Introduction

This paper is concerned with the acquisition of a small class of deictic expressions that are of fundamental significance for reference and spatial communication: demonstratives such as English that and there. There are many different uses of demonstratives (Himmelmann, Reference Himmelmann1997); but in their basic use, they serve to focus interlocutors’ attention onto an object or location in the environment around the speech participants (Bühler, Reference Bühler1934). In this use, demonstratives are frequently accompanied by body-based means of deictic communication such as pointing and eye gaze (Stukenbrock, Reference Stukenbrock2015).

Considering the communicative functions of demonstratives, it seems reasonable to assume that demonstratives also play an important role in language acquisition (Clark, Reference Clark, Bruner and Garton1978). However, while demonstratives are often mentioned in the acquisition literature on word learning (e.g., Nelson, Reference Nelson1973), pointing (e.g., Rodrigo, González, de Vega, Muñetón-Ayala, & Rodríguet, Reference Rodrigo, González, de Vega, Muñetón-Ayala and Rodríguet2004), and children’s use of referring terms (e.g., Hughes & Allen, Reference Hughes and Allen2013), there is little systematic research on this topic. What is more, the few studies that have been specifically designed to investigate the acquisition of demonstratives are often based on sparse data (i.e., few children, small corpora) and restricted to one or two European languages (e.g., Clark & Sengul, Reference Clark and Sengul1978; González-Peña, Doherty, & Guijarro-Fuentes, Reference González-Peña, Doherty and Guijarro-Fuentes2020). The current paper examines the emergence and development of demonstratives based on extensive corpus data of several million child words from seven languages.

Demonstratives

Demonstratives are a very special class of function words that differ from all other types of closed-class expressions (Diessel, Reference Diessel2006). To begin, demonstratives are probably universal. Recent research in typology has argued that grammatical function words are language-particular (Croft, Reference Croft2001). There are, for instance, many languages that do not have articles, auxiliaries or prepositions (Evans & Levinson, Reference Evans and Levinson2009). However, demonstratives seem to exist in all languages; that is, demonstratives are likely to be universal (Diessel, Reference Diessel1999; Dixon, Reference Dixon2003). Moreover, demonstratives are very old. In the grammaticalization literature it is often argued that all grammatical function words are ultimately based on content words (Hopper & Traugott, Reference Hopper and Traugott2003); but despite intensive research, historical linguists have not been able to link the deictic roots of demonstratives to other types of expressions (Himmelmann, Reference Himmelmann1997), suggesting that demonstratives evolved early in language evolution (Diessel, Reference Diessel2013). And finally, one of the most conspicuous properties of demonstratives is their close connection to multimodal communication. As many scholars of deixis have pointed out, across languages demonstratives are frequently accompanied by pointing and other nonverbal means of deictic communication (Bühler, Reference Bühler1934; Stukenbrock, Reference Stukenbrock2015). Taken together, these properties characterize demonstratives as a unique class of expressions, distinct from both content words and other closed-class items (Diessel & Coventry, Reference Diessel and Coventry2020).

Two basic types of demonstratives are commonly distinguished: (i) nominal demonstratives functioning as pronouns or determiners (e.g., this, that), and (ii) locational demonstratives functioning as spatial adverbs or particles (e.g., here, there) (Dixon, Reference Dixon2003). The two types of expressions typically include the same deictic roots and serve similar functions and meanings (Diessel, Reference Diessel1999; Himmelmann, Reference Himmelmann1997).

The semantic interpretation of demonstratives involves a particular point of reference, which Bühler (Reference Bühler1934) called the “origo”. The origo is the center of a “coordinate system of subjective orientation” that is usually determined by the speaker’s body, gesture and location (Bühler, Reference Bühler1934, p. 202). The origo can be shifted from the speaker to some other person, or fictive observer (Stukenbrock, Reference Stukenbrock2015); but in the unmarked case, the origo is the center of an egocentric, body-oriented frame of reference (Diessel, Reference Diessel2014).

The conceptual properties of demonstratives have been at center stage in the older literature on deixis (e.g., Fillmore, Reference Fillmore, Jarvella and Klein1982), but more recent studies emphasize that demonstratives are not only used for spatial reference but also for social or interactive purposes (e.g., Stukenbrock, Reference Stukenbrock2015). In particular, these studies claim that demonstratives serve to coordinate interlocutors’ joint focus of attention (Diessel, Reference Diessel2006; Küntay & Özyürek, Reference Küntay and Özyürek2006).

Joint attention is a basic aspect of social interaction and a prerequisite for L1 acquisition that develops only gradually during the second half of the first year of life (Carpenter, Nagell, Tomasello, Butterworth, & Moore, Reference Carpenter, Nagell, Tomasello, Butterworth and Moore1998). Up to the age of about nine months, children’s interaction with the world is exclusively dyadic. Either infants focus their attention on an object and ignore other people, or they attend to an adult and disregard objects and events in the surrounding environment. It is only at the age between 9 and 12 months that infants begin to understand the triadic nature of communication and to engage in their first joint attentional behaviors (Tomasello, Reference Tomasello2003), as evidenced by the emergence of gaze following, showing and pointing in the months before their first birthday (Carpenter et al., Reference Carpenter, Nagell, Tomasello, Butterworth and Moore1998).

The emergence of joint attention marks a milestone in child development that sets the stage for word learning (Tomasello, Reference Tomasello2003). There is a large body of research on children’s early use of pointing, gaze and other nonverbal means of deictic communication; but joint attention can also be initiated by linguistic means. In particular, demonstratives are commonly used to create and to manipulate joint attention (Clark, Reference Clark1996; Diessel, Reference Diessel2006), suggesting that demonstratives might play an important role in early language acquisition. However, in contrast to the extensive literature on nonverbal means of deixis and joint attention, there is very little research on the acquisition of demonstratives and verbal deixis.

Demonstratives in Child Language Acquisition

The few studies that have been specifically designed to examine child demonstratives are mainly concerned with two topics. First, several experimental studies examined children’s comprehension of proximal and distal deixis (e.g., here ‘prox’ vs. there ‘dist’) (Charney, Reference Charney1979; Chu & Minai, Reference Chu and Minai2018; Clark & Sengul, Reference Clark and Sengul1978; de Villiers & de Villiers, Reference de Villiers and de Villiers1974; Niimura & Hayashi, Reference Niimura and Hayashi1996; Tanz, Reference Tanz1980). Using a variety of experimental tasks, these studies suggest that preschool children have difficulties understanding the contrast between proximal and distal demonstratives. For example, Clark and Sengul (Reference Clark and Sengul1978) argued, based on data from two comprehension tasks, that it takes several years for English-speaking children to master the contrast between here and there and this and that. Even if children use both proximal and distal deictics, they initially do not understand the difference between them and are biased to focus on a nearby referent (cf. Todisco, Guijarro-Fuentes, Collier, & Coventry, Reference Todisco, Guijarro-Fuentes, Collier and Coventry2021). Moreover, Clark and Sengul suggest that children learn spatial demonstratives before they understand this and that (cf. Tanz, Reference Tanz1980).

Second, several studies claim that demonstratives are among the earliest and most frequent child words (Braine, Reference Braine1976; Clark, Reference Clark, Bruner and Garton1978), but these claims are based on sparse data. For example, Clark (Reference Clark, Bruner and Garton1978) argued, based on single-case diaries and some observational data, that demonstratives are generally among the first 50 words English-speaking children use and that that and there are very frequent during the one-word stage. However, several later word-learning studies, using parental questionnaires, raised doubts about Clark’s hypotheses (Caselli, Bates, Casadio, Fenson, Sanderl, & Weir, Reference Caselli, Bates, Casadio, Fenson, Sanderl and Weir1995; Fenson, Dale, Reznick, Bates, Thal, Pethick, Tomasello, Mervis, & Stiles, Reference Fenson, Dale, Reznick, Bates, Thal, Pethick, Tomasello, Mervis and Stiles1994; González-Peña et al., Reference González-Peña, Doherty and Guijarro-Fuentes2020). In particular, González-Peña et al. (Reference González-Peña, Doherty and Guijarro-Fuentes2020) argued that demonstratives appear much later than Clark and others claimed. Analyzing several hundred parental reports of children learning English or Spanish (from the CDI Workbank), these researchers found that, while Spanish-speaking children generally produce demonstratives at 18 months, some English-speaking children do not seem to use any demonstratives before their second birthday. This is consistent with the results of a small corpus study indicating that some English-speaking children do not use demonstratives on a regular basis before age 2;0 (González-Peña et al., Reference González-Peña, Doherty and Guijarro-Fuentes2020). However, since parental questionnaires are not fully reliable when it comes to closed-class function words (Salerni, Assanelli, D’Odorico, & Rossi, Reference Salerni, Assanelli, D’Odorico and Rossi2007), and since some of the corpora González-Peña et al. used are very small (in particular some of their English corpora include just a few word tokens for individual children during their early recordings), one might question the results of this study. As it stands, it is unclear when demonstratives appear and how they develop during the preschool years. Moreover, almost all of the studies that have been specifically designed to investigate child demonstratives are restricted to a few European languages.

Overview of Studies

In this paper, we examine the acquisition of demonstratives from a broad cross-linguistic perspective based on corpus data of about eight million child words from three European and four non-European languages (English, French, Spanish, Japanese, Chinese, Hebrew, Indonesian). The paper is divided into three related studies.

In Study 1 we examine the very early uses of demonstratives between 12 to 25 months, addressing four general questions: (i) when do children begin to use demonstratives? (ii) how frequent are demonstratives in early child language? (iii) what types of demonstratives do children use? (iv) and how frequent are the various types of demonstratives in the ambient language?

In Study 2, we examine the later development of child demonstratives during the preschool years (i.e., between 20 and 70 months). We also consider the occurrence of demonstratives in adult corpora and analyze the relationship between the frequency of children’s demonstratives and their MLU.

Finally, in Study 3 we compare the development of child demonstratives to that of other spatial and referring terms (i.e., third person pronouns and spatial adpositions). The comparison is motivated by the longstanding hypothesis that children begin to construe the world from an egocentric, body-based perspective and that other strategies of conceptualizing reference and space evolve only gradually during the preschool years (e.g., Acredolo & Evans, Reference Acredolo and Evans1980; Piaget & Inhelder, Reference Piaget, Inhelder, Angdon and Lunzer1967). Since spatial deictics are interpreted within a body-oriented frame of reference (Diessel, Reference Diessel2014), we hypothesized that demonstratives are particularly frequent during the early stages of L1 acquisition and that other, non-deictic types of spatial and referring terms evolve only later when children begin to use more abstract and disembodied strategies of conceptualizing reference and space.

Study 1. Emergence of Demonstratives

The earliest words children produce typically appear around the first birthday (Clark, Reference Clark2003). In study 1, we investigate the appearance of children’s demonstratives between 12 and 25 months and also consider the use of demonstratives in the ambient language.

Data and Methods

All data come from the CHILDES database (MacWhinney, Reference MacWhinney2000), which includes corpora from more than 40 languages (https://childes.talkbank.org/). In the planning phase, we looked at the entire database, but for the vast majority of languages there are no or only very little data for the period between 12 and 25 months. For Study 1, we selected six languages: English (Germanic), French (Romance), Spanish (Romance), Hebrew (Semitic), Japanese (Japanese), and Chinese (Sinitic). All other languages were discarded for the following reasons. First, and most importantly, we had to exclude the majority of languages because the data available on CHILDES were not sufficient for the purpose of our investigation, either because the overall amount of data for one-year-olds is too small (e.g., Swedish) or because the relevant data come from only one or two children (e.g., Russian). Second, we excluded a few languages because the demonstratives of these languages are difficult to analyze. German, for example, was disregarded because the demonstratives der, die and das also serve as definite articles if they are unstressed (Himmelmann, Reference Himmelmann1997). And finally, we selected only two Romance languages (i.e., Spanish and French) and disregarded several others, for which there are sufficient data on CHILDES (i.e., Italian, Catalan, Portuguese), so as to avoid a strong sample bias towards Romance.

For the six chosen languages, we included all transcripts of children between 12 and 25 months if they fit the following criteria: we only considered transcripts of spontaneous parent-child interactions, i.e., we disregarded transcripts of non-interactive speech, and restricted the analysis to corpora that include at least 800 tokens of child words. Smaller corpora were excluded because they do not provide a reliable basis for analyzing the relative frequency of linguistic expressions and their age of appearance. In addition, we disregarded corpora of cross-sectional studies, diary studies, clinical studies, studies of bilingual children, and studies that were specifically designed for analyzing phonological properties.

Using these criteria, we created a database of more than half a million child words produced by 97 children, 43 boys and 54 girls. More than half of these data come from English-speaking children (Table 1), both British English (N=32) and American English (N=18). The data from French, Spanish and Japanese are also fairly comprehensive, both in terms of corpus size and number of children; but the Chinese and Hebrew data are relatively small.

Table 1. Number of children, age range and corpus size [Study 1]

All data were extracted by using the R package childesr (Braginsky, Sanchez, & Yurovsky, Reference Braginsky, Sanchez and Yurovsky2019). In addition to childesr, we used the corpus tools of the CHILDES project (i.e., CLAN) in order to check and analyze particular aspects of the data. Statistical analyses are based on related samples of demonstratives in the corpora of individual children and were carried out in R (R Core Team, 2021). Since the data violate the normality and homoscedasticity assumptions, we used non-parametric tests (e.g., Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test). Table 2 provides an overview of the demonstratives in the languages of our sample.

Table 2. Forms of nominal and locational demonstratives in English, French, Spanish, Japanese, Chinese, Hebrew

All six languages distinguish nominal demonstratives from locational demonstratives; but these forms usually include the same deictic roots. Nominal demonstratives are inflected for number in all languages (plural forms are not shown in Table 2) and also for gender in French, Spanish and Hebrew. Case-marking does not occur in any language. Note that English that can also be used as a conjunction or complementizer. However, as Diessel and Tomasello (Reference Diessel and Tomasello1999) showed, children do not use that as a conjunction (or complementizer) before age 3;0 and only rarely between 3;0 and 5;0 (cf. González-Peña et al., Reference González-Peña, Doherty and Guijarro-Fuentes2020).

Locational demonstratives are uninflected; but like nominal demonstratives, they comprise different distance terms. All six languages distinguish proximal deictics from distal deictics; but note that nominal demonstratives in French are only marked for distance if they are accompanied by a deictic particle, i.e., -ci ‘prox’ or -là ‘dist’. Moreover, Spanish and Japanese have three-term systems including a particular term for referents in mid distance to the origo (Spanish) or near the addressee (Japanese) (Anderson & Keenan, Reference Anderson, Keenan and Shopen1985).

In addition to nominal and locational demonstratives, some languages have a particular class of manner demonstratives that focus interlocutors’ attention onto the way an action is carried out, e.g., Spanish Así no! ‘Not like this!’ (König, Reference König2012). In accordance with previous research, the current study concentrates on nominal and locational demonstratives. Preliminary studies suggest that, while manner demonstratives are much less frequent than nominal and locational demonstratives, there is a substantial number of manner demonstratives in our Spanish and Japanese data. In all other languages, however, manner demonstratives are rare or entirely absent in early child language.

Results

Age of Appearance

All 97 children used demonstratives from the beginning of their recordings. This includes very young children at the one-word stage. The earliest recognizable words children produce appear at around the first birthday, i.e., usually between 12 and 15 months (Clark, Reference Clark2003, p. 79˗83); but then it takes several months before children begin to use multi-word utterances on a regular basis, usually around 18 months (cf. Clark, Reference Clark2003; Fenson et al., Reference Fenson, Dale, Reznick, Bates, Thal, Pethick, Tomasello, Mervis and Stiles1994; Nelson, Reference Nelson1973). Table 3 provides an overview of the appearance of demonstratives in the transcripts of our youngest children, i.e., children whose transcripts include data from the period between 12 to 17 months (N = 33). The recordings of all other children start at a later age.

Table 3. MLU, age of first demonstrative(s), and frequency of demonstrative types in the transcripts of 33 children [age 12 to 17 months]

All 33 children used demonstratives during the one-word stage (i.e., between 12 and 17 months). In fact, even twelve-month-olds and thirteen-month-olds used demonstratives from the very beginning of their recordings. Note, however, that the transcripts of five children include the first demonstratives only one or two months after their recordings started (Antoine, Clara, Pierre, Seth, Royookoon). However, since the very early transcripts of these five children contain only a few word tokens (before the first demonstratives appear one or two months later), it is not unlikely that the early transcripts of these five children do not include demonstratives simply because they do not contain enough data.

Interestingly, with few exceptions, all of the children (in Table 3) used both nominal and locational demonstratives from early on. There is no evidence in our data that locational demonstratives are learned before nominal demonstratives or vice versa. The vast majority of children use both types of demonstratives within the first five months of their recordings. Here are some typical examples.

Frequency of Use

Figure 1 shows the 16 most frequent child words in the languages of our sample. In all six languages, there are demonstratives among children’s most frequent words. In fact, in French, Japanese, Chinese, and Hebrew, the single most frequent word is a demonstrative – a locational demonstrative in French (là ‘there’) and a nominal demonstrative in Japanese (kore ‘this’), Chinese (这 ‘this’), and Hebrew (ze ‘this’). Note also that, with the exception of Chinese, there are at least three demonstratives among the 16 most frequent words in each of the six languages of our sample.

Figure 1. Sixteen most frequent words in the transcripts of 97 one-to-two-year-olds speaking English [N=50], French [N=18], Spanish [N=9], Japanese [N=9], Chinese [N=6], and Hebrew [N=5]. Dark bars indicate demonstratives.

We also looked at the overall proportions of demonstratives among the total number of child words in the transcripts of individual children. Excluding phonologically incomplete words and chunks of unrecognizable speech (which are frequent in some transcripts), we found that children produce on average about 7 to 11 demonstratives per 100 words. The largest proportion of child demonstratives occurs in French; the smallest proportion in Spanish (cf. Table 4).

Table 4. Mean proportions, standard errors, medians, and 1st and 3rd quartiles of children’s demonstratives [age 12 to 25 months]

Proportions of child demonstratives vary between 3 and 21 percent in the transcripts of individual children; but the English data include an interesting outlier, i.e., Seth (Peters corpus), whose transcripts include only 0.6 demonstratives per 100 words. There are various reasons why the proportions of demonstratives vary across children (e.g., type of interaction, corpus size), but the very small proportion of demonstratives in Seth’s data seems to have a particular reason. As it turns out, Seth has a severe visual impairment (Peters, Reference Peters1987); that is, Seth is almost blind, suggesting that he used fewer demonstratives than all other children because demonstratives are commonly used with reference to visible entities in the surrounding situation (Bühler, Reference Bühler1934).

Demonstrative Types

Next, we examined the distance features of children’s nominal and locational demonstratives. As can be seen in Figure 2, the various types of demonstratives occur with very different frequencies in the six languages of our sample. In English and French, locational demonstratives are more frequent than nominal demonstratives, but in the four other languages, it is the other way around; that is, children learning Spanish, Japanese, Chinese, and Hebrew use more nominal demonstratives than locational demonstratives. However, the numerical differences are fairly small and reach significance only in Japanese (V = 40, p < .04) and Chinese (V = 21, p < .03) (when comparing the total numbers of nominal and locational demonstratives in individual languages).

Figure 2. Mean proportions of distance terms among children’s nominal and locational demonstratives [age 12 to 25 months]. Error bars indicate standard errors.

All six languages exhibit conspicuous asymmetries between proximal and distal deictics, but these asymmetries are skewed in different directions. In English and French, children use more distal demonstratives than proximal ones (note the large proportion of distance-neutral demonstratives in French). However, in Spanish, Japanese, Chinese, and Hebrew, children use more proximal than distal deictics (Table 5). Moreover, in Japanese, proximal demonstratives are also more frequent than medial demonstratives (V = 41, p < .004), but in Spanish there is no (significant) difference between proximal and medial terms (V = 28, p < .57).

Table 5. Mean proportions of proximal and distal child demonstratives [age 12 to 25 months]

i Statistical analyses were carried out on two related samples of demonstratives (proximal vs. distal) from individual children that were submitted to a Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test.

Demonstratives in Child-Directed Speech

Finally, we examined the occurrence of demonstratives in the ambient language. Like one-year-old children, their parents make extensive use of demonstratives. However, interestingly, in all six languages our child data include a larger proportion of demonstratives than the ambient language (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Mean proportions and standard errors of children’s and parents’ demonstratives [age 12 to 25 months]

The difference is especially prominent in the domain of locational demonstratives (right panel of Table 6). The proportions of children’s and parents’ nominal demonstratives are more similar (left panel of Table 6). Only the Chinese children used a significantly larger proportion of nominal demonstratives than their caregivers (V = 21, p < .03).

Table 6. Differences in mean proportions of children’s and parents’ demonstratives [age 12 to 25 months]

Note that the parents’ distance terms exhibit the same asymmetries as those of their children (Table 7). The parents of English- and French-speaking children use more distal demonstratives than proximal ones, but in Spanish, Japanese, Chinese, and Hebrew proximal demonstratives are more frequent in the ambient language than distal demonstratives.

Table 7. Mean proportions of parents’ proximal and distal demonstratives

Discussion

Study 1 supports the hypothesis that demonstratives are among the earliest and most frequent words in L1 acquisition (Clark, Reference Clark, Bruner and Garton1978). Both nominal and locational demonstratives are early and frequent, accounting for an average of nearly 10 percent of all child words at this young age. However, there are some cross-linguistic asymmetries in children’s use of distance terms. English- and French-speaking children make extensive use of distal deictics, whereas children learning Spanish, Japanese, Chinese, and Hebrew use proximal demonstratives more frequently.

We suggest that the early and frequent use of demonstratives is grounded in the multimodal nature of early child language (Bates, Benigni, Bretherton, Camaioni, & Volterra, Reference Bates, Benigni, Bretherton, Camaioni and Volterra1979; Iverson & Goldin-Meadow, Reference Iverson and Goldin-Meadow2005). In their basic use, demonstratives involve the speaker’s body as a point of reference and are frequently accompanied by body-oriented means of deictic communication such as pointing (Stukenbrock, Reference Stukenbrock2015). Since the CHILDES transcripts do not systematically indicate nonverbal means of communication, we were not able to examine the multimodal use of demonstratives in our data. However, in order to better understand children’s early use of demonstratives, we analyzed four video recordings of one-year-old English-speaking and French-speaking children from the CHILDES archives (McCune corpus [English]: Alice, Jase; 1,2 to 1,8; N = 85 demonstratives; Lyon corpus [French]: Anais, Nathan; 1,0 to 1,8; N = 591 demonstratives). While these data are not sufficient to draw any firm conclusions, they are consistent with our hypothesis. All child demonstratives (that occur in the four videos) refer to objects or events in the surrounding speech situation and generally involve the child’s body and/or gesture. Some early demonstratives are accompanied by pointing, but more frequently, we found that children use demonstratives while grasping, holding, showing or offering an object to an adult speaker. Of course, more research is needed to examine the proposed connection between multimodal communication and the early and frequent use of demonstratives in L1 acquisition.

The distance features of demonstratives have been investigated in several experimental studies indicating that children as old as three years of age do not (fully) understand the contrast between proximal and distal deictics (e.g., Clark & Sengul, Reference Clark and Sengul1978). However, our data show that even one-year-olds use both types of deixis from early on, though with different frequencies in different languages. Clark and Sengul (Reference Clark and Sengul1978) argued that the distance features of demonstratives are irrelevant to children’s use of deixis during the early stages of L1 acquisition. On this account, both proximal and distal demonstratives are initially used as general pointing words that focus interlocutors’ attention onto a referent without indicating a contrast in distance (cf. Charney, Reference Charney1979). Assuming that children’s early demonstratives are non-contrastive, we submit that the relative frequency of proximal and distal demonstratives in early child language is not semantically motivated but determined by their distribution in the ambient language, which in turn reflects their frequency in adult language use. As we have seen, the proportions of children’s distance terms correspond closely to those in child-directed speech (and adult language use), suggesting that children’s language-specific predilections for proximal, distal or neutral demonstratives are due to their experience with these expressions in the ambient language. What is more difficult to explain are the language-specific differences of proximal and distal deictics in adult language use (including the ambient language). A possible explanation has been proposed by Levinson (Reference Levinson, Levinson, Cutfield, Dunn, Enfield and Meira2018), who argued that (many) deictic systems include a default demonstrative speakers use in non-contrastive situations. In some languages, the default demonstrative is an unmarked term that does not encode distance (e.g., French); but very often either the proximal or the distal term serves as the default in non-contrastive contexts. Since demonstratives are often used in non-contrastive situations, the default term is more frequent than all other demonstratives in the system (as the latter are mainly used in contrastive situations).

Study 2. Development of Demonstratives during Preschool Years

In Study 2 we extended the analysis of children’s demonstratives to later years, considering the age between 1;8 and 6;0. It is the goal of this study to investigate how demonstratives develop during the preschool years.

Data and Methods

Study 2 draws on the entire data available on CHILDES for the languages of our sample, except for data from bilingual and clinical studies, which have been disregarded. All data were extracted by using childesr and preprocessed by an R-script that automatically calculates some basic statistics (i.e., mean proportions, standard deviations).

Five of the six languages of Study 1 were also included in Study 2, i.e., English, French, Spanish, Japanese, and Hebrew; but Chinese was replaced by Indonesian, as the CHILDES data of Chinese include too many gaps during the preschool years. The Indonesian data, by contrast, are sparse for the early age of Study 1 but dense for older ages.

Indonesian has two nominal demonstratives, i.e., ini ‘this’ and itu ‘that’ (allomorphs: ni, nih, tu, tuh), and three locational demonstratives, i.e., sini ‘here’, situ ‘there’, sane ‘there (far away)’. Both nominal and locational demonstratives are uninflected; number is expressed by independent plural words, and gender and case are not encoded by demonstratives in Indonesian (Himmelmann, Reference Himmelmann1997). Table 8 provides a general overview of our data.

Table 8. Number of children, age range, corpus size, and total number of child demonstratives [Study 2]

Overall, the database of Study 2 comprises more than 7.5 million child words with nearly half a million demonstratives. The largest amount of data comes from English, followed by Japanese, French, Indonesian, Spanish, and Hebrew. Note that the Indonesian data are based on comprehensive corpora from only 8 children.

Results

Considering the entire dataset, children produced an average of 6.6 demonstratives per 100 words. However, the occurrence of demonstratives is unevenly distributed across both languages and age. The largest proportion of demonstratives occurs in Indonesian (9.4%), followed by French (8.8%), Hebrew (7.3%), Spanish (6.8%), Japanese (6.1%), and English (5.8%). Moreover, and this is of particular importance, the frequency of child demonstratives varies with age. As can be seen in Figure 4, across languages, the proportions of demonstratives decrease as children grow older. The relationship is highly significant in all six languages, with the highest coefficients of determination in French (r2 = 0.82, p < .001) and Japanese (r2 = 0.80, p < .001), followed by English (r2 = 0.62, p < .001), Hebrew (r2 = 0.49, p < .001), Indonesian (r2 = 0.45, p < .001), and Spanish (r2 = 0.29, p < .001).

Figure 4. Correlation between age and demonstrative frequency

Nominal and locational demonstratives develop in parallel ways across languages. In five of the six languages (English, French, Spanish, Japanese, Hebrew), both types of demonstratives decrease in frequency with age at similar rates (Table 9). In Indonesian, nominal demonstratives are also decreasing, but locational demonstratives become more frequent as children grow older. However, since locational demonstratives are relatively rare in Indonesian, accounting for only 11.5 percent of all child demonstratives, the overall proportion of demonstratives is also decreasing in Indonesian, as in all other languages (Figure 4).

Table 9. Regression coefficients of age as a predictor of child demonstrative frequency [age 20 to 72 months]

i Asterisks indicate level of significance: *** = .0001, ** = .001

For English, we also examined the relationship between demonstratives and MLU. To this end, we selected a subset of 46 children with large datasets covering at least six months (per child). For all 46 children, we calculated the percentage of demonstratives among their total words at a particular month and mapped this score onto their MLU score at this age (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Correlation between MLU and percentage of demonstratives per 100 child words in English [age 20 to 72 months]

As can be seen, the correlation between MLU and demonstrative ratio is highly variable, but there is a clear and statistically significant trend: the higher a child’s MLU, the lower the percentage of demonstratives (r2 = 0.18, p < 0.001, coefficient = -0.974, intercept = 9.72). Since the data are not consistent with the homoscedasticity assumption of linear regression, we also used a bootstrap approach (5000 samples) to calculate confidence intervals for the predictor variable. The CIs (which were calculated by using the R package boot) indicate that the results are reliable (cf. MLU: 95% CIs: -1.1254, -0.8311; r2: 95% CIs: 0.1366, 0.2288).

Finally, we compared the proportions of demonstratives in our child data to those of adult language use, considering both spoken and written registers. To this end, we collected adult data from large electronic corpora for all languages of our study, including Chinese. The adult corpora are freely available on the internet (sources are indicated in Table 14 in the appendix). Figure 6 presents a summary of these data.

Figure 6. Proportions of demonstratives in child language (at two different ages) and adult language (in spoken and written registers)

Across languages, child corpora include a much larger proportion of demonstratives than adult corpora. In particular, the early child data (age 2;0 to 3;0) include a very large proportion of demonstratives, ranging from 6.4 percent in English to 11.5 percent in Indonesian; whereas demonstratives in written adult language are particularly infrequent (around 1 percent or less in all seven languages). The proportions are strikingly similar across languages.

Discussion

Study 2 shows that demonstratives are especially frequent in early child language and that the overall proportions of child demonstratives decrease with age (and MLU in English). Across languages, four-year-olds use fewer demonstratives than children aged 2;0 to 3;0. What is more, the waning use of demonstratives seems to continue beyond the preschool years. Adult corpora include fewer demonstratives than child corpora, with the smallest proportions of demonstratives in adult written registers.

Since demonstratives usually involve the speaker’s body and gesture, they are especially useful for children at the very early stages of L1 acquisition. According to theories of situated embodiment, children begin to construe the world from a body-oriented perspective; but when they grow older, they also learn other strategies for reference and space that do not immediately rely on the speaker’s body and location (Pexman, Reference Pexman2017, for a review). Considering these theories, it seems plausible to assume that the decreasing frequency of demonstratives during the preschool years is related to the child’s developing capacity to use other, disembodied concepts for reference and space that supplement and replace (in part) the use of demonstratives as spatial and referring terms.

Study 3. Development of Non-Deictic Spatial and Referring Terms

In order to test if the decreasing frequency of demonstratives correlates with the increasing use of other types of spatial and referring terms, we examined two types of expressions: spatial adpositions and third person pronouns.

The acquisition of third person pronouns has been studied intensively in generative linguistics (e.g., Hyams et al., Reference Hyams, Mateu, Orfitelli, Putnam, Rothman, Sanchez, Fabregas, Mateu and Putnam2015). Most of this research is concerned with the issue of null arguments, which might pose a limitation to our study as the mechanisms of acquiring null arguments are orthogonal to those of situated embodiment that motivate our hypothesis about the development of third person pronouns (see our discussion below). Like demonstratives, third person pronouns are referring terms, but are mainly used as anaphors rather than as deictics. There is an ongoing debate about the relationship between deixis and anaphor in the linguistic literature (Ehlich, Reference Ehlich, Jarvella and Klein1982; Talmy, Reference Talmy2018). In a recent monograph, Talmy (Reference Talmy2018) argued that deixis and anaphor involve the same cognitive system (cf. Bühler, Reference Bühler1934). Yet, while there are conspicuous parallels between deixis and anaphor, most researchers agree that anaphoric reference does not involve the speaker’s body and gesture; instead, the realm of anaphor is the universe of discourse.

The acquisition of spatial adpositions has played a prominent role in research on language and space (e.g., Bowerman & Choi, Reference Bowerman, Choi, Gentner and Goldin-Meadow2003); but this research does not immediately concern our hypothesis about the relationship between deictic and non-deictic types of expressions in L1 acquisition. Like demonstratives, adpositions are commonly used to encode space, but spatial adpositions are usually non-deictic. In their basic use, spatial adpositions indicate a relationship between a figure concept and a conceptual ground (Talmy, Reference Talmy2000). However, crucially, although demonstratives and adpositions construe space in different ways, there is an area of overlap where speakers can choose between them to describe the same scene (e.g., Put the book on the table → Put the book [over] there), suggesting that demonstratives and spatial adpositions may influence each other in the course of L1 acquisition.

Assuming that children’s use of spatial and referring terms becomes increasingly more independent of the child’s body and gesture, we hypothesized that third person pronouns and spatial adpositions become more frequent, as demonstratives decrease in frequency during the preschool years.

Data and Methods

Study 3 uses the same corpora and methods as studies 1 and 2. Table 10 shows the morphological forms of third person pronouns in the languages of our sample. Since some of the French and Spanish (object) pronouns are mainly used as articles, they are disregarded (i.e., those in square brackets). Note that some of the languages in our sample make common use of null arguments (Valian, Reference Valian, Lidz, Snyder and Pater2016). In Japanese, for example, pronouns are frequently omitted. There is also a strong tendency for using null arguments in Spanish, Chinese and Indonesian; but in English, French and Hebrew, argument pronouns are usually present in adult language (Valian, Reference Valian, Lidz, Snyder and Pater2016).

Table 10. Third person pronouns in English, French, Spanish, Japanese, Hebrew, Chinese, Indonesian

Table 11 provides an overview of spatial adpositions in five of the six languages of our sample. Hebrew is excluded because Hebrew makes extensive use of verbal affixes and prepositional pronouns in contexts in which other languages use spatial adpositions (Dromi, Reference Dromi1979). Note also that many spatial adpositions are polysemous (e.g., in the room [space] vs. in an hour [time]). Polysemy is a very common phenomenon of adpositions in languages across the world (Talmy, Reference Talmy2000). For the purpose of this study, we concentrated on adpositions that are predominantly spatial. Adpositions that are primarily used in non-spatial domains have been disregarded even if they have (less frequent) spatial uses (such as French de ‘from’ and Spanish a ‘to’, which are primarily used as case markers).

Table 11. Spatial adpositions in English, French, Spanish, Japanese, Chinese, Indonesian

Results

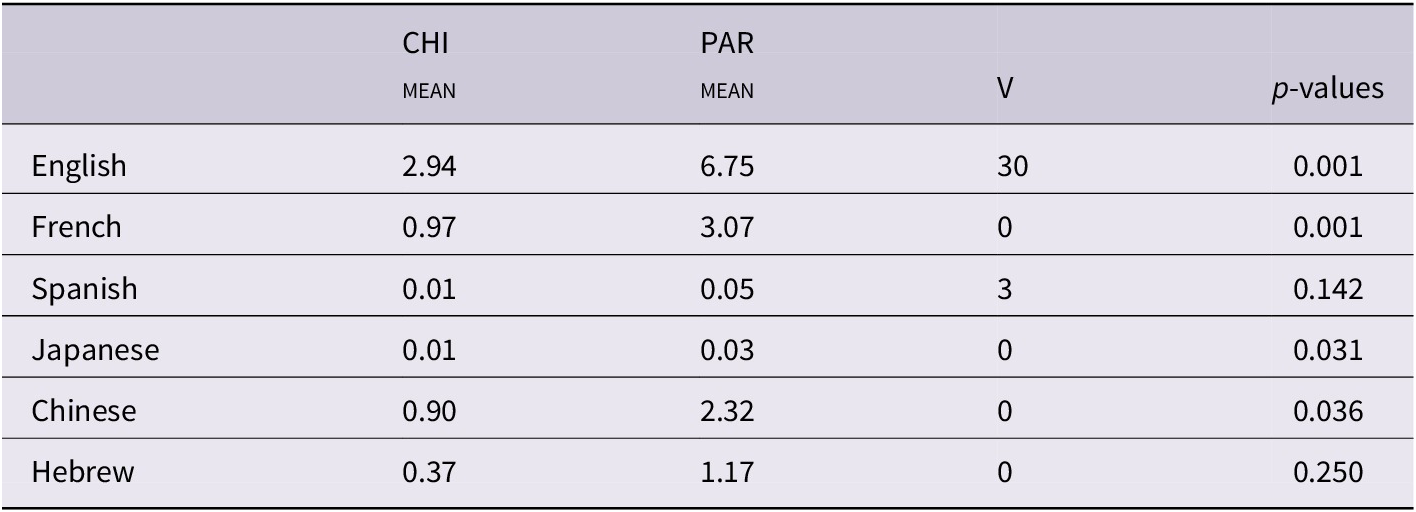

Third Person Pronouns

Compared to demonstratives, third person pronouns are infrequent during the early stage of L1 acquisition (i.e., between 12 and 25 months). In particular, in languages with frequent null arguments, third person pronouns are rare, accounting for only 0.01 percent of the total number of child words in Spanish and Japanese (Table 12). Only the English data include a substantial number of third person pronouns at this young age (2.94%); but note that about 90 percent of the English third person pronouns are due to the neuter singular form it, which is often used (similar to a demonstrative) with text-external reference (Strauss, Reference Strauss2002) and/or as an expletive (Valian, Reference Valian1991). Note also that in all six languages, children use fewer third person pronouns than their parents.

Table 12. Mean proportions of children’s and parents’ third person pronouns [age 12-25 months]

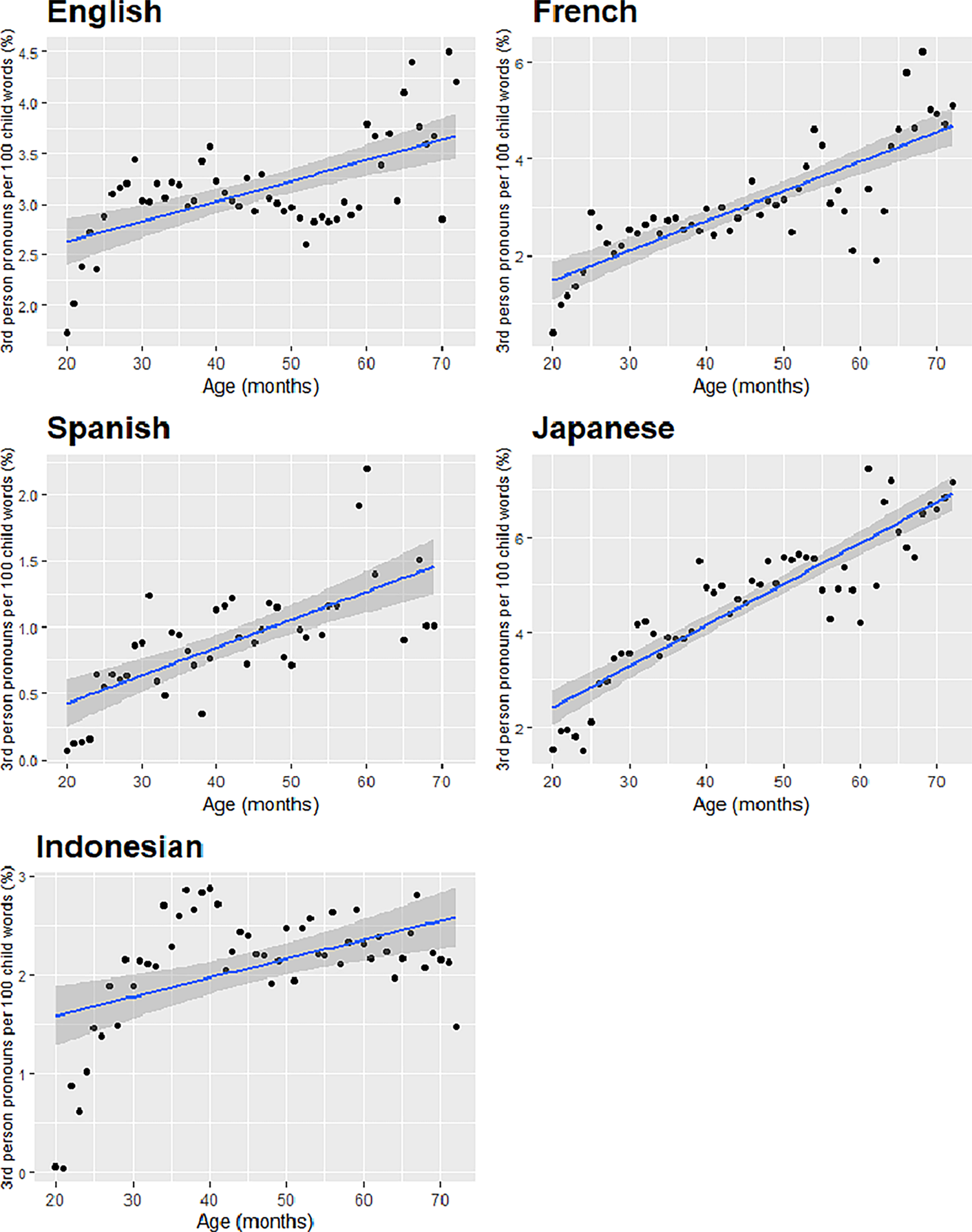

As children grow older, third person pronouns increase in frequency (Figure 7). The increase is highly significant in English (r2 = 0.63, p < .001), French (r2 = 0.52, p < .001), Japanese (r2 = 0.35, p < .001), Indonesian (r2 = 0.40, p < .001), and Hebrew (r2 = 0.49, p < .001) but does not reach significance in Spanish (r2 = 0.02, p = .314), where third person pronouns remain rare throughout the preschool years.

Figure 7. Correlation between age and frequency of third person pronouns

Spatial Adpositions

Like third person pronouns, spatial adpositions are much less frequent than demonstratives during the early stages of L1 acquisition (Table 13). Only the English data include a substantial number of spatial adpositions between 12 and 25 months (2.7%); but note that, even in English, children’s spatial adpositions are much less frequent than demonstratives. Moreover, in all six languages, spatial adpositions are significantly less frequent in child language than in child-directed speech (Table 13).

Table 13. Mean proportions of children’s and parents’ spatial adpositions [age 12-25 months]

As children grow older, spatial adpositions increase in frequency (Figure 8). There is a steady increase across the entire age range in French (r2 = 0. 65, p < .001), Spanish (r2 = 0. 48, p < .001), and Japanese (r2 = 0. 80, p < .001). Adpositions also increase in frequency in English (r2 = 0.37, p < .001) and Indonesian (r2 = 0.23, p < .001), but in these languages the increase occurs primarily between 20 and 35 months.

Figure 8. Correlation between age and frequency of spatial adpositions

Discussion

The results of Study 3 are consistent with our hypothesis that the decreasing frequency of demonstratives in child development is accompanied by an increasing use of other spatial and referring terms. Both third person pronouns and spatial adpositions are relatively rare at the beginning of L1 acquisition but increase in frequency as children grow older. One reason for this may be that grammatical function words are frequently omitted in early L1 acquisition. It has long been recognized that young children tend to leave out certain function morphemes (Brown, Reference Brown1973). There are various proposals in the literature to explain the omission of function words, e.g., lack of prosodic prominence (Gerken, Reference Gerken1991) or processing pressure to reduce syntactic complexity (Pinker, Reference Pinker1984). However, the omission of pronouns has been subject to a particular debate that concerns the acquisition of null arguments (Hyams et al., Reference Hyams, Mateu, Orfitelli, Putnam, Rothman, Sanchez, Fabregas, Mateu and Putnam2015).

In our study, we did not specifically investigate the occurrence of null arguments, but in accordance with much previous research we found that there are substantial cross-linguistic differences in the overall frequency of third person pronouns. For example, our English data include many more third person pronouns than our Spanish and Japanese data. There are two main approaches to explain cross-linguistic differences in argument omission and the acquisition of null arguments.

In the generative approach, languages are divided into distinct types based on argument omission parameters (see Hyams et al., Reference Hyams, Mateu, Orfitelli, Putnam, Rothman, Sanchez, Fabregas, Mateu and Putnam2015, for a review). Spanish, for example, is a null-subject language in which subject arguments are frequently omitted in certain contexts; Chinese is a null-subject and null-object language in which both types of arguments are omittable; and English is a non-null-argument language in which arguments are obligatory in most contexts. On this account, cross-linguistic differences in the acquisition of pronouns are mainly explained by prespecified argument omission parameters of the language faculty that are set to particular values by specific triggers in the input (e.g., Chomsky, Reference Chomsky1981; Rizzi, Reference Rizzi1986; Yang, Reference Yang2002). Since parameter setting is not usually related to aspects of situated embodiment, parameter theory poses a limitation to our study that may undermine our claim that the developments of demonstratives and third person pronouns are related (by the changing role of the child’s body in the course of L1 acquisition). More detailed studies are needed to examine if our hypothesis is compatible with parameter theory.

An alternative to parameter theory is the usage-based approach (Tomasello, Reference Tomasello2003), which is closely related to functional research in linguistic typology (e.g., Bybee, Reference Bybee2010; Croft, Reference Croft2001; see also Diessel, Reference Diessel2019). In this approach, researchers do not distinguish between prespecified language types (Evans & Levinson, Reference Evans and Levinson2009) but argue that all aspects of linguistic structure are emergent from domain-general processes of using language in concrete situations. Rather than distinguishing between null-argument and non-null-argument languages, usage-based linguists analyze cross-linguistic differences in the occurrence of pronouns (and other referring terms) as a continuum that reflects language-specific conventions on argument realization that have emerged, historically, from general cognitive processes of language use (Ariel, Reference Ariel2014). Few usage-based studies have directly addressed the question of how null arguments are acquired in this approach (but see Valian, Reference Valian, Lidz, Snyder and Pater2016, for relevant research); but researchers generally emphasize that the acquisition of linguistic expressions is crucially influenced by their frequency in the ambient language (e.g., Behrens, Reference Behrens2021; Tomasello, Reference Tomasello2003), predicting that cross-linguistic differences in the occurrence of third person pronouns in child-directed speech give rise to cross-linguistic differences in the frequency of third person pronouns in child language (Ambridge, Kidd, Rowland, & Theakston, Reference Ambridge, Kidd, Rowland and Theakston2015).Footnote 1

Both theories can account for the cross-linguistic differences in frequency of third person pronouns; but, in the usage-based approach, parameter setting is not a confound for our study as the acquisition of grammar is entirely explained by domain-general processes that are sensitive to frequency of use (cf. Diessel, Reference Diessel2019, p. 23˗39).

Crucially, while children’s proportions of third person pronouns vary across languages, there are conspicuous cross-linguistic parallels in their development that are consistent with our hypothesis that the acquisition of third person pronouns is influenced by the changing role of the child’s body in L1 acquisition. Across all languages, one-year-old children use third person pronouns much less frequently than demonstratives, and less frequently than their parents; however, as children grow older, third person pronouns increase in frequency, whereas demonstratives become less frequent, which may be seen as a sign that children’s use of referring expressions becomes increasingly less dependent on their body.

The development of children’s spatial adpositions is strikingly similar to that of third person pronouns. One-year-old children use spatial adpositions less frequently than demonstratives, and the proportions of children’s spatial adpositions are smaller than those of their parents in all languages. However, with growing age, children use fewer demonstratives and more spatial adpositions, arguably for the same reason as they use more third person pronouns.

Taken together, these findings are consistent with our hypothesis that the various spatial and referring terms influence each other in the course of L1 acquisition. More specifically, we claim that the increasing frequency of third person pronouns and spatial adpositions reflects the child’s evolving capacity to encode reference and space from an allocentric perspective, making it possible to use a wider variety of spatial and referring expressions that supplement and replace, in part, the body-oriented use of demonstratives that is so prominent in early child language. Of course, a large-scale, cross-linguistic study of this kind has many confounds. The whole issue needs to be investigated in more detail and in more fine-grained studies.

General Discussion

In this paper, we have used an extensive database of several million child words from seven languages to investigate the appearance and development of demonstratives during the preschool years. In three related studies, we have addressed the following questions.

When do children begin to use demonstratives? Study 1 provides good evidence for the hypothesis that demonstratives are among the earliest child words (Clark, Reference Clark, Bruner and Garton1978). Several studies using parental reports raised doubts about this hypothesis, arguing that many children do not use demonstratives before age 20 to 24 months (Caselli et al., Reference Caselli, Bates, Casadio, Fenson, Sanderl and Weir1995; Fenson et al., Reference Fenson, Dale, Reznick, Bates, Thal, Pethick, Tomasello, Mervis and Stiles1994; González-Peña et al., Reference González-Peña, Doherty and Guijarro-Fuentes2020). However, this is not consistent with our findings, which show that, across languages, demonstratives appear very early during the one-word stage (i.e., 12 to 17 months). Parental reports are useful for analyzing the appearance of content words, but as Salerni et al. (Reference Salerni, Assanelli, D’Odorico and Rossi2007) showed, they are not fully reliable for analyzing children’s function words (e.g., demonstratives).

How frequent are demonstratives in early child language? Study 1 shows that demonstratives are very frequent in early L1 acquisition. They account for about 7 to 11 percent of the total number of child words between 1;0 and 2;0 and are often the single most frequent word type individual children use at this young age. Apart from demonstratives, children make extensive use of negative and affirmative particles (e.g., yes, no), interjections (e.g., oh, ah), and a few grammatical function words (e.g., the, a); but with the exception of the word for ‘mummy’, there are hardly any content words among the most frequent expressions one-year-old children use, suggesting that demonstratives are the preferred means of linguistic reference at this young age.

What types of demonstratives do children use? Some studies suggest that locational demonstratives appear before nominal demonstratives; but this is not supported by our data. Both nominal and locational demonstratives are frequent in early child language. However, there are some conspicuous cross-linguistic asymmetries in children’s use of distance terms: English- and French-speaking children make extensive use of distal demonstratives, whereas children learning Spanish, Japanese, Chinese, and Hebrew mainly use proximal demonstratives, indicating that there is no universal (cognitive) predilection for a particular distance term.

How frequent are demonstratives in the ambient language? Like children, parents make extensive use of demonstratives (when they talk to young children) and their proportions of distance terms are skewed in the same direction. The parents of English- and French-speaking children use more distal than proximal demonstratives, whereas the parents of Spanish-, Hebrew-, Japanese-, and Chinese-speaking children use more proximal deictics. However, while the ambient language is likely to affect children’s use of particular distance terms, it is interesting to note that children tend to use more demonstratives than their parents, suggesting that demonstratives are particularly useful for young children.

How do demonstratives develop with age and MLU? Study 2 shows that the proportions of demonstratives decrease with age (and MLU in English). In all six languages, one-year-olds use demonstratives more frequently than four-to-five-year-olds, which in turn use demonstratives more often than adult speakers. In particular, written adult language includes a much smaller proportion of demonstratives than child language.

Finally, we asked: does the development of demonstratives correlate with that of other spatial and referring terms? While demonstratives decrease in frequency, our data show that non-deictic spatial and referring terms become more frequent with age. In Study 3 we saw that both third person pronouns and spatial adpositions are rare in the speech of one-year-olds but increase in frequency as children grow older.

Child language researchers have often noted that children tend to omit grammatical function words (Brown, Reference Brown1973). However, although demonstratives are commonly regarded as function words, there is no evidence that children omit them. On the contrary, our data show that demonstratives are extremely frequent during the early stages of L1 acquisition.

One factor that distinguishes demonstratives from most other function words is that demonstratives are often stressed (Himmelmann, Reference Himmelmann1997). However, while prosodic properties may have some influence on children’s use of function words (Gerken, Reference Gerken1991), they do not explain why demonstratives are so frequent in early child language, why one-year-olds use demonstratives more frequently than their parents, and why demonstratives decrease in frequency with age whereas third person pronouns and spatial adpositions become more frequent.

The opposite developments of demonstratives and other spatial and referring terms are congruent with our hypothesis that these expressions influence each other in L1 acquisition. More specifically, we argue that the opposite developments of demonstratives and other spatial and referring terms reflect the changing role of the child’s body in language acquisition. Building on Piaget, child language researchers have often argued that young children tend to construe the world from an egocentric, body-oriented perspective (Piaget & Inhelder, Reference Piaget, Inhelder, Angdon and Lunzer1967). Considering this hypothesis, we suggest that one-year-old children make extensive use of demonstratives because the deictic use of demonstratives involves the speaker’s body and gesture. In theories of situated embodiment, the earliest concepts of child development are shaped by children’s experiences with their own body and action (Pexman, Reference Pexman2017, for a review). Yet with age, children learn other, more abstract concepts and expressions for objects and space that are semantically and/or functionally related to demonstratives but do not (directly) involve the speaker’s body (Borghi, Flumini, Cimatti, Marocco, & Scorolli, Reference Borghi, Flumini, Cimatti, Marocco and Scorolli2011; Lakoff, Reference Lakoff2012).

In accordance with these theories, we suggest that children shift from using a body-oriented strategy of deictic communication at the onset of L1 acquisition to more abstract and disembodied strategies of encoding reference and space during the preschool years. However, more research is needed to investigate the proposed connection between the development of demonstratives and the rise of other disembodied strategies for expressing reference and space.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Appendix

Table 14. Online corpora used to determine the proportions of demonstratives in adult language, spoken and written registers [summarized in Figure 6]