the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization. The Regional Commission for the Conservation of Natural Assets, established in 2011 under the ministry, was authorized to make decisions for areas overlapping with natural protected areas. The relevant commissions, on the other hand, decided to reassess all regions that were previously declared as natural sites throughout Türkiye, right after their establishment. Commissions also seem to be tended to make decisions to restrict the boundaries of these areas, which in most cases are rural settlements formed from the natural environment and components.Footnote 51

The main operational institution established in 1954 for the planning, design, construction and operation of hydraulic structures in Türkiye is the General Directorate of State Hydraulic Work (SHW-DSI). It is also the duty of the DSI to provide preventive structures against flood waters and floods.Footnote 52 Even though the right to seek and utilize natural resources is identified as one of the rights of the Turkish state in the 1982 Constitution, the state can transfer this right to real or legal persons for a certain period of time. Therefore, private companies are provided with permission to search for, and utilize, natural resources. In 2003, the construction of energy production facilities was given to the private sector by regulation within the scope of Law no. 5015 on the Electricity Market. The DSI is the main organizer of HEP plant projects that will provide applications to the private sector. In 2012, the General Directorate of Water Management and the Turkish Water Institute were established as a subsidiary to the DSI.Footnote 53 Accordingly, the authority on water management is partly the responsibility of the private sector and partly of public institutions.

In addition to international agreements mentioned in the previous section, the National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy and Action, covering the years 2011 to 2023, was developed in 2011 under the coordination of the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization. According to this action plan, the most important impacts of climate change would be monitored in relation to the water cycle and water resources. One of the natural resources that should be addressed at the global level and that cannot be renewed is “coastal areas.” The first coastal law in Türkiye was passed in 1984. The law enacted in 1990 and still in force is Law no. 3621 on Coastal Areas. Coastal areas, which are the intersection point of sea and land, have been the areas most significantly and intensively used in the world since the ancient times, in terms of economy and culture with their rich natural resources and biological diversity.Footnote 54 Coastal areas are also suitable for defense, and, therefore, most ancient civilizations were established in these areas. These areas offer many physical and biological possibilities for the sustainability of human life. Coasts are one of the areas most affected by global environmental problems such as global climate change and loss of biological diversity.

New pursuits such as “integrative coastal management,” which was adopted internationally in the 1990s and potentially expanded in other countries, have been well received by the public. However, the extent to which the “public interest” approach has been reflected in the legal regulations benefiting from the coasts has been a controversial issue. The Ministry of Forestry and Water Works of the Turkish Republic has been preparing a plan entitled Watershed Protection Action Plan, which is separately considering the water resources all over Türkiye as 25 hydrological basins. For these hydrological basins, the DSI’s General Directorate will monitor water quality.Footnote 55 Among these basins, the Eastern Black Sea Basin is the second largest basin in Türkiye. Appreciating the relationship between water and the local landscape is another way of understanding the tangible and intangible heritage of the region. Evaluating the Eastern Black Sea region in this context will encourage the establishment of a network of relations and values.

Right to landscape, minority heritage, and cultural diversity

The environmental movement, which started with the reaction to the increase in the harmful effects of man on nature, has drawn attention to the acceleration of these effects and has also pointed to the necessity of conserving the cultural and natural heritage together. Efforts toward the protection of natural resources indirectly helps preserve and strengthen traditional lands, identity, culture, and political values. It is commonly recognized that threats to the landscape have emerged in the twenty-first century due to climate change and that these threats have constantly been increasing.Footnote 56 The effects of climate change on species and human habitats through the change of environmental conditions and desertification, destructive weather events causing floods, and rising sea levels causing disasters have become an alarming issue in scientific and political international analyses and reports.Footnote 57 However, when the environment is analyzed comprehensively, it is recognized that the need to take protective measures to prevent damage to the physical environment emerged before the analyses related to climate change.

Associating social justice with landscape is not a new idea; nevertheless, the increasing threats to the landscape in the twenty-first century and their impact on the habitats of both humans and nature more generally require new tools to address such challenges. The first step toward the intellectual interface between landscape and human rights is a dynamic and layered understanding of landscape.Footnote 58 Kenneth Olwig, in his discussion of “entitlement” on the right to landscape, emphasizes the importance of the word “land” in landscape, whether it is land as “property” or a place shaped by people, according to the way in which the subject is interpreted.Footnote 59 The stories told on these subjects exemplify how the landscape is regarded not only as a place shaped by human hands but also as an element of these people’s identities. The homogeneous nation-state rhetoric was replaced by the heterogeneous multicultural state rhetoric some time ago. Even though the meaning of “heritage” in multiculturalism is unclear, the sense of plurality in meaning is prevalent. The two main purposes here are to historicize heritage and to disentangle its relation to the law. Then, the article will attempt to reveal the dual role of heritage as a commodity and a tool in governmentality in multicultural times. Both roles are legitimized by being supported by a humanist global discourse.Footnote 60

Heritage exists to testify to the passage of time, but it carries a constant historical connection. Over the past three decades, multiculturalism has brought about profound changes, especially in the organization of society, traditionally called “cultural diversity” and is based on the coexistence of different constituencies. How this situation shapes historical narratives is quite mysterious. What has become clear, after almost three decades of multicultural politics around the world, is that the multicultural joy of cultural diversity means not recognizing the value of difference but simply recognizing its organized and largely isolated existence for that reason. Real and lived inequalities have been masked by an imaginary diversity.Footnote 61 Nations combine this understanding of heritage with the idea that societies must have shared cultural beliefs to root their past beliefs and their underlying structures of power and authority.Footnote 62 The value that landscape represents in its emphasis on “identity” and “indigenousness” is similar to the theme that supports Shelley Egoz’s explanation of rootedness in the landscape.Footnote 63 In both cases, the landscape is a central motive that mutually represents collective ideologies and personal aspirations. Cultural memory is both a primary resource and a heritage generator at the same time. The right of people to have a common landscape shared by various individuals and communities, not just the landscape of the uniform area of property, is a vital issue when considering landscape.

According to archaeologist Laurajane Smith, there exists an “authoritative heritage discourse,” which generates a conceptual framework about a common set of national heritage and intrinsic values, emphasizing the earthliness and supposedly universal value of heritage.Footnote 64 Smith emphasizes that it is a set of ideas, practices, and texts about heritage that regulate the practice of professional heritage and establish how heritage is perceived and, conversely, what heritage is not.Footnote 65 Heritage is primarily based on the idea of property, both tangible and intangible. These are to be preserved in their entirety, managed, and hopefully passed on to future generations.Footnote 66 The potential power of the landscape in gaining the importance of human rights lies in its conceptualization by integrating it with tangible spatial and physical elements, resources, and intangible socioeconomic and cultural values. Therefore, landscape contextualizes the concept of human rights in universality by combining it with spatial and socio-cultural specificities. The landscape also serves as an overarching framework for local communities to negotiate the rights of the marginalized.

The French historian François Hartog thought that he had developed the concept of “le tout-patrimoine,” which meant that almost everything is part of a common heritage around the world.Footnote 67 This concept now means that the tangible, intangible, and natural heritage of others has become a part of us and that we operate within the logic of multiple, multi-valued, decentralized, and globalized heritage.Footnote 68 Most notable is the globalization of heritage discourse. In multiculturalism, it is integrally linked with globalization.Footnote 69 The word “landscape” has proven itself to be difficult to define. The studies dealing with the political dimension of the landscape have inspired anthropologists and archaeologists to go beyond the concrete and spatial dimensions and explore landscape as a “cultural repository” in a particular place and time.Footnote 70 The International Association for Landscape Ecology aims to “improve the landscape ecology as a scientific basis for the analysis, planning and management of the world’s landscapes.” The association, in this respect, represents a scientific approach to landscape.Footnote 71

It is necessary to preserve the spiritual and cultural values of the soil and local communities, as well as the landscape and nature, to preserve biological and cultural diversity, to raise awareness about landscape and nature, to support the perception and respect in this regard, and to integrate all of these elements into sustainable development. However, the right of landscape is a “right of development” that combines the existing environmental and cultural rights under one roof. On its official website, UNESCO provides the idea of an “wide-ranging standard-setting instrument to underpin its conviction that respect for cultural diversity and intercultural dialogue is one of the surest guarantees of development and peace” to the international community. In September 2002, the World Summit on Sustainable Development took place in Johannesburg, and a declaration was acknowledged recognizing cultural diversity as a collective force that should be promoted to achieve sustainable development.Footnote 72

According to Rodney Harrison, heritage could become a key area for the production of collective memory in multicultural societies.Footnote 73 In the modern world, the use of heritage and the relationship between multicultural/minority heritage and social cohesion in various societies is significant in shaping the way in which people regard themselves and their environment in order to create certain forms of memory. “Plural societies” are defined as societies that are economically interdependent, comprising more than one ethnic (and often racial) social group of people, and they refer to groups of people based on the belief in a common geographical ancestry. Many countries now contain large ethnic “minorities,” and some nations are made up of many different ethnic, racial, and cultural groups.Footnote 74 In plural societies, cultural memory is shaped by the collective memories, or, rather, collected memories, of various groups. These memories/remembrances are interconnected with the common elements of a society’s “common past” and “shared experiences.”Footnote 75

Gregory Ashworth, Brian Graham, and Jount Tunbridge have discussed the role of heritage in plural societies in their book Pluralizing Pasts: Heritage, Identity and Place in Multicultural Societies. Footnote 76 In doing so, they have developed a typology of the forms of plural societies, which could help us to understand not only the different forms that plural societies have taken but also the role of heritage in each. There are five different forms of plural society defined by the authors.Footnote 77 One of them – the salad bowl or mosaic societies – represents societies with open multicultural or pluralism policies. Possible approaches to heritage include policies that focus on delivering heritage to all members of society or specific policies that seek to recognize and empower each group in the management of its heritage, with a focus on the mutual understanding of each group’s heritage.Footnote 78

In 2002, UNESCO, following the recommendations of its world culture report entitled Cultural Diversity, Conflict and Pluralism , Footnote 79 issued its Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity.Footnote 80 The declaration states that “cultural diversity is itself part of the common heritage of humanity”:

Article 1. Cultural diversity: the common heritage of humanity.

… As a source of exchange, innovation and creativity, cultural diversity is as necessary for humankind as biodiversity is for nature. In this sense, it is the common heritage of humanity and should be recognized and affirmed for the benefit of present and future generations.Footnote 81

Further, it suggests that the promotion of cultural pluralism is a key aspect of social cohesion in plural societies:

Article 2. From cultural diversity to cultural pluralism

In our increasingly diverse societies, it is essential to ensure harmonious interaction among people and groups with plural, varied and dynamic cultural identities as well as their willingness to live together. Policies for the inclusion and participation of all citizens are guarantees of social cohesion, the vitality of civil society and peace. Thus defined, cultural pluralism gives policy expression to the reality of cultural diversity.Footnote 82

The declaration makes a clear link between cultural diversity and human rights:

Article 4. Human rights as guarantees of cultural diversity

The defence of cultural diversity is an ethical imperative, inseparable from respect for human dignity. It implies a commitment to human rights and fundamental freedoms, in particular the rights of persons belonging to minorities and those of indigenous peoples. No one may invoke cultural diversity to infringe upon human rights guaranteed by international law, nor to limit their scope.Footnote 83

In his introduction to the declaration, Koïchiro Matsuura, director-general of UNESCO, notes:

The Universal Declaration makes it clear that each individual must acknowledge not only otherness in all its forms but also the plurality of his or her own identity, within societies that are themselves plural. Only in this way can cultural diversity be preserved as an adaptive process and as a capacity for expression, creation and innovation.

The debate between those countries which would like to defend culturalgoods and services… and those which would hope to promote cultural rights has thus been surpassed, with the two approaches brought together by the Declaration, which has highlighted the causal link uniting two complementary attitudes.Footnote 84

The declaration was followed by the 2005 Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions.Footnote 85 This convention puts into practice the principles of the declaration and establishes the rights and obligations of member parties to the convention. Its objectives, among others, are to foster interculturality in order to develop cultural interaction in the spirit of building bridges among peoples; to promote respect for the diversity of cultural expressions; and to raise awareness of its value at the local, national, and international levels.Footnote 86 “Cultural diversity” in this convention refers to the manifold ways in which the cultures of groups and societies find expression. These expressions are passed on within and among groups and societies. Cultural diversity is made manifest not only through the varied ways in which the cultural heritage of humanity is expressed – augmented and transmitted through the variety of cultural expressions – but also through diverse modes of artistic creation, production, dissemination, distribution, and enjoyment, whatever the means and technologies used.Footnote 87

At the official level, the major impact on heritage throughout the 1980s and 1990s was the increase in the recognition of minority voices. The question of “whose legacy?”Footnote 88 examines who will preserve their cultural memory and who aims to reproduce their heritage.Footnote 89 In plural societies, the minority and multicultural heritage has been replaced by the concept of plural heritage over time. Since there are minorities in every society, all heritage should be regarded as a plural heritage. Saphinaz Amal Naguib has argued that heritage is shaped in the present to bridge the gap between the past and the future. Cultural memory is not frozen in time; it is built with new experiences and changing contexts and is constantly revisited and enriched. This also means that heritage is in a constant process of being shaped and reshaped.Footnote 90 In this article, the purpose of addressing multiculturalism is to emphasize that different communities both live and leave artifacts in this region and to make visible how the cultural landscape has developed through multiculturalism in the Eastern Black Sea region. The purpose of addressing the idea of multiculturalism is to emphasize the fact that different communities have both lived and left the legacy of their artifacts in this region. The main target is to make visible how the cultural landscape has developed through multiculturalism, how it has built bridges between the peoples, how it has contributed to the social cohesion, and its real integrative power in the Eastern Black Sea region.

The fact that the region is a transition area between different geographies has led to the domination of different governments and the formation of different cultures in the region. There is a rich building stock and cultural richness inherited by the various communities living in theEastern Black Sea region. In the region, which was under Byzantine rule for a long time, there are many artifacts that have survived to the present day. Civil architectural works such as bridges, mosques, churches, monasteries, administrative buildings, inns, military structures, castles, towers, and so on constitute the immovable cultural inventory of the region. Most of them are in traditional textures or integrated with nature. One of the factors that gives the region a unique quality is that the cultural and natural values are intertwined. Furthermore, the above-mentioned concepts of water heritage, water landscape, the benefits of the concepts of multiculturalism and cultural diversity, and landscape rights that developed after these concepts in conservation are explicated in the following section, together with the multicultural structure of the Eastern Black Sea Region that has developed with the water heritage and the example of how it has created a unifying force against the problems experienced.

General characteristics and water heritage in the Eastern Black Sea region

As stated in the publication “The Name of the Black Sea in Greek,” the Greeks probably used “Pontos Axeino” as their first name for the sea, which is now called the Black Sea, to mean “black” or “gloomy.” Such a name is appropriate because it is a sea where enormous waves hit the shore, storms explode, dense fog makes visibility difficult, and it is often not possible to sail. Eventually, the Greeks and Romans decided on a permanent name for the region and used the name “Pontus Euxinus,” which means hospitable.Footnote 91 Referring to Byzantine sources, the name Pontus (sea) is mostly used. In early Ottoman sources, the “Black Sea” appears with various names. In Western Europe, the Europeans used adaptive names such as Pontus and Euxine and, after the fourteenth century, the name Black Sea.Footnote 92 When we consider this naming adventure, it is possible to realize that the Black Sea has been called by different names in different civilizations.

It is stated in many source that the Greek presence emerged in the Eastern Black Sea region in the seventh century BC.Footnote 93 Throughout the history, different communities such as the Greeks and Hellenics have dominated the region. These communities were generally called Greek after the domination of the Turks.Footnote 94 From the middle of the nineteenth century, after the Ottoman-Russian war, thousands of Greeks emigrated, mainly to Russia and the Balkan countries. As a result, the Greek population in the demographic structure of the region underwent a rapid decline.Footnote 95 With the population exchange in 1923, the Greeks in the Black Sea region immigrated back to Greece. Anthony Bryer and David Winfield have stated that ancient Greek trade centers and settlements were found along the coastline, which merged with the Kaçkar Mountains and ended parallel to the Black Sea.Footnote 96 As confirmed by contemporary studies, precious metals such as copper, iron, lead, gold, and silver have been used in this region for ages, which served to increase the strategic and commercial importance of the region.Footnote 97

By the middle of the first millennium BC, the Greek trade colonies incorporated the region connecting the Black Sea coasts into the Mediterranean trade. This trade lasted until the beginning of the first millennium AD. In the following centuries, the Kefe-Trabzon-Tabriz trade route, a branch of the Silk Road, became crucial.Footnote 98 The region is situated in the geographical area where the natural and historical roads originating from the Caucasus and the Black Sea meet. It is clear that this road, which connects Eastern Anatolia and the Black Sea, has played a crucially vital role in the establishment of cultural communication and trade between the East and the West. Charles Texier enlightened us about the Trabzon port in his 1849 work Description de L’Asie Mineure. Footnote 99 Priest Minas Bzhshkian from Trabzon also described the port of Trabzon in great detail in his travel book, which he called Pontos History and completed in 1819.Footnote 100 Bzhshkian stated that Trabzon had a port before the Romans invaded and that the city had been a trade center since ancient times.

In the municipal records of 1874 and in the Trabzon population estimates for 1914, it is clear that the ethnic composition of the Trabzon Sanjak was Catholic, Armenian, Greek, Cherakis, Islam, Jewish, Catholic Armenian, and Protestant.Footnote 101 Even though Turkish is spoken in public spaces today, Laz, Mingrelian, Georgian, Greek, and Armenian are spoken at home, albeit to a lesser extent. Despite the homogeneous structure formed over the years, the difference of subcultures is also reflected in the physical structures, such as building houses.Footnote 102 In the south of the Black Sea region, the Kaçkar, Soğanlı, Zigana, Canik Mountains, and Pontus Mountain range, which are lined from east to west in the form of a mountain belt, draw a border parallel to the sea. This geography has caused the Eastern Black Sea region to have a history, climate, and geography that is more sheltered and different from the Anatolia compared to other territories of the region.Footnote 103 As you travel to the east, the mountains get steeper and impassable. However, the Eastern Black Sea region, which has a sloping and steep topography, is one of the forest-rich regions of the country. The Trabzon province in the region is one of the most important settlement and trade centers of the region (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Location of Black Sea, its surroundings, and Eastern Black Sea (reproduced from a Google Earth image by author).

The traditional settlement typology of the region is in the form of sea, river, and creek settlements. The region was shaped by the Pontics from north to south as four geographical regions: coastline, valleys, plateaus, and mountain peaks (see Figure 2). The Eastern Black SeaFootnote 104 is the region with the highest annual precipitationFootnote 105 and the most balanced distribution throughout the year. The region is also very rich in terms of water resources. The plateaus in the region have rich pastures for livestock activities. The local industry is concentrated in dry tea production facilities. The Uzungöl and Sera lakes, which are landslide lakes, are situated in this region. Most of the cities and towns are lined up along the mouths of rivers and streams that flow through the Pontic valleys and along the coastline. The valleys are home to hundreds of villages scattered irregularly on the mountain slopes, which are covered with tea or hazelnut groves at low altitudes and dense coniferous forests at higher altitudes. Intensive fishing activities are undertaken on the coastline.Footnote 106 Numerous streams and seasonal streams reach the sea by forming numerous waterfalls in deep valleys in a south-north direction. In the upper reaches of the mountains, there are many small glacial lakes and a series of small glaciers.

Figure 2. Settlement in the Eastern Black Sea topography/ a valley settlement and its section of location (reproduced from sources by author. First image source Kaptan Reference Kaptan1983, 109; second image source Sümerkan Reference Sümerkan1990, 97).

The region hosts many different habitats. Twenty-one of the endemic plant species in the region are unique to this region of the world.Footnote 107 The Çoruh Valley is an important global migration center for raptors gliding together. The rivers in the region are home to inland fish. Due to the many features that we have mentioned so far, the Eastern Black Sea region is one of Türkiye’s leading biocultural heritage sites with its natural and cultural values both historically and geographically.Footnote 108 These natural values, originating from different sources, combine with the diversity of animal species and religious structures belonging to different periods and beliefs, offer us a unique cultural landscape. In the Eastern Black Sea region, the natural environment surrounds and shapes the culture of the people. The coastal band, sandwiched between steep slopes and the sea, contains every shade of green.

When the rivers are crossed, the variety, dialect, sub-dialect, and language vary along with the color tones. This polyvocality creates a mosaic in the region. This mosaic is the harmonious combination of cultural values that have accumulated over the centuries. According to the written sources about the Black Sea region, the borders of the states established in the region were mostly located in the Eastern Black Sea region, in contrast to the borders of Türkiye today. Furthermore, according to the historical sources, the borders of Trabzon province embody many provinces in the Eastern Black Sea region today (see Figure 3). Therefore, in this study, the living water heritage values are explained in the Eastern Black Sea region without breaking the relation with the Black Sea region in general. As far as the history is concerned, many different religions, administrations, and living cultures have dominated the Eastern Black Sea region, and these cultures have directed the spatial development of the region. Throughout the time periods, water and water trade has been effective in forming and maintaining the urban and rural identity of the region.

Figure 3. The location of settlements of Black Sea over time and present boundary of the Eastern Black Sea (Image sources are given in order: (1) Arslan Reference Arslan2006, 87; (2) William Reference Shepherd1911; (3) Bryer and Winfield Reference Bryer and Winfield1985; (4 and 5) Aktüre Reference Aktüre2018, 143–74; (6) William Reference Shepherd1911, 89).

Water heritage components and values of the Eastern Black Sea region

The most important water heritage value in this region is the sea itself and rivers, streams, lakes, caves, and other components. The forest and vegetation that these components bring to life and the tangible and intangible values in the region constitute a cultural landscape. Water is regarded as both a source of life in the region and a limiting factor in rainfall and rough terrain. Local people have produced unique practical solutions for such situations. Aerial lines are one of these solutions. The settlement areas, water structures, mills, structures, and so on in the Eastern Black Sea countryside are interspersed with riverbanks, plateaus, and mountains. The mountains of the region have the largest surface area in the country as priority protection areas. Protected areas have a unique and sensitive ecosystem, but most of these areas are not protected. National parks, nature parks, natural monuments, nature protection areas, and wildlife development areas in the region are included in the official records of the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry within the scope of the study area.

There are rich and natural protected areas such as Rize İkizdere Valley, archaeological sites, urban sites, and historical sites in the region. This region is defined as “eco-geography” as it contains uninterrupted natural habitats. The region also has two important areas in Türkiye’s UNESCO World Heritage Tentative List: the Sümela Monastery (Trabzon) was registered in 2000 and the Castle and Wall Settlements situated on the Genoese Trade Route from the Mediterranean to the Black Sea were registered in 2013. In addition to these areas, the “Whistling Language,” which was registered in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List in Need of Urgent Protection in 2017, continues to exist as a unique value.Footnote 109 The Eastern Black Sea region has Türkiye’s largest rural population and the most scattered settlements. The fact that the slopes are high due to the topographic conditions has meant that mechanization in agriculture in this area is the least developed in the region. Therefore, the place of manpower in daily life has played an active role in the identity of the region’s geography.

The Rize province situated in the Eastern Black Sea region is very rich in terms of geothermal resources. There are two hot water springs on the Ayder plateau at an altitude of approximately 1,350 meters. The high landscape value created by the spruce and pine forests on the steep slopes, the rapidly flowing streams and narrow valleys, and the arch bridges over these valleys enrich the natural beauty of the area. There are also different forest communities and many mineral water sources in the region.Footnote 110 The Fırtına Valley and Basin in Rize is one of the most valuable ecosystems in the region. Traditional transhumance is maintained in these areas, and some of these plateaus are protected as national parks. The Kaçkar Peak in Kaçkar Mountains National Park is one of the highest points in Türkiye. Some of the HEP plants that are currently damaging the region are situated within the Kaçkar Mountains National Park. The Çoruh River, one of the fastest-flowing rivers in the world, on which the 1993 World Rafting Championship was held, is found in this region. Another place where rafting is performed in the region is the Fırtına Stream. Transhumance, which is one of the traditions still maintained, especially in Rize, Trabzon, and Artvin, is integrated into the use of landscape and combined with other natural heritage values of the region to form an important cultural landscape.

In addition to the water landscapes that have developed by taking their source from natural values in the region, there are also water structures such as mills, baths, bridges, aqueducts, fountains, and lighthouses, which are the architectural heritage elements made by man. Nevertheless, many of them are unusable due to their physical condition. Some of the buildings are either used sporadically or not used at all. Stone and wooden bridges were built for transportation on the streams located in the areas where the green tone is dominant, and the rural texture is developed in the Eastern Black Sea region. Some of these bridges, which have maintained their existence for centuries, have been registered. It is known that the caravans using the Silk Road used these bridges. It is possible to find information about the architecture and structure of bridges in many different texts. In these texts, it is clear that the aesthetic aspects of bridges are also discussed. Afife Batur describes the architectural and aesthetic value of stone bridges: “[S]tone bridges are a product of calculation and mastery that always has single spans, draws a low arch curve and exceeds wide stream beds with a surprisingly thin section. Especially when there is fog, which always happens, there is and there is not.”Footnote 111 He describes the wooden bridges as a light, self-suspending decoration figure that combined the tension structure and the two sides, made with skillful balancing. Batur defines these bridges as “poetic elements of the Eastern Black Sea landscape.”

The use of water mills, which was regarded as one of the most important production structures until recently, still exists in the region. These structures, which made production with traditional methods possible before the industrial revolution and whose usage in these areas gradually decreased after the revolution, are now a part of the history of technology. Elements such as water channels, water troughs, roads, and bridges, which are a part of the operation of the mills, should also be considered together with the mills. Corn flour production is still widespread in the region. Therefore, mills should continue production, and their use should be made public.Footnote 112 According to Hein, many historical water structures both catered for the water-related needs of a place and created social communities.Footnote 113 In the Eastern Black Sea region, people living in the countryside used to both swim in the streams and run the mills with the water coming from the stream. For them, the mills became a tool that were at the center of their lives and that they needed to survive. These people dried the corn they produced and turned it into cornmeal in mills. In the course of time, the dishes made using corn and corn flour have established the traditional cuisine of the Eastern Black Sea region. The elderly people of the region often talk about the memories of the mills in their conversations. In daily life, it is known that the villagers set out on the road before the sun was shining, and they reached the mills by crossing a wooden or stone bridge, where they lined up with corn sacks that they carried on their backs and had their flour milled there. Due to this intensity, the mills have served as a socializing place as well as a functional location. In order for the mill to function, first of all, the water coming from the stream to the mill must be cleared. The fact that the water in the streams is low or that the flow rate is very low causes the mills to not function today.

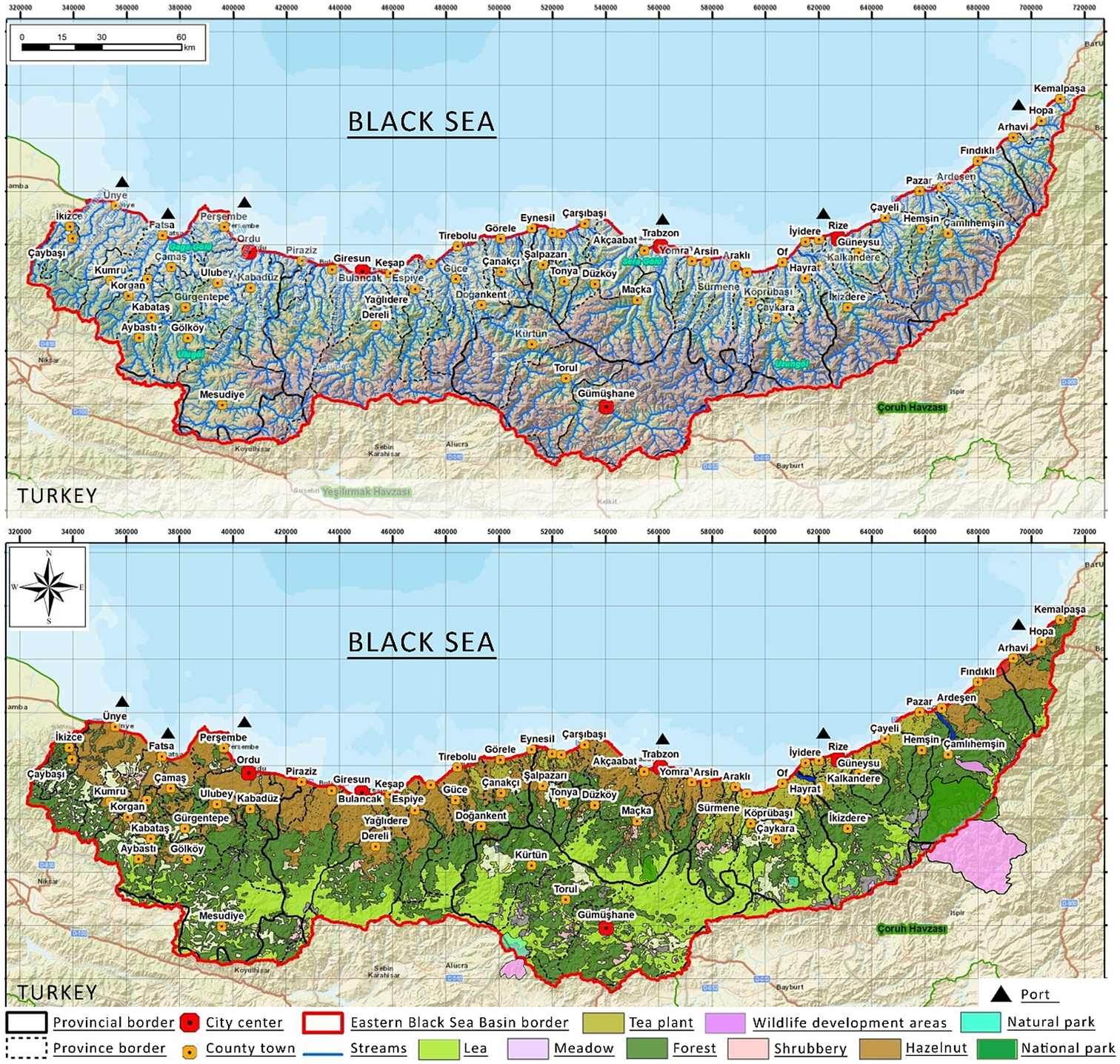

The Black Sea is one of the parts of the country that has the most sea structures (harbor, pier, fisherman’s shelter, boatyard, and so on). The lifestyle of the local people has been integrated with the sea. Fishing and maritime work are the traditional occupations of the region. There are about 100 ship paintings on the walls of the nunnery of the Hagia Sophia Church in Trabzon.Footnote 114 These were probably dedicated to the launching of a ship from Trabzon or before an important voyage.Footnote 115 Water, which has shaped many elements in daily life, has also affected the music culture of the Eastern Black Sea region. Propositions about water and water-related issues are frequently encountered in local poems and folk songs. In Table 2, the old water structures and natural water resources in the Eastern Black Sea region that have survived to the present day are arranged and evaluated according to the provinces. Rural areas are in the majority in the region, and the number of streams is quite high since the general settlement character is near the stream. Therefore, the streams are not included in the table but are shown in detail on the map in Figure 4. The values in the table have been brought together by reviewing many sources, the most recent of which is from 2019. In addition to the data here, there are also unrecorded values. Values in the list are historical and have a heritage value. We know that there are many old mills in Trabzon, but most of them are not registered. As the rate of urbanization is higher in Ordu, the rate of water structures and natural values decreases.

Table 2. Classification of the old water structures (bridge, fountain, mill, bath, holy spring, harbor, lighthouse, water well) and natural water resources (lake, waterfall, spring water, cave, river, hot spring, draw well) that have survived to the present day in the Eastern Black Sea region on the basis of the provinces of Trabzon, Artvin, Rize, Gümüşhane, Giresun, Ordu

Notes: The proper names in the table and the place names where these values are located are written as they are used in the region.

Figure 4. Map 1 of lakes, streams, and their feeding creeks in the Eastern Black Sea Basin; Map 2: protected areas map and land use map of the Eastern Black Sea Basin (reproduced from the source by author [Tarım ve Orman Bakanlığı 2020, 26, 27, 49, 68]; Esri, HERE, Garmin, USGS, Intermap, INCREMENT P, NRCan, Esri Japan, METI, Esri China, Esri Korea, Esri (Thailand), NGCC, OpenStreetMap contributors, and GIS User Community in map making).

It is clearly seen that the water heritage in the Eastern Black Sea region is quite rich in terms of natural resources. There are also a wide variety of water structures in the region. It is clear that water elements stand out in the naming of places in the region. For instance, there are many stone bridges in Rize, and districts such as Derepazarı, Güneysu, İkizdere, Iyidere, and Kalkandere are also named after water elements. The Eastern Black Sea region, with natural water resources, settlements directly related to water resources, forest cover that is still alive thanks to water, the fact that forest abundance allows the use of wood as the basic building material and that this has created the traditional architectural character of the region, water-related bridges, mill structures, and so on, the use of water in daily life and its reflection on local music, is an example of a water landscape with its intangible values. When the water heritage values are examined in terms of protection and originality, it is observed that some of the elements belonging to this heritage are still alive and continue and some of them cannot be protected. Some elements of the heritage, on the other hand, have completely disappeared (see Table 3).

Table 3. Total numbers of water structures and natural water resources in the Eastern Black Sea region

Local activism generated by the environmental movement in the region

In this day and age, people often turn to technological solutions, forgetting about the natural cycle of water. In addition to the inherent value of water, there are also the sociopolitical dynamics of water. Water now has ceased to be a source of life and has become a commodity.Footnote 116 Due to its sociopolitical dynamics, the vulnerability of water has increased in the last period, and it has become difficult to conserve. The issue of water conservation began as an environmental movement, but, with the climate crisis on the agenda, this movement has started to called attention to the impact of the crisis on heritage and cultural accumulation related to water. It is impossible to create a strong locality without a commitment to the place, and, similarly, it is not possible to carry out an effective ecological struggle without locality. Therefore, a holistic fight cannot be achieved, and the ecological movement cannot be nationalized. This particular situation necessitates establishing a holistic ecological language in order to protect the natural and local heritage.Footnote 117

David Harvey states that “space and locality have an igniting potential in the ecological fight, but this potential rarely creates a politics that can go beyond its own borders.”Footnote 118 This quote by Harvey summarizes the relationship between the local fight and the universal claim. With respect to the last twenty years of the social fight in Türkiye, it can be seen that some of these movements are anti-urban and rural transformation movements. Sinan Erensü considersresistance against HEP plants as one of the most serious sources of social opposition and one of the most important demonstrations of ecopolitical criticism in Türkiye today.Footnote 119 The harmful effects of HEP plants on living spaces have mobilized the Indigenous people of the Eastern Black Sea region for the first time against HEP plants within the framework of environmental activism.Footnote 120 When a HEP plant, stone quarry, mine, or cement factory moves into a region, it attracts other enterprises in a chain effect.Footnote 121 Participation in local activism also increases in response to the opening up of natural areas to investment across the country.

The Black Sea in Revolt Platform, which was born from the union of local peasant movements, and new city-centered environmental activists in Türkiye, including the Justice in Space Association, the Brotherhood of the Creeks Platform, the Türkiye Water Council, the Munzur Protection Board, and so on, are still active today. For instance, the “No to Mines” rally held in Artvin on 6 April 2013, was one of the most crowded demonstrations representing the environment-ecology movement in Türkiye.Footnote 122 With this movement, an environmental fight has taken place under the leadership of local components, in which people of all ages, groups, and statuses from different provinces have taken part.Footnote 123 Even though this movement gave birth to Türkiye’s biggest environmental lawsuit, a clear decision has not yet been made for the region. The rural and environmental areas that have not yet been mapped in the region have been converted into energy fields. A great deal of unrecorded value has been lost in this process. Even though the people have a right to this property, this right has not been given to the people, and the people have been dispossessed. However, it is one of the natural rights of the people to demand a share from the production.

Expanding the scope of privatization in Türkiye and commodifying streams, wind, and land – that is, nature – all of which we know to be common property, making them private property to be bought and sold,Footnote 124 has generated new problems. In other words, common values such as water and wind are being privatized, and people are being victimized. Even though renewable energy is being generated in the region to combat global warming, the tangible losses for the people are not being emphasized. The level of awareness about climate change has increased in comparison to the past. However, the principle of transparency is still being ignored in decisions taken in energy-centered and other similar project applications, and public participation is disregarded at all stages. However, the 2005 Faro Convention’s most basic emphasis is on “participation.” Sinan Erensü offers a resolution to this situation by supporting “renewable energy cooperatives.”Footnote 125 It is clearly very difficult to achieve a transition from the local scale to a national and global scale. It would be unrealistic to expect this transition from local environmental organizations. Ecological destruction and increasing injustice with respect to the environment justifies dispossession. With the legal procedure that protects the property and landscape right to be extracted, both the natural heritage and the values associated with it will be protected. As a result, local components will find the opportunity to strengthen themselves on a more acceptable ground.

Discussion and conclusion

Since the second half of the twentieth century, with the diversification of concepts related to the protection of cultural and natural heritage and the expansion of the extent of protection, discussions on the documentation, evaluation, and conservation of cultural heritage have also increased. New concepts such as the perception of monument and historical environment protection, cultural landscape, cultural diversity, and intangible values have transpired. This article has deliberated on the scope of natural heritage that should be considered in a narrow range, ignoring the intangible cultural characteristics of the natural heritage, focusing only on the conservation and recovery of the tangible components of cultural heritage and water heritage and developing suggestions that would ensure its sustainability.

There exist only a few documentation studies on water heritage in Turkey, and the documents on construction periods, typologies, and geographical distributions of water structures basically contain limited information. Not only does the inadequate number of studies on water heritage inventory restrict access to qualified information, but the unregistered water heritage elements cause the structures not to be a priority for conservation and eventually lead to their destruction. The local ecological systems, biodiversity, and geological processes also fall within the impact area of the damage to the water heritage. The increase in the vulnerability of nature makes the communities vulnerable to these natural hazards. Furthermore, the fact that natural and cultural heritage is under the responsibility of different institutions in Turkey and that there is no legal infrastructure for the conservation of rural and cultural landscape areas aggravates the holistic protection and management of water heritage and its components.

Comprehending the significance of water heritage is possible by considering the relationship and interaction of place and people with water as well as the multicultural structure of the region as a whole. It is crystal clear that all these heritage types/components of water heritage in the Eastern Black Sea region are intertwined and multicultural. The water landscape transpires with the definition of precipitated culture and history. Landscape is the living memory of past generations and a resource that future generations can harness to be able to access tangible or intangible connections with the past. This particular situation manifests itself in the Eastern Black Sea region, as described in this article. The power/drive that has generated the concept of a landscape area is the fact that it is unifying and integrative. The function of a landscape as an inclusive framework will contribute to the resolution of the cultural and environmental problems in the region. Throughout this article and in the narrative specific to the water heritage of the Eastern Black Sea region, it is clear how water is able to diversify life and how it generates multiculturalism and the ongoing interactions of this multiculturalism for many years.

The Eastern Black Sea region, with its natural water resources; settlements directly related to water resources; forest cover; the generation of its own traditional wooden architectural character, including bridges, mill fountains, Turkish baths, holy springs, harbors, lighthouses, well water structures; the use of water in daily life; and the intangible values such as its reflection in the local music, is an example of the water landscape. The diversity of the language used in the Eastern Black Sea region, the diversity of the local dialects, the diversity and abundance of the architectural artifacts generated by different cultures and the water landscape and the fact that they have transpired as a whole with the water heritage, and that many of them are still alive today, are indicators of the multicultural structure of the region. The tangible and intangible cultural values that have developed in interaction with water in daily life and the social texture of the region are inseparable parts of the whole. When the cultural and natural values of the Eastern Black Sea region are investigated with the cultural landscape approach and when its relationship with the water heritage is considered, it is clear that the region is a unique water landscape.

The power of water to be able to connect living heritage sites and its unifying power stem from the multicultural structure with which it has or is in constant interaction. When we consider the risks and areas under threat in the Eastern Black Sea region, it is essential to create a solution based on the unifying power of the water landscape values. The constructed and natural environment in the Eastern Black Sea region has been rapidly changing in recent years. Principally, the settlement areas created by filling in the stream beds and the sea have been increasing. The rivers and streams are being damaged by the effects of climate change, the direct contact of local creatures with water is being cut off by the HEP plants, highways, and so on, and it is inevitable that the cultural landscape, water landscape, and multicultural structure of the water heritage, which has been stratified over time, will also get harmed.

When local people have started to comprehend the importance of the values generated or developed by the water, the efforts to conserve the water heritage have augmented. In this sense, local activism has partially prevented and sometimes stopped the human interventions to the natural heritage in the Eastern Black Sea region and accelerated the dissemination of valid information about the events taking place in the region within the national context. In an attempt to ensure social justice in this region, the preservation of the landscape, which acts as a multi-layered interface, should be supported by law. As is also stated in this article and emphasized in Yu Sinite and colleagues, the importance and impact of heritage can go beyond the very specific context in which it has been generated and embody more universal values.Footnote 126 The multiculturalism of water heritage values and water landscape in the region transpires as a unifying force, and this becomes an urge for the holistic preservation of heritage values.