Article contents

Extract

Critics show more toleration than enthusiasm for Marlowe as a dramatic artist. They praise his thought, his poetry, his psychology, but they offer excuses for his stagecraft. This is a pity, for there is no need to excuse it. Marlowe handles his medium with imagination and subtlety.

The root of the difficulty lies in mistaking a drama of spectacle for a drama of character. Marlowe was writing in a period of transition, when an abstract theatre was fast becoming a narrative one, and the development entailed an important shift of emphasis. Narrative throws stress on the characters of men and the motives that lead to the actions portrayed, while the abstract world of the morality play uses the stage action as a projection of an inward and spiritual action of the soul. A drama in which action is image was changing to a drama in which action is fact.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

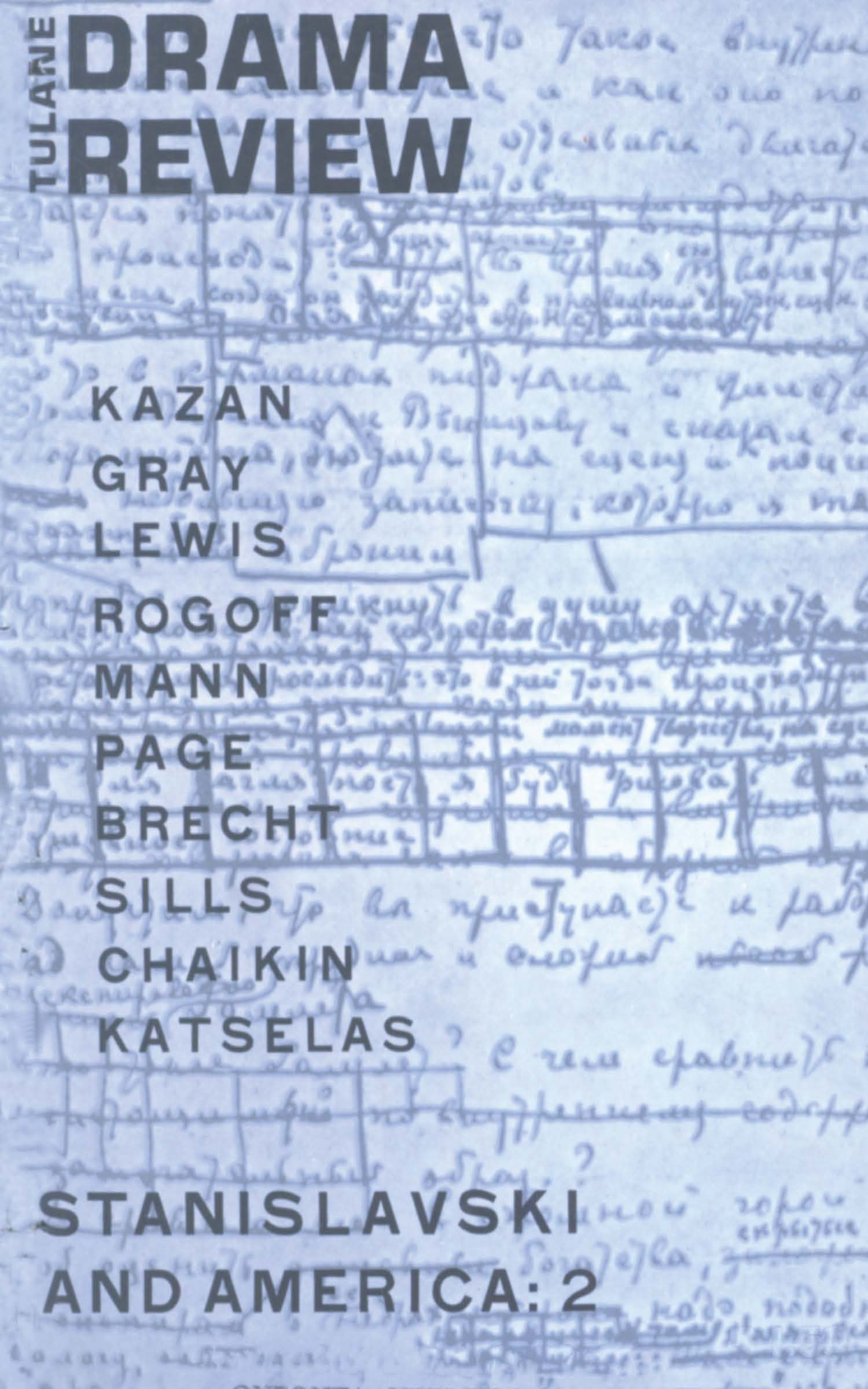

- Copyright © 1964 The Tulane Drama Review

References

1 Richard Willis, Mount Tabor. Quoted by J. P. Collier, History of English Dramatic Poetry.

2 Bevington, D. M., From Mankind to Marlowe (Harvard, 1962).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

3 I take an “emblem” to be a symbol of a specifically visual kind. It communicates its meaning through the eyes.

4 2T, I, ii.

5 Craik, T. W., The Tudor Interlude (Leicester, 1962).Google Scholar

6 William Wager, Enough is as Good as a Feast.

7 The Seven Deadly Sins. Painted table top. Prado, Madrid.

8 A similar effect is created at the end of IT (V, ii), with the enthronement of Zenocrate over the bodies of the slaughtered kings; also at the end of Edward II, where the funeral procession of the king is preceded by a guard bearing the head of Mortimer, and followed by young Edward.

9 Craik, , op. cit., p. 59Google Scholar. Gaveston also carries several traits of the morality vice (Bevington, op. cit.).

10 Many modern playwrights, Ionesco being the most obvious example, are turning from this tradition to the older methods of dramatic economy discussed here. [Artaud was perhaps the first modern theorist to discuss emblematic theatre.—Ed.]

11 Freeman, Rosemary, English Emblem Books (1948).Google Scholar

12 For a discussion of color symbolism, see Linthicum, M. Channing, Costume in the Drama of Shakespeare and His Contemporaries (1936).Google Scholar

13 Gardner, Helen, in her article on 2T (MLR: XXXVII, 1942), argues that frustration is the theme of the play.Google Scholar

14 In the last act, his second battle with the invisible Death finds release in a real fight.

- 2

- Cited by