Introduction

In early 2021, just as they were coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic, countries in Southern Europe (SE) were faced with a new shock to their economies: a slow, but constant increase in prices. As result of bottlenecks in global supply chains, and tensions in international gas and oil prices resulting from the Russian invasion of Ukraine (Uxó, Reference Uxó2022), these inflationary pressures have deepened throughout 2022. This article aims to map the social policy responses to the cost-of-living Crisis in Southern Europe (SE), and to identify areas of convergence/divergence in the way these countries have responded to this crisis.

There are important reasons for looking at this specific topic. First, it’s important because these countries constitute a very particular model of social protection (see Ferrera, Reference Ferrera1996; Saraceno, Reference Saraceno1997; Papadopoulos and Roumpakis, Reference Papadopoulos, Roumpakis, Ellison and Haux2020 and Ferrera, Reference Ferrera, Béland, Leibfried, Morgan, Obinger and Pierson2021), characterised by a peculiar combination of Bismarkian schemes of income replacement, with a more or less universal model of healthcare provision; by a dualised model of labour market protection; by the relative meagreness of welfare payments; by the (comparatively) scarce provision of welfare services; by the subsidiary role of the state with regards families in the provision of economic security – and by the prevalence of extensive levels of clientelism. Second, as we depict in more detail (see section three), examination is important because these economies were among the most affected by the pandemic (see Moreira et al ., Reference Moreira, Léon, Coda Moscarola and Roumpakis2021) – which obviously raises questions about their ability to respond to the current crisis.

More precisely, the article looks at measures introduced in Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain between January 2021 and December 2022. This covers traditional social policy measures (introducing new benefits, increasing benefits, temporary tax reliefs, etc.) as well as measures that, whilst not within the realm of the welfare-state, are used to pursue social policy ends – ‘social policy by other means’ (Béland, Reference Béland2019). Measures targeted at firms or specific economic sectors are excluded.

The article is structured as follows. Section two describes changes in the level and composition of inflation in SE, during the period under analysis. Section three details the measures introduced during this period in Greece (GR), Italy (IT), Portugal (PT), and Spain (ES). Section four tries to identify key similarities and differences in the way SE nations have responded to the cost-of-living crisis. In doing this, we also examine the evidence on the redistributive effect of those measures. Section five summarises the key findings of the article and proposes avenues for future research on this topic.

The rise in prices in Southern Europe

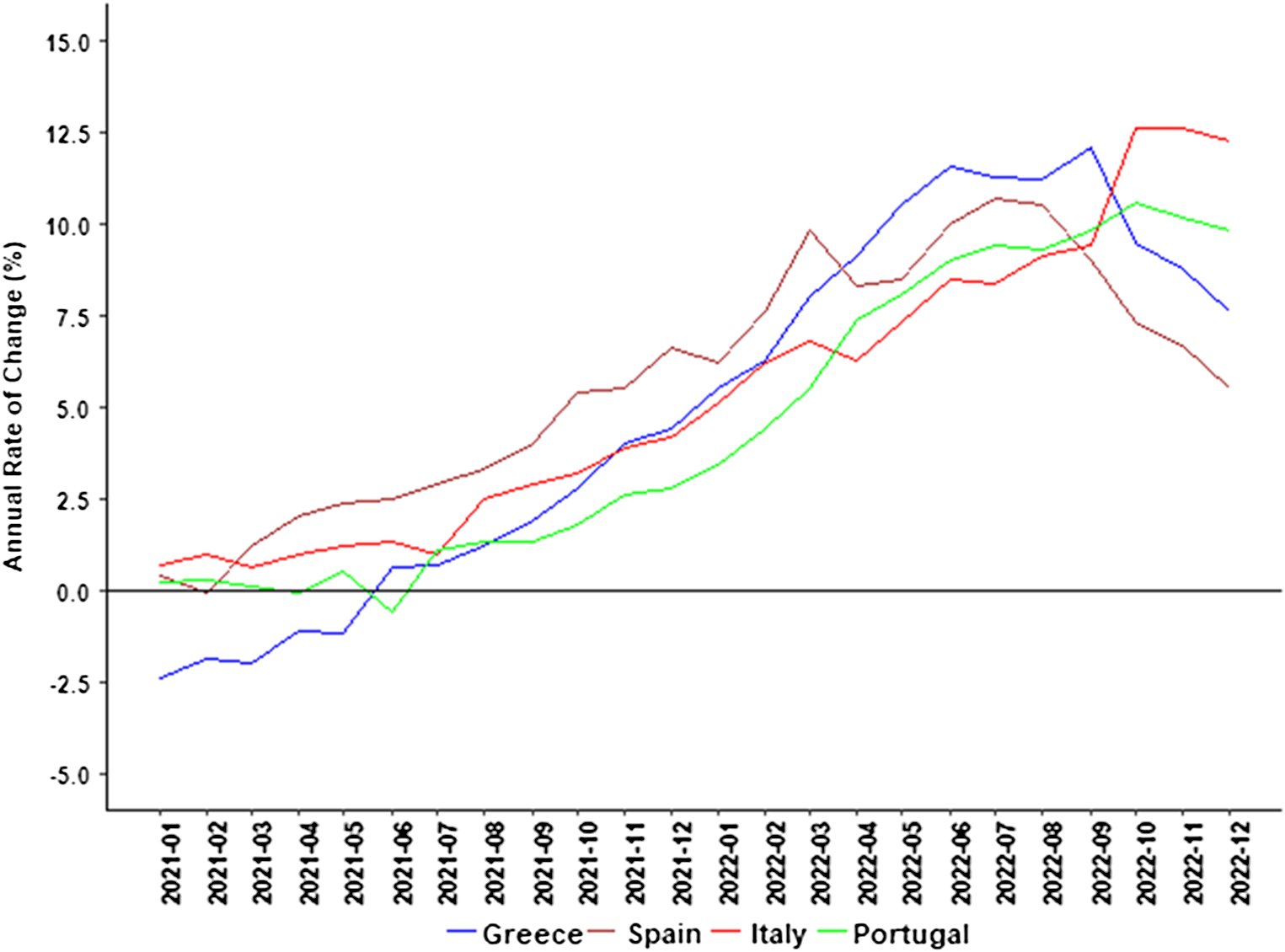

As can be seen in Fig. 1, the increase in prices in SE was already visible in early 2021, as the post-pandemic period started. This was particularly so in Spain, which experienced slightly higher levels of inflation than its SE neighbours through that year. However, the rise in prices has steepened following the breakout of the war in Ukraine. This was particularly so in Portugal and Greece where, between January and September 2022, monthly inflation rose from 3.4 per cent to 9.8 per cent, and from 5.5 per cent to 12.1 per cent, respectively.

Figure 1. Variation in the harmonized index of consumer prices (all items)a, 2021–2022.

Notes: aCompared with the same period in the previous year; Source: Eurostat (2023a)

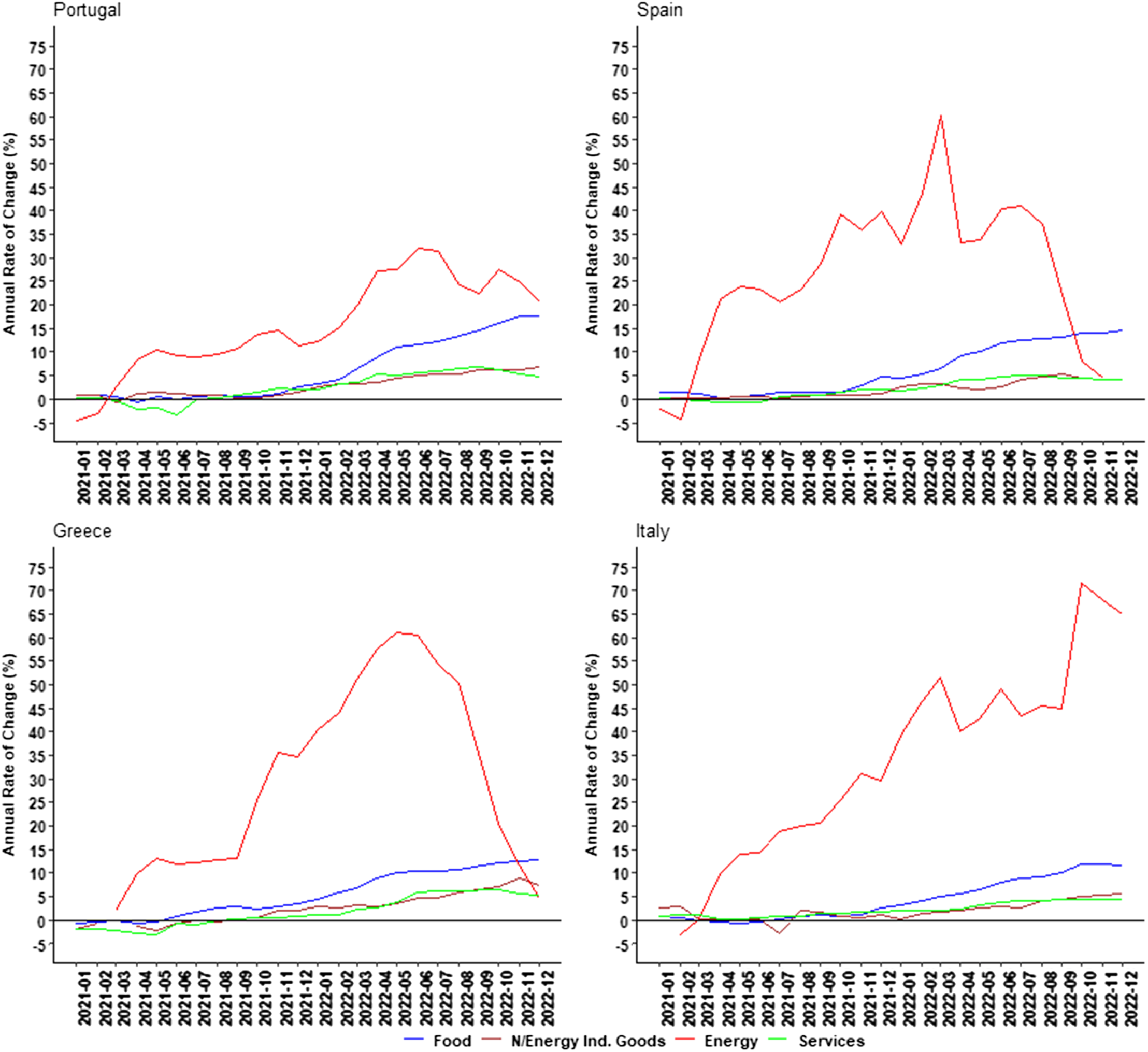

These price dynamics reflect, among other factors, important differences in the composition of inflation in SE countries. As can be seen in Fig. 2, most of the increase in inflation reflects changes in the relative prices of energy and, to a lesser degree, in the relative price of food. In fact, we can identify two very distinct types of inflationary processes within SE. In Spain, Italy, and Greece, the increase in prices is mostly driven by the changes in relative prices of energy. In Portugal, in contrast, increases in the relative prices of food (including tobacco and alcohol) play a much more significant role. Nevertheless, the increase in food prices, appears as largely persistent across SE countries since the summer of 2022 onwards.

Figure 2. Variation in the harmonized index of consumer prices (main components)a, 2021–2022.

Notes: aCompared with the same period in the previous year; Source: Eurostat (2023a)

Social policy responses to inflation in Southern Europe

The rise in inflation in SE takes place against a very specific economic and institutional context. As mentioned earlier, it occurs just as SE nations were coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic. Interestingly, these countries were not only among the most affected nations by the (economic) impact of the pandemic in Europe (see Moreira et al., Reference Moreira, Léon, Coda Moscarola and Roumpakis2021), but they were also among those that took longest to recover from the impact of the pandemic shock (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Variation in quarterly GDP, at market prices, Q1-2019 to Q4-2022 (anchored).

Source: Eurostat (2023b)

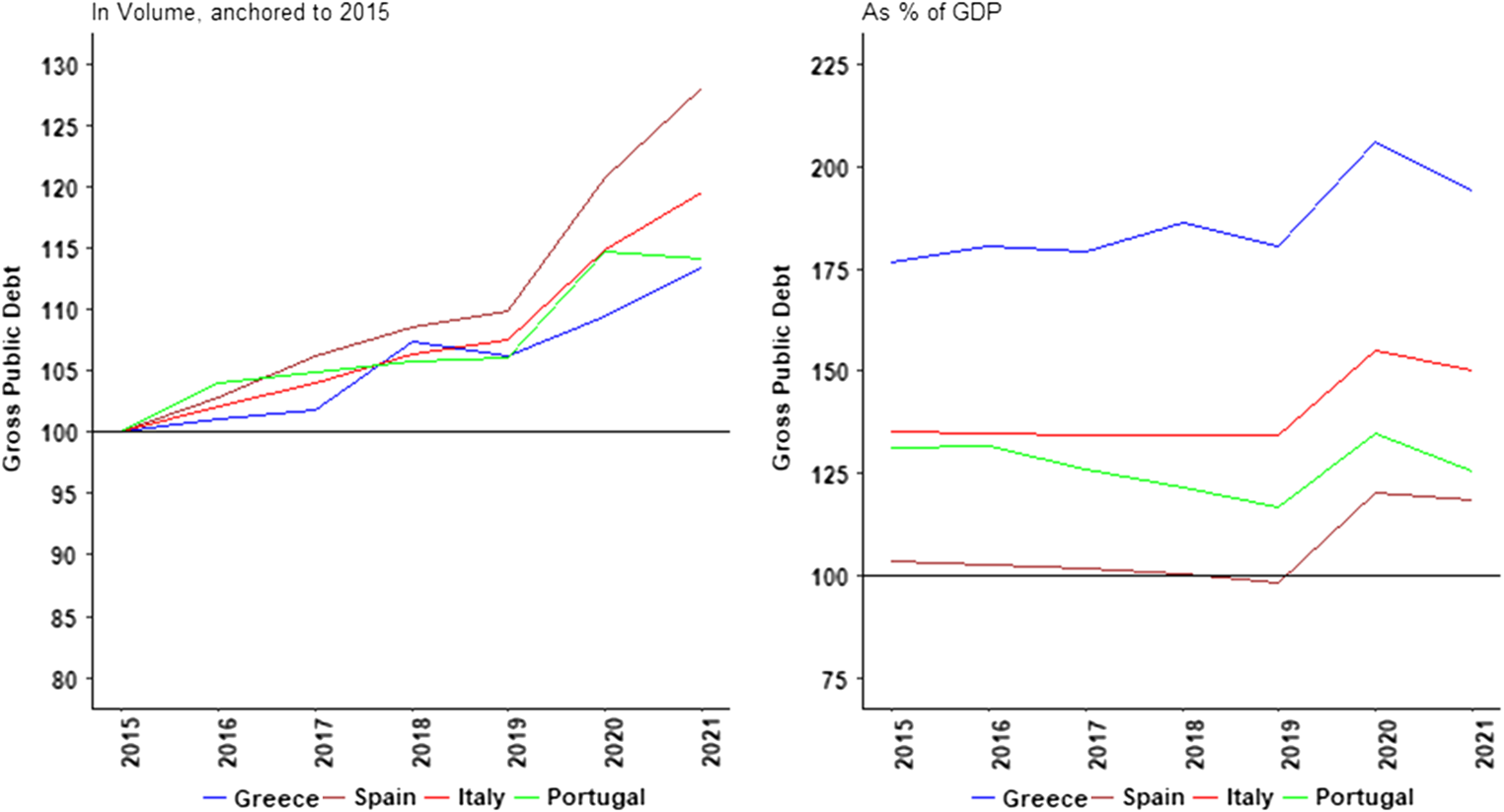

Also, as a result of the necessary response to the COVID-19 crisis (see Moreira et al., Reference Moreira, Léon, Coda Moscarola and Roumpakis2021), SE nations saw their public debt rise substantially, to the point that, by the beginning of 2021, both in volume and as a per cent of gross domestic product (GDP), public debt in these countries was significantly higher than at the end of the Euro-Crisis (see Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Variation in gross public debt, in volume and as percentage GDP, 2015–2021.

Source: Eurostat (2023c)

At an institutional level, this inflationary crisis clashes against a set of long-standing rules/institutions that regulate the adjustment of benefits, wages, and even tax rules (see Immervoll, Reference Immervoll2005) to changes in prices. The use of indexation mechanisms has been most generally adopted in relation to pensions. Thus, all SE nations have established mechanisms to secure the regular adjustment of pensions to changes in prices (see Annex I). However, the weight given to changes in prices in the uprating of benefits varies – with both Portugal and Greece also considering changes in the GDP as a determining factor for the indexation of pensions. In all four countries, the indexation rules are designed to sustain the purchasing power of lower pensions. There is, however, significant variation in how other types of benefits are indexed. In Portugal and Spain, minimum income benefits are subject to formal indexation rules. This is not the case in Italy and Greece, however. In most countries in SE – apart from Italy, where benefits are automatically adjusted to variations in prices – family benefits are not automatically updated with inflation, or any other criteria.

In the following sections, we describe the policy measures undertaken in SE until December 2022.

Greece

The response to the cost-of-living crisis in Greece was mainly shaped by a combination of the recovering fiscal position of the country and the elections taking place in 2023. The governing New Democracy party was elected in July 2019. At the time Greece had achieved – under left-wing SYRIZA rule – two consecutive years of economic growth (2017–2018), and by 2019 general government debt started to fall. The breakout of the pandemic put Greece in the eye of the storm again (Moreira et al., Reference Moreira, Léon, Coda Moscarola and Roumpakis2021), but thanks to the buoyant tourist season and increases in the private consumption of goods and services (European Commission, 2022), Greece experienced the strongest economic rebound in SE (see Fig. 3). Building, on this economic performance, and with elections looming, New Democracy had important incentives to pursue a strong response to the cost-of-living crisis.

Most of these interventions have focused on subsiding energy costs. The first set of measures adopted in September 2021Footnote 1 aimed to support households in their primary residence for consumption of electricity up to 300 kilowatt-hour (KWh) with a €30 subsidy per Megawatt-hour (MWh) (€0.003 per KWh, €99 per month). The subsidy has been constantly revised in terms of its generosity and coverage with the Greek government subsidising all consumption (no cap) at the 639€ per MWh (€0.6390.639 per KWh) for primary and secondary residences between July and September 2022. On top of these subsidies, the public electricity and gas suppliers offered discounted pricing to low voltage households, farmers, and professionals. There were also incentives to reduce energy consumption, such as the suspension of Value Added Tax (VAT) on new buildings and reparations, and subsidies for the installation of photovoltaic panels.

The Greek government also legislated an income subsidy, first for heating fuel costs paid to households on income and wealth criteria. In March 2022, a subsidy for petrol and diesel costs, ranging from €45 to €100, was awarded to all taxpayers residing in Greece earning up to €30,000 (single) or €45,000 (for a family with four children). A one-off payment was also offered in April 2021 to all low-income households and pensioners, as well as beneficiaries of disability allowances.Footnote 2 The one-off payment was repeated in December 2022. Additionally, in July 2022, the government introduced an extraordinary financial aid to cover part of the increase in the cost of electricity consumption for domestic consumers. The so-called Power Pass provided cash rebates ranging from €18 to €600 for bills issued between December first, 2021 and thirty-first of May, 2022 and covered 60 per cent of the surplus charges on bills from sharply higher energy prices, minus the state subsidies and any discounts given by the providers. In February 2023, the government issued the Market Pass targeting low and middle-income groups. This new measure offers a small contribution towards the cost of food items set at €22, with an additional top up for each additional household member (up to €100) for six months (until July 2023).

The Greek government also increased the minimum wage in May 2022 from €663 to €713 and with elections looming, the government aiming to restore the minimum wage to pre- austerity levels (€750) in April 2023. In January 2023, the government legislatedFootnote 3 a 7.75 per cent increase in pension benefits for 80 per cent of the pensioner population, with the rest of the pensioners either receiving a lower increase or nothing at all. For those who did not receive the full 7.75 per cent increase the government announced in February 2023 a one-off payment between €200 and €300 with the total cost of this payment reaching €280m. Additionally, the government abolished the social security solidarity contribution tax introduced in 2015. It is also legislated a permanent 3 percentage points reduction of the insurance contribution rate of private sector employees. Finally, the government also extended the reduced VAT rates on transport, restaurants, gyms, and entertainment venues until June 2023.

Italy

Responses to the increase in the cost-of- living in Italy must be understood by reference to three orders of factors: the country’s macroeconomic and fiscal position after the pandemic (see Figs. 3 and 4); the changes in the Italian political landscape – namely the nomination by the President of the Republic of a technocratic government led by Mario Draghi – which will be in office for most of the cost-of-living crisis; and crucially, the significant dependence of the Italian economy on Russian gas supplies.Footnote 4

Italian authorities introduced several measures to reduce the impact of the increase of international energy prices on Italian families. In July 2021, the government reduced the charges on electricity and (later in September 2021) on gas bills.Footnote 5 It also approved a reduction in VAT on natural gas from 10 per cent to 5 per centFootnote 6 and, from March 2022, a reduction in excise tax rates on fuels of about €0.1 per litre for liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) and €0.3 per litre for gasoline and diesel – that remained in place until November 2022.Footnote 7 In September 2021, the Italian government introduced a rebate (Bonus Sociale Luce e Gas) on energy bills targeted at low-income familiesFootnote 8 or with members in poor health. This has later been expanded/improvedFootnote 9 . In August 2022, the government introduced legislation banning energy providers from unilaterally increasing prices until April 2023.Footnote 10 There were also measures to reduce energy consumption. In May 2022, the government introduced a €60 voucher (Bonus Trasporti), for the purchase of monthly/season passes to public transports, targeted at individuals with yearly income up to €35,000.Footnote 11

One-off measures were taken to compensate families with the increase in prices. In December 2021, the government decided to cut the social security contribution rate for workers with an income below €35,000 by 0.8 percentage points from January to December 2022.Footnote 12 Later on, in July 2022, this cut was increased to 2 percentage points.Footnote 13 In addition, a €200 one-off payment (Bonus 200 euro) was granted to persons with yearly incomes up to €35,000 – including dependent workers, domestic workers, pensioners, self-employed, and minimum income or unemployment schemes’ beneficiaries.Footnote 14 A second, €150, one-off payment was later introduced for workers with yearly gross income up to €20,000.Footnote 15 With the view to support pensioners, in August 2022, the government decided to anticipate by three months (to October) the indexation of pensions up to €35,000 – using as reference index an inflation rate of 7.3 per cent.Footnote 16

Private companies were also asked to complement the action of the public sector. In 2022, energy providers were asked to offer domestic customers a plan for the payment of (outstanding) bills in instalments issued in the period January–April 2022.Footnote 17 In addition to this, the government introduced fiscal incentives for firms that provide additional benefits to help their workers in dealing with the increase in energy prices.Footnote 18 Under this scheme, ‘company bonuses’ for energy and water bills, and for fuel costs are exempted from personal income tax. At the same time, the limit as to which companies can deduct their costs with these bonuses in corporate tax was raised from €258 to €800 per worker – and later in November 2022 to €3,000, per worker.Footnote 19

Portugal

The response to the cost-of-living crisis in Portugal must be seen in the context of a strategic decision – by governments from both the right and the left – that, after the Euro-Crisis, the weight of public debt from public finances had to be reduced (see Fig. 3), and the changes in the political landscape following the 2019 election. After governing for four years in a minority government, supported by the Communist Party (PCP) and the Left Bloc (BE) in Parliament (Fernandes et al., Reference Fernandes, Magalhães and Santana-Pereira2018), the Socialist Party (PS) was reinstated in government in the 2019 election. However, and crucially, its partners in Parliament saw their vote share shrink. The political scenario changed very quickly, to the point that (in October 2019) PCP and BE voted against the 2022 budget, which led to the resignation of the PS government and the scheduling of new elections – from which PS came out a solid overall majority and more autonomy to pursue its goal of keeping public finances in good health.

The response by the Portuguese government was largely directed at limiting the pass-through of international energy prices to consumers. Among other measures, this involved (a) the introduction of a price cap on energy prices derived from natural gas and coal, approved by the European Commission for Portugal and SpainFootnote 20 and on access charges to electricity networks; (b) allowing gas consumers to (temporarily) return to the regulated market, where gas prices are significantly lowerFootnote 21 ; (c) reductions/exemptions of taxes on oil and energy goods – notably, the reduction of the VAT rate on electricity from 13 per cent to 6 per cent (but only for consumptions up to 100 kWh p/month)Footnote 22 and the introduction of an adjustment mechanism of the tax on petroleum and energy products to neutralise the impact of price spikes on the VAT charged on fuelFootnote 23 ; and, finally, (d) the introduction of rebates on fuels (AUTOvoucher)Footnote 24 and bottled gas purchases.Footnote 25

In parallel, the Portuguese government introduced measures to help families deal with the cost of rising prices. Thus, in March 2022, the government introduced a one-off €60 payment for families benefiting from the social energy tariff.Footnote 26 This benefit was later expanded to cover beneficiaries of means-tested schemes.Footnote 27 This was followed by a series of one-off payments: a second €60 payment, in JuneFootnote 28 ; a €125 payment, in September, for citizens with income of up to €2700 p/month, complemented by a €50 payment p/child in the householdFootnote 29 ; and, in December, a €240 benefit for families receiving the energy social tariff or means-tested benefits.Footnote 30 The government also introduced a one-off payment for pensioners, equivalent to half the value of their pensions.Footnote 31 However, this was an expedient to compensate pensioners for its decision of not indexing pensions in 2023 in line with the existing pension indexation rules.Footnote 32 In addition to these measures, the government also introduced a number of compensatory measures such as a moratorium on the payment of social security contributions by employers and self-employed workersFootnote 33 ; or limiting rent increases.Footnote 34

An important part of the Portuguese response to the cost-of-living crisis, which would take effect in 2023, was the signature of the Income and Competitiveness Agreement (Comissão Permanente da Segurança Social, 2022) with social partners, which set targets for increases in wages both in the private and in the public sector, as well a schedule for recovering the purchasing power of minimum wage workers. Reflecting the terms of this Agreement, the 2023 budgetFootnote 35 includes an increase of income-tax brackets above the rate of inflation – estimated to reach 4 per cent in 2023; and the increase of the Social Benefits Indexing Factor (which is used to update non-contributory benefits) by 8 per cent.

Spain

Spain entered the cost-of-living crisis having been the most hit nation within SE, and one of those that took longer to recover from the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. On the political side, the response was led by the coalition between the social democratic Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) and Podemos – a left-wing, populist party (see Ramiro and Gomes, Reference Ramiro and Gomez2017) – that, having been in office since the January 2020, had also led the response to the pandemic crisis.

The Spanish government’s response strategy rested on two pillars: (a) trying to limit, as much as possible, the pass-through of international retail energy prices to consumers; and (b) providing emergency, temporary support to low-income households/individuals – where low-income individuals are generally identified as having incomes is below €12,600 (no dependants) or €16,800 (one child) or €21,000 (two or more children), depending on the policy.

In the second part of 2021 the government implemented a variety of tax measures to rapidly reduce the price of energy for households, including a discount for vulnerable consumers. Since June 2021 the Spanish government reduced electricity VAT from 21 per cent to 10 per cent,Footnote 36 suspended the tax on energy productionFootnote 37 , and a reduced the special tax on electricity from 5.1 per cent to 0.5 per centFootnote 38 . In September 2021, a cap to the growth of the gas tariff was also introduced. All these measures were extended in January, March, June, and December 2022.Footnote 39

In 2022, the government proposed the EU partners and finally implemented what has been called the Iberian exception and three additional policy packages in March, June, and December 2022.Footnote 40 The cap on the price of gas used in electricity generation has been particularly effective intervening the wholesale electricity market.Footnote 41 In addition to this, the government increased the generosity of the minimum income scheme and of non-contributory old-age pensions.Footnote 42 A one-off €200 payment for low-income and low-asset households was also introduced.Footnote 43

In March 2022, in addition to prolonging a number of existing programmes, the government introduced a set of new measures, including: a bonus for the purchase of public transport ticketsFootnote 44 and a reduction in tax rates on fuels of about twenty cents per litreFootnote 45 ; a limit to housing rent increases to 2 per centFootnote 46 ; a further (15 per cent) increase of the Minimum Income SchemeFootnote 47 ; and, finally, a €200 direct payment to low-income households who do not receive the Minimum Income Scheme or a non-contributory pension.

In June 2022, a new package was introduced. Besides extending previous programmes, new measures involved the increase in non-contributory pensions (15 per cent)Footnote 48 , a further reduction in electricity VAT (from 10 per cent to 5 per cent).Footnote 49 Finally in December 2022 – except the reduction in tax rates of fuels – all measures were extended to the subsequent year. Further measures involved the elimination of VAT on key food basic products (from 4 per cent); a reduction (from 10 per cent to 5 per cent) of the VAT rates on oil and pasta; and a direct payment of €200, payable for families with income below €27,000 and assets below €75,000 (up to 31 March 2023).

Fighting the cost-of-living crisis in Southern Europe: A (tentative) comparative assessment

In this section we identify the similarities/differences in the response to the cost-of-living crisis in SE. Before going into that, it is important to stress the important commonalities between the response to the current crisis and the response put forward by SE nations to the COVID-19 pandemic. The most obvious similarity is the intense level of state activism (see Moreira et al., Reference Moreira, Léon, Coda Moscarola and Roumpakis2021), evident in the plethora of measures introduced in such a small period of time. The second, important, continuity concerns the comprehensive use of measures that are outside of the realm of the welfare-state to pursue social policy-related ends (see Moreira and Hick, 2021). Finally, we also observe the tendency of using, more or less targeted, one-off payments (GR, IT, PT, ES) to support families – which was a hallmark of the crisis-response model that emerged during the pandemic (see Béland et al., Reference Béland, Cantillon, Hick and Moreira2021).

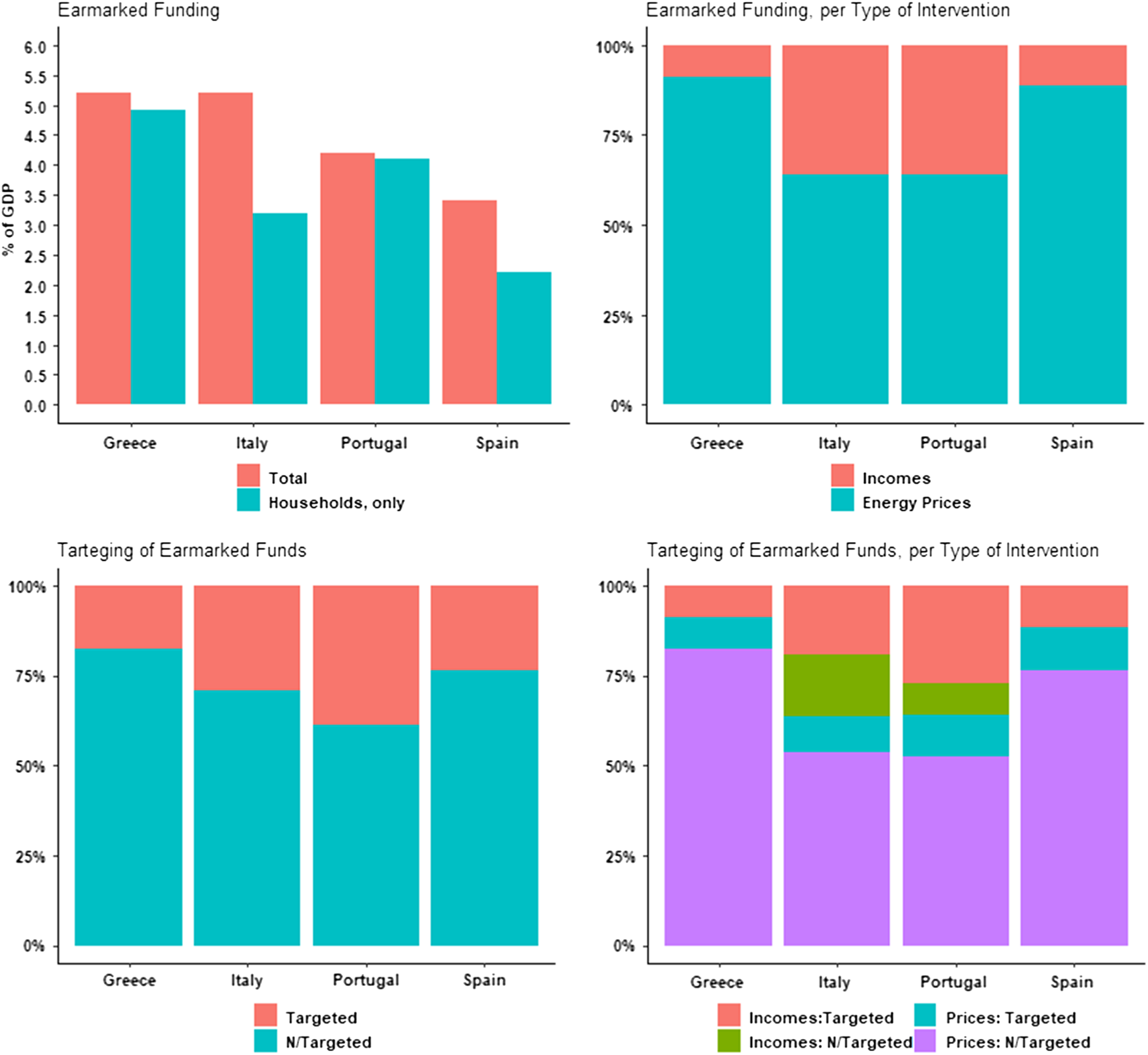

We start our analysis by looking at data compiled by Sgaravatti et al., (Reference Sgaravatti, Tagliapletra, Trasi and Zachmann2021), on the budgeted cost of support measures introduced in EU member states in the period between September 2021 and January 2023 (see Fig. 5). While it does not reflect the actual implementation of the measures on the ground, this data does provide important information as to the size and nature of the fiscal responseFootnote 50 to the cost-of-living crisis in SE.

Figure 5. Earmarked funding to cost-of-living crisis response packages.

Source: Sgaravatti et al. (2021): Authors’ calculations

As can be seen in Fig. 5 (Panel A), the (planned) fiscal response to the cost-of-living crisis in SE was fairly substantial – ranging from 5.2 per cent of GDP in Greece and Italy, to 3.4 per cent in Spain – especially when we consider the size of the fiscal packages in other European nations (see Sgaravatti et al., Reference Sgaravatti, Tagliapletra, Trasi and Zachmann2021). However, these values include the funding of support measures to firms, which are outside of the remit of our analysis. If we focus solely on the funding of measures targeting families, we can see that within SE, Greece and Portugal provided the strongest fiscal response to the crisis – 4.9 per cent and 4.1 per cent of their GDP, respectively. Italy and Spain have put forward a less substantive response – 3.1 per cent and 2.2 per cent of GDP, respectively.

As can also be seen (Fig. 5, Panel B), much of social policy response is directed at limiting the pass-through of international energy prices to consumers. As shown above, this involved a plethora of measures such as the introduction of reduction of (VAT and excise) taxes and charges on energy products (GR; IT, PT, ES); the capping of the price of some energy products (e.g. gas bottles) (PT, ES); or the introduction of energy price subsidies (ES) and/or rebates (GR, PT, IT) to reduce the cost of energy prices on consumers. There were also important efforts to intervene in both the wholesale (PT, ES) and retail energy markets (GR, IT, PT, ES).

Crucially, there are significant differences in the importance given to (traditional) social transfers in the response to the cost-of-living crisis in SE (see Fig. 5, Panel B). In Spain and Greece, social transfers represent a very small share (about 10 per cent) of the total fiscal effort directed at supporting families. In Portugal and Italy, on the other hand, social transfers represent (approximately) one-third of all the support targeted at families.

As Fig. 5 (Panels C and D) shows, the priority given to interventions in the formation of energy prices explains the differences in the degree to which SE governments have targeted more disadvantaged families in the design of the response to the cost-of-living crisis. Thus, countries where (traditional) social transfers play a bigger role in the fiscal response to the inflation crisis, there seems to be greater focus on targeting support at the least well-off families. This is the case of Portugal, where close to 40 per cent of all allocated funds are targeted at less privileged families. To a lesser degree, this also is the case of Italy.

In addition to this, there are also important differences concerning the role given to (a) indexation mechanisms and (b) wage increases in the response to the cost-of-living crisis in SE. Although the use of one-off payments to compensate families for the increase in prices is common to all four countries, in Spain and Italy this was articulated with the upgrading of existing benefits. This is the case of Italy’s government decision to anticipate the indexation of old-age pensions (see Section 3.2), or the Spanish government’s decision to increase minimum income benefits. Portugal and Greece, on the other hand, relied exclusively on (mainly targeted) one-off payments to compensate families for the increase in prices.

As the previous section also makes clear, SE governments have – in general – shied-away from promoting the adjustment of wages as a way of responding to the increase in inflation. Public sector wages were not increased – which could be seen as a way of signaling that wage restraint, rather than wage increases was seen as the preferred policy in this respect. Minimum wages in Spain and Portugal increased, but only by reference to previously scheduled values. The exception to this was Greece, where, as a response to the crisis – the government decided to significantly increase the minimum wage in 2022 (see above) – this however must also be understood in the context of the looming legislative election, and the attempt by the incumbent centre-right government to strengthen its electorate appeal. In what can be a sign of a (potential) change of policy in this domain both Portugal and Greece have signaled the intent for increase wages in 2023, and to work towards the recovery of the purchasing power of wages in subsequent years.

The distributional effects of the policy responses to the cost-of-living crisis

Recent evidence points to significant cross-country differences concerning the redistributive effects of the measures introduced during the cost-of-living crisis in SE. Focusing on Greece, Pierros and Theodoropoulou (Reference Pierros and Theodoropoulou2023) find that – after subsidies and transfers – lower income households in Greece had still to pay a larger share (13 per cent) of their disposable income to maintain the same consumption levels as 2021, than individuals situated higher above in the income scale.

In contrast, evidence from Italy suggests that the measures implemented by the executive significantly mitigated the impact of inflation on the income distribution (see Ufficio Parlamentare di Bilancio, 2022). Curci et al. (Reference Curci, Savegnago, Zevi and Zizza2022) find that in the case of Italy government measures exerted a remarkable redistributive effect, offsetting a large part of the heterogeneity of the shock across income levels. This was achieved either by pushing the price level of some goods downwards (for all consumers or for a selected share of them) or by increasing the income of a significant number of earners.

Evidence from Spain points in a similar direction. Badenes-Plá (2023) shows that the €200 payment and the 15 per cent increase in the national minimum income scheme and non-contributory pensions have had beneficial impact on inequality and poverty reduction in Spain. There is also evidence that the reduction of the VAT on electricity and gas and on food resulted in greater savings (relative to total spending) for lower-income households (Autoridad Independiente de Responsabilidad Fiscal, 2022; and Badenes-Plá, Reference Badenes Plá2023). However, the fuel subsidy introduced during that period generated higher savings for higher-income households as the Autoridad Independiente de Responsabilidad Fiscal (AIREF) (2022) and García-Miralles (Reference García-Miralles2023) show.

Conclusion

In their analysis of the (initial) response the COVID-19 in SE, Moreira et al. (Reference Moreira, Léon, Coda Moscarola and Roumpakis2021) have identified important similarities both in the size of the fiscal response to the pandemic crisis, and in the type of social policy measures adopted during that period. There were, nonetheless, important differences concerning the scope and inclusiveness of the response to the pandemic – with Portugal, Italy and Spain opting for a more comprehensive response, that involved improving/expanding existing wage subsidy/job retention schemes, and Greece relying more on a series of one-off payments. Focusing specifically on Portugal and Greece, Béland et al. (Reference Béland, Cantillon, Hick, Greve, Moreira, Börner and Seeleib-Kaiser2023) suggest that these differences reflect a long-term process of policy divergence within the SE regime – whereby by the Portuguese welfare-state has become increasingly inclusive, whereas the Greek welfare state has remained largely fragmented and inadequate.

As the previous section shows, there are important similarities in both the size and nature of the response to the cost-of-living crisis in SE. Except for Spain, SE nations have put fairly a substantive fiscal response to the current crisis – both when compared with its European neighbours (see Sgaravatti et al., Reference Sgaravatti, Tagliapletra, Trasi and Zachmann2021), and with the fiscal response to the pandemic crisis (see Moreira et al., Reference Moreira, Léon, Coda Moscarola and Roumpakis2021). SE governments have also privileged interventions upstream the welfare state, with measures targeting the formation of energy prices, and the reduction of the cost of energy to consumers. In line with what happened in the pandemic crisis (see Moreira et al., Reference Moreira, Léon, Coda Moscarola and Roumpakis2021), governments have made abundant use of one-off temporary payments to assist families in need. Despite this significant level of policy-convergence, we do find important differences concerning the weight given to (traditional) welfare transfers (stronger in Portugal and Italy), and the role given to indexation mechanisms and wage increases in fighting the cost-of-living crisis.

At the time this article is written, the cost-of-living crisis is still causing economic and social harm. This means that, most probably, more support measures will be introduced in the near future. Future research will, hopefully, continue to monitor the response to the cost-of-living crisis in SE. Not only that, forthcoming research will hopefully help us to get a more in-depth knowledge about the factors that have shaped both the size and nature of the response to the cost-of-living crisis in SE.

First, it is important that future research examines the degree to which the responses to the current crisis was shaped by differences in the size and nature of inflationary pressures. In this particular regard, it will be important to assess to what degree this response was influenced by differences in the weight of energy prices in the overall inflationary dynamic (see Fig. 2).

Second, it is important that future research explores how the response to the cost-of-living crisis is influenced by the fiscal position of SE nations, as they were coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic (see Romer, Reference Romer2021). In this particular regard, it will be important to understand to what degree, as result of the changes in the EU’s fiscal governance prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic (de la Porte and Heins, Reference De la Porte and Heins2022), the weight of public debt remains a relevant variable in explaining the size and nature of the fiscal response to the inflation crisis in the SE (see Moreira et al., Reference Moreira, Léon, Coda Moscarola and Roumpakis2021).

Thirdly, future research should look at the importance of the partisan composition of the executive in shaping the response to the cost-of-living crisis. In particular, it will be important to understand if the presence of populist parties in the executive (Afonso, Reference Afonso2015), as was the case in Spain (from the start) and in Italy (later), can help to explain differences in the size and nature of the response to the inflation crisis.

Fourth, building on the findings put forward by Béland et al. (Reference Béland, Cantillon, Hick, Greve, Moreira, Börner and Seeleib-Kaiser2023), future research should examine the way in which the response to the cost-of-living crisis in SE was shaped by the set institutional features that have come to characterise the Southern model of social protection (Ferrera, Reference Ferrera1996), and by how these have to evolve over time (Petmesidou and Guillén, Reference Petmesidou, Guillén and Greve2021).

Finally, future research should not only deepen the focus about on the distributive impact of the measures introduced during this period, but should also seek to explore in what way they compare with the redistributive effects of the measures taken in response to COVID-19 pandemic (see Almeida et al., Reference Almeida, Barrios, Christl, De Poli, Tumino and van der Wielen2021).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S147474642400006X

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to three anonymous referees for their very useful comments. We would also like to thank the editors of this themed section for creating the opportunity to write this article, and especially to the editorial team at Social Policy and Society for their support throughout the submission and production process.