It is for a certain reason that we start the book on research approaches in business ethics with the chapter on the use of historical figures. While business ethics may be regarded by many as a relatively new field of inquiry, the roots of contemporary thinking go well into the seventeenth century.Footnote 1 It is the great thinkers of the past who laid down the foundation for economic thoughts while all along speculating on the role of ethics in business; and it is the moral philosophers of the past whose ideas continue to be quite relevant for today’s business practices. Indeed, the awareness of the invaluable heritage left for us by historical figures opens a horizon for multiple research possibilities in business ethics, and provides a specific framework, a research approach, for the business ethics scholarship. As an illustration of this research approach, this chapter attempts to cover the relevant works of John Locke, Adam Smith, Karl Marx, and John Dewey, though of course there are many other historical figures who could serve well for research projects in business ethics. Business ethics scholars of today regularly take to this methodological framework both to develop new full-scale theories and to analyze an array of pertinent business ethics concepts and phenomena. Thus, philosophical teachings of the past continue to inform the present-day scholarship of the field.

The use of historical figures as a research approach is typically not included in books on social research methodology. The inspection of about a dozen books on qualitative research methods in social sciences (Barbour, Reference Barbour2008; Roth, Reference Roth2005; Ritchie & Lewis, Reference Ritchie and Lewis2003; May, Reference May2002; Bernard, Reference Bernard2000; Silverman, Reference Silverman1997; Sarantakos, Reference Sarantakos1994) revealed that none of them described the methodological approach to research that we are going to cover in this chapter. Some social research books briefly touch upon the work with historical documentary data (Punch, Reference Punch1998), culturally or historically significant phenomena (Ragin, Reference Ragin1994), or they briefly talk about historical-comparative methods (Luker, Reference Luker2008). However, all these methodologies are different from the use of historical figures as a research approach whose variations might sometimes be included in business ethics textbooks (e.g., Donaldson & Werhane, Reference Donaldson and Werhane2008).

The use of historical figures method may share certain tools and logic building with other methodologies, nevertheless we see this way of doing research as a standalone approach with its unique research framework. The word “historical” in the research approach of using historical figures may suggest that it is a part of a historical field of research. However, this is misleading as the research method of using historical figures does not reside in the historical research domain. History looks at particular events in the past, and historical methodology focuses on the collection of evidence and on the communication of evidence (Shafer, Reference Shafer1980; Subrahmanian, Reference Subrahmanian1980), and the goal of history is to present a body of established facts to understand what happened and why (Krentz, Reference Krentz2002). Differently from it, the research approach of using historical figures focuses more on influential, far-reaching ideas of great thinkers, though of course placed in a historical perspective, and the relevance of those ideas to the contemporary development of the field. As Luker (Reference Luker2008: 191) put it, “if you just wanted to tell a story, that is, craft a narrative of what happened, you would have found yourself more drawn to history.” Differently from historians, business ethicists who use historical figures in their research write not stories per se, but try to build theories and narratives that are applicable to the present-day business world.

It is in its attempt to generate theories that this historical figures approach is similar to historical-comparative methods used in social sciences. However, what makes this approach different from the set of historical-comparative methods is that the latter aim to attend to the two main questions – “either (a) what events in the past shaped how this turned out in the present? or (b) why did things turn out this way in one place and another way in another place?” (Luker, Reference Luker2008: 191) – and try to find the causation effects to create explanations why particular things may also happen in other places and times. We are not arguing that doing real history is not important in business ethics. In fact, understanding the causes and effects of historical events in business is central to building narratives. For instance, the investigation into the Panic of 1837 and the consequent long-lasting economic recession in the United States can apply when analyzing the global financial crisis of 2007–2009. On the one hand, a research approach of using historical figures in business ethics may draw on particular events in the past and analyze the elements of causation; on the other hand, this research framework also goes beyond explaining the causal links between ethics and business, and often centers around normative aspects of business ethics by grounding itself in the logic of argumentation.

Logical argumentation in developing one’s points of view and the room for encompassing normative aspects make the research approach of using historical figures in business ethics similar to philosophical inquiry. In other words, though the use of historical figures as a research approach in business ethics has some similarities with the historical research methodology and with the historical-comparative methods of research used in social sciences, it is the philosophical methodology where it primarily belongs to due to the similarity of some key tools (e.g., philosophical inquiry and logical argumentation), the ability to go beyond empirical causal links, and openness for normative aspects. Yet, unlike pure philosophical inquiry, the use of historical figures as a research approach is more oriented to practical applications, such as the role of business ethics in business. Moreover, in normative business ethics the use of historical figures is often utilized to give substantive and substantiated grounds for a point of argumentation or justification, say, for the rights theory or (Smith’s) free enterprise (see Bowie’s Chapter 5 on Kant as an example).

Specifics of Applying the Historical Figures Research Method

Business ethicists using historical figures as a research method typically derive their research questions or find support for their arguments from one of the two sources. First, scholars in business ethics analyze the works of great economic thinkers who laid down the foundations for the contemporary economic system and try to find their perspective on ethical aspects of doing business as “many of these economists were moral philosophers (and vice versa)” (Wicks, Reference Wicks1995: 603). It is often the case that the academic proponents of “cowboy capitalism” draw on particular parts of economic works of historical figures but miss, unintentionally or not, on the bigger context which provided the grounding and general moral directions for these very works. Torn out of context, these works breed a litany of academic misinterpretations and misunderstandings. For example, Werhane (Reference Werhane1991) compellingly showed that Adam Smith’s views on economic systems, with the emphasis on egoism and greed, were often misinterpreted. Rather, Smith’s widely read The Wealth of Nations should be viewed together with his Theory of Moral Sentiments, as the latter clearly points to the difference between individualism and egoism, as well as pinpoints the fact that competition takes place in the environment of mutual cooperation and coordination.

Secondly, business ethicists may draw on the ideas of moral philosophers who were not necessarily writing about business and economics, but whose ideas about morality in the society can be interpreted and analyzed to apply well to business. Edwin Hartman (Reference Hartman2015; Reference Hartman1996) did an amazing job of bringing Aristotelean virtue ethics to business, as well as Norman Bowie who applied Kantian moral theory to business settings (Bowie, Reference 23Bowie1999). No matter what particular source (economic or philosophical) business ethicists choose to consider, approaching business ethics research from a historical perspective and tracing its roots to the philosophical gurus of modern capitalism allows to strongly connect and ground the business ethics research in the work of some traditionally recognized, established philosophical figures and at the same time to critique those contemporary approaches to business ethics that have neglected some fundamentally important aspects of the discipline.

The research approach of using historical figures includes taking the contemporary theories in business ethics and juxtaposing them with the stream of thoughts of the great thinkers of the past. What would Adam Smith say about stakeholder theory? How would Karl Marx react to the call to create a new story of business different from “cowboy capitalism” and instead focused on the joint value creation – will the new story of business resolve many of Marx’s concerns? Would John Dewey see the importance of moral imagination in business settings the same way business ethics scholars see it today?

One way to see the methodological approach of using historical figures is through the search for the answers to the sequence of questions which taken together lead to a new perspective on a particular issue:

1. What is the problem in issue X that is at stake?

2. How would particular historical figures A and B have seen this issue X given their established viewpoints on a variety of issues? How appealing would their arguments be in strengthening one’s contemporary justification for addressing X?

3. What is the context (historical, political, philosophical) of their views?

4. What are the insights that we can gain from A and B on X? How would they differ?

5. What are the limitations of A and B’s views?

Another way to apply the research approach discussed in this chapter is to consolidate the thoughts of a historical figure on the topic of interest. Most great thinkers were prolific writers who often touched upon a multitude of topics briefly across multiple works, here and there, again and again. Thus, great research opportunity opens up for any scholar willing to go through many works of a particular historical figure, seeking and consolidating his or her thoughts pertinent to a particular topic while at the same time adding one’s own interpretation and triangulation where different pieces do not fully fit together: reconstructing as if from puzzle pieces one holistic view of that historical figure on this or that topic. Gregory Fernando Pappas’s work John Dewey’s Ethics (Reference 24Pappas2008) is one of the recent thoroughgoing research projects written in this way. In his work, Pappas provided a comprehensive overview of Dewey’s thoughts on moral experience that came as a result of Pappas’s analysis of Dewey’s numerous works, including Democracy and Education (1916), Reconstruction in Philosophy (1920), Human Nature and Conduct (1922), Three Independent Factors in Morals (1930), and Ethics (1932). Another example of a strong and successful application of this method would be McVea’s work (Reference McVea2007) in which he relied on Dewey’s philosophy to pave the way for bridging business ethics and American pragmatism.

Contemporary forms of business ethics are grounded in the free enterprise system (or in some cases, opposition to elements of that system), so referring back to historical figures sheds light on the understanding of many challenges we face today. In this chapter, we take four great thinkers from the past – John Locke, Adam Smith, Karl Marx, and John Dewey – and show how using historical figures can serve well for the research agenda of business ethics scholarship. We trace the beginnings of the free enterprise system from John Locke’s defense of human rights and property rights, through Adam Smith’s analysis of the importance of industrialization and free markets to economic growth, and Marx’s idea of the alienation of labor, the precursor of employee rights, and the critique of slave and child labor. We end with John Dewey’s pragmatic approach to moral judgment and decision making.

The Importance of John Locke for Business Ethics

Much of the contemporary literature in business ethics is built on rights talk. We begin, then, by going back to the seventeenth-century philosopher, John Locke, because it is Locke who developed the notion of what he called “natural” rights and that included rights to liberty, to work, to be remunerated for one’s work, and the right to privately owned property, cornerstones of any free enterprise system. In brief, in his well-known book, Two Treatises on Government, and in particular, The Second Treatise, Locke proposes what is today a very basic and standardly accepted view of human rights. Locke argues that because we are human beings, which, he assumes, is a unique and superior species (although Locke predates studies of species), human beings have basic rights. He calls these “natural rights,” because he was convinced that these rights are innate – part of who we are as human being, and God-given. Today, because of various religious complications with the term “natural rights,” we call these human rights or, better, “moral rights,” more secular terms. Moral rights are rights all human beings should have, as human beings, but rights that are not always recognized, operationalized, or defended.

However one names them, as Locke argues and rights theorists continue to argue, rights are those claims to which all humans have, inalienably, and equally, even if and when they are not acknowledged and violated. According to Locke, because we are born as human beings, we have, equally, all of us, the right to life. Because of that right, we have rights to survival. Additionally, as human beings, we are each unique individuals and thus have the right to liberty. That much seems natural today but it was not obvious at that time. Locke argues further that the rights to survival and liberty entail the right to work, and work, in turn, because it belongs to the worker, should be remunerated. He calls this archaically, receiving the “fruits of one’s labor.” Today we call that getting paid, and paid fairly, for one’s contributions. From this position, Locke then argues that one has rights to property one improves with one’s labor (the “fruits”). Note that in Locke’s day there was a great deal of unowned property, particularly in “America,” the underexplored and vast new continent where one could develop unowned property to one’s advantage. As ownership expands and as we develop political economies to protect our rights including property rights (Locke proposed forms of legislative democracy), property ownership expands beyond what is merely improved through one’s own labor, trade develops, and money becomes a means to trade and to pay workers.

It is from Locke that we appeal for the justification of free enterprise and private property, principles that are essential for capitalism. This too seems obvious, but its grounding in basic rights gives credence to free enterprise, a system often challenged by questioning the normative viability of property ownership, particularly as it has developed and expanded to large corporate and institutional holdings.

Locke also realized that the gain of property, even through one’s own labor, has limits and there should be enough good quality property left for others. In Locke’s words, “for this labour being the unquestionable property of the labourer, no man but he can have a right to what that is once joined to, at least where there is enough, and as good, left in common for others” (Locke, Reference Locke1980/1690: 19). Later Nozick referred to this as ‘Lockean proviso’ (Reference Nozick1974) and went on to set it as a criterion to determine whether some particular property acquisition could be judged as just or not.

Locke’s thinking is important for a number of reasons. Not only is it the basis for the continuing arguments defending the liberty of each individual and basic rights to property, it is also used against slavery. Locke’s thinking is the basis for what today is a plethora of rights declarations including the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which includes worker rights, and the 2000 the United Nations Global Compact, specifically aimed at global interactions, including those of commerce. More recently, in 2011, United Nations developed the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, often referred to as the Ruggie Principles, for its principal author, a set of principles that argues that corporations have specific obligations to respect human rights throughout their fields of operation. All of these proposals, each of which is voluntary with no specific sanctions, come out of Locke’s original theory. Thus standards for global corporations and international trade evolve from Locke’s original theories.

Given the importance of Locke’s ideas to business ethics, a number of management scholars continue to build on his ideas in their research. Hartman (Reference Hartman1996: 70) mentions that “Locke is the most famous of many who have argued that there is a kind of contract between the individual and his or her community and that this contract provides the basis for individuals’ rights and obligations with respect to one another.” Locke, along with other historical figures such as Plato, Hobbes, and Rousseau, as cursorily admitted by Donaldson and Dunfee (Reference Donaldson and Dunfee1994: 259), provided “the methodology of social contract” used by them for creating integrative social contract theory. Similar historical figures – Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau – were considered by Hsieh (Reference Hsieh2016: 437) when analyzing the origins of “traditional” social contract theory in comparison to “contemporary (as opposed to traditional) applications of social contract theory” in business ethics. Solomon and Higgins (Reference Solomon and Higgins1996: 199) summarized that “[a] number of philosophers, not only Locke but Hobbes and later Hume, Rousseau and Kant defended the conception of society as a ‘social contract’, further destroying traditional authority … and supporting the new emphasis on individual will and self-rule.”

Locke’s contribution to the contemporary human rights and the concept of justice is widely acknowledged in business ethics (Shaw & Barry, Reference Shaw and Barry1998; Santoro, Reference Santoro2010). De George (Reference De George1982) admitted that John Locke’s theory on the natural rights had an impact on the American Founding Fathers, and private property became a cornerstone of capitalism. Locke’s ideas influence business ethics scholarship directly or through the works of contemporary philosophers who based their theories on Lockean principles such as Robert Nozick in Anarchy, State, and Utopia (Reference Nozick1974). Solomon (Reference Solomon1993: 98), when analyzing “what a theory in business ethics is supposed to look like,” proposed to design a course on business ethics where the concept of justice would be “a natural introductory section, and John Locke on natural property rights is an appropriate inclusion.”

The “Father” of Free Enterprise: Adam Smith

Adam Smith is an eighteenth-century Scottish moral philosopher, widely read not only in the philosophical circles, but also by political theorists, economists, and social scientists. Because of his widespread influence, particularly to contemporary economics, it is well worth considering his thinking and approach when doing research in business ethics. Smith wrote only two books, the Theory of Moral Sentiments (1767) and the Wealth of Nations (1776), and many would claim it is the latter that is important to economics and business ethics.

Smith comes out of a Scottish tradition that accepts Locke’s theory of rights with one exception. Although adopting Locke’s labor theory of value – that laboring creates value, and thus should be rewarded – Smith argues that property rights are not inalienable rights, but rather conventional rights that are defined differently in different societies. Thus accepting that each of us has property rights, what that means and how that is spelled out depend on the political economy in which each of us dwells. This point is important for contemporary research on transnational corporations, since such companies often operate in communities where the idea of property is different from a Western, post-Lockean view. Unless one understands these differences, serious negative consequences can preclude successful global development. For example, Shell’s oil exploration in the Ogoni region of Nigeria failed to acknowledge ancient but unwritten tribal property rights, and initially Shell could not understand why the Ogoni were so against their oil development in that region.

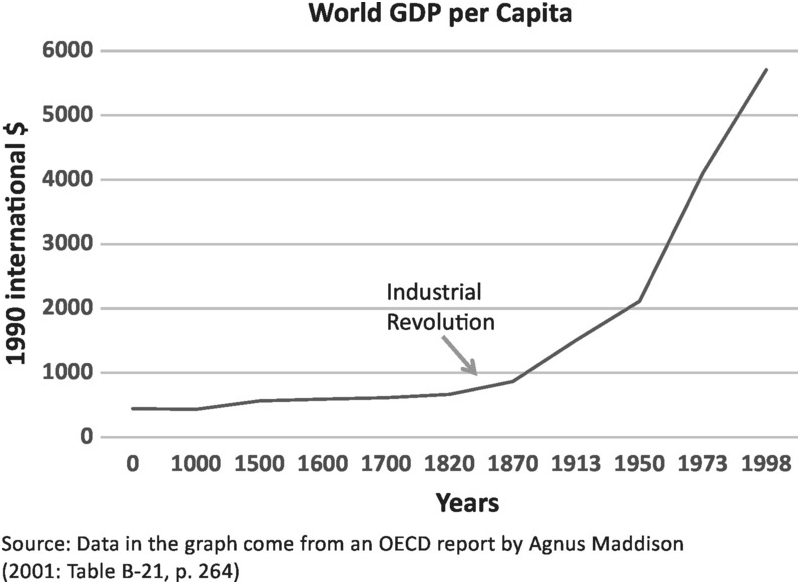

The labor theory of value, initiated by Locke’s theory of natural rights, is amplified by Smith. Smith locates economic growth through labor. He recognizes that because labor can create value, organizing and mechanizing labor (the thinking behind the industrial revolution) can create value for a community and thus wealth for a nation. Indeed, since the industrial revolution, of which Smith is the philosophical “father,” economic growth in the now-industrialized world has increased exponentially since 1776. Industrialization can also free workers from serfdom when labor is paid a living wage and when laborers are allowed to choose and change jobs at will. It was Smith who recognized the importance of free and industrialized labor as the key factor in economic growth. Indeed, according to Deirdre McCloskey, and Smith would agree, without industrialization a society cannot provide enough jobs, goods, and services to reduce endemic poverty and achieve economic well-being for the majority of the population (McCloskey, Reference McCloskey1985). Indeed, since the industrial revolution beginning in the late nineteenth century, economic growth in those countries who adapted this methodology has been and will continue to be exponential (see Figure 1.1). Going back to Smith for such grounding arguments is important, particularly as an antidote to those who question the capitalist system (Smith, 1776).

Figure 1.1 Economic growth after industrialization.

Smith himself never used the word “capitalism,” and he has often been misidentified as a laissez-faire economist, what today we might label as libertarian capitalism. But that is a misreading of Smith. For Smith, free exchanges work best when they are restrained by parsimony (rather than greed), when these exchanges are conducted fairly, when basic rights and the rule of law are respected and enforced, and when money is used as investment to create more value, not as an end in itself. If money accumulation becomes an end in itself, economic growth will be stunted and the economy will atrophy. It is worth rereading Smith for these reasons alone, as we live in a society where value is often measured by money rather than wealth creation (Smith, 1776).

Interestingly, Smith is also the father of the Separation Thesis, the critique of dividing business from ethics. Smith was a philosopher and a political economist and he could not imagine dividing these subjects into separate categories in inquiry.

There is one other useful point to be gleaned from Smith, his notion of the self as he develops that idea in his earlier book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments. In analyzing the idea of the self in that text, Smith argues that we are not merely behavioral beings. Rather, as human beings, we are capable of making moral judgments, both about oneself and others, and thus creating moral change. Because a human being is a conscious being who is also conscious of oneself, we are able to mentally step back from ourselves and our social interactions, taking what Smith calls an “impartial spectator” perspective. No one can completely disengage nor ever be completely impartial, but we are able to step back from our social, political, or economic situation, obtain what Michael Walzer calls a “critical distance” (Walzer, Reference Walzer2002), and be self-critics, thus the source of conscience, and critics of others and their behavior. This phenomenon accounts for individual and social change (Smith, 1767). The idea is important in business ethics, because it accounts for the fact that companies can examine themselves, revise their mission, goals, and direction, and reinvent themselves. This is not to conclude that all companies do this, nor is it to recognize that sometimes these changes are disastrous. However, this idea is very useful in understanding corporate atrophy or change, and provides tools for those who imagine that such changes are not possible.

The impartial spectator is also the source of thinking of the business ethicist as a social critic. According to Scott Sonenshein, “organizational members can use principles of morality within their business communities to practice moral criticism. ISC [internal social criticism] emphasizes discussions among organizational members geared toward unearthing thick moral principles and any contradictions between those principles and practices” (Sonenshein, Reference Sonenshein2005: 476). Sonenshein gets this idea from a contemporary political philosopher, Michael Walzer, but it originates with Smith. This is because the ability to be a social critic both within an organization and as an outside business ethicist depends initially on one’s ability to disengage, to get at a critical distance from the organization or political economy, that is, to engage oneself as an impartial spectator.

Among business ethicists who use historical figures as a research approach, Adam Smith is perhaps one of the most popular protagonists. The research on Adam Smith in business ethics has been actively growing over the last thirty years and by now there are at least several dozen studies in the area. Apart from Werhane’s above-mentioned book, Adam Smith and His Legacy for Modern Capitalism (Reference Werhane1991), and her previous works on Adam Smith, where the ideas of Adam Smith were thoroughly reinvestigated and applied to business ethics, there is a whole body of scholars who have explored Smith’s ethical foundations for capitalist activities (Sen, Reference Sen1987; Rothschild, Reference Rothschild1992; Sen, Reference Sen1993; Collins, Reference Collins1994; James & Rassekh, Reference James and Rassekh2000; Bragues, Reference Bragues2009; Wells & Graafland, Reference Wells and Graafland2012). Wilson (Reference Wilson1989: 70) showed in his analysis of Smith’s works that “Adam Smith provides us with a far richer and deeper assessment of the ethical aspects of capitalism than can be found in the writings of most present-day critics.” He mentions that “the Adam Smith who invented capitalism, described the useful effects of the invisible hand, and showed how the free pursuit of self-interest would lead to greater prosperity than any system of state-controlled exchanges was also the Adam Smith who, more deeply than anyone since, has explored the sources and power of human sympathy and the relationship between sympathy and justice” (Wilson, Reference Wilson1989: 66).

Gonin (Reference Gonin2015: 221) presented Smith’s “integrative conception of business and its contributions to the development of integrative theories of organizations and of business-society relations in the twenty-first century” where, referring to Adam Smith, “the business enterprise [is] primarily … the endeavor of an individual who remains fully embedded in the broader society and subject to its moral demands.” Huhn and Dierksmeier (Reference Huhn and Dierksmeier2016: 119) conducted an extensive review of the secondary literature written on Adam Smith by economists, business ethicists, and philosophers and concluded that “Smith, far from being an advocate of a value-free or even value-averse conception of economic transactions, stood for a virtue-based and virtue-oriented model of business.”

Overall, as long as we continue to explore the merits and drawbacks of our capitalistic society, we will inevitably continue to reinterpret Adam Smith.

Why Study Karl Marx?

Often in business ethics one ignores the work of Karl Marx, who, after all, was the founder of communism, an anathema to capitalism. However, we suggest that Marx is important in business ethics research for a number of reasons. First, Marx agrees with Smith that to create economic growth, a society must industrialize. Without that development, nations will continue to be mired in agricultural abject poverty for most of its population. But capitalism, spawned by the industrial revolution, has serious downsides, particularly for the worker whom, Marx contends, is promised independence through being able to choose her job, get paid in money, and is free to quit at any time. In fact, Marx points out, with a plethora of labor, companies can with impunity offer low wages because they can replace any worker with another. Thus, workers are not paid fully for the value of their labor input, and in factories they become alienated or distanced from what they produce, since their input is measured quantitatively and as merely measurable input rather than as the contribution of a person. Workers become alienated from their work, which seems to be no longer theirs; they are underpaid, and it is difficult to change jobs. Thus, the industrial revolution, while necessary to create jobs and expand worker pay, is only a stepping stone to what he imagines as a fairly anarchical communism where workers own the means of production (Marx, Reference Marx and Bottomore1844). While most of us will not buy into what he sees as an inevitable outcome of capitalism, historically, his critique of worker mistreatment and alienation has served as ongoing arguments in defense of worker rights. These arguments continue today, particularly in communities where there is virtually slave labor and/or where workers are not paid adequately for their contributions nor respected as human beings in the workplace.

Marx also worried that capitalism would evolve into economies that were focused on money as an end in itself rather than its value in creating wealth (see Marx, Reference Marx and Fowkes1867, Part III). These arguments, later revitalized by thinkers such as Michael Walzer (1993), are invaluable both for questioning the worship of money and in helping us rethink the purpose of free enterprise, which was originally to create widespread economic well-being. Reading Marx does not entail buying into his systemic prognosis, but rather leads one to mine some of his particular arguments that are still relevant today.

Initially, as the field of business ethics was just emerging, some scholarly studies built around Marxism referenced the great philosopher to highlight what these scholars considered to be the cynicism of the business ethics world. For instance, Massay (Reference Massey1982) speculated on Marx’s would-be response to the newly sprung phenomenon of business ethics. He argued that Marx would probably claim that business ethics was conceived by employers who, driven by declining profits and the desire to maintain legitimacy for capitalistic system, decided to “discipline individual members of the bourgeoisie so that they will refrain from pursuing their individual interests when these conflict with the interests of their class” (Massay, Reference Massey1982: 301).

With further development of the field, Marxian philosophy served to explain important business ethics concepts. Corlett (Reference Corlett1998), admitting that Marx does not provide sufficient reasons for building a comprehensive theory of business ethics, nevertheless underlined that Marxian philosophy could provide a number of important contributions to business ethics. As a starting point, it could serve to outline a more comprehensive description of capitalist political economies by admitting employee-related problems, e.g., their alienation and oppression, and struggles for power among business people. Further, it could help build better communities by analyzing “socio-economic and political power internal and external to business communities and devote attention to matters of justice (retributive and distributive) and fairness” (Corlett, Reference Corlett1998: 100) and help with fostering “the commitment to a community-oriented sense of moral and legal responsibility” (Corlett, Reference Corlett1998: 101). Along similar lines, Linz and Chu (Reference Linz and Chu2013) analyzed the relationship between work values and economic environment comparing Marxian views with those of Weber. Their empirical study showed that values are determined by the economic environment, thus reasserting the Marxian link between work values and economic environment (Linz & Chu, Reference Linz and Chu2013: 444). De George (Reference De George2006), in his critique of Rorty’s views on philosophic contribution to business ethics, which also discussed the role of Marx, mentioned that “Marx got much of the problem right; he got the solution wrong … [t]hose in business ethics focus on business and see it not only as one of the causes of the ills that Marx described but as one of the key players in the amelioration of those ills” (De George, Reference De George2006: 389). Shaw (Reference Shaw2009: 565) analyzed “some links, and some tensions, between business ethics and the traditional concerns of Marxism,” attempting to explore whether Marx was right in his considerations that business ethics was an improbable entity in capitalistic environment due to its strong inclination to greed, and thus a tendency to produce unethical behavior. The examination of Marx’s works and the contemporary development in the field of business ethics allowed Shaw to conclude that “far from being impossible, business requires and indeed presupposes ethics and that for those who share Marx’s hope for a better society, nothing could be more relevant than engaging in the debate over corporate social responsibility” (Shaw, Reference Shaw2009: 565).

Overall, Marx-inspired research in the area of business ethics, to a large extent, tends to outline challenges within capitalism. Some business ethicists go beyond this stage and try to tap into Marxian philosophy to seek an array of potential solutions to meet these challenges. Yet, most management scholars, though agreeing with Marx’s criticism of capitalism, do not offer or see any feasible alternative to the present capitalistic system. As Kerlin (Reference Kerlin1998) put it, while using the Marxism ideas to criticize capitalism, “the answer may be that no other economic system is viable at this moment in history” (Kerlin, Reference Kerlin1998: 1717). Many Marx’s tenets resonate well with business ethicists and have been widely adopted in the business ethics field, especially when it comes to the evaluation of the contemporary economic landscape. As Joanne Ciulla (Reference Ciulla2011: 338) said in her Presidential Address for the Society of Business Ethics, “you do not have to read Karl Marx to understand this problem,” referring to the issue of work and wages, when some businesses may get advantage from the work of others by underpaying their employees.

Dewey’s Meliorism at the Heart of Business Ethics

John Dewey’s contributions are well acknowledged in the areas of education and philosophy. However, in business and business ethics, Dewey remains largely unexplored, especially if compared to John Locke, Adam Smith, and Karl Marx. We believe that Dewey’s philosophical pragmatism has much to add to the contemporary business ethics discussion.

Dewey argues that evaluating each situation through the prism of some selected single highest end meant to perfectly fit all human endeavor – be it self-realization, holiness, happiness, or something else – is misleading, if not to say counterproductive. The world is complex and multifaceted and there is no one unique panacea for the plethora of moral problems we encounter. Instead, there are multiple factors that require our consideration any time we face a morally puzzling situation. In Dewey’s words:

Morals is not a catalogue of acts nor a set of rules to be applied like drugstore prescriptions or cook-book recipes.

The blunt assertion that every moral situation is a unique situation having its own irreplaceable good may seem not merely blunt but preposterous. Let us, however, follow the pragmatic rule, and in order to discover the meaning of the idea ask for its consequences. Then it surprisingly turns out that the primary significance of the unique and morally ultimate character of the concrete situation is to transfer the weight and burden of morality to intelligence. It does not destroy responsibility; it only locates it. A moral situation is one in which judgement and choice are required antecedently to overt action. The practical meaning of the situation – that is to say the action needed to satisfy it – is not self-evident. It has to be searched for. There are conflicting desires and alternative apparent goods. What is needed is to find the right course of action, the right good.

Where morality can help is with providing methods of inquiry which are to be used to identify issues specific to each situation and to create some working hypotheses to deal with those issues. This inquiry is based in intelligence and is coupled with moral traits such as “wide sympathy, keen sensitiveness, persistence in the face of the disagreeable, balance of interests enabling us to undertake the work of analysis and decision intelligently” (Dewey, Reference Dewey1920:164). We need to realize that each situation is unique and requires a more scrupulous attention to its context than just the mechanical appliance of generalized conceptions. Similarly, the abundance of ethical issues we observe in business settings deserve individualized attention. Each ethical problem has its specific individualized context, which we should attend to when developing our attitude to it.

Pappas, in his John Dewey’s Ethics that analyzed and put together Dewey’s thoughts on ethics from many of his writings, mentions that in Dewey’s view, “[s]ituations in their qualitative immediacy and uniqueness are primary and prior to any distinction between subject and object” (Pappas, Reference 24Pappas2008: 86). When we talk about morality, “moral qualities and moral decisions are context-dependent and have their home and meaning in a particular situation” (Pappas, Reference 24Pappas2008: 85). A moral problem takes place when a person starts struggling with the situation as her previous experience does not help resolve the current problem in a proper way. When a moral problem occurs, “[t]he fluidity of everyday life is blocked and experienced as a unique ambiguity, confusion, disharmony, conflict, or pain that pervades one’s situation” (Pappas, Reference 24Pappas2008: 90). It does not take much to realize when ethical issues are at the core of the problem as “insofar as a situation is experienced as morally problematic then it really is problematic” (Pappas, Reference 24Pappas2008: 91).

Dewey mentions that “inquiry, discovery take the same place in morals that they have come to occupy in sciences of nature.” The problem is that “remote and abstract generalities promote jumping at conclusions” which may not reflect a situation adequately. According to Dewey, past decisions and old principles cannot be used to justify an action so “shifting the issue to analysis of a specific situation makes inquiry obligatory and alert observation of consequences imperative” (Dewey, Reference Dewey1920: 174). Pappas explains it in his analysis of Dewey’s works that moral deliberation, involving analysis and synthesis, and moral imagination as a dramatic rehearsal are needed to resolve a morally puzzling situation:

In any process of inquiry we can make a functional distinction between phases of doing and undergoing as well as phases of analysis and synthesis … Analysis is what we do when inquiry is centered on making some finer discrimination of the parts that make up our problematic situation. Synthesis takes place when we are concerned with weighing how the parts contribute to making an overall judgement … The final judgement about what we ought to do is a synthesis that results from the analysis of the situation as a whole, but it is only the final step in a series of tentative overall judgements that have occurred throughout the entire process of deliberation.

Reasoning provides us with the inferences needed to go beyond what we have, or it helps us elaborate our suppositions in light of other beliefs. Imagination in the form of a dramatic rehearsal helps us survey and test our options.

Dewey argues that many moral problems arise because we treat worthy things as instrumental and not intrinsic. As he states, “every case where moral action is required becomes of equal moral importance and urgency with every other” (Dewey, Reference Dewey1920: 175). Extrapolating his example on health to business, if the need of a particular situation shows that some of the company employees require improvement of health, “then for that situation health is the ultimate and supreme good. It is no means to something else. It is a final and intrinsic value. The same thing is true of improvement of economic status, of making a living” (Dewey, Reference Dewey1920: 175).

For Dewey, the highest importance in morality is the direction along which a person is currently moving along, not the previous accumulation of good and bad deeds.

The bad man is the man who no matter how good he has been is beginning to deteriorate, to grow less good. The good man is the man who no matter how morally unworthy he has been is moving to become better. Such a conception makes one severe in judging himself and humane in judging others.

This sends two strong messages to contemporary corporations. First, no matter how good a particular company was in the past, it still has to keep up with ethically praiseworthy behavior, here and now. Second, even if a particular company was suspect in wrongdoing, there is still a chance to restore its reputation by wholeheartedly moving in a positive direction.

The ultimate aim, for Dewey, is not static, but about the growth per se toward a positive end. It is a never-ending progress without a limit, “it is the active process of transforming the existent situation. Not perfection as a final goal, but the ever-enduring process of perfecting, maturing, refining is the aim of living” (Dewey, Reference Dewey1920: 177). Business organizations should constantly strive to improve in all directions, as the “[g]rowth itself is the only moral ‘end.’” Dewey was a strong proponent of meliorism, “the belief that the specific conditions which exist at one moment, be they comparatively bad or comparatively good, in any event may be bettered” (Dewey, Reference Dewey1920: 178).

Though not accepting utilitarianism in all its manifestations, Dewey appreciated that it “insisted upon getting away from vague generalities, and down to the specific and concrete” (Dewey, Reference Dewey1920: 180). Dewey combined meliorism and utilitarianism in a way that doing good should bring a pleasant experience, “goodness without happiness, valor and virtue without satisfaction, ends without conscious enjoyment – these things are as intolerable practically as they are self-contradictory in conception.” Dewey rejected Kant’s view of doing good as of a pure duty, and believed that it should be enjoyable by a doer. Yet, Dewey cautions us that meliorism should not be mixed with optimism which, in his view, is “the consequence of the attempt to explain evil away.” Saying that “the world is already the best possible of all worlds” could be considered as “the most cynical of pessimisms”. (Dewey, Reference Dewey1920: 178)

Dewey was a pragmatist who saw the meaning of ideas in their consequences. In his Reconstruction in Philosophy, Dewey framed the direction for the development of our society and business. For Dewey’s time, those ideas may have been too progressively radical to be easily accepted; and though nowadays we are a bit closer to their full implementation, there is still a way to go, for social institutions in general and business in particular:

Government, business, art, religion, all social institutions have a meaning, a purpose. That purpose is to set free and to develop the capacities of human individuals without respect to race, sex, class or economic growth.

Democracy has many meanings, but if it has a moral meaning, it is found in resolving that the supreme test of all political institutions and industrial arrangements [business] shall be the contribution they make to the all-around growth of every member of society.

Dewey mentioned business as one of the key responsible parties for fostering moral values. A hundred years ago, Dewey already anticipated conversations that we are having nowadays about the purpose of business: should it be rendered as a financial metric only or is there anything beyond that? We expect that the role of Dewey in business ethics will significantly grow over time incorporating the idea of focusing on the context of each moral situation instead of using shelf-ready universal guidelines, the concept of melioration, the elevation of the current direction of moral development and his questioning of economic gains as the primary purpose of business and his appeal to business to develop human capacities, primarily and foremost. Dewey’s prioritization of a situation over a subject and object means that “[w]e need not choose between deontology, virtue ethics, and consequentialism” (Pappas, Reference 24Pappas2008: 2) as a universal wand that can solve any morally problematic situation and “the quality of the problematic situation determines which rules of the total system are selected” (Pappas, Reference 24Pappas2008: 97). Dewey’s ethics allows us to depart from the myopic view of moral problems through only one possible lens, and makes business ethics much more realistic, and much more varied and interesting.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we attempted to describe the research approach of using historical figures as well as to outline some possible directions for research that relies on the philosophies of established historical figures. This research approach has been relevant in the business ethics field since the inception of the field. Contemporary business ethics thinking often breeds on the influential thoughts of the great thinkers of the past. First, business ethicists look at the great economists – e.g., Adam Smith and Karl Marx – who laid down the foundations for the current economic system, and examine their attitude (as expressed directly in their works or reconstructed through some kind of analysis) toward the moral side of business. Second, business ethics scholars look at the moral philosophers – e.g., John Locke and John Dewey – whose ideas on ethical behavior and morality in general can be well adapted to fit the ethics of business organizations as social institutions.

It is impossible to imagine the development of business ethics without the use of historical figures. This research approach goes beyond referencing historical figures to create a line on the literature review page; rather, it is a holistic reconstruction of the concepts, arguments, and logic that eventually create a picture of a certain moral philosophy that bridges the past with present research seeking to explain the contemporary business world.