International economic cooperation below the multilateral level has become a staple feature of the world economy. Besides bilateral trade agreements, an important part of this development occurs in the context of regional organizations, many of which have come to endorse ambitious objectives for economic cooperation such as common markets and even economic unions since the early 1990s (Haftel Reference Haftel2013; Duina Reference Duina2016). Curiously, these decisions often mirror basic institutional choices of the European Union (EUFootnote 1 ), the most prominent and successful ‘institutional pioneer’ of regional economic cooperation (Lenz and Burilkov Reference Lenz and Burilkov2017). Consider three prominent regional organizations in the developing world: the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the Common Market of the South (Mercosur), and the Southern African Development Community (SADC). Whereas all three initially limited cooperation to functional coordination of diverse policies, they now share the objective of establishing a common market that involves the free flow of goods, services, capital, and labor by gradually adopting additional legal instruments.

These converging institutional choices in regional economic cooperation can be the result of (1) like, yet independent, reactions to similar structural conditions, (2) external imposition by hegemonic actors, or (3) diffusion (see Elkins and Simmons Reference Elkins and Simmons2005, 35). In this article, I develop the third explanation by proposing a cognitive mechanism of diffusion – termed frame diffusion – to explain the adoption of similar common market objectives in structurally diverse regional organizations.

Combining foundational work on framing (Goffman Reference Goffman1974; Snow and Benford Reference Snow and Benford1988) with the literature on diffusion in comparative politics and international relations (Weyland Reference Weyland2005; Simmons, Dobbin and Garrett Reference Simmons, Dobbin and Garrett2006; Shipan and Volden Reference Shipan and Volden2008), I argue that processes of theorization transform the experience of successful institutional innovators into abstract cognitive schemas, which link a particular understanding of a cooperation problem to specific institutional solutions. As policymakers in other contexts encounter similar cooperation problems, they adopt framed institutional solutions, independently of the wider material context in which they are embedded. As a result, frame diffusion leads actors in structurally diverse contexts and in the absence of outside imposition towards similar institutional choices, which results in institutional convergence at the macro level.

However, I also posit that this process of frame diffusion is conditional. Frames retain ideational affinities with the organizations in which they originate, but theorization broadens this affinity to extend to particular organizational types, as defined by their social purpose. As a result, specific frames are seen as valuable in specific types of organizations. Where policymakers pursue other social purposes, they rely on alternative frames and thereby cement institutional variation rather than induce institutional convergence. Regarding the empirical terrain of regional economic cooperation, I juxtapose two distinct social purposes – community and market building – and posit that the common market frame is likely to diffuse among regional organizations that share a community building purpose. Overall, I argue that frame diffusion is necessary to understand the specific form that institutional choices in international economic cooperation take.

This argument builds on, and extends, Strang and Meyer’s (Reference Strang and Meyer1993) ground-breaking idea that framing and diffusion arguments can be successfully married. I further develop their argument by drawing explicitly on the cognitive literature and by transferring it from the domestic to the international level. The main theoretical contribution of the present article is to develop a new cognitive mechanism that conceives frame-based decision-making as a form of diffusion, thereby bringing the literatures on framing and on diffusion into conversation with each other. Doing so has distinct analytical advantages for both literatures. On one side, scholars of diffusion have largely neglected the insights provided by the framing and cognitive literatures, particularly the ‘channeled’ nature of much institutional choice. In most diffusion arguments, the cognitive dimension remains implicit and, where it is made explicit, it tends to be pitched as an alternative to existing diffusion mechanisms (see, e.g., Weyland Reference Weyland2005; Poulsen Reference Poulsen2014). The argument advanced in the article, by contrast, suggests that explicating this cognitive dimension helps us both to identify important ‘blind spots’ of existing treatments of diffusion mechanisms and to show the significant conceptual complementarities that exist between them. Thus, it promotes a focus on conceptual complementarities rather than opposites between different theoretical approaches (an argument with a similar spirit is that advanced in Jupille, Mattli and Snidal Reference Jupille, Mattli and Snidal2013). I develop these implications in the conclusion.

On the other hand, scholars of frames in comparative politics have focused on frames’ endogenous origins, neglecting the fact that they might also have international origins and thus diffuse across organizations. As Benford and Snow (Reference Benford and Snow2000, 628) noted in a review of the literature, ‘To date, few movement framing scholars have considered diffusion issues.’ Yet, whereas an endogenously rooted conception of frames is analytically useful in understanding divergent institutional choices across structurally similar situations (see, e.g., Bleich Reference Bleich2002), the present article aims to show that the mechanism of frame diffusion is useful in accounting for converging institutional choices in structurally diverse settings.

The article proceeds in three parts. The next part clarifies the theoretical puzzle by examining, in relation to the three cases under study, three prominent arguments – drawn from international political economy, neofunctionalism, and realism – that have been advanced to explain regional economic cooperation. I argue that these arguments offer important insights into the general prerequisites for economic cooperation in all three regions, but are largely indeterminate regarding its specific institutional form. Next, I theoretically develop the mechanism of frame diffusion and discuss the emergence and evolution of relevant frames in the current context, before spelling out some observable implications. I then offer a plausibility probe by comparing critical episodes of institutional choice in the most different regional organizations; namely, ASEAN, Mercosur, and SADC. Rather than definitive, the analysis is intended to be illustrative of the theoretical idea that transnational frames can guide policymakers across structurally different contexts towards similar types of institutional choices in regional economic cooperation, and to suggest that this process was at play in the adoption of common market objectives in ASEAN, Mercosur, and SADC.

These cases are useful for illustrating the argument because they differ from the EU on a number of important structural variables, including economic profiles and development levels, dominant regime type, the distribution of power among member states, dominant legal systems, as well as cultural conditions such as dominant religion and civilizational category that have been argued to affect the economic liberalization strategies of states (for a good overview, see Mansfield and Solingen Reference Mansfield and Solingen2010). This makes it possible to control for these variables largely by design, as in a most different systems design (Online Appendix A provides a schematic overview of these differences). Moreover, the three cases can be interpreted as least likely cases for the adoption of common markets because, unlike in many other regional organizations in the developing world, policymakers in these three regions explicitly rejected EU-style integration initially because they perceived it as an overly ambitious form of economic cooperation and therefore inadequate for their specific context (see Campbell, Rozemberg and Svarzman Reference Campbell, Rozemberg and Svarzman1999, 56–64; Lee Reference Lee2003, 47; Severino Reference Severino2006, 4–6). In sum, these cases are useful for illustrating the theoretical argument and important to understand in their own right.

Puzzle: converging institutional choices in regional economic cooperation

Even though the EU might be the most prominent and successful exponent of regional economic cooperation, it is not the only one that pursues ambitious cooperation objectives. The members of ASEAN, the Southern Cone/Mercosur, and SADC have similarly started to pursue the objective to establish a common market that involves the free movement of goods, services, capital and labor, and, in Mercosur and SADC, also a customs union, through a gradual process that involves some degree of harmonization of national legislation, and therefore the adoption of secondary legal instruments at the regional level. This approach to economic cooperation is distinct from that taken in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which aims to achieve, through a one-off deal, a more limited and less intrusive free trade area that encompasses primarily trade in goods and services, plus some rules on investment. Table 1 shows these gradually converging institutional choices across two central episodes of organizational evolution.

Table 1 Increasing convergence in institutional choices in three regional organizations

ASEAN=Association of Southeast Asian Nations; Mercosur=Common Market of the South; SADC=Southern African Development Community.

Source: Author’s compilation on the basis of official documents.

The analytical focus on institutional convergence is not to deny that important differences exist between these four organizations regarding the details of market integration, the institutional frameworks that accompany them, and the extent to which codified objectives have actually been achieved (for overviews, see Haftel Reference Haftel2013 and Gray Reference Gray2014). Nevertheless, I maintain that the adoption of common market objectives, codified in formal treaties and often accompanied by detailed action plans, is important, for two reasons. First, they serve as guiding frameworks for more detailed agreements and secondary legislation that, upon domestic ratification, are binding on member states. Second, they shape expectations among social actors regarding the future direction of economic policies in a region. Furthermore, the empirical phenomenon of converging institutional choices across structurally dissimilar contexts poses a theoretical puzzle that merits exploration.

What explains these converging institutional choices? Existing arguments suggest that choices similar to those in the EU are the result of policymakers in the three regions reacting rationally to similar incentives and constraints, or of powerful outside actors imposing the same choices across different organizations – the first two categories of explanation mentioned in the introduction. Even though they offer important insights into the general prerequisites for economic cooperation in all three regions, I suggest that they are indeterminate regarding the specific form that such cooperation takes. In particular, I argue that they cannot explain why policymakers in all three regions eventually moved beyond a NAFTA-style free trade agreement (FTA) to endorse a more ambitious common market objective. I consider the three main arguments in turn.

The first argument, advanced by scholars of international political economy, focuses on economic interdependence and private interest groups that lobby governments in order to facilitate transnational economic exchange. Recent decades have witnessed technological advances that expanded opportunities for international economic transactions. When tariff and non-tariff barriers continue to hamper cross-border trade, international agreements can be powerful tools to reduce transaction costs and to credibly commit states to liberal economic policies. From this perspective, private interest groups are prompted into action when the transaction costs of, and the potential for increasing, transnational economic exchange are high (Milner Reference Milner1995; Mattli Reference Mattli1999). Consequently, the ambition of regional economic cooperation varies with opportunities for, and constraints on, transnational economic exchange.

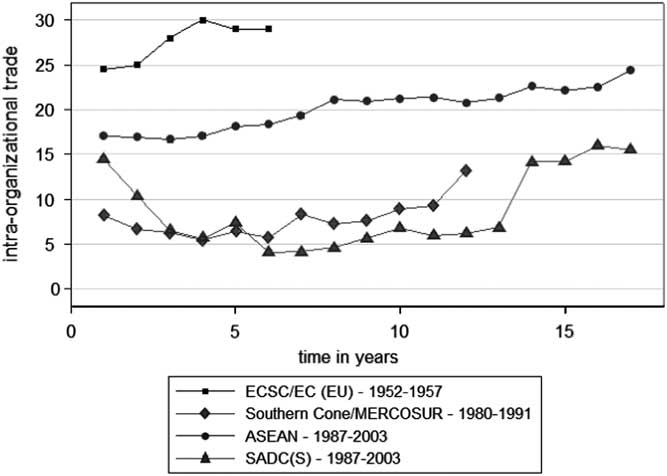

There is little doubt that the constraints on coordinated economic liberalization lessened with domestic economic liberalization in many member states in the 1980s and 1990s. A broad convergence in domestic economic policies has rendered ambitious regional economic cooperation possible, as this argument suggests. It is also true that large increases in economic interdependence since the 1970s have enhanced general incentives for international economic cooperation. However, in the absence of converging regional incentives and strong interest group lobbying, this argument is largely indeterminate regarding the specific institutional form of resulting cooperation. Figure 1 sketches trade interdependence – a widely used proxy for underlying economic incentives – across the four organizations in the 5 years prior to key decisions on the deepening of regional economic cooperation. The figure indicates that economic incentives are generally lower in the three regions than they were in Europe in the 1950s, a decade after a devastating war had destroyed those countries’ economies.Footnote 2 Varying and, in absolute terms, comparatively low levels of trade interdependence in the three cases are difficult to reconcile with converging institutional choices regarding the establishment of a common market. This assessment is shared in the secondary literature. In an analysis of economic regionalism in Asia and the Americas, Haggard concluded that there is ‘little evidence for the theory that higher levels of interdependence generate the demand for deeper integration’ (Reference Haggard1997, 45). Similarly, in a recent review of economic integration in Africa, Draper proposed that regional economic cooperation ‘does not hold nearly as much potential to overcome it [under-development] as integration with dynamic and large external markets’ (Reference Draper2012, 78).

Figure 1 Trade interdependence in four regional organizations. ASEAN=Association of Southeast Asian Nations; Mercosur=Common Market of the South; SADC=Southern African Development Community. Source: Own elaboration on the basis of the Unu-Cris trade database: http://www.cris.unu.edu/riks/web/data/customIndex, measure on intra-regional trade share; for the EU, data is from Eichengreen (Reference Eichengreen2008) on the basis of IMF Direction of Trade Statistics, 1948–1980.

Moreover, interest groups did not lobby for this specific institutional form. In fact, such groups appear to have been either irrelevant or even opposed to the institutional choices in question. In a detailed historical study of the construction of Mercosur, Gardini noted that these groups’ ‘initial indifference shifted to reluctance and skepticism, especially in Argentina’ (Reference Gardini2006, 8). Similar assessments dominate the literature on ASEAN. The former Secretary-General Rodolfo Severino stated flatly, ‘governments feel no pressure from ASEAN business to move faster on regional economic integration’ (Reference Severino2006, 249). In SADC, business interests are notable for their absence from the secondary literature; they are simply not mentioned. In general, proponents of this argument admit its potential indeterminacy, as Mansfield and Solingen noted, ‘intraregional and extraregional bilateral, trilateral, and region-wide PTAs [preferential trade agreements] are compatible with internationalizing coalitions’ (Reference Mansfield and Solingen2010, 155).Footnote 3

The second argument, advanced by neofunctionalists, focuses on endogenous spill-over dynamics under conditions of technological progress and economic interdependence. This argument proposes that processes of regional economic cooperation become more ambitious as a result of self-reinforcing dynamics associated with the functional connectedness of policy fields as well as supranational entrepreneurship. In this account, supranational institutions with meaningful autonomous capacity play a key role in nourishing support for, and themselves pursuing integrative agendas towards, more ambitious forms of economic cooperation (Haas Reference Haas1958; Stone Sweet and Sandholtz Reference Stone Sweet and Sandholtz1997). It follows that the ambition of regional economic cooperation grows with both economic interdependence and the existence of supranational entrepreneurs.

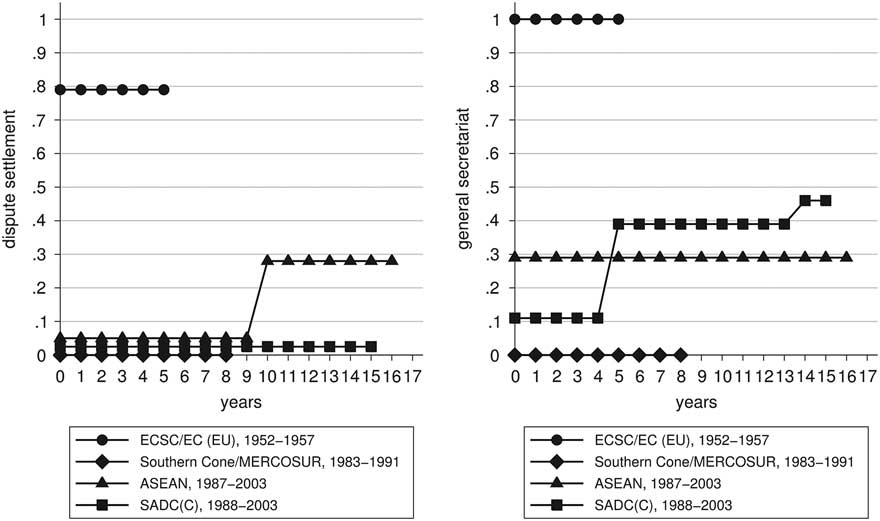

Again, this argument points to important prerequisites for economic cooperation in the form of growing incentives and declining constraints, but it is indeterminate regarding the specific institutional form resulting from it in the absence of supranational entrepreneurship. Structurally, the autonomy of institutions varies radically across the cases, and is rather limited outside of the EU. Drawing on the Measure of International Authority (MIA) data set (Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Marks, Lenz, Bezuijen, Ceka and Derderyan2017), Figure 2 compares the autonomy of the two main regional institutions – dispute settlement mechanisms and general secretariats – in the 5 years leading up to key decisions on regional economic cooperation (see Online Appendix B for details on coding). More autonomous dispute settlement mechanisms were created following key decisions on regional economic cooperation, especially in the Southern Cone/Mercosur and SADC. General secretariats are somewhat stronger, but their independence also varies widely across cases. Overall, this variation does not point towards converging institutional choices. The secondary literature bolsters this assessment. Unlike the 1992 program in Europe (see Sandholtz and Zysman Reference Sandholtz and Zysman1989), supranational institutions are far from being an important facilitator of negotiations for more ambitious economic cooperation in the other regions. The institutional choices examined in this article are the result of a process of intergovernmental negotiations that, most observers concur, are largely monopolized by governments (see Lee Reference Lee2003; Malamud Reference Malamud2005; Ravenhill Reference Ravenhill2010).

Figure 2 Formal autonomy of selected regional institutions in four regional organizations. ASEAN=Association of Southeast Asian Nations; Mercosur=Common Market of the South; SADC=Southern African Development Community. Source: Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Marks, Lenz, Bezuijen, Ceka and Derderyan2017, partly based on own calculations on the basis of their coding scheme.

A third argument, inspired by realism, emphasizes the role of hegemonic outside actors in imposing convergent institutional choice by manipulating target governments’ opportunities and constraints; what Elkins and Simmons (Reference Elkins and Simmons2005) call ‘hegemonic coordination.’ Hegemons, or the international organizations through which they act, often advance particular institutional choices elsewhere in the pursuit of geostrategic or economic interests. Countries that are dependent on outside actors are particularly susceptible to this pressure.

This argument also provides insights into the question at hand. There is no doubt that international financial institutions played an important role in advancing domestic economic liberalization through structural adjustment programs in the 1980s, especially in the Southern Cone and Southern Africa (Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman1992; Teichman Reference Teichman2001). Again, this convergence in domestic economic policies was a necessary prerequisite for ambitious regional economic cooperation. However, hegemons did not impose a specific institutional choice, which renders this argument indeterminate for the question at hand. In fact, international financial institutions were not only indifferent to cooperation beyond unilateral liberalization; they also criticized regional organizations for undermining multilateral liberalization and for diverting trade (see Yeats Reference Yeats1998). Moreover, especially in the SADCC case, internationally imposed austerity measures put the continued viability of regional cooperation at risk (see, e.g., SADCC Secretariat 1987, 70). Thus, the actions of international financial institutions undermined, rather than supported, the specific institutional form that ultimately emerged.

On the other hand, the United States has operated mainly through a series of bilateral trade deals in the context of larger cross-regional frameworks such as Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation or the Free Trade Agreement of the Americas. While these initiatives certainly facilitated coordinated economic liberalization, many observers agree that they have weakened rather than strengthened ambitious regional economic cooperation (for an overview, see Haggard Reference Haggard1997). The EU is the only global power that supports such endeavors. However, many of the relevant decisions were made prior to the EU’s direct engagement with them. With the potential exception of SADC, a case I discuss below, there is little evidence that pressure from the EU drove those decisions (see also Lenz Reference Lenz2012).

In conclusion, existing explanations of economic regionalism, and of international economic cooperation more broadly, conceive of converging institutional choices as the result of independent reactions to similar structural conditions, or of outside imposition. While all of these arguments provide insights into the changing incentives and constraints for regional economic cooperation, they are largely indeterminate regarding the specific institutional form that such cooperation takes. Thus, the explanatory challenge is to account for the adoption of a specific institutional form of regional economic cooperation (common markets) over a plausible alternative (FTAs) across settings that remain structurally diverse and in the absence of outside imposition. Below, I suggest that the concept of frame diffusion provides a plausible response to this challenge.

Theorizing frame diffusion

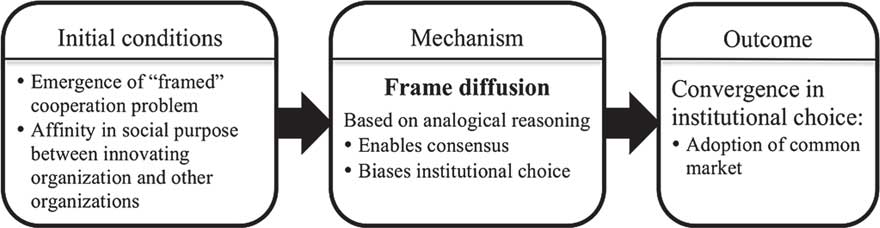

The mechanism of frame diffusion combines (1) a specific object (frames) with (2) a process (diffusion) by which that object exerts an impact on political decision-making, resulting, under certain conditions, in (3) converging institutional choices across structurally diverse contexts at the macro level. I discuss these three elements of the mechanism in turn, before sketching the evolution of the common market frame, and its main alternative, in regional economic cooperation and outlining some observable implications of the argument. The frame diffusion mechanism is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Mechanism of frame diffusion.

What are frames and how do they emerge?

Frames are cognitive tools that help actors organize information in a complex environment. In his pioneering work on the topic, Goffman (Reference Goffman1974, 21) defined frames as ‘schemas of interpretation’ that help individuals ‘to locate, perceive, identify, and label’ events. By serving as interpretive frameworks, they imbue these events with meaning, and thereby create shared understandings among actors that legitimate and motivate action. Frames have both a diagnostic and a prognostic element (see Snow and Benford Reference Snow and Benford1988, 199–201). They allow actors to identify a problem in terms of its specific attributes and underlying causes, and suggest solutions by specifying strategies to deal with it. Thus, frames can be seen as cognitive problem–response schemas that associate specific problems with particular solutions (on this notion in cognitive psychology, see Fiske and Taylor Reference Fiske and Taylor2013).Footnote 4 In so doing, frames emphasize certain aspects of a problem and de-emphasize others, thereby excluding alternative interpretations and solutions. As Entman noted, frames affect outcomes ‘by selecting and highlighting some features of reality while omitting others’ (Reference Entman1993, 53). In short, frames shape perceptions, and therefore action.

From this perspective, frames are prominent institutional innovations that have become theorized in abstract terms.Footnote 5 Institutional innovations solve an existing cooperation problem by novel institutional means and thereby deviate from established institutional forms. Thus, institutional innovators have ‘the capacity to imagine alternative possibilities’ (Emirbayer and Mische Reference Emirbayer and Mische1998, 963). Consider the following example. After the First World War, United States President Woodrow Wilson sought to stabilize the international system, not in the traditional way by renewing a balance-of-power-logic, but by institutionalizing the ‘new’ idea of collective security through the League of Nations. Wilson translated an institutional form that had hitherto been known only in the domestic context to the international level upon the presumption that it would work in similar ways. Thus, he innovated institutionally by enacting what Suganami (Reference Suganami1989) has termed the ‘domestic analogy.’ However, institutional innovations tend to be geared towards solving a specific cooperation problem that emerges in a particular context; that is, they often arise in unique circumstances. How do broadly applicable frames result from such situations?

Frames form when an institutional innovation is abstracted from the specific context in which it originally emerged. This process involves translating an innovation into a typical instance of a more general relationship, or a generalized problem–response sequence – a process that facilitates the innovation’s use in diverse contexts. Strang and Meyer termed this phenomenon ‘theorization’ and defined it as the ‘development and specification of abstract categories and the formulation of patterned relationships such as chains of cause and effect’ (Reference Strang and Meyer1993, 492). Theorization involves the interpretation of regularities, the identification of similarities across diverse contexts, and the provision of ‘rational’ reasons why these similarities are theoretically meaningful. As Strang and Meyer noted, theorization is important because ‘without such [theorized] models, the real diversity of social life is likely to seem as meaningful as are parallelisms’ (Reference Strang and Meyer1993, 492). While institutional innovators themselves may engage in theorization because they have an interest in translating their innovation into a generalized frame that is more widely applicable (see Meyer and Rowan Reference Meyer and Rowan1977, 353), theorization is most credible when it involves ‘culturally legitimated theorists’ (Strang and Meyer Reference Strang and Meyer1993, 494). Such theorists encompass scientists, policy analysts, consultants, and professionals (on the role of the latter, see also DiMaggio and Powell Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983, 152–53).

Particularly relevant for the emergence of frames based on institutional innovations is what Strang and Meyer (Reference Strang and Meyer1993) called the theorization of practices. This term denotes the process by which theoretical accounts ‘simplify and abstract their [institutional innovations’] properties and specify and explain the outcomes they produce’ (Strang and Meyer Reference Strang and Meyer1993, 497). This form of theorization facilitates perceiving and communicating about an institutional innovation and also explains why its adoption is likely to produce similar outcomes across seemingly diverse contexts. Moreover, theorization of practices involves specifying the theoretical link between the underlying cooperation problem and the institutional solution, and different theorists may shift the emphasis from one cooperation problem to another. When this occurs, it positions an institutional innovation as a suitable solution to a broader range of potential problems, making it more widely applicable. Whereas the innovator’s solution SI may initially be associated primarily with problem P1, theorization by different theorists may lead to associating this solution with another underlying problem P2.Footnote 6 Below, I show how the adoption of a common market in regional economic cooperation has over time become associated with different cooperation problems through processes of theorization, rendering an EU institutional innovation widely applicable to other contexts. How do such theorized institutional innovations, or frames, affect political decision-making?

How do frames affect political decision-making?

Frames affect political decision-making by helping policymakers to understand the underlying cooperation problem and to devise a ‘suitable’ solution. Frame-based decision-making works through analogical reasoning, which is a form of thinking in which novel situations are assimilated into existing problem–response schemas. As Vosniadou and Ortony (Reference Vosniadou and Ortony1989, 6) put it, analogical reasoning ‘involves the transfer of relational information from a domain that already exists in memory […] to the domain to be explained’ (see also Khong Reference Khong1992). When policymakers encounter a novel cooperation problem, they do not seek to understand the problem and devise solutions from scratch; instead, they draw on mentally accessible frames that help them deal with similar challenges (on the role of accessibility in judgment and decision-making, see Kahnemann Reference Kahneman2011). Social psychologists have long recognized that ‘objects and events in the phenomenal world are almost never approached as if they were sui generis configurations but rather are assimilated into pre-existing structures in the mind of the perceiver’ (Nisbett and Ross Reference Nisbett and Ross1980, 36; see also Zerubavel Reference Zerubavel1999, 24). Similarly, Strang and Meyer noted that an ‘individual or organization’s cognitive map identifies reference groups that bound social comparison processes’ (Reference Strang and Meyer1993, 491). I contend that when the cooperation problem an organization faces appears similar to the problem identified by a prominent frame, this frame is likely to guide decision-making.

Frames serve two key functions in the decision-making process. First, they provide a shared understanding of the underlying cooperation problem. Cooperation challenges are not obvious and cannot simply be derived from underlying fundamentals. In Blyth’s (Reference Blyth2003) apt formulation, ‘structures do not come with an instruction sheet’. Many ‘objective’ problems are not addressed because no agreement on a suitable course of action can be found. Sociologists have long recognized that problems are constructed through cognitive and societal processes (see, e.g., Cohen, March and Olsen Reference Cohen, March and Olsen1972; for an overview, see van Hulst and Yanow Reference van Hulst and Yanow2016). Similarly, constructivists suggest that successful bargaining requires ‘common knowledge concerning both the definition of the situation and an agreement about the underlying “rules of the game”’ (Risse Reference Risse2000, 2). Thus, frames render a given cooperation problem intelligible to policymakers by allowing them to understand it as an instance of a more general phenomenon, which in turn helps them to find agreement on the necessity of taking political action. This enabling function of frames is central to sociological work that emphasizes their potential for ‘consensus mobilization’ (Klandermans Reference Klandermans1984), and it is highlighted in recent work on international agreements, which argues that framing is a useful concept ‘to understand how such agreements become possible in the first place’ (Charnysh, Lloyd and Simmons Reference Charnysh, Lloyd and Simmons2015, 345). It is particularly relevant in the international context, where decision-making tends to take the form of formalized agreements that generally require consensus among actors operating in the decentralized setting of intergovernmental negotiations.

Second, frames affect political decision-making by linking problems to specific institutional solutions, thereby restricting the range of conceivable options that actors consider in response to the problem. As Zerubavel noted, ‘social situations are typically surrounded by mental fences which mark off only part of what is actually included in our perceptual field as relevant, thereby separating that which we are supposed to leave “in the background” and essentially ignore’ (Reference Zerubavel1999, 37). A frame links a specific understanding of a problem to certain solutions and not others, and thereby ‘convinces actors about the general contours of new arrangements’ (Fligstein and Mara-Drita Reference Fligstein and Mara-Drita1996, 3). As cognitive schemas, frames thus introduce bias into decision-making. Recent work on international institutions shows empirically that actors ‘do not do a full search and comparison of the whole range of alternatives’ (Jupille, Mattli and Snidal Reference Jupille, Mattli and Snidal2013, 34), but often restrict their choice range to variations on the frame’s prognostic element. In other words, frames anchor political decision-making, and thereby bias it.

Frame diffusion and convergence in institutional choice: under which conditions?

The above discussion suggests that frame-based decision-making, through its reliance on analogical reasoning, is likely to lead to convergence in institutional outcomes at the macro level. This phenomenon can be conceptualized as a form of diffusion – the third stylized explanation for institutional convergence outlined in the introduction. The diffusion literature’s distinct claim is that the institutional choices of some actors systematically shape those of other actors, such that institutional choice is ‘characterized by interdependent, but uncoordinated, decision-making’ across units of analysis (Elkins and Simmons Reference Elkins and Simmons2005, 38; see also Shipan and Volden Reference Shipan and Volden2008). This is also the key insight of Strang and Meyer (Reference Strang and Meyer1993), who linked theorization to the likelihood and speed of institutional convergence. From a diffusion perspective, then, frames originate in one regional organization and guide policymakers from collective perceptions of underlying cooperation problems to appropriate solutions in other regional organizations through analogical reasoning. Thus, frames can have international origins and spread across organizations.Footnote 7

This explanation is distinct from one that emphasizes similar yet independent reactions to similar structural conditions – the first stylized explanation for institutional convergence mentioned in the introduction. It may be objected that an explanation emphasizing frame diffusion becomes indistinguishable from an explanation focusing on similar reactions to similar problems because both explanations view institutional convergence as the result of the emergence of similar cooperation problems. In other words, do we need to emphasize cognitive problem–response schemas and their diffusion in order to understand why actors react similarly to similar structural problems? I would say yes, for two reasons. First, problems are never ‘objectively’ given and readily perceived similarly by all relevant actors. Although cooperation problems exist in the absence of frames, frames render ill-defined situations intelligible and thereby ‘actionable’ for policymakers (van Hulst and Yanow Reference van Hulst and Yanow2016, 97–98). Second, the ‘similar problems-similar responses–explanation’ does not expect similar problems to lead to similar solutions in structurally diverse contexts. Instead, it would expect the adopted solutions to reflect structural differences in context, even if they address similar problems. In other words, the ‘supply’ of institutional outcomes should differ in structurally diverse contexts even if common problems generate a similar demand because rational policymakers anticipate different institutional effects of similar institutions in different structural contexts. This should translate into differences in the adopted solutions. In contrast, an explanation emphasizing frame diffusion suggests that even policymakers in diverse structural settings adopt similar solutions in response to similarly perceived problems because frame-based decision-making abstracts from the specific context, thereby biasing institutional choice.

Even though the emergence of new frames is relatively rare, there is generally more than one frame available to affect decision-making. This observation cuts to the heart of institutional choice, which is the process by which governments select from among institutional alternatives in response to a new cooperation challenge (see Jupille, Mattli and Snidal Reference Jupille, Mattli and Snidal2013, 4). How do policymakers choose between frames?

Drawing on Strang and Meyer, I propose that theorization does not fully obliterate the ideational affinity between a specific frame and the originating organization, but broadens it. As a result, the frame becomes associated with a generic type of organization, rather than a single organization. Strang and Meyer refer to this form as the theorization of adopters, which establishes similarities between innovating organizations and potential adopters of a frame in such a way as to ‘define populations within which diffusion is imaginable and sensible’ (Strang and Meyer Reference Strang and Meyer1993, 495). This argument implies that frame diffusion, and resulting institutional convergence, should be observable only within specific groups of regional organizations, while institutional diversity may persist between them.Footnote 8 Importantly, such groups are not defined materially – for example by the nature and complementarity of their economies – but ideationally. Strang and Meyer refer to such groups as ‘social categories’ and suggest that ‘the cultural understanding that social entities belong to a common social category constructs a tie between them. […] We argue that where actors are seen as falling into the same social category, diffusion should be rapid’ (Reference Strang and Meyer1993, 490).Footnote 9 What are these categories in the realm of regional economic cooperation?

I suggest focusing on the purpose of an organization as the main determinant of social category in regional economic cooperation. The purpose of an organization is the basic goal, or ultimate objective, which it serves. From this perspective, two basic social categories can be distinguished: market-building and community-building organizations. In the former type, regional economic cooperation is seen as an end in itself. In this view, regional economic cooperation is useful because it helps policymakers to achieve the key economic objective of enhancing a country’s welfare by facilitating trade across national borders. This consideration is emphasized widely in the literature on preferential trade agreements (see, e.g., Mansfield and Solingen Reference Mansfield and Solingen2010). Community-building organizations, in contrast, view regional economic cooperation not as an end in itself but as a means towards a broader goal, namely that of building a regional community. The EU’s initial goal of ‘ever closer Union’ is an expression of this community building purpose, and so is the Economic Community of Western African State’s stipulation that ‘the ultimate objective of their efforts [is] the creation of a homogenous society, leading to the unity of the West African states’ (1975 ECOWAS Treaty, Preamble). Such organizations tend to be characterized by a broader policy scope in which economic cooperation is just one of many policy areas. These types of organizations often emerge in contexts where deep security dilemmas are present, or where communal foundations already exist, perhaps due to a common history as a federation (see Marks et al. Reference Marks, Lenz, Ceka and Burgoon2014).Footnote 10

This distinction implies that policymakers in regional organizations whose social purpose is to build a regional community are more likely to draw on the common market frame in the process of decision-making than organizations that are engaged in market building. In other words, policymakers’ collective self-understandings crucially shape their choice of frames, and thus their reaction to particular cooperation problems.Footnote 11 Cutting to the essence of frame-based decision-making, I suggest that policymakers in different types of organizations perceive, and thus react to, different cooperation problems in the first place, and they react to the same cooperation problem in different ways.Footnote 12 What are the cooperation problems that underlie frame-based decision-making in these two groups of organizations? This is the question we turn to now.

The common market frame and its alternative

The common market frame emerged out of Western Europe’s cooperation experience, and the underlying institutional innovation was subsequently theorized in different ways, gradually widening its potential appeal. Whereas the common market frame initially conceived a common market as an appropriate response to the security dilemma stemming from differences in power between neighboring states, it also became associated, over time, with the problem of under-development and economic dependence and with challenges of competitiveness in the international economy. The competing NAFTA frame engages a similar cooperation problem – challenges of international competitiveness – but proposes an alternative institutional solution: an FTA. Table 2 summarizes the content of the relevant frames.

Table 2 Content of relevant frames (date of emergence in brackets)

FTA=free trade agreement.

The ‘original’ common market frame is rooted in an institutional innovation in Western Europe after the Second World War that was developed by Jean Monnet, one of the founding architects of European integration. Attempting to avoid a resurgence of German hegemony in a situation in which ‘history offered no precedent’ (Jean Monnet, cited in Suganami Reference Suganami1989, 138), Monnet and others sought to bind Germany into an institutionalized process of economic cooperation that was to induce ‘ever closer Union’ among the participating countries (see Eilstrup-Sangiovanni and Verdier Reference Eilstrup-Sangiovanni and Verdier2005, 104–10). The first step in this approach was to establish joint control over the crucial war resources of coal and steel (European Coal and Steel Community), followed by the integration of nuclear energy (Euratom) and the establishment of a common market and customs union (European Economic Community). Suganami described the innovative character of this approach as follows: ‘reliance upon the domestic analogy is implicit not only in the ultimate ideal of the United States of Europe […] but also in the idea of creating an institutional framework by which various sectors of the member-states’ domestic economies are to be united to form a “common market”’ (Reference Suganami1989, 139). Thus, the European experience grounded not only the emergence of a common market frame, but also the ideational affinity between the common market frame and regional organizations purposed towards community building.

Shortly after policymakers began to implement this political proposal, it also started to be theorized in abstract terms. The main actors in the process were early neofunctionalist scholars such as Ernst Haas, and they engaged in both forms of theorization mentioned by Strang and Meyer. Haas (Reference Haas1958) theorized the practice of European integration as a generally applicable response to the security dilemmas between neighboring states with vastly different power. He abstracted the specific European problem–response sequence as a generalizable process of functional spillover between connected policy fields that would gradually evolve from functionally limited beginnings towards a more encompassing common market, thereby increasingly constraining the power of individual member states (Haas Reference Haas1958; see also Balassa Reference Balassa1961; Lindberg Reference Lindberg1963). As Rosamond noted, neofunctionalism constitutes ‘an attempt to theorize the strategies of the founding elites of post-war European unity’ (Reference Rosamond2000, 51). This clearly enhanced the appeal of the seemingly unique European experience for policymakers elsewhere that faced similar challenges, while directing attention away from other interpretations of the cooperation challenge and other conceivable responses. For example, weaker states can seek to secure peace by punishing a temporarily weakened hegemon, or they can balance against the hegemon with the help of powerful outsiders. If they choose to cooperate, they can envisage a shallower and functionally less inclusive economic agreement – an FTA in goods, for example – that can take different forms: a bilateral or a plurilateral agreement, or multilateral cooperation in the context of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (see Eilstrup-Sangiovanni and Verdier Reference Eilstrup-Sangiovanni and Verdier2005, 104–11). Overall, the common market frame was geographically more limited and functionally more inclusive than potential alternatives.

Moreover, neofunctionalists not only theorized the practice of economic cooperation itself but also identified, at least implicitly, the population of potential adopters. Haas (Reference Haas1958) theorized that functional spillover would lead to a gradual transfer of loyalties of all involved actors to the regional level. As he noted in his article International Integration: The European and the Universal Process, ‘We are interested in tracing progress toward a terminal condition called political community’ (Reference Haas1961, 366). This implied that the adoption of a common market would be useful specifically for those countries that wanted to construct a regional community (see also Lindberg Reference Lindberg1963). According to this view, economic cooperation did not constitute an end in itself, but served as a means towards that broader goal.

Thus, a common market frame started to develop by the late 1950s and early 1960s, but its wider applicability remained limited by the focus on security dilemmas between unequal neighbors. Its applicability grew when theorists and policymakers in Latin America and Africa re-directed the ‘original’ frame towards a somewhat different rationale in the 1960s and early 1970s, rendering it as an appropriate response to the problem of under-development and economic dependence. The practice of creating a common market was theorized as a tool to enhance regional self-reliance through the creation of larger and highly protected markets among developing countries that pursued import-substitution policies – an idea advanced specifically by the Economic Commission for Latin America and its Executive Secretary Raúl Prebisch (see, e.g., Prebisch Reference Prebisch1963). This ‘re-directed’ common market frame shifted the focus away from ‘the European concern with European integration as a means to avoid war towards an approach whereby regional economic cooperation/integration was considered a means for economic development’ (Söderbaum Reference Söderbaum2016, 24). This rendering excluded alternative solutions to the problem of under-development, such as more liberal economic policies that came to be adopted in later periods, and it is arguably an important reason why, in the 1960s and 1970s, policymakers ‘in all parts of the Third World flirted with regionalism on the European model’ (Mayall Reference Mayall1995, 184).

The common market frame underwent a further theorization of the practice in the 1980s in the wake of Europe’s 1992 program, which laid out a detailed plan for the completion of the common market. European policymakers justified the initiative as a ‘solution to the problem of Europe’s lack of competitiveness’ (Fligstein and Mara-Drita Reference Fligstein and Mara-Drita1996, 12). Economists associated with the program theorized a well-functioning common market more generally as an appropriate response to the challenge of a globalizing world economy and growing international competition (Padoa-Schioppa et al. Reference Padoa-Schioppa, Emerson, King, Milleron, Paelinck, Papademos, Pastor and Scharpf1987; Emerson et al. Reference Emerson, Aujean, Catinat, Goybet and Jacquemin1988). Thus, the ‘new’ frame re-directed the purpose of the common market from an inward-oriented solution to regional security dilemmas and under-development towards an outward-oriented solution to increasing international competition. Once again, common market building emphasized one set of solutions at the expense of alternatives, such as purely national strategies, or closer links with Japan, the emerging competitor (Sandholtz and Zysman Reference Sandholtz and Zysman1989, 106). It biased emphasis.

At around the same time, North American policymakers also reacted to an increasing sense that international competition was growing, but did so in a different way than their European counterparts. In 1988, they concluded the Canada–US Free Trade Agreement, which was extended to Mexico in 1992 and named NAFTA. Beyond these genuinely regional initiatives, US policymakers also advanced the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation and the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA). These initiatives were seen by the involved actors as ‘crucial to a more efficient, competitive, and export-oriented economy’ (Milner Reference Milner1995, 348), but policymakers responded to this challenge by designing a functionally more limited FTA that liberalized trade in individual sectors, especially goods and services (and some investment). Sparked by these institutional innovations of the architect and major supporter of the post-war multilateral trading system, policy analysts, often lodged in influential international organizations, quickly theorized this problem–response sequence. They portrayed the negotiation of FTAs below the multilateral level as an appropriate response to the challenge of increasing international competition (see APEC 1994), thereby giving rise to an alternative FTA frame. This frame has become most clearly theorized in the concept of ‘open regionalism,’ which portrays functionally limited regional economic cooperation as an appropriate response to the myriad challenges associated with globalization and defends the general compatibility of this approach with multilateral trade liberalization (for an overview, see Bergsten Reference Bergsten1997). However, the emergence of this frame has put purely multilateral strategies for dealing with heightened international competition on the defensive.

Observable implications

What type of empirical evidence would corroborate this argument about frame diffusion? Framing arguments, like other arguments about cognitive processes, are difficult to verify conclusively with observational data because they relate to mental processes of actors that are difficult to tap directly. Nevertheless, following many qualitative studies on frames and studies on cognitive heuristics, such arguments can be made plausible by tapping frame diffusion indirectly, through its observable implications. Even though not all implications are distinct from those suggested by alternative arguments, taken together they ‘form a “signature” that is quite unique’ (Beach and Pedersen Reference Beach and Pedersen2016, 18). Observable implications concern three dimensions of institutional choice.

1. Timing: Institutional choice tracks the perception of a cooperation problem that relevant frames theorize as requiring regional economic cooperation. This link to existing frames should be reflected in the verbal justifications of an initiative.

2. Process: The ensuing debate reflects a frame’s diagnostic and prognostic elements, and draws parallels with the organization from which it emerged. Policymakers quickly agree on the nature of the underlying cooperation problem, in line with the diagnostic element of the frame in question; alternative ways to understand the problem are not considered. On that basis, the range of potential institutional choices that is being considered is narrow; there is little controversy over the general direction of required institutional choice, which allows for relatively smooth decision-making. Epistemic networks linked to the originating organization and/or culturally legitimated theorists more generally are involved in institutional debate.

3. Outcome: The resulting institutional choice reflects the frame’s prognostic element, often worded in language very similar to that used in the originating organization. To outside observers, the decision might appear surprising in view of member states’ divergent structural positions.

Illustrative empirics: institutional choice and the diffusion of the common market frame

In this section, drawing on interviews, primary documents, and secondary sources, I seek to demonstrate the plausibility of the frame diffusion argument with reference to economic cooperation in ASEAN, the Southern Cone/Mercosur, and SADC. I focus primarily on those key institutional choices when the three regional organizations decided to move beyond a simple FTA to embrace a common market, in line with the main puzzle outlined before. Transformative choices involving the adoption of an FTA will be dealt with only briefly. In line with the theoretical argument, the narratives show that the adoption of the common market frame correlates temporally with (1) an explicit turn towards community building as a major purpose of the organization and (2) the emergence of cooperation problems that had been theorized by a given problem–response schema. More broadly, the narratives indicate how the influence of the common market frame in regional decision-making guided actors across different structural contexts towards the adoption of similar objectives in the process of regional economic cooperation.

However, an important caveat is that the empirics that follow are indicative, not definitive. A more rigorous test would not only have to present more thorough empirical evidence and engage more systematically with potential alternative explanations; it would also have to leverage more carefully cross-sectional variation in the types of organizations chosen. In the current empirics, all of the variance is temporal, and the analyzed organizations all eventually adopt a common market. I consider the three organizations in turn, starting with Mercosur and its predecessor in the Southern Cone.

Southern Cone/Mercosur

Origin and early steps in economic cooperation: Mercosur has its roots in the gradual rapprochement between Argentina and Brazil that started in the late 1970s during these countries’ transitions to democracy. In the early 1980s, cooperation was focused on security issues, involving the coordination of nuclear energy programs, and some limited commercial accords concerning double taxation and mutual investment. In 1986, the two governments concluded a program of cooperation that sought voluntary and gradual trade liberalization on a sectoral basis. This Economic Cooperation and Integration Program was modeled on the European Coal and Steel Community in an attempt to help Argentina and Brazil overcome their long-standing rivalries (Botto Reference Botto2009, 176). Thus, it was from the early days of cooperation in the Southern Cone that the original common market frame guided decision-making. Policymakers in Argentina and Brazil perceived their situation as akin to the security dilemma between France and Germany after the Second World War, which led them to adopt a similar strategy of cooperation that started with functional cooperation and was to gradually deepen over time (Oelsner and Vion Reference Oelsner and Vion2011). After only a few years of actual cooperation, policymakers repeatedly expressed their belief that ‘the achievement of the common market was a dream for both countries’ (cited in Gardini Reference Gardini2010, 82).Footnote 13

Soon thereafter, in November 1988, Argentina and Brazil signed the Treaty of Integration, Cooperation and Development, which aimed to create a free trade area within 10 years through the gradual removal of tariff and non-tariff barriers on goods and services. Even though it fell short of establishing a common market, the treaty explicitly laid the foundations for its adoption in the future. It mentions the creation of a ‘common market’ as a long-term ambition (Art. 5), and envisions the harmonization of a series of flanking policies such as agriculture and transport as well as the coordination of monetary, fiscal, and exchange rate policies (Arts. 3 and 4) and the gradual harmonization of policies ‘related to human resources’ (Art. 5). In fact, negotiation histories show that even a common external tariff was provided for in draft treaty texts, but later eliminated for practical reasons (Gardini Reference Gardini2010, 82).

Yet, the long-term ambition to create a common market only became a reality three years later with the foundation of Mercosur. How did this more ambitious form of regional economic cooperation become possible in such a short period of time?

Adoption of a common market: As noted, the original common market frame was widely held among policymakers in the Southern Cone, and it guided decision-making on several occasions throughout the 1980s. Policymakers in the region saw themselves as being involved in a process of community building, in which economic cooperation was not seen as an end in itself, but an important means towards overcoming the historical rivalry between Argentina and Brazil. Even policymakers who, during their time in office, primarily emphasized the market-building aspect of the relationship, such as Argentinean President Carlos Menem, perceived these advances in economic cooperation as an integral part of – as he himself termed it – a ‘community building process’ (Menem Reference Menem1996). Policymakers who were involved in the negotiation of Mercosur expressed similar convictions, such as former Argentinean policymaker Roberto Bouzas: ‘there was a predominant sense of identification with the EU “community” approach to economic integration, as opposed to the more “market-oriented” models of NAFTA and the FTAA’ (Reference Bouzas2003, 15–16). This statement is ‘smoking gun’-type evidence to suggest that certain types of frames have affinities with specific organizational purposes, in this case the affinity between the common market frame and regional organizations directed at community building. In fact, the Treaty of Asunción, which founded Mercosur in 1991, codified this community building purpose by ‘reaffirming their political will to lay the bases for ever closer Union between their peoples’ (Preamble). So what is the evidence that the common market frame actually guided policymakers during the negotiations?

As noted, the original common market frame had been present throughout the 1980s, but it was increasingly dominated by the new common market frame in the run-up to Mercosur. At that point, the economic cooperation processes in Europe and North America had started to consolidate, and they instilled a sensibility among policymakers in the region that international competition was heightening. Early studies warned of the potential for trade and investment diversion away from Latin America due to those developments (see, e.g., Hufbauer Reference Hufbauer1990), and in June of 1990 Mexican President Salinas formally requested to join the Canada–US Free Trade Agreement. Strikingly, it was in the following month, in July 1990, that Menem and Collor signed the Act of Buenos Aires, envisaging the creation of a common market. Thus, the timing of renewed attention to institutional choice in the Southern Cone closely tracks decisions by important trade and investment partners in Europe and North America that epitomized heightened international competition.

The process of subsequent debate and negotiation reflected the new common market frame and displayed analogical reasoning especially with the EU’s recent experience. To many decision-makers in the region, the EU with its 1992 project appeared ‘stronger and more radiant than ever, and much less dependent on the outside world’ (Vasconcelos Reference Vasconcelos2007, 167). Relatedly, justifications for the initiative emulated much of the rhetoric of the EU’s 1992 program. Argentinean President Menem declared that Mercosur allows ‘the possibility of uniting [its member countries’ efforts] to compete in a new global market in which the strength of the trade bloc has become more important than that of individual countries’ (cited in Manzetti Reference Manzetti1993, 110–11). Similarly, other policymakers viewed ambitious regional market building as ‘an assertive instrument of competitiveness’ (cited in Gardini Reference Gardini2010, 87). Interviews also indicate that frame-based decision-making guided negotiations, and ultimately facilitated consensus formation. Former Brazilian Foreign Minister Luiz Felipe Lampreia recalls of the negotiations, for example, that ‘reference to the EU was constant’ (interview with the author), suggesting that it provided the relevant focal point in the negotiations that facilitated consensus formation. In line with a frame diffusion argument, interviews also indicate that there was no debate about potential alternative institutional choices, and also little controversy over the general direction of envisaged institutional choice. One policymaker recalled: ‘If we go to the documents or to the minutes of the discussions between Brazil and Argentina, nowhere can you find a very detailed study concerning the technicalities of a customs union or a common market. You just have political enthusiasm’ (interview with Brazilian negotiator; see also Botto Reference Botto2009, 176). Another interviewee mentioned, along similar lines: ‘We wanted to set the four countries on a path of regional integration, but we had little experience in how to do that … We had good intentions, but lacked the knowledge on many specific issues’ (interview with Argentinean negotiator).

Thus, the final outcome of this process was the adoption of a common market, including a customs union. Treaty language in the Mercosur agreement draws heavily on that used in Europe. It formulates the ambition to ensure the ‘free circulation of goods, services and factors of production’ by pursuing the ‘elimination of customs rights and non-tariff barriers,’ the establishment of a common external tariff and the ‘adoption of a common commercial policy,’ as well as the ‘coordination of macroeconomic and sectoral policies’ (Art. 1). Even more specifically, it outlines a replication of the ‘classical’ European integration experience of economic integration as a step-wise process evolving from an FTA through the establishment of a customs union towards a common market, as economists such as Bela Balassa and others had theorized it. In retrospect, some policymakers, such as former Brazilian Foreign Minister Lampreia, mentioned that ‘it was a mistake to copy the EU integration model’ (interview with the author).

In sum, due to their community building ambition and thus their reliance on the common market frame, policymakers in Mercosur addressed challenges of international competitiveness with the adoption of a common market and customs union. Faced with the same cooperation challenge, policymakers in ASEAN initially reacted differently because they were guided by a different frame – a situation that changed when they endorsed community building as a central purpose of the organization, as we will see in the next section.

Association of Southeast Asian Nations

Origin and early steps in economic cooperation: ASEAN is a regional organization in Southeast Asia that was founded in 1967 by five states (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand) in an attempt to withstand communist subversion, both internally and from the outside, during the Cold War. ASEAN’s early evolution shares some similarities with cooperation in the Southern Cone in that cooperation was initially restricted to functional coordination in selected policy areas and eventually moved towards an FTA with the signing of the ASEAN Free Trade Agreement (AFTA) in January 1992. However, this process was much slower than in the Southern Cone; it stretched out over 25 years rather than a decade (for a good overview, see Ravenhill Reference Ravenhill1995). The impetus for deepening economic cooperation in the early 1990s was similar to the Mercosur case, and it occurred as policymakers in the region came to view advances in economic cooperation in Europe and North America as an indication of heightened international competition that required political action (Mattli Reference Mattli1999). Thus, much of the justification for the AFTA initiative revolved around the need to enhance ASEAN’s competitiveness (see, e.g., ASEAN Summit 1992, 27). Unlike Mercosur, however, the AFTA decision was largely guided by the FTA frame that conceived of an FTA as an appropriate response to this challenge (see Naya and Plummer Reference Naya and Plummer1997).

This difference can be explained by the different purposes pursued by these two organizations at the time. In Mercosur, governments agreed that enhanced economic cooperation formed part of a larger community building process, and was thus not seen purely in functional terms, but this was not the case in ASEAN. For most governments in the early 1990s, market building was seen as an end in itself within the context of heightened international competition, akin to the situation in NAFTA. Even though the organization reacted to these external challenges, it remained a limited and largely functionally oriented ‘neighborhood watch group’ (Khoo How San 2000). The most distinctive empirical expression of this difference is the fact that, whereas in Mercosur governments regularly referred to the EU in explaining their goals, such references were not only largely absent in ASEAN, but were actually seen as being inappropriate among most ASEAN governments. Despite some exceptions,Footnote 14 most governments agreed that any reference to the EU was to be avoided because, as former Singaporean Senior Minister Rajaratnam noted, ‘the European Community was never made by ASEAN’s architects the model for ASEAN regionalism’ (Rieger Reference Rieger1991, 161).

Adoption of a common market: However, the tide started turning in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Two developments coincided around this time, which made the adoption of a common market possible.

The first one was a more explicit endorsement of community building as a central purpose of the organization. The reasons for this shift in purpose were manifold, including the fallout from the 1997/98 Asian financial crisis, which shattered ASEAN’s credibility as a regional leader and an economic regime. In its wake, important inside and outside actors discredited ASEAN’s self-understanding for being ‘too state-centric (not sufficiently inclusive of societal voices and interests)’ (Ba Reference Ba2013, 140). ASEAN leaders quickly realized that, as Secretary-General Severino (Reference Severino2006, 37) noted, they had to change the ASEAN in a manner that responded ‘to the needs of the ASEAN’s people of today’ – a goal that a community building purpose was more likely to serve. Another reason was the enlargement of ASEAN to other Southeast Asian states (Vietnam joined in 1995, Laos and Myanmar in 1997 and Cambodia in 1999), which increased the political and economic diversity in the organization and accepted a major former enemy – Vietnam – in its midst. Thus, more cohesion was required to guarantee ASEAN’s continued functioning, and the enlargement rendered parallels with the European project more compelling. For all of these reasons, policymakers re-directed the cooperation process more explicitly towards community building. The idea was first developed in the ASEAN Vision 2020, adopted by the Heads of State in December 1997, which formulated the vision of ‘a community of caring societies,’ and formalized in 2008 in the ASEAN Charter, which spoke of the goal to create an ASEAN Community.

The second major development was the perception that new competitive challenges required political action. The timing of the new initiative closely tracks the realization, in the early 2000s, that the growing economic strength of China and India required a joint response. As former Secretary-General Ong Keng Yong noted, ‘In the early 2000s, we realized that China and India were growing rapidly. In 2000/01, China attracted more than half of the foreign direct investment to East Asia. We realized that individual countries cannot compete with these “economic giants”’ (interview with the author). Thus, these competitors’ economic growth and growing international assertiveness was increasingly seen as a threat to the region’s countries in terms of their attractiveness for foreign direct investment.

What is striking about the situation of ASEAN in the early years of the new millennium is that policymakers perceived a problem similar to the one in the early 1990s – challenges of international competitiveness – but adopted a different institutional solution in response. A plausible explanation for this difference emphasizes frame-based decision-making in a context in which the main purpose of the organization had evolved.

Empirical evidence for this claim refers primarily to the process by which the common market came to be adopted. For one, reference to the EU not only became more widespread, but also appears to have been more acceptable. As early as 1997, influential actors such as Malaysian President Mahathir called for a ‘long-term vision’ of ASEAN and suggested setting ‘our sights to be a single market and an economic union à la the EU’ (Manila Standard, 16 October 1997). In 2001, the economic ministers commissioned an expert study to identify ways to regain ASEAN’s competitiveness (ASEAN Economic Ministers 2001, section 12; 2002, section 8, respectively). Conducted by a team of European consultants from McKinsey, the study recommended a ‘step-change’ in integration (Schwarz and Villinger Reference Schwarz and Villinger2004). According to Ong Keng Yong, the study drew parallels with other regional integration experiences, especially in Europe and also in North America, to argue that deeper economic integration provided an appropriate response to international challenges of competitiveness (interview with the author). The secretariat and individual member states also conducted studies during this period that diverged in the specific recommendations; however, according to an Indonesian policymaker, ‘there was never any disagreement over the general direction of the policy change that was required’ (interview with the author). A central reason for this widespread consensus was that occasional references to the North American experience appeared out of place because, as an influential Indonesian policy advisor noted, ‘NAFTA is a narrow … integration project and [it] is also not about “community building”’ (Soesastro Reference Soesastro2008, 49, emphasis added). Therefore, the frame that was perceived as being most compatible with the idea of community building appeared like an ‘obvious’ guide.

At the Summit in 2002, Singaporean Prime Minister Chok Tong Goh (Reference Goh2002) captured the forming consensus that the ‘general way forward’ lay in ‘faster and deeper integration,’ and he suggested the formation of an ASEAN Economic Community, ‘not unlike the European Economic Community of the 1950s.’ It is striking how policymakers who had previously rejected any comparisons with the EU, including those from Singapore, suddenly endorsed them in public. For example, high-ranking diplomats noted at an expert roundtable in Berlin in 2012 that EU integration was ‘inspiring ASEAN’ (BMBF 2012).

The eventual outcome of this process was the Bali Concord II, adopted in October 2003, which formulated the ambition to establish an ASEAN Economic Community as ‘the realisation of the end-goal of economic integration as outlined in the ASEAN Vision 2020’ aimed at establishing ASEAN as a ‘single market and production base’ (ASEAN Summit 2003, section B1). The High Level Task Force on economic integration, whose recommendations were attached to the document, described this goal as involving the ‘free flow of goods, services, investment, and skilled labor, and freer flow of capital.’ This recommendation became official policy in the Vientiane Action Program that was adopted a year later and it has sparked a flurry of activity in terms of deepening economic cooperation since then.Footnote 15

Southern African Development Community

Origin and early steps in economic cooperation: In 1981, nine so-called Frontline States created the Southern African Development Cooperation Conference, the direct predecessor to SADC. With the support of international donors, they sought to coordinate national development plans across a range of functional sectors in an attempt to lessen dependence on South Africa’s Apartheid regime (Anglin Reference Anglin1983, 700–08). Akin to both the Southern Cone countries and ASEAN, economic cooperation initially played a marginal role and remained highly circumscribed throughout the 1980s (for an overview, see Lee Reference Lee2003, Ch. 3). Thus, for the first decade of its existence, the organization followed the pragmatic approach to regional cooperation advocated by its founding fathers, who announced that the ‘basis of our co-operation [must be] built on concrete projects and specific programmes rather than grandiose schemes …’ (SADCC 1980, 19).

Adoption of a common market: Policymakers abandoned this founding ‘ethos’ in the early 1990s by adopting the ‘grandiose scheme’ of a common market. Similar to the situation in ASEAN, two developments coincided around this time, which made movement towards a common market possible. The first development was a shift in the purpose of the organization towards an explicit endorsement of community building. There are several reasons for this change. One is the end of Apartheid in South Africa, which appeared imminent at the time and triggered a fundamental rethinking of the raison d’être of the organization. Suddenly, even the eventual accession of South Africa looked like a possibility (see Lee Reference Lee2003, 46–47). Another reason is the end of the Cold War and the new demands that were being placed on organizations around the world to become more participatory and inclusive; that is, democratic – a goal that a communityoriented purpose was more likely to facilitate. Moreover, the 1991 Abuja Treaty under the umbrella of the Organization of African Unity sought to establish an African Economic Community through the creation of sub-regional economic cooperation schemes that served as its central pillars. SADC(C) was designated as one of those pillars. The new purpose was made explicit in the transformation of the organization from the Southern African Development Coordination Conference to the Development Community, which seeks inter alia to ‘strengthen and consolidate the long-standing historical, social and cultural affinities and links among the people of the Region’ (Art. 5.1.h, SADC Treaty).

As in the other regions, the timing of institutional choice tracks the perception of enhanced international competitiveness that was crystallized in the formation of regional blocs in Europe and North America. There are plenty of statements by important policymakers establishing this link. For example, Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe noted at the 1989 Summit: ‘the 1990s also offer new challenges as other sub-regions … move closer together in their integrative efforts, for example, the European single market by 1992, and the US-Canada Free Trade Agreement’ (SADCC Summit Record, August 1989, 21). Thus, cognitive frames imbue the new challenge with meaning and guide policymakers towards appropriate solutions. The analogical reasoning that undergirds frame-based decision-making is nicely reflected in a statement by Botswana’s President Quett Masire, which linked Europe’s challenges in relation to competitiveness, addressed by the Single European Act, to the situation in Southern Africa: ‘We understand that the single European Act of 1987 will come into effect soon … If the Europeans need this kind of economic cooperation, we must need it even more’ (SADCC Summit Record, July 1988, 33).

The ensuing process of debate quickly linked competitive challenges to enhanced regional economic cooperation. As a secretariat document in 1991 flatly noted: ‘In the face of the region’s realities, and the current international tendencies toward the establishment of economic blocks, the region must accept to transform itself into an economic block similar to the proposed North American free trade zone or the European Economic Community’ (SADCC Secretariat 1991, 361). Empirical research on the decision-making process suggests that there was no debate regarding the benefits and drawbacks of different institutional choices: ‘policymakers felt that steps towards regional economic integration were necessary […] in view of the decisive moves towards regionalism in other parts of the world’ (Lenz Reference Lenz2012, 162–63). Without any serious assessment, the 1991 Council concluded that the new framework for regional integration must provide ‘for crossborder investment, trade and labor and capital flow across national boundaries’ (SADCC Council of Ministers 1991, 16), and Zimbabwean President Mugabe spoke at the Summit of the ‘facilitation of movement of peoples, goods and services’ and ‘greater cooperation in fiscal and monetary affairs’ (SADCC Summit 1991, 53).