Sensing Musical ‘Strangeness’

When the composer Jean Roger-Ducasse first heard the virtuoso pianist Marguerite Long play Maurice Ravel's Le Tombeau de Couperin in a private performance in May 1918, he was shocked to find that Ravel had dedicated a suite of cheerful dances to dead soldiers. He was even more perplexed by Long's exuberant willingness to perform these jovial pieces, especially since Ravel had dedicated the suite's final movement to her husband. Roger-Ducasse was particularly troubled by the mismatch between the music – which he claimed didn't contain even ‘a measure of emotion’ – and the dedications – which he said would have been better suited to ‘dancers or pleasure girls’. Roger-Ducasse wondered if Ravel, whom he calls a ‘bizarre being’, had intended to play a cunning joke ‘by establishing a paradox between the sounds of his notes and the glorious syllables of [the names of the dedicatees]’.Footnote 1 Others shared Roger-Ducasse's consternation: Ravel wrote to Léon Vallas in August 1919 about how some people had been ‘astonished that this homage to the dead should not have a funereal, or at least a morose quality’.Footnote 2

The other compositions that Ravel wrote immediately following World War I have been similarly received as ‘strange’ by both his contemporaries and later historians. Although Ravel's 1918 composition Frontispice was not reviewed in his lifetime, his biographers have considered this 15-bar piano piece one of the oddest in his oeuvre. Roger Nichols refers to it as ‘one of [Ravel's] strangest’, and posits that ‘the music itself is puzzling’, with ‘scant connection to anything Ravel had written before’.Footnote 3 Marcel Marnat similarly calls the work ‘the strangest by Ravel’, clarifying that, ‘the language here is as new as possible, astonishingly removed from the rest of the création ravélienne’.Footnote 4 Likewise, critics of Ravel's La Valse found the 1920 ballet fantastic, spectral and surprisingly violent. Ravel's friend Florent Schmitt considered La Valse's nested waltz themes to be fear-inducing and described the piece's conclusion as ‘a worrying and intense ride’.Footnote 5 The critic Alexis Roland-Manuel noted the ballet's ‘phantom dancers’ and the sense of ‘hallucination’ that it brought to the listener. He was especially enamoured of Ravel's use in this piece of ‘a mute and coarse violence’, which he asserted the composer had hinted at in Daphnis et Chloé, but which only came to full fruition in La Valse's contrasts between ‘muted darkness’ and the ‘caressing and frenetic turns of the dancers’.Footnote 6 And in a review for Le Temps, Theodor Lindenlaub called La Valse a ‘danse macabre’, relaying that Ravel's waltzes left a ‘spectral impression’.Footnote 7

In this article, I take these assertions of strangeness, violence and spectrality as starting points for considering how the three compositions that Ravel completed between 1917 and 1920 – when taken together – reveal traces of his traumatic wartime experiences, including the months in 1915 and 1916 that he spent on French battlefields, as well as his mother's death in 1917. Scholars of French music, including Jane Fulcher, Martha Hyde, Barbara Kelly and Carolyn Abbate, have provided insightful analyses of Ravel's Le Tombeau de Couperin, interpreting the piece variously in terms of French neo-classicism, musical modernism, nationalism, contemporary wartime and interwar French politics, traditions of homage, and even the loss of the live performer that accompanied the rise in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries of recording and automatic-playing technologies such as the pianola and the player piano.Footnote 8 Deborah Mawer, Michael Puri and Sevin Yaraman have likewise interpreted Ravel's La Valse in terms of interwar politics, musical modernism, memory and nostalgia, balletic and social dance styles, choreography and the losses of the war years, including Ravel's mother's death.Footnote 9 Even though Frontispice is one of Ravel's lesser-known pieces, numerous scholars, including pianola expert Rex Lawson, Deborah Mawer and Tobias Plebuch have explored the composition's history in terms of provenance, performance practice, numerical symbology, and Ravel's often terrifying military experiences.Footnote 10 Although several of these fascinating interpretations account for Ravel's painful losses and wartime experiences in the 1910s, no one has yet examined Le Tombeau, Frontispice and La Valse in tandem in order to explore what these pieces – when considered within Ravel's socio-cultural context – tell us about the particularities of Ravel's grief and ongoing trauma in the years immediately following the war.

As researchers in music studies have demonstrated, paying attention to musicians’ emotional lives holds the potential to reveal new insights not only about people who make music, but also about musical compositions and practices, as well as about how music takes on meaning in different social, historical and emotional contexts. Musicologists Maria Cizmic, Tamara Levitz, Nicholas Reyland and Amy Lynn Wlodarski have recently demonstrated how grieving or traumatized twentieth-century composers bore witness to trauma in their works.Footnote 11 In a similar fashion, I utilize theories of grief and trauma alongside musical and socio-cultural analysis in order to demonstrate how Le Tombeau, Frontispice and La Valse can be understood as Ravel's personal testimonies of wartime traumatic experience. I focus in particular on Nicolas Abraham's, Maria Torok's and Jacques Derrida's theorizations of traumatic grief, in which they assert that unspoken grief is often clandestinely communicated in ‘magic words’ spoken – sometimes knowingly, sometimes not – by mourners.

I have turned primarily to Abraham's, Torok's and Derrida's conceptualizations of trauma in my analysis of Ravel's post-war compositions, rather than to Freud's or Janet's theorizations of trauma (which were developed during Ravel's lifetime), for a number of reasons – some personal, some historical and some theoretical. In the fall of 2009, when I began examining Ravel's compositions through the lens of grief and trauma, I was still mourning a loss that I had experienced several months before. Upon listening to Ravel's post-1917 compositions, including Le Tombeau de Couperin, Frontispice and La Valse, I was haunted by this music, struck by the sound of ghostly presence that I heard in poignantly highlighted silences, gleamingly dissonant passages and moments of strangeness and expressive forcefulness. Like Elizabeth Morgan, in her piece in this issue on sheet music of the Mexican–American War, I was especially drawn to what I perceived as Le Tombeau's affective dissonance – how the predominantly optimistic and cheerful affect of the suite's music seems at odds with the ostensible emotional gravity of the piece suggested by Ravel's dedications of each movement to a fallen fellow soldier. At around the same time, I found myself deeply affected by Abraham's, Torok's and Derrida's texts defining the psychic mechanics of mourning and melancholia: these resonated not only with my own experience of unspeakable grief, but also with what I heard in Ravel's compositions. In the decade since my initial encounter with Abraham's, Torok's and Derrida's theorizations of what they termed ‘impossible mourning’ – out of which ‘magic words’ emerge – I have come to find that their poignant ways of thinking about and describing the mechanics of grief and trauma have been useful in part due to their consideration of social and cultural taboos around the expression of emotion. As will be become evident in this article, their psychoanalytic theorizations of how traumatic grief manifests in different socio-cultural circumstances have become central to my argument about Ravel's experiences and expressions of grief and trauma. Moreover, Abraham's and Torok's theorizations, while not often applied to musical works,Footnote 12 are, in fact, quite illuminating, especially since each of these theorists was ultimately interested in interpreting literature and people's everyday actions and words through the lens of mourning. Derrida's writings on mourning are likewise useful not only because of his deep, fruitful and evocative explication of Abraham's and Torok's texts, but also for his extensive discussions regarding the politics of mourning – the power relations between the dead and the living, as well as how those relations are performed and to what ends – which I believe were central to how Ravel grieved and expressed trauma in his post-war musical compositions.

In what follows, I argue that the moments of strangeness that many critics have heard in Ravel's Le Tombeau, Frontispice and La Valse are indicative of musical ‘magic words’ that provide listeners with a counternarrative of how public mourning might take place in interwar France. Like the ‘magic words’ that Abraham and Torok heard patients repeat over and over again, the musical ‘magic words’ revealed in Ravel's repetition of certain musical gestures within and also across these pieces point to not only how Ravel felt about his traumatic experiences, but also to his particular politics of mourning, which have heretofore remained unexplored. Taken together, Le Tombeau, Frontispice and La Valse can be understood as Ravel's commentary on and resistance to the construction in interwar France of grief and trauma as negative, anti-nationalist, and feminine emotional states that required suppression. In order to determine how Ravel may have understood and experienced trauma in wartime and interwar France, and how it may have shaped his compositional strategies, I analyse published and unpublished letters, diaries, memoirs and essays of Ravel and his peers. Such sources open windows into these people's emotional lives that enable me to place Ravel's post-war compositions in the context of contemporary French conceptions of grief and trauma, including which musical conventions were considered suitable for expressing these states. These personal sources provide a crucial counterweight to the theoretical conception of trauma that I take from Abraham and Torok. Bringing these two forms of knowledge into dialogue allows me to develop an epistemology of grief and post-traumatic experience in interwar France that 1) illuminates musicians’ lived experiences of navigating and performing grief and trauma in their particular socio-cultural milieu, and 2) re-contextualizes Ravel's wartime and post-war compositions, suggesting in the process why critics might have found this music ‘strange’. In order to illustrate my interpretation of Le Tombeau, Frontispice and La Valse, I turn first to the ‘magic words’ and ‘cryptonymy’ of Abraham, Torok and Derrida, and second to an examination of the social norms surrounding the expression of grief and trauma in interwar France.

The ‘Strangeness’ of Traumatic Mourning: Spectrality, Cryptonymy and ‘Magic Words’

The ‘strangeness’ that many of Ravel's critics have heard in his compositions can be contextualized through a post-psychoanalytic discourse that has developed over the last century in which critical and psychoanalytic theorists, as well as psychologists, elucidate connections between trauma, mourning, misfitting and spectrality. Jacques Derrida – a colleague and supporter of Abraham and Torok – wrote in Specters of Marx of the ‘out-of-joint-ness’ of time as an indication of a spectral presence tied to loss.Footnote 13 Abraham and Torok, drawing on their experiences with patients who they identified as traumatized mourners, read literature for moments where melancholic authors indicated in their texts the existence, causes and terms of their traumatically repressed grief in cryptic but revealing ‘magic words’. For Abraham and Torok, magic words were signals to them that, once they became aware of them, could help them both to identify a patient's trauma, and to help them work through it. In their 1971 study of Freud's ‘Wolf-Man’, Abraham and Torok posited that, for the Wolf-Man, a word, ‘in a multitude of disguises, formed the focal point of the subject's entire libidinal life, including sublimation’.Footnote 14 Put simply, a word had come to monopolize the Wolf-Man's psyche, and his consistent repetition of the word tipped off Abraham and Torok not only to the existence of a traumatic experience, but also to the nature of that experience.Footnote 15 Through the example of the Wolf-Man, Abraham and Torok – and later Derrida, who wrote an eloquent and somewhat cryptic foreword for the book – developed the psychoanalytic concepts of ‘cryptonymy’ and ‘phantoms’, terms that describe traumatic grief's propensity to result in the psyche's creation of a crypt in which a lost love object remains entombed, but not without occasional escapes that haunt the mourner.

Abraham and Torok took the presence of the Wolf-Man's ‘magic word’ as an indication that what they termed ‘the fantasy of incorporation’ had taken place. For them, this was the psychic result of not being able to ‘swallow’ a loss, which led the subject to swallow instead the ‘word, demetaphorized and objectified’.Footnote 16 In this way, the psyche creates a ‘crypt’ in the ego:

Grief that cannot be expressed builds a secret vault within the subject. In this crypt reposes – alive, reconstituted from the memories of words, images, and feelings – the objective counterpart of the loss, as a complete person with his own topography, as well as the traumatic events – real or imagined – that had made introjection impossible. In this way a whole unconscious fantasy world is created, where a separate and secret life is led. Yet it happens that with libidinal activity, ‘in the middle of the night’, the phantom of the crypt may come to haunt the keeper of the graveyard, making strange and incomprehensible signs to him, forcing him to perform unwonted acts, arousing unexpected feelings in him.Footnote 17

Abraham and Torok suggest that this crypt-keeping may be due to traumatic circumstances surrounding loss, social norms that render the expression of grief difficult, or the presence of a shameful secret that the mourner keeps for the person being mourned after their death. Regardless, however, they assert that it is shame and guilt – and the ways in which these affects prevent mourners from being able to discuss and process their loss – that create a secret crypt inside the mourner's ego.Footnote 18

Although Abraham and Torok focused specifically on what they called ‘impossible mourning’ in their studies of the 1960s and 1970s, their development of psychic cryptonymy strongly resembles definitions of trauma developed between the late nineteenth-century and today. In the 1880s French psychologist Pierre Janet proposed that trauma often resulted in an idée fixe, and in 1920, Freud asserted that traumatized patients – and specifically former soldiers – frequently possessed a ‘compulsion to repeat’ their initial traumatic experiences in words and behaviours.Footnote 19 In 1992, Judith Herman asserted in her watershed book Trauma and Recovery the tendency of traumatic events to be buried in the psyche:

The ordinary response to atrocities is to banish them from the consciousness. Certain violations of the social compact are too terrible to utter aloud: this is the meaning of the word unspeakable. Atrocities, however, refuse to be buried. Equally as powerful as the desire to deny atrocities is the conviction that denial does not work.Footnote 20

In the formulations of Abraham and Torok, it is precisely this unspeakability that leads to cryptonymy, and it is words – specifically ‘magic words’ – that betray the existence of the crypt in the psyche of the person whose life has become haunted.

But what if a traumatized person is a musician? What in their musical compositions and performances might convey something about their grief or trauma? How might musicians use music to communicate what is otherwise unspeakable? Literary scholars such as Cathy Caruth, Jonathan Flatley and Eve Sorum, as well as musicologist Tamara Levitz, have helpfully suggested that loss and trauma frequently appear in modernist texts in moments where readers perceive absence, strangeness or incongruity. In his study of what he terms modernist literature's ‘affective maps’, Flatley observes that melancholic modernist authors such as Henry James ask readers to engage in ‘a kind of bodily immersion’ engendered through ‘just enough noncomprehension to necessitate reading into the text’.Footnote 21 Caruth locates performed trauma in twentieth-century literature's ‘crying wounds’, whereas Sorum discovers Ford Maddox Ford's wartime trauma in his interwar novels’ ellipses – marked absences that signal the unspeakable wounds of traumatic experience.Footnote 22 Levitz, on the other hand, has considered instances of incongruity in the second tableau of Perséphone, the 1934 collaboration of Igor Stravinsky, Ida Rubinstein, André Gide and Jean Cocteau. For her, Gide's libretto reveals his grief over the deaths of loved ones in moments of rupture and discord. Similarly, Stravinsky performs mourning in this scene through musical pastiche: ‘sudden temporal shifts, evidence of pain masked with nostalgic pleasure, neoclassical borrowings, and outbursts of sentimental memories.’Footnote 23

Ravel likewise employs musical ruptures, affective dissonance and noticeable gaps in his post-1917 compositions that function as indicators of the grief and trauma that he was coping with in the years following his military service. Like Caruth's assertion of ‘crying wounds’ as markers of trauma in literature, the mid-twentieth-century philosopher Vladimir Jankélévitch wrote in La Musique et l'ineffable of the ‘wrenching cries’ that he heard in much of Ravel's music, including the interwar compositions Chansons madécasses and L'Enfant et les sortilèges.Footnote 24 For Jankélévitch, Roland-Manuel and, more recently, Michael Puri, Lloyd Whitesell and Stephen Zank, moments of rupture and discord in Ravel's music are markers of Ravel's aesthetic of masking, which they have understood as tied to his modesty or, in French terminology of the time, pudeur – an often class- and gender-based modesty in terms of sexuality and self-expression.Footnote 25 Speaking specifically about Le Tombeau, Jankélévitch even tied Ravel's masking tendency to his dances, which in their ‘appearance of frivolous detachment’ serve ‘the baffling stratagems of modesty’.Footnote 26 Puri and Whitesell, along with Zarah Ersoff, have importantly read Ravel's ‘wrenching cries’, ruptures and affective dissonances as markers of his dandyist sublimation and repression of queer sexual desire in a time when such desires were not only socially transgressive, but also illegal.Footnote 27 Although Ravel's concerns with aesthetic and sexual self-fashioning certainly did not disappear after 1917, they may nevertheless have been overrun by new emotional concerns that further complicated his choices for musical self-presentation. We can imagine, for instance, that the ‘suppression of the “natural”’ through an ‘artful manipulation of posture, social skill, manners, conversation, and dress’, which was central to fin-de-siècle French dandyism, would have become even more agonizingly difficult when a dandy is faced with unexpressable war-related emotional trauma, and the intense grief that accompanies the loss of a close friend or, more painful still, a parent with whom one has spent all the years of his life save the last.Footnote 28 That a substantial shift in Ravel's compositional aesthetics took place at precisely around this time – from pieces before the war more in line with a post-Romantic, French Symbolist aesthetic to a post-war style marked by a stripped-down, highly repetitive, and more overtly modernist aesthetic – suggests that the war and the events that transpired during Ravel's military service significantly affected his psyche and, in turn, his creative output.Footnote 29

Throughout the remainder of this article, I show how Ravel's Le Tombeau, Frontispice and La Valse exhibit what I term cryptonymic logic. The ‘wrenching cries’ of Ravel's traumatic experiences resound repeatedly throughout these three compositions, manifesting as sonic socio-emotional crypts that, as in Abraham's and Torok's definition, contain enshrined memories and affects. Notably, in each of these pieces Ravel musicalizes the closure of the crypt: the place where, according to Abraham and Torok, the crypt is finalized and a ‘monument’ created to mark its location. This monument takes the shape of ‘magic words’, unconsciously repeated by the traumatized mourner, and imbued with the violence of the initial traumatic experience, as well as with the force of the traumatized person's often unconscious attempts to bar that experience and its affective dimensions from consciousness.Footnote 30 What I propose is that musical moments of crypt-closing violence can be heard throughout Ravel's immediately post-war compositions. Instead of openly confessing his pain, Ravel provides listeners with musical traces of his trauma. To put this another way: Ravel repeatedly, perhaps even compulsively, composes the crypt – not only to bear witness to his own trauma in ways that might help him to cope with the emotional aftereffects of traumatic experience, but also in order to critique dominant understandings in interwar France that grief and trauma were social and emotional experiences that required containment and, ultimately, erasure.Footnote 31

Ravel's Emotional-Creative Context: Grief, Trauma, and Music in Interwar France

Ravel completed Le Tombeau de Couperin, Frontispice and La Valse between 1917 and 1920, when he was attempting to cope with the grief and trauma he had encountered between August 1914 and the spring of 1917. After beginning Le Tombeau de Couperin in the summer of 1914, Ravel returned to it in the spring or summer of 1917 – just after his release from the military – and completed it in November of the same year.Footnote 32 In the interim, Ravel endured the deaths of numerous friends; served two years as a truck driver in the French army; suffered a hernia that was surgically repaired in the fall of 1916; and faced the loss of his mother in January 1917.

Ravel's wartime letters to friends and family indicate that, although his military service did not involve fighting on the front lines, it nevertheless presented him with experiences that terrified him.Footnote 33 He wrote to Jean Marnold on 4 April 1916 about a mission he had recently undertaken in which:

I saw a hallucinatory thing: a nightmarish city, horribly deserted and mute. It isn't the fracas from above, or the small balloons of white smoke which align in the very pure sky; it's not this formidable and invisible struggle which is anguishing, but rather to feel alone in the center of this city which rests in a sinister sleep, under the brilliant light of a beautiful summer day. Undoubtedly, I will see things which will be more frightful and repugnant; I don't believe I will ever experience a more profound and stranger emotion than this sort of mute terror.Footnote 34

He wrote as well to Florent Schmitt about how his duties as a truck driver led him into dangerous war zones where ‘shells were falling all around’. He continued:

I didn't think it possible for a driver to see so many in so few days. One of them, an Austrian 130, sent the residue of its powder right into my face. Adélaïde and I – Adélaïde is my truck – escaped with only some shrapnel, but the poor thing couldn't hold up any more, and after leaving me in the lurch in a dangerous zone, where parking was forbidden, in despair, she dropped one of her wheels in a forest, where I played Robinson Crusoe for 10 days, while waiting for them to come get me out.Footnote 35

And in June of 1918 Ravel told Ralph Vaughan Williams that he had had ‘some moving experiences, occasionally painful, and perilous enough to amaze me that I'm still alive’.Footnote 36 Ravel's military service deeply affected him, forcing him not only to experience extreme solitude and danger, but also to face his own mortality.

Moreover, Ravel's letters from 1917 through the early 1920s demonstrate the depression and guilt that he felt after his mother's death. While still serving in the military, he wrote to his marraine de guerre, Madame Fernand Dreyfus, at the beginning of February 1917 about his ‘horrible despair’, which he said was only exacerbated by his captain telling him to ‘snap out of it’, and by ‘kind and cheerful comrades’ who make him feel ‘more isolated here than anywhere else’.Footnote 37 A few days later he wrote to his friend Ida Godebska, confessing that he was ‘terribly unhappy here’ and felt torn from ‘all that he cares about’ by a captain who continually tried to distract him from his grief.Footnote 38 Despite his captain's best efforts, Ravel's grief would continue well past his mother's death. He writes to Lucien Garban on 20 June 1917, for example, that he still wakes troubled in the middle of the night, ‘sensing her close to me, watching me’.Footnote 39

Ravel's grief may have been exacerbated by the guilt that he felt for having abandoned his mother when he began his military service. The psychologist Vamik Volkan has pointed out that survivor guilt – when someone feels either that they are culpable for another person's death, or that they should have died instead of the person they are mourning – often complicates mourning, rendering a traumatic response on the part of the mourner.Footnote 40 At the beginning of the war, Ravel repeatedly confessed to friends and family members his guilt over possibly having to leave his mother alone if he enlisted. He wrote to Maurice Delage on 4 August 1914: ‘If you only knew how I am suffering! … Since this morning, unceasingly, the same horrible, criminal idea … if I leave my poor old mama, it would surely kill her.’Footnote 41 A couple of weeks later, Ravel shared with Cipa Godebski that though he was planning to enlist, he was plagued with worry about his mother: ‘But I know, I am certain of what will happen when she learns that both of us [Ravel and his brother Edouard] are leaving: she won't even have to die of hunger’.Footnote 42 Although Ravel did not reveal to his friends his fears that his absence contributed to his mother's death, it would be difficult, given his guilt prior to his military service, to imagine that these fears did not contribute to his grief concerning her death.

Ravel was still mourning his mother's death in the winter of 1919–20, when he returned to working on La Valse. He told Ida Godebska that returning in 1919 to the composition he had worked on frequently in his mother's ‘dear silent presence’ filled with ‘infinite tenderness’, made him recall what it felt like to be with her.Footnote 43 At around the same time, while still in the midst of preparing La Valse for Ballets Russes impresario Serge Diaghilev, Ravel wrote to Hélène Kahn-Casella that, now that he had begun composing again, he ‘think[s] about [his mother] everyday, or rather every minute’.Footnote 44

Ravel's understanding and experience of mourning was shaped by the contemporary social moratorium on certain performances of grief and traumatic experience. Social theorist and trauma specialist Jeffrey C. Alexander has argued that narratives of loss and trauma – including how these are expressed socio-culturally – shape how societies conceptualize and deal with trauma; this was definitely the case in interwar France.Footnote 45 Although grief was permissible and even expected between 1914 and 1918, the type of loss determined the extent to which someone could publicly mourn a death. Losses unrelated to the war were not supposed to be mourned to the same extent as war losses, and it was usually more acceptable for women to mourn publicly than men. These dynamics are perhaps best captured by socialite and amateur musician Marguerite de Saint-Marceaux's comment in her diary about the Ravel brothers at their mother's funeral: ‘Both were in utter turmoil, incapable of reaction or self-control. A lamentable and distressing spectacle at this time when heroism displays itself as naturally as breathing’.Footnote 46

It is unsurprising, although not insignificant, that Ravel never described his wartime and post-war experiences in terms of trauma.Footnote 47 Discussions of trauma, whether related to the deaths of loved ones, or to war experiences more broadly, were generally frowned upon during his lifetime, and especially during and after World War I. As French historians Gregory Thomas, George Mosse, Louis Crocq, Stéphane Tison and Hervé Guillemain have shown, wartime military doctors controlled talk of trauma because they believed that it was contagious, and worried that ‘hysterical “suggestions” could spread among troops at the front, weakening morale, destroying discipline, and inspiring an epidemic of neuropsychiatric cases’.Footnote 48 In France during World War I, discourse about trauma – often described as hysteria at the time – framed the emotional or physical shock of violent combat as producing traumatic symptoms only in predisposed individuals who had exhibited a weakness of constitution prior to their military service. As a result, soldiers who complained about mental, emotional or physical problems that did not manifest in physical wounds came to be described as ‘weak-willed shirkers’.Footnote 49 In addition, because hysteria (the most commonly-recognized category of trauma) was predominantly, although not always, constructed as a feminine illness in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century France,Footnote 50 diagnoses of hysteria challenged the masculinity of French men, and led doctors to keep such diagnoses to a minimum for fear of ‘fostering an image of a weak-willed fighting force’.Footnote 51 As Mosse has demonstrated, trauma ‘betrayed’ the French masculine ideal, which ‘reflected … not only the ideals and the prejudices of normative society but also those of the nation’.Footnote 52 Consequently, those traumatized by wartime experiences – or any other experiences, for that matter – kept this to themselves, often taking up nationalistic language as a way of performing social expectations, even in the midst of internal emotional suffering. This is evident, for example, in a popular anecdote about a woman who, at the funeral of one of her six sons killed in the war, ‘emitted a grand and harrowing cry: “Vive la France quand même!”’Footnote 53

According to many in Ravel's circle, however, silencing one's grief had the potential to do additional harm, creating an inescapable feedback loop that exacerbated the pain of loss.Footnote 54 Marguerite de Saint-Marceaux wrote in her diary on the first anniversary of her husband's death of ‘hiding [her] pain’ and thus ‘destroying [her] heart’.Footnote 55 After Claude Debussy's death in 1918, his 12-year-old daughter Chouchou conveyed that containing her emotions led to more grief, pain and sadness. She explained to her half-brother Raoul Bardac that, ‘struggling against the indescribable grief’ of her mother, while ‘frightful’, allowed her to ‘for a few days … forget my own grief’. She adds, however, that ‘now, I feel it all the more poignantly’.Footnote 56

Although French music that addressed World War I took a wide variety of forms, much of the music written by art music composers during and after the conflict reflected this tendency to privilege nationalist sentiments over what might be considered more ‘open’ expressions of mourning or trauma. It is important to recall that these compositions are performances of mourning – social narratives of publicly expressing grief – that do not necessarily or completely reflect the lived experiences and emotions of the composers who wrote them. Rather, an examination of wartime and interwar compositions for public mourning sheds light on the conventions of musical mourning that were popular at this time. These conventions demonstrate how interwar French musical performances of grief shaped and were shaped by the dominant social performances of grief described above. In this way, and in line with the way that many other contributors to this special issue have been thinking about relationships between music and trauma, this body of compositions can be considered social narratives of grief and trauma akin to the media representations of trauma that Alexander discusses.Footnote 57

Perhaps surprisingly, although a handful of composers wrote requiems, few of these captured the attention of the French public during the interwar period. Rather, the art music compositions symbolizing mourning that came to be more well known in interwar France were patriotic pieces by composers such as Nadia Boulanger, Claude Debussy, Reynaldo Hahn and Florent Schmitt. Many of these compositions feature a particular narrative of mourning: mournful or lamenting music appears in their first halves, which are followed by second halves or conclusions featuring patriotic, propagandistic and celebratory expressions (see Table 1).Footnote 58 The Catholic musician-soldier André Caplet wrote several songs that addressed wartime mourning within a similar trajectory. In songs such as La Croix Douloureuse and Détresse, he suggests that submitting to God's will could enable the resolution of grief; he communicates this through movement from dark, sombre and mournful music in each piece's first half, towards hopeful, major-key resolutions in each song's conclusion.Footnote 59

Table 1 Compositions Depicting Grief with a Mourning-to-Celebration Narrative Trajectory

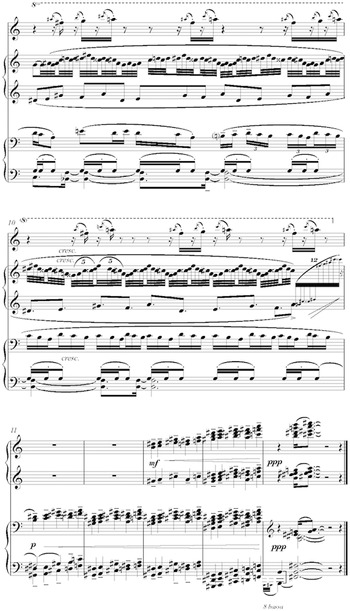

Nadia Boulanger's Soir d'hiver, written and first performed in the winter of 1914–15, provides a clear example of this narrative trajectory within wartime French music. In this short song Boulanger addresses how women on the home front sought modes of financial and emotional support while their husbands were away fighting. The song divides into two halves, the first of which focuses on the song's female protagonist as she sings a sad, minor-key lullaby to her child (Ex. 1a). In the song's second half, Boulanger recomposes the young mother's lullaby into a joyful celebration of France's eventual victory. The triumphant triplets and heroic leaps that characterize the song's second half, frame mourning as a necessary and worthwhile part of civic responsibility in wartime (Ex 1b).Footnote 60

Ex. 1a Nadia Boulanger, Soir d'hiver (Paris: Heugel & Cie, 1916), bars 4–23

Ex. 1b Nadia Boulanger, Soir d'hiver (Paris: Heugel & Cie, 1916), bars 33–44

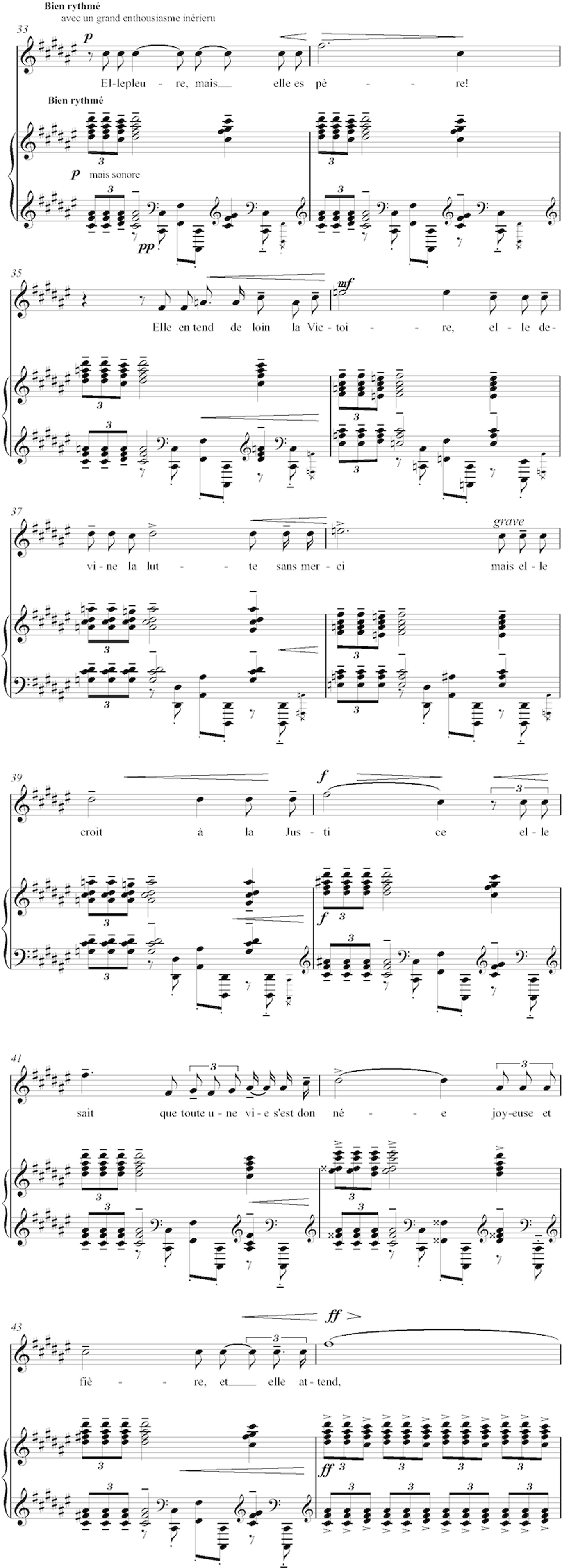

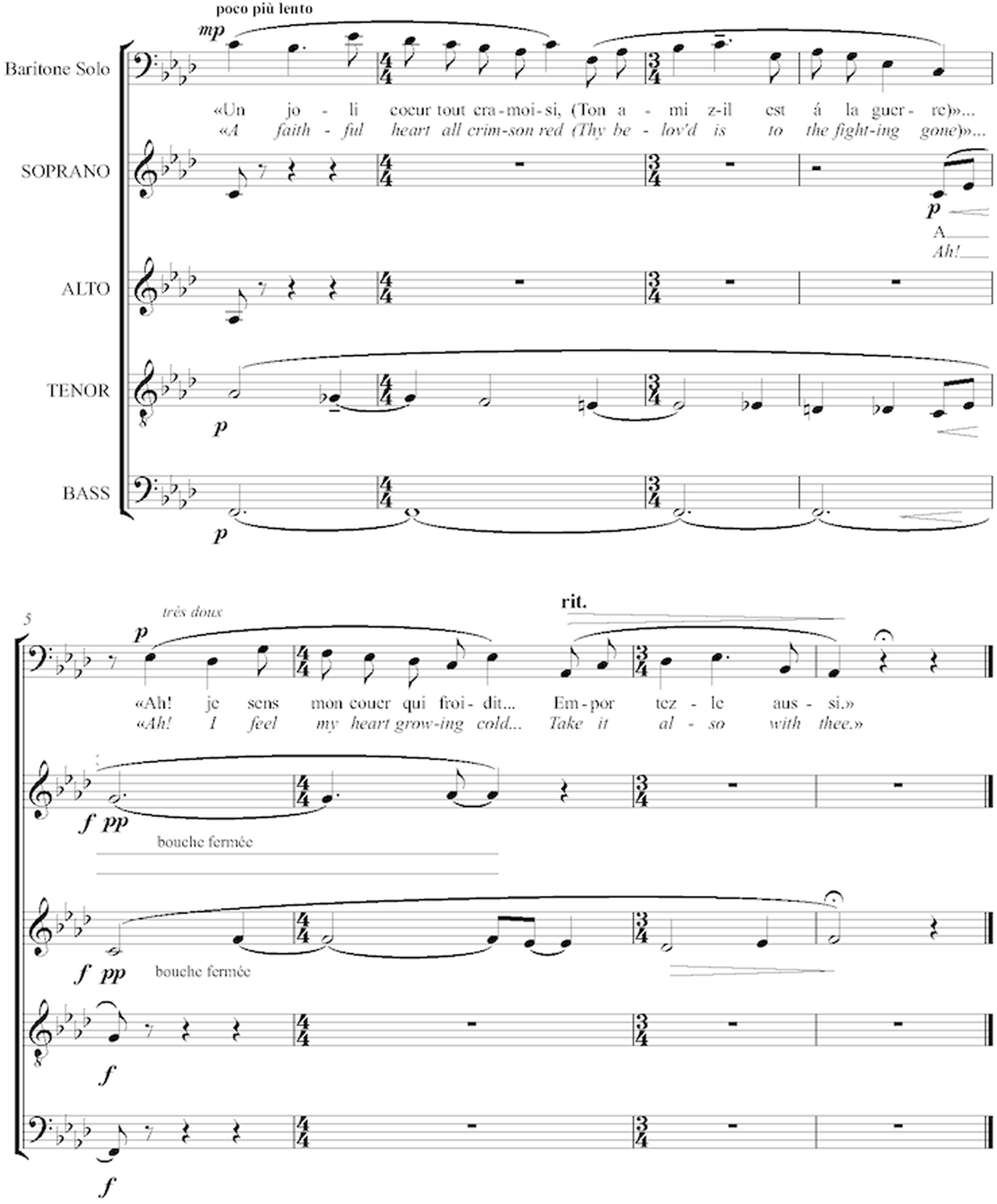

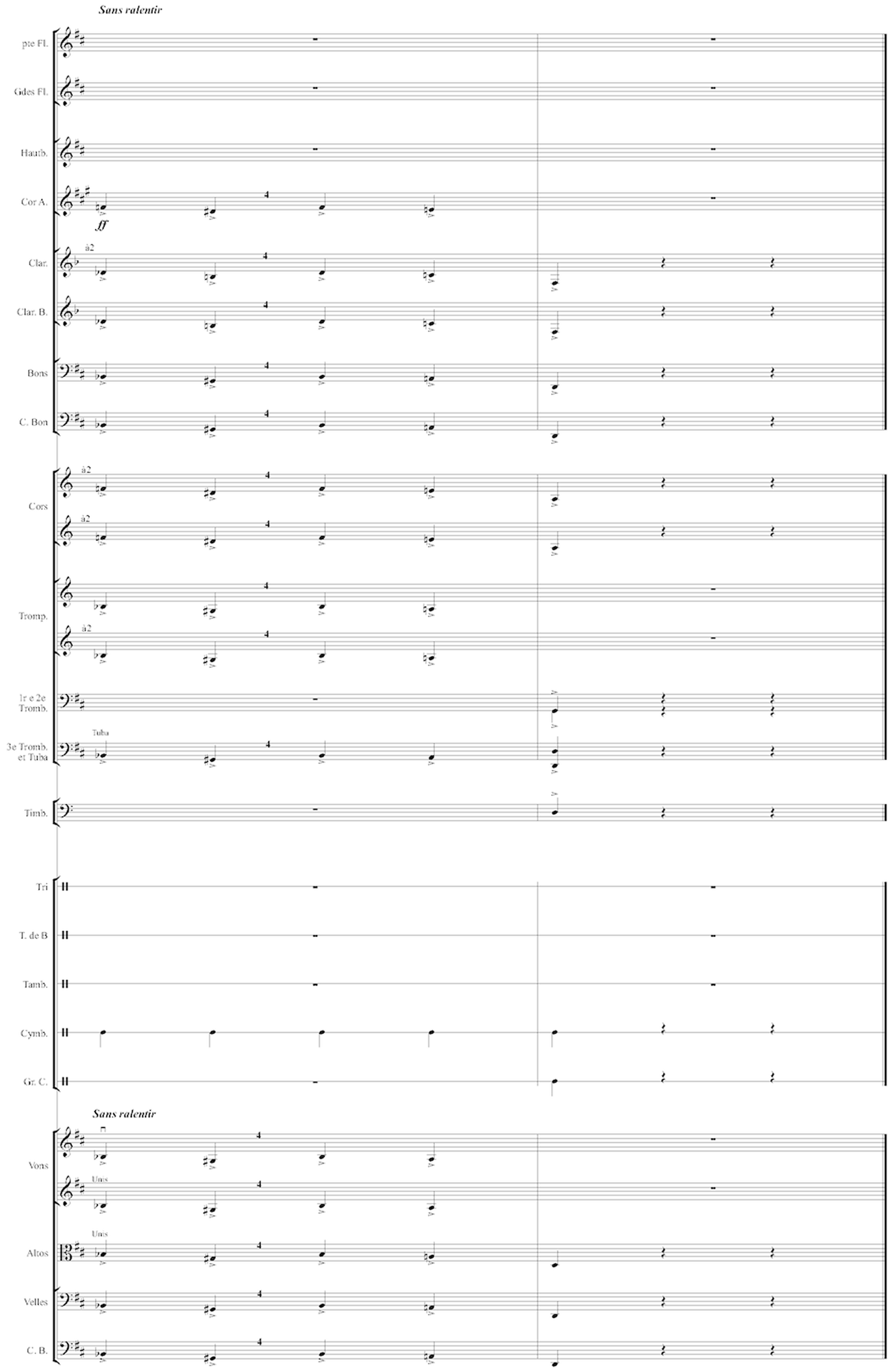

Ravel, too, addressed wartime mourning in many of his compositions, although his compositional tendencies differed substantially from those of his peers. Just as Morgan speaks in this issue of a counternarrative offered through paying attention to the embodied aspects of musical performance in her discussion of sheet music about the Mexican–American War, I argue that Ravel's compositions presented a counternarrative to the dominant narratives of mourning and trauma in the musical media of his time. Before composing Le Tombeau, Frontispice and La Valse, Ravel wrote Trois chansons pour choeur mixte sans accompagnement in 1914 and 1915. He poured himself into this piece while anxiously awaiting the results of his application for the French military. In one of these Trois chansons – the second movement, ‘Trois beaux oiseaux du paradis’ – Ravel makes direct reference to the war through red, white and blue imagery and the refrain, ‘Mon ami z-il est à la guerre’. In line with contemporary conventions for wartime music, Ravel sets his text for unaccompanied choir.Footnote 61 However, unlike many composers of wartime patriotic compositions about mourning, Ravel closes this song on a sombre note: he underlines the final iteration of ‘ton ami z-il est à la guerre’ with a lamenting, chromatically descending tenor line, after which we hear the final line of the song: ‘Ah! Je sens mon Coeur qui froidit … Emportez le aussi’ (Ah! I feel my heart growing cold … Take it with you also). This line fades out quickly and quietly with the help of the choir, the lower two voices of which remain silent, while the upper two sing bouche fermée (see Ex. 2). This song's lack of specific patriotic musical references, the ambivalence of its text and its subdued conclusion – lacking the bombastic, victorious or redemptive qualities of the wartime music of his contemporaries – render Ravel's song an outlier.Footnote 62

Ex. 2 Maurice Ravel, Trois chansons pour choeur mixte (Paris: Durand & Cie, 1916), ‘Trois beaux oiseaux du Paradis’, bars 41–48

After the Trois chansons, however, as Ravel's critics would say, things only became ‘stranger’. In the remainder of this article, I focus on moments of violence and rupture in Le Tombeau, Frontispice and La Valse – moments I theorize are ‘magic words’ that reveal Ravel's grief and trauma. I will address these pieces in chronological order of completion, and so we begin with Le Tombeau de Couperin.

Le Tombeau de Couperin: From Affective Dissonance to Compositional Cryptonymies

Well before the pianist plays the first delicately twinkling notes of the piece's Prélude, Ravel's title for Le Tombeau de Couperin acts as a kind of ‘magic word’ that prompts us to consider a psychic crypt. In his forward for Abraham and Torok's Wolf-Man text, Derrida tells us that the crypt is ‘not a natural place but the striking history of an artifice, an architecture’ that ‘commemorates, as the incorporated object's “monument’ or ‘tomb” … the exclusion of a specific desire from the introjection process’.Footnote 63 In his article on ‘Tombeau’ in the Dictionnaire de la Mort, Marc Villemain makes a distinction between tombe and tombeau that strongly resonates with Derrida's interpretation of Abraham and Torok's psychic crypt:

In the West, no distinction was really made between a tombe and a tombeau until the eighteenth century, even if tombe tended somewhat to designate a grave, with tombeau acting more as a synonym of mausoleum. In the contemporary French language, the distinction is clearer: tombe is the place where the body has been buried, the grave where it has been placed, while tombeau denotes the architectural ornamentation that signals the presence of the tombe and invites contemplation.Footnote 64

On the one hand, Ravel's assignment of different dedications to each of the individual movements of the suite allows his Tombeau to act, in alignment with the pre-eighteenth-century definition of tombeau, like a mausoleum. On the other hand, especially given the funerary urn that Ravel drew for the piano score's title page, Ravel's title more generally can be understood as the ornamented monument that gives the lie to the tomb, that points to the existence of secrets, bodies, memories and affects buried beneath it.Footnote 65

Ravel enhanced the polysemousness of Le Tombeau de Couperin's title through various paratextual signifiers that especially contribute to understanding the piece as an analogue to one of the Wolf-Man's magic words. As Abraham, Torok and Derrida point out, the linguistic signals of mourning are polyvalent encodings of the trauma that led to the crypt's very creation and thus betray its existence. First, there are Ravel's indications that his audience understand the composition as a memorial: the drawing of the funerary urn on the title page, Ravel's dedications to fallen soldiers and his naming the composition a tombeau (see Fig. 1). Ravel, however, rendered each of these signifiers of mourning open and inconclusive, preventing them from operating or being understood straightforwardly. In what Nichols has called an attempt to ‘downplay the memorial elements of the suite’, Ravel claimed that he never intended to have the drawing published.Footnote 66 Rather, he ‘amused [him]self in drawing these arabesques on the first page of [his] manuscript, without ulterior motive’, and his publisher subsequently ‘amused himself by reproducing this fine drawing’. Ravel added that, ‘the engraver added to it skilful alterations which give it an awkward and pretentious allure that I was far from intending’.Footnote 67 Regardless of what Ravel may have initially intended with his drawing, he nevertheless allowed it to appear on the title page of the published score of the work, making it the first thing that anyone sitting down to play the suite would notice. All of these signifiers suggest grief but also its denial, thus rendering the piece suspect and mysterious, and compelling us to read further into these strangely significant ‘magic words’.

Fig. 1 Maurice Ravel, Le Tombeau de Couperin (Paris: Durand & Cie, 1918, repr. 1957), title page

It is in the music, however, that Ravel presented some of the clearest invitations to read more deeply into Le Tombeau de Couperin, and to consider it intertwined with his post-war trauma. As I have discussed elsewhere, the first and last movements of Le Tombeau feature incredibly difficult, highly virtuosic and repetitive, moto perpetuo music that suggests that this piece may have functioned as a means for performers like Marguerite Long – one of Ravel's closest friends after the war, who had also experienced loss and trauma between 1914 and 1918 – to perform, work through and console themselves during trauma.Footnote 68 In addition, although Ravel's focus in Le Tombeau on France's pre-nineteenth-century musical past – evident in the piece's dance suite structure and the neoclassical musical gestures and style – can be read as a nationalistic nod to French history that was popular during and after the war, this emphasis also permits Ravel opportunities to highlight moments of ‘strangeness’ in the distance he articulates between past musical styles and borrowings, and their manifestations in his modernist musical rhetoric.Footnote 69 For example, the suite's Forlane offers what might be considered a ghostly or spectral rendition of François Couperin's Forlane in his 1722 Quatrième concert royaux. In this movement, Ravel ‘buries’ Couperin's original within his own, leading Abbate to posit that here there is ‘a more nebulous object … heard through the walls of the tomb’. For Abbate, recent mechanistic musical inventions – which she asserts symbolized the recent devaluation of live performers – are the source materials that animate and haunt Ravel's cryptic Forlane.Footnote 70 In my reading, however, Ravel's angular and dissonant, yet still elegant, version of Couperin's Forlane functions as a sonic representation of the ‘strangeness’ of cryptonymy, particularly evoking Derrida's description of the psychic crypt in which the lost loved one remains entombed as fractured and splintered – the result of the psyche's futile attempts to keep a love object secreted away.Footnote 71

The piano suite's fourth movement – the Rigaudon – offers one of the clearest examples of Ravel's musical cryptonymy within Le Tombeau de Couperin. Ravel dedicated the Rigaudon to two brothers – Pierre and Pascal Gaudin – who were childhood friends killed in combat in late 1914. Like the other movements in the piano suite, the Rigaudon presents listeners with a relatively jovial and seemingly carefree piece of music. However, I read this movement as a performance of the pain, violence and trauma of the emotional work that goes into keeping one's grief contained and imperceptible. This movement exhibits an ABA structure with jaunty and cheerful A sections that contrast with a sombre and melancholy B section. Ravel's Rigaudon appears as a testimony of the psychic trauma of emotional masking in large part because of the persistent reappearance of a brusque, violent and dissimulating gesture that I term ‘the grotesque grin’, perhaps a reference to Ravel's own experience of being forced to ‘grin and bear’ his grief over his mother's death while still in the military. This gesture appears first at the opening of the movement, providing an emphatic and attention-grabbing introduction with what sounds like a traditional tonal cadence moving from IV through ii and V to land on a C-major root position chord, even though it is piled with sevenths, ninths and elevenths (see Ex. 3). However, the cadential nature of the figure stands out due to the quick, accented and fortissimo performance of the gesture Ravel requires of the performer. In my reading, this figure shouts its false contentedness through gritted teeth and a forced smile, functioning as a mask that is a performed index of the effort expended in conforming with conventions of mourning privileged in interwar France. The phenomenological experience of performing the grin gesture – at least in the keyboard version of the piece – bolsters an understanding of this gesture's Janus-faced nature: the pianist begins the gesture with their hands close to their body and the centre of the keyboard, but in the course of playing the figure, ends up with hands away from the body, on opposite sides of the keyboard. In other words, the pianist is forced through musical performance to perform body language that indicates disgust – the physical pushing away of something.Footnote 72 For these reasons, the grotesque grin gesture functions like a ‘magic word’ that attempts to conceal but ends up revealing – through the page and its bodily performance – the wound of psychic trauma.

Ex. 3 The ‘Grotesque Grin’ in Maurice Ravel, Le Tombeau de Couperin (Paris: Durand, 1918), ‘Rigaudon’, bars 1–2

Further supporting my reading of the grin gesture as an emotional mask is the fact that much of the motivic material in the A sections seems aimed at retroactively normalizing revealing utterances in a kind of emotional denial characteristic of the speech and actions of people who have experienced psychic trauma. Herman, Abraham and Torok have pointed out the ways in which people who have been held captive, experienced long-term abuse, or lived through traumatic grief are often forced to suppress or deny the traumatic nature of these situations in order to live through them. While for Abraham and Torok this kind of denial often led to ‘magic words’, Herman describes the tendency for abused children or people who have lived in captivity to deny their experiences as a kind of Orwellian doublethink: a ‘psychological adaptation’, which might involve ‘frank denial, voluntary suppression of thoughts, and a legion of dissociative reactions’, that people undertake when forced to endure an ‘unbearable reality’.Footnote 73 She asserts, in fact, that,

the conflict between the will to deny horrible events and the will to proclaim them aloud is the central dialectic of psychological trauma. People who have survived atrocities often tell their stories in a highly emotional, contradictory, and fragmented manner which undermines their credibility and thereby serves the twin imperatives of truth-telling and secrecy.Footnote 74

Musically, we see this impulse towards denial and suppression in the narrativization of trauma in Ravel's Rigaudon just after the first appearance of the grin gesture in the movement's first bars. Here Ravel composes an exceedingly quick transition to a mezzo-piano, unaccented and captivatingly dancing passage that in its gestural, harmonic and rhythmic resonances with the opening gesture, seems to attempt to save face: to distract from the initial offending gesture while also suggesting that there was nothing to conceal in the first place (see Ex. 4a). To further draw attention away from the dissimulation of the gesture, Ravel uses a repeat sign in bar 8, thus reframing the grotesque grin of the opening as not so much an ill-conceived attempt to conceal, as the logical outcome of the straightforward harmonic and melodic progression accompanied (as convention would have it) by a crescendo.

Ex. 4a Maurice Ravel, Le Tombeau de Couperin (Paris: Durand & Cie, 1918), ‘Rigaudon’, bars 1–8

Another example of Ravel's attempts at emotional masking through recontextualization and misdirection appears at bars 23–24. Here Ravel composes a reiteration of the opening grin gesture in F-sharp – a tri-tone away from the C major of the gesture in its first appearance. As in the case of the opening figure, Ravel asks the performer to accent it and play it fortissimo. Like in the earlier instance of recontextualization, Ravel figurally, dynamically and harmonically prepares the listener for the gesture. But he also marks the ‘grotesque grin’ as inappropriate and requiring retroactive concealment: immediately after the F-sharp major chord in bar 25, Ravel asks the pianist to drop down to pianissimo – the softest dynamic of the A section so far – for a passage that is one of the most charming of the entire movement (see Ex. 4b). In bars 25–32 Ravel presents listeners with sparkling staccato passagework, reaching into the piano's high register to create the dancing brilliance of a charming music box. Ravel seems here to guide the listener's attention elsewhere in the skilful misdirection often required in concealing what might be considered indiscreet emotional performances. Ravel's secret keeping here thus resembles cryptonymic repression, especially in this process's requirement that trauma be kept hidden from the ego that contains it.

Ex. 4b Maurice Ravel, Le Tombeau de Couperin (Paris: Durand & Cie, 1918), ‘Rigaudon’, bars 23–32

The grotesque grin gesture's obsessive masking function comes especially to the fore in the B section of the Rigaudon, where it acts as a moderator that keeps undesirable emotional expression at bay. Michael Beckerman, and later Jessica Schwartz, have pointed out that middle sections – such as the B section in an ABA form – often contain secrets. Beckerman writes:

It is in my experience that middles often represent composers at their most unguarded and honest, their most creative, and quite often their most expressive. Middles are a land of dreams, a place where structure may be forgotten, at least for a while; containing everything from death (funeral marches) to amorous secrets. The middle (whether of a phrase, a movement, or an entire work) may be understood as something like the sonic subconscious.Footnote 75

Ravel's Rigaudon seems to align with the aesthetics Beckerman observes. In the B section Ravel achieves affective contrast through a shift to C minor, a drastically slower tempo and drawn-out melodic material performed over an undulating quaver accompaniment (see Ex. 5). In addition, the B section features four attempts at mournful expression that might be understood as reflecting Ravel's struggle to find the proper words or forum for expressing his grief. The first three attempts – at bars 37, 53 and 69 – begin with a despondent drone followed by a melancholy melody that avoids articulating sorrow too strongly by falling back on jaunty melodic fragments from the A section's motivic material. But the grin motive's function as a signal of repressed emotion is particularly evident in its aggressive reappearance in the B section's fourth attempt at mournful expression. Unlike Ravel's previous efforts at emotional performance, the fourth attempt, beginning at bar 85, does not begin with a drone, but rather with a new affective trajectory marked by a tuneful melody played in octaves, although still over the same undulating accompaniment that marked the previous attempts. It is at this precise moment – when the realization of an alternate expressive mechanism has only barely begun – that the grotesque grin gesture comes suddenly and violently crashing in at bar 93, signalling both the return of the A section, but also, and more importantly, the evasion of an affective crisis. Paradoxically, however, this attempted evasion does not avoid, but rather draws attention to the existence of the crisis it attempts to conceal, just as the ‘magic words’ of the traumatized mourner betray the existence of the crypt buried within the mourner's ego.

Ex. 5 Ravel, Le Tombeau de Couperin (Paris: Durand & Cie, 1918), ‘Rigaudon’, bars 37–98

Musicalized Traumatic Memory in Frontispice

Like Le Tombeau de Couperin, Ravel's Frontispice can be read as commentary on the repression that was part and parcel of trauma in interwar France. In Frontispice, a short piece (generally performed in under two minutes) that Ravel wrote as a musical preface for his friend Ricciotto Canudo's war poem, SP 503, Poème du Vardar, listeners hear some of the most dissonant music in his compositional output. It is worth mentioning as well that, in parallel to his references to death, grief and remembrance in Le Tombeau, Ravel refers to the war through various paratextual elements of Frontispice, the most obvious of which are its inclusion alongside Canudo's war poem and the piece's title. Frontispice usually indicates an illustration that appears at the opening of a particular text or composition, and indeed, Ravel's composition functions in this way for Canudo's poem. However, frontispice might also be understood as referring to a piece concerning (about and/or composed at) le front – the common language for the French front lines during World War I. Moreover, Ravel's decision to set this piece for piano five hands (an extremely rare choice) results in a composition ostensibly requiring two two-handed performers and one one-handed performer. In this way, Ravel embeds one-armedness – a condition experienced by many soldiers and civilians wounded during World War I to which many French men and women bore witness in the years during and after the war – into his composition.Footnote 76

Again, however, it is Frontispice's music that provides listeners with the clearest indications of this piece's connection to wartime trauma. The first ten bars of Frontispice convey the psychological confusion characteristic of traumatic disorders common in World War I through extreme metric, melodic, harmonic and motivic dissonance (see Ex. 6). Ravel juxtaposes different musical ideas in order to increase melodic and harmonic dissonance: the first performer who enters plays a chromatic melody beginning on D# with their right hand while playing a triplet chromatic ostinato figure with their left hand. The second performer plays a mostly diatonic folk-like melody in quavers and semiquavers, accompanied by C major and G dominant seventh chords.Footnote 77 If we understand this piece as a sonic analogue to remembered time on France's front lines, this snippet of folksong resonates with the musician-soldier Georges Grisez's story of hearing a ‘horribly sad voice’ singing a minor-key folksong while serving for the Armée d'Orient in Macedonia – the same country where Canudo had not only served in the military, but also set ‘Sonate pour un jet d'eau’, the poem from SP 503 Poème du Vardar that had first appeared alongside Ravel's Frontispice in a 1919 issue of the artistic journal Feuillets d'art.Footnote 78 Ravel may have read Grisez's account since it was published in 1917 in the Gazette des classes du Conservatoire, which occasionally printed news about Ravel, and which Ravel likely received since Nadia and Lili Boulanger – the Gazette's editors – were not only friends with Ravel, but also aimed to have the journal reach as many French musician-soldiers as possible. Furthermore, in Frontispice's sixth bar the third pianist enters with pianissimo, ornamented, offbeat semiquaver figures that sound like twittering birds.

Ex. 6: Maurice Ravel, Frontispice (Paris: Salabert, 1975), bars 1–6

Significantly, Ravel increases dissonance progressively throughout the piece, adding new ideas one by one until six distinct musical ideas are being performed simultaneously by the composition's halfway point. Throughout Frontispice each of these musical ideas maintains its profile as Ravel layers them one on top of another, creating an overpowering and inescapable sound-world suggestive of an unstoppable influx of sonic memories. This layering of voices, along with an increasing diminution of note values throughout the piece, creates a steady crescendo, which becomes particularly overwhelming in Frontispice's tenth bar. Here Ravel asks all three pianists to perform an additional crescendo that instils this already harsh and grating sonic conglomeration with even more urgency, making the listener wonder how much more physical discomfort from dissonance Ravel will force them to withstand. These distinct, overlapping musical ideas in Frontispice therefore function as musical analogues to the flashbacks and auditory hallucinations frequently experienced by traumatized soldiers.

At the end of Frontispice Ravel introduces a new idea – yet another a ‘magic word’ – that signals a musical repression of the trauma conveyed in the previous bars. Ravel frames bars 11–14 as a re-composition of the piece's first ten bars by beginning piano, gradually crescendoing and steadily adding voices (see Ex. 7). But this re-composition includes only one musical idea: a series of five stoic chords repeated four times. Ravel marks these legato, and only changes them in each repetition by adding additional voices that expand their tessitura and volume. When compared with what appears in the composition's first ten bars, these stoic chords appear like a sonic mask that attempts – adamantly and increasingly forcefully, much like the grotesque grin – to place a brave, polished and ultimately heroic face on the psychological pain and overwhelm of the previous bars. Frontispice's final gesture, consisting of a mysterious and playful ornamented semiquaver-dotted-quaver figure played pianissimo, somewhat undermines this final section's stoicism, highlighting that this brave face, like so many emotional masks, is only a temporary performance. Moreover, the piece concludes without anything resembling a conclusive resolution of the dissonance that has come before; as a newcomer to this composition pointed out, if you do not have the score in front of you, you might not even realize that the piece has ended. Here again Ravel gives us musical ‘magic words’ that underline the effort expended in donning an emotional mask, even while one's grief or trauma continues, unresolved, for the foreseeable future. In this light, Frontispice becomes a sonic representation of the repression of affects that haunt the soldier's psyche, despite his efforts to ‘snap out of it’ as his captain commands.

Ex. 7 Maurice Ravel, Frontispice (Paris: Salabert, 1975), bars 9–15

That Frontispice may have been written for the pianola only furthers my argument that this composition may have been about the difficulties of emotional expression. Although Ravel did not expressly indicate that he wrote this piece for pianola, the pianolist expert Rex Lawson has suggested that Ravel composed Frontispice to be performed on the pianola – a player piano for which Aeolian was soliciting compositions from modernist composers in the 1910s and 1920s.Footnote 79 Indeed, as Edwin Evans – who Ravel knew personally – wrote of the pianola in 1921, the instrument enabled ‘arabesques at any speed, regardless of the number of notes employed, and, what is more important, of their relative position – factors hitherto governed by the possible extension of the hand. It can also give us a profusion of rhythmic patterns, and especially of combined rhythms, such as no pianist could execute’.Footnote 80 Given the profusion of clashing rhythms and quick, ornamental figures in Frontispice, it seems likely that Lawson is correct in his assertion that Ravel wrote Frontispice to be played – at least some of the time – on the pianola.

Frontispice, if written for the pianola, may have also provided additional challenges and benefits to the pianola player in terms of expressivity. Edwins wrote that the pianola

is a piece of mechanism interpolated between the performer and his medium. Like all other mechanisms, its primary purpose is to lighten the mechanical side of human labour, the ultimate prospect being that the performer, relieved of the purely digital part of his labour, should be better able to concentrate upon the mental.Footnote 81

He adds that, ‘perhaps it demands even greater skill than playing the pianoforte’.Footnote 82 Coburn concurred, defending the instrument from critics who likened it to the gramophone by focusing on the instrument's difficulties for the performer, as well as its value as a ‘means of personal expression’.Footnote 83 Virginia Woolf even described the pianola as ‘a wonderful machine – beyond a machine in that it lets your own soul flow thro’.Footnote 84 The author of the 1907 how-to guide to pianola playing, Gustav Kobbé, notes in the first chapters of this guide that the pianola was an instrument specifically focused on expression, since the technical skill of being able to play notes in the correct order and rhythm was no longer an issue for the pianolist; rather, the pianolist's task was to play with the timing, dynamics, and other expressive dimensions of musical performance.Footnote 85 There may have therefore been something especially appealing to Ravel about writing a composition about wartime trauma for a machine that, while considered by the general public as lacking expression, in fact offered incredible and often misunderstood opportunities for self-expression: in so doing he may have offered a musical metaphor that speaks to the complicated relationship between feelings and their public expression and perception.

Moreover, if Ravel composed Frontispice for the pianola, he may have done so specifically as a nod to soldiers’ wartime experiences, and to make the piece more accessible for soldiers who may not have had a high level of musical proficiency. As Coburn pointed out in his defence of the instrument, the pianola made music-making more accessible to a wider swath of the population, offering amateur musicians ‘pure musical enjoyment’ of difficult repertoire.Footnote 86 In addition, numerous wartime military hospitals had pianolas for soldiers to play, as the Scottish doctor Agnes Savill describes when discussing her tenure in the French hospital at Royamount Abbey: ‘In these early days of 1915 the pianola was placed at the end of the huge refectory. … A number of the staff and many of the convalescents played the instrument, and many and varied therefore were the renderings one heard of the same music.’Footnote 87 It is possible, then, that Ravel had wanted to allow soldiers who would have otherwise been unable to play the piece – especially if they had only mediocre piano skills or could not find two other performers to join them – to perform a musicalized version of their traumatic experiences or symptoms that not only acknowledged their situations, but also was perhaps just removed enough from the reality of traumatic experience to help them process their trauma.Footnote 88

Memory and the Cryptonymy of Irreversible Loss in La Valse

Although Ravel's ballet La Valse is entirely different in form from Frontispice and Le Tombeau, it nevertheless similarly demonstrates Ravel's ‘compulsion to repeat’ cryptonymic expressions of traumatic grief within his immediately post-war compositions. In his 1920 ballet, Ravel provides the listener with a series of waltz motifs. As Puri and Jann Pasler have noted, these motifs operate somewhat like memories: not only are they hazy and fragmented, but they fade into and out of one another often in a non-linear fashion, and frequently in an order that does not appear immediately logical.Footnote 89 There is also a more literal connection between memory and the waltz fragments Ravel composed since, as I noted earlier, working on this piece reminded him very much of time spent with his mother in 1906 – when he began working on the piece – and in 1914, when he continued working on the composition before enlisting in the French army.Footnote 90

The waltzes that Ravel included in La Valse are fractured and fragmentary, like the ghostly memories that return to haunt the mourner described by Abraham, Torok and Derrida. From its inception the piece has been bound up with death and memory. The waltz, as a distinctly nineteenth-century dance, was already imbued with memory for many of the composition's first listeners, especially given the popularity and thus recognizability of the genre. In addition, the piece's initial title when Ravel began the composition in 1906, Wien!, as well as Ravel's stage directions for the ballet, demonstrate that Ravel wanted his waltzes to strongly evoke nineteenth-century Vienna – a city in a time period that, by the end of the war, was considered by many to be irrevocably changed from its nineteenth-century manifestation.Footnote 91 And then there is La Valse's origin story, as asserted by Nichols, that Ravel received the idea for the piece from his good friend Ricardo Viñes, who wrote in his diary about having been to the 1905 Opéra Ball with Ravel and several of their friends:

It was the first time I had been to the Opéra ball, and as always when I see young, beautiful women, lights, music and all this activity, I thought of death, of the ephemeral nature of everything, I imagined balls from past generations who are now nothing but dust, as will be all the masks I saw, and in a short while! What horror, oblivion!Footnote 92

Ravel's doodles on the manuscript score for his piano arrangement of La Valse suggest that the composer associated the piece with danger, if not death. At the very bottom of his score, Ravel drew whirling dancers who spin out of control, landing upside down and flat on the ground (see Fig. 2). Ravel's choice to treat the dangerousness of the waltz in this humorous and playful way was not unusual: as many of Ravel's contemporaries and subsequent music historians have acknowledged, humour, irony, and sarcasm were some of Ravel's favourite means of masking his emotions.Footnote 93 Thus we might understand Ravel's choice to focus on waltzes as one intimately bound up with the dance's associations with danger, death, memory, and the irretrievability of the past.

Fig. 2 Maurice Ravel, La Valse, arr. piano (two hands), autograph manuscript (1920), Pierpont Morgan Museum and Library, Cary 512

The ghostliness of Ravel's waltzes is especially evident in the opening and closing sections of La Valse, both of which are characterized by only bits and pieces of waltzes. At the opening of the piece, for instance, the bassoons emerge out of a nebulous, minor key cloud of sound with a limping waltz fragment at bars 12–13, which is followed by new waltz fragments appearing every three to six bars. Other instruments gradually and somewhat intermittently enter with waltz fragments as well until rehearsal A, where the bassoons and violas appear with the first lengthier, seemingly intact waltz melody – an elongated version of the waltz fragments performed at the ballet's opening. Whereas Puri understands this gradual progression as a staging of the ‘arduousness of memory work’, I would argue that the somewhat ominous and often grotesque framing of these waltz fragments articulates a resistance to or ambivalence within this act of remembering.Footnote 94 This reading resonates with Ravel's statements to friends while completing La Valse that remembering his mother's presence was both pleasurable and painful.Footnote 95 Ravel conveys this ambivalence not only by beginning the piece in a minor key, but also by utilizing dissonant minor and major seconds in the first of his waltz fragments, and by scoring these initial fragments for bassoon, which had developed associations with the magical, supernatural and grotesque through its appearances in the ‘Songe d'un nuit de Sabbath’ movement of Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique, and in Paul Dukas's L'Apprenti sorcier, amongst other pieces.Footnote 96 Furthermore, Ravel has the orchestra react defensively to each of the bassoons’ waltz fragments through accented chords in the muted horns and strings. By progressing from these minor-key, ominous fragments to a full-fledged major-key waltz played by the entire orchestra, Ravel seems to suggest that memories of dead loved ones can sometimes become more pleasant as one comes to accept their presence.

If the first section of La Valse suggests ambivalence about remembering, the second section of the ballet (R. 18 to R. 54) conveys the paradoxical pleasure of luxuriating in memories of pleasurable moments once spent in the presence of now-dead loved ones. Ravel takes the listener through a series of waltzes, giving her time to become comfortable with each one before moving on to the next. Although these waltzes appear in a variety of keys, Ravel maintains a relative sense of stability and comfort compared to the opening and closing sections of the ballet through composing these waltzes primarily in major keys, and by returning frequently to waltz melodies that become increasingly familiar through repeated hearings. Moreover, Ravel uses the full orchestra throughout most of the ballet's middle section, resulting in an immersion of sound that brings to mind Ravel's statement about feeling his mother's ‘dear sweet presence’ enveloping him as he worked on this piece.

However, the end of La Valse provides listeners yet again with what might be read as a musical representation of the closure of a psychic crypt. A sense of panic notably characterizes the final third of La Valse, in which waltz fragments spin out of control at harrying speeds, growing increasingly louder and higher in pitch. Like Puri, I read the panic and desperation of these waltzes as related to Ravel's mother's death, though I extend his argument by suggesting that these are affects, images and objects that have emerged ‘from the crypt’, an interpretation that aligns with Roland-Manuel's assertion of these waltzes as ‘phantom dancers’. The cryptonymic logic of La Valse becomes even clearer when Ravel closes the piece with a forceful gesture that puts an end to these swirling memories: an accented crotchet quadruplet followed by an accented crotchet. The gesture subdivides the penultimate bar of the piece into four beats, thus seeming to foreclose on the possibility of returning to the triple meter of the waltz (see Ex. 8c). Notably, this closing figure closely resembles the musical figure that closes Le Tombeau's Toccata (and thus the suite) (see Ex. 8b), and the grotesque grin gesture that concluded the Rigaudon of Le Tombeau de Couperin (see Ex. 8a). The consistent reappearance of this figure, which is almost entirely absent from Ravel's pre-war compositions, suggests that Ravel understood this particular musical gesture as an expression of emotional repression.

Ex. 8a Ravel, Le Tombeau de Couperin (Paris: Durand & Cie, 1918), ‘Rigaudon’, bar 128

Ex. 8b Ravel, Le Tombeau de Couperin (Paris: Durand & Cie, 1918), ‘Toccata’, bars 250–251

Ex. 8c Ravel, La Valse, orchestral score (Paris: Durand & Cie, 1921), bars 754–755

Conclusion: Ravel's Politics of Mourning – Melancholia as Resistance

What should we make of the apparent ‘strangeness’ of Ravel's post-war compositions? What meaning might we take from Ravel's tendency to employ cryptonymic logic? In my reading, the persistent appearance of haunting, incongruous and violent moments in these three pieces suggests that Ravel compulsively – whether consciously or not – continued to perform the trauma he experienced after 1914. His choice to do so is not unique within the twentieth century. Numerous late-twentieth- and twenty-first-century psychologists such as David Aberbach and Christopher Bollas have observed that many people who survive traumatic experiences either consciously or unconsciously repeat and work through their trauma in creative works.Footnote 97 But performing a politically adamant resistance to conventions of so-called ‘normal’ mourning in one's socio-cultural context has also been an important conscious choice in a number of political movements. For instance, scholars such as Sara Ahmed, Douglas Crimp, Ann Cvetkovich, David Eng and David Kazanjian have written about the social and political importance within AIDS and LGBTQIA+ activism of continuing to perform grief and trauma publicly in order to effect change.Footnote 98 And Rebecca A. Pope and Susan J. Leonardi have extended Crimp's emphasis on mournful militancy within AIDS activism to Diamada Galas's 1990 Plague Mass, which Galas wrote and performed as an emotional and politically motivated response to her brother's death from AIDS.Footnote 99 More broadly, philosophers, literary critics and historians such as Jacques Derrida and Jonathan Flatley have argued for melancholia as a forceful expression that shapes our relationships to language, as well as to unjust social and political situations.Footnote 100 Regardless of whether continued, non-normative mourning is consciously performed or not, performances of mourning have often been understood in political terms.

The ‘strangeness’ that critics heard in Ravel's post-war compositions can be understood as offering a significant counternarrative to normative modernist musical mourning traditions in World War I-era France through expressions of resistance to nationalistic norms requiring the suppression of trauma for the war effort. As numerous scholars of early twentieth-century musical cultures have pointed out, Ravel was proud of his French heritage while simultaneously wary of French nationalism. His resistance to French nationalism became especially evident during the war when – to take just one example – he refused to sign the mandate boycotting the performance in France of all works by contemporary Austro-German composers created by the Ligue nationale pour la defense de la musique – an organization that had been founded in March 1916 by French nationalist musicians Saint-Saëns, Théodore Dubois, Gustave Charpentier and Vincent d'Indy, amongst others. Even though failing to sign the petition meant having his compositions blacklisted from concerts the Ligue oversaw, Ravel nevertheless indicated his refusal to the members of the comité d'honneur of the Ligue from his military post, and confessed to Marnold his feelings that, ‘seriously, this “patriotic” act [of the Ligue's petition] presents a danger’.Footnote 101 However, going beyond the discussions of Ravel's leftist political leanings and his complex relationship to French nationalism – which included not only his emotional relationship to politics, but also his relationship to French nationalist politics of emotion – tells us a different story about Ravel and his politics of mourning.

Derrida's politics of mourning in his time are instructive here. In his essay in response to his friend Roland Barthes's death, Derrida finds fault with the ‘typical solutions’ societies and individuals provide when someone dies.Footnote 102 In Pascale-Anne Brault and Michael Naas's introduction to their collection of Derrida's commemorative writings, entitled The Work of Mourning, they underline that,

Derrida reflects in these essays on the very genre of the eulogy or funeral oration, all the while himself giving orations and eulogies, pronouncing them, working within the codes and tropes of such speech acts and yet referring throughout to what exceeds them … Eulogizing the singularity of the friend, he has tried to inhabit and inflect both the concept and the genre of mourning differently. He has tried to reinvent, always in public and always in context, that is, always from within, a better politics of mourning.Footnote 103

Ravel's turn during the war years to more intimate, personal and psychological portraits of grief and trauma suggests that one of his post-1917 desires may have been to find modes of expressing grief and trauma that differed from the nationalism-tinted musical expressions – the ‘typical solutions’ – of his peers. Ravel's cryptonymic logic, embodied in his resistance to World War I-era conventions for musical mourning, prefigures and resonates with Derrida's concerns about how to mourn adequately and ethically.

With this in mind, we might understand the ‘strange’ moments of rupture, violence and discord that appear in Le Tombeau de Couperin, Frontispice and La Valse as indications of Ravel's desire to locate a ‘better politics of mourning’. For Ravel this better politics of mourning might have entailed giving people the time and space they needed to work through trauma and loss or providing them with opportunities to express their emotions rather than remain silent for the ostensible good of the nation. Or perhaps a better politics of mourning would have involved resisting the pervasive pressure in interwar France to mourn publicly only heroic deaths that occurred in the name of the nation.Footnote 104 The cryptonymic logic of Ravel's immediately post-war compositions allowed him a means to work through his own grief and trauma in unspoken terms. But cryptonymic logic also provided him with opportunities to resist conventional genres, styles and emotional performances of his time, allowing him in turn to tell different kinds of stories about ‘acceptable’ mourning and traumatic experience – ones that acknowledged the singularity of each loss, as well as the struggle inherent in processing, expressing and coping with each unique instance of traumatic experience.